Summary

Every year, several hundred thousand people across the United States are sued by companies they have never done business with and may never have heard of. These firms are called debt buyers and although they have never loaned anyone a penny, millions of Americans owe them money. Debt buyers purchase vast portfolios of bad debts—mostly delinquent credit cards—from lenders who have written them off as a loss. They pay just pennies on the dollar but can go after alleged debtors for the full face value of every debt plus interest at rates that routinely exceed 25 percent.

Debt buyers also rely on tax-funded state institutions—namely the court system—to secure much of their income. Leading debt buyers rank among the heaviest individual users of state court systems across the US, and various legal actions and research, including that of Human Rights Watch, have identified repeated patterns of error and lack of legal compliance in their lawsuits. These problems are often discovered long after the debt buyers have already won court judgments against alleged debtors, a situation that arises because of the inability of alleged debtors to mount an effective defense even when they are on the right side of the law. Debt buyer lawsuits typically play out before the courts with a stark inequality of arms, pitting unrepresented defendants against seasoned collections attorneys.

The amount at issue in any one debt buyer lawsuit rarely exceeds a few thousand dollars, but the stakes are often higher than they seem. Many of the defendants in these cases are poor or living at the margins of poverty and this is often the reason they fell into debt in the first place. For them, the impact of an adverse judgment can be devastating. Human Rights Watch interviewed alleged debtors in court who broke down in tears while trying to explain how the judgments debt buyers had won against them would impact their ability to pay bills and support their children.

None of this means that debt buyers and other creditors should not be able to enforce their claims in court, but it does mean that courts have clear and compelling reasons to handle debt buyer litigation with a particular degree of vigilance. This report describes how many courts do exactly the opposite, treating debt buyer lawsuits with passive credulity so that their imprimatur is reduced to little more than a rubber stamp. And in addition to smoothing the way for the corporate plaintiffs, many courts have erected formidable obstacles for unrepresented defendants who simply want to have their day in court. These courts risk complicity in damaging the rights of poor people entitled to fair administration of justice and equitable proceedings, and are putting their own integrity at risk.

The scale of the debt buying industry is hard to overstate. Leading firm Encore Capital claims that one in every five US consumers either owes it money or has owed it money in the past. While a relative handful of large firms dominate the business, there are hundreds and perhaps thousands of companies buying up delinquent debts across the US at any given point in time.

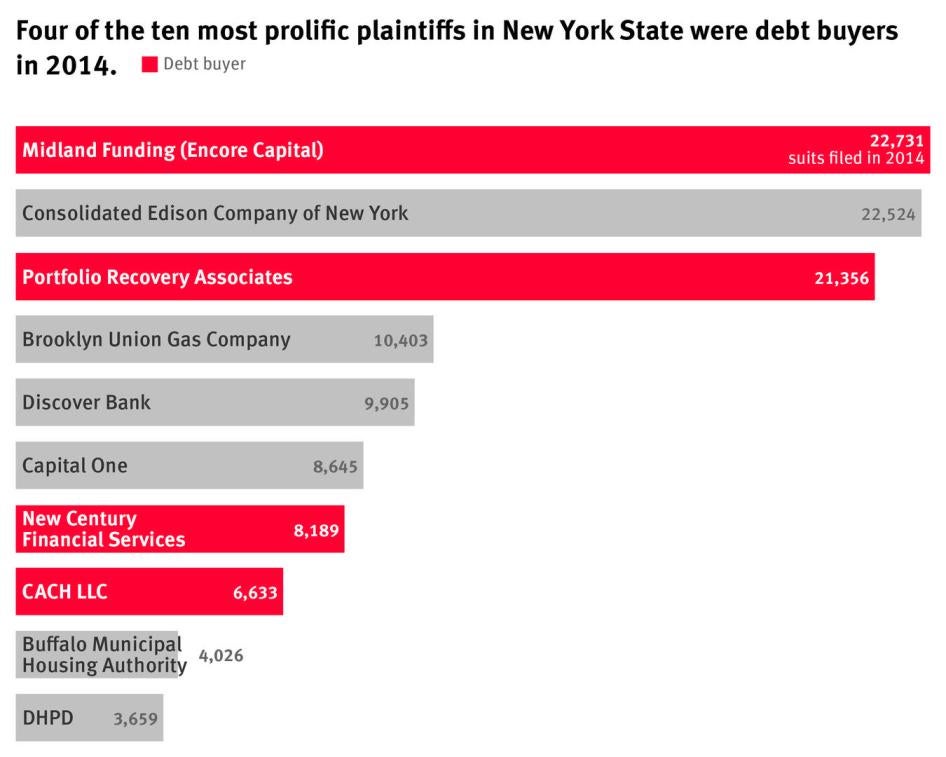

Leading debt buyers collect about half of their revenue by suing alleged debtors in court. Encore and one of its leading competitors, Portfolio Recovery Associates, collected a combined total of more than $1 billion through hundreds of thousands of lawsuits in 2014. In New York State, Encore filed more lawsuits than any other civil plaintiff that year, with Portfolio coming in third. Eight of New York’s 20 most litigious plaintiffs were debt buyers in 2014, and they accounted for 47 percent of the 142,506 cases filed by that group.

Many debt buyer lawsuits rest on a foundation of highly questionable information and evidence. Debt buyers do not always receive meaningful evidence in support of their claims when they purchase a debt, and in some cases the sellers explicitly refuse to warrant that any of the information they passed on is accurate or even that the debts are legally enforceable. Enormous accumulations of interest—often in excess of 25 percent compounded over periods of several years—are added to many alleged debts based entirely on the debt buyers’ own calculations. The lawsuits themselves are then often generated largely by automated process without meaningful scrutiny by any human.

The predictable result of all this is that debt buyer lawsuits are sometimes riddled with fundamental errors. Debt buyers have sued the wrong people, sued debtors for the wrong amounts, or sued to collect debts that had already been paid. In other cases they have filed lawsuits that were barred by the applicable statutes of limitations or were otherwise legally deficient. There have been multiple allegations, some which have led to successful legal cases, that some debt buyer attorneys fail to serve defendants notice of the suits against them in order to obtain large volumes of uncontested judgments. While industry representatives and their critics differ over the prevalence of these problems, their existence is not in serious dispute. Leading debt buyers have settled numerous lawsuits and enforcement actions alleging errors and legal flaws, and the settlement agreements have forced them to throw out tens of thousands of unfounded judgments they had won against consumers.

The debt buying industry has attracted a significant degree of media and regulatory scrutiny in recent years. It has also aroused the very public ire of some law enforcement and regulatory officials. New York’s attorney general has publicly condemned debt buyers who “abuse” the power of the courts at the expense of “hardworking families.” These are stirring words, but the problem with statements like these is that they cast the courts as a second set of victims when in reality they bear direct responsibility for allowing abuses to take root and proliferate.

When debt buyer lawsuits result in unjust and financially disastrous outcomes for poor families, the courts’ own failures and shortcomings are often directly responsible. Fundamental problems with debt buyer lawsuits often come to light only after the companies have already won judgments they were never entitled to, in courts that never asked them to present any meaningful evidence in support of their claims.

This report describes the many ways courts across the US fail to stand up for the rights of disadvantaged defendants in debt buyer lawsuits, or put those defendants’ sophisticated corporate adversaries to their burden of proof. It also describes the devastating impact these failures can have on families who are struggling at the margins of poverty. While new regulatory efforts at the federal level offer some hope of better policing the industry, the federal government can do little to address the shortcomings of state court systems. The rights of defendants will remain under threat until they reform their practices as well.

In the large majority of consumer credit lawsuits—including debt buyer cases—alleged debtors fail to mount a defense to the case against them, sometimes because they never receive proper notice of the suit. Many courts routinely award default judgments to debt buyers in these cases without scrutinizing the claims at issue. One Arizona justice of the peace aptly described this to Human Rights Watch as a “greased rail” process. Many individual courts issue thousands or even tens of thousands of no questions asked default judgments in favor of debt buyers every year. Some judges routinely enter hundreds of default judgments for debt buyers in the space of just a few hours. One judge told Human Rights Watch that he does this at home while relaxing on a Sunday afternoon.

When defendants do attempt to defend themselves in court, they are badly outclassed by their opponents. The plaintiffs are often large corporations represented by top-tier collections attorneys. By contrast, hardly any of the defendants in debt buyer lawsuits have legal representation and many are largely unaware of their rights. Rather than try to mitigate this imbalance, many courts greatly exacerbate it.

