Summary

Now when I think back to the war, …we were not as frightened as now. Fear of a bomb, fear of a bullet–it’s something we could live with…. But this … utter humiliation–I just cannot deal with it, I’m ashamed of myself. Every day, they take away another piece of my dignity…. It’s like always walking a mine field, always…waiting for them to drag you away.

-Resident of Chechnya, July 2016

For close to a decade, Ramzan Kadyrov, the leader of Russia’s Chechen Republic, has steadily tried to eradicate all forms of dissent and gradually built a tyranny within Chechnya. Kadyrov has been in this post since 2007 by virtue of appointment from the Kremlin, but he now faces elections for the head (governor) of Chechnya scheduled for September 2016. In the months before those elections local authorities have been viciously and comprehensively cracking down on critics and anyone whose total loyalty to Kadyrov they deem questionable. These include ordinary people who express dissenting opinions, critical Russian and foreign journalists, and the very few human rights defenders who challenge cases of abuse by Chechen law enforcement and security agencies. The increasingly abusive crackdown seems designed to remind the Chechen public of Kadyrov’s total control and controlling the flow of any negative information from Chechnya that could undermine the Kremlin’s support for Kadyrov.

Residents of Chechnya who show dissatisfaction with or seem reluctant to applaud the Chechen leadership and its policies are the primary victims of this crackdown. The authorities, whether acting directly or through apparent proxies, punish them by unlawfully detaining them—including through abductions and enforced disappearances— subjecting them to cruel and degrading treatment, death threats, and threatening and physically abusing their family members. These abuses also send an unequivocal message of intimidation to others that undermines the exercise of many civil and political rights, most notably freedom of expression. Even the mildest expressions of dissent about the situation in Chechnya or comments contradicting official policies or paradigms, whether expressed openly or in closed groups on social media, or through off-hand comments to a journalist or in a public place, can trigger ruthless reprisals.

This report documents a new phase in the Chechnya crackdown and is based on 43 interviews with victims, people who are close to those who paid a price for their critical remarks, as well as with human rights defenders, journalists, lawyers, and other experts.

In one case documented in this report, a man died after law enforcement officials forcibly disappeared and tortured him. In another, police officials unlawfully detained, threatened, and ill-treated a woman and her three children in retaliation for her husband’s public remarks criticizing the authorities. Police officials beat the mother and the eldest daughter, age 17, and threatened them with death, in an effort to force them to persuade the father to retract his critical comments. In another five cases documented in this report, law enforcement and security officials, or their apparent proxies, abducted people and subjected them to cruel and degrading treatment; four of those individuals were forcibly disappeared for periods of time ranging from one to twelve days.

The authorities subjected five of the people whose cases are documented in this report to public humiliations, in which they were forced to publicly apologize to the Chechen leadership for their supposedly false claims and renounce or apologize for their actions. In Chechen society public humiliation and loss of face can lead to exclusion from social life for the victim and his or her extended family.

Human Rights Watch is aware of other similar cases of abuse against local critics but did not include them in this report because victims or their family members specifically requested us not to publish their stories or because we could not obtain video materials and other evidence to confirm their accounts. There is also little doubt that some abuses against local residents in Chechnya may never come to the attention of human rights monitors or journalists because the climate of fear in the region is overwhelming and local residents have been largely intimidated into silence.

The Chechen leadership has also intensified its onslaught against the few human rights defenders who still work in the region and provide legal and other assistance to victims of abuses. In the wake of the 2009 murder of Chechnya’s leading human rights defender, Natalia Estemirova, only one human rights organization, the Joint Mobile Group of Human Rights Defenders in Chechnya (JMG) had been able to stay on the ground in Chechnya to provide legal assistance to victims or their family members in cases of torture, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions by law enforcement and security agencies under Kadyrov’s de facto control. However, towards the end of 2014 the Chechen leadership seemed determined to push JMG out of Chechnya. In the past two-and-a-half years law enforcement officials or their apparent proxies have on three occasions ransacked or burned the JMG’s offices in Chechnya, thugs who appear to be acting as Chechen authorities’ proxies have physically attacked JMG’s activists numerous times, and the pro-Kadyrov Chechen media has engaged in a massive smear campaign against the group. JMG withdrew its team from Chechnya in early 2016 for security reasons.

Chechen authorities have also been making it increasingly difficult for journalists to work in Chechnya. They have fostered a climate of fear in which very few people dare talk to journalists, except to compliment the Chechen leadership. And journalists who persevere with Chechnya work also find themselves at greater risk. This report documents a recent case of a journalist receiving threats, including death threats, another of a journalist who was arbitrarily detained while investigating a story, and a third case of a violent attack against a group of visiting journalists.

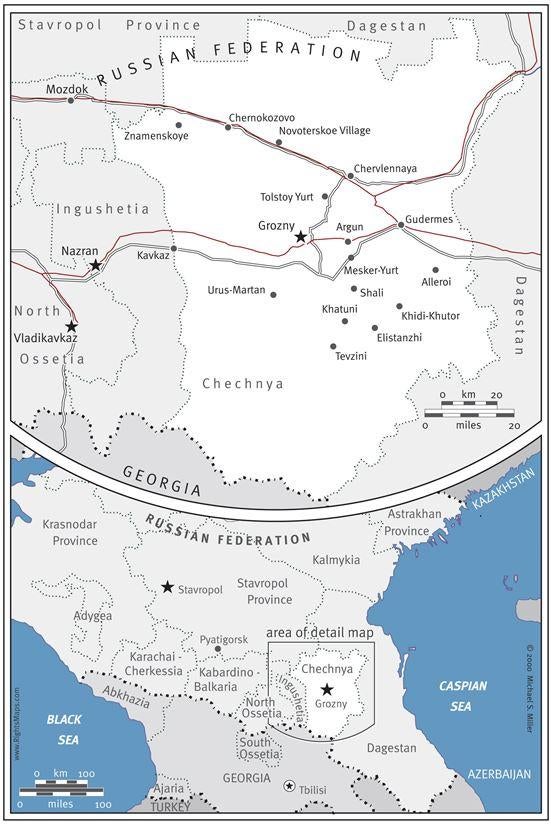

In March 2016 a group of masked men attacked a minibus driving a group of Russian and foreign journalists from Ingushetia to Chechnya, dragged the journalists from the bus, beat them, and set the bus on fire. The attack was so shocking that it triggered an immediate, unprecedented reaction from President Vladimir Putin’s press secretary, who called it “absolutely outrageous” and said that the law enforcement should ensure accountability for the crime. However, at this writing, the investigation, to the extent there is an active one, into the attack has not yielded any tangible results.

One of the key requirements of a free and fair election is for the public and media to be able to express their views, including those critical of the authorities, without fear of reprisal. With authorities engaged in severe and sweeping repression, ordinary people in Chechnya and local media simply cannot express their views freely.

The Chechen Republic is a “subject,” or administrative unit, of the Russian Federation, and its authorities are duty bound to uphold the rights and fundamental freedoms enshrined in Russia’s domestic legislation and international human rights obligations. Russia’s leadership is clearly aware of the extent to which Chechen authorities have violated human rights, including freedom of expression. But it has done little more than issue rare words of concern. Human Rights Watch calls on the Russian government to ensure Chechen authorities fully comply with Russia’s legislation, including Russia’s obligations under international human rights law, and put an immediate end to the crackdown on free expression in the pre-election period and beyond. Russian authorities need to provide effective security guarantees to victims and witnesses of abuses and bring perpetrators of abuses to justice.

Recommendations

To the Government of the Russian Federation

- Ensure all Chechen authorities, including law enforcement and security agencies, fully comply with Russia’s domestic legislation and international human rights obligations.

- Ensure Chechen authorities put an immediate end to the crackdown on free expression by Chechen authorities.

- Ensure Chechen authorities immediately stop collective punishment and public humiliation practices in Chechnya.

- Ensure victims have effective access to meaningful remedies and accountability mechanisms for violations of human rights, including cruel and degrading treatment, arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances, punitive house-burnings, and other violations perpetrated by security services and law enforcement agencies.

- Bring perpetrators of abuses to justice and ensure transparency regarding investigations and/or prosecutions undertaken, including their outcome.

- Provide effective security guarantees to victims and witnesses of abuses.

