Unjust and Unhealthy

HIV, TB, and Abuse in Zambian Prisons

Map of Zambian Prisons Visited

Fact Sheet

Table 1: Basic Statistics for Prisons Visited

|

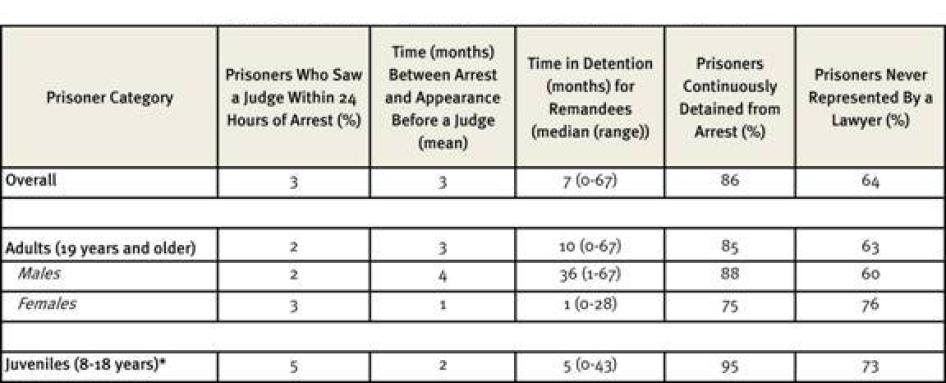

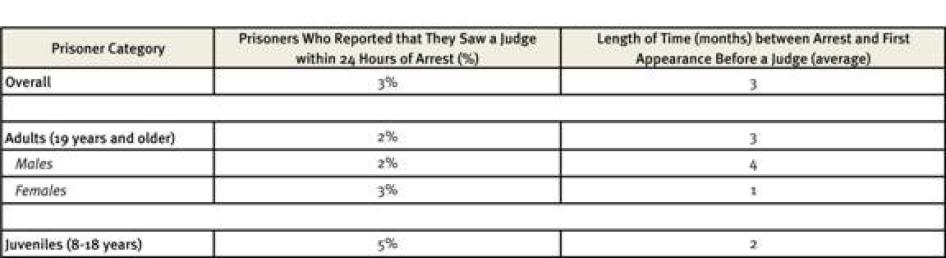

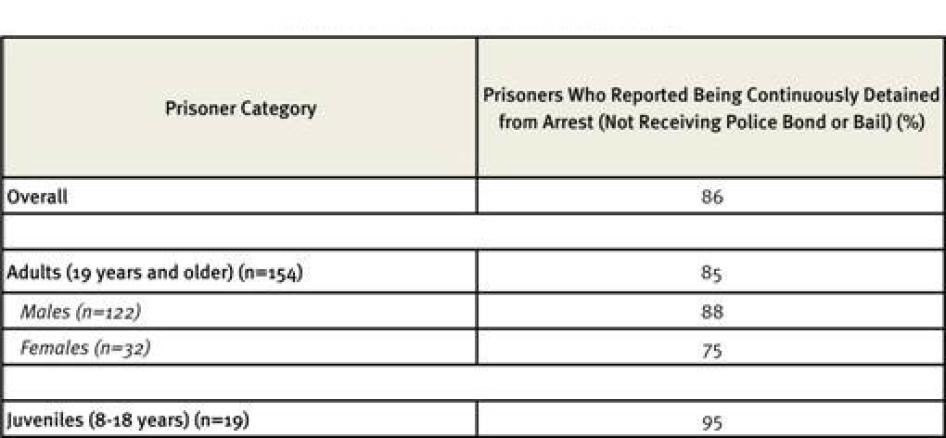

Table 2: Access to Justice for Prisoners Interviewed

*Under Zambian law, a prisoner under the age of nineteen years (the minimum age of criminal responsibility is eight years) is classified as a “juvenile,” despite the fact that under international law, 18 year-olds are adults. |

Categories of Prisoners Held in Zambian Prisons Under Zambian LawConvicted criminal prisoner (convict): A prisoner serving a sentence, having been found guilty of a criminal offense by a court. Unconvicted prisoner (remandee): Any person committed to custody by a court order or order of detention who is not a convicted criminal prisoner. Juvenile: Under Zambian law, a prisoner under the age of nineteen years (the minimum age of criminal responsibility is eight years) is classified as a “juvenile,” despite the fact that under international law, 18 year-olds are adults. Throughout this report, the term “juvenile” will be used to designate the category of prisoners ages eight to 18 held in Zambian prisons when necessary to refer to the classification used by the government. Otherwise, individuals in prison under age 18 will be referred to as “children” in accordance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Prohibited Immigrant: A prisoner detained under a broad range of alleged immigration-related violations, including visitors with an expired permit to remain in Zambia, individuals entering Zambia without being able to establish a valid passport, and persons previously deported from Zambia. Throughout this report, individuals detained under the “prohibited immigrant” classification will be referred to as “immigration detainees”. |

Summary

I have seen people die in the night in the cell—there is nothing we can do. We shout for someone, but the guards will say, “he is just playing sick, he wants to escape. Let us wait two or three days, and see how he will be.” And then he dies.

– Nickson, 36, Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison, September 30, 2009

They say, “you’re going to Chimbokaila [Lusaka Central Prison]? It’s a death sentence.” Not because they are afraid you will be given beatings, but because of TB. They know the conditions are bad.

– Dr. Chisela Chileshe, director, Zambia Prisons Service Medical Directorate, Lusaka, February 6, 2010

People who break the law should be held accountable. The appropriate punishment may be imprisonment. But for detainees in Zambian prisons—a third of whom have never been convicted of any crime—being held behind bars can have life-threatening consequences. Overcrowding, malnutrition, rampant infectious disease, grossly inadequate medical care, and routine violence at the hands of prison officers and fellow inmates make Zambian prisons death traps.

Zambia’s prison system is in crisis. Built to accommodate 5,500 prisoners before Zambian independence in 1964, the country’s prisons housed 15,300 in 2009. Between September and October 2009, the Prisons Care and Counselling Association (PRISCCA), AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA), and Human Rights Watch visited six facilities, two of which were filled at 573 percent and 622 percent of capacity, respectively. Some inmates are forced to sleep seated, or in shifts.

Inmate health problems are compounded by practices prohibited under international law as inhuman and degrading treatment or as torture, such as corporal punishment and “penal block” isolation practices, where prisoners are stripped naked and left in a small, windowless cell while officers pour water onto the floor to reach ankle or mid-calf height. There is no toilet in the cell, so inmates must stand in water containing their own excrement. Certain inmates—appointed as “cell captains” by officers—are also invested with disciplinary authority and mete out the overwhelming majority of punishments, through night-time “courts” in their cells and beatings. Beatings are particularly harsh when aimed at inmates engaging in same-sex sexual activity, and at prisons with associated farm facilities, where inmates’ hard labor conditions closely resemble slave labor.

Water is unclean or unavailable; soap and razors are not provided by the government. The food provided by the Prisons Service is so insufficient and nutritionally inadequate that food has become a commodity traded for sex or labor in the prisons.

In October 2009, the Zambia Prisons Service employed only 14 health staff—including one physician—to serve its 15,300 prisoners. Of Zambia’s 86 prisons, only 15 had any health clinic or sick bay, many of these with little capacity beyond distributing paracetamol. For those prisons without a clinic—and for more serious medical conditions at those with a clinic—access to care is controlled by medically unqualified and untrained prison officers. Lack of adequate prison staff for the transfer of sick prisoners—as well as lack of transportation and fuel—and security fears also conspire to keep inmates from accessing medical care outside of the prisons, in some cases for days or weeks after they fall ill.

Even while largely unknown and unmeasured, tuberculosis (TB) transmission is a constant and serious threat in the prisons’ cramped, dark, unventilated cells. Suspected prevalence rates are very high, with the Zambia Prisons Service reporting an incidence rate for TB of 5,285 cases per 100,000 inmates per year. Rates in Zambia outside of prison in 2007 were less than one-tenth as high.

Only 23 percent of prisoners we interviewed had been tested for TB. The conditions at each of the prisons we visited—combining overcrowding, minimal ventilation, and a significantly malnourished and weakened population—are ripe for the quick spread of TB. The TB isolation cells designed to house the ill are in such poor condition that even the physician in charge of the prison medical directorate deems them “death traps”—yet, since they are slightly less crowded than standard cells, inmates who completed TB treatment told us that they sometimes chose to remain in the cells with inmates with active TB so as to avoid the worst of the desperate overcrowding elsewhere.

