Summary

Jasmin Sanchez’s family moved to a public housing development in Manhattan, New York, in the 1970s after twice being displaced, once because her dilapidated apartment was demolished as part of an urban renewal project, and again after their apartment was destroyed in a fire. Sanchez said her family found housing stability for the first time in public housing: “They no longer had to worry about having a place to live.”

For Ramona Ferreyra, who lives in her grandmother’s apartment in a public housing development in the Bronx, also in New York, public housing not only allowed her grandmother to retire in dignity, but also provided Ferreyra the stability to pursue her education and attend and graduate from college. “The things we’ve been able to do in my family wouldn’t have been possible without it,” she said. Sanchez, 43, is currently a student at the City University of New York. Ferreyra is a social entrepreneur and co-founder of Save Section 9, an advocacy group fighting to increase public housing funding.

Since the 1930s, the United States federal public housing program, governed by Section 9 of the US Housing Act, has provided millions in the US with stable, affordable homes. Today, nearly two million people call public housing home. It is a crucial resource for those with low incomes, especially women, people of color, older people, and people with disabilities. Its importance has only grown as housing costs across the country have risen. There is no county in the US where a full-time minimum wage worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment priced at the 40th percentile of area rents, which the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines as “fair market rent.”

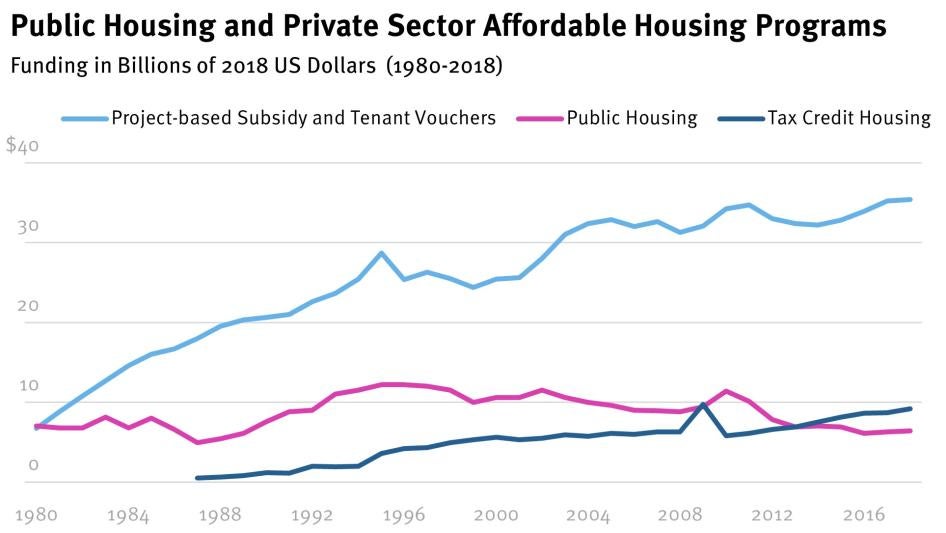

However, in recent decades, the federal government has increasingly shifted its role in providing affordable housing. From the late 1990s, the federal government began slashing budgets for public housing repairs and operations. Coinciding with these cuts, Congress passed a law in 1998, called the Faircloth Amendment, that sharply limits the construction of new public housing, depriving local governments of a potential tool to address the shortage of affordable homes. In place of investing in public housing, the federal government has increased its investment in affordable housing programs that rely on the private sector, such as vouchers and tax credits.

Based on interviews with 37 public housing residents in New York City and various small towns in northern New Mexico and 13 housing policy experts and lawyers, as well as a review of relevant laws and data, this report documents how these government decisions impact the right to housing, both for those residing in public housing and for those who face high housing costs but are unable to access assistance.

The economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic caused millions of people to fall behind on rent, underscoring the importance of public housing. State and federal eviction moratoriums, along with federal emergency rental assistance funding, prevented many from losing their homes. However, the federal eviction moratorium was struck down by the US Supreme Court in August 2021. State and local moratoriums had either already expired or would expire in the following months. Moreover, some states have exhausted their federal emergency rental assistance funding, closing or pausing eligibility to new applicants. In many areas, according to data collected by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University, the number of eviction filings has increased, currently equaling or even exceeding pre-pandemic levels. Housing programs, such as public housing, that provide permanently affordable housing with rents that increase or decrease based on current household income, could partially shelter vulnerable residents from future economic shocks.

In addition to reviewing relevant national data, Human Rights Watch interviewed residents in two public housing authorities (PHAs): the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA)—the largest PHA in the US, which manages over 150,000 apartments—and the Northern Regional Housing Authority (NRHA), a small PHA that manages around 640 homes in various developments across multiple small towns in northern New Mexico.

We selected NYCHA because it is the largest PHA in the country and provides substantial data about conditions in its housing. However, because both housing and construction costs in New York City are high, Human Rights Watch also conducted research in a small, rural public housing authority in a state with a housing market that is markedly different from New York. The issues facing residents in NYCHA and NRHA buildings are particularly severe. Although national data and interviews with experts indicate that residents of housing authorities in other parts of the country may be facing similar experiences, not all PHAs have housing in such a state of disrepair.

However, national data suggests that across the country, PHAs require substantial funding to ensure that they can provide affordable, habitable homes for low-income residents. The interviews Human Rights Watch conducted in New York and New Mexico illustrate both the impact of disinvestment and the risk to other PHAs of continued underfunding.

The report finds that policy decisions taken by the US federal government have resulted in a housing assistance system that fails to ensure the human right to housing. The living conditions of public housing residents are at risk as cash-strapped local governments struggle to maintain their buildings. Millions more, forced to rely on the increasingly unaffordable unsubsidized private market, languish on housing assistance waitlists. The subsidized private-sector alternatives to public housing—themselves insufficiently funded—can be too expensive for the lowest-income tenants and are more likely to become unaffordable over the long term.

The federal government should increase funding for affordable housing overall, with a focus on the lowest-income households. It should specifically increase funding for public housing and repeal the Faircloth Amendment, and it should review other housing assistance programs to ensure that they serve the lowest-income tenants. State and local governments should also increase support for public housing and other programs focused on the lowest-income tenants when federal funding is insufficient to guarantee residents’ rights to adequate, affordable housing.

Defunding Public Housing

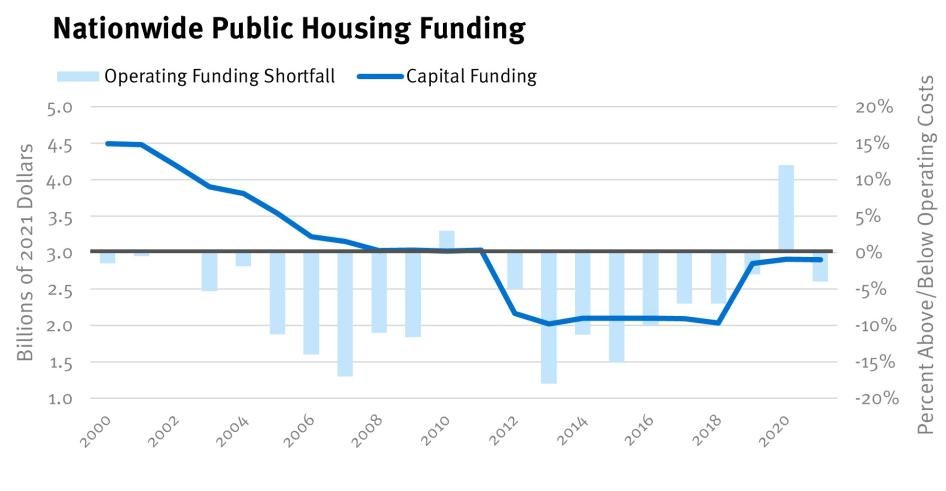

Despite its importance, over the last two decades, the federal government has drastically reduced budgets for public housing, jeopardizing the homes of around 2 million people. Funding for major repairs to public housing declined by over 50 percent between 2000 and 2013 and remained 35 percent below 2000 levels in 2021. Moreover, despite the persistent shortage of affordable housing throughout the country and the 1.5 million applicants on public housing waitlists across the US, the Faircloth Amendment sharply restricts the construction of public housing by preventing PHAs from using federal funds to build new housing if doing so would cause them to have more apartments than they had in 1999.

