Summary

Corruption is so pervasive in Nigeria that it has turned public service for many into a kind of criminal enterprise. Graft has fueled political violence, denied millions of Nigerians access to even the most basic health and education services, and reinforced police abuses and other widespread patterns of human rights violations.

This report analyzes the most promising effort Nigeria’s government has ever undertaken to fight corruption—the work of its Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). Soon after it was established in December 2002, the EFCC began pursuing corruption cases in a way that publicly challenged the ironclad impunity enjoyed by Nigeria’s political elite.

Since its inception, the EFCC has arraigned 30 nationally prominent political figures on corruption charges and has recovered, according to the EFCC, some US$11 billion through its efforts. But many of the corruption cases against the political elite have made little progress in the courts: there have been only four convictions to date and those convicted have faced relatively little or no prison time. Other senior political figures who have been widely implicated in corruption have not been prosecuted. At this writing, not a single politician was serving prison time for any of these alleged crimes. Despite its promise, the EFCC has fallen far short of its potential and eight years after its inception is left with a battered reputation and an uncertain record of accomplishment.

This report examines the EFCC’s record against high-level corruption and the reasons for its shortcomings. Human Rights Watch believes that in spite of myriad setbacks, a stronger and more independent EFCC represents Nigeria’s most promising avenue to make tangible progress in the fight against corruption in the near future. In large part, this is because the EFCC is the only Nigerian government institution that has posed a meaningful challenge to the impunity enjoyed by corrupt and powerful members of the political elite. This report explains pragmatic steps the Nigerian government can take towards that goal.

Most analysis of the EFCC has focused on the commission’s two very different leaders. Nuhu Ribadu, the EFCC’s first head, built the institution into what it is. The media-savvy and dynamic Ribadu regularly and publicly declared war on corrupt politicians. But his legacy was tarnished by evidence that his anti-corruption agenda was selective, dictated at least in part by the political whims of then-president, Olusegun Obasanjo. Ribadu was forced from office just two weeks after he tried to prosecute powerful former Delta State governor James Ibori, a close associate of Obasanjo’s successor in office, Umaru Yar’Adua.

Current EFCC chairman, Farida Waziri, who took over in 2008, was brought in to replace Ribadu. Critics allege that, under Waziri, the EFCC’s anti-corruption work has grown timid and lethargic in comparison with Ribadu’s tenure. Many leading activists and political figures have called for her removal and some have accused her of being corrupt.

Human Rights Watch believes that the character and capacity of the EFCC’s leadership is an important issue and calls for the allegations that Waziri has proven ineffectual to be investigated. But this report shows that in terms of tangible results, Waziri’s record against high-level corruption is comparable to Ribadu’s, and neither of them can claim much real success. The EFCC has secured only four convictions against nationally prominent political figures—one of those, Lucky Igbinedion, former Edo State governor, was given a sentence so light after pleading guilty that it made a mockery of his conviction.

Acts of spectacular incompetence have afflicted the EFCC under both Ribadu and Waziri. Most egregiously, the EFCC under Ribadu failed to appeal a 2007 legally tenuous court ruling that purported to bar the EFCC from investigating alleged crimes by former Rivers State governor Peter Odili. That ruling effectively derailed what could have been the commission’s most important case. Ribadu never publicly explained how or why this happened—and it was on his watch. For her part, Waziri says she has never looked into the reasons why the EFCC allowed that case to be derailed and has made no tangible progress in overturning the ruling in the case.

Not all of the EFCC’s failures are its own fault, however. There are enormous institutional hurdles to any honest effort to prosecute corruption in Nigeria. At a fundamental level, Nigeria’s political system continues to reward rather than punish corruption. When ruling party chieftain Olabode George emerged from prison in 2011 after serving a two-and-a-half year sentence following a landmark EFCC prosecution, he was treated to a rapturous welcome by members of Nigeria’s political elite including former president Obasanjo and then-defense minister, Ademola Adetokunbo. The message was unmistakable—proven criminality is no bar to the highest echelons of politics in Nigeria.

The courts can also be an obstacle to accountability. Most of the EFCC’s cases against nationally prominent political figures have been stalled in the courts for years without the trials even commencing. Nigeria’s weak and overburdened judiciary offers seemingly endless opportunities for skilled defense lawyers to secure interminable and sometimes frivolous delays.

In some EFCC cases, the appearance of judicial impropriety has also been striking. When the EFCC brought 170 criminal counts against former governor James Ibori, a judge sitting in Ibori’s home state threw out every single count—including evidence that Ibori paid EFCC officials $15 million in an attempt to influence the outcome of the investigation. The judge ruled that the EFCC had failed to produce a written statement by the man who allegedly conveyed the bribe corroborating their version of events and that the prosecution’s proffered eyewitness testimony would inevitably amount to “worthless hearsay evidence.”

Finally, Nigeria’s other anti-corruption bodies, the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) and the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB), have failed to compliment the efforts of the EFCC. On paper, both institutions have powers that in some ways outstrip those of the EFCC. Unfortunately, they have been ineffectual relative to their size and statutory power and have displayed little appetite for tackling high-level corruption. They need to be empowered with new leadership and prodded to live up to their mandates and complement the EFCC’s own work.

In April 2011 Nigeria held national elections. The polls were a significant improvement over previous elections but were still marred by allegations of ballot stuffing, the inflation of results, and election-related violence. Nonetheless, the elections were seen as an important stamp of legitimacy for incumbent president Goodluck Jonathan who until then had been both a state governor and Nigeria’s president without ever winning an election himself. Now it is time for President Jonathan to use his mandate to show that he is serious about breaking with the dysfunction and abuse that have characterized previous administrations. More than anything else, that means tackling corruption in a manner that is both impartial and effective. President Jonathan’s predecessors in office failed to do so. In May 2011 Jonathan signed into law the Freedom of Information Act that guarantees the public the right to access public records—an important step towards improving transparency in Nigeria.

Because corruption is at the heart of many of Nigeria’s most serious human rights problems, including access to justice, police brutality, violations of economic and social rights, Human Rights Watch has repeatedly called on the Nigerian government to do more to fight corruption and to bolster the capacity and independence of key anti-corruption institutions—especially the EFCC. This report builds on Human Rights Watch’s past work in Nigeria by examining the EFCC’s record in fighting corruption. It lays out an agenda the Jonathan administration should follow to bolster the EFCC, and other government institutions, to make progress in reducing corruption and its attendant human rights consequences—and they are steps that can and should be taken without delay.

The president should publicly state his commitment to break with the bad practices of past administrations in dealing with corruption, including executive branch interference with the EFCC’s operations; sponsor specific legislation to improve the independence of the EFCC; begin the long-term process of repairing and reinforcing Nigeria’s battered federal court system; take specific steps to improve the work of the ICPC and CCB; and investigate allegations of incompetence within the leadership of the EFCC.

Nigeria’s international partners also have a role to play. As revealed by diplomatic cables published by WikiLeaks, behind closed doors the United States government took a strong stand against apparent attempts to weaken the EFCC under the Yar’Adua administration. The US government also took the important, albeit belated, step to revoke the visa of former attorney general Michael Aondoakaa who was widely seen as having undermined key corruption cases. Comparable international pressure is needed from all of Nigeria’s bilateral partners to press the Jonathan administration to safeguard the EFCC’s integrity and implement the recommendations in this report.

Foreign donors, most notably the European Union, have provided substantial assistance in technical support and capacity building to the EFCC, but Nigeria’s international partners can help in more direct ways as well. Following the example of the United Kingdom in the case of former governor James Ibori, foreign governments should actively pursue corrupt Nigerian politicians who commit financial crimes within their jurisdictions. The EFCC could not successfully prosecute Ibori, but in the end he was not untouchable. In April 2011, the UK government managed to extradite him from Dubai to London where at the time of publication he sat in jail awaiting trial on charges of money laundering.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch has published several reports that examine the links between corruption and Nigeria’s myriad human rights problems.[1] Some of that work has examined the role of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) in particular. Since 2006 Human Rights Watch has carried out interviews and advocacy with EFCC officials, including Nuhu Ribadu when he was the commission’s chairman. Human Rights Watch also reported extensively on the controversial events surrounding Ribadu’s dismissal from office in 2008. This report draws on that broader foundation and is supplemented by material gathered during a two-week research trip by two Human Rights Watch researchers to Abuja and Lagos in February 2011.

