—

It was around midday on August 22, 2023, when a white Chevy Malibu slowly drove past Phorn Phanna’s residence in Rayong province, Thailand. Inside the vehicle, three men were watching the exiled Cambodian dissident as he stood in front of his office, looking back at them. He noticed one of the men snap a few photos as the vehicle inched past. A chill rolled down his spine, followed by a deep sense of unease. Shrugging it off, he went back inside his office, assuring himself that it was nothing significant. But dozens of other Cambodian refugees living in Thailand had fallen victim to intimidation and attacks since the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) government took power after a military coup in Bangkok in 2014, so he kept watch on the entrance of the house.

Fifteen minutes later, the white Malibu was back.

That’s when he knew for sure something was wrong. Suspicious and concerned, Phanna hopped on his motor scooter and followed the mysterious vehicle to inquire who they were. But as he drove past and pulled out in front of the car, the three men abruptly exited the vehicle and started chasing after him.

“They did not say anything to me, they just came out and started beating me,” Phanna told Human Rights Watch days after the attack. “They hit me in the jaw and then in my chest.”

The attack was recorded on security cameras of nearby shops and was witnessed by about 10 Cambodian migrant construction workers, who came to Phanna’s rescue.

“They [the assailants] did not panic. And they just walked as normal. Not afraid, they spoke normally. The workers heard them speaking among each other, speaking Khmer.”

In the months prior to the attack, officials from the ruling Cambodian People's Party (CPP) reached out to Phanna through letters, demanding he return home and defect from the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). An official offered him senior positions in the government along with financial promises. Phanna said this same official asked him multiple times to defect since he fled to Thailand in July 2022. After his continued refusals, he received anonymous threats online for a week before the attack.

Phanna runs a group of anti-CPP Facebook pages that collectively have over half a million followers. He also provides support to other exiled Cambodian opposition activists. And like many Cambodian opposition members hiding out in Thailand, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) recognized him as a refugee. At the time of the attack, Phanna was cleared for resettlement in the United States. Thai police arrested Phanna and his family on immigration-related charges in early February 2024. He is still being held in Bang Ken immigration detention center in Bangkok.

“I am very worried about my safety,” he said after the August attack. “I could be abducted and deported [to Cambodia] at any time.” He hoped that whoever was responsible for allowing dissidents like himself to be targeted in Thailand should be investigated and held responsible.

A History of Repression

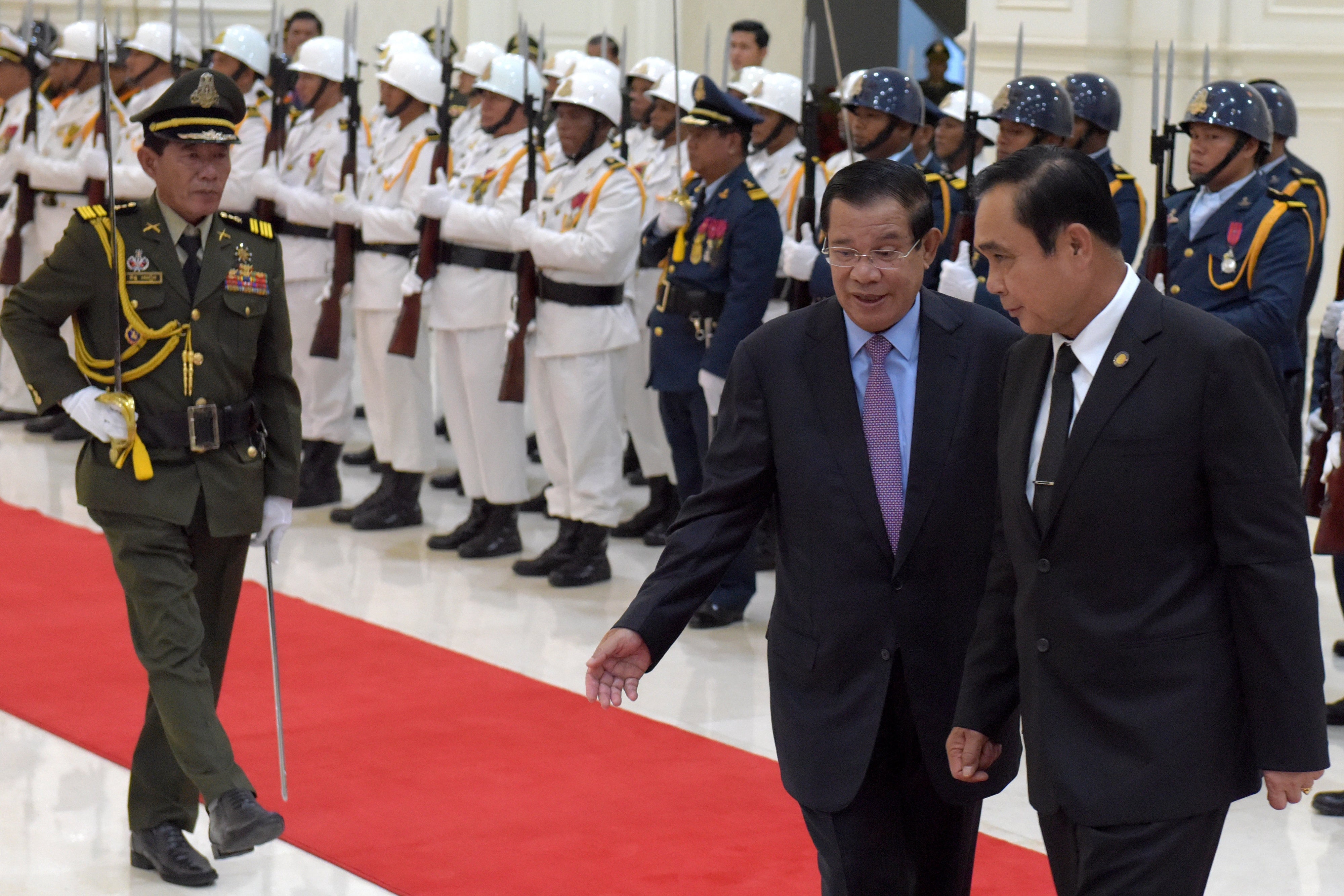

Once a safe haven for exiles from neighboring countries and beyond, Thailand over the last 10 years has become an increasingly unsafe place for those fleeing persecution in their home countries. A growing number of exiled dissidents and activists have been subject to intimidation and harassment, surveillance, and physical violence that have happened across the border—often with the knowledge and connivance of Thai authorities. Of those, Cambodian opposition members and activists make up a sizable number of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch. As detailed below, these practices have been facilitated by the close relationship of former Prime Minister Gen. Prayut Chan-ocha and Thai authorities with the former Hun Sen government in Cambodia.

