An Offer You Can’t Refuse

How US Federal Prosecutors Force Drug Defendants to Plead Guilty

Summary

Darlene Eckles let her drug-dealing brother operate from her house for six months and helped count his money. Federal prosecutors offered to let her plea to a 10-year sentence; she rejected the offer and is now serving an almost 20-year sentence.

Federal prosecutors offered to let Patricio Paladin plead in return for a 20-year sentence for cocaine distribution. He refused to plead and is now serving a sentence of life without parole.

Weldon Angelos was offered a plea of 15 years for marijuana distribution and gun possession. He refused the plea and is now serving a 55-year sentence.

Eckles, Paladin, and Angelos were convicted of federal drug and gun offenses after rejecting plea offers and opting instead to go to trial. Prosecutors sought their remarkably long sentences—at least double the time they would have served had they agreed to plead—not only for their crimes, but for refusing to plead guilty on the prosecutors’ terms.

***

The right to trial lies at the heart of America’s criminal justice system. Yet trials have become all too rare in the United States because nine out of ten federal and state criminal defendants now end their cases by pleading guilty.

There is nothing inherently wrong with resolving cases through guilty pleas—it reduces the many burdens of trial preparation and the trial itself on prosecutors, defendants, judges, and witnesses. But in the US plea bargaining system, many federal prosecutors strong-arm defendants by offering them shorter prison terms if they plead guilty, and threatening them if they go to trial with sentences that, in the words of Judge John Gleeson of the Eastern District of New York, can be “so excessively severe, they take your breath away.”[1] Such coercive plea bargaining tactics abound in state and federal criminal cases, including federal drug cases, the focus of this report.

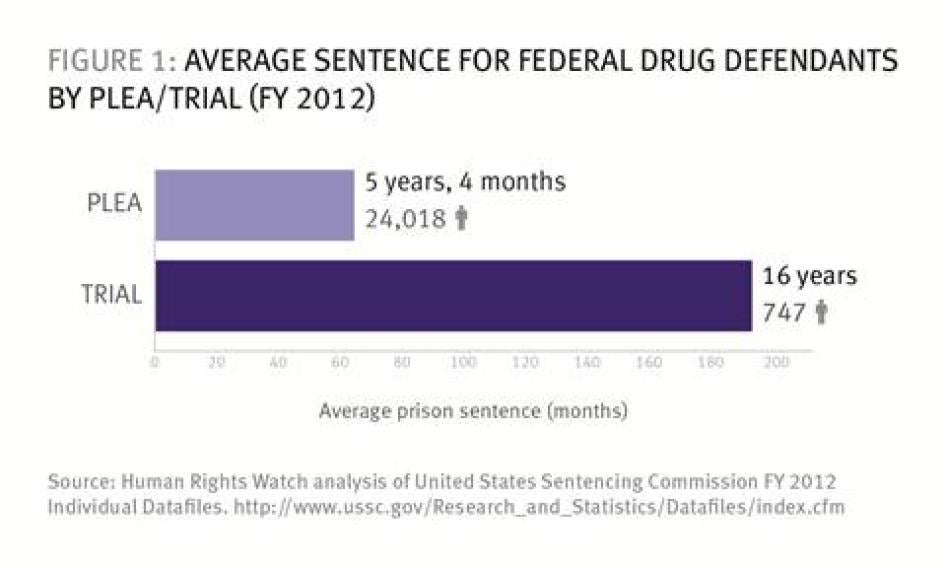

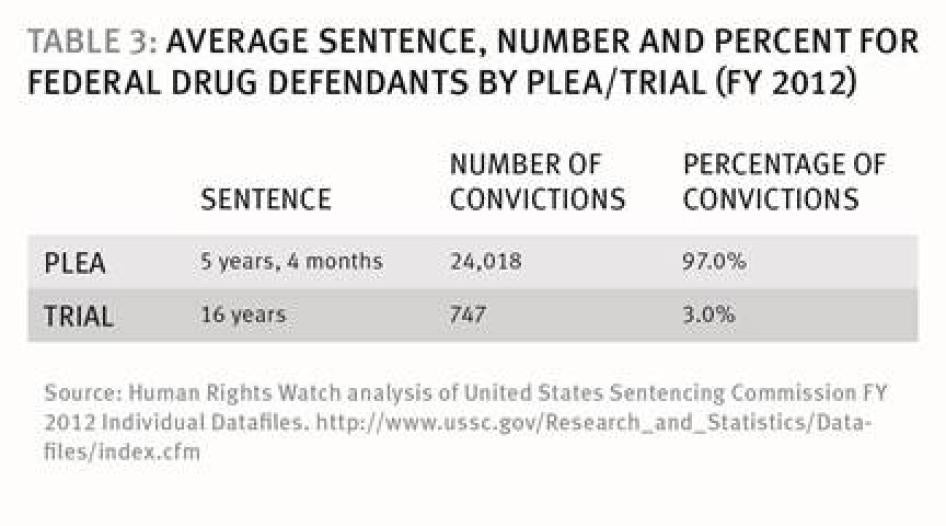

Plea bargaining means higher sentences for defendants who go to trial. In 2012, the average sentence of federal drug offenders convicted after trial was three times higher (16 years) than that received after a guilty plea (5 years and 4 months).

The threat of higher sentences puts “enormous pressure [on defendants] to plead,” Mary Pat Brown, a former federal prosecutor and senior official in the Justice Department told us.[2] So much so that plea agreements, once a choice to consider, have for all intents and purposes become an offer drug defendants cannot afford to refuse. Only three percent of federal drug defendants go to trial. Human Rights Watch believes this historically low rate of trials reflects an unbalanced and unhealthy criminal justice system.

In this report, Human Rights Watch presents cases that illustrate the unjust sentences that result from a dangerous combination of unfettered prosecutorial power and egregiously severe sentencing laws. We also present new data developed for the report that documents the extent of the “trial penalty”— the higher sentences that defendants who go to trial incur compared to what they would receive if they plead guilty. In essence, it is the price prosecutors make defendants pay for exercising their right to trial.

US constitutional jurisprudence offers scant protection from prosecutors who are willing to pressure defendants into pleading and punish those who insist on going to trial. Courts do not view defendants as unconstitutionally coerced to forego their right to a trial if they plead guilty to avoid a staggering sentence. Nor do they consider defendants to have been vindictively—that is, unconstitutionally—punished for exercising their right to trial when prosecutors make good on their threats to seek much higher mandatory penalties for them because they refused to plead. Finally, even when courts agree that prosecutors have sought egregiously long mandatory sentences for drug offenses, they will not rule the sentences so disproportionate as to be unconstitutionally cruel.

Prosecutorial Power and Mandatory Sentences

Prosecutors have discretion, largely unreviewable by judges, as to what charges to bring, what promises or threats to make in plea bargaining, and whether to carry out those threats if the defendant does not plead.

While all prosecutors are in a powerful position vis-a-vis criminal defendants, the power of federal prosecutors in drug cases is strengthened by mandatory sentencing laws that curtail the judiciary’s historic function of ensuring the punishment fits the crime. When prosecutors choose to pursue charges carrying mandatory penalties and the defendant is convicted, judges must impose the sentences. Prosecutors, in effect, sentence convicted defendants by the charges they bring.

Prosecutors typically charge drug defendants with offenses carrying mandatory minimum sentences. Mandatory minimum drug sentences are keyed to the weight of the drugs involved in the offense (and the weight of filler substances, like cornstarch, used to dilute the drug). For example, the mandatory minimum sentence for dealing 5 kilograms of cocaine is 10 years and the maximum is life, regardless of the defendant’s role or culpability. The sentence imposed upon conviction will usually be higher than the minimum, as judges—taking their cue from the federal sentencing guidelines—take into account the actual amount of drugs involved in the crime, the defendant’s criminal history, and other aggravating and mitigating factors.

In fiscal year 2012, 60 percent of convicted federal drug defendants were convicted of offenses carrying mandatory minimum sentences.[3] They often faced sentences that many observers would consider disproportionate to their crime. An addict who sells drugs to support his habit can get a 10-year sentence. Someone hired to drive a box of drugs across town looks at the same minimum sentence as a major trafficker caught with the box. A defendant involved in a multi-member drug conspiracy can face a sentence based on the amount of drugs handled by all the co-conspirators, even if the defendant had only a minor role and personally distributed only a small amount of drugs or none at all.

Drug defendants have only three ways to avoid mandatory sentences: they can go to trial and hope for an acquittal, even though nine out of ten defendants who take their chances at trial are convicted; they may (if they are a low-level, nonviolent drug offender with scant criminal history) qualify for the limited statutory safety valve that permits judges to sentence them below the applicable mandatory sentences if they are convicted—although most defendants do not qualify; and they can plead guilty.

Most prosecutors will offer drug defendants some sort of plea agreement that reduces their sentence, sometimes substantially. Indeed, they file charges carrying high sentences fully expecting defendants to plead guilty. To secure the plea, prosecutors may then offer to lessen the charges, they may offer to reduce the ones that do not carry mandatory sentences, to stipulate to sentencing factors that lower the sentencing range under the sentencing guidelines or, at the very least, to support a reduced sentence based on the defendant’s willingness to accept responsibility for the offense, i.e., to plead guilty. Prosecutors may also agree to file a motion with the court to permit the judge to sentence below the mandatory sentences when the defendant has provided substantial assistance to the government’s efforts to prosecute others.

But prosecutors also threaten to increase defendants’ sentences if they refuse to plead. Perhaps their most powerful threats are based on two statutory sentencing provisions that can dramatically increase a drug defendant’s sentence. Under 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1) prior felony drug convictions can dramatically increase a mandatory minimum drug sentence. Under 18 U.S.C. §924(c) prosecutors can file charges that dramatically increase a defendant’s sentence if a gun was involved in the drug offense. Prosecutors will threaten to pursue these additional penalties unless the defendant pleads guilty – and they make good on those threats.

Prior Convictions

Sentencing enhancements based on prior drug convictions are triggered only if prosecutors choose to file a prior felony information with the court. If a prosecutor decides to notify the court of one prior conviction, the defendant’s sentence will be doubled. If the prosecutor decides to notify the court of two prior convictions for a defendant facing a 10-year mandatory minimum sentence on the current offense, the sentence increases to life—and there is no parole in the federal system.

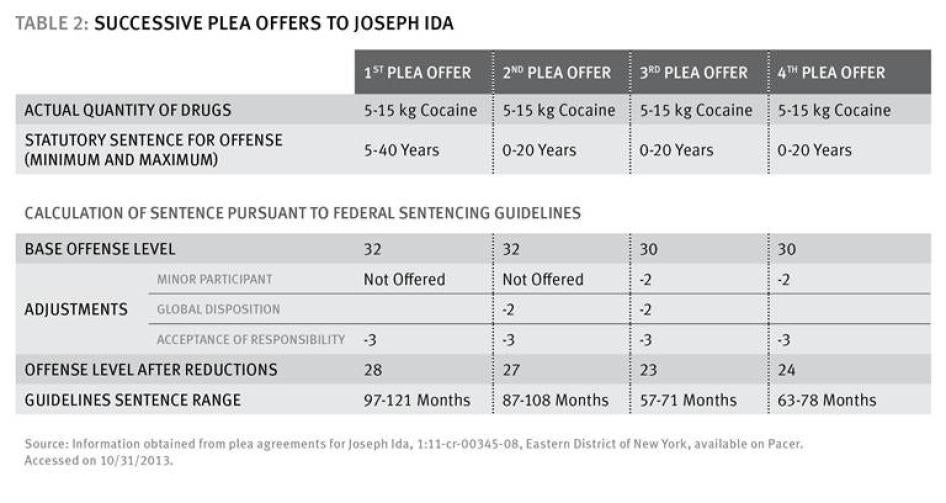

Many defendants plead when faced with the threat of such sentences. Early in 2013, for example, Lulzim Kupa refused to plead even though he was looking at a mandatory minimum of 10 years for distributing cocaine. A few weeks before the scheduled trial date, the government filed a prior felony information providing notice of two prior marijuana convictions. It then offered to withdraw the notice (as well as the original 10-year mandatory minimum) if Kupa would plead to a lower charge. He did, and avoided the prospect of life in prison—eventually receiving a sentence of 11 years.[4]

Involvement of Weapons

If a weapon was involved in a drug offense, prosecutors will press the defendant to plead by raising the specter of consecutive sentences under 18 U.S.C §924(c). The first §924(c) conviction imposes a mandatory five-year sentence consecutive to the sentence imposed for the underlying drug crime; second and subsequent convictions each carry 25-year consecutive sentences—resulting in grotesquely long sentences for drug defendants. In 2004 for example, Marnail Washington, a 22-year-old with no criminal history, was sentenced to 40 years after conviction of possession with intent to distribute crack cocaine and two §924(c) counts based on possessing, but not using, guns in connection with his drug offenses. That is, 30 years of his 40-year sentence were on gun counts.