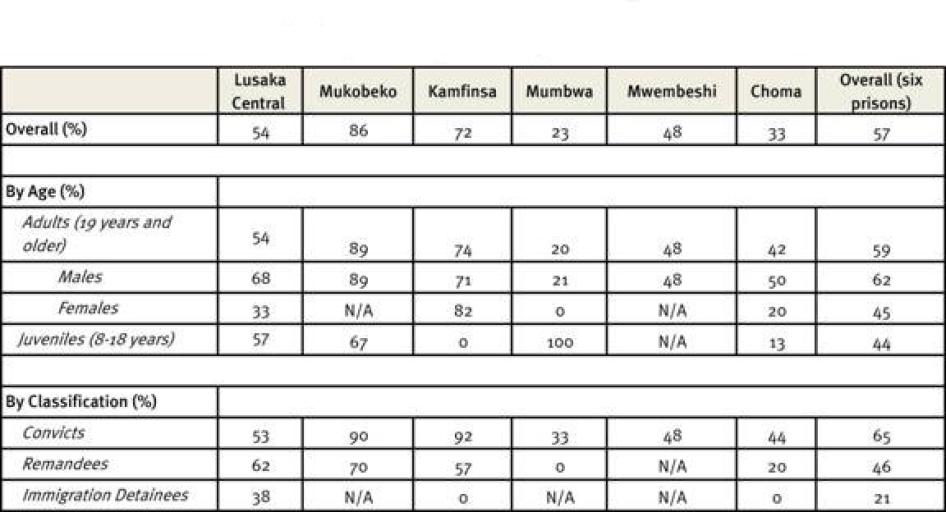

The prevalence of HIV in Zambian prisons was last measured at 27 percent—nearly double that of the general adult population (15 percent). To the credit of Prisons Service officials and non-governmental organization (NGO) partners, in recent years the prisons have expanded HIV testing, so that 57 percent of the prisoners we interviewed across all six facilities we visited had been tested. However, access was uneven: Larger prisons had significantly higher levels of testing than smaller prisons, and men were more likely to be tested than women and juveniles. Access to anti-retroviral therapy (ART) for HIV treatment has also improved among the prison population in recent years, particularly in the larger prisons. However, proper treatment is impossible in the absence of prison-based health services.

According to the prisoners we spoke with, sexual activity between male inmates is common, including both consensual sex between adults, and relationships where sex is traded by the most vulnerable in exchange for food, soap, and other basic necessities not provided by the prison. PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch also documented cases of rape between male prisoners. The total ban on condoms, however, in the context of common sexual activity and rape, creates a serious risk of HIV transmission and presents a major obstacle to HIV prevention.

This report is the first analysis of prison health conditions in Zambia by independent human rights organizations. In preparing this report, PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch interviewed 246 prisoners, eight former prisoners, 30 prison officers, and conducted facility tours at six prisons throughout the central corridor of Zambia. The purpose of this research was to understand health conditions and human rights violations in Zambian prisons, and to provide recommendations for a future which respects the basic rights and minimum standards due to prisoners.

Good prisoner health is good public health. Prisoners come from and mostly return to the community, carrying infectious diseases from one to the other. Prison officers are also daily exposed to the conditions and health risks in prison and can expose their families and contacts outside of prison. While certainly poverty and access to healthcare are issues in the Zambian general population, the government nevertheless has an obligation to ensure basic minimum standards for detainees and medical care at least equivalent to that available in the general population, in order to protect both prisoners’ rights and public health. Resource constraints notwithstanding, the Zambian government has a binding and non-negotiable obligation not to expose people to conditions of torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, which it currently violates when sending people to prison.

Contrary to international standards, convicted, unconvicted, and immigration detainees—children and adults—are held together, equally subject to the prisons’ grossly inadequate conditions. Detainees in each of these categories, men as well as women, face particular challenges in their confinement.

Prisoners who have yet to face trial—routinely held at every facility with convicted prisoners in violation of international and Zambian law—are held on remand for extended periods, exacerbating prison overcrowding. Interviews with inmates, prison officials and NGOs found such problems as police investigation failures, lack of bail, and lack of representation for accused persons keep individuals unnecessarily, and often unlawfully, incarcerated for extended periods of pre-trial detention. The large number of remand prisoners is a result of failures in the criminal justice system as a whole, including the Zambian judiciary, Police, and Prisons services. At Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison, one prisoner told us that he spent three years and seven months awaiting even an initial appearance before a magistrate or judge; another prisoner, now convicted and living at Lusaka Central Prison, told us that he had spent 10 years as an unconvicted prisoner awaiting resolution of his case. The incarceration of unconvicted detainees is clearly a major contributing factor to the prisons’ extreme overcrowding: At Lusaka Central Prison, 601 of the 1145 inmates—more than half—are remandees. Overall, 35 percent of the Zambian prison population is composed of remandees. Even given Zambia’s grossly inadequate prison conditions, the current cost to the government of incarcerating remand detainees unnecessarily for extended periods is not insignificant, and savings could likely be generated by increasing the use of bail instead of pre-trial detention.

Immigration detainees—including administrative detainees held pending deportation—are frequently detained and await deportation without due process, mingled with convicted and remandee prisoners. Among the immigration detainees PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch interviewed, only 38 percent had ever seen a magistrate or judge, compared with 97 percent of non-immigration detainees. Many who were detained appeared to have reasonable claims to legal status. Immigration detainees are routinely told to pay for their own deportation and are held until they pay.

Children held in detention are entitled to particular protections under international law. Children should be detained only as a last resort, and for the shortest appropriate time; children who are detained should be separated from adults. However, in Zambia, children are routinely incarcerated for minor offenses, often after criminal processes in which they have not had any legal representation. Held together with adults (including adults incarcerated on charges of defilement of a minor) at some facilities, detained children are exposed to the risk of rape.

Women detainees are entitled to specific protections under regional human rights standards, but incarcerated women in Zambia do not have their unique healthcare needs met. Women’s health services including gynecological care and cervical cancer screening are non-existent. Pre-natal services are absent or inadequate, and there is no HIV Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) program under the prison medical directorate. The already nutritionally inadequate prison food is unchanged for nursing or pregnant women.

Compounding these injustices and overcrowding is injustice within the criminal justice system. The Zambian police and Drug Enforcement Commission (DEC) enjoy broad powers under Zambian law, and police and DEC officers reportedly arrest and hold numerous alleged family members, friends, and innocent by-standards as “co-conspirators” when their primary targets cannot be found. Such arrests, which may or may not comply with Zambian law, are considered arbitrary arrests—and therefore unlawful—for the purpose of international standards on the deprivation of liberty. Lack of non-custodial sentencing, restrictions on the use of parole, and delays in appeals further contribute to overcrowding.

Under international human rights law, prisoners retain their human rights and fundamental freedoms, except for the restrictions on rights necessitated by the fact of incarceration itself. States are required to ensure prisoners a standard of health care equivalent to that available to the general population, a commitment acknowledged by the Zambia Prisons Service.

The Zambian government has repeatedly committed itself to uphold the human rights of prisoners through its assumption of international and regional obligations. As a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention Against Torture, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the African [Banjul] Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and its protocol on the rights of women, Zambia has an obligation to ensure that its criminal justice and penitentiary standards comply with international and regional human rights standards, to ensure that detainees are treated with appropriate dignity and full respect for their human rights, and to prevent all forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

Clearly, resource constraints are a major consideration, but greater priority on prison funding needs to be put at the national level and greater support from international donors needs to be forthcoming if change is to be effected. Some necessary reforms—particularly legal reforms—are resource-neutral; those that aren’t are crucial to the realization of the rights of prisoners and are the responsibility of both the national government and international donors.

To address existing human rights violations in its prisons, the Zambia Prisons Service should immediately reform prison disciplinary systems to discontinue current abusive disciplinary practices, and end the use of cell captains to carry out brutal punishments on behalf of prison officials. Prisoners should not be punished for sexual or other kinds of intimacy, except in cases of rape.The Prisons Service should immediately install a clinical officer at each prison to assess health and review prisoner medical complaints. In the intermediate and longer term, the Prisons Service—in collaboration with the Parliament and international donors—should secure enough funding for the prison budget to ensure conditions consistent with international standards and scale up prison-based medical care.

