The Story of Maria Higginbotham

Maria Higginbotham jokes that she was just born unlucky: in 2003, she was a 43-year-old regional bank manager in a town outside Seattle, Washington with two children and no serious health issues. But one day she went out to get the mail and suddenly found she could not walk. Within weeks, she was admitted to the hospital for the first of what would be 12 operations performed on her spine between 2003 and 2015. Her diagnosis: an aggressive form of degenerative disc disorder. The surgeries would put hardware in her back to prop up her spine and relieve pain, but each time it was only a matter of months before another disc in her back buckled and she found herself back on the operating table. Her spine is now “encased in metal,” she said. A recent operation was required just to remove all the hardware accumulated in her body over the years: she holds up a Ziploc bag full of nuts and bolts.

Those operations not only failed to halt the collapse of her spine — they also left her with adhesive arachnoiditis, a condition caused by inflammation of the membrane surrounding the spinal cord that is often the result of trauma, including from surgery. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke acknowledges that it is a rare but extremely painful condition. “Your spinal cord is supposed to hang loose, like worms, in your spinal fluid — [in my case] they glue themselves together,” is how Higginbotham explained it. Because of the arachnoiditis, as well as a number of other more common pain conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, she has “constant pain in the middle of [her] back, and a sharp shooting pain when [she] move[s].”

She has tried the gamut of available pain treatments, from physical therapy to steroid injections to nerve ablations — which heat up a small area of nerve tissue to decrease pain signals from it — but none provide adequate relief. Medical marijuana helped somewhat, but makes her too anxious. She has racked up more than $2,000 in credit card bills paying for treatments that are not reimbursed by insurance, such as medical marijuana and over-the-counter heat patches. Higginbotham cannot take ibuprofen-like drugs due to stomach and liver problems.

Because nothing else works, she relies primarily on opioid analgesics to get through the day. She has been on the medication in doses that have varied only slightly since 2004. She has a pain pump, a device implanted into the body that delivers pain medication directly to the spinal cord, and also uses patches that infuse opioids through her skin, which she replaces every few days. This combination of medications allowed her to function well enough to make meals, take care of her two dogs, tidy her house, and care for her grandchildren for many years.

But in March 2018, Higginbotham’s medical provider said he would be reducing her opioid medications by 75 percent in order to get her down to a dose he said was recommended in a guideline from the US Centers for Disease Control: 90 milligram equivalents of morphine. He told Human Rights Watch he believed Higginbotham had done well on the medication, but that his clinic was implementing a new policy over fears they could be held liable for high-dose opioid prescriptions:

There’s a lot of talk in the pain medicine world that if you do not get people down to 90 morphine equivalents, you set yourself up for a liability, especially if something were to happen to that patient. It doesn’t matter if you did everything appropriately [to prevent abuse] — and we do everything, urine drug testing, prescription monitoring, screening for mental health issues, pill counts. It doesn’t feel like enough. We still feel like we’re vulnerable to being held liable for patients if they’re over that guideline limit, even when you know they’re not addicted and they’re benefitting [from opioids].

When Human Rights Watch interviewed Higginbotham in April 2018, the pain doctor had reduced her dose by more than a third. She said that the effects have been profound: she could be on her feet for just a few minutes at a time and needed her family’s help to get out of bed or go to the toilet. She had lost 70 pounds because of the pain and because she couldn’t stand up long enough to make herself a meal:

Pain has a way of defeating you, taking away any pleasure you used to get. I’m 57 years old and I’m almost completely bedridden due to agonizing pain like torture.

I cannot hold my 15-month-old grandson. I cannot hold my beloved dogs, I can’t bend over to touch them. I cry out in my sleep because I can’t find a way to get comfortable. The sun is shining and my flowers are blooming and I want to just walk outside with my dogs and look at them, but I can’t.

I can barely get myself off of my toilet, sometimes I have to get off the couch by getting on my hands and knees and pulling myself up because I can’t stand up it hurts so badly. I don’t want to leave my home.

Higginbotham’s medical provider told Human Rights Watch that she is not doing well, but has said he has no option but to continue gradually lowering her medication. He has suggested she seek pain relief by undergoing another surgery, this time to remove a screw that may be putting pressure on a nerve in her back. But Higginbotham is terrified of going under the knife again after so many failed and problematic surgeries:

My body is failing me and all I want to do is live a life free of a massive amount of suffering — I know I will never be free from pain but to subject me to even more pain is inhuman. How many times do I have to go through this to prove there isn’t a fix? I can’t be fixed.

Summary

An estimated 40 million adults in the United States suffer from significant levels of chronic pain, making it one of the most common health problems and the leading cause of disability in the country. People with chronic pain tend to have worse overall health than other Americans, experience depression and anxiety disorders at higher rates, and use the health care system more frequently. Unlike people with acute pain, chronic pain patients often experience a sense of hopelessness and catastrophic thoughts brought on by fears that their pain might never go away.

Despite the extent of this problem and its medical, social, and economic impacts, many patients in the US do not have access to adequate treatment for chronic pain. This is in part because chronic pain can be difficult to treat: it can result from a wide range of causes and it affects different people in different ways. But it is also because most clinicians are poorly trained in pain management, health insurance policies often do not adequately cover non-pharmacological treatments, and the health care system does not facilitate multidisciplinary treatment of chronic pain, which is often the most effective option for complex pain.

The opioid overdose crisis that has struck the US in recent years, which claimed more than 70,000 lives in 2017, has further complicated the situation for chronic pain patients. Many overdose deaths involve the same opioid medications commonly prescribed to people in chronic pain. Today, treating chronic pain with opioids is medically controversial because evidence suggests their effectiveness is limited. But in the 1990s, these medications became a go-to option for physicians treating chronic pain. Between 1999 and 2010, prescriptions for opioid analgesics quadrupled in the US.

The government has a duty to address this rapidly unfolding public health crisis: in 2017 alone, more Americans are estimated to have died of a drug overdose than were killed in the Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan wars combined. Given the role prescription opioids have played in the crisis, measures to regulate the use of these medications and to promote more careful prescribing practices are essential.

However, under international human rights standards, actions taken to combat the overdose epidemic should take the needs of chronic pain patients into account. The government should seek to avoid harming chronic pain patients: some patients still have a legitimate need for these medications, while others who have been on these medications for many years but who may not be benefiting from them should be weaned off them safely and in accordance with best medical practice.

If harms to chronic pain patients are an unintended consequence of policies to reduce inappropriate prescribing, the government should seek to minimize and measure the negative impacts of these policies. Any response should avoid further stigmatizing chronic pain patients, who are increasingly associated with — and sometimes blamed for — the overdose crisis and characterized as “drug seekers,” rather than people with serious health problems that require treatment.

This report presents the challenges faced by chronic pain patients like Maria in obtaining appropriate care, examines how the government’s legitimate efforts to address the opioid epidemic have contributed to unintended but serious harm, and fallen short of its responsibilities to address the needs of individuals taking opioid medicines for chronic pain. The report is based on 86 interviews with chronic pain patients, healthcare providers, and officials, which were conducted over the phone or in person during visits to Tennessee and Washington State between March and July 2018. We also reviewed relevant state and federal laws, regulations, and clinical guidelines related to chronic pain management and opioid prescribing.

Public health officials generally agree that the current opioid epidemic is the result of multiple factors, including both a previous over-reliance on opioids to treat chronic pain and aggressive and misleading marketing of opioid medication by pharmaceutical companies. As a result, federal and state governments have made reducing opioid prescribing a major priority in the last five years.

Top government officials, including the President, have said the country should aim for drastic cutbacks in prescribing. State legislatures encourage restrictions on prescribing through new legislation or regulations. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has investigated medical practitioners accused of overprescribing or fraudulent practice. State health agencies and insurance companies routinely warn physicians who prescribe more opioids than their peers and encourage them to reduce prescribing. Private insurance companies have imposed additional requirements for covering opioids, some state Medicaid programs have mandated tapering to lower doses for patients, and pharmacy chains are actively trying to reduce the volumes of opioids they dispense.

