Summary

On a sunny day in January 2010, in the small town of Kuru Karama, Plateau State, a Muslim mother watched helplessly as Christian men bludgeoned and hacked to death her two young children. About the same time, in a nearby village in Fan district, a Fulani pastoralist witnessed farmers from the Berom ethnic group—his neighbors—burn his house and kill his uncle. A year later, Berom residents in Fan district witnessed former Fulani neighbors kill Berom women and children in a murderous night raid.

In April 2011, a Christian man in the northern part of neighboring Kaduna State saw Muslims from nearby villages surround his village and kill two of his Christian neighbors and set fire to their church and homes. That same month, some 200 kilometers to the south, in the town of Zonkwa, a Muslim secondary school student, from the Hausa ethnic group, witnessed her history teacher, a Christian, murder her father.

In each of these cases, the witnesses knew the perpetrators of these crimes, but none of the perpetrators has been brought to justice.

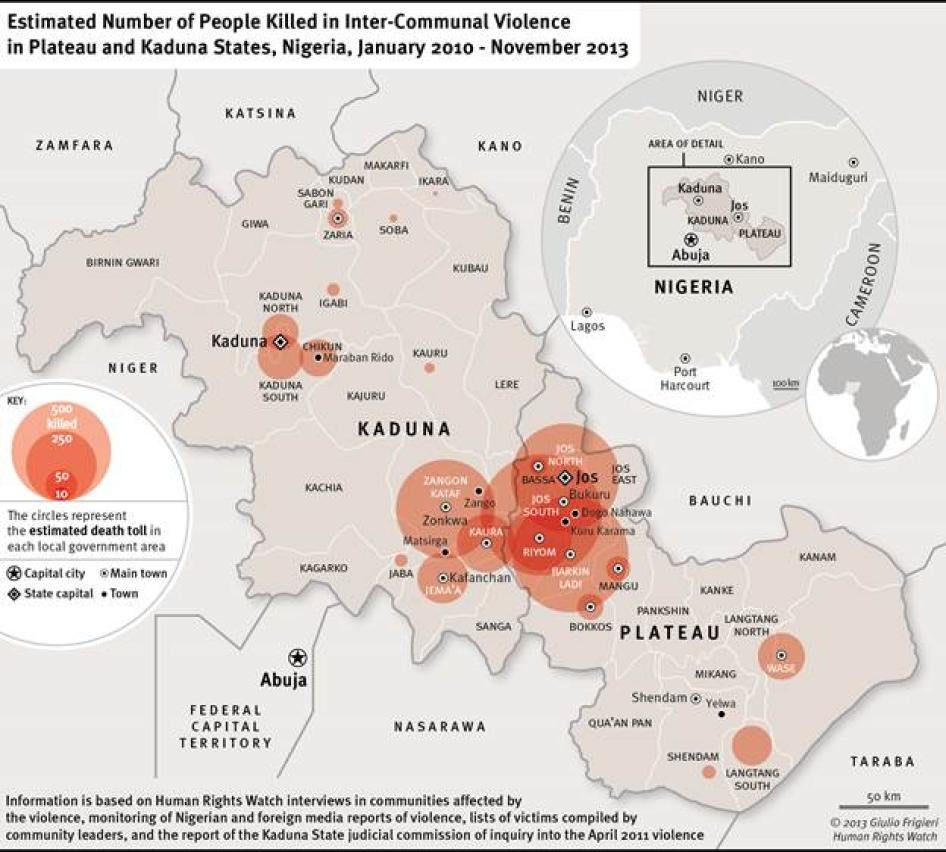

Nigeria’s volatile Middle Belt, an area in central Nigeria that divides the largely Muslim north from the predominantly Christian south, has witnessed horrific internecine violence over the past two decades. Two neighboring states in this region—Plateau and Kaduna—have been worst affected. Since 1992, more than 10,000 people in those two states have died in inter-communal bloodletting; several thousand of those deaths have occurred since 2010 alone. Many of the victims were targeted and killed, often in horrific circumstances, based simply on their ethnic or religious identity. Victims, including children, have been hacked to death, burned alive, or dragged off buses and murdered in tit-for-tat killings. The Nigerian authorities have failed, with rare exception, to break the cycle of violence by bringing to justice the perpetrators of these serious crimes, and horrific attacks in both Plateau and Kaduna have continued.

This report details the major incidents of violence in Plateau and Kaduna states, in particular brutal massacres in 2010 and 2011, and documents how the Nigerian authorities responded to these mass killings. The incidents documented in this report are not simply bygone historical events but remain very present in the lives of the victims and survivors. In the absence of effective remedies through the criminal justice system, similar violence continues to threaten these states, as aggrieved individuals seek retribution for the loss of their loved ones, homes, and livelihoods.

While the root causes driving communal violence in the Middle Belt are varied and often entail longstanding grievances and disputes, they are exacerbated both by divisive state and local government policies that discriminate on ethnic or religious lines and by the failure of authorities to hold to account those responsible for the violence. The report examines the reasons that Nigerian officials have not prosecuted perpetrators and recommends steps the government can and should take to end the pervasive culture and practice of impunity that have helped fuel this violence.

The communal strife in Plateau and Kaduna states has primarily pitted Hausa-Fulani Muslims—the largest and most politically powerful group in northern Nigeria—against smaller predominantly Christian ethnic groups that, together, constitute the majority in the Middle Belt. Members of these Christian groups say they feel threatened by the expanding Hausa-Fulani communities in the region. Some Christian leaders accuse the Hausa-Fulani of trying to impose Islam on the region and point to a history of oppression and violence suffered by non-Muslims in the northern region of the country to back up these concerns. They also accuse Hausa-Fulani in the Middle Belt communities of resorting to violence to achieve these ends.

In Plateau State, state and local government officials have responded to this perceived threat by implementing policies that favor members of predominantly Christian “indigene” groups—those who can trace their ancestry to what are said to be the original inhabitants of an area—and exclude opportunities, such as state and local government employment, to Hausa-Fulani and members of other ethnic groups they deem to be “settlers.”

The situation is more complex in Kaduna State, where the ethnic and religious divisions are more evenly split. In the northern part of the state, Hausa-Fulani hold the majority, and Christians claim they face discrimination, while in the southern part of the state—where numerous predominantly Christian ethnic groups, together, make up the majority—Hausa-Fulani complain that they are treated as perpetual “settlers” and second-class citizens, despite the fact that, in some cases, their families have lived in those communities for multiple generations. The struggle for “ownership”—cultural, religious, and political control—of these areas has been at the heart of much of the inter-communal conflict.

Both sides have accused the other of using extreme violence to achieve their goals, including mass killing and ethnic or sectarian cleansing of communities and neighborhoods. Christian leaders in these states often accuse the Hausa-Fulani of starting the violence, allegations that the Hausa-Fulani leaders usually deny, while Hausa-Fulani point out that far more Muslims have died in mass killings at the hands of the Christians, massacres that Christian leaders invariably dispute.

For this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 180 witnesses and victims of violence in Plateau and Kaduna states, as well as police officers, judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and Christian and Muslim leaders. A Human Rights Watch researcher conducted site visits to the major scenes of violence, sometimes just days after a massacre, collected and analyzed court documents, and attended some of the trials in Federal High Court in Jos.

Human Rights Watch has been reporting on violence in the Middle Belt for more than 12 years, and its human rights investigations during that time also inform this report. Plateau State, as Human Rights Watch has previously reported, suffered recurring bloody episodes of inter-communal violence and mass killing in 2001, 2004, and 2008, which left hundreds of people, in each incident, dead. Following this violence, federal and state authorities took no meaningful steps to address underlying grievances and brought no one to justice for the bloodletting.

With tensions still simmering after the 2008 violence, the veneer of calm was shattered in January 2010 in renewed sectarian clashes in Jos, the capital of Plateau State. The violence led to massacres of Muslims in rural communities, south of Jos, including ethnic pogroms against rural Fulani farmers and pastoralists, which left hundreds dead. The federal government stepped in for the first time and prosecuted some of the suspects, but in most cases, including the largest massacres, no one was brought to justice. In the three and a half years since then, Plateau State has been racked by numerous episodes of violence, including dozens of horrific massacres in predominantly Christian villages to the south of Jos, which have left hundreds more dead.