Furthermore, in order to alleviate the failings in the criminal justice system that exacerbate overcrowding and violate the rights of prisoners, the Zambian Parliament, judiciary, Police Service, and Prisons Service need to work together to decrease arbitrary arrests, increase the use of bail, and reduce judicial delays. Significant effort should be made to scale up the use of parole and non-custodial alternatives to incarceration. Every prisoner, including child detainees, should be able to exercise their right to have a lawyer of their choosing. Only with cooperation between these bodies, and with the assistance of international agencies, donors, and NGOs, will the rights of prisoners and the goal of prisoner rehabilitation be fully realized.

Zambia’s prison system is at a pivotal moment for change to bring the conditions in its prisons in line with its international and national commitments to prisoner health. The Zambia Prisons Service, in conjunction with PRISCCA and other stakeholders, has itself recently completed an audit of Zambia’s 53 standard prisons, research that included detailed information on prison facility conditions and a list of prisoners at each facility in need of special assistance. Having acknowledged the problems in the prison system, conducted an internal audit, appointed a new medical director, and granted access to human rights monitors, the Zambia Prisons Service has shown a desire and openness to improvement. By building on the observations in its own audit, those of outside human rights groups, and collaborating with Parliament, the judiciary, the immigration service, the police, and international agencies, donors, and NGOs, the Zambia Prisons Service has the opportunity to improve the welfare of its prisoners, and to become a regional model in doing so.

Key Recommendations

For Immediate Implementation

- The President of Zambia should issue a public statement identifying prison conditions and health as a national crisis and should establish a high-level inter-ministerial task force to urgently develop a national prison health plan

- The Zambian Parliament should amend the law to limit the powers to carry out sweeping, group arrests in violation of international law currently enjoyed by the police and Drug Enforcement Commission

- The Zambian Parliament should address overcrowding by taking steps to expand parole eligibility by amending the Prisons Act and Prisons Rules

- The Zambia Prisons Service and Ministry of Home Affairs should prohibit the use of penal block practices, and discipline staff and inmates for abuses against prisoners

- The Zambia Prisons Service and Ministry of Home Affairs should establish the presence of a clinical officer at each prison who can judge prisoner health complaints and facilitate access to outside Ministry of Health medical facilities

- The Zambia Prisons Service and Ministry of Home Affairs should provide condoms to all prisoners and prison officers, in conjunction with education on harm reduction to increase condom acceptance

- The Ministry of Justice should issue guidelines for bail administration to encourage increased defendants’ instruction in bail rights and increased granting of bail, considering accurate information about household incomes in Zambia

- International agencies, donors, and NGOs should integrate discussion of prison health into existing technical advisory committees to the Zambian government

For Intermediate-Term Implementation

- The Zambia Prisons Service and Ministry of Home Affairs should consistently separate children and adults, and convicted, remand, and immigration detainees

- The Zambian Parliament should allocate funding for supervision of community-based sentences

- The Zambian Parliament should repeal or amend Sections 155, 156, and 158 of the Penal Code in order to decriminalize consensual sexual conduct among adults, and implement gender-neutral laws to protect adults and children from sexual violence and assault

- International agencies, donors, and NGOs should fund and supplement direct health service programs in prisons including TB testing and treatment; women and children’s health; and nutrition support

- The Zambian judiciary and Ministry of Justice should ensure all detainees, including those under 18, have access to a lawyer of their choice

- The Ministry of Health should develop a detailed plan for the improvement of prison health services and conditions as part of its National Health Plan 2011-2015

For Long-Term Implementation

- The Zambian Parliament should secure and international donors should assist with securing enough funding for the prison budget to ensure conditions consistent with international standards. Funding should be sought for facility renovation, upgrading water and sanitation facilities, adequate food, the provision of basic necessities, and adequate prison-based health services

- The Zambia Prisons Service and Ministry of

Home Affairs should establish clear guidelines on the provision of prison-based

health services, and scale up those services to:

- Conduct health screening of all prisoners upon entry and at regular intervals

- Provide TB screening to all inmates entering prison, and all existing inmates, and ensure prompt initiation on treatment for those with confirmed disease

- Offer voluntary HIV counseling and testing to all inmates entering prison and all existing inmates and prompt initiation on anti-retroviral treatment

- Establish clinics at each prison with a consistent supply of essential medications and a minimum capacity to conduct TB and HIV testing and treatment

- Ensure access to antenatal services, including PMTCT, early infant testing, and ART for infants

Methodology

This report is based on information collected during four weeks of field research conducted by the Prisons Care and Counselling Association (PRISCCA), the AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA), and Human Rights Watch in September-October 2009 and February 2010. The Zambian Ministry of Home Affairs granted permission for access to six prisons and to conduct confidential interviews with inmates and staff, with access provided by the Zambia Prisons Service. Researchers interviewed 246 prisoners, eight former prisoners, 30 prison officers in charge and officers, and conducted facility tours at six prisons throughout the central corridor of Zambia. 232 of the prisoners interviewed completed a survey providing information about the prisoner’s incarceration history, medical care, and HIV/AIDS and TB testing and treatment.

Researchers visited six facilities: Lusaka Central Prison (Lusaka province), Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison (Central province), and Kamfinsa State Prison (Copperbelt province); one rural district prison: Mumbwa Prison (Central province); and two peri-urban prisons: Mwembeshi Commercial Open Air Farm Prison (Central province), and Choma State Prison (Southern province).

Researchers also interviewed 28 representatives from local and international organizations working on prison, HIV/AIDS, and health issues, and donor governments and agencies.

Researchers engaged repeatedly with Zambian government officials throughout the course of this research. The research commenced with a workshop, attended by the commissioner of prisons, officers in charge and officials of the Zambia Prisons Service, to introduce the research and identify key prison health concerns of prison officers and officials. Researchers also conducted 18 interviews with officials from the Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Health, Zambia Prisons Service, police and immigration services, the Drug Enforcement Commission, the National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council, and the National Human Rights Commission. Researchers toured Lusaka Central Prison, the prison clinic, and the University Teaching Hospital accompanied by Dr. Chisela Chileshe, the director of prison medical services. PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch lodged a letter with the commissioner of prisons requesting the Prisons Service’s Annual Reports and statistics on prison staffing, deaths in custody, reports of those who are ill in custody, and reports of assaults and disease in prison custody in accordance with Zambian law requirements that such records be kept [see Appendix]. As of this writing, our request had not been answered. PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch also lodged a letter with the Drug Enforcement Commissioner requesting copies of records or reports on the number and charges of individuals arrested, convicted, and incarcerated in Zambia on drug-related charges. As of this writing, that request had also not been answered.

In each prison visited, the research team requested from the officer in charge a private location to conduct interviews with a cross-section of prisoners held in that facility, including female prisoners, immigration detainees, juveniles,[1]and pre-trial detainees. Priority was given to the inclusion of prisoners from each category rather than proportional representation. Officers identified prisoners who were then provided an explanation of the survey, asked if they were willing to participate, and assured of anonymity in the final report.

Table 3: Prisoner Characteristics

Interviews were conducted in English, French, Bemba, Nyanja, and Tonga, with translation provided by PRISCCA members. Individuals participating were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions without any negative consequence. The names of all prisoners interviewed and quoted in this report have been changed to protect their identity and for their security.

The average length of time prisoners we interviewed had spent in prison varied widely, ranging from an average of less than one month for adult females at Mumbwa Prison, to an average of 44 months for adult men at Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison. The prisoners we interviewed across prisons had an average age between 30 and 40, and most were of Zambian nationality, though non-Zambian nationals were more common at Lusaka Central and Kamfinsa prisons. Male prisoners had more frequently achieved secondary or higher education than female prisoners. The percentage of married prisoners ranged from 41 at Lusaka Central to 70 at Mwembeshi.

Table 4: Prisoner Interviewee Demographics

Background

The Prisons of Zambia

Despite international and national legal commitments to prisoner health, observers have noted in recent years that conditions in Zambia’s prisons are grossly inadequate.[2] Zambia’s prisons were built prior to 1964 to accommodate 5,500 prisoners.[3] In October 2009, they housed 15,300—nearly three times official capacity.[4] In 2005, when the total national prison population was 14,427, nearly 35 percent of those were remand prisoners awaiting trial (including 230 remanded juveniles).[5] Women constitute 2.6 percent of the total convicted prison population in Zambia.[6]

Zambia has a total of 86 prisons throughout the country, 53 of them standard prisons and 33 open air/farm prisons. One of these facilities is dedicated exclusively to juveniles, and one exclusively to women, though juveniles are incarcerated with the adult population at other facilities throughout the country, and women live in separate sections of additional facilities throughout the country.

