Summary

Since President John Magufuli came to power in 2015, Tanzania has seen a sharp backslide in respect for basic freedoms of association and expression, undermining both media freedoms and civil society. While some restrictive trends may have predated his term, they have intensified since he became president.

Authorities have passed new legislation and enforced existing laws that repress independent reporting and restrict the work of media, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and political opposition groups. The president and other high-level officials have made hostile statements about rights issues, at times followed by enforcement actions cracking down on individuals and organizations seen as being critical of government policy.

Authorities have censored and suspended newspapers and radio stations, arbitrarily deregistered NGOs, and have not conducted credible investigations into abductions, attempts on the lives of journalists and opposition figures. The government has arbitrarily arrested and, in some cases, brought harassing prosecutions against journalists, activists, and opposition politicians, perceived to be government critics.

Based on interviews with 80 people in July to September 2018, and in January 2019, this report documents these restrictions and abuses in both mainland Tanzania and the semi-autonomous island archipelago of Zanzibar, where Human Rights Watch researchers found a similarly repressive environment. Interviewees included reporters, newspaper editors and staff of NGOs in Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar, Arusha, Ilindi and Mwanza.

Over the past five years, the Tanzanian government has either enacted or begun to actively enforce repressive laws that undermine independent media, political opposition and civil society. These include the 2015 Cybercrimes Act, which restricts free expression online; the 2015 Statistics Act, which, until its amendment in June 2019, criminalized publishing statistics without government approval and blocked the publication and dissemination of independent research; 2018 regulations to the Electronic and Postal Communications Act that subject bloggers to excessive licensing fees; and the 2016 Media Services Act, which gives government agencies broad power to censor and limit the independence of the media by creating stringent rules for journalists accreditation and creating offenses and oversight powers that are open to abuse by the government. The government adopted new regulations in 2018 requiring NGOs to publicly declare their sources of funds, expenditures and intended activities or face deregistration. In addition, the 2002 Political Parties Act was amended in 2019 to restrict the space in which political parties can independently operate in Tanzania.

Authorities have stepped up censorship of the media. The Ministry of Information, Culture, Arts and Sports has shut down radio stations and newspapers and suspended live transmissions of parliamentary debates. In one case, the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority fined television stations for covering an NGO press conference critical of the government, and in another case a government official accompanied by armed security officers raided a television station.

The government has used the Cybercrimes Act to harass opposition politicians, journalists and activists, while police have arbitrarily arrested, and in some cases, beaten journalists as they covered events. Police have also arrested two journalists engaged in investigative reporting on government policy. Authorities have not adequately investigated the abduction of two other journalists, one of whom remains missing at the time of writing.

The government, through the NGO registrar, has exerted more control over NGOs by increasing bureaucratic requirements for NGOs and threatening to deregister them for non-compliance. All NGOs are now required to publicly disclose financial information and submit extensive registration documentation. Government officials have also threatened NGOs with deregistration over specific activities, for example, for challenging the president’s statements or for promoting LGBT rights. The NGO Coordination Board, under the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children, has deregistered three NGOs, for what it deemed to be violations of Tanzanian ethics and culture.

Police have raided events organized by groups working on protecting the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people, arbitrarily arresting individuals, and in one case detaining them for nine days, and deporting foreign participants. In some cases, after national or international researchers conducted research in Tanzania, the Commission on Science and Technology (COSTECH) retroactively asked them to obtain permits.

Government officials have sent threatening letters to or verbally warned Tanzanian NGO representatives against conducting activities. Regional and district commissioners have also subjected NGOs to restrictions on where they can carry out activities. Authorities have not adequately investigated bombings of two law offices. Immigration authorities, within the Ministry of Home Affairs, have raised questions about the nationality of those perceived to be government critics to both frustrate and silence them, in several cases, summoning individuals for questioning or seizing passports.

Political opposition parties in Tanzania have also faced various restrictions. In 2016 President Magufuli announced that elected politicians could not hold political rallies and meetings outside their constituencies, limiting the geographic area in which opposition parties could hold events. Since 2016, the government has arrested and charged several opposition party members for criticizing the government or the president. In September 2017, unknown assailants shot opposition parliamentarian Tundu Lissu, a prominent critic of Magufuli’s government, outside his home in the capital Dodoma. Immediately after the shooting, the government said it was investigating this assassination attempt, although there has been no arrest at time of writing. Within a fortnight in early 2018, unknown assailants killed Daniel John and Godfrey Luena, officials of the main opposition party Chadema.

The impact of repression is far-reaching, effectively silencing organizations promoting rights to health, women’s rights, children’s rights, access to education, LGBT rights and the rights of persons with disabilities, as well as those working on land, extractive industries, and electoral reforms. This report finds that the media are not covering the activities of these groups or the restrictions placed on them, for fear of government reprisals.

The Tanzanian government is obligated under its constitution and international and regional treaties to respect the rights to freedom of expression and association of all persons, including members of the media, civil society, and the political opposition. These rights are also essential to the exercise of the right to vote.

With just months to go before local government and general elections, scheduled for late 2019 and 2020 respectively, the government of Tanzania should do more to create conditions for a free and fair vote. This includes demonstrated commitment to the rights of freedoms of expression and association enshrined in the constitution and international and regional human rights treaties to which Tanzania is a party.

President Magufuli and other government officials should refrain from public rhetoric hostile to human rights issues and take proactive measures to reverse the patterns of repression that have caused Tanzanian civic space to close in recent years. Authorities should put a stop to arbitrary arrests, detention, and harassment of activists, staff of NGOs, and journalists, and embark on a range of reforms of repressive laws to proactively ease these chilling restrictions on civil society.

Recommendations

To the President of Tanzania

- Issue a clear and public statement to all government officials condemning and calling on them not to commit any intimidation, obstruction, threats, beatings, arbitrary arrests, harassment or prosecution of journalists, activists, representatives of NGOs, and political opposition members.

- Publicly condemn reports of violence against journalists, representatives of NGOs, and political opposition members.

- Take steps to ensure the credible and effective investigation of abuses against journalists, activists, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, and opposition politicians.

- Direct regional and district commissioners to refrain from arbitrary arrests and restrictions on the movement of representatives of NGOs, which limit their access to people residing within their jurisdictions.

- Direct the Immigration Department under the Ministry of Home Affairs to stop harassing representatives of NGOs and other activists through investigations into their citizenship.

- Direct the Ministry of Home Affairs to stop threatening punitive measures, including deregistration or deportation, against NGOs or their representatives, in retaliation for expressing positions divergent from those of the government, including regarding the rights of pregnant girls and the rights of LGBT people.

To the Directorate of Public Prosecutions and the Tanzania Police Force

- Effectively investigate and discipline or prosecute, as appropriate, government officials implicated in abuses of journalists, activists, NGO representatives, and opposition politicians.

- Effectively investigate and prosecute, as appropriate, individuals responsible for violence directed at journalists, activists, representatives of NGOs, and opposition politicians. This includes credibly investigating the abduction of Azory Gwanda, the shooting of Tundu Lissu, and the killings of opposition party members Daniel John and Godfrey Luena.

- Respect the rights of activists and NGOs to organize and hold meetings and carry out other activities.

To the Parliament of Tanzania

- Repeal or amend repressive sections of the Media Services Act, in accordance with the decision of the East African Court of Justice, the Cybercrimes Act, and the Electronic and Postal Communications (Online Content) Regulations.

To the Director of NGO Coordination under the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children

- Issue guidance to regional commissioners and district commissioners, to refrain from blocking NGOs from accessing their regions or districts and take other measures to ensure a conducive environment for nongovernmental organizations operating in Tanzania.