During the February trip, researchers carried out in-depth interviews with current and former EFCC officials—both on and off the record—including current chairman, Farida Waziri; officials of the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) and the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB); Central Bank officials; members of the National Assembly with key oversight portfolios; members of the judiciary; lawyers; civil society leaders; and foreign diplomats and donor agency officials. They carried out 32 interviews in total. Human Rights Watch was also able to obtain court documents including judgments, motions on appeal, and transcripts of court proceedings for several EFCC cases against nationally prominent political figures. Those documents inform and in some cases are directly incorporated into Human Rights Watch’s analysis of those cases in the pages that follow.

Introduction: Corruption and Human Rights in Nigeria

At independence in 1960, many Nigerians believed their country was destined for greatness on the world stage. Instead, more than 50 years on, the country largely remains a “crippled giant.”[2] Corruption has turned what should be one of the country’s strongest assets—its vast oil wealth—into a curse. Rather than lead to concrete improvements in the lives of ordinary Nigerians, oil revenues have fueled political violence, fraudulent elections, police abuses, and other human rights violations, even as living standards have slipped and key public institutions have collapsed.[3] Former Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) chairman Nuhu Ribadu has estimated that between independence and the end of military rule in 1999, more than US$380 billion was lost to graft and mismanagement.[4] Endemic corruption has continued since then.[5]

Human Rights Watch has documented the role of corruption and mismanagement in depriving Nigerians of their basic human rights in several different contexts. This research showed how in Rivers State—one of Nigeria’s wealthiest states and biggest oil producers—embezzlement and mismanagement of public funds prevented tremendous resources from improving the dire state of basic health and education services during the administration of former president Olusegun Obasanjo.[6] Human Rights Watch has also documented the role of corruption in fueling the political violence and electoral fraud that have plagued Nigeria since the end of military rule.[7] These twin problems have claimed hundreds of lives and produced government institutions that are often ineffective and largely unaccountable to the people who depend on them. For example, Human Rights Watch research shows how corruption has helped transform Nigeria’s national police force from protectors to predators. Widespread bribery and extortion by rank-and-file officers, and a system of “returns” in which bribes are passed up the chain of command, have fueled abuses ranging from arbitrary arrests and unlawful detention to torture and extrajudicial killings. Bribery, embezzlement, and abuse of office by police officials have severely undermined access to justice for ordinary Nigerians and left the force with inadequate resources to carry out meaningful investigations.[8]

Corruption is at the heart of many of Nigeria’s most serious human rights problems, and Human Rights Watch has repeatedly called upon the Nigerian government to do more to fight corruption and bolster the capacity and independence of key anti-corruption institutions. This report builds on Human Rights Watch’s past work by examining the EFCC’s record in fighting corruption and making concrete recommendations on how to improve this institution as well as the government’s broader anti-corruption efforts.

Background and Context

Following the end of military rule in 1999, and in recognition of the widespread nature of corruption, the Nigerian government established the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) in September 2000 to combat public sector graft such as bribery and abuse of office by public officials.[9] The ICPC was intended to build on the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB), and its sister entity the Code of Conduct Tribunal, which was established in 1990 to enforce a code of conduct for public officials.[10] Neither institution proved effective in curbing rampant public sector corruption.

Amid pressure from the international community to address what then-president Olusegun Obasanjo referred to as the “corruption quagmire” in Nigeria, the Nigerian government established the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) in December 2002 with the National Assembly’s passage of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (Establishment) Act.[11] The agency, which was granted broad powers to investigate and prosecute economic and financial crimes, was intended primarily as a tool to fight crimes such as money laundering and advance fee fraud. Since its inception, the EFCC has grown into Nigeria’s largest anti-corruption agency, with an annual budget of US$60 million in 2010 and more than 1,700 personnel.[12]

The EFCC’s initial caseload reflected its intended focus. The institution proved especially effective in prosecuting cases of advance fee fraud (commonly known in Nigeria as “4-1-9” scams after the relevant provision in the Nigerian Criminal Code)—a crime that includes the pervasive email scams that are widely associated with Nigeria.[13] In December 2005 the EFCC made headlines when it successfully prosecuted the so-called “Brazil” case, involving an advance fee fraud scheme whose Nigerian authors duped a corrupt official at a major Brazilian bank into stealing about $242 million and giving most of it to them.[14]

The EFCC soon acquired a reputation for dynamism and efficiency that the largely toothless CCB and the vast but largely ineffective ICPC could not claim. While the EFCC’s mandate was not specifically crafted to target public sector corruption, it was written broadly enough to encompass it.[15] As the chairman of the Senate committee that oversees both the EFCC and the ICPC put it, the EFCC began pursuing cases of government corruption “principally because the ICPC was not performing.”[16]

The Rise and Fall of Nuhu Ribadu

In April 2003, then-president Olusegun Obasanjo appointed Nuhu Ribadu, an assistant commissioner of police, as EFCC’s first executive chairman. Ribadu was a charismatic figure who interacted well with the media and his public profile grew rapidly along with that of the commission’s work.

By late 2004, EFCC investigators began pursuing high-profile allegations of public sector corruption. The targets included several of Nigeria’s powerful state governors, and the commission pursued these investigations with considerable fanfare. In 2006, Ribadu famously told the Senate that the EFCC was investigating 31 of the 36 state governors for graft and identified by name some of the governors who would be prosecuted after they left office.[17] Ribadu’s public vows to hold corrupt politicians to account quickly turned him into one of the most recognizable and widely discussed public figures in the country.[18]

The EFCC’s investigators developed a reputation for ruthless efficiency, but critics complained that their successes grew from a willingness to flout the law and trample on the rights of suspects. EFCC officials allegedly carried out illegal searches and ignored inconvenient court orders. Some critics, including human rights activists and defense lawyers, complained that the EFCC used Nigeria’s horrible prison conditions as a way to obtain convictions—convincing courts to deny bail applications so that defendants would plead guilty rather than suffer in prison during lengthy trials.[19]

Some EFCC sources who worked for the agency at the time readily acknowledge that in some cases, they took the law into their own hands. One former EFCC official told Human Rights Watch:

Did we break the rules? Yes. You cannot fight corruption and go by the rule of law. Everywhere you look, it’s them. The elite, they have the courts, they have everything.… If you go by the rule of law you won’t achieve anything.… Because of the interest and passion we had, we saw a window and just broke in.[20]

The EFCC’s excesses did little to diminish its growing reputation. In 2005 the EFCC successfully prosecuted former inspector general of police Tafa Balogun. He pleaded guilty to failing to declare his assets, his front companies were convicted of money laundering, and the court ordered the seizure of Balogun’s assets, reportedly worth in excess of $150 million.[21] Even though he was only sentenced to six months in prison, the image of such a powerful political figure being hauled before a court in handcuffs stood in stark contrast to the impunity Nigeria’s political elite had come to take for granted.[22]

The EFCC’s record soon began to lose its luster, largely because of the apparent political selectivity in its operations. Many of the EFCC’s corruption cases seemed to be pushed forward or derailed according to the political agenda of then-president Obasanjo.[23] Such allegations grew to a crescendo ahead of the 2007 elections, when the agency presented a list of 135 “corrupt” candidates who it said should not run for office. The list was dominated by the president’s adversaries and included none of Obasanjo’s close allies, omitting even the handful of Obasanjo loyalists Ribadu had publicly accused of corruption in the past.[24]

Some EFCC sources who were with the institution at the time still deny that political pressure played any role in determining which corruption cases moved forward and which were set aside.[25] But others acknowledge that the problem was real. Rabe Nasir, head of the EFCC’s bank fraud and counterterrorism units until 2007 and until 2011, head of the House of Representatives committee responsible for overseeing the EFCC, told Human Rights Watch:

It was very obvious … that selectivity was there. Everything was according to the whims and caprices of the president. I believe that. I have always believed that. Obasanjo was so reckless he could have sacked Nuhu [Ribadu] immediately if he went against him, no matter how good his work was.[26]

Ribadu’s Downfall

In May 2007 President Obasanjo, along with many of the state governors, left office having reached their constitutionally mandated two-term limit. Ribadu followed through on his earlier pledge and, in July 2007, the EFCC filed corruption charges against a handful of the former state governors, who had lost their immunity from prosecution on leaving office. None of the governors was seen as a close ally of Obasanjo or the new president, Umaru Yar’Adua. But this was soon to change.