Governments in Southeast Asia have long been suspected of engaging in quid-pro-quo agreements about refugees and asylum seekers, colloquially known as “swap mart” arrangements. Human Rights Watch’s years of monitoring and media reports show that these became increasingly frequent after the May 2014 military coup in Thailand. Under the National Council for Peace and Order military government that came to power and the post-2019 government of Prime Minister Gen. Prayut Chan-ocha and Deputy Prime Minister Gen. Prawit Wongsuwon, there was an evident spike in repression directed at foreign nationals seeking refugee protection in Thailand, as well as against Thai citizens living in exile in the neighboring countries of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

Human Rights Watch analyzed 25 cases of transnational repression that took place in Thailand between 2014 and 2023.

The term “transnational repression,” sometimes referred to as extraterritorial repression, describes efforts by governments or their agents to silence or deter dissent by committing human rights abuses against their own nationals or members of the country’s diaspora outside their territorial jurisdiction. These abuses include surveillance, harassment, violence, abductions, enforced disappearances, forced returns, so-called digital transnational repression, and harassment of family members.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 18 victims and their families and witnesses to abuses occurring in Thailand and representatives of local and international nongovernmental organizations. The Thai authorities, in addition to facilitating assaults, abductions, enforced disappearances, and other abuses, repeatedly violated the principle of nonrefoulement – the prohibition on returning anyone to a place where they would face a real risk of persecution, torture or other serious ill-treatment, or a threat to life. The countries responsible for the transnational repression of nationals living in Thailand include member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as well as China and Bahrain, among others. Human Rights Watch sent letters to the Cambodian, Chinese, Laos, Thai and Vietnamese governments requesting input regarding the report findings but did not receive any responses at the time of writing.

Despite having refugee status determined by the UNHCR, Thai authorities have repeatedly deported to an uncertain fate exiled critics and dissidents in violation of customary international law. These actions also violate provisions barring nonrefoulement in international treaties ratified by Thailand, such as the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. They have also violated Thai domestic law since the Act on Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearances came into effect in February 2023. Article 13 states:

No state agency or state authority shall expel, return, or extradite a person to another State, if there are substantial grounds for believing that the person would be in danger of being subjected to torture, to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, or to enforced disappearance.

First: Thai military stand guard during anti-coup protests as Gen. Prayut Chan-ocha receives the Royal Endorsement as the military coup leader in Bangkok, Thailand, May 26, 2014. Second: A woman (left) sits inside a police van after being detained by police for holding an anti-coup placard in Bangkok, Thailand, on May 29, 2014.

© 2014 Paula Bronstein/Getty Images and 2014 Nick McGrath/Getty Images

Open Season

After army chief Gen. Prayut Chan-ocha staged a coup and seized control in May 2014, Chinese dissidents in Thailand started going missing. The available information indicates that Thai authorities often targeted them, apparently at the request of the Chinese government, for arrest and refoulement to China.

In November 2015, democracy activists Jiang Yefei and Dong Guangping and their families were living in Thailand as they faced politically motivated charges back in China. Both the men had already faced political repression in China for years. Dong had served three years in prison from 2001 to 2004 on a charge of “inciting subversion of state power.” In July 2014, he was detained for eight months following his involvement in an event commemorating the victims of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests.

Jiang, a political cartoonist, had been residing in Thailand since 2008, after being harassed, arbitrarily arrested, and allegedly tortured for scrutinizing the Chinese Communist Party’s response to the 2008 Sichuan earthquake disaster. He applied for and received refugee status from the UNHCR in April 2015.

Dong arrived in Thailand in September 2015, where he applied for and received refugee status from the UNHCR office in Bangkok. However, on October 28, 2015, just days before they were scheduled to fly to Canada to be resettled there, Thai police arrested the two men. They were immediately taken to Bangkok’s Suan Phlu immigration detention center, an immigration prison where detainees have repeatedly alleged abuse and mistreatment.

The arrests occurred even though the Canadian Embassy in Bangkok had already sent formal letters to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Interior, and other Thai government agencies informing them that the two were being resettled to Canada. The Canadian ambassador also phoned the Ministry of Foreign Affairs permanent secretary directly to emphasize his concerns.

The two men assumed they would be released based on their status as UNHCR-recognized refugees and resettled in Canada. But on the morning of November 12, 2015, two unidentified Chinese officials visited the men at the detention center, according to Jiang Yefei’s wife. The next day, Thai officials then summarily deported the two refugees to China. Both men were detained upon arrival in China.

In response to the deportation, the UNHCR stated: “This action by Thailand is clearly a serious disappointment, and underscores the longstanding gap in Thai domestic law concerning ensuring appropriate treatment of persons with international protection needs.”

Chu Ling and Gu Shu-hua are the wives of detained Chinese dissidents, Jiang Ye-fei and Dong Guang-ping. They were brought to Canada for protection from Thailand, where the two men were arrested and deported to China, despite having UN refugee status, Toronto, Canada, December 8, 2015.

A court in China in July 2018 convicted Dong and sentenced him to three-and-a-half years in prison. He was released after completing his sentence in August 2019. He subsequently escaped China in January 2020 and fled to Vietnam, but the Vietnamese authorities arrested him in Hanoi in August 2022 and returned him to China.

