Summary

Ruben Villegas died on Friday, September 3, 2021, from severe injuries he sustained one week earlier in a car crash. According to local media reports, on the night of the crash DPS officers saw five men run into the brush after getting out of Villegas’ silver Chevrolet Malibu when it was parked at a rest stop. Texas Department of Safety (DPS) officers, or “Texas state troopers,” attempted to stop the vehicle, but Villegas sped away, and officers pursued him for more than 20 miles. DPS suspected him of transporting unauthorized migrants, which may be a legitimate reason to attempt to stop a driver but not a reason to engage in a dangerous high-speed chase.

The pursuit, reaching speeds of 120 miles per hour and including the use of a helicopter, resulted in Villegas losing control of his car and crashing into and damaging the property of a Texas business owner, Norma Saldaña. Villegas and three injured men found in his trunk were taken to a local hospital. A news release from DPS stated that Villegas, had he survived the crash, would have been charged with human smuggling and evading arrest with a vehicle once he was released from the hospital.

In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Norma Saldaña expressed her support for law enforcement “securing the border.” Nevertheless, she found the entire experience upsetting and was angered by the harm she suffered in the incident. Her father, an older person, had been present when the car crashed into the fence, though he was indoors and suffered no physical injuries. Her property (an elaborate and expensive fence valued by Saldaña at $25,000) was destroyed by the chase and she was not compensated by the agencies responsible. She also said, “You know what I had to do the next day after that accident? Because there was so much blood on the ground? So much blood everywhere! I had to take some holy water and sprinkle it over the ground.”

Law enforcement had options short of engaging in this chase. They could have abandoned the pursuit when it was clear it was becoming a high-speed chase that foreseeably put the driver and others at risk. DPS, after 20 miles of pursuit, presumably had the license plate number, were tracking the car from the air, and could have apprehended the driver later. But law enforcement policies and incentives, especially those put in place by Texas’ Operation Lone Star (a border law enforcement initiative) lead to just such ill-advised, reckless, and too often fatal encounters with law enforcement.

Operation Lone Star’s Vehicle Pursuits are Dangerous and Deadly

Prior to his death, Villegas was a resident in McAllen, Texas, just a few miles from where the crash occurred. The vehicle pursuit that took his life, endangered the lives of his passengers, caused harm and likely trauma to Saldaña and her older adult father, and caused extensive damage to the property of a Texan, is one of many such incidents Human Rights Watch has tracked since the start of Operation Lone Star (or “OLS”), a program initiated by Texas Governor Greg Abbott. These vehicle pursuits, explicitly incentivized by OLS, are harming Texans and unauthorized migrants alike.

Across the United States, police departments have adopted restrictions on when law enforcement can engage in a vehicle pursuit. Some, such as the Houston Police Department, have adopted policies restricting the use of vehicle pursuits. Such restrictions reflect growing recognition that pursuits lead to a “high risk of loss of life, serious personal injury, and serious property damage.” In fact, when releasing the Houston Police Department’s new vehicle pursuit policy in September 2023, Houston Police Chief Troy Finner told members of the press, “We should not pursue every vehicle that flees from us. We don’t have to give up the search for the suspect when we give up the pursuit.”

In contrast to Chief Finner’s words, Texas DPS has not restricted vehicle pursuits. Under Operation Lone Star, Texas DPS and several other law enforcement agencies have engaged in dangerous and deadly pursuits on a weekly basis in the 60 counties implementing OLS or experiencing DPS deployments under OLS (called “Operation Lone Star counties” in this report). Counties that opt in to the program receive state appropriated funds.

According to media reports indicating the pursuits involved vehicles containing migrants, as well as DPS records obtained by Human Rights Watch under state public records laws, in the 29 months between the start of OLS in March 2021 and July 2023, at least 74 people were killed and another 189 injured as the result of 49 pursuits by Texas troopers or local law enforcement, or both, in Operation Lone Star counties. That is a rate of nearly 3 deaths and 7 injuries per month that OLS has been in existence, a significantly higher toll than the nearly 2 deaths per month previously reported by media and civil rights groups, and higher than the toll in other Texas counties over the same period. Of the 5,230 total vehicle pursuits that DPS troopers engaged in across Texas’ 254 counties since March 2021, 3,558 of them, or roughly 68 percent of all pursuits, occurred in the 60 Operation Lone Star counties that represent 13 percent of the state’s population. This means Operation Lone Star county residents are experiencing a disproportionate share of vehicle pursuits across the state.

Some of the people killed and injured by vehicle pursuits in OLS counties were not directly involved in the pursuits, and some of these were children. Among the bystanders killed was a 7-year-old girl, and among bystanders injured were five children of unknown age – all of them Texas residents. While some pursuits begin with reckless driving or evasion of arrest by the pursued vehicle, it takes very little for law enforcement to initiate a pursuit: 81 percent of the vehicle pursuits that occurred in Operation Lone Star counties were initiated because of a traffic violation, 97 percent of which were traffic misdemeanors such as failure to obey an attempted stop by law enforcement, speeding, or not obeying traffic signals.

Operation Lone Star is a set of measures Texas Governor Gregg Abbott initiated in March 2021 with the purported aims of stopping “the smuggling of people and drugs into Texas” and deterring or arresting migrants attempting to cross the Texas-Mexico border. Central components have included deployment of some 10,000 National Guard forces and at least 1,000 DPS troopers to Operation Lone Star counties, pursuit of vehicles suspected of transporting migrants, and—in a separate criminal legal system created solely for OLS—arresting, prosecuting, and imprisoning people for smuggling (driving cars containing suspected unauthorized migrants) and for trespassing (when people suspected to be unauthorized migrants walk over private property), among other criminal offenses.

Abbott’s strategy has been to declare an uptick in US-Mexico border crossings a “disaster” for the state and to convince county officials to do the same. While open-source media searches reveal isolated incidents, such as one reported by Fox News on August 3, 2023, in which individuals alleged to have “suspected ties” to cartels are apprehended at or near the border, the vast majority of migrants arriving to the Texas-Mexico border are seeking safety, family reunification, or simply a dignified life. Abbott’s “disaster” declarations therefore employ false, dangerous, and racist rhetoric that conflates migrants with dangerous invaders bringing drugs, violence, and crime to Texas.

Within days after Abbott’s first “disaster” declaration, 500 National Guard forces volunteered for deployment and by the following fall, thousands of Texas state troopers and soldiers descended on border communities with orders to arrest migrants on state charges including criminal trespass, a workaround that allowed Texas to use state law to effectively assume federal immigration enforcement authority, under which federal authorities already carry out apprehension and prosecution of unauthorized migrants.

To handle the growing volume of arrests, Texas has established a separate criminal legal system in tent facilities that charges and detains both migrants and Texans suspected of assisting them, jails them in converted state prisons, and handles their criminal cases with judges called back from retirement or diverted from other duties.

The Operation Lone Star apparatus functions as a shadow system of racialized border control, rife with human rights violations documented by Human Rights Watch in previous publications: it separates families; it improperly imposes penalties on refugees for crossing the border without authorization; impedes and in many cases effectively denies the right to seek asylum; and forces mostly defendants of color to languish in deplorable jail conditions, often in custody due to unaffordable bond amounts, while waiting for charges to be filed, attorneys to be appointed, and court hearings to be scheduled. As asylum seekers and migrants are prosecuted under Operation Lone Star, it may subject them to new criminal convictions that could deprive them of the ability to gain asylum under US law. It also creates a chaotic and militarized environment in which law enforcement agencies have a very visible presence in Texas counties, with trucks and uniformed and armed personnel alongside roadways and in cities and towns. These agencies engage in vehicle chases and other risky maneuvers on a daily basis that foment fear in Texans, threatening rather than ensuring public safety.

Amid the state-orchestrated chaos wrought by OLS policies and practices, Texas is funding a border wall, busing migrants to other US cities, and installing dangerous floating barriers on the Rio Grande and razor wire along its banks.

As OLS has evolved and metastasized, the costs have ballooned to nearly $10 billion in spent or allocated funds. Though the state legislature initially appropriated about $3 billion for the initiative, officials quickly spent these funds as Governor Abbott increased Operation Lone Star deployments to 10,000 troops, requiring emergency cash infusions of another $1.4 billion to keep the effort afloat over a period of approximately nine additional months, until June 2023.

In May 2023, the Texas legislature allocated another $5.1 billion for the next two years of the program, resulting in annual expenditures nearly ten times what Texas spent on border enforcement just a decade ago.