- Direct the NGO Coordination Board to review its April 2019 decision to deregister three NGOs for violating Tanzanian law, ethics and culture.

To the Ministry of Home Affairs

- Stop harassing representatives of NGOs and other activists through investigations into citizenship.

- Stop threatening punitive measures, including deregistration and deportation, against nongovernmental organizations or their representatives in retaliation for expressing positions divergent from the government’s, including on the rights of pregnant girls and the rights of LGBT people.

To the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and East African Cooperation

- Issue a standing invitation to the United Nations special rapporteurs on rights to freedom of expression, to peaceful assembly and association, the right to education, the situation of human rights defenders, the Working Group on the issue of discrimination against women in law and in practice, as well as the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights rapporteurs on freedom of expression and access to information, human rights defenders, and the rights of women, and the chair of the Committee on the Protection of the Rights of People Living With HIV to conduct on-site visits in Tanzania to assess the state of protection of human rights.

To the East African Community Member States

- Urge the Tanzanian government to fulfill its mandate to respect human rights under article 6 of the Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community.

To the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- Undertake a fact-finding mission to investigate human rights abuses, including repression and censorship, especially in light of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa.

- Request visits to Tanzania by special rapporteurs on freedom of expression and access to information, rights of women, and human rights defenders, as well as the chair of the Committee on the Protection of the Rights of People Living with HIV.

To UN Human Rights Council Member and Observer States

- Deliver statements, both jointly and individually, and engage in bilateral démarches, to address the ongoing deterioration of the human rights situation in Tanzania.

- Urge Tanzania to receive visits by UN Special Procedures mandate holders.

To the UN Special Procedures

- Request visits by special rapporteurs on rights to freedom of expression, to peaceful assembly and association, the right to education, and the situation of human rights defenders, and by the working group on the issue of discrimination against women in law and in practice.

To the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

- Urge the Human Rights Council to fulfill its mandate to respond to human rights violations in Tanzania, including gross and systematic violations, as set down in paragraph 3 of UN General Assembly resolution 60/251.

- Provide technical assistance for review of laws and regulations to ensure conformity with international rights standards.

To the European Union and its member states

- Publicly speak out, both bilaterally and in international fora, and in close coordination with likeminded countries and with members of the African Union, on the need for Tanzania to respect its regional and international obligations on free expression, free association and other fundamental freedoms, and to amend or repeal all abusive legislation, including the Media Services Act, the Cybercrimes Act, and the Electronic and Postal Communications (Online Content) Regulations.

- Urge the Tanzanian government to protect the rights of journalists, activists, political opposition and other civil society actors to free expression and association to ensure full implementation of the European Union’s guidelines on human rights defenders and on freedom of expression, taking all appropriate action as required.

- Resume the political dialogue with the Tanzanian authorities pursuant to article 8 of the “Partnership Agreement between the Members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of states of the one part and the European Community and its member states of the other part” (“Cotonou Agreement”), addressing human rights violations as a matter of priority, and reminding the Tanzanian government of the consequences foreseen by the Agreement in case of failure to respect human rights, democratic principles and the rule of law

- Urge the Tanzanian government to restore conditions for free and fair elections to take place in 2019 and 2020, and put the government on notice that, unless some defined benchmarks are met, the European Union will refuse to provide any form of electoral support to the country.

- Step up financial and political support to NGOs working specifically on advancing respect for civil and political rights in Tanzania.

To other international development partners,

- Publicly speak out on the need for Tanzania to respect its regional and international obligations on free expression, free association and other fundamental freedoms.

- Urge the Tanzanian government to protect the rights of journalists, activists, political opposition and representatives of NGOs or other civil society actors to free expression and association.

- Call on the Tanzanian government to review laws that impact free expression and association, including the Media Services Act, Cybercrimes Act, and the Electronic and Postal Communications (Online Content) Regulations.

- Promote and support independent monitoring of the human rights situation in the country, with a view to ensuring a conducive environment for holding free and fair elections, including by providing support to NGOs or other civil society actors working in this area.

Methodology

This report is based on research Human Rights Watch conducted in Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar, and Arusha between June 2018 and February 2019. In addition to interviews, researchers reviewed legislation, NGO reports, academic papers, newspapers and other media reports. The report also draws on some of Human Rights Watch’s previous research on Tanzania.

Researchers interviewed 80 individuals, including journalists, bloggers, lawyers, NGO representatives, and members of political parties. Additional telephone interviews were conducted with Tanzanians located at the time of the interviews in Lindi, Morogoro, and Mwanza in Tanzania, as well as Belgium, Kenya, and Sweden. Interviewees were selected from a cross-section of civil society, faith-based organizations, government officials, and the media through recommendations from Tanzanian civil society organizations.

Most interviews were conducted in English and lasted one to two hours. Some interviews were conducted in Tanzania’s official language Swahili and translated into English. Most of the interviews were conducted one on one, although a few were conducted with groups of two or three respondents. In addition to interviews, researchers reviewed legislation, NGO reports, academic papers newspaper and other media reports.

All interviewees gave oral consent and were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature and the goal of our research. No compensation or any form of remuneration was given to interviewees. Many of those who were interviewed expressed concern for their safety and as a result, we have not disclosed their names or other identifying details. All individuals who appear in this report with full last names are identified by their real names and affirmed that they were willing to have their names and the contents of their interviews published.

I. Background

Political and Legislative Systems in Tanzania and Zanzibar

The United Republic of Tanzania was formed on April 26, 1964 when Tanganyika and the island archipelago of Zanzibar were unified. This followed Tanganyika’s independence from Britain in 1961 and the Zanzibar revolution of January 12, 1964, when locals overthrew the sultan of Zanzibar. The country has a population of 57.31 million and is divided into 31 administrative regions or mikoa, which are sub-divided into districts, each administered by a district council. The president appoints commissioners for each region, district and city. The Regional Administration Act gives both regional and district commissioners broad and discretionary executive powers, including to arrest people suspected to have committed criminal offenses “within their presence” or “knowledge.” Regional commissioners act as representatives of the government in the regions in which they are appointed. [1] Similarly, district commissioners are government representatives responsible for, among others, “securing the maintenance of law and order in the district” and implementing government policy.[2]

The political and legal systems of Tanzania are divided into what are termed “union matters,” which concern the entire country, and those that concern either mainland Tanzania or Zanzibar alone. The central government of Tanzania is in charge of all union matters and of the mainland. The cabinet of the central government includes the vice president, the prime minister and the president of Zanzibar, Ali Mohamed Shein. Its Parliament, the National Assembly, has legislative power over union matters and mainland issues. Tanzania operates under a multi-party system, introduced in 1992. The current ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM, the “Party of the Revolution”) has held power since then, enjoying a large majority in the National Assembly. The main opposition party in mainland Tanzania is the Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (Chadema) which means the Party of Democracy and Development.

In 2012, the government embarked on a review of the existing 1977 constitution, during which citizens proposed either a three-government structure, resembling a federal state, constituting a federal government supervising the governments of Zanzibar and Tanganyika, or the complete secession of Zanzibar from mainland Tanzania.[3] The review has since stalled as President John Magufuli, in office since 2015, made it clear the review was not a priority for his administration. In November 2018, the president said his government would pursue development projects, adding: “Let’s work hard and stop thinking about a new constitution because my government will allocate no money for that purpose. The money we have will be used in implementing development projects.”[4]

While part of the union of Tanzania, Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous region of the country, composed of many small islands and two main ones – Unguja and Pemba. It has a population of just over one million people and its capital Zanzibar city, is located on Unguja. Its government has power only over matters on its islands; its Parliament does not deal with union matters, such as foreign affairs, citizenship and higher education. Some national legislation that impacts the rights to freedom of expression and association on mainland Tanzania do not apply in Zanzibar. These include the Media Services Act and the NGO Act of 2002. Some sections of the 2015 Statistics Act apply only to mainland Tanzania and other sections to Zanzibar while the Cybercrimes Act applies to both mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar, majorly with the exception of one section dealing with criminal procedure, which only applies to the mainland.