Zambia’s Prison Population[7]2005 Total Population: 14,427 Adult Convicts: 8,658 Adult Remandees: 4,938 Immigration Detainees: 294 Condemned Prisoners: 273 Remandee Juveniles: 230 Convicted Juveniles: 79 Mentally Ill Prisoners: 25 |

Source: Zambia Human Rights Commission, “Annual Report: 2005”

By law, the Zambia Prisons Service is established for the management and control of prisons and the prisoners they hold.[8] International law requires that penitentiary systems’ “essential aim” is prisoners’ “reformation and social rehabilitation,”[9] and Zambia’s system espouses the goals of both order and reform.[10]

Zambian law establishes minimum standards for medical care, and requires that the officer in charge of each prison maintain a properly secured hospital, clinic, or sick bay within the prison.[11] A serious gap exists between these legal requirements and practice, with little or no medical care available at most of Zambia’s 86 prisons. Only 15 of Zambia’s prisons include health clinics or sick bays, and many of these clinics have little capacity beyond distributing paracetemol.[12] In February 2010, the Zambia Prisons Service employed only 14 trained health staff—one physician, an administrative rather than a clinical role, one health environmental technician, nine nurses, and three clinical officers[13]—with 11 prospective staff still in training.[14] “The ratio is out of this world,” Dr. Chisela Chileshe, the physician in charge of the prison medical directorate, concluded, referring to the ratio of medical staff to the inmates under their care.[15]

While there are some Ministry of Health medical staff seconded to work in the prisons, they are often present there only a few days a week, and there is only one Ministry of Health physician who visits the prisons.[16]Coordination between prison health officials and Ministry of Health officials has been minimal. The National Health Strategic Plan 2006-2010, designed to lay out how to achieve national health priorities through goals for government, health workers, cooperating partners, and other key stakeholders, includes no mention of prisons.[17]

Donors have actively supported health initiatives in Zambia, though relatively little of this assistance has gone to government or NGO-based prison health initiatives thus far. For HIV/AIDS alone, in 2009 the United States contributed over US$262 million and the Global Fund contributed over $137 million to Zambia, with other major HIV/AIDS donors including the European Union, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.[18] In 2008, the National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council analyzed HIV/AIDS spending in Zambia. That assessment listed no amount for aid to prisoners in 2005 and $76,300 in 2006.[19] Some NGOs have received grants for prison-based health work—for example, in 2006 the Prisons Fellowship of Zambia in Lusaka and Ndola each received $10,506 as Global Fund Sub-Recipients,[20] the Go Centre/CHRESO Ministries, which provides HIV testing and treatment at several prisons, is funded by the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief,[21] and USAID funds an HIV prevention, treatment, care and support (“SHARe”) program which operates in some prisons.[22] Funding problems for both Prisons Service and Ministry of Health services will be compounded by the fact that, as a result of a corruption scandal at the Ministry of Health, Global Fund funding to Zambia has been halted pending an audit.[23]

Funding to improve the prisons generally is inadequate.[24] In 2010, the Zambian national budget was over 16 trillion Zambian kwacha ($3,376,810,000), 14.5 percent of which was financed through partners.[25] The Zambia Prisons Service 2010 budget was 52 billion Zambian kwacha ($10,974,600).[26] The Prisons Service has never been funded by the Ministry of Finance to its requested amount.[27] NGOs note that every year, the Prisons Service is the least funded of the services under the Ministry of Home Affairs.[28]

Prison medical services particularly suffer from lack of funding. Despite a comprehensive strategic plan on HIV/AIDS/STI/TB, according to the Ministry of Home Affairs HIV/AIDS focal point person Gezepi Chakulunta, “we haven’t done much on the strategic plan because of lack of funding.”[29] Dr. Chileshe explained that plans to expand prison health services were likewise hampered by lack of funding. He has plans for a directorate which will include a head office and prison-based services, a physician in each of the country’s nine regions, a referral hospital for prisoners, and clinics in all the prisons, but funding for such a system remains uncertain.[30]

Prison-based medical care under the medical directorate (aside from seconded Ministry of Health employees and medications) comes out of the prison budget (under the Ministry of Home Affairs), rather than the Ministry of Health budget. In 2009, a budget for prison medical services did not exist.[31] For 2010, Dr. Chileshe reported that “my budget will be 200 million kwacha [$42,210] per year ... about 16.6 million per month [$3,503] excluding salaries....I do not have enough to do all that we want.”[32] By contrast, to have a clinical officer and clinic at each of the 53 standard prisons (still leaving 33 open air prisons without a Prisons Service clinic), he said, would cost about 26 billion kwacha ($5,487,320).[33]

HIV and TB in Zambia and the Prison System

While HIV prevalence among Zambian adults is 15 percent,[34] available evidence suggests that HIV prevalence in Zambian prisons is significantly higher. A study conducted in 1998-99 in three Zambian prisons found a male HIV prevalence of 27 percent, and a prevalence of 33 percent among female inmates.[35] Based on these data, prevalence has until recently been routinely estimated at 27 percent of the overall prison population.[36] HIV/AIDS has had deadly consequences in the prison population, among officers and inmates: Between 1995 and 2000, an estimated 2,397 inmates and 263 prison staff died from AIDS-related illnesses.[37]

In the general population, in 2004, the Zambian government introduced free access to anti-retroviral therapy (ART) in the public health sector. In June 2005, the government declared the ART service package (including counseling, x-rays, and CD4 testing[38]) free of charge.[39] The Zambian National HIV/AIDS Policy includes prisoners and commits to providing HIV prevention information, voluntary counseling and testing upon admission to custody, and detection and treatment programs to prisoners.[40]

Since its commitment to free treatment in the public health sector, Zambia has been making progress in treating its HIV-positive population. Between 2004 and 2007, the number of people on ART jumped from 20,000 to 151,000, an increase from seven percent coverage of those requiring it to 46 percent.[41] The estimated percentage of women living with HIV who received ART to prevent mother-to-child transmission increased from 18 percent in 2004 to 47 percent in 2007.[42] However, Zambian HIV/AIDS NGO representatives report that access to ART in rural areas is significantly more limited than that in urban areas, and there is also a sizable difference between medical infrastructure and personnel availability between urban and rural areas.[43] Access or further expansion is uncertain with the suspension of Global Fund grants, pending corruption investigations.

Such a high HIV prevalence, coupled with poor prison conditions, raises a significant risk of tuberculosis (TB) infection. As well as being the most common opportunistic infection among people living with HIV in Africa, TB is pervasive in southern African prisons because of overcrowding, poor ventilation, and lack of prevention practices such as prompt identification and treatment of persons with active TB.[44]A 2000-2001 study in 13 Zambian prisons for pulmonary TB among inmates concluded that a high rate of pulmonary TB exists in Zambian prisons, speculating that true prevalence rates may approach 15-20 percent, with significant rates of drug resistance and multi-drug resistant TB[45] (MDR-TB).[46]Indeed, with mortality rates as high as 24 percent, tuberculosis is among the main causes of death in prisons in developing countries.[47]Worldwide, TB is the “leading infectious killer for people living with HIV”, responsible for an estimated 13 percent of AIDS deaths.[48]

In the general population, Zambia bears a heavy burden of TB, with a prevalence of 387 cases of all forms of TB per 100,000 members of the population in 2007 and 115 TB-related deaths per 100,000 members of the population in that year.[49] In 2009, there were 50,000 cases of TB throughout the country.[50] MDR-TB comprised 1.8 percent of all new TB cases in 2007. Yet Zambia has also been making progress in treating TB in the general population: Between 2000 and 2006, the coverage of Directly Observed Treatment, Short-course (DOTS) expanded significantly.[51] For new sputum smear-positive cases, between 1999 and 2007, the treatment cure rate rose from 50 percent to 78 percent; the treatment success rate rose from 69 percent to 85 percent.[52] However, difficulties in screening, diagnosing and treating various forms of TB—particularly extra-pulmonary TB—continue to contribute to difficulties in establishing an effective response to the disease nationwide.[53]

In the prison population, suspected prevalence rates are very high, though reliable data do not exist.[54] The physician in charge of the prison medical directorate reported that TB is the leading cause of death in the prisons;[55] he acknowledged that “the prisons are a breeding ground for TB/HIV” and has recognized the impact of prison conditions on the spread of TB.[56] The Zambia Prisons Service has reported a case infection rate for TB of 5,285 cases per 100,000 inmates per year.[57]

At Mumbwa prison, a prison officer reported that with a prison population of 354, only four prisoners had been tested for TB in the previous year—and all four were found to be positive.[58] High HIV prevalence compounds the dangers posed by TB: As the HIV/AIDS coordinator at Lusaka Central prison aptly noted, “People with compromised immune systems are vulnerable to TB. Ventilation is very poor at the prison. People with HIV catch TB easily.”[59]

Zambia’s Obligations Under International, Regional, and Domestic Law

The Zambian government is obliged under national and international law to protect the rights of prisoners and those in its custody.

