“Until the Very End”

Politically Motivated Imprisonment in Uzbekistan

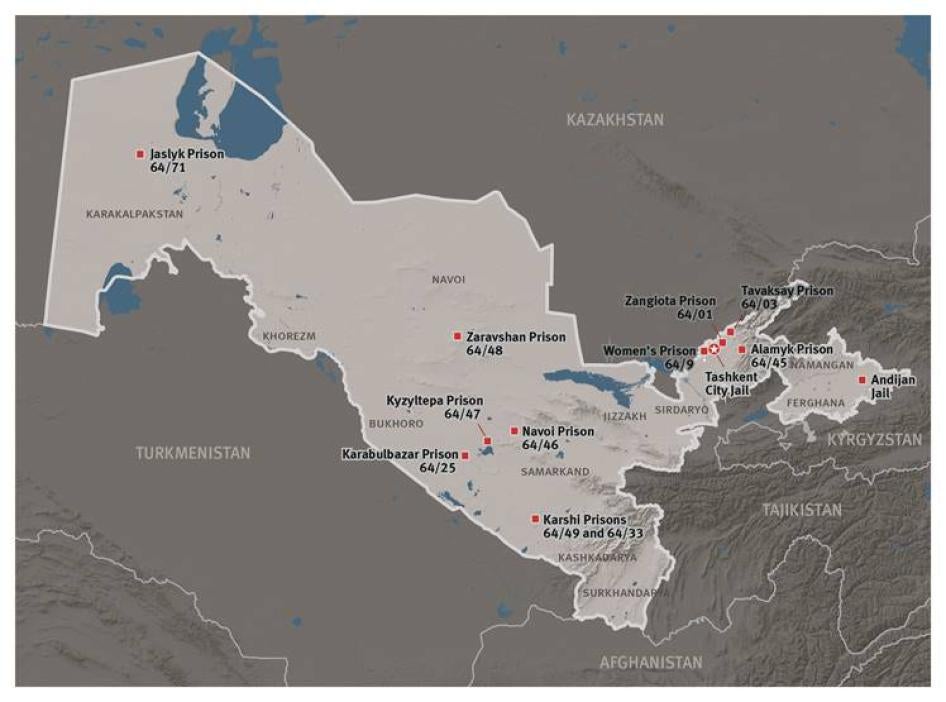

Map of Prisons in Uzbekistan

© 2014 Human Rights Watch

Summary

Agents of Uzbekistan’s feared National Security Services, the “SNB,” kidnapped Muhammad Bekjanov from his apartment in Kiev, Ukraine in 1999. A prominent member of the peaceful political opposition party Erk (Freedom) and editor of one of Uzbekistan’s leading independent newspapers, Bekjanov had fled Tashkent two years earlier in response to a wide-ranging crackdown on Uzbekistan’s political opposition led by the country’s authoritarian president, Islam Karimov. Forcibly returned to Uzbekistan without a hearing, Bekjanov was tried in a closed courtroom amidst allegations that Uzbek authorities had subjected him to electric shocks, beatings with batons, and temporary suffocation. A Tashkent court sentenced him to thirteen years on various charges, including for “threatening the constitutional order.”

At the end of January 2012, just days before Bekjanov’s prison sentence was set to expire, he was given an additional five-year sentence for alleged and unspecified “violations of prison rules.” Along with another jailed Uzbek journalist and opposition activist, Bekjanov has been imprisoned longer than any other reporter in the world. Bekjanov’s alleged crime, like so many other individuals imprisoned on politically motivated charges in Uzbekistan, was his peaceful exercise of fundamental rights, including freedom of speech, association, and assembly. Like other such prisoners, there is no evidence that he has ever committed any act of violence.

Bekjanov is just one of thousands of actual or perceived government opponents and critics the Uzbek government has imprisoned on politically motivated charges to enforce its repressive rule since the early 1990s. The victims span broad categories, including human rights activists, journalists, political opposition activists, religious leaders and believers, cultural figures, artists, entrepreneurs, and others, imprisoned for no other reason than their peaceful exercise of the right to freedom of expression and the government’s identification of them as “enemies of the state.”

Based on more than 150 in-depth interviews with the relatives of such prisoners, their lawyers, human rights activists, scholars, and former Uzbek government officials, this report examines the cases of 34 of Uzbekistan’s most prominent individuals imprisoned on politically motivated charges. The interviewees also included individuals previously imprisoned on such charges. Human Rights Watch documents the egregious abuses they face in custody and calls on the Uzbek government for their immediate and unconditional release.

Fifteen of those whose cases this report documents are rights activists: Azam Farmonov, Mehriniso Hamdamova, Zulhumor Hamdamova, Isroiljon Kholdorov, Nosim Isakov, Gaybullo Jalilov, Nuraddin Jumaniyazov, Matluba Kamilova, Ganikhon Mamatkhanov, Chuyan Mamatkulov, Zafarjon Rahimov, Yuldash Rasulov, Bobomurod Razzokov, Fahriddin Tillaev, and Akzam Turgunov. Five are journalists: Solijon Abdurakhmanov, Muhammad Bekjanov, Gayrat Mikhliboev, Yusuf Ruzimuradov, and Dilmurod Saidov. Four are opposition activists: Murod Juraev, Samandar Kukanov, Kudratbek Rasulov, and Rustam Usmanov. Three are independent religious figures: Ruhiddin Fahriddinov, Hayrullo Hamidov, and Akram Yuldashev. Seven others are various perceived critics of the government or witnesses to the May 13, 2005 Andijan massacre, when Uzbek government forces shot and killed hundreds of mainly peaceful protesters: Dilorom Abdukodirova, Botirbek Eshkuziev, Bahrom Ibragimov, Davron Kabilov, Erkin Musaev, Davron Tojiev, and Ravshanbek Vafoev.

The cases here do not constitute an exhaustive list of all persons convicted on politically motivated charges in Uzbekistan, nor is their selection meant to privilege some cases over others. Instead, these 34 prisoners, who come from every region of the country, shed light on larger trends of political repression in Uzbekistan and on the government’s attempt to suppress a wide range of independent activity that occurs beyond strict state control. At the same time, many cases illustrate the remarkable talent, creativity, and contributions of Uzbekistan’s independent civil society to the country’s civic development, as well as the immense loss that is caused by their continuing imprisonment.

Human Rights Watch research demonstrates that individuals imprisoned on politically motivated charges experience a wide range of human rights abuses. Of the 34 prisoners whose cases this report documents:

This report presents an individual profile of each of the 34 individuals currently imprisoned on politically motivated charges. It highlights the most up-to-date information available on the nature of their work prior to imprisonment, the charges brought against them, reports of torture or ill-treatment in pretrial custody and after conviction, their current whereabouts, and the state of their health.

In a separate section, the report also analyzes by category the extent to which specific abuses that persons imprisoned on politically motivated charges in Uzbekistan experience violate legally binding international standards. This section draws both on the experiences of the 34 prisoners profiled in the report and on interviews with 10 additional individuals who were formerly imprisoned on politically motivated charges, several of whom were released in the last year.

The abuses suffered by those imprisoned on politically motivated charges in Uzbekistan include denial of access to counsel, incommunicado detention, pretrial and post-conviction torture, solitary confinement, the denial of appropriate medical care, and the arbitrary denial of amnesty and extension of prison sentences. These are all serious violations of Uzbekistan’s domestic and international human rights obligations.

Information gathered by Human Rights Watch shows that in many cases the conditions in which persons imprisoned on politically motivated charges are held—overcrowded cells, poor quality and insufficient food and water, and inadequate medical treatment—do not meet international prison standards. Authorities have routinely denied these prisoners treatment for serious medical problems, many of which emerged over the course of prolonged imprisonment. Authorities neither monitor nor remedy the poor prison conditions that may have caused and then exacerbated such health problems in violation of Uzbekistan’s core international human rights obligations. Failure to provide adequate health care or medical treatment to a detainee in prison may contribute to conditions amounting to inhuman or degrading treatment.

Human Rights Watch research indicates that prison officials have wide discretion over who to release under amnesty and sometimes receive instructions from government officials to find justifications to keep persons imprisoned on politically motivated charges incarcerated despite their ostensible eligibility for amnesty.

We also found that prison authorities regularly extend the sentences of those imprisoned on politically motivated charges for so-called “violations of prison rules.” Of 34 current prisoners and 10 former prisoners profiled in this report, at least 14 have had their sentences arbitrarily extended in prison, many more than once—four times in the case of political opposition figure Murod Juraev—often in proceedings that occur without due process.

Uzbekistan’s Criminal Code creates the offense of “disobedience to legitimate orders of administration of institution of execution of penalty” (article 221), often referred to as “violations of prison rules,” on which authorities base the extensions of prisoners’ sentences. However, while the general regulations on the administration of prisons, issued by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, set out a range of behaviors that prisoners are both required to and prohibited from engaging in, they leave wide scope for determining what constitutes a “legitimate order” that should not be disobeyed. The guidelines also are not comprehensive as to what would constitute “violations” for the purpose of article 221. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any publicly available source that alerts prisoners to what all these “violations” might be. The government did not reply to a request for such information and none of the former prisoners, family members of prisoners, or their lawyers could provide Human Rights Watch with any source that sets out or defines the full scope of potential “violations”.