Dong’s daughter, Katherine Dong, told the media that the Chinese government gave the family no information of his whereabouts or why they were holding him. Finally, in October 2023, Dong was released after 11 months in prison for illegally crossing a national border. He currently resides in China, where he remains under close surveillance by the authorities.

After Thailand forcibly returned the two Chinese activists back to China, Thailand’s then-Deputy Prime Minister Gen. Prawit Wongsuwon, who was in charge of security and refugee issues, told UNHCR representatives that he did not know the two men had refugee status, and later made similar claims to the media. But a letter sent by UNHCR to the Thai Foreign Ministry contradicted Prawit’s statement, saying instead that they had reminded the Thai government on November 10 that the men were both refugees. The men’s wives and children were flown to Canada as refugees shortly after Jiang and Dong were forced back to China. On July 30, 2022, Jiang completed his sentence in China but was subject to "deprivation of political rights" following his release.

The Chinese government targeted other Chinese critics in Thailand besides Dong and Jiang in 2015. Gui Minhai, a Hong Kong-Swedish book publisher and writer, went missing while living in Pattaya, Thailand in October that year.

With no word on his whereabouts for months, Gui suddenly reappeared in January 2016 on China’s state television, where he said he was “involved in a drink drive [sic] incident” in China. The broadcast had all the hallmarks of a forced confession. The role of the Thai authorities in his return to China is unclear.

In July 2015, Thai authorities deported at least 109 ethnic Uyghurs held in Bangkok’s Suan Phlu immigration detention center to China. The Uyghurs asserted that they were Turkish citizens and sought to be released to travel there, and Turkey’s embassy in Bangkok backed those claims. Instead, Thai officials transported them from five detention centers across Thailand to a military airport north of Bangkok before handing them over to Chinese officials on July 8, 2015. The group was flown back on a Chinese government plane, escorted by dozens of Chinese police officers.

109 Chinese migrants were repatriated from Thailand, July 12, 2015.

© 2015 CCTVAccording to a Thai government spokesperson, this group of 109 Uyghurs were deported "as per protocol" after authorities identified their country of origin as China, and denied their requests to be allowed to travel to Turkey. Thai authorities have arrested approximately 350 Uyghur men, women, and children and who entered Thailand since 2013.

There are currently at least 43 Uyghur men who remain in indefinite detention in Bangkok’s Suan Phlu Immigration Detention Center awaiting deportation after entering the country without authorization. There are another five who are held in prison, serving sentences linked to their attempts to escape detention centers. The Uyghur refugees are not currently being held under charges as they already served a sentence for illegal entry, but are simply being held pending deportation.

It has been more than 10 years since Thai officials first arrested them, but immigration authorities have prevented any access to these men by lawyers, family members, and anyone else.

Xiang Li, a human rights activist from China, fled in January 2018 to Thailand to escape arrest and likely imprisonment for protesting the arrest of a group of human rights lawyers as well as her involvement in commemorations of the “709” crackdown. The nationwide crackdown on Chinese lawyers and human rights activists began on July 9, 2015, and resulted in at least 300 arrests in China.

“I was able to run away from China, smuggled out,” Xiang told Human Rights Watch. “And after two or three months, I reached Thailand and crossed the border.”

According to Xiang, she hired a driver to take her to an international airport, but instead he dropped her off at an immigration checkpoint. Thai officials held her at a small detention center on an unspecified Thai border for three months, where she endured unclean conditions, dirty food, and significant delays in receiving medical attention, she said.

In July 2018, officials moved her to Bangkok’s Suan Phlu immigration detention center. By this time, she was receiving assistance from various international nongovernmental organizations, UNHCR, and the US embassy, which was working to expedite her resettlement to the United States. But as soon as she arrived at the detention center, she said she started to be observed by apparent Chinese agents, whom she termed “CCP spies,” a reference to the Chinese Communist Party.

“Every night, a Chinese ‘detainee’ would go to my room and look at me, watch me, and take photos from his camera,” she said. “Every night I would see this spy.” Xiang believes this person passed on information and photos about her to the Chinese embassy. On July 23, 2018, Thai officials told her that she could fly to the United States after being granted a visa. But just as she was about to leave the detention center, immigration officials blocked her, saying her ticket had been canceled at the request of the Chinese embassy.

The next day, four Chinese embassy officials came to the detention center and sought to speak with her. They attempted to force her to sign ambiguous documents, but Xiang refused and asked them to leave. Finally, on July 27, Thai officials relented and allowed her to fly to the United States.

“I know many [Chinese dissidents who live in Thailand], but the CCP will go to their houses, and tell them to stop speaking,” she said. “If you continue to speak, they will arrest you and force you to go back to China.”

Fugitive Arrangement

In March 2018, then-Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen and then-Thai Prime Minister Prayut signed a still-confidential “fugitive” arrangement that permits the exchange of each country’s fugitives, which apparently included exiled dissidents and critics of the two governments. Later that month, Cambodia’s then-deputy prime minister and minister of national defense, Tea Banh, visited Bangkok to meet with Prayut and senior Thai officials.

Within months of the agreement, there was a surge of reports from Cambodian dissidents facing surveillance, arrest, and forced return to Cambodia. Particularly targeted were activists from the opposition Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP) living in exile in Bangkok and surrounding provinces who were regularly posting news and information about Cambodia on social media outlets, like streaming on Facebook.

Since then, there have been numerous Cambodian political activists, often with UNHCR refugee status, who have either been summarily deported from Thailand to Cambodia in violation of the principle of nonrefoulement, or arrested and then narrowly escaped deportation after interventions by civil society groups, Bangkok-based diplomats and UN agencies. CNRP members also reported intensive surveillance of their activities by both Thai authorities as well as persons they believed were Cambodian government agents.

