Summary

After almost 50 years of taking in hundreds of thousands of refugees from various neighboring states, Cameroon is shredding its reputation as a generous refugee-hosting country. Working to push back Nigeria’s militant Islamist group Boko Haram, which has secured an increasingly violent foothold in northern Cameroon since 2013, Cameroon’s military deems tens of thousands of Nigerian asylum seekers a threat to their security goal and has carried out a policy of mass forced return of this vulnerable population. The Cameroonian military’s aim seems to be to clear Nigerians out of the country and dissuade other would-be asylum seekers from seeking Cameroon’s protection.

Since early 2015, the Cameroonian authorities have summarily deported at least 100,000 Nigerians living in remote border areas back to war, displacement, and destitution in Nigeria’s Borno State. At least 4,402 are known to have been deported in the first seven and a half months of 2017. In carrying out these deportations, Cameroonian soldiers have frequently used extreme physical violence. Some, including children, weakened after living for months or years without adequate food and medical care in border areas, have died during or just after the deportations, and children have been separated from their parents.

The forced returns are a flagrant breach of the principle of nonrefoulement, binding on Cameroon under national Cameroonian as well as international law. They are also being carried out in defiance of UNHCR’s late 2016 plea to all governments not to return anyone to northeastern Nigeria “until the security and human rights situation has improved considerably.”

Since early 2015, Cameroon’s army has been aggressively screening newly arriving Nigerians at the border, subjecting some to torture and other forms of abuse, and containing them in far-flung and under-serviced border villages and informal refugee settlements, to which the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has been denied access. This policy of blocking asylum seekers from accessing protection has made it easier for Cameroon to deport them.

About 70,000 refugees able to reach Cameroon’s only designated camp for Nigerian refugees, in Minawao, have also faced violence at the hands of Cameroonian soldiers, have had limited access to food and water and are subject to abusive restrictions on their right to free movement. In April and May 2017, 13,000 returned from the camp to Nigeria, some of whom were killed in early September after Boko Haram attacked the Banki displacement camp where many had ended up.

To avoid complying with their basic obligations under refugee law to provide protection and assistance for tens of thousands of Nigerians seeking asylum in Cameroon, the authorities have refused to allow UNHCR to register their asylum claims and to process them for refugee protection in the border areas or, except in a few exceptional cases, to arrange for their transfer to Minawao where UNHCR can register them.

As of mid-2017, UNHCR had only been given sporadic access to some border communities to carry out basic pre-registration procedures, likely leaving tens of thousands of asylum seekers without access to protection and putting them at risk of unlawful forced return. The agency has repeatedly and unsuccessfully asked Cameroon to set up new transit centers to register newly arriving asylum seekers.

After staying publicly silent on the situation for two years, in late March 2017, UNHCR started to publicly criticize the authorities for their mass forced refugee returns. The decision to go public was triggered by ongoing forced returns, even after Cameroon had signed an agreement in early March with Nigeria and UNHCR committing both countries to voluntary refugee returns. As of mid-July, evidence on the ground confirmed that Cameroon has continued to unlawfully deport hundreds of asylum seekers at a time, although formally the authorities deny this.

On one occasion in late June 2017, the Nigerian authorities responded to Cameroon’s pressure by sending military vehicles over the border to help Cameroon deport almost 1,000 asylum seekers. Nigeria thereby became complicit in the unlawful forced return of its own citizens.

In late June and July 2017, Human Rights Watch interviewed 61 refugees and asylum seekers in Nigeria about the abuses they had suffered in Cameroon.

Those previously living in Cameroon’s border areas, particularly in or near Kolofata and Mora, spoke of shocking levels of physical violence perpetrated by Cameroonian soldiers between early 2015 and April 2017. They described how soldiers tortured and assaulted them and dozens of others on arrival and during screening procedures, accusing them of belonging to Boko Haram or being “Boko Haram wives.” They said soldiers closely controlled their daily movements, beating and extorting money under threat of detention and deportation as they tried to collect firewood. UNHCR says it has received similar reports from asylum seekers living in the border areas.

Asylum seekers also described to Human Rights Watch poor humanitarian conditions in the border areas, including limited access to food, and how they struggled to keep themselves and their families alive in the face of destitution exacerbated by exploitation. One woman described how soldiers promised to give women food and not deport them in exchange for sex with them.

Every person interviewed said that during their time in border villages, Cameroonian soldiers regularly rounded up dozens or hundreds of fellow asylum seekers, brutally beat them with wooden sticks and metal poles to force them onto trucks, and deported them. Some said they witnessed soldiers deporting dozens of groups involving hundreds of people. After living in constant fear of deportation, they then described how they suffered the same fate. Many said they saw other deportees, including malnourished children, die during their deportation.

Refugees previously and currently living in the Minawao refugee camp told Human Rights Watch about severe violence they suffered in the camp, particularly in 2015 when soldiers beat them and hundreds of other refugees during food distribution in the camp, resulting in deaths and injuries. Some also said soldiers severely beat them and others in 2016 and 2017, for example when they intercepted them as they attempted to collect firewood outside the camp, and tried to extort money from them.

Refugees who had lived in the camp spoke of poor humanitarian conditions there since 2015, including a reduction in food rations and a lack of clean water. Some also said they struggled to access adequate healthcare. Many said these conditions had pushed thousands to leave the camp and return to Nigeria in April and May 2017. However, in April 2017 water access significantly improved and the United Nations (UN) said it hoped to resume full food rations in October for three months.

On August 7, Human Rights Watch wrote to Cameroon’s Minister of Territorial Administration and Decentralization outlining this report’s findings and requesting comment. As of mid-September, we had received no response.

After the deportees are forced back to their country, the Nigerian army transfers them to militarized displacement camps or villages in Borno State where conditions are dire, and women and girls face sexual exploitation. These sites are in the midst of the ongoing conflict between Nigeria’s armed forces and Boko Haram which has displaced about 2 million other Nigerian civilians struggling to survive the violence.

The UN and aid groups in Nigeria have repeatedly appealed for an end to forced returns from Cameroon, saying it is too dangerous and that they do not have the capacity to respond to the massive needs of returnees. They have also called on the Nigerian authorities—who have repeatedly overstated limited improvements in the security situation in Borno—not to carry out plans to set up new displacement camps in insecure areas to deal with the mass returns from Cameroon.

International refugee and human rights law prohibits refoulement, the forcible return of refugees to persecution, and the forcible return of anyone, regardless of their legal status, to a real risk of torture. In addition, African regional refugee law prohibits the return of civilians to situations of generalized violence, such as the one that exists in northeastern Nigeria. Cameroon has bound itself to these prohibitions and incorporated them into Cameroonian law.

Cameroon has the right to regulate the presence of non-nationals on its territory and to prevent certain people from entering or remaining in Cameroon—including those viewed as a threat to its national security, such as members of Boko Haram. The authorities also have an obligation to carefully investigate any attacks carried out in the Far North Region by suspected Cameroonian or Nigerian members of Boko Haram.

However, Cameroon’s right to prevent individuals shown to pose a security threat from entering Cameroon does not mean the authorities may close their borders to asylum seekers, or block them from seeking asylum in Cameroon and then summarily deport them, or registered refugees, back to Nigeria. The failure to protect refugees and other abuses documented in this report appear to be driven by the Cameroonian government’s arbitrary decision to punish Nigerian refugees, based solely on their nationality, for Boko Haram attacks carried out in Cameroon’s Far North Region and to discourage Nigerians from seeking asylum in Cameroon.

Cameroon is also bound by its own laws and international law not to limit asylum seekers’ and refugees’ freedom of movement. However, the mid 2015 decision to require Nigerian refugees to live and remain in the Minawao camp to receive refugee status and assistance fails to comply with the limited permitted exceptions to this rule.

As of late July 2017, international donors had funded less than ten percent of UNHCR’s appeals for their Cameroonian operations on behalf of refugees from the Central African Republic and Nigeria. This significant shortfall risks sending Cameroon a message that donor governments do not care what happens to Nigerian refugees and that Cameroon should deal with the significant challenges it faces in protecting and assisting refugees on its own. This is unlikely to encourage the authorities to be tolerant of Nigerian refugees and stop abusing them.