When defendants appear alone in court they sometimes confront a gauntlet of obstacles to overcome in order to secure a hearing in front of a judge. Many courts—sometimes under political pressure to clear their dockets quickly rather than carefully—push defendants into unsupervised “discussions” with debt buyer attorneys in hopes that the parties will settle and obviate the need for a trial. In many cases this is precisely what happens, but often it is because these encounters can and do take on a coercive or deceptive character. Many defendants come to court intending to fight the case against them but end up capitulating in the courthouse hallways. Some are persuaded that they have no choice.

This report describes instances where debt buyer attorneys pulled defendants out of court at the encouragement of judges, and then berated or misled them into foregoing a hearing and agreeing to pay the debt buyer everything it had asked for. Often defendants wrongly assume that their adversary’s attorney is giving them unbiased legal advice when they tell them that they will be worse off if they insist on a hearing. Many defendants fail to appreciate that the burden is on the plaintiffs to prove their case, and are easily persuaded that they cannot prevail because they do not possess evidence that disproves the claims against them. Some judges seem only too ready to accept defendants’ sudden capitulation without asking questions about how it was obtained.

Courts in several states have done far worse, creating “judgeless courtrooms” where alleged debtors are summoned to court for the sole purpose of forcing them to participate in unsupervised discussions with debt buyer and other creditor attorneys. In theory, these are resolution conferences that give both parties the opportunity to explore possibilities for compromise. In reality, such proceedings are nothing more than a crudely disguised opportunity for creditor attorneys to pressure defendants into giving up their right to a hearing. Some courts—like the municipal court in Philadelphia—actually allow creditor attorneys to run these proceedings themselves, calling defendants one by one into hallways or back rooms where the large majority is persuaded to give up without ever going in front of a judge. This allows plaintiffs to commandeer the coercive machinery of the courts in service of their own claims to the detriment of defendants’ due process rights and the courts’ own neutrality and integrity.

Even when defendants do manage to have their day in court, they often struggle to articulate whatever legally viable defenses they might have available. Some judges recognize the importance of ensuring fairness in the proceedings they preside over, helping to guide pro se litigants through a hearing and taking proactive steps to confirm that a debt buyer’s case has some indication of merit. Others, bound by overly rigid interpretations of judicial neutrality, refuse to push corporate plaintiffs to meet their burden of proof if the defendant lacks the legal sophistication to do it on their own. The result is that many alleged debtors who may have viable defenses to the cases against them never have a real opportunity to articulate them, simply because they don’t know how.

Some judges do a better job of navigating these problems than others, but there are limits to what individual judges can achieve in the context of unhelpful legal frameworks and court rules. In Michigan, a state district court attempted to subject debt buyers’ requests to garnish the wages of debtors to meaningful scrutiny and rejected numerous garnishment requests due to thousands of dollars’ worth of errors, along with evidence that some of the garnishments related to debts that were invalid or which had already been paid. Debt buyer Credit Acceptance Corporation sued the court arguing that under court rules its clerks had no right to demand supporting documentation in support of the garnishment requests. The state Supreme Court ruled in favor of the debt buyer, affirming that there was no basis in the rules of the district court for doing so. The district court now processes debt buyer garnishment requests quickly and with little or no substantive scrutiny.

This report makes concrete recommendations to courts and to state and federal policymakers which, if implemented, would help safeguard the rights of alleged debtors sued by debt buying companies and protect the integrity of the courts at the same time.

Courts should not issue default judgments to debt buyers unless credible evidence is submitted in support of a claim. A few states—notably New York—have adopted rules to this effect. They should serve as a model for the many states that have so far done nothing.

Just as important, courts should take steps to help unrepresented litigants secure a meaningful day in court regardless of whether they can afford to hire an attorney. As an obvious first step, courts and legislatures should ban rather than encourage the “hallway conferences” and “judgeless courtrooms” some debt buyer attorneys use to deceive and pressure defendants into giving up their right to a court hearing. Courts and state legislatures should also support programs to provide widespread access to pro bono legal advice. Experience has shown that this approach can greatly improve unrepresented defendants’ ability to defend themselves in court. Many of these recommendations would also serve to promote justice in other kinds of debt collection lawsuits filed by other creditors.

In many states, the courts themselves are also badly in need of further assistance and capacity. Too often, elected officials demand that courts clear unmanageably large dockets with impossible speed while at the same time failing to allocate the resources courts need to do that job honestly and fairly.

Although officials with some leading debt buying firms told Human Rights Watch said that they viewed reforms pursued in some state legislatures as unfair and prejudicial against the industry, they also indicated that they would not oppose many of the reforms suggested in this report. To the extent that this is true, it makes the failure of many states and court systems to act even more inexcusable—particularly given how many state law enforcement officials have publicly denounced the litigation practices of debt buyers.

Human Rights Watch takes no position on the policy arguments for or against the sale and purchase of delinquent consumer debt, but we believe Congress should pass legislation that sharply limits the rate at which interest can continue to accumulate on a debt after it is sold on to a third party. Federal law can and should recognize that debt buyers are not in the same position as original creditors—they are seeking to appreciate an investment in bad debt, not to recoup money they have lent under agreed-upon contractual terms. There is no compelling rationale for allowing debt buyers to accumulate interest at credit card rates after they purchase a debt. On the other hand, the fact that current law allows debt buyers to do just that places a huge, unfair burden on alleged debtors and is often the reason poor families struggle to pay these debts down over time. This can come at the expense of alleged debtors’ ability to secure basic economic and social needs such as food, clothing, and medicine. States, for their part, should revisit statutory rates of post-judgment interest that can also be punitively high.

Methodology

This report is based largely on more than 100 interviews with a broad range of litigants, public officials, independent experts, and other stakeholders in a dozen US states, with diverse perspectives on debt buyer litigation. These include judges, clerks, and other court personnel; plaintiff and defense attorneys; consumer rights advocates; debt buyer industry representatives; federal policymakers; academic experts; and people who have been sued by debt buyers. We also observed court proceedings related to debt buyer lawsuits in more than two dozen courts in five states: Michigan, Arizona, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania. In several courts, Human Rights Watch obtained transcripts and other materials related to cases that are particularly striking examples of the broader problems described below.

In May 2015, Human Rights Watch met in Washington, DC with representatives of Debt Buyers Association International (DBA International), the leading industry association of US debt buyers. We maintained ongoing correspondence with DBA officials throughout the process of producing this report to seek their input on a range of issues. Human Rights Watch also conducted two telephone interviews with the general counsel and executive vice president for US operations of Encore Capital, the nation’s largest debt buyer.

Practices in the five states where we carried out field research were examined in varying depth and for different reasons. Michigan and Arizona are highlighted in the report because they are representative examples of states whose court systems and legislatures have been particularly inactive in tackling the problems described in this report. New York was examined primarily as an example of a state that has been unusually proactive in taking steps to tackle the issues. Maryland and Pennsylvania were looked at more narrowly as states where some local courts were reputed to have developed particularly egregious “rocket docket” or “judgeless courtroom” proceedings that trample on the rights of defendants to an extreme degree.

This report also draws heavily on a broad range of external resources, including academic literature, investigative journalism, industry publications, court filings by debt buyers, and materials related to various civil lawsuits and regulatory actions against debt buyers at the state and federal levels. We also sought to obtain empirical data from several courts and state court systems with varying degrees of success. In response to detailed requests by Human Rights Watch, the New York state court system provided detailed information about the huge numbers of cases filed by debt buyers relative to other civil plaintiffs. The New York courts also provided us upon request with the data necessary to create a randomized sample of 500 debt buyer lawsuits drawn from cases filed in courts across the state in 2014. This was a true random sample drawn from a list of every case filed across all New York courts in 2014 by the eight most prolific debt buyer plaintiffs that year. We used that sample to draw out information about the prevalence of default judgments and the frequency with which defendants secure legal representation. The justice courts in Maricopa County, Arizona provided similarly detailed information about the number of cases filed by particular debt buyers and the results of those cases.

In several Michigan and Arizona courts, court officials told Human Rights Watch that they could not or would not produce similar information from their own records. Detroit’s 36th district court failed to respond in any way to repeated requests for basic information about the court’s civil docket, even when some requests were delivered in person to court administrators and framed in ways that court personnel informally told Human Rights Watch would be easy to fulfill.

Background: The United States’ Debt Buying Industry

Millions of people across the United States are in debt to companies they have never done business with and may never have heard of. These firms are called debt buyers. They purchase bad debts from lenders who have given up on trying to collect them and go after the debtors on their own behalf. Together they make up one of the biggest industries most Americans have never heard of.