Exiled activists from elsewhere in Southeast Asia reported being targeted in Thailand. Vietnamese dissidents were tracked down and abducted. Laos democracy and rights advocates went missing or were killed on Thai soil. A Malaysian LGBT rights influencer was targeted for repatriation but escaped after Australia agreed to resettle her. Thai authorities also arrested Hakeem al-Araibi, a professional football player from Bahrain with Australian refugee status, and nearly extradited him to Bahrain until a global campaign of football players, the professional football federation FIFA, governments, and activists persuaded Thailand not to forcibly send him to Bahrain.

At the same time, left-wing Thai political activists who had fled after the Thai military coup also disappeared from Laos and Cambodia. The mutilated bodies of two of the activists were later found floating in the Mekong River.

Enforced Disappearances

Enforced disappearances of refugees have repeatedly occurred in Thailand since 2014. On August 26, 2019, Od Sayavong, a Lao refugee and prominent critic of the government, disappeared in Bangkok’s Bueng Kum district. The 34-year-old activist was a leader of the Free Laos Group, as well as the Lao United Labor Federation, a network of Lao migrant workers and activists campaigning for human rights and democracy while living in exile in Thailand.

After Od vanished, his colleagues filed a report with the Thai police on September 2, but police failed to undertake a serious investigation, according to lawyers working closely on Od’s case. The Thai police told his family that they closed the case in March 2022 because they could not find any evidence to proceed further.

At the time he disappeared, Od was a UNHCR-recognized refugee in Thailand who was seeking resettlement to a third country. He participated in a number of Free Laos protests in front of the Lao embassy in Bangkok, and frequently spoke out at events and on social media. The group also protested to demand the Lao government recognize the rights of victims of government land grabs and dam collapses that reportedly left hundreds without land and livelihoods. Od also advocated for the release of three laborers who received long prison sentences in Laos in April 2017 because of the public criticisms they made of the Lao government while working in Thailand. He had also called for an investigation into the enforced disappearance of the Lao civil society leader Sombath Somphone, who was abducted at a police checkpoint in Vientiane in 2012.

Three months after Od’s disappearance, Phetphouthon Philachane, another member of Free Lao who was also a housemate and friend of Od, went missing after he left Bangkok to visit his family in Vientiane. A group of nongovernmental organizations reported in May 2023 that he had not been seen since.

Emilie Palamy Pradichit, the founder and executive director of Manushya Foundation, which promotes community empowerment and human rights, told Human Rights Watch that Lao political activists living in Thailand have been targeted abroad by the Laos government on multiple occasions.

“The targeting of Lao activists beyond their country's borders highlights the insidious nature of transnational repression,” Pradichit said. “It's a stark reminder that authoritarian regimes will stop at nothing to silence their critics.”

Following the abduction of Od Sayavong and other Lao activists, Pradichit and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights engaged Thai authorities to investigate Od’s disappearance. A joint allegation letter submitted to Thai authorities did not result in any substantial action being taken.

In the early evening of April 13, 2023, in Pathum Thani province, unidentified men abducted Duong Van Thai, a Vietnamese rights activist and independent journalist who is a UNHCR-recognized refugee, while he rode his motorcycle back home from a coffee shop. As a prominent critic of the government with excellent information sources back in Vietnam, his criticisms on his YouTube channel and other social media garnered attention in both the Vietnamese diaspora as well as in Hanoi. He had lived in Thailand since 2020 and the day before his abduction, he visited UNHCR’s Bangkok office to discuss refugee resettlement options, according to media reports.