To help put an immediate end to the abuses described in this report, the Cameroonian and Nigerian authorities, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the United Nations, including UNHCR, and donor countries should take a number of urgent steps.

The Cameroonian authorities should immediately instruct the military authorities to stop deporting Nigerian asylum seekers and refugees and should investigate and prosecute any soldiers who have committed acts of violence against asylum seekers and other abuses. They should swiftly register Nigerian asylum seekers, recognize those who pass security screening procedures as refugees, and let them live in Cameroonian communities or refugee camps that respect their right to free movement.

In line with UNHCR’s official position on returns to Nigeria, the Nigerian authorities should unambiguously and publicly recognize that the security and humanitarian situation in Borno State means that it remains unsafe for Nigerian refugees to return from Cameroon.

UNHCR should maintain its June 2017 decision to publicly report every month on forced returns from Cameroon and should include in those reports information on Cameroonian military abuses against Nigerian refugees and asylum seekers. UNHCR should also transparently report on the extent to which the Cameroonian authorities allow UNHCR to register asylum seekers living in Cameroon’s border areas with Nigeria and assist them in those areas or transport them to the Minawao camp.

The Special Rapporteur on Refugees, Asylum Seekers, Internally Displaced Persons and Migrants in Africa of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights should call on Cameroon to immediately end the abuses set out in this report, request to visit Cameroon’s border areas with Nigeria and the Minawao camp, and issue a public report on the extent of abuses faced by asylum seekers and refugees.

Finally, donor governments should immediately improve on their extremely weak response in 2017 to UNHCR’s financial appeals for Nigerian refugees in Cameroon and other countries in the region. They should also raise the abuses set out in this report with the Cameroonian authorities, call on them to put an immediate end to these practices and to fully cooperate with UNHCR in assisting and protecting all Nigerian asylum seekers and refugees in Cameroon.

Recommendations

To the Government of Cameroon

- Instruct the military authorities to end the unlawful forced return of Nigerian asylum seekers and refugees in the border areas and Minawao refugee camp.

- Investigate allegations of soldiers’ abuse, extortion, and sexual exploitation of asylum seekers and refugees and prosecute any against whom there is evidence of having committed crimes.

- Introduce rigorous monitoring and reporting procedures regarding the military authorities’ respect for refugee rights in the border areas and Minawao camp.

- Swiftly register all Nigerian asylum seekers, and recognize as refugees those who pass security screening; alternatively, after screening, allow UNHCR to register and recognize them.

- Allow Nigerian asylum seekers and refugees to live in Cameroonian communities, expand the congested Minawao camp or establish additional camps where they can receive adequate assistance while respecting their right to free movement.

- Ensure that the enforcement of policies aimed at protecting legitimate national security concerns do not prevent Nigerian asylum seekers from entering Cameroon.

To the Government of Nigeria

- Unambiguously and publicly say that the security and humanitarian situation in Borno State means that it remains unsafe for Nigerian refugees to return there from Cameroon.

- Publicly commit not to repeat Nigeria’s June 2017 complicity in Cameroon’s forced return of almost 1,000 asylum seekers from Kolofata.

- Instruct officials to interview returnees about abuses suffered in Cameroon and publicly condemn them until they have ceased.

- Do not force returning refugees to live in militarized camps, settlements or other areas that risk being attacked by Boko Haram.

To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- Continue UNHCR’s March 2017 decision to publicly condemn forced return of Nigerian asylum seekers and refugees from Cameroon and its June decision to publicly report each month on the number of such deportations.

- Continue to press the Cameroonian authorities to allow UNHCR protection staff to access all communities hosting Nigerian asylum seekers to interview them directly about abuses they have suffered or forced returns of other asylum seekers they have witnessed.

- In Nigeria, interview returned asylum seekers about abuses they suffered in Cameroon at the hands of military personnel, including during deportations, and publicly report on UNHCR’s findings.

- Provide regular and transparent public updates on the extent to which the Cameroonian authorities allow UNHCR to register asylum seekers in Cameroon’s border areas with Nigeria and recognize and protect them as refugees in those areas or in Minawao camp.

- If Cameroon refuses to allow UNHCR to carry out the above tasks, press the UN Humanitarian Coordinator to raise the issue privately and, if needed, publicly with the Cameroonian authorities.

To the United Nations Humanitarian Coordinator in Cameroon

- Work closely with the Cameroonian authorities and UNHCR to put an end to the abuses documented in this report and to ensure UNHCR can effectively monitor and report on any further abuses, and swiftly register and effectively protect Nigerian asylum seekers and refugees.

To the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights Special Rapporteur on Refugees, Asylum Seekers, Internally Displaced Persons and Migrants in Africa

- Call on Cameroon to immediately investigate and end the abuses set out in this report and to discipline or charge any soldiers found to be responsible.

- Call on Cameroon to respect its international and African regional obligations to ensure that all asylum seekers can access Cameroonian territory to claim and receive asylum and move freely in Cameroon.

- Request to visit Cameroon’s border areas with Nigeria and the Minawao camp and issue a public report on the extent of abuses faced by asylum seekers and refugees.

To Donor Governments Providing Support to UNHCR and to Cameroon

- Generously respond to UNHCR’s financial appeals relating to its operations in Cameroon on behalf of refugees from the Central African Republic and Nigeria.

- Raise the abuses set out in this report with the Cameroonian authorities and call on them to investigate and put an immediate end to these practices.

- Call on the Cameroonian authorities to ensure that all asylum seekers can access Cameroon’s territory to claim asylum and that they are swiftly registered and allowed to live in safe local communities or are taken to Minawao or other refugee camps that respect their right to freedom of movement.

- Encourage the Cameroonian authorities to allow UNHCR to carry out protection monitoring in the border areas and the Minawao camp and publicly report on any allegations of abuses against asylum seekers and refugees, including by military personnel.

Methodology

Between June 23 and July 5, 2017, Human Rights Watch interviewed 61 Nigerian asylum seekers and refugees, including 49 men, ten women and two girls, about abuses and humanitarian conditions they faced in Cameroon. We interviewed 25 Nigerian asylum seekers who had been denied access to asylum and deported by Cameroonian authorities in late 2016 and 2017, 20 Nigerian refugees who returned to Nigeria from Cameroon’s Minawao refugee camp in April and May 2017 and 16 Nigerian refugees still living in the Minawao camp who spoke with Human Rights Watch in Nigeria on the Cameroonian border.

All interviews were conducted individually and in private. They were conducted in English, Hausa and Kanuri, without interpreters. We explained the purpose of the interviews and gave assurances of anonymity. We also received interviewees’ consent to describe their experiences. No interview subject was paid or promised or provided a service or personal benefit in return for their interviews.

Human Rights Watch spoke with nongovernmental (NGO) and United Nations (UN) humanitarian agencies on both sides of the border. We also met with a number of Nigerian officials and, in Cameroon, with Yap Mariatou at the Civilian Protection Division of the Ministry for Territorial Administration and Decentralization.

On August 7, 2017, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Cameroonian Minister for Territorial Administration and Decentralization, René Emmanuel Sadi, outlining our findings and requesting comment. As of mid-September, we had received no reply.