The medical community at large recognized that certain key steps were necessary to tackle the overdose crisis: identifying and cracking down on “pill mills” and reducing the use of opioids for less severe pain, particularly for children and adolescents. However, the urgency to tackle the overdose crisis has put pressure on physicians in other potentially negative ways: our interviews with dozens of physicians, mostly from Tennessee and Washington State, found that the atmosphere around prescribing for chronic pain had become so fraught that physicians felt they must avoid opioid analgesics even in cases when it contradicted their view of what would provide the best care for their patients. In some cases, this desire to cut back on opioid prescribing translated to doctors tapering patients off their medications without patient consent, while in others it meant that physicians would no longer accept patients who had a history of needing high-dose opioids.

The consequences to patients, according to Human Rights Watch research, have often been catastrophic. Patients like Maria were often left with debilitating pain that made them incapable of going about their daily lives — simple activities, such as household chores or taking care of others, were suddenly impossible. In many cases, patients suffered extreme anxiety and others even thoughts of suicide, as they questioned whether their lives would ever be worth living in such extreme pain. Others, particularly those who struggled to find a medical provider if their treatment still involved opioid medications, felt betrayed and abandoned by the medical community.

Amidst the repeated calls for cutbacks in prescribing, new laws and regulations on prescribing, stricter insurance policies, and concerns about criminal sanctions, medical providers lacked clear guidance on the harms of involuntary tapering and their legal and ethical obligations to provide adequate treatment for chronic pain patients. State agency policies on opioids, as well as physicians interviewed for this report, frequently referred to the Centers for Disease Control Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain as a key resource in this regard. The Guideline, published in March 2016, sought to address gaps in primary care physicians’ understanding of opioids, their risks, and the limited evidence surrounding their effectiveness.

The Guideline proposes a carefully balanced approach. It cautions against the use of opioid analgesics to manage chronic pain, especially at high doses, but leaves decisions about individual patients to clinicians. It advises providers to try alternatives before resorting to opioids, but acknowledges that some patients who do not see their pain resolved by other means might still need opioids, sometimes at high doses. The Guideline also acknowledges that because opioids were frequently used in the US to treat chronic pain from the 1990s onward, many patients may already be on high doses and tapering those patients, who have developed a physical dependency on the medication, may be difficult.

However, the Guideline does not clearly state that physicians should not taper patients off their medications involuntarily, and it has been used by state officials to justify policies that define maximum doses for all patients regardless of their individual medical needs.

Even when medical providers understood that the Guideline was voluntary, they believed they risked punishment or unwanted attention from law enforcement agencies or state medical boards if they maintained patients at high doses. Because the DEA, which licenses all controlled substance prescribers in the country, defines illegal prescribing as anything not within the confines of “professional practice,” a term that has no commonly accepted meaning, providers said they were left to police themselves against risks, and did so by using the CDC Guideline as a red line for prescribing. Twelve physicians told Human Rights Watch that they had made involuntary dose reductions for patients — sometimes hundreds — who were compliant with screening procedures and appeared to be benefiting from their medication. This practice is inconsistent with the Guideline’s recommendations, unsafe, and can severely undermine a patient’s quality of life.

This report found that chronic pain patients, particularly those who have relied on opioid medications for treatment, face increasing difficulty finding clinicians willing to provide them care, and feel abandoned and stigmatized by the healthcare system as a result. Some providers said they refused to take on new chronic pain patients who were on opioids because of the liability, even if they believed that those patients had diagnoses that warranted treatment with opioid medication. In cases where a pain clinic was shut down or a provider’s license revoked, there appeared to be minimal government efforts to ensure continuity of care. Because many patients who take opioids develop a physical dependence on them, abrupt termination of care could, in addition to increased pain, trigger withdrawal.

Patients described harms they have experienced as a result of being involuntarily tapered, including increased pain, decreased mobility, and thoughts of suicide. Indeed, the debilitating physical, mental, and social effects of chronic pain have been well-documented. But involuntary tapering or inadequate treatment can also have a major negative impact on a patient’s quality of life, and can even drive them to self-medicate with alcohol or illicit drugs.

Moreover, patients and physicians told Human Rights Watch that non-opioid treatments for chronic pain are often unavailable or not covered by health insurance. The Guideline recommends that patients use non-opioid therapies to treat chronic pain, and emphasizes the importance of non-pharmacological treatments like massage, acupuncture, and various types of physical therapy. However, many patients and physicians told us these treatments are not an option because they would require patients to incur burdensome out-of-pocket costs.

The government’s efforts to combat the overdose epidemic should be balanced with the interests of chronic pain patients who have a medical need for opioid analgesics. As this report documents, current policies and practices to reduce the use of these medicines have significant unintended negative consequences, which the government should seek to redress. Among others, it should document the pace of involuntary tapering and its impact on chronic pain patients — including patients' mental and physical health as well as hospitalization — and take corrective steps as needed.

More broadly, the government should take proactive steps to ensure that chronic pain patients who have a serious and often debilitating medical condition have access to adequate care. Federal and state governments have a responsibility to ensure that a broad range of pain treatment interventions is available to such patients, including non-pharmacological treatments, and that treatment modalities are covered by insurance plans, including Medicaid and Medicare.

In 2016, the Department of Health and Human Services released a National Pain Strategy, calling it the federal government’s first “coordinated plan for reducing the burden of chronic pain” in the United States.[1] The strategy aims to improve the prevention and management of pain; support the development of an integrated, patient-centered, approach to pain management; reduce barriers to treatment; and improve public awareness. But the strategy does not specifically address the situation of the thousands of chronic pain patients who are already on opioid medicines. To date, implementation of the strategy has primarily focused on a research agenda, rather than reducing the barriers to care chronic pain patients currently face. Congress has not made any appropriations to implement the strategy.

Key Recommendations

To counter harmful trends in the treatment of chronic pain patients and ensure their access to appropriate health services, Human Rights Watch makes the following recommendations:

Implement the National Pain Strategy

- Federal and state governments should fully implement and provide adequate funding for the National Pain Strategy, including the components related to healthcare worker and public education and delivery of services. While research on pain prevention and management is critical, it is essential that steps to improve access to existing interventions are taken right away, as today’s chronic pain patients cannot wait.

Limit the Unintended Consequences of Prescription Reductions for Chronic Pain Patients

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) should revise its 2016 Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain to explicitly state that patients should not be involuntarily tapered off opioids and that there is no mandated maximum dose.

- The CDC and DHHS should work with other relevant federal and state government agencies, state medical boards, and professional and civil society groups to ensure that clinicians, including those caring for patients on high doses of opioids, can implement the Guideline’s recommendations without having to fear unwarranted legal scrutiny, arbitrary limits, or administrative barriers.

- The CDC and DHHS should work with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Department of Veterans Affairs, individual states, and private insurance providers to identify and address limits or administrative practices that arbitrarily interfere with the ability of chronic pain patients who need opioid analgesics to access them.

- State Departments of Health and other responsible agencies should take steps to ensure that chronic pain patients are not abruptly forced off their medication when a pain clinic is shut down or a provider removed from practice, and it should involve local medical stakeholders to this end.

Improve the Availability, Accessibility and Affordability of Multimodal Pain Management, Including to Non-Pharmacological Modalities

- The Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Department of Labor, and state insurance commissioners should seek to expand insurance coverage of treatment modalities for chronic pain, including non-pharmacological interventions.

- The National Institutes of Health, CDC and other relevant government agencies should fund more research into the effectiveness of different modalities for chronic pain.

Improve Data Collection on Involuntary Tapering and the Overdose Crisis to Allow the Most Effective Response Possible

- Federal and state government agencies should collect data about the frequency of involuntary tapering among chronic pain patients, as well as outcomes for those patients: if they have physical and mental health issues as a result, whether they are hospitalized, maintained in care, or commit suicide as a result. To the extent that government agencies have collected such data, they should disclose it to the public at the present time.

- Federal and state government agencies should implement or encourage standardized data collection on overdose deaths, including details relevant to gaining a better understanding of the role of prescribed opioids in such deaths.