These cuts caused many public housing developments to fall into disrepair. Nationally, around 10,000 public apartments are lost annually due to dilapidation. “Housing authorities are being forced to make very difficult decisions about what they can and cannot pay for,” Deborah Thrope, deputy director of the National Housing Law Project, a national housing law and advocacy organization, told Human Rights Watch. “Any type of repair that requires any real money isn’t going to get done.”

Residents in NYCHA apartments described how these cuts impacted their communities. According to census bureau data, over the last 20 years, NYCHA housing has gone from having a lower rate of major problems than comparable private housing, to having a rate of major problems over twice as high. Many residents have had to deal with mold, failing heat, and broken elevators, among other hazards. Residents told us they often wait months, or even years, for needed repairs to be made. “If it’s something big and major they try to avoid it,” Catherine Bladykas, a receptionist in a law firm who lives in a public housing residence in Queens, said. “It’s literally years of neglect and deterioration.”

In New Mexico, tenants in NRHA housing also reported poor living conditions, including mold growth, warped floors, pest infestations, and roof leaks. Sarah M., who lives with her children, showed a Human Rights Watch researcher what appeared to be severe mold growth in her apartment, which, like the other serious issues with her home, has gone unaddressed for over a year. “They just keep saying, ‘we will get to you,’” somebody familiar with her situation said. Other tenants said that maintenance has become worse over time.

NRHA tenants also reported waiting for long periods—sometimes years—for even seemingly minor repairs. Daniel Crespin, who has lived in public housing in Las Vegas, New Mexico, for 15 years, told Human Rights Watch that a poorly installed gutter has caused water to leak into his home when it rains. This issue has gone unfixed for over two years. NRHA staff, he said is slow to respond to repair needs. “I would stay waiting every day, over a week ... and they wouldn’t show up,” he said. As a result of such slow responses, some residents expressed the view that the housing authority does not value them. Catherine Parker, 65, who had to wait four years to have warped floor tiles replaced and is still dealing with a number of other unfixed issues, including mold and wall damage, said: “I just don’t feel like [the housing authority] cares about me.”

Human Rights Watch sent letters to the NRHA and NYCHA about their repair practices and housing conditions. Neither housing authority responded.

In many areas, the response to these poor conditions has frequently been demolition. But when public housing is demolished, there is often no requirement that it be replaced with equivalently affordable housing. In some cases, the new, mixed-income housing had fewer units affordable for the lowest-income tenants than the public housing it replaced. Consequently, the original tenants were often unable to access this “revitalized” housing due to higher rents and stricter tenant screening.

With rents in public housing far below what is available on the private market, public housing residents often cannot afford to leave despite unsafe or deplorable conditions.

Bladykas said that, starting in 2019, she struggled for over a year to obtain repairs for a leaking pipe in her apartment building causing wall damage and dangerous mold growth. She was unable to get the repairs done for months. She looked for housing outside of NYCHA during that time but did not find anything she could afford in an online city database of private-market apartments that were part of government affordable housing programs, some of which receive various state and federal subsidies. “Put in my household [size] ... two applications pop up out of pages and pages of apartments.”

For NRHA residents in New Mexico, leaving public housing for better homes is impossible because of a lack of affordable options. “If I could get out of here I would; if I could get out of Taos I would,” one resident said.

Private Sector Alternatives Alone Have Not Addressed the Housing Crisis

As the federal government divested from public housing, it increased funding for affordable housing programs that rely on the private sector, such as “tenant-based” vouchers for tenants to find apartments on the private market, direct “project-based” subsidies to private landlords, and tax breaks for developers of new affordable housing.

Compared with other rich countries, the US is an outlier concerning the amount of affordable housing provided by for-profit entities.

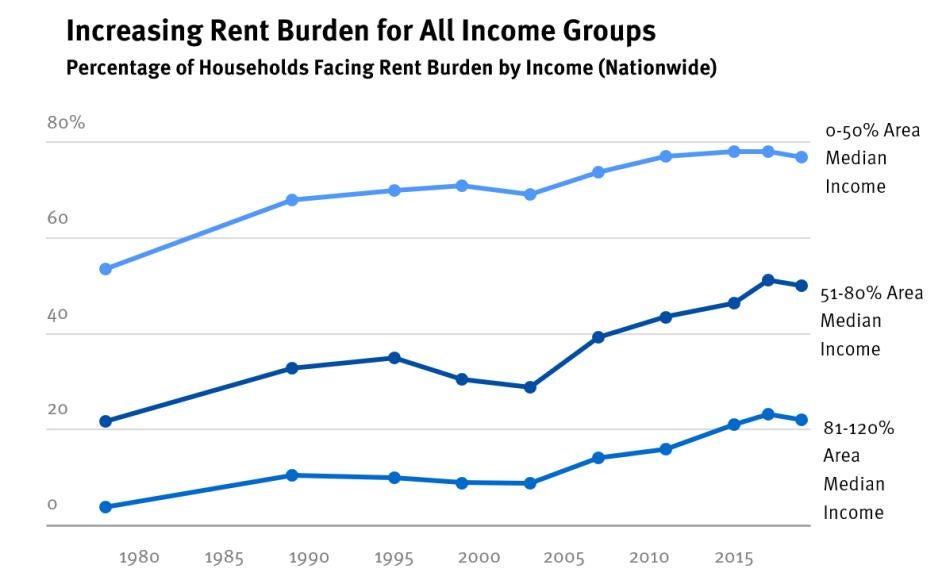

However, funding for these programs is insufficient, and total support for all housing programs in the US comes nowhere near protecting the right to housing for those with low incomes. Nationwide, over 14 million rental households with incomes less than half the median in their area are considered rent-burdened, paying over 30 percent of their incomes in gross rent (including tenant-paid utilities). However, including public housing, tenant vouchers, and project-based subsidies, there are only around 5 million federally subsidized apartments, the vast majority of which are occupied. Around 75 percent of those eligible for these programs do not receive assistance. Moreover, as currently designed, the private-sector programs, which have grown as the amount of public housing declined, can fail to provide stable, affordable homes to the lowest-income tenants.

The most common form of assistance is tenant-based vouchers, where the federal government provides a voucher for the difference between 30 percent of a person’s income and its calculation of the fair market rent in a particular area. However, many landlords do not accept tenant-based vouchers, an issue sometimes referred to as “source of income discrimination.” Reasons for refusing vouchers range from prejudice against voucher recipients to concerns about the administrative requirements and housing condition inspections associated with the program. Beyond the fact that most eligible households do not receive vouchers, many people struggle to find housing at the “fair market” rents—set by HUD at the 40th percentile of area private market rents—which determines the maximum amount a voucher is worth, making them unable to use the voucher or burdening them with paying the difference in rent. HUD data indicates that, particularly in high-cost cities, many voucher recipients are unable to find homes, and nationwide, around half of tenants who do use the vouchers are rent-burdened, meaning more than 30 percent of their income goes to rent and utilities.

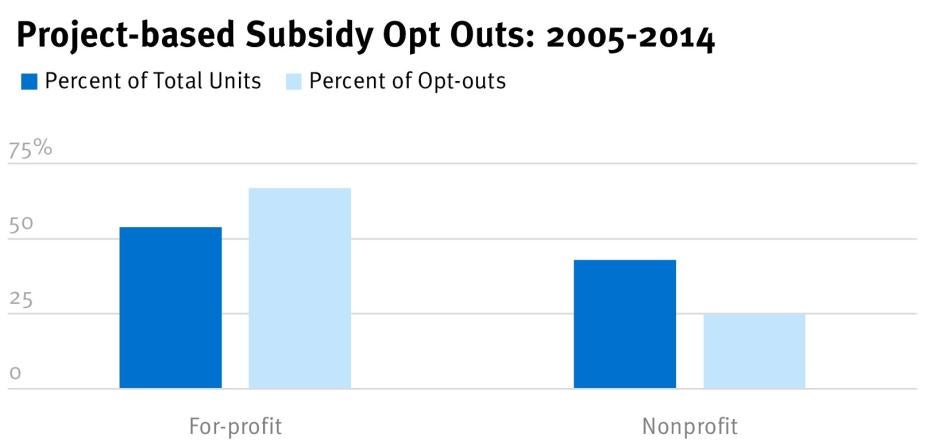

Programs that provide “project-based” subsidies directly to property owners do not have this problem, since rents are calculated to be no more than 30 percent of tenants’ income. However, such homes are scarce. Authorization for new subsidy contracts for HUD’s largest project-based subsidy program, called “Project Based Rental Assistance,” was repealed in 1983. While funding is provided to renew existing contracts, landlords can instead choose to exit the program when agreements expire. Under another program, called the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), which is the largest supply-side housing subsidy program in the US in terms of units, the government provides tax credits to property owners, which are then typically sold and used to finance construction costs. In these properties, rents are determined based on a percentage of the median income in a particular area rather than residents’ individual income. As such, LIHTC homes are often unaffordable to the lowest-income tenants. Like with many other private-sector programs, affordability protections for LIHTC housing are temporary, and landlords can opt out upon their expiration.