In December 2007 the EFCC stunned Nigeria by arresting James Ibori, the powerful former governor of Delta State, in the oil-rich Niger Delta. Ibori had presided over a state that had remained impoverished and dysfunctional under his watch despite massive inflows of oil revenue. Although Ibori was not seen as a close ally of Obasanjo, many Nigerians assumed him to be untouchable because of his close relationship to both Yar’Adua—whose campaign Ibori is widely believed to have financially backed—and Yar’Adua’s attorney general, Michael Aondoakaa.[27] The idea that a man as powerful as Ibori could sit in prison awaiting trial gave a momentary new surge of excitement and legitimacy to the EFCC’s anti-corruption campaign (Ibori’s case is discussed in more detail below).

But the already beleaguered Ribadu had overplayed his hand, and the move against Ibori sealed the end of his career at the EFCC. Less than two weeks after the EFCC charged Ibori, Ribadu was “temporarily” relieved of his post and sent to attend a ten-month training course at Nigeria’s National Institute for Policy and Strategic Studies.[28] Ribadu’s tenure at the helm of the EFCC was in fact over, leaving him and many other EFCC officials apparently stunned. “We did not anticipate the reaction,” one key Ribadu-era official told Human Rights Watch. “Either we did not read the mind of the president very well or we were naïve.”[29]

RIBADU: THEN AND NOWWhen you fight corruption, it fights back. – Nuhu Ribadu[30] After Ribadu’s abrupt removal from his post at the EFCC in January 2008, the Police Service Commission demoted him by two ranks,[31] and state security agents forcibly removed him from the graduation ceremony at the training course he had been ordered to attend.[32] The police command then ordered him to report for duty at the police zonal office with jurisdiction over Delta State, James Ibori’s home state. Ribadu challenged the legality of his demotion in court, but when he failed to report to his new post, the Police Service Commission dismissed him from the police force.[33] After several death threats and an apparent assassination attempt, Ribadu left the country in January 2009.[34] But his travails were not over. In November 2009 the Code of Conduct Tribunal ordered his arrest on allegations that he had failed to declare his assets.[35] After Goodluck Jonathan was sworn in as president following the death of Yar’Adua from natural causes in May 2010, and Jonathan’s removal of Michael Aondoakaa as attorney general, Ribadu returned to Nigeria. [36] The Police Service Commission, reportedly under pressure from the presidency, restored Ribadu’s rank and reversed his dismissal from the police force,[37] and the new attorney general withdrew the case against Ribadu at the Code of Conduct Tribunal, without any public explanation.[38] In Nigeria’s April 2011 elections, Ribadu stood as the presidential candidate of the opposition Action Congress of Nigeria. He finished a distant third behind incumbent president Goodluck Jonathan and former military dictator Muhammadu Buhari.[39] |

The EFCC after Ribadu

After a brief interim period under former Ribadu deputy Ibrahim Lamorde, President Yar’Adua appointed Farida Waziri as head of the EFCC in June 2008; she remains in the position at this writing. Waziri’s tenure has been a rocky one. Her many critics allege that she has been ineffective and incompetent; she has also been widely accused of having close relationships with corrupt political figures and of going slow on sensitive cases against powerful political figures.[40] But as the next section of this report details, any comparison of the anti-corruption records of Ribadu and Waziri yields a more complicated picture than Waziri’s critics might expect.

Comparing the EFCC’s Performance under Ribadu and Waziri

Even the EFCC’s critics generally agree that the agency has done a competent job of prosecuting apolitical financial crimes, especially advance fee fraud cases. By March 2011 the EFCC had arraigned some 1,200 people for advance fee fraud, securing so far more than 400 convictions.[41] That side of the EFCC’s work has continued apace under Waziri.[42]

Also under Waziri, the EFCC has shed new light on Nigeria’s scandal-ridden banking sector. Central Bank officials told Human Rights Watch that they had received “tremendous cooperation” from Waziri’s EFCC in their efforts to “sanitize the banking industry” and “rid the sector of criminals.”[43] In the most highly publicized of several EFCC banking cases brought under Waziri, former Oceanic Bank managing director Cecilia Ibru was sentenced to six months in prison and disgorged an astonishing 190 billion naira ($1.2 billion) after pleading guilty to several counts of bank fraud in October 2010.[44]

The EFCC has made important progress in recovering assets that are the proceeds of crime. According to Waziri, since its inception in 2003, the agency has recovered over $11 billion—of which some $6.5 billion has been recovered since Waziri took office in June 2008, most of which was recovered in the Central Bank’s overhaul of the banking sector.[45]

The EFCC’s track record on high-profile political corruption cases is more complicated. There is a widespread perception that while the EFCC’s anti-corruption agenda under Ribadu may have been politically selective, the work was nonetheless dynamic and effective—and that things have deteriorated considerably under Waziri.[46] One EFCC operative who has served under both Ribadu and Waziri lamented, for example, that “The tempo is no longer as it was before.… We are looking to management to carry out the kind of fight that was there before. We are doing a good job but you can’t compare it to the work being done under Ribadu.”[47]

Whether these perceptions are accurate or not, they are important. As Tayo Oyetibo, a senior lawyer who handled some cases for the EFCC under Ribadu, put it,

[Under Ribadu] fear of the EFCC was seen as the beginning of wisdom for political office holders and you could see the impact. Corruption was not eradicated but people looked over their shoulders before carrying out their corrupt activities. The question is: is that feeling still there today? That’s where you can draw the line between the EFCC then and the EFCC today. Perception is important—if people believe a policeman will chase them, they are less likely to commit a crime. There was a perception of efficiency, of the EFCC being active.… I haven’t seen that today. One cannot say that fear is there any longer.[48]

On the other hand, Ribadu’s critics argue that his supposed record of achievement in the fight against corruption was mostly smoke and mirrors. Outspoken Ribadu critic Festus Keyamo, who has led several EFCC prosecutions as outside counsel under Waziri, told Human Rights Watch:

Much of what has been said about Ribadu’s tenure at the EFCC has been largely [based on] perception rather than reality.… Ribadu was hailed because of his Gestapo tactics in bringing suspects to court. He handcuffed the suspects, sometimes they dragged them on the floor.… That is all [people] remember, but it’s bereft of statistics. The statistics are not so much different on both sides [Ribadu or Waziri].… So most of it has been all noise and no record to back it up.[49]

Waziri herself angrily denies that the EFCC’s anti-corruption work has deteriorated since Ribadu’s ouster, suggesting that her predecessor was more effective as a celebrity than as a prosecutor. “I don’t want to handcuff people and make news 24 hours a day,” she told Human Rights Watch. “I want my work to speak for me.”[50]

Prosecutions of Nationally Prominent Political Figures

Human Rights Watch has long argued that the most important measure of Nigeria’s anti-corruption record is its success or failure in prosecuting corrupt nationally prominent political figures. Corruption by high-level officials such as state governors who control vast financial resources directly impedes the provision of adequate health and education to Nigerians by diverting the resources that might otherwise flow to basic services. In a broader sense, high-level corruption in Nigeria is so widespread and so central to the day-to-day workings of government that it undermines the effectiveness of public institutions at all levels, from the national police to local government primary education authorities.[51]

By the same token, Human Rights Watch believes that the EFCC’s public challenge to the impunity enjoyed by abusive members of Nigeria’s political elite has been its most important accomplishment in the fight against corruption. Only by holding prominent officials to account for corruption can Nigeria’s government show that corruption will not be tolerated, and discourage officials at all levels from stealing public funds the country needs to provide for basic needs. The following pages examine the relative performances of the EFCC under Ribadu and Waziri in pursuing those prosecutions.

For the purposes of this report, Human Rights Watch considers “nationally prominent political figures” to include current or former state governors, federal government ministers, and members of the federal Senate or House of Representatives, as well as a handful of other political figures who can without any controversy be described as nationally prominent.[52]

At various times, Ribadu publicly claimed to be pursing investigations against an endless parade of important public officials.[53] These public statements generated continual headlines and contributed to an impression that the agency was fighting corruption on a thousand fronts at once. But in reality, the EFCC’s attempts to prosecute nationally prominent political figures have been characterized primarily by delay, frustration and failure—under both Ribadu and Waziri. The cases have generated far more headlines than convictions, and neither Ribadu nor Waziri can claim more than a handful of concrete successes.