It is entirely up to prosecutors whether to pursue these increased penalties against an eligible defendant. If they do and the defendant is convicted, the penalties are mandatory and judges must impose them. In one case in 2002, Judge Paul Cassell was so distressed at his powerlessness to avoid imposing an unduly harsh sentence on a young marijuana dealer (55 years for convictions on three §924(c) counts) that in his sentencing memorandum he called on President George W. Bush to commute the sentence. The president did not do so. And in a 2010 case, Judge Kiyo Masumoto said that she thought a 20-year sentence was “quite more than necessary” in the case of Tyquan Midyett, a low-level drug dealer who refused a 10-year plea and the prosecutors then doubled his sentence by filing a prior felony §851 information. Still, the judge said she did “not have discretion under the law to consider a lesser sentence.”[5]

Punishment to Fit the Crime?

Under well-established criminal justice principles, reflected in US and international human rights law, convicted criminal offenders should receive a punishment commensurate with their crime and culpability and no longer than necessary to serve the legitimate purposes of punishment. Those purposes include holding offenders accountable for their wrongdoing, protecting the public by keeping them in prison, deterring crime, and rehabilitating the offenders. They do not include penalizing defendants for going to trial or discouraging future defendants from doing so.

Prosecutors nonetheless believe a defendant’s insistence on going to trial is a perfectly legitimate reason to pursue an increased sentence—even one that is wholly disproportionate to the underlying offense. As a former US Attorney told us: “We weren’t trained to think about the lowest sentence that serves the goals of punishment.” [6]

Even prosecutors who try to achieve fair sentences through plea bargains acknowledge that the quest for fairness ends if the defendant refuses to plead. Prosecutors also insist they are not "punishing" defendants with higher sentences when they refuse to plead guilty, but rather “rewarding” defendants who, by pleading, spare them the expenditure of time and resources needed for a trial. From the perspective of the defendant looking at a significant trial penalty, this is no distinction.

Once they have made a threat during plea negotiations, prosecutors believe they must follow through with it if the defendant goes to trial, both because a defendant who refuses to plead deserves “no mercy,” and because they want to be sure future defendants take their threats seriously. They think they will lose credibility if they permit defendants to reap the same sentencing "concessions" after a trial as they had been offered if they pled. Asked if they thought these much higher post-trial sentences are just, prosecutors dodged the question.

In 2012, 26,560 federal drug defendants were prosecuted by 93 US Attorneys and over 5,400 assistant US attorneys in 94 federal districts.[7] Determining prosecutorial practices and policies in each district is beyond the scope of this report. Our research shows that prosecutorial charging and plea bargaining practices vary dramatically from district to district. It also shows that the trial penalty is widespread across the country.

Key Findings

Using sentencing data from individual cases collected nationwide by the United States Sentencing Commission (the Sentencing Commission), most of it from 2012, Human Rights Watch has developed statistics that shed light on the size of the trial penalty. Each case contains a unique mix of factors that results in the final sentence, but our findings nonetheless provide deeply troubling evidence of the price defendants pay if they refuse to plead.

Among our findings:

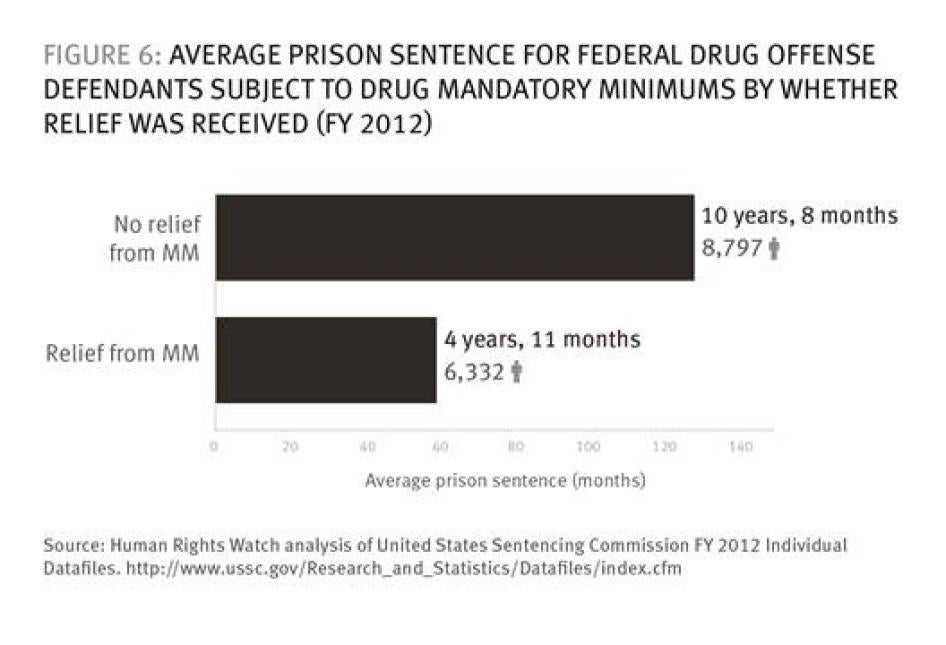

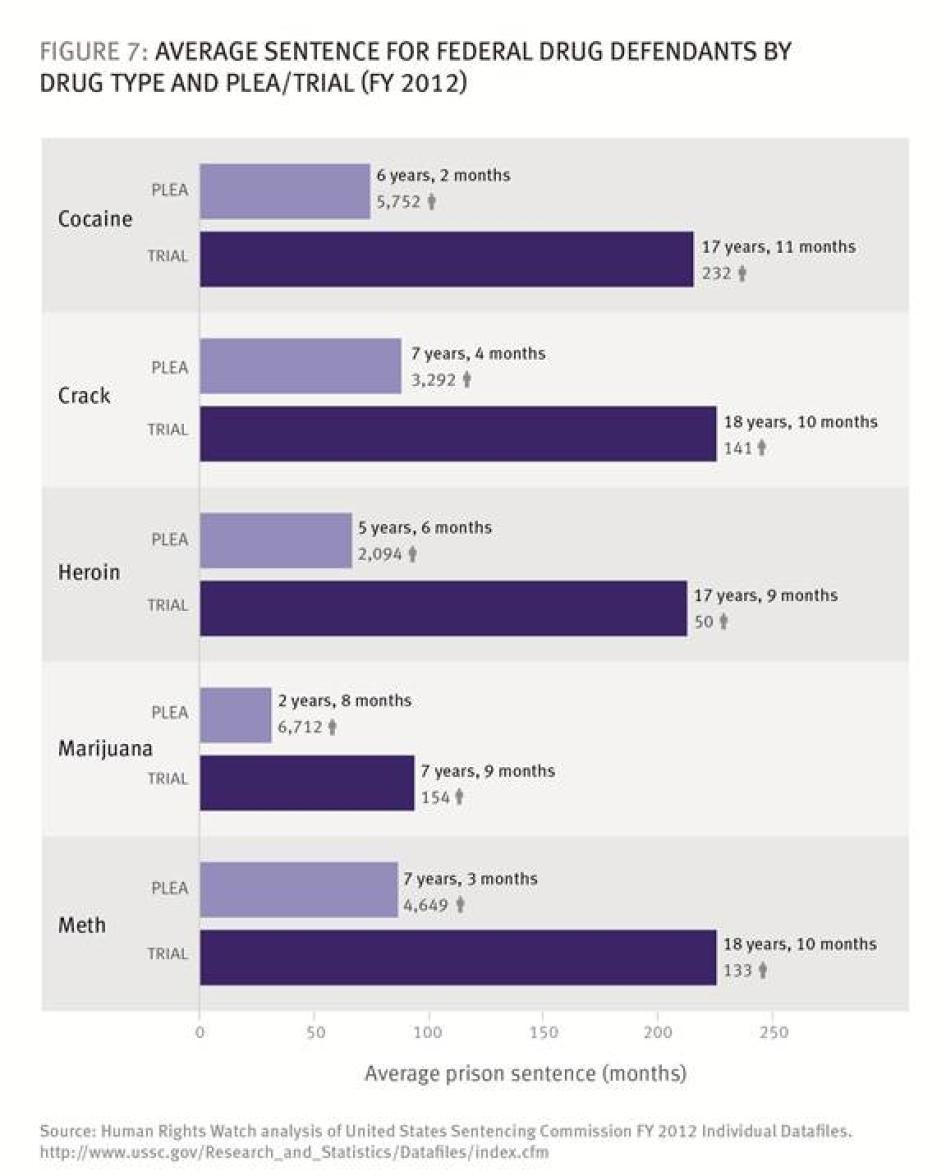

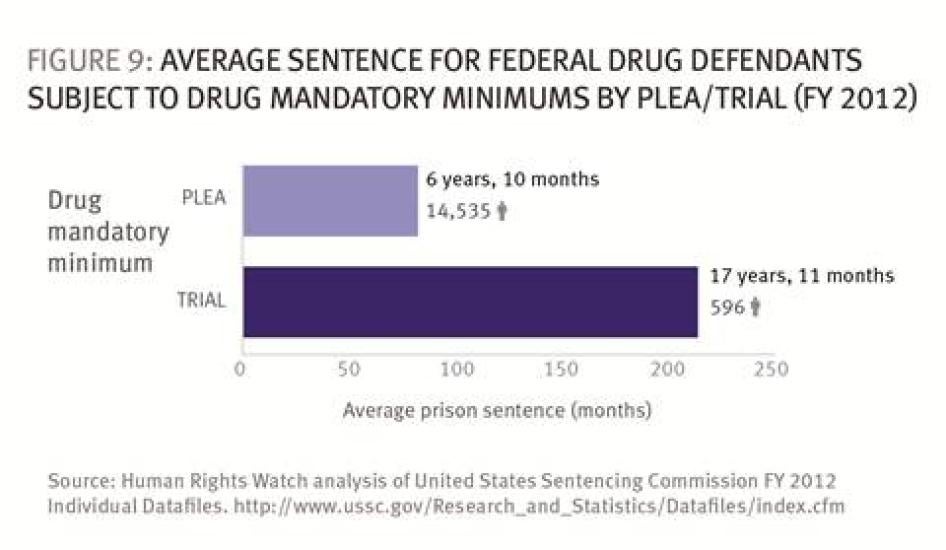

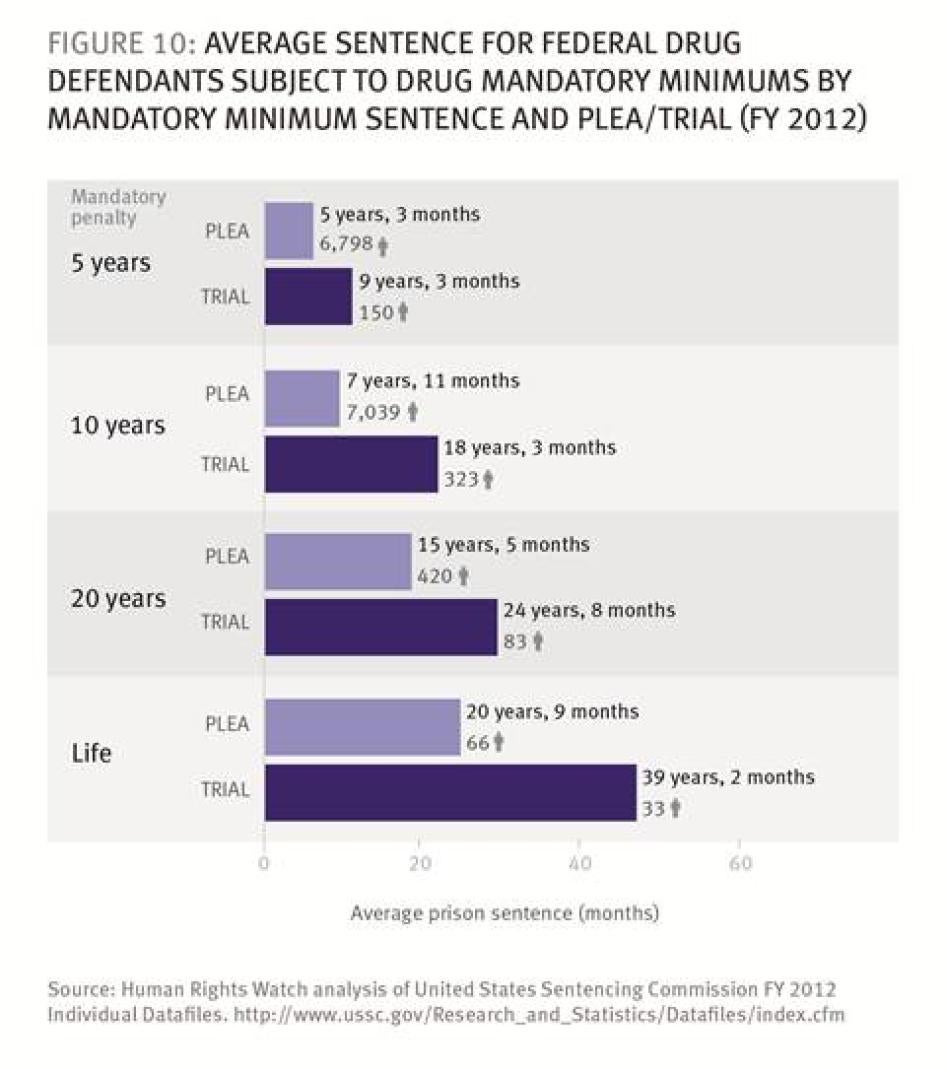

- Defendants convicted of drug offenses with mandatory minimum sentences who went to trial received sentences on average 11 years longer than those who pled guilty (215 versus 82.5 months).

