"There Will Be No Trial"

Police Killings of Detainees and the Imposition of Collective Punishments

Summary

Officers of the Rwanda National Police (RNP) shot and killed at least 20 detainees in 10 separate incidents in the six months from November 2006 to May 2007. Many of these killings appear to have been extrajudicial executions, crimes that violate both international human rights law and Rwandan law.

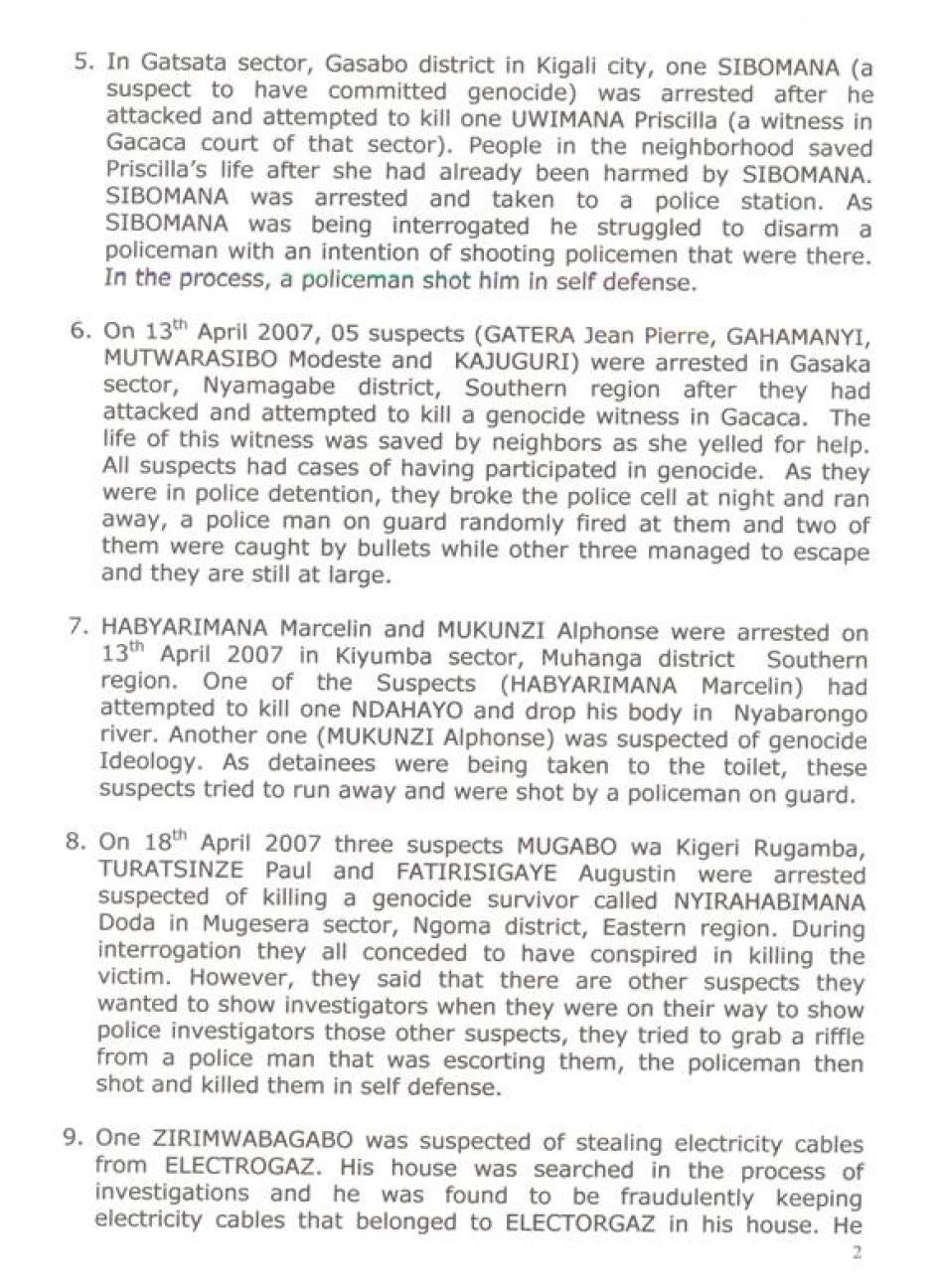

The police acknowledge the deaths of the 20 detainees in a statement sent to Human Rights Watch by Commissioner General of Rwanda National Police Andrew Rwigamba but say all were shot in escape attempts or attempts to take weapons from police officers. They say the deaths are being investigated.

Although detainees were killed in official custody in earlier incidents, the number of such deaths increased significantly beginning in late 2006 following several highly publicized killings of survivors of the 1994 genocide and others involved in the gacaca jurisdictions, a popular justice initiative meant to prosecute those accused of genocide.

Faced with demands for increased protection of such vulnerable persons, officials responded by establishing a policy of collective responsibility making all Rwandans responsible for the security of their fellow citizens. The meaning of the policy was not precisely spelled out, nor was it enacted in law, but officials ordered increased night patrols by citizens. They also warned repeatedly that anyone who harmed or tried to harm survivors would face severe if unspecified punishment.

The congruence between these official pronouncements and the increase in the number of deaths in police custody raises concern that some police officers may have interpreted official exhortations as a license to abuse detainees, particularly but not exclusively those accused of crimes against survivors or persons involved in the gacaca process.

Cases of police killings have occurred in several parts of Rwanda but those documented thus far have been concentrated in the south and east, regions known for the severity of the genocide and continuing tensions surrounding gacaca. The police statement did not condemn the killings of the 20 detainees but rather noted that most of the victims were "of extreme criminal character ready to die for their genocide ideology," implying that accusations against the detainees untested in court in some way justified their killing.

In some cases both before and since late 2006, police officers also killed detainees accused of crimes unrelated to the genocide and the gacaca process, including persons accused of murder, rape, and theft. According to the police statement and Human Rights Watch research, such killings have also increased since 2006. The police acknowledge that detainees not suspected of genocide or crimes related to gacaca were killed, but offer no explanation other than that the victims were trying to escape.

Several donor governments, including the United States and the United Kingdom, have asked police officials for explanations of the killings. The Rwanda National Police has promised investigations, but without giving assurance that they will be carried out by independent and impartial investigators.

In a number of communities, local authorities interpreted the national policy of collective responsibility as permitting or even requiring collective punishment whenever survivors or participants in gacaca were troubled or attacked. Assisted by police officers and members of the Local Defence Force, administrators imposed fines or even beatings on citizens who had not been tried but were held responsible for alleged offenses because they had the misfortune to live near the scene of the crime.