The Tanzania Police Force operates in both mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar.

The Zanzibar Police Division is a division of the larger Tanzania Police Force.[5] Both mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar have separate offices of the Director of Public Prosecutions, with each separately instituting, prosecuting and supervising all criminal prosecutions in their respective jurisdictions.[6]

2015 Elections and Aftermath

Magufuli was elected at a time when Tanzania was working toward achieving the “Vision 2025” goal of attaining middle income status, which was formulated and adopted in 1999 during the government of former president Benjamin Mkapa. Vision 2025 sets out aspirations for increased livelihoods and economic growth for the country.[7] Observers initially highly lauded Magufuli for working toward this goal through his aggressive campaign against corruption and prioritizing economic and infrastructural development of the country.[8] The high praise soon gave way to serious concerns as his government embarked on the pattern of repression of the media, political opposition, and civil society broadly, described in this report.[9]

Following presidential elections in October 2015, Magufuli defeated Edward Lowassa, the candidate of a four party coalition called Ukawa, winning 58 percent of the votes to Lowassa’s 40 percent.[10] Election observers, including the African Union, the Southern African Development Community, the United Kingdom and the European Union, generally applauded the elections, but raised concerns when the Zanzibar Electoral Commission (ZEC), citing electoral fraud, called for a re-run of the Zanzibar presidential elections, which had taken place at the same time.[11] The United Kingdom disagreed with this decision and called on the ZEC to “resume the results tabulation process without delay.”[12] Nonetheless, the ZEC continued with the re-run.

In March 2016, CCM candidate Ali Mohamed Shein, won 91.4 percent of votes during the re-run of the presidential elections in Zanzibar. The re-run was boycotted by Zanzibar’s main opposition party, the Civic United Front (CUF). CUF labelled the elections “illegal.”[13] During the re-run, according to media reports, Zanzibar authorities arrested opposition members and banned public rallies.[14] As detailed below, they suspended radio stations, according to the Media Council of Tanzania .[15] In at least one case, unknown men abducted and threatened a Zanzibar-based journalist for covering the 2016 re-run elections.[16]

Hostile Rhetoric on Human Rights

A hallmark of Magufuli’s presidency has been moralistic rhetoric hostile about a range of human rights issues, followed in some cases by enforcement actions by government officials. His administration has suspended activities of some NGOs and threatened to deregister others in retaliation for criticizing his statements.

On June 22, 2017, Magufuli said, “As long as I’m president, no pregnant students will be allowed to return to school.… After getting pregnant you are done,” threatening the rights to education and equality of pregnant girls.[17] Three days later, Home Affairs Minister Mwigulu Nchemba threatened to deregister any organizations that challenged the president’s statements.[18] In December 2017 and January 2018, Tanzanian police arrested school girls for being pregnant.[19] Girls have also been subjected to forced pregnancy tests and examinations in schools.[20]

In September 2018 in a speech in Meatu, in the northern Simiyu region, the president denounced family planning, asking women to give up using contraception, adding that “people should work harder to provide for their families.” [21] He also said that “those going for family planning are lazy ... they are afraid they will not be able to feed their children. They do not want to work hard to feed a large family and that is why they opt for birth controls and end up with one or two children only.” [22] Later that same month the government suspended radio and television advertisements encouraging family planning.[23] It later subjected them to new guidelines, including a requirement that they be submitted to and approved by a government committee before being aired.[24]

Magufuli and other government officials have vehemently denounced the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people. In 2017 the president said “even cows” disapprove of homosexuality.[25] The government has, since 2015, cracked down on LGBT people and their advocates by banning civil society organizations from conducting HIV prevention activities for gay men.[26] It has prohibited the distribution of water-based lubricant for HIV prevention and raided meetings on health and human rights organized by LGBT-rights activists.[27] Police have arrested people based on their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity, while also subjecting some of those arrested to forced anal exams, a form of cruel and degrading treatment that can rise to the level of torture. [28]

In June 2017, Home Affairs Minister Nchemba also threatened to deregister organizations that support and campaign for homosexuality and arrest individuals and deport foreigners involved in them.[29] In November 2018, Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner Paul Makonda announced plans to round up suspected gays and subject them to forced anal examinations and conversion therapy.[30] Following this, the Foreign Ministry publicly denounced this announcement in a statement. [31] Makonda’s proposed mass roundups did not take place although other arrests of suspected gay men continued to take place in northern Tanzania and in Zanzibar.[32] See further discussion of the crackdown on individuals and organizations that work to uphold the rights of LGBT people in section III below.

In July 2018, while swearing in a new Commissioner General of Prisons, Magufuli criticized the country's prisons service for allowing inmates to "sleep," that they should be made to work “day and night,” that prison authorities should end conjugal visits and that the lazy be “kicked.” [33]

The administration has also threatened protesters. On March 9, 2018, Magufuli said his government would crack down on demonstrations it considers illegal.[34] When US-based Tanzanian activist Mange Kimambi called for nationwide anti-government protests on April 26 the regional police commander for the centrally located Dodoma, Gilles Muroto told journalists that protesters “will seriously suffer” and would be “beaten like stray dogs” if they participated.[35] Nationwide demonstrations were not held, although police arrested nine demonstrators in Dar es Salaam.[36]

Media and Civil Society Landscape

Tanzania’s media is mostly concentrated in the country’s former capital and largest city, Dar es Salaam. Print media is dominated by Mwananchi Communications Ltd, a subsidiary of Nation Media Group. Mwananchi Communications publishes in English-language, The Citizen and in Swahili, Mwananchi. State run newspapers include Habari Leo, Daily News and SpotiLeo, while the IPP Media Group publishes The Guardian.

Broadcast media varies by region although state-run radio and television stations, as well as the privately-owned Clouds Media, Azam Television and IPP Media Group all contest for space across the country.[37] In 2016, the government banned live broadcasts of parliamentary sessions.[38]

Online media – including privately run blogs and web forums – have increasingly gained more prominence over the years. Jamii Forums, has over 500,000 members according to its website.[39]

Civil society, understood to mean groups working outside the framework of the state to pursue a specific cause, includes various types of charity organizations and NGOs, according to one study.[40] While in principle independent of the government, NGOs are registered and regulated by the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. The NGO Act of 2002 established a 10-member NGO Coordination Board to register NGOs and has the power to suspend or deregister them. Members of the board are appointed by the president or the Minister of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children.[41]

Both media and civil society play a critical role in promoting and advancing human rights in Tanzania. Both have the potential to create awareness about rights and expose violations. This role is further enhanced where they are independent.

II. Restrictions on Expression

I don’t see any freedom of expression in this country. If you utter any word about things that are not implemented or things that are not good, then you have a problem. We can’t all be government spokespersons. You praise the government when need be. You praise depending on what has been done but not all the time because no one is perfect.

Jack F., director of a Dar es Salaam-based NGO, Dar es Salaam, August 2018

Media laws

Since 2015, the Tanzanian government has enacted new legislation or started enforcing existing laws that curtail the right to freedom of expression. The Cybercrimes Act of 2015 criminalizes offenses related to computer systems and electronic devices and has been used to prosecute individuals for posts they have made online, as described below. The Statistics Act of 2015, also described below, regulates the publication of statistics in Tanzania, and, until Parliament amended it in June 2019. It criminalized publishing and disseminating independent statistics.