- Overdose deaths should be cross-referenced with prescription monitoring data and other statistics to obtain detailed information on current or past prescription history of the overdose victim.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted from March to July 2018, including field visits to Washington State in April and May 2018 and to Tennessee in June 2018. Human Rights Watch conducted 86 interviews with various stakeholders, including 44 chronic pain patients; 34 health care workers (including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, psychologists, and pharmacists); four officials from the Departments of Health of Washington (as well as Washington State’s Labor and Industries, a workers’ protection and compensation group that has been instrumental in influencing policy on opioid prescribing in the state); and five experts in medicine, law, and health policy. In addition to interviews in the two states, Human Rights Watch conducted telephone interviews with patients in Maine, West Virginia, Texas, California, and Montana; and physicians in West Virginia, Maine, Utah, Colorado, and Maryland.

Human Rights Watch also extensively reviewed medical literature, using academic databases to find available studies about opioid use for chronic pain, opioid dependence, and tapering practices.

Most interviews with patients were conducted in their homes or at a meeting place convenient for them. Patients were identified primarily through online channels, such as patient support groups on social media. Most interviews with healthcare providers were conducted in their offices or by phone. Interviews were almost exclusively conducted in private, and occasionally in the presence of a patient’s relatives. Interviews were semi-structured and covered a range of topics related to chronic pain management and treatment. Before each interview we informed interviewees of its purpose, the kinds of issues that would be covered, and asked whether they wanted to participate. We informed them that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific questions without consequence. Human Rights Watch did not offer any incentives to interviewees. In some cases, patients asked their identities to be disguised to protect their privacy, while many healthcare workers declined to be identified for fear of retribution. All interviews were conducted in English.

We chose Washington State for our field research because officials from Washington State’s Labor and Industries (the state’s workers’ compensation program) are sometimes credited with being the first to effectively document the increase in overdose deaths involving opioids,[2] and the state was thus one of the first to implement statewide rules more tightly regulating opioid prescribing in 2011.[3] We eventually chose Tennessee because it was a state where we were able to reach doctors and patients, and also because of new legislation on opioid analgesics enacted in 2018.[4] These two states were also chosen in part to present geographic and socioeconomic diversity.

In addition to asking healthcare providers about conflicts of interest, Human Rights Watch screened all providers for pharmaceutical company funding using available databases, such as ProPublica’s Dollars for Docs.[5] The majority of interviewees did not appear to have significant financial relationships to these companies. Human Rights Watch has noted the small number of cases in which a healthcare provider had received money from pharmaceutical companies (above $1,000 per year).

In July 2018, we sent a summary of the findings of our research to the CDC, inviting them to respond. We received a response on August 28, 2018, a copy of which has been included in an annex to this report. In August 2018, Human Rights Watch sent a request for comments to the DEA, the Federation of State Medical Boards, and several state Medicaid and private insurance providers that are mentioned in this report. In September, the DEA and the Federation of State Medical Boards replied to Human Rights Watch’s requests for comment, but as of when this report went to print in December, none of the contacted insurance companies or officials from the Tennessee Department of Health had responded.

All documents cited in the report are either publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch.

Background

Chronic Non-Cancer Pain: Prevalence, Impact, and Treatment

Chronic pain, typically defined as pain lasting three months or more, is one of the most common health problems in the United States. An estimated 40 million adults have high levels of pain every day, and these individuals report worse health, use the health care system more frequently, and are more likely receive disability benefits.[6] In 2016, the Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that low back pain and migraines were among the five leading causes of ill-health and disability — and the leading cause in high-income, high-middle-income, and middle-income countries.[7]

Chronic pain has serious ramifications not just physically, but psychologically. Depression and anxiety disorders are much more prevalent in individuals experiencing chronic pain than in those who do not.[8] A number of studies have demonstrated that chronic pain patients have an increased risk of suicide, even when controlling for other factors such as socioeconomic status, general health, and psychological disorders.[9] Chronic pain patients also often experience a sense of hopelessness and catastrophic thoughts brought on by fears that their pain might never go away.[10]

Chronic pain can result from a wide range of causes, such as traumatic injury, medical treatment, inflammation, or neuropathic pain.[11] Chronic pain is highly individualized, meaning patients with the same diagnosis can have different pain levels. Because chronic pain has such diverse causes and wide-ranging effects, it poses challenges to treatment[12]: patients react (and fail to respond) to a wide range of interventions for their pain.[13] Psychological treatments can be an important additional tool in treating chronic pain, and cognitive behavioral therapy and stress-reduction techniques have proven helpful to patients with intractable pain.[14]

The 2011 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “Relieving Pain in America” suggests that it is for these reasons that a simplistic medical approach, in which doctors diagnose and “cure” patients, might not be the norm for patients suffering chronic pain. It cautions that the “road to finding the right combination of treatments … may be a long one,”[15] and suggests a large number of treatment options, including:

- Medications, including opioids and non-opioid analgesics, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Regional anesthetic interventions (including joint and epidural steroid injections, nerve blocks, and implanted devices that deliver analgesic medications directly to the affected area)

- Surgery

- Physiological therapies

- Rehabilitative/Physical therapy

- Complementary and alternative medicine (including massage therapy, supportive group therapy, music therapy, acupuncture, chiropractic spinal manipulation and yoga[16])

According to the IOM report, many Americans receive inadequate pain prevention, assessment and treatment. The report identifies numerous challenges that impede better pain care, including financial incentives that work against the provision of the best, most individualized care; unrealistic patient expectations; a lack of valid and objective pain assessment tools; a lack of training for clinicians in guiding, coaching and assisting patients with pain; a lack of time of primary care providers to do comprehensive assessments; and a dearth of pain specialists.[17]

The Use of Opioid Analgesics in Treating Chronic Non-Cancer Pain

While opioids are a widely used method for treating acute pain, their efficacy and safety in chronic pain management is hotly debated. Scientific evidence of the effectiveness and risks of opioid treatment for chronic non-cancer pain is contradictory and inconclusive.

One 2010 systematic review found that there was only weak evidence to suggest that patients on opioid pain medicines over long time periods experienced clinically significant pain relief.[18] Another systematic review in 2017 regarding the use of high dose opioids in chronic non-cancer pain treatment similarly found a “critical lack of high quality evidence regarding how well high-dose opioids work for the management of chronic non-cancer pain in adults.”[19] The review also found a lack of high quality evidence regarding the presence and severity of adverse events caused by the medications.”[20] A 2018 trial of veterans with common forms of musculoskeletal pain did not find a difference in pain-related functioning between patients treated primarily with non-opioid treatments (culminating in a low dose opioid for a minority), compared to a group of patients treated with increasingly powerful opioid medications, suggesting opioids were not a uniformly superior treatment.[21]

Even if opioid medications are not effective for a majority of chronic pain patients, there is broad — but not unanimous — agreement that for a subgroup of patients they do provide benefits. The 2016 CDC Guideline states that opioid medications may offer benefits to some patients.[22] Similarly, the Federation of State Medical Boards recommends that while patients should be informed of the limited evidence supporting opioid use for treating chronic pain as well as the risks, opioid medication may be appropriate for those whose pain is not resolved with other methods.[23] A 2014 literature review that was part of Germany’s effort to update its chronic pain treatment guidelines concluded that there was sufficient evidence to recommend long-term opioids as an option for chronic pain patients with certain diagnoses while recommending against their use for others.[24] The 2011 IOM reports suggests that the debate over inconclusive scientific findings about opioids should be “set against the testimony of people with pain, many of whom derive substantial relief from opioid drugs.”[25]

Two systematic reviews of national guidelines on opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain identified several general principles that are present in all guidelines.[26] These include conducting a risk assessment before initiating opioid therapy; informing patients about both its benefits and risks; establishing clear goals with the patient; avoiding monotherapy with opioids; closely monitoring the patient for loss of response to the therapy, adverse events and aberrant drug-related behavior; a regular reassessment of the therapy; and discontinuation in case of loss of response, serious adverse effects or serious or repeated aberrant behavior. See Table 1 for a more detailed overview of these general principles.