I. Background

Fight Against Boko Haram and Regional Humanitarian Crisis

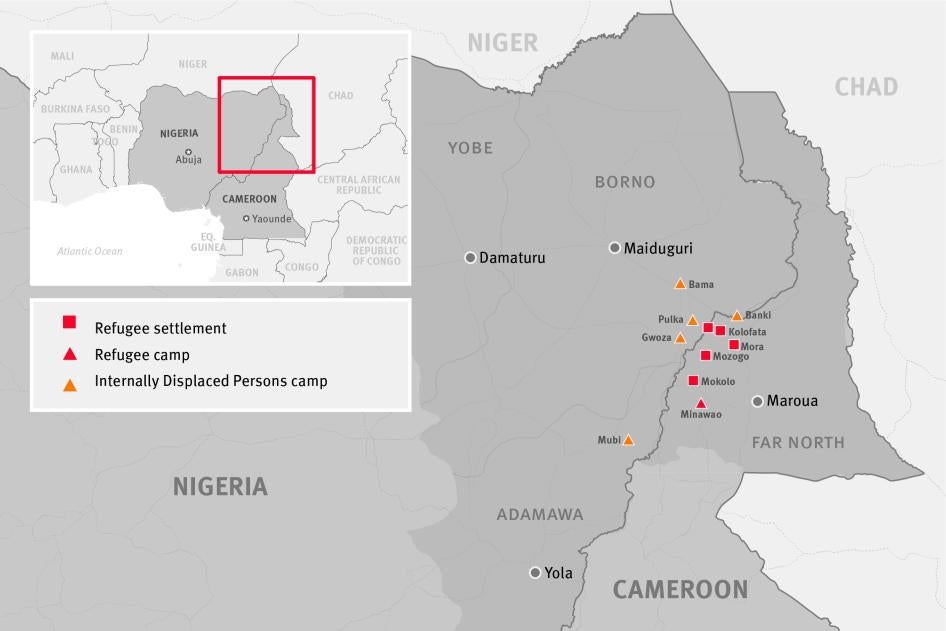

Cameroon is one of three countries neighboring Nigeria paying a heavy price for the eight-year-old Boko Haram uprising in northeastern Nigeria. By 2014, Boko Haram had firmly established itself in the long-neglected Far North Region of Cameroon, and then launched attacks on the Cameroonian military and civilians.[1] Since then, the conflict has internally displaced 220,000 Cameroonian citizens and tens of thousands of Nigerian refugees have fled to Cameroon.[2]

In response to the conflict, several countries, including Cameroon, have collaborated to combat Boko Haram, most recently under the umbrella of the Multinational Joint Task Force against Boko Haram (MNJTF).[3] Its mandate includes, among other things, to ensure internally displaced people (IDPs) and refugees can return home.[4]

Since 2014, the Cameroonian armed forces have also carried out their own operations against Boko Haram in the Far North Region, during which monitoring groups have documented numerous human rights violations, including torture, against Cameroonians and Nigerians suspected of working with Boko Haram.[5]

Cameroonian officials have not publicly accused Nigerian asylum seekers or refugees of working with Boko Haram. However, almost all of the international aid agency officials and diplomats interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Cameroon said that Cameroonian officials in closed door meetings in 2017 had increasingly said they considered the presence of Nigerians in Cameroon a grave security threat.[6] In late July, UNHCR’s Assistant High Commissioner for Protection, following meetings with government officials in Cameroon and Nigeria, said that he “stressed the need to set up a mechanism that can both address legitimate security concerns and the protection needs of refugees.”[7]

To date, Cameroon has provided no evidence that Nigerian asylum seekers living outside Minawao refugee camp or refugees in the camp have been involved in any attacks in Cameroon.[8]

Cameroon’s Refugee-Hosting History

Cameroon’s reputation as a generous country towards refugees dates back to 1972 when it took in over 20,000 refugees who had fled from Equatorial Guinea, with tens of thousands more arriving in the following years.[9] By 1982, the country sheltered 200,000 refugees from Chad.[10] As they started to leave in 1982, tens of thousands more refugees arrived, this time from Rwanda, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Central African Republic (CAR). According to UNHCR’s statistical database, until the early 2000s, Cameroon consistently hosted approximately 50,000 refugees from those countries. In the early 2000s, refugees arrived from the Central African Republic, with about 230,000 in Cameroon by the end of July 2017, bringing the total number of refugees of all nationalities, including almost 100,000 officially registered Nigerians, to just under 350,000.[11]

In September 2016, Cameroon’s President Paul Biya addressed the Leaders’ Summit on Refugees on the side-lines of the 71st Session of the UN General Assembly in New York, saying Cameroon “is a haven for people seeking peace and safe refuge,” that his “government has taken measures to provide decent living conditions” for all 350,000 refugees of “different nationalities” in Cameroon, and that Cameroon was “determined” to “provide to persons in distress, dignified reception and living conditions.”[12]

As of late July 2017, donors had funded only six and nine percent of UNHCR’s appeals for the CAR and Nigerian refugee crisis respectively.[13] The lack of international donor response to both appeals risks sending a message to Cameroon that the country is on its own when it comes to refugee protection, which risks encouraging Cameroon to continue to try to limit the number of Nigerian refugees reaching and staying on its territory.

II. Abuses Against Nigerian Refugees in Cameroon

Since 2009, Nigerians have fled the Boko Haram insurgency to Cameroon, although the numbers only increased significantly in 2013, when the authorities set up a refugee camp in Minawao, about 70 kilometers from the Far North regional capital Maroua. In mid-2015, the Cameroonian authorities said only Nigerians living in the camp would be considered refugees, but have blocked UNHCR from identifying and transferring asylum seekers in the border areas to the camp. The camp has sheltered tens of thousands in often poor conditions, which include food and water shortages and violence by Cameroonian soldiers against the refugees living there. At least tens of thousands of other Nigerians have been living in villages and towns near the Nigerian border, blocked from seeking asylum and forced to live in appalling conditions. Many have been tortured, or otherwise abused. Since 2015, tens of thousands have been unlawfully deported.

Violence, Conditions and Encampment in Minawao Refugee Camp

In response to the Boko Haram crisis, the Cameroonian authorities set up the Minawao refugee camp in June 2013, with a capacity to shelter 20,000 people, and allowed asylum seekers to travel to the camp.[14] Starting in 2016, newly arriving Nigerian asylum seekers who manage to reach the vicinity of the camp go through security screening at the Gourenguel transit center, about five kilometers from the camp.[15] UNHCR registers those given security clearance as refugees based on their Nigerian nationality, proof of a risk of persecution in their country of origin and lack of links to armed groups, and transfers them to the camp.[16] Unknown numbers have been deported from the center.[17]

As of early September, it sheltered 58,394 people, mostly from the towns of Banki and Pulka in Nigeria’s Borno State.[18]

After an attack on the town of Maroua about 70 kilometers from the Minawo camp in June 2015, Cameroonian authorities regularly started blocking newly arriving asylum seekers in the border areas from reaching the camp and have regularly blocked UNHCR from transporting asylum seekers there, while exceptionally allowing others to proceed.[19]

As of mid-2017, UNHCR remained in “discussions” with local authorities lasting for weeks, trying to convince them to allow all newly arrived asylum seekers to travel to the camp to register as refugees.[20]

In late June and early July 2017, Human Rights Watch interviewed 16 refugees living in the camp and 25 refugees who had returned to Nigeria from the camp in late 2016 and 2017.[21] Refugees described to Human Rights Watch violence by Cameroonian soldiers in the camp, mostly in 2015, but also in 2016 and 2017, as well as extortion and arbitrary detention in the vicinity of the camp. Refugees also described poor living conditions in the camp, including significant food shortages beginning in 2015 and a lack of clean water, which progressively worsened through June 2017. Many described a climate of fear in which they could not raise their concerns with camp officials out of fear of violent retaliation by Cameroonian soldiers.[22]

Violence in Minawao camp

In private, individual interviews, 11 refugees described, in strikingly similar terms, 11 separate serious incidents of violence by Cameroonian soldiers against hundreds of refugees in the camp during food distributions in 2015. Four refugees described different incidents where they said that they saw 20 other refugees assaulted so badly that they died of their injuries.[23] In each case, they said that refugees were severely beaten because they asked soldiers basic questions, including about why their food rations had been further reduced and when the food shortages would end.

A 43-year-old man from Zamga, Borno State, who arrived in the camp with his brother in late 2015 said Cameroonian soldiers in the camp physically and verbally attacked refugees lining up to collect their food:

They humiliated us like animals and beat us like we were slaves. They beat my 22-year-old brother so badly with a wooden stick on his head and his chest that he later died of internal bleeding.[24]

A 42-year-old man said:

In 2015 … a pregnant woman lost her place in the food line. When she pleaded with an official to let her back in, a soldier attacked her with a big stick. She fell to the ground and started bleeding. I later heard that she died before she reached the clinic.[25]

UNHCR says it is unable to corroborate these allegations of violence in Minawao in 2015.[26]

Refugees also spoke of ongoing military violence in and near the camp in 2016 and 2017.