In neighboring Kaduna State, bloody ethnic and sectarian violence in 1992, 2000, and 2002 left hundreds or more dead in each incident. As in Plateau State, no one was brought to justice, with the exception of prosecutions under a special tribunal during military rule following the 1992 violence. Then, in 2011, following the election of President Goodluck Jonathan—a Christian from southern Nigeria—Hausa-Fulani opposition party supporters rioted across northern Nigeria, attacking properties of ruling party officials and Christians and burning hundreds of churches. The violence then spread to the southern part of Kaduna State, where Christians killed hundreds of Muslims, including rural Fulani farmers and pastoralists.

Community leaders and witnesses in many cases filed complaints with the police in Kaduna State, but no one was prosecuted for these serious crimes. Since then, in a pattern similar to Plateau State, there have been several dozen attacks on largely Christian rural communities in southern Kaduna State, allegedly by armed Fulani attackers, as the cycle of violence continues.

Alarmingly, Boko Haram, a militant Islamist group in northern Nigeria, has invoked the lack of justice in these Middle Belt killings as one of its justifications for its horrific attacks on Christians, including suicide bomb attacks on church services in Plateau and Kaduna that left dozens dead and sparked renewed sectarian clashes.

Many commentators described the failure of the Nigerian authorities to bring the perpetrators of violence to justice as one of the major drivers of the cycle of violence. “The law that is there is just on the books,” a Christian youth leader in Jos lamented. “If you are a victim of a crisis, you will become a perpetrator of the next crisis because there is no justice.”

This impunity is largely the result of an already broken criminal justice system, including systemic corruption in the Nigeria Police Force, that has been further rendered ineffectual by political pressure to protect the perpetrators of these crimes. In the absence of accountability and effective redress, communities that have suffered violence frequently take the law into their own hands and carry out revenge killings.

Human Rights Watch found that the response of Nigerian authorities following mass killings has been surprisingly similar through the years. During or immediately following most spates of violence, hundreds of suspects were arrested. But those arrested were often randomly rounded up, in an attempt to calm the situation, or the police or soldiers dumped suspects en masse at police stations, with weapons and any other evidence collected at the scene all lumped together, making it nearly impossible to link individual suspects to any specific crime. “[N]o attorney general worth his salt wants to file a case in court when there is no evidence whatsoever,” a lawyer in Kaduna said. So, instead, after “tempers might have calmed down,” a judge in Kaduna explained, “people might not be paying attention to the cases, and you go and quietly discharge them.”

In many communities racked by violence, people witnessed the crimes, and, especially in rural areas, knew the perpetrators. Human Rights Watch interviewed dozens of eyewitnesses to alleged murder and arson. In most cases the witnesses had not reported the crime to the police. Some cited fear of retaliation by the perpetrators, but by far the most common reason cited for not reporting to the police was captured by a rural Fulani man in Kaduna State: “The police won’t do anything.”

But many witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch had indeed gone to the police, including witnesses from some of the largest mass killings in the area. In some cases, police investigators, including from Force Headquarters in Abuja, also came to the communities to interview witnesses. Witnesses said, however, that the police failed to take any action in response to their complaints, and many of them still see the men who murdered their family members and neighbors walking freely in their neighborhoods.

The failure to conduct, or follow through with, criminal investigations reflects systemic problems in the police force, where police officers frequently demand that complainants pay them to investigate crimes or at times take bribes from criminal suspects to drop investigations. This system leaves victims of communal violence, who frequently have lost everything they own, not to mention their loved ones, at the mercy of an often unresponsive and ineffective police force.

These problems are further exacerbated when the violence is communal or sectarian in nature. Police and government officials fear that if they arrest suspects, it might spark renewed violence. Community and religious leaders often rally behind members of their own groups suspected or implicated in crimes during outbreaks of violence and pressure the authorities to drop the cases.

There are, however, important exceptions. Following the 2010 violence in Plateau State, for example, the federal attorney general took the rare step of intervening by prosecuting some of the perpetrators in Federal High Court, instead of leaving them in the state courts. These prosecutions, including convictions of individuals for the March 2010 Dogo Nahawa massacre (described in this report), were an important step forward. To gain jurisdiction, however, federal prosecutors often had to try the suspects using rather tenuously connected terrorism provisions under federal anti-corruption legislation. Since then, prosecutions by state prosecutors in Plateau State have also led to several convictions.

Aside from these infrequent prosecutions, the authorities have generally treated the violence as a political problem rather than a criminal matter. They invariably set up commissions of inquiry, which are good in theory, but in practice have become an avenue for reinforcing impunity. In the words of one civil society leader, “Going to these panels buys the government time, and when the problem drops from the headlines, they go back to business as usual.” More often than not, the reports are shelved, their recommendations are rarely implemented, and the perpetrators are not brought to book.

“I don’t think it is good enough,” a judge in Kaduna argued. “That is why we are having this recurrent crisis. [For] any small thing people will just take to the streets because nobody has been really pinned down.”

This report calls on the federal authorities to promptly and thoroughly review the status and outcome of police investigations into inter-communal violence, including alleged mass murder documented in this report, and promptly file criminal charges against those implicated, or publicly explain why charges have not been filed. The police should also create a special mass crimes unit, trained in investigating mass violence, and quickly deploy it to investigate incidents of communal violence in an impartial and thorough manner. Those implicated in crimes should be promptly prosecuted according to international fair trial standards.

The National Assembly should pass legislation establishing clear jurisdiction for the federal attorney general to prosecute, in federal court, cases of mass violence, in order to better insulate cases of ethnic and sectarian violence from political interference at the state level. Human Rights Watch calls on Nigeria’s international and foreign partners, including the United Nations, United States, and United Kingdom, to publicly and privately call on Nigerian authorities to ensure that all perpetrators of mass killings are brought to justice. They should also use their expertise to offer targeted training and technical assistance to the mass crimes unit.

The cycle of violence is not inevitable. Nigerian authorities can and should take urgent steps to ensure that the perpetrators of inter-communal violence are brought to justice and the victims are compensated for their enormous personal and material losses. “I want to believe that if they had done justice, maybe a repeat of this wouldn’t have come,” a man in Kafanchan, Kaduna State, said after the April 2011 violence there. “This time justice should be done.”

Recommendations

To the Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria

- Order the inspector-general of

police and the federal minister of justice to provide a full account to

the president, within 30 days, of investigations and prosecutions of

inter-communal violence in Plateau and Kaduna states. This report should:

- Cover the incidents of communal violence, including alleged mass murder, documented in this and other reports, including incidents and individual suspects identified in the reports of the various commissions of inquiry and administrative panels, community petitions submitted to federal authorities, and alleged sponsors of violence identified by witnesses and suspects in police statements.

- Determine the status and outcome of the investigations and prosecutions of those cases, and identify the reasons that investigations and prosecutions were not conducted or completed.

- Ensure that those responsible for perpetrating or sponsoring serious crimes in Plateau and Kaduna states, including alleged mass murder, are promptly and thoroughly investigated, prosecuted, and punished, according to international fair trial standards.

- Take meaningful steps to begin

to address root causes of inter-communal violence in Plateau and Kaduna

states:

- Sponsor legislation to end divisive government policies that fuel ethnic and sectarian tensions by expressly barring any federal, state, or local government institution from discriminating against “non-indigenes” with respect to any matter not directly related to traditional leadership institutions or other purely cultural matters. Launch a broad public education campaign throughout Nigeria focused on the rights that go with Nigerian citizenship and the need for an end to discrimination against non-indigenes.

- Take meaningful steps to begin to allay fears of religious or ethnic minorities, including Christians living in predominately Muslim communities in northern Nigeria, by ensuring that their rights are protected, and that those responsible for sectarian or ethnic violence, including the April 2011 post-election attacks on Christians and their property in northern Nigeria, are promptly investigated, prosecuted, and punished, according to international fair trial standards.