The imposition of collective punishments violates the presumption of innocence and the right of accused persons to a fair trial, rights guaranteed both by international human rights law and by the Rwandan constitution.

As Rwandan officials strive to demonstrate a commitment to the rule of law, they must ensure that abusive police killings of detainees be halted immediately; that thorough, impartial investigations be carried out; and that those responsible for these crimes be held accountable. They must also honor the presumption of innocence and ensure fair trials to accused persons rather than punishing those who have not been convicted in a court of law.

Recommendations

To the Government of Rwanda

- Order officers of the Rwanda National Police and other law enforcement agencies, such as the Local Defence Force, to protect the lives of all persons in Rwanda. Ensure that officers have been trained in and adhere to international human rights law and the Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials. The internationally accepted Basic Principles require law enforcement officials to use their firearms only when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.

- In accord with international legal obligations, carry out prompt, independent, and impartial investigations into all deaths of persons in custody, including those named in this report. Prosecute all police officers against whom there is credible evidence of having ordered or implemented extrajudicial executions.Ensure that such trials be conducted according to internationally accepted fair trial standards.

- Investigate fully and bring promptly to justice those responsible for attacks or threats of attacks on survivors and other participants in the gacaca process.

- Ensure that all police officers, members of the judiciary, and administrative officials afford all Rwandans the presumption of innocence.

- Ensure that Rwandans not be punished for any crime unless found guilty of that crime before a legally constituted, independent, and impartial tribunal.

- Adopt and implement a law to protect witnesses and judicial personnel engaged in all judicial proceedings.

To International donors

- Use your influence to persuade the Rwandan government to protect the lives of all persons within its territory and to investigate and bring to justice all persons, including police officers, responsible for unlawful killings or assault. Stress the importance of effective and transparent investigation of deaths in police custody.

- Governments providing assistance or training to the Rwanda National Police should particularly insist that police officers adhere to international human rights standards, including the right to life, the presumption of innocence, and the right to a fair trial.

- Assist the Rwandan government in finding more effective ways to protect survivors and participants in the gacaca process.

Attacks on Genocide Survivors and Gacaca Participants

In an atmosphere of growing public concern about harassment and attacks on survivors of the 1994 genocide, Human Rights Watch published a report in January 2007 documenting the killing in East Region of one survivor and a subsequent reprisal killing of eight persons who lived in the community where the murder was committed. In another case, the report documented the killing of a judge in a gacaca jurisdiction-a people's court set up to try crimes of genocide-and the killing the next day by police officers of three suspects detained on suspicion of involvement in the judge's killing. Citing these 13 killings, as well as the concerns being voiced by survivors and authorities, Human Rights Watch cautioned that ethnically based tensions continued to trouble some parts of Rwanda.[1]

In mid-2006 the government established an office of witness protection that had registered 26 complaints by late in the year.[2]There is no general law on witness protection, although the law on gacaca jurisdictions provides up to one year in prison for persons who harm witnesses and judges involved in the gacaca process.[3]

Passage of a law to protect witnesses, recently requested by a commission of the Rwandan Senate,[4] would make it easier for police and judicial authorities to assure the security of witnesses, thus contributing to the legitimacy of judicial proceedings.

In late December 2006 participants in the national dialogue-an annual meeting of leading Rwandans-discussed at length the issue of preventing and punishing threats, harassment, and attacks against survivors and participants in the gacaca jurisdictions. Since that time authorities including President Paul Kagame, military commanders, and local administrators, have told the public that strong new measures had been adopted to deter and punish such conduct.[5]

Arguing that people residing nearby would necessarily know of any plan to attack a survivor, officials insisted repeatedly that all Rwandans would be held responsible for the security of their neighbors. In most communities local officials created new night patrols or increased the number of existing patrols, particularly in the vicinity of homes of persons thought to be at risk.[6] Local residents were responsible for doing the patrols, an unpaid community obligation. In some areas, officials also increased surveillance of persons thought likely to engage in attacks on survivors. In addition, officials warned that there would be sanctions against any who troubled survivors; the sanctions were left undefined, although in April Finance Minister James Musoni said there "would be no mercy" for those caught troubling survivors.[7]

Survivors, particularly representatives of the association Ibuka, continued to express concern about the security of survivors and authorities continued to issue warnings during the first six months of 2007. In a late May meeting, an Ibuka representative said that six survivors had been killed in April, often a month of violence because of its associations with the 1994 genocide, but he did not list other deaths for the year.At the same meeting, the executive secretary of the human rights organization, Rwandan League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LIPRODHOR), reported three killings that appear to have been related to ethnic tensions.[8] Press accounts spoke of two deaths of survivors, one probably related to land disputes rather than the genocide as such, and an attack on a child, reportedly wounded because his father was a witness in gacaca trials.[9] In 2006 survivors' organizations reported numbers ranging from 12 to 20 killings of survivors,[10] so these accumulated reports suggest that the numbers for 2007 have not increased and may have decreased somewhat. Indeed, Tharcisse Karugarama, minister of justice, and Domitilla Mukantaganzwa, executive secretary of the National Service of Gacaca Jurisdictions, both expressed the opinion that attacks on survivors had diminished during the first quarter of 2007.[11]

Police Killings of Detainees

Human Rights Watch researchers investigated reports of suspicious deaths of detainees in a wide range of locations from April 2006 through May 2007. Most of those killings took place in the six months between November 2006 and May 2007. Details of 26 deaths (and of three men who have not been seen since police reported they had escaped) are given in the table below. Many appear to have been extrajudicial executions.

Human Rights Watch has received reports of other killings in police custody that have not yet been confirmed. These include incidents in Nyanza town, Nyanza district; Gasabo district, KigaliCity; Nyarugenge sector, KigaliCity; Kibangu sector and Kibilizei sector, Muhanga district; and Shyrongi district, North Region. Some of these incidents have attracted little attention, in part because witnesses fear sanctions if they speak openly about them. On a number of occasions, witnesses afraid for their security have refused to speak with researchers from Human Rights Watch or other organizations and on one occasion a person who did meet with a Human Rights Watch researcher was subjected to interrogation following the meeting.

Of the 26 deaths detailed in the table below, 14 are of persons accused of attacks on genocide survivors and others involved in the gacaca process; nine involve persons charged with murder, rape or theft; and three involve persons detained for unknown reasons.

Detainees Accused of Attacks on Survivors or Gacaca Participants

This section reports the deaths of five men in two incidents in January 2007 and of two others killed in April 2007. In each case, the police claim the men were shot while trying to escape.