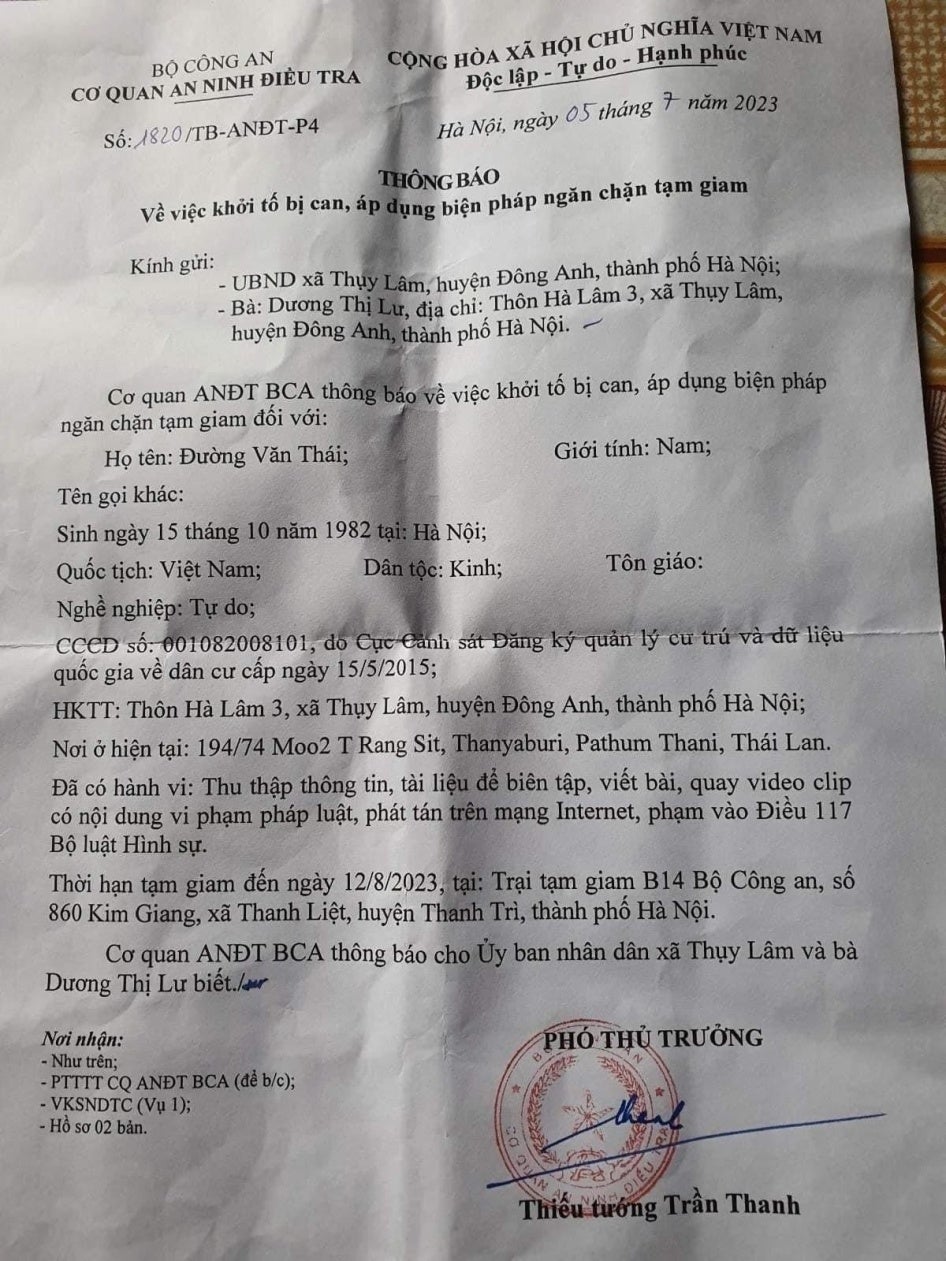

First: Duong Van Thai, a Vietnamese rights activist and independent journalist. Second: A notification letter was issued to Duong Van Thai’s family by Vietnamese officials to inform them of his arrest.

© Duong Van Thai/Youtube and PrivateSeveral days after his abduction, Vietnamese friends living in Thailand went to Duong Van Thai’s home to search for him because he wasn’t returning calls or text messages. They found his wallet with his UNHCR card and bank cards still inside. They also discovered his laptop and other important personal items in his home, indicating he had not intended to return to Vietnam, as the Vietnamese government alleged three days after the abduction. The Vietnamese authorities claimed he was arrested while illegally entering the country.

Vietnamese police reported that authorities in the Huong Son district of Ha Tinh province were holding him. However, according to the Vietnamese government’s July 5, 2023, notification of his arrest and detention sent to his relatives in Vietnam, officials listed Duong Van Thai’s address in Bangkok, which revealed they knew his precise whereabouts there.

Furthermore, Vietnamese officials issued a notification to his family in Vietnam on July 5, noting he would initially be held until August 12. Under Vietnamese law, the pretrial detention for serious crimes is set at four months, and that period is renewable. It is notable that he was abducted in Thailand on April 13, 2023, which is exactly four months before August 12, 2023.

Human Rights Watch observed a video of Duong Van Thai’s abduction. The footage clearly shows men forcibly dragging and pushing the screaming man into a car.

Duong Van Thai’s friends and rights groups report that prior to his abduction, he feared persecution for posting videos online that scrutinized the Vietnamese government. He told a friend that on April 6, 2023, a man riding a motorbike approached his house to film and take photos. Subsequently in July, the Vietnamese authorities charged him with violating penal code article 117 for conducting “propaganda against the state.” He is still in police detention awaiting trial, but was allowed to meet his mother once in January 2024.

Surveillance and “Snatch Squads”

Hong Quyen Bach waited by a high-floor window of a Bangkok hospital where he could see vehicles approaching the building’s bustling front entrance. The exiled Vietnamese political activist was looking for his wife’s car. Days earlier, they agreed to secretly meet at a hospital for their child's health checkup. The precautions came after he discovered he was being followed by “mysterious Vietnamese men,” he told Human Rights Watch.

When his family’s car pulled up to the hospital, he saw his wife and two daughters exit the vehicle and walk towards the building. But he also noticed something that made his heart drop.

“When my family arrived at the hospital, there was a white car following them,” he told Human Rights Watch in August 2023. “After my family got out, there were Thai police getting out of that white car as well, and they followed my family to the entrance of the hospital. After that, a Vietnamese officer got out of that same white car.”

Hong Quyen Bach had fled Vietnam in May 2017 when the authorities issued an arrest warrant for him for “disturbing public order” after he led a protest criticizing the Formosa Ha Tinh Steel waste spill, which polluted the coast of central Vietnam.

But the surveillance didn’t start until he assisted Radio Free Asia writer Truong Duy Nhat.

Truong Duy Nhat, 57, a former journalist known for criticizing the Vietnam government in blog posts, fled to Thailand in January 2019 to escape multiple criminal charges, including an “act of abuse of power and/or authority in performance of official duties.” Bach helped him when he got to Bangkok to find accommodation and apply for refugee status determination with UNHCR in Thailand. Then on January 26, Nhat went missing from a shopping mall in Bangkok, just a day after he applied for refugee status, according to local reports.

“Truong Duy Nhat and I had a commitment that we would never turn off our phones. If the phone was running low on battery, we would ensure that we text each other and make sure that we knew that we were running out of battery, so we know that everything is okay,” Bach said. “But I didn't receive any notification. After that, I went to the hotel where Nhat was staying to double check, but the hotel said Nhat never came back. So, at that time, around 6:30 p.m. that day, I was sure that Nhat was arrested.”

Amnesty International later reported that Thai authorities detained Nhat while he was at a shopping mall in Pathum Thani, and handed him over to Vietnamese police officials that same evening. According to the decision by the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, the Vietnamese agents transported Nhat to Vietnam, and tried him on March 9, 2020, for “abuse of power or position in performance of official duties” under penal code article 356(3). Nhat received a 10-year prison sentence, which the Working Group determined was arbitrary.

Bach believes that Vietnamese authorities targeted him for abduction or arrest as well. He feared he would be the latest victim in a string of violent incidents targeting Vietnamese activists in Thailand, including abductions, beatings, and other forms of harassment since 2015.

Hong Quyen Bach was resettled on an expedited basis days after the abduction of his friend Nhat, when it became clear Vietnamese officials were looking for him because he knew about what happened to Nhat. Bach is now safely living in Canada.

“I believe that the Vietnamese government is [targeting] activists now and will continue to do so in the future,” Bach said. “They will keep sending agents overseas to track down exiled activists.”