- Establish and publicize clear boundaries for international and regional cattle routes and grazing reserves, and establish alternative dispute resolution mechanisms for disputes between local farmers and pastoralists.

To the National Assembly

- Hold public hearings, including in the respective Senate and House of Representatives committees on police affairs, justice, and human rights, calling on the police to give account of the status and outcome of investigations into communal violence, including alleged mass murder, in Plateau and Kaduna states.

- Enact legislation to domesticate the International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute, ratified by Nigeria in 2001, including criminalizing, under federal law, genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, consistent with Rome Statute definitions.

- Enact legislation establishing that specific crimes, such as murder, committed during mass inter-communal violence are federal crimes, which can be prosecuted by the federal attorney general in Federal High Court.

- Enact legislation to end divisive government policies that fuel ethnic and sectarian tensions by expressly barring any federal, state, or local government institution from discriminating against “non-indigenes” with respect to any matter not directly related to traditional leadership institutions or other purely cultural matters.

To the Nigeria Police Force

- Order a high-level review of

the investigations conducted by the Criminal Investigation Department

(CID) into communal violence in Plateau and Kaduna states. The review

should:

- Examine the incidents of alleged mass murder documented in this and other reports, including the incidents and individual suspects identified in the reports of the various commissions of inquiry and administrative panels, and community petitions submitted to federal authorities, and alleged sponsors of violence identified by suspects and witnesses in their police statements.

- Determine the status and outcome of these investigations and identify the reasons that investigations were not conducted or completed into these alleged crimes.

- Submit the report of the high-level review to the president and federal attorney general, and provide copies to the Plateau State and Kaduna State attorneys general.

- Order the CID to conduct prompt and thorough investigations into all incidents of communal violence in Plateau and Kaduna states, including alleged incidents of mass murder documented in this report, and without delay send completed case diaries to the respective federal or state attorneys general.

- Systematically arrest suspects where there is evidence implicating them in crimes.

- Hold community meetings in areas affected by communal violence to explain the steps taken to investigate the alleged crimes and emphasize that anyone implicated in reprisal violence or intimidation of witnesses will be investigated, prosecuted, and punished.

- Establish a mass crimes unit

based at Force CID in Abuja that can be quickly deployed to any future incidents

of mass violence to promptly and thoroughly investigate those crimes.

- Members of the unit should be trained in investigating mass crimes, including collection and preservation of evidence at crime scenes, forensic analysis, and effective and appropriate techniques in interviewing witnesses and interrogating suspects of violent crimes.

- The unit should also identify states most at risk of mass violence and provide training, in investigating mass crimes, to police investigators posted at state CID in those states.

- Promptly investigate police

officers implicated in serious abuses, such as extrajudicial killings,

committed while responding, or related to, communal violence.

- These investigations should include abuses, documented by Human Rights Watch and other groups, during the November 2008 violence in Jos and the April 2011 violence in Kaduna State.

- Give a public account, including to community leaders and victims, of the status of these investigations and steps taken to hold the police officers accountable.

- Implement reforms of the Nigeria Police Force including ending the widespread use of torture, through prosecuting any police officer where there is evidence of involvement in torture; taking clear measures to end police corruption, such as embezzlement of public funds, extortion of money from complainants or soliciting or accepting bribes from suspects; and improving the capacity of police investigators, including training and funding for forensic analysis.

To the Federal Ministry of Justice

- Give a public account of the

status and outcome of the federal prosecutions for crimes committed during

the January and March 2010 violence in Plateau State.

- Identify the reasons why individuals were not prosecuted for alleged mass murder in January 2010, including the Kuru Karama massacre and the anti-Fulani pogroms, and why sponsors of the March 2010 Dogo Nahawa massacre, identified in suspects’ police statements, were not prosecuted.

- Promptly file criminal charges and prosecute, according to international fair trial standards, all remaining suspects, including those implicated in planning and organizing the January and March 2010 violence.

- Publicly and privately call on the police to conduct and complete investigations of the other incidents of communal violence, including alleged incidents of mass murder, in Plateau and Kaduna states.

- Enact a robust witness protection program for witnesses who provide evidence, such as testifying in court, against individuals implicated in perpetrating, planning, or organizing, communal violence in Plateau and Kaduna states.

To the Nigerian Military

- Ensure that all military personnel deployed to states historically affected by communal violence, including Plateau and Kaduna, are trained in the collection and preservation of evidence at crime scenes.

- Order all military personnel, including soldiers involved in arresting suspects and collecting evidence at the scene of violence, to promptly respond to subpoenas to testify at trial. Ensure that adequate funding is provided to all soldiers subpoenaed to testify, including travel and lodging expenses.

- Promptly investigate and

prosecute soldiers implicated in serious abuses, such as extrajudicial

killings, committed while responding, or related to, communal violence.

- These investigations should include extrajudicial killings, documented by Human Rights Watch and other groups, during the November 2008 violence in Jos, alleged participation by soldiers in various attacks on predominately Berom villages since 2010, and extrajudicial killings during the April 2011 violence in Kaduna State.

- Give a public account, including to community leaders and victims, of the status of these investigations and steps taken to hold the soldiers accountable.

To the Plateau State Ministry of Justice

- Give a public account of the status and outcome of all state prosecutions for crimes committed during communal violence in Plateau State, including incidents of mass murder documented in this and other reports.

- Publicly and privately call on the police to promptly conduct and complete investigations into all incidents of communal violence, regardless of the religious or ethnic identity of the victims, including the January 2010 massacre of Muslims at Kuru Karama and the anti-Fulani pogroms.

- Promptly prosecute all individuals charged with crimes related to communal violence, according to international fair trial standards.

- Enact, in conjunction with the Federal Ministry of Justice, a robust witness protection program for witnesses who provide evidence, such as testifying in court, against individuals implicated in perpetrating, planning, or organizing violence in Plateau State.

- Consider establishing a compensation program for victims of communal violence, and ensure that compensation is provided to victims in a transparent manner, regardless of their religious or ethnic identity or indigene status.

- Proactively recruit state residents who are classified by state and local government officials as “non-indigenes,” including Muslim and Hausa-Fulani candidates, to serve as state counsel, including prosecutors, to ensure greater diversity in the Plateau State Ministry of Justice.

To the Kaduna State Ministry of Justice

- Give a public account of the status and outcome of all state prosecutions for crimes committed during communal violence in Kaduna State, including incidents of mass murder documented in this and other reports.

- Publicly and privately call on the police to promptly conduct and complete investigations into all incidents of violence, regardless of the religious or ethnic identity of the victims.

- Enact, in conjunction with the Federal Ministry of Justice, a robust witness protection program for witnesses who provide evidence, such as testifying in court, against individuals implicated in perpetrating, planning, or organizing violence in Kaduna State.

- Consider establishing a compensation program for victims of communal violence, and ensure that compensation is provided to victims in a transparent manner, regardless of their religious or ethnic identity or indigene status.

- Proactively recruit state residents who are classified by state and local government officials as “non-indigenes” to serve as state counsel, including prosecutors, in the Kaduna State Ministry of Justice.

To the United Nations, United States, United Kingdom, and Nigeria’s Other Foreign Partners

- Publicly and privately call on the Nigerian government to ensure that the perpetrators, planners, and organizers of communal violence in Plateau and Kaduna states, including incidents of alleged mass murder documented in this and other reports, are promptly investigated, prosecuted, and punished, according to international fair trial standards.

- Offer assistance to the Nigeria Police Force to help set up a mass crimes unit at Force CID in Abuja that can be quickly deployed to future incidents of communal violence. Targeted assistance could include training the unit’s investigators in best practices in investigating mass crimes, including collection and preservation of evidence at crime scenes, forensic analysis, and effective and appropriate techniques in interviewing witnesses and interrogating suspects of violent crimes.

- Offer assistance to the Federal Ministry of Justice, in conjunction with the ministries of justice in Plateau and Kaduna states, in setting up a robust witness protection program.