The 2016 Media Services Act regulates the media industry and journalism profession. It gives government agencies broad powers to censor the media and limit independent journalism. It requires journalists to be accredited by the government and creates broad and unclear criminal offenses that are open to abuse by the government, such as the publication of statements which threaten “the interests of … public order” or “public morality.” [42] The law also gives broad oversight to the director of information services, including the power to unilaterally suspend or cancel newspaper licenses.[43] The government has used this law to suspend newspapers .

The law has been widely criticized by civil society groups for restricting media operations. Twaweza, an organization that analyzes Tanzanian law and policy, described it in November 2016 as a “step backwards for free and independent media” in Tanzania.[44] In 2017, a coalition of human rights organizations and media practitioners challenged the act at the East African Court of Justice, the judicial body of the East African Community, of which Tanzania is a member. They argued that the law violates freedom of expression by restricting news content without justification. On March 18, 2019, the court held that the law violated the treaty establishing the East African Community and called on the Tanzanian government to amend it.[45] The court found that several sections of the law violate the East African Community Treaty’s sections on good governance, principles of democracy, and protection and promotion of human rights. [46] These include sections relating to the definition of journalists, criminal defamation, publication of “false statements” and acting with “seditious intent,” and sections that empower the minister to prohibit the import of a publication he or she deems “contrary to public interest” or to sanction any publication that jeopardizes national security or public safety. Following this decision, government officials reportedly expressed openness to dialogue on reviewing the law.[47]

The Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) is a quasi-independent government body established in November 2003 with responsibility for regulating the communications and broadcasting sectors in Tanzania. In 2018 it was given wide discretionary powers to license blogs, websites and other online content through the adoption of regulations in 2018. [48] Bloggers are required to pay fees of up to 2,100,000 Tanzania shillings (US$900) according to a schedule published in 2018, to acquire an operating license from TCRA, an amount many bloggers would struggle to raise. Non-compliance with this law is a criminal offense, making it a crime to run a blog or website without a TCRA license. [49]

Following the adoption of these regulations, authorities in June 2018 ordered bloggers to apply and pay for licenses to run their websites.[50] An individual who ran blogs and websites told Human Rights Watch that they elected not to apply for the license because they could not afford it.[51]

Statistics Act

Tanzanian authorities have also used a law coordinating statistics to restrict civil society groups and the media. In 2015, Parliament passed the Statistics Act which made it a crime for owners of radio stations, newspapers, websites or other media to publish what were termed “false official statistics,” that is statistics that were not approved by government agencies, notably the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).[52] It also made it a crime to publish statistics that “may result in the distortion of facts.”[53] The law did not define the distortion of facts.

Authorities have used this law to restrict and instill fear in civil society, government critics and the media. In 2017, police arrested opposition politician Zitto Kabwe for violating the Statistics Act for remarks he made about the economic growth of Tanzania.[54] Kabwe was released without charge and has not heard further from the authorities in this matter. He told Human Rights Watch that the police said to him, “we will call you.”[55] In September 2018, Parliament adopted an amendment to the law making it a crime to publish any statistics at all without NBS approval and prohibiting the dissemination of statistics that are meant to “invalidate, distort or discredit” the body’s statistics.[56]

The World Bank criticized the new amendments to the 2015 Act for being out of line with “international standards such as the UN Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics and the African Charter on Statistics.”[57] In November 2018, the World Bank’s vice president for Africa, Hafez Ghanem, said: “[W]e need statistics that are reliable and credible because all our decisions and analyses as World Bank, are based on statistics.”[58]

In June 2019, Parliament passed an amendment making several improvements to the act. The amendment provided that every person has a right to collect and disseminate statistical information, including information different from that of the NBS. It also notably removed the criminal offense of publishing independent statistical information. It established a five member “Statistical Technical Committee” to whom NBS may refer statistical information disseminated by any other person that it disagrees with to make a “determination.” [59]

Cybercrimes Act

Parliament enacted the Cybercrimes Act in April 2015. The law criminalizes a series of activities related to computer systems and Information Communication Technologies and “provides for investigation, collection, and use of electronic evidence.”[60] The law prohibits the publication of false information on a computer system “knowing that such information or data is false, deceptive, misleading or inaccurate, and with intent

to defame, threaten, abuse, insult, or otherwise deceive or mislead the public.”[61] The government has used this law to prosecute individuals for posts made online and through internet-based communications, described below.

Bans, Shutdowns, Raids and Fines

Since 2015, the Tanzanian government has banned or suspended newspapers and radio stations, raided them, or fined them, for publishing or broadcasting content deemed critical of the government.

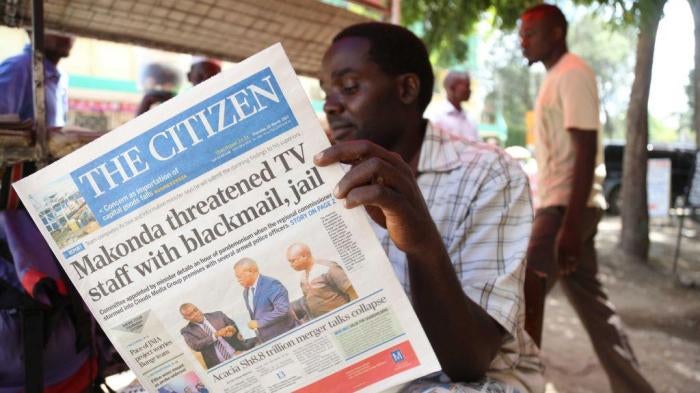

In February 2019, the Department of Information Services under the Ministry of Information, Culture, Arts and Sports suspended Tanzania’s major English language newspaper, The Citizen, for seven days under the Media Services Act.[62] The newspaper had published two articles, one about US lawmaker, Bob Menendez, raising concerns about “the gradual downward spiral of respect for civil liberties in Tanzania” and another reporting that the Tanzania shilling was falling against the US dollar. The department said the articles were one sided.

In 2017, the Department banned four other newspapers using the Media Services Act. Mawio was banned after publishing an article which linked former presidents with controversial mining contracts; Tanzania Daima was banned for “continuous publication of false information” after it published an article claiming that 67 percent of Tanzanians use anti-retroviral drugs; Mwanahalisi was banned for two years over allegations that it tarnished the presidents name; while Raia Mwema was banned following the publication of an article titled “Magufuli presidency likely to fail.”[63]

In Zanzibar, the Zanzibar Broadcasting Commission shut down a radio station, Swahiba FM, in October 2015, as it reported on the annulment and subsequent re-run of the 2015 elections.[64] The radio station aired an announcement by opposition party Civic United Front leader, Sharif Hamad, that he was the winner of the presidential elections.[65] The radio station later apologized to the Zanzibar Broadcasting Commission and was allowed to resume broadcasting in January 2016.[66]

On Friday, March 17 2017, the Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner Paul Makonda stormed the offices of private media company Clouds Media with armed security officers to force staff to broadcast a video on television.[67] The following Monday, Nape Nnauye, the Information, Culture, Arts and Sports minister visited Clouds Media and condemned the incident saying, “There is every indication that some politicians lack tolerance, which is a key component of leadership…there are people who think that they are above the law.” He also announced that a team was formed to investigate the incident and would present findings at a later press conference. [68] However, three days later, according to media reports, President Magufuli, who had reportedly voiced support for Makonda’s actions, fired Nnuaye, without citing any reason. [69] On the same day Nnauye was fired, a plain-clothed man held him at gunpoint in the parking lot of a Dar es Salaam hotel as he attempted to hold a press conference, in an apparent attempt at blocking him from speaking to the media. [70] No arrests for this were made.

