"The BestSchool"

Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte d'Ivoire

"FESCI is the best school for leaders there is. You come out battle hardened and ready to do politics. Ours is a generation that had to come to power one day, so if you see members of FESCI rising up, our view is that it was inevitable and came later than it should have. The arrival of this class will change politics."

-Former leader of the Student Federation of Côte d'Ivoire, interviewed by Human Rights Watch, October 2007

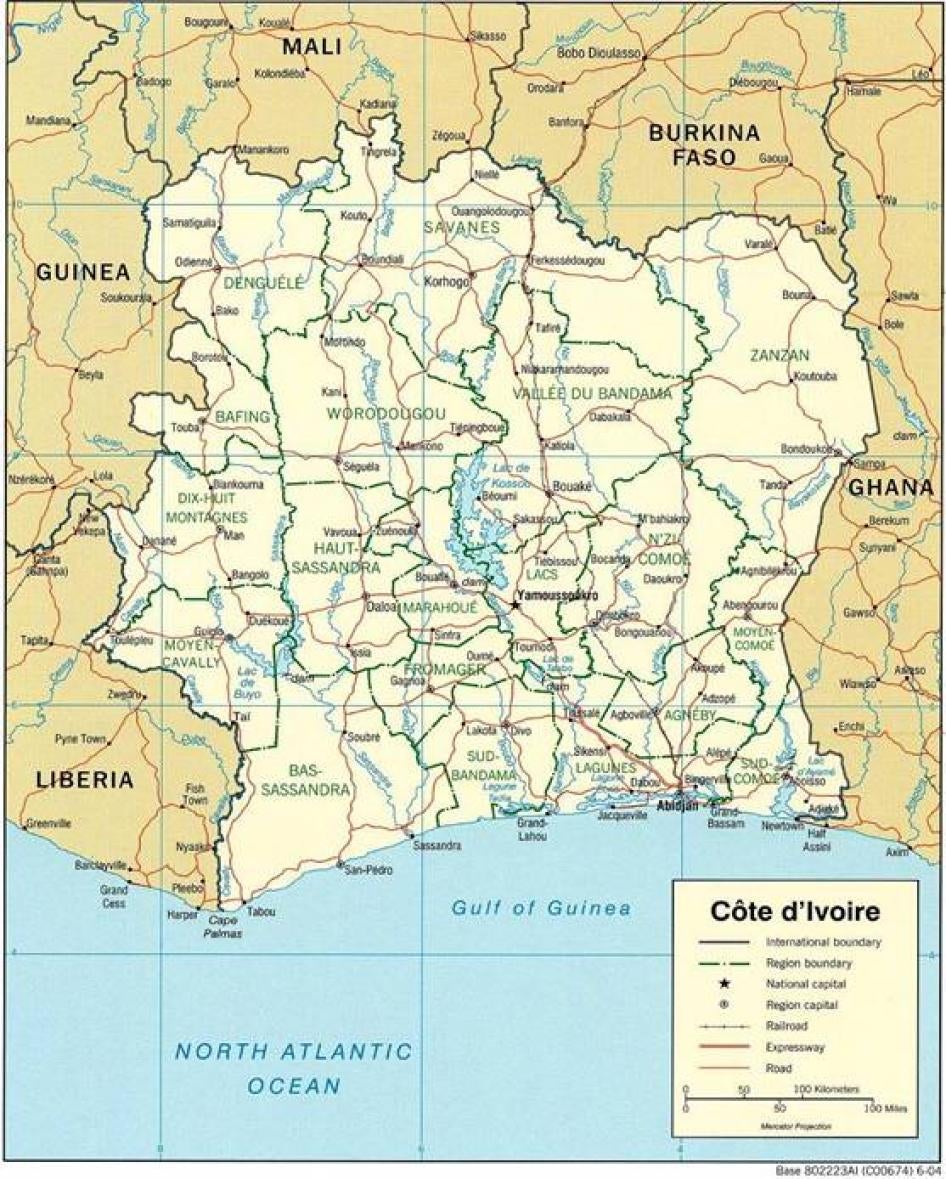

Map of Côte d'Ivoire

Courtesy of The General Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

Glossary of Acronyms

AGEECI |

Association Générale des Élèves et Étudiants de Côte d'Ivoire (General Student Association of Côte d'Ivoire). |