To the International Criminal Court

- Continue to assess, including through site visits, whether crimes committed in Plateau and Kaduna states, including incidents of mass murder documented in this and other reports, constitute crimes under the ICC’s jurisdiction.

- Continue to monitor, including through periodic visits to Nigeria, the steps taken by the Nigerian government to investigate and prosecute those implicated in crimes in Plateau and Kaduna states, in particular those responsible for planning or organizing incidents of alleged mass murder documented in this and other reports.

Methodology

This report examines the major incidents of inter-communal violence in Plateau and Kaduna states in central Nigeria. These two states were selected because they have each witnessed more communal violence and suffered higher death tolls than any of the other states in Nigeria. The research examines closely the largest incidents of violence in each state since 2010, the January and March 2010 violence in Plateau State and the April 2011 violence in Kaduna State, and documents how the Nigerian authorities responded in the aftermath of these mass killings. The report explores the reasons that the Nigerian authorities have not brought to justice the perpetrators of these crimes and the impact of the lack of accountability.

This report is based on field research in Plateau and Kaduna states in December 2010; April, May, August, and November 2011; and between January and March 2012; as well as telephone interviews with witnesses in January and March 2010 and January 2011. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 180 witnesses and victims of sectarian or ethnic violence in Plateau and Kaduna states, including 55 eyewitnesses to murder. Given that communal violence has occurred in dozens of communities in these two states, the research focused on the largest incidents of mass killing as well as some of the smaller, but significant, incidents of violence prior to or following these mass killings.

In the major incidents of violence during 2010 and 2011 documented in this report—including violence in Jos, Kuru Karama, and Dogo Nahawa in Plateau State; and Zaria, Kaduna, Maraban Rido, Zonkwa, Matsirga, and Kafanchan in Kaduna State—Human Rights Watch interviewed witnesses or visited the scene of the incident within a week of the violence. Human Rights Watch followed up on these witness interviews with additional interviews, in 2011 and 2012, with other witnesses from these and other communities.

Human Rights Watch asked witnesses to describe what they witnessed, whether they could identify individual perpetrators, whether they have reported the incident to the police, and what has been the response of the police. Most of the interviews were conducted in private to protect the identity of the witnesses. Several group interviews were also conducted with victims of the violence to collect information on how the police responded. Each interviewee was informed of the purpose of the interview and the ways that the information would be used, and all interviewees verbally consented to be interviewed. Some individual interviews were completed in a few minutes, while many took more than an hour to complete. Human Rights Watch did not give witnesses financial incentives or promise any benefits to individuals interviewed. Human Rights Watch has withheld the names of many of the witnesses to protect them from possible reprisals.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed police officers, state judges, federal and state prosecutors, lawyers, community leaders, Christian and Muslim clergy, and civil society activists in Plateau and Kaduna states as well as Abuja. Human Rights Watch collected and reviewed all available reports of state commissions of inquiry and federal panels of investigation, reports submitted to these bodies by various affected communities, and court documents from cases filed in federal and state courts. A Human Rights Watch researcher also attended the judgments in three criminal trials related to the 2010 Plateau State violence, in Federal High Court in Jos in December 2010. Human Rights Watch has been reporting on the violence in Plateau and Kaduna states since at least 2001, and its investigations during that time also inform this report. These documents and interviews helped establish the response of the Nigerians authorities in the aftermath of the violence and the reasons for, and impact of, their actions or their failure to act.

I. Background: Religion, Ethnicity, and Power in Nigeria

Nigeria, with more than 250 different ethnic groups, is a country of great diversity. Its national population of some 170 million people is roughly evenly divided between Muslims and Christians. Ethnic identity and religious and political affiliation often overlap. The vast majority of northern Nigeria is Muslim and primarily from the Hausa or Fulani ethnic groups, often referred to together as Hausa-Fulani.[1] In southwest Nigeria, where the Yoruba are the largest ethnic group, the region has large Christian and Muslim populations, while the southeast of the country is dominated by the Igbo ethnic group and is largely Christian. The Middle Belt in central Nigeria is home to numerous smaller ethnic groups, often referred to as minority groups, most of which are predominately Christian, although many areas in this region also have large Muslim populations.[2]

Many of Nigeria’s ethnic groups had no relationship to each other before being shoehorned into the same colony in 1914 by the British colonial government. The pre-colonial relationships that did exist between Nigeria’s different groups were often antagonistic. In the Middle Belt region, for example, numerous minority groups during this time resisted conquest and were victims of frequent slave raids by the more powerful Hausa-Fulani states to the north.[3]

Following Nigeria’s independence in 1960, the country’s three administrative regions—Northern, Western, and Eastern—were eventually divided into 36 states, including Plateau and Kaduna. [4] State and local governments in Plateau and Kaduna—as well as in varying degrees other states across Nigeria—enforced divisive state and local government policies that discriminate against individuals solely on the basis of their ethnic heritage or in some cases religious identity. Ethnic groups that can trace their ancestry to those regarded as the original inhabitants of an area are classified as “indigene” groups, while all other people in that area, regardless of how long they or their families have lived there, are referred to as “settlers,” and relegated to permanent second-class status. Non-indigenes are often denied access to state and local government jobs and academic scholarships, while those who cannot find a local government in Nigeria to grant them an “indigene certificate” are effectively “stateless” and cannot apply for federal government employment, thus denying them access to some of the most important avenues of socio-economic mobility. [5]

In Plateau State and southern Kaduna State, numerous minority ethnic groups, together, constitute the majority, and are recognized as the indigenes, but they also see themselves in a position of vulnerability in their own communities. Not only do they face economic competition from Yoruba and Igbo residents who have migrated to the Middle Belt with well-established connections to the more economically prosperous south, but they also face economic competition as well as the risk of political, cultural, and religious domination by Hausa-Fulani Muslims from the north. According to leaders of these indigene groups, the Yoruba and Igbo have not challenged their political power or threatened their cultural or religious identity, but the Hausa-Fulani have been much more forceful in asserting cultural rights, advancing their religious identity, claiming indigene rights, and seeking political power in this region.[6]

The leaders of Christian indigene groups often openly accuse the Hausa-Fulani of attempting to take over their land, “dominate” the minority groups, and impose Islam on the region. They also point to the willingness of the Hausa-Fulani to resort to violence to achieve these ends. For example, in the village of Kuru Karama in Plateau State, a community leader, who is a Christian from the Berom ethnic group, told Human Rights Watch, “All we see is that they [the Hausa] want to dominate our land here and to get us to leave our land,” adding, “If we refuse, they kill us.”[7]

As the Hausa-Fulani population in Plateau State has expanded, state and local government officials in recent years have actively sought policies to favor members of indigene groups and exclude opportunities for Hausa-Fulani residents, including from state and local government employment.[8] Muslims leaders point out that Hausa-Fulani in Jos have been subjected to “all sorts of marginalization, discrimination, [and] exclusion,” by the Christian state and local government officials.[9] These policies have led the Hausa-Fulani to vocally advocate for their right to be treated as equal citizens in the communities where they live.[10]

Similarly, Hausa-Fulani in southern Kaduna State complain that they are still treated as perpetual “settlers” and second-class citizens by the Christian indigenes, despite, in some cases, Hausa-Fulani families living in these communities for several hundred years.[11] On the other hand, Christians in the northern part of the state complain that they too are discriminated by the majority Hausa-Fulani Muslims.[12] Independent panels set up by the federal government to investigate the Kaduna and Plateau violence have recommended the federal government take steps to end government discrimination based on indigene status, but the government has taken no action.[13]

Rural communities in Plateau and Kaduna also have large populations of rural Fulani. Fulani pastoralists have long used migratory cattle routes through West Africa, including the fertile Middle Belt lands for grazing. In the early 1900s, Fulani from northern Nigeria also migrated south and settled in rural communities throughout Plateau State and southern Kaduna State. The rural Fulani, who primarily raise cattle for their livelihood, are predominantly Muslim, while the surrounding indigene groups, which are largely Christian, are mostly farmers. Although there have been some efforts to establish clear cattle routes and grazing reserves in these areas, periodic disputes between the Fulani pastoralists and indigene farmers often over destruction of crops or cattle theft, have also sparked conflict.[14]