Killings in Ngamba Sector, Kamonyi District, South Region

Landuardi Bayijire, president of the gacaca jurisdiction of Ngamba sector, Kamonyi district, was killed in the early hours of December 28, 2007. According to a news report, Bayijire, who was also the local president of Ibuka, was killed in his home with a knife and a blunt instrument. He was sleeping alone in a house located close to his fields, while other members of the family stayed in his other residence on a nearby hill.[12]

Coming in the wake of other attacks on survivors and persons involved in the gacaca process,many assumed that his death was connected to his being a survivor and to his role in the gacaca court. According to local residents, more than one gacaca suspect had remarked about Bayijire's severity as a judge, saying that if he had not been part of the panel of judges, they would have an easier time in front of the court. Other residents of the community, however, told a Human Rights Watch researcher that Bayijire had been engaged in a land dispute with one of his sons, Theoneste Niyomugabo, and had quarreled angrily with him the day before the killing. Some local residents said that his son, anxious to get land in order to get married, had previously threatened to kill him.[13]

On December 29 members of the Local Defence Force, a government paramilitary organization, arrested several men, including Daniel Uwimana, Polycarpe Munyangoga, Alphonse Kagambirwa, and Silvre Kagenza.[14] At the time of the arrest, one of the men reportedly asked why he was being taken away since he had always complied with orders to attend gacaca meetings and do the unpaid public labor known as umuganda.[15] Four others were also arrested, Clestin Munyaneza, Cyriaque Uyisabo, Nkinamubanzi, and an unidentified man who was accused of attacking a gacaca official, not of having killed Bayijire.[16]

The mayors of Kamonyi and Muhanga districts, as well as the president of Ibuka at the national level, attended Bayijire's burial, which was marked by a heavy downpour of rain. Officials told those present that they could not seek shelter, as would usually be done, but must stand, hatless in the rain. After the burial, officials directed people to sit on the wet ground and, according to one person present, said that they would sit there "for the next three days" unless they provided information on Bayijire's killing.[17] Although people were kept sitting at the gravesite for some time, this effort by officials apparently neither elicited information, nor did a search of the homes of the suspects on December 30.[18]

At a public meeting at Ngamba parish on December 30, a policeman identified by witnesses as the Chief of Police for Kamonyi district told residents that it was important for them to provide information about the crime, given that police officers had not yet found the evidence necessary to build a case against the detained persons.[19] In an interview published on January 2, 2007 in The New Times, a newspaper close to the government, Jean-Paul Munyandamutsa, mayor of Kamonyi district, said that the suspects had not confessed or given any relevant information on the death of Bayijire.[20]

The suspects were first detained at Kamonyi district lock-up where family members visited at least one of the suspects several times between December 30 and January 2. He asked that a clean set of clothes be brought because he had been told he and the others would be taken to Musambira police station for interrogation. When visitors arrived at Kamonyi on January 3, a police officer told them that Uwimana, along with the unidentified man, had been shot as they attempted to flee.[21]

Some detainees, including Polycarpe Munyangoga, Alphonse Kagambirwa, and Silvre Kazenga, were transferred to Musambira, where several, including Kagenza, were badly beaten. Those injured asked visitors to bring medication. As the week wore on, the detainees apparently lost hope. One told visitors, "Don't bother bringing any more food. There will be no trial."[22]

On January 10, some of the detainees held at Musambira were transferred to Gitarama central prison, but those involved in the Bayijire case were kept in the lock-up. Because family members and friends believed that the men had been transferred to Gitarama prison, at first they did not come to visit. After learning the men were still at Musambira, they brought food on January 13. When visitors returned on January 14, they found police officers loading the bodies of Munyangoga,Kagambirwa, andKagenza into police vehicles. Police officers drove the bodies to the vicinity of their homes and called local people to carry the bodies to the houses.[23] One local man told Human Rights Watch researchers that a policeman said, "Get those bodies out and look at the consequences of what you have done".[24]

Police officers gave families no notification of the deaths of these men before delivering the bodies. One officer told family members that the three men had been killed trying to attack police officers when they were being taken to the toilet. Members of the Local Defence Force present at the Musambira lock-up told local residents that police officers had executed the three.[25] According to those who saw the bodies, one had a single bullet wound at the temple, another had a wound in the back of the neck, while the third had wounds in the head and the stomach.[26]

Killings in Gasaka Sector, Nyamagabe District, Southern Region

On April 10 2007 in Ngiryi umudugudu, or village, Gasaka sector, assailants entered the home of a witness who testified frequently in gacaca sessions and beat both the witness and the witness' mother. The mother was so severely injured that she required hospitalization for a week.[27]

On April 12, police officers arrested at least five men who had participated in the local night patrol on that date, including Jean Gatera, executive secretary of the umudugudu, Gahamanyi, Joseph Nkurikiyimana, Modeste, and Emmanuel Nshimiyimana, also known as "Kajyunguri."[28] At the time of the arrests, police officers beat several people who were not detained, including Gatera's wife, Violette Uwimbabazi, using heavy sticks.

Police officers detained the men at Nyamagabe police station and on April 13 refused to allow visitors to see them. When visitors returned the following day, a police officer told them that Jean Gatera and Gahamanyi had been shot while trying to escape. According to a local source of information, both had been shot in the back of the neck.[29] Police officers said that three others, Joseph Nkurikiyimana, Emmanuel Nshimiyimana, and Modeste, had escaped. These three men have not been seen or heard from since and family members believe that they are dead.[30]

Detainees Accused of Other Crimes

The rapid increase in numbers of detainees shot by police between November 2006 and May 2007 coincides with a period of heightened concern and rhetoric about attacks on genocide survivors and others involved in the gacaca process. But both before and during the period of increase, police officers have shot and killed detainees in cases when they were suspected of involvement in serious crimes unrelated to the genocide or to the gacaca process. Several cases are described below. These also appear to have been extrajudicial executions, underlining that there is a general problem of deaths in police custody.