Human Rights Watch’s research indicates that authorities have based multi-year extensions of sentences on minor, insignificant, or absurd alleged infractions, such as “failure to lift a heavy object,” “wearing a white shirt,” “failing to properly place one’s shoes in the corner,” and “failing to properly sweep the cell.” Our interviews with numerous former prisoners, their lawyers, civil society activists, and a senior prison official demonstrate that prison officials interpret broad regulations arbitrarily and in an entirely ad hoc fashion, as a pretext to extend sentences or deny amnesty eligibility and thereby punish those imprisoned on politically motivated charges.

Compounding the above abuses, there is no adequate monitoring of places of detention in Uzbekistan and all individuals imprisoned on politically motivated charges lack access to meaningful complaint mechanisms. These problems have only grown worse since the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was forced to end its visits to detainees and prisoners in April 2013 due to Uzbek government interference in its standard operating procedures. Deplorable incarceration conditions include beatings and torture, solitary confinement, sexual humiliation, exposure to harsh climactic conditions, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases that cause psychological and physical damage to inmates.

Despite the commitments Uzbekistan has made relating to the protection of human rights, including the freedoms of expression, assembly, association, and religion guaranteed in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the prohibition on torture enshrined in the Convention against Torture, it has faced virtually no consequences for its persistent refusal to acknowledge the existence of any individuals imprisoned on politically motivated charges, release them from prison, improve their treatment in custody, or end the cycle of crackdown, arrests, and convictions. Nor has the government paid any real cost for its systematic failure to cooperate with international institutions, including eleven special procedures of the United Nations Human Rights Council, various UN treaty bodies such as the Human Rights Committee and Committee against Torture, or the ICRC.

The governments traditionally viewed as champions of the cause of human rights in Uzbekistan—the United States, the European Union, and several EU member states—have publicly criticized Uzbekistan’s atrocious rights record in past years, most strongly in the immediate aftermath of the Andijan massacre by placing sanctions and restrictions on the Uzbek government. EU and US officials have raised the cases of some of the current and former prisoners described in this report; however, in the past five years they have muted their criticisms and softened their human rights policies with respect to politically motivated imprisonment. Unfortunately, the Uzbek government’s continued failure to release persons convicted on politically motivated grounds has not had a substantial impact on these international actors’ relations with Uzbekistan, on which they continue to rely for its geostrategic importance as a transit route in the context of the war in Afghanistan.

Significantly, when the Uzbek government has faced sustained external pressure, including sanctions, restrictions on military assistance, and other robust, public, specific criticism from its international partners, it has responded by taking incremental steps to improve human rights, including by releasing some individuals imprisoned on politically motivated charges on the eve of key bilateral summits or high-level visits. But in the absence of such pressure, the Uzbek government has defied international calls for human rights improvements, even denying that any problems exist.

In September 2013, for example, during the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Uzbekistan—an examination of Uzbekistan’s human rights record before the UN Human Rights Council—Akmal Saidov, head of the Uzbek delegation, ignored the chorus of recommendations from governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to release immediately and unconditionally Uzbekistan’s political prisoners, even declaring that “there are no political prisoners in Uzbekistan.” Refusing to acknowledge the existence of even a single wrongfully imprisoned individual, Saidov instead pounded his fists on the table, defiantly dismissing the recommendations as based on “misinformation and lies” designed by “politically motivated” NGOs solely to tarnish Uzbekistan’s reputation.

Despite the Uzbek government’s resistance to acknowledge the problem, international pressure can be extremely effective in securing the release of persons imprisoned on politically motivated charges. The findings of this report should remind Uzbekistan’s international partners, including members of the UN Human Rights Council, the US and the EU, and other concerned governments, regional bodies, and international financial institutions of the urgent need to focus on the crisis of politically motivated imprisonment in Uzbekistan and to redouble efforts to secure these and other wrongfully detained individuals’ immediate and unconditional release.

Human Rights Watch strongly believes that the Uzbek government’s continued refusal to release wrongfully imprisoned individuals and lack of any meaningful progress on human rights for more than a decade should trigger in key capitals such as Washington, Brussels, Berlin, and London and at the UN Human Rights Council an assessment of their current strategies for pursuing improvements in Uzbekistan. Given president Islam Karimov’s long record of defying calls to implement meaningful reform, years after Western governments had eased sanctions on the country as a way to encourage reform, Uzbekistan’s international partners should convey a clear and consistent message to Tashkent, both in public and in private, about the urgent need for measureable, concrete steps, including the release of all those imprisoned on politically motivated charges, in addition to steps to address other serious human rights violations. They should also publicly acknowledge Tashkent’s systematic retrenchment on rights and be ready to follow through with meaningful policy consequences, some which Human Rights Watch outlines below, should the Uzbek government continue to commit widespread human rights abuses.

Without a fundamental shift in approach in Tashkent and with absent sustained, robust, and public international pressure, the atrocious situation in Uzbekistan will continue and the suffering of Muhammad Bekjanov, Yusuf Ruzimuradov, Murod Juraev, Samandar Kukanov, Dilorom Abdukodirova, their families, the others profiled in this report, and countless others, is sure to get worse.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Uzbekistan

- Immediately and unconditionally release all persons whose cases are detailed in this report and all other prisoners held for peaceful expression of their political views, civil society activism, journalistic activity, or religious views. To the extent that any such individuals are also alleged to have engaged in acts of violence, they should be granted a new and fair trial according to international standards.

- Take immediate steps to eliminate torture and ill-treatment in pretrial detention and penal facilities, including by ensuring unhindered access to counsel at all stages of investigations, ensuring prompt access to appropriate medical care and re-establishing the independent monitoring of prisons.

- Provide families of all prisoners with full information regarding the location and current health conditions of their relatives. Rigorously investigate all allegations of intimidation or reprisals against family members and prisoners who communicate with journalists, human rights defenders, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

- Investigate and hold to account all officials, security service personnel, and penal system staff alleged to have tortured or ill-treated prisoners and detainees or denied requests for medical care.

- Comply with the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture, which requires Uzbekistan to permit visits by the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (SPT) and to establish an independent national preventive mechanism for the prevention of torture at the domestic level.

- Immediately and fully implement the November 2013 recommendations of the UN Committee against Torture and the February 2003 recommendations issued by the UN special rapporteur on torture following his visit to Uzbekistan in 2002, including the immediate closure of Jaslyk prison 64/71.

- Approve the pending requests by 11 UN special procedures to visit Uzbekistan, including the UN special rapporteur on torture; allow unimpeded independent monitoring of prisons by the International Committee of the Red Cross and other independent monitors.

- Cease the practice of arbitrarily exempting prisoners held on politically motivated charges who qualify for amnesty from annual amnesty declarations and of arbitrarily lengthening prison sentences for minor offences or “violations of prison rules” under article 221 of the criminal code on “disobedience to the terms of punishment.”

- Clarify and bring into line with international standards overbroad criminal articles, such as article 158 on “threatening the president,” article 159 on “threatening the constitutional order,” and article 244 on “forming, leading, or membership in an extremist, fundamentalist, or otherwise banned organization,” which are frequently manipulated to target people expressing their legitimate rights to the freedoms of expression, speech, or religion.

To the European Union, the United States, the United Nations Human Rights Council, and Other International Partners of Uzbekistan

- In the capitals of Uzbekistan’s international partners, given Uzbekistan’s persistent failure to meet the human rights demands articulated in various pieces of US legislation and in joint statements by EU foreign ministers, the US, EU, and EU member states should urgently take up the human rights situation in Uzbekistan with a view to devising an appropriate policy response.

- Set a timeline for the Uzbek government to address longstanding human rights violations, including by releasing persons imprisoned on politically motivated charges, and consider the specific policy consequences that would follow should it not, such as instituting targeted restrictive measures against Uzbek government entities and individuals responsible for grave human rights violations in the country. Such measures should include imposing visa bans and asset freezes with respect to individuals responsible for the use of politically motivated imprisonment, the torture or ill-treatment of prisoners, including the denial of appropriate medical care and arbitrary extension of sentences, and the repression and harassment of independent civil society.

- At the UN Human Rights Council, given the Uzbek government’s longstanding and systematic failure to cooperate with UN human rights bodies, including non-implementation of recommendations by treaty bodies and special procedures and refusal of access despite the latters’ repeated requests, members of the council should support the establishment of a country-specific mechanism in the form of a special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Uzbekistan.

- When visiting Uzbekistan, foreign officials should insist on meeting individually in prison with imprisoned rights activists, journalists, political opposition figures, religious figures, and other persons imprisoned on politically motivated charges and with their relatives to solicit their views and show support for their freedom and courageous and important work.

- Convey in public diplomacy and in private settings that the Uzbek government should demonstrate a commitment to human rights by allowing civil society to function without undue interference.

- In pursuing any dialogue with the Uzbek authorities, whether on economic development, trade, or human rights, concerned governments, regional bodies, and international institutions should consult with civil society activists, particularly with Uzbek human rights activists, on an ongoing basis in order to ensure that policies reflect and address their concerns.