Prosecutions

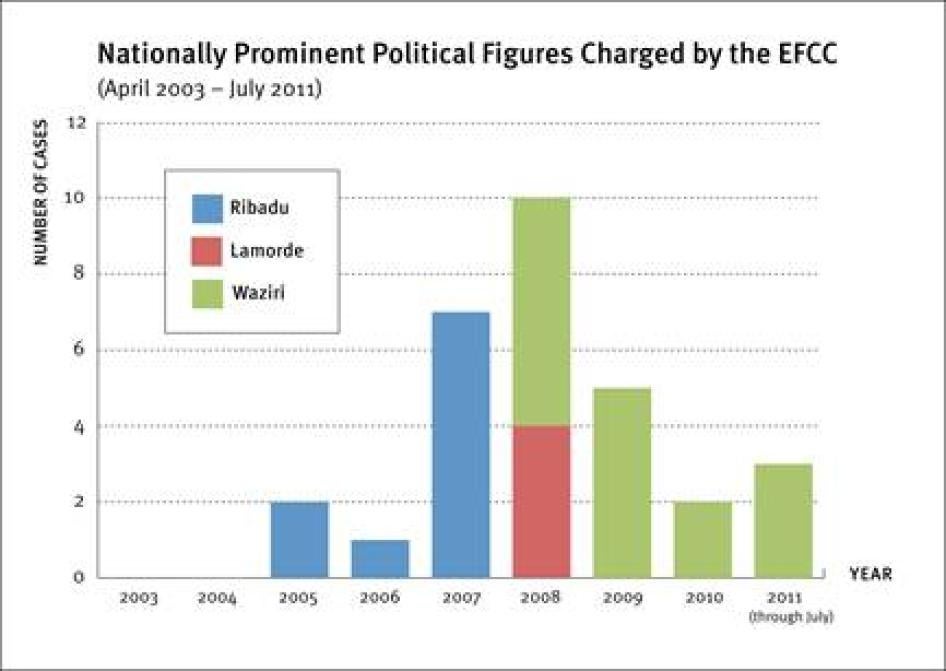

Waziri argued that the number of important cases she has filed compares favorably with Ribadu’s own record.[54] And in terms of raw numbers, she has a point. As the charts below show, the number of prosecutions targeting allegedly corrupt nationally prominent public officials is higher under Waziri (16 cases) than Ribadu (10 cases).[55]

There are at least two important caveats to this assessment. First, much of the investigation and other legwork for some of Waziri’s initial prosecutions was done before she took the helm.[56] A review of her record shows that there has been a significant drop in the number of new cases after those initial prosecutions. For example, during Waziri’s first year in office, the EFCC arraigned 10 nationally prominent political figures on corruption charges compared to just six in her next two years combined. On the other hand, in June 2011, Waziri stated that investigations against nine other former governors were at an “advanced stage.”[57] Second, the EFCC’s funding has tripled since 2007—its annual budget grew from approximately $23 million in 2007 to $60 million in 2010, without a commensurate increase in the rate of new prosecutions.[58]

Ten Nationally Prominent Political Figures Charged under Ribadu

(April 2003 – December 2007)

|

Defendant |

Office Held |

Date Charged |

|

Tafa Balogun |

Inspector General of Police (2002 – 2005) |

April 2005[59] |

|

Diepreye Alamieyeseigha |

Governor, Bayelsa State (1999 – 2005) |

December 2005[60] |

|

Abubakar Audu |

Governor, Kogi State (1999 – 2003) |

December 2006 [61] |

|

Joshua Dariye |

Governor, Plateau State (1999 – 2007) |

July 2007 [62] |

|

Orji Kalu |

Governor, Abia State (1999 – 2007) |

July 2007 [63] |

|

Saminu Turaki |

Governor, Jigawa State (1999 – 2007) |

July 2007 [64] |

|

Jolly Nyame |

Governor, Taraba State (1999 – 2007) |

July 2007 [65] |

|

Chimaroke Nnamani |

Governor, Enugu State (1999 – 2007) |

July 2007 [66] |

|

James Ibori |

Governor, Delta State (1999 – 2007) |

December 2007[67] |

|

Ayo Fayose |

Governor, Ekiti State (2003 – 2006) |

December 2007 [68] |

Four Nationally Prominent Political Figures Charged under Interim Chairman Ibrahim Lamorde

(January - June 2008)

|

Defendant |

Office Held |

Date Charged |

|

Lucky Igbinedion |

Governor, Edo State (1999 – 2007) |

January 2008[69] |

|

Iyabo Obasanjo-Bello |

Senator, Ogun State (2007 – 2011)[70] |

April 2008 [71] |

|

Adenike Grange |

Minister of Health (2007 – 2008) |

April 2008[72] |

|

Gabriel Aduku |

Minister of State for Health (2007 – 2008) |

April 2008 [73] |

Sixteen Nationally Prominent Political Figures Charged under Waziri

(June 2008 – July 2011)

|

Defendant |

Office Held |

Date Charged |

|

Babalola Borishade |

Minister of Aviation (2005 – 2006) |

July 2008 [74] |

|

Femi Fani-Kayode |

Minister of Aviation (2006 – 2007) |

July 2008 [75] |

|

Michael Botmang |

Governor, Plateau State (2006 – 2007) |

July 2008 [76] |

|

Boni Haruna |

Governor, Adamawa State (1999 – 2007) |

August 2008 [77] |

|

Rashidi Ladoja |

Governor, Oyo State (2003 – 2007) |

August 2008 [78] |

|

Olabode George |

Chairman, Nigerian Ports Authority (1999 – 2003)[79] |

August 2008[80] |

|

Nicholas Ugbane |

Chairman, Senate Committee on Power |

May 2009 [81] |

|

Ndudi Elumelu |

Chairman, House of Representatives Committee on Power |

May 2009 [82] |

|

Igwe Paulinus |

Chairman, House of Representatives Committee on Rural Development |

May 2009 [83] |

|

Jibo Mohammed |

Deputy Chairman, House of Representatives Committee on Power |

May 2009 [84] |

|

Attahiru Bafarawa |

Governor, Sokoto State (1999 – 2007) |

December 2009 [85] |

|

Abdullahi Adamu |

Governor, Nasarawa State (1999 – 2007) |

March 2010 [86] |

|

Nasir El-Rufai |

Minister of Federal Capital Territory (2003 – 2007) |

May 2010 [87] |

|

Hassan Lawal |

Minister of Works and Housing (2008 – 2010) |

May 2011 [88] |

|

Dimeji Bankole |

Speaker of the House of Representatives (2007 – 2011) |

June 2011 [89] |

|

Usman Nafada |

Deputy Speak of the House of Representatives (2007 – 2011) |

June 2011 [90] |

Convictions

In terms of pure numbers, the sum total of the EFCC’s convictions of nationally prominent political figures is underwhelming: a mere four convictions in eight years—between 2003 and July 2011. Only one of the four convictions was obtained at trial, with the others obtained through plea bargains that involved dropping some of the most serious charges against the accused.

Ribadu was no more successful in convicting nationally prominent political figures than Waziri has been, and both of the EFCC’s convictions under Ribadu were through plea bargain agreements. The one caveat is that seven of the cases against former state governors filed under Ribadu, and a number of the cases brought by Waizri, have been stalled in the courts by procedural delays and may yet result in important convictions.[91]