Fulani cattle and herders who migrate far from home are vulnerable to attack. To counter this threat, the Fulani have established a reputation in the region that “if they or their cattle are attacked there will always be a response at a later date” to avenge the attack.[15] As the emir of Wase, a traditional ruler in southern Plateau State, pointed out in 2010, Fulani herders have “peculiar attitudes” and will “neither forget nor forgive.” He added that to the network of Fulani pastoralists across West Africa, “an attack on one was tantamount to an attack on the others.”[16] This culture of revenge and self-preservation is also often referenced in explaining the Fulani’s attachment to their cattle. In the words of a Fulani leader in Barkin Ladi local government area of Plateau State, “If you take a Fulani’s cow, [it is] better you kill him.” He explained that for a Fulani pastoralist, his cattle are not only the source of his livelihood but also his very identity: “He depends on the cows for his living. He sells cows to pay school fees for his children. He sells cows to feed his family. He sells cows for shelter, [and] he sells cows for [medical] treatment.” The Fulani leader added, “He [the Fulani pastoralist] would prefer to be killed than his cows to be taken away, because if his cows were taken away, he has nothing to do and is no longer relevant in society.”[17]

History of Conflict in Plateau State

At the heart of the inter-communal conflict in Plateau State is a longstanding struggle for power and cultural dominance in Jos, the ethnically diverse state capital located near the state’s northern border.[18] This conflict has pitted the predominantly Christian Berom ethnic group, along with the smaller Afizere and Anaguta ethnic groups, which are also largely Christian, against the predominantly Muslim Hausa-Fulani. Religious and ethnic identities largely overlap in these groups, resulting in one serving as a proxy for the other. The Afizere, Anaguta, and Berom are recognized by the state and Jos North local government as the indigenes of Jos, while the Hausa-Fulani are regarded as settlers.[19]

The Hausa, which are the largest ethnic group in northern Nigeria, claim that their ancestors migrated to the area in the early 1900s, or earlier, and settled the land where Jos now sits. While they recognize the Afizere, Anaguta, and Berom as the indigenes of the surrounding areas, they claim that the Hausa were the first inhabitants of what is now the city of Jos, or at least helped establish it.[20] As the spokesperson for the Muslim community in Jos put it, “We are equal stakeholders, even if you claim to be an indigene, and we came [to Jos] and met you here, this place was brought about by our collective efforts, and we have a right to partake in it.”[21]

The Afizere, Anaguta, and Berom, on the other hand, insist that the Hausa, like the Yoruba or Igbo from southern Nigeria, must accept their position as “settlers,” or outsiders, who have migrated to Jos and have no claim to chieftaincy rights and no right to government benefits reserved for the indigenes. [22]

As Jos expanded during British colonial rule, and continued to grow after independence, the Hausa grew to become, or according to some commentators remained, the largest ethnic group at the center of the city. In 1991, the federal military government, under Gen. Ibrahim Babangida, who seized power in a military coup in 1985 and stepped down in 1993, split the Jos local government area into two administrative posts—Jos North and Jos South. The city center fell within the boundaries of Jos North, while the town of Bukuru became the headquarters for Jos South local government. Christian indigene leaders objected to the new boundaries, since it gave the Hausa-Fulani “numerical dominion” in Jos North—and thus the capital of Plateau State. They interpreted the move by General Babangida, a northern Muslim, as part of a “grand plan by the Hausa-Fulani to seize Jos” for themselves.[23]

The conflict in Jos has also spilled over to the predominately Berom towns and villages just south of Jos. The bloodletting has primarily pitted the Berom Christians, many of them farmers, against the Hausa-Fulani residents and rural Fulani pastoralists who have migrated over the years to these areas. As in Jos, the Berom are recognized as indigenes and the Hausa and Fulani are classified as the settlers.

In the southern part of Plateau State, communal conflicts have also centered on competing claims by ethnic groups to indigene status, as well as disputes over the selection of traditional chiefs, and conflicts between Fulani pastoralists and farmers from indigene groups, such as the Tarok, which are predominately Christian.[24]

The conflict over indigene rights has been particularly fierce in the town of Yelwa, in Shendam local government area, between the predominately Christian Goemai and the largely Muslim Jarawa ethnic groups. Goemai are the largest ethnic group in Shendam and are recognized as indigenes. Yelwa, on the other hand, is predominately Muslim, made up of a large number of Jarawa and other predominately Muslim ethnic groups. The Jarawa, however, have refused to accept the “settler” label or the pervasive discrimination that accompanies it.[25]

History of Conflict in Kaduna State

Kaduna State, located on Plateau State’s western border, straddles Nigeria’s ethnic and religious divide. Northern Kaduna’s population is largely Muslim and Hausa-Fulani, while southern Kaduna is predominantly Christian and home to some 30 ethnic groups. Unlike Plateau State, where Christians from minority ethnic groups dominate state politics, Kaduna State has historically been controlled by Hausa-Fulani politicians, though members of minority Christian ethnic groups retain significant political power and hold key government posts.

The state capital, also called Kaduna, is an ethnically diverse city whose population reflects the divisions of the state and of Nigeria as a whole.[26] The city is home to people from all over the state and ethnic groups from other parts of Nigeria, including large and deeply rooted Igbo and Yoruba communities whose ancestors migrated during the colonial period in pursuit of jobs and other economic opportunities. The river that intersects the city serves as a symbolic and physical divider for the largely segregated city.

Relations between the Hausa-Fulani and the predominantly Christian ethnic groups in southern Kaduna have long been tense. Prior to colonial rule, the peoples of what is now southern Kaduna were regularly subjected to slave raids by forces under the control of the powerful Zaria (also known as Zazzau) Emirate.[27] Under British rule, southern Kaduna communities, which had long resisted northern conquest, were placed under the direct control of the emir of Zaria—in many areas for the first time. Since 1960 intrastate politics have continued to be dominated by claims of marginalization and exclusion voiced by southern Kaduna community leaders, who claim that the state government openly favored its Hausa-Fulani population. These tensions have boiled over into deadly ethnic and sectarian violence.

Following a trend common to other parts of Nigeria, Kaduna’s longstanding communal tensions have increasingly been expressed in religious rather than in ethnic terms. In 2000 Christian groups openly contested the possibility of the imposition of Sharia law in the state.[28] Sharia law has a long history in northern Nigeria. In the early 19th century, Usman dan Fodio, a Fulani preacher, established the Sokoto Caliphate and Sharia law across much of what is today northern Nigeria.[29] After the British overthrew the Sokoto Caliphate in 1903, the colonial rulers retained some aspects of Sharia, including for criminal offenses, but at independence in 1960 Nigeria’s new government limited Sharia to civil matters.[30] The military ruled Nigeria for nearly 30 of its first 40 years of independence, but following the return to civilian rule in 1999, the clamor for Sharia in the north again intensified. Northern politicians capitalized on the populist mood, and state legislatures in 12 northern states began adopting legislation that added Sharia law to state penal codes.[31] Christian leaders, especially Christian minorities in the north, opposed these moves. Although Sharia was adopted as a parallel law to the existing penal codes, and the criminal provisions only applied to Muslims, Christian leaders saw it as a step toward Islamizing the north and undermining the equal rights of non-Muslims under a secular state.[32]

The Kaduna State legislature in 2001 passed legislation extending Sharia to cover criminal law and establishing Sharia courts. The legislation passed was a modified or watered-down version of Sharia, as a compromise to make allowances for the fact that the state has a large Christian population. [33]

II. Inter-Communal Violence in Plateau State, 1994-2008

Plateau State’s official motto is “land of peace and harmony.” For the past two decades, however, this state has been anything but peaceful and harmonious. Beginning in the mid-1990s, tension increased between Hausa-Fulani and predominantly Christian ethnic groups in Jos. The first major inter-communal riots erupted in 1994 and were a harbinger of far worse to come.[34]

1994 Jos Riots

In 1994 Plateau State’s military administrator appointed a Hausa-Fulani to serve as chairman of the Jos North local government. Christian indigene groups protested the appointment. The military administrator eventually capitulated to the pressure and suspended the appointment.[35] Hausa-Fulani leaders responded by protesting the governor’s decision.