APDH |

Actions pour la Protection des Droits de l'Homme (Actions for the Protection of Human Rights). |

CECOS |

Centre de Commandement des Opérations de Sécurité (SecurityOperationsCommandCenter), an elite rapid-reaction force charged with fighting crime in Abidjan whose members are drawn from the army, the gendarmerie, and the police. |

COJEP |

Congrès Panafricain des Jeunes Patriotes (Panafrican Congress of Young Patriots), commonly known as the Jeunes Patriotes (Young Patriots). |

CROU |

Centre Régional des Œuvres Universitaires (University Accommodations Center). |

FANCI |

Forces Armées Nationales de Côte d'Ivoire (National Armed Forces of Côte d'Ivoire). |

FDS |

Forces de Défense et de Sécurité (Defense and Security Forces), a term used to refer collectively to the army (FANCI), the gendarmerie, and the police. |

FESCI |

Fédération Estudiantine et Scolaire de Côte d'Ivoire (Student Federation of Côte d'Ivoire). |

FN |

Forces Nouvelles (New Forces), alliance of three different armed movements that initiated the rebellion in the north of Côte d'Ivoire in 2002. |

FPI |

Front Populaire Ivoirien (Popular Ivorian Front), the ruling party of President Laurent Gbagbo. |

JFPI |

Jeunesse du FPI (Youth wing of the FPI party). |

JRDR |

Jeunesse du RDR (Youth wing of the RDR party). |

LIDHO |

Ligue Ivoirienne des Droits de l'Homme (Ivorian League for Human Rights). |

MIDH |

Movement Ivoirien des Droits de l'Homme (Ivorian Movement for Human Rights). |

MJP |

Movement pour la Justice et la Paix (Movement for Justice and Peace), armed rebel movement that emerged in Western Côte d'Ivoire in 2002, later integrated into the New Forces. |

MPCI |

Mouvement Patriotique de Côte d'Ivoire (Patriotic Movement of Côte d'Ivoire), armed rebel group who seized control of northern Côte d'Ivoire in 2002, the largest single constituent of the New Forces. |

MPIGO |

Mouvement Populaire Ivoirien du Grand Ouest (Ivorian Popular Movement for the Great West), armed rebel movement that emerged in Western Côte d'Ivoire in 2002, later integrated into the New Forces. |

ODELMU |

Observatoire des Droits et des Libertés en Milieu Universitaire (University Rights and Freedoms Watch). |

ONUCI |

Opération des Nations Unies en Côte d'Ivoire (United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire). |

PCRCI |

Parti Communiste Révolutionnaire de Côte d'Ivoire (Revolutionary Communist Party of Côte d'Ivoire), opposition party led by Ekissi Achy. |

PDCI-RDA |

Parti Démocratique de Côte d'Ivoire – Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire – Democratic African Gathering), the ruling party from independence in 1960 until the 1999 coup d'état. Currently an opposition party led by former president Henri Konan Bédié. |

RDR |

Rassemblement des Républicains (Rally of Republicans), opposition party led by former prime minister Alassane Dramane Ouattara. |

RHDP |

Rassemblement des Houphouétistes pour la Démocratie et la Paix (Gathering of Houphouetists for Democracy and Peace), alliance of opposition parties including the PDCI, RDR, and UDPCI. |

RTI |

Radio-Télévision Ivoirienne (Ivorian Radio-Television), the national television station. |

SOAF |

Solidarité Africaine (African Solidarity). |

UDPCI |

Union pour la Démocratie et la Paix en Côte d'Ivoire (Union for Democracy and Peace), opposition party created by Côte d'Ivoire's former military ruler, General Robert Gueï, currently led by Albert Mabri Toikeusse. |

UPLTCI |

Union pour la Liberation Totale de la Côte d'Ivoire (The Union for the Total Liberation of Côte d'Ivoire). |

Summary

The government of Côte d'Ivoire has demonstrated a sustained and partisan failure to investigate, prosecute, or punish criminal offenses allegedly perpetrated by members of a student group called the Student Federation of Côte d'Ivoire (Fédération Estudiantine et Scolaire de Côte d'Ivoire, FESCI). Most FESCI members are staunch partisans of President Laurent Gbagbo, once a university professor, and his ruling Popular Ivorian Front party (Front Populaire Ivoirien, FPI). Today, FESCI is alternatively described by journalists, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and even Ivorian government officials as a violent "pro-government militia" or a "mafia."