The surveillance of exiled activists in Thailand by plainclothes police or unidentified men who might be agents of foreign governments appears to be common. Human Rights Watch examined more than a dozen such cases in recent years, which can evolve into intimidation and harassment, and at times violence.

“Because of my activities, I was under surveillance from Hun Sen's spies,” Tor Nimol, a CNRP activist, said in July 2023. “And Hun Sen cooperated with the Thai military, and arrested me and deported me to Cambodia in 2019.”

On November 23, 2019, Thai police picked up Nimol at a Big C shopping center in Bangkok when he was shopping with his wife. Nimol told Human Rights Watch that at least eight plainclothes Thai police officers surrounded him inside the store, then escorted him outside where more plainclothes police were waiting. They placed him inside a van, and handcuffed him to his wife. The police then drove them around the area for approximately two hours before meeting up with another vehicle driven by Cambodian government officials, who took control of the couple.

“The Cambodians didn't talk to me, but they spoke with their Thai police colleagues,” Tor Nimol said. “One informed his officer that I needed to be transferred immediately to Cambodia. I could not use my phone because the phone was taken away from me at the Big C. Even my [UNHCR] card they took away from me.”

The Cambodian officials then drove the couple to the Thai-Cambodia border, and they crossed at Poipet in western Cambodia, where he was handed over to approximately 20 Cambodian soldiers.

“The military forces showed me their guns, and said not to run or I would be gunned down,” Nimol said. “At that time, it was night, and they could kill me, and no one would know.”

Cambodian officials then conveyed Nimol and his wife to Phnom Penh, where they forced him to publicly denounce exiled CNRP leader Sam Rainsy. However, just four days after he was released on bail, he and his wife escaped again to Thailand where they waited to be resettled for another two years. The couple has been living in Canada since November 2021.

Physical Attacks

Surveillance, intimidation, and arrest are pervasive threats faced by many asylum seekers and refugees in the dissident community in Thailand. But they at times also experience physical attacks. Human Rights Watch is aware of at least four cases since 2014 in which exiled dissidents in Thailand were physically attacked by unidentified assailants that appear to be linked to foreign security forces. When including Thais who have been targeted in other ASEAN countries, the number rises to at least 13.

Suon Chamroeun, an opposition Cambodian activist in exile in Bangkok, is very familiar with the threat of violence. He survived one attack and narrowly escaped abduction.

On December 22, 2019, at about 9:30 p.m., Chamroeun walked into a 7-Eleven minimart just steps away from the entrance of his apartment building to purchase cold medicine. When he stepped out of the store, two men stood in front of him. They had the appearance of bodyguards and presented an obvious intent to confront him.

“Please come with us, brother. Our boss needs to talk to you,” one of the men said in unaccented Khmer. “You messed up.”

Fearful for his life, Chamroeun fled back inside the 7-Eleven. For the next 15 minutes in front of the startled 7-Eleven staff and customers, the assailants attacked Chamroeun with a stun gun, trying to subdue him and drag him out of the store. They also beat him in the head, back, arms and legs, and repeatedly used electric shock against him until the batteries in their devices were fully depleted.

“The [stun gun] ran out of electricity because they used it on me too much, on my neck, my back, everywhere in my body,” Chamroeun said.

Opposition Cambodian activist Chamroeun Suon displays injuries he sustained after two assailants attacked him in Bangkok, Thailand on December 22, 2019.

© 2019 PrivateWhen the 7-Eleven employees announced they had called the police, the unidentified men gave up on their repeated attempts to pull Chamroeun into their van parked across the small street and fled the scene. Chamroeun got to his feet and saw the van drive off.

Chamroeun was just one of the many political dissidents that the Cambodian government labeled as a traitor for allegedly “plotting to topple the government.” Facing arrest on those bogus charges after the government-controlled Supreme Court dissolved the CNRP in November 2017, many opposition members fled to Thailand.

Chamroeun and others in exile in Thailand believed the Hun Sen government was sending agents to search for and act against activists seeking refuge there. Chamroeun said in the months prior to his being attacked at the 7-Eleven, things had quieted down.

“We thought that we had reached a point of safety, so we were not taking care of our security,” Chamroeun said. “We thought we were safe. But we were not.”

Exiled Lao activists have also been attacked, and even extrajudicially killed. On May 17, 2023, unknown assailants shot and killed the exiled Free Lao movement political activist Bounsuan Kitiyano in Si Mueang Mai district of Ubon Ratchathani province in northeastern Thailand, near the Laos border. The local police investigation indicated that he was shot multiple times while riding alone on his motorcycle on a rural road. A Thai military intelligence official told Human Rights Watch that it was “clearly a professional killing” and ridiculed local police speculation that Bounsuan was killed by relatives unhappy with his political activities. According to media reports, Bounsuan was a UNHCR-recognized refugee who was in the process of applying for resettlement to Australia.

Across the border in Laos, exiled Thai anti-monarchy dissidents had also started disappearing. Since 2016, at least nine Thai activists have either gone missing or been found dead under mysterious circumstances.

Disappearance of Thai Nationals

In December 2018, three prominent Thai activists – Surachai Danwattananusorn, Chatcharn Buppawan, and Kraidej Luelert – went missing while living in exile in Laos. Shortly after their disappearance, two bodies washed up along a rocky shore in Nakhon Phanom province on the Thai side of the Mekong River.

When police arrived at the scene, they found the bodies were handcuffed, disemboweled, and stuffed with concrete bricks to sink the bodies to the river bottom. Forensic teams conducted DNA tests that confirmed the bodies belonged to Chatcharn and Kraidej. Surachai’s body was never found, but since the three men lived in the same place when they disappeared, he is presumed dead. Surachai was one of Thailand’s most well-known dissidents, and at the time had a 10 million baht (US$290,000) Thai government bounty on his head. Neither the Thai nor the Lao governments conducted a serious investigation into this case.