- Ensure effective implementation of European Court of Human Rights rulings on Chechnya including by bringing perpetrators of violations to justice and taking concrete steps to prevent similar violations from reoccurring.

- Foster a favorable climate for journalists and human rights defenders to do their work in the region.

To Russia's International Partners

- The European Union, its individual member states, and the United States should advance the recommendations contained in this report in multilateral forums, including at the Human Rights Council, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, and the Council of Europe, and in their bilateral dialogues with the Russian government, and should react publicly to attacks against human rights defenders and media professionals in the North Caucasus.

To the Council of Europe

- The Parliamentary Assembly should include the crackdown on free expression as well as the use of collective punishment and public humiliation practices in the agenda of its ongoing monitoring and reporting on the North Caucasus, with a view to holding, as soon as possible, a public debate on the situation.

Methodology

This report is based on 43 interviews with victims of abuses, their family members, witnesses of abuses, human rights lawyers, and representatives of independent Russian and international organizations. Most interviewees from Chechnya asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals against themselves or members of their families. In the interest of interviewees’ security Human Rights Watch chose not to specify locations or modes of interviews. Communication with interviewees was conducted either in person, by telephone or Skype, or with the use of internet-based messaging applications. Each interviewee was made aware of the purpose of the interview and agreed to speak on a voluntary basis. Human Rights Watch spoke to all interviewees separately and in private. Human Rights Watch did not provide any financial incentives to interviewees. All the interviews, except those with English-speaking foreign journalists, were conducted in Russian.

Human Right Watch chose not to interview some of the victims and witnesses to avoid reprisals against them and instead analyzed cases based on information from secondary sources, publicly available video materials, and other media publications.

Human Rights Watch also carried out extensive desk research, which included in-depth monitoring of mass media and social networks, analysis of video, photo, and audio materials and, where possible, analysis of legal and medical documents.

Human Rights Watch chose not to carry out field research in Chechnya for this report in order to avoid subjecting interviewees to the high risk of reprisals by the authorities for speaking with us.

I. Background

Ramzan Kadyrov’s Rise to Power

In the 1990s two wars over Chechnya’s status in the Russian Federation devastated the republic. In the early 2000s, after Russia’s large-scale military operations brought Chechnya back under Russian federal rule, the federal government gradually began to hand responsibility for governing the republic and carrying out counter-insurgency operations to pro-Kremlin Chechen leaders. This process was completed by 2004.

Seeking a figure who could gain the trust of important strata within Chechen society, the Kremlin chose Akhmat Kadyrov, the former mufti, or leading religious authority, of Chechnya, who then became president of Chechnya in October 2003 elections organized by the Kremlin.[1]The federal government aimed to place most responsibility for law and order and counter-insurgency operations on Chechen security structures. An important factor in this process was Akhmat Kadyrov’s personal security service, known as the Presidential Security Service, which was headed by his son, Ramzan, and initially consisted mainly of Kadyrov’s relatives and co-villagers. The Presidential Security Service (known by its Russian initials, SB), informally referred to as “Kadyrovtsy,” soon became the most important indigenous force in Chechnya.[2] The SB’s units were legalized in 2004 as Interior Ministry units, which made it easier to finance them and provide them with arms.[3]

In May 2004 a bomb attack killed Akhmat Kadyrov and Russian authorities held a presidential election to find his replacement. Twenty-seven-year-old Ramzan inherited his father’s influence but could not yet run for president as the Chechen constitution establishes 30 as the minimum age for presidential candidates.

Alu Alkhanov, a candidate chosen by the Kremlin, was elected president, and Ramzan Kadyrov was appointed first vice-prime minister in charge of security.[4]

Kadyrov soon began to muscle out those who were loyal to Alkhanov and to intimidate and punish those who refused to answer to him in an effort to extend his power and control.[5] In 2005 and into early 2006, he gained direct influence over local law enforcement agencies.[6] In spring 2006, he became prime minister ofChechnya. In February 2007 his ascent to power was completed through Alu Alkhanov’s apparently forced resignation as president. Taking the place of Alkhanov, Ramzan Kadyrov was sworn in as president of the Chechen Republic in April 2007, following his nomination to the post by President Vladimir Putin.[7] By 2008, Kadyrov firmly established himself as the only real power figure in Chechnya.[8]

Kadyrov’s War on Opponents

Lawless Counter-insurgency Tactics

For the past decade, there have been persistent, credible allegations that while aiming to root out and destroy an aggressive Islamist insurgency in the region, law enforcement and security agencies under Kadyrov’s control have been involved in abductions, enforced disappearances, torture, extrajudicial executions, and collective punishment. The main targets have been alleged insurgents, their relatives, and suspected collaborators.[9]

Kadyrov also largely equates local Salafi Muslims with insurgents or their collaborators. Calling them Wahhabis, a term widely employed with pejorative connotations to designate dissident Islamist movements and militants inspired by radical Islam, he has been publicly asserting that they have no place in Chechnya. Kadyrov has specifically instructed police and local communities to closely monitor how people pray and dress and to punish those who stray from the Sufi Islam, traditional for the region. In recent years, police raids against Salafis–or suspected ones–have become widespread. According to Memorial Human Rights Center (Memorial), a leading Russian rights group that has worked on the North Caucasus since the early 1990s, in the last three months of 2015 alone, local law enforcement and security agencies detained several hundred men in the course of these raids. The detentions however are not officially registered, and the detainees’ families are not informed about the detainees’ whereabouts or well-being. The detentions typically last from one to several days, but despite their unlawful nature, when detainees are released they do not file complaints or like to discuss what happened to them due to acute fear of reprisals.[10]

Autocracy Under Kadyrov

Numerous experts on the North Caucasus describe Kadyrov’s orders as being, in practice, the only law in the republic. They label Kadyrov’s rule over Chechnya as a “personality cult regime.”[11] In a recent report Memorial describes contemporary Chechnya as a “totalitarian state within a state,” featuring Kadyrov’s interference in virtually all aspects of social life, including politics, religion, academic discourse, and family matters.[12]

The cult created around Kadyrov and his family consolidates his full control over the republic. The main engine of this cult is Grozny TV, the state television and radio broadcast company.[13] Most of its news and “current affairs” programs are linked to Kadyrov, and it often broadcasts segments in which Kadyrov is shown giving orders and chastising people for their errors, including senior local officials. Kadyrov also actively uses social media to set his public agenda, demand obedience, designate and vilify enemies, and basically dictate the law. His Instagram account, which he launched in February 2013, gained a million subscribers by spring 2015. He also has accounts on Facebook, Twitter, and VKontakte, and according to Chechnya’s Ministry for Press and Information, his total number of subscribers on social media is over two million.[14]

Testing the Kremlin’s Tolerance

Ramzan Kadyrov frequently and zealously professes his loyalty to the Kremlin and to President Vladimir Putin personally. However, Kadyrov’s insistence on having a free rein in Chechnya has apparently begun to test the Kremlin’s patience. Until recently it appeared that Kadyrov enjoyed carte blanche to run Chechnya as his own personal fiefdom. However, starting in late 2014 the Kremlin, including Putin himself, began to respond to some of Kadyrov’s more outrageous actions with words that, though seemingly mild, were unmistakably rebukes.

On December 18, 2014, following Kadyrov’s public pledge to destroy houses of insurgents’ families and several highly publicized episodes of house burnings that followed, President Putin issued a mild rebuke saying that no one, including the head of Chechnya, has the right to impose extra-judicial punishment.[15] The significance of that seemingly gentle reprimand cannot be underestimated, as this was the very first time the Kremlin criticized Kadyrov publicly. However, the reprimand did not stop punitive house-burnings in Chechnya.