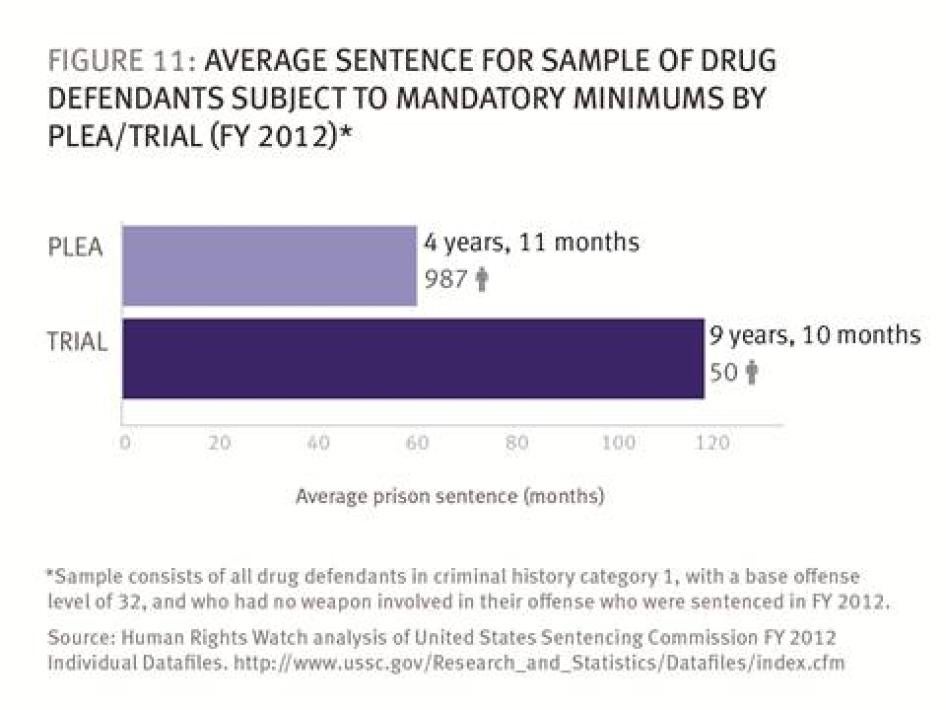

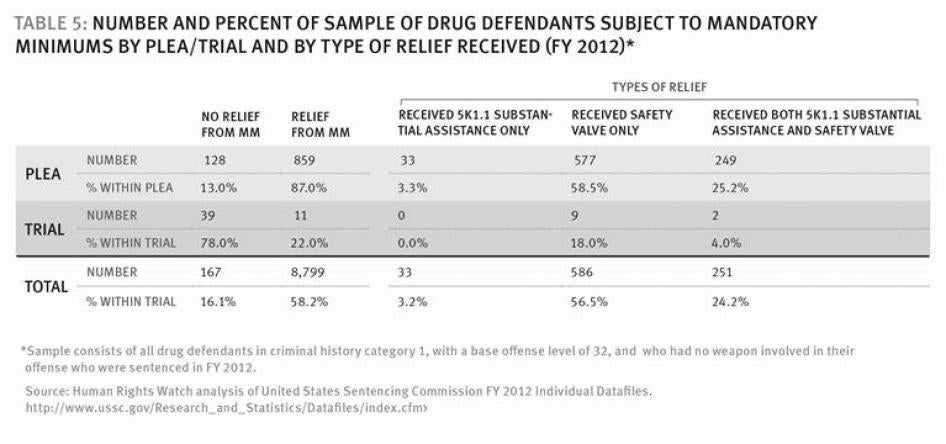

- Among first-time drug defendants facing mandatory minimum sentences who had the same offense level and no weapon involved in their offense, those who went to trial had almost twice the sentence length of those who pled guilty (117.6 months versus 59.5 months).

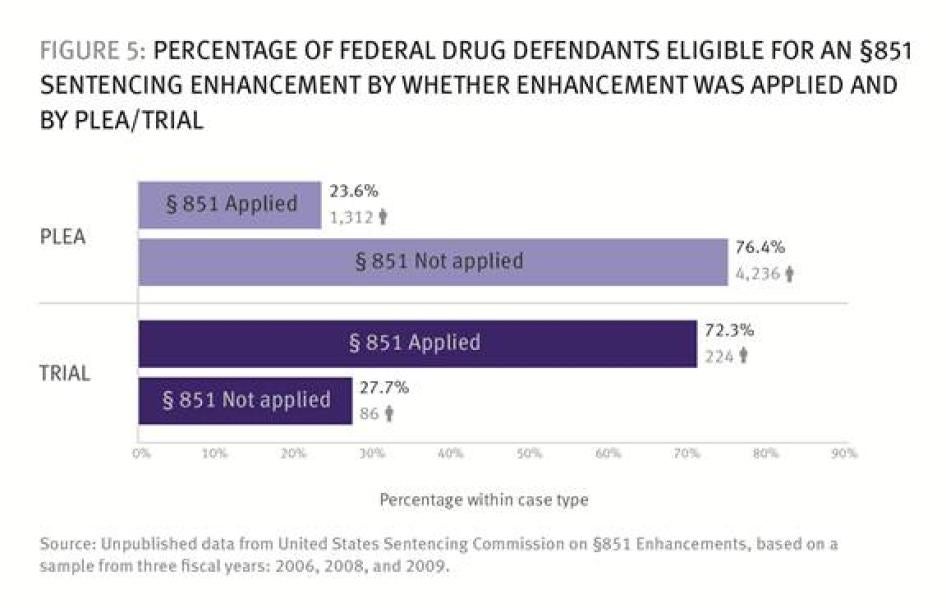

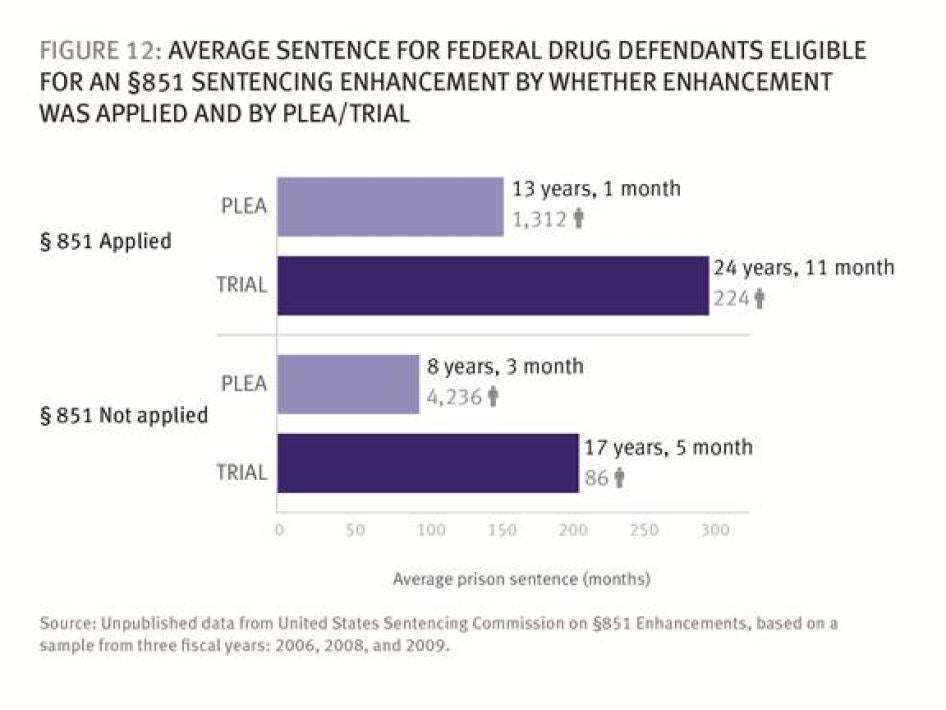

- Among defendants who were eligible for a sentencing enhancement because of prior convictions, those who went to trial were 8.4 times more likely to have the enhancement applied than those who plead guilty.

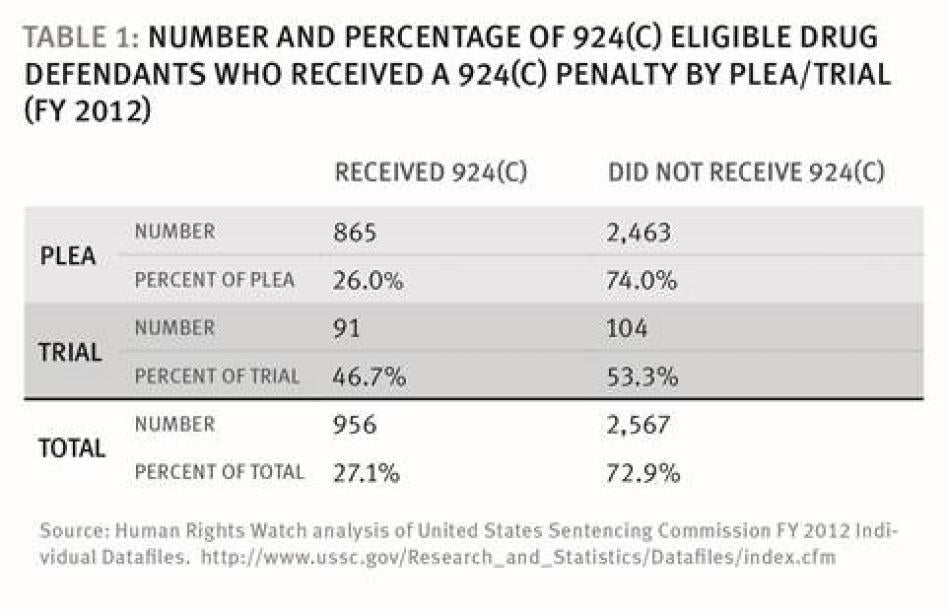

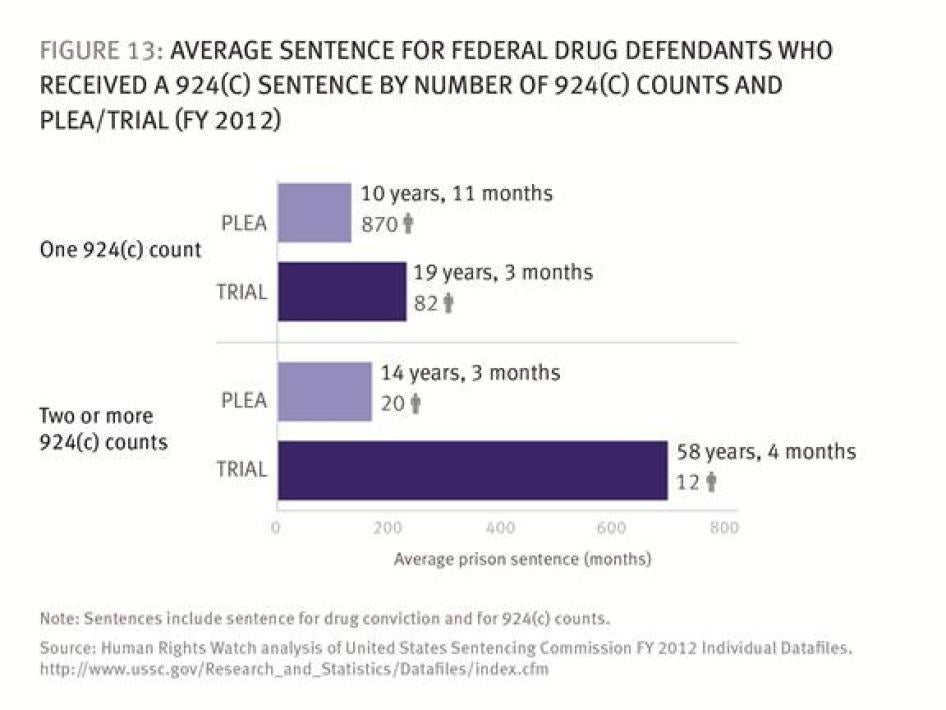

- Among drug defendants with a weapon involved in their offense, those who went to trial were 2.5 times more likely to receive consecutive sentences for §924(c) charges than those who pled guilty.