Killings in Kibungo Sector, Ngoma District

Police officers arrested three men, Alphonse Nshikili, Telesphore Karemera and Emmanuel Mfitimfura, at about on April 4, 2006. They found the men in a small bar in the Cyasemakamba area of Kibungo town, EasternProvince and arrested them on suspicion of armed robbery. They arrested another unidentified man shortly after.[31]

The police, along with the detainees, went to search the house of Nshikili where they found a television set and a large bag. Police officers said the television set had been stolen and later told others in the community that the bag had contained a Kalashnikov automatic rifle.[32]

According to residents of the Kabare area of Kibungo town, they heard a vehicle stopping nearby, followed by gunfire, several individual shots and then a burst of successive shots, at about 8 p.m.[33] Several who went to see what happened found two bodies, lying about 10m apart from each other, in pools of blood, one withtissue, apparently from his brain, near his head. Nearby were four uniformed police officers, at least two of whom were armed with Kalashnikov rifles. They told the onlookers that the dead men were robbers who had tried to escape while en route to show the police where other members of their group were living. They added that a third suspect had managed to get away.[34]

One local resident told Human Rights Watch researchers that the police officers had brought Nshikili, Karemera, and an unidentified third man to Kabare because Nshikili had told the police that a resident of Kabare had given him the gun supposedly found at his home.[35]

Witnesses who saw Nshikili's body claim that his thumb had been amputated and that there was a knife wound in his chest and a gunshot wound in his neck. A relative of Nshikili, skeptical of the official version of his death, exclaimed to Human Rights Watch researchers, "If someone is running away, how can you cut off his thumb?"[36] Members of Nshikili's family say that police officers were reluctant to release the body and that when they arrived at the Kibungo GeneralHospital to claim the body, workers were preparing to bury the body without the family's knowledge. Relatives state that police also objected to them gaining access to an official autopsy report.[37]

On the day when Nshikili was buried, a family member remembers that police officers warned local people not to talk about his death. "If you do talk, they say that you are an accomplice of those 'thieves,'" said Nshikili's relative.[38]

According to local residents, they were surprised that Nshikili, the son of a genocide survivor, had been arrested since he was not known to have been involved in any previous criminal activity. Emmanuel Mfitimfura, arrested at the same time as Nshikili and Karemera, was released after spending a week in the lock-up at Kibungo police station.[39]

Nshikili's family members have engaged a lawyer and have written to both the commissioner general of police and to the prosecutor general of Rwanda, requesting an investigation of his death, with no result at the time this report was written.

In May 2007, the gacaca judges of Karenge cell took the extraordinary step of summoning a policeman named Gakwisi to explain the deaths.[40] Under law, gacaca jurisdictions are authorized to inquire into genocidal crimes during the period 1990-1994, but have no mandate to deal with more recent crimes. Nonetheless the police officer attended the gacaca session and reportedly told the court that the two men had offered to show the police where other thieves were hiding, but en route they had jumped out of the police pick-up truck and were shot trying to escape. According to persons present at the hearing, the police officer was asked how Nshikili could have been shot in the throat while running away. The police officer replied, "That depends on the skill of the shooter".[41]

According to local residents, the area continues to be troubled by armed robberies.

The killing of Emmanuel Ndahiriwe, Kicukiro Sector, Kigali

On the morning of Friday, April 20, 2007, police officers and members of the Criminal Investigations Department of the National Police (CID) arrested Emmanuel Ndahiriwe at his workplace, Electrogaz (the state energy, gas and water utility). Members of Electrogaz's internal investigations unit accompanied the investigating officers. According to the police, Ndahiriwe was one of a number of Electrogaz employees and others arrested in an investigation of theft of Electrogaz equipment.[42]

He was taken in an Electrogaz vehicle, first to Remera police station and later to Kicukiro police station, both in the city of Kigali. That evening a family member visited him and left the Kicukiro police station at about [43]

The next day, April 21, 2007, persons wanting to visit Ndahiriwe were told by police officers at the Kicukiro station that he had been taken away by CID officers for questioning. In the evening, members of Ndahiriwe's family sought him at CID headquarters but were told that officers in charge of the file were absent. Friends and relatives hoped that they would be able to locate him on Monday, April 23. By that time Ndahiriwe would have been detained more than 72 hours and under Rwandan law a detained person must appear before a magistrate within 72 hours of his arrest. But on Monday the police officers told them nothing.[44]

At on Tuesday morning, Radio Rwanda broadcast descriptions of bodies that had been delivered to the morgue at KigaliCentralHospital, a regular feature of early morning broadcasts. Relatives listening to the announcement recognized one description as fitting that of Ndahiriwe. When they went to the morgue, they were able to identify his body. They were told that his body had been delivered by a Toyota "Hi-Lux" vehicle belonging to Electrogaz on Friday April 20, at about Other witnesses saw an Electrogaz vehicle with blood in it. The vehicle in question, used by the internal investigations unit, bore the registration plaque numbered GR 779A.[45] According to persons who viewed the body, Ndahiriwe had been stabbed in the chest and shot in the head.[46]

In a press conference broadcast on national radio, Chief Superintendent Costa Habyara, Director of the CID, stated that Emmanuel Ndahiriwe had been killed by police officers in self-defense, as he tried to grab a weapon. According to Habyara, the death occurred outside of the police station as the detainee was on his way to show the police where stolen equipment was stored and where criminals were hiding.[47]

Killings of Detainees arrested by Soldiers

Soldiers of the Rwandan Defence Force (RDF) do not have jurisdiction over civilians. In one case investigated by Human Rights Watch researchers, however, soldiers arrested two men on suspicion of armed robbery and then killed them.

Killings in Rwabicuma Sector, Nyanza District, South Region

In May 2006 officials established a military post in Rwabicuma sector, Nyanza district, to deal with several armed robberies in which residents had been injured. Soldiers at the military post, located at KakamushiPrimary School, Nyarusange cell, were to carry out night patrols and otherwise discourage criminal activity.[48]

According to a local resident, members of the Local Defence Force (LDF), aided by local residents, found a man named John but known as "Samunani" hiding in the bush on May 9, 2006, following a robbery in an area known as Kabirizi.[49] Samunani was taken to the Nyagisozi sector offices where, according to a witness, he was "seriously beaten" with truncheons by members of the LDF before a large crowd. Samunani named several persons whom he said participated in robberies with him and on May 10, soldiers were sent to 'arrest' them, although they had neither legal authority to do so nor any arrest warrants. In one case, they apparently persuaded the persons whom they were seeking to accompany them to the military post under the guise of having lost their way.[50]

Local residents told a Human Rights Watch researcher that the soldiers brought at least seven persons to the Nyarusange military post, five of them men: Rukara, a resident of Kigogo village, Kamabuye cell; Vincent Hakizimana; Hakizimana's brother Aminadabu; Denis Ndagijimana; and an unidentified older man, and two women,Immacule Uwimana and the wife of a man known as "Kazungu".[51] Several soldiers interrogated and allegedly threatened those who had been rounded up and later drove Vincent Hakizimana, Aminadabu, and the older man to the local lock-up in nearby Rurangazi cell.[52]

Later in the afternoon of May 10, soldiers took other suspects, including Samunani and Denis Ndagijimana, to the lock-up at the Nyagisozi sector offices. That evening, soldiers took Samunani and Ndagijimana from the lock-up, saying that they were taking them, on foot, to Nyanza town.[53] The journey, which takes about 40 minutes in a car, takes about two hours on foot. It is unclear why such a journey would be taken on foot and at nighttime, and why soldiers, rather than policemen, would take responsibility for the two detainees.