An 18-year-old man said that throughout 2016 and 2017, Cameroonian soldiers in the camp were increasingly undisciplined. He said they were frequently drunk and assaulted refugees in different parts of the camp for no apparent reason.[27]

Cameroon’s constitution reflects key provisions of international and African regional human rights treaties to which Cameroon is party and guarantees all people in Cameroon, including refugees and asylum seekers, protection of their right to life, physical integrity, freedom from all forms of torture, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment, freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention, and protection from arbitrary interference with their property without discrimination on the grounds of national origin or any other status.[28]

Cameroonian soldiers’ violence against refugees breaches Cameroon’s constitution and Cameroon’s international and regional legal obligations.

On August 4, 2017, UNHCR organized a training session for security forces in the Minawao camp focusing on “preventing refugee rights violations.”[29]

Conditions in Minawao camp

Since May 2015, according to a UNHCR official, the camp has been “operating beyond maximum capacity” and “the congestion makes it challenging to provide sufficient quantities of potable water, prevent outbreaks of diseases, and provide services and assistance that are in line with minimal international humanitarian standards.”[30] In early June 2017, UNHCR said that the Cameroonian authorities were blocking asylum seekers at the border because the Minawao camp was full.[31] Cameroon has repeatedly rejected UNHCR’s proposals since 2016 to set up a second camp for Nigerian refugees.[32]

All 41 refugees Human Rights Watch interviewed about life in the Minawao camp described poor conditions there, including increasingly serious food shortages beginning in 2015 and limited or no access to potable water. Some said they struggled to access healthcare. Many said that they felt camp officials did not listen to any of their concerns.[33]

The vast majority of refugees interviewed said their food rations steadily decreased beginning in 2015 and that by 2016 they and their children were going hungry. Some said they believed camp officials were misappropriating food and that refugees were given considerably less food than the official ration. Others described how rice rations were replaced with corn rations, which made many sick.[34] Refugees also told Human Rights Watch an exodus of thousands of refugees from the camp in April and May 2017 was in protest of the food shortages in the camp at that time and the lack of hope in rectifying long-term food shortages.[35] In January 2017, the World Food Program had to cut food rations in the camp by 25 percent due to a lack of funding.[36] It hopes to resume 100 per cent rations in October 2017 for at least three months.[37]

Thirteen refugees said that they had no, or very limited, access to potable water and were forced to drink water from what they said were contaminated streams.[38] Access to safe drinking water in Minawao was limited and precarious in 2015 and 2016, but a new water piping system completed in April 2017 significantly increased water access to just below the minimum required threshold of 20 liters per person per day.[39] Nine refugees said they had struggled to access health care services in the camp.[40] However, two charities providing health care have increased their services in the camp since early 2015 and have provided a range of services to refugees.[41]

Breach of Refugees’ Right to Freedom of Movement

Until mid-2015, refugees could informally move in and out of the camp. But shortly after the Maroua attacks, local authorities took administrative measures, stopping refugees’ freedom of movement and “enforcing a strict encampment policy for Nigerian refugees. Since then they have maintained that only those who are in or arrive in Minawao camp are considered as refugees.”[42] The decision was not formally announced in writing nor, to Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, has it been formally sanctioned by senior officials in the capital, Yaoundé.[43]

Six refugees described to Human Rights Watch how Cameroonian soldiers had intercepted them outside the camp in 2016 and 2017 while collecting firewood or while looking for food outside the camp, told them they should return to the camp, and extorted money from them under threat of detention. Three said that soldiers beat and detained them when they failed to pay and later released them once they had arranged payment.[44]

“To me,” one refugee told Human Rights Watch, “Minawao is like a modified prison for refugees.”[45]

Cameroonian and international law guarantees refugees’ right to freedom of movement.[46] Under international human rights law, refugees should be treated like Cameroonian nationals, and there should be no discrimination based simply on their legal status.[47] Any restrictions should be justified by one or more of the following aims: national security, public order, public health or morals, or the rights and freedoms of others.[48]

The UN Human Rights Committee has said that the “application of restrictions [on freedom of movement] in any individual case must be based on clear legal grounds and be necessary and proportionate.”[49]

As a result, any restriction must be clearly and precisely set out in national law to avoid any arbitrary and abusive decisions.[50] For any limitation on free movement to be “necessary,” it should be based on one of the above aims, respond to a pressing public or social need, and be proportionate to that aim.[51]

The Human Rights Committee has said that to be proportionate, restrictions “must be appropriate to achieve their protective function; they must be the least intrusive instrument amongst those which might achieve the desired result; and they must be proportionate to the interest to be protected.”[52]

To identify the least intrusive measure, a government should balance three factors: the extent of the restriction, including the length of the time of the restriction and the numbers affected; the impact on people’s exercise of the right affected, and any other negative impact on their lives; and the desired legitimate aim.[53]

Cameroon’s de facto encampment policy fails to meet any of the criteria above. The policy as such discriminates between Cameroonian citizens and refugees, because it allows the former to move and denies that right to the latter, without objective reason for the denial of the right to move. There is no Cameroonian law setting out the precise criteria under which the authorities have the power to restrict refugees’ free movement. The authorities have failed to say why they are restricting the movement of almost 60,000 refugees in Minawao, and why doing so is necessary to achieve any of their aims. Finally, they have failed to show how restricting all of Minawao’s refugees to the camp is a proportionate measure to achieve a legitimate aim.

Nigerian Asylum Seekers outside Minawao Camp Denied Protection and Abused

Since 2013, when the Cameroonian authorities set up the Minawao camp, they have required that Nigerian asylum seekers live in the Minawao camp if they are to be recognized as refugees and to receive aid. Any Nigerians living outside the camp, including those unable to reach it by their own means or blocked from doing so by the authorities, have not been entitled to register as asylum seekers and be recognized as refugees, and were left to fend for themselves in towns and villages.[54] All 25 asylum seekers Human Rights Watch interviewed about their time in Cameroon’s border areas said they lived under the constant threat of deportation, until they were finally deported.[55] This policy of blocking asylum seekers from accessing protection has made it easier for Cameroon deport tens of thousands of asylum seekers since mid-2015.

Blocking Registration of Nigerian Asylum Seekers

Cameroonian law provides that the authorities must register all asylum seekers.[56] However, Cameroon has both failed to put in place its own procedures to comply with this obligation and has blocked UNHCR from doing so, resulting in what one aid official working in the Cameroonian border areas called “a black hole” in refugee protection.[57]

In 2015 and early 2016, UNHCR repeatedly sought government approval to register Nigerian asylum seekers living outside the Minawao camp, but was told all Nigerian refugees should report to the camp.[58]

In April 2016, the authorities finally agreed to set up “joint protection committees,” also referred to as “joint committees,” involving UNHCR and local officials in three border departments of the Far North Region to help “strengthen collaboration” between UNHCR and “the local authorities on refugee protection,” in particular, relating to “access to asylum” and “screening and registration of refugees.”[59] As of the end of June 2017, UNHCR said that the joint committees “are now being dispatched to identify and eventually register out-of-camp refugees.”[60] By the end of June, UNHCR had also “pre-registered” some asylum seekers, which at most involved taking their photos, but had not received the Cameroonian authorities’ permission to take fingerprints or note other personal details needed to complete asylum seeker or refugee registration.[61] The authorities have only sporadically allowed UNHCR to arrange for transportation of some asylum seekers to the Minawao camp.[62]

Cameroonian authorities first allowed UNHCR to pre-register about 20,000 Nigerians living in Mogode and Makary villages and Kousséri town in November 2016, but then blocked UNHCR staff from registering them on an individual basis.[63] Nonetheless, as of early June 2017, none had been deported to Nigeria.[64]

In March 2017, the Cameroonian authorities allowed UNHCR to pre-register a group of a few hundred Nigerian asylum seekers, after which local authorities screened the group for security purposes. The authorities agreed that the group could travel to the Minawao camp, but then blocked the process just before the vehicles were due to make the journey.[65]

In June 2017, UNHCR identified 1,271 Nigerians in Mayo Tsanaga Division, but suspended registration after the local prefect blocked the process on June 23.[66] Between mid-June and mid-August, UNHCR pre-registered 16,848 Nigerians in the Logone-et-Chari Division.[67]