HUD did not respond to a letter from Human Rights Watch asking about the effectiveness of tenant vouchers and project-based rental assistance.

Despite their issues, these programs are nonetheless critical sources of affordable housing for many. The underfunding of public housing coincides with a larger failure of the federal government to provide sufficient housing assistance, in any form. While increased support for public housing should be a critical component of national housing policy, these forms of housing assistance should also be expanded and strengthened.

The Human Right to Housing

Everyone has a human right to adequate housing. Under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)—which the US has signed but not ratified—governments are obligated to progressively realize the right to housing, which includes the right to homes that are safe, affordable, and habitable, where residents have legal security of tenure and are protected from evictions that place them at risk of homelessness or other human rights violations.

The US lags other rich countries in both the amount of affordable housing and the extent of funding for tenant rental assistance. In a 2016 comparison of 12 economically developed countries by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, US renters in the lowest income quintile spent the highest percentage of their income on rent.

By disinvesting in public housing, the US government has jeopardized the rights of public housing tenants across the country. By restricting the use of federal funds for new public housing construction, the federal government has deprived local governments of a key tool to address their housing shortages. Significant investment is required, not only for those living in public housing, but also for the millions with high housing costs who would benefit from having an affordable place to call home.

Glossary

|

Area Median Income (AMI) |

The median income in a particular metropolitan area or non-metropolitan county. Housing affordability is often determined with reference to AMI, and AMI is used to define terms such as “very low income” and “extremely low income.” |

|

Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) |

The federal agency responsible for administering many of the major subsidized housing programs in the US, including public housing, housing choice vouchers, and various project-based subsidies. |

|

Extremely Low Income (ELI) |

Income between 0 and 30 percent of area median income. |

|

Fair Market Rent |

The metric HUD uses to set the value of Housing Choice Vouchers. It is generally set to equal the 40th percentile of area private market rents. |

|

Gross Rent |

The amount a tenant pays in rent and utilities. |

|

HOPE VI |

Provided grants to public housing authorities to demolish or rehabilitate public housing developments, often to replace them with mixed-income housing targeting a wider income range. |

|

Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) |

The largest tenant-based voucher program. Recipients can use HCVs to help pay for housing they find on the private market. |

|

Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) |

A program that provides tax credits to developers to fund the construction or rehabilitation of affordable housing. |

|

New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) |

New York City’s public housing authority. |

|

Northern Regional Housing Authority (NRHA) |

A public housing authority that owns and operates housing across various communities in northern New Mexico. |

|

Tenant-based Voucher |

Rental assistance provided to tenants in the form of a voucher that they can use to find and pay for housing on the private market. |

|

Project-based Rental Assistance (PBRA) |

A form of project-based subsidy, consisting of a contract between HUD and a private landlord under which HUD provides funding to the landlord to provide affordable housing. |

|

Project-based Subsidy |

Subsidies provided directly to private landlords, rather than tenants. Common forms are project-based vouchers and project-based rental assistance. |

|

Project-based voucher (PBV) |

A form of project-based subsidy in which a public housing authority ties a portion of its housing choice vouchers to specific apartments. |

|

Public Housing |

Subsidized housing owned and typically operated by a public housing authority. Governed by Section 9 of the US Housing Act. |

|

Public Housing Authority (PHA) |

A regional, county, or city government body that provides public housing and/or administers tenant-based voucher programs. |

|

Public Housing Capital Fund |

A subsidy that funds major repairs, renovations, and upgrades to public housing developments. |

|

Public Housing Operating Fund |

A subsidy that covers the costs associated with operating and administering public housing, as well as conducting routine maintenance. |

|

Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) |

A program that allows public housing authorities to change the funding source for their public housing developments from Section 9 to Section 8 of the US Housing Act. |

|

Rent Burden |

Occurs when a household spends more than 30 percent of its income in gross rent. |

|

Section 8 |

A section of the US Housing Act that establishes the major federal subsidies that typically flow to the private sector. Includes the Housing Choice Voucher program, as well as project-based vouchers and project-based rental assistance. |

|

Section 9 |

A section of the US Housing Act that establishes the public housing program as well as the public housing capital and operating funds. |

|

Severe Rent Burden |

Occurs when a household spends more than 50 percent of its income in gross rent (including tenant-paid utilities). |

|

US Housing Act |

The law that establishes the major federal subsidized housing programs. |

|

Very Low Income (VLI) |

Income between 31 and 50 percent of area median income. |

Recommendations

To the United States Federal Government

- Provide sufficient funding to the Section 9 public housing program to enable PHAs to make all needed capital repairs as well as fund ongoing operations, administration, and maintenance.

- Repeal the Faircloth Amendment and ensure that PHAs have sufficient access to funding for additional public housing construction, should they decide that additional public housing best suits their local housing needs.

- Review the Public Housing Operating Fund formula to ensure that it provides an accurate reflection of PHAs’ operating costs and funding needs.

- Conduct regular studies of success rates (the percentage of voucher recipients who successfully find apartments using their voucher) for Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) recipients and ways in which such rates can be increased. Regularly monitor and publicly disclose both success rates and rent burden rates within the HCV program.

- Conduct a comprehensive review of existing affordable housing programs, including the housing choice voucher program, project-based subsidy programs, and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, to identify measures that would improve the efficacy of these programs and better protect residents’ housing stability and affordability for very low-income households. Along with public housing, expand these subsidy programs to ensure that all individuals, regardless of income, have access to affordable homes.

- Conduct a review of tenant rent levels in public housing and Section 8 households, to determine whether rents are affordable for the lowest-income tenants and whether they sacrifice paying for other basic needs to meet their rental obligations.

- Consider repealing the Qualified Contract loophole in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program.

- Improve oversight of local PHAs maintenance practices. Ensure that PHAs have can access any needed technical assistance to facilitate the use of best practices regarding maintenance and tenant relations.

- Ensure that local PHAs encourage robust resident participation in all aspects of public housing management. Ensure that PHAs remove any barriers under their control to resident organizing.

- Ratify the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the Optional Protocol to the ICESCR. Enact any implementing legislation necessary to allow individuals to enforce their rights under the ICESCR in domestic courts.

To State and Local Governments in New Mexico, New York, and Other US States

- Comprehensively review state and local affordable housing programs and make any modifications required to ensure that they create housing that is affordable to the lowest-income households.

- Increase funding for public housing to compensate for insufficient federal support and ensure that PHAs can meet their maintenance and repair needs.

- Support housing programs focused on the lowest-income tenants when federal funding is insufficient to guarantee residents’ rights to adequate, affordable housing.

- Ensure that an independent public body is effectively overseeing local PHAs. Such a body should be able to enforce habitability standards.

To the New York City Housing Authority, Northern Regional Housing Authority, and Other Public Housing Authorities

- Actively encourage resident participation in all aspects of management, including maintenance. Where such organizations do not currently exist, encourage the formation of resident councils, as defined under federal regulations.

- Review and revise any maintenance practices which hinder the ability to promptly and effectively respond to residents’ repair needs.

Methodology

This report examines how budget cuts have impacted the accessibility and conditions of public housing. It also discusses other subsidized housing programs utilizing the private sector, which have grown as public housing stocks have decreased. The report focuses on public housing authorities in New York and rural New Mexico and utilizes available nationwide data.

Human Rights Watch interviewed a total of 50 people for this report between March 2021 and April 2022. We interviewed 27 current or recent residents in NYCHA housing across 14 different housing developments and 10 current residents across 3 public housing developments managed by the Northern Regional Housing Authority in New Mexico. Thirteen activists, housing policy specialists, and housing lawyers were also interviewed.

In addition, Human Rights Watch reviewed data and reports from the US Census Bureau, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), and various housing policy organizations. These sources detailed funding trends, the extent of the affordable housing crisis, demographic data on public housing residents, and housing conditions.

Conditions in NYCHA—the largest PHA in the US—and NRHA—a small rural public housing authority in a state with lower housing and construction costs—illustrate the severe impacts of underfunding on residents of these PHAs. National data and expert interviews suggest that PHAs across the country require additional funding to meet their repair needs. However, the severe problems described by NRHA and NYCHA residents do not reflect conditions in every public housing development across the country, though they illustrate the risks associated with underfunding.