In 2015, gunmen on two occasions raided private Zanzibar radio stations that had aired content critical of the government following the re-run of the 2015 presidential elections. In one incident, the Media Council of Tanzania reported that on the morning of June 29, 2015, about 20 armed, masked men attacked Coconut FM and threatened its staff after it aired a discussion critical of the voter registration procedure for the then forthcoming elections.[71] On December 3, 2015 masked, armed men raided Hits FM and destroyed property including cameras and recording equipment, and set the station on fire.[72] Hits FM had invited a government critic on air prior to this. [73]

Simon Q., who witnessed the raid on Coconut FM with told Human Rights Watch that these men wore masks, head covers and military fatigues, which gave him the impression that they could have been members of “Mazombi” a government aligned militia group.[74] In the raid on Hits FM, a witness reported that they warned the radio station to not broadcast information critical of the government.[75]

Authorities, on one occasion, fined media for airing content with which they apparently disagree. In Dar es Salaam, in January 2018, the TCRA used its wide discretionary powers under the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority Act of 2003 to fine five television stations a total of 60 million Tanzania shillings (about $27,000) for broadcasting a press conference by an NGO, the Legal and Human Rights Centre (LHRC).[76] LHRC alleged during the press conference that government forces, with other unidentified groups, arrested, detained, tortured and abducted opposition members during November 2017 by-elections in different parts of the country.[77] The regulator argued the content was “seditious” and contrary to the Broadcasting Services (Content) Regulations.[78]

Arbitrary Arrests, Prosecutions, and Beatings

Section 16 of the Cybercrimes Act of 2015 criminalizes the publication of “false information” online with knowledge that the information is false and with intention to deceive the public. On March 15, 2016 Bob Chacha Wangwe, a human rights activist and law student at the University of Dar es Salaam, posted a message on Facebook criticizing Tanzania’s relationship with Zanzibar, and calling it a colony of the mainland. In November 2017, a Dar es Salaam court convicted him for publication of false information under section 16 of the Cybercrimes Act and sentenced him to 18 month’s imprisonment or a fine of 5 million Tanzania shillings (about $2,185). [79] He appealed the conviction on the grounds that the prosecution had failed to prove their case against him. On March 27, 2019 the high court in Dar es Salaam upheld Wangwe’s appeal against his 2017 conviction.[80]

On December 13, 2016, police arrested Maxence Melo, a prominent human rights defender and the owner of Jamii Forums, an independent whistleblower and reporting website, and Micke William, a shareholder of Jamii Media, which hosts the site. Police reportedly searched the offices of Jamii Forums and Melo’s home and made copies of several documents.[81] Melo’s lawyer told the media that police conducted the search without a warrant.[82] On December 16, 2016, a Dar es Salaam charges were brought against Melo and William including obstruction of investigations for refusing to reveal the names of anonymous contributors to Jamii Forums, and “managing a domain not registered in Tanzania,” according to the charge sheet that Human Rights Watch has seen.[83]

Their trial began in August 2017. In June 2018, the court acquitted Melo and William of the charges of failure to comply with a police order to disclose the identity of platform users under the Cybercrimes Act.[84] Two remaining charges -- of management of a domain not registered in Tanzania under the Online Content regulations, and of obstructing investigation under the Cybercrimes Act -- remain pending at time of writing.

In March 2018, student activist, Abdul Nondo was charged with publishing false information under the Cybercrimes Act after he sent a WhatsApp message alerting friends and family that he had been abducted. Nondo told Human Rights Watch that three unknown men followed and forced him into a car as he walked to visit a relative at night on March 6, 2018. His abductors then questioned him about his political ideologies and his affiliation with US-based activist Mange Kibambi and accused him of being used by opposition parliamentarians and activists to organize student protests. During a press conference earlier that year, Nondo had criticized police abuses at a February rally in Dar es Salaam in which a student was killed; he called for students to demonstrate.

As his abductors drove him to an unknown destination, Nondo wrote a message to a friend on his cellphone saying, “Am at risk.” After a few hours his captors dumped him in Mafinga, a town in Iringa district 560 kilometers from Dar es Salaam. Nondo reported his abduction to police at Mafinga police station but he told Human Rights Watch that they immediately accused him of fabricating his story because he did not appear to have injuries:

All of [the police] turned against me [and said] that I was cheating, and I gave false information. […] They said they realized I am used by politicians to spoil the image of the government and I should be with them for further investigation. [85]

The police detained Nondo and transferred him the next day to Dar es Salaam where he was held without charge for two weeks before being released on bail. He was eventually charged with publication of false information under the Cybercrimes Act, for sending his friend the “Am at risk” text, as well as for allegedly giving false information to a person employed in the public service contrary to the penal code when he reported his abduction to the police.

Nondo told Human Rights Watch that he was beaten and slapped, while being interrogated by police for up to 12 hours every day during his detention. During his trial, according to Nondo, immigration officials also summoned him to provide proof of his Tanzanian citizenship. [86] On November 5, 2018 the magistrates court of Iringa acquitted Nondo of both charges. [87]

Authorities have also arrested and, at times, beaten journalists while they are covering events, releasing those arrested without charging them with any crime. In May 2017 police arrested 10 journalists covering the deaths of 35 people, including 32 school children from Lucky Vincent school in Arusha, who were killed when a bus they were travelling in crashed into a roadside ravine in Karatu, Arusha, on May 6.[88] Police arrested the journalists, from various media houses, alongside several others including local officials, at a ceremony to pay respects to the families of the students. The acting Arusha Regional Police Commander Yusuph Ilembo said police arrested them “for holding an unlawful meeting.”[89] The police detained the journalists and others at the police station ,and, after a few hours released the journalists without charge.[90] One of the journalists told Human Rights Watch that they were forced to kneel at gunpoint when they were arrested.[91]

On August 8, 2018, police arrested journalist Sitta Tumma in Tarime district in north Tanzania, as he reported on police dispersing an opposition rally. Tumma was initially covering the campaign rally held by a Chadema candidate in by-elections in the district. Police announced they had cancelled the rally and were attempting to disperse the crowd.[92]

Tumma told Human Rights Watch that as he was covering the unfolding events and took pictures of police arresting Chadema parliamentarian Esther Matiko, policemen ran toward him. He identified himself as a journalist by showing them his ID, but they still arrested him and threw him in the back of a waiting police pick-up, while taunting him and attempting to take his camera: “They continued to kick me on the back and the waist, and they were making fun of me. They wanted to take the camera but I wouldn’t let it go.”[93] Tumma was detained overnight and released but not charged.