Human Rights Watch is not aware of any evidence that Operation Lone Star is making measurable progress towards its stated goals to “deter migration” and thwart cartels involved in drug trafficking and people smuggling. A detailed analysis in March 2022 by the Texas Tribune showed that data the governor cites as evidence of progress involves statewide drug seizures, rather than just those tied to OLS. A similarly detailed analysis in July 2023 by the Wall Street Journal found that US citizens have been targeted by OLS, the arrests under OLS are often dismissed for being discriminatory, and the part of the border targeted by OLS has seen the most rapid increase in unauthorized migration in the state since the program began.

The incentivizing of vehicle pursuits starkly highlights the false logic of Operation Lone Star: justified as necessary to protect the public from mythical dangerous migrants, in fact it is OLS policies themselves that put public safety at risk. Law enforcement pursuits of vehicles suspected to be transporting migrants, like the incident that claimed the life of Ruben Villegas and caused Norma Saldana’s property loss, are increasing, and leading to avoidable death, injury, and destruction of property.

Vehicle Pursuits Are Increasing, with Common Patterns of Harm

Department of Public Safety (DPS) deployments in Operation Lone Star counties have led to dramatic and measurable increases in vehicle pursuits. Whereas an average of 140 pursuits per month were conducted by DPS across the state in the year prior to OLS, an average of 201 per month have taken place in the roughly two years since it began.

In El Paso County, for example, pursuits by state troopers increased by hundreds between January and April 2023, the first four months the county was involved in Operation Lone Star. In Kinney County, vehicle pursuits by state troopers increased from 22 in the 12 months before OLS began in March 2021, to 227 in the 26 months since OLS has been in effect in the county.

The data analyzed for this report reveals disturbing patterns. The drivers who die during vehicle pursuits are overwhelmingly young Texans, many of them people of color, who were recruited through social media platforms to drive people from border communities to destinations within the state. Passengers—mostly migrants (who may be recently arrived asylum seekers seeking safety, or migrants seeking to reunite with family members in the US or to build a dignified life)—perish at an alarming rate. Unsuspecting motorists, among them Texas residents going about their daily lives, have been killed and injured. In some cases, Texans’ property has been destroyed.

Operation Lone Star Encourages Overzealous Law Enforcement

From state and local police records reviewed by Human Rights Watch, a picture emerges of overzealous and reckless law enforcement carried out by various law enforcement agencies whose agents rely on racial profiling and pretextual stops (in this case using a traffic violation stop to investigate another offense), engage in vehicle chases, and fail to terminate pursuits despite high speeds, bad road conditions, traffic, and proximity to residential and other populated areas.

Officers rely on stopping vehicles for alleged traffic violations—including in circumstances that indicate the stop was pretextual—to determine if the vehicles are transporting migrants. The reasons they give for suspecting that migrants are in the vehicle at times sometimes suggest reliance on racial profiling.

Traffic violations like running stop signs can turn into dangerous pursuits. The data analyzed by Human Rights Watch for this report show how reckless the pursuits can be: one vehicle pursuit by Texas state troopers in the Operation Lone Star county of Kenedy reached a maximum speed of 180 miles per hour. Across all of the documented chases, the average maximum speed was 91 miles per hour.

When Texas state troopers are not initiating pursuits because of a traffic violation, they are often joining or taking over an active pursuit initiated by another agency, including local police and federal agencies like Border Patrol.

Among the more harmful aspects of vehicle pursuits under Operation Lone Star is the use of “stop devices,” a term used by DPS to describe the use of weapons, spike strips, or special maneuvers to forcibly stop pursued vehicles. Spike strips are strips of tire-puncturing spikes, which quickly deflate the tires of a vehicle that passes over them, predictably leading drivers to lose control of their vehicles, sometimes at high speeds. Since the program began, DPS officers (Texas state troopers) in Operation Lone Star counties have used stop devices in 594 vehicle pursuits, or 17 percent of all pursuits.

For DPS, vehicle pursuits also function as sources of propaganda. The agency has a YouTube channel, as well as multiple Facebook and Twitter pages, where it posts stylized videos of agents pursuing vehicles transporting people believed to be migrants. Reminiscent of the US television series Cops, the DPS video productions are little more than sensationalized “border crisis” stories. Footage of bloody, injured, and dead human beings or damaged property does not appear in the stylized clips.

***

Referring to the people killed in OLS vehicle pursuits, Crystal Martinez, a former journalist, and resident of Texas who covered multiple collisions, told Human Rights Watch in July 2023:

You know, as journalists, we are unbiased. We have to just note what we see, what we have heard from officials, and that's as far as we go. But I guess when we go home, we realize these are people, you know? Someone's mother, someone's daughter, someone's son.

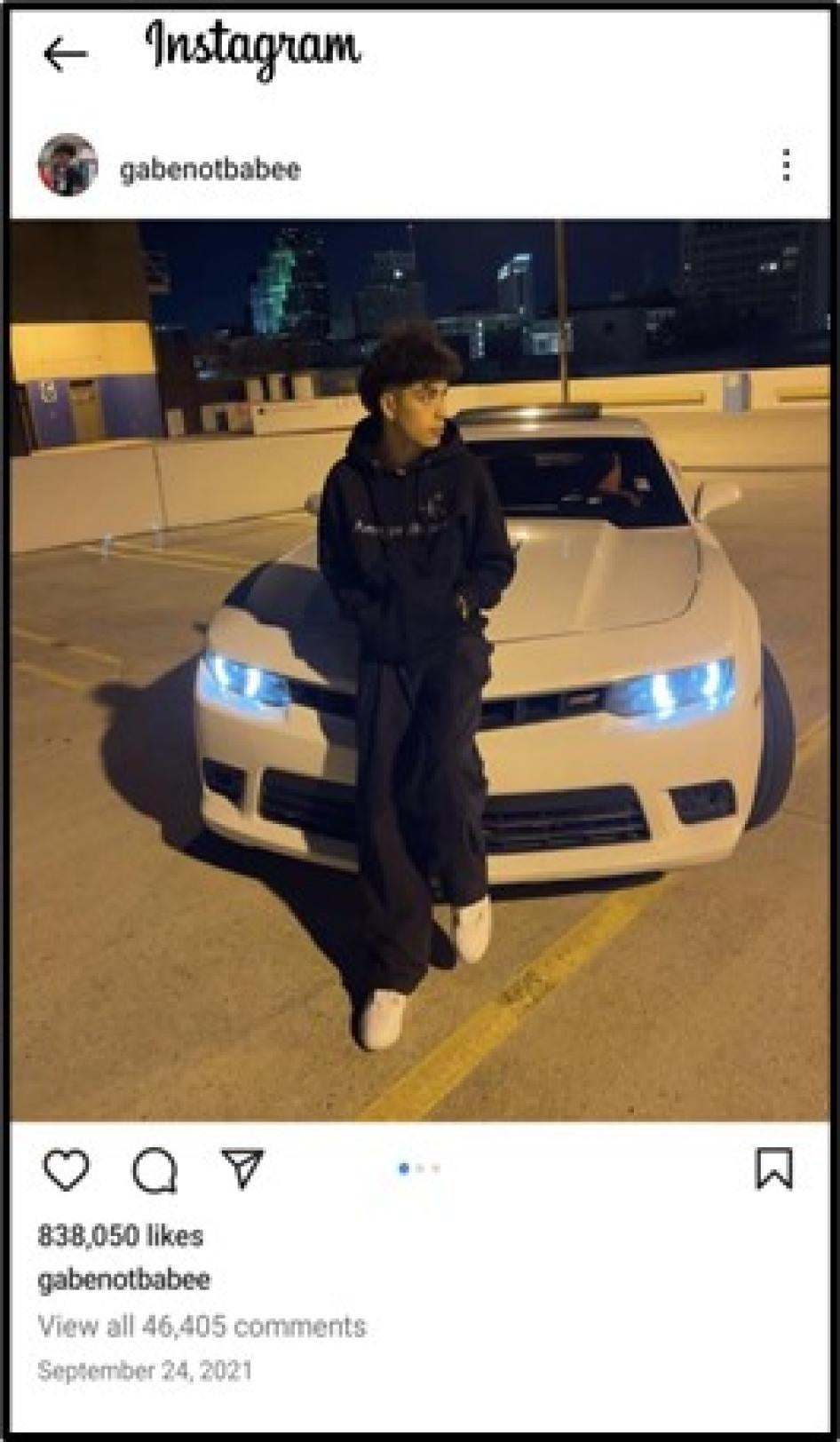

On September 26, 2021, Gabriel Salazar, a 19-year-old from San Antonio with a large Tik Tok following, and three passengers from Mexico died fleeing a law enforcement vehicle pursuit in Zavala County, where just two months prior local officials had joined Operation Lone Star.