These statistics cannot fully capture the leverage that prosecutors exert over individual defendants during plea bargaining. If a prosecutor’s threats are made orally, there may be no written record of them. During hearings, when the judge makes a decision whether to accept a plea agreement, it is rare for prosecutors, defense counsel, or defendants to mention the sentencing risk defendants faced if they did not plead.

The following case exemplifies the dire consequences that result when prosecutors made good on their threats to pursue increased sentences for a defendant who refuses to plead. A prosecutor who was willing to accept a plea that gave the defendant a 10-year sentence, was willing to have her sentenced to life without parole because she insisted on going to trial.

Sandra Avery[8]Sandra Avery was a survivor of childhood sexual abuse who served in the army and the army reserves, earned a college degree, overcame an addiction to crack, became a born-again Christian, and worked as an accountant. But in her early forties, her life spun out of control: she became addicted to crack cocaine again, lost her job, and started delivering and selling small amounts of crack for her husband, a crack dealer. In 2005, Avery was arrested and indicted by a federal grand jury for possessing 50 grams of crack with intent to deliver, an offense then carrying a mandatory minimum sentence of 10 years. Avery refused to enter into a plea agreement with the government because it did not offer anything less than 10 years and because, as she says, “I simply was not in my right mind at the time.” She was convicted after trial, and sentenced to life. Because there is no parole in the federal system, she will remain in prison until she dies. The life sentence resulted from the government’s choice to trigger a sentencing enhancement based on Avery’s previous drug convictions. During the early 1990s, she had been convicted three times under Florida law for possessing small amounts of crack for her personal use; she told Human Rights Watch that the value of drugs in those three cases amounted to less than $100 and she was sentenced to community supervision. When Human Rights Watch asked Avery’s prosecutor why he sought the enhancement in her case, he said “because it applied.” He said the policy in his office is to seek such enhancements whenever they are applicable, although there is “room to negotiate” if a defendant pleads guilty and agrees to cooperate with the government. His office policy also permits prosecutors to seek approval from their superiors not to file for the enhancement, which did not happen in Avery’s case. Asked whether he thought Avery’s life sentence was just, he refused to comment. |

A Call for Federal Reform

In an August speech to the American Bar Association, Attorney General Eric Holder endorsed the need to reform federal sentencing laws and practices to reduce the number of people sent to prison and the length of their sentences.

Identifying “just sentences” for low-level, nonviolent drug defendants as a Department of Justice priority, Holder issued a memorandum to federal prosecutors instructing them to avoid charging offenses carrying mandatory minimum sentences for certain low-level, nonviolent offenders. He also directed prosecutors to avoid seeking mandatory drug sentencing enhancements based on prior convictions when such severe sentences are not warranted.

It is too soon to tell how prosecutors will carry out the new policies: they contain easily-exploited loopholes and do not prohibit prosecutors from pursuing harsh sentences against a defendant who refuses to plead. Moreover, there is no remedy if prosecutors ignore the letter or spirit of Holder’s policies. If a defendant is convicted, the judge must impose the applicable mandatory minimum sentence or sentencing enhancement sought by the prosecutor.

A recent case in which the defendant was sentenced after Holder issued his memorandum suggests some prosecutors may continue to seek egregiously long sentences for drug defendants who refuse to plead.

Roy Lee Clay[9]On August 27, 2013, a federal court sentenced part-time house remodeler, Roy Lee Clay, 48, to life behind bars without possibility of parole. He was convicted after trial of one count of conspiring to distribute one kilogram or more of heroin—a crime that normally carries a 10-year sentence. Prosecutors asserted he was part of a 14-person heroin trafficking group centered in Baltimore, Maryland, and that for two-and-a-half years, Clay distributed heroin to other dealers and to users as well. There was no evidence in his case that he used violence to further his drug activities. Clay had two prior drug convictions: a 1993 federal conviction for possession with intent to distribute 100 grams of a mixture containing heroin for which he was sentenced to 87 months in prison, and a 2004 state conviction for possession with intent to distribute controlled substances. The government offered to let Clay plead to 10 years on the drug charges. It also threatened to file an information with the court seeking a penalty enhancement to life based on the two prior convictions if Clay insisted on going to trial. He rejected the plea offer and went to trial, which ended with a hung jury. The government renewed the 10-year plea offer, but Clay again refused. After the second trial, Clay was convicted. The government made good on its threat and sought the mandatory enhancement based on the two prior convictions. Previously willing to accept a 10-year sentence, prosecutors ensured Clay would spend the rest of his life behind bars. At his sentencing, Judge Catherine Blake called the life without parole sentence “extremely severe and harsh.” [10] One prosecutor in the case told Human Rights Watch he thought the life sentence was consistent with the Attorney General’s August 2013 memorandum instructing prosecutors to seek prior conviction enhancements only in cases in which such severe sanctions are appropriate. Still, he refused to explain why he thought Clay deserved a life sentence. |

Looking Ahead

As an organization dedicated to enhancing respect for and protection of human rights, Human Rights Watch insists that individuals who violate the rights of others be held accountable for their crimes. We also insist that all people accused of crimes have fair legal proceedings to determine their guilt.

Plea agreements do not necessarily violate human rights; defendants may choose to give up their right to trial in return for a sentencing concession. Nevertheless, plea bargaining as practiced in US federal drug cases raises significant human rights concerns. It is one thing for prosecutors to offer a modest reduction of otherwise proportionate sentences for defendants who plead guilty and accept responsibility for their offense. Such a discount does not offend human rights.

But the threat of a large trial penalty is unavoidably coercive and contrary to the right to liberty and to a fair trial. In some cases, the sentences imposed on drug defendants who refused to plead are so disproportionately long they qualify as cruel and inhuman.

Momentum is growing to end nearly three decades of harsh sentences for federal drug offenders amid growing realization that the US cannot incarcerate its way out of drug use and abuse, and that long sentences neither ensure public safety nor strengthen communities. There is also growing and welcome national recognition that meaningful reform of federal drug laws must include restoring sentencing discretion to federal judges.

We believe Congress should eliminate mandatory minimum drug sentences: the one-size-fits-all approach of the mandatory minimum statutes prevents sentences tailored to the individual case. Congress should also eliminate mandatory penalties based on prior convictions or guns. With sentencing guidelines and appellate review to keep judicial sentencing discretion within appropriate bounds, there is no need for mandatory punishments that primarily serve to coerce defendants into pleading guilty, an unacceptable exercise of government power.

A sound criminal justice system, like all forms of good government, needs checks and balances. Prosecutors should have charging discretion and be encouraged to exercise it carefully and fairly. But the final say over sentences defendants receive must come from independent federal judges who have no personal or institutional stake in the outcome of a case other than to ensure justice is done and rights are respected. Judges with sentencing discretion could end the disgraceful trial penalty in federal drug cases and ensure defendants receive sentences reflecting their crimes, not their willingness to plead.[11]

Recommendations

Human Rights Watch offers the recommendations below to end the prosecutorial practice of coercing drug defendants into guilty pleas with threats of draconian sentences. Our recommendations address both the need for reform of the federal sentencing regime and the need for constraints on prosecutorial plea bargaining practices.

Our most important recommendation is for Congress to restore sentencing discretion to the federal judiciary. While mandatory punishment is not the only factor that convinces defendants to plead guilty, there is no question prosecutors coerce many pleas because they can threaten exorbitant mandatory sentences for defendants who go to trial. If federal judges had authority to review and revise drug sentences to ensure they satisfy the requirements of justice, it would diminish the power of prosecutorial threats.

Our recommendations would not eliminate plea bargaining. Prosecutors could offer modest sentence reductions to reward defendants who choose to plead guilty. But prosecutors would no longer be able to force defendants to plead to avoid grotesquely long sentences. They would be required to charge offenses carrying sentences proportionate to the defendant’s crime and culpability, they would be limited in the extent of the discount from those sentences that could be offered in exchange for the defendant’s willingness to plead guilty, they would be prohibited from threatening superseding indictments with higher charges in order to secure a plea and, finally, they would be prohibited from filing such indictments to punish defendants who refuse to plead.

To Congress

- End mandatory minimum drug sentences and

restore to judges the ability to calculate proportionate sentences in all drug

cases, taking into account the sentencing guidelines for federal drug

defendants. Congress should enact legislation to:

- Abolish federal mandatory minimums for drug offenders based upon the quantity of the drug involved.

- Abolish mandatory sentence increases based on the number and nature of prior convictions.

- Abolish mandatory consecutive sentences for drug defendants who use, carry, or possess firearms in connection with their drug crime.

To the Attorney General

- Establish just sentences as a Department of Justice goal for all drug offenders regardless of whether they plead guilty or go to trial. Define just sentences as those which are proportionate to the defendant’s individual conduct and culpability and which are no longer than necessary to further the purposes of punishment in each individual case.

- Direct prosecutors to seek indictments only for charges that would yield a fair and proportionate sentence for each individual defendant in light of the facts known about that defendant. If an offense carrying a fair sentence has been charged, prosecutors may offer a modest sentencing benefit to reward a defendant for pleading guilty, but should not offer to reduce the defendant’s sentence to such an extent as to coerce the defendant into waiving the right to trial. We urge the Department of Justice to establish parameters for what such a modest reward might be. In addition, the Department of Justice should explicitly prohibit prosecutors from: 1) threatening higher sentences to secure pleas from drug defendants and 2) filing superseding indictments that raise the sentence faced by a defendant solely because the defendant refused to plead guilty.

Methodology

This report is based on the following sources of information: interviews; federal cases, legal articles, and other literature on drug cases and plea bargaining; and sentencing statistics.

Human Rights Watch interviewed scores of individuals with deep knowledge of federal sentencing practices, including 7 federal district judges, 4 current or former US Attorneys, 18 current or former assistant US attorneys, and 40 federal public defenders and defense counsel in private practice (not including former prosecutors now in private practice). We also talked with academics and public policy advocates and corresponded with a handful of federal prisoners serving sentences for drugs. The names of most current and former prosecutors and private attorneys have been kept confidential at their request.

We reviewed court decisions and documents filed in hundreds of cases. The documents filed in individual court cases were available through PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records). Unfortunately, plea bargains were often not available to view on PACER. Similarly, documents that refer to or reflect cooperation with the government by a defendant are often sealed and not available to view. Presentencing reports filed by probation officials are also confidential and not available for public viewing on PACER.

All statistics in this report regarding the sentencing of federal drug defendants originated in sentencing data maintained or published by the United States Sentencing Commission (the Sentencing Commission). Where possible, we relied on relevant data published by the Sentencing Commission in various reports and documents. We used data available from the Sentencing Commission’s publically accessible Monitoring Datafile for Fiscal Year 2012 to develop findings regarding the sentencing consequences for federal drug offenders of pleading guilty versus going to trial. Analysis was limited to federal drug defendants for whom the Sentencing Commission received full documentation from the courts. Of the 26,560 drug offenders in the Sentencing Commission’s files for fiscal year 2012, there was enough data to analyze 24,765 or 93 percent of them.