- The release of persons imprisoned on politically motivated charges and other human rights abuses should be explicitly tied to any engagement with the Uzbek government over the sale or provision of military assistance.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch has continuously monitored the human rights situation in Uzbekistan, including the situation for human rights activists, journalists, peaceful opposition activists, independent Muslims, and others imprisoned on politically motivated charges since Uzbekistan gained its independence in 1991. This report is based on more than 150in-depth interviews with human rights activists, journalists, lawyers, former political prisoners, family members of current prisoners, members of unregistered political and religious groups, and other Uzbek citizens between October 2010 and July 2014. The report also draws on some Human Rights Watch interviews and publications from earlier periods. Some interviews were conducted in person during a mission to Uzbekistan from October to December 2010. Others were conducted subsequently by phone with individuals inside Uzbekistan. Interviews were also conducted in person and by phone with individuals in other countries, including in Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Ireland, France, and the United States, where formerly imprisoned activists, relatives of current prisoners, their lawyers, and other activists now reside.

Human Rights Watch was able to obtain copies of dozens of documents, including indictments of persons convicted on politically motivated charges and court judgments. Human Rights Watch acquired these from family members, unofficial civil society groups, and local rights defenders. The documents, which help to corroborate the patterns of abuse established by the accounts of abuse presented in this report, are on file with Human Rights Watch. In addition, we conducted an in-depth review of Uzbekistan’s laws, which provide the legal underpinnings for criminalizing dissent. Finally, we researched press accounts— both from the state-sponsored media and from independent (and thus illegal) media—as well as reports produced by local groups and international bodies such as the United Nations.

Human Rights Watch has researched the cases of some of the individuals profiled in this report for many years. That research included interviewing victims and witnesses to abuses, speaking with the prisoners’ lawyers, and monitoring other media reports about their conditions in prison. Other cases were identified by our close colleague human rights organizations in and outside of Uzbekistan, including the Association for Human Rights in Central Asia, Memorial, the Fiery Hearts Club, the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan, the Human Rights Alliance, the Initiative Group of Independent Human Rights Defenders, Frontline, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the International Federation for Human Rights, and Amnesty International. The contribution of these groups to this research has been invaluable.

Interviews were conducted in English and in Russian by researchers who are fluent in both languages. Some interviews were conducted in Uzbek, during which a translator for Human Rights Watch (a native speaker of Uzbek) translated into English and Russian. Researchers explained to each interviewee the purpose of the interview and how the information gathered would be used. No compensation was offered or paid for any interview.

Human Rights Watch carried out the research for this report in the face of the Uzbek government’s aggressive efforts to prevent Uzbeks and others from documenting rights abuses in the country or sharing information with the outside world. Nearly all prisoners’ trials are closed to independent observers and foreign diplomats, and individuals prosecuted or imprisoned are consistently denied documentation of their cases.

In July 2014 Human Rights Watch requested meetings with the Uzbek government to discuss and obtain their response to the findings documented in this report, directing information requests to Uzbekistan’s minister of internal affairs, prosecutor general, minister of justice, minister of foreign affairs, ombudsperson for human rights, and the National Human Rights Center, a government institution. We also requested permission to visit Uzbekistan, in hopes that the government would break with its practice of denying international human rights delegations access to the country. At the time this report went to press, Uzbek officials had not responded to any of these requests.

To protect their security, all individuals with whom Human Rights Watch spoke were given the option to remain anonymous in the report, to exclude information that might reveal their identities, or to leave their stories out of the report altogether. Where in-person or telephone interviews in Uzbekistan are cited in the report, some names, dates, and locations of sources have been omitted. While most interviewees’ real names are used, others’ identities have been withheld due to concern for their security or at their own request. These interviewees have been assigned a pseudonym consisting of a randomly chosen first name and a last initial that is the same as the first letter of the first name (for example, “Alisher A.”). There is no continuity between pseudonyms used in this report and those used in other Human Rights Watch reports on Uzbekistan.

I. Politically Motivated Imprisonment in Context:

25 Years of Repression

Political repression, including the arrest, torture, and imprisonment of actual or perceived government opponents, has been a constant feature of life in Uzbekistan since Islam Karimov first became the Communist Party secretary of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in 1989 and following independence when he became the country’s president.[1] While the denial of fundamental freedoms over the past two decades has been unrelenting, the government has pursued campaigns of persecution in waves.

These campaigns of repression can be broken down into roughly four periods: the crackdown on the political opposition (1992-1997); the persecution of independent Muslims (1997-present); the May 13, 2005 Andijan massacre and its aftermath (2005-2007); and the period since 2008, when authorities continued to persecute earlier targets but also focused on new perceived critics, including followers of the late Turkish theologian Said Nursi and those suspected of affiliations with Western and other governments. The campaigns have not been mutually exclusive but have overlapped with and reinforced one another.

Dismantling the Political Opposition (1992-1997)

Beginning in 1992, authorities waged a campaign to eradicate political opposition. The campaign took the form of politically motivated arrests, beatings, and harassment, primarily targeting leading members of the secular political groups opposed to President Karimov’s party, the Uzbekistan Liberal Democratic Party. These groups included the Popular Movement Birlik (Unity), the Birlik Party, the Democratic Party Erk (Freedom/Will), the Islamic Renaissance Party, Adolat (Justice), and the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan (HRSU), which first operated as a political party and later grew to become a human rights group.[2]

Some opposition figures were jailed or blacklisted; others disappeared, were beaten, or were forced to flee the country.[3] Members of the Uzbek parliament who spoke out against Karimov’s consolidation of power, such as Samandar Kukanov, Murod Juraev, and Shohruh Ruzimuradov, faced prosecution and imprisonment.[4] Uzbekistan’s former vice president, Shukrullo Mirsaidov, who resigned in September 1992 after warning in an open letter that “democracy and a policy of openness [were] being replaced by an authoritarian regime,” survived a car bombing in 1992 and then was severely beaten along with his son several weeks later. Mirsaidov claimed officers of the National Security Service (SNB) followed him for several days before beating him up.[5]

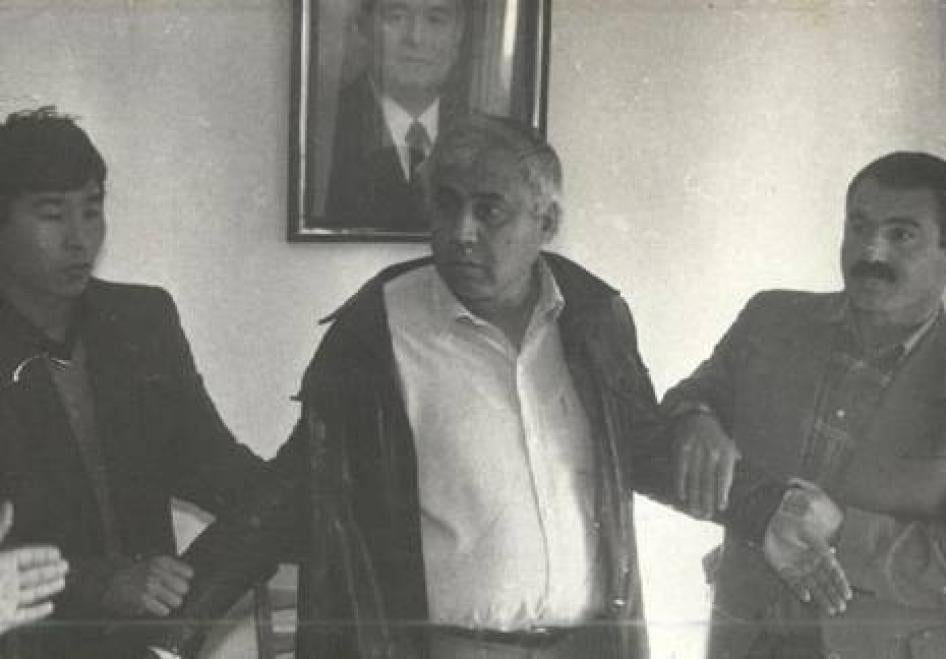

Opposition activist and parliamentary deputy Meli Kobilov photographed while being detained by Uzbekistan’s secret police in Tashkent in 1993. © 1993 Bahtiyor Hamraev

Under extreme pressure, opposition party structures largely

disintegrated and organized political activity lapsed.[6]

In January 1993 Uzbekistan’s Supreme Court ordered Birlik closed

for three months. Authorities sealed Erk’s headquarters and

confiscated its property in 1992, suspending its activities in early 1993. By

April that year, authorities opened a criminal case against Erk’s

chairman, the poet Muhammad Solih, who subsequently fled into exile.[7]

The persecution and imprisonment of individuals affiliated with these now

banned parties and movements continues through the present.[8]

Persecution of Independent Muslims (1997-present)

In the mid-1990 Karimov’s repression quickly spread to the suppression of independent religious expression.[9] The government justified the tightening of control on independent Islam as an effort to prevent the chaos that was gripping neighboring Tajikistan, which was in the midst of a civil war.[10] In 1998, in the name of preventing extremism, Uzbekistan adopted the region’s most restrictive religion laws. Following the events of September 11, 2001, the government framed its persecution of religious Muslims in the context of the global campaign against terrorism.[11]

