Glossary / Examples of Statements

Allegation: An allegation under Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) guidelines is “a complaint of sexual abuse, that after preliminary investigation by a member of the Sexual Assault Unit (SAU),” the SAU determines “lacks the criteria of a sexual abuse offense.” Examples of cases that the MPD’s Standard Operation Procedures might consider allegations include cases in which there are inconsistencies that require follow up, or cases in which the complainant: provides contradictory statements, had sex but is unsure if a crime occurred, is unresponsive, is too intoxicated to talk, or is referred from another jurisdiction.

Clearance By Arrest: A law enforcement agency reports that an offense is cleared by arrest, or solved for crime reporting purposes, when any of three specific conditions have been met: that at least one person has been arrested; charged with the commission of the offense; or turned over to the court for prosecution (whether following arrest, court summons, or police notice).

Exceptional Clearance: Under FBI guidelines, an offense may be cleared by exceptional means when elements beyond the control of law enforcement prevent an offender from being arrested. To exceptionally clear an offense, the law enforcement agency must have met the following four conditions: identified the offender; gathered enough evidence to support an arrest, make a charge, and turn over the offender to the court for prosecution; identified the offender’s exact location so that the suspect could be taken into custody immediately; and encountered a circumstance outside the control of law enforcement that prohibits the agency from arresting, charging, and prosecuting the offender. Examples of circumstances that lead to exceptional clearances include: the death of the offender; the victim’s refusal to cooperate with the prosecution after the offender has been identified; or the denial of extradition because the offender committed a crime in another jurisdiction and is being prosecuted for that offense. At the MPD, cases may also be considered closed exceptionally if a prosecutor has declined a request for an arrest warrant for lack of prosecutorial merit. This is also known as an administrative closure.

Forensic Evidence Kit: Following a forensic exam, the various swabs and samples collected are placed in separate envelopes (or tubes) and are labeled, sealed, and put in one large envelope—the forensic evidence kit (sometimes referred to as a “rape kit” or Sexual Assault Evidence Collection Kit).

Forensic Exam: A procedure conducted by a health professional that usually takes four hours, involving a head-to-toe examination of the victim’s body, a pelvic exam, and a collection of biological samples from the victim’s body. Forensic exams are typically offered to victims who report within up to 96-120 hours of their assault, though in some circumstances it may be possible to collect evidence beyond that period.

Miscellaneous Cases: See Office Information.

MPD: Metropolitan Police Department. The primary law enforcement agency for the District of Columbia.

Office Information: Under MPD guidelines, a complaint of sexual abuse can be deemed an office information after preliminary investigation by a member of the Sexual Assault Unit, when it involves any of the following: “an arrest of a sex offender in another jurisdiction; a report of an offense that occurred in another jurisdiction (information that can possibly be used in the future); sexual activity that is not a crime; and no crime was deemed to have occurred.” Once a complaint is classified as “office information,” no further investigation is conducted or required. Police sometimes further classify these cases as “miscellaneous” or “sick [or injured] person to hospital,” but they still fall under the general broad category of cases that are not investigated but documented only for “office information” purposes.

OVS: Office of Victim Services, in the Executive Office of the Mayor of the District of Columbia. The OVS oversees the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) Program at Washington Hospital Center—the designated hospital for care of adult sexual assault victims in the District.

PD-251s: The MPD’s incident/offense reports, which the responding officer or detective is supposed to take any time a crime complaint is made.

Rape Kit: See Forensic Evidence Kit.

SANE: Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner. According to the MPD, the SANE program in D.C. “provides compassionate and timely medical care available twenty-four (24) hours a day to adult sexual assault victims (eighteen (18) years of age or older) during forensic examinations while ensuring that the evidence is properly collected and preserved. Nurses who conduct the examinations under the program have received specialized training to prepare them to perform forensic examinations in sexual assault cases, to serve as expert witnesses in court cases, and to understand the emotional and psychological impact of sexual assault on victims.”[1]

SART (or SARRT): Sexual Assault Response Team (or Sexual Assault Response and Resource Team). A community based approach in which public and private agencies work together to respond to cases of sexual assault. In Washington D.C., the SART team includes representatives from Washington Hospital Center, the US Attorney’s Office, the MPD’s Sexual Assault Unit, the Office of Victim Services, the US Park Police, and the D.C. Rape Crisis Center.

SAU: Sexual (or Sex) Assault Unit. This is the unit within the MPD that is charged with investigating all sexual offenses within the District of Columbia involving adult victims (age 18 and over). It includes “cold case” sexual assault unit detectives.[2] The Sex Offender Registry Unit also falls under the Sexual Assault Unit.

Sexual Assault Evidence Collection Kit: According to the MPD, “an evidence collection kit used to obtain evidence from a sexual assault victim.”[3] See Forensic Evidence Kit

SOP: Standard Operating Procedures for the Sexual Assault Unit. These are the MPD’s guidelines for the investigation of sexual assaults.

UCR: Uniform Crime Report. A program within the FBI that collects, publishes, and archives national crime statistics.

Unfounding: This occurs when an investigation reveals that no offense occurred, nor was attempted. Under the FBI guidelines, a case can only be “unfounded” if it is “determined through investigation to be false or baseless. In other words, no crime occurred.” For a case to be considered officially “unfounded” at the MPD, a detective is supposed to prepare a written report, which must be approved by a supervisor.

VAWA: Violence Against Women Act, originally passed by Congress in 1994 to enhance the investigation and prosecution of violent crimes against women. Under VAWA, victims of sexual assault treated at the SANE center are not required to speak with law enforcement.

WACIIS: Washington Area Criminal Intelligence Information System. An internal database of the MPD containing crime investigation records.

WHC: Washington Hospital Center. The designated hospital for forensic exams for adult sexual assault victims in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area.

Examples of Statements that Human Rights Watch Heard or Reviewed about the Metropolitan Police Department’s Handling of Sexual Assault Cases in the District of ColumbiaBy failing to classify the crime committed against me as an attempted rape or sexual assault, by ignoring my account of the story, you condemn me to a life where I mistrust the police, abandon any faith I possessed in the criminal justice system, and you have caused me more victimization than the actual perpetrator of the crime committed against me. Moreover, you fail the community you have sworn to protect… —Letter from Eleanor G., survivor of a 2011 attempted sexual assault, to MPD Chief Cathy Lanier, October 4, 2011 Reporting to the police was far more traumatizing than the rape itself. —Susan D. (pseudonym), describing interaction with the MPD in March 2011 [The detectives] told me that they did not want to waste their time with me … that no one was going to believe my report and that he didn’t even want to file it…. When I called to get the police report number [the detective] told me it was a ‘miscellaneous’ report…. This is not ‘miscellaneous’ THIS IS RAPE! —Maya T. (pseudonym), complaint form, MPD Office of Police Complaints, May 9, 2011 They just didn’t listen to me, they made me feel completely ashamed of myself, they made me feel like I was lying or like I was too stupid to understand what happened to me, that I was trying to make something a big deal that wasn’t that big of a deal. —Eleanor G., describing her interaction with the MPD in 2011 It tore me up that he did not believe me and he made it clear to me that he didn't believe me. Traumatized is the word that I felt from the investigator, in some ways, it was worse than the event itself. —Shelly G. (pseudonym), describing her experience with an MPD detective in October 2009 To hear him tell me he didn’t believe me was a slap in my face. It just knocked me down, it was a punch in my stomach. It just took the air right out of me. And where do you go from there when the policeman tells you he doesn’t believe you? —Shelly G. (pseudonym), describing her interaction with an MPD detective in October 2009 The detective was in the room with the interpreter, and two other female officers and after 40 min, the survivor was literally hysterical … the nurses and I could hear it from outside the room … she was sobbing and yelling…. We interrupted and the detective told us ‘we’ll be done when I say we’re done.’ Two min later, they walked out of the room … the detective told me there would be no case and told me to go see her. —Email from a Rape Crisis Center advocate, forwarded to the D.C. Office of Victim Services at the Mayor’s Office, April 2009 I think that filing the report was just as traumatic as the crime, if not more…. Is it common place for the police to put blame on the sexual assault victims and then completely ignore them? —Complaint form, MPD Office of Police Complaints, November 12, 2009 Investigators serve as prosecutor, judge, and jury and stop the process before it begins. —Experienced community service provider to sexual assault victims, Washington, D.C., February 16, 2011 For a sexual assault survivor who has already experienced an intense violation, to have your governmental system essentially say to you, “This didn’t happen, or if it did happen it doesn’t really count,” is devastating. —Denise Snyder, D.C. Rape Crisis Center, quoted in “Washington City Paper,” April 9, 2010 I found out you dealt with her about 4 am Friday or Saturday morning … and she chose not to make a report. Something about a gang bang and being intoxicated…. Anyway, I think it was just an OI [Office Information]. However, she now feels differently and wishes to make a report…. She says her phone isn’t working but she can be reached ... Sorry, BUT IT IS WHAT IT IS!!!!!!! —Note from one MPD detective to another, contained in an investigative file from 2009 reviewed by Human Rights Watch How can you not remember? How can we believe you? —Witness, reporting a statement made by an MPD detective to a victim, who reported being assaulted by a stranger after going to a bar but could not remember the bar’s name You shouldn’t have been outside. This is what happens at two in the morning. What do you expect? —A member of the medical staff, reporting a statement made by an MPD detective to an 18-year-old runaway who was assaulted at night Well, she could have fallen on rocks and may not have had panties on. Also what kind of girl is in a room with five guys? —Nurse, describing the response of a detective to a patient who was found unconscious in a hotel room with five men in 2010 with severe tears to her vagina and rectum that required emergency surgery You are only doing this to get immigration status, aren’t you? —Lawyers’ account of what an MPD detective told his client when she reported being kidnapped and sexually assaulted repeatedly overnight in early 2011 |