The authorities have consistently blocked UNHCR from identifying Nigerians in Mayo-Sava Division, which includes the town of Kolofata from which Cameroon deported almost 900 asylum seekers in late June 2017.[68] In 2017, Cameroon’s Rapid Intervention Battalion also blocked all other humanitarian groups from reaching Nigerians in Mayo-Sava Division, stressing no agency was allowed to give them shelter materials or take them to Minawao refugee camp.[69] In other locations, such as the Madina and Mozogo communes, both the Cameroonian military and local prefects have banned aid agencies from accessing Nigerian asylum seekers.[70]

As a result of these sporadic registration procedures, in late June 2017 UNHCR said at least 33,000 “Nigerian refugees” lived “in villages near” the Minawao camp.[71] This is similar to the number identified in surveys by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which has concluded that between February 2016 and mid-May 2017, the number of unregistered Nigerians in the Far North Region of Cameroon rose from 11,482 to 30,278.[72] That number was based on interviews IOM conducted with heads of household, who gave the number of people in their household.[73]

Both UNHCR and IOM say the true number of Nigerians in Cameroon living outside Minawao camp is likely far higher, which is borne out by the almost 100,000 deported from those areas between 2015 and mid-2017.[74]

At the end of 2016 and throughout the first half of June 2017, UNHCR was mired in protracted negotiations to convince national and local authorities to allow UNHCR access to register Nigerian asylum seekers in various locations in Cameroon’s border area with Nigeria.[75] UNHCR says it has repeatedly asked, but been refused permission to screen for refugee status undocumented Nigerians arrested for illegal presence and scheduled for deportation.[76]

In January 2017, UNHCR summarized the consequence of Cameroon’s failure to establish proper reception, screening, and registration procedures for newly arriving Nigerian asylum seekers:

A lack of transit centers in the Logone-et-Chari and Mayo Sava Divisions, [which are] far from the Minawao refugee camp, forces refugees to disperse into villages the length of the border, where they get local people’s help. However, they are exposed to protection risks, in particular refoulement, especially for those without any identification documents.[77]

In February 2017, the UN Resident Coordinator in Cameroon appealed to the Minister for Territorial Administration and Decentralization, René Emmanuel Sadi, to set up four new transit centers where newly arrived Nigerian asylum seekers could seek asylum and have their claims processed.[78] In April, the Governor of Cameroon’s Far North Region rejected the proposal and said he would only set up “way stations” in Mora (Mayo Sava Division), Boukoula (Mayo-Sava Division) and Fotokol (Logone-et-Chari Division) for the purpose of refugee repatriation to Nigeria and that he did not want to open transit centers for newly arriving asylum seekers.[79]

As of the end of June, the Cameroonian local and national authorities had still not agreed, leaving UNHCR and international donors “whose resources are at the ready … still pushing” for such centers.[80]

On June 29, Human Rights Watch met with Yap Mariatou, the head of the Civilian Protection Division of the Ministry for Territorial Administration and Decentralization. In response to questions about whether Cameroon was blocking UNHCR from registering Nigerian asylum seekers, she said, “UNHCR is free to register them, like in the east [of Northern Cameroon] where it registers refugees from the Central African Republic, but it is UNHCR’s choice not to do so [in the west].”[81]

At the end of August, UNHCR agreed with the authorities to open one “transit center” in Boukoula, but said its purpose was to “receive Nigerian refugees requesting to return voluntarily” to Nigeria. The agency also said the authorities planned to open three more, and that the centers would also serve to help “put in place different protection activities.”[82]

Torture, Abuse, Extortion and Poor Conditions for Nigerian Asylum Seekers

Cameroon’s refusal to allow tens of thousands of Nigerian asylum seekers to seek protection since 2015 has facilitated Cameroonian soldiers abuse of them in remote and hard-to-access border regions without any consequences. Nigerian asylum seekers described to Human Rights Watch, and to UNHCR, how Cameroonian soldiers tortured and repeatedly and seriously assaulted or extorted money from them and others. Such abuses occurred shortly after they had arrived in Cameroon during security clearance procedures, during their stay in border villages and during their deportation. One woman described how soldiers sexually exploited women in return for food and promises not to deport her and others. All deportees also described dire humanitarian conditions they were forced to endure in remote border areas where aid agencies have limited access.

Torture, Other Violence, Sexual Exploitation, and Extortion

Eleven asylum seekers who had lived in Cameroon’s border areas with Nigeria in 2015, 2016, and 2017 said Cameroonian soldiers tortured or assaulted them and dozens of others on arrival and during screening procedures in a number of villages, particularly in Kolofata and Mora, but also in Kirawa, Mokolo and Mozhogo. Most said soldiers accused them and other asylum seekers of belonging to Boko Haram. Most said the soldiers only spoke French, but some said some of them spoke English.

One man said that six of his friends with whom he entered Cameroon disappeared soon after they arrived in Kolofata in January 2015 and that a local Cameroonian man later told him Cameroonian soldiers had killed them as Boko Haram suspects.[83]

A 42-year-old man from Kumshe, Borno State, described how Cameroonian soldiers tortured him – to obtain a confession – in the village of Sahoda in late January 2017:

The soldiers found a group of us Nigerians and told us to roll on the ground. Then three soldiers beat us on our heads with sticks, a fourth soldiers stamped on our heads with his boots and a fifth whipped our heads with a cable. Then one of them clipped the end of my penis with a pair of pliers and told me to confess that I was Boko Haram. I just don’t know how to describe that pain.[84]

A 37-year-old man from Kirawa, Borno State, explained how Cameroonian soldiers had assaulted him just after he crossed to Cameroon near Kirawa in November 2014, breaking his hand, and how they again assaulted him in Kolofata in March 2015, accusing him of belonging to Boko Haram. He then described a third incident in which they detained and assaulted him in October 2016:

Soldiers arrested four of us in Kolofata and took us to a prison. They chained us up in a tiny filthy room and said we were members of Boko Haram. They beat us every morning with hard wooden sticks and didn’t give us any food. By the end we were covered in maggots. Then they just let us go.[85]

A 30-year-old woman from Gwoza described what happened to her after she had walked for two days to reach the Cameroonian border near the village of Kolofata in mid-2015:

When they saw me from a distance, the soldiers raised their guns up and told me to stop … They shouted in French [and] … then one of them came closer and used his hands to say I should raise my hands, [but] before I could raise them he slapped me three times and pushed me to the ground… After they had checked us, they shouted, "Boko Haram women, we will finish you. Then they let us go."[86]

A 25-year-old woman who was separated from her husband and children during a Boko Haram attack against her Borno village of Darajamal and who arrived in Kolofata in late 2015 said:

As soon as I told the [Cameroonian] soldiers that I didn’t know where my husband was, they put me in a tent with other women and said I was a ‘Boko Haram wife.’ They kept me there for four days without food or water and it was really terrible. Three soldiers attacked me. They beat my breasts with a stick and slapped me, saying I should tell them when my husband was planning to attack Cameroon. At one point I thought I would die when a soldier kicked me very hard in my groin.[87]

A 33-year-old man from Banki who arrived at the Cameroonian border near Mora in early 2015 said:

I was investigated by Cameroonian soldiers for seven days before they said I could stay in Mora. That week they beat me every day and called me a Boko Haram member and all sort of names.[88]

Five other asylum seekers described lengthy and violent security screening procedures and said that Cameroonian soldiers shouted at them in French for hours at a time each day and that all they could understand were the words “Boko Haram.”[89] Three asylum seekers, including two women, said Cameroonian male soldiers strip searched them and others in front of hundreds of fellow asylum seekers.[90]

A 19-year-old woman from Gwoza reached the Cameroonian village of Kerawa in late 2015 where she and thousands of other Nigerian asylum seekers faced dire living conditions. She said:

The soldiers took advantage of women. They said that if we had sex with them, they would give us food and protect us. If we refused, they would come the next day to where you lived. They took away lots of men and women as Boko Haram suspects. Other times, they deported people to punish them because you said no. I know 18 women who agreed to have sex with the soldiers because of this and three of them got pregnant.[91]

Five asylum seekers described to Human Rights Watch how Cameroonian soldiers policing the border villages in which they lived in 2016 and early 2017 stopped them when collecting firewood, beat them, and extorted money from them under threat of detention.[92]

An 18-year-old-woman from Gwoza said “sometimes we couldn’t eat the little food we had because we had no firewood to cook. The soldiers would stop us collecting wood, beat us, and said we had to give them money or they would detain us. It happened to hundreds of us.”[93]

UNHCR says that it has “received similar reports from refugees” of these abuses “and has no reason to doubt the refugees’ stor[ies].”[94] UNHCR also says it has made “various efforts to correct this situation, especially though advocacy, sensitization campaigns and refugee protection and human rights training.”[95] At the end of August, UNHCR said it specifically targeted senior law enforcement officials, including from the army and police, for training in basic refugee protection principles, including “the rights of refugees, the principle of nonrefoulement, the humanitarian character of asylum, child protection and gender based violence.”[96]

Cameroon denies that its soldiers have committed any abuses against Nigerian refugees.[97]

Cameroon’s constitution guarantees all people in Cameroon, including refugees and asylum seekers, freedom from all forms of torture and inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment.[98]

The definition of torture in the UN Convention against Torture, to which Cameroon is also a party, provides that torture is “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him … information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by … a public official…”.[99]

Cameroonian soldiers’ violence against refugees, including the infliction of pain and suffering to obtain confessions for belonging to Boko Haram, breaches Cameroon’s constitution and Cameroon’s international legal obligations.