At any given point in time, hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of US household debt is in some stage of delinquency.[1] When a borrower goes long enough without making a payment, federal regulations require banks to “charge off” the debts, meaning that they no longer count as assets on their balance sheets. Charged-off debts do not simply disappear—creditors still own them and debtors still owe them.[2] But creditors often conclude that it is no longer worth the effort and expense of continuing to try to collect these debts. Rather than accept a total loss, creditors roll many of them into large portfolios that they sell on to debt buyers.

The debt buying industry has grown enormously during the past two decades.[3] In fact, the buying and selling of delinquent consumer debt has become so routine that tens of millions of people across the US either owe money to a debt buyer or have in the past. Most of the debts sold on to debt buyers in any given year are credit card debts.[4]

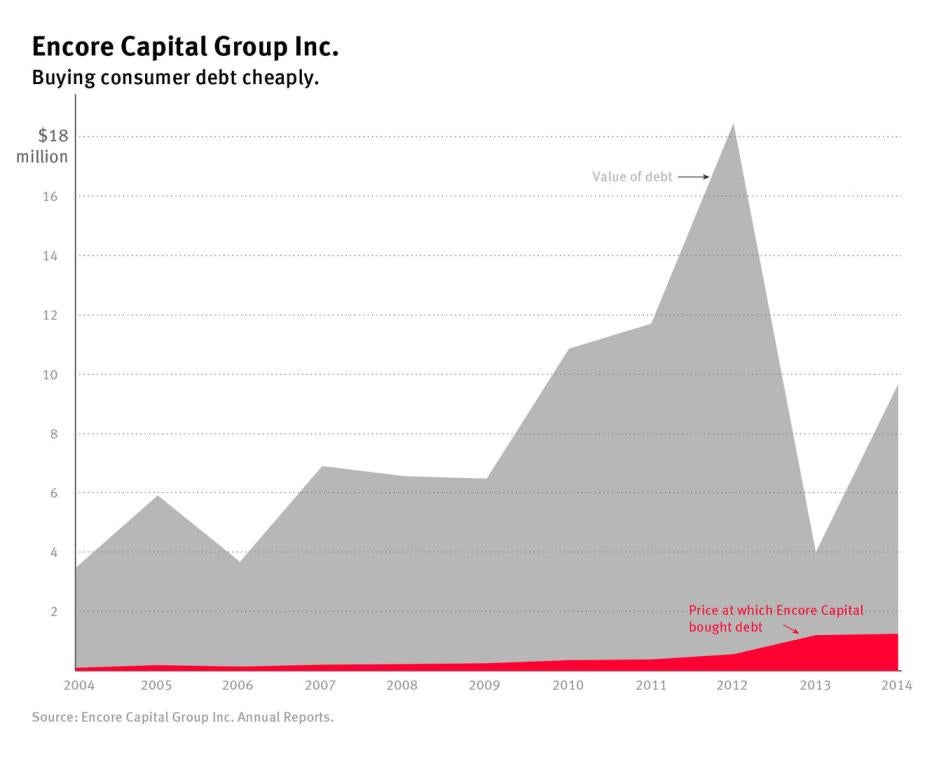

Industry leader Encore Capital, a firm better known to millions of alleged debtors as Midland Funding, is one of a handful of large firms that dominates the market for purchased debt, which is also home to a proliferation of much smaller players.[5] Encore’s balance sheets are more transparent than many of its competitors’ because it is a publicly traded company, and they help illustrate the scale and reach of the debt buying industry. In 2013 and 2014 alone, Encore purchased more than 35 million charged-off consumer accounts with a total face value of nearly $100 billion, and in an average year it successfully collects more than $1 billion from US consumers.[6] The company, which has never actually loaned anyone a penny, claims that one in every five US consumers either owe it money or have owed it money in the past.[7]

The debt buying industry’s business model is rooted in a very simple logic. If debt buyers can acquire debts cheaply enough, and develop efficient, low-cost methods of pursuing debtors, they can realize substantial profits by collecting even a small percentage of the debts they purchase. The prices are certainly low enough. A 2013 Federal Trade Commission study found that during one three-year period, nine of the country’s largest debt buyers paid just $6.5 billion for 90 million accounts with a face value of $143 billion—an average price of just 4.5 cents on the dollar.[8] Leading debt buyers have also managed to keep their collection costs low relative to returns. In 2013, Encore Capital spent just 40.5 cents on US collection efforts for every dollar it managed to pull in.[9]

The debt buying industry and its proponents claim that a thriving market in delinquent debts actually benefits consumers. Debt buyers allow original creditors to recoup some of what they lose when a loan goes bad, and in theory this leads them to extend credit more widely and at more favorable terms than would otherwise be the case.[10] There does not appear to be any solid empirical evidence in support of this claim, however.[11]

Flooding the Courts

Debt buyers can try to collect the debts they purchase in the same way any other creditor would. Some make considerable attempts to locate and contact alleged debtors by phone or mail, or hire third party collection agencies to do this work on their behalf. In general, though, the debt buying industry is heavily reliant on litigation as a collections strategy. A key element of the industry’s overall business model is the large-scale procurement of court judgments against debtors at minimal expense.[12]

Every year, each of the nation’s biggest debt buyers file hundreds of thousands of new lawsuits in courts across the US against people who allegedly owe them money.[13] Encore Capital alone has often filed between 245,000 and 470,000 new lawsuits against consumers in a single year.[14] In fact, debt buyers appear to rank among the heaviest individual users of the nation’s court system.[15] In New York State—which has actually experienced a notable decline in debt buyer lawsuits in recent years—data provided to Human Rights Watch by the state court system reveals that the state’s 20 most litigious plaintiffs filed 142,506 cases in 2014, out of which 67,031—47 percent—were brought by debt buyers. In addition, four of the ten most prolific plaintiffs in that state were debt buyers. By contrast only two original creditors—Discover Bank and Capital One—made the list.[16] Similarly, a 2015 study by nonprofit news organization ProPublica found that collectively, debt buyers filed more lawsuits than any other kind of plaintiff in Newark, St Louis, and Chicago.[17]

On a more local level, debt buyers make up one of the single biggest components of the entire civil docket in many low-level courts.[18] According to data provided to Human Rights Watch by the justice courts of Arizona’s populous Maricopa County (which includes the city of Phoenix), 5 large debt buyers filed more than 21,000 new lawsuits in those courts during a 12-month period beginning in July 2013. This constituted more than 15 percent of all civil case filings.[19] Where numbers are not available, anecdotal evidence paints a similar picture. A court clerk in one busy Michigan district court described debt buyer attorneys bringing in new case filings and wage garnishment requests “by the box load.”[20] New York State Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman told Human Rights Watch that in many states there is “a mill of these cases plowing through the system.”[21]

Some firms, like Portfolio Recovery Associates, try to channel much of their litigation through in-house legal departments.[22] Most, however, farm most of their litigation out to sprawling networks of collections law firms across the US. Debt buyers generally pay these firms on contingency—typically one-third of any amount ultimately recovered from the defendants.[23]