In Dar es Salaam, at a football match at the Tanzania National Stadium on the same day of Tumma’s arrest, anti-riot police beat Silas Mbise, a radio sports reporter, covering the event. Mbise later told the media that the police officers targeted him after he challenged them for blocking himself and other journalists from accessing the event.[94] The beating was caught on video seen by Human Rights Watch, as he lay on the ground with his hands in the air. Police said the beating was justified because Mbise had “failed to follow police orders.”[95]

On July 29, 2019, six plain-clothed policemen arrested high-profile investigative journalist Erick Kabendera from his home in Dar es Salaam, also taking his and others’ passports.[96] The next day police confirmed that they were holding him to determine his citizenship.[97] On August 5, however, during a bail hearing, prosecutors charged him with non-bailable offenses related to money laundering, tax evasion and leading organized crime that they claimed he committed between January 2015 and July 2019.[98] Kabendera had written for several international publications critiquing Tanzanian politics, including The East African, The Guardian and The Times of London. His most recent article prior to his arrest had been published on July 27 in The East African and reported on possible internal divisions within CCM ahead of the 2020 presidential elections.[99] His lawyer claimed that he was arrested because of his work.[100] At time of writing, Kabendera was still detained.[101]

On August 22, 2019 police detained journalist Joseph Gandye in Dar es Salaam following a police summons. Gandye, a production and associate head at Watetezi TV, an online channel established by the Tanzania Human Rights Defenders Coalition (THRDC), published an investigative piece on police brutality at the Mafinga police station in Iringa in central Tanzania on August 9, 2019. Police told the Committee to Protect Journalists that the journalist was “being questioned to clarify discrepancies between his reporting and medical reports into the detainees.”[102] On August 23, the police released Gandye without charge and at the time of his release told him to report back to the police twice.[103]

Abductions

Human Rights Watch research indicates that Tanzanian authorities have not conducted adequate investigations into the abductions of two journalists.

In March 2016 unknown men abducted Zanzibar-based journalist Salma Said at Julius Nyerere International Airport in Dar es Salaam, two days before the re-run of presidential elections in Zanzibar. Said told Human Rights Watch that she had previously received telephone calls from unknown people telling her not to report on the forthcoming elections. She reported the calls to the police but said that they were dismissive of her report and told her to “just go.” [104]

Fearing for her safety, Said traveled to Dar es Salaam on March 18, where three men grabbed and forced her into a car at the airport. They covered her face and drove her to an unknown location where they beat, threatened to kill her, and asked her why she was reporting on the elections. On March 20, the men dumped her in the same place from which she was abducted. Said told Human Rights Watch that since her attack, she has struggled with her memory due to being beaten on her head. [105]

In November 2017, Anna Pinoni reported to police that her husband, freelance journalist Azory Gwanda, was missing. She told the media that he was been picked up from their home in Kibiti, 140 kilometers south of Dar es Salaam, by people in a white vehicle.[106] At the time, Gwanda had been investigating a spate of unresolved killings in the southern Pwani region.[107] At time of writing, authorities had failed to provide answers. In July 2017, Home Affairs Minister Kangi Lugola appeared to characterize Gwanda as having gotten lost, disclaiming any responsibility to investigate such cases.[108]

III. Restrictions on Civil Society Organizations

The president is anti-civil society organizations. For him CSOs are his enemies, especially the human rights organizations, because when he goes contrary to the human rights principles, we normally tell him. So now he is working very hard to silence these. [109]

Edward R., activist, Arusha, February 2019

Bureaucracy and Restrictions on Movement

Authorities have enacted many restrictions on how civil society organizations operate.

The NGO sector was previously governed by the NGOs Act of 2002, NGO Regulations of 2004, which implemented the act, and a 2001 national NGO policy. In August 2017, the administration of President Magufuli suspended the registration of new NGOs when it began a verification exercise for existing NGOs. [110] As part of this process, the government required NGOs to submit a letter from the region, district or municipality the organization was registered in to confirm its existence as well as a copy of the NGO's constitution, certified by the registrar of NGOs at zonal offices. NGOs that failed to comply in the exercise were threatened with deregistration, although Human Rights Watch is unaware of the government deregistering any NGOs as a result. [111]

Following this, in 2018, the 2004 NGO regulations were amended to introduce new financial and accountability requirements for NGOs. The new regulations made it mandatory for NGOs to publicly declare sources of funds, as well as expenditures and activities they intend to undertake within 14 days of obtaining such funds, under threat of deregistration.[112] NGO workers told Human Rights Watch that authorities were not receptive to feedback on the new regulations during consultative meetings before they were passed.[113] In 2019, Parliament proposed an amendment to the NGOs Act to give the registrar of NGOs the power to suspend the operation of organizations operating contrary to the provisions of the Act.[114]

Regional and district commissioners have used their wide executive powers to arbitrarily block NGOs from accessing people residing within their jurisdictions. Several NGO representatives interviewed in Dar es Salaam and Arusha told Human Rights Watch that they are not allowed to travel to communities without the permission of district or regional commissioners.[115] An NGO worker in Arusha described an experience where their organization attempted to implement a project in another district 350 kilometers away:

We paid a courtesy visit to the district commissioner and from there things changed. They said we need a permit to go to the location of our project. He said, “Does the regional commissioner know about this?” And we were supposed to travel about 80 kilometers to seek for the permits [from the regional commissioner]. Now at the regional commissioner’s office they said we need to get a permit from the Ministry of Local Government in Dodoma. The regional commissioner’s office is in Tanga. Dodoma is about 469 kilometers away and Arusha is like 300 kilometers away. This is really a complication.[116]

In another case, NGO workers said authorities required the organization’s staff to be accompanied by a government official when conducting activities, despite there being no such requirement in the law. [117]

In April 2019, authorities at Julius Nyerere International Airport in Dar es Salaam detained and eventually deported Wairagala Wakabi, director of a regional organization, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA). Wakabi was planning to attend a human rights event organized by the Tanzania Human Rights Defenders Coalition where CIPESA was set to receive an award for its work on protecting human rights online.[118]

Research Permits and Immigration Status

Authorities have also drawn on existing regulations that apply to research permits and immigration visas to prevent some groups from operating.

On November 14, 2017, government officials from the Commission on Science and Technology (COSTECH) and the Ministry of Home Affairs prevented Human Rights Watch from holding a news conference in Dar es Salaam to launch a report on the abuse of Tanzanian migrant domestic workers in Oman and the United Arab Emirates. COSTECH was established in 1986 through an Act of Parliament to monitor and coordinate scientific research and technology development.[119]

Six officials—two officials from COSTECH and four from the Home Affairs Ministry—arrived at the press conference venue an hour before it was due to start and demanded its cancelation because they claimed Human Rights Watch did not have a permit to conduct research. Both the COSTECH and the two Human Rights Watch staff that were present at the time gave statements to the press about the closure of the press conference. Willium Kindekete of COSTECH said that the event was blocked because the visas of Rothna Begum and Audrey Wabwire, the two Human Rights Watch staff members, “do not identify them as researchers, but just visitors; so they aren’t allowed to work in the country.”[120] However, Begum and Wabwire entered Tanzania on valid business visas and entry permits. In addition, on the day of the event when demanding its cancellation, the officials did not request to examine their passports and had insisted only that they needed research permits to conduct research. They also gave inconsistent information on what approval would be required to hold the press conference.

Later that day, Begum and Wabwire met with a senior research officer from COSTECH and presented all the letters Human Rights Watch had sent government officials over the previous year. The official claimed that COSTECH not only provides approval for research but has to review research findings before allowing it to be disseminated.[121]

At the outset of research for the report in 2016, and in the lead up to the launch of the report in 2017, Begum met with senior government ministry officials with the approval from their respective permanent secretaries at the labour, home affairs, and foreign affairs ministries in Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar. Human Rights Watch wrote to all relevant ministries and maintained contact with officials over the course of the research period.[122] During these meetings none of the officials suggested there were any issues with Human Rights Watch’s presence and expressed interested in the report findings.