Summary

Sexual assault is all too common across the United States. An estimated one in five women in the United States is a victim of rape or attempted rape in her lifetime. However, victims who report to law enforcement may have very different experiences depending on where they live. Studies indicate that nationwide less than 20 percent of rape or sexual assault victims reported incidents to the police in 2007.[4] Many sexual assault survivors choose not to seek help out of fear that authorities will mistreat or not believe them, or that nothing will happen to their case. Unfortunately, this concern can be well founded. This report focuses on police response to sexual assault in the District of Columbia. The story of Susan D. is not uncommon.

In the spring of 2011, Susan D., a fresh-faced US government employee in her thirties, was raped by a man she met on an internet dating site. Deeply shocked, she could not sleep for two days. On the third day, she finally summoned the courage to go to the hospital for a forensic exam—a four-hour procedure involving a pelvic exam and extensive collection of evidence from her body.

At Washington Hospital Center (WHC), where she went for the exam, Susan met a female detective from the Sexual Assault Unit (SAU) of the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD)—one of the 10 largest local police agencies in the United States and the primary law enforcement agency for the District of Columbia. The detective insisted that Susan talk to her before speaking to a rape crisis center advocate (as Susan had requested), and before having an exam. Shaking and shocked, Susan agreed.[5]

For the next three hours, the detective questioned Susan, interrupting her frequently in a manner—as Susan saw it—to discourage her from reporting the assault and belittle her experience. For example, the detective interrupted Susan to say that what she had described was “not a crime,” to assert that she was herself raped twice, and to imply that Susan should consider how she would ruin her assailant’s life if she filed a report. The detective later told a nurse she thought Susan did not need a forensic exam, although the nurse did in fact administer one.

Susan later waited in vain for police to process the crime scene and collect her clothes for evidence. After an investigator hired by her assailant made threatening calls, Susan tried three times to reach the detective assigned to her case but never heard back and was unable to transfer her case to another detective. After six weeks, the police closed Susan’s case without prosecution. In the following months, Susan was diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which she believes was partly due to her contact with the MPD. “Reporting to the police was far more traumatizing than the rape itself,” she said.

***

This Report

This report focuses on the District of Columbia’s Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), its recording and investigation of sexual abuse cases, and the experience of sexual abuse survivors who sought MPD assistance. Our investigation provides strong evidence that, between October 2008 and September 2011, the MPD failed to document or investigate many complaints of sexual assault in D.C. Furthermore, in some cases that Human Rights Watch documented, police re-victimized survivors by treating them callously and skeptically, discouraged sexual assault survivors from reporting their assault or getting a forensic exam, and in some instances threatened them with prosecution for false reporting.

Our findings are based on extensive data analysis, documents from four government agencies, and more than 150 interviews.

The data indicates that in several cases, survivors who reported sexual assaults to the police never had their case documented, and others saw their cases languish when officers apparently determined that their cases were not worth pursuing before conducting an effective investigation.

The problems we documented in the MPD’s response to sexual assault do not appear to result from official MPD policy. On the contrary, the MPD has long had policies that, if effectively implemented, should have led to better outcomes. Rather, the key problem appears to be practices within the MPD that, during the period we examined, have been inconsistent with departmental policy and resulted in misclassified or undocumented cases. Inadequate training on how to handle sexual assault cases would also appear to be a contributing factor.

The MPD was made aware of many of these problems in the course of a 2008 civil lawsuit brought by a victim whose case was not investigated. In depositions, several MPD members testified that a significant number of sexual assault cases were not documented at the instruction of SAU detectives, despite official policy requiring all sexual assault complaints to be documented in an incident report. According to MPD Chief Cathy Lanier, the MPD implemented reforms following the lawsuit. Yet the Human Rights Watch research in this report indicates that problematic practices continued through 2011.

The mere adoption of new policies or training alone is not likely to lead to meaningful change of what seem to be deeply rooted attitudes within the department that have long been inconsistent with official policy. To really address this problem, the first step MPD leadership should take is to acknowledge its existence and commit to changing the practice by: (1) holding officers who do not document or investigate cases to account; (2) creating a safe and responsive environment for victims or observers of improper treatment to make complaints; (3) responding seriously to complaints; and (4) doing so transparently, with external oversight.

The failure of the MPD to thoroughly investigate all sexual assault cases has potentially devastating consequences for sexual assault victims and for public confidence in law enforcement; and violates the US’s obligation under international human rights standards, as well as official MPD policies governing adult sexual assault investigations. It also means that assailants—who may commit multiple offenses before being caught and imprisoned—may be neither investigated nor prosecuted.

Not all detectives in the MPD’s Sexual Assault Unit (SAU) are insensitive to victims: several people interviewed for this report told Human Rights Watch about a number of good detectives in the SAU who demonstrate an appropriate attitude toward these crimes. Nor is evidence of police mishandling of sexual assault cases unique to D.C. Investigations in recent years have revealed misclassification or improper closing of sexual assault cases and forensic exam (or “rape kit”) backlogs in a number of police departments across the country. Human Rights Watch has previously documented rape kit backlogs in Illinois and the Los Angeles area.

However, the MPD practices documented in this report contrast sharply with effective police responses to sexual assault in other US cities cited here.

To its credit, the MPD has recently taken some important steps to address the problems we document here. In response to correspondence and discussions with Human Rights Watch in 2012, the MPD has adopted a number of our recommendations, though it will take time to see whether there is consistent enforcement of changes in practice. Nonetheless, as we describe below, there is more the MPD and other government agencies need to do to ensure that the MPD provides an effective and appropriate response to sexual assault in the District of Columbia.

Sexual assault remains the most underreported violent crime in the United States, partly because victims fear that authorities will not believe them and that they will be re-traumatized if they report their assault. Government officials need to ensure that these fears are not realized.

Research

For this report, Human Rights Watch chose to focus on the District of Columbia because of the unusually low number of sexual assaults it reported to the FBI, as well as significantly higher than average MPD rates of “clearing” sexual assault cases than those for comparably sized cities. Low reporting rates or high clearance rates may indicate cases are being “disposed” of improperly.[6] In addition, a lawsuit about MPD’s inappropriate handling of a sexual assault case in December 2006 and evidence and experience of multiple observers since then suggested that MPD practices would be worth examining.

As part of its investigation, Human Rights Watch conducted over 150 interviews and reviewed numerous documents produced by the MPD and other government agencies. These include the Office of Victim Services (OVS) in the Mayor’s Office, which oversees the program for sexual assault victims at Washington Hospital Center (WHC)—the designated hospital for care of adult sexual assault victims in the District.

After refusing to provide investigative files for 16 months, the MPD agreed to allow Human Rights Watch access to its internal database in settlement of a lawsuit Human Rights Watch brought in December 2011 to compel disclosure of documents under D.C.’s Freedom of Information Act. As a result, Human Rights Watch was able to review investigative files for over 250 cases at the MPD’s offices in August 2012.

To better understand what reforms might be possible in Washington, D.C., Human Rights Watch also reviewed a range of policies and interviewed dozens of stakeholders about reforms undertaken in cities that have improved their investigations of sexual assault crimes: Austin, Philadelphia, Kansas City, and Grand Rapids. We also consulted 14 national experts on sex crime investigation and prosecution, reviewed International Association of Chiefs of Police model procedures, training material, and the Operations Manual for the San Diego Police Department’s Sex Crimes Unit, which is well regarded.