The Crystal City Police Department initiated the chase, and the Zavala County Sheriff's Office assisted. A sheriff’s deputy attempted to use a spike strip, but Salazar’s vehicle, damaged by the device, continued out of control, eventually hitting several trees, rolling over, and catching fire.

Salazar and 23-year-old Jose Molina Lara, 36-year-old Sergio Espinoza Flores, and 41-year-old Jose Luis Jimenez Mora were all pronounced dead at the scene.

Central elements of the incident that claimed their lives are common under Operation Lone Star: a young driver recruited on social media to earn needed money; passengers at the mercy of the driver and the overzealous law enforcement agencies bent on capturing them; and a horrific crash resulting in preventable loss of life.

Vehicle pursuits, which are a consequence of Operation Lone Star policies, violate the rights of migrants and Texans alike. Operation Lone Star demonstrates what it looks like to “secure the border” with reckless disregard for human rights.

Recommendations

Law enforcement pursuits of vehicles believed to be transporting migrants are part of a broad set of measures under Operation Lone Star that treat migrants inhumanely and violate other human rights. Key Operation Lone Star policies conflate migrants with dangerous invaders and manipulate state law to punish them severely and in violation of their human rights.

The fact that US government data and studies have shown that migration is not curbed by harsh deterrence policies such as OLS has had no effect on Governor Abbott or other policymakers’ determination to continue these dangerous and deadly policies.

In the short term, very specific policies under Operation Lone Star should be ended. First, DPS and all state and local law enforcement agencies in Texas should end vehicle pursuits when the only basis for the pursuits is a traffic violation and/or the suspected transport of unauthorized migrants. As stated by Houston’s Chief Finner, law enforcement does not “have to give up the search for the suspect when we give up the pursuit.” Second, the US Congress and all federal agencies should cease providing the federal funding that state or local entities use to implement Texas’ Operation Lone Star. Third, all judges and prosecutors involved in criminal prosecutions under Operation Lone Star should exercise prosecutorial discretion to de-prioritize offenses such as trespass, smuggling, or illegal entry. Finally, local jurisdictions should rescind their “disaster” declarations under Operation Lone Star and not seek new appropriations under the program.

To the Biden Administration

- End all collaboration with Operation Lone Star in Texas, including all collaboration between US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and any state and local law enforcement involved in implementing Operation Lone Star.

- End federal funding that state or local entities use to implement Texas’ Operation Lone Star.

- Deploy Department of Justice Civil Rights Division investigators to investigate all aspects of Operation Lone Star for violations of federal law, including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. § 2000d et seq.).

- Ensure that the Department of Justice expeditiously completes all investigations of Operation Lone Star for possible violations of federal law, including federal civil rights statutes.

- Ensure accountability and remedies for any violations exposed through federal investigations.

- Provide a public accounting of the results of federal investigations when possible and appropriate.

To the US Congress

- Provide that funds appropriated for US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) may not be directed toward collaboration between CBP and Texas’ Operation Lone Star.

- Conduct oversight hearings in the Homeland Security Committee on collaboration between CBP and Operation Lone Star, including the involvement of CBP in the enforcement of Texas state criminal law.

To the Department of Justice

- Revise guidance on the use of racial profiling by federal law enforcement to eliminate existing border and national security loopholes and prohibit profiling based on actual or perceived race, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, including gender identity and expression, and English proficiency, and instruct the Department of Homeland Security to issue parallel guidance.

To the Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General

- Investigate every vehicle pursuit in Texas involving intelligence-sharing or vehicle and/or personnel deployments by CBP to determine whether these pursuits adhere to CBP’s existing policies on vehicle pursuits, racial discrimination in law enforcement, and use of force.

To the Texas State Legislature

- Cease all appropriation of funds to Operation Lone Star.

- Pass legislation to ensure that criminal trespass is treated equally no matter where it occurs.

- Pass legislation to establish a new office of Operation Lone Star Redress within the appropriate state agency (such as the Texas Department of Health and Human Services or Department of Public Safety Crime Victims Services) to allow individuals harmed (physically, emotionally, and due to property damage) by Operation Lone Star to file claims and receive financial or other support as redress.

- Until all state funding of Operation Lone Star ends:

- Conduct oversight hearings in public safety committees to investigate the use of vehicle chases in the implementation of Operation Lone Star.

- Conduct oversight hearings in appropriation committees of funds spent on Operation Lone Star and the extent to which OLS has met its stated aims of curbing drug smuggling and unauthorized migration.

- Conduct hearings in judiciary committees investigating racial disparities in OLS policy and practice.

- Conduct hearings in judiciary committees investigating the costs of criminal prosecutions, jailing, court procedures, and imprisonment under Operation Lone Star, as well as OLS compliance with state and federal law.

To Texas Prosecutors

- Until Operation Lone Star is ended, exercise prosecutorial discretion to refrain from prosecuting criminal trespass and migrant smuggling charges in counties that participate in the operation.

- Open investigations into law enforcement vehicle pursuits in Texas which may have violated Texas law and policy.

To Texas Governor Greg Abbott, Texas Counties, Municipalities, and Sheriffs Involved in Operation Lone Star

- Rescind all disaster declarations and executive orders forming the basis for Operation Lone Star.

- End Operation Lone Star.

- Issue and strictly apply directives on vehicle pursuits that include a prohibition on high-speed pursuits in or near populated areas and on all vehicle pursuits of individuals suspected of offenses related to unauthorized migration, including criminal trespass and transport of unauthorized migrants under state or federal law, as well as for other nonviolent offenses.

To Texas National Guard and Texas Department of Public Safety

- End implementation of all rights-violating aspects of Operation Lone Star.

- Until Operation Lone Star is ended, cease all vehicle pursuits of individuals suspected of offenses related to unauthorized migration including criminal trespass and transport of unauthorized migrants under state or federal law.

Methodology

For this report, Human Rights Watch conducted 15 interviews with attorneys, law enforcement personnel, and government officials about Operation Lone Star on background and on the record, as well as 11 with Texas residents who witnessed vehicle pursuits, or experienced property damage from vehicle pursuits under Operation Lone Star. Interviewees were provided the opportunity to provide information anonymously if they wished. No compensation was given to interviewees for providing information.

Human Rights Watch obtained the data analyzed in this report via public records requests filed with city and county police departments; the Texas Department of Public Safety; open-source data derived from internet searches of media reports; and publicly available data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

In February 2023, Human Rights Watch requested public records from police departments in cities and counties participating in Operation Lone Star or otherwise experiencing state trooper deployments under the program. The requests asked for records relating to vehicular pursuits dating back to March 2020. The organization also sent duplicate requests of the records for county sheriff’s offices to county judges.

Table 1. Police Departments To Which HRW Sent Records Requests

|

Police Department |

Provided Responsive Records |

|

Brooks County Sheriff |

No |

|

Del Rio Police Department |

Yes |

|

Eagle Pass Police Department |

Yes |

|

Edinburg Police Department |

Yes |

|

El Paso County Sheriff |

No |

|

Encinal Police Department |

No |

|

Hidalgo County Sheriff |

Yes |

|

Kinney County Sheriff |

No |

|

La Joya Police Department |

No |

|

La Salle County Sheriff |

No |

|

Laredo Police Department |

Yes |

|

Maverick County Sheriff |

No |

|

Mission Police Department |

No |

|

Starr County Sheriff |

No |

|

Val Verde County Sheriff |

Yes |

|

Webb County Sheriff |

No |

|

Zavala County Sheriff |

No |

Of the agencies that received records requests, six provided responsive records with varying levels of detail.[1] The La Salle County Sheriff’s Office attempted to collect a fee of $38,191.34 to produce records[2] and the Kinney County Sheriff’s Office a fee of $2,960.00, both of which Human Rights Watch refused,[3] meaning that these two counties did not release the requested records.

Of the counties that provided information, some departments, like the Val Verde County Sheriff’s Office and Del Rio Police Department provided records containing incident reports, arrest reports, and narrative supplements containing officers’ personal accounts of each incident.[4] Others, like the Eagle Pass and Laredo Police Departments, provided less detailed records, such as incident and arrest reports with no narrative supplements, and a spreadsheet containing limited data for vehicle pursuits associated with certain criminal charges, respectively.[5]

Where records did not contain narrative supplements, there were no officer accounts describing whether pursuits occurred because transportation of migrants or other immigration-related offenses were suspected. In those cases, the only way to glean this information was from the criminal charges listed, and only if an arrest was made.