On November 15, Human Rights Watch met with a Foreign Ministry official to discuss the findings of the report and raised the issue of the cancellation of the press conference. On December 1, 2017, Human Rights Watch wrote to the minister of foreign affairs to relay its concerns about the shut-down of the press conference but did not receive a response.[123]

On July 11, 2018, COSTECH contacted the organization Twaweza regarding the publication of a report on its survey, Sauti za Wananchi or “Citizens Voices,” saying they were not given a permit to conduct the survey. The survey indicated that President Magufuli’s public approval rating had dropped significantly in 2018. Thereafter, immigration authorities seized the passport of the director of Twaweza, Aidan Eyakuze, barring him from leaving the country, pending an investigation into his Tanzanian citizenship.[124] Authorities have similarly challenged the citizenship of several other NGO representatives and journalists, as described below.

In another example involving foreign researchers, on November 7, 2018, authorities in Dar es Salaam detained two staff of the international NGO Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Angela Quintal, Africa program coordinator and Muthoki Mumo, its sub-Saharan Africa representative. Officers identifying themselves as immigration officials initially questioned, then arrested the pair at their hotel at about 9 p.m. According to CPJ, the officials looked through their belongings, confiscated their passports, and drove them to a house at an unknown location where they were detained and interrogated overnight. Officials questioned them about who they had met, what they were researching, and why they were in Tanzania. Quintal told Human Rights Watch that the officials were particularly interested in discussions the two had with local organizations about Azory Gwanda, a journalist who had gone missing in 2017 while investigating troubling reports of killings in the Pwani region, as discussed above.[125]

The CPJ said their staff members were on a fact-finding mission and that they had legal permits to visit the East African nation.[126] Authorities later said Quintal and Mumo had violated their entry requirements in the country by “holding meetings with local journalists and that’s contrary to the conditions of their entry permits.” The officials released the two CPJ staff the following morning, returned their passports, and encouraged them to acquire proper visas the next time. [127]

Deregistration and Threats to Deregister and Suspend

As discussed above, authorities threatened to deregister NGOs in Tanzania for failing to comply with the complex requirements introduced during the review of the national NGO policy in 2017.

While such threats became less common after the government completed reviewing the national NGO policy, two NGO workers in Zanzibar told Human Rights Watch that organizations there continue to face threats of deregistration or suspension especially those working on issues the government considers politically-sensitive, including extractive issues, the rights of people with albinism, land, civil and political rights, as well as the rule of law.

Whenever you address the issues of rule of law and governance, they are termed and labeled ‘political activities.’ I say I’m trying to be a good citizen. But when you talk about these things, you won’t receive a lot of support and even some officials will not want to associate with you. [128]

In 2017, the Minister for Constitutional Affairs and Legal Affairs Harrison Mwakyembe, threatened to ban the Tanganyika Law Society, the association for lawyers based in mainland Tanzania, for allegedly engaging in politics.[129] His statements came amidst a campaign by opposition parliamentarian and lawyer, Tundu Lissu, to run for presidency of the association. While Mwakyembe’s remarks were widely criticized, Parliament passed an amendment to the Tanganyika Law Society Act in 2018 prohibiting individuals who are public servants, ward counsellors, members of parliament, and leaders of a political party from election to the law society’s governing body and prohibiting members of the governing body from engaging in a wide range of “political activities,” a violation of their rights to freedom of association and expression.[130]

On June 25, 2017, as noted above, Home Affairs Minister Mwigulu Nchemba threatened to deregister organizations that spoke out against the president’s controversial June 22 statement banning pregnant girls and teen mothers from attending school, to arrest activists working to “protect homosexual interests,” deregister their organizations, and to prosecute or deport foreigners working to protect rights of LGBT people. [131]

In October 2017, following a raid described below of a workshop organized by an NGO, the Community Health Education Services & Advocacy (CHESA), an organization working to protect sex workers’ rights in Tanzania, and the Initiative for Strategic Litigation in Africa (ISLA), a South Africa based pan-African organization advancing women’s and sexual rights, the government suspended CHESA “to enable the conduct of the investigation into allegations involving the organization in the promotion of marriages between persons of the same sex.”[132]

In April 2019 the NGO Coordination Board deregistered CHESA, Kazi Busara na Hekima (KBH Sisters), and AHA Development Organization Tanzania based on claims that they violated Tanzanian law, ethics and culture.[133]

Raids and Arbitrary Arrests

Tanzanian authorities have arrested members of civil society groups and individuals working on a range of topics, at times during raids on NGO offices or activities, and, in one case, brought criminal charges against NGO representatives in apparent retaliation for their work. The most significant crackdown has been on individuals and organizations that work to uphold the rights of LGBT people.

An LGBT activist told Human Rights Watch that police arrested him in 2016 in southwestern Tanzania, accusing him of “promoting homosexuality”, which is not a crime in Tanzania, while he conducted access to health services activities with his organization. The police released the activist the next day after he was forced to pay a bribe.[134]

In August 2016, police raided CHESA, searching for water-based lubricants and confiscating copies of a shadow report that 15 organizations working on LGBT rights had submitted for Tanzania’s Universal Periodic Review at the UN Human Rights Council.[135] A series of police raids on meetings and workshops organized by groups working on LGBT rights followed. This included a December 14, 2016 raid on a meeting in Dar es Salaam (on sexual and reproductive health programming convened for Tanzanian organizations providing services to key populations, including sex workers and men who have sex with men. Police arrested eight participants and took them to the central police station for interrogation. They were released the same day without charge, but police summoned four Tanzanian participants for follow up questioning several times after this.[136]

On September 15, 2017 police raided a workshop in Zanzibar, hosted by local organization Bridge Initiative Organization (BIO) on parent involvement in HIV prevention and support for family members from at-risk populations, including gay men, claiming BIO was promoting same sex relationships.[137] Police detained 20 people for several hours but released them later the same day.[138]

In October 2017, police raided a meeting co-hosted by CHESA and the South-Africa based ISLA, which aimed to explore the possibility of mounting legal challenges to the government’s ban on drop-in centers serving key populations at risk of HIV and the ban on importation of water-based lubricants. [139] Dar es Salaam’s head of police ordered the arrests of the 12 lawyers and activists participating in the meeting, including two South Africans, one Ugandan and nine Tanzanian nationals for “promoting homosexuality.”[140]

Initially police allowed the lawyers and activists to be released on bail the next day, but revoked the bail three days later and re-arrested them on unknown charges. While detaining them, police threatened to subject the lawyers and activists to forced anal examinations, a discredited method of seeking evidence of homosexual conduct that is cruel and degrading and can amount to a form of torture.[141] Police then released them on October 26, after nine days in jail, and deported all foreign workshop participants a day later.[142] The nine nationals were released and never tried. As discussed above, authorities suspended CHESA following the raid of its meeting, falsely claiming that it was promoting gay marriage.[143]

Authorities have also targeted staff of organizations working on mining. On July 12, 2017 police arrested Bibiana Mushi and Nicholaus Ngelela Luhende of the Mwanza-based NGO Actions for Democracy and Local Governance (ADLG) as they conducted a capacity building workshop for local government officials working in mining areas near Kishapu in the Shinyaga region, northern Tanzania. Prosecutors charged them with “disobedience of statutory duty” under Section 123 of the penal code, alleging that the two were operating outside the scope of their organization’s mandate and the NGO law. Four months later, the Kishapu district court acquitted charges Mushi and Luhende of the charges against them.[144]

In Zanzibar, an NGO worker with an organization that provides health and reproductive education to LGBT groups told Human Rights Watch that police raided their offices in 2018, following a sting operation against sex workers. The police destroyed and took property including a computer and external hard drives because they claimed that the organization was working with sex workers.[145]

Disputing Nationality

Authorities have frequently raised questions about the nationality of government critics to both frustrate and silence them. Human Rights Watch is aware of several cases in the last five years of immigration authorities seizing passports or questioning or summoning individuals to prove their nationality following their criticism of the government.