The government aimed to eliminate a perceived threat of Islamic fundamentalism and extremism by arbitrarily detaining and imprisoning thousands of Muslims and key independent religious leaders who practiced their religion outside strict state control.[12] Independent religious leaders’ acts of what the government called insubordination included a failure to heed the government’s ban on loudspeakers to call people to prayer, failure to praise the president during sermons, open discussion of the benefits of an Islamic state, and refusal to inform on congregation members to the SNB. Inappropriately labeling many religious leaders as Wahhabis, authorities arrested anyone with close or even casual connection to them.[13] Those arrested included members of congregations, including those who had occasionally attended services, the imams’ students, mosque employees, and their relatives.[14] Any observant Muslim who engaged in private prayer, studied or proselytized Islam, shunned alcohol, prayed five times per day, observed religious holidays, learned Arabic to study the Koran, or wore beards or headscarves could be labelled as an extremist.[15] By the end of 2003, according to Memorial, the government had already imprisoned at least 5,900 persons on political or religious grounds, many of whom were adherents of Hizb ut-Tahrir (Party of Liberation). The government labels Hizb ut-Tahrir’s teachings in favor of an Islamic state as extremist but has not produced credible evidence that its members have engaged in or espoused violence.[16] The government’s campaign against independent Muslims and various Islamic groups continues with hundreds of new arrests each year.

Andijan and its Aftermath

On May 13, 2005, government forces shot and killed hundreds of largely unarmed protesters in Andijan to suppress mass demonstrations on the city’s main square that included up to 10,000 people.[17] Authorities sought to justify the violent response to the protests by casting the events in the context of terrorism and claimed that all of the dead were killed by gunmen among the protesters. The government propagated the view that the protest’s organizers were Islamic fanatics and militants who sought to overthrow the government.[18] Extensive Human Rights Watch research found no evidence that the protesters or the gunmen had an Islamist agenda.[19]

The tragedy marked a further turning point in government repression, which resulted in the European Union and the United States imposing sanctions on Uzbekistan and calling on Tashkent to allow an international independent investigation, demands that President Karimov proudly defied. In the wake of the Andijan massacre the Uzbek government unleashed an unprecedented crackdown on civil society, pursuing and prosecuting anyone believed to have either participated in or witnessed the events. The string of criminal cases against witnesses and victims of the events included numerous human rights activists and journalists, including Azam Farmonov, Isroiljon Kholdorov, and Nosim Isakov, all of whom remain imprisoned.

Searching for New Enemies

In the years since the Andijan massacre, authorities have continued to persecute human rights groups, activists, journalists, independent lawyers, and independent Muslims, dismantling Uzbekistan’s civil society and perpetuating a climate of fear for the few that continue to work in the country. But authorities have also added new targets among various segments of the population, increasingly relying on a narrative that Western or foreign powers and their internal agents are attempting to import alien social, cultural, or religious phenomena or destabilize the country.

For example, in 2009, amid worsening relations with Turkey over Ankara’s unwillingness to extradite opposition leader Muhammad Solih, authorities launched a round of arrests against followers of Turkish-Kurdish theologian Said Nursi (Nurchilar in Uzbek) and former students of prestigious Turkish lycées that had been founded by Fethullah Gulen in the early 1990s across Central Asia. The government also imprisoned alleged spies among Uzbek citizens working in international organizations or for foreign embassies.[20] The authorities imprisoned other journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens for raising other politically sensitive topics such as corruption, ecological problems, and the legal status of the autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan.[21]

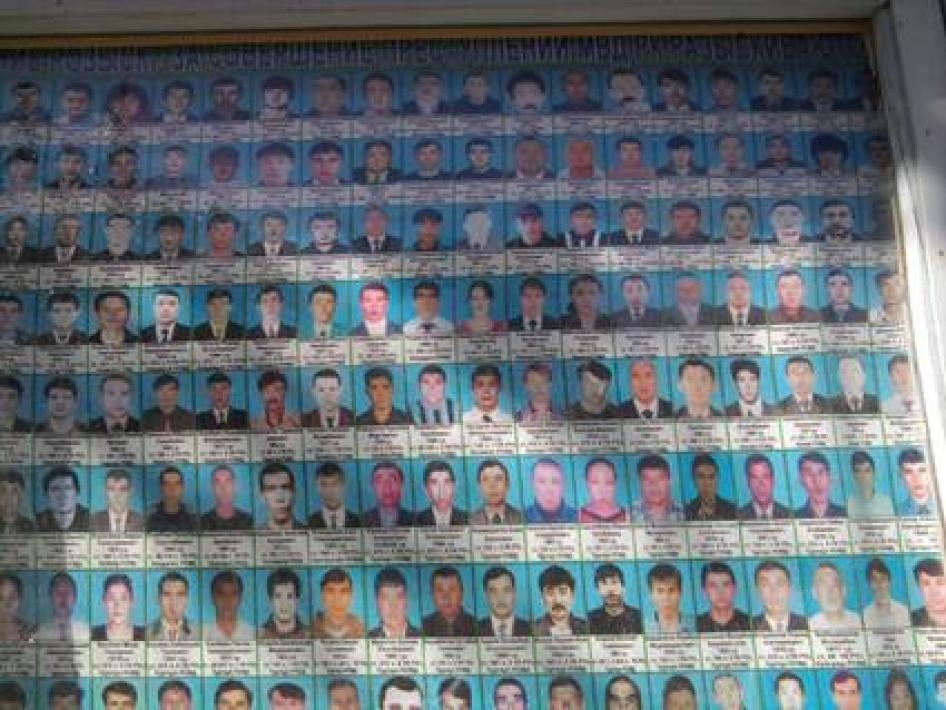

A poster in Nukus, Karakalpakstan in northwestern Uzbekistan in 2013 shows dozens of persons wanted on charges of “threatening the constitutional order.” © 2013 Private

How Many People Are Imprisoned on Politically Motivated Charges?

This report uses the term “politically motivated” to describe the charges, prosecution, and imprisonment of a variety of human rights activists, political opposition figures, journalists, religious believers and leaders, ethnic minority activists, perceived government critics, and others. As the evidence presented in this report shows, these individuals’ nonviolent expression of political opinion, or opinion on politically sensitive issues, in various formats was the catalyst for their prosecution by government authorities.

In addition to rights activists, political opposition figures, journalists, religious figures, and other perceived government critics, there are many individuals prosecuted for the legitimate exercise of civil and political rights (such as freedoms of thought, expression, and assembly) using provisions in Uzbekistan’s criminal code such as “anti-constitutional activity” (article 159), participation in “banned religious, extremist” groups, or possession of “banned literature” (articles 216, 242, and 244), statutes which contain provisions so vague and overbroad that they are wholly incompatible with international human rights norms.

The 34 current and 10 former prisoners whose cases are documented in this report therefore represent only a fraction of the thousands of persons in Uzbekistan whose imprisonment is politically motivated. Establishing the total number of such prisoners in the country is challenging for many reasons, including the fact that Uzbekistan has become virtually closed to independent scrutiny since the Andijan massacre of 2005, does not allow local or international rights groups to operate in the country, and does not make publicly available any information on the overall number or location of prisoners convicted on various charges.

A prisoner at an unidentified prison in Uzbekistan. © date unknown, Fiery Hearts Club

Another barrier to determining a total number is the fact that the government’s campaign to imprison hundreds of individuals, mostly Muslims but also some Christians, on vague, overbroad, and ill-defined charges of so-called “religious extremism” each year is ongoing. In fact, during the writing of this report between September 2013 and July 2014, authorities arrested and convicted at least 6 additional rights activists and political activists and imprisoned well over 100 religious believers from across Uzbekistan.[22]

In 2004 Human Rights Watch found that the government’s campaign of religious persecution had already resulted in the arrest, torture, and incarceration of an estimated 7,000 people.[23] Memorial, a leading Russian human rights organization, which has monitored politically motivated imprisonment in Uzbekistan for many years, estimates that there are now approximately 10,000 “political prisoners” in the country currently imprisoned on charges of religious extremism and other related so-called “anti-state” crimes.[24] In July 2014 the Tashkent-based Initiative Group of Independent Human Rights Defenders, led by rights activist Surat Ikramov, estimated the total number to be closer to 12,000 persons imprisoned on such charges, with over 200 newly convicted in 2013 alone.[25] Ikramov noted the length of sentences handed to prisoners convicted on such crimes and the authorities’ practice, especially since the Andijan massacre, of finding various pretexts to prolong such prisoners’ incarceration by substantial numbers of years.

II. Profiles of Individuals Imprisoned on Politically Motivated Charges

I am at peace with the life I have lived. The life I still have left holds no interest for me any longer! If by chance or by destiny I die in this place, please do as I asked. Do not bury my body in Tashkent, but in Bulungur, next to my beloved Barno and Ruhshona!!!