On the international level, Zambia is a party to core regional and international human rights treaties. These include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention Against Torture (CAT),[60] the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR),[61] the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW),[62] the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC),[63] the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD),[64] the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights,[65] and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa.[66] These treaties provide for the protection of basic civil and political rights and also ensure specific guarantees relating to the treatment and conditions in custody for those deprived of their liberty. These treaties are supplemented by instruments specific to the treatment of those in detention, discussed below.

On the national level, key protections are laid down in the Constitution and The Prisons Act and Rules of the Laws of Zambia.

Prisoners’ Rights

Under international human rights law, prisoners retain their human rights and fundamental freedoms, except for such restrictions on their rights required by the fact of incarceration; the conditions of detention should not aggravate the suffering inherent in imprisonment,[67] except as necessary for justifiable segregation or the maintenance of discipline.[68]This rule cannot be dependent on the material resources available to the national government in question.[69]

The most fundamental protection for prisoners is the absolute prohibition on torture. As well as being a well-established norm of international law by which Zambia is bound, the prohibition is also reflected in the Zambian Constitution, and in several of the human rights treaties to which Zambia is a party.[70] The ICCPR and the CAT prohibit torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment without exception or derogation. Article 10 of the ICCPR further requires that “[a]ll persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.”[71] The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights also protects every individual’s human dignity and prohibits “all forms of exploitation and degradation,” including slavery, torture, and cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment and treatment.[72]

The CAT defines torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment to include not only acts committed by public officials, but also acts committed with their acquiescence.[73] Thus, prison officials are responsible for all abuses in prison committed by inmates with their acquiescence.

Numerous international instruments provide further guidance on the protection and respect of human rights of persons deprived of their liberty. The most comprehensive such guidelines are the United Nations (UN) Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. Other relevant instruments include the Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment and the Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners.[74]

International law and standards guarantee imprisoned children special protections. The Convention on the Rights of the Child protects children from torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and provides that children deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the person.[75] Detention of a child “shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.”[76] For those children who are detained, they are to be separated from adults.[77] The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice lays out additional protections for children deprived of their liberty.[78]

Women detainees also benefit from special legal protections. Regional law provides that women in detention should be held in an environment “suitable to their condition” and ensures their right to be treated with dignity.[79] The Southern African Development Community Protocol on Gender and Development, which Zambia has signed, commits states by 2015 to “ensure the provision of hygiene and sanitary facilities and nutritional needs of women, including women in prison.”[80]

The Right to Health

All people have a right to the highest attainable standard of health.[81]The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights requires states parties to take steps individually and through international cooperation to progressively realize this right via the prevention, treatment, and control of epidemic diseases and the creation of conditions to assure medical service and attention to all.[82] African regional law also supports the right to health.[83] “Progressive realization” demands of states parties a “specific and continuing obligation to move as expeditiously and effectively as possible towards the full realization of [the right].”[84]The concept of available resources is intended to include available assistance from international sources.[85]

States have an obligation to ensure medical care for prisoners at least equivalent to that available to the general population.[86] According to the Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Committee, the monitoring body for the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, “States are under the obligation to respect the right to health by, inter alia, refraining from denying or limiting equal access for all persons, including prisoners or detainees, minorities, asylum seekers and illegal immigrants, to preventive, curative and palliative health services.”[87]Furthermore, the ICCPR requires that governments should provide “adequate medical care during detention.”[88] The Committee Against Torture—the monitoring body of the Convention Against Torture—has found that failure to provide adequate medical care can violate the CAT’s prohibition of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.[89]

Thus, international human rights law explicitly protects prisoners against discrimination in receiving health care. The Zambia Prisons Service has acknowledged this commitment: “It has been decreed in various Charters, Conventions and International Instruments that all prisoners, irrespective of nationality, race or gender are entitled to the same quality of health care as that available outside jail.”[90]

Prison Conditions and Consequences for Detainees’ Health

These conditions defeat the purpose of rehabilitation. You cannot subject people to this and expect them to reform. It’s so tough and rough that it is survival of the fittest. A person who walks in a good person, before serving one fourth of their sentence, they become a beast. They leave deformed. These conditions destroy us mentally and physically.

– Winston, 35, Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison, September 29, 2009

All prisoners are due respect based on their inherent dignity as human beings.[91] The requirement to take positive steps to ensure minimum guarantees of humane treatment for persons within their care[92] implies an obligation on states “to fulfil and protect the various human rights of detainees, above all their rights to food, water, health, privacy, equal access to justice and an effective remedy against torture and other human rights violations, [which] derives from the simple fact that detainees are powerless.”[93] Current conditions in Zambian prisons violate international law and standards on prisoners’ welfare.

Overcrowding

The way they used to pack slaves in the ship, that is how we sleep.

– Kenneth, 37, Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison, September 30, 2009

Zambian prisons are among the most overcrowded prisons in the world, and were at over 275 percent of capacity in October 2009.[94] The government of Zambia itself has admitted that “Zambian prisons have for a long time experienced enormous problems” including “poor state of infrastructure, congestion, poor diet, poor health care, poor sanitation and water supply and a general lack of rehabilitation facilities,” and that existing prison population levels “cannot be sustained by the current prison infrastructure.”[95] International monitors have also repeatedly recognized that overcrowding in Zambian prisons is unacceptable, as are the health and human rights consequences of this overcrowding.[96]

Overcrowding often leads to or exacerbates other problems, including inadequate food, nutrition, and health care; inadequate living conditions; and poor health and hygiene. International standards establish basic requirements with respect to prisoners’ accommodations, including with regard to ventilation, floor space, bedding, sanitation facilities, personal hygiene, and room temperature.[97] PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch documented serious overcrowding that violated these basic standards, and exacerbated existing human rights violations.

At the time of our visit, Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison, a facility built in 1950 for a capacity of 400, housed 1731 inmates[98]—433 percent of its capacity. Lusaka Central Prison, a facility built in 1923 with a capacity of 200[99] housed 1145[100]—573 percent of capacity. Mwembeshi, a farm prison opened with a capacity of 55 inmates, housed 342—622 percent of its capacity—on the day of our visit.[101] At Mukobeko, 140-150 inmates sleep in cells measuring eight meters by four meters,[102] which inmates reported were designed for 40.[103] At Choma, 76-78 inmates sleep in each eight meter by four meter cell.[104]

International standards require that prisoners be provided with a separate bed, and separate, sufficient, and clean bedding. These requirements were not met in any of the facilities visited by PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch.[105]

At many prisons visited, overcrowding is often so severe that inmates cannot lie down at night. J. Kababa, officer in charge at Lusaka Central, confirmed that at that facility: “they sleep in shifts. Because of the congestion, not all can sleep at once. Some sleep, some sit. They take turns to make sure that others get a chance.”[106] He elaborated: “They are not sleeping, they are just squatting. Instead of resting in the night, they come out tired.”[107] Felix, 43, an HIV-positive remandee at Mukobeko, reported that “we have no space. There is not even enough space to lie down. We must sit, packed in like bags.”[108] Detainees at Mukobeko, Mumbwa, and Mwembeshi reported that they sleep on their sides, up to five on a mattress, unable to turn over.[109]

Officers recognized the pain experienced by inmates held in such overcrowded conditions. The social welfare worker at Lusaka Central Prison noted: “There is terrible suffering when you see them at night.”[110] “I am not happy to keep people in these inhumane facilities,” the offender management officer at Mukobeko, admitted.[111]