In 2017, immigration officials visited the offices of the Tanzania Human Rights Defender Coalition (THRDC), an NGO in Dar es Salaam, and questioned its director Onesmo Olengurumwa about his nationality. [146] Authorities denied that his activism motivated the investigation.[147] THRDC works towards enhancing the security and protection of human rights defenders in Tanzania and in 2017, Olengurumwa told the media that he believed the harassment had to do with his activism on land rights in Loliondo in northern Tanzania.[148] Bishop Severine Niwemugizi, a Catholic bishop for Rulenge-Ngara, who had reportedly said that Magufuli’s presidency would fail if he did not resume the stalled constitutional review process, was summoned by immigration officials also in September 2017.[149]

In 2018, as discussed above, immigration officials questioned both Twaweza director Aidan Eyakuze and student activist Abdul Nondo. Nondo told Human Rights Watch that after the officials questioned him about his origins, “[t]hey told me they will continue with investigating if I am Tanzanian or not. And if they find I am not Tanzanian they will take me to court.”[150] An NGO director told Human Rights Watch that he and his children were repeatedly harassed by immigration authorities after his organization carried out work that implicated high ranking government officials in human rights violations.[151]

This has also affected journalists. Michael O., a journalist in northern Tanzania told Human Rights Watch that after he published a story about land rights, immigration authorities called him to “asked me where my father and where I was born.” [152] In 2019, as also discussed above, police said they had arrested journalist Erick Kabendera to question him about his nationality. Kabendera had written for several international publications critiquing Tanzanian politics. The inquiry into his nationality was later dropped as prosecutors charged him with offenses related to money laundering, tax evasion and leading organized crime.

Office Bombings and Intimidation

In February 2016, unknown people threw a bomb into the yard of Omar Said Shabaan’s law offices in Zanzibar. Shabaan, president of the Zanzibar Law Society, had publicly criticized the decision of the Zanzibar Electoral Commission to conduct a re-run of presidential election in Zanzibar that year. Police told Shabaan that investigations were ongoing, but at time of writing, there have been no arrests.[153]

On August 26, 2017 unidentified armed men bombed the office of a law firm IMMMA Advocates in Dar Es Salaam, which belonged to Fatma Karume, legal counsel to Tundu Lissu, then Tanganyika Law Society president and opposition member of parliament. The bomb shattered windows and blasted an entrance open, according to reports.[154] Lissu had been a prominent critic of Magufuli. According to Karume, the police took video recordings of the office premises and did not do anything after that.[155] Two weeks later, unknown gunmen shot and severely injured Lissu at his residence in Dodoma, discussed below.[156]

NGO workers from nine organizations working on politically sensitive issues told Human Rights Watch that authorities, including regional and district commissioners, have written letters to NGOs, threatening action against them. For example, staff of one NGO told Human Rights Watch that they have received letters from district commissioners threatening them with arrest for advocating for the rights of communities affected by mining:

The letter was trying to stop us from acting on behalf of those whose rights were being violated because the government thought we were trying to oust the mining company so the government wouldn’t get their taxes. The commissioner wrote saying that he would use his powers to arrest us for behavior contrary to his command. And he is in a position to close our offices so that we could no longer operate in his district. [157]

Several NGO representatives in Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar and Arusha told Human Rights Watch that police and, in one case, a government security agent verbally warned them to stop doing their work. Edward R, an activist working in Arusha told Human Rights Watch:

We could sometimes get phone calls. Threatening us. One of our colleagues who faced this.…. Policemen came with their [police vehicles] and parked it outside the gate [outside the office] to tell them, “In case you do anything we are here.” Sometimes if you walk outside the gate you can see the police car following you.[158]

IV. Attacks and Restrictions on the Political Opposition

In 2016 Magufuli ordered that all political activities be suspended until 2020, effectively banning elected politicians from holding rallies outside their constituencies and limiting the geographic reach of many opposition politicians.[159]

In 2019, Parliament amended the Political Parties Act to restrict the independent operation of political powers by giving the registrar of political parties wide powers to deregister parties.[160] These amendments granted broad powers to the registrar of political parties to demand information from political parties, subjecting parties to a fine of up to 10 million Tanzania Shilling fine (about $4364) if they failed to comply; to suspend individual members of political parties; and required institutions or individuals to get approval from the registrar to conduct civic education, or face criminal sanctions including a fine of imprisonment or a fine of up to five million Tanzania shillings (about $2182).[161]

In addition to these restrictions on political activities, opposition party members have also faced multiple arrests and criminal charges apparently after publicly criticizing the government, during 2017 and 2018, a period when numerous by-elections for vacated parliamentary seats took place.[162] In October 2017, as discussed in section II above, police arrested Zitto Kabwe, leader of ACT Wazalendo, an opposition party, apparently for breaching the Statistics Acts of 2015. Kabwe had made remarks about the economic growth of Tanzania. See section II above.

In February 2018, Joseph Mbilinyi, a parliamentarian in Mbeya with opposition party Chadema and Emmanuel Masonga, a party official, were sentenced to five months imprisonment in February for “insulting” Magufuli during a political rally the previous December. The MPs were alleged to have accused Magufuli of involvement in the attempted assassination of opposition politician Tundu Lissu in 2017.[163]

Also in February 2018, a 21-year-old student, Akwilina Akwilini, was shot and killed as police attempted to disperse a Chadema demonstration.[164] Akwilini’s killing sparked widespread condemnation against government repression and an increase in killings and abductions across the country.[165] In connection with the demonstration, nine opposition members, including the chairperson of Chadema, Freeman Mbowe, were charged with sedition, incitement of violence and holding an illegal rally. According to a media report, the charges against Mbowe for “inciting hatred” are based on a speech he gave during the demonstration in which he said Magufuli would not last long in his job.[166] In November a magistrate ordered the arrest of Mbowe and member of parliament Esther Matiko after both failed to attend earlier court sessions.[167] The high court eventually ordered their release and reinstatement of bail in March 2019.[168]

In September 2017, unidentified attackers shot and wounded Tundu Lissu, an outspoken member of parliament critical of the president, in Dodoma, forcing him to seek medical treatment in Kenya and Belgium. [169] Lissu, Chadema’s chief whip, and president of the Tanganyika Law Society, had been arrested multiple times in 2017, including for “insulting words that are likely to incite ethnic hatred.”[170] The government has said it is investigating the assassination attempt against Lissu. [171]

Within a fortnight in early 2018, unknown assailants brutally killed two Chadema officials On February 13, the body of Daniel John, an official for Hananasif ward in the Kinondoni district of Dar es Salaam, was discovered along the coast of Dar es Salaam with machete wounds to the head.[172] On February 23, Godfrey Luena, a Chadema member and a councilor for Nemawala ward in Morogoro, was found dead outside his home.[173] Luena also worked as a human rights monitor, documenting illegal land appropriation. Police have said that investigation into John’s death is ongoing, but there have been no arrests.[174]

V. Impact of Repression

Monitoring still goes on but direct threats are not there. They do that only when you start speaking out. If I call a press conference they will follow up. For as long as I am quiet, I am safe. But that is not life because you are always looking over your shoulder.

Jack F., director of a Dar es Salaam-based NGO, Dar es Salaam, August 2018

Fear and Civil Society Self-Censorship

Many of the people Human Rights Watch spoke with talked about an increased sense of fear of reprisals for being critical of the government. To survive, civil society organizations have adopted self-censorship as a strategic response. One person talked about “sugarcoating” their messages to government because “criticizing” does not work under Magufuli’s government. [175]