We also used unpublished data, developed by the Sentencing Commission, on the proportion in each federal district of drug defendants eligible for prior drug conviction enhancements and the rate at which such enhancements were applied to eligible defendants. We also used commission data on the average sentences for defendants based on whether they were convicted by plea or after trial and by whether the sentencing enhancement was applied. The Sentencing Commission developed this data by analyzing samples of 3,050 cases from fiscal year 2006, 5,434 cases from fiscal year 2008, and 5,451 cases from fiscal year 2009.[12] The Sentencing Commission provided the data to Judge Mark Bennett, who used them in a recent decision and shared it with us.[13]

I. Federal Drug Sentencing and Swollen Federal Prison Populations

Since the modern day anti-drug effort began in the mid-1980s, vigorous federal drug law enforcement and harsh sentences have fueled the soaring federal prison population and resulted in large numbers of prisoners serving long drug sentences in federal prisons.[14]

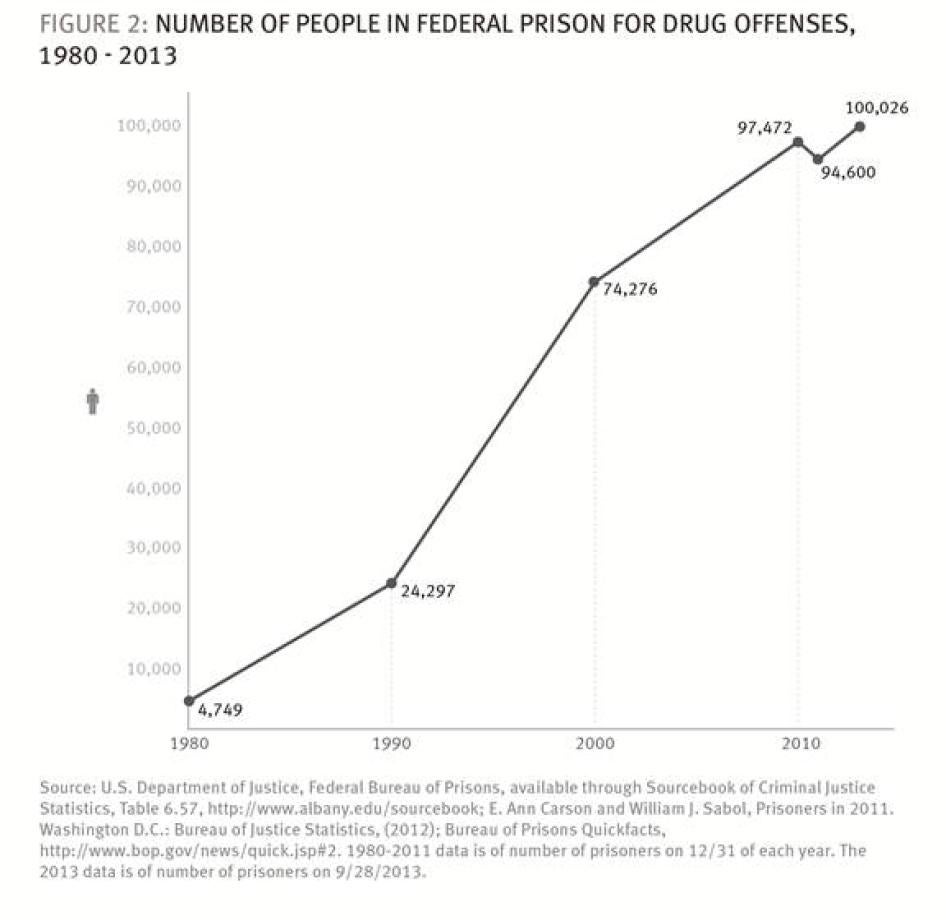

Between 1980 and 2013, the number of incarcerated federal drug defendants soared from 4,749 to 100,026—an astonishing 2,006 percent. As of September 28, 2013, half—50.1 percent—of all federal prisoners were serving time for drug offenses.[15] In fiscal year 2012 alone, 26,560 men and women were convicted of federal drug crimes.[16]

Counter to popular belief, most drug offenders are not kingpins or the most serious drug offenders. As one former US Attorney told Human Rights Watch,

The public simply does not realize how many low-level guys are in [federal] prison.… We lock up the lowest fruit in drug conspiracies. I once asked another US Attorney with 30 years as a prosecutor how many times he’d put a major drug player in prison. He said he could count them on one hand.[17]

In fact, the most common functions of convicted federal drug defendants were courier (23 percent), followed by wholesaler (21.2 percent) and street-level dealer (17.2 percent), according to an analysis of drug offender function by the Sentencing Commission.[18] The Sentencing Commission has also calculated that 93.4 percent of federal drug defendants were in the lower or middle tiers of the drug business.[19] In 2012, 85 percent of drug defendants had no weapon involved in their offense, a crude proxy for determining whether the defendant’s conduct was violent.[20] Fifty-three percent had either an insignificant or no state or federal criminal history.[21]

The average federal drug sentence has increased 250 percent since 1987 when the Sentencing Commission published its guidelines.[22] In 2012, the average sentence length for all defendants sentenced for federal drug trafficking offenses was 68 months.[23] The Urban Institute, a private research and policy organization, has calculated that the increase in sentence length for federal drug offenders “was the single greatest contributor to growth in the federal prison population between 1998 and 2010.”[24]

The federal government and the states have overlapping laws establishing criminal sanctions for drug-related conduct, and federal law enforcement agents and prosecutors do not have to defer to state prosecutions.[25]

There are 94 districts in the federal criminal justice system. Prosecutors in each district operate under the same federal statutes defining crimes and setting out criminal procedures, and are subject to policies set by the Department of Justice.

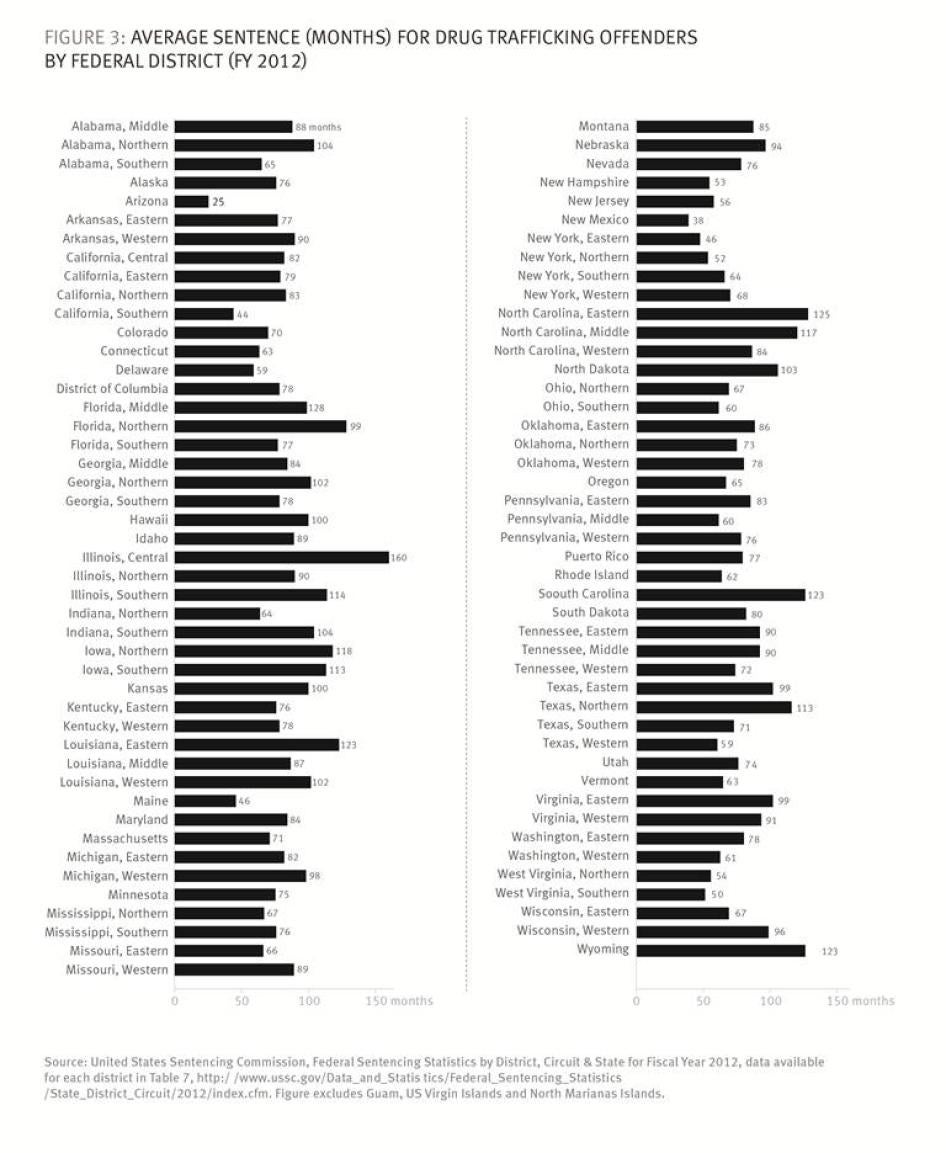

But each district office also has considerable autonomy, its own internal policies and culture, and its own ways of dealing with the local defense bar (which will also have its distinctive characteristics) and the particularities of the federal judges. The data we compiled for this report shows striking variation in the average sentences for federal drug offenders convicted of trafficking offenses across the federal districts (Figure 3).[26]

As seen in Figure 3, the average prison sentence was over 11 years longer in the central district of Illinois—the district with the highest average sentence—than in Arizona, the district with the lowest. The data and our research suggest that the differences to some extent reveal different policies and practices with regard to charging and plea bargaining.[27]

II. Federal Sentencing: Mandatory Sentences and Sentencing Guidelines

Sentencing guidelines and mandatory minimums deny the reality of life; they substitute formulas for reality.

—Judge Jed S. Rakoff, New York, March 18, 2013

In the mid-1980s, Congress dramatically changed sentencing in federal criminal cases. Seeking certainty, uniformity, and severity, Congress stripped the federal judiciary of its ability to determine sentences in federal drug cases by establishing a sentencing regime of mandatory minimum sentences and mandatory sentencing guidelines. Somewhat inconsistently, it also instructed federal judges to impose sentences that were “not greater than necessary” to further punishment: i.e. retribution, incapacitation, deterrence, and rehabilitation.[28]

The new sentencing regime required longer sentences for federal drug offenders.[29] This, coupled with the abolition of federal parole in 1984, resulted in a remarkable increase in the time that federal drug offenders spend behind bars: from 1984 to 1991, their average prison time leaped from less than 30 to nearly 80 months.[30]

Whether a defendant is convicted by plea or after trial, the sentencing judge will impose a sentence based on statutorily mandated sentences and the sentencing guidelines. The guidelines are no longer mandatory, but judges must still take them into consideration when setting a sentence. If a defendant is convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum sentence, the judge cannot sentence below that minimum unless the defendant either qualifies for an exemption under the so-called safety valve, or the government files a motion to waive the minimum because the defendant has provided substantial assistance to the government (see below in Section IV).

Sentences higher than the minimum can be imposed up to the maximum sentence permitted by statute. When a defendant is charged with offenses that do not carry mandatory minimum sentences, or if the defendant qualifies for relief from the minimum, then the judge sets the sentence by looking to the guidelines, and taking into account Congress’ sentencing directives.[31]

This section examines statutory minimum sentences that are keyed to the weight and type of drug, and how they were incorporated into the sentencing guidelines. Section III addresses provisions that trigger higher sentences for drug offenders based on their prior convictions or the use or possession of guns related to the drug offense.

Mandatory Minimum Drug Sentences

[Mandatory minimum sentences] are cruel, unfair, a waste of resources, and bad law enforcement policy. Other than that they are a great idea.[32]

—Former Federal District Judge John S. Martin, Jr. in Notre Dame Journal of Law

The punishment is supposed to fit the crime, but when a legislative body says this is going to be the sentence no matter what other factors there are, that’s draconian in every sense of the word. Mandatory sentences breed injustice.[33]

—Senior United States District Judge Roger Vinson, as quoted in The New York Times, December 12, 2012

With the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 (ADAA), Congress enacted a mandatory minimum sentencing regime for federal drug crimes keyed to the weight and type of drug involved in the offense.[34] Passed with little deliberation or preparation,[35] the harsh new regime reflected the ascendancy of “tough on crime” policies, concern about drugs, violence, and racial tensions, and the belief severe sentences were needed to restore law and order.[36]

The centerpiece of the new drug sentencing scheme is five- and ten-year mandatory minimum sentences for drug trafficking—a term that encompasses possession with intent to distribute, distribution, or manufacturing.[37] Under current law, for example, a 10-year mandatory minimum sentence with a maximum term of life imprisonment is triggered by drug trafficking offenses involving 5 kilograms of powder cocaine, 280 grams of crack cocaine, or 50 grams of pure methamphetamine. A five-year mandatory minimum sentence with a maximum of forty years is triggered, for example, by 500 grams of powder cocaine, 28 grams of crack, or 5 grams of pure methamphetamine.

When it enacted the ADAA, Congress apparently thought the weight of the drugs involved would be a reasonable proxy for the drug trafficking role.[38] Unfortunately, it got the numbers wrong: even low-level offenders distribute the quantities that garner the five- and ten-year minimum sentences Congress intended for more serious traffickers.[39] According to a 2011 Sentencing Commission analysis, “the quantity of drugs involved in an offense was not closely related to the offender’s function in the offense.”[40] Federal prosecutors do not, however, limit charges carrying mandatory sentences to the drug offenders Congress had in mind. The Department of Justice,

[h]as turned a law that sought to impose enhanced penalties on a select few into a sentencing regime that imposes them on a great many, producing unfairly harsh consequences that Congress did not intend.[41]

Sixty percent of federal drug offenders sentenced in fiscal year 2012 were convicted of charges carrying a mandatory minimum sentence for their drug offense.[42] We do not know how many of the remaining 40 percent of defendants were originally charged with offenses that carried a minimum sentence reduced to non-mandatory minimum offense due to a plea bargain. From 1995 to 2010, the proportion of drug offenders in federal prison convicted of offenses carrying mandatory minimum penalties rose from 78.2 to 84.6 percent.[43]

In 2010, Jamel Dossie, a 20-year-old, small-time street-level drug dealer’s assistant earned about $140 acting as a go-between in four hand-to-hand sales totaling 88.1 grams or 3.1 ounces of crack. He was a “mope”—a person occupying the lowest rungs in the drug business. Prosecutors could have charged him under a statute that carried a sentencing range of 0 to 20 years.[44] Instead, they charged him with an offense carrying the five-year mandatory minimum sentence intended for mid-level offenders.[45] Judge John Gleeson felt a five-year sentence was “too severe” for a low-level addict selling drugs on the street, but was nevertheless required by the sentencing law to impose it.[46]

Conspiracy Laws: Ratcheting up the Drug Quantity

Conspiracy to commit a drug crime carries the same mandatory sentence as the underlying substantive crime.[47] Conspiracy law is complicated, but the bottom line is that prosecutors may charge defendants who are members of a drug conspiracy with a much greater quantity of drugs than they individually possessed or distributed, thereby ratcheting up the sentences they face and increasing the pressure on them to plead guilty.