Data from the city and county police records Human Rights Watch obtained were too limited to allow us to estimate the number of vehicle pursuits by all city and county police departments participating in Operation Lone Star. However, we used information contained in officers’ personal accounts of vehicle pursuits to inform and supplement findings related to racial profiling, pretextual stops, and patterns of recklessness also supported by sources such as DPS and open-source data.

For our statewide analysis, the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) provided Human Rights Watch a spreadsheet containing data on vehicle pursuits involving DPS vehicles occurring between March 1, 2020 and March 22, 2023 (Dataset 1); a spreadsheet containing data on DPS vehicle pursuits that occurred between March 1, 2020 and April 19, 2023, including pursuits that involved use of force incidents (Dataset 2); as well as a spreadsheet containing use of force incidents that led to injury or harm from a DPS officer from March 1, 2020 to April 16, 2023 (Dataset 3).[6]

Analysis of DPS vehicle pursuits in this report primarily relies on Datasets 2 and 3, with the exception of a handful of data categories that were only included in Dataset 1. The data we analyzed covered pursuits in the 56 Texas counties implementing Operation Lone Star as of April 19, 2023, the day for which DPS data was available. The data also covered pursuits in four counties that were not implementing Operation Lone Star as of April 19, 2023, but were nonetheless subject to DPS officer deployments under OLS.[7]

The Department of Public Safety does not track when a vehicle pursuit is related to the transportation of migrants or other immigration-related offenses and does not track the citizenship status of vehicle occupants. The agency does track when a traffic stop is related to transportation of migrants, but DPS told Human Rights Watch that it is not able to specify when attempted traffic stops lead to vehicle pursuits.[8] The Department of Public Safety also does not track fatalities resulting from vehicle pursuits unless they are the direct result of an officer’s use of force.

Where this report compares aggregate DPS data on vehicle pursuits across the state with aggregate DPS data on vehicle pursuits in Operation Lone Star counties to measure the impact of Operation Lone Star, figures are calculated using data for all DPS pursuits for which the agency provided records rather than solely pursuits related to transportation of migrants because the agency told us it did not track such data.[9]

However, Operation Lone Star has resulted in increases of DPS trooper deployments in Operation Lone Star counties, which has in turn led to measurable increases in vehicle pursuits. We have reviewed press accounts and law enforcement incident reports to confirm that vehicle pursuits involving DPS often also involve other law enforcement agencies. Press accounts and law enforcement incident reports also confirm that although DPS does not record whether the vehicle pursued was suspected of transporting migrants, that is often the reason for the pursuit in Operation Lone Star counties.

Some information analyzed by Human Rights Watch for this report was obtained through open-source data derived from internet searches of media reports as well as the Missing Migrants Project established by the International Organization for Migration (IOM). When this report describes injuries and deaths resulting from vehicle pursuits specifically related to migrants, Human Rights Watch cross-checked DPS data sources or IOM data sources with media accounts that reported the vehicle pursued contained one or more migrants.

To identify directly affected individuals, Human Rights Watch also used open-source data to identify several incidents in the Rio Grande Valley region. Researchers then visited crash sites and spoke to nearby residents and business owners, some of whom were witnesses to the crashes or were affected by them in some way. Human Rights Watch relied on partner organizations to identify residents in Webb County who experienced the impact of vehicle pursuits in their communities and reached out to them directly. We also relied on media reports to identify individuals associated with several pursuits throughout the region and reached out to them directly. Finally, we wrote to the law enforcement agencies involved in all the vehicle pursuits described in some detail in this report to request their comment. We received one response from the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office providing us with their vehicle pursuit policy.

Background

In March 2021, Texas Governor Greg Abbott launched Operation Lone Star (OLS). OLS’s stated objectives were “to combat the smuggling of people and drugs into Texas” and to “deter illegal border crossings.”[10] In May of that year, the governor issued a proclamation invoking the Texas Disaster Act of 1975 and declaring that people’s attempts to migrate by crossing the Texas-Mexico border constituted a “disaster.”[11] The proclamation gave the governor and the Texas counties included in the declaration the authority to access state and local resources to manage the purported disaster, activated the Texas Division of Emergency Management (TDEM) to respond, and increased criminal penalties in the “disaster” area for certain criminal offenses, including criminal trespass.[12]

Since its inception, Operation Lone Star has used billions of dollars to fund the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) and the Texas National Guard to patrol the border, provided grants to local law enforcement agencies – often municipal police and county sheriffs—to participate in OLS, opened TDEM-run processing centers to book and detain those arrested in border areas, and repurposed state prisons from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) to use for the jailing and imprisonment of people arrested, prosecuted, and convicted of (or who plead guilty to) new migration-related offenses under Texas law.[13] The law enforcement agencies involved include DPS, the Texas National Guard, municipal police departments (for example, the Edinburg Police Department), county sheriffs (for example, the Kinney County Sheriff’s Office)—all of which implement OLS; and the US Border Patrol, which works alongside and often coordinates with these other law enforcement agencies.

“Invasion” Rhetoric and Border Deployments

From the outset, Operation Lone Star has been fueled by false and dangerous rhetoric referring to people seeking to migrate across the Texas-Mexico border as an “invasion.”[14] Propagated by Governor Abbott and other state and local officials, this rhetoric depicts migrants — many of whom are asylum seekers — as threats and sources of drugs, crime, and violence that have to be stopped at all costs.[15] Operation Lone Star and its costs were justified by local and state officials “based on fears that a swell of drug cartel operatives, gang members or rapists are crossing the border into Texas.”[16]

According to the Office of the Governor, Operation Lone Star “integrates DPS with the Texas National Guard and deploys air, ground, marine, and tactical border security assets” to the border to “combat the smuggling of people and drugs into Texas.”[17]

At deployment levels of up to 10,000 troops, OLS represents the “biggest deployment of Texas National Guard members to the border in size and duration.”[18]

In terms of DPS officer presence, in August 2021, the Office of the Governor reported to the state legislature that 1,250 officers had been sent to the border.[19] In March 2022, a year into the mission, reports indicated a sustained deployment of 1,000 officers, which is about 35 percent of the total Texas state police force.[20] Fourteen additional states—Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Idaho, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming—“deployed personnel and resources” to Texas to assist with Operation Lone Star. Most such deployments were relatively modest, such as Iowa’s deployment of 100 national guard members.[21] The largest deployment was Florida’s—of just over 1,000 personnel.[22]

A detailed analysis in March 2022 by the Texas Tribune pointed out that data the governor cites as evidence that OLS is having the desired impact involve statewide drug seizures and not just those tied to OLS, nor is there evidence that cartels have been destabilized by OLS.[23] Governor Abbott cited curbing “illegal border crossings” as a primary justification for OLS; [24] but US government data and studies show that migration is not curbed by harsh deterrence policies, specifically including OLS.[25] In July 2023, the Wall Street Journal reported that Operation Lone Star’s “efficacy is also under question,” stating that:

The area of the border most heavily targeted by Operation Lone Star has seen the most rapid increases in illegal border crossings in the state since the operation began. Thousands of arrests by state troopers under the program have been unrelated to border security, and instead netted U.S. citizens hundreds of miles from the border. Arrests of migrants trespassing on private property have generally not affected their immigration cases, and courts have found many of the arrests made in the first two years to be discriminatory and invalidated them. Despite the flood of resources, the added arrests by Operation Lone Star personnel in that section of the border amount to about 1% of the encounters there by Border Patrol in the same time frame, or about 11,000 added to the Border Patrol’s 850,000.[26]

As of October 2022, at least 10 Texas National Guard service personnel have died while deployed under Operation Lone Star. These deaths have included five deaths attributed to suicide, one to drowning while attempting to rescue migrants, two to accidental shootings, one to a motorcycle accident, and one to a blood clot that a servicemember developed while deployed during a heat wave.[27] Additionally, Anthony Salas, a Texas Department of Public Safety special agent, died while riding on a truck deployed during a nighttime operation.[28]

Arrests on State Criminal Charges

Under Operation Lone Star, state troopers and participating local law enforcement agencies arrest people who are typically charged with state misdemeanor criminal trespass or state felony smuggling charges. Texas National Guard members are tasked with aiding in these arrests.[29]