Some residents and staff requested to remain unidentified, expressing fear of retaliation from the housing authority. Throughout this report, individuals who requested anonymity were given first names and an initialized last name (e.g., Thomas H.).

Interviews were conducted by videoconferencing and in person. Research for this report was conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic, with staff taking precautions to minimize the risk of transmission. All interviewees freely consented to the interviews. Human Rights Watch explained to them the purpose of the interview and did not offer any remuneration.

This report is a follow up to a report on how NYCHA used a program called the Rental Assistance Demonstration to lease a portion of its public housing to private companies for 99-year terms and outsource management. This report focuses broadly on the public housing program itself as well as the other affordable housing programs that have been expanded as the size of the public housing stock decreased.

I. The Promise of Public Housing

It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States ... to assist the several states ... to remedy the unsafe and insanitary housing conditions and the acute shortage of decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings for families of low income, in rural or urban communities.

— US Housing Act, 1937

Modern public housing largely started in the aftermath of the Great Depression of the 1930s, with the Housing Act of 1937 providing federal funding to state-chartered, local Public Housing Authorities (PHAs), which would construct and manage low-cost housing. Between 1949 and 1994, the number of public housing apartments increased from around 170,000 to around 1.4 million. But that number flatlined and then declined in the decades following, today standing at around 930,000 homes.[1] In the meantime, the country’s shortage of affordable housing in the unsubsidized private market has worsened.

Today, around 2 million people live in those 930,000 public housing apartments in the US.[2] The housing provided by PHAs have been islands of affordability, enabling low-income people to maintain a stable home at an affordable rent, even as housing prices on the private market have steeply increased while wages have stagnated. These protections have long been the cornerstone of diverse and thriving communities in public housing that have allowed people, regardless of income, to provide for their families, pursue an education or retire in dignity.

Racist housing policies and practices—such as redlining, in which private and government lenders systemically denied mortgage financing to those in predominately Black and immigrant neighborhoods—denied people of color the same access to housing, and thus wealth, afforded to white people.[3] These policies and practices, along with other manifestations of structural racism, have made Black and brown people in the US especially reliant on subsidized housing, including public housing. Nationally, 43 percent of heads of household living in public housing are Black, and 26 percent are Latinx.[4]

However, the history of the public housing program itself reflects the country’s history of structural discrimination. Many public housing developments were constructed as part of “slum clearance” programs that displaced thousands of Black, brown, and low-income households and were concentrated in under-resourced, segregated communities.[5] Moreover, since public housing was often explicitly segregated, its construction sometimes turned formerly integrated communities into segregated ones.[6] The segregation of public housing was exacerbated during the mid-twentieth century. Pressure from private real estate interests helped place strict income limits on public housing, displacing higher-income tenants, and “white flight”—driven by racist attitudes and subsidized by federal policies enabling low-cost home ownership for white families—led to many white households leaving public housing.[7]

Nonetheless, today, public housing is a critical resource for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color throughout the US. In places like New York City, public housing has preserved affordable rental housing opportunities for Black and brown residents. [8] But without further structural reforms and reinvestment in marginalized communities, public housing cannot itself solve a housing crisis influenced by racialized and classist policy choices and which perpetuates segregated housing and the Black-white wealth gap.[9]

A Nationwide Housing Shortage

While, in some respects, the housing crisis is most pronounced in large, high-cost metropolitan areas, communities across the country, whether rural, suburban, or urban, are facing acute affordable housing shortages. Nationally, there are just 36 affordable, available, and adequate homes for every 100 extremely low-income households. Across rural suburbs and non-metropolitan areas, these figures were 41 and 50, respectively.[10] No US state has enough affordable housing, and there is no county in the US where a full-time minimum wage worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment priced at the 40th percentile of area rents.[11] Among extremely and very low-income households, over three-quarters are rent-burdened, paying over 30 percent of their income in gross rent, including tenant-paid utilities.[12] Nationally, nearly half of all rental households—and 38 percent in households in rural communities—were rent-burdened.[13]

The Covid-19 pandemic has only underscored the current housing crisis and the need for increased funding for permanent affordable housing programs. The economic fallout from the pandemic caused millions to fall behind on rent, placing them at acute risk of eviction.[14] Only the combination of eviction moratoriums and unprecedented federal emergency rental assistance funding prevented many from losing their homes during the first year or two of the pandemic.[15] However, the federal eviction moratorium was struck down by the US Supreme Court in August 2021,[16] and, at time of this writing, most state and local protections have expired. Moreover, some states and localities have exhausted their federal emergency rental assistance funding, closing or pausing eligibility to new applicants.[17] According to data collected by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University, which tracks eviction filings in 31 cities and 6 states, in many areas, the number of eviction filings has increased over 2022, equaling or in some cases exceeding pre-pandemic levels.[18]

The nearly one million public housing apartments are located in communities large and small across the US. Despite the budget cuts, detailed in the following sections, which reduced the number of public housing apartments, public housing remains a critical source of affordable housing. Nationally, 80 percent of public housing households have extremely or very low incomes; these groups are especially likely be rent-burdened.

PHAs are required to reserve their homes for those with low incomes, and rents are typically capped at 30 percent of a household’s adjusted income, where household income is reduced based on the number of dependents and for certain expenses such as child care.[19] With rents capped at 30 percent of household income and adjusted when a tenant loses earnings, public housing sharply lowers the incidence of rent burden for such households and can protect residents from economic shocks, such as that triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic.[20] Such stability is rarely found in the unsubsidized private rental market. In the US, the average public housing tenant pays $392 a month in rent.[21] By contrast, a private one-bedroom apartment priced at the 40th percentile of area rents costs, on average, $1,105 a month. A two-bedroom costs, on average, $1,342 a month.[22]

Affordability in New Mexico

With just 44 affordable homes available to every 100 extremely low-income households in the state, New Mexico, like New York, has a severe housing shortage.[23] Across the state, 67 percent of extremely low-income households are severely rent-burdened, paying over 50 percent of their income in gross rent (including tenant-paid utilities).[24]

Each of the ten counties in the mostly rural, northern part of New Mexico—where the Northern Regional Housing Authority (NRHA) operates public housing and housing choice voucher programs—has a housing shortage. In seven, over 30 percent of all renter households are rent-burdened.[25] The 40th percentile market rent for each county in the region is, on average, $751 a month for a one-bedroom apartment and $898 for a two bedroom.[26]

In NRHA public housing, the average household pays $370 per month in rent and utilities. 70 percent of residents have incomes below 50 percent of the area median. Seventy-eight percent of NRHA residents are identified in HUD data as Hispanic or Latinx.[27] Multiple NRHA residents told Human Rights Watch that, if they lost their housing, they would have nowhere to go.

Roger Chavez, 68, lives in Questa, New Mexico, a small town at the base of the Taos Mountains, and has been living in public housing since 2001. His sole source of income is a modest monthly social security check, and he currently pays $343 per month in rent. “My priority is paying the rent and the utilities,” Chavez said. He added that by the middle of the month, after paying rent, utilities, and other bills, he can have as little as $100 to spend on other necessities. This has left him unable to visit his daughters or grandkids in Colorado because of the travel expenses. “But so long as I have a place to live,” Chavez said, also describing how he fears that, if he lost his housing, he would be at risk of homelessness.[28] Chavez stated that throughout most of his time there, he had enjoyed living in public housing. “I’ve always lived a happy life here,” he said.[29]

Other residents experienced poor housing conditions in the regular housing market in New Mexico. Mateo S., who is in his 60s, told Human Rights Watch that, before moving into public housing over five years ago, he was paying around $200 a month to live in a home without water or electricity.[30] Rebecca F., a long-term public housing resident, told Human Rights Watch that she and her child were experiencing homelessness before getting into public housing: “We were homeless, and somebody told us about the housing, so we put in an application, and we got a home right away.”[31]

“They No Longer Had to Worry About Having a Place to Live” – Public Housing in New York City

When Jasmin Sanchez’s grandparents came to New York City from Puerto Rico in 1959, they rented an apartment on the Lower East Side. They were forced to move when the city demolished the apartment in the late 1960s as part of an urban renewal project and were promised priority in the new housing that would be built. But no new housing was built on that site until 2019, at which point her grandparents were deceased. “They waited literally their entire time of being a citizen here to get back to that apartment that was never built,” Sanchez told Human Rights Watch. [32] In the early 1970s, the apartment the family moved to was destroyed in a fire. Sanchez claimed the landlord had burned it down, a tactic some landlords used to claim insurance money at a time when redlining could make refinancing buildings in majority-minority neighborhoods impossible.[33] However, soon after, Sanchez’s family application for public housing was accepted. “They found permanent housing in public housing, after being hit so hard with horrific housing circumstances due to our government.” Public housing, she said, enabled her grandparents to raise a family as well as Sanchez herself, and allowed them to focus on their education. “They no longer had to worry about not having a place to live.”[34] Sanchez is currently studying Labor Studies at the City University of New York.