The EFCC’s Convictions

| TAFA BALOGUN: Former Inspector General of Police |

| Pleaded Guilty | Charged under Ribadu | Convicted under Ribadu |

Tafa Balogun was the EFCC’s first conviction of a nationally prominent political figure. Charged to court in April 2005, just months after being forced to retire as Nigeria’s inspector general of police, Balogun ultimately pleaded guilty of failing to declare his assets, and his front companies were convicted of eight counts of money laundering. In December 2005 he was sentenced to six months in prison and the court ordered the seizure of his assets—reportedly worth in excess of $150 million.[92] The sentence struck many as light given the severity of the allegations—he stood accused of financial crimes allegedly committed at a time when he was serving as Nigeria’s chief law enforcement officer.[93] Nonetheless, Balogun’s conviction was a profoundly important moment—the sight of such a prominent public official being hauled before a court in handcuffs to answer for corruption was something many Nigerians had thought impossible.[94] Balogun has since reportedly retired to a luxury home in a high-end Lagos neighborhood.[95]

| DIEPREYE ALAMIEYESEIGHA: Former Governor of Bayelsa State |

| Pleaded Guilty | Charged under Ribadu | Convicted under Ribadu |

Diepreye Alamieyeseigha served as governor of Nigeria’s oil-rich but deeply impoverished Bayelsa State from 1999 to 2005. In September 2005, he was arrested by British authorities in London. The London Metropolitan Police found about £1 million in cash at his home and charged him with money laundering.[96] Released on bail, Alamieyeseigha managed to flee the UK—the EFCC says disguised as a woman—and reappeared in his home state, claiming he had been transported there by God.[97] As a sitting governor he enjoyed immunity from prosecution in Nigeria, but three months later he was impeached by his state legislature, and the EFCC charged him with embezzling about $55 million in public funds.[98] In July 2007 the former governor pleaded guilty to failing to declare his assets, his front companies were convicted of money laundering, and the court ordered his assets seized. He was sentenced to two years in prison and released, for time served, the day after his sentencing.[99] Alamieyeseigha was quickly welcomed back into the ruling party fold. In May 2008 senior ruling party officials openly campaigned alongside Alamieyeseigha at a political rally in Bayelsa State, just 10 months after his conviction.[100]

| LUCKY IGBINEDION: Former Governor of Edo State |

| Pleaded Guilty | Charged under Ibrahim Lamorde (Interim Chairman between Ribadu and Waziri) | Convicted under Waziri |

Former Edo State governor Lucky Igbinedion was charged by EFCC prosecutors in January 2008 with siphoning off more than $25 million of public funds.[101] He ultimately pleaded guilty in December 2008 to failing to declare his assets and his front company was convicted on 27 counts of money laundering. But the trial judge in the case, Abdullahi Kafarati, deviated from the terms of the plea agreement and handed down a very light sentence that included no jail time (this aspect of the case is discussed in more detail below).[102] Igbinedion paid the equivalent of a $25,000 fine, agreed to forfeit some of his property, and walked free on the spot. The EFCC appealed the light sentence. In early 2011, the EFCC raided two of his palatial homes in Abuja and filed new criminal charges against the former governor.[103] But in May 2011 the court dismissed the case, ruling that the new charges would amount to double jeopardy.[104]

| OLABODE GEORGE: PDP chieftain and former Nigerian Ports Authority Chairman |

| Convicted at trial | Charged under Waziri | Convicted under Waziri |

Olabode (“Bode”) George was a powerful figure within the ruling party under President Obasanjo and was also chairman of the Nigerian Ports Authority (NPA) for a time. The EFCC in August 2008 charged him with contract-related offenses dating back to his time at the NPA.[105] In October 2009 he was convicted and sentenced to two and a half years in prison after a surprisingly swift and efficient trial.[106] This was the EFCC’s first and so far only conviction at trial of a major political figure—an important accomplishment. The positive example of his conviction was diminished, however, when he was treated to a rapturous welcome by key ruling party figures upon his release from prison in February 2011.[107]

Obstacles to Success

The EFCC has made some promising steps in tackling deeply entrenched impunity for political corruption in Nigeria. At this writing, 30 nationally prominent political figures had been arraigned by the EFCC on corruption charges in the eight years since the agency was established. But many of these cases have made little progress in the courts; there have been only four convictions to date and those convicted have faced relatively little or no prison time, and other senior political figures who have been widely implicated in corruption have not been prosecuted. The performance of the EFCC is continually undermined both by institutional factors beyond its control and failures of the commission’s own making.

The following pages describe what Human Rights Watch believes to be the most important impediments to the EFCC’s anti-corruption work, both systemic and self-inflicted.

Contextual Problems

A System that Rewards Corruption

If a law enforcement officer wants the work to be done, it will be done. But he may be denigrated, isolated, treated like a deviant. In Nigeria, crime does pay. Those doing this work are cut off from the system and are very unpopular among our colleagues and even in public opinion.

—Senior law enforcement official[108]

The broadest obstacle any effort to tackle corruption in Nigeria faces is this: the country’s political system is built to reward corruption, not punish it. Too often, corruption is a prerequisite for success in Nigeria’s warped political process. Since 1999, elections have been stolen more often than won, and many politicians owe their illicitly-obtained offices to political sponsors who demand financial “returns” that can only be raised through corruption. Put simply, the day-to-day functioning of Nigeria’s political system constantly and directly undermines the EFCC’s work.[109]

Powerful ruling party power-broker and former Nigerian Ports Authority chairman Olabode (“Bode”) George was sentenced to two and a half years in prison for contract-related offenses in 2009. His conviction after a swift and efficient trial was in many ways a landmark success for the EFCC.[110] But his case is also an example of the willingness of Nigeria’s political establishment to embrace convicted criminals.

Bode George was released from prison in February 2011. Far from being treated as a pariah because of his misdeeds, he was whisked from his jail cell to a lavish welcome ceremony attended by prominent ruling party politicians including former President Obasanjo, then-Ogun State governor Gbenga Daniel, and then-minister of defense Ademola Adetokunbo.[111] According to media reports, a former transportation minister even declared that George’s conviction had been unfair because all government officials engage in the same illegal practices he had been convicted of.[112]

Nigeria watched the ruling party establishment, including a sitting cabinet minister from the same administration that supposedly backs the EFCC’s anti-corruption agenda, welcome Bode George back into its arms as though he were a conquering hero rather than a convicted criminal. Meanwhile, the Lagos State judge who sent Bode George to prison was removed from criminal matters and sent to work in family court. While there is no proof that the move was connected to George’s conviction, many Nigerian activists and commentators found it hard to believe it was a coincidence.[113]

Bode George’s story is not an anomaly. Ten months after former Bayelsa State governor Diepreye Alamieyeseigha was convicted on corruption charges, Goodluck Jonathan, who was vice president at the time, and late president Yar’Adua openly campaigned alongside Alamieyeseigha in May 2008 at a political rally in Bayelsa State.[114] These images of senior government officials embracing convicted criminals only served to reinforce the broader trend of impunity that these convictions were meant to push back against.

Nigeria’s political establishment, both the ruling party and leading opposition parties, openly welcome into their ranks politicians accused of corruption. Joshua Dariye and Abdullahi Adamu, former state governors of Plateau and Nasarawa, respectively, have both been arraigned by the EFCC on corruption charges but won elections to the Senate in the April 2011 elections.[115] Two of the legislators awaiting trial on corruption charges—Igwe Paulinus and Ndudi Elumelu—also won their elections to seats in the House of Representatives.[116] Eight other former governors arraigned on corruption charges by the EFCC won party nominations to stand in the 2011 elections, either for governor or senator.[117]

Political Interference in Anti-Corruption Cases

In a purely structural sense the EFCC is deeply vulnerable to the whims of the presidency. The commission’s chairman enjoys no security of tenure and can be removed by the president at will, without any form of consultation or approval from the National Assembly.[118] And the political pressures brought to bear on the EFCC have at times been enormous.

The background section of this report described how allegations of political selectivity tarnished the EFCC’s reputation when President Obasanjo was in power, and how Ribadu’s attempt to prosecute James Ibori led to his removal from the commission.[119] After Ribadu’s ouster, the attorney general at the time, Michael Aondoakaa—reportedly Ibori’s close associate—seemed bent on undermining the very notion of a government-led war on corruption (see text box below).