On April 12, 1994, Hausa-Fulani residents took to the streets and the protest turned violent. Hausa-Fulani rioters burned shops and vehicles. [36] Christians retaliated and torched a market and mosque and attacked the headquarters of the Izala Islamic sect—a conservative Salafist group—killing two Muslim teachers and burning a mosque, homes, and a school. [37] A commission of inquiry set up by the military administrator found that two other people also died in the violence. [38]

The police arrested 104 people during the rioting. [39] The commission of inquiry identified other suspects implicated in the violence [40] and urged the authorities to hold the perpetrators accountable to “forestall future incidences” of violence. [41] But no one was brought to justice. “I can say authoritatively,” Plateau State Attorney General Edward Pwajok told Human Rights Watch in April 2013, “nobody has been prosecuted as a result of the 1994 violence in Jos.” [42]

2001 Jos Crisis

The struggle for “ownership” and political power in Jos intensified following Nigeria’s return to civilian rule in 1999. Christian indigenes were elected to the posts of state governor and chairman of Jos North local government. But Christian indigene leaders were angered when the federal government, in June 2001, appointed a Hausa resident from Jos to fill a federal government post in Jos.[43] They insisted that the position should be filled only by an indigene, and some threatened violence if his appointment was not rescinded.[44] When he attempted to assume his post in August 2001, death threats and xenophobic messages were posted at his office.[45] Tensions were further inflamed by leaflets circulated in the name of a Hausa-Fulani group threatening violence against Christian indigenes.[46] Despite the warning signs, the police and state government did little to defuse the situation.[47]

Violence erupted in September 2001, triggered by a Christian woman who attempted to pass through a group of Muslim worshipers praying on a road outside a mosque during Friday prayers in the Congo Russia neighborhood of Jos. Worshipers asked her to go around or wait until the end of prayers, but she refused, witnesses said. An argument ensued between her and some of the worshipers.[48] Fighting soon broke out between Christians and Muslims in the area, spreading quickly to other communities in and around Jos. The state government imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew, which was widely ignored, and the police were largely ineffective at stopping the bloodletting.[49] The military was eventually sent in and quelled the violence.[50]

A commission of inquiry, set up by the state government, found that at least 913 people died in the six days of violence.[51] The authorities said some 300 people were arrested,[52] and the commission identified 107 people allegedly involved in the violence,[53] but senior officials at the state Ministry of Justice told Human Rights Watch in 2012 that they were not aware of any successful prosecutions related to the 2001 violence.[54]

2004 Yelwa Massacres

Deadly inter-communal violence continued in Plateau State over the next three years. Between 2002 and 2004, ethnic bloodletting left more than 1,200 people dead. The worst violence during this period occurred in southern Plateau State, including horrific massacres in the town of Yelwa in February and May 2004.

Following a series of attacks in February 2004 in villages in southern Plateau State, which left both Christians and Muslims dead, violence broke out in Yelwa on February 24.[55] Armed Muslim men killed at least 78 Christians in Yelwa, and possibly many more, including the massacre of at least 48 Christians inside a church compound.[56]

On May 2 and 3, Yelwa was again attacked, this time in what appeared to be a coordinated attack carried out by Christians from Yelwa as well as Christians from surrounding communities and local government areas.[57] Large groups of men surrounded Yelwa, blocking all the roads leading out of the town, and massacred Muslim residents, burning their houses, shops, and mosques, without any intervention by the police. Soldiers eventually dispersed the attackers about noon the next day.[58] Human Rights Watch estimates that at least 700 people were killed in the violence.[59]

Christian men also abducted several hundred Muslim women and children. Some of the women were held for several weeks in surrounding communities and repeatedly raped, or killed, witnesses said. But police and soldiers who were sent to search for the abducted women and children did not arrest the perpetrators. As one police officer explained to Human Rights Watch, “I have not been asked to arrest anyone, but to recover property and missing people.”[60]

In the northern city of Kano, Muslims protested the Yelwa killings. The protests soon turned violent, and on May 11 and 12, mobs in Kano killed more than 200 Christian residents.[61] The next week several Christian villages in southern Plateau State were also attacked, leaving dozens dead.[62]

On May 18, President Olusegun Obasanjo declared a state of emergency in Plateau State, describing the situation as “near mutual genocide.” He suspended the state governor, Joshua Dariye, whom he blamed for the violence, and appointed an interim administrator. The interim administrator set up an ambitious six-month program to restore peace in the state, including a month-long “peace conference,” special courts to prosecute perpetrators of the violence, and proposed a truth and reconciliation commission.[63]

The police reported, in June 2004, that 77 suspects had been arrested and charged to court for the February violence in Yelwa, while 10 suspects were charged to court for the May attack.[64] In a speech to the Nigerian Senate in October 2004, President Obasanjo seemed to back down from the emphasis of bringing the perpetrators to justice, and plans to establish a truth and reconciliation commission were dropped.[65] In November 2004, the state of emergency, which may have provided short-term calm but no long-term solution, was lifted, and Dariye returned to his post as governor. Senior officials at the state Ministry of Justice told Human Rights Watch in 2012 that they were not aware of any successful prosecutions in relation to the 2004 violence.[66]

2008 Jos Violence

Following the 2001 violence in Jos, the state government held no elections for the bitterly contested position of chairman of the Jos North local government. Successive state governors simply appointed administrators—Christian indigenes from the state—to fill the post.[67] On November 27, 2008, the state eventually held local government elections. The ruling party nominated a Berom Christian as candidate for Jos North local government chairman, while the main opposition party nominated a Hausa-Fulani Muslim candidate. At stake were not just control of the public treasury and the ability to dole out patronage, but also potential control over determining which ethnic groups would be granted indigene status and the “ownership” of Jos.[68]

The statewide elections were generally peaceful, but as votes were counted that night, opposition party agents claimed state election officials tried to rig the results in Jos North in favor of the Berom candidate.[69] Clashes broke out during the night between Christian and Muslim youth, who had gathered outside the building where the votes were being counted to “protect their votes,” and police had to evacuate party agents and election officials.[70]

The situation soon further deteriorated. As word spread through the Hausa-Fulani community that morning that their candidate had allegedly been rigged out of office, Hausa-Fulani youth, including in the Alikazaure neighborhood, began attacking Christian homes and businesses, chanting Allahu Akbar (God is great).[71] The violence soon spread, and Christian youth attacked Muslim homes, shops, and mosques. Mobs of Muslims and Christians targeted and killed victims simply based on their ethnic identity or perceived religious or political affiliation.[72]

The police were largely absent in many parts of town during the violence that day, witnesses said, and the military was called in to restore order.[73] The following day, November 29, the police and military responded with excessive force, including the alleged extrajudicial killing of more than 130 people, the vast majority young Hausa-Fulani men.[74] According to religious leaders, by the time the violence ended, at least 761 people were dead.[75]

The authorities said that 563 people were arrested during or immediately after the violence.[76] The federal government responded by establishing a panel of investigation, and the state government set up a commission of inquiry.[77] The state commission, which was boycotted by the Muslim community, identified 29 individuals accused of direct involvement in the violence and called on the police to investigate them.[78] The federal panel was still holding hearings in January 2010 when violence erupted again in Jos and never completed its work.[79]

In December 2008 the state Attorney General’s Office charged more than 300 individuals before the state High Court.[80] The police, however, transferred the detainees, along with their case files, to Abuja. The Plateau State government repeatedly demanded that federal authorities return the suspects to Jos to face trial.[81] The federal attorney general “promised that he would do the right thing by directing the police to return all the case diaries to me,” Plateau State Attorney General Edward Pwajok told Human Rights Watch. “That hasn’t been done.”[82] By the middle of 2009 all the cases relating to the 2008 violence had been dismissed, he said, adding that no one has been prosecuted in either state or federal court.[83]

The police commissioner in charge of the Jos investigation at the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) in Abuja told Human Rights Watch in February 2009 that the police had gone through the case diaries and released many of the detainees because there was no evidence linking them to any alleged offense.[84] Human Rights Watch requested information on what happened in the remaining cases.[85] The police responded in November 2013 that the individuals identified by the commission of inquiry were “undergoing trial” but provided no further detail.[86]

III. Renewed Communal Violence in Plateau State, 2010-2013

Tensions were still simmering from the 2008 violence when violence again erupted in January 2010 in Jos. The violence spread to towns and villages south of the city, leaving hundreds dead in brutal massacres. Over the next three years in Plateau State, hundreds more were killed in ethnic and sectarian bloodletting.