Main Findings

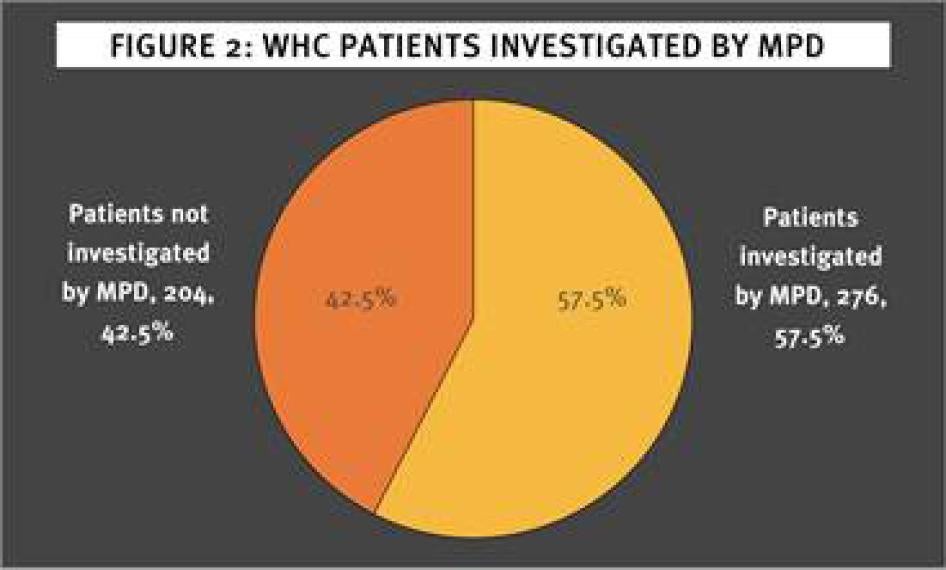

Failure to Document and Investigate

From 2008 through September of 2011, MPD officers used a variety of mechanisms to effectively shut down investigations—often before they even got started—of cases they did not deem credible. Human Rights Watch’s review of data, agency documents, and police investigative files corroborates the impressions of many victims, community advocates, and witnesses who told us that the MPD often closed cases without meaningful investigation.

As described further below, we documented the following practices that undermined the successful investigation of sexual assault cases in the District of Columbia:

- MPD officers did not document many cases, as is demonstrated by the fact that no incident report exists for a substantial number of cases recorded by Washington Hospital Center as having been reported to police, nor were these cases located in the police database.

- MPD officers classified several cases that appear to present the elements of serious sexual assaults as for “office information only” or “miscellaneous” cases. In effect, according to SAU guidelines, this means that they do not pursue the investigation further.

- In some cases, MPD officers classified what appeared to be serious sex abuse cases as a non-sex offense or as a misdemeanor, minimizing the victim’s experience and also potentially denying the victim access to support services from Victim Services within the MPD.

- In several cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch that the MPD did document, the MPD presented arrest warrant requests to prosecutors based on incomplete investigations. As a result, prosecutors rejected a large number of these requests as “weak” cases. Detectives then closed the cases and recorded them as “exceptionally cleared” even though it appears they never fully investigated them.