This sentiment was echoed by the more than two dozen residents living in public housing in New York whom Human Rights Watch interviewed. The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), home to nearly 340,000 people, is the largest public housing authority (PHA) in the United States.[35] Especially as housing costs rise and wages continue to stagnate, NYCHA has increasingly become one of—if not the—last bastion of deeply affordable housing in an increasingly expensive city.

According to the 2021 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey, conducted by the US Census Bureau, NYCHA housing accounts for around 8 percent of New York City’s rental housing stock, but it accounts for 31 percent of all apartments in New York City with rents under $900 per month. The estimated median gross rent for NYCHA tenants is $510 a month, compared to $1950 a month for those in unregulated private apartments and over $1547 for rent stabilized tenants.[36]

Wages have not kept up with the city’s rising rents, making public housing a critical resource for low-wage workers, who account for a majority of NYCHA residents aged 18-61.[37] However, across all NYCHA residents, the average household income is $24,454, more than $10,000 below the city’s official poverty line.[38]

The affordability and stability of NYCHA has made it especially important for securing the right to housing for older New Yorkers, people of color, households with children, and people with disabilities. As public housing funding decreased, the federal and city government increased funding for alternative programs that rely on the private sector, such as federal and state tax breaks for developers who build housing which meets certain affordability requirements. But such housing is often less affordable than NYCHA and can be out of reach for many.

Cesar Yoc, a NYCHA resident in the Bronx and member of his local community board—a public body composed of volunteers who advise on budgetary and land use issues—described the role of public housing in the city’s broader housing market. “Public housing is the last actual affordable housing in New York City,” Yoc told Human Rights Watch. “They keep saying there’s affordable housing out there, but for all these projects I keep seeing, hardly any of them are for people in this neighborhood.”[39] Other residents expressed similar sentiments. Catherine Bladykas, a receptionist for a law firm and NYCHA resident in Queens, described her experience searching for housing using a city database of private-market apartments that are part of government affordable housing programs, including those that receive various state and federal subsidies: “You see all the lotteries of what’s going to be built, what’s already been built,” she said. “Put in my household, now it’s three people, me and my twins, and my income, two applications pop up out of pages and pages of apartments.” Bladykas also described seeing many apartments in the database with income requirements above what she could afford: “Who at the bare minimum makes $75,000? I don’t.”[40]

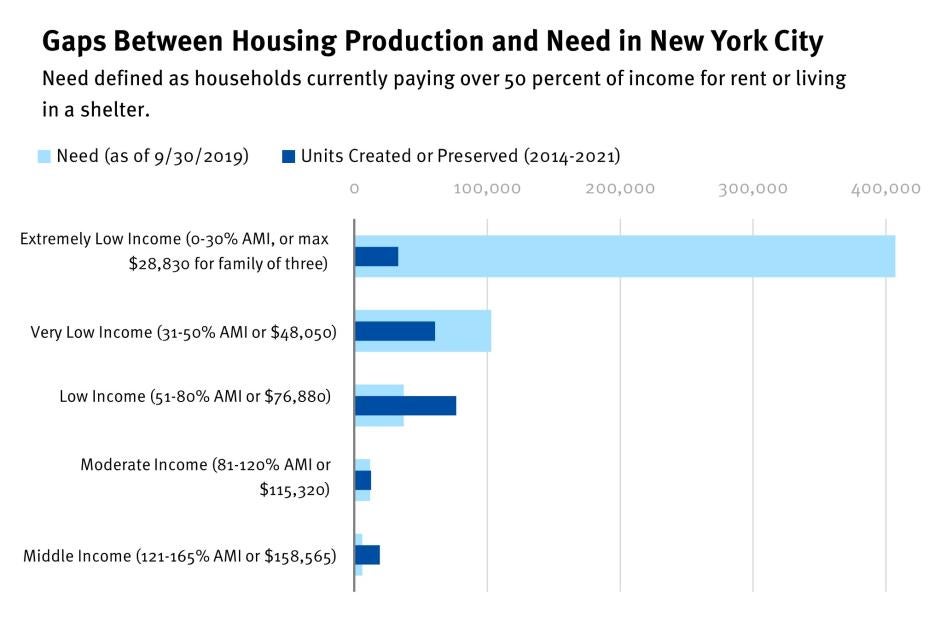

Anxieties about finding affordable housing outside of NYCHA are well-founded. Households with incomes less than 50 percent of the area median face the greatest housing needs. But the city’s recent affordable housing plans have disproportionately created or preserved housing for higher income groups.[41]

Some of this mismatch is due to the fact that the plans have utilized a state-authorized program called 421-a—which cost the city $1.7 billion annually—which exempts “affordable” housing from property taxes. However, the program permits this “affordable” housing to set rent levels targeted at those making well over the median income,[42] even though, the chart below illustrates, the largest needs for housing are among those with incomes less than 50 percent of the area median. The New York State Legislature allowed the 421-a program to expire in June 2022.[43] The dearth of housing affordable to those with very low incomes is also attributable, in part, to federal programs that finance some buildings under the city’s plan, which often rely on for-profit landlords, as detailed in Section III.[44]

Enabling Communities

The average NYCHA resident stays in public housing for 25 years.[45] Such long tenures are likely due to several factors, including the relative affordability of NYCHA, a lack of economic mobility across both the local and national economy, and the fact that many public housing residents, both in NYCHA and nationally, have fixed incomes.[46]

Residents’ long-term, often multi-generational, tenure in public housing also highlights its importance for older people. Over 40 percent of NYCHA households, and 36 percent of public housing households nationally, are headed by someone age 62 or older.[47]

Ramona Ferreyra, 41, a social entrepreneur, told Human Rights Watch that her grandmother, who passed away in December 2020, loved her apartment and was able to retire because of the stability NYCHA housing provided.

She loved living in this building. My grandmother, she always said this was where she was going to die. She never wanted to live anywhere else again. They all call it “the last stop,” all of her friends. [T]here’s a senior citizen center, this community that, they get in when they are 65.... They’re spending 30 years together, and it’s the only 30 years where they have quality time.... There is no way she would have been able to have that quality of life at the end of her life without public housing.”[48]

Multiple interviewees who grew up in public housing decades ago also spoke fondly of the community they experienced during their childhood. Celine M. described growing up in NYCHA in the 1960s. “Growing up in NYCHA, I had a great childhood.... It was quite a community,” she said. “Everybody knew everybody’s kid. You couldn’t get away with anything, because your parents knew about it before they got home from work.”[49]

Addrana Montgomery is a housing rights attorney at TakeRoot Justice, an organization that provides legal, research, and policy support to community-based groups in New York City. Her family left public housing due to increased crime and worsening conditions in the mid-1970s, but she says her mother still speaks fondly about her neighbors in NYCHA. “It was a very cohesive network of families and friends that developed in this stock of housing, and that remains today as well,” Montgomery said.[50]

“It Was So Beautiful:” Residents Describe Better Housing Conditions in Past Decades

In contrast to the dilapidated and dangerous apartments that mar NYHCA’s current stock—detailed extensively in the following sections—most of the long-term NYCHA tenants interviewed told Human Rights Watch that conditions used to be far better. Apartments were usually described as being in good condition, and when issues arose, workers were quick to address them.