AN ATTORNEY GENERAL’S WAR ON THE EFCCMichael Aondoakaa was attorney general in the Yar’Adua administration from July 2007 to February 2010. He was also reportedly a close associate of James Ibori, the disgraced former governor of oil-rich Delta State in the Niger Delta. During his time in office, Aondoakaa worked openly to undermine the independence of the EFCC and to derail domestic and international efforts to bring Ibori to justice. His strong-arm tactics earned him considerable notoriety. According to Ribadu, Aondoakaa “interfered” in many of the EFCC prosecutions and “destroyed cases relating to corrupt State Governors [by] discontinuing hearings and trials.”[120] According to leaked US State Department cables published by WikiLeaks in 2011, in 2008 Waziri told the US ambassador in Abuja that Aondoakaa had taken complete control over the EFCC’s case against Ibori along with other “politically sensitive” cases—something the attorney general technically had no clear power to do without formally removing the cases from the EFCC’s purview. In one such instance, one of the lawyers working on the Ibori case told Human Rights Watch that after the EFCC appealed a decision by the Court of Appeal transferring the case to Ibori’s home state—where Ibori still wielded enormous influence—the attorney general ordered the EFCC to withdraw the appeal.[121] Waziri even implored the US ambassador to “put pressure on” the attorney general to allow her to move the Ibori case forward.[122] Aondoakaa is also alleged to have interfered in the money laundering case against Ibori and his associates in the United Kingdom. After an English court froze $35 million of Ibori’s assets in August 2007, Aondoakaa provided Ibori’s lawyer with a letter stating that Ibori had been “investigated” in Nigeria and no charges had been filed, despite the fact that the EFCC was still investigating the case and finalizing criminal charges.[123] The letter led the English court to lift the freeze on Ibori’s assets.[124] According to leaked US State Department cables, Aondoakaa also refused to negotiate a broad prisoner transfer agreement with British authorities unless the UK dropped efforts to prosecute Ibori for money laundering.[125] According to the US embassy cables, Aondoakaa was “reputed to have done some of Yar’Adua’s dirty work, including attempts to disgrace former [EFCC] Chairman Mallam Nuhu Ribadu.”[126] Another leaked cable noted that while the Nigerian public and press had placed the blame for the EFCC’s perceived ineffectiveness solely on Waziri, “we believe … that Attorney General Michael Aondoakaa is the larger culprit on top of his everyday thuggery and illicit enrichment.”[127] The US government revoked Aondoakaa’s US visa in 2010 due to his “links to corruption,” but despite the wealth of evidence they had of his corrupt activities, they only took this action after he had left office.[128] |

Many of the sources interviewed by Human Rights Watch believed that political interference with the EFCC’s anti-corruption work was both inevitable and impossible to resist. As private lawyer and EFCC prosecutor Festus Keyamo put it,

You don’t go picking [arresting] a high-profile serving government official without clearing from the president. Whoever is the EFCC chairman, he can’t go beyond the wish of the president. If he does, he would be removed the next day.… At the end of the day, anyone who is the chairman of the EFCC will have to read the body language of Mr. President to do what he wants.[129]

On the other hand, despite the WikiLeaks revelations described above, Waziri asserted to Human Rights Watch that since assuming office she has never come under any sort ofpolitical pressure. She told Human Rights Watch that, “It has nothing to do with the presidency. I have not been prevailed on by the presidency to do anything on these cases.”[130]

This kind of alleged political interference is a problem for other anti-corruption institutions as well. In January 2011 Attorney General Mohammed Adoke announced that he was taking over a rare high-profile ICPC corruption case against the deputy health minister Suleiman Bello, without offering any explanation for the move.[131] “We brought the case and the attorney general just told us to drop it,” one ICPC official told Human Rights Watch.[132]

The attorney general has the power to take over or discontinue any prosecution from another federal agency if he believes it to be in the interest of justice.[133] In this case, the attorney general’s failure to provide any rationale for the move sparked widespread concern that his real aim was simply to quash the case.[134]

Judicial Inefficiency and Deliberate Delay

The EFCC Act grants jurisdiction to both federal and state courts to try EFCC cases.[135] According to the EFCC Act, special judges or courts should be designated to hear corruption cases,[136] and these proceedings should be “conducted with dispatch and given accelerated hearing.”[137] Despite these provisions, many of the EFCC’s cases have made little progress in the courts. Of the EFCC’s 12 ongoing prosecutions of former state governors, eight have already been dragged out for more than three years. Some have gone more than four years without a single witness being called at trial.[138]

With the exception of the Lagos State court system, no other state courts or judges in the federal system are designated to hear the corruption cases—and even in Lagos State the designated judges still have to hear cases involving other matters on their docket.[139] Most Nigerian courts are burdened with an antiquated physical and legal infrastructure that renders them extremely slow and inefficient. With the notable exception of the Lagos State court system, rules of evidence and procedure have for the most part been left practically untouched since colonial rule, with absurd results—most state courts, for example, still lack a formal mechanism to admit electronic documents into evidence.[140] Many judges must take their own notes in longhand while, in the words of one judge, they “sweat and choke” in stiflingly hot courtrooms—hobbling the speed of any proceedings.[141] The judiciary, including appellate courts, also strains under the burdens of an excessive caseload.

These and other factors conspire to create extraordinary delays. As one lawyer told Human Rights Watch, “Overworked judges want the opportunity to put off their work, so you get adjournments for the asking—and it always then takes about one to three months at least [to return to court] because the court’s calendar is always full.”[142] But the most extreme delays come from the court system’s backlog of appeal cases. Many judges halt trials while interlocutory appeals are decided by higher courts, and skilled defense lawyers can exploit this to generate months or even years of delays in any given case.

When former Kogi State governor Abubakar Audu sought a court order restraining the EFCC from prosecuting him in 2006, Federal High Court judge Mohammed Liman denied the application, noting that “I cannot be but horrified by the level of debauchery that was alleged to have been committed,” and he questioned the propriety of the former governor’s attempts to “use the instrumentality of the law to prevent his coming face to face with justice.”[143] But since being charged, Audu’s case has been crippled by interminable delays. In early 2011, after nearly five years of appeals and other stoppages, the trial was finally expected to commence—only to be postponed yet again when Audu was granted a delay for medical reasons. Critics doubted how ill the accused truly was; having declared his candidacy to regain the governorship of Kogi State, Audu was vigorously campaigning in spite of his infirmity.[144]

As Ricky Tarfa, a prominent lawyer who has defended several former governors accused of corruption by the EFCC and was himself once the subject of an EFCC investigation, put it, “A defense counsel has to take advantage of anything that might benefit his client.” If faced with an unfavorable case, he said,

I will advise my client not to rush to judgment.… The laws are skewed in favor of an accused person … once he’s granted bail he can drag out his trial forever. This is compounded by the fact that judges are bombarded with work, have no modern facilities, and no good assistance.[145]

JUSTICE DELAYED—THE JOSHUA DARIYE TRIALIn September 2004, British authorities in London arrested Plateau State governor Joshua Dariye on allegations of money laundering and seized about £90,000 in cash. Dariye skipped bail, fled to Nigeria and reassumed his office—which granted him immunity from prosecution.[146] An English court in April 2007, however, sentenced Dariye’s associate to three years in prison for laundering more than £1.4 million of public funds found to have been stolen by the governor.[147] Once the governor’s term ended in 2007, the EFCC quickly moved to charge him with 14 counts of money laundering.[148] But four years later, Dariye remains free and at this writing his trial had yet to begin. The EFCC’s frustrated effort to prosecute him is a perfect case study of the Nigerian courts’ ability to generate delays so extreme that they are almost a form of impunity. Soon after he was charged, the Federal High Court granted Dariye bail even though he had fled prosecution while out on bail in the UK.[149] In November 2007 Dariye’s lawyers then filed a motion asking that all of the charges against him be dismissed.[150] Justice Adebukola Banjoko denied the motion, but Dariye’s lawyers appealed the ruling. Banjoko halted the proceedings until Dariye’s appeal could be heard.[151] The Court of Appeal ruled against Dariye on every issue,[152] but by the time that ruling was handed down in June 2010, nearly three years had passed since Dariye had first been hauled into court. In December 2010 Dariye was back before the trial court and Banjoko stated that his trial would finally commence in January 2011. But Dariye’s lawyer immediately stood up to announce that he had filed an appeal of the Court of Appeal’s ruling with the Supreme Court. The court subsequently halted the proceedings again until that appeal could be heard. Rotimi Jacobs, one of the EFCC’s outside counsel on the case, told Human Rights Watch that given the backlog of cases faced by the Supreme Court, he thought the trial might not actually begin until sometime in 2013.[153] In April 2011 Dariye won election to the Senate; at the rate his trial has progressed so far, he might serve out his entire term before a final verdict is rendered in his case. |

These delays are not all inevitable. Section 40 of the EFCC Act purports to foster speedier trials in EFCC cases by barring judges from stopping trials to wait for appeals to be decided.[154] In theory, this provision is one of the most potent procedural weapons the EFCC has at its disposal. But EFCC officials say that many judges have simply refused to adhere to section 40, viewing their wide discretion to decide such matters as a constitutional guarantee that cannot be curtailed by legislation.[155] The EFCC Act also grants trial judges broad powers to take appropriate measures to ensure speedy trials and avoid delays in EFCC cases, but with some exceptions the courts have not made any apparent use of those powers.[156]

Some EFCC officials feel that the only way they can avoid crippling judicial delay is to convince trial courts to deny the accused bail. The two convictions secured by the EFCC under Ribadu were obtained through plea bargains after the accused had been denied bail. If the accused are suffering in detention, the logic goes, they will be far less eager to postpone their trials. Festus Keyamo, a lawyer prosecuting cases for the EFCC, told Human Rights Watch that, “Give me those governors, put them back in prison, refuse them bail [and] I’ll get convictions in six months. All of them. It’s as simple as that.”[157]

The EFCC, under both Ribadu and Waziri, has opposed bail in virtually all the corruption cases, but unlike the early cases brought by Ribadu, the courts now grant the accused bail. At this writing, of the 24 cases of nationally prominent political figures awaiting trial, all of the accused were free on bail.