Missing Cases

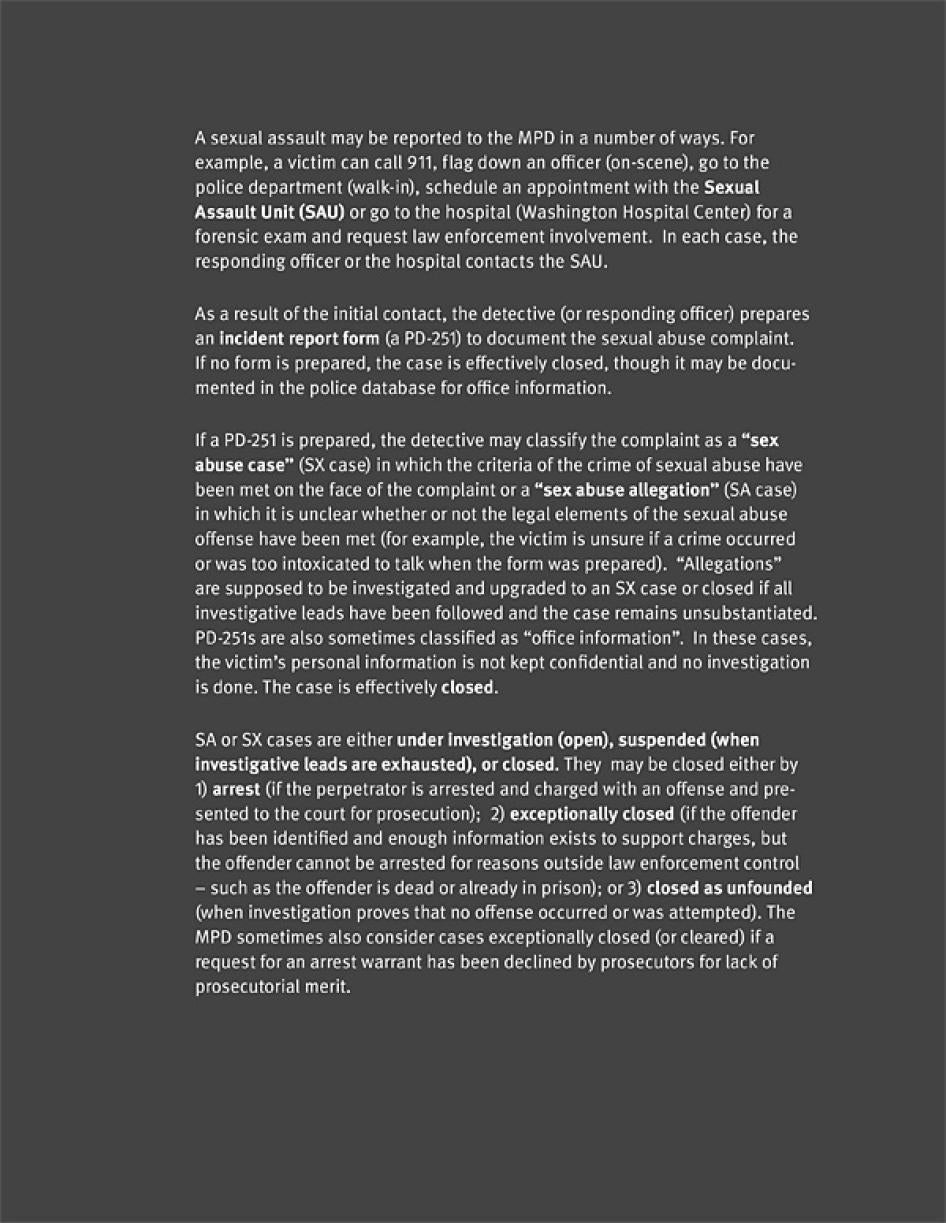

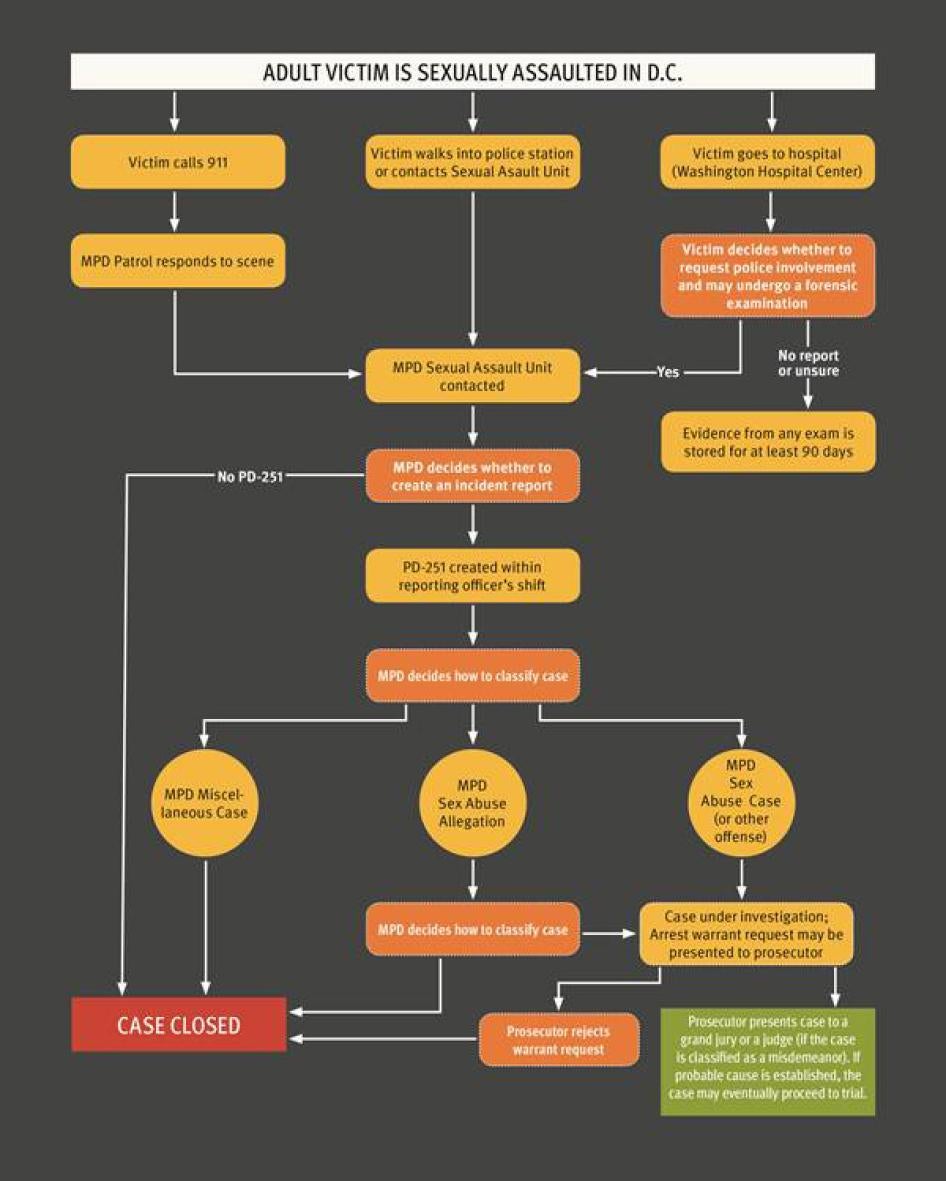

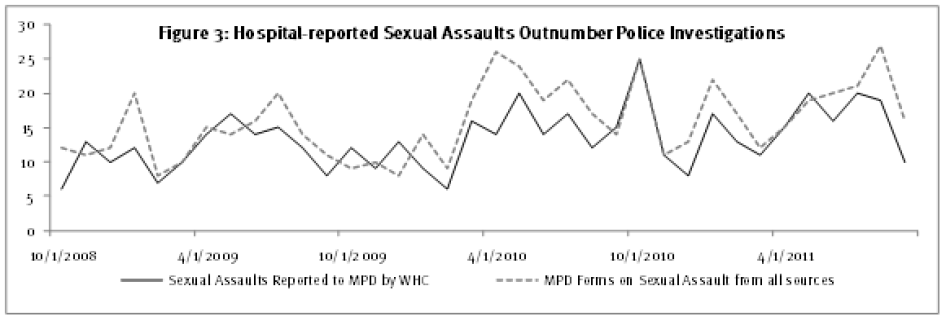

Two witnesses informed Human Rights Watch in early 2011 that when they attempted to follow up with the MPD about sexual assault reports, they found that many of the cases did not have a case number assigned to them and did not appear to be under active investigation. Based on this information, Human Rights Watch compared Washington Hospital Center records of victims who had a forensic exam and reported their assault to the MPD between October 2008 and September 2011 to MPD incident reports (known as PD-251s) relating to sexual assault complaints from the same period.[7] Our analysis excluded 311 victims who had a forensic exam but chose not to report to the police, or who reported to other police departments.[8]

According to the MPD policy since 2000, all victims who report a sexual assault to the MPD should have an incident report, known as a PD-251, documenting the complaint and assigning it a case number. [9] If no PD-251 is prepared, the reported assault will not be investigated as the necessary step to open an investigation has not been initiated. The Washington Area Criminal Intelligence Information System (WACIIS) database maintained by the police department may contain information about calls received by the MPD on sexual assaults. But, an entry in WACIIS does not mean that an investigation has been opened. For practical, investigative purposes, if there is no PD-251, it means that no official record of the assault exists in the MPD. [10] As one police source put it, “No PD-251, no investigation.” [11] When asked if an investigation should be conducted even when no PD-251incident report has been prepared in response to a complaint, Assistant Chief Peter Newsham said that “the officer would be in trouble.” [12]

However, Human Rights Watch was unable to find incident reports for a significant number of cases in which a patient underwent a forensic exam and reported to police.

- WHC records showed that 480 patients reported sexual assaults to the MPD at the hospital between October 2008 and September 2011.

- Human Rights Watch was able to locate matching MPD incident reports for 310 victims over the same period (64.5 percent of the total of cases reported at WHC).

- For the remaining 171 victims, Human Rights Watch was unable to find corresponding documentation at MPD of a reported assault. Nor could these cases be located in MPD’s database.

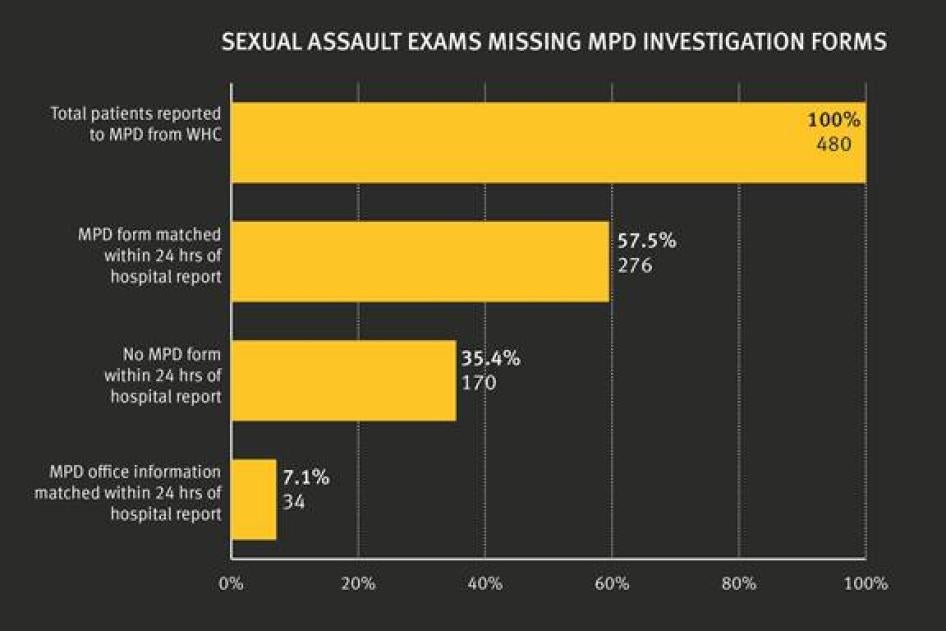

- Of the 310 cases for which we located an incident report, 34 were classified as “miscellaneous” or “office information,” usually meaning that MPD conducted no further investigation.

Since all investigations require a PD-251, the lack of incident reports suggests that there was no police follow-up for 35.4 percent of victims who reported an assault at the hospital. If we assume detectives followed MPD’s own policy and that cases classified as “miscellaneous” or “office information” have not been subject to an investigation, the number of cases reported at WHC but not investigated increases to 42.5 percent.

The problem may be even broader than these numbers suggest. Studies of police reports in Illinois and Los Angeles as well as a national sampling of victims indicate that at least 41 percent of victims who report an assault to the police do not get forensic exams. [13] If this trend holds true for D.C. as well, then we would expect the total number of incident reports at MPD to be significantly higher than the number of reports coming through the hospital. However, assuming the Washington Hospital Center data is correct, 436 victims had exams and reported to MPD in the 3 year period analyzed by Human Rights Watch (excluding 44 cases in which the victim reported to MPD at the hospital but did not have an exam). Over the same time period, MPD has 571 incident reports. [14] Even if all the hospital reports were accounted for at the MPD (as previously noted, at least 35.4 percent are not), the total number of reports at the MPD would still be far lower than expected. If approximately 41 percent of people who report to police do not have forensic exams, the number of MPD reports for sexual assault for that period would be expected to be 739 cases, not 571. [15]

Stopping the Investigation Before it Begins

The numbers alone present a disturbing picture, though they do not on their own explain why the MPD appears not to have documented all of the cases that victims reported to them. Some clues may be found in depositions taken in 2008 as part of a civil lawsuit against the MPD by a student whose December 2006 sexual assault case was closed without investigation. In those depositions, SAU detectives revealed that, at the time, they regularly failed to even write reports for cases when SAU detectives did not believe victims.

In May 2012, MPD Chief Cathy Lanier told Human Rights Watch that following the lawsuit she had transferred four detectives out of the SAU and developed a new policy for handling sexual assault cases. The new policy, which went into effect in August 2011, is nearly identical in substance to the previous policy (apart from changing the location of the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) program). It, and the changes that occurred after 2008, are acknowledged in this report. However, unless otherwise noted, all data collected and examples of improper police behavior referenced in this report occurred after these changes were adopted, and after a new program for conducting forensic exams for sexual assault victims in the D.C. area was established at WHC in late 2008. [16]

Despite the MPD’s reforms, the mismatch we found between victim reports at WHC and incident reports collected by the police suggests that some of the practices mentioned in the 2008 depositions continued well into 2011.

“Office Information” or “Miscellaneous” Cases

Human Rights Watch reviewed internal police files for 125 cases that were classified as “office information” (a category sometimes also called “miscellaneous”). These included 82, between 2009 and 2011, for which no case number was assigned and no incident report prepared. According to MPD procedure, an incident report is supposed to be prepared for cases classified as “office information,” but these cases are, according to the MPD’s official policies, “closed by definition.” [17] If further investigation is needed, it “should be classified as an ‘allegation’ and handled accordingly.” [18]

Classifying a report of sexual assault as “office information” is problematic for at least two reasons: one, because it shuts down investigations; and two, because “office information” classifications do not hide the victim’s identity, address, or phone number on the publicly available report, as is usual when a sexual assault is reported. [19] As a result, victims are potentially exposed to public identification.