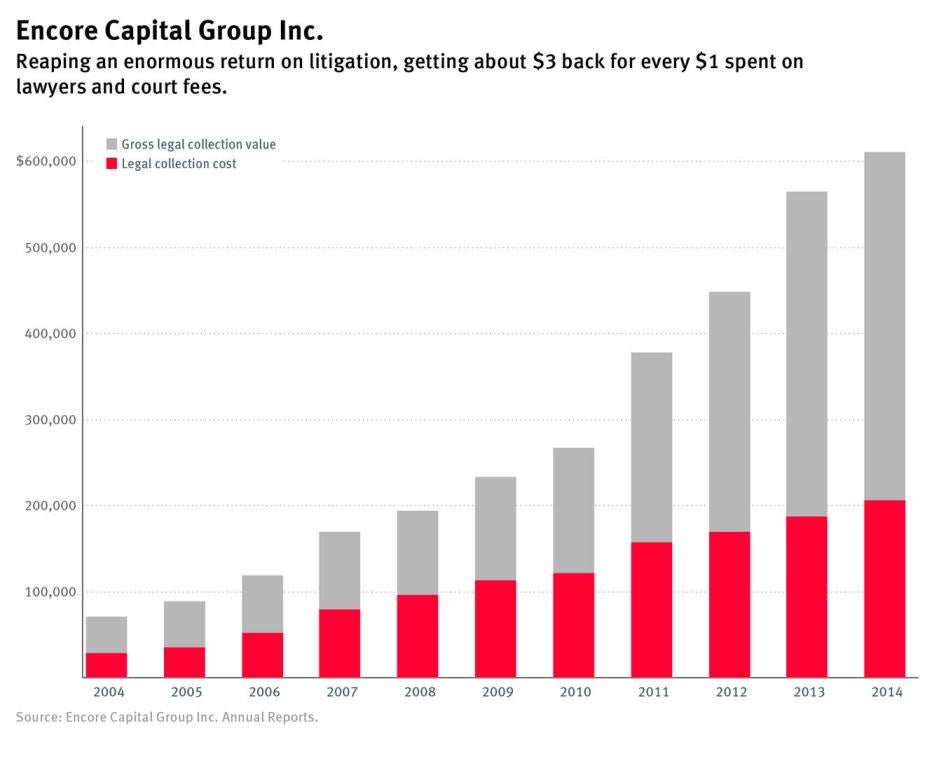

DBA International emphasized to Human Rights Watch that many debt buyers “would rather not litigate accounts; most would rather resolve the accounts voluntarily with the consumer.”[24] Be that as it may, large scale debt buyers are heavily reliant on the courts to secure financial returns on their investments. Encore Capital, which publicly describes legal action against debtors as a “last resort,” earned $610 million through lawsuits against consumers in 2014—more than half of its total collections.[25] Similarly, Portfolio Recovery Associates earned $371 million through legal collections in 2014, half of the $742 million the company collected from consumers that year.[26] In 2014, these two companies alone earned nearly $1 billion by suing alleged debtors in courts across the US.

Available data seems to indicate that for top-tier debt buyers, suing consumers is a reliably profitable endeavor. The quarterly filings of publicly traded firms Encore Capital and Portfolio Recovery Associates indicate that the cost of legal collections hovers at around one third the amount of collections.[27] In 2014, Encore spent $205 million on legal collection efforts that earned it $610 million, while Portfolio spent $139 million on lawsuits that yielded a total return of $371 million.[28] These figures represent approximately a 297 percent and 267 percent rate of return on debt litigation, respectively.

A Diverse Array of FirmsGenerally speaking, debt buyers fall into one of two categories: a handful of large, sophisticated corporations that increasingly dominate the industry, and a vast proliferation of much smaller operations. To some extent each of these two camps blames the other for their industry’s negative public reputation. The debt buying industry has experienced a trend toward upheaval and consolidation in recent years, with the big players getting bigger and many smaller players being pushed out of the business entirely.[29] Some large debt buying firms argue that consumer advocates should welcome this trend. In this telling, larger firms have made great progress in putting in place controls that reduce the possibilities for error and abuse, while supposedly irresponsible and unsophisticated smaller firms are responsible for most of the problems that continue to pervade the industry. Encore General Counsel Greg Call told Human Rights Watch that smaller debt buyers are “much less likely to have meaningful, accurate data” in support of their claims against debtors, partly because they are often buying debt that has been sold and resold several times. “If people really want to change things,” he added, “they should go after these smaller players.”[30] Smaller debt buyers hotly reject this narrative. Rob Warner, the president of the Michigan creditor bar and also the principal of a relatively small debt buying firm, told Human Rights Watch that the industry’s biggest and most publicized scandals have all implicated its biggest firms. “We have been frustrated by some of the high-profile disasters from some of the larger entities,” he said. “The stuff that splashes across the front page is not coming from a small debt buyer.”[31] Brian Fair, head of a small Washington State debt buyer called Fair Resolutions and a director on the Board of DBA International, has argued that it is naïve to cheer the consolidation of power sweeping the industry. “Fewer companies operating in an industry injects the heightened risk of collusion,” he wrote in an op-ed for The Hill, a publication largely geared towards Washington policymakers. “Can you imagine what could happen if only a handful of companies own all the non-performing debt in the industry? Our most vulnerable consumers do not need to face this additional risk.”[32] |

Debt Buyer Lawsuits and Poverty

Encore Capital General Counsel Greg Call told Human Rights Watch that he was perplexed as to why debt buyers seem to receive more media scrutiny than other kinds of creditors.[33] This is a legitimate perspective and it is important to acknowledge that many of the problems described in this report are rooted in larger dysfunctions with the way courts approach all manner of debt collection lawsuits. In a landmark 2010 report, the US Federal Trade Commission concluded that “[t]he system for resolving disputes about consumer debts is broken” and that “neither litigation nor arbitration currently provides adequate protection for consumers.”[34]

Within this broader context, though, Human Rights Watch research indicates that there are unique problems with the way many courts approach debt buyer lawsuits. These problems raise human rights concerns from the perspective of fair adjudication of rights, as well as their negative impact on the security of the defendants’ basic economic and social rights such as rights to housing, food, and clothing. This makes it imperative for court systems and policymakers to urgently address these problems squarely and on their own terms. In part and as described below, this is because debt buyer litigation is resolved by the courts following a process which fails to fairly protect the interests of both parties and has been prone to large-scale patterns of error and alleged abuse that many courts have largely failed to address effectively, or in some cases even to recognize.[35] Simply put, courts hand down far too many judgments to debt buyers without actually knowing whether the alleged debts are real, enforceable, and correctly calculated. But what lends these broader problems’ true urgency is the simple fact that debt buyer lawsuits can and do destabilize the precarious efforts of struggling families to make ends meet and secure their basic social and economic rights.

Many of the debts owned by debt buyers were charged off and sold on to them in the first place precisely because borrowers could not afford to keep up with payments. This does not mean that debtors should not pay what they owe, but it does mean that the courts should take care to ensure that the judgments they hand down in debt buyer cases have merit. For defendants living in or at the margins of poverty, the evidentiary and due process concerns highlighted in this report take on an outsized level of importance and urgency.

In Detroit, Human Rights Watch interviewed a woman who was trying to raise two young children on her own on the $10 an hour she earned at a local Dollar General store. Though struggling to make ends meet she was grateful for the work, coming as it did on the heels of a long period of unemployment. But after just a month on the job, a debt buyer who had already obtained a court judgment against her began garnishing 25 percent of every paycheck. She claimed she had not even been aware that a judgment had been entered against her to begin with, and that the wage garnishment had caused real and sudden hardship for her family. Speaking through tears, she told Human Rights Watch:

I don’t have money for my baby’s diapers. My lights and gas is off right now. My paycheck is about 300 a week and sometimes I only bring home 220. I can’t afford [the garnishment] out of my check. I barely even get anything to begin with.[36]

In the corridors of more than a dozen courthouses, Human Rights Watch spoke to many other alleged debtors in similar straits.

In an Arizona courtroom outside of Phoenix, one person who had just had a judgment entered against her for $2,164 in a debt buyer case explained, “I’m barely making it. If they garnish my wages I couldn’t even afford to buy groceries. We struggle with that as it is.”[37]

In New York, a single mother told Human Rights Watch that she had multiple default judgments entered against her by debt buyers and other creditors for a total of more than $15,000. She said—and later proved to the satisfaction of a New York judge―that she had never received notice of the lawsuits and only learned about them after the judgments were entered. “When I saw the amount I was like, ‘There is no way I am ever going to repay this,’” she told Human Rights Watch. “I mean, I’m struggling on what I have now, can you imagine if they took money out and you get less?”[38] She was fortunate, with the help of a pro bono legal assistance program, she eventually got all of the judgments reversed.

There is only scattered empirical evidence to prove the point, but it seems clear that a large proportion of debt buyer cases involve defendants who are either poor or struggling at the margins of poverty. The suits also seem to fall disproportionately on minority communities. Dozens of attorneys, public officials, judges, and consumer advocates who spoke to Human Rights Watch agreed with this assessment, and the data that does exist also tends to reinforce the point.[39] This aspect of debt buyer impact raises particular concern because the disproportionate impact intersects with prohibited grounds of discrimination such as race, social origin, or status, and under human rights norms may constitute indirect discrimination.