Under Texas law, people may be prosecuted for smuggling of persons under Texas Penal Code section 20.05, which is usually charged as a third-degree felony, and continuous smuggling of persons under Texas Penal Code section 20.06, which entails smuggling of persons two or more times in a ten-day period and is generally a second-degree felony. Neither crime currently carries a mandatory minimum sentence. An analysis by the ACLU of Texas found the average length of imprisonment for these offenses under current law was approximately 1 year.[30]

Migrants are also charged with criminal trespass, which is a class B misdemeanor and occurs when a “person enters or remains on or in property of another, including residential land, agricultural land, a recreational vehicle park…without effective consent.”[31] At trial, if it is shown that the trespass occurred in a part of Texas under a “disaster” declaration (such as those promulgated under Operation Lone Star), then the punishment may be enhanced upon conviction to a mandatory minimum sentence of 180 days.[32] In practice, thousands of migrants are being prosecuted for criminal trespass and facing enhanced sentencing because they are blocked from entering public land and instead funneled towards private property.[33]

As of November 2023, the Texas legislature had passed a bill to create a new crime of illegal entry into Texas from a foreign nation, and a new crime of refusing to be deported.[34] The legislature had also passed a bill to impose a mandatory minimum sentence of 10 years upon conviction for human smuggling.[35]

In July 2021, the state took on a new strategy to deter border crossings when state troopers in two border counties, Val Verde and Kinney, began arresting men, other than those travelling with family members, who were suspected of crossing into Texas between “ports of entry” (an official place where goods and people may enter the US) and charging them with state crimes, including trespassing on private property.[36] Texas officials referred to this program as a state “catch and jail” program, in contrast to what they described as a federal “catch and release” policy.[37]

The “catch and jail” program has criminalized people whose only unlawful act is crossing the border without authorization.

The fact that unauthorized migration and criminal trespass are nonviolent offenses has not factored into the harsh punishment scheme, nor has there been any reliable analysis of the criminal records of individuals attempting to enter the United States. While open-source media searches reveal isolated incidents, such as one reported by Fox News on August 3, 2023, in which individuals alleged to have “suspected ties” to cartels were apprehended at or near the border,[38] the vast majority of migrants arriving to the Texas-Mexico border are seeking safety, family reunification, or simply a dignified life.

Among the 2.9 million apprehensions of people attempting to cross the entire US southwest border recorded by CBP in FY 2022 (not solely the Texas-Mexico border), CBP identified 29,000 individuals with outstanding warrants, previous criminal records (including improper entry and re-entry crimes), or who were wanted by law enforcement agencies.[39] The millions of apprehensions, only 1 percent of which involved individuals with any kind of criminal record (including nonviolent records),[40] casts doubt on Kinney County Sheriff Brad Coe’s statement to the Texas Tribune that “migrants committing more serious crimes often aren’t caught” and therefore the criminal trespass arrests were a justified response.[41]

By February 2022, arrests for trespassing became the majority of arrests made under Operation Lone Star.[42] By April 2022, almost all of the trespassing charges under the catch and jail program came from Kinney and Val Verde Counties.[43] In September 2022, press reports cited 398 criminal trespassing charges in Maverick County.[44] An analysis of Texas’ Public Safety Report System by the Vera Institute of Justice found that there were 5,164 people charged with smuggling and continuous smuggling between April 2022 and March 2023.[45]

Separate and Unequal Criminal Legal System

Operation Lone Star establishes a separate criminal legal system to arrest, detain, and prosecute migrants.[46] The Texas Division of Emergency Management set up two processing tents in Val Verde and Jim Hogg Counties where migrants are processed and detained after arrest.[47] These soft-sided facilities dramatically expanded detention capacity for individuals arrested for trespassing, smuggling, and other border-related offenses under Operation Lone Star. In many cases, the length of pretrial detention can stretch from weeks to several months.[48] The vehicle pursuits described in this report are intended to feed this separate criminal legal system.

Once booked, individuals arrested are sent to one of two state prisons that were emptied, with previous inhabitants moved to more crowded facilities further from their home counties, and repurposed to jail people arrested under OLS: the Briscoe Unit in Dilley and the Segovia Unit in Edinburg.[49]

The criminal legal system created to facilitate Operation Lone Star also includes separate court dockets overseen by a rotating list of retired judges assigned by the Texas Supreme Court to conduct magistration and set bail via virtual hearings, primarily held over the video conferencing internet platform Zoom.[50] Magistration in Texas (known outside of Texas as “arraignment”) is the stage at which defendants in criminal cases first appear in court after their arrest. The presiding judge informs them of the charges against them, reviews the charges and determines whether there is probable cause for their arrest and detention, and sets bond, which a person must pay to be released from custody.

Individuals charged with smuggling under current Texas law are almost always detained due to very high bond amounts that defendants cannot pay. For example, Human Rights Watch researchers witnessed a magistration in Texas in which people charged with smuggling had bond set at US $10,000 to $20,000 or higher.[51] Defense attorney Kristen Etter confirmed to Human Rights Watch, “Bond for these cases is regularly set at $8,000 and they are consecutive, meaning they are often much higher. This is well beyond most defendants’ ability to pay.”[52]

As an example, an individual arrested for criminal trespass near Val Verde County will be processed in a tent facility, have their bail set during video hearings by a judge located in another region of the state, then transported to a converted Texas prison for OLS pretrial detention. Cases can take weeks and months to be prosecuted and heard. Delays in charging individuals, assigning counsel, and scheduling hearings have resulted in people being jailed for weeks or months and ultimately being sentenced to time served.[53] After their release, many are transferred to federal immigration custody only to be deported.[54]

This separate system of criminal law enforcement treats people assumed or suspected of being migrants, or suspected of transporting migrants, located in Operation Lone Star counties, differently from people not so assumed, suspected, or located. A person suspected of criminal trespass in Houston, for example, will be subjected to different vehicle pursuit polices, different lengths of pretrial detention, different bond amounts, and different sentencing enhancements than a person assumed to be a migrant or suspected of criminal trespass in an Operation Lone Star county.[55] A person suspected of smuggling in Houston is likely to be subjected to different vehicle pursuit policies, and less likely to be subjected to pretextual stops than a person suspected of smuggling in an OLS county. Moreover, racial discrimination and the use of pretextual traffic stops in OLS counties mean that a white person is likely to be treated very differently in OLS’ criminal system from a Black, Indigenous, or Latinx person.

In July 2023, the Office of the Governor reported that under Operation Lone Star there had been over 394,200 migrant apprehensions and 31,300 criminal arrests.[56] The governor did not provide any data to substantiate these claims or determine which agencies were responsible for which apprehensions or arrests or whether these arrests or apprehensions are specifically related to Operation Lone Star or have simply occurred during the time frame of OLS. The data provides no information about how many of these arrests came after vehicle pursuits.

In August 2023, under a new state directive, Texas state troopers started separating families by detaining fathers on trespassing charges and transferring other family members, including children, to Border Patrol agents to be processed in separate facilities.[57]

Border Walls and Other Barriers

The construction of a state border wall between 18 and 30 feet high is another aspect of Operation Lone Star. With funding from the state legislature, the Texas Facilities Commission has awarded $841 million in contracts to build 37 miles of walls.[58] Governor Abbott has said he plans to build over 800 miles of walls along the 1,254-mile Texas portion of the US-Mexico border.[59] At a legislative hearing in July 2022, State Senator Juan Hinojosa observed that building at the current pace and cost per mile, it would take 34 years and $17 billion to complete the wall.[60]

Along with walls, other types of barriers like shipping containers and razor wire have been installed on the banks of the Rio Grande in Eagle Pass under a policy referred to as Operation Steel Curtain.[61] According to DPS, the shipping containers and razor wire are intended “to block and repel criminal activity and stop violations of state law,” language which again conflates migrants, including those seeking protection, with criminals.[62] According to DPS, there are about 90 miles of razor wire and about 100 shipping containers, each 20 to 40 feet long, placed along the border in and around Eagle Pass.[63] In July 2023, a state trooper’s email to his superiors that was made public revealed the razor wire had caused lacerations to migrants attempting to cross the river and had trapped a pregnant woman who then had a miscarriage.[64]