Over and over again, inmates reported the horrific overcrowding they face every night in their cells, describing the bodies of inmates in the cell as “squeezed like logs in a pile,”[112] “packed like sacks,”[113] or “like bodies in a mortuary,”[114] “like fish in a refrigerator,”[115] or simply “packed like pigs.”[116] Albert, 30, a remandee at Lusaka Central told PRISCCA, ARASA and Human Rights Watch:

We are not able to lie down. We have to spend the entire night sitting up. We sit back against the wall with others in front of us. Some manage to sleep, but the arrangement is very difficult. We are arranged like firewood.[117]

Such overcrowding leads to terrible, repeated suffering, night after night. As Rodgers, age 42, a remandee at Lusaka Central said, “we are being tormented physically. The way we sleep. If you put more pigs in a room for a night than can fit, in the morning you would find all the pigs are dead. These are the conditions we are in.”[118]

Packed together in their cells from four p.m. to six a.m. nightly, illness spreads rapidly among inmates: The medical officer at Choma reported that the most common health problems are respiratory infections, diarrhea, and skin conditions and rashes.[119] Prisoners across facilities reported frequent rashes as a result of close bodily contact. As immigration detainee Jean Marie, age 28, put it, “we are sweating at night on the floor; we don’t know what illness we have but we pass them back and forth.”[120]

The risk of TB transmission is high. Sick and healthy are routinely mixed together, and multiple inmates reported frequent coughing.[121] International standards require proper ventilation to meet the requirements of health and require that windows be large enough to allow the entrance of fresh air.[122] However, ventilation requirements are not met at Zambian prisons. Several of the prisons we visited lacked adequate ventilation, and had only air vents.[123] “We are all breathing the same confined air, contributing to all airborne diseases,” Hastings, 32, told us.[124] Esther, 47, confirmed:

Ventilation is very poor. I have very small window and cell captains block windows with their shoes, etc. and in this season it is so bad, some people faint in the night. In the last month, five times. When we are full, which is at least once a month, we have to sleep sitting up.[125]

International law requires that accused persons and prisoners held on non-criminal charges be kept separate from the convicted and treated separately; that adults and children, and men and women also be separated.[126] Zambian law on the books is in line with most of these standards. However, in practice, detention practices can be different.[127] Men and women were separated at all of the facilities PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch visited, and women guarded only by female officers. However, our research found that, apart from separation of male and female detainees, all categories of prisoners were packed together, in violation of international standards. Convicted, unconvicted, and immigration detainees were held together at all facilities, including non-criminal immigration detainees (among them asylum seekers) held solely on administrative rather than penal grounds, pending their deportation.

Children were not separated from the adult population at the facilities we visited that included child inmates. Patrick Chilambe, the officer in charge at Choma, confirmed that all prison populations, except for males and females, are routinely mixed;[128] “as a father it pains me,” he told us, that children do not have their own facilities—“we need to build a separate area for juvenile offenders.”[129] Kabinga, 17, reported that we “are not happy to share the same cell with adults and have complained to prison management, but our complaint has been ignored.”[130] Peter, a teenager, reported being threatened by other inmates if he revealed the combined sleeping arrangements: “We sleep with the adults, but they told us to say we sleep in a juvenile cell. If we don’t say we sleep in a separate cell, they will beat us. We are given punishment when we start talking. But we are scared we might die here.”[131]

Food and Nutrition

People are very, very hungry. It is difficult to rehabilitate someone when he is starving.

– Clement, 28, Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison, September 30, 2009

The most universal complaint we heard about prison conditions—from nearly every prisoner at every facility we visited—involved the insufficiency and low quality of the food. The food was described by prisoners as “not fit for human consumption,”[132] “food in name only,”[133] and “fit for pigs.”[134] “They really are not getting enough food,” the chaplain at Mukobeko admitted; in fact, “[they are] starving. They always eat something, but it can be a struggle.”[135]

Particularly harsh conditions of detention, including deprivation of food, constitute inhuman conditions of detention in violation of the ICCPR.[136] International standards require that prisoners be supplied with “food of nutritional value adequate for health and strength, of wholesome quality and well prepared and served.”[137] This standard has been cited with approval by the UN Human Rights Committee when examining the minimum standards that a state must observe for those deprived of their liberty, “regardless of a state party’s level of development.”[138] International standards further protect the rights of children deprived of their liberty to suitable food of sufficient quantity and quality to satisfy dietetic, health, and hygiene requirements.[139] Zambian law prescribes a dietary scale that includes meat or fish, cocoa, sugar, salt, fresh fruits in season, and fresh vegetables.[140] Neither international law and standards nor Zambian law requirements are met by the diet provided to prisoners.

Food consists usually of rice at breakfast, followed by a single meal[141] of maize meal and kapenta (tiny dried fish commonly eaten in Zambia) and/or beans at four p.m.. Despite the fact that farm prisons grow tomatoes and other vegetables, the occasional cabbage was the only government-provided vegetable, and most of the vegetables grown on the farms are sold to generate prison income.[142] Cruelly, inmates must therefore toil to produce vegetables that they virtually never have the opportunity to eat, only to see them sold off and the profits disappear into the prison system. The Zambia Prisons Service HIV and AIDS/STI/TB Strategic Plan (2007-2010) has noted that “the practices of diverting food from prisons or selling crops where the proceeds do not revert back to Prisons Service must be stopped.[143] “Vegetables?” asked Winston, 35, “It’s like vegetables don’t even exist. They sell the stuff from the farm; we don’t ever see it.”[144] The quantity of meals was reported by prisoners across facilities and confirmed by the officer in charge at Mumbwa to be approximately 400 to 450 grams of maize meal per day (400 grams of maize meal is equivalent to roughly 1,400 calories[145])—in addition to small quantities of beans and/or kapenta.[146] George Sikaonga, the officer in charge at Mukobeko, though, claimed that the issue, as per the dietary school, was 900 grams of maize meal per day.[147] Meals were widely considered insufficient and many prisoners reported a constant feeling of hunger.[148] “I go to bed hungry,” George, 44, an immigration detainee at Kamfinsa, told us.[149] Frederick, 23, an inmate at Mwembeshi farm prison, said that “we are starving by the time we eat and it is not enough after all day of work.”[150]

Inmates and prison officers at several prisons reported that prisoners were routinely denied food. Inmates at farm prisons said that these facilities often ran out of food, leaving some inmates with nothing to eat. Johnston, 41, a remandee at Mumbwa, told us that remandees only eat after convicts, “so if it is all gone, we don’t eat anything. This happens regularly.”[151] Robbie, 33, an inmate at Mwembeshi farm prison, reported “we have a shortage of food. When we are short, we have to sleep without eating anything until tomorrow. Some nights we eat nothing. When we are short, we just sleep like that. It happens once a week, sometimes twice a week.[152] Furthermore, Adam, 34, a remandee at Mumbwa, reported that because the prison has no electric cookers, “When it rains we can’t use the firewood. We eat nothing on those days. When we can’t cook, we don’t eat.”[153] The officer in charge at Choma said that because of firewood shortages, cooking and serving meals was sometimes done only once a day.[154]

Poor nutrition leads to numerous health problems. Dr. Chileshe confirmed that malnutrition is a serious problem throughout the prison system.[155] The medical officer temporarily stationed at Mukobeko, who has been with Zambia Prisons Service for nine years, noted that food provided to prisoners is inadequate and unvaried, with the result that some prisoners become malnourished; approximately seven of every 20 medical cases he screens point to malnutrition.[156] The medical officer at Choma prison also confirmed that she found inmates to be malnourished.[157] Inmates reported that the poor quality of food and water led to persistent diarrhea[158]; one reported dental problems as a result of the stones mixed in with the food,[159] and another reported that he couldn’t see properly as a result of malnutrition.[160]

The lack of nutritional diversity in prisoners’ diet may be creating serious and life-threatening health conditions: PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch heard repeated reports of swollen legs and feet,[161] symptoms which are consistent with the nutritional deficit disorder “beri beri.”[162] Francis Kasanga, the deputy officer in charge at Mukobeko, reported that in winter (July) 2009, as many as seven inmates had developed swollen legs and died shortly thereafter. An investigation was conducted and “several doctors recommended the introduction of a special diet, including fruit for the affected, and the problem cleared after this intervention.”[163]