A study by New Economy Project, a nonprofit organization, of debt buyer lawsuits in New York City found that in a sample of people with default judgments entered against them by debt buyers, 95 percent lived in low or moderate-income neighborhoods and that the majority lived in predominantly Black or Latino neighborhoods.[40] A 2015 ProPublica study found that in Newark, New Jersey; Chicago, Illinois; and St. Louis, Missouri, debt buyer lawsuits are “far more common” in Black neighborhoods than in others. In Newark, the study found that more than half of all court judgments entered against people living in predominantly Black neighborhoods stemmed from debt buyer suits.[41] A New York program that provides pro bono legal advice to defendants in debt cases in the Bronx reports that “the vast majority of CLARO visitors have very low incomes.” More than half of its respondents reported income of less than $1,500 per month, and more than half of the consumer credit cases brought to CLARO are debt buyer cases.[42]

An uneven patchwork of federal and state laws does protect a minimum core of poor defendants’ income from garnishment or seizure by debt buyers or other creditors. But this legal framework is inadequate, and its protections often add up to far less than what a family needs to keep from being pushed deeper into poverty and financial instability by an adverse judgment. For example, federal law prohibits creditors from garnishing a debtor’s social security payments, caps wage garnishments at 25 percent of a debtor’s disposable income, and protects people’s directly deposited federal benefits.[43]

The laws in some US states provide additional protections, but a comprehensive study by the National Consumer Law Center found that “despite the importance of exemptions laws, not one US state meets five basic standards” to prevent garnishment and property seizures from destroying debtors’ ability to earn a livelihood, pay basic utilities, housing, and transportation costs, and maintain a living wage. The NCLC report found that a handful of states—Alabama, Delaware, Kentucky, and Michigan—“allow debt collectors to seize nearly everything a debtor owns,” with six others offering only marginally better protections.[44]

Only handful of states prohibit creditors from garnishing a person’s bank account to the point that it sinks below a prescribed minimum balance.[45] What this means, as ProPublica noted in a 2014 report, is that in many states “a collector can't take more than 25 percent of a debtor's paycheck, but if that paycheck is deposited in a bank, all of the money in the account can be grabbed to pay down the debt.”[46] In Michigan, debt buyers and other creditors are able to garnish a debtor’s entire state income tax return to satisfy a debt—a source of income that is particularly important to many poor US families.[47]

A 2015 study by ProPublica found that debt collection lawsuits of all kinds are disproportionately prevalent in Black communities. The study also highlighted a predominantly Black suburb of St. Louis called Jennings that is saturated with debt collection lawsuits, including debt buyer lawsuits. The study notes that:

The average family in Jennings has an income of just $28,000, an income level at which, on average, families spend all of their income on basic necessities, federal survey data shows.… A garnishment hits this kind of household budget like a bomb.[48]

Many leading debt buyers say that they only sue people who they believe possess the means to pay. But as an official with one leading debt buyer acknowledged to Human Rights Watch, “You are trying to do this the right way—to pick the ones that have the ability to pay but not the willingness. Do we always get that right? No.”[49]

Runaway Interest and Costs

Most debt buyer lawsuits involve credit card debts, and long periods of alleged non-payment by the defendant. These two factors combine to produce jaw-dropping accumulations of interest in many debt buyer lawsuits. A debt buyer who purchases a credit card debt of $2,000 carrying a 25 percent rate of compound interest would see the debt grow to $6,103 if they waited 5 years to secure a court judgment against the debtor.

Such scenarios are quite common. Debt buyers often wait until close to the end of the applicable statute of limitations to secure a court judgment.[50] One official with a leading debt buying company maintained that this is primarily due to the cost of litigation rather than a desire to accumulate as much interest as possible. “Generally you try to collect by less expensive means right up until the statute of limitations is about to expire,” he said, “and only then do you file suit.”[51]

From the perspective of the person who is ultimately sued, a debt buyer’s motives for waiting several years to sue after acquiring a debt are immaterial. That decision has the practical effect of growing a debt to its largest possible size. This can have a devastating impact on people who are already in economic distress. As Michigan Judge William Richards put it to Human Rights Watch:

A lot of them will admit they used the credit card but say, “There’s no effing way I racked up such high charges.” Then I have to explain compound interest to them. Typically the debt is several years old by the time LVNV or Midland sues. It’s unfortunate. Memories fade. When they get hit with a lawsuit they say, “This is a joke. I can’t owe that much.” I tell them, “You admit you could have charged $2,500. That, at 20 percent, is up to $3,000 after just one year, then $3,600 after two years.” I say, “Do you see, ma’am, why you are on the hook for $4,300?” And they are stunned—stunned.[52]

After a judgment is handed down, post-judgment rates of interest that are either set or capped by state law kick in.[53] These are generally lower than the contract rates attached to credit card debts, but they are often quite high, multiple times the rate of inflation. Many states cap post-judgment interest at 10 percent or even higher.

In Michigan, post judgment rates of interest can be as high as 13 percent in many purchased debt cases.[54] Human Rights Watch examined one case where debt buyer Credit Acceptance Corporation secured a court judgment against a defendant for $4,902.56 in 2004 in Flint, a city that has long been a potent symbol of post-industrial US poverty.[55] In 2014, Credit Acceptance applied to have the judgment renewed, claiming that the debt had increased in size to $11,440.96 with 13 percent post-judgment interest.[56]

For people who lack the means to make significant monthly payments, high rates of post-judgment interest can make it hard to make any headway paying off their balance, and substantially increase the amount they must ultimately repay. In a state that allows debt buyers to accrue 10 percent post-judgment interest, a debtor who is able to make consistent monthly payments of $50 on a debt of $3,000 will ultimately pay 30 percent more than a person of greater means who can afford to pay $200 per month.[57]

The impact of post-judgment interest becomes even more pronounced when a debtor fails to make consistent payments. Any period of lapsed payments can see all progress made in paying off their obligations wiped out or even reversed. In another case out of Flint, Midland Funding secured a judgment against an alleged debtor in 2004 for $959.22 and began accumulating post-judgment interest at 13 percent as allowed by state law. Ten years later, the alleged debtor had made a total of $735 in scattered payments to Midland, but had only managed to reduce the balance owed by $12.[58]

Human Rights Watch does not argue that debt buyers or other creditors should be barred from pursuing claims against people simply because they are poor. Rather, this report simply argues that because of the devastating financial impact a successful debt buyer lawsuit can have on people struggling to make ends meet, policymakers and the courts have a compelling interest in ensuring that the cases have merit and that justice is done. Courts should certainly take care to ensure that debt buyer plaintiffs are not able to secure judgments against the wrong people, for the wrong amounts, or in pursuit of debts that are not legally enforceable. But unfortunately and as this report describes, that is exactly what is happening in many courts across the US.

Attorney’s FeesSome debt buyers routinely seek to charge defendants attorney’s fees in the cases they win, a practice that can add further still to the misery inflicted by high rates of contract and post-judgment interest. In Arizona, Human Rights Watch observed several cases brought by Cortez Investment Company, a debt buyer based in Tucson. Cortez regularly asked courts to order defendants to pay attorney’s fees in excess of $300 in cases where the underlying debt amounted to less than $1,500. In one typical case, Cortez sought $312 in attorney’s fees and $426 interest on a debt that was valued at $1,422.51 when the company purchased it.[59] David Hameroff, the attorney who represents Cortez in thousands of cases filed across Arizona every year, is also the debt buyer’s principal owner. In essence, the law allows him to force defendants—many of whom cannot afford an attorney of their own—to pay him a fee for using the courts to pursue them on his own behalf. Reached by phone, Hameroff declined to comment on his litigation practices.[60] |

Allegations of Error and Abuse in Debt Buyer Litigation

Debt buyer lawsuits have been plagued by instances of error and abuse. In thousands of cases across the country and as the following pages describe, debt buyers have:

- Prevailed against consumers in lawsuits that were legally deficient or should never have been filed, including suits that were barred because they were past the applicable statutes of limitations;

- Obtained default judgments against defendants who never received proper notice that they were being sued;

- Sued and won court judgments against—or garnished the wages of—the wrong people or for the wrong amounts;[61] or

- Won court judgments that state and federal regulators or the courts later found to be rooted in false evidence or misleading, “robo-signed” affidavits.