At about , local people heard gunshots and found the bodies of the two men lying in a small patch of open forest, several hundred meters from the military post. Samunani had been shot in the base of the spine and was laying face-down, while Ndagijimana had been shot in the head and the back. Soldiers and local authorities told local residents that the two men had tried to flee.[54]

One skeptical local resident questioned the explanation that the men had tried to flee. He told Human Rights Watch researchers:

The police sent a vehicle to pick up the bodies of the two who died. Why couldn't they have sent a vehicle to take them to Nyanza when they were still alive?[55]

On May 11, police officers, who had apparently taken custody of the detainees at the Rurangazi lock-up, brought them to the scene of the killings to view the bodies, which were still laying there. According to witnesses, three of the detainees had been so badly beaten that they had difficulty walking and they said they had also been threatened with death by police officers.[56] They were freed shortly after.

In an interview with Human Rights Watch researchers the executive secretary of Rwabicuma sector denied that armed robberies had occurred in the area and also denied that Samunani, Denis Ndagijimana, or anyone else had been arrested in connection with cases of theft or robbery during 2006.[57]

Partial List of Detainees Killed by Police Officers and Soldiers

April 2006-May 2007[58]

Date |

Place (Region/ District Sector/ Cell) |

Names of victims |

Crime alleged |

Explanation Given by police and/or authorities |

Other remarks |

May 8, 2007 |

South/ Nyanza/ Muyira |

Emmanuel Niringiyimana and Noel Nsabimana |

Rape ofseven year old girl. |

Police say that the two attempted to escape from their cell at night and were shot by guards. |

|

April 20, 2007 |

Kigali ville, Kicukiro |

Emmanuel Ndahiriwe |

Theft ofElectrogaz cable. |

Police provided no date or place of death but said thatNdahiriwe was arrested in conjunction with arrest of Zirimwabagabo, accused of stealing Electrogaz cable.Police say that en route to helping them find another suspect Ndahiriwe tried to grab weapon from a policeman who shot him in self defense. |

|

April 18, 2007 |

East/Mugesera/Ngoma |

Mugabo wa Kigeri Rugamba, Paul Turatsinze, and Augustin Fatirisigaye |

Murder of genocide survivor named Nyirahabimana. |

Police said allthree confessed and were killed when they grabbed weaponof a policeman en route to show police other suspects. |

|

April 13, 2007 |

South/ Nyamagabe/ Gasaka |

Jean Gatera andGahamanyi [killed April 13] Joseph Nkurikiyimana; Emmanuel Nshimiyimana alias "Kajyunguri" and Modeste[whereaboutsunknown] |

Attempted murder of genocide witness |

Police stated that they arrested genocide suspects Jean Pierre Gatera, Gahamanyi, Modeste Mutwarasibo, Kajuguri who tried to kill genocide witness. All broke out of cell in escape attempt. Police killed two (unnamed) but three escaped. |

According to local sources, a number of people, including Gatera's wife, Violette Uwimbabazi, were beaten by police. |

April 13, 2007 |

South/ Muhanga/ Kiyumba |

Marcel Habyarimana and Mukunzi. |

Habyarimana: attempted murder of Ndahayo Mukunzi : having genocide ideology. |

According to police, the suspects tried to escape while being taken to toilet and were shot by police. |

|

April 9, 2007 |

South/ Gisagara/ Mamba |

Ufitese |

Unknown |

Local human rights activists report that Ufitese was killed by security forces. |

|

April 9, 2007 |

Kigali-city/Gasabo/ Gatsata |

Sibomana |

Attempted murder of gacaca witness. |

According to police Sibomana, a genocide suspect, wounded and tried to kill a witness. After his arrest and while being interrogated, he tried to disarm a policeman, intending to kill him, and was shot in self-defense. |

|

April 1, 2007 (March 2007). |

South/ Nyaruguru/ Ngoma |

Pierre Muhizi |

Murder ofwife. |

According to police Pierre Muhizi killed his wife with axe, was arrested March 31, and was killed April 1 outside Cyahinda police station during an escape attempt. |

|

Feb 1, 2007 |

East/ Bugesera/ Ruhuha |

J. Bosco Ntawuyinoza |

Raping and killing a young woman. |

Police state that Jean-Bosco Ntawurimuzo broke out of his cell; and was killed during the escape attempt. |

|

January 2007 |

South/ Kamonyi/ Ngamba |

Daniel Uwimana and unidentified man [killed January 3] Polycarpe Munyangoga, Alphonse Kagambirwa, and Silvre Kagenza, [killed night of January 13-14] |

Murder of gacaca judge |

According to police, Uwimana was killed January 2; Munyangoga,Kagambirwa, and Kagenza were killed Jan 10 as they attempted to escape |

|

Nov 24 2006 |

East/ Rwamagana/ Mwulire |

Jean Hakizamungu, John Rukondo,and Francois Ndagijimana |

Murder of gacaca judge |

Police state that three persons were arrested Nov 22, all confessed; they tried to strangle policeman in orderto escape. Police shot in self-defense. |

|

May 2006 |

South/ Rwabicuma |

Samunani and Ndagijimana arrested by soldiers. [Killed evening May 10.] |

Armed robbery. Local people say that Immacule Uwimana, Rukara , Vincent Hakizimana and his brother "Aminadabu", Denis Ndagijimana, the wife of one "Kazungu", and an unidentified older man were arrested May 10. |

Local Authorities deny that anyone was arrested in connection with armed robberies. |

Local witnesses state that Samunani was arrested May 9 and beaten, he gave names of others and was killed. Three suspects beaten, later released. |

April 2006 |

East/ Kibungo town |

Alphonse Nshikili, Telesphore Karemera |

Armed robbery, along with Emmanuel Mfitimfura [released one week later] and an unidentified man. |

Official Responses

The Rwanda National Police state they are committed to serving the people of Rwanda and on their website announce various ways of lodging complaints about abuses by police officers.[59] In the one instance in which a complaint was made in the case of the killing of a detainee-that of Alphonse Nshikili killed in April 2006-appeals by the family of the victim to both the commissioner general of police and to the prosecutor general of Rwanda remained unanswered at the time of this writing.

Human Rights Watch, Rwandan human rights organizations, and several representatives of the diplomatic community have repeatedly pressed Rwanda National Police officers for explanations of the police killings of detainees. On June 4, 2007 Commissioner General Rwigamba sent a three-page statement to Human Rights Watch (attached as an annex to this report) listing 10 incidents between November 2006 and May 2007 in which police officers had shot and killed 20 detainees.[60]

The explanations in this statement, like that offered by Deputy Mary Gahonzire in an interview with a Human Rights Watch researcher in December 2006,[61] were all variations on a single theme: the detainees had been shot while trying to escape.