Based on interviews with witnesses and a review of police files, the MPD appears particularly likely to disregard cases involving alcohol or drugs, or to document them as for “office information only.” [20] This practice suggests a lack of understanding or sensitivity among some MPD detectives to the fact that sexual assaults frequently occur at times when the victim has consumed substances such as alcohol or drugs. The victim’s consumption of such substances—or the victim’s confusion or inability to recall some events surrounding the assault—should not be a reason to automatically dismiss a case.

A few examples of “office information” cases found in police files include the following:

- In late 2011, after consuming a “double shot” of alcohol, a victim reported waking up to find an unknown male engaging in vaginal intercourse with her. She did not know where she was but took a taxi to the hospital for a forensic exam. According to police notes, the victim had bruises on her face, a laceration on her upper lip, and pain in her vaginal area. The victim could not recall the evening’s events after leaving a nightclub or indicate where the assault took place. The detective wrote, “At this time this is an allegation solely due to the fact there is DNA that will be transported to the forensic lab where a case number is needed for processing.” The detective suggested follow-up at the nightclub and hospital, but nine months later, there was no indication of any investigation in the file after the initial statement. [21]

- In early 2010, a student reported that she was forced to orally copulate a stranger in an alley after a night of drinking. Although the complainant had a forensic exam, the detective did not prepare an incident report or assign the report a case number, and there is no indication that the detective followed up on evidence obtained from the forensic exam. The document trail indicates nothing to suggest that the detective did any investigation or made any effort to find additional evidence or witnesses, yet the detective’s internal report concludes, “There is nothing to corroborate the complainant’s alleged allegations.” [22]

- A young woman was at a bar in February 2011 when an acquaintance brought her a drink. She remembers nothing after that, but the next morning friends found her with no underwear between two parked cars. According to people with knowledge of the case, the police told her that because she did not remember anything there was nothing to report. [23] Internal police investigation files confirm that police recorded the incident as “office information” because “no crime was reported.” The police advised the nurse they would not be taking any items collected from the victim because it was a “no report.” The detective notes say the detective “provided [the victim] with [my] business card and said to call if she needed police services.” Though the victim told the detective the next day that she would like to know what the police could do about her case, the case remained classified as “office information” and no indication of investigation was in the file. [24]

Downgrading or Omitting Sex Offenses

Another way in which a sexual assault report may fall through the cracks is by being classified as a non-sex offense or as a less serious crime.

MPD Chief Cathy Lanier correctly noted in her December 20, 2012, letter to Human Rights Watch that criminal charges are ultimately decided by the prosecutor’s office (in this case, the US Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia), which can upgrade or downgrade charges as appropriate.

However, police misclassification minimizes what happened to the victim and may have other consequences. For example, until June 2012, allegations and other miscellaneous types of cases were not referred to the MPD’s Victims Services. Misclassification also has implications for the public, which is entitled to know accurate information about local crime.

Because detectives put the offense with the most severe penalty first on the incident report, sexual assault cases may sometimes be listed as a second offense after burglary or another crime. However, in some cases, victims reported sexual assaults or attempted sexual assaults, but their crimes were categorized as some other type of crime and either not referred to the SAU at all or not investigated by the SAU as a sexual assault.

For example, a nurse’s report notes a case of a woman who in September 2010 was pushed into her apartment by a stranger when she tried to open the door. Her assailant threw her onto the bed, ripped her dress off, and lowered her leggings. The woman urinated on herself in fear and the suspect threw her against a wall, but did not continue with the sexual assault. According to a hospital report, MPD investigated the case as a simple assault and burglary rather than an attempted rape.[25] An October 2009 case in which the victim was handcuffed, driven to an undisclosed location, and sexually assaulted was categorized only as “kidnapping” with no reference to a sexual assault. [26]

MPD detectives also categorized several cases as “misdemeanors,” although they appear to be more serious sex abuse cases.[27] For example, one 2008 incident report classified as a “misdemeanor” indicates:

- The complainant reported that while walking on the street the suspect threw her to the ground, ripped off her underwear, pulled down his pants, made contact with her vagina (without penetration) and attempted to hold his hand over her mouth before fleeing. [28]

Another 2009 “misdemeanor” incident report reads:

- The complainant states that the suspect penetrated her vagina several times with his penis without her consent. The suspect then left the room. When the suspect returned, he slapped the complainant in the face and pushed her down on a mattress. The suspect then penetrated the complainant’s vagina with his penis again without her consent. The assault ended when the suspect masturbated on the complainant’s face and in her mouth. [29]

Administrative Closures or Exceptional Clearances

Even in cases that are documented and investigated, interviews with witnesses and a review of investigative files raise concerns about the thoroughness of the investigations. In over two-thirds of the 66 arrest warrant affidavit requests in files reviewed by Human Rights Watch the US Attorney’s Office rejected the requests, primarily on grounds that the case presented was “weak.” As a result, all these cases were counted as “administrative closures.” Of the 27 percent of cases (17 cases) that were approved, more than half were charged with misdemeanors or non-sex offenses. In other cities, studies indicate prosecutors press charges in more than half of cases (54.5 percent) presented for warrants, twice the rate seen in D.C.[30]

Human Rights Watch only reviewed 66 warrant requests, as this was not the focus of the research, so we cannot draw definitive conclusions from the data on warrant refusals. However, the high rate of refusal in the limited sample does raise concerns about possible overuse of exceptional or administrative clearances to close cases.[31] Under FBI crime reporting guidelines, “exceptional clearance” is supposed to occur in cases in which the suspect is known to police and enough information exists to support criminal charges (probable cause), but circumstances beyond law enforcement control prevent arrest (e.g., the suspect is deceased or already incarcerated). However, when a case has been presented to a prosecutor and rejected without an arrest, the MPD also considers the case cleared by exceptional means.

Because the FBI does not distinguish between cases cleared by arrest and cases cleared exceptionally when it publishes crime data from cities, a case closed without an arrest still appears as a case “cleared by arrest.”[32] This practice may explain the MPD’s unusually high clearance rate for rape. For example, in 2010, the MPD reported clearing 59.8 percent of its rape cases (110 of184 cases), well above the 40 percent average clearance rate for similarly sized cities. Yet in data it provided to Human Rights Watch, the MPD showed only 22 arrests for all sexual assaults in 2010, including 6 child abuse cases (which may be included in FBI data) and possibly other sex crimes which may not be included in FBI data (such as some misdemeanors and sex crimes with male victims).[33] In its response to Human Rights Watch about data concerns, the MPD indicated that its clearance rate was high because it included cases against female victims under 18. Yet this would not explain why MPD’s rates are so much higher than other cities, all of which also include juvenile cases. And in any case, an analysis exclusively of 2010 adult cases based on data provided by MPD to Human Rights Watch shows a clearance by arrest rate of 5 percent for all adult sex abuse cases, including misdemeanors, for 2010.

Police Mistreatment of Victims

Many victims, hospital staff, and others who work with victims said that they experienced or witnessed insensitive treatment by some MPD detectives when victims tried to report sexual assault. A number of victims said they felt that their experience reporting to the police was as bad, if not worse, than the assault itself.[34] Human Rights Watch documented the following re-victimizing or counter-productive behaviors among some MPD personnel:

- Questioning survivors’ credibility, including threatening victims with prosecution if they are found to be lying;

- Actively discouraging victims from reporting or undergoing a forensic exam;

- Asking victim-blaming or inappropriate questions;

- Requiring detailed interviews while the victim is traumatized;

- Failing to respond to victims seeking information about their cases or calling because their assailant is threatening them;

- A range of other insensitive treatment

Questioning Survivors’ Credibility

Victims and witnesses reported that some detectives made it clear they did not believe victims in a number of ways. In some instances they threatened victims with prosecution for false reporting. One detective, according to medical staff, told a victim, “If I find out you are lying, I will look you up and arrest you.”[35] A victim who reported an assault in April 2011 said she was told “no one would believe her” and that she was “lying” and “wasting their time.”[36] Others are more subtle. One victim, for example, reported that a detective rolled her eyes repeatedly while the victim told her what had happened to her in May 2011. A victim said of her experience with the MPD in the fall of 2009,

I’ll never be able to stop shaking my head at the fact that not only was he not supportive, he made me feel awful about myself by telling me it was nothing more than an issue that I got too drunk and was regretting a decision I made. It tore me up that he did not believe me and he made it clear to me that he didn't believe me. Traumatized is the word that I felt from the investigator, in some ways, it was worse than the event itself.[37]

Memory lapses are commonly associated with trauma,[38] but some detectives appeared to disbelieve victims if they were not able to remember elements of the assault.[39] For example, Julie M., a student at a local university, was assaulted on campus by a stranger after she had been drinking. She said that when police asked her to describe the assailant, she was unable to describe him in detail: “It was hard for me to remember it because I was trying to block out what he looked like.” She felt police did not believe her in part because she could not provide a specific description, and she said that police closed her case at the time she reported.[40]