The prevalence of these problems—and the extent to which they reflect malfeasance, incompetence, or genuine misunderstandings about the application of relevant law—is hotly contested.[62] There can however be no serious dispute that the problems are real. In several cases, state and federal officials have forced leading debt buyers to pay fines, to vacate thousands of legally deficient or improperly obtained judgments, and/or to agree to reform their collections practices. For example:

- In January 2015, New York State reached a settlement with Encore Capital in a lawsuit alleging that the company had illegally sued consumers over debts that were time-barred by New York law. The settlement required Encore to vacate 4,500 judgments worth roughly $18 million, agree to reform its debt collection practices, and pay a $675,000 penalty.[63] The state also alleged that Encore employees had “‘robo-signed’ … hundreds of affidavits submitted in support of debt collection actions each day without reviewing the affidavits and without possessing personal knowledge, as alleged in the affidavits, about the claimed debts and the amounts owed.”[64] On the issue of time-barred debt, New York reached a similar settlement with debt buyers Portfolio Recovery Associates and Sherman Financial Group in 2014, vacating some 3,000 judgments worth $16 million.[65]

- In September 2015, the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB) entered into a consent decree with Encore Capital and Portfolio Recovery Associates that requires the two companies to refund tens of millions of dollars to consumers, halt collection on more than $100 million in debt, pay financial penalties, and overhaul their collections practices. The CFPB alleged that the two companies “bought debts that were potentially inaccurate, lacking documentation, or unenforceable. Without verifying the debt, the companies collected payments by pressuring consumers with false statements and churning out lawsuits using robo-signed court documents.”[66] In response, Encore said that the settlement related to “two isolated issues, which are not current practice and were changed some time ago” and that “the outcome is not about current law or rules already on the books, but instead about the CFPB subjecting companies to its own interpretations that have never been codified or adopted.”[67]

- In 2014, the CFPB filed a federal lawsuit against a Georgia law firm that files hundreds of thousands of cases every year on behalf of banks, debt buyers, and other creditors. The CFPB suit alleged that one attorney at the firm had signed over 130,000 lawsuits during a two year period. It accused the firm of “operating a debt collection lawsuit mill that uses illegal tactics to intimidate consumers into paying debts they may not owe” and alleged that it “churns out hundreds of thousands of lawsuits that frequently rely on deceptive court filings and faulty or unsubstantiated evidence.”[68]

- In 2012, the US Department of Justice reached a settlement and consent decree in a suit against Asset Acceptance, a large debt buyer that has since been acquired by Encore Capital.[69] The suit alleged that the company had wrongfully tricked consumers into reactivating debts that the company could not otherwise have sued on because they were past the statute of limitations.[70] It also alleged that the company had “systematically failed to conduct reasonable investigations” when consumers claimed that the debts Asset Acceptance was trying to collect had already been paid or were not theirs. The company paid a $2.5 million penalty and agreed to reform various aspects of its collections activities.[71]

- In 2011, Encore Capital agreed to settle a raft of class action lawsuits involving at least 1.4 million plaintiffs for $5.7 million.[72] Thirty-eight state attorneys general publicly opposed the deal, arguing that it did not hold Encore meaningfully accountable and would help it and other debt buyers evade meaningful enforcement and accountability down the line. Federal regulators also criticized the deal for similar reasons.[73]

A deeply troubling common thread runs through all of these cases, and many others. In courts across the country, debt buyers have been consistently able to secure large numbers of illegitimate judgments against alleged debtors on the strength of evidence that is later exposed as inadequate, deceptive, or inaccurate.[74] When commentators rush to condemn the debt buying industry itself, there is one question they do not ask often enough: how is any of this possible, if the courts are doing their job?

Rubber Stamp Justice: Default Judgments without Evidence or Scrutiny

More than a few public officials have spoken out publicly against debt buyers who, in the words of New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, “abus[e] the power of the courts at the expense of hardworking families.”[75] Similarly, in November 2015 a Missouri trial court judge lambasted debt buyer Portfolio Recovery Associates’ entire business model as “irresponsible” and “reprehensible:”

This Defendant owns debt in all 50 states—750,000 accounts in Missouri, 37,500 of which are in litigation. It shows no remorse. Its business model is irresponsible and preys against the financially vulnerable. This Defendant does not respect the Court’s rules. And, especially reprehensible is Defendant’s use and abuse of our court system to harm the Plaintiff.[76]

These are stirring words, but the myriad problems with debt buyer litigation do not add up to a simple story of corporate malfeasance or incompetence. As this report describes, the courts’ own failures and shortcomings are a key part of the problem. The problem with statements like the two cited above is that they cast the courts as innocent bystanders, or perhaps even a second set of victims. In reality, the courts are central to the problem and bear direct responsibility for the translation of defective lawsuits into court judgments that hurt poor families. As Karen Meyers, then-New Mexico’s assistant attorney general for consumer protection, put it to Human Rights Watch, “It’s a perfect storm of attorneys not doing their due diligence before filing a claim, the client not actually having the evidence that they are really owed the debt, and the judges saying, ‘Well, it’s a default judgment so I just sign the papers, I don’t ask.’”[77]

As the following pages explain, by now the courts that adjudicate debt buyer lawsuits ought to know that these cases raise unique and pervasive evidentiary concerns, as well as the potential for widespread error and abuse. They should also know that many of the defendants in debt buyer cases are poor enough that an adverse judgment can be devastating to their families’ precarious financial stability, and that they often lack the means to mount an effective legal defense. Yet many courts take no proactive steps to confront these problems. Many low-level courts across the country churn out judgments in favor of debt buyer plaintiffs without asking for any meaningful evidence—and indeed without subjecting the plaintiffs’ claims to any real scrutiny at all.

The Default Judgment Problem

The central reality of debt buyer litigation is that only a tiny proportion of cases ever go to trial. In a typical court, between 60 and 95 percent of all debt collection lawsuits, including debt buyer cases, end with default judgments in favor of the plaintiffs.[78] Most defendants either do not answer the case against them at all, or do not appear to defend themselves in court.[79]

Where are the Defendants?

In Arizona, the presiding judge of the Maricopa County Justice Courts told Human Rights Watch that he attributed the low rate of defendant participation in debt buyer cases largely to “despair” on the part of alleged debtors who feel helpless in the face of debts they cannot afford to pay.[80] Debt buyers and their attorneys, for their part, often cast defendants’ failure to respond to a lawsuit as a failure of personal responsibility. Greg Call, General Counsel of Encore Capital, put it this way:

By the time [a debt] reaches me, our consumer is part of a subset of people who’ve survived so far by failing to engage with the problem. Our consumer in this space has built up what until this point in the process has been a very effective defense mechanism which is, “If I ignore it I don’t have to deal with it.” … That works up until the litigation process starts. If you continue to deploy that defense mechanism at that stage, the immediate byproduct of that is a default judgment.[81]

There is truth to this analysis with respect to some defendants. But the overwhelming silence of alleged debtors sued by debt buyers—in cases they have a clear financial interest in contesting—is a complex phenomenon whose underlying causes are widely debated.[82]

Confusion and Misinformation

Many alleged debtors have never heard of the debt buying industry, let alone the particular company suing them. Furthermore, they generally have no way of knowing that a creditor they did business with sold their debt to a third party until the debt buyer itself informs them of the fact. Some states require debt buyers to clearly identify the original source of the debt when issuing notice of a lawsuit to a defendant, but others do not. One Michigan judge told Human Rights Watch that he regularly entered default judgments in favor of debt buyers only to see the alleged debtor later try to have it overturned, explaining that they had initially failed to answer the complaint because they “had no idea who these people were.”[83]

The overwhelming majority of defendants in debt buyer cases lack legal representation, and for them, the basic requirement that they respond to a debt buyer lawsuit can be overwhelming.[84] In New York, Human Rights Watch interviewed a woman named Mary who was sued by several debt buyers. She ultimately prevailed in all of the cases against her. Mary told Human Rights Watch she doubted whether she would even have managed to answer the complaints had she not gotten pro bono legal assistance from a program called CLARO.[85] “The papers they send you in the mail—‘reference this, reference that,’—it can make you crazy just looking at it,” she said. “They send you this long thing referencing this case and that case and I’m just like, ‘What in the world does this mean?’”[86]

Whether inadvertently or by design, some debt buyer attorneys contribute to this problem by serving defendants with complaints that make the act of responding to the case seem more complicated than it really is. Some attorneys who defend people in debt buyer lawsuits allege that this can be a deliberate tactic. Michigan consumer rights attorney Ian Lyngklip told Human Rights Watch that some debt buyer attorneys “send out reams and reams of paper that they can churn out with the click of a button. People have no idea how to answer it all and they effectively cause them to default even if they are trying to answer. They are overwhelming people with paper and expertise they can’t handle.[87]

Greg Call of Encore Capital acknowledged that the notice defendants receive from debt buyers can be daunting, while rejecting the idea that this was deliberate. He told Human Rights Watch that:

Lawyers are horrible at dumbing down their average work product to the average reading level of our consumer. We generally shoot for a seventh or eighth grade reading level. They are trying in good faith to communicate, but to the average consumer it’s what you described—it’s too dense, it’s intimidating, and it’s scary.[88]

Human Rights Watch reviewed several Arizona cases in which Cortez Investment Company, a Tucson-based debt buyer filed for summary judgment against unrepresented defendants. The justice of the peace assigned to those cases told Human Rights Watch that “many if not most judges are simply looking for something that disputes a material fact, even if it is filed in the wrong format. Our clerks are train[ed] never to reject a pleading.”[89] But defendants have no way of knowing that if they do not have access to sound legal advice, and would never guess it from the correspondence they received from Cortez. The company served defendants with motions for summary judgment asserting that any reply must include “affidavits, exhibits, or other material that establishes each fact as admissible evidence” and a “memorandum of law that … provides legal authority in support of your position.”[90]

Concerns about Notice

Many people claim that they were not aware that a debt buyer had sued and won a judgment against them until the plaintiff began garnishing their paychecks or secured a court order seize their property.[91] Many of these claims are false or mistaken, but inadequate notice and even “sewer service”—when process servers falsely claim to have served a defendant with notice—have been real problems in many debt buyer lawsuits.