A drug defendant can be treated as a co-conspirator if he knowingly and willingly entered into an agreement with one or more people to commit a narcotics related crime. As a co-conspirator, a defendant can be sentenced based on the amount of drugs possessed or distributed by the other members within the scope of the defendant’s agreement, as long as he knew or could reasonably have foreseen the amount. He does not have to be a leader or major player in the conspiracy; a minor role suffices to establish his responsibility.[48] Not surprisingly, as many cases in this report illustrate, prosecutors often charge drug defendants with conspiring to distribute drugs. They may then offer plea agreements that eliminate the conspiracy charge or otherwise reduce the quantity for which the defendant is held legally responsible.

Natacha Jihad Pizarro-Campos[49]Natacha Jihad Pizarro-Campos grew up in Puerto Rico and at the age of 20 moved to Florida. She was the mother of a young boy and had a history of mental illness and drug addiction. When Pizarro-Campos turned 21, she began working in a bar where she met Rafael Hernandez, a successful drug dealer. When Pizarro-Campos gave birth to a baby who died in a tragic accident, Hernandez paid for the funeral expenses. He also paid for Pizarro-Campos’ living expenses and supplied her with unlimited quantities of drugs for her personal use. In turn, he expected her to help him with his drug operation. One of the customers to whom she sold drugs on his behalf turned out to be a confidential informant. In June 2010, federal prosecutors in the Middle District of Florida secured an indictment against Pizarro-Campos and other defendants, charging them with conspiracy to distribute and possession with intent to distribute 500 grams or more of a substance containing methamphetamine. Pizarro-Campos pled guilty. In her plea agreement, Pizarro-Campos stipulated that she and others conspired to distribute between 1.5 and 5 kilograms of a mixture containing methamphetamine. She personally sold a total of 406.7 grams of methamphetamine in 5 transactions in 2009 and 2010. Under the guidelines, her sentence range for selling that amount would have been 70 to 87 months. But she had pled guilty to conspiracy to distribute 500 grams or more, which was punishable by a minimum prison term of 10 years and a maximum of life. She was sentenced to 10 years. |

Anthony Bowens[50]Anthony Bowens was one of 43 people indicted in 2005 for alleged participation in a multi-year crack conspiracy operating in a New York City public housing project. Bowens worked as a “pitcher,” collecting money from customers and providing them with the purchased cocaine in transactions arranged by his bosses. He had no managerial or supervisory role in the conspiracy. Bowens apparently joined the conspiracy in December 2003, at the tail end of the conspiracy’s 11-year history. The indictment set forth a single overt act involving Bowens, the sale of approximately 63 vials of crack on or about May 11, 2004.[51]As a member of a conspiracy that allegedly distributed 50 grams or more of crack, Bowens faced a 10-year mandatory minimum sentence and a guidelines range of 19.6 to 24.4 years (235 to 293 months).[52]Prosecutors gave Bowens a plea offer under which he would be permitted to plead guilty to a single count to distribute and possess with intent to distribute crack, an offense carrying a 5-year mandatory minimum sentence and a stipulated guidelines range of 70 to 87 months.[53]Owens chose to go to trial. The prosecutors could have filed a superseding indictment taking Bowens out of the conspiracy and simply charging him with possession with intent to distribute, but they did not. Bowens was convicted after a jury trial on the original conspiracy charge carrying a 10-year mandatory minimum. The government sought a sentence for Bowens within the guidelines range of about 19 to 24 years (235-293 months), a range predicated on a drug quantity of 1.5 kilograms of crack. Such a sentence would have greatly exceeded the sentences secured by defendants with similar roles in the conspiracy who pled guilty.[54] The judge sentenced him to 15 years, a sentence subsequently reduced to 12 years following the retroactive changes in 2010 to the guidelines for crack cocaine offenses. |

Mandatory Minimums: A Bad Idea at Best

When judges with lifetime tenure quit over the unfairness of [mandatory minimum] sentences, when dozen[s] of former federal prosecutors petition Congress to change such sentences, and when defense lawyers inundate the Executive Branch with complaints and pleas for clemency, it is clear that the downside of such sentences eclipses their usefulness in our federal sentencing scheme.[55]

—Professor Laurie L. Levenson, Loyola Law School, May 27, 2010

Mandatory minimums are one of the most significant obstacles to fair sentencing in the criminal justice system.Justice Anthony Kennedy has stated, “I can accept neither the necessity nor the wisdom of federal mandatory minimum sentences. In too many cases, mandatory minimum sentences are unwise and unjust.”[56] Many members of the judiciary agree.[57] Prosecutors also recognize the problems with mandatory minimums.[58] Scott Lassar, a former US Attorney, bluntly told Human Rights Watch, “Mandatory minimums lead to unfair sentences.”[59] In testimony before the Sentencing Commission, Federal Public Defender Michael Nachmanoff stated, there is “overwhelming evidence that mandatory minimums require excessive sentences for tens of thousands of less serious offenders who are not dangerous.”[60]

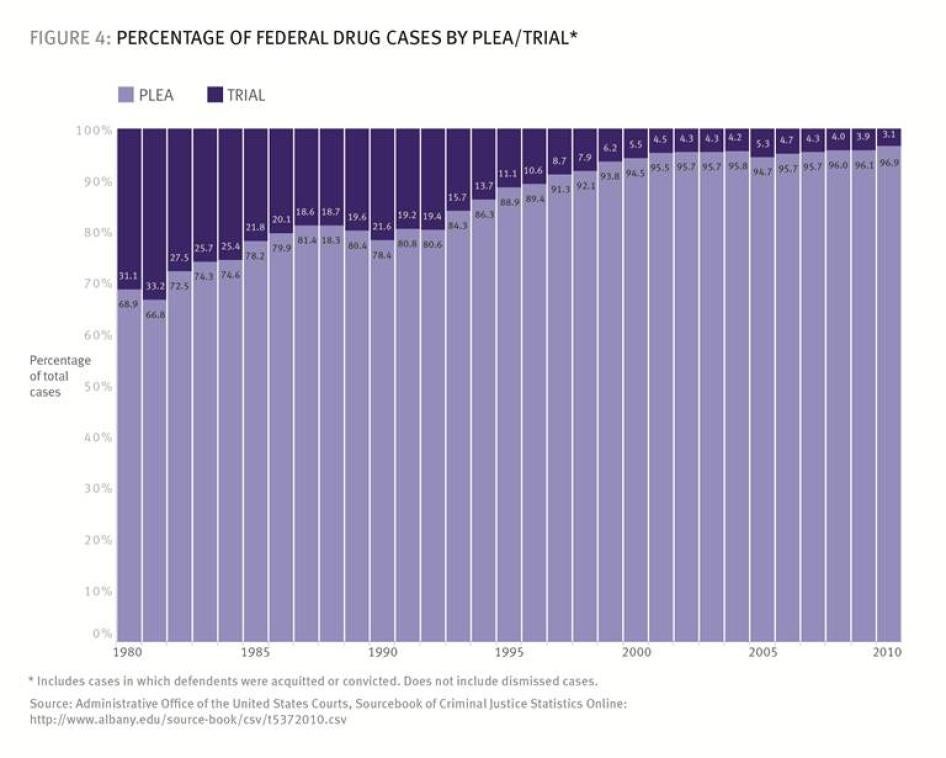

Mandatory minimum sentencing laws increased prosecutorial power, transferring sentencing power from judges to prosecutors.[61] Previously, federal prosecutors “played no role in sentencing.”[62] But with judges’ sentencing discretion curtailed, prosecutors could determine the sentences defendants would face through the charges they pressed and the facts they brought forward at sentencing.[63] Unfortunately, prosecutors often charge or threaten to charge mandatory minimums not because they result in appropriate punishment, even in the view of the prosecutor, but to pressure defendants to plead guilty and to punish them if they do not. The pressure they could bring to bear on defendants led to soaring numbers of guilty pleas in drug cases: from 1980 to 2010, the percentage of federal drug cases resolved by a plea increased from 68.9 to 96.9 percent, where it remained in 2012 (Figure 4).[64]

Supporters of mandatory minimum sentences believe they ensure uniformity and certainty—offenders who commit similar crimes receive similar punishment; transparency—offenders and the public know what the punishment for the crime is; crime prevention—the certainty and harshness of the punishment deters future crime; and encourage pleas and cooperation with the government. The problem with all but the last of these justifications is that they are belied by the facts.[65]

The only indisputable effect of mandatory minimums is that they help pressure defendants into pleading guilty and cooperating with the government.[66] A former assistant US attorney described mandatory minimums as “a hammer to convince people to cooperate…. They provide a practical benefit for prosecutors but can create unfair consequences for defendants.”[67] A current assistant US attorney made a similar point: “Mandatory minimums really help get defendants to cooperate.”[68]

The Department of Justice has traditionally supported high mandatory sentences because “the threat of the higher sentence provides a greater inducement for defendant cooperation.”[69] According to Lanny Breuer, a former assistant attorney general, the Department of Justice favors mandatory minimum sentences because they “remove dangerous offenders from society, ensure just punishment, and are an essential tool in gaining cooperation from members of violent street gangs and drug distribution networks.”[70]

In the words of Justice Kennedy, this “transfer of sentencing discretion from a judge to an Assistant U.S. Attorney, often not much older than the defendant, is misguided.” It “gives the decision to an assistant prosecutor not trained in the exercise of discretion and takes discretion from the trial judge…, the one actor in the system most experienced with exercising discretion in a transparent, open, and reasoned way.”[71]

Sentencing Guidelines

Over twenty-five years of application experience have demonstrated that the drug trafficking offense guideline is unnecessarily severe and produces unjust outcomes.[72]

—Judge John Gleeson, United States v. Diaz, 2013

For the government, the guidelines are sacrosanct. Prosecutors insist they must be followed – except they will bend them whenever it suits their purposes.[73]

—Gerald McMahon, New York, July 1, 2013

Congress created the United States Sentencing Commission (the Sentencing Commission) in 1984, charging it with promulgating sentencing guidelines for all federal crimes.[74] The guidelines were to further the purposes of sentencing (just punishment, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation) set forth in 18 U.S.C. §3553(a)(2), while avoiding unwarranted disparities among similar defendants.[75]

The Sentencing Commission has created detailed and complicated guidelines that culminate in a prescribed sentencing range (calculated in months) for every federal crime using a Sentencing Table that combines offense seriousness with the defendant’s criminal history.[76] The seriousness of the offenses are measured by 43 offense levels on the vertical axis of the Sentencing Table and six criminal history categories on the horizontal axis. The base offense level for drug offenses is initially set by the type and weight of the drug involved, pegged to the mandatory minimum sentences established under the ADAA.[77] Numerous aggravating factors can increase the base offense level and a few mitigating factors can reduce it.[78] After adjusting the base offense level to reflect aggravating and mitigating factors, a final offense severity level is determined. The sentencing range for the defendant is ultimately determined by the cell in the Sentencing Table that lies at the intersection of final offense severity level and his criminal history category.[79]

Given that the drug guidelines were established to be proportionate to the statutory mandatory minimum sentences, now widely recognized as excessively severe, it is no surprise that the guidelines also yield egregiously long sentences.[80] For example, street-level dealers who sell to retail customers can easily distribute 300 grams of crack or 500 grams of methamphetamine in a month, with a retail value of $20,000 to $50,000.[81] Yet the guidelines sentencing range for a nonviolent, first-time offender distributing this quantity of those drugs to an adult is 10 to 12 years—greater than for forcible rape of an adult, killing a person in voluntary manslaughter, disclosing top secret national defense information, or violent extortion of more than $5 million involving serious bodily injury.[82] Someone who has one prior drug felony conviction, who runs a small drug operation of three people including himself, and who is convicted of possession with intent to distribute 20 kilograms of cocaine faces a guidelines sentencing range of 210 to 262 months (approximately 17 to 21 years).[83]

On February 28, 2012, a federal judge imposed a 12-year guidelines sentence on Dwayne Ingram for selling less than 1 gram of crack (about the equivalent of a sweetener packet) within 1,000 feet of public housing property, following 2 earlier convictions for selling small crack quantities. As federal appellate Judge Guido Calabresi said in a concurring opinion upholding the sentence, “[T]here is nothing ‘reasonable’ about sending a man to prison for twelve years to punish him for a nonviolent, $80 drug sale.”[84]

From Mandatory to Advisory

From 1987 to 2005, the sentencing guidelines dictated federal sentences unless trumped by mandatory minimum statutes.[85] Except in extraordinary and unusual circumstances, federal district judges were not able to impose sentences lower than the guidelines mandated.