The statement said that all the police officers involved had been questioned and that investigations were underway. It also indicated that police officers needed further training in the use of firearms, better facilities in police stations (to eliminate the need to take detainees outside the building to use latrines), and more handcuffs.

All the detainees were killed within days and in some cases within hours of their arrests. In no case had trials begun, far less verdicts been reached, yet in the opening paragraph of the statement, several of the detainees are referred to as "killers," not suspects. In its final paragraph, the statement acknowledges that some of those killed by the police had no involvement with genocide but nonetheless it declares that "the suspects involved in these cases were of extreme criminal character ready to die for their genocide ideology." It concludes that these detainees were "terroristic in nature and don't care about their own lives leave alone others."[62]

Deputy Commissioner Habyara also seemed convinced that the detainees were necessarily guilty of the crimes for which they had been arrested. He told a public meeting on May 25, 2007:

However someone who rapes a baby, someone who kills a child, someone who sexually mutilates a girl, a member of the clergy who kills his colleague. . .what is he not capable of doing? Would it be surprising if he tried to grab the rifle from a police officer? These are exceptional cases. Just as these killings are exceptional, they are done by extraordinary people who could do anything at any time. . . . These are not extrajudicial executions, rather they are exceptional cases committed by exceptional criminals.[63]

The assumption that the detainees were criminals-and even exceptionally dangerous criminals-shows a regrettable disregard for the presumption of innocence. The readiness to try to shift the blame for their death on to the victims throws into question the likelihood of independent, impartial investigations.

Destruction of property belonging to survivors and collective punishments

Over the last year survivors reported scores of cases of property damage, such as the uprooting of their crops or the killing of farm animals, by persons who wished to harm them. Since the end of 2006, officials have been imposing collective punishments, including fines, obligatory labor, and beatings on residents of communities where such abuses have occurred.

In Gikombe umudugudu, Bulimba cell, Shangi sector, Nyamasheke district, for example, each local household was required to pay 1,550 FRW (US $2.80) to reimburse a survivor whose cow died in suspicious circumstances. This represented a considerable sum of money in a country where most people live on less than 550FRW (US $1) a day. [64] Those unable or unwilling to pay were detained in the cell lock-up until others paid the fine for them.[65] In Huye district, South region, the mayor forced residents to help rebuild the house of a survivor that had burned down. He said the obligatory labor, being done even before the police had finished their investigation of the crime, would help break impunity and indifference.[66]

In an interview with Human Rights Watch researchers, Domitilla Mukantaganzwa, executive secretary of the National Service of Gacaca Jurisdictions mentioned several other examples from elsewhere in Rwanda, suggesting that implementation of collective punishment is relatively widespread. Madame Mukantaganzwa spoke approvingly of the "educational" aspects of the practice, its effectiveness as punishment, and its practical usefulness in restoring the value of lost property. She said that she believed attacks on survivors had decreased since the policy was implemented.[67]

Beatings by Police officers in Huye Sector, Huye District, South Region

In at least one case, the collective punishment involved beatings of local residents as well the imposition of a fine to restore damaged property.

On February 13, 2007, some crops were uprooted from fields belonging to Josepha Mukarwego, who lives in an umudugudu called Rwezamenyo. Local residents saw the destruction of the crops as a vindictive action, probably related to Mukarwego's testimony in gacaca. During the genocide, she had lost her six children, her husband, and her mother-in-law. Mukarwego was also involved at this time in a land dispute with her sister-in-law, also a survivor. It is unclear how much importance the land dispute had, if any, in the destruction of Mukarwego's crops.[68]

The local authorities and police officers based at Huye sector, one of them named Batera, convened a meeting of residents at the site of the damaged crops. Members of the Local Defense Force (LDF) ensured that residents attend the meeting. After some discussion, participants settled on 45,000 FRW as the value of the destroyed crops, and each household was told to pay 500 RWF.[69]

As the meeting was in progress, several police officers identified by local people as based in Ngoma (formerly Butare town) arrived with two LDF members not resident in the sector. After surveying the damaged crops, the police officers ordered the men to lie down on the ground and told the LDF members who had come with them to cut stout branches from the nearby trees. According to one of the victims, a police officer rejected the first sticks brought by the LDF members, saying they were not stout enough. The LDF members beat the men on their backs and buttocks. Most people received between six and fifteen strokes, but three young men (including Antoine Mutabazenga, 21 years old, Jean-Bosco Gahamanyi, 22 years old, and Alphonse Nsabimana, 24 years old) were singled out for extra punishment. The resident elected to coordinate security in the umudugudu was told that he would be given 200 blows, which he was made to count out loud. But, according to some present at the time, he cried out after 73 blows, "I am finished, that's all I can take". The police then told him, "Take these [blows] for now, we will give you the others later."[70] The police officers from Ngoma also threatened more drastic consequences for residents if they had to come back to Sovu for any similar case in the future.

As explained by officials, all Rwandans must take responsibility for the security of their neighbors, but in this case, it was not all residents of Sovu who were punished. The two male genocide survivors were not beaten. One did not lie down and another hurriedly left the meeting. Similarly all households in the umudugudu were included on the list recording payments of the fine, but according to one knowledgeable source, the survivor families would not be asked to actually pay the fine.

Sovu residents who bitterly resented both the beating and the attendant humiliation blame police officers from the nearby town for the punishment, but some also remarked that the incident undermined their respect for the local authorities.[71] They see themselves as unjustly punished for a crime of which many-or perhaps even all-of those punished were innocent.

Those punished may extend their anger beyond officials to survivors who were the original victims of the attacks, seeing them eventually as the cause of the fines they must pay, the labor they must contribute, and the beatings they must take. Should this happen, the policy of collective punishment may actually increase the vulnerability and isolation of survivors. At least one senior official in the government recognized this risk. He told a Human Rights Watch researcher, "We must not create a victimized people. That would be disastrous for reconciliation."[72]

Violations of International and Rwandan Law

The use of lethal force against detainees is highly restricted by commonly accepted international standards put into effect by most states. The 1990 United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms emphasizes that intentional lethal use of firearms only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.[73] In the context of a detainee in police custody, such circumstances would include "self-defence or the defence of others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury" or preventing the detainee's escape when such action would "prevent the perpetration of a particularly serious crime involving grave threat to life."[74]

The evidence we have collected, including the official explanations presented by senior police officers, suggests that not all-indeed perhaps none-of the killings discussed in this report meet those criteria. Only thorough and impartial investigations, drawing on as wide a range as possible of forensic evidence and witness testimony, can determine if any or all of these killings constitute cases of extrajudicial execution. Such cases would violate the right to life guaranteed by the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), of which Rwanda is a state party, as well as the Rwandan constitution.[75]

Statements by senior police officers about these shootings violated the presumption of innocence guaranteed by the ICCPR and by the Rwandan constitution. To the extent that attitudes expressed in these statements are held generally by police officers, the shooting of detainees is unsurprising and seems likely to continue unless specific action is taken to change the attitudes and halt the killings.