Celine M. grew up in NYCHA housing during the 1960s and 1970s. “The buildings were clean; the grounds were clean,” she told Human Rights Watch, adding, “If there was a problem in your apartment or you needed something fixed, usually [maintenance workers] came the same day.”[51]

La Keesha Taylor, 48, a former teacher and lifelong resident of Holmes Towers on New York City’s Upper East Side, said that, when she was growing up in the late 1970s and early 1980s, maintenance workers could be easily found and would respond quickly to repair requests. “Those were the good times in NYCHA,” she said. [52]

“When I was young, I remember going to Grandma’s and spending the weekend with her, or spending the week with her, and having this sense of like, you were in a small town,” Ferreyra told Human Rights Watch. “Everything was made with this idea or this intent of having a space for everyone to fit in.”[53]

Other long-term public housing tenants also remembered a time when grounds were clean and maintenance was responsive. Saundrea Coleman is a former payroll supervisor for the New York City Police Department, who retired following a workplace injury and who currently residents in NYCHA housing on the Upper East Side. She also grew up in public housing. “You could actually walk barefooted outside,” Coleman told Human Rights Watch. “It just was clean, there was no issue with repairs. I remember my mother pulling in all the furniture every three years to get her paint job, that was like clockwork.”[54] Carla R., who first moved into public housing as a teenager, told Human Rights Watch, “When I first came here, it was so beautiful, I thought I was in paradise.”[55]

II. Federal Disinvestment in Public Housing

It is the policy of the United States ... that the Federal Government cannot through its direct action alone provide for the housing of every American citizen, or even a majority of its citizens, but it is the responsibility of the Government to promote and protect the independent and collective actions of private citizens to develop housing and strengthen their own neighborhoods.

>— Quality Housing and Work Opportunity Act, 1998

Up until the 1970s, public housing, governed by Section 9 of the US Housing Act, was the primary vehicle for providing low-income housing. However, in the last decades of the 20th century, growing hostility to public housing prompted the federal government to gut its budgets and establish regulatory barriers to limit its growth. Although federal spending on housing remains far below what is needed to secure the right to housing, the modest budget was increasingly directed to various private sector-led programs to provide affordable housing, such as subsidies for private developers and landlords and vouchers for tenants to use on the private market.[56] As detailed in the following sections, these programs sometimes fail to provide sufficiently affordable housing, but disinvestment in public housing has itself had a devastating impact on the right to housing.

PHAs receive almost the entirety of their subsidies from the federal government, through two main funding sources managed by HUD: the capital fund, used for large repairs, and the operating fund, used for routine maintenance and operations. These funds are intended to help to make up the difference between rents and the cost of operating, maintaining, and upgrading housing units. [57] However, decades of insufficient appropriations by the federal government—combined with a lack of investment by state and local governments—have caused the public housing stock in the US to deteriorate, leading to residents facing dangerous and inhumane conditions. [58]

Midcentury Struggles and Reagan-Era Cuts

Public housing, much of which was in urban areas, was not immune from the issues affecting cities in the postwar decades. White flight during the 1950s and 1960s led to declines in both population and revenue in many urban cores.[59] Deindustrialization further exacerbated the economic problems facing urban residents.[60] Such forces contributed to the increasing poverty of public housing residents, and consequently, declining rental income for PHAs. Originally, public housing was designed to be funded solely through tenant rents, and PHAs initially tried to cover increasing operating deficits by increasing rent.[61] However, in 1969, Congress capped public housing rents at 25 percent of household income but failed to provide a sufficient subsidy to make up for PHAs’ lost revenue, causing some to cut back on maintenance.[62] These factors contributed to the failure of various public housing developments, such as the famous demolition of St. Louis, Missouri’s Pruitt-Igoe complex in 1972.[63]

Funding for public housing—along with all housing programs—was again cut during the administration of President Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s.[64] While the addition of new public housing buildings continued during the decade, though at a slower pace, meager funding contributed to worsening conditions in some developments.[65]

However, not all public housing developments were in a state of disrepair during this time. The 1992 final report of the National Commission on Severely Distressed Public Housing classified just 6 percent of the public housing stock (around 86,000 homes) as “severely distressed” based on crime rates, building conditions, management performance, and socioeconomic indicators.[66] A 1999 HUD survey found that two-thirds of public housing residents were satisfied or very satisfied with their homes.[67]

By 1998, the public housing stock faced a backlog of modernization needs totaling an estimated $24.6. billion.[68] However, in the years that followed, funding for these repair needs declined, further threatening the living conditions of public housing residents. Furthermore, federal policy changes encouraged the reduction of the public housing stock.

“The Magna Carta of Disinvestment” — The Faircloth Amendment

The government’s growing rejection of public housing was arguably codified in the late 1990s, when Congress, with the support and encouragement of President Bill Clinton, cut various benefit programs.[69]

The turn away from public housing is encapsulated by the 1998 Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act (QHWRA). The law made it easier for PHAs to demolish public housing by allowing PHAs to use capital funding to tear down their developments and by formally repealing the requirement that for each unit demolished a new unit must be built.[70] The Act also contained the Faircloth Amendment, essentially marking the end of new public housing construction.

The Faircloth Amendment effectively prevents PHAs from using federal funds to construct or acquire new public housing if it would result in the PHA having more public housing units than it did in October 1999.[71] While the Faircloth Amendment does not itself cut funding, it gave legal expression to the government’s turn away from public housing. Victor Bach, senior housing policy analyst at the Community Service Society in New York City, explained its impact on NYCHA and other PHAs to Human Rights Watch: “The Faircloth Amendment is the Magna Carta of federal disinvestment,” Bach said. “It shows Congress’ attitude toward public housing: The idea was not to expand it—in fact, the idea was to reduce the number of public housing units nationwide.”[72]

The Faircloth Amendment operates as a constraint on the ability of states and localities to use federal funds to address the severe lack of affordable housing in the US, and it is thus an obstacle to the US meeting its obligation to progressively realizing the right to housing. However, the funding cuts that followed the passage of the QHWRA have resulted in the loss of so much public housing that many PHAs could—with adequate funding—build thousands of additional homes before they reach the number of units available in October 1999, or their “Faircloth limit.”

For PHAs facing aging buildings and spiraling capital needs, the passage of the Faircloth Amendment coincided with the point at which limited federal funding started to become, in the words of Bach, “starvation funding.” [73] As the chart below shows, funding for major repairs to public housing declined over 50 percent between 2000 and 2013 and was 35 percent below 2000 levels in 2021. Funding for day-to-day operations during this time was also consistently below PHAs’ operating costs, as estimated by HUD’s subsidy formula.[74]

Underfunding Impacts Public Housing Across the US

Underfunding has affected PHAs large and small across the country. Nationwide, it is estimated that public housing requires over $70 billion to fully meet its repair needs.[75]

“Every housing authority will tell you that they struggle with deferred maintenance, almost all of them,” Molly Parker, a journalist who has covered public housing in rural communities, told Human Rights Watch.[76] Deborah Thrope is the deputy director of the National Housing Law Project, a national housing law and advocacy organization with offices in Washington, DC, and San Francisco that supports legal services organizations across the US. She similarly described how funding cuts have impacted PHAs nationwide:

We consistently hear that, on a basic level, stuff doesn’t get fixed. Housing authorities are being forced to make very difficult decisions about what they can and cannot pay for, and often times it is the band aid repairs that get done, whereas the long-term capital needs are never met. Any type of repair that requires any real money isn’t going to get done.[77]

Worsening conditions have resulted in many public housing developments being demolished, often without being replaced by similarly affordable housing. Across the US, over 100,000 units of public housing were lost between 2000 and 2012.[78] Currently, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, between 10,000 and 15,000 units of public housing are demolished annually because they are no longer habitable.[79]

Programs like HOPE VI, discussed in Section III below, for which HUD awarded grants between 1993 and 2011, allowed some PHAs to replace demolished public apartments with “revitalized,” often privately operated, mixed-income communities. However, the housing created though this program was often less affordable than the public housing it replaced, resulting in a net loss of affordable housing and the displacement of thousands of families.[80]

Residents have borne the brunt of the federal government’s abandonment of public housing, but the over 1.5 million applicants on PHA waitlists across the country also suffer from the lack of adequate, available public housing.[81]

NYCHA Tenants Describe the Impacts of Funding Declines

Like for other PHAs, HUD subsidies make up over half of NYCHA’s annual budget, so the effect of federal cuts was devastating.[82] Moreover, for NYCHA, the federal cuts during the 2000s coincided with funding cuts at the city and state level, [83] amounting to “almost a perfect storm of disinvestment,” according to Bach.[84]

According to the Census Bureau’s New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey (NYCHVS), in the early 2000s, the percentage of NYCHA households reporting major issues was similar to, or lower than, low-income private rental households. By 2011, however, deficiency rates had skyrocketed, far exceeding that of private low-income rental households.[85] In the latest NYCHVS, conducted in 2021, 43 percent of NYCHA households reported three or more maintenance deficiencies.[86]