In June 2023, the governor announced the deployment of a floating barrier directly in the waters of the Rio Grande. It consists of buoys equipped with saw-edged circular metal plates between them and underwater netting, and is designed to rotate to keep people from scaling the barrier.[65] At the announcement, Abbott said the buoys would prevent people from reaching the border.[66] The first 1,000 feet of the buoys were deployed in Eagle Pass in July 2023 at a cost of $1 million.[67] Weeks later, the bodies of two unidentified individuals who drowned were found near the buoys.[68] In August 2023, Human Rights Watch witnessed abuses occurring at Eagle Pass due to the buoys and razor wire, including babies who had been trapped under the razor wire being denied drinking water and a toddler who was at risk of drowning.[69] On September 6, 2023, a federal judge granted a US Department of Justice request for an injunction and ordered Texas to remove the 1,000 feet of buoys in the Rio Grande across from Eagle Pass by September 15. Texas immediately filed an appeal,[70] and the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit stayed the injunction, allowing the buoys to remain while the appeal goes forward.[71]

Cost

Operation Lone Star has cost Texas taxpayers close to $10 billion in spent or allocated funds. Texas spent $4.4 billion in OLS’ first two years: though the state legislature initially appropriated about $3 billion dollars for the initiative, funds were quickly spent as Governor Abbott increased Operation Lone Star deployments to 10,000 troops, requiring emergency cash infusions of another $1.4 billion to keep the effort afloat over a period of approximately nine additional months, until June 2023.[72]

In May 2023, the Texas legislature allocated another $5.1 billion for the next two years of the program, resulting in biennium expenditures nearly 10 times what Texas spent on border enforcement just a decade ago.[73]

Yet another element of the Governor’s efforts is the busing of migrants from border cities to other parts of the country at the expense of Texas taxpayers. In July 2023, the Office of the Governor reported that the state had bused over 27,260 migrants to Washington, New York City, Chicago, and other cities.[74] A report from May 2023 put the cost at $26 million, though at the time the estimate was based on the busing of 13,200 people.[75]

Val Verde and Kinney Counties have paid for the costs to process criminal cases with grants provided by the Office of the Governor.[76] To receive the funds, counties must have issued local disaster declarations and agreed to formally collaborate with state officials, including DPS and the Texas National Guard, on arrests and prosecutions of migrants. The first round of awards in October 2021 totaled more than $36 million in funding to “assist local law enforcement, prosecutors, jail administrators, medical examiners, and court administration officials in the execution of coordinated border security operations.”[77]

These grants serve as incentives to participate in the border enforcement scheme, as counties can use the funding to increase the capacity and infrastructure of their criminal legal systems, often a talking point for officials running for local election.[78]

People Harmed by Operation Lone Star Vehicle Pursuits

Texans and Migrants Killed and Injured

In border towns across Texas, Operation Lone Star’s high-speed pursuits and the crashes they cause are a threat to people’s safety, with harmful consequences for migrants and residents alike.

In a vehicle pursuit on November 13, 2021, a DPS trooper in Laredo, Texas, attempted to pull over a Nissan Murano for an unspecified traffic violation.[79] When the vehicle did not yield, the trooper chased after it.

The driver, 23-year-old Abraham Ahumada, ran a red light at an intersection and struck another vehicle. The Nissan caught fire, and two of its occupants, brothers from Honduras, died at the scene. Armando Lorenzo Rodriguez, 45, was ejected from the vehicle, and Valdemar Lorenzo Rodriguez, 30, was killed on impact and burned in the fire before his body could be removed from the vehicle. An unidentified third passenger was taken to a local hospital in critical condition.

The driver of the vehicle struck by the Nissan also died at the scene. Her name was Alejandra Torres Flores: a 62-year-old resident of Laredo, Texas. Four other passengers riding with her, three of whom were youths, suffered non-life-threatening injuries.

Another incident occurred on March 13, 2023. It began when a truck, driven by 22-year-old Rassian Comer of Louisiana, was clocked for speeding and law enforcement attempted to stop the truck.[80] When Comer did not comply with the attempted stop, a Crockett County Sheriff's deputy pursued the truck, which exited the highway, ran a red light, and collided with another vehicle, killing four people.[81] Among the dead were two men from Mexico, a 45-year-old and 42-year-old whose names were not publicly identified.

Killed on impact were 71-year-old Maria Tambunga and her 7-year-old granddaughter Emilia Tambunga, who were South Texans going out for ice cream when the pursued vehicle rammed into them. Comer was taken to a local hospital in critical condition. [82]

In a third incident, on December 11, 2021, DPS officers in Texas assisted in a chase initiated by Border Patrol, who pursued a vehicle driven by 18-year-old Esteban Cantu Jr. that was occupied by six migrant passengers.[83] The pursued vehicle ran a stop sign and collided with a car not involved in the chase, killing its occupants Carmen Huerta Sosa, 59, and her 22-year-old daughter, Viridiana Charon Lloyd – both of whom were residents of Texas, and sending Cantu and his six passengers to the hospital with injuries.

Arturo Fonseca, a nearby Texas resident who witnessed the aftermath of the pursuit, told Human Rights Watch, “They [referring to DPS] are causing the deaths of innocent people.”[84]

Fonseca noted that he has seen an increase in vehicle pursuits and said they are now a near-daily occurrence in his Texas neighborhood. When Human Rights Watch asked what his concerns were, he said, “It presents a danger for us. We are driving in the area daily, so it presents a risk to us.” [85]

On December 3, 2021, Border Patrol agents in the South Texas county of Starr attempted a traffic stop after they spotted people exiting a Ford F-150 pick-up truck and suspected they were migrants.[86] When the driver failed to yield, agents in two separate vehicles initiated a pursuit. Border Patrol Sector Communications notified DPS and a trooper accompanied by two additional Border Patrol agents arrived at the scene.[87] A media report indicated Border Patrol and DPS were working together as part of Operation Lone Star, which they characterized as a “joint operation among law enforcement who patrol the border.”[88]

As the vehicle was approaching a residential area, the DPS trooper deployed a vehicle immobilization device (VID), more commonly known as a spike strip. According to a Customs and Border Protection press release, “the F-150 attempted to circumvent the VID, left the roadway, struck solar panels, rolled, and came to rest on its side.”[89]

A 48-year-old male passenger from Mexico, Faustino Cabrera Cardoso, was ejected from the vehicle and died at the scene.[90] According to a police report shared with Human Rights Watch, the driver was 17 years old.[91] He was arrested on charges of murder and evading arrest resulting in death.[92]

The property the vehicle crashed into was the home of Dilia Villarreal, a schoolteacher and lifelong Texas resident who that morning had just left for work.

A former police chief in an Operation Lone Star county told Human Rights Watch:

From my perspective as a former police chief, no life is worth risking if all you have is undocumented people in the car. Is it a crime? Yes, we get all that. But we also have to be smart and use good judgment when it comes to risking people’s lives. Innocent people are killed at times.[93]

Texans Suffer Property Damage

The December 3, 2021 Starr county vehicle chase that resulted in the death of 48-year-old Faustino Cabrera Cardoso, also damaged the property of Dilia Villarreal. The incident resulted in $71,000 worth of damage to her fence and a solar panel system she had recently installed. More than a year later, still struggling with the toll the incident took on her physical and mental health, Villarreal, a schoolteacher and lifetime Texas resident who has not been compensated for her property damage, told Human Rights Watch, “It’s been very depressing for me. It’s like somebody crashing their vehicle into your house and they just say ‘sorry’ and go on their merry way.”[94]

Though she expressed anger at the 17-year-old driver and the migrants he was transporting, the most indifferent responsible parties, in Villarreal’s mind, were the Border Patrol agents that initiated the pursuit and the DPS agent that laid the spike strip. “Everything was very recklessly done, and I think the government should have come forward and paid me for all this damage because they caused it,” she said.[95]

A longtime neighbor of Villarreal who witnessed the event, Brenda Garza, shared with Human Rights Watch that after the crash, the driver fled from the scene and into her property.[96] A Border Patrol agent pursued him on foot, jumping over her fence to chase him down. Garza tried to stop the 17-year-old and grabbed a piece of his shirt, but he slipped away, she said.