The practice of collective punishment is illegal in times of peace and war alike. It is not only a serious violation of international humanitarian law,[76] but also violates human rights law by subjecting individuals to arbitrary arrest, cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment, by contravening the right to recognition as a person by the law, as well as by violating the presumption of innocence and the right of all persons to be tried in lawful and impartial tribunals for any crimes of which they are accused. These rights are guaranteed to the citizens of Rwanda by the ICCPR and by the Rwandan constitution.[77]

The Donor Community

Rwanda continues to depend heavily on donor assistance, both with general support and for specific projects. Although its government is one of those most ready to criticize donors, its leaders have often shown themselves ready to listen to counsel from international actors.

The Netherlands, apparently the first to be alerted to the problem of police shootings of detainees, raised the issue with other donor representatives. An initial discussion by the members of the European Union in April brought no action, but the ambassadors of the United States and the United Kingdom, and perhaps other diplomats, asked senior police officers for explanations of the killings. The statement sent to Human Rights Watch on June 4 or one like it was sent to at least one major donor. Donors, particularly those most directly engaged with assistance to the police (Belgium, Sweden, South Africa), should insist that the investigations promised by the national police in this statement are carried out immediately and impartially and that any officers suspected of illegal killings are prosecuted.

Conclusion

Attention to police shootings of detainees, as well as to the issue of presumption of innocence for accused persons, comes at a time when the Rwandan government is particularly eager to demonstrate its high standards in the field of justice. Some leaders are concerned with showing a level of judicial competence and impartiality that will encourage greater investments of the capital so badly needed for economic development. Others are focused on persuading judges and prosecutors elsewhere that Rwandan courts can fairly try persons accused of genocide who are resident abroad and are now being considered for extradition to Rwanda in the United Kingdom and other European countries.

The legitimacy of a judicial system is intimately connected with that of its police system. According to international standards, to which Rwanda subscribes along with many other nations, such legitimacy requires, among other things, the protection of the lives of detainees and the presumption of innocence and right to a fair trial for persons accused of any crime. If the Rwandan government is to demonstrate the quality of its courts and police, it must take clear and prompt action to ensure that police officers and other Rwandans respect these standards.

Annex One - Statement sent by Commissioner General of Rwanda National Police Andrew Rwigamba to Human Rights Watch researcher Christopher Huggins, June 4, 2007, electronic communication

[1]Human Rights Watch, Killings in Eastern Rwanda, no. 1, January 2007, http://www.hrw.org/backgrounder/africa/rwanda0107/rwanda0107web.pdf.

[2] Ibid, p. 11.

[3] Organic Law no. 16/2004 of 19/6/2004 establishing the organization, competence, and functioning of gacaca courts, article 30.

[4]Rwanda. Senate. Rwanda: Genocide Ideology and Strategies for its Eradication (Kigali, n.d., issued April 2007), p. 169.

[5] Paul Ntambara, "Kagame warns local leaders over survivors and witnesses' security," The New Times, April 15, 2007 http://www.newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1208&Itemid=1 (accessed April 15, 2007); John Bayingana, "Ibingira assures survivors of security," The New Times, April 12, 2007, http://www.newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1164&Itemid=1 (accessed April 12, 2007).

[6]Minister of Justice Tharcisse Karugarama, News (in Kinyarwanda), Radio Rwanda, January 24, 2007,

[7] John Bayingana, "75 percent of population have reconciled - James Musoni," The New Times, April 12, 2007,

http://www.newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1167&Itemid=1 (accessed April 12, 2007).

[8]Comments by Dieudonn Kayitare of Ibuka and by Jean-Baptiste Ntibagororwa, executive secretary of LIPRODHOR, at a Journe Locale d'Information, sponsored by LDGL (League for the Defense of Human Rights of the Great Lakes), on L'tat des lieux de la criminalit au Rwanda et le role des instances rwandaises charges du maintien de la scurit dans son eradication, May 25, 2007, Alpha Palace Hotel, Kigali.

[9] Daniel Sabiiti, "65 Year Old Survivor Murdered," The New Times, June 20, 2007 http://www.newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=757&Itemid=54 (accessed June 20, 2007); Anonymous, "Genocide suspects hack child,"The New Times, January 31, 2007 http://www.newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=702&Itemid=1 (accessed January 31, 2007); Stevenson Mugisha, "Seven arrested over survivor's murder," The New Times, February 18, 2007 at http://newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=172&Itemid=1 (accessed February 18, 2007);

Daniel Sabiiti, "Genocide survivors, witnesses under security threats,"The New Times, January 20, 2007 http://www.newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=460&Itemid=39 (accessed January 21, 2007).

[10]US State Department Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2005: Rwanda", March 8, 2006, http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2005/61587.htm (accessed December 19, 2006).

[11] Human Rights Watch interview with Executive Secretary of the National Service of Gacaca Jurisdictions Domitille Mukantaganzwa, Kigali, March 13, 2007; Gasheegu Muramila, "Genocide ideology is now minimal-Karugarama," The New Times, April 17, 2007, http://www.newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1218

&Itemid=1 (accessed April 17, 2007).

[12]Anonymous, "Another Gacaca Judge Murdered", The New Times, January 2, 2007.http://www.newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=56&Itemid=1 (accessed January 3, 2007).

[13]Human Rights Watch interviews with residents of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 18, 2007. In Rwanda a young couple lacking the land to support their new household finds it difficult to marry. Most Rwandans are farmers and land is scarce.

[14]"Circumstances in which Policemen shot detainees," statement sent byCommissioner General of Rwanda National Police Andrew Rwigamba to Human Rights Watch researcher Christopher Huggins, June 4, 2007, electronic communication.

[15]Human Rights Watch interviews with residents of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 18, 2007.

[16]Human Rights Watch interview with residents of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 24, 2007.

[17]Human Rights Watch interview with residents of Ngamba sector , Kigali, April 24, 2007.

[18]Human Rights Watch interview with residents of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 24. 2007.

[19]Human Rights Watch interview with residents of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 24, 2007.

[20]Anonymous, "Another Gacaca Judge Murdered", The New Times, January 2, 2007.http://www.newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=56&Itemid=1 (accessed January 3, 2007).