There is no special diet for pregnant women[164] or for women who are nursing.[165] Despite international standards calling for special provision for children incarcerated with their parents[166] and the legal provision that, subject to the commissioner’s conditions, “the infant child of a woman prisoner may be received into the prison with its mother and may be supplied with clothing and necessaries at public expense,” and may stay up until age four,[167] there is no food at all allocated to the children under age four who live with their mothers in prison facilities; they are expected to share out of the portion of the mother.[168] In situations where women are unable to breastfeed, the prison does not offer infant formula. Agnes, 25, an inmate living with her nine month-old baby boy, informed us:

My child is not considered for food—I give my share to the baby (beans and kapenta)—we eat once a day. I am not given any extra food, and no special diet for the child. I am simply able to make some porridge for him out of my nshima [a cornmeal porridge]. The baby has started losing weight and has resorted to breast milk because the maize meal is not appetizing.[169]

The officer in charge at Lusaka Central echoed these concerns: “I get no budget for the children’s food, they must eat their mothers’ food. They are hungry a lot.”[170] Tasila, 24, a pregnant inmate, expressed concern about how she would keep her child fed, clothed, and in good health.[171] Annie, 33, an HIV-positive female inmate, told us that the she could not get extra food for her child, even from church donations, because the “cell captains and officers contrive to take donations of food and goods brought by the church. There is nowhere to go and complain.”[172]

As a result of chronic food shortages, food has become a commodity that is traded to the most vulnerable in exchange for sex and labor. As Willard, 25, put it, “Food is used as power. Those who have relatives who bring them food are powerful in prison, those of us without relatives are weak.”[173]

Orbed, 26, described to us how inmates come to trade sex for food:

Food is a major problem. The quantity and quality are both poor. It is not enough to sustain one’s life in here. We lose weight, we are enslaved—all because of food. Those who are able to afford food can enslave others. They say, “I will give you whatever you want for food if you sleep with me,”—it happens a lot.[174]

Lawrence, 33, confirmed this practice:

Those who have been here much longer get more food, and the lion’s share of everything. For those who come late, they must give services in exchange. It is very common, especially for those who do not receive any help from their families. They are the victims. The food we are fed with is not food that someone can live with. So people tend to give in to such practices if they are less privileged.[175]

Prisoners speaking with us recognized that sex can spread HIV:

I have seen [sexual activity] happen all the time where mostly the lifers, who have nothing to lose, will entice new and vulnerable inmates to sodomy with food and cooking oil. Then they get HIV and when they get out they infect their families. Or they die. I have had several friends catch and die of HIV that way.[176]

Access to Potable Water and Basic Hygiene

It tastes foul, but we drink it.

– Annie, HIV-Positive Inmate, Lusaka Central Prison, October 4, 2009

The UN Standard Minimum Rules on the Treatment of Prisoners specify that sanitary facilities shall “enable every prisoner to comply with the needs of nature when necessary and in a clean and decent manner” and furthermore that “[a]dequate bathing and shower installations shall be provided so that every prisoner may be enabled and required to have a bath or shower, at a temperature suitable to the climate, as frequently as necessary for general hygiene according to season and geographical region.”[177] Sanitation and water facilities in Zambia’s prisons do not meet international standards and indeed violate prohibitions on inhuman and degrading treatment. They also pose a major health risk.

Toilets are insufficient in number and are filthy; in some prisons they consist only of a hole in the ground and at others simply a bucket.[178] At Mwembeshi, inmates reported that there were no toilet facilities at all in the cells, and a bucket was used overnight. The lack of a sewer system, the officer in charge concluded, is “dehumanizing.”[179] What outmoded and insufficient sewer systems do exist are constantly backing up—all of the pipes of the Mukobeko sewer system, built in 1957, are constantly blocked.[180] At that prison, 10 outdoor toilets are shared by more than 1,000 inmates. Paul, 33, at Mukobeko, said, “you pray for your friends not to use the loo.”[181] “You have to plan in advance because there is a long queue,” Daniel, 39, a “lifer” at Mukobeko, pointed out. “You can wait for hours,”[182] leading to fights between inmates.[183] In the cells at Mukobeko, with one toilet for 140-150 inmates, “we queue from when we are locked up, straight through until the morning.”[184] Anderson, 35, an inmate at Choma, told us that there were two toilets for 150 inmates on his side of the prison, which overburdened the system to the extent that “the toilets are always overflowing as people have diarrhea all the time.”[185] At Lusaka Central, female inmates reported that the two toilets in each cell are reserved for urination: “If we excrete for any reason...we were told we would be punished by the cell captain,”[186] –“we must get permission from cell captain to poop when necessary.”[187]

Inadequate toilet and bathing facilities pose particular problems for disabled inmates. Chrispine, 46, a remandee on crutches with one leg amputated, told us that it was particularly hard for him to use the hole in the ground for a toilet,[188] a difficulty confirmed by other disabled inmates.[189] “I find it difficult to balance, jumping over my colleagues in the cell to the toilet,” one explained.[190]

Additionally, water sources at some facilities are disturbingly close to sanitation outflows.[191] As Kalunga, 29, reported, “there is one bowl and pump for water, right next to the pit for trash, which is right next to the pit toilets.”[192] At Mwembeshi, the offender management officer told PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch that “the water table is low, close to latrines. The technician told us we need more chlorine which we don’t often have.”[193] Inmates at multiple facilities described drinking water as unclean.[194]

Furthermore, despite international standards dictating that drinking water be available to every prisoner whenever he or she needs it,[195] water availability is subject to shortages at many of the prisons, in some cases because the water bill is not paid,[196] water is rationed[197] or during electrical shortages.[198] At Mukobeko, the offender management officer reported that the water supply is clean but subject to erratic supply.[199] A prison officer at Mukobeko told us that he has seen fighting among the inmates “many times in accessing water.”[200] Water shortages lead to the use of unclean water: “There is tap water but we go to a stream to fetch water when we get none—none of it is treated, it does not look clean.”[201]

Bathing facilities at some prisons are squalid. At Mwembeshi, the bathing area is a muddy grass structure with no drainage[202] and prisoners reported sharing buckets used for bathing.[203] One inmate reported that they even reuse the same containers for bathing which are used as toilet facilities in the cell at night.[204]

A possible consequence of such poor water quality and sanitation, diarrheal disease is common among inmates. At Mwembeshi, the offender management officer informed us that poor hygiene resulting from a lack of toilets with water, and the use of buckets, facilitates diarrhea.[205] Inadequate water quality and sanitation also can have additional, deadly consequences for inmates: Adam, 34, a remandee, told PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch, “the remandees are told to pick up the toilet tissues after the night and clean up the area in the cell. This is without gloves, it spreads diseases. There was a cholera outbreak a while back in cell three, [which made] 15 inmates [sick].”[206] Unclean bathing facilities also lead to illness. In the ablution block, Moono, a teenager at Lusaka Central, told us, “we end up contracting skin diseases, and there is no proper water.”[207]

The Prisons Service does not provide basic necessities to prisoners, and they are left instead to rely on family members, church donations,[208] or an exchange of sex or labor in order to obtain soap, razors, sanitary pads, and items essential to proper hygiene. International standards require that prisoners shall be provided with toilet articles necessary for health and cleanliness, as well as razors.[209] Zambian law provides that, if an unconvicted prisoner does not provide himself with food and clothing, “he shall receive normal prison food, clothing, and other necessaries”[210] and that convicted prisoners receive these essentials. Yet such articles are not provided. As Catherine, 38, described,

The prison does not provide us with soap, toothpaste, or sanitary pads. If others don’t bring them for us, we have nothing. There are lots of people with no relatives here. They have nothing....Some people have no relatives—if you have no food, you are nobody in this place. You can trade a cup of sugar for work.[211]

The unavailability of soap leads to poor hygiene: As the HIV/AIDS coordinator at Lusaka Central reported, “hygiene is a big problem—no toothpaste, soap, clean clothing, and mattresses are not clean. There are not enough blankets, and no sheets—prisoners get cold. They have no spares, so they cannot wash them.”[212] Inmates routinely rely on shared razor blades,[213] or used razor blades,[214] very high risk behavior that promotes transmission of Hepatitis and HIV. Additionally, inmates are not provided with basic cleaning materials such as gloves and disinfectant in order to clean the latrines or toilet buckets.[215]