Ten days later, Kadyrov gave a dramatic speech in Grozny’s soccer stadium, in front of thousands of armed members of his security forces. “We’re telling the entire world that we are the combat infantry of Vladimir Putin,” he said. Several analysts assessed this flamboyant display of loyalty as Kadyrov flexing his muscles, as if to caution the Kremlin that withdrawing political or financial support could cost dearly.[16] Notably, less than four months later, in response to a special operation in Chechnya by federal security forces, Kadyrov ordered his law enforcement officers to “shoot to kill” if they encountered Russian federal law enforcement or security personnel from outside Chechnya who come to the republic to carry out operations without his consent.[17]

In February 27, 2015, Boris Nemtsov, a leading Russian political opposition figure and a staunch critic of Ramzan Kadyrov, was assassinated in central Moscow. The investigation quickly identified seven suspects, four of whom were either active or former members of Chechen law enforcement and security agencies; the others were either also from Chechnya or of Chechen origin. The authorities arrested five of the suspects, however they have been unable to arrest or even question a key suspect, Ruslan Geremeev, who at the time of Nemtsov’s murder served as deputy commander of a law enforcement battalion in Chechnya that is under Kadyrov’s control. According to numerous media reports, Geremeev is in Chechnya. While denying any involvement with Nemtsov’s killing, Kadyrov spoke of the suspects fondly, said Geremеev had no other choice than to go into hiding, and hinted that he had been framed. Investigative authorities eventually designated Geremеev’s personal driver, Ruslan Mukhudinov, who had somehow “disappeared” without a trace soon after the murder, as the crime’s organizer.[18] At this writing, the case against the arrested suspects has moved to trial.[19]

Although Kadyrov has for years sharply criticized, often in aggressive tones, Russia’s political opposition, investigative journalists, and human rights defenders, in 2016 these comments have become more menacing. In January 2016, when speaking to the press in Grozny, Kadyrov attacked Russia’s political opposition, accusing its members of anti-Russian “sabotage” and calling them “enemies of the people and traitors.”[20] A member of the local municipal council from Krasnoyarsk, Konstantin Senchenko, posted an emotional retort to his Facebook account: “Ramzan, you are the shame of Russia. You discredited anything that could possibly be discredited.”[21] The next day, a short video of Senchenko apologizing for his “rushed” and “emotional” statement was published on Kadyrov’s Instagram account, along with Kadyrov’s comment, “Apology accepted.” Notably, in the video Senchenko makes it clear that his decision to apologize was triggered by a visit from “representatives of the Chechen people” who apparently made him realize his mistake.[22]

In the same month, the Chechen authorities organized a mass pro-Kadyrov rally under the slogan “Our strength is in unity.” People employed in the public sector were required to attend the rally under the threat of losing their jobs and to bring one unemployed relative each. Also, college students and schoolchildren attended the rally in an organized way.[23] Local officials who spoke at the event said that leading figures of Russia’s political opposition were engaged in subversive activities and called out the names of some of them, describing them as “paid puppets” of the West and “national traitors.”[24] When commenting on the rally, Kadyrov repeatedly used the word “enemies” in relation to members of the opposition and announced a “war in every sense of the word” against them.[25]

Also in January, Magomed Daudov, the head of Chechnya’s parliament, posted to Instagram a photograph of Kadyrov with a fierce Caucasian sheepdog, claiming that the dog’s “fangs are itching” for opposition activists, journalists, and human rights defenders and providing disparaging descriptions of some of those the Chechen leadership apparently thought particularly irritating.[26]

On January 20, 2016 when commenting on the Chechen leadership’s campaign against Russia’s political opposition, Putin’s press secretary urged journalists “not to blow things out of proportion.”[27]

However, Kadyrov continued to test the boundaries of the Kremlin’s patience. On February 1, Kadyrov published a video on his Instagram featuring Mikhail Kasyanov, one of Russia’s most prominent Russian opposition politicians, in a gunman’s crosshairs, accompanied by the caption, “Kasyanov came to Strasbourg to get money for the Russian opposition.”[28] The video, which appeared shortly after Kasyanov’s visit to the January 2016 session of the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly, triggered a wave of outrage in Europe and was widely covered in the Western and Russian media. Towards the end of the same day, it was removed from Kadyrov’s account, allegedly by Instagram’s administration.[29]

In response to numerous press inquiries, Putin’s press secretary said that the Kremlin did not follow Instagram in general or Kadyrov’s account in particular but promised to look into the issue.[30]

The Lead-up to Kadyrov’s Interim Endorsement by the Kremlin

Kadyrov’s term in office as the Kremlin-appointed head of Chechnya was set to expire on April 5, 2016. By that time, elections for regional heads were reinstated across Russia, including Chechnya.[31] With regional elections scheduled to take place on September 18, 2016, along with the nationwide parliamentary vote, Kadyrov needed Putin to extend his mandate until then and to signal that he would welcome his participation in the election for the head of Chechnya. However, on February 24, Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s press secretary, implied that the president was still deliberating whether Kadyrov’s mandate would be extended. The decision, Peskov said guardedly, “will be made at the end of his term of office.”[32] Meanwhile, as the Kremlin kept its distance, Kadyrov intensified the crackdown on his critics in and outside Chechnya, including journalists, human rights defenders, local residents active on social media, and even active members of Chechen diaspora in Europe. By doing so, Kadyrov may have been trying to cut down on the flow of negative information from the region that could influence the decision-making processes in the Kremlin and undercut the Kremlin’s support for Kadyrov.[33]

On February 27, Kadyrov told the press that it was time for him to step down from his post. His statement immediately triggered a flood of pleas for him to stay on from loyal, whether genuine or terrified into loyalty, residents of Chechnya.[34] A campaign under the hashtag #Рамзаннеуходи [#RamzanDon’tGo] was launched and went viral, with Chechen supplicants eventually joined by some Russian politicians and other prominent Russian public figures.[35]

It wasn’t until March 25, that President Putin announced Kadyrov would remain as acting head of the Chechen Republic and encouraged him to run in the September election for the head of Chechnya. However, Putin’s remarks included a note of warning: he specifically stated that Kadyrov must work on building cooperation with federal authorities and ensure Chechnya’s compliance with Russian laws. Both the delay and the warning suggest that Moscow has become apprehensive of Kadyrov, however not enough to change Chechnya’s leadership.[36]

The September election clearly has special significance for Kadyrov, as this is the first time his authority in Chechnya will be re-affirmed through direct popular vote, as opposed to appointment by the Kremlin. It is in these circumstances that the Chechen authorities have been viciously and comprehensively cracking down on outside critics and those local residents whose loyalty they deem questionable. Although on paper three other candidates are also running for the head of Chechnya, they have no political clout or wide public recognition, and effectively there is no competition for Ramzan Kadyrov.[37] Most importantly, the intense crackdown does not allow people in Chechnya to express their views freely and fosters an environment in which free and fair elections simply are not feasible.

II. Attacks on Dissenters Inside Chechnya

Since mid-2014, the global drop in oil prices, coupled with the effect of the economic sanctions imposed on Russia by the United States and European Union over Ukraine, has taking an increasing toll on the country’s economy. It has had a serious impact on Chechnya, where local elites, used to luxury, began squeezing the public, demanding greater kickbacks from businessmen and public servants alike. Towards the end of 2015, worn out by stifling extortion, some local residents began to vent their frustration not only in private conversations but also on social media, including Facebook and VKontakte, Russia’s most popular social network, as well as WhatsApp and other messaging applications.[38]

In response, the Chechen leadership launched a full blown witch hunt on local critics, punishing them ruthlessly through abductions by law enforcement officials; unlawful detention; cruel and degrading treatment; death threats; and threats and physical abuse against family members. These abuses send an unmistakable message of intimidation to others that undermines freedom of expression.

One person living in Chechnya described the fierce crackdown and the level of fear in the region as “simply unbearable”:

Now when I think back to the war, I realize that back then we were not as frightened as now. Fear of a bomb, fear of a bullet–it’s something we could live with, I can live with… But this relentless pressure, this utter humiliation–I just cannot deal with it, I’m ashamed of myself. Every day, they take away another piece of my dignity. They tick me off every day, they drill me, they make me toe the line. It’s like walking a minefield, always looking over your shoulder, waiting for danger, waiting for them to take you away.[39]

In one case documented below a man died following his enforced disappearance and torture by law enforcement officials. In another a woman and her three under aged daughters were unlawfully detained, threatened, and ill-treated by police officials in retaliation for her husband’s public remarks criticizing the authorities. The mother and the eldest daughter, age 17, were both beaten and threatened with death, with the objective of convincing them to persuade her husband to retract his comments. The mother was also subjected to a mock execution. In another five cases documented below law enforcement and security officials abducted people and subjected them to cruel and degrading treatment; four of those individuals were forcibly disappeared for periods of time ranging from one to twelve days.