Since at least 2002, FESCI has been responsible for politically and criminally motivated violence, including assault, extortion, and rape, often targeting perceived opponents of the ruling party. In the last several years, members of FESCI have been implicated in attacks on opposition ministers, magistrates, journalists, and human rights organizations, among others. Students considered associated with the northern-based rebellion or the political opposition have been murdered, raped, and severely beaten. In addition, FESCI is routinely associated with "mafia" type criminal behavior including extortion and protection rackets involving merchants working in and around university and high school facilities. In tandem with other pro-government youth groups such as the Young Patriots, FESCI's members have been repeatedly mobilized since 2002 to stymie Côte d'Ivoire's peace process at key junctures to the benefit of the FPI party.

In principle, FESCI is a non-partisan student union established to represent the entirety of the student body and to seek improvement in the conditions experienced by students attending university and high school. It began as a pro-democracy student group in early 1990 intent on pressing for reform of one-party rule. Branded as subversive by the government at the time, the organization was formally banned and forced underground soon after its creation, with many of its leaders hunted and jailed, only to re-emerge in 1997.

The story of FESCI's transformation from activists for multiparty democracy to political partisans, and from victims of government persecution to perpetrators of violent crimes with government protection, closely follows the tumultuous history of Côte d'Ivoire in the last two decades.

Since 2000, Côte d'Ivoire has been racked by a social, political, and military crisis that has accelerated economic decline, deepened political and ethnic divisions, and led to a scale of human rights abuses previously unseen in the nation's post-independence history. The crisis has in many ways been a story of the frustrations and alienation of Ivorian youth. During the past eight years, members of youth groups have both helped to foment armed rebellion resulting in an unsuccessful 2002 coup attempt-dividing the country between a rebel-controlled north and government-controlled south-and joined pro-government militias to fight against it. Youth groups have served as both pawns in a proxy war between rival political and military forces as well as leading protagonists in the unfolding drama and crisis that has engulfed the nation. FESCI is the cradle in which most of these youth movements were nurtured.

This report describes FESCI's roots and actions, together with the government's complacency, and at times complicity, in the violence and crimes perpetrated by FESCI members.

Since at least 2002, particularly in Abidjan's university system, FESCI has controlled many aspects of campus life, from who can live in a dorm room to which merchants are allowed to sell food to students. Some students, particularly those from a rival student organization perceived by FESCI to have sympathy for the rebels, fear to set foot on campus due to previous FESCI-led attacks on their members. Together, FESCI's actions, both on and off campus, have a chilling effect on the freedoms of expression and association for fellow students and professors. The fear FESCI generates casts a shadow over the openness of debates and public meetings, and forces rival student organizations to drastically curtail public activities.

FESCI-perpetrated attacks of the kind described in this report have been carried out with near-total impunity, often under the passive eye of government security forces, including the police and gendarmes. On a few occasions, security forces have directly participated in human rights violations with FESCI members. This impunity has served to embolden FESCI members, who appear to feel themselves untouchable, and has resulted in the quasi institutionalization of violence in the university environment.

Many of the acts of violence involving FESCI members described in this report have been well publicized in the Ivorian press and were well known to police, judges, and other government officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch. Several of FESCI's victims have filed formal complaints with the appropriate authorities. However, in very few instances has a member of FESCI been investigated, much less tried and convicted. Those interviewed-from students and professors to policemen and judges-maintain that FESCI benefits from near total impunity due to its staunch support of President Gbagbo and his ruling FPI party.