Various long-term public housing residents told Human Rights Watch that their homes deteriorated over the 2000s and 2010s. Sanchez described how repair needs escalated in her development, Baruch Houses, on the Lower East Side, New York: “It was about the late 2000s, and then I started seeing it more like 2010, 2012, 2014,” Sanchez said. “Water coming in through the ceilings, ceilings were cracking, water coming in below the tiles. The stairwells were deteriorating.”[87] Ferreyra, who frequently visited her grandmother in Mitchell Houses in the Bronx over this time, also described seeing the building gradually fall apart over the 2000s. “When I would come home, every Christmas, the conditions just worsened, every single time, by the 2000s, like 2003 – 2005, it was palpable.”[88]

Deficiencies in NYCHA Housing

Ferreyra has had constant issues with her NYCHA apartment, resulting primarily from a water leak in her ceiling. This has caused various issues, including mold: “At one point the apartment was covered in black mold.” The leak had also damaged her floors and cabinets, and led to cracks in her apartment’s walls, which Ferreyra says has exposed her family to lead paint.[89]

Mold was an issue for various residents Human Rights Watch interviewed, including some who either have asthma or have children with asthma. Research suggests that mold exposure can exacerbate asthma or increase the likelihood of developing it, cause severe allergic reactions, and lead to coughing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath.[90]

Human Rights Watch was able to verify specific accounts of only some interviewees, but mold has been a widespread issue in NYCHA. According to a complaint filed against NYCHA by the US Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York (SDNY)—which, in 2019, resulted in the appointment of a federal monitor (discussed below)—water leaks and mold have been widespread problems in recent years, with NYCHA residents complaining of flooding and water leaks from ceilings, walls, or pipes, “between 117,000 and 146,000 times each year” between 2013 and 2016.[91] The SDNY complaint also noted that rates of asthma, according to the New York City Department of Health, are four times higher in NYCHA housing than in the city as a whole.[92] The Legal Aid Society, a non-profit legal aid provider, reported that between January and September 2019, there were over 30,000 complaints of mold or mildew.[93]

The lack of adequate funding that leads to these problems in the first place means NYCHA has had to address repairs superficially. NYCHA residents consistently told Human Rights Watch that because repairs often failed to correct the causes of the problems tenants reported, they were left having to deal with problems such as mold, leaks, and cracked walls, for months or even years.

Catherine Bladykas, a resident at NYCHA’s Queensbridge Houses told Human Rights Watch that she struggled trying to get a water leak fixed in her housing unit, reflecting NYCHA’s inability to make major repairs. HUD last conducted a physical inspection of Queensbridge in September 2019. HUD inspected two buildings, giving one a score of 21 out of 100 and the other a score of 10, both well below the minimum passing score of 60.[94] Bladykas and two of her children have asthma. A leaking pipe in her bathroom was causing wall damage and mold.[95] At first, NYCHA maintenance workers only made superficial repairs, merely redoing the wall’s plaster and paint, Bladykas told Human Rights Watch: “They would say that it is a plastering job, and apparently it’s not a plastering job, there is something happening inside the walls that they just don’t want to get to,” she said. “They’re just sending people to put band-aids on the situation ... and then in another three months, four months, it’s just cracking, black stuff is coming out.”

Eventually, Bladykas said that her apartment was completely renovated over 6 weeks, but the issue was not fixed, with water still leaking from the walls. Ultimately, she said, there was a broken pipe in the basement of her building, which required replacing. All in all, she said, the process for replacing the pipe took over a year. “If it’s something big and major like that they try to avoid it,” Bladykas said. “What happened in that apartment, I can guarantee you is happening all around the five boroughs. It’s literally years of neglect and deterioration.”[96]

According to Gregory Russ, the then-CEO and Chairman of the Board of NYCHA, who stepped down as CEO in September 2022 but remains Chairman, inadequate funding for major repairs has made daily maintenance more difficult and more expensive: “For NYCHA, the lack of capital is not only increasing the deterioration of buildings, but it is also driving the cost of everything up.” Russ told Human Rights Watch that issues such as heating as well as leaks and mold are particularly difficult: “[a] 50-year-old pipe is still 50 years old ... in order to address that leak in one unit, we should be replacing 19 stories of pipe.”[97]

NYCHA residents Human Rights Watch interviewed also described a litany of other problems due to inadequate upkeep of buildings. Taylor told Human Rights Watch that her floors are coming up and that she had a roach infestation that lasted for months. Taylor, who lives on the 25th floor of her building, also told Human Rights Watch that constant elevator outages caused her to lose her job. “[My babysitter] was not willing to walk up 25 flights,” she said. “So how many times am I going to tell my boss I can’t do it?... I was late too many times.” Taylor said her biggest issue was excessive heat.[98]

Heating issues are common in NYCHA housing.[99] Coleman, a resident in public housing on the Upper East Side, described the effects of inconsistent heat on her late mother, who also lived in NYCHA housing: “I recall going to visit my mother, and she has on thermal socks, a robe, another robe, blanket around her ... and using the ovens for heat.” Coleman herself also has heating problems. “Sometimes it’s too much heat, and sometimes there is not enough heat,” she said. “It’s days you cannot even breathe in your apartment. Because we have infestation [outside] on the grounds, of mice and rats, over here ... it is hard to open your window up [for fear of letting in mice and rats].”[100]

Renovating public housing to an adequate standard is far more costly today than it would have been had funding been adequate in the decades prior. At current funding levels, though, PHAs will continue to face mounting capital needs. “Public housing is not negotiable; the things we’ve been able to do in my family wouldn’t have been possible without it,” Ferreyra said. “I’m still fighting to justify the fact that we deserve to have a place to live.”[101]

“And Guess What, You’re Still Waiting” — Long Repair Times

NYCHA responded to budget cuts by reducing staff, including at the property management level, as well as by reducing contracting commitments.[102] Nearly every resident interviewed noted that the time it took to get needed repairs had steeply increased from decades prior.

“I remember very well, whenever we had an issue with the apartment, my grandma would go to the management office and report it ... it [would] get done within 24 hours,” Sanchez told Human Rights Watch. “That is not the case in 2021.” Taylor also contrasted today’s maintenance with how repairs were conducted decades ago. “Back in the day, we used to just go down the ramp to where all the maintenance men were,” she said. “Now, you have to wait for special trades, you have to wait for whoever. And you’re waiting, and you’re waiting. Guess what, you’re still waiting!”[103]

Yoc, similarly, told Human Rights Watch that maintenance delays were the single biggest issue he faced. He described putting in repair requests (referred to as “tickets”) over a year ago, and never seeing repairs: “Operations has just gone down the toilet in the last decade. The waiting period is crazy.” Yoc stated that he has been waiting a year for NYCHA to fix his cabinets, which he says are rotting because of a leak in his apartment’s plumbing. The experience of making repair requests, only for the problem to remain unresolved, can be exhausting and demoralizing. “We’ve sort of given up,” Yoc said. [104]

The waiting time to resolve simple non-emergency service requests has doubled from 14 days in 2015 to 36 days in 2021, increasing year-over-year.[105] Waiting times for more complex repairs, such as plumbing, carpentry, or paint, in July 2022 were 320 days.[106] This especially long waiting time is likely due in part to operational disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.[107] However, significant wait times predate the pandemic. In 2019, it took NYCHA 83 days on average to complete repairs.[108] As of July 2022, there are 639,000 open work orders across NYCHA housing. According to the Authority, a “manageable workload” is around 90,000 open work orders.[109]

A consistent theme that emerged in interviews with NYCHA residents is both the degree of knowledge of one’s rights and the sheer amount of determination that it takes to get any repairs completed. Residents described only being able to obtain repairs after they threatened to go to the media, sue, withhold rent, or contact politicians.