International standards require that prisoners be issued separate and sufficient bedding that is “clean when issued, kept in good order and changed often enough to ensure its cleanliness.”[216] Yet in Zambia, mattresses and blankets are filthy and go for months without being washed,[217] in violation of international standards. As Jacob, 26, an inmate at Mwembeshi, told us, “the blankets, they are not clean. Since I came, they have not been cleaned. Someone told me they have not been cleaned since 2005. There are lice and dust in all of them.”[218] Vermin, lice, and cockroaches are commonplace. Indeed, at Mwembeshi, another inmate, 26, reported that “one captain does not let people kill the lice—it is just to be mean and mock them.”[219] Mary, 27, who sleeps by the storeroom at Lusaka Central, had insects enter her ear in the night, and she had to be taken to the hospital.[220]

Uniforms are not provided to remandee prisoners, and clothing provided to convicts is grossly inadequate.[221] Female inmates are given uniforms designed for male inmates.[222] Some of the inmates at each prison are entirely without shoes; others wear only a single shoe. Others wear only half a uniform. The officer in charge at Choma confirmed that while convicted prisoners are meant to be provided with one prison uniform, the uniforms have run out, and often uniforms are taken from older convicts to give to the new.[223] Marlon, 17, in rags, noted simply “I have no proper clothes.”[224] “Some people are walking naked, with no uniforms,” Reynard, 35, observed.[225] With only one set of clothing, inmates are forced to wear their uniform at all times, even when wet.[226] Mwape, 47, at Mukobeko, declared, “I have only one torn t-shirt, one old short, and a pair of sandals to survive on the remaining 11 years of my 17 year sentence.”[227] Mwisa, 29, an inmate at Choma, expressed the toll that inadequate clothing takes on the psyches of inmates: “We have no coats in winter, and people fall ill. It’s a matter of health, but also of dignity. How can one be dignified when begging for clothes?”[228]

Mosquito nets are not provided, despite frequent cases of malaria, and only a few personally owned nets were present at some of the prisons we visited. Sylvia, age 70, informed us that in her cell, “we have two major problems: One, plenty of mosquitoes, and two, no nets.”[229]

Rape

Studies have documented the occurrence of sexual activity inside Zambian prisons,[230] and even the former president has acknowledged this fact.[231] Overcrowding in prisons has been shown to contribute to sexual violence.[232] Our findings suggested a high prevalence of sexual activity between male (but not female) inmates, including consensual sex between adults and the adult relationships described above in which sex was traded for food. PRISCCA, ARASA, and Human Rights Watch also heard reports of rape. Sexual activity was reported at Mukobeko, Kamfinsa, and Lusaka Central prisons, and less frequently at Mumbwa, Mwembeshi, and Choma prisons.

Although there is no general definition of rape in international human rights law, rape has been authoritatively defined as “a physical invasion of a sexual nature, committed on a person under circumstances which are coercive.”[233] Under Zambian law, rape is a gendered crime and may only be committed against a woman. Sexual activity with children under age 16 constitutes defilement under Zambian law.[234] In Zambian prisons, children are frequently forced into sexual relationships constituting rape, particularly when they are held with adult prisoners. At the time of our visit to Mukobeko, three juveniles were held in a cell with three adults— two of the adults in the cell were in prison on charges of defilement of a minor.[235]

Chris, 17, reported that:

I have witnessed sexual abuse. One of the older inmates who was put into our cell to sleep at night started showering my cellmate, a juvenile, with gifts. He promised him money in return for sexual favors. My friend wasn’t happy, and neither did he consent. But the other imposed himself by buying him off with gifts, and saying that there was 100,000 kwacha [US$21] waiting for him “at the reception”. When the older inmate finally approached him sexually, my friend was intimidated, but managed to shout and attracted the attention of the other juveniles. Unfortunately we reported it to the officer on duty at night, and he promised to address it the next day, but he didn’t. The cell captain intervened, though, and removed the man, putting him into one of the other cells....Do I feel safe? No, I don’t feel safe.[236]

David, a teenager at Lusaka Central, reported that “I haven’t physically been abused, because I know the system, and avoid enticements. But my more vulnerable friends fall prey. Once you eat the food, they reprimand you, say you have no choice. I have seen it happen. It pains me to see the pain they undergo as juveniles.”[237] Moono, a teenager at Lusaka Central, concluded: “Mainly the juveniles are very vulnerable. As young people coming into prison, we are full of fear. The convicts take advantage of us by providing us with food and security. We enter their dragnet, but by the time we discover this it is too late.”[238]

Sometimes adults become victims of male rape, too. Evans, 43, a remandee at Lusaka Central, concluded:

Sometimes when you are sleeping someone gets under you. He’s already in your anus. Others wake up, and catch that man....They are brought before the authorities. Sometimes they overlook it, or the officer in charge can take you to the courts of law.[239]

We found, however, that significant denial among the officers exists as to the occurrence of sexual activity: the officer in charge at Mukobeko informed us that no prisoners were engaged in sexual activity to his knowledge,[240] but the deputy officer in charge at Mukobeko admitted that he “had learned of fights between inmates of prisoners fighting over sexual and romantic partners.”[241] Furthermore, a prison officer at Mukobeko told us that he received roughly three reports a month of sexual activity and that “captains are empowered to attend to this.”[242] At Kamfinsa, Patrick Mundianawa, the officer in charge, said that there is “almost no sexual activity at the prison,” only attempts.[243] At Lusaka Central, the officer in charge admitted that “there is a small amount of sexual activity in the prison. When it happens, cell leaders report and we investigate. We rush the victim to the hospital for physical exam. If it is confirmed, the aggressor is taken to court. We always punish someone because it can’t be acceptable as if we did that it would get out of hand.”[244] “I don’t know, I haven’t heard any complaints,” the officer in charge at Mumbwa demurred,[245] but the deputy officer in charge, D. Mulenga, told us that he was aware of cases of consensual sex.[246] The officer in charge at Choma reported that there was no sexual activity in the prison currently.[247]

The Availability and Quality of Medical Care

International law dictates that prisoners be provided with health care at least equivalent to that available in the general community.[248] Health care currently provided in Zambian prisons falls far short of international standards. TB and HIV present specific challenges.

Tuberculosis

The isolation cells are death traps.

– Dr. Chileshe, director, Zambia Prisons Service Medical Directorate, October 13, 2009

TB Transmission

The conditions at each prison visited by PRISCCA, ARASA and Human Rights Watch—combining overcrowding, minimal ventilation, and a significant immuno-compromised population—are ripe for the quick spread of TB, confirmed by suspected high prevalence. As noted above, a 2000-2001 study in 13 Zambian prisons for pulmonary TB among inmates concluded that a high rate of pulmonary TB exists in Zambian prisons, speculating that true prevalence rates may approach 15-20 percent;[249]the Zambia Prisons Service has reported a case infection rate for TB of 5,285 cases per 100,000 inmates per year.[250] High turnover exists in the prison population, so spread of TB to the general public by released inmates is also a significant risk.[251] As an officer at Mwembeshi noted, “The cells are meant to accommodate 10 but they hold 135. The men don’t sleep well. If one has TB, four or five have it. Before it is identified, it has already spread.”[252]

Interviews with inmates and prison officers established that there exists a strong awareness of the possibility of transmission, and a deep fear of both contracting TB and spreading it within the community.[253] As one prison officer at Kamfinsa said, “we need to care for and prevent some diseases like TB. If so many people are sick, the officers can be affected. We necessarily worry about getting TB at our work. If I am sick, I can transfer it to my family. It worries us.”[254] According to an inmate, “the ventilation is not good. There is coughing and TB in the cells. It takes time to be detected, but by the time they detect it, the TB will have spread to many of our fellows. It keeps us worried.”[255] Dr. Chileshe confirmed: “They say, ‘you’re going to Chimbokaila [Lusaka Central Prison]? It’s a death sentence.’ Not because they are afraid you will be given beatings, but because of TB. They know the conditions are bad.”[256]

Children incarcerated at Mukobeko have shared living quarters with the TB isolation cell. The children fear TB patients—“I am worried I will catch TB. There is no window, just a small opening with wire over it—not much ventilation,” Phiri, 17, said.[257] Isaac, 17, at Mukobeko, reported that there were “23 TB patients in my living area. There are no vents, no air. I’m worried.”[258] The officer in charge of Lusaka Central prison acknowledged that the lack of ventilation was a severe problem.[259]

TB Testing