Debt buyer lawsuits may be unusually prone to bad service simply because the plaintiffs often have no idea where their alleged debtors—people they have had no prior contact or relationship with—live when they purchase the accounts. Addresses passed on to them at the time of sale may be years out of date, and other basic information that might help locate the alleged debtors may be sparse or marred by inaccuracies. This is particularly true of debts that have been sold multiple times across different buyers and are several years old. Robert Warner, president of the Michigan creditor’s bar and himself a debt buyer, acknowledged to Human Rights Watch that, “We’re certain that many, many people—not everyone—receives the summons and complaint. You can’t be sure in all cases.”[92]

Industry critics allege that some debt buyers or their attorneys cut corners when serving notice because a default judgment is the cheapest and most efficient way to prevail in court. Pat Clawson, a process server in Flint, Michigan who is also the vice president of a statewide association of process servers told Human Rights Watch that:

Almost anybody can be found using online information combined with shoe leather. But it requires some work. Most of these law firms and debt buyers do not want to do this. They don’t want to take the effort it takes to find people.… They want to spend zero money and pretend that they know they’ve actually served their defendant.[93]

Allegations of “sewer service” have repeatedly arisen in the context of debt buyer litigation. A recent class action lawsuit in New York alleged that more than 100,000 people were victimized by a “default judgment mill” that used “sewer service” as a tactic to obtain default judgments in debt buyer lawsuits.[94] In November 2015, the suit was settled under terms that require the defendant debt buyers to pay $59 million to the plaintiffs’ class and curb some of the defendants’ collection practices.[95]

One New York woman who had a default judgment entered against her in a debt buyer case told Human Rights Watch that, “The process server said he’d served a 200 pound white man with glasses,” she recalled. “My husband at the time was a dark-skinned Hispanic man.” She was eventually able to have the judgment overturned with the help of a free legal assistance program.[96]

Nationally, there is no empirical data to indicate whether failure to serve defendants properly is a significant cause of the high default rates in debt buyer cases. Some state court systems have begun taking proactive steps to help ensure that defendants are properly served in debt buyer lawsuits.[97] But many other courts rely exclusively on plaintiffs to ensure that defendants are served notice of a lawsuit and do little to ensure compliance. This leaves them with no way of determining whether defective service is a significant problem in the debt buyer cases they adjudicate. When Human Rights Watch asked one Arizona justice of the peace whether he thought most of the defendants he had issued default judgments against in debt buyer cases had been properly served notice he replied simply, “We don’t know.”[98]

Rubber Stamp Justice: The Absence of Judicial Scrutiny

Courts are not required to issue default judgments simply because a defendant fails to appear or otherwise defend herself. They do so at their own discretion after considering whether the claims are lawful and appear to have merit.

As the following pages describe, debt buyer lawsuits have been marred by a unique combination of profound evidentiary problems. Debt buyers do not always possess evidence in support of their legal claims, and the evidence they do possess has sometimes been explicitly flagged as unreliable by the creditors who generated it.

Despite all this, many judges behave as though debt buyer plaintiffs are entitled to default judgments as a matter of right when defendants fail to answer the case against them. They issue default judgments to debt buyers with alarming automaticity and speed, without asking for evidence in support of the claims or subjecting them to scrutiny. Many courts neither ask for nor receive any evidence that debt buyers are suing the correct people for the correct amounts, that they are legally entitled to sue, or that they actually own the debts at issue. In fact, many courts issue judgments in favor of debt buyers without knowing whether the plaintiffs even have access to any evidence in support of their claims. As one leading study of debt buyer litigation practices put it:

Instead of proof, arguably creditors rely on a de facto system of “default judgment justice” wherein the creditors know that very few defendants will ever challenge the lawsuit, and overwhelmed courts and judges will simply enter default judgments in order to keep the flood of paperwork from bringing the workflow to a halt.[99]

One Arizona justice of the peace told Human Rights Watch that he had processed 60 default judgments in debt buyer cases at home over the course of about four hours on a Sunday afternoon, a rate of one default judgment every four minutes assuming that he worked without pause.[100] In many courts, default judgments are actually processed—and for all practical purposes decided—by clerks or other non-judicial court personnel. In Philadelphia’s municipal court a Human Rights Watch researcher watched a trial commissioner (an employee of the court who works under a judge) process more than 100 default judgments in the space of just two hours while simultaneously presiding over another proceeding.[101]

Human Rights Watch asked New York Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman for his perspective on the default judgment problem in debt buyer cases, which his courts have recently become more proactive in trying to tackle responsibly:

You were signing a lot of shallow judgments. It’s hard to make a blanket statement that they all had merit.… We have all been remiss in letting these large purchasers of debt rule the day in court without ensuring the basic principles of setting court judgments based on evidence are met.… You can’t get by just by throwing a spreadsheet at us or some kind of form affidavit that does not tell us anything. We get cases with the wrong debtor being sued, cases with the wrong amount of debt being sued for, and cases with no proof that should warrant a judgment.[102]

New York and a handful of other states have taken steps to increase the evidence required from debt buyers before they can obtain a default judgment. Most states, though, have taken no steps to tackle the unique challenges these cases present to the integrity of the courts. A few states have gone in the wrong direction, exacerbating the problem with laws aimed at reducing courts’ ability to question the evidence in support of uncontested debt buyer lawsuits.[103]

Questionable Records and the Problem of Warranty

Debt buyers win many default judgments without ever possessing the kind of evidence they would need to prevail at trial against a competent defense. In some cases, the creditor selling a debt refuses to provide any detailed records to the purchaser. Sometimes, the buyers obtain only a simple spreadsheet with a few cells of information—such as names, social security numbers, amounts allegedly owed, and last known addresses—related to thousands of different accounts.[104]

What’s more, in some of the contracts underlying the sale of consumer debt the seller explicitly refuses to warrant that any of the information it has provided about the debts being sold is accurate. In one widely circulated agreement governing the sale of a portfolio of debt to a large debt buyer called CACH, the seller explicitly refused to warrant:

- That the amounts allegedly owed were accurate;

- That the loans complied with any relevant federal or state laws; or

- That any of the loans being sold were valid, enforceable, or collectable.[105]

For good measure the agreement also declined to warrant “any other matters related to the loans.”[106] Debt buyers who go on to file lawsuits in situations like this do so without any sound basis for believing that they are suing the right people for the right amounts, or even that the debts they have purchased are real.

One independent study by Dalie Jiminez, a professor at University of Connecticut Law School, examined a set of 84 sale agreements and concluded that “in many contracts, sellers disclaim all warranties about the underlying debts sold or the information transferred.”[107] In 2013, the Federal Trade Commission concluded that leading debt buyers generally “obtained very few documents related to the purchased debts at the time of sale or after purchase” and that “sellers generally disclaimed all representations and warranties with regard to the accuracy of the information they provided at the time of sale about individual debts.”[108]

The FTC study was based on sales of debt made in 2008. Officials with several leading debt buyers told Human Rights Watch that these problems are rapidly becoming a thing of the past, at least when it comes to new portfolios of debt being sold by banks. Those interviewees maintained that most current contracts for the sale of purchased debt include reasonable warranties of accuracy and that industry trends are moving rapidly in that direction, partly because banks are under increasing regulatory pressure to do so.[109] One official with a leading debt buying company told Human Rights Watch that contracts like the one described above are “outliers” that attract a disproportionate amount of public scrutiny because “it’s a really fun anecdote to tell.”[110]

There is no publicly available empirical data to prove the point one way or the other. Neither sellers nor debt buyers publish the terms of these contracts, and most courts do not require debt buyers to disclose them when filing a lawsuit.[111] But the SEC filings of publicly traded debt buyers undercut industry assertions to some degree. Industry leader Portfolio Recovery Associates, for example, noted in its March 2015 10-K filings that:

In pursuing legal collections, we may be unable to obtain accurate and authentic account documents for accounts that we purchase, and despite our quality control measures, we cannot be certain that all of the documents we provide are error free.[112]

The reality may simply be that there continues to be wide variation in the warranties different debt buyers are able to obtain from different creditors. Greg Call of Encore Capital told Human Rights Watch that, “We stand downstream from banks and are buying a product from them. The warranties we get largely reflect our negotiating position with the banks in the course of that transaction.”[113]

It is also important to emphasize that prevailing trends with regard to new contracts governing the sale of charged-off debt are of only limited immediate relevance to the courts. Hundreds of thousands—perhaps millions—of the debt buyer lawsuits now working their way through the courts relate to debts that were sold several years ago, with some being resold multiple times in the interim.