Sanchez told Human Rights Watch that she was only able to get NYCHA to make certain repairs after taking them to court: “They were able to get my repairs done in about three days once I did that.”[110] Taylor expressed similar frustrations: “Why is my only recourse to sue you, in order to live in a safe and healthy home?”[111] Celine M. described going over the heads of her building’s management and calling repeatedly to receive needed repairs. She also had to keep fastidious records, as NYCHA would close out tickets without completing work. “I was a pain in the ass,” she said. “Because I have a son, I could not live in my apartment in that condition with my child.”[112]

Sylvia T., a former housing assistant at NYCHA who assisted tenants with repair requests and other issues, told Human Rights Watch that repairs would often only be prioritized if residents spoke to the media or politicians. “It has to be something big, like somebody calling the news, somebody calling a congressman,” she said. “I used to tell [my tenants], at risk of losing my job, ‘Call the news.’”[113]

“What Starvation Funding Does to an Institution” — Appointment of a Federal Monitor

Bach told Human Rights Watch that devastating funding cuts to NYCHA imperiled basic operations and led to large reductions in staff, both of which had grave impacts on staff performance and morale. He added that NYCHA went from “public housing that worked to public housing that was dysfunctional.” Staff, he said became “dispirited” and “demoralized,” and had “far less capacity to do what they had done decades before.”[114]

HUD regularly inspects the physical condition of public housing, using the Public Housing Assessment System (PHAS), which classifies PHAs as high-performing, standard, sub-standard, or troubled.[115] A PHA’s classification can have consequences. Low-performing authorities may receive less funding and be subject to administrative sanctions, including being placed into receivership by HUD.[116]

In 2018, the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) sued NYCHA, alleging that, since at least 2010, the Authority has systematically misled HUD during PHA inspections, underreporting a variety of critical issues, including lead paint, mold, lack of heat, and failing elevators. The SDNY’s complaint paints a picture of an institution in disarray that utterly failed to protect its residents from serious health hazards, alleging that NYCHA knew about widespread mold and the risks of lead poisoning, yet it failed to carry out required inspections. The complaint also charged that NYCHA developed protocols to hide such issues from PHA inspectors, including distributing a “Quick Fix Tips” guide, which directed staff on how to superficially cover up issues in buildings, and additionally that workers were not trained in lead-safe work practices and NYCHA manipulated the work order process to make it appear, falsely, that it was reducing its maintenance backlog.[117]

NYCHA admitted to these allegations as part of a settlement agreement which resulted in a federal monitor being appointed to oversee NYCHA’s efforts to remediate poor conditions in its buildings.[118] The monitor agreement also involved commitments by NYCHA to develop action plans to address issues concerning mold, heat, elevators, and lead based paint.[119]

“We are really talking about what starvation funding does to an institution,” said Bach. “You had buildings basically going through accelerated deterioration, mounting repair work orders, that nobody could do anything about.”[120]

As part of the settlement agreement, NYCHA committed to improving transparency and repair practices and has made various leadership changes.[121] The agreement also required the city to commit at least $2.2 billion in additional capital support between 2019 and 2028,[122] but without substantial additional funding, NYCHA, like other PHAs across the US, will continue struggling to ensure that residents enjoy safe and decent living conditions.

NYCHA did not respond to a letter from Human Rights Watch asking about living conditions, repair practices, and the effects of funding declines. NYCHA’s strategy for rehabilitating their public housing includes transferring its buildings out of the conventional public housing program, governed by Section 9 of the US Housing Act. NYCHA plans to transfer control of around a third of its housing (62,000 homes) to private entities through 99-year leases under a HUD program called the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD),[123] discussed in Section III. RAD allows PHAs to convert housing from Section 9 to Section 8 of the US Housing Act (a funding source typically utilized by private landlords), providing access to additional financing. However, research by Human Rights Watch and others have found that RAD can pose risks to residents’ rights.[124]

In addition, NYCHA is aiming to lease its remaining stock (around 110,000 homes) to a newly created public agency called the New York City Public Housing Preservation Trust, under a plan called the “Blueprint for Change.” Doing so would trigger special funding streams, which are normally used to enable tenants to find new housing when a PHA demolishes or disposes of public housing.[125] In this case, no apartments would be lost, and NYCHA would use the additional subsidy to leverage debt to finance repairs. According to NYCHA, under the Blueprint, existing public housing residents would not be displaced, and the housing would remain affordable.[126] As with RAD, NYCHA housing transferred to the public Preservation Trust would be governed by Section 8, rather than Section 9.[127]

In June 2022, the New York state legislature authorized the Blueprint but only permitted NYCHA to transfer 25,000 apartments to the Preservation Trust.[128] No apartments have been transferred as of this writing. Like conventional public housing, the funding sources required for the Blueprint depend on federal appropriations, and some tenant groups are concerned that the switch from Section 9 and the program’s reliance on debt could pose risks to resident rights and stability.[129]

Poor Housing Conditions in NRHA Buildings

Like NYCHA, the Northern Regional Housing Authority (NRHA) in New Mexico receives most of its funding from the federal government and is consequently impacted by declines in federal spending.[130] NRHA residents also described problems with management, as well as a staff culture that appeared to be unresponsive to tenant needs and may have compounded the impact of funding declines.

The NRHA is a regional housing authority, created in 2009, that operates public housing and administers vouchers in 10 counties in mostly rural northern New Mexico. [131] It has assumed responsibility for managing developments previously operated by various city, county, and smaller regional housing authorities in response to declines in federal funding and, in some cases, corruption scandals.[132]

Most of the tenants we interviewed described poor conditions remaining unfixed for months or years. In cases where residents’ homes were previously operated by a city or county housing authority, many described conditions being poor both before and after consolidation with the NRHA. Some of the issues described posed potential risks to residents’ health, including mold growth.[133] Residents described a number of other major issues, such as water leaks, warped floors, pest infestations, sinking foundations, and poor drainage outside apartments leading to repeated flooding.[134] For some residents, these conditions initially arose before NRHA consolidation, but have still not been resolved. In the latest round of HUD inspections, of the six NRHA properties inspected, four received failing physical condition scores, and five had “at least one life-threatening health and safety deficiency.”[135]

Sarah M. has lived in public housing for over 5 years and has children. Her apartment has severe mold growth, which has not been remediated for over a year. Human Rights Watch researchers observed what appeared to be serious mold growth in her home. Sarah reported several other serious issues with her home that she has been unable to have fixed and which may contribute to the mold growth, the details of which have been excluded to protect her anonymity. When she reports these issues to the housing authority, she says they are unresponsive. “They just keep saying, ‘We will get to you,’” a person familiar with Sarah’s situation said.[136]

Mateo S. told Human Rights Watch that, following a severe storm over three years ago, the roof of his public housing unit was damaged. The roof leaks when it rains but, he says, has still not been fixed. The leak has caused multiple other issues in his home, including mold growth and wall damage that caused his kitchen cabinets to collapse. The cabinets were never replaced, and workers only repaired the drywall behind where the cabinets used to be. Human Rights Watch observed water damage to this section of drywall, suggesting that the leak is still causing damage, and also observed mold growth in Mateo’s home.[137]

Many residents stated that it could take months or years for even seemingly basic tasks, such as replacing air filters and cleaning ducts for apartment heating systems, to be carried out, if they were done at all.[138] Daniel Crespin has lived in public housing in Las Vegas, New Mexico for 15 years. The City of Las Vegas Housing Authority consolidated with the NRHA in January 2021,[139] and, according to Crespin, maintenance has been poor both before and after the consolidation. He told Human Rights Watch that his home’s rain gutter was poorly installed, causing there to be a gap between the gutter and the edge of the roof. As a result, when it rains, water leaks into the house. The problem has gone unfixed over two years, despite Crespin reporting the issue. Crespin said that he has been dealing with unresponsive maintenance for years. “When I would make a work order, I asked them, ‘Can you let me know when [staff] are going to come?’ but they said no,” he said. “So I would stay waiting every day, over a week ... and they wouldn’t show up.”[140]

Descriptions of unresponsive maintenance are common. Catherine Parker, 65, has lived in public housing in Taos for seven years. The Taos County Housing Authority consolidated with the NRHA in August 2014.[141] Parker described numerous issues in her home, including mold and mildew growth, rusting fixtures, recurrent ant infestations, and a hole in her bathroom wall by her bathtub. These issues have remained unfixed, some for over year. She told Human Rights Watch that, even for minor repairs, maintenance is unresponsive: “It just takes them forever to come out here and do things,” she said. “It’s been reported and reported, and it’s been shown and shown and shown; I feel like a broken record.” She told Human Rights Watch that it took four years for her warped floors to be fixed. “I don’t expect things to be done right away; I understand that I’m not the only place,” she said. “But I expect a response; four years is ridiculous.” Human Rights Watch observed that her new floor tiles are beginning to warp, suggesting that the root cause of the problem may have not been fixed.

Some residents also stated that some basic repairs would only be completed immediately when HUD was due to carry out its own inspection.[142] “They were running around like chickens without a head,” one person told Human Rights Watch, describing NRHA staff installing essential safety equipment just days before HUD was due to inspect an apartment.[143] Parker similarly stated that the filters on her heating system were only changed immediately before a HUD inspection.