Dire Humanitarian Conditions for Asylum Seekers in Border Areas

Nigerian asylum seekers denied refugee status and protection have been stuck for years in informal refugee settlements, where they have received minimal assistance from the local and military authorities, and, sporadically, from international agencies.

All 25 asylum seekers interviewed by Human Rights Watch described the appalling conditions in which they lived, trying to keep themselves and their families alive.[100] Three asylum seekers said that their children died of malnutrition and poor health during their time in the border areas. Six said they had seen between three and 14 other sick deportees, including children, die during the deportation process or in the Banki displacement camp in Nigeria after they had returned, because they were in such poor conditions after months or years without proper food and medical care.[101]

III. Cameroon’s Mass Forced Refugee Return

Since mid-2015, Cameroon has forcibly returned tens of thousands of Nigerian asylum seekers and refugees in breach of its national and international legal obligations. Victims say they and hundreds of others were brutally beaten during the deportations and some were separated from their relatives. In March 2017, Cameroon signed a Tripartite Agreement in which it committed to ensuring that Nigerian refugees will only return voluntarily to their country, yet since then it has continued to deport thousands, drawing repeated public criticism from UNHCR which continues to call on all States not to return anyone to northeastern Nigeria “until the security and human rights situation has improved considerably.”[102]

Prohibition of Forced Refugee Return

Under its Immigration Law, the Cameroonian authorities have the right to regulate who is present on their territory and may prevent certain categories of people from entering or remaining in Cameroon, including those deemed to be a threat to national security.[103]

Despite these legitimate security concerns, Cameroon and international law obliges Cameroon to allow asylum seekers access to its territory to seek asylum and prohibits their refoulement—forcible return—to a place where a person would face a threat to life or freedom on account of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.[104] International law further prohibits the refoulement of anyone, whatever their status, to a situation where they would be at real risk of torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.[105]

Applying the refugee definition in the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (African Refugee Convention), Cameroonian law also provides that any non-Cameroonian in Cameroon has the right not to be returned to a place where “the person’s life, physical integrity, or liberty would be threatened on account of external aggression, occupation, foreign domination, or events seriously disturbing pubic order….”[106] Mass expulsions of non-nationals are prohibited.[107]

Cameroonian law also provides that in the case of a mass influx, the authorities can automatically recognize asylum seekers as refugees (“prima facie refugee”) and, if it chooses, can then verify each individual’s refugee status at a later stage.[108] Nigerians registering in Minawao with UNHCR are automatically granted status in Cameroon on this prima facie basis.[109]

Cameroonian law provides that the authorities are responsible for the registration of all asylum claims, including reviewing appeals, and granting refugee status.[110] In practice however, UNHCR registers Nigerian refugees in the Minawao camp.[111]

Forced Refugee Return

Until mid-2015, UNHCR received relatively few reports that Nigerians were being forcibly returned from Cameroon.[112] But that changed after a series of attacks took place in July 2015 in Maroua, the main town in the Far North Region of Cameroon, located about 70 km from the Minawao refugee camp.[113] Since then, in UNHCR’s words, “refoulement has continued unabated.”[114]

Mass Forced Return Between June 2015 and December 2016

In mid-2017, UNHCR said that since July 2015, “Nigerians who crossed into Cameroon without reaching Minawao camp were pushed back to Nigeria by Cameroonian security forces in considerable numbers.”[115] In a separate document, UNHCR put a precise figure on the “considerable numbers,” reporting that monitoring by “protection focal points” in the border areas identified 12,000 such pushbacks in 2015, and just over 76,500 in 2016.[116] Given 12,000 were deported in early August 2015 alone, the number for the whole of that year is likely to have been significantly higher.[117]

UNHCR in Cameroon works with the international NGO “Intersos” and with local “Mixed Protection Committees” to identify such deportation cases.[118] UNHCR says it “did not have access to most of these people [deported since early 2015] in order to determine their status, screen and register them.”[119]

Separately, since 2014, UNHCR and the Nigerian authorities have registered “returning refugees” leaving Cameroon, almost all of whom were not in fact registered as refugees. Between January 2015 and June 30, 2017, they recorded 212,334 such returnees from Cameroon.[120] Of these, just over 16,500 returned in 2015, 136,875 returned in 2016 and 59,609 did so in the first half of 2017.[121]

Cameroon has refused to set up asylum seeker registration centers in the border areas or to organize safe onward transportation to Minawao camp or safer towns and villages. This means UNHCR and its partners have been unable to monitor and count the exact number of Nigerian asylum seekers that Cameroon has arrested and deported before they could seek protection. The number of asylum seekers forcibly returned from the border areas could therefore potentially be higher than the UNHCR numbers.

According to UNHCR, “most forced returns have occurred from the Cameroonian border towns of Bourha, Kolofata and Fotokol” and that starting in 2015, this was the result of the “Cameroonian authorities and security forces … systematically return[ing] to the border Nigerian refugees living outside Minawao camp in the border areas of the Far North region, … especially around the towns of Fotokol and Kousséri [in] Logone-et-Chari department, and of Mora and Kolofata [in] Mayo-Sava department.”[122]

Among numerous examples, UNHCR cites the deportation of 338 Nigerian asylum-seekers, mainly women and children, whom Cameroonian authorities deported from Kolofata back to Nigeria on June 14, 2016:

The incident occurred just days after Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria adopted the Abuja Action Statement on protection in the Lake Chad Basin crisis, and reaffirmed among others, the importance of the principle of non-refoulement (non-return).[123]

UNHCR noted that in mid-December 2016, Cameroon had forcibly returned 1,500 people from the villages of Kirawa and Kolofata to Banki in Nigeria, adding to an already dire situation for those trapped in the internally displaced persons camp in the town that was to get even worse in 2017.[124]

Continued Forced Return in 2017

Despite numerous public and private pleas by UNHCR, NGOs, and diplomats to Cameroonian authorities to end the forced return of Nigerian refugees, the returns continued in 2017. By mid-July 2017, Cameroon had forcibly returned at least 4,402 Nigerian asylum seekers and refugees, of whom about 2,000 were deported in March alone.[125]

In February, UNHCR reported that Cameroon had deported 517 Nigerian asylum seekers to Banki between February 10 and 15, including 204 intercepted in Kolofata and 313 intercepted in Kirawa.[126] Similarly UNHCR said that on March 27 and 29, Cameroon intercepted or rounded up and deported 135 Nigerian asylum seekers, as well as 129 undocumented Cameroonians, from the villages of Bia, the border crossing point of Kolofata, and the Kolofata informal refugee settlement.[127]

On March 21, in UNHCR’s first press release since mid-2015 condemning Cameroon’s refoulement, the agency said that UNHCR teams in Nigeria had documented:

“Cameroonian troops returning refugees against their will - without allowing them time to collect their belongings [including] one incident on March 4 [in which] some 26 men, and 27 women and children were sent back from the … town of Amtide, in Kolofata district, where they had sought refuge.”[128]