When asked if at that moment she felt fear of the driver, Garza responded,

I’m not afraid. What I was worried about was that the [school] bus had just passed. Sometimes I have my grandkids with me, and they pick them up here […] Thank God that the bus had already picked up the kids. They missed them by seconds. By seconds.[97]

Young People Often Harmed

Human Rights Watch analyzed publicly available data[98] of people arrested on smuggling charges and booked into Operation Lone Star processing centers in Val Verde County and Jim Hogg County between June 2021 and July 2023. Nearly 80 percent of the 5,164 people booked for smuggling during this time frame were US citizens with a median age of 26.[99] Nearly 13 percent—more than 650 of them—were ages 18 or 19. In a review of media reports, Human Rights Watch identified at least 12 youth between the ages of 14 and 17 charged with smuggling under Texas law between August 2021 and March 2023 as a result of Operation Lone Star.[100]

As described in the summary of this report, on September 26, 2021, a 19-year-old from San Antonio with a large social media following, Gabriel Salazar, and three passengers from Mexico died fleeing a law enforcement vehicle pursuit in Zavala County. Local officials in the county had decided to participate in Operation Lone Star just two months prior.[101]

The Crystal City Police Department initiated the chase, and the Zavala County Sheriff’s Office assisted. A local Sheriff’s deputy attempted to use a stop device, but Salazar’s vehicle continued, eventually hitting several trees, rolling over, and catching on fire.

Salazar and 23-year-old Jose Molina Lara, 36-year-old Sergio Espinoza Flores, and 41-year-old Jose Luis Jimenez Mora were all pronounced dead at the scene.

The circumstances that claimed their lives are common under Operation Lone Star: young drivers recruited on social media to earn extra money; passengers at the mercy of the driver and pursuing law enforcement; overzealous police agencies bent on capturing them; and horrific crashes resulting in preventable loss of life.

Another case, described at the start of this report, occurred on August 26, 2021, when Texas state troopers encountered 19-year-old Ruben Villegas while patrolling a highway leading from the Texas-Mexico border.[102] According to local reports, DPS troopers spotted Villegas’ 2012 silver Chevrolet Malibu stopped at a rest area and saw five men leave the vehicle and run into the brush.[103] They suspected Villegas of transporting migrants and attempted to conduct a traffic stop. Villegas reportedly sped away and fled with his headlights turned off.

DPS records obtained by Human Rights Watch for this report show that the pursuit occurred at night, involved a helicopter, and traversed what DPS records indicate were “20.1+” miles. DPS vehicles involved in the pursuit reached a maximum speed of 120 miles per hour.[104] DPS chased Villegas because they suspected him of transporting unauthorized migrants, which may be a legitimate reason to attempt to stop a driver but not a reason to engage in a dangerous high-speed chase. Had they called off the pursuit, law enforcement had options to attempt to apprehend Villegas, including his license plate information and visual tracking via helicopter.

During the pursuit, Villegas lost control of the vehicle, striking a bar ditch and then a fence and tree as he crashed into property off US Highway 281. Norma Saldaña sustained significant damage to her private property when Villegas’ vehicle crashed into her fence.

Upon inspection, troopers found three men in the trunk of the car with injuries. Villegas, who suffered grave injuries, was arrested at the scene, and he, along with the other occupants, were transported to a local hospital.

Ruben Villegas succumbed to his injuries a week later.[105] According to local reports, a news release from DPS stated that had Villegas survived the crash, he would have been charged with human smuggling and evading arrest with a vehicle once he was discharged from the hospital.[106]

Dilia Villarreal, now retired, drew on her experience working with high school age kids to help her understand why youth, like the 17-year-old driver who crashed into her property, would help transport undocumented individuals and flee from law enforcement. “The 17-year-olds, they’re not thinking straight,” she said. “I tell them, if you get hurt, you could die. But they're not thinking of what's going to happen to them. These kids don’t understand what the crime [they’re committing] is.”[107]

Indeed, DPS has itself acknowledged the high incidence of young people driving many of the vehicles they pursue, and the role of social media in luring them in.[108] DPS has acknowledged that smuggling networks target youth using deceptive recruiting methods depicting jobs that teens do not understand can constitute crimes.[109]

“These young kids are being exploited…but they don't understand all the problems they are causing,” said Villarreal.[110]

Defense attorneys confirm that those charged under the smuggling statute are overwhelmingly young Texans who are recruited through social media platforms to drive people from border communities to other localities in Texas.

“People will tell us ‘The governor is busing migrants from the border to other cities — how is what I am doing any different?’” said Kristin Etter, attorney for Texas Rio Grande Legal Aid.[111] “These are overwhelmingly young people — college and high school aged. I have a client who is a 9th grader. I also have a client who was accused of smuggling for driving his uncle in a car.”[112]

Maximiliano Zapata, a resident of El Cenizo, Texas who works with youth explained why the children in his rural border town are drawn to these transportation jobs:

Communities like El Cenizo and Rio Bravo, they’re poverty-ridden communities. The average household income is probably less than $20,000 a year. So these kids, they're making a lot of money doing these things […] And then if someone like me comes along and tells them not to do it, then when their families are not able to make ends meet, when they're struggling to pay bills, when they're struggling to pay the property tax […] I mean, they're not going to listen to me. So, I think the root of the issue is poverty. Poverty exceeds fear. There is so much necessity that they can't even think about the consequences.[113]

Data on Operation Lone Star Vehicle Pursuits

Total Deaths and Injuries

Human Rights Watch’s review of DPS records obtained through public records requests, media reports, and data from the International Organization for Migration indicates that between March 2021 (when Operation Lone Star began) and July 2023, at least 74 people were killed and another 189 injured as the result of 49 pursuits by law enforcement in the 60 Operation Lone Star counties in which the vehicles pursued were reported by media as containing migrants.[114] That is a rate of nearly 3 deaths and 7 injuries per month while Operation Lone Star has been in existence. A previous analysis by the ACLU found that 30 people had been killed (a rate of nearly 2 people killed per month) in pursuits of vehicles reported by media as containing migrants during the 17 months between March 2021 and July 2022.[115] Human Rights Watch’s new analysis suggests that the average number of monthly fatalities from these pursuits is at least 45 percent higher than the previous analysis.

In 46 of those 49 incidents, the pursuit ended in a collision that resulted in fatalities and injuries. In two additional instances, occupants fled on foot after the vehicle came to a stop and died or were injured falling from bridges when trying to escape. In one additional instance, a vehicle occupant fled on foot after the vehicle stopped and was fatally struck by oncoming traffic.

Table 2 indicates how many bystanders, passengers, drivers, and officers have been killed and injured because of the 49 pursuits of vehicles reported by media as containing migrants. Bystanders killed and injured are individuals who were riding in vehicles uninvolved in the pursuit who were struck by the pursued vehicle or were otherwise involved in a collision resulting from the pursuit.

Among the bystanders killed was a 7-year-old girl, and among bystanders injured were five young people of an unknown age – all of them Texas residents.

Table 2. Individuals Killed or Injured as a Result of Pursuits of Vehicles Reported by Media as Containing Migrants in Operation Lone Star Counties from March 2021 to July 2023

|

Bystander |

Passenger |

Driver |

Officer |

Total |

|

|

Killed |

7 |

58 |

9 |

0 |

74 |

|

Injured |

10 |

161 |

17 |

1 |

189 |

|

Source: See footnote 113 |

|||||

The data also suggests that Operation Lone Star vehicle pursuits result in a higher rate of death than most high-speed pursuits. A nationwide study by USA Today examining federal data on law enforcement pursuits between 1979 and 2013 found around 328 people killed annually in all 50 of the United States because of law enforcement vehicle pursuits, approximately 1 per 820,000 people living in the country.[116] By comparison, in the 60 Operation Lone Star counties (13 percent of the population in Texas) at least 36 people were killed annually because of law enforcement vehicle pursuits. With these counties comprising approximately 4 million people, this equates to a rate of 1 per 112,000 people. This means that the minimum rate of death from vehicle pursuits in OLS counties has been over 7 times higher than the typical national rate.

As described in the methodology section, Human Rights Watch also analyzed DPS data on all vehicle pursuits across Texas. DPS did not record in its data whether these pursuits involved migrants, but our analysis focused on the 60 Texas counties where Operation Lone Star is focused on apprehending migrants. Of the 5,230 total vehicle pursuits that DPS troopers engaged in across Texas’ 254 counties since March 2021, 3,558 of them, or roughly 68 percent of all pursuits, occurred in the 60 Operation Lone Star counties that represent 13 percent of the state’s population. This means Operation Lone Star county residents are experiencing a disproportionate share of vehicle pursuits across the state.

Since OLS began in March 2021, Operation Lone Star counties have experienced a disproportionate share of all collisions: 51 percent of all crashes in Texas resulting from DPS vehicle pursuits have occurred in Operation Lone Star counties, which, as noted, comprise just 13 percent of Texas’ population.