In May 2019, Siam Theerawut, a Thai underground anti-junta radio host and activist, went missing along with two other anti-monarchy figures, Chucheep Chivasut and Kritsana Thapthai. Fellow activists told Human Rights Watch they received word that Vietnamese immigration officials had detained the group of men at an airport in Vietnam for using fake Indonesian passports. The last communications from the men to friends and relatives in Thailand came from the city of Vinh, in central Vietnam. Reliable sources told Human Rights Watch that the trio were deported back to Thailand, although the Thai government denied this.

Siam’s mother, Kanya, accompanied by his sister Ink, told Human Rights Watch in August 2023 that there had been no definitive answers about what happened to her son. Siam’s disappearance and the whereabouts of the other two men remain unresolved.

“We don’t have any answers about where he is, or what happened,” Kanya said. “There is no justice for him, or others like him.” The devastation of families, and a debilitating lack of closure are common elements that arise in the wake of enforced disappearance cases.

At least two other Thai political activists and dissidents – Ittiphol Sukpaen and Wuthipong Kachathamakul – have been abducted in Laos, in June 2016 and July 2017, respectively, and there is no information about their whereabouts. Two witnesses said that the 10 armed men who abducted Wuthipong outside his house in Vientiane were Thai speakers wearing balaclavas to hide their identity.

Wanchalearm Satsaksit, a prominent Thai political activist and critic of the Prayut government, was abducted by unidentified men in Cambodia in June 2020 and remains missing.

Sitanan Satsaksit, the sister of Thai activist Wanchalearm Satsaksit, and Pornpen Khongkachankiet, the director of the Cross Cultural Foundation in Bangkok, conducted their own investigation shortly after Wanchalearm’s disappearance. They found that unidentified men arrived at his apartment building in Phnom Penh in a black SUV, grabbed him in front of the building, shoved him into the vehicle and drove away, Sitanan told Human Right Watch. She happened to be on the phone with her brother during his abduction. His last words to her were: “I can’t breathe,” following repeated banging sounds on the other end of the line.

Placards with Wanchalearm’s face, calling for his safe return, became a prominent feature in Thailand’s 2020 mass protests when thousands filled the streets in Bangkok and other cities calling for democracy and the reform of the monarchy.

Repeated Disregard for Refugee Status

The Thai government has repeatedly shown disregard for the refugee status of exiled dissidents. Even when someone is a UNHCR refugee card-holder, Thai authorities have shown no hesitancy to arrest, and in some cases summarily deport them to face persecution in their home countries, in breach of Thailand’s international legal obligations.

In December 2021, Thai police detained a highly regarded Cambodian monk, the Venerable Bor Bet, physically disrobed him and planned to forcibly deport him. He was an outspoken critic of the Cambodian government and an environmentalist who had called for better protection of the country’s forests. Officials lodged incitement and treason charges against him, forcing him to flee to Thailand. For about 10 months, he hid out at a temple in Samut Prakan province. Thai officials eventually tracked him down, barged into the temple on a Friday night, forced him to take off his monastic robes in line with police procedures when detaining a Buddhist monk, and eventually took him to Suan Phlu immigration detention center.

First: Thai police arrest Bor Bet, a Buddhist monk and Cambodian activist living in exile, at a temple in Samut Prakan province, Thailand in December 2021. Second: Thai authorities pressure Bor Bet to disrobe and put on civilian clothes as he is detained at a temple in Samut Prakan province, Thailand, December 2021.

© 2021 Private“I suspected that there were spies at the time when I was arrested,” Bor Bet told Human Rights Watch. He said that a supposed friend had urgently asked to visit him and demanded to know his precise location. “I said: ‘Okay, you can come this evening.’” But the person never showed. Instead, a group of more than 10 armed Thai police came to the temple.

“I heard someone over the police radio telling a person in Khmer that I was arrested already,” Bor Bet said. “Then over the radio, the Khmer voice, who was giving the orders, said: ‘Deport him as fast as possible.’”

Despite Bor Bet showing his UNHCR refugee card, Thai police took him to a police station, then to the Samut Prakan immigration detention center, and finally the Suan Phlu immigration center in Bangkok where he awaited deportation. One Thai senior police officer openly told Bor Bet that the order was coming from the Ministry of Interior in Thailand, citing “cooperation between the Thai Interior Ministry and Hun Sen's regime.”

Photos of police compelling Bor Bet to take off his monk's robes were obtained by CNRP activists in Bangkok, who made them public, prompting a massive negative reaction on Thai social media about arresting a monk. An aide to then-House Speaker Chuan Leekpai traveled to Samut Prakan immigration to intervene. Foreign embassies sent the Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs messages of concern and the government of Switzerland agreed to resettle him expeditiously if he were released. Ultimately the backlash from the Thai public and resulting political pressure compelled the Thai authorities to abandon plans to force Bor Bet back to Cambodia. He is now residing in Switzerland.

—

Thai police ignored the UNHCR-endorsed refugee status of Nur Sajat, a popular Malaysian transgender social media influencer, television host, and LGBT activist who fled to Thailand in February 2021. One month before she fled, Malaysian authorities arrested her for “insulting Islam” because she wore female clothing at a religious ceremony, a charge that carries a five-year prison sentence. Sajat told Human Rights Watch that three men beat and sexually assaulted her while she was in jail before her release on bail.

Nur Sajat fled before her trial, fearing further abuse if she was sentenced to prison. After crossing into Thailand surreptitiously, she traveled to Bangkok and sought refugee status, which the UNHCR quickly granted.

The Malaysian government’s persecution of Sajat dated back to 2020, when the government threatened to shut down her social media accounts after she shared her videos and photos wearing women's prayer robes.

Sajat told Human Rights Watch that in the years preceding her arrest, she never hid her identity as a trans woman and was open about her Islamic faith. She won the Miss International Queen talent competition in 2013, and says she was born intersex and raised as a girl while still being raised a Muslim.