In the 2005 decision of United States v. Booker, the Supreme Court held that mandatory sentencing guidelines ran afoul of the Sixth Amendment.[86] Under Booker and its progeny, the guidelines remain “the starting point and initial benchmark” for sentencing calculations.[87] Judges should not, however, presume that a sentence within the guidelines range is reasonable.[88] They should impose different sentences than those specified by the guidelines if they decide a non-guidelines sentence would better satisfy congressional sentencing directives, including the requirement to set sentences no greater than necessary to serve the purposes of punishment.[89] Post-Booker, judges can also avoid the false uniformity that results when drug offenders of widely differing culpability face unreasonably similar guidelines sentences because drug quantity overrides other factors.[90]

Corey James[91]On May 2, 2008, Corey James pled guilty to conspiring to distribute 50 grams or more of crack and cocaine during a two-month period in 2008 and to distributing and possessing with intent to distribute 50 grams or more of crack. The charges arose from three drug deals that James brokered, resulting in the sale of 118 grams of crack and 50 grams of powder cocaine. James received $100 for each sale. Because of James’ record of prior convictions, he had a guidelines sentencing range of between 262 and 327 months (that is, between 21 years, 10 months and 27 years, 3 months). Before Booker, Judge Jack B. Weinstein would have had to sentence James to more than 21 years in prison. But he sentenced James instead to 10 years and one day, giving detailed reasons regarding “the nature and circumstances of the offense and the history and characteristics of the defendant” as required by 18 U.S.C. 3553(a)(1) to explain why the lower sentence was justified. [92] According to Judge Weinstein’s decision, the 42-year-old James had a record of serious crimes, including physical violence and was a known street gang member. But James was in poor health, suffered from long-term drug addiction and depression, and he was sincerely remorseful. The judge concluded the 10-year sentence reflected the seriousness of his offense and would send a message that drug trafficking results in lengthy prison sentences. A longer sentence was not necessary to protect the public since James was unlikely to return to serious criminal activity after prison. |

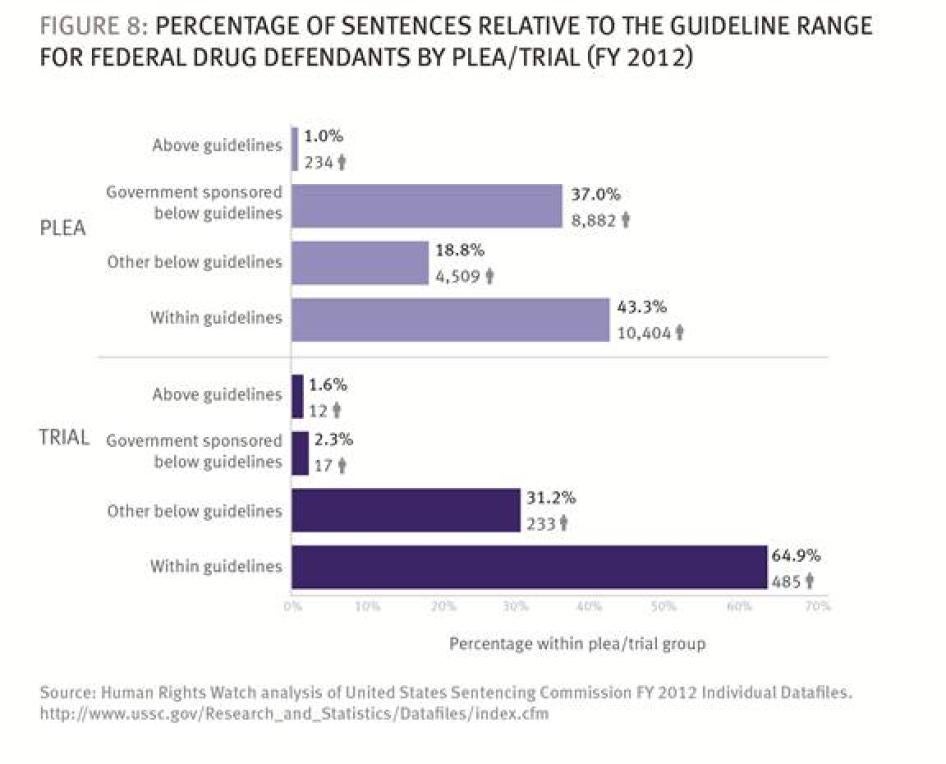

Although the guidelines are no longer binding, most judges still sentence within them unless they have received a government motion for a sentence below the guidelines range, because the defendant has provided substantial assistance or is being prosecuted under a Fast Track program.[93] In fiscal year 2012, 42.9 percent of federal defendants convicted of drug trafficking offenses received sentences within the guidelines range.[94] Judges went below the guidelines without a government motion to do so in only 19.3 percent of drug trafficking cases.[95] The guidelines range is thus the starting and also the ending point for many judges.[96]

Darlene EcklesFor a first time offender, a 19-year sentence; for her drug dealing brother, 12 years[97]Darlene Eckles was arrested on federal narcotics charges in 2006, one of 40 defendants allegedly involved in a drug trafficking business led by her brother, Rick. In late 2003, he needed a place to live after he got out of prison and Darlene permitted him to live with her. Against her wishes, he began operating his drug business out of her home and after a while, she collected and counted money for him. After six months, when her brother would not stop dealing from her house, she kicked him out. He went to live with another sister, and continued his business from her house. A nursing assistant with no criminal record and the mother of a young son, Darlene Eckles’ only involvement with drugs was during the limited time her brother lived with her. The government offered her a plea deal of 10 years for one drug conspiracy count, but she refused to plea, believing she was innocent of drug trafficking. After trial, the jury convicted Darlene of a lesser included drug offense that carried no mandatory minimum. At her sentencing in March 2007, the government argued that she was a “facilitator” of her brother’s drug business, should be held accountable for the full drug weight involved in the conspiracy (1.5 kilograms or more of crack), and should not receive a reduced sentence for her minor role. The judge agreed and calculated her sentencing range under the federal sentencing guidelines as 235 to 293 months. He sentenced her to 235 months— 19 years and seven months—about twice as long as the pre-trial plea offer. Her brother, the conspiracy ring leader, received a sentence of eleven years and eight months after pleading guilty and cooperating with the government, including by testifying against his sister. Darlene’s sister, whose involvement in the conspiracy was the same as Darlene’s, also pled guilty and was a cooperating witness for the government; she received two years’ probation. |

When the guidelines were mandatory, they functioned similarly to mandatory minimum statutes—transferring enormous sentencing authority to federal prosecutors and markedly strengthening their plea bargaining leverage.[98] Prosecutors could charge offenses carrying high guidelines sentences and then use their plea bargaining discretion to circumvent the guidelines in plea agreements.[99]

By making the guidelines advisory, the Supreme Court revived judicial sentencing discretion (subject still to statutory mandatory minimum sentences).[100] Nevertheless, the guidelines remain powerful and prosecutors retain unbridled discretion in deciding what charges to pursue or pleas to accept.

The guidelines themselves encourage defendants to plead guilty by rewarding defendants with a two- or three-level reduction in their offense level for “acceptance of responsibility.” For example, a defendant who has an offense level of 30 and a criminal history category of III faces a sentencing range of 10 to 12-and-a-half years (121 to 151 months). If he pleads, his offense level is automatically reduced to level 28, with a sentencing range of about 8 to 10 years (97 to 121 months). If the government agrees the plea was timely, the offense level will drop one more level, leading to a sentencing range of 7 to 9 years. In other words, by pleading, this defendant would have reduced his sentencing exposure under the guidelines from a possible maximum of 12-and-a-half years to a possible low of 7 years. The guidelines incentive to plead has proven sufficient to maintain high levels of guilty pleas even for offenses that do not carry mandatory minimum sentences.[101]

Efrain Vega[102]Efrain Vega grew up poor in the projects of Hartford, Connecticut with an abusive father, surrounded by violence and alcohol. Nonetheless, he had created a solid life for himself. He had a strong family—a wife and three daughters—and a good full-time job moving and installing office equipment. He was also a recreational cocaine user, who sometimes purchased enough drugs to share with friends, who would pitch in to pay for it. In 2011, federal prosecutors in Connecticut secured a grand jury indictment against Efrain Vega as part of a multi-defendant cocaine distribution conspiracy. The indictment charged Vega with conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute 5 kilograms or more of cocaine and with possession with intent to distribute cocaine. He faced a statutory minimum sentence of 10 years. The prosecutors permitted him to plead guilty to conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute cocaine and agreed that the reasonably foreseeable quantity involved in the conspiracy for which Vega should be held responsible was at least 50 grams but less than 100 grams of cocaine. With the reduced quantity, Vega was no longer subject to a mandatory minimum sentence. Under the sentencing guidelines, with three points off for acceptance of responsibility, his sentencing range would be 12 to 18 months. On its face, this might have seemed like a good plea agreement for Vega. But at the sentencing hearing, Federal Judge Stefan Underhill questioned whether Vega was part of a conspiracy at all. As the judge read the facts, the only evidence the government had to prove conspiracy to distribute was that Vega talked to the dealer on the phone, was arrested after purchasing 35 grams from him, and after he was arrested, asked the dealer for help getting a lawyer. The government subsequently agreed to let Vega plead to possession with intent to distribute an unspecified quantity, but argued he should receive the guidelines sentence. [103] The government’s arguments did not persuade the judge that Vega’s conduct established membership in a conspiracy and warranted prison time. He sentenced Vega to 36 months’ probation. [104] |

III: Upping the Ante: Mandatory Penalties for Prior Convictions and Gun Possession

The sentencing power of prosecutors in drug cases is further strengthened by laws that permit them to seek increased sentences for drug defendants with prior criminal records or who possessed or used guns in connection with their drug offenses. Prosecutors have complete discretion whether or not to seek these additional penalties against defendants eligible for them. Our research indicates that prosecutors use the threat of these sentencing enhancements to obtain pleas and will carry through on those threats for defendants who do not plead.

Increased Sentences for Offenders with Prior Records

We would only invoke the §851 [prior felony enhancement] when a defendant was going to trial. It’s built into the DNA of prosecutors, even well-meaning prosecutors do it. [We] penalize a defendant for the audacity of going to trial.[105]

— Former assistant US attorney, New York, March 21, 2013

Drug offenders with prior convictions for felony drug offenses are eligible for increased mandatory minimum and maximum terms of imprisonment.[106] Judges must impose the recidivist enhancement if the prosecutor files a document known as a prior felony information under 21 U.S.C. §851 (often called an §851 information) that states the government’s intent to obtain a sentencing enhancement and lists prior qualifying convictions.[107]

If the prosecutor lists one prior drug conviction in the §851 information, the defendant’s otherwise applicable mandatory minimum sentence is doubled. If the prosecutor lists two or more prior convictions, the sentence is doubled for defendants charged with offenses carrying five-year mandatory minimum sentences, but for defendants facing ten year mandatory minimum that sentence is increased to life. Because there is no parole in the federal system, a life sentence means the defendant will die behind bars.