—Imprisoned journalist Dilmurod Saidov, who suffers from tuberculosis, speaking of his late wife and daughter during a prison visit with his brother in 2014

This section profiles 34 of Uzbekistan’s most prominent individuals currently in prison on politically motivated charges and sets out the urgent need for their immediate and unconditional release. The profiles contain the most up-to-date information known about the prisoners’ activities prior to imprisonment, the nature of the charges brought against them, reports of due process violations and torture in pretrial custody and after conviction, and their current whereabouts and conditions in prison.

The various, sometimes overlapping, categories of prisoners illustrate that the government does not only imprison opposition activists, rights defenders, or journalists but will target anyone they perceive as government critics from any sphere of Uzbekistan’s society, including religious communities, entrepreneurs, cultural figures, or even professionals who work in international organizations. At the same time, the profiles of these individuals show the remarkable contributions, talent, and creativity of Uzbekistan’s diverse civil society despite constant pressure and intimidation by authorities.

Human Rights Activists

Dear Mr. Minister Inoyatov,

Is it really that difficult to find justice in this country?! … I thought the Stalinist period had long passed, no?! If one of your [prison] officials struck my husband, who will answer for this? Or does the law not apply to prisoners in this country?

—Public letter of Dilorom Mamanova, wife of imprisoned rights activist Chuyan Mamatkulov, to the head of Uzbekistan’s National Security Services, Rustam Inoyatov, after learning her husband had been beaten in prison after complaining about the lack of adequate medical care, July 2, 2014

Uzbekistan’s rights activists face the constant threat of severe government reprisal, including imprisonment, torture, harassment, and other forms of pressure. The government routinely interferes in the activities of both domestic and international rights groups, making it nearly impossible for them to carry out their work. This includes: preventing groups from gaining registration, making it illegal for them to accept any kind of grants or other assistance of funding; denying activists exit visas to prevent them from participating in trainings or international conferences; placing activists under surveillance; and frequently subjecting activists to beatings, arbitrary detention and house arrest. Authorities also block international rights groups, including Human Rights Watch, from operating in Uzbekistan and have aggressively pursued rights activists living in exile.

International Standards on the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

The international community has recognized the importance of protecting human rights defenders and has established a set of standards for doing so. The UN Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms explicitly recognizes the rights of human rights defenders to associate, disseminate information, and seek the realization of human rights through criticizing governments and advocating for change.[26] Moreover, the declaration requires states to protect human rights defenders from retaliation and violence related to their work and to promote human rights through enacting legislation. A UN special rapporteur has a mandate to help states give effect to the declaration and investigate alleged violations by governments and non-state actors.[27]

While not directly binding on Uzbekistan, the Council of Europe has also emphasized its commitment to protecting the work of human rights defenders by issuing a 2008 declaration calling for the commissioner for human rights to intervene when necessary to protect human rights defenders and calling on such institutions as the European Court of Human Rights to pay close attention to their plight.[28] More recently, in June 2014, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), of which Uzbekistan is a member, adopted “Guidelines on the Protection of Human Rights Defenders,” which, among other areas, emphasizes,

States should not subject human rights defenders to arbitrary deprivation of liberty because of their engagement in human rights activity.… Human rights defenders arbitrarily detained should be immediately released.… Human rights defenders deprived of their liberty must always be treated with respect for and in accordance with international standards … [and] should not be singled out for selective treatment to punish them for or discourage them from their human rights work.[29]

Taken together, these standards express the strong interest of regional and international bodies in ensuring that human rights defenders are able to carry out their work safely and without interference, which is not the case in Uzbekistan. At time of writing, the Uzbek government holds in prison at least 15 human rights activists on wrongful charges and has imprisoned or brought charges against hundreds of others for no reason other than their legitimate human rights work.

Azam Farmonov

Born: 1979 Arrested: April 29, 2006 Charges: Extortion Sentenced: June 15, 2006; 9 years © Tolib Yakubov |

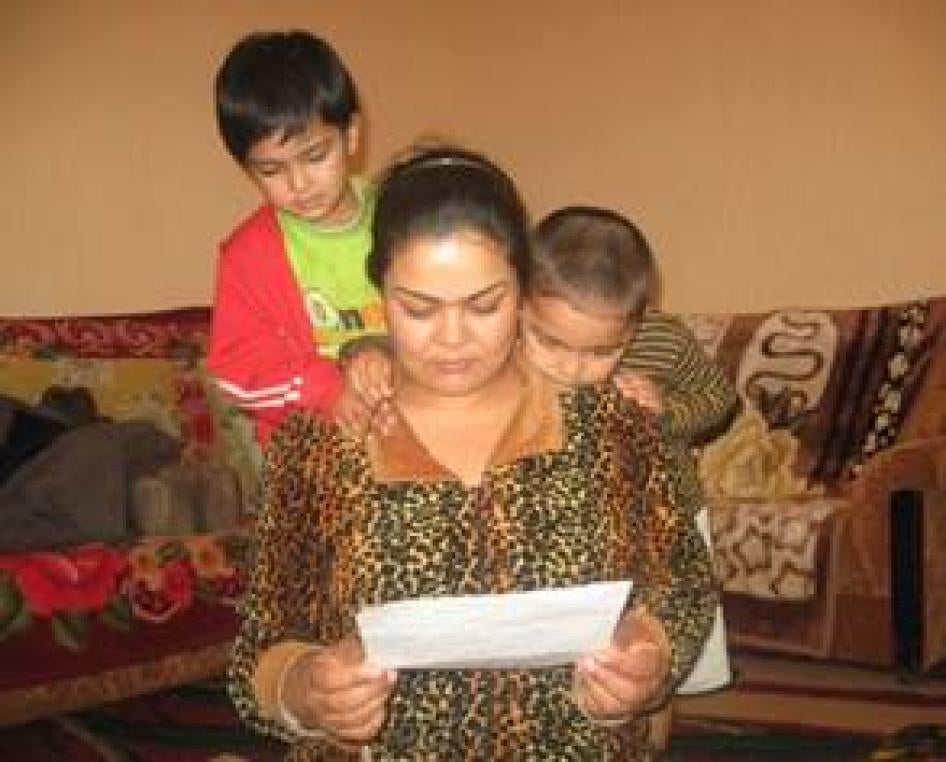

Azam Farmonov, 34, is a father of two children and was chairperson of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan (HRSU) in Gulistan, Syrdaryo province. He monitored violations of social and economic rights with a particular emphasis on the rights of farmers and people with disabilities.[30] He also defended them in court as a lay public defender. He was arrested on April 29, 2006 alongside rights activist Alisher Karamatov on fabricated charges of extortion.[31]

Due process violations marred Farmonov’s pretrial detention and trial. Authorities held both him and Karamatov incommunicado for the first few days of their detention and subjected them to torture. Officers of the National Security Service (SNB) placed sealed gas masks on their heads to simulate suffocation and beat their legs and feet, pressuring them to “confess.”[32] Farmonov told his lawyer that he was beaten on the head with plastic bottles filled with water and that SNB officers threatened to drive nails into his toes and to harm his loved ones.[33] During a search of his home on the day of his arrest, police beat Farmonov’s then-pregnant wife, Ozoda Yakubova.[34]

Farmonov was not represented by independent counsel at his trial.[35] On June 15, 2006, the Yangiyo’l City Court sentenced him to nine years in prison, sending him to Jaslyk prison colony, in northwestern Uzbekistan, which enforces what is termed a “strict” regime even though his sentence specified he should serve his sentence in a “general” regime prison. According to his wife, Farmonov said to her at his sentencing, “I will hold out until the very end.”[36]

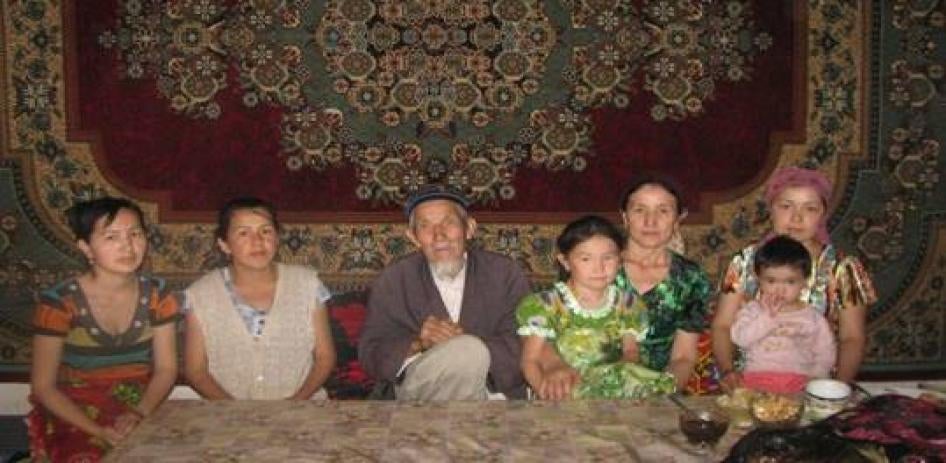

Ozoda Yakubova, wife of imprisoned rights activist Azam Farmonov, together with her children, reads a letter from her husband in Jaslyk prison. © 2012 Bahtiyor Hamraev