[21]Human Rights Watch interview with residents of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 24, 2007.

[22]Human Rights Watch interview with resident of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 24, 2007. Unlike persons incarcerated in central prisons who are fed by the government, those held in local lock-ups depend on family and friends for food.

[23]Human Rights Watch interview with residents of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 24, 2007.

[24]Human Rights Watch interview with resident of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 18, 2007.

[25]Human Rights Watch interview with residents of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 24, 2007.

[26]Human Rights Watch interviews with residents of Ngamba sector, Kigali, April 24, 2007.

[27] "Circumstances in which Policemen Shot Detainees"; Human Rights Watch interview with Rwandan human rights colleague, Kigali, April 27, 2007.

[28]"Circumstances in which Policemen Shot Detainees"; Human Rights Watch interview with Rwandan human rights colleague, Kigali, April 27, 2007.

[29]Human Rights Watch interview with resident of Gasaka sector, Kigali, April 27, 2007.

[30]"Circumstances in which Policemen Shot Detainees"; Human Rights Watch interview with resident of Gasaka sector, Kigali, April 27, 2007. The names of the three disappeared persons are not counted in the tally of those killed by police officers.

[31]Human Rights Watch interview with local resident, Kibungo town, March 26, 2007.

[32]Human Rights Watch interview with local resident, Kibungo town, March 26, 2007.

[33]Human Rights Watch interview with local resident, Kibungo town, March 26, 2007.

[34]Human Rights Watch interview with local resident, Kibungo town, March 26, 2007.

[35]Human Rights Watch interview, Kigali, April 26, 2007.

[36]Human Rights Watch interview with relative of victim, Kibungo town, March 26, 2007.

[37]Human Rights Watch interview with relatives of victim, Kibungo town, March 26, 2007.

[38]Human Rights Watch interview with relative of victim, Kibungo town, March 26, 2007.

[39]Human Rights Watch interview with local residents, Kibungo town, March 26, 2007.

[40]The gacaca system is only mandated to judge accusations of genocide crimes committed between 1990 and 1994 and has no jurisdiction over any other cases.

[41]Human Rights Watch interview with relative of victim, Kibungo town, March 26, 2007.

[42]Chief Superintendent Costa Habyara, Director of CID, News (in Kinyarwanda), Radio Rwanda, April 25, 2007, ; "Circumstances in which Policemen Shot Detainees."

[43]Human Rights Watch interview with a friend of victim, Kigali, April 26, 2007.

[44]Human Rights Watch interview with friend of victim, April 26, 2007.

[45] Human Rights Watch interview with local human rights activist, April 27, 2007.

[46]Human Rights Watch interview with friend of victim, April 26, 2007.

[47]Chief Superintendent Costa Habyara, national head of CID, News (in Kinyarwanda), Radio Rwanda, April 25, 2007, ; "Circumstances in which Policemen Shot Detainees."

[48]Human Rights Watch interview with local resident, Nyarusange cell, April 3, 2007.

[49]Human Rights Watch interview with local resident, Nyarusange cell, April 3, 2007.

[50]Human Rights Watch interview with local resident, Nyarusange cell, April 3, 2007.

[51]Human Rights Watch interviews with local residents, Nyarusange cell, April 3, 2007 and Kamabuye cell, April 28, 2007.

[52]Human Rights Watch interview with local residents, Rwabicuma sector, March 26, 2007.

[53]Human Rights Watch interview with man living near to Rwabicuma sector offices, April 3, 2007.

[54]Human Rights Watch interviews with local residents, Rwabicuma sector and Nyarusange cell, April 3, 2007.

[55]Human Rights Watch interview with local resident, Rwabicuma sector, April 3, 2007.

[56]Human Rights Watch interview with local resident, Rwabicuma sector, April 3, 2007.

[57]Human Rights Watch interview with Ephraim Kavutse, executive secretary of Nyagisozi sector, April 28, 2007.

[58]Compiled from Human Rights Watch research, "Circumstances in which Policemen shot detainees," statement sent byCommissioner General of Rwanda National Police Andrew Rwigamba to Human Rights Watch researcher Christopher Huggins, June 4, 2007, electronic communication and from information presented by Jean-Baptiste, Ntibagororwa, executive secretary of LIPRODHOR at a Journe Locale d'Information, sponsored by LDGL (League for the Defense of Human Rights of the Great Lakes), on L'tat des lieux de la criminalit au Rwanda et le role des instances rwandaises charges du maintien de la scurit dans son eradication, May 25, 2007, Alpha Palace Hotel, Kigali.

[59] Rwanda National Police website is www.police.gov.rw.

[60] "Circumstances in which Policemen Shot Detainees" annexed to this report.

[61] Human Rights Watch, Killings in Eastern Rwanda, p. 9.

[62]"Circumstances in which Policemen Shot Detainees."

[63]Comments by Deputy Commissioner Costa Habyara at a Journe Locale d'Information, sponsored by LDGL (League for the Defense of Human Rights of the Great Lakes), on L'tat des lieux de la criminalit au Rwanda et le role des instances rwandaises charges du maintien de la scurit dans son radication, May 25, 2007, Alpha Palace Hotel, Kigali.

[64]Rural Poverty Portal, http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org/english/regions/africa/rwa/statistics.htm(accessed June 26, 2006).

[65]Human Rights Watch interview with residents of Burimba cell, Shangi sector, March 29, 2007.

[66]Stevenson Mugisha, "Seven arrested over survivor's murder," The New Times, February 18, 2007 http://newtimes.co.rw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=172&Itemid=1 (accessed February 18, 2007).

[67]Human Rights Watch interview with Executive Secretary of the National Service of Gacaca Jurisdictions Domitille Mukantaganzwa, Kigali, March 13, 2007.

[68] Human Rights Watch interviews with residents of Huye sector, February 27 and March 15, 2007.

[69]45,000 FRW is about US $ 80.

[70]Human Rights Watch interviews with local residents, Sovu cell, February 27 and March 15, 2007.

[71]Human Rights Watch interviews with local residents, Sovu cell and Ngoma town, March 15, 2007.

[72]Human Rights Watch interview with senior government official, Kigali, May 13, 2007.

[73] Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, Adopted by the Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and Treatment of Offenders, 1990, principle 9.

[74] Ibid and principle 16.

[75] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, art. 6; Constitution of Rwanda (2003), art. 12.

[76]Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague IV), 1907, art. 50 and Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, Geneva, 1949, Part III, section I, common provisions, art. 33. The imposition of collective punishments happens most frequently in times of war and is rare in times of peace.

[77]ICCPR, art. 7, 9, 14 (1 and 2) and 16; Constitution of Rwanda (2003), art. 19.