|

Table 1. General Principles on Initiation, Continuation, and Discontinuation of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain[27] |

|

Patient Selection and Risk Stratification |

|

|

|

|

|

Initiation and Titration |

|

|

|

|

Continuation |

|

|

|

Discontinuation |

|

Chronic Non-Cancer Pain Treatment in the United States

Chronic pain was often undertreated before the 1990s.[29] During that decade, patient advocates, pain specialists, and medical organizations increasingly drew attention to the suffering of chronic pain patients and began calling on practitioners to take greater steps to alleviate patient suffering, including by prescribing opioid analgesics.[30] In 1996, Purdue Pharma, a privately owned pharmaceutical company, introduced a new long-release opioid called OxyContin which it promoted aggressively for chronic pain management. It claimed that the medication was abuse-resistant, a claim that turned out to be false.[31]

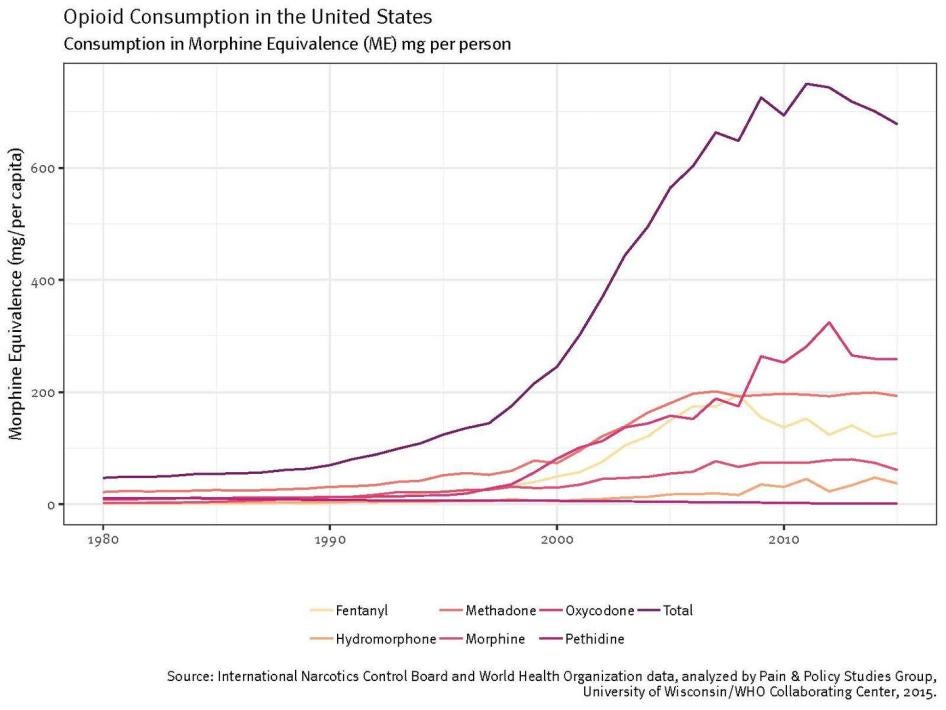

In 2001, the Joint Commission, responsible for accrediting some 21,000 health care organizations in the US, published new standards meant to combat the undertreatment of chronic pain. It encouraged physicians to actively seek to reduce pain levels and treat pain as a “fifth vital sign.”[32] While the Joint Commission did not recommend the use of any specific treatments for pain, in practice healthcare providers began to increase prescribing of opioid analgesics — the quickest and easiest way to address chronic pain. Between 1999 and 2010, prescriptions for opioid analgesics in the US quadrupled.[33] As shown in the graph below, opioid consumption by morphine equivalence — a measurement indicating the strength of a given drug at a given dose — grew astronomically from the 1990s onward: average annual opioid consumption in the US grew from 69.6 morphine equivalents and peaked at 739.8 morphine equivalents in 2011.[34]

Primary care providers, the first point of contact for chronic pain patients, became the main source of opioid prescribing. By 2012, they accounted for nearly half of 289 million opioid prescriptions dispensed by pharmacies.[35] These increases in prescribing happened against a backdrop of a dearth of evidence about the efficacy and safety of opioid medicines in chronic pain management and a widespread lack of training for primary care providers in pain management.[36]

A significant reason for the massive increase in their prescribing appears to have stemmed from providers’ genuine beliefs that they were giving their patients the most financially accessible option to treat their pain. In the 1990s and 2000s, insurance companies tightened reimbursement policies for nonpharmacological interventions, putting many holistic pain clinics out of business;[37] interdisciplinary chronic pain management programs approved by the Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) declined from 210 in 1998 to 84 in 2005.[38] One retrospective survey found that providers in low-income primary care settings had viewed opioids as the best option to treat pain, partly because it kept patients engaged with the healthcare system and because other treatments like physical therapy were unaffordable.[39] Providers in that study had also been influenced by evidence showing that women and minority groups were more likely to be undertreated for their pain.[40] Research suggests that opioid analgesics are more commonly prescribed long term to patients who are less healthy and experience greater disability: between 2007 and 2016, only three percent of commercially insured individuals were on long-term opioids, versus 14 percent of Medicare patients with disabilities.[41]

These rapid increases in opioid prescribing occurred at a time when government oversight was sorely lacking. Pharmaceutical companies marketed opioid analgesics with misleading claims about their efficacy and risks: for example, the Food and Drug Administration originally approved a label for OxyContin that stated that addiction from the medication was “rare.”[42] While the FDA did enhance warnings about OxyContin’s addictive potential in updated labels from 2001 onward, by that point physicians were writing more than 7 million prescriptions for OxyContin per year.[43] Unscrupulous physicians sold prescriptions in exchange for cash and sometimes for sex.[44] A West Virginia town with just over 3,000 residents was flooded with more than 21 million hydrocodone and oxycodone pills over the span of a decade, or 6,500 pills per person, but that does not seem to have immediately raised red flags for law enforcement.[45] “Pill mills,” or clinics with no real medical purpose other than to write prescriptions in exchange for cash, flourished for years in several states, including in Florida,[46] Ohio,[47] and West Virginia[48] before being shut down. People drove across several states to visit these clinics and re-sell the pills at a huge profit elsewhere.[49] The pharmaceutical industry lobbied against tougher regulation: political action committees (organizations that raise money privately to influence elections or legislation) representing the industry contributed at least $1.5 million to lawmakers who sponsored legislation undermining the DEA’s ability to investigate drug distribution companies that knowingly supplied fraudulent clinics and pharmacies.[50]

The Overdose Crisis

Toward the mid-2000s, public health officials first began noticing an uptick in overdose deaths involving opioids.[51] The scale of the crisis soon became clear, with opioid-related overdose deaths increasing almost threefold from 2002 to 2015.[52] In 2015, 52,404 people died of a drug overdose, more than any previous year on record; 63 percent of these deaths involved opioids. In 2017, the CDC estimated that a record 72,000 people died from accidental overdoses.[53] That same year, President Donald Trump declared the overdose crisis a public health emergency.[54]

The crisis has hit some states and populations particularly hard: opioid overdose deaths tend to be more common among white, poor, and rural populations, and states like West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania have seen overdose rates skyrocket in recent years.[55] However, there are indications that the impact of the crisis on other communities is growing: opioid-related deaths in African American communities are increasing,[56] and rates of opioid abuse among women are growing much faster than among men.[57]