FESCI has become a training ground for emerging Ivorian leadership. Guillaume Soro, the head of the New Forces rebels, and current prime minister in a unity government, led FESCI from 1995 to 1998. Charles Blé Goudé, head of Côte d'Ivoire's Young Patriots ultranationalist pro-government group, led FESCI from 1999 to 2001. The youth wings of several major political partiesare or have been headed by former FESCI leaders.

Côte d'Ivoire's higher-educational system appears to be producing a generation of leaders who have cut their political teeth in a climate of intimidation, violence, and impunity, an environment in which dissent and difference of opinion are violently repressed. Such a system is not "the best school" for Ivorian democracy-and the government of Côte d'Ivoire should take immediate, concerted action to change it.

The government of Côte d'Ivoire has obligations under international human rights law to respect the right to life, right to bodily integrity, right to liberty and security of the person, and the rights to freedom of expression, association, and assembly-including by acting to prevent and prosecute private actors who are responsible for the infringement of these rights. Yet FESCI members have been able to commit crimes with near-total impunity.

The sense shared by many Ivorians that pro-government groups like FESCI are effectively "above the law" due to their allegiance to the ruling party erodes respect for bedrock institutions essential to building the rule of law such as impartial and independent courts and rights-respecting police, and undermines long-term prospects for the creation of a peaceful society.

Putting an end to the violence that has become synonymous with university life in Côte d'Ivoire will require sustained commitment by the government, especially the Ministries of Higher Education, Interior, and Justice. An important first step would be the establishment of a joint task force that meets regularly to monitor violence and other criminal activity in and around schools, and coordinates appropriate action in response.

Ending the impunity that allows violent activity to continue undeterred will require political will from the highest levels of the state, as well as the leaders of Côte d'Ivoire's leading political parties, who must commit to supporting investigation and prosecution of crimes by youth groups such as FESCI both on and off campus. In addition, in upcoming presidential elections, political parties must help initiate a national dialogue on the subject of violence in schools and universities by articulating a platform for its mitigation. This will be critical to stem possible violence during the upcoming presidential elections, currently scheduled for late November.

Recommendations

To the Presidency

- Publicly denounce student violence, particularly by student organizations, and call upon student leaders to ensure that their organizations and members abide by the law and school regulations.

- Publicly commit to supporting the investigation and prosecution of human rights abuses and criminal activity carried out by pro-government groups such as FESCI.

- Establish a joint task force with members drawn from the Ministries of Higher Education, Interior, and Justice to meet regularly to monitor the violence in and around schools and coordinate appropriate action in response to criminal activity and threats to academic freedom.

To the Ministry of Justice

·Investigate and prosecute FESCI members implicated in violent crimes including murder, assault, rape, and other mafia-like practices, such as extortion and protection rackets, in and around universities and high schools.

To the Ministry of Interior

·Issue clear public orders to the police and other security forces to ensure that FESCI and other student groups, regardless of their political affiliations, are brought within the scope of the law and cannot act with impunity.

·Establish a dedicated police unit with special authority and responsibility to patrol and maintain law and order on university campuses and residences.

To the Ministry of Higher Education

- In collaboration with civil society (including student organizations, teachers' organizations, and human rights organizations), revise and expand the student code of conduct to emphasize, in particular, the importance of respect for human rights in the educational context, and to set forth clear disciplinary measures to be taken in the event of code-of-conduct violations.

- Engage in awareness-raising activities on campus to promote the revised student code of conduct.

- Take appropriate disciplinary action (including suspension from campus and/or referral for police investigation, where appropriate) against those implicated in campus violence and criminality.

- Work closely with university authorities to develop measures to end improper control over university facilities, including dormitories, by FESCI and other student organizations. Institute disciplinary action and seek, where appropriate, criminal prosecutions of students and groups engaged in such activities.

To all Political Parties

- Publicly dissociate from any student organization that repeatedly engages in unlawful activity.

- Commit to referring for police investigation alleged criminal activity carried out by student and other youth groups.

- In upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections, help initiate a national dialogue on the subject of violence in schools and universities by presenting a platform for its mitigation.

To the National Bureau of FESCI

- Take action to discourage and prevent crime by FESCI members, including by publicly denouncing past unlawful practices, instituting internal control mechanisms and education programs, and creating and enforcing organizational rules of conduct. Expel members involved in criminal activity.