The January 2010 Jos Violence

The January 2010 violence in Jos was sparked by a dispute at a construction site when a Hausa-Fulani man attempted to rebuild his house that had been destroyed during the 2008 violence. On January 17, the man brought in a crew of Hausa-Fulani workers to the predominantly Christian neighborhood in Nassarawa Gwom. Christian residents said that the workers, who were mixing cement on the road in front of the house, tried to block the Christian residents from using the road and hurled insults and rocks at them. The building owner, on the other hand, said that Christian youth demanded that his crew stop working and attacked some of the workers. Soldiers intervened and allowed the construction workers to finish mixing the cement. After the workers left, witnesses said, some Muslim youth returned and fighting broke out between Muslim and Christian youth. It spread to neighboring areas as Muslim youth set fire to some of the Christian houses and a nearby church, according to witnesses.[87]

The Plateau State police commissioner told journalists at a press conference: “This morning there was a breach of the peace by a handful of [M]uslim youths who, without any form of provocation whatsoever, started attacking people who were going to church particularly around St. Michael Catholic Church in Nasarawa Gwong area.” [88] The state government announced a dusk-to-dawn curfew in the city. [89] The following day, January 18, the police said that security personnel had “succeeded in quelling the unrest and restoring calm in the affected area of the city.” [90] Some of the initial media reports put the death toll at 25, although Muslim leaders told Human Rights Watch that by January 18 they had buried 71 people. [91] The worst of the bloodletting was yet to come.

In the pre-dawn hours of January 19, violence again erupted, this time in the adjacent town of Bukuru. Muslim and Christian youth fought and roving mobs burned houses, shops, and places of worship in Bukuru and again in Jos. The state government responded that morning by imposing a 24-hour curfew in Jos and Bukuru.[92]

The violence, however, soon spread to smaller towns and villages south of Jos and Bukuru. Armed groups of Christians, predominantly from the Berom ethnic group, attacked Muslim residents in dozens of settlements in what appeared to be coordinated attacks. The mobs killed or drove out Muslim residents, including in some cases butchering women and children, and burned Muslim homes, property, and mosques. In many of the communities, all the Hausa-Fulani residents, many of whom had lived there for their entire lives, were killed or driven out of the area. Some of the worst massacres on January 19 took place in Kuru Karama, Tim-Tim, Sabon Gidan Kanar, Sabon Gidan Forum, and Kaduna Vom, in Jos South local government area. Numerous rural Fulani settlements in Jos South, Barkin Ladi, and Riyom local government areas were also attacked.

According to Muslim leaders, following the January 17 violence the state government repeatedly broadcast the police commissioner’s statement attributing the violence to Muslims in Jos attacking, without any provocation, Christian worshipers. They allege this was used to incite the attacks on Muslims in the towns and villages south of Jos.[93]

By the time the violence ended, hundreds of people were dead. Muslims leaders said that 968 Muslims were killed.[94] Christian leaders said that 57 Christians were killed, including two pastors, and 23 churches were destroyed.[95] The police, on the other hand, released a statement in January 2010 that put the death toll at 326.[96]

The Kuru Karama Massacre

Satellite image of the town of Kuru Karama, Plateau State, 10 months before the January 19, 2010 attack. © 2013 DigitalGlobe. Source: Google Earth. Image date: March 26, 2009

Satellite image of Kuru Karama 21 months after the January 19, 2010 attack. Mobs killed or drove out the entire Muslim population, destroying some 250 houses and shops, mosques, and an Islamic school. © 2013 DigitalGlobe. Source: Google Earth. Image date: December 7, 2011 |

Human Rights Watch interviewed 21 witnesses to the January 19 attack on Kuru Karama (also known as Kuru Jentar), a predominantly Hausa-Fulani and Muslim settlement located in the Berom heartland of Plateau State. Some of the Hausa-Fulani families had lived in Kuru Karama for several generations, descendants of migrants who had come to work in the tin mines in the early 1900s.[97] The tin mines later closed, but some of the residents continued to work as artisanal miners or at a nearby mineral processing company, known as Kavitex.

Witnesses said that on the morning of January 19, Kuru Karama residents heard the news on the radio and television that there were more problems again in Jos and that a 24-hour-curfew had been imposed. Some of the Hausa-Fulani residents said they also received information that some Berom were coming to attack them.[98] The community leaders, including the Berom and Hausa leaders, met that morning at Kuru Karama’s police post.[99] The ward head, who is Berom, recalled that when “we heard that Muslims had attacked a church in Jos, we the traditional leaders called [together] the stakeholders in Kuru Jentar, and we [all] agreed we should not allow what happened in 2001 to repeat in 2010.”[100] The Berom leaders and the police officer in charge of the police post, who was also Christian, assured the Muslim leaders at the meeting that there would be no violence and they should return to their homes.[101]

Shortly after leaving the meeting, about 10 a.m., residents said they began to see groups of people, armed with guns, sticks, machetes, and bows and arrows, converging on the outskirts of the community. Some of the people came on foot while others arrived in vehicles, witnesses recalled. Muslim witnesses said that the people were Christians, nearly all Berom, from surrounding communities.[102] When the Muslim leaders saw this they gathered the Muslim residents together near the police post and central mosque.[103]

Some of the Christians in Kuru Karama tried to intervene. A Christian pastor went over to the armed mob that had gathered and pleaded with them to leave, but they would not listen to him and instead hit the pastor, witnesses recalled.[104] The pastor told Human Rights Watch that he tried to “calm the situation,” but “I was about to be beaten or shot,” he said. “After that I ran.”[105] Many of the Muslim residents also ran, looking for places to hide or ways to defend themselves. The armed mob then began their attack.

Muslim witnesses said that the Muslim residents were outnumbered and had little to defend themselves with. As one leader recalled:

[We] went back to defend ourselves, but we couldn’t make it because we didn’t have anything to protect ourselves with, and we couldn’t run because they had surrounded us. So we had to just try to defend ourselves before they killed us…. They were shooting us, hitting us with knives, burning us. They followed us, so we went to another place, [but] they killed us [there].[106]

Survivors said that from that morning until nightfall, the mob hunted down and murdered Muslim residents, including hacking to death and burning alive men, women, and children. The mob set fire to the Muslim homes, shops, and the three main mosques. According to Muslim witnesses, some of the Christian Berom residents of Kuru Karama also joined in the attack. Christian women—from Kuru Karama and other communities—allegedly carried containers of petrol that were used to set fire to houses and Muslim victims caught by the mob. Witnesses described to Human Rights Watch at least two instances where they saw women participating in the killing, including beating to death a small boy and setting fire to an old man after he had been beaten by the mob. [107]

Witnesses also said, however, that some Christians in Kuru Karama helped hide Muslims during the killing. Two Muslim women, for example, described to Human Rights Watch how Christian residents intervened and hid them in their houses.[108]

Some of the Muslim women said they remained at the central mosque for safety. But soon after the violence started some of the attackers entered the compound of the mosque and started killing people. A Hausa woman described seeing the mob attack a pregnant woman who was in labor at the central mosque and set fire to the woman and her newborn baby:

I saw the mob approach shooting and beating people. Inside the compound of the central mosque where we gathered, a woman went into labor. I saw the head of the baby had come out. I went to help the woman and thought, “If they saw me helping her, the mob would not hurt me.” But they still came, and I had to run and hide behind a zinc fence [nearby]. The mob surrounded the woman and started hitting her with sticks. As the mob was beating her, she gave birth to the baby. I saw them then bring petrol and pour it on her and set her on fire. I saw this with my naked eyes. [109]

Witnesses said the Kuru Karama attack was particularly brutal. As one Muslim leader recalled, “In 2001 they didn’t kill women, they didn’t kill children, but this crisis they have killed women and children.”[110] A Berom woman who was married to a Muslim man and converted to Islam said that two Berom men, whom she knew, killed two of her children:

I was in my house around 10 a.m. and I heard people shouting that the Berom people had come to attack us…. They surrounded us and started killing people and burning houses. Some of them know that I am Berom. I was begging them that they shouldn’t kill me. Then one of them said they will kill my children because their father is a Muslim, and if they killed them, I would become a Christian.