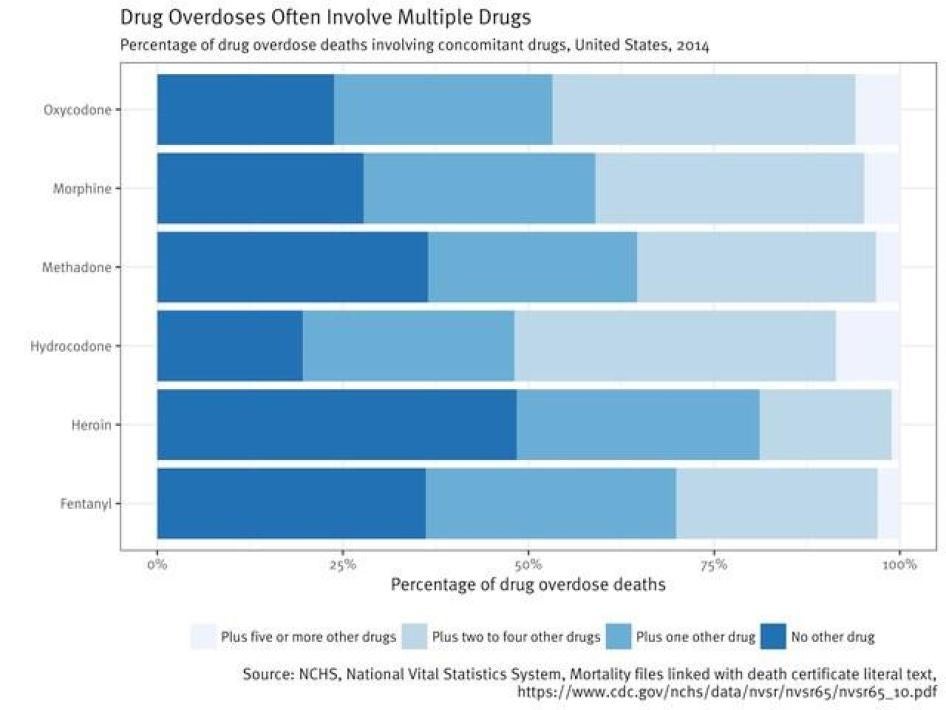

Many overdose deaths have involved prescription opioids. Between 2000 and 2015, opioid overdose deaths were equally split between deaths from heroin, and those from opioid pain medication such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, and morphine (this is illustrated in Graph 2 below from the CDC).[58] In the last few years, the rate of overdose deaths involving prescription opioids has leveled off but is still a significant contributor to overdose rates, increasing by three percent per year from 2009 to 2016; those deaths have been surpassed by heroin overdose deaths (which increased 33 percent per year from 2010 to 2014 and 19 percent from 2014 to 2016) and fentanyl overdose deaths, which increased by 88 percent per year from 2013 to 2016.[59] Remaining questions about how many deaths are attributable to prescription versus illicit opioids will be discussed in more detail later in this report.

In the 2000s, the growing realization that prescription opioids played a significant role in the overdose crisis set off a major debate about the appropriateness of prescribing these medications for both acute and chronic pain. This period also brought greater scrutiny of pharmaceutical companies that marketed prescription opioids, and patient advocacy groups that accepted money from pharmaceutical companies to campaign for medically appropriate care. The national media began shining a light on rampant abuses by pharmacies and clinics that prescribed and dispensed opioids for no proven medical reason at all.

Government Response

In the face of evidence of the role that prescription opioids played in this public health crisis, government agencies have sought to significantly limit the supply and use of prescription opioids in the US, encourage more conservative prescribing practices, strengthen oversight over the use of these medicines, and crack down on fraudulent prescribing and marketing practices.

Government agencies have imposed greater restrictions on some of the most commonly prescribed opioids,[60] brought high-profile lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies,[61] and cracked down on pharmacies and doctors accused of inappropriately supplying and prescribing opioid medicines.[62] All states but Missouri have implemented prescription monitoring programs, allowing physicians to check whether patients were visiting multiple doctors or pharmacies,[63] and states have cracked down on pill mills.

The government has clearly made cutbacks in prescribing a priority: President Trump, for example, promised to decrease opioid prescriptions by a third in the next three years.[64] The DEA has reinforced these statements with policies meant to limit the manufacturing of opioid analgesics in coming years,[65] and the Justice Department has encouraged insurance companies to help flag above-average prescribers to law enforcement.[66] These efforts have been echoed at the state level: as of 2018, 32 states had passed laws setting limits or guidelines on opioid prescribing.[67]

Because a large percentage of the overall volume of prescription opioids used in the country is prescribed for chronic pain — and there is limited evidence as to the efficacy of opioids in treating it — much government rhetoric and policy has focused on long-term prescriptions for that group, and especially on high-dose prescriptions, which studies show are more likely to result in overdose.[68]

However, reducing the prescribing of opioid analgesics poses significant challenges for patients with legitimate medical problems. While these medicines may not be the most effective or safe option for many of these patients, they served a specific purpose: to reduce their pain and improve their quality of life. Any effort to reduce reliance on opioid analgesics for chronic pain management should be accompanied by initiatives to ensure that these patients have access to other treatments for their pain and are not abandoned to suffering without appropriate medical attention.

Moreover, many thousands of chronic pain patients are already taking opioid analgesics, and many have done so for years. These patients should not be abruptly cut off these medicines as that could lead to withdrawal symptoms, anxiety, and increases in pain. Under international human rights standards, actions taken to combat the overdose epidemic should seek to ensure that chronic pain patients are not unnecessarily or disproportionately harmed. If that is unavoidable, the government should implement measures to remedy those harms. Unfortunately, the 2016 National Pain Strategy, a coordinated federal plan to improve prevention and management of chronic pain, does not address this issue at all.

In an effort to address overprescribing and rectify inadequate provider knowledge about the risks versus the benefits of opioid analgesics, the CDC began developing a guideline in 2010 that would help to provide “better clinician guidance on opioid prescribing.”[69] This Guideline is a voluntary set of recommendations aimed at primary care providers. It encourages providers to first try non-opioid alternatives in treating chronic pain, and if they do ultimately resort to opioid prescribing, they are encouraged to avoid prescribing more than 90 milligrams of morphine equivalence (MME) — a value assigned to opioids to signify their strength. However, it also recognizes that some patients will need opioid analgesics, including doses above 90 MME, for their pain and leaves prescribing decisions to the discretion of the physician.

|

Clinical Recommendations: The CDC and VA Guidelines The CDC’s Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain is addressed to primary care providers — not pain specialists — and is intended to “improve communication between providers and patients about the risks and benefits of opioid therapy for chronic pain, improve the safety and effectiveness of pain treatment, and reduce the risks associated with long-term opioid therapy, including opioid use disorder and overdose.” [70] The following is a summary of the full CDC recommendations:

In 2017, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) issued its own clinical guideline as part of a broader initiative to reduce opioid prescribing within the organization. The VA Guideline recommends against initiating long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain, and recommends non-pharmacological or non-opioid treatments instead. The VA Guideline is directive in encouraging providers to “avoid titrating to doses higher than 90 MME.”[71] Unlike the CDC Guideline, the VA Guideline actively encourages tapering, including tapering without patient consent: it says tapers should be initiated by a provider when the “risks of long-term opioid therapy outweigh benefits.” It also states that patients on long-term opioids “may threaten suicide when providers recommend discontinuation of opioids,” but that “continuing (long-term-opioid therapy) to ‘prevent suicide’ in someone with chronic pain is not recommended as an appropriate response if suicide risk is high or increases.” Instead, the VA encourages providers to involve behavioral health providers to “treat a patient who becomes destabilized as a result of a medically appropriate decision to taper or cease [opioids].”[72] The VA asserts that “the CDC Guideline did not form the basis of the deliberations on the strength or the direction of these recommendations,” but the authors state they were aware of the CDC Guideline and came to some similar conclusions.[73] |

The CDC Guideline offers carefully balanced recommendations that safeguard provider discretion and provide exceptions for chronic pain patients in need of opioid analgesics. Unfortunately, some of the regulations, policies and recommendations it appears to have inspired do not. According to the CDC, 46 states have implemented guidelines or other policies aligned with its Guideline. However, in our review, not all states strictly followed recommendations made in the CDC Guideline. For example, Human Rights Watch found that six state Medicaid programs imposed maximum dosages and involuntary tapering on patients. All of these policies were passed after the publication of the CDC Guideline in 2016, and three of them explicitly state that these policies were motivated by the CDC Guideline.[74] As mentioned previously, neither involuntarily tapering nor mandatory dosages are recommended in the CDC Guideline.