Five of the people whose cases are documented in this report were forced to publicly apologize to Chechen leadership for their supposedly untruthful claims and renounce their actions and comments. Personal and family honor are of enormous value in Chechen society, and loss of face through public humiliation is viewed in highly negative terms there. Numerous local residents interviewed by the International Crisis Group (ICG) for a 2015 report said public humiliation was one of the two main root causes of the paralyzing fear in contemporary Chechen society, the second one being collective punishment. One said: “It’s not even violence that is scary… You won’t be able to live with dignity in this republic anymore. This is worse than death.”[40] Another resident of Chechnya told Human Rights Watch, “I cannot think of a worse fate than being put in front of a camera, like all those unfortunate people, to grovel before the authorities in an act of contrition, beating your breast, calling yourself a crook and a liar.”[41]

The cases of abuse against local critics documented below are possibly only the tip of the iceberg. Human Rights Watch is aware of other, similar cases but could not include them in this report because victims or their family members specifically requested us not to publish their stories or because we could not obtain video materials and other evidence to confirm their accounts. There is also little doubt that some abuses against local residents in Chechnya may never come to the attention of human rights monitors or journalists because the climate of fear in the region is overwhelming and local residents have been largely intimidated into silence.

Khizir Ezhiev (forcibly disappeared, tortured, killed)

On December 19, 2015, unidentified gunmen abducted Khizir Ezhiev, a senior lecturer in Economics at the Grozny State Oil Technical University. His broken body was found on January 1, 2016 some distance outside Grozny.

At around 6 p.m. on December 19, four gunmen in civilian clothes approached Ezhiev, 35, at the service station where he was fixing his car, put him in their vehicle and drove away. His relatives later found out that they took Ezhiev to a police precinct in Grozny.[42] On December 28, Kheda Saratova, a member of Chechnya’s human rights council, which reports directly to Ramzan Kadyrov, wrote on Facebook that Ezhiev’s wife chose not to file a missing person report with the authorities out of fear that it could create problems for her husband, and expressed hope Ezhiev would soon return home. Saratova also wrote that a police officer apparently told Ezhiev’s relatives that Ezhiev had been detained but then escaped from the police.[43]

On New Year’s day, Ezhiev’s dead body was discovered in a forest near the village of Roshni-Chu, approximately 40 kilometers from Grozny.[44] A forensic report stated he allegedly died from internal bleeding after “falling off a cliff,” with one of his six broken ribs piercing a lung.[45] No further investigation has been carried out into his death.

A close acquaintance of Ezhiev’s told Human Rights Watch that Ezhiev had participated in a closed group on VKontakte that discussed the situation in the republic and expressed critical views of the Chechen leadership’s policies. The acquaintance said that on December 19 Chechen police detained several other members of the group. Not long before their detention, the group’s members apparently made derogatory comments about Kadyrov’s pilgrimage to Mecca, and Ezhiev wrote, “apparently, all sorts are welcome there these days.” Ezhiev’s relatives quickly established, through personal contacts, at which police station in Grozny Ezhiev was being held. Their source told them he was in “bad shape” and could barely move after a beating. The relatives hoped to get him released in exchange for money but a police official told them a few days later that Ezhiev had “escaped.”[46]

“The other young men were eventually released. But it seems that Khizir died from the beating and they [police authorities] were trying to cover it up,” Ezhiev’s acquaintance said.

There is no official record of Ezhiev’s detention. He is survived by a wife and four small children. The family has not pressed for investigation into his death.[47]

Khusein Betelgeriev (enforced disappearance and torture)

On the evening of March 31, 2016 two men who said they were from Chechen law enforcement forcibly disappeared Khusein Betelgeriev, a middle-aged Chechen poet, songwriter, and performer. They drove up to the Betelgeriev’s home in Kalinina village, a suburb of Grozny, in a black VAZ-2109 vehicle, forcibly entered the house, ordered Betelgeriev to follow them, and refused to tell his wife where they were taking him. When his relatives tried calling Betelgeriev on his mobile phone 15 minutes later, nobody answered. On April 2, still having no information regarding Betelgeriev’s fate and whereabouts, his family members filed a missing person report with police in Grozny.[48] His disappearance was widely reported in social media.[49] He returned home 12 days later, beaten.

Independent experts and people close to Betelgeriev tied his abduction to his pro-Chechen separatist views. On the day of his enforced disappearance, Betelgeriev had posted, in a closed Facebook discussion group called “History of the Chechen Republic,” comments praising the Chechen separatist movement.

On April 3, Anastasia Kirilenko, a freelance journalist who follows Chechnya closely, posted to her Facebook page a selection of these comments. She wrote, “on the morning [of March 31] he had written about Ichkeria [independent Chechnya] being immortal and in the evening [of the same day], he was abducted.”[50] Ekaterina Sokirianskaia of the International Crisis Group also connected Betelgeriev’s disappearance to the fact that he did not hide his separatist views and “sang of freedom and dreamed of independent Chechnya.”[51] Betelgeriev’s spouse told Caucasian Knot, an independent media portal covering current developments in the Caucasus, that his disappearance could be related to his Facebook activity, which might have displeased the Chechen authorities.[52] Furthermore, a friend of Betelgeriev told Human Rights Watch that local authorities were frustrated with his reluctance to take part in pro-Kadyrov public activities.[53]

On April 4, Chechnya’s chief prosecutor ordered the local investigation authorities to prioritize the case, and the Investigation Committee for the Chechen Republic promptly stated on its website that it was looking into reports of Betelgeriev’s abduction.[54]

On April 11, Kheda Saratova, a member of Chechnya’s human rights council, told the press that Betelgeriev had returned home safely. She claimed however, that she had no information as to where Betelgeriev had been for the previous 11 days and could not comment on the circumstances of his return.[55] One of Betelgeriev’s acquaintances confirmed to Human Rights Watch that Betelgeriev had “returned home,” that his captors had “beaten him to pulp,” and as a result he had broken bones and the state of his health was “devastating.” The acquaintance declined to provide any information about where and by whom Betelgeriev had been held. The source also flagged that Betelgeriev’s family did not want to be contacted by any journalists or human rights organizations, citing profound fear.[56]

Igor Kalyapin, the head of the Joint Mobile Group of Human Rights Defenders in Chechnya, told Human Rights Watch that the group approached Betelgeriev’s family offering to send a private ambulance for him and organize quality medical assistance for him outside of Chechnya. However, the family refused and asked Kalyapin not to contact them again.[57] These details suggest that Betelgeriev was released from captivity on condition that he maintains complete silence about what had happened to him, a common practice in such cases.

A member of the Russian Union of Writers, Khusein Betelgeriev was also a senior faculty member at the Chechen State University, until his sudden dismissal in 2015. An acquaintance of Betelgeriev’s told Human Rights Watch that he had lost his job at the university because of his separatist views, his lack of obsequiousness to the authorities, and his reluctance to support Ramzan Kadyrov publicly.[58]

Taita Yunusova (arbitrary detention)

On October 10, 2015, between 3 and 4 a.m., unidentified men took Taita Yunusova, a women’s rights activist, from a relative’s house near Grozny. Around that time, a friend received a text message from her, which said, “That’s it, I’m done for!” and that was the last known communication anyone had from her until about 20 hours later.[59]

Taita Yunusova, 49, the leader of a local activist group Live Thread, is one of several women rights activists featured in Grozny Blues, a documentary by European filmmakers about the legacy of the protracted armed conflict in Chechnya. Since April 2015, the film had been screened at several festivals in Europe and South Korea, and at the time of Yunusova’s apparent detention it was about to be screened at Artdocfest Film Festival in Moscow and St. Petersburg.[60]

On October 7, a clip from the film, which showed Yunusova and several other women activists, appeared on YouTube. Though the women did not explicitly criticize the Chechen leadership on camera, internet users from Chechen diaspora communities made online comments about Chechen women supposedly mocking Kadyrov. One of the women was unofficially detained by Chechen police the following day and allegedly beaten for several hours, humiliated and threatened with execution, and another immediately left Chechnya.[61]