A “Gold Standard” That Falls ShortThe Debt Buyers Association International (DBA) is an industry association of US debt buyers and related firms that counts 38 debt buyers among its members, a mix of industry leaders and smaller firms. DBA has developed a code of ethics and a voluntary certification program for its debt buyer members. The group describes these as the “gold standard” of good industry practice with a “focus on the protection of the consumer.”[114] DBA also maintains that “due in part” to the development of these standards, “most” contracts now contain basic warranties of accuracy and lawfulness.[115] DBA’s certification standard does not actually require member companies to secure such warranties, however. Instead, it requires only that they use “commercially reasonable efforts” to negotiate the inclusion of warranties that: · The seller actually owns the accounts it is selling to the debt buyer; · The accounts being sold are “valid, binding, and enforceable obligations;” · The accounts were “originated and serviced in accordance with law;” and · That the data sellers provide to debt buyers about the accounts is “materially accurate and complete.”[116] If “commercially reasonable” efforts to negotiate the inclusion of these assurances fail, member companies remain free to enter into sale agreements that do not contain any of them. The standard provides no definition of or guidance on what constitutes a “commercially reasonable” effort. |

Many courts have failed to appreciate the importance of the warranty problem. Because the original creditors in debt buyer cases were usually banks, courts tend to assume that debt buyers have records just as reliable as those a bank would be able to produce in a lawsuit on its own behalf. In 2014, Maryland’s highest court decided a case that hinged partly on the reliability of account statements submitted by debt buyers by referring without discussion to past decisions that presume bank records to have a “strong indicia of reliability.” In a dissent to that ruling, one judge noted pointedly that:

It seems odd to accord special reliability to those records when the businesses that actually created and maintained them may have disclaimed their reliability … we should not decide these cases by according special reliability to the business records offered by one party to a dispute, particularly when they belong to a third party and there may be a legitimate question as to their accuracy.[117]

Courts’ failures to make inquiries on this fundamental point gives rise to a situation where in at least some cases:

- Debt buyers may have no real way of knowing whether they are suing the correct people for debts they actually owe, and for the correct amount; and

- Courts issue default judgments in favor of debt buyers without knowing whether the plaintiff possesses reliable evidence in support of their claim.

These are not just hypothetical problems. In July 2015, the CFPB, 47 state attorneys general, and the District of Columbia alleged that JP Morgan Chase had sold debts on to debt buyers that:

· Were fraudulent and not actually owed by the alleged debtor;

· Had already been paid in full;

· Were not actually owned by Chase at the time of their “sale;” or

· Were otherwise uncollectable.

Chase also provided debt buyers with inaccurate information about the amounts owed on some accounts. In doing so, the CFPB noted, “Chase subjected certain consumers to debt collection by its debt buyers on accounts that were not theirs, in amounts that were incorrect or uncollectable.” Chase agreed among other things to pay $166 million in penalties, to pay some $50 million directly to impacted consumers, to permanently halt collections on more than 528,000 accounts, and to reform its debt sales practices.[118]

Allegations of “Robo-Signing”

Courts generally require plaintiffs to submit an affidavit by an employee or agent, attesting that they have personal knowledge of the debt at issue and believe that the allegations presented in the lawsuit are true and accurate.[119] But as an official with Sherman Financial Services acknowledged to Human Rights Watch, the only thing a debt buyer employee can truthfully attest to is that the information presented in a lawsuit matches the information contained in whatever records were passed on to the debt buyer at the time of sale.[120] Since debt buyers generally use those same records to automatically generate the data presented in a lawsuit, this exercise in verification is essentially circular and substantively meaningless. Simply put, the affiant has done nothing more than compare a few lines of data against computer-generated copies of themselves.[121]

Several high-profile lawsuits against debt buyers have featured evidence that employees sign hundreds of affidavits every day with little pretense of reviewing them for accuracy. For instance:

- In a deposition connected to a suit against Encore Capital in Ohio, a company employee testified that he signed between 200 and 400 affidavits a day and that few of them were reviewed for accuracy.[122]

- An employee of leading debt buyer Portfolio Recovery Associates testified in one trial that he signed as many as 200 affidavits a day. Portfolio has long said that its affidavits are produced in accordance with a “very rigorous set of policies and procedures,” but a 2010 investigation revealed that the company had filed thousands of lawsuits that included affidavits supposedly “signed” by a woman who had been dead since 1995.[123]

- In a sworn deposition connected to a civil lawsuit, an employee of nationwide debt buyer CACH acknowledged that he signed affidavits in support of CACH lawsuits simply by comparing one line of data on a computer screen against the information contained in the lawsuit. The plaintiffs’ attorney asked the man, “So, if you see on the screen that the moon is made of green cheese, you trust that CACH has investigated that and has determined that in fact, the moon is made of green cheese.” He replied, “Yes.”[124]

Critics and some law enforcement and regulatory officials call this “robo-signing,” the computerized mass production of affidavits that the affiant has no real evidentiary basis to believe are accurate.

Some debt buyers counter that none of this is any different than what happens when a bank, as original creditor, sues a consumer over a delinquent credit card debt. As one company official put it, “Is it any different, then, when a bank sues? ... The records coming out of the banks are computerized [too].”[125] To the extent that this comparison holds true, it does not necessarily tend to legitimize debt buyers’ affidavit practices. In July 2015, the CFPB, 47 state attorneys general, and the District of Columbia found that JP Morgan Chase had filed more than 528,000 debt collection lawsuits against consumers “often using robo-signed documents” and that the bank had “systematically failed to prepare, review and execute truthful statements as required by law.”[126]

Similar allegations have targeted the law firms debt buyers retain to litigate their claims. The federal Fair Debt Collections Practices Act requires attorneys to subject collections claims to “meaningful legal review” before filing them, but large collections firms have been accused of numerous lapses and abuses in debt buyer cases. For example:

- In 2014, the CFPB filed a federal lawsuit against a Georgia law firm that files hundreds of thousands of cases every year on behalf of banks, debt buyers, and other creditors. The CFPB suit alleged that one attorney at the firm had signed over 130,000 lawsuits during a two year period. It accused the firm of “operating a debt collection lawsuit mill that uses illegal tactics to intimidate consumers into paying debts they may not owe” and alleged that it “churns out hundreds of thousands of lawsuits that frequently rely on deceptive court filings and faulty or unsubstantiated evidence.”[127]

- In 2012, a group of people sued by debt buyers sought class certification in federal court, alleging that they and 100,000 others were victims of “a scheme to fraudulently obtain default judgments against them” in debt buyer cases. In a ruling that granted class certification, the court described the affidavit signing practices of an attorney with leading New York collections law firm Mel S. Harris & Associates. The court noted that the attorney signed “hundreds of affidavits a week, purportedly based on personal knowledge, purporting to certify that the action has merit, without actually having reviewed any credit agreements, promissory notes, or underlying documents, and, indeed, without even reading what he was signing.”[128]

- In 2014, a lawsuit against New Jersey’s largest collections law firm revealed that attorneys spent an average of just four seconds reviewing individual cases brought by debt buyers and other creditors before signing off on them. The firm was found in breach of the Fair Debt Collection Act’s requirement that collections lawsuits be subject to “meaningful attorney review” before being filed in court.[129]

Sky-High Interest and Questionable Math

Debt buyers are legally entitled to continue accruing interest at contract rates on the debts they purchase up until they secure a court judgment.[130] Since most of the charged-off debt purchased by debt buyers is credit card debt—with rates of compound interest often pegged at well above 25 percent—the scale of a purchased debt can grow by vast proportions between the time it is purchased and the time a debt buyer files a lawsuit. One Maryland study found that debt buyers were able to increase the size of their judgments against consumers by 18.2 percent on average thanks to interest and attorney’s fees.[131]