The CDC does not say how the Guideline has influenced insurance companies and pharmacy policies, however our research found that these companies publicly prioritize cutbacks in prescribing, without any indication that they are monitoring the impact that such cutbacks have on patients or assurances that alternative treatments are available for those patients.

Our research focused primarily on the effect these policy initiatives have had on chronic pain patients who already receive opioid analgesics, and on the physicians who care for them. Both clinicians and patients told Human Rights Watch that prescribing practices had changed in ways that are frequently inconsistent with the recommendations in the Guideline. Many healthcare providers impose involuntary dose reductions on patients; offer them little or no support in the tapering process; and fail to refer patients to mental health professionals or other services when patients experience a deterioration in their health as a result of tapering. Patients are tapered despite deriving benefits from the medication, having no record of violating risk-screening protocols, and being compliant with clinic regulations like urine drug testing and pill counts.

This kind of tapering is inconsistent with the CDC Guideline. In a letter to Human Rights Watch, the CDC reaffirmed that the Guideline “does not provide support for involuntary or precipitous tapering, and that such practice can be associated with withdrawal symptoms, damage to the clinician-patient relationship, and patients obtaining opioids from other sources. It also emphasized that clinicians have a responsibility to carefully manage opioid therapy and not abandon patients in chronic pain, and that obtaining patient buy-in before tapering is critical.”[75]

While several of the physicians we interviewed who were involuntarily tapering their patients were aware that this practice was not encouraged by the CDC, they described an atmosphere in which they felt that they had no choice but to prescribe at, or below, the 90 morphine milligram equivalent threshold described in the CDC guideline, even when they believed the patient benefited from higher doses of medication. They described a number of prods and pressures that made them feel compelled to taper patients on higher doses: the fear of scrutiny by law enforcement agencies like the DEA, which registers every prescriber of controlled substances in the country and has ready access to information about prescribing practices of most providers; monitoring by state medical boards, which are responsible for licensing practitioners; and state laws and regulations, which in some states mandate dose caps or otherwise reinforce the 90 morphine milligram equivalent threshold defined in the CDC Guideline. Amidst these pressures, providers said they felt that the only way to protect themselves from liability was to stay rigidly at or below the CDC Guideline’s 90 morphine milligram equivalent threshold and to disregard the emphasis on individualized patient care and respect for patient consent that are recognized within the Guideline (see “Patients as Liabilities” for testimonies from providers).

The consequences for chronic pain patients have been real: many told Human Rights Watch they have been forced to quit working, limit their activities, and even in some cases remain housebound due to pain. Some patients said they suffered from intense anxiety and suicidal thoughts during and after the tapering process. Other patients said they faced increasing difficulty finding a doctor willing to accept them as patients because they were on high-dose opioids.

Current data are not available to more precisely indicate the impact involuntary tapering has on chronic pain patients’ physical and mental health. It is also unclear to what extent involuntary tapering and overall inaccessibility of prescription opioids drive illicit drug use, as the few studies on this issue are inconclusive about the causal relationship between the two.[76]

Faced with an overdose crisis of unprecedented proportions, federal and state governments have a duty to respond to protect people from accidental overdose death. Any policy to address the overdose crisis should consider and minimize potential unintended harms, including for patients suffering from chronic pain who have a medical need for opioid analgesics.

|

Involuntary vs. Voluntary Tapering Many thousands of chronic pain patients are currently on high-dose opioid analgesics.[77] For some, these medicines are a lifeline, improving their pain control and allowing them to take part in family, social or work life. For others, the medicines may offer little or no benefit. As the government tries to reduce the volume of prescription opioids in society, this raises complex questions about how to taper off patients who do not benefit from the medicines or get unnecessarily high doses. The 2016 CDC Guideline encourages obtaining buy-in from patients before initiating a taper, and says physicians should engage mental health specialists to help a patient manage potential anxiety, which may be due to the fear that their pain will return or to the fact that they are physically dependent on the medication and could suffer withdrawal. In a letter to Human Rights Watch, CDC officials clarified this position to mean that tapering patients from opioid medicines should always be voluntary, with their consent.[78] Despite this emphasis on consent, many patients report being tapered off their medication without their consent, and the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense Guideline on opioid prescribing seems to endorse involuntary tapering. In either scenario, patients face significant challenges tapering themselves to off opioids. One 2017 systematic review of 67 studies examined several strategies for reducing long-term opioid prescribing for chronic pain, including multidisciplinary pain care and close follow-up of patients, though it noted that such “team-based, intensive support would require additional resources to implement in primary care settings, where most opioids are prescribed.”[79] The study found limited evidence that patients’ pain became less severe or that their functionality or quality of life improved after tapering.[80] Another 2011 study that examined tapering chronic pain patients who had developed a substance use disorder found high failure rates but concluded that medication assisted treatment, such as buprenorphine, improved the patient success rate.[81] In its guideline, the CDC notes that there is a dearth of high-quality studies on different tapering protocols, but it recommends that primary care physicians adjust the pace of a taper to a patient’s needs, and collaborate with other medical professionals, such as mental health specialists, to manage anxiety that the taper might induce.[82] At the time of writing, few studies had examined outcomes of involuntary tapering on patients. A 2017 survey of 509 Veterans Health Administration chronic pain patients discontinued from opioid medication found that 47 patients (9.2 percent) exhibited signs of suicidal ideation, while twelve patients (2.4 percent) attempted suicide.[83] As the study only captured information reported to medical professionals and only followed patient outcomes for one year, this likely underestimates the actual number of such cases. The authors conclude that patients discontinued from prescription opioids, whether diagnosed with a substance use disorder or not, may require close monitoring and risk prevention. Another study suggests that patients who are involuntarily tapered off opioids are less likely to follow up in primary care than patients who aren’t (65 percent compared to 88 percent) and that “discontinuation of opioids may carry risks that should be thoughtfully assessed and managed.”[84] It is unclear how much research is currently under way to study tapering practices and their consequences. There should clearly be more research into safe methods of opioid tapering, and data should be captured on the consequences of denying adequate medical treatment to chronic pain patients, including in cases where those patients are involuntarily tapered. |

Patient Plight

Involuntary and Inappropriate Tapering of Patients on High Doses of Opioids

Twenty-six patients, mostly in Washington State and Tennessee, told Human Rights Watch that their healthcare providers had involuntarily tapered them or were in the process of doing so. A dozen providers, including both primary care providers and pain specialists, also mostly from those states, said that they were involuntarily tapering all patients who were on opioid doses above — and in some cases even those who were under — the 90 morphine milligram equivalent threshold described in the CDC. Another nine healthcare providers said that they were not planning to wean existing patients off opioids without their consent, but said that they had stopped accepting new chronic pain patients who required opioid analgesics, particularly those patients who were already on high-dose opioids.

Stephanie Miller, 49, told Human Rights Watch that she suffers from spinal stenosis (a narrowing of the spaces in one’s spine that puts pressure on nerves) and cervical radiculopathy (a pinched nerve in her neck), which give her bouts of sharp pain in her neck and an intense ache in her back that feels “like a rod in my spine.” Since 1998, the Washington State resident has been taking a daily dose of oxycodone equivalent to 315 MME, which she says helped her live a stable life. In January 2018, even though Miller had routinely submitted to urine drug testing, pill counts, and other kinds of screening, her provider told her she would have to reduce her dose to 90 morphine equivalents by June, because she feared losing her license if she continued to prescribe high doses.

The lower doses of oxycodone have significantly reduced her quality of life, Miller told Human Rights Watch, leading her to contemplate suicide:

I never had a pain-free life, but I could do little things like washing the dishes, not hiking or dancing. Now [with the reduced dose of medication] it’s: okay, I can’t vacuum today, can’t sweep the floor today. It’s changing everything and it’s terrifying….