On October 10, the producers of Grozny Blues sent a letter to Ramzan Kadyrov expressing alarm about Yunusova’s apparent disappearance. They also posted the letter to Kadyrov’s Instagram page, from which it was deleted several hours later.[62] The chair of Artdocfest Festival, Vitaly Mansky, posted an open letter to Kadyrov on Facebook, urging Kadyrov to “ensure the security of Taita Yunusova.”[63] Several prominent artists publicized the case, alleging a connection between Yunusova’s apparent abduction and her role in the documentary, and it immediately generated media attention.[64]

At around 11 p.m. on the same day, a colleague of Yunusova’s called Caucasian Knot and said, “They have just let her go, and she is OK. She is alive, and that’s the most important thing.”[65] On October 11, Kheda Saratova from Chechnya’s human rights council, wrote on Facebook that she visited Yunusova at home in the morning and Yunusova “is all right, there was no abduction and there especially was no violence.”[66]

Later the same day, Yunusova publicly denied that she had been detained. She gave a video interview claiming that she was “shocked” to “find out about own abduction from the media,” and that the stories about her supposed abduction “discredit [her] in the eyes of the public and the [Chechen] leadership.” She said media reports about her disappearance were a “provocation,” vehemently denied allegations that she had been abducted, and said that she spent the day in an oncology ward taking care of a sick relative.[67]

Rizvan Ibraghimov and Abubakar Didiev (forcibly disappeared, publicly humiliated)

Rizvan Ibraghimov and Abubakar Didiev, two middle-aged Chechen researchers and publicists, disappeared for several days in April 2016 following on an abduction-style detention.

Ibraghimov and Didiev are known in Chechnya for their unconventional interpretations of the history of the Chechen people and of Islam, which are out of line with those promoted by the Chechen authorities.[68]

On March 28, Ibraghimov and Didiev attended a roundtable on the problems of the ethnic origins of Chechens organized by representatives of the muftiat, or chief of the local religious authority, of Chechnya.[69] According to Caucasian Knot and other sources, the purpose of the meeting was specifically to reprimand Ibraghimov for a lecture, “The True History of the Chechen People” which he had delivered at the International University al-Mustafa in Iran in February 2016, and to warn him and Didiev that their ideas were unacceptable.[70]

On the night of April 1, 2016, local law enforcement officers took both men from their respective homes. On April 4, Caucasian Knot and Novaya Gazeta reported that the men’s relatives said they knew the men’s whereabouts.[71] The media also reported that the men had been taken away by Chechen law enforcement officials who also seized their personal computers, and that their social media and Skype accounts had been hacked or forcibly taken over.[72]

Both men retuned home in the evening of April 5. Earlier that day, Ramzan Kadyrov held a meeting with Chechen academics and opinion leaders. Kadyrov wrote about the meeting on his Instagram account, commenting that Ibraghimov and Didiev had “offered apologies to the academic community and religious leadership of Chechnya” for their flawed theories and publications.[73] A video from that event, broadcast on Grozny TV, shows Ibraghimov and Didiev standing and apologizing to the meeting participants for their “mistakes.”[74] Following the event, Ibraghimov and Didiev were able to return to their families. Rizvan Ibraghimov later wrote, but later deleted, a post on his Facebook page that he had spent the days he was missing at the Oktyabrsky District Police Station in Grozny:

I, …Rizvan Ibraghimov, spent the last 4 days starting the night of April 1 to 2 in Grozny’s Oktyabrsky District Police Station. Nobody abducted me, but they held me in custody for fear of me fleeing. Today, there was a talk with the head of the Chechen Republic Ramzan Kadyrov, after which I and Abubakar Didiev were freed. No coercive measures were used against us. More details will be given tomorrow. I express huge gratitude to those who worried about us.[75]

According to media reports, Didiev left Chechnya soon afterwards.[76] In July, a court in Chechnya upheld a motion by the prosecutor’s office to ban as “extremist” several of Ibraghimov’s books.”[77]

Adam Dikaev (humiliating and degrading punishment)

Adam Dikaev was publicly humiliated for his criticism of Kadyrov in social media. On December 11, 2015, Dikaev made unflattering comments about a video that appeared on Kadyrov’s Instagram account on December 2 featuring Kadyrov exercising, in a t-shirt with Putin’s photo, to a popular Russian song “My best friend is President Putin.”[78] Dikaev’s comment implied that Kadyrov had dishonored the memory of the Chechen war by praising Putin, who launched the war in Chechnya in 1999.[79]

On December 20, a new video appeared on Facebook and other social media, which featured Adam Dikaev walking on a treadmill, without his pants, wearing just a hoodie and underwear.[80] On the video, Dikaev renounced his actions and abased himself:

I am Adam Dikaev from Avtury village. Thinking that no one can find me, I wrote in the Instagram what I should not have written. They found me and took my pants down. I realized I am nobody. From now on, Putin is my father, grandfather, and tsar. You can find this video on my Instagram account at adam chechenskiy.[81]

Human Rights Watch has no information about the circumstances under which the video of Dikaev was made, however forcing Dikaev to appear publicly in underwear was a form of humiliation clearly intended to deprive him of all public dignity.[82] The manner in which Dikaev was ill-treated not only punished him but sent a powerful warning to other potential critics of Kadyrov to keep quiet or risk being publicly stripped of their dignity too.

Aishat Inaeva (public humiliation)

Aishat Inaeva, a social worker, was subjected to public humiliation in December 2015 for having openly appealed to Ramzan Kadyrov about Chechen officials’ alleged extortion practices.

In the first half of December, Inaeva disseminated through the social media platform WhatsApp an audio appeal to Ramzan Kadyrov, complaining about what she described as the practice by local officials of collecting debts and advance payments for gas and electricity bills, and how this practice was pushing ordinary people below the poverty line.[83] She noted the impact of these actions on public servants, who face forced deductions from their wages and threats of dismissal for refusing to pay.[84] Her recording also alleged that Chechen authorities live in luxury and spend staggering amounts of money on entertainment, while ordinary people struggle just to get by, and suggested that Kadyrov had to be aware of how those practices affected Chechnya’s population. “People are dying of hunger but you don’t care,” she said.[85] Her appeal went viral among Chechen users of WhatsApp.

On December 18, Grozny TV aired a story about Kadyrov meeting with Inaeva and her husband. The segment, which is 16 minutes long, shows Kadyrov and other local officials chastising her as she renounced and apologized for her alleged “lies.”

I apologize… No one asked me [to give extra payments]... You help [the poor]… I was confused and not able to understand [what I said]… I was mistaken. I acknowledge that. I do not know how and why I did that.[86]

In the video, Inaeva appeared extremely frightened and subdued, spoke quietly, and kept her head bowed, staring at the floor.[87] Kadyrov also questioned Inaeva’s husband, who repeatedly said no one deprived him of salary, apologized for his wife and for “allowing her to spread all those lies.”[88]

Ramazan Dzhalaldinov (threats, house-burning, abuse of family-members, public humiliation)

Ramazan Dzhalaldinov, 56, is an ethnic Avar from Kenkhi, a small village not far from Chechnya’s border with Dagestan populated mainly by Avars. On April 14, 2016 Dzhalaldinov published a video message for the nationally televised, live call-in show that Russian President Vladimir Putin holds annually.[89] In the video, Dzhalaldinov complained, among other things, that the village was in ruins as a result of the Chechen wars and seasonal landslides. He pointed to the scenery of his village, with its ramshackle houses and washed-out roads and cited the 2003 government regulation on compensation to civilians who lost housing and property due to military operations in Chechnya.[90]

Dzhalaldinov argued that local Chechen officials are mired in corruption and embezzle the funds allocated for reconstruction. Dzhalaldinov and dozens of his co-villagers had previously sent multiple complaints on the issue to Chechnya’s leadership and law enforcement authorities, but the complaints yielded no tangible result.[91]

The video was not broadcast during the call-in show, but after Dzhalaldinov posted it to his VKontakte account it was swiftly picked up by the Caucasian Knot media portal. Dzhalaldinov fled Kenkhi to neighboring Dagestan, fearing for his safety.[92]

Several days after the video’s publication, Islam Kadyrov, chair of the Ramzan Kadyrov’s administration and his close relative, traveled to the Sharoi district, where Kenkhi is located, rounded up a group of local public servants and spoke to them on camera. They said that Dzhalaldinov’s claims had nothing to do with reality and that he was “unstable” and a “liar.” The story was broadcast on Grozny TV on April 18.[93] At around that time, Dzhalaldinov’s cousins contacted him from Kenkhi warning him that a group of village officials paid them a visit, saying that the only way to “save” Dzhalaldinov from harm was to help spread the story about him allegedly being mentally unstable.[94]