Discouraging Forensic Exams and Reports

Hospital staff, advocates, and victims indicate that detectives have at times tried to convince victims not to report the assault or have a forensic exam. One observer estimated that in her experience, nine times out of ten a survivor’s decision not to report may be because of something police told the victim.[41]

Some detectives discourage reporting by indicating that they will have to inform loved ones about their behavior, stressing the serious consequences to the perpetrator of pursuing a case, or indicating it will take “years” to get forensic tests back.[42] Since 2008, police no longer have authority to decide whether or not a victim will receive a forensic exam. But detective files indicate that in 2010 and 2011 detectives still sometimes notified nurses in cases in which the victim was intoxicated that they would not “authorize an exam” or that “the [complainant] was not a victim of a crime.”[43]

Examples of police comments that have the effect of discouraging reporting and forensic testing include:

- When Dolores R. was assaulted as a student at a university in D.C. in 2009, she tried to get a sexual assault exam at her university hospital. Campus police called the MPD. She says that the SAU detective who came to the hospital told her she would have to transfer to another hospital to get an exam, that it was a long process, and perhaps she “didn’t want to go through all that.” Dolores recalls the detective implied she had to speak to the police to get a forensic exam, though Dolores wasn’t sure she wanted to report the sexual assault. Dolores later discovered that WHC was only down the street from where she was. Dolores said the detective also made it clear she had her doubts about Dolores’ story, and that it was not a strong enough case to hold up in court. Dolores did not report her assault or get an exam.[44]

- When one married victim, Laura T., attempted to report her assault in late 2011, she indicated the detective told her he would have to inform her husband in order to proceed with his investigation. “I then asked him please don’t and he said ok – and then he handed me a form to deny ongoing investigation [decline an investigation] so therefore I signed it.”[45]

The attitude toward victim reporting is apparent in a June 2009 email from one detective to another about a victim he met at the hospital while there for another case. The victim had initially not wanted to report, but had changed her mind and went to Washington Hospital Center for a forensic exam the next day. The detective at the hospital wrote,

I found out you dealt with her about 4 am Friday or Saturday morning … and she chose not to make a report. Something about a gang bang and being intoxicated…. Anyway, I think it was just an OI [Office Information]. However, she now feels differently and wishes to make a report…. She says her phone isn’t working but she can be reached … Sorry, BUT IT IS WHAT IT IS!!!!!!![46]

Victim-Blaming

Several survivors and people who work closely with survivors said that police often question victims or make comments in a manner suggesting the victim is at fault.[47] One medical professional said she heard police appearing to blame the victim with questions and comments that included, “You shouldn’t have been out so late,” “For God’s sake, why did you do that?” or “Why did you walk home by yourself after a few drinks?”[48] Survivors and witnesses reported the following other examples of victim-blaming remarks:

- Medical staff overheard a detective tell an 18-year-old runaway who was assaulted in the middle of the night, “You shouldn’t have been outside. This is what happens at two in the morning. What do you expect?”[49]

- Dolores R., a university student who police talked out of reporting her assault in 2009, said the detective asked her, “Why didn’t you scream? Why didn’t you call a friend? Why didn’t you call a cab?” Dolores said, “I did what I did and I can’t change that.”[50]

Another victim wrote in a 2009 complaint that a female SAU detective to whom she tried to report an assault told her that if someone did something to her that she did not like she “would say no or tell them to stop.” She said the detective also asked “if [she] didn’t want them to do it, why [she] didn’t stop them.” [51]

One victim filed a complaint that referred to “the confrontational, insensitive manner in which they questioned me,” which she said was “very degrading and humiliating.” She added:

They seemed to be questioning my integrity…. How could it be that detectives who are assigned to a sexual assault and violent crime unit [are] allowed to behave in this manner?… I felt as if I was assaulted on April 16, 2007, by police officers who swore an oath to serve and protect.[52]

Requiring Detailed Interviews While the Victim is Traumatized

A lengthy interview immediately after an assault may not be appropriate because of the possible effects of trauma on the victim.[53] Victims are frequently traumatized during the initial interview (particularly if it immediately follows the assault) and therefore may not be able to concentrate or act rationally. It may have been hours since the victims last slept and they may still be under the influence of drugs or alcohol. That is why best practices recommended by the International Association of Chiefs of Police suggest delaying a full interview except in exigent circumstances requiring an arrest or identification.[54]

Although MPD policy allows detectives to schedule a follow up interview with a victim after a forensic exam, in practice, detectives often take a detailed statement from the victim before allowing him or her to have a forensic exam. A follow-up interview is generally only scheduled later if the victim is physically incapable of talking at the hospital.[55]

One officer explained that detectives “really go into detail and sometimes they ask questions over and over again.” [56] Even if the victim is too incapacitated to communicate, the detectives do not always schedule an interview later. The result is that some victims choose not to report or undergo an exam and others fall through the cracks. For example:

- An April 2009 case in which the complainant reported that the subject tried to rape her but did not say how. The complainant was under the influence and had to be woken with an ammonia capsule to be interviewed at the hospital. The case was filed as “office information” because “The complainant did not report a sexual assault.” The police file contained no indication of follow-up with the complainant. [57]

- A victim who reported being assaulted by three men in Chinatown in 2010. According to an advocate, police spoke with her for hours at the hospital before her exam, asking her to repeat the story to different detectives. During that time she was not able to eat or drink. She finally decided not to have the exam as she did not want her family, who came to support her, to have to wait for her any longer.[58]

After receiving Human Rights Watch’s recommendation to allow victims at least one full sleep cycle prior to conducting a full interview, the MPD issued a memorandum in June 2012 affording victims 24 hours after a preliminary interview before being re-interviewed, except in urgent cases or when a delay would jeopardize the victim or other members of the public.[59] However, as of October 2012, a source at WHC told Human Rights Watch that they had not yet observed any change in the MPD’s interviewing practices.[60]

Unresponsiveness

Numerous people who have worked closely with victims for years said victims regularly complain that they do not hear back from MPD, despite calling the department or individual officers repeatedly.[61] This is true even when the victim has concerns for his or her safety. Shelly D., who reported an assault in October 2009, said getting the police to respond was “like pulling teeth” even after her assailant sent her several threatening messages. Her detective “did not even bat an eye.”[62] She ended up moving in order to avoid her assailant.

This lack of responsiveness reinforces victims’ perception that their cases are not taken seriously and is often upsetting to them.[63] This sentiment is reflected in one victim’s experience, which she described in a written complaint in November 2009, filed with the Office of Police Complaints:

Shortly after making the report I received threatening emails from one of the parties involved. I phoned the detective and left multiple messages regarding the emails. She never returned my phone call … In the past week I have left multiple messages for both Detective [] and her supervisor Detective Sgt. ---. I have heard nothing from the Metropolitan Police Department since filing the report, 3 months ago, despite countless phone calls.... If I did not know better I would think that they were persuaded not to pursue the case that I definitely want to pursue.[64]

Other Insensitive Behavior

Human Rights Watch obtained information indicating other types of insensitive behavior, apart from that discussed above, including:

- The response of the detective who interviewed Estella C., a 24-year-old student, who reported being assaulted orally and vaginally by an acquaintance in his truck in the spring of 2010. Estella drove herself to the police department to report the crime after the assault. According to Estella, the detective who interviewed her repeatedly asked whether the assailant was good at oral sex. Estella said the detective rolled her eyes while she explained what happened, made comments like “So you were into it,” and repeatedly said the incident did not sound like rape to her. [65] The detective also said that even though it “didn’t sound like a good case,” she was “still going to have to type it up.” [66] Estella said she eventually drove herself to the hospital for a forensic exam because she did not want to spend more time with the detective, who acted like taking her case would be inconvenient. [67]

- Rosa S. reported being abducted by two men wearing masks and raped repeatedly overnight before being released the next morning. According to her lawyer and a staff member of an organization who worked with her, the detective who interviewed her was very aggressive and asked, “You are only doing this to get immigration status, aren’t you?” [68]

MPD Response

Since receiving a summary of this report’s findings on May 30, 2012, the MPD has acted on several of the recommendations Human Rights Watch made at the time, and has taken steps to improve how it handles sexual assault cases. For example, the MPD has agreed to add treatment of victims as a factor in evaluating SAU detectives, to create a victim satisfaction survey, to increase supervision over sexual assault cases, to allow victims a sleep cycle before conducting a detailed interview with them (except in emergency situations), and to establish a multidisciplinary review of closed cases. The commander of the Criminal Investigations Division of the MPD included many of these recommendations in a June 12 memo to the SAU. On June 8, 2012, the MPD issued a reminder to all police that they are required to document every complaint of sexual assault.