Concerns About Judicial Impropriety and Corruption

The former governors have tremendous leverage over the system. I don’t know if they had judges in their pockets, but I do know the system was on their side.

—Olisa Agbakoba, lawyer and former Nigerian Bar Association president[158]

Courts in Nigeria have stood up to roll back abuses of government power more frequently and effectively than any other institution. For example, courts stripped 12 ruling party governors of their seats after Nigeria’s fraud-riddled 2007 elections. But Nigeria’s vast judiciary is a mixed bag, and some courts have been tainted by allegations of corruption or succumbing to political influence.

For example, the reputation of Nigeria’s court system took a beating in February 2011 when Ayo Salami, the president of the federal Court of Appeal, publicly accused Supreme Court chief justice, Aloysius Katsina-Alu, of trying to pressure him to decide a key electoral petition in favor of the ruling party.[159] It did not help matters that Mary Odili, wife of notorious and allegedly corrupt former Rivers State governor Peter Odili, was elevated to a Supreme Court seat the same month.[160] Not long after, leaked US State Department cables revealed that Dimeji Bankole, at that time Speaker of Nigeria’s House of Representatives, claimed to US diplomats he had proof Supreme Court justices had taken bribes to validate Umaru Yar’Adua’s election as president in 2007.[161] More recently, in the run-up to Nigeria’s 2011 polls, lower court judges handed out an unprecedented number of election-related injunctions to various candidates for office. The blizzard of injunctions was so dense that many critics suspected some judges were essentially offering them up for sale.[162]

The temptation to give in to graft is especially high in cases involving wealthy political figures on trial for corruption. Human Rights Watch has not seen concrete evidence of judicial corruption in any of the EFCC cases, but there are at least three high-profile EFCC cases where the appearance of judicial impropriety has been striking.

The Case of Former Rivers State Governor Peter Odili

In March 2007 then-Rivers State governor, Peter Odili, obtained a remarkable Federal High Court decision forbidding the EFCC from investigating the finances of his government. After Odili left office, he managed to secure a “perpetual injunction”—widely condemned as a mockery of the judicial process—that permanently restrained the EFCC from “arresting, detaining and arraigning Odili on the basis of his tenure as governor.”[163] The decision was widely denounced as without any legal basis and its author, Justice Ibrahim Buba, became a widely reviled figure in the Nigerian press. The Odili case, which the EFCC bungled in spectacular fashion, is discussed in more detail below.[164]

The Case of Former Edo State Governor Lucky Igbinedion

In December 2008, EFCC prosecutors reached a plea bargain agreement in the trial of former Edo State governor Lucky Igbinedion, who was charged with various counts of money laundering involving about $25million in state government money. According to attorney Rotimi Jacobs, who prosecuted the case, the agreement stipulated that Igbinedion would plead guilty to several counts, and the judge would sentence him to at least six months in prison and order the former governor to forfeit three illicitly-acquired Abuja properties.[165]

On the day Igbinedion’s sentence was handed down, prosecutors received a rude shock. Deviating from the terms of the agreement, the Federal High Court judge, Abdullahi Kafarati, sentenced Igbinedion to a paltry 3.5 million niara (about $25,000) fine instead of prison time and ordered his assets seized. Igbinedion walked free the same day of his sentencing after reportedly paying the fine on the spot, in cash.[166] The fact that Igbinedion had the right amount of cash on hand gave rise to suspicions that he knew what his sentence was going to be before it was handed down. “Only God knows what happened behind the scenes,” Jacobs said. “[But] he had brought the cash to court, which means he had pre-knowledge.”[167]

The Case of Former Delta State Governor James Ibori

Still more jarring was a federal judge’s December 2009 dismissal of all 170 criminal counts against powerful former Delta State governor James Ibori—without allowing the prosecution to present any of its evidence at trial.[168] The case was heard in Asaba—capital of Ibori’s home state—after the former governor’s lawyers won a court order that overturned established precedent by moving the trial there from Kaduna.[169]

In dismissing the charges against Ibori, Federal High Court judge Marcel Awokulehin held that despite submitting over 1,000 pages of documentation, the prosecution had failed to establish a prima facie case of even one instance of criminal wrongdoing by Ibori or his six co-defendants. Considering the allegations at issue, the decision was baffling. One count of the indictment alleged that Ibori had given then-EFCC chairman, Ribadu, a $15 million bribe in an attempt to get the case against him dropped. Ribadu had handed $15 million in cash over to the Central Bank of Nigeria for safekeeping as evidence, alleging that this was the money Ibori had bribed him with.

Ribadu claimed that Ibori arranged for him to collect the money at the home of powerful People’s Democratic Party (PDP) politician Andy Uba. The prosecution presented the court with witness statements by Ribadu and two other EFCC officials alleging that they went to Uba’s house and collected the money as instructed. But Justice Awokulehin held that the prosecution’s case on this count would inevitably consist entirely of “worthless hearsay evidence” because Uba had not provided them with a written statement confirming that he had tried to bribe Ribadu at Ibori’s request.[170] In February 2011 Central Bank officials confirmed to Human Rights Watch that Ribadu had given the Central Bank the $15 million and that it remained in their possession.[171] The EFCC has since appealed Justice Awokulehin’s dismissal of the case.[172]

$15 MILLION BRIBE TO STOP AN INVESTIGATIONIn a signed witness statement for British anti-money laundering investigators in their case against former Delta State governor James Ibori, former EFCC chairman Nuhu Ribadu describes receiving a $15 million bribe from Ibori on April 15, 2007—one month before Ibori left office and lost his immunity from prosecution—to drop the corruption investigation against him: We were talking and engaging with James [Ibori] throughout the investigation. He stated that he wanted to give me money to stop the investigation. I wanted to make him feel comfortable, so I did not refuse his offer.… He did not want to come to our offices and I didn’t want to go to his house and I did not want to him to come to my house. He stated that he would make the money available to me at Andy Uba’s house in Abuja. At the time Andy Uba was Special Advisor to President Obasanjo. I briefed my colleagues at the EFCC, about everything that was going on. On the day that James said that he was going to give me the money, I told my colleagues and we went to Andy Uba’s house. My staff on that occasion would have included EFCC Head of Operations, Ibrahim Lamorde and EFCC Head of Unit and EFCC Officer James Garba. James (Ibori) was there and his servant or diver brought out the money from the house, in two (2) massive sacks containing US$100 dollar bills. My staff took possession of the money.… I told my staff to take the money to the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) directly that same afternoon, where it was counted and lodged as an exhibit. The total amount that James gave me was exactly US$15 million. James was not aware that the money had been taken to the CBN, I was of the view that James thought that I had taken it personally and possibly shared it with my own staff. At the time that he gave me the money James was immune from prosecution, so I could not arrest him. I did not tell him that I had banked the money, because I did not want him to flee the country. The first time that he would have realized that the bribe had not been successful was when he was arrested.[173] |

The EFCC has filed more than 25 complaints against judges for various delays in the corruption cases, granting “frivolous injunctions to halt trials and investigations,” and “partisanship”—including to the National Judicial Council, an independent constitutional body responsible for oversight and discipline of members of the judiciary—but, according to the EFCC, little has been done other than, in a few cases reassigning the case to a new judge.[174]

The EFCC’s Own Shortcomings

Error and Incompetence

While the EFCC certainly faces an array of external obstacles to its work, the agency has also managed to damage some of its own prosecutions through error and incompetence. Under Ribadu, the EFCC was sometimes criticized for its penchant for high-profile arrests and public “invitations” of prominent suspects to come in for questioning before criminal investigations were complete. While these tactics earned headlines and may have struck fear into the hearts of some corrupt public officials, critics worried that they also undermined the underlying investigations. As one judicial official put it, “The day you make an announcement to the media [should be] the day you have filed a case—otherwise you are just saying, ‘hide your tracks, we are coming.’”[175]

The Peter Odili Case: Gross Incompetence or Worse?