On May 6, Ramzan Kadyrov and his entourage paid a visit to Kenkhi and spoke to local residents who, again, said on camera that they had no complaints and their co-villager was “unstable,” a bully, and a liar, infamous for making innumerable “false” and “fruitless” complaints.[95] The broadcast story included no comments from those who attempted to support Dzhalaldinov and uphold his allegations and were harassed and threatened by officials in response.[96]

From mid-April through the early May, police officials visited Dzhalaldinov’s home several times, putting pressure on his family members to reveal his whereabouts and insisting that he was wanted for interrogation.[97]

On May 13, just after midnight, a dozen gunmen in masks and camouflaged uniforms forced their way into Dzhalaldinov’s house. Dzhalaldinov’s wife, Nazirat Nabieva, and their three daughters, 17-year-old Muslimat, 12-year-old Sabirat, and 10-year-old Tabarak were at home. (Nazirat’s adult sons had fled Kenkhi soon after their father for security reasons.) The gunmen ordered Nabieva and her daughters to get into one of their vehicles with their passports and the children’s birth certificates. When Muslimat picked up her phone to call their relatives for help, one of gunmen yelled at her and snatched the phone away. Another gunman pushed Nabieva to the floor with his automatic rifle when she begged them to leave the younger girls behind. The other gunmen dragged the crying children out of bed and, without letting Nabieva or her daughters get dressed, put them into the vehicle and drove to the Sharoi regional police department.[98]

At the police department, local police officials and their chief threatened and beat both Nabieva and her eldest daughter, demanding that they reveal the whereabouts of Dzhalaldinov and his sons and demanding that they call Dzhalaldinov a liar. A police official held Nabieva while a more senior official punched her on her back, on her ribcage, and in her kidneys and kicked her with his booted feet. He also hit her with the butt of his gun, put the gun barrel to her head and neck, threatened to kill her, and fired the gun three or four times above her head. All the while, he kept saying that he was punishing her for all the trouble caused by her husband. He also forced her to say that the allegations in Dzhalaldinov’s video were false, filming her statement with his cell phone.[99]

The same senior police official choked Muslimat and threatened to kill her, forcing the girl to give up the phone number of one of her brothers, which she originally claimed she did not know. He also hit her on the neck and the back of her legs, saying that her father was a bandit and if she wanted him and her brothers alive, she needed to persuade her father to retract all of his complaints.[100]

After more than an hour, police officials put Nabieva and her daughters back into the same vehicle, drove them directly to Chechnya’s administrative border with Dagestan and, without returning their identification documents, told them to go to Dagestan and never return to Chechnya. While Nabieva and the girls were being held at the station, unidentified men torched their house in Kenkhi and ordered the neighbors to stay silent.[101] Later that day, Ramzan Kadyrov said that Dzhalaldinov intentionally “took his family out of Chechnya and simulated an arson attack.”[102] A few days later, with the help of human rights lawyers, Dzhalaldinov filed complaints with the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the prosecutor’s office regarding the ill-treatment of his wife and daughters and house-burning by local police officials.[103] He and his family members also spoke to the media.

On May 15, according to media reports, unknown men tried to kidnap Dzhalaldinov in front of a mosque in the Tsumadinsky district of Dagestan, but the men who gathered in the mosque protected him.[104]

On May 21, Grozny TV showed a story about a petition to Putin from Kenkhi residents. Allegedly 455 men signed the petition claiming that “enemies of the state” and “pseudo-patriots, who call themselves human rights defenders,” were using Dzhalaldinov to wage an “information war against Russia” and incite “national discord among ethnic groups” in Chechnya .[105]

On May 30, Dzhalaldinov appeared on Grozny TV, giving an apologetic speech:

Last Friday, I went to the mosque and with the help of the imam started looking for a way to approach Kadyrov. I asked Khasmagomed [Abubakarov–a respected elder in Chechnya] to apologize to Ramzan [Kadyrov] on my behalf. I apologize. I made a mistake. I ask other people not to repeat my mistake. The things those provocateurs have written [about Dzhalaldinov’s video message] are 99 percent lies. I never criticized Ramzan [Kadyrov]. No one persecuted me. I walked in parks, visited museums, and made photos freely in Makhachkala [in Dagestan]. I hid from no one and never received threats. Now many will say I was threatened or coerced [to say this]. I make this speech voluntarily… Ramzan [Kadyrov] rebuilt this [Kenkhi] village.[106]

On the same day, Kadyrov posted on Instagram that he accepted Dzhalaldinov’s apology. He noted that “some abnormal forces” were trying to use Dzhalaldinov “to achieve their filthy, harmful objectives,” subjected him to a “psychological and information attack,” and talked him into fleeing Chechnya, citing false security threats–but fortunately, Dzhalaldinov “found the strength and wisdom” to realize his mistake and to “publicly admit he was wrong.”[107]

Dzhalaldinov immediately returned to Kenkhi with his family. Approximately two weeks later, he withdrew his complaints about alleged abuses by police officials. Since then and until the time of this writing, he and his family members have been safe and even received some money from Chechen officials to rebuild their house.[108]

III. Attacks on Human Rights Defenders

The murder of a leading Chechen human rights defender, Natalia Estemirova, in July 2009 immensely contributed to the climate of fear in the region, making it nearly impossible for local human rights defenders to take up cases of abuses by law enforcement and security agencies under Kadyrov’s control without unacceptable risks to their lives and their families.[109] Under those circumstances, Igor Kalyapin, the head of what is now called the Committee for Prevention of Torture, a Nizhny Novgorod-based group, organized the Joint Mobile Group of Human Rights Defenders in Chechnya (JMG). This initiative involves sending human rights lawyers and activists from a range of prominent human rights organizations in other Russian regions to work in Chechnya on a rotating basis. They provide legal aid and other forms of assistance to victims of human rights violations in Chechnya.

The JMG has been operating since November 2009, with Kalyapin and his Committee in the lead, focusing on bringing to justice perpetrators of enforced disappearances, torture, and extrajudicial executions in Chechnya.[110] Until December 2014, the JMG was able to maintain an office in Grozny and work throughout Chechnya, despite the increasingly hostile climate and several security incidents.[111] However, at the end of 2014, the Chechen leadership apparently became determined to push the JMG out of Chechnya, leaving victims of abuses by law enforcement without any means of pursuing justice. As of December 2014, the JMG’s office was attacked and ransacked or burned three times; its activists have been attacked repeatedly apparently by Chechen authorities’ proxies; and a massive smear campaign against the group has been raging in the Chechen media. Since early 2016, the JMG no longer has its team based in Chechnya for security reasons.

The intense crackdown on JMG was apparently triggered by a complaint Kalyapin filed with Russia’s law enforcement authorities against Kadyrov. But the Chechen authorities’ hostility towards the group had been building since JMG’s launch as the only independent group in the region taking up cases of abuse by local law enforcement and security officials.