I feel like I got a new diagnosis when I got that letter saying I should go down to 90 MME. It felt like a ticking clock for when my life was going to end. If it stays this way, I am going to end my life. I have a locked box where I keep my medications, and there is a note all ready that says I do not blame my providers, I blame the government.

I always thought I would keep fighting, but now I’m facing something that’s completely and totally out of my control. When I’m lying in my bed my heart is beating so fast I’m afraid of a heart attack. Why put it off?[85]

Miller’s health has declined so significantly that she can no longer shower on her own and required assistance taking care of her dog. Her Medicaid plan has since granted her 20 more hours with a home health aide per week.

|

Physical Dependence vs. Addiction Many of the chronic pain patients interviewed for this report have been receiving opioid analgesics for their pain over extended periods of time. That means that their bodies have gotten used to a regular dose of the medications and that abrupt discontinuation of the treatment can lead to withdrawal symptoms, just as would be the case with other prescription medications (or non-prescription substances such as nicotine). Common withdrawal symptoms include anxiety, agitation, aching, nausea and insomnia. The fact that a patient may face such symptoms if their medications are discontinued does not mean that they have a substance use disorder or are “addicted to pain pills.” The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) — a federal agency that works to advance research about and medical care for drug users — distinguishes between physical dependence, which occurs when a patient takes a certain medication over an extended period and is normal, and substance use disorder.[86] The latter is defined as compulsive drug use despite harmful consequences, including a failure to stop using the drug; failure to meet work, social, or family obligations; and sometimes tolerance and withdrawal. NIDA clarifies that “physical dependence can happen with the chronic use of many drugs — including many prescription drugs, even if taken as instructed.”[87] A similar distinction is made by a host of other US and international medical standards and institutions: the International Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (ICD-10), the Diagnostic Statistic Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association,[88] and the American Academy of Addiction Medicine.[89] The patients we interviewed all said that they used their medications as prescribed and almost all of them regularly underwent urine tests and pill counts, allowing their physicians to confirm that they took their medications as prescribed. They also told us that their medicines allowed them to participate in family life, social events or work. |

Bob Green, a 67-year-old retiree with the autoimmune disorder Sjogren’s disease, was involuntarily tapered beginning in January 2018 despite being compliant with his physician’s pill count and urine drug test requirements. Sjogren’s disease attacks the body’s mucosal linings, giving him dry eyes and mouth, as well as a “rust-in-the-joints type feeling.” It has exacerbated two previous army injuries. After a neck operation in 2012 his health “really went haywire,” he says. “For whatever reason that rust feeling has been so intense since the surgery — whether it’s directly related, I can’t tell you, but it seems like my nervous system just exploded on me…. I have pain in my back, feet, hands, arms.”

In 2012, he was referred to a pain specialist who prescribed him opioids to keep the pain under control while he was at his job: Green had plans to work until 70, and he worried that he could lose his house if he didn’t, he told Human Rights Watch. In 2016, the Department of Veterans Affairs approved Green for service-connected disability compensation, allowing him to retire earlier than planned. That decision couldn’t have come soon enough: soon afterward, his provider said that she would no longer prescribe him high-dose opioids because she feared punishment by federal law enforcement or state medical board authorities. Green said that he wouldn’t have been able to wean off opioids, which “keep [him] working at 110% and getting up at 5am every day,” if he was still at his job.

It [the weaning] has made my life really difficult, but what are my options?... I have to be grateful for the fact that the VA rated me as 100% service-connected disabled. When I officially retired I have the extra time to sit in a massage chair for half an hour in the morning, to do physical therapy and reiki. Do I have much of a life? No, I have about 10% of a life. The pain that I have pretty much keeps me housebound.[90]

Marty Revolloso, a Medicaid patient from San Antonio, Texas, was hiking in 2011 with friends when he slid on some gravel and fell off a cliff. Both legs were shattered and his left hand severed from his body: “The impact was so great it shattered my ankles, my feet, my shins, and the shock traveled up through my body and shattered my spine like a stack of bricks.”[91] He spent six months in a full-body cast to heal his spine, and his legs have undergone intensive reconstruction.

He suffers from severe pain which doctors have told him will persist for the rest of his life. Prescription opioids provide him some relief: for the past several years, he had been on 180 MME of medication, which he says allowed him to start working part-time in IT and taking online classes. “Before, the days would just blend together. I would get up to go to the bathroom, all I could do was just lie there day after day, it was like being in the hospital again,” he said. “When he [the doctor] increased my medications, my whole life changed — I didn’t even know I could make that kind of progress.”

According to Revolloso, in April 2018, the physician assistant at his doctor’s office said his dose would be cut back to half its current level, because his insurance provider for Medicaid would no longer cover it. Texas Medicaid has a policy that mandates opioid tapering down to 90 MME in 2018, which “will be applied for all clients, except for clients diagnosed with cancer or receiving palliative or hospice care.”[92]

Revolloso said that in the beginning, his clinic was unaware of the change. They attempted prescribe him a lower dose of 120 MME and obtain an override from the insurance company by sending a prior authorization. But when Marty went to the pharmacy, he said he realized the insurance company had rejected this attempt.

In a recorded phone conversation with his doctor’s office, a nurse explained the issue:

It’s not going to go through because [the insurer] is not paying for anybody to have a morphine equivalency over 90. We’ve had to do this for all our 500 to 600 patients of [this insurer], we haven’t been able to get anybody approved for a morphine equivalency over 90…. The only way to get a higher dose approved is if you have cancer.

We’ve had a lot of patients call and just tell us, because member services and the pharmacy services is telling them one thing, but when it comes down to us actually submitting the prior authorization they have denied every single one of them. The only way we’ve been able to get them approved is if we lower them to 90.[93]

Revolloso told Human Rights Watch that the change in medication wiped out much of his recovery: “I was flat on my back from the pain… I couldn’t eat, couldn’t get up, couldn’t bathe, I stank.” He later learned he could pay out of pocket for the medication he needed. But while the $120 he would have to pay might be a small price for some, Marty earns only $740 per month from disability payments. “It was a pretty big struggle, because it caught me totally off guard — this month at least I’ll be able to budget.” Human Rights Watch did not speak with Revolloso’s healthcare provider, because Revolloso said he feared that outside scrutiny might provoke his physician to terminate his care.

While in the above cases, health providers explained the rationale behind decisions to taper their patients off opioids without patient consent, this was not always the path taken by providers, some of whom dramatically reduced a patient’s dose involuntarily, sometimes without even holding an in-person consultation to explain the change.

Jennifer Vinnard of Vancouver, Washington, for example, found out that her prescription had been slashed by more than half from 250 to 100 MME when she showed up at the pharmacy one day for a refill, despite the fact that she had always been a compliant patient and underwent urine drug testing regularly. Vinnard had lifelong hip problems and in 2014 herniated multiple discs in her spine and underwent four surgeries, leading to crippling pain in her neck, for which she was prescribed opioids. After her visit to the pharmacy, she wrote to her provider, asking why her medication had been changed without warning. After several weeks’ delay, her provider finally sent her an email containing the following[94]:

The bottom line of these [CDC] guidelines is that all patient’s [sic] need to be around 100mg of morphine per day… I know you have done better with the way your regimen is but his [sic] is not going to be sustainable. In order to keep prescribing I need to make reductions… We as a clinic need to make changes if we are going to stay open.[95]

The dose reduction has changed Vinnard’s life for the worse: she recently bought a new home with her husband, but was unable to help set up the house because she is often in too much pain to help with even relatively simple chores: “Since the reductions, I have to wait for my husband to do even little things,” she says. “I sit in front of a space heater for hours each day, sit in the sun or take baths in an attempt to help the pain. But life doesn’t stop because I hurt.”[96]