Farmonov has reported that authorities tortured him frequently in the first years of his sentence, including stripping him of his overclothing, handcuffing him, and leaving him in an unheated punishment cell for 23 days in January 2008, when temperatures reached approximately -20 C.[37] In 2011 prison guards bound and beat him for refusing to write that he had never been tortured.[38] According to the Association of Christians Against Torture (ACAT)-France, authorities repeatedly transferred him between a prison in Nukus (a city in a neighboring region) and back to Jaslyk when they became aware that representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross representatives planned to make a prison visit.[39]

Farmonov’s relatives and rights defenders believe that his lengthy prison term and abuses he has suffered have caused serious damage to his health.[40] In a July 2013 meeting with his wife, he complained of constant tooth pain and the appearance of a number of hard lumps in various places on his body.[41] Beyond routine check-ups, prison authorities have denied Farmonov’s repeated requests for medical and dental care.[42]

Farmonov’s family told Human Rights Watch that authorities have blocked his eligibility for an early release by charging him with multiple “violations of prison rules,” including “helping prisoners write appeals,” often shortly before the government’s Constitution Day amnesty declaration, at which time eligible prisoners are announced.[43]

Mehriniso and Zulhumor HamdamovaBorn: 1969 and 1960, respectively Arrested: November 5, 2009 Charges: “Threatening the President,” “threatening the constitutional order,” “forming, leading, or membership in an extremist, fundamentalist, or otherwise banned organization,” and “holding unsanctioned religious gatherings” Sentenced: April 12, 2010; 6.5-7 years |

Mehriniso Hamdamova, 45, and Zulhumor Hamdamova, 54, are sisters from the city of Karshi, in the southern province of Kashkadarya, and members of HRSU. Zulhumor is a mother of four children. Mehriniso received a religious education and worked at Karshi’s Kuk Gumbaz mosque, where she was responsible for coordinating the mosque’s outreach with women and youth.[44] According to fellow HRSU members, she and her sister took an active role in civil society, participating in demonstrations against the persecution of independent Muslims. According to an HRSU leader, the sisters were effective because of their ability to gather testimony on abuses from religious women who would not communicate with men.[45]

On November 5, 2009, police arrested them with their relative and fellow HRSU member Shahlo Rahmonova and around 30 other women for holding “unsanctioned religious gatherings” in their homes. According to the warrant, the meetings’ purpose was to organize underground religious congregations (jamoats).[46]

According to rights activists, SNB officers ill-treated the sisters and Shahlo Rahmonova in pretrial detention, stripping them naked and threatening them with rape.[47] They were charged with “threatening the President,” “threatening the constitutional order,” and “forming, leading, or membership in an extremist, fundamentalist, or otherwise banned organization.” A relative who attended the trial reported that the accusations were based on the testimony of two witnesses who alleged that the defendants said, “We are returning to the true form of Islam,” and that they were “building a Caliphate.”[48] The defendants, including the sisters, denied the accusations, stating that the case was entirely fabricated.

On April 12, 2010, the Kashkadarya Criminal Court sentenced the sisters and Rahmonova to terms ranging from six and a half to seven years of incarceration.[49]

HRSU leaders, rights defender Surat Ikramov, and other observers suggested that the charges and the severe sentences were in retaliation for the women’s independent religious practice and active rights work, in particular their monitoring of cases brought against people on grounds of religious extremism.[50]

In 2012 Rahmonova was released pursuant to an amnesty, but the Hamdamova sisters remain in prison.[51] Rights activists report that SNB officers have intimidated the sisters’ relatives, warning them not to speak with anyone about their plight.[52] In February 2014 Mehriniso’s relatives told Human Rights Watch and Forum 18, an independent international religious freedom group, that she is gravely ill and in urgent need of an operation to remove an apparent myoma.[53] Both Mehriniso and her sister Zulhumor are currently being held at Zangiota prison 64/1 in Tashkent province.

Isroiljon Kholdorov

Born: August 23, 1951 Kidnapped from Kyrgyzstan: June 10, 2006 Charges: “Threatening the constitutional order,” “unlawful entry or exit into Uzbekistan,” and “preparing or distributing documents that threaten the public order” Sentenced: February 2007; 6 years; extended by 3 years © Association for Human Rights in Central Asia |

Isroiljon Kholdorov, 63, is the former chairperson of the Andijan branch of Ezgulik, the only registered human rights organization in Uzbekistan. He is also a regional Erk party leader and an independent journalist. He is known for exposing police abuse, assisting victims in filing appeals with the authorities and representing them in court, and publishing articles critical of the government.[54]

Following the May 2005 Andijan massacre, Kholdorov spoke to international media about mass graves in and around Andijan, including in the Bogishamol district, which, according to eyewitnesses, authorities had secretly organized.[55]

On October 18, 2005, police searched Kholdorov’s home in Andijan, confiscating books, documents, and letters. The authorities subsequently issued an order forbidding him to leave Uzbekistan. He fled to neighboring Kyrgyzstan, where he applied for refugee status with the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[56] On November 2, 2005, SNB officers opened a criminal case against him for “threatening the constitutional order,” “unlawful entry into or exit from Uzbekistan,” and “preparing or distributing documents that threaten the public order.”[57]

On June 10, 2006, Uzbek security services kidnapped

Kholdorov in the city of Osh, Kyrgyzstan on his way home from the UNHCR office

and forcibly returned him to Uzbekistan.[58]

The circumstances of his kidnapping and treatment in the first months of his

detention are unclear; officials claim that Kholdorov came of his own free will

to the police station in Andijan on September 7, 2006 with a statement

admitting his guilt.[59]

According to Ezgulik, SNB officers held Kholdorov under guard for six

months at an undisclosed, unofficial place of detention with boarded windows.

He was allowed to exit only to use the outhouse, led by a handler and with his

head covered with a sack.[60] In

February 2007 the Andijan Criminal Court convicted him on all counts,

sentencing him to six years in prison, not including time served in pretrial

detention.[61]

Kholdorov has long suffered from serious health problems, including a severe

spinal hernia. According to his family, his health has deteriorated significantly

in prison.[62] On July

15, 2012, with less than a year left on his prison term, prison authorities

sentenced Kholdorov to an additional three years for “violations of

prison rules” for such infractions as “not getting up when

called” and refusing to lift a heavy object when asked to by a prison

guard.[63] Because

such hearings are closed, little is known about the trial on the additional

charges, including whether he had access to a lawyer or a meaningful

opportunity to appeal. Kholdorov’s family fears the authorities will add more

time to his sentence before it expires in 2016.[64]

Nosim IsakovBorn: November 12, 1966 Arrested: October 27, 2005 Charges: “Hooliganism” and extortion Sentenced: December 2005; 8 years; sentence extended for unspecified period |

Nosim Isakov, 47, is a father of three children and a member of HRSU in Jizzakh, central Uzbekistan.[65] He wrote public letters and complaints to officials, including President Karimov, regarding the official abuse of power and corruption in Jizzakh province. In January 2005 Isakov took up the case of Askhad Yakubov, who died allegedly from being tortured in custody by the Jizzakh police.[66]

On October 27, 2005, the head of the SNB branch in Jizzakh summoned Isakov and his wife to the police station, ostensibly to discuss a letter Isakov had written to the president. After separating him from his wife, an investigator asked Isakov if he had come with a lawyer and immediately arrested him without showing a warrant.

Prosecutors charged him with “hooliganism” and extortion, charges that appeared fabricated. His trial was marred by due process violations.[67] The prosecution based the hooliganism charge on the allegation of Isakov’s neighbor, a fifth-grade girl, that he had made a lewd gesture toward her. According to Isakov’s Ezgulik colleague, the extortion charge was based on the testimony of a former classmate who claimed Isakov demanded a television set in exchange for agreeing not to expose corruption on the part of the owners of a local flour mill.

At his trial, which began on December 15, 2005, Isakov maintained his innocence and told the judge that police beat him on the head with a bottle filled with water, causing headaches and hearing loss during pretrial detention, but the judge refused to investigate his allegations.[68]

Gaybullo Jalilov

Born: August 24, 1964 Arrested: June 8, 2009 Charges: “Anti-constitutional activity” and “membership in a banned religious organization” Sentenced: August 4, 2010; 11 years, 1 month, 5 days © Association for Human Rights in Central Asia |

The court sentenced Isakov to eight years in prison. He was to have been released last year, but authorities extended his sentence for unspecified “violations of prison rules” and he continues to serve a prison term in Tavaksay, Tashkent province. According to rights activists, authorities have intimidated his family members over the years, warning them not to make any complaints about Isakov’s imprisonment.[69]

Gaybullo Jalilov, 50, is a human rights activist from Karshi in the southern province of Kashkadarya and the father of two children. A member of HRSU since 2003, he focused on the crackdown on independent Muslims. By the time he was taken into custody on June 8, 2009, he had collected information on over 200 arrests of independent Muslims in the region.[70] Jalilov had severe medical problems prior to prison; he is missing one of his lungs and requires constant medical supervision. His health has worsened since he has been in detention.[71]