On February 25, 2021, Thai police raided the apartment where she was staying in Bangkok and arrested her for entering the country illegally. Thai immigration had been tipped off by their counterparts in Malaysia, who told Bangkok that they had canceled her passport and sought her extradition. Quick interventions and massive publicity on her case by Bangkok-based diplomats, UN agencies, Human Rights Watch,and other human rights organizations, and national and regional LGBT groups prompted the Thai government to pause, and ultimately walk back their initial agreement to deport her to Malaysia. Nur Sajat was ultimately resettled in Australia.

“When the Thai police got the information from the Malaysian government, they searched for me and then found me,” Sajat said.

Violations of Domestic and International Law

All governments have an obligation to protect the human rights of foreign nationals residing within their borders. This means not cooperating in efforts by foreign governments to unlawfully obtain the return of their nationals – a form of transnational repression – that would violate the rights of refugees and asylum seekers under the Refugee Convention or the Convention against Torture.

Thailand is a party to the Convention against Torture. While it has not ratified the Refugee Convention, it is nonetheless bound by the principle of refoulement, the customary international law prohibition against returning anyone to a place where they would face a threat to their life or a real risk of persecution, torture, or other ill-treatment.

The Thai government’s cooperation in transnational repression by foreign governments would also violate Thai domestic law. On February 22, 2023, Thailand’s parliament passed the Act on Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearances, which went into effect on September 22, 2023. The law stipulates that no person in Thailand should be expelled or returned anywhere where they may face persecution, such as torture, ill-treatment, and enforced disappearance. While this legislation has flaws, it clarifies that refoulement practices used by Thai authorities for decades are unlawful.

“Swap Mart” Agreements

The existence of “swap mart” arrangements – agreements between governments to forcibly return exiled dissidents – are difficult to verify with respect to Thailand. However, after the military took control of the country after the May 2014 coup, Thailand saw an increase in repression in many forms. Human Rights Watch has documented the repeated arbitrary detention of protest leaders, violent crackdown on peaceful protesters, ongoing judicial harassment of activists, and a clampdown on free expression, among other forms of repression. Reaching “swap mart” arrangements with other abusive governments to facilitate transnational repression would be consistent with the evidence gathered.

“When we are talking about returning, or the swapping of political activists, it could be done very quickly,” said Pornpen Khongkachankiet of the Cross Cultural Foundation. “In some cases, the [authorities] say: ‘Oh we did not know.’ But in some cases, they did not ask, so they did not tell. Then they return them so quickly without any intervention or interception by other organizations.”

Pornpen expressed concern that the Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Act would have little impact given that Thai authorities on a number of occasions claimed they did not know that immigration detainees were refugees before deporting them.

Rath Rott Mony, a Cambodian political exile, former trade unionist and journalist arrested by Thai police in front of the Netherlands embassy in Bangkok, and deported to Cambodia in December 2018, said Cambodian officials told him about the existence of the “swap mart” arrangements while he was detained in Phnom Penh. Mony had fled to Thailand after working on the Russia Today documentary “My Mother Sold Me,” about sex trafficking of children in Cambodia. The documentary angered top officials in the Cambodian government who claimed that it contained fake accounts and filed charges against Mony, who worked as a fixer and translator on the film.

Even after pleading with Thai police that he would “be killed or put in jail” if he were sent back, Thai authorities forcibly returned him to Cambodia within days of his arrest. He had been tried in absentia, so officials sent him directly to prison in December 2018 to serve a two-year term.

While in prison, Mony heard multiple accounts in hushed tones of the “swap mart.”

"When I was arrested in Cambodia, people sometimes talked about Wanchalearm,” Mony said, referring to the prominent Thai dissident activist who was abducted and then forcibly disappeared in 2020. “Some people said: ‘You have been exchanged for some Red Shirt activist. And the police officer said: ‘Mony, you were just a translator. Not a big problem. But the problem is the Thai Red Shirt activist [we have in custody]. They [the Thai authorities] want him.’"

The “Red Shirts" are a Thai political movement affiliated with the Pheu Thai Party, which led the government toppled in the May 2014 military coup. After the coup, the military sought to arrest key Red Shirt leaders, but many fled to neighboring countries such as Cambodia and Laos.

Mony’s account of his detention and forced return to Cambodia suggests that he was exchanged for a Red Shirt activist as a quid pro quo. He said that when he was being deported from Thailand to Cambodia, Thai authorities openly discussed that there was a “high financial cost” required for his exchange.

“When I was in the [Cambodian] Ministry of Interior, I was locked in a room,” Mony said. “I was handcuffed, I had to sleep on the floor. And at that time, the police were talking about how they had a Thai Red Shirt. There was talk that me and the Thai [activist] would stay in the same room. But the officer said: 'No, the Red Shirt activist is fighting against the Thai government. You are just an international journalist.’” Mony told Human Rights Watch he did not know the activist for whom he was exchanged.

__

The cases in this report just scratch the surface of the collaboration between Thai authorities and officials from neighboring countries in surveillance and harassment of political dissidents seeking refuge in Thailand. At times this collaboration has led to physical attacks, arrests, forced returns, and enforced disappearances.

The new Thai government of Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin that resulted from the May 2023 election has an urgent obligation to end the “swap mart” and other such arrangements, and take action to resist and expose transnational repression of all forms by foreign governments pursuing exiled dissidents in Thailand.

RecommendationsTo the Government of Thailand

To the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand

To the Government of Cambodia

To the Government of Laos

To the Government of Vietnam

To the Government of China

To the United Nations

To concerned governments including the US, EU, UK, Australia, Canada, Japan, and South Korea

|

AcknowledgmentsWritten by Caleb Quinley, consultant to Human Rights Watch, and edited by Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director; James Ross, legal and policy director; and Tom Porteous, deputy program director. Reviewed by Bill Frelick, refugee and migrant rights director; Nadia Hardman, refugee and migrant rights researcher; Editorial and production assistance was provided by Audrey Gregg, Asia associate; Maggie Svoboda, photo editor; and Travis Carr, digital publications officer. We gratefully acknowledge the victims of abuses, their families, witnesses and others who shared their stories or provided us with valuable guidance and insight. |