Similarly, Robin Gordon, a 48-year-old veteran from Oakland, Tennessee who receives care from the VA, discovered her dose had been cut only when she received her monthly prescription in the mail. Gordon’s pain stems from a 1996 car accident in which she was hit in the driver side door after pulling out of an apartment complex. For about five years after her accident she didn’t experience much pain, but then things started going downhill: she had problems with the knee impacted by the crash and shooting pain down her neck. She has been diagnosed with degenerative disc disease and has tried nerve ablations, TENS units (a device that sends electrical impulses across the surface of the skin), and heating pads to manage the pain. She has been on opioid analgesics since 2005, at a current daily dose of 105 MME. “I don’t like pain medication, I’ve had family that was addicted and was always leery of it. But if it’s at the point where you have to be in a wheelchair you’re in so much pain, I’ll take the medication,” she said.[97]

But in May 2018, Gordon received fewer pills from her provider than usual: her dose had been cut back to 70 MME. While her provider had noted several times during office visits that opioids were risky, she never suggested that she would involuntarily taper Gordon, who had always complied with random urine drug testing. After Gordon sent an email requesting to know why her dose had been changed, she received a response from her physician, who referred her to the VA Opioid Safety Initiative (which includes the VA guideline for opioid prescribing),[98] and sent her several articles about pain management. But Gordon still felt caught off guard by the change, and found her health deteriorating. She told Human Rights Watch:

They should have done this with an in-person visit. I would have been happy with just a phone call. This is my life you’re playing with and you need to consult me first. I have plenty of other health problems, so this at least was stable.[99]

Gordon’s abrupt and nonconsensual tapering within the VA is not unique: Human Rights Watch spoke to three other veterans in Tennessee, all of whom had been tapered without an in-person consultation with their doctor first, and none of their providers had previously voiced concerns that they might be abusing their medication. Similar stories documented elsewhere in the media have shown that such rapid and unsupported changes in VA facilities appear to have resulted in suicide and drug overdose.[100]

Involuntary Tapering and Suicide

There is a well-studied correlation between chronic pain and suicidal behavior. Involuntarily tapering a patient, particularly those who have been on high-dose opioids for long periods, has major physical and mental health repercussions and has been shown to increase the risk of suicidal behavior. As noted above, one study found that 9.2 percent of involuntarily tapered patients reported suicidal thoughts to their healthcare provider while 2.4 percent attempted suicide.[101] The study’s authors say they believe that these incidents were underreported.

Even if medical practice has changed, and some patients put on high-dose opioids in the 1990s and 2000s would not be today, tapering is still difficult and anxiety-inducing for many patients and may leave them in uncontrolled pain. While there have been some efforts to document individual cases in which pain patients commit suicide following involuntary tapering, there have been no public efforts to study this issue more systematically.[102]

The provider who cared for Maria Higginbotham in Washington State, who was reducing dosages for more than 200 other patients, described the conversations he had with patients he was tapering:

It’s so difficult, it’s emotionally just stressful and time-consuming to explain this to patients every time they come in because it triggers lots of fear and anger. I don’t have a week that goes by that I don’t have at least one patient who insinuates that suicide is a possibility. We start talking about pain pumps and spinal cord stimulator implants, but most of them have already tried all the other medications. They’ve gone through all those things, and we feel like we’re limited as to what we can offer them instead.[103]

Tonya Schuler, a patient in West Virginia, was diagnosed with chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS) after a routine carpal tunnel surgery. The condition, which is typically the result of traumatic injury or the malfunctioning of the nervous system, causes severe pain and can even result in changes in skin temperature, color, or swelling in the affected limb.[104] Her pain management clinic in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania is currently weaning her down to a dose of 90 MME despite her concern that she could experience a dangerous increase in her heart rate — an issue common among CRPS patients[105] — as a result.

This is called the suicide disease, and I can see why, because I’m at the early stages of this. There is no way one person can live in this amount of pain. You can’t. You wonder, what’s your purpose?[106]

Abandoned Patients and Overwhelmed Physicians

Of the 44 patients interviewed by Human Rights Watch, ten were struggling to find care at the time they were interviewed. The reasons were varied: in two cases, the patient moved to a new state and was unable to find care. In two cases a physician retired, and in one case a provider ceased practicing without informing the patient why. In three cases, primary care providers determined they were no longer comfortable treating high-dose patients: these providers referred their patients to pain management doctors, but those patients were unable to find a doctor willing to take them on. In one case, a patient had weaned herself off opioids temporarily because she was pregnant — after her pregnancy, she could no longer find a doctor willing to treat her with opioids; and one patient with cancer had her pain medication managed by an oncologist, but upon completing treatment she struggled to find a pain doctor willing to care for her. One patient struggled to find care after the shutdown of his pain clinic, but was able to find care four months later.

Chronic pain patients spoke more generally of the increasing challenges they faced in finding health providers willing to care for them, but this was especially true for patients who required opioids for treatment. The patients who spoke to Human Rights Watch repeatedly said they felt abandoned by the medical community. They expressed anger and frustration over the fact that they felt stereotyped as drug-seekers when they visited a clinic or pharmacy. In many cases, they said the stigma of being a chronic pain patient on opioids had become so great that they avoided telling even close friends and relatives about their medication. In several cases, patients told us they were only able to find a provider a four- or five-hour drive away — a journey that they often had to make monthly to see their doctor or to pick up their prescriptions.

When pain specialist Dr. John Baumeister moved his practice from the suburbs of Seattle to a rural community in eastern Washington a few years ago, many of his patients found themselves unable to find care in the Seattle area. They are forced to make the more than three-hour journey from Seattle once a month to visit him: “Some 50 percent of my patients drive more than 225 miles to see me every two months,” he said. “They do this because doctors in the Seattle area are unwilling to prescribe opioids to chronic pain patients.”[107]

One of Dr. Baumeister’s patients is 51-year-old Nicole Rogers, who makes the journey every month. She has had arthritis and other related conditions since she was 25, and has received opioid medications, the only pain treatment that has provided her significant relief, since the 1990s. In 2014 she was diagnosed with stage-three breast cancer and received pain care from her oncologist. But after her cancer went into remission, she could not find any doctors willing to treat her for pain in the Seattle area: “It’s too hard to find a pain doctor who will prescribe medication, it’s almost impossible,” she said. “I can barely walk to my mailbox and that’s half a block, I’m suffering a lot, and now I have to drive four hours each way once a month.”[108]

One patient said that she felt abandoned by a provider with whom she had a long-term relationship and pushed toward clinics she did not trust. Gail Gray, a 52-year-old from the remote rural town of Celina, Tennessee, was diagnosed with degenerative disc disorder and spinal stenosis when she was 35, and has had four back operations in the last five years. Because other treatments did not provide adequate pain relief, her doctor prescribed low doses of morphine for her 15 years ago. After her second back operation in 2013, her primary care doctor raised her dose to approximately 450 MME in response to her increasing pain. In 2017, however, that same doctor began cutting her back 30 milligrams at a time, citing the CDC Guideline and his fear that the DEA could intervene in his practice. That doctor brought her down to 240 MME, but then said that he was no longer comfortable prescribing her any morphine at all and suggested she transfer her care to a pain clinic. She found a clinic one hour away, but worries that she has given up a caring doctor for a pill mill:

They don’t take any kind of insurance and it costs $175 per visit, cash…. I’m worried it’s a pill mill because they give minimal service and the visit only lasts 15 minutes. [The doctor] barely looked at me…. I’m not comfortable with this. I feel like he [my primary care doctor] has pushed me into doing something that’s not right, and I don’t want to break the law.[109]

Some healthcare providers told Human Rights Watch that they had been flooded with patients because nearby medical clinics had either been shut down or had closed their doors to chronic pain patients who had previously been prescribed opioids.

For example, Dr. Jon Olson[110] in Edmonds, Washington, who has practiced pain management for 33 years, said that his pain clinic had been flooded with patients, as pain clinics in his area shut down and primary care doctors stopped almost all opioid prescribing. Dr. Olson said he tried to employ a holistic approach with his patients, and that he spent 45 minutes or more with many of them. He told Human Rights Watch that he has had to delay retirement because his clinic, where he works with one other physician and a nurse practitioner, was unable to find a younger doctor willing to take over his patients.

Primary care in this neighborhood walked away from prescribing opioids permanently. This trend sped up in the last year and a half or two, when the CDC guidelines kicked in.