On January 18, 2010, the Kashkadarya Criminal Court sentenced Jalilov to nine years in prison on charges of “anti-constitutional activity,” “production and distribution of banned material,” and “membership in a banned religious organization.” Jalilov’s trial violated fair trial standards and he was allegedly tortured in pretrial detention. The prosecution’s case against Jalilov centered on his alleged involvement in an extremist religious group and the preparation of terrorist attacks on a military base. However, it did not introduce any evidence in support of these allegations. The authorities’ search of Jalilov’s home produced no religious literature and no witnesses could recall him ever belonging to an extremist group or calling for violent action against the state.[72] On March 9, 2010, Jalilov’s nine-year sentence was upheld on appeal. Guards brought him to the hearing with a swollen eye, raising the possibility that he had been ill-treated in custody.[73]

Seven months after his original conviction, on August 4, 2010, a court convicted Jalilov again and sentenced him to 11 years, one month, and five days on new charges of “attempting to overthrow the constitutional order of the state.”[74] Authorities never notified his family of the investigation into his case and repeatedly denied their requests to visit him in detention. Upon sentencing, Jalilov was transferred to a prison in Zangiota.[75]

After a two-day visit in January 2011, Jalilov’s relatives told Human Rights Watch that Jalilov had been tortured, including by being beaten with a nightstick to such a degree that he has nearly total hearing loss. They also reported that Jalilov’s lung causes him pain and that he is suffering from a vertebral hernia.[76]

In late 2013 relatives and rights activists reported that Jalilov was in urgent need of medical care.[77] In 2012, without notifying his family, authorities moved him 450 kilometers from Zangiota prison in the northeast to a prison in Navoi, in central Uzbekistan.[78] Since 2013, in spite of his very poor health, prison authorities have made Jalilov work in a prison brick factory. It is also reported that he is not receiving enough food.[79]

Matluba KamilovaBorn: 1960 Arrested: September 6, 2010 Charges: Narcotics possession Sentenced: 11 years |

Matluba Kamilova, 54, is a mother, human rights activist, lawyer, and the former director of a technical college in Angren, Tashkent province. She was known for tackling corruption and assisting citizens to advocate for their rights. Her work led to the opening of two corruption cases against local officials.[80] On September 6, 2010, plainclothes officers who identified themselves as belonging to the SNB arrested her during a traffic stop on her way to work. Shohruhon, Kamilova’s 21-year-old son who was in the vehicle, told an activist that the officers said they found a five-gram bag of heroin, after which they took Kamilova and him into custody, beating them in the process.[81] Police subsequently searched Kamilova’s office where they said they uncovered another four grams of unspecified narcotics.

A few days later officers transferred Kamilova to the Tashkent city jail. A rights activist present at Kamilova’s trial told Human Rights Watch that Kamilova testified that SNB officers took her out of her cell at the jail, where she was forced to listen to the screams of other prisoners being beaten to convince her to confess.[82]

A rights activist who observed Kamilova’s trial and interviewed her son told Human Rights Watch that SNB officers planted the drugs on Kamilova’s person. In addition, officers provided contradictory testimony about the sequence of events during the search of the vehicle, including how and when the drugs were allegedly discovered.[83]

A Tashkent regional court convicted Kamilova on narcotics possession, sentencing her to eleven years in prison. The ruling was upheld on appeal.[84] Few details are known about Kamilova’s current condition or whereabouts in prison, but the narcotics conviction renders her ineligible for amnesty. Kamilova’s relatives said SNB officers have repeatedly threatened them not to speak about the case.[85]

Ganikhon Mamatkhanov

Born: 1951 Arrested: October 12, 2009 Charges: Fraud and attempted bribery Sentenced: November 25, 2009; 5 years; sentence extended for an unspecified period © Abdujalil Boymatov/Human |

Ganikhon Mamatkhanov, 63, the father of five children, was the leader of the local chapter of the International Society for Human Rights of Uzbekistan in his native Fergana province, in eastern Uzbekistan. He advocated for social and economic rights, especially those of farmers subjected to unlawful land confiscation as well as for adults and children forced to harvest cotton by government officials.[86] Before his arrest, Mamatkhanov regularly commented on rights abuses in his native region to the Uzbek service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and criticized the government’s failed socio-economic policies on BBC radio.[87]Several days before his arrest, Mamatkhanov sent an open letter to President Karimov criticizing his agricultural reform program immediately before Karimov was to make a visit to Fergana province.[88]

Police arrested Mamatkhanov on October 12, 2009, under circumstances that appear to have been staged to frame him for fraud and attempted bribery. He later told his son that he suffered two heart attacks in pretrial detention but that his request to the investigator for medical attention was denied.[89] His case was marred by severe procedural violations and witnesses claimed that the investigator instructed them what to say before and after Mamatkhanov’s arrest.[90] On November 25, 2009, a court sentenced him to five years imprisonment and the authorities sent him to a penal colony in the Pskent district of Tashkent province. He suffered a third heart attack during trial.[91]

In January 2010 a court reduced Mamatkhanov’s five-year prison sentence to four and a half years on appeal.[92] Mamatkhanov’s lawyer reported that SNB officers obstructed an appeal by refusing to supply necessary documents and denied him opportunities to meet with Mamatkhanov. Authorities granted him just one meeting with Mamatkhanov throughout the appeal.[93]

In spring 2010, after allegedly violating prison rules at his penal colony, authorities transferred Mamatkhanov to Kyzyltepa prison in Navoi, in central Uzbekistan, more than 700 kilometers from his Fergana home. During a January 2011 family visit, Mamatkhanov complained of heart pain and high blood pressure.[94] Visiting him in July 2013, his wife reported that his condition had further deteriorated, including increased hypertension and difficulty walking. Mamatkhanov requested that she urge rights groups and diplomats to advocate for his release as he fears he will die in prison due to his poor health.[95]

Mamatkhanov was due to have been released on March 10, 2014, but authorities extended his sentence in the same month for unspecified “violations of prison rules” following a closed hearing.[96] According to Mamatkhanov’s son, Jalolidin, and rights activists, authorities informed the family even prior to the hearing that Mamatkhanov’s sentence would be inevitably lengthened and that they should “prepare for him to be moved to a prison in another region.”[97] When Mamatkhanov’s family attempted to visit him, prison officials denied them access. After returning home, they received a letter that he had been tried on March 4, two days before their arrival. The letter stated that a Navoi court had sentenced him to an additional term for “violation of prison rules” but did not state by how many years. “I called the court of the city of Navoi,” said Jalolidin, to obtain information, “but they told me that they do not give information over the phone and asked to visit him in person!”

Mamatkhanov earlier warned authorities would find a justification to lengthen his sentence, as has occurred with others imprisoned on politically motivated charges. Prison officials placed Mamatkhanov in solitary confinement for several days in March 2014 ostensibly for “going to the bathroom on three occasions without asking permission.”[98]

Chuyan Mamatkulov

Born: 1970 Arrested: August 2012 Charges: 12 different charges, including narcotics sale, extortion, kidnapping, religious extremism, and racketeering Sentenced: March 12, 2013; 10 years Imprisoned rights activist Chuyan Mamatkulov photographed with his two children in Kashkadarya province. © 2012 Private |

Chuyan Mamatkulov, 44, is a father, former sergeant in the army, and member of HRSU in Kashkadarya province and has represented citizens in court cases.[99] He has also assisted victims of fraud and written petitions to government bodies.[100] He rose to prominence in the early 2000s after filing several suits against President Karimov alleging his unlawful dismissal from active military service in 2000.[101] He claimed that Karimov, as commander-in-chief, bore responsibility for his wrongful dismissal. Following the dismissal of his lawsuit three times, a Tashkent city court finally accepted the case in 2004, but no trial date was ever set. Mamatkulov’s fearlessness and willingness to criticize President Karimov directly earned him respect among many in civil society and beyond.[102]

Following the 2005 Andijan massacre, authorities pressured Mamatkulov to abandon his public criticism. In December 2012, rights defenders learned that authorities had arrested Mamatkulov in August of that year on 12 different charges, including narcotics sale, extortion, kidnapping, religious extremism, and racketeering.[103] A court convicted Mamatkulov on all counts on March 12, 2013 and sentenced him to 10 years in prison. No observers were allowed to be present at the trial.[104] The number of charges, nature of the accusations, and the fact that the religious organization Mamatkulov was accused of being a member of, Jihodchilar, does not appear to exist, contribute to the appearance of a politically motivated prosecution of a government critic and is consistent with other similar cases.[105]

Mamatkulov is serving his sentence in Navoi.[106]In July 2014 Mamatkulov’s wife told Human Rights Watch that on April 20 a prison captain named Sherali had repeatedly struck Mamatkulov on the head with a rubber truncheon in his office after Mamatkulov had asked to see a dentist.[107] Following the beating, prison authorities placed Mamatkulov in solitary confinement for 24 hours. His wife learned about the beating during a visit with her husband on June 19. At that time she also discovered that Mamatkulov has lost the majority of his teeth and has had problems with his vision since the April 2014 beating.[108]

Karshi-based human rights activists Yuldash Rasulov, 46, and Zafarjon Rahimov, 45, are childhood friends, colleagues, and members of the Kashkadarya province branch of HRSU. Rahimov was a policeman until the early 1990s, when the government purged religious

individuals from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and he was forced to leave his position. He then began working with Yuldash Rasulov as a mechanic at an auto shop, when both became involved with HRSU around 2001.[109]