At the end of May, UNHCR noted that “the 3,400 people refouled so far this year are primarily from the Cameroonian communities of Kerawa and Kolofata in the department of Mayo-Sava” which “have recently recorded a high number of security incidents.”[129] UNHCR stressed the fact that the 3,400 included a group of 430 refugees who had been “pre-screened by UNHCR and the Joint Protection Committee” and who were waiting to be transferred to the Minawao camp.[130] UNHCR told Human Rights Watch that it had already organized vehicles to take the refugees to the camp, but that the authorities deported the group at the last minute.[131]

UNHCR also noted that in addition to “the random round up and return of refugees in villages,” unknown additional numbers of “new arrivals [are] stopped at the border areas and sent back to Nigeria on [the] grounds that Minawao camp is full to capacity with no room for new arrivals.”[132]

In June, Boko Haram increased its attacks in Cameroon.[133] On June 2, two suicide bombers killed nine Cameroonian civilians and injured another 31 in Kolofata.[134] On June 10 and 11, five attempted suicide attacks failed in and near Kolofata and the nearby town of Mora.[135] And on June 24, the governor of Far North Region said 15 suicide attacks had “killed dozens” in Mora and Kolofata since June 14.[136]

Agencies and government officials told Human Rights Watch that at a June 19 meeting in Kolofata, Cameroonian authorities told Nigerian military authorities to take back a group of 887 Nigerian asylum seekers in Kolofata that same day. Just over half of these asylum seekers were children and all had arrived that month.[137] The Nigerian military authorities said they needed instructions from Abuja, and Cameroon gave them one week to take the group back.[138] Cameroon rejected UNHCR’s request to take the group to the Minawao refugee camp and on June 27, the Nigerian military authorities sent six vehicles to Cameroon to help the Cameroonian police return the group to Nigeria, where they were taken to the IDP camp in Banki. [139] It was the first recorded incident in which Nigeria helped Cameroon forcibly return Nigerian asylum seekers.[140]

Deportations continued in July, including the forced return of “85 Nigerian refugees” on July 16 from Kolofata.[141]

Abuse at Hands of Cameroonian Soldiers During Forced Returns in 2017

Each one of the 25 Nigerian asylum seekers previously living in Cameroon’s border areas whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said Cameroonian soldiers summarily deported them to Nigeria in 2017, together with hundreds of other asylum seekers. Thirteen also said that Cameroonian soldiers regularly came to places where asylum seekers congregate, forced dozens or hundreds of them onto trucks, and took them to the Nigerian border.[142] Their accounts therefore likely represent thousands of asylum seekers removed under such circumstances. Seventeen of the 25 said they were brutally beaten, or saw others brutally beaten, during their deportation.[143] Five also said that they saw fellow deportees badly injured in the back of military trucks as a result of the speed with which the Cameroonian soldiers drove along poorly maintained roads, causing them to slam their heads against the ceiling.[144]

Most said that the soldiers deporting them gave no reason for the deportation, while seven said soldiers told them they had to leave Cameroon because the refugee settlement they were living in had become overcrowded.

Four said that they were separated from relatives because of the speed and violence with which the Cameroonian soldiers carried out their deportations. Six said they were taken from the border areas, held for between one and four nights in the Minawao refugee camp, or possibly in the nearby transit camp at Gourenguel, and then deported.[145]

Typical of many, a 22 year-old-man from Nigeria’s Gwoza town described his deportation from Mora in March 2017:

Suddenly one morning at 6 a.m., the Cameroonian soldiers rounded up 41 of us men and severely beat us and then forced us onto a bus. They beat some of the men so badly, they were heavily bleeding. When we got to the Nigerian border near Banki they shouted at us, “Go and die in Nigeria.”[146]

A 49-year-old man describing his deportation from Mora in April 2017 said that Cameroonian soldiers “beat me with big stick all over my body in front of my wife and children and then forced us into a truck like animals without even letting me say goodbye to my family.[147]

Refugee Returns from Minawao Camp Between April and June 2017

Between mid-April and mid-June 2017, just over 13,000 Nigerian refugees living in the Minawao camp decided to return to Nigeria, travelling in civilian trucks and escorted by the Cameroonian military.[148] The majority originated from the town of Pulka and surrounding areas.[149] Almost all ended up living in dire humanitarian conditions in Nigerian displacement camps.[150] Before April, almost no refugees had left Minawao camp to return to Nigeria, prompting concerns about the reasons for the sudden return movement.

As noted above, nine refugees told Human Rights Watch that thousands of refugees left the camp in April and May 2017 to protest food shortages there and because they felt that attempts to express their frustration to camp officials had fallen on deaf ears.[151]

Some returning refugees also told UNHCR and another aid group in Nigeria that they had left Minawao due to the increasingly difficult living conditions there, saying that poor shelter, a cut in their World Food Program (WFP) food rations, and a lack of clean water in the camp had contributed to their decision to return.[152]

However, aid agencies working in the camp and those interviewing returnees in Nigeria say they have struggled to understand why the refugees decided to leave the camp and have identified various other reasons why they returned to Nigeria.[153]

Some returning refugees told aid agencies in Nigeria that fellow refugees in the Minawao refugee camp had told them in April and May 2017 they would lose the opportunity to register for local elections in Borno State if they didn’t return to Nigeria immediately.[154] One senior aid official said Nigerian officials from Pulka visited the camp in early 2017 to speak with refugee leaders about the importance of returning to vote in elections.[155] Returning refugees taken by the Nigerian military to the Banki displaced persons’ camp between April and June 2017 were registered to vote.[156]

Other confidential sources concluded that beginning in early March 2017, the Cameroonian soldiers began seriously restricting the movement of refugees between the camp and surrounding areas, extorting money from those caught outside the camp, and preventing them from collecting firewood.[157]

In early June, UNHCR said it had received information “indicat[ing] that refugees [in the camp] have been swayed to believe that conditions are back to normal in their areas of origin” and that “they can safely resume economic activities and are therefore making arrangements to return before the planting season.”[158] And in early July, UNHCR concluded that “self-organized returns … must be stopped … as there seem to be several reasons behind the persuasion of individuals to return, including some level of misinformation.”[159]

According to various aid agencies in Cameroon and Nigeria, UNHCR’s reference to refugees being “swayed to believe,” “persuasion” and “misinformation” related to Nigerian religious refugee leaders in the camp convincing refugees that it was safe and in their interest to return to Nigeria.[160] None of the agencies were able to say whether the leaders had been encouraged by the Cameroonian or by the Nigerian authorities to persuade refugees to return.[161]

At the end of June, UNHCR reported that 1,300 of the refugees who left Minawao had returned to the camp where UNHCR re-registered them.[162]

Two aid agencies interviewing returnees in Nigeria in April and May said that very limited information in the Minawao camp meant returnees had “no idea” about the true conditions they would face in Nigeria and that once in Nigeria they were surprised by the lack of aid, restrictions on their movement and poor security in most parts of Borno State.[163] Returning refugees taken to the military-controlled Banki displacement camp in Nigeria told one agency that refugee leaders had told them they would be taken straight to their home areas, but after realizing they would instead be stuck in Banki, they concluded they should have stayed in Cameroon.[164]

Agencies said that limited mobile phone coverage on both sides of the border, and almost non-existent radio coverage of localized humanitarian and security conditions in Nigeria, meant it was hard for refugees to stay informed about conditions in their home areas in Nigeria.[165] However, according to the main representative of refugees in the Minawao camp, refugees there can hear about security and humanitarian conditions in Nigeria’s Borno State by listening to two Nigerian radio stations based in Maiduguri broadcasting in English, Haoussa and Kanouri.[166]

On March 2, 2017, Cameroon, Nigeria and UNHCR signed a Tripartite Agreement for the Voluntary Repatriation of Nigerian Refugees Living in Cameroon (Tripartite Agreement).[167] Under the agreement, Cameroon, Nigeria and UNHCR undertook to ensure that “the repatriation of refugees …. will be done solely on the basis of their freely expressed will and on relevant and reliable knowledge of the prevailing situation in Nigeria,” that this applied to refugees “who spontaneously return” to Nigeria, and confirmed that UNHCR has the “supervisory and coordinating role” to ensure the voluntary repatriation of Nigerian refugees in Cameroon.[168]