They collected [two of my] children from my hand and killed them in front of me. One of the men had a big stick and hit my baby boy on his head. Another man with a cutlass hit my girl on her hand and neck. I started crying. I couldn’t look at it. I didn’t want to see the children [die]. I was begging them, and they left me with my two other children.[111]

As the killing continued during the day, some of the Muslim residents were able to flee to the nearby compound of the Kavitex mining company. But members of the mob also entered the compound and continued their killing there. A Muslim woman who ran to the Kavitex compound recalled what she saw in the compound:

About 1:30 or 2:00 p.m. the mob saw us and came into the compound. They saw my father and went to him. They started hitting him with a stick on his head. He became unconscious and fell into a ditch. They then poured petrol on him and put fire on him…. I saw this with my eyes.

Many of the small children had lost their parents and were crying: “Mother, Mother!” One of the men took a machete and hit a small girl on her head with a machete. When I saw this, I lay down on top of my two children. As I lay on my children, they hit me with machetes. They hit me on my head, and my left arm was broken in three places. The blood came on my children and they thought I was dead. My boy was five years old and my girl was seven years old. I stayed there until 8 p.m. Some of our men came and started shouting our names. I shouted, “I am here!” But I couldn’t get up. Some of them picked us up and took us to safety.[112]

Witnesses recalled that some of the attackers mocked the religious beliefs of the Muslim victims. A Muslim woman, whose husband and two children were killed, said that after she saw the mob kill her husband, she heard them say, “Where is your God and where is Prophet Mohammed today?”[113] Another Muslim woman who was injured in the attacked said that some of the men taunted the victims saying, “Since you are Muslim and believe in Allah, let him come and save you.” The attackers then set her father on fire and began to hack at her with their machetes.[114]

Other witnesses recalled that members of the mob referenced land and indigene disputes during the attack. A Muslim man, whose wife was killed, noted that the attackers boasted that they would take back their land from the “non-indigenes.”[115] Similarly, a Hausa woman, whose mother was killed, said the attackers told them, “Why should you come here and settle? Why should you not stay in your [own] places?”[116]

The killing continued unabated throughout the day, without any intervention from the police. One of the Muslim leaders, whose wife was killed, told Human Rights Watch that he repeatedly called the police that day: “My phone was full of credit and battery. I phoned everyone to get help—the divisional [police] headquarters, police state command—but there was no help.”[117] Another man, whose two small children were killed, bitterly lamented, “Since that thing started, until it stopped, no security agents came to rescue us.”[118]

There was a police post in Kuru Karama, but witnesses allege that rather than intervene to stop the killing, the police officer in charge of the post, who is Christian, participated in the attack. Two witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they saw the police officer shoot and kill Muslim residents, including a small boy and a woman with a baby.[119]

|

The Death of Mohammed Ojo Witnesses recall that as the armed mob surrounded the town, Mohammed Ojo, who was home from Ukraine where he worked as the driver for the Nigerian ambassador, called Plateau State’s attorney general, Edward Pwajok. The attorney general, who is a Christian Berom, lived in the nearby town of Mararaban Jama’a and is a member of Plateau State’s Security Council, which is responsible for overseeing security matters in the state. Human Rights Watch interviewed five witnesses who said they witnessed Ojo put his mobile telephone on speakerphone and heard him plead with Pwajok to intervene, explaining that Berom people had come to kill them. The witnesses recalled that Pwajok said he could do nothing for them, and the line then went dead. [120] Human Rights Watch asked the attorney general about this conversation, but he said he never received a call from Ojo that day. However, Pwajok said his [Pwajok’s wife] later told him that Ojo had called her. “She tried to reach me on phone to tell me there were attacks in Kuru,” he recalled, but “[s]he was not able to reach me immediately.” According to Pwajok, it was a “particularly rough day” and at the time she called he was in “security meetings” in Jos and his mobile telephone was switched off. [121] Needless to say, no one intervened. One survivor told Human Rights Watch that later that day he saw a group of Berom “rush at him [Ojo] with machetes and sticks.” [122] Ojo’s corpse was later found among other corpses that had been dumped inside one of the town’s wells. [123] |

A Hausa leader from Kuru Karama said he believed that the Berom attacked the Hausa-Fulani community because they were afraid that the “Hausa have taken over Jos North and soon they will take over Jos South.”[124] Fear of domination and violence at the hands of the Hausa was also expressed by one of Kuru Karama’s Berom leaders. “All we see is that they [the Hausa] want to dominate our land here and get us to leave our land. If we refuse, they kill us,” he said.[125]

Evidence of a Coordinated Attack

The evidence seen by Human Rights Watch suggests that the Kuru Karama massacre was not a spontaneous outbreak of violence but a coordinated attack carried out by armed Berom attackers. There appeared to be coordination in bringing people to the village to carry out the attack. For example, witnesses said that attackers mostly came from surrounding towns and villages, while some Christians from within the village also joined in the violence. Some attackers arrived on foot, including traveling in groups along the riverbed, while others were allegedly “ferried in” in private vehicles. One woman recalled seeing several vehicles, including minibuses, “dropping people off” before the attack.[126] Muslim leaders provided federal authorities with a list of four vehicles, including license plate numbers and the names of the drivers, allegedly used in the attack.[127]

The evidence also suggests that there were leaders organizing the attack and relaying instructions to attackers. One woman recalled how one of the attackers appeared to have received instructions from someone he was speaking with by telephone. She said that near the end of the day, a group of Berom men, who had killed her husband, came over to some Muslim women and children hiding inside a pit in the Kavitex compound. The men doused the women and children with petrol. As they were lighting a tire to throw into the pit, “One of them had a call on his phone, and we could hear what he was saying,” she recalled. “I heard him say, ‘We are finished with Kuru. There remain only 14 women.’ He [the man holding the phone] then told the others, ‘They said we should leave the women and children.’” The men put down the tire and left.[128]

Many of the Berom and Christian leaders, however, deny that a massacre took place in Kuru Karama and insist instead there were clashes in the village that left both Muslims and Christians dead. “It erupted like war,” recalled the village head, an elderly Berom man. “Christians and Muslims were both killed,” he said, although he was unable to say how many Christians were killed.[129] Similarly, the ward head told Human Rights Watch, “There is no doubt that it is not only the Christians or the Muslims that were killed. It was both sides.” When asked if he had information on how many Christians died, he responded:

Everybody ran [so] nobody could tell the number of people who died…. In a crisis like this, actually there must be cases of victims, there must be dead people and people who had injuries, there is no doubt, but actual numbers, I can’t give you the actual number of people who died in the crisis.[130]

The ward head recalled that when the violence started he too ran. He said he saw people running and heard gunshots and shouts of “Allahu Akbar” coming from the center of the village. “We saw Christians and Muslims running,” he recalled. “Everybody was running for their lives. I ran. How could I stay?”

The pastor who tried to intervene before the attack also said he did not see who carried out the attack. “I just left the vicinity. I could not stay to see what the battle was.”[131] He too insisted that “there was killing on both sides—Christians and Muslims—it was a battle and a war.” He pointed out that some of his church members were still missing, adding that “I can’t say exactly the number or whether they were killed or not killed.” None of the six churches in Kuru Karama was burned, he said.[132] All three Christian residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch said their houses had not been damaged.