The EFCC’s failure to prosecute former Rivers State governor Peter Odili (in office from 1999 to 2007) stems from severe incompetence for which officials have failed to offer any plausible explanation. Odili was a close ally of former president Olusegun Obasanjo. His tenure in office was marred by widespread evidence of corruption, mismanagement, organized political violence, and electoral fraud.[176]

By 2006, then-chairman Ribadu told Human Rights Watch that the EFCC had amassed a vast criminal case against Odili.[177] And in 2007 Ribadu reportedly helped derail Odili’s vice-presidential ambitions by presenting some of that evidence to Obasanjo in a dossier that detailed evidence of fraud and corruption against Odili.[178] However, the EFCC has never charged him.

In March 2007, Odili obtained a stunning court judgment from Federal High Court judge Ibrahim Buba. Not only did Justice Buba order the EFCC to immediately desist from any investigation of the finances of Rivers State, but he ruled that the EFCC had no power to “in any manner howsoever investigate the account or financial affairs of a State government.”[179] The ruling not only purported to restrain the EFCC from investigating Odili, but if taken to its logical conclusion, would restrain the agency from investigating alleged crimes on the part of any current or former state government official. It called into question the very existence of the agency’s anti-corruption campaign. Buba’s ruling in the Odili case has been widely disparaged by legal experts and civil society activists as a brazen and indefensible departure from the letter of the law. “You can’t just give someone perpetual immunity from investigation,” one judicial official told Human Rights Watch. “It’s criminal.”[180]

According to legal experts interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the EFCC had two clear options: appeal the ruling, or simply proceed to charge Odili to court and then argue that Buba’s ruling was of no validity if Odili sought to raise it as a defense.[181] Instead, the agency did absolutely nothing and effectively let the investigation die. In March 2008, “for the avoidance of doubt,” Buba issued an order that the EFCC could not “arrest, detain, arraign and/or prosecute [Odili] on the basis of its alleged investigations into the affairs of Rivers State” during Odili’s tenure, and declared that the “purported findings” of the EFCC’s investigations were “invalid, unlawful, unconstitutional, null and void.” For good measure, the judge also barred the EFCC from publicizing or disseminating the findings of the investigation Buba purported to throw out.[182] Although the EFCC in March 2008 publicly stated that it had completed its investigation into Odili’s “wanton looting of the treasury of Rivers State” and was ready to arraign him on corruption charges,[183] the commission failed to appeal this injunction as well.

Ribadu, who was still head of the EFCC when the 2007 judgment was handed down, has never publicly explained why he did not fight Buba’s ruling. Ibrahim Lamorde, who was interim chair of the EFCC when Buba handed down the 2008 injunction, has never publicly explained why he did not contest that either. When asked whether she had looked into the reasons for the EFCC’s inexplicable failures on the Odili case, current chairman Waziri said only, “I really, really don’t know what happened then.”[184] Another EFCC official claimed to Human Rights Watch that through some unexplained error, the EFCC was never even aware that the 2008 injunction had been issued until the time to appeal it had expired. “I don’t know what happened,” the source said. “By the time we went to court it was late or something.”[185] These professions of total ignorance are hard to fathom considering that this was one of the EFCC’s most important cases.

In February 2011 Waziri told Human Rights Watch that the EFCC’s criminal case against Odili is strong enough to take to court and is held back only by Buba’s ruling. The agency has retained outside lawyer Ado Balarabe Mahmoud to try and overturn it. The EFCC appealed Buba’s 2007 judgment in October 2008, but at this writing it had not yet been heard by the federal Court of Appeal.[186]

Allegations of Poor Leadership

Rightly or wrongly, current EFCC chairman Farida Waziri is widely considered ineffective. Leaked US State Department cables quote then-House of Representatives speaker, Dimeji Bankole, as telling US diplomats that he had no confidence in Waziri’s leadership or integrity and that the EFCC was not worth “one penny” since she had taken over.[187] Rabe Nasir, until 2011 head of the House of Representatives committee responsible for overseeing the EFCC—and himself a former EFCC official and Ribadu supporter—said the president must “do away with that woman. If he doesn’t, forget about fighting corruption in this country.”[188]

Some of the bitterness towards Waziri is attributable to the circumstances of Ribadu’s ouster, a fact she herself is keen to emphasize. “I was a victim of circumstances because I came in when the former chairman was being forced out among such controversy that it rubbed off on me,” she told Human Rights Watch. “People looked at me like I was part of the conspiracy.”[189] Or as one former EFCC official who was forced out after Ribadu’s ouster put it, “the forces that sent all of us out are the same forces that brought Waziri in.”[190]

Soon after taking over the chairmanship in June 2008, Waziri forced out roughly a dozen of the EFCC’s most experienced and highly trained personnel as part of a purge of as many as 60 staff in total. Nearly all were police personnel who had been seconded to the EFCC, including some who had received significant specialized training by the US government.[191] A private US government demarche to the Nigerian authorities (later made public by WikiLeaks) expressed concern that the redeployments would leave “a shell of inexperienced replacements at best in most areas, wasting considerable United States government and international training, threatening the EFCC’s institutional integrity, and jeopardizing cooperation efforts.”[192]

Waziri claims that she had the individuals redeployed because they were working openly to undermine her position. “In a sensitive organization like this, loyalty is key,” Waziri explained to Human Rights Watch. “You are trying to set up an office and the people working for you are not just disloyal, they are sabotaging.”[193]

The treatment of some key Ribadu’s deputies smacked of retribution, however. Ibrahim Magu, the former head of the Economic Governance Unit—responsible for all of the EFCC’s cases against political figures—was locked in a cell in the basement of police headquarters for nearly three weeks in August 2008, accused of failing to hand over documents relating to key prosecutions. Several other officers were redeployed by the police to remote postings where none of their considerable investigative skills would likely be put to use.[194] A few were posted to states whose governors they had personally investigated for corruption and still wielded enormous power.

By August 2008, the US government had become worried enough to send the Yar’Adua administration a written demarche expressing concerns about the state of the EFCC and asserting that the institution had “turned out to be a disappointment.”[195] In March 2009, Nigeria’s foreign minister tried to arrange a surprise meeting between the EFCC chairman and the US ambassador by inviting Waziri to what had been billed as a one-on-one lunch with the ambassador at his home. This was an attempted end-run around the US government policy of expressing its alarm at the state of the EFCC, and Waziri’s record as chairman, by refusing to grant her high-level meetings. The ambassador threatened to walk out, and the foreign minister agreed to tell Waziri that she would have to go.[196]

Leaked US government cables also reveal growing impatience with Waziri’s perceived ineffectiveness on the part of other donors, including the United Kingdom, Germany and The Netherlands—though the US government was alone in cutting off high-level contact with and assistance to the EFCC. Key European Union and United Nations representatives expressed relatively optimistic views, urging other donors to give Waziri a chance. US diplomats wrote off this optimism as insincere, speculating “it is more likely that … [it] may reflect these international organizations’ need to defend the success of their projects rather than their actual faith in the EFCC.”[197]

In December 2010 many observers were surprised when Ibrahim Lamorde—a prominent former Ribadu deputy—was brought back to the EFCC as director of operations. The move was widely seen as a prelude to Waziri’s ouster and replacement by Lamorde, but as of the time of writing Waziri remained in office.[198]

Allegations of Corruption

Waziri’s reputation has been further damaged by widespread rumors that under her watch, EFCC operatives have themselves become increasingly implicated in corrupt practices and extortion of criminal suspects and victims alike. Human Rights Watch has seen no concrete evidence of this alleged wrongdoing, however. For example, Rabe Nasir, former head of the House of Representative committee that oversees the EFCC, alleged that there is “pervasive corruption” in Waziri’s EFCC. As examples he cited having received numerous petitions from fraud victims who explained how they had approached the EFCC for help only to have its operatives demand a large cut of any assets ultimately recovered.[199] He declined to provide these petitions to Human Rights Watch, however, or to explain what he intended to do with the information.