As a result of the unexpected return of refugees from Minawao in April and May 2017, UNHCR began “an awareness-raising strategy to prevent spontaneous departures” from the Minawao camp. The campaign involved informing refugees about “the difficult conditions prevailing in the localities of return, mainly Bama, Pulka, Gwoza and Banki in Nigeria” and UNHCR said “it would continue and expand in scale … throughout the coming months until conditions for return are deemed conducive by the Tripartite Commission” set up under the Tripartite Agreement.[169] UNHCR focused on “security conditions and access to basic services in the different return areas [and] … target[ed] both individual refugees as well as community leaders.”[170] In August, UNHCR clarified that these activities are not designed to prevent spontaneous departures, but to ensure that any refugees returning to Nigeria are doing so “fully informed of the prevailing conditions and risks” in Nigeria.[171] There were no further returns to Nigeria from the camp between late June and early September.[172]

UNHCR Response to Cameroon’s Mass Forced Returns

UNHCR first started receiving reports of refoulement in 2014. Throughout 2015 and 2016 the agency documented how the Cameroonian authorities pushed back tens of thousands of Nigerians and denied UNHCR access to register them. Nonetheless, the agency stayed publicly silent. In July 2016, UNHCR’s Assistant High Commissioner for Protection wrote to the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralization to express his concern at the mass pushbacks.[173] In September 2016, UNHCR’s representative in Cameroon told the International Crisis Group that forced repatriations had ceased since 2016, despite UNHCR collecting evidence throughout the year of tens of thousands of deportations.[174]

As noted above, on March 2, 2017 − a day after a new UNHCR representative took over as head of UNHCR’s Cameroon operations − Nigeria, Cameroon, and UNHCR signed a Tripartite Agreement to regulate the voluntary return of Nigerian refugees from Cameroon.[175]

According to a number of senior aid officials, UNHCR didn’t agree to sign the agreement because it thought that conditions in Nigeria had improved to the point that it should prepare for refugee returns from Cameroon. Instead, the agency signed in the hope that the agreement would help put pressure on Cameroon to reduce the mass deportations it documented in 2015 and 2016.[176]

But within days of the signing of Tripartite Agreement, Cameroon forced back more asylum seekers.[177]

Shortly after, UNHCR took the decision to criticize Cameroon publicly. On March 21, UNHCR condemned Cameroon for unlawfully forcing back “over 2,600” refugees in 2017, citing specific incidents, including one that took place just two days after Cameroon had signed the Agreement. [178]

Two days later, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi, wrote to Cameroon’s President Biya to express his concern over Cameroon’s continued forced return of Nigerian refugees.[179]

On May 31, UNHCR published two documents summarizing its assessment of Cameroon’s forced return of just over 90,000 Nigerian refugees since January 2015, as well as concerns relating to the “spontaneous return” of Nigerian refugees from Minawao camp to Nigeria in April and May 2017.[180] The number of forced returns was not referred to in any subsequent press releases and has therefore received no media coverage.[181]

UNHCR also said it intended to issue a forced returns update at the beginning of each month.”[182]

On June 1, UNHCR publicly said its Nigeria staff and Nigerian government representatives who visited Minawao refugee camp in Cameroon at the end of May had found that “some forced return and denial of asylum … had taken place.”[183]

In early June, UNHCR said it had “on several occasions sought clarification from the Government of Cameroon on reports of forced returns of thousands of Nigerians, including letters addressed to the Governor of the Far North region by UNHCR’s sub-office in Maroua.”[184]

On June 21, the High Commissioner published a press release in his name saying he was “extremely worried” about a further almost 900 Nigerians leaving the Minawao refugee camp to return to increasingly desperate humanitarian conditions in Banki and stressing that refugees were returning to “a situation dangerously unprepared to receive them.”[185] The press release did not mention the 12,000 or so refugees who had returned from the camp to Nigeria in April and May 2017.

At the agency’s late June 2017 “Standing Committee” meeting, UNHCR’s Assistant High Commissioner for Protection took the unusual step of singling out a specific country for its abuse of refugee rights, saying:

We have seen some egregious instances of refoulement in contravention of fundamental international obligations, in spite of our interventions to prevent them. It is deeply concerning that this core of international protection is being undermined. I am particularly concerned about an incident we became aware of this morning in which 800 refugees were returned to Nigeria from Cameroon.[186]

On June 29, a UNHCR press release condemned Cameroon’s forced return of 887 refugees from Kolofata, called on Cameroon and Nigeria “to refrain from further forced returns,” and “repeated its appeal to … Cameroon … to allow newly arrived Nigerian refugees to reach Minawao camp.”[187]

And on July 26, UNHCR called for increased international donor funding for its operations in Nigeria, saying that “many of the … returnees are unable to go back to their homes due to security concerns and end up being displaced again, in dire humanitarian conditions.” UNHCR’s Assistant High Commissioner for Protection also stressed that additional money would allow it to “increase its presence in border locations and improve border and protection monitoring,” a clear reference to the need for UNHCR to better monitor refugee pushbacks and deportations at the Cameroonian border. Finally, he noted that he had “received assurance that action had been taken to stop involuntary returns.[188]

In addition to UNHCR’s response, the UN’s Humanitarian Coordinator in Cameroon also wrote to the Minsters of External Relations and of Territorial Administration and Decentralization, in June 2016 and January 2017 respectively, to express concerns on “reports of refoulement.”[189]

Cameroon’s Position on Forced Returns

Faced with mounting evidence from UNHCR of large-scale forced refugee return, Cameroon has adopted a combative stance, claiming it has not forced back a single Nigerian refugee.

On March 29, 2017, Cameroon’s Minister of Communication, Issa Tchiroma Bakary, said UNHCR’s condemning Cameroon’s forced refugee return was “unjust and unacceptable” and that it “threatened to stain [Cameroon’s] image [as a] unanimously recognized” place that “welcomed refugees.”[190] In late June, the Head of the External Relations Ministry’s Protocol Unit, Richard Etoundi, said, “there were no forced expulsions.”[191]

On June 29, Human Rights Watch met Yap Mariatou, the head of the Civilian Protection Division of the Ministry for Territorial Administration and Decentralization. In response to questions about whether Cameroon was engaged in mass forced refugee return, she said, “Nigeria is rich and they are not doing their job looking after their own people.”[192]

This response echoes statements made by members of Cameroon’s Rapid Intervention Brigade to aid officials in Cameroon, who said they deported Nigerians from the border areas because Nigeria was rich, had lots of room, and should take care of its own people.[193]

IV. The Situation of Returned Refugees in Nigeria

Nigerians forced back to their country end up in extremely poor conditions in militarized displacement camps or villages, surrounded by the ongoing Boko Haram insurgency which continues to attack and kill people in camps. The Nigerian authorities have overstated limited improvements in the security situation in Borno State and have said they want to see hundreds of thousands of displaced Nigerians return to their homes soon.

Continued Conflict and Humanitarian Crisis in North East Nigeria

The Boko Haram insurgency, and the resulting conflict, has driven millions of Nigerians from their homes in northeastern Nigeria, the vast majority in Borno State.[194] As of the end of August 2017, about 650,000 were living in saturated displacement camps while about 1,110,000 were living in other settlements, villages, and towns.[195]

As of early July 2017, the Nigerian security forces claimed they had “defeated” Boko Haram, despite plenty of evidence to the contrary.[196] The security situation in the northeast, including most of Borno State, remained dire, with “incidents of suicide explosions and attacks on military and civilian infrastructure including education institutions and IDP camps … a daily concern.”[197] In the first week of September alone, Boko Haram attacks on displacement camps killed at least 18 people.[198]

In June 2017, IOM reported that since October 2015, just over 1.25 million IDPs in Adamawa, Borno and Yobe states had returned to their “place of habitual residence prior to displacement.”[199]

However, UNHCR warned in late 2016 that “ongoing return of IDPs is not being carried out in a manner that guarantees [their] security and safety … and access to essential services.”[200] At the same time, a leading aid agency in Borno State also warned that many IDPs have returned to their areas of origin after receiving false promises of aid there or to escape appalling conditions in their displacement camps.[201] And in July 2017, UNHCR again warned that “the anticipated improvement in access and conditions in areas of return have not eventuated, and areas of return in northern Nigeria remain largely inaccessible to civilian populations for security reasons [while] those returning have ended up in secondary displacement…”[202]