The provision was intended originally to ensure that truly hardened, professional drug traffickers with long records received sufficient punishment.[108] Nevertheless, Congress did not require the prior crimes triggering a prior felony enhancement to be particularly serious. State or federal drug convictions punishable by more than one year of imprisonment trigger the enhancement, even if the underlying offense would not qualify as a federal felony and even if the defendant served less than a year or no time at all.[109] Federal prosecutors recently sought a mandatory life sentence via an §851 information for a drug offender in Alabama using, as one of the two predicate offenses, his conviction under state law for possessing marijuana for personal use.[110]

There is also no statutory time bar on the prior convictions that can be used for the mandatory enhancement. The government sought an §851 enhancement for Lawrence Berry, Jr. (who was convicted of cocaine trafficking after a jury trial) based on a marijuana selling conviction that was more than 25 years old. [111] Terence L. Watson, 30, pled guilty in 2011 to being part of a conspiracy to distribute 5 kilograms or more of cocaine.[112] He faced a mandatory minimum sentence of 10 years, but the government filed an §851 notice that Watson had previously been convicted of two prior drug offenses under Florida law. Both convictions were for crimes Watson committed as a young man: one in 2000 for possessing cocaine, and the other in 2002 for distributing marijuana. He served a total of 11 months for both. As a result of the prosecutor’s decision to file the §851 information, Watson was sentenced to life without parole.[113]

Juan Gonzalez[114]In 2010, Juan Gonzalez (pseudonym) was indicted in Pennsylvania on federal charges for conspiracy to distribute and distribution of heroin and cocaine. The minimum sentence on the drug charges was 10 years. Gonzalez was also charged with possession of a gun in furtherance of his drug distribution. Gonzalez bought drugs from his suppliers and in turn sold them to street-level dealers. According to Gonzalez’s attorney, his mother was a drug addict, he stopped school in eighth grade, he can neither read nor write, and he lived on the street for many years. He has an overall IQ score of 61 and a diagnosis of mild mental retardation/intellectual disability. He had no record of violence and while there was a gun in his apartment, there was no evidence he ever carried or used it. Gonzalez had two prior drug convictions from New York: the first, in 1990, when Gonzalez was 19, for which he received probation and another, in 1994, when he was 23. [115] The prosecutor offered a plea under which he would file an information for only one of those convictions, which would double Gonzalez’s sentence on the drug charges from 10 to 20 years. If he refused to plead, the prosecutor said he would file an information listing both prior convictions, which would result in a life sentence if Gonzalez were convicted. Gonzalez nonetheless refused to plead and the prosecutor made good on his threat. [116] After a jury trial, Gonzalez was convicted on the drug and gun charges. Before sentencing, which was scheduled for September 2014, his lawyer ordered a psychologist's report, a copy of which went to the prosecutor. In August 2013, Attorney General Eric Holder issued a memorandum to prosecutors which directed prosecutors to limit filing §851 informations to cases in which severe sanctions were warranted. [117] Shortly before sentencing, the prosecutor filed an amended §851 information, which listed only one prior conviction, reducing Gonzalez’s mandatory minimum drug sentence from life to 20 years. On September 4, 2013, Gonzalez was sentenced to 25 years in prison, 20 for the drugs and a consecutive five years for possessing the gun. |

The legislation authorizing enhanced penalties based on prior convictions does not require prosecutors to consider whether a doubled or life sentence is proportionate to the individual offender’s conduct and criminal record or whether it is necessary to satisfy the purpose of punishment.[118] Prosecutors do not have to explain to the court (much less the defendant or the public) why they sought the enhancements.

Sentencing Commission data analyzed for this report shows marked differences among federal districts in the rate at which §851 enhancements were applied to eligible defendants—from a high of 87 percent in the Northern District of Florida to 1.5 percent in the Southern District of California and the Northern District of Texas; there were also seven districts where the enhancement was not applied to any of the eligible offenders.[119] There were significant variations in application rates within circuits, between neighboring districts and within states.[120]

Judge Mark Bennett has described the “stunningly arbitrary” use of §851 enhancements as the “shocking, dirty little secret of federal sentencing.”[121] Like a “Wheel of Misfortune,” he said, the application of §851 enhancements means that similarly-situated defendants in the same district, same circuit, and nationwide can receive dramatically different sentences solely based on a prosecutor’s decision to seek an enhancement.[122]

Tyquan Midyett[123]Tyquan Midyett sold crack in a housing project in Brooklyn. His life had been similar to many who end up as drug offenders in New York City: he grew up poor and remained poor; lived in a housing project; had spent two years in foster care when he was 13, after his parents separated, and then returned to live with his mother, left school in eleventh grade, and had a long history of substance abuse himself. He worked sporadically as a laborer. Midyett was 26 when arrested in 2007 after selling crack to an undercover police officer. He was indicted with others for conspiring to distribute and possession with the intent to distribute 50 grams or more of crack, a charge which under the still extant crack cocaine sentence laws carried a mandatory minimum term of 10-years imprisonment and a maximum of life. According to government evidence, Midyett was part of group that sold crack at different buildings in a public housing complex; the total amount sold during the conspiracy period was approximately 843 grams of crack. The judge found that Midyett could have foreseen and/or participated personally in the sale of 97 grams of crack. Before trial, the government offered Midyett a 10-year plea, which he refused. [124] To pressure Midyett to accept the plea, the prosecutor said he would file a prior felony §851 information that would double his sentence to 20 years because Midyett had a prior felony drug conviction. [125] That conviction was in 2001 for “criminal possession of a controlled substance in the third degree,” a class B felony under New York law. Midyett nonetheless persisted in going to trial. The government made good on its threat to file the §851 information, and Midyett was convicted and sentenced to 20 years. [126] At sentencing, Judge Kiyo Matsumoto said she thought 20 years was “quite more than necessary, but I do not have discretion under the law to consider a lesser sentence.” [127] |

Brian Moreland[128]In July 2004, Brian Moreland sold 5.93 grams of crack to a West Virginia undercover police officer for $450. When he was arrested, the police found an additional 1.92 grams of crack on him. He was convicted at trial on December 7, 2004, of distributing 5 grams or more of crack, which at the time carried a statutory penalty of a least 5 and not more than 40 years in prison, and of possessing with intent to distribute 1.92 grams of crack, which carried no mandatory minimum but a maximum penalty of 20 years. At the time of sentencing, Moreland was 31 years old. The government chose to file an §851 based on two prior state drug convictions: one in 1992, for delivering a marijuana cigarette to an inmate in prison for which he was sentenced to 60 days in custody and 60 months of probation and the other, in 1996, for possessing 6.92 grams of crack, for which he received a suspended sentence of incarceration and was placed on lifetime probation. Because of the two priors, Moreland’s mandatory minimum sentence was raised from 5 to 10 years and his maximum sentence was raised to life. Without the §851 information, Moreland already faced a high sentencing range of 262 to 327 months (21 to 27 years) because his criminal record qualified him as a “career offender” under the guidelines. But because of the §851 information, Moreland’s sentencing range increased to 30 years to life in prison. When the court sentenced Moreland to 120 months, the government appealed, arguing the sentence was “unreasonably lenient” for a person who qualified as a career offender. [129] The Fourth Circuit remanded for resentencing, directing the district court to impose a sentence of at least 20 years. [130] But before resentencing, the Supreme Court issued additional post-Booker decisions clarifying the ability of district courts to vary substantially from the guidelines and the scope of appellate review of their sentencing decisions. [131] At the resentencing, the government argued that the 20-year minimum should be imposed, but the district court again sentenced Moreland to 10 years, taking into account characteristics of the defendant (broken home, graduated from high school, took college courses); circumstances of the offense (small amounts of drugs and no violence or firearms in his history); and the purposes of sentencing. The court also did not believe Moreland was the sort of repeat drug trafficker or violent offender the career offender guideline was intended to target. [132] It pointed out that Moreland’s prior offenses were over a decade ago, that they involved small, user amounts of drugs—as the court put it, the “amount of drugs involved in [his] entire criminal history would rattle around in a matchbox”—and lacked “temporal proximity to either each other or the present offense,” and hardly constituted the “type and pattern of offenses that would indicate that Moreland has made a career out of drug trafficking” such as to “justify disposal to prison for a period of 30 years to life.” [133] |

Lori Ann Newhouse[134]On April 26, 2012, Lori Ann Newhouse, 33, pled guilty to manufacturing five grams or more of pure methamphetamine. Newhouse was a small time “pill smurfer,” i.e., she purchased legal cold remedies containing pseudoephedrine for small meth cooks and she received home-made methamphetamine in exchange to feed her long-standing addiction. Her actual conduct involved at least 20 but less than 35 grams. Newhouse was brought up in tough circumstances, including parents with mental health issues, and began a life long struggle with drug addiction in her teens. She was the single mother of three children, two of whom were living with her until her arrest. Based on the quantity of drugs to which she pled, Newhouse was subject to a mandatory minimum sentence of five years, which was doubled to 10 years (and the statutory maximum increased from forty years to life) because the prosecution chose to file an §851 information seeking a mandatory sentencing enhancement based on two prior drug convictions for possessing with intent to distribute small amounts of drugs a decade earlier (for which she was sentenced to probation). [135] Under the guidelines, because of her prior offenses, she was considered a “career offender,” with a staggering 262- to 327-month sentencing range. Newhouse was sentenced by Federal District Judge Mark Bennett, who concluded that anything longer than the 120-month mandatory minimum sentence would be “grossly disproportionate to her role and culpability.... [The 120 month sentence] is sufficient in length to reflect the seriousness of the offense, promote respect for the law, provide just punishment, protect the public and reflect the factors embodied in 3553(a)(2).” The government subsequently filed a substantial assistance motion for Newhouse, recommending a 20 percent reduction in her sentence, which enabled the judge to sentence her below the 10-year mandatory minimum. Judge Bennett sentenced Newhouse to 96 months (8 years) which, he noted, “is still exceptionally long, ‘[e]xcept, perhaps, to judges numbed by frequent encounters with the results of the sentencing Guidelines.’” |

Prior Felony Enhancements as a Plea Bargaining Bludgeon

In a recent lengthy opinion, Judge John Gleeson described the way that prosecutors use prior felony sentencing enhancements to coerce defendants into pleading.[136] The willingness of a defendant to plead, he said, is the single most important factor—and an illegitimate one at that—determining whether the government seeks the sentencing enhancement.[137]

The pressure on defendants facing the threat of prior felony sentencing enhancements is enormous. Judge Paul Friedman told Human Rights Watch about three defendants in a current drug case who all faced 10-year mandatory minimums, “except if they go to trial the prosecutor will file §851 enhancements.” One defendant faced a 20-year sentence and the other two, life. All were to be offered pleas of substantially less. “This is a typical situation,” he said. “Huge risks for defendants if they roll the dice and go to trial” rather than pleading guilty.[138]

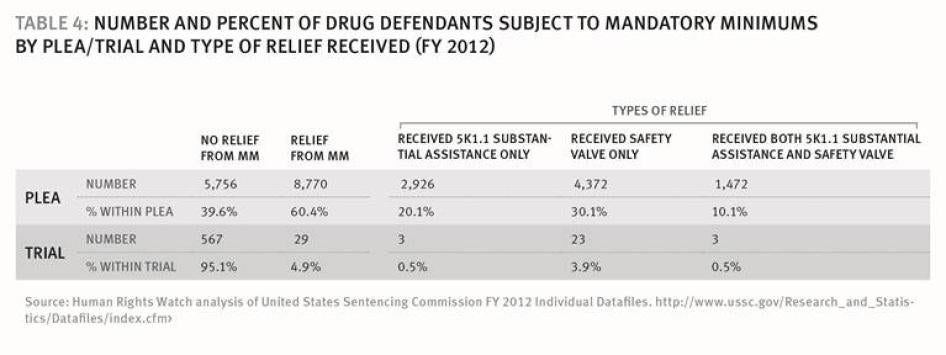

Sentencing Commission data supports Gleeson’s contention that prosecutors condition their use of §851 informations on whether the defendant pleads guilty to coerce pleas and punish defendants who nonetheless go to trial. From a sample of 5,858 cases of drug defendants who were eligible for the enhancement based on prior convictions, those who went to trial were 8.4 times more likely to receive the §851 enhancement than those who pled.[139]

According to our analysis, as shown in Figure 5, only 23.6 percent of eligible defendants who pled guilty had an §851 enhancement. In contrast, 72.2 percent of eligible defendants who went to trial received an §851 enhancement—persuasive evidence that prosecutors withhold pursuing the enhancement if the defendant will plead.[140]

Our interviews, as well as numerous cases, reveal how prosecutors use the threat of prior felony enhancements to coerce drug defendants to plead guilty and to punish those who do not.[141]

A former prosecutor told us that in his district they would only seek prior conviction enhancements if a defendant refused to plead.[142] Similarly, in the Southern District of New York, “absent unusual circumstances we would not file prior felony information if the defendant is willing to plead. But we would charge if we went to trial.”[143]

A federal public defender in Oregon said §851s are typically not in the indictment. “It’s in reserve, to be used as part of a plea negotiation.”[144] A defense attorney in southern Iowa said the US District Attorney there does not like §851 enhancements and rarely files them, even if the defendant will not plead.[145] The US Attorney for the Middle District of Florida said his office considers the nature and date of prior convictions before filing the §851, but will only withdraw it once charged if the defendant pleads and cooperates.[146] A current California federal prosecutor told us his office policy is to seek an enhancement when the indictment is filed and it is part of plea negotiations. “If I think the §851 is too much, I can seek permission not to file the information or to withdraw it,” he said.[147]

In the case of Jumal George Jones, from Chicago, the government obtained a three count indictment charging Jones with possession with intent to distribute 50 grams or more of crack cocaine, with being a felon in possession of a firearm, and with possession of a firearm in furtherance of a drug trafficking crime in violation of §924(c).