The MPD’s introduction of the reforms noted above is a positive and welcome step. However, we remain concerned about other aspects of the MPD’s response to our findings, which has been extremely hostile and defensive in tone. In its initial response to a summary of the findings in June 2012, the MPD insisted that the issues raised in this report have “long since been addressed” and claimed that the Human Rights Watch investigation was “flawed” and “unsubstantiated.” In its December 20, 2012, response to a summary of our revised findings (which took into account additional information the MPD provided after our June 2012 exchange), Chief Cathy Lanier dismissed the findings as “nonsensical.” Her response stated that our finding about closure rates “exhibits misunderstanding, ignorance or purposeful misreporting” and insists that “HRW in its desire to draw public attention to themselves has used unsupported and erroneous information to attack MPD’s handling of sex-abuse cases” as part of an effort to “make a public spectacle” for “self-serving” ends.

In short, the MPD strenuously denies there is any problem with the handling of sexual assault cases, but is nonetheless willing to make some improvements to its policy. The MPD also objects to not being given a full copy of the report well in advance of its release.

The MPD’s hostile response is particularly troubling precisely because it runs counter to the very steps that it needs to take to address the problem. As previously noted, to meaningfully reform what appear to be persistent practices within the MPD requires that its leadership begin by acknowledging the existence of a problem and commit to addressing it in an accountable and transparent manner. A detailed response to various claims made by Chief Lanier about the report is available at http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/FactSheet_0.pdf.

Also of concern is the fact that, in meetings to discuss our findings, some amongst the MPD leadership have expressed repeated hostility toward not only Human Rights Watch, but also those who are perceived as cooperating with the report.

In the weeks after Human Rights Watch shared its findings with the MPD on May 30, we were troubled to learn of a few situations in which people or agencies that the MPD believes shared information with us or cooperated with our investigation experienced unexpected adverse actions from the Office of Victim Services (OVS) in the Mayor’s Office. (The deputy mayor for Public Safety and Justice in the Mayor’s Office oversees both the OVS and the MPD).

The director of the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) program at Washington Hospital Center had notified the OVS of her intent to leave the program shortly before the MPD was informed of the contents of this report. At the time, the OVS had asked her to train a replacement and stay until October 2012. But after the report’s findings became known, the OVS instructed security to lock her out of her office at the Lighthouse (the building where the SANE program is based). The OVS rescinded the offer for her to facilitate a transition, searched her emails, and questioned her and others in the forensic nursing program about their cooperation with this investigation. [69] In addition, the OVS instructed nurses not to speak with Human Rights Watch. [70] The OVS also asked nurses to sign non-disclosure agreements. [71] The OVS has also substantially cut funding for the D.C. Rape Crisis Center, which some in the MPD have associated with this report, in a number of areas since June.

Inaction and Its Impact

Insensitive police behavior can have devastating consequences.

Sexual assault victims whom police treat poorly when they report are more likely to develop Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).[72] Victims are also less likely to cooperate with the police investigation, significantly decreasing chances that the perpetrator will face justice.[73]

Poor treatment of victims also undermines public confidence in law enforcement and means other victims are less likely to come forward. As Susan said, “if this happened to a friend of mine, I’d tell her to think twice before talking to police.” Since sexual assault is already the most underreported violent crime (with less than 20 percent of victims nationally reporting incidents to the police), behavior that discourages reporting is a public safety concern.[74] Furthermore, failing to accurately report sexual assault misleads the public about crime rates in their communities and distorts public policy debates over allocating resources for law enforcement and victim services.

In addition, the decision not to investigate means that evidence may be lost or remain uncollected by police. [75] It can be demoralizing for nurses, and frustrating for advocates who fear that subjecting victims to a four-hour invasive exam to collect forensic evidence may do more harm than good. As one former advocate asked, “Would I really encourage my girlfriend to go through a kit and be re-traumatized if nothing is happening with the kit?” [76]

Failing to investigate sexual assault violates the United States’ obligations under international human rights standards, which recognize rape as a human rights abuse and require the US to protect women and men from sexual assault and rape, while respecting the dignity of victims.

The treatment of victims and handling of sexual assault cases described in this report also violate official MPD policies governing adult sexual assault investigations. These call for “unbiased investigation into all reports of sexual assaults” and require that those who investigate sexual assault complaints be “sensitive” to victims’ needs.[77] They also contravene Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for the SAU, which state that law enforcement has a “legal and moral obligation to thoroughly investigate reports of suspected sexual abuse and determine whether a crime has been committed,” and to conduct investigations in “a professional and sensitive manner.” The SOPs also state that detectives should realize that an investigation may have “a tremendous impact on the welfare of the victim” and on the successful prosecution of offenders.[78] However, it appears that the MPD is not vigorously enforcing these policies.[79]

Effective Approaches and Next Steps

Materials and information that Human Rights Watch gathered indicate that MPD uniformed officers do not receive training in the legal definition of sexual abuse in the District of Columbia, or in how to respond to complaints of sexual assault.

Moreover, SAU detectives do not receive specialized training in trauma or sexual assault investigations before joining the unit, which has no information in its Standard Operating Procedures on drug or alcohol facilitated sexual assaults, non-stranger cases, or the impact of trauma on sexual assault survivors. Detectives are not selected for the unit based on their suitability for handling these kinds of sensitive cases, although as of this writing, the chief of police advised Human Rights Watch that plans may be in place to address this problem. The MPD has conducted some training for detectives in the second half of 2012 and has applied for funds for additional training in 2013.

Human Rights Watch did not have data available to determine whether race or other factors impacted police handling of sexual assault cases.

Although no single police department handles cases perfectly, Human Rights Watch found that other US cities have a number of effective approaches to investigating sexual assault cases. These include a victim-centered approach to investigation that includes: requiring sensitivity to trauma issues during the interview, allowing victims one or two sleep cycles before an interview except in urgent circumstances, follow-up, referrals to victim services, creating a non-judgmental environment, and allowing victims to be accompanied by an advocate during police interviews. They also include proper training, and respectful collaboration with victim services providers in the community, such as nurses and rape crisis counselors.

Treatment of victims also should be a factor when evaluating SAU detectives. Most importantly, supervisors should ensure all calls for sexual assault cases are documented and all detectives are held accountable for failing to adhere to department policy. The key to any successful implementation of reform is commitment from leadership to thoroughly investigating these cases and treating victims properly. As one expert advised, “Don’t let training be a scapegoat for bad supervision.”[80]

Any attempt to remedy these serious problems should start with the District of Columbia and its MPD ensuring that every reported sexual assault case has a written record and is thoroughly investigated so that culprits can be identified and arrested. Although measures have been put in place for closer supervision of SAU detectives and the MPD states that “because of suggestions from HRW, MPD changed the reporting procedure and that public reports are taken on all cases,” stringent scrutiny by the Washington D.C. City Council and Mayor’s Office will be necessary to ensure that changes are implemented in a meaningful manner and sexual assault victims are taken seriously, unlike last time this problem was revealed in 2008. This should be done by an independent oversight body, which conducts regular external reviews of sexual assault investigation files and department records to ensure cases are not falling through the cracks.

A model for such a review system can be found in Philadelphia. In response to a series of Philadelphia Inquirer articles in 1999 revealing that the Philadelphia Police Department was misclassifying and failing to investigate sexual assault cases, the police commissioner invited advocacy groups to review its sexual assault cases. This review has occurred on an annual basis for over a decade and is regarded as successful by both police and advocacy groups. All stakeholders report that the practice has resulted in improved police investigations of sexual assault cases.

***

Human Rights Watch welcomes the MPD’s willingness to consider a number of its recommendations and the changes in its policies that have already occurred. Effective, durable, and systemic reforms are needed to supplement the improvements that have already taken place and support proper investigation of sexual assaults. Police and government officials need to demonstrate clearly to victims of sexual assault that their cases matter and will be taken seriously.

Recommendations

To the United States Congress

- Pass the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act (VAWA). While the bill never reached the President last year, separate versions of VAWA before both the Senate and House in 2012 funded training for law enforcement agencies on how to improve investigation of sexual assault cases and on how to appropriately treat victims. The bills also provided grants to help appoint victim counselors for the prosecution of sexual assault cases.

To the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division Advisory Policy Board

- For the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR), recommend collecting and publishing data separately for crimes law enforcement has “cleared by arrest” and cleared “by exceptional means.”

- Clarify in the UCR Handbook that “clearing by exceptional means” does not include cases in which a prosecutor has rejected a warrant request for insufficient evidence.

- Consider revising UCR data collection to include collecting data that would reflect prosecutorial outcomes in order to provide the public with more meaningful information on what ultimately happens to sexual assault cases reported in communities.

To the United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division

- Conduct an investigation into the MPD’s handling of sexual assault cases to determine whether it has engaged in a pattern or practice of conduct that deprives individuals of rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or US laws.

To the Council of the District of Columbia and the D.C. Mayor’s Office

- Establish a task force (including a nationally recognized expert on sexual assault investigations) to examine the MPD’s policies and practices for handling sex crimes cases and recommend changes to ensure all complaints of sexual assaults are documented and investigated and victims of sexual assault are treated appropriately. The task force should also examine the definition of sex abuse in D.C. to ensure it is in line with current standards.