Since OLS began in March 2021, Operation Lone Star counties have also experienced an increasingly disproportionate share of all pursuits causing injuries: 166 DPS pursuits in Operation Lone Star counties caused injuries (comprising 53 percent of all DPS vehicle pursuits causing injuries statewide compared with 40 percent prior to the program).

Table 3 indicates the number of DPS vehicle pursuits that resulted in injuries between March 1, 2021, and April 2023, as well as the number of individuals harmed. Due to the way the agency tracks this information, vehicle pursuits across categories of parties injured are not mutually exclusive. That is, a unique pursuit could have resulted in an injury to both the driver of the pursued vehicle and its passengers, for example, and that pursuit would be represented in both categories. In Operation Loan Star counties, the average number of unique pursuits with an injury per month has increased 37 percent since the start of the program.[117]

Table 3. DPS Vehicle Pursuits in Texas Resulting in Injuries from March 2021 to April 2023

|

Parties Injured |

All Counties |

OLS Counties |

OLS Counties' Share of Total |

|

Driver of Pursued Vehicle |

262 |

138 |

53% |

|

Passenger(s) of Pursued Vehicle |

97 |

73 |

75% |

|

Bystander(s) |

82 |

47 |

57% |

|

Law Enforcement Officer(s) |

22 |

7 |

32% |

|

Total Unique Pursuits |

315 |

166 |

53% |

|

Source: see footnote 6. |

|||

Vehicle Pursuits Have Increased

Based on the limited local police department records reviewed by Human Rights Watch, it was not possible to determine the overall number of vehicle pursuits carried out by local law enforcement in Operation Lone Star counties. However, the records provided to us by DPS allow for an analysis of vehicle pursuits carried out by DPS state troopers, including those that also involved participation from local police.

Operation Lone Star has led to an overall increase in vehicle pursuits across Texas. Whereas an average of 140 pursuits per month were conducted by DPS across the state in the year prior to OLS, an average of 201 per month took place in the roughly two years after it began.[118] In Operation Lone Star counties, the average number of monthly pursuits has increased by 113 percent. Table 4 lists the incidence of DPS vehicle pursuits in the 15 Operation Lone Star counties with the most pursuits between March 2020 and April 2023 – covering one year before the initiative began (March 2020 to February 2021) and just over two years since its launch (March 2021 to April 2023).

To take one example, from March 2020 through February 2021, Kinney County experienced 22 vehicle pursuits by state troopers. After Operation Lone Star launched, that number shot up to 227 pursuits from March 2021 to April 2023, or an average of two per month before Operation Lone Star compared with nine per month since the program began.

Table 4. DPS Vehicle Pursuits in Operation Lone Star Counties from March 2020 to April 2023

|

County |

Before OLS (12 mo) |

During OLS (26 mo) |

Percent change in monthly average |

|

Willacy |

2 |

71 |

1538% |

|

Zavala |

7 |

184 |

1113% |

|

Brooks |

6 |

155 |

1092% |

|

Uvalde |

9 |

190 |

874% |

|

Maverick |

10 |

166 |

666% |

|

Val Verde |

9 |

109 |

459% |

|

Kinney |

22 |

227 |

376% |

|

Dimmit |

29 |

237 |

277% |

|

LaSalle |

17 |

122 |

231% |

|

El Paso |

49 |

175 |

65% |

|

Jim Wells |

22 |

77 |

62% |

|

Webb |

110 |

296 |

24% |

|

Hidalgo |

177 |

473 |

23% |

|

Starr |

61 |

153 |

16% |

|

Cameron |

55 |

128 |

7% |

|

Total for all OLS Counties |

768 |

3558 |

113% |

|

Source: See footnote 6 |

|||

The justification for these pursuits cited by law enforcement is overwhelmingly traffic violations, misdemeanors such as speeding or failing to obey traffic signals. According to DPS records obtained by Human Rights Watch under state public records laws, 81 percent of the vehicle pursuits that occurred in Operation Lone Star counties were initiated because of a traffic violation, 97 percent of which were labeled by the state as traffic misdemeanors. Traffic misdemeanors in Texas can include speeding, not obeying law enforcement’s attempt to stop a vehicle, and not obeying traffic signals.

Property Damage

Under Operation Lone Star, 18 percent of all vehicle pursuits by DPS agents across the state have resulted in property damage, amounting to $8.7 million in losses.[119] Over 50 percent of the damages, totaling $4.4 million, come from pursuits in Operation Lone Star counties. In Operation Lone Star counties, average losses per month were around $73,000 before the program and have risen to over $177,000 since March 1, 2021, an increase of 142 percent.[120]

Table 5. Property Damage from DPS Vehicle Pursuits in Operation Lone Star Counties from March 2020 to April 2023

|

Type of Property |

Monthly Average Before OLS (12 mo) |

Monthly Average During OLS (25 mo) |

% Increase |

|

Suspect Vehicle |

$43,444.58 |

$111,024 |

156% |

|

Bystander Vehicle |

$4,194.58 |

$6,114 |

46% |

|

Police Vehicle |

$4,565.17 |

$15,604 |

242% |

|

Property |

$12,557.33 |

$34,719 |

176% |

|

Other |

$8,481.83 |

$9,888 |

17% |

|

Total Avg per month |

$73,243.50 |

$177,350 |

142% |

|

Source: See footnote 6 |

|||

For some border residents, property damage can have devastating consequences. Dilia Villarreal, the schoolteacher who suffered $71,000 in losses, has struggled to recover from the incident. “I’ve gone through so much,” she told Human Rights Watch.[121] “My heart is not doing so good because of this situation. I was just planning to retire and relax with whatever God wants to give me in life. And now having to struggle with all this, it's something else. And nobody seems to want to help me.”[122]

The incident in Villarreal’s property is not included in the records provided by DPS, presumably because the pursuit was led by federal Border Patrol agents. Nonetheless, in a supporting role, DPS deployed the spike strips that led to the vehicle collision. Human Rights Watch estimates that DPS undercounted the losses resulting from the vehicle collision on Norma Saldaña’s property (the incident described in the Summary of this report), by about $20,000.[123]

These discrepancies suggest the figures presented in this report do not represent a full accounting of the damage to Texas residents and motorists inflicted by Operation Lone Star vehicle pursuits.

How Law Enforcement Implements Operation Lone Star Vehicle Pursuits

From state and local police records reviewed by Human Rights Watch, a picture emerges of law enforcement agencies’ implementation of vehicle pursuits under Operation Lone Star. Multiple law enforcement agencies tag-team OLS vehicle pursuits, rely on racial profiling and pretextual stops, and fail to terminate pursuits despite high speeds, poor road conditions, traffic, and proximity to residential and other populated areas. In sum, the number of law enforcement agencies involved and the tactics used appear to be out of proportion to the underlying conduct of transporting unauthorized migrants, racially discriminatory, and a threat to public safety for all on Texas’ roadways.

Multiple Agencies Take Part in Vehicle Pursuits

Arturo Fonseca, who witnessed the aftermath of a crash outside his home that killed a woman and her daughter, put it most succinctly when asked which agency was responsible. “The state [referring to DPS] is the worst one,” he said. “They're the ones that chase people starting from the river ever since Governor Abbott sent state troopers to the region. They have that authority now—and then once they get into the city, other agencies join in, including the local police.”[124]

Several types of law enforcement agencies in Texas are involved in OLS vehicle pursuits, ranging from municipal police, sheriffs’ departments and state Department of Public Safety officers to Border Patrol agents and National Guard troops. At times, they appear to hand off the pursuit of vehicles to each other based on the jurisdiction the pursued vehicle is traveling through. At other times, these law enforcement agencies combine efforts, with several agencies chasing the same vehicle at the same time.

When DPS is not initiating pursuits because of a traffic violation, they are often joining or taking over an active pursuit initiated by another agency, including local police and federal agencies like Border Patrol. It is also common for DPS to hand off a pursuit to other law enforcement. As police incident reports for local agencies participating in Operation Lone Star demonstrate, agencies frequently call each other for back up as they pursue vehicles believed to be transporting individuals who are migrants. For example, out of the five vehicle pursuits the Edinburg Police Department engaged in related to transportation of migrants in the records provided by the Department to Human Rights Watch, four pursuits were initiated by Border Patrol.[125] All four of those pursuits also involved the participation of Texas state troopers or the Hidalgo County Sheriff’s Office, or both.

In Operation Lone Star counties, 6 percent of pursuits by Department of Public Safety officers were initiated or ended by another agency.[126]