Chronicle of the Crackdown against the JMG and its Leadership

On December 5, 2014, armed Islamist insurgents carried out an attack in Grozny, killing 14 and injuring 36 law enforcement officers.[112] The deceased included Ramzan Kadyrov’s 22-year-old cousin, Umar Kadyrov. In retaliation for the attack, Kadyrov promised to “raze to the ground” houses of insurgents’ family members and expel the families from Chechnya “with no right to return.” Within days, at least nine houses in five different towns were set on fire by unknown men and burnt down.[113]

On December 8, Igor Kalyapin petitioned Russia’s prosecutor general and the chief of the investigation authorities to examine Kadyrov’s statement for signs of abuse of official powers. Kalyapin argued that by asserting collective responsibility and referring to specific forms of punishment for relatives of insurgents, the head of Chechnya gave a green light to targeted criminal acts against civilians.[114]

On December 10, the Chechen leadership unleashed a smear campaign against Kalyapin and the JMG, starting with Kadyrov accusing Kalyapin of “defending bandits” and laundering money for insurgents.[115] The same day, the speaker of the Chechen parliament accused Kalyapin of trying to make a name for himself by maligning Kadyrov.[116] On December 11, unidentified men attacked Kalyapin and pelted him with eggs as he spoke at a news conference in Moscow about collective punishment in Chechnya.[117] The next day, Chechen TV aired the program “Tochka Oporu [Support Point]” where the guest speakers vilified Kalyapin and his colleagues for supposedly “profiting from [the Chechen] war” and using human suffering to get grants from Western donors.[118]

On December 13, the Chechen authorities sponsored a mass rally in Grozny “against terrorists’ supporters,” supposedly at the initiative of relatives of killed policemen.[119] Demonstrators held banners “Kalyapin, go home $$” and “Ramzan Kadyrov, protect us from the ‘Kalyapins’!”[120] Speakers called human rights defenders “fascists” and asked the officials to get rid of “pro-Western” “supporters of terrorism.”[121]

On the same day, the JMG team noticed they were being followed by armed, masked men in a car believed to belong to Chechen law enforcement officials. In the evening, their office in Grozny caught fire in an apparent arson attack and was destroyed. The next day, police entered the apartment rented by JMG in Grozny for the team members and, without providing any explanation or a search warrant to the two JMG activists present, ransacked the apartment, confiscated mobile phones, several cameras, laptop computers, and other electronic equipment. They also conducted body searches of the activists, searched their car, and held the activists for several hours before releasing them without charge. Though local law enforcement authorities launched a perfunctory investigation into the alleged arson attack, it was soon suspended without result.[122]

On December 17, Kadyrov once again attacked JMG on Instagram:

…US State Department and its henchmen launched a new project called ‘Kalyapin & Co.’ They created a beautiful story about some mobile group of young and athletically built men from Nizhny Novgorod who struggle for human rights in Chechnya. In reality, Kalyapin and his group do not care about human rights. They care about insurgents, terrorists, and their families. Why? Because he who pays the piper calls the tune. And who pays them? The UK Embassy and other Western sources gave the Committee [Against Torture] 44534000 rubles…[123]

In January 2015, five men in dark clothing and face masks forced their way into the office of the Memorial Human Rights Center in Gudermes, Chechnya’s second largest city, and pelted the staff with eggs screaming, “This is [for supporting] Kalyapin!”[124]

In May, the Grozny Information Agency published another smear piece vilifying JMG and accusing the group of setting fire to their own office in Chechnya:

...They tried to ‘kill two birds with one stone’: acquire ‘fame’ of persecuted human rights defenders and hid all of their financial irregularities – when they launder big money of their western masters under the guise of human rights protection in Chechnya…[125]

Grozny TV also alleged that Kalyapin and JMG were “pumping out funds from western backers for imaginary human rights issues and [imaginary] work.”[126]

On June 3, 2015, an aggressive mob surrounded the building in which the JMG had its office at the time, smashing the JMG's car in the courtyard with metal crowbars, before forcing their way into the building. They broke down the door and stormed into the JMG office. Several people also climbed onto the office balcony and tried to break in through the window. Two JMG activists who were in the office escaped through a window on the other side of the building. The mob ransacked the office, then broke down the door of the apartment rented by the JMG staff on the same floor of the building and continued with the rampage.[127] Local law enforcement authorities did not intervene despite multiple attempts by JMG activists to reach them by phone. A few days later, Chechnya’s Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs said he had no desire to respond to a phone call from Kalyapin, a “representative of the security services of the US and other hostile states.”[128] Meanwhile, Kadyrov claimed that the JMG staff deliberately provoked the attack to “earn fame in international mass media and receive new American funds.”[129] At this writing, there has been no accountability for the mob attack.[130]

In October 2015, a JMG team took a crew of Austrian journalists to film destroyed houses of insurgents’ families in the Chechen village of Yandi. Unidentified men attacked the group, pelted them with eggs, and chased them away.[131]

The smear campaign against Kalyapin and the JMG continued in Chechen media in 2016, with the group and its leader being repeatedly accused of working in the interests of their alleged Western sponsors to discredit Chechen leadership and destabilize Chechnya and Russia.[132]

On March 9, as described below, a mob viciously attacked a bus with Russian and foreign journalists on a trip to Chechnya organized by the Committee for Prevention of Torture through the JMG initiative.[133] Two nights later, Chechen police broke the door of the apartment in Grozny, which the JMG was using for work after their office was ransacked in June 2015. They broke the security camera, then ransacked the place, and finally left, sealing the doors shut. Local law enforcement authorities refused JMG’s requests to open an investigation into the actions by Chechen police. At this writing, JMG no longer has teams based on the ground in Chechnya due to security concerns.[134]

Violent Attack on Igor Kalyapin in Grozny

On March 16, 2016, a mob assaulted Kalyapin in Grozny, where he had gone to look into a violent attack against a group of journalists one week before (see below).[135] At around 7 p.m. approximately 40 minutes after he got to his room at the Grozny Citi Hotel, a hotel administrator knocked on his door, accompanied by a security guard, and another man. The administratortold Kalyapin he had to leave the hotel immediately because of the “unpleasant things” Kalyapin had said about Chechnya’s leader.[136]

Kalyapin gathered his belongings and left the hotel. As soon as he got outside, a mob of men, who were clearly waiting for him, pushed Kalyapin to the ground, kicked him, pelted him with eggs, and threw flour and bright green antiseptic liquid on him. Kalyapin suffered no injuries, but by the time his assailants fled, he was covered head to toe in flour, eggs, and green antiseptic. He told Human Rights Watch:

It was a well-prepared effort. When they escorted me to the hotel lobby I wanted to leave straight away but I could not do this. A group of women, apparently hotel employees, were waiting for me downstairs. They surrounded me, not letting me move towards the exit. They were yelling something about me saying bad things about Kadyrov and how the people of Chechnya won’t tolerate it. I tried to engage with them but they would not listen to me. Their role was clearly to keep me inside while the team of assailants were gathering outside with their supplies ready. And then I was literally pushed outside and the show began.[137]

Police eventually appeared at the scene and took Kalyapin to the city police station for questioning. Kalyapin told Human Rights Watch that police took his statement and photographed all of his clothing. A federal investigator came to the police station at Kalyapin’s request, who felt he was still at risk, and they left Chechnya together.[138] On the same day, Grozny TV aired a program on Igor Kalyapin, accusing him of anti-Russian sabotage and lies for the sake of publicity. The anchor once again cited the amount of funds provided by foreign donors to the group.[139]

On March 19, following a very strong statement by the Russian Presidential Human Rights Council, President Putin’s press secretary said that the attack against Kalyapin in Grozny was “possibly a sequel” to the March 9 attack on journalists and stressed that it was “unacceptable” and “a cause for concern.”[140] The local prosecutor’s office in Grozny has ordered an investigation into the attack three times, and each time police opened a preliminary inquiry but declined to pursue a criminal case. At this writing, no one has been held accountable for the attack.[141]

IV. Attacks on and Harassment of Journalists

In recent years, journalists have been finding it increasingly difficult to work in Chechnya. One of the main obstacles many media professionals have described to Human Rights Watch is the climate of fear in the region, where on the one hand very few people dare talk to journalists, except to compliment the Chechen leadership, and on the other hand, those who do put themselves at great risk could be punished for speaking with or helping journalists. In 2016, several local journalists and activists who helped foreign and Russian independent media outlets with their Chechnya-related work had to leave the region due to well-grounded fears of reprisals. In the words of Anna Nemtsova of The Daily Beast, who has covered Chechnya since the second war broke out in 1999:

It's never been easy in Chechnya. I don't remember the time when I wasn’t worried about the security of [the people I write about] but in the last couple of years we’ve been constantly, overwhelmingly concerned about doing harm, creating problems for the people I interview. It’s been the same with other colleagues. Some of our [interviewees] and helpers have been punished by Chechen authorities for talking to foreign press–they were arbitrarily detained, threatened, humiliated. The risk for journalists working in the field has also increased dramatically. Covering crises is never risk-free, but I don’t know any other region in Russia, where the people are so terrified by state repression and where independent observers, including journalists, feel so threatened.[142]

Indeed, the situation has clearly become more dangerous not only for local residents who talk to independent press but also for journalists who persevere with Chechnya work. The cases documented below include a violent attack on a group of journalists, including foreign journalists, a death threat against a prominent Russian journalist, and a case of arbitrary detention of another well-known Russian journalist.