In the early 2000s, similar to Shahlo Rahmonova and Mehriniso and Zulhumor Hamdamova, Rasulov and Rahimov served as a link between religious Muslims and the secular HRSU. They gathered information about abuses against independent Muslims, focusing on freedom of belief and worship and ill-treatment in custody. Rasulov and Rahimov also expanded the scope of HRSU’s work in Kashkadarya province, arranging meetings with pious Muslims and farmers.[110]

Zafarjon Rahimov and Yuldash Rasulov

Born: 1969 and 1968, respectively Arrested: April 2007 Charges: “Threatening the constitutional order” and “membership in a banned religious organization” Sentenced: 2007; 6 and 10 years, respectively; Rahimov’s sentence was extended for an unspecified period © Association for Human Rights in Central Asia (left), © Tolib Yakubov (right) |

On May 24, 2002, authorities arrested Rasulov on charges of “threatening the constitutional order,” “distributing extremist literature,” and “membership in a criminal organization.” He was held incommunicado for a month after his arrest and stated in court that he had been beaten in pretrial detention.[111] The court convicted Rasulov and sentenced him to seven years in prison, but following sustained pressure from human rights organizations and diplomats, authorities released him seven months later.[112]

After Rasulov’s release in early 2003, he and Rahimov continued their work. In late April 2007, security forces arrested the pair in Karshi on charges that included “threatening the constitutional order” and “membership in a banned religious organization.”[113] Rahimov received a six-year sentence and Rasulov was sentenced to ten years.[114] Human Rights Watch received reports from the Uzbek human rights organization Fiery Hearts Club, who interviewed the men’s families, and rights activists who monitored the trial that both men were tortured during the investigation and after they were convicted.[115]

Rahimov’s sentence was set to expire in October 2013, but he remains in prison colony 64/25 in Karavulbazar in the southern province of Bukhara, leading his colleagues to assume that his sentence has been extended on undisclosed grounds.[116] Rasulov also remains incarcerated.

Bobomurod Razzokov

Born: March 19, 1953 Arrested: July 10, 2013 Charges: human trafficking Sentenced: September 24, 2013; 4 years © Fiery Hearts Club |

Bobomurod Razzokov, 61, is a father of six children, a farmer, a member of the Erk party, and was the head of Ezgulik in Bukhara province.[117] He also worked as a correspondent for foreign media, including Deutsche Welle. With Ezgulik, Razzokov wrote complaints on corruption to the regional administration (hokimiyat), the prosecutor’s office, and the president. In the month before his arrest, Razzokov told media and rights groups that he came under increased pressure from the SNB over his work.

On June 10, 2013, the head of Bukhara’s counterterrorism unit, Alisher Andaev, summoned him for a two-hour interrogation and ordered him to resign from Ezgulik and cease all contact with foreign media. Razzokov said that Andaev told him harm would come to him and his family if he did not stop his work.[118]

Authorities detained Razzokov on July 10, 2013 on human trafficking charges.[119] The charge stemmed from the written complaint of a woman who accused Razzokov of forcing her into the custody of another individual, who pressed her into prostitution. According to Razzokov, the alleged victim approached him several days before his arrest requesting assistance in finding a relative who had gone missing in Russia. Razzokov’s relative claims that the SNB pressured the woman to testify against him.[120] A rights activist who monitored the proceedings and the authorities’ threats against Razzokov prior to his arrest told Human Rights Watch that he believes Razzakov’s prosecution was retaliation for his long record of civil society activism. He observed that the case fits a pattern of pressure against representatives of the Ezgulik human rights group in other regions of Uzbekistan.[121]

On September 24, 2013, the Bukhara Province Criminal Court sentenced Razzokov to four years’ imprisonment.[122] Soon after the conviction, authorities transferred him to a Tavaksay labor colony, more than 600 kilometers to the northeast of his home, to serve out his sentence, where he remains.[123]

Fahriddin Tillaev and Nuraddin Jumaniyazov

Born: August 15, 1971 and October 8, 1948, respectively Arrested: January 2, 2014 Charges: human trafficking Sentenced: March 2014; 8 years, 3 months © Association for Human Rights in Central Asia |

Fahriddin Tillaev, 43, and Nuraddin Jumaniyazov, 66, human rights activists and members of the Erk party, were sentenced in March 2014 to eight years and three months in prison on human trafficking charges.[124] Both Tillaev and Jumaniyazov also became members of Mazlum (“the oppressed”) Human Rights Center in 2003.[125] Since 2005 Tillaev has advocated for workers’ rights in Surkhandarya province in southeastern Uzbekistan.[126] In 2012 he helped found the Union of Independent Trade Unions that protects the rights of labor migrants (mardikorlar), while Jumaniyazov headed its Tashkent chapter.[127]

On December 28, 2013, Tashkent police interrogated Jumaniyazov because two Uzbek citizens, Farhod Pardaev and Erkin Erdanov, apparently alleged that Jumaniyazov and Tillaev arranged their employment in Kazakhstan, where they were mistreated.

Tillaev’s lawyer, Polina Braunberg, told Human Rights Watch that the investigation against the two was marred by serious procedural violations. Police arrested them both on January 2, 2014 and took them to a Tashkent prison but falsified materials to indicate January 4 as the date of arrest.[128] Investigators did not provide Tillaev’s or Jumaniyazov’s lawyers sufficient time to review the evidence in the case, conducting all interrogations, including of the defendants, in a single day before advancing the case to trial.[129] The court completed the trial in just two hours, basing the conviction solely on the testimonies of two witnesses who admitted that they had never seen Tillaev nor had any relationship with him whatsoever.[130]

According to their lawyer, police tortured both Tillaev and Jumaniyazov in pretrial custody.[131] They stuck needles between Tillaev’s fingers and toes, for example, and forced him to stand for hours under a faucet from which water dripped on his head, causing a severe headache. On January 21, 2014, during a meeting with her client Tillaev, Braunberg became convinced that Tillaev had been tortured and petitioned the investigator for a forensic medical examination. The investigator refused to answer her petition until just one day before the next court hearing, at which time the court denied the defense’s request to open an investigation into the torture allegations on the basis that the petition was still being “processed.”[132]To date, no judicial or prison authorities have meaningfully investigated Tillaev’s allegations of torture.

Akzam Turgunov

Born: January 1, 1952 Arrested: July 8, 2008 Charges: extortion Sentenced: October 23, 2008; 10 years © Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan |

On August 1, 2014, Uzbekistan’s Supreme Court rejected the appeal to overturn their convictions. Both Tillaev and Jumaniyazov remain in prison in Navoi.

Akzam Turgunov, 62, is the father of four children, the founder of Mazlum Human Rights Center in Tashkent and was a trial monitor and member of the Erk party.[133] Turgunov was well-known for taking on politically sensitive cases, including religious extremism cases, and also defended Tursinbai Etamuratov, head of HRSU’s office in the autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan in northwestern Uzbekistan.[134] Turgunov earlier served a prison sentence from 1998 to 2000 for his involvement in the Erk party and experienced frequent intimidation and harassment from the authorities in the years after his release.[135] He was arrested again in Tashkent on July 8, 2008 on trumped-up charges of extortion after travelling to Karakalpakstan to assist in the settlement of a child support case.[136]

Serious due process violations plagued Turgunov’s trial, and security officials allegedly tortured him in custody.[137] On July 14, 2008, while he was in the Tashkent office of police investigator Salomat Ibragimov writing a statement, someone poured boiling water down his neck and back, causing him to lose consciousness and burning him severely.[138] Leaked United States State Department documents, which corroborate earlier interviews by Human Rights Watch regarding Turgunov’s torture, suggest that he was tortured in an attempt to extract a confession.[139] Authorities ordered an investigation into Turgunov's torture only after he removed his shirt during a court hearing in Tashkent on September 16, 2008 to show the scars from the burns, which covered a large portion of his back and neck, extending past his waist.[140] A subsequent court-appointed forensic medical examiner concluded that Turgunov’s burns were minor and did not warrant further investigation.[141]

During Turgunov’s trial, a court clerk told observers that “even if BBC would come to this trial, Akzam Turgunov will get a long prison sentence,” suggesting that the outcome of his trial was predetermined.[142] The court sentenced him to 10 years’ imprisonment on October 23, 2008, and authorities transferred him to a location that remained unknown to his family for several months.[143] He is currently at prison colony 64/49 near Karshi.[144]

Turgunov’s family told Human Rights Watch that he has lost significant weight and is in bad health. According to a Tashkent-based rights activist, his condition continues to worsen: he has limited mobility and suffers from a chronic cough, difficulty breathing, and a heart condition.[145] He is forced to work at a prison brick factory and has complained of severe leg pain as a result of this work, for which prison authorities have denied him treatment.[146] In November 2011 the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention issued an opinion calling for Turgunov’s release and stating that his detention by the Uzbek government is arbitrary and in violation of international norms.[147]

Journalists

We fully support our citizens’ desire to freely use the Internet.… I would like to repeat this: we absolutely do not accept the erection of walls and restrictions around the world of information, leading to isolation.

—President Islam Karimov, addressing citizens on Media Workers Day, June 27, 2011[148]