- Pass legislation giving victims the right to have an advocate, victim specialist, or support person of their choosing present during law enforcement interviews and proceedings.

- Create a permanent independent oversight body tasked to conduct regular reviews of police sexual assault investigation files. The body should report publicly to the city council. It should include members representing civil society, such as groups that provide support services to victims.

- Ensure Victim Services within the MPD (which provides support, information, and referrals to sexual assault and domestic violence survivors) has adequate resources to expand support to the Sexual Assault Unit (SAU). Request regular reports on implementing recommended changes to handle sexual assault cases from the MPD as part of the council’s regular performance oversight hearings.

To the Metropolitan Police Department

To Improve Accountability for the Follow-Up on Sexual Assault Cases

- Include treatment of victims as a factor in evaluation of SAU detectives and follow-through on any complaint regarding how a case was handled by MPD. Victims, support persons, witnesses, or third parties should be able to lodge complaints. A supervisor should investigate complaints, with second-level review. Transfer out of the unit and, as appropriate, discipline detectives who are regularly the subject of complaints.

- Require responding officers to document all reports of sexual assault and require SAU supervisors (a sergeant or lieutenant) to compare call log sheets for sexual assault cases to PD-251s to ensure each report is documented.

- Require that supervisors ensure that forensic evidence kits and other relevant evidence are collected regularly.

- Assign all allegations to detectives for follow-up investigation, and require supervisors to review sexual assault allegations to determine whether they are being properly converted to sexual assault cases.

- Establish a tracking system allowing supervisors to monitor the reporting, clearing, and closing of all cases by each detective to identify potential problems.

- Establish regular multidisciplinary review of closed cases to discuss ways to improve the investigation and prosecution of sexual assault cases, as well as treatment of victims.

- Develop a system allowing victims to complete and submit victim satisfaction surveys for the MPD to review and respond to, in order to change responses to sexual assault based on input by survivors.

- Require a prosecutor to review all cases in which the perpetrator has been identified before it is closed.

To Treat Sexual Assault Survivors Fairly

- Protect the confidentiality of all victims reporting a sexual assault, regardless of the classification of the offense as a sex abuse offense, an allegation, or an “office information” (or “miscellaneous”) case, including cases in which sexual assault is not the “primary” charge.

- Give victims the option of having an advocate, victim specialist, or support person of their choosing present during law enforcement interviews or proceedings.

- Provide referral information for counseling for all victims who report sexual assault.

- Require detectives to provide victims with transportation from the hospital after a forensic exam unless he or she has made other arrangements.

- Provide all victims with a case number and the detective’s contact information and work hours. Tell victims to call 911 in an emergency.

- Require a detective or victim specialist to return calls from victims within one business day; work with victim advocates or Victim Services to keep victims regularly informed of the status of the investigation.

- If a decision is made not to prosecute, inform the victim in a timely and sensitive manner and, if appropriate, offer referrals to community resources for counseling.

- Develop an anonymous reporting system.

- Provide a comfortable and private place to interview victims at the SAU.

- Increase the role of victim specialists within the SAU to provide support and referrals to all sexual assault victims and help with practical arrangements.

- Except in urgent circumstances, allow victims at least one full sleep cycle before scheduling a follow-up interview by a detective.

- Include a former SAU member in upper echelons of MPD management or establish an advisor on sexual assault investigations for the chief of police.

- After implementing reforms, conduct public outreach to encourage members of the community to report sexual assaults and strengthen trust in the police.

- Regularly train all police officers and recruits to understand the realistic dynamics of sexual assault (including non-stranger cases and drug or alcohol-facilitated assaults), the effects of trauma, and proper treatment of victims.

- Train detectives to interview sexual assault victims appropriately using trauma-informed techniques and to understand the impact of trauma on victims of sexual assault; to investigate non-stranger and drug-facilitated sexual assaults; and how to document sexual assault using the language of non-consensual sex.

- In the selection of detectives for the SAU, take into account the detectives’ suitability for handling sensitive victim interviews and their ability to be open to understanding the realistic and evolving dynamics of sexual assault.

Methodology

This report is based on more than 150 telephone or in-person interviews, as well as documents produced for Human Rights Watch by the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), the Office of Victims Services (OVS) in the Executive Office of the Mayor of the District of Columbia, which oversees the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) Program at Washington Hospital Center (WHC), and other government agencies in response to public records requests.

Interviews in Washington D.C. and other major cities (for comparison purposes) were conducted with: sexual assault survivors, current or former police chiefs or commissioners, heads or former heads of sex crimes units, forensic nurses and former forensic nurses, national experts on police responses to sexual violence, rape victim advocates, sex crimes detectives, police officers, staff of sexual assault service organizations, doctors who work with sexual assault victims, university staff who work closely with assault survivors on campus, a judge, a defense attorney, a forensic toxicology expert, sex crimes prosecutors, attorneys representing sexual assault victims, government officials, counselors, journalists who have covered police handling of sexual assault cases in the District of Columbia and elsewhere, and staff of several local community organizations who work in some way with sexual assault survivors, including 10 community organizations in the District of Columbia.

Unless otherwise specified, the witnesses and victims interviewed all described incidents that occurred since the opening in October 2008 of the SANE program at Washington Hospital Center, the designated hospital for care of adult sexual assault victims in the District. SANE has seen service for sexual assault victims expand from one trained forensic nurse to a dozen certified forensic nurse examiners who are on-call 24 hours a day. The nurse examiners have extensive training in how to provide medical, forensic, and emotional care to sexual assault victims.

Most interviews were conducted individually and in private. Four group interviews were conducted: one with sexual assault survivors, another with volunteer advocates, and two with Sexual Assault Response Teams (SART) in Philadelphia and Kansas City (which have re-examined their approach to sexual assault cases in the past decade). No incentive or remuneration was offered to interviewees. Two interviews were conducted through email. An American Sign Language interpreter was used for two interviews.

Given the sensitive nature of the topic and confidentiality concerns expressed by many interviewees, all survivors’ names and other identifying details, such as the precise date and location of the interview, have been withheld, unless they specifically asked to be identified. All initials are randomly assigned pseudonyms. In some instances, the date of the interview has been changed to protect the identity of the source.

Some interviewees who work closely with law enforcement are identified in this report with pseudonyms due to their concerns that their comments would jeopardize relationships with police and negatively impact their ability to provide services to victims. However, not everyone was comfortable being interviewed, even with use of a pseudonym. Indeed, one expert in the field noted that an unanticipated result of the move to have law enforcement work more closely with community groups that support victims is that it has silenced potential critics of police behavior. Following the June 8 police response to our letter, a number of sources expressed additional concern about protecting their identities, so in some cases more general descriptions of their occupations have been used to obscure their identities.

In addition to interviews, we submitted document requests under the District of Columbia Freedom of Information Act to the MPD, the OVS, the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for the District of Columbia, and the Office of Police Complaints.

The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, the OVS, and the Office of Police Complaints cooperated fully with our requests for information about toxicology reports, number of people seeking sexual assault kits, and complaints about police handling of sexual assault cases.

The MPD initially failed to provide a complete or timely response to our request for information about policies and procedures relating to sexual assault, training materials, call records, and investigative material. The MPD’s response took over 12 months and excluded all investigative files relating to sexual assault apart from public incident report forms. After receiving our May 30, 2012, letter outlining our findings, and as this report was being prepared for press, the police supplemented their response with information that had been erroneously excluded from their initial response, but still did not include investigative files. That information was incorporated into the report and data analysis.

As part of its research, Human Rights Watch also reviewed deposition transcripts and discovery material from a 2008 civil lawsuit that had been brought against the MPD. Transcripts included testimony from a sexual assault survivor, a family member, a sergeant responsible for a squad of patrol officers, three patrol officers, and two detectives and two detective sergeants (supervisors) from the MPD’s Sexual Assault Unit (SAU). Some of those deposed have since been removed from the SAU and in August 2011, the MPD put in place a new policy for handling adult sexual assault cases. However, as noted above, the incidents described in this report primarily occurred between late 2008 and November 2011, when the primary research for this report concluded, after the time that the MPD indicates it undertook a number of reforms to address issues revealed in the police depositions.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed academic studies on the prevalence of sexual assault, incidence of false reporting, the effect of law enforcement’s response on survivors and the incidence of re-traumatization, the effect of having advocates present during police interviews, and the toxicology of drugs used to facilitate sexual assaults.

Finally, Human Rights Watch reviewed 10 training manuals and model policies for law enforcement handling sexual assault cases on issues such as interviewing techniques, reporting methods, and clearance methods.

On May 30, 2012, Human Rights Watch met with members of the MPD including Commander George Kucik, Lieutenant Pamela Burkett-Jones, Sergeant Ronald Keith Reed, and Tyria Fields, Program Manager for Victim Services. Information from that meeting is incorporated into this report.

At the meeting, Human Rights Watch notified the department of the findings in the report, provided a written summary of its contents, and gave the MPD an opportunity to respond.