In March 2016, a group of masked men attacked a minibus driving a group of Russian and foreign journalists from Ingushetia to Chechnya, dragged the journalists from the bus, beat them, and set the bus on fire.[143] The attack was so shocking that it triggered an immediate, unparalleled reaction from President Putin’s press secretary, who called it “absolutely outrageous” and called on law enforcement authorities to ensure accountability for this crime.[144] However, at this writing, although an investigation into the attack was nominally opened, it has not yielded any tangible results.

Anna Nemtsova told Human Rights Watch that she and many other media workers regarded the attack and the failure to identify the attackers as a warning to independent journalists, “a strong signal that this is what’s going to happen to you if you dare to come and work in Chechnya.”[145]

Attack on Bus with Journalists

On March 9, 2016, at least 15 masked men armed with sticks and knives attacked a bus carrying eight people and their driver as the group traveled from Ingushetia to Chechnya.[146] The group which was badly beaten by the attackers included six journalists–one Norwegian, one Swede, and fourRussians–andtwo Russian human rights activists.All were injured, and five were hospitalized. The attackers set the bus on fire.[147]

The journalists and activists were on a trip organized by the Committee for Prevention of Torture through the JMG initiative. Sergei Romanov, a lawyer with the committee who was in touch with his colleagues during and after the incident, said that the group had noticed they were under surveillance by people whose identities they did not know from the beginning of the trip on March 7.[148]

Those attacked included Ivan Zhiltsov and Ekaterina Vanslova, staff members of the Committee for Prevention of Torture; Oeystein Windstad, a correspondent for Norway’s Ny Tid newspaper; Lena Maria Persson Loefgren, a Swedish state radio journalist; and four Russian journalists: Aleksandra Elagina of The New Times, Egor Skovoroda of Mediazona, and freelance journalists Anton Prusakov and Mikhail Solunin.

Romanov told Human Rights Watch that on the evening of March 9, when they were near the village of Ordzhenikidzevskaya, close to the administrative border between Ingushetia and Chechnya, three cars carrying the masked men blocked the road, forcing the bus to stop. The men dragged the passengers out of the bus, kicked them and beat them with sticks, calling them “terrorists” who would “not be allowed to work on our land.” They then poured gasoline on the bus and set it afire, destroying the journalists’ equipment and some of the victims’ identification documents. Having torched the bus, they fled.[149]

Lena Maria Persson Loefgren, who suffered multiple bruises and a deep gash on her upper leg told Human Rights Watch:

When those men attacked the bus, I dropped to the floor and tried to shield myself from glass fragments as they were breaking the windows. I thought they just aimed to frighten us… And then they broke the door, which the driver had locked, and they got in, through the driver’s seat–so I was the first person they faced as I was right behind it. They were screaming, “You are friends of terrorists!” And I look at this man wielding his stick and I try to reason with him, “I’m a Swedish journalist. I’m a 59-year-old woman, a mother, a grandmother. Will you really beat me?” And he did… It’s hard to come to terms with [it]… They beat us with their sticks, and kicked us. They pulled me out of the bus by my hair and they did the same with the young girl from the human rights group [Ekaterina Vanslova], who was on the floor next to me. They forced us face down on the ground, and they continued beating us, mostly on the legs… They were threatening to kill us while they were beating us. They were a mob.[150]

Local residents arrived at the scene, called an ambulance and the police. The ambulance took five of the victims, including the driver, to the Sunzhenskaya district central hospital in Ingushetia. Ingush law enforcement dispatched to the scene drove the others to the Sunzhenski district police station for immediate questioning. Those hospitalized gave testimony to police in the hospital the next day.[151]

The driver, Bashir Pliev, suffered particularly serious injuries–multiple rib fractures, an arm fracture, a leg fracture, and a concussion. Oeystein Windstad, who was on his very first trip to the region and does not speak Russian, sustained a concussion, multiple bruises, and stab wounds to his arms, legs, and face, a leg fracture and two broken teeth. He suggested to Human Rights Watch that he suffered so many injuries because he resisted when the assailants attempted to drag him out of the bus:

It was dark and when those cars blocked our way and the men in masks with sticks jumped out, I thought, this is it, I’m going to die. I remembered that human rights defender [Natalia Estemirova] and how she was kidnapped from Chechnya and taken to Ingushetia to be killed…[152] So, when they started to drag people out of the bus, I had no doubt it’s now my turn and they’ll just shoot us. I could hear my colleague, Lena Maria, screaming as they were dragging her by her hair, and I thought I won’t let them drag me outside, even if it only means making it more difficult for them and living 30 seconds longer… I crawled to the very back of the bus. They kept trying to drag me out, pulling on my limbs, hitting me, kicking me. They pulled off my winter jacket and then my sweater, probably thinking that this way it’ll be easier for them to push me out of the broken window… There were shards of glass everywhere… I raised my legs resisting their efforts and one of them stabbed me deep into the leg–it was either a knife or a nail, I’m not sure, but one of them had a nail attached to the top of his wooden club. They did everything to pull me out but I thought letting them meant death, a bullet in the head. And then suddenly, one of them screamed something at me–I could not understand but my colleagues later told me he screamed they’d be burning the bus and if I wanted to burn with it, whatever–and they all jumped out. I thought it was my chance to escape. I jumped out of the bus and ran… They chased me for some 100 meters and then there was a big bang and I could see the sky light up. They set the bus on fire.[153]

According to the Committee for Prevention of Torture, having examined the scene of crime and questioned the victims and witnesses, law enforcement authorities launched a criminal investigation into “hooliganism, assault, damage to property, and obstruction of journalistic work.” At this writing, the investigation into the attack is ongoing but has not yielded any tangible results.[154]

Ilya Azar, Meduza (threats, arbitrary detention)

Ilya Azar, a journalist with Meduza, an independent online media outlet registered in Latvia but targeted at Russian audiences, was detained by Chechen law enforcement officials in May 2016 in a suburb of Grozny, where he was working on a story about punitive house-burnings in Chechnya. The officials forced him to get into their vehicle, took away his phones, documents, and voice recorder, drove him to the main police precinct in Grozny and held him there for four hours. They released him but treated him in a hostile manner, making it clear to him that he could not continue with his work in Chechnya.

Azar attempted to look into the burning of the home of the family of a man who, on the morning of May 9, had attacked a security checkpoint in Alkhan-Kala, a village bordering Grozny. On that day, one man detonated explosives he was carrying at the checkpoint, killing himself and injuring six police officers. The police killed a second man who was accompanying him.[155] The men were identified as 24-year-old Ahmed Inalov and 26-year-old Shamil Dzhanaraliev, both in their twenties, from the village of Kirova about 6.5 kilometers from Alkhan-Kala.[156] Ramzan Kadyrov posted belligerent comments on his social media account about the attack and the men and announced “raids and preventive [counter-insurgency] activities.”[157]

On May 11, media reported the houses belonging to the families of Inalov and Dzhanaraliev had burned down.[158] Ilya Azar, who happened to be in Grozny on assignment for Meduza at the time, went to Kirova village to interview local residents and take pictures of the burned houses. Azar arrived there at around 1:10 p.m. and had managed only to take two photographs of the Dzhanaraliev’s destroyed house when a man who introduced himself as a deputy head of the local administration appeared and forbade him to take pictures.[159] When Azar approached a group of residents with questions about the burnt houses, an unknown man immediately volunteered to speak for the group, denied allegations of house burning, and prevented the others from answering Azar’s questions.[160]

Two police officers arrived on the scene at around 1:40 p.m. and immediately took away Azar’s passport, voice recorder, and two mobile phones, accusing him of working for the insurgents and having Syrian connections. A man in civilian clothing drove up to them a few minutes later, introduced himself as Magomed Dashaev, head of the Grozny police,[161] and ordered that Azar be taken to the Grozny police department “to check for terrorism.” He put Azar into his car and drove to Grozny. Another police official rode in the car with them.

On the way to Grozny, Dashaev kept telling Azar that he resembled the ISIS leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. He asked whether Azar had been to Syria and whether he liked ISIS. Soon after their arrival at Grozny’s main police precinct, the two police officers who had detained Azar in Kirova also arrived there.