- In collaboration with government ministries and members of civil society (including other student organizations, teachers' organizations, and human rights organizations), participate in the drafting of a revised student code of conduct; publicly pledge to abide by its requirements; and cooperate with university officials in enforcing the code against FESCI members.

- Cooperate with police investigations into alleged crimes committed by members of FESCI, including recent attacks on human rights organizations.

- Publicly endorse and participate in the activities of University Rights and Freedoms Watch (Observatoire des droits et des libertés en milieu universitaire, ODELMU), a center for civic and non-violence education on the university campus run by the Ivorian League for Human Rights (LIDHO).

To Local Human Rights and other Civil Society Organizations

·Continue to implement and expand a sensitization campaign in schools and universities regarding human rights and non-violent methods of social change.

·Help to promote greater national dialogue on the problem of violence in schools and universities by raising the issue in local media and public forums, and with political parties.

To the United States, France, the European Union, and other International Donors

·Call publicly and privately on the Ivorian government to investigate, and where applicable punish in accordance with international standards, those members of pro-government groups responsible for crimes, including murder, rape, assault, and extortion.

·Provide support to government and civil society programs that promote campus reconciliation, non-violent methods of social change, and human rights sensitization.

Methodology

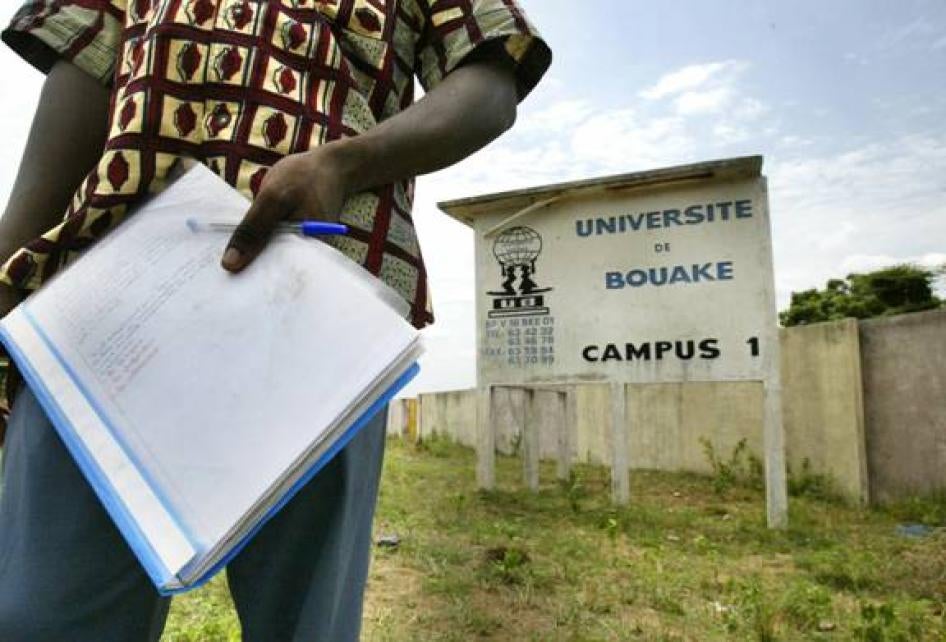

This report is based on field research conducted during August, September, and October 2007 in Abidjan and Bouaké, Côte d'Ivoire. As part of this research, Human Rights Watch interviewed over 50 current and former university students, including the leaders of seven different student unions and associations. The large majority of students interviewed identified themselves as either current or former members of FESCI. Of the 50, five were interviewed in small groups, and the rest were interviewed individually.

In addition to students, Human Rights Watch interviewed Ivorian university professors; high school teachers; police officers; judges; current and former officials with the Ministries of Higher Education, Justice, and Interior; representatives from the New Forces rebels;[1] representatives from the United Nations Mission in Côte d'Ivoire (ONUCI); diplomats; officials working in a mayor's office; journalists; transporters unions; and merchants operating near university facilities.

In addition to this 2007 research, in previous missions to Côte d'Ivoire since 2000, Human Rights Watch has tracked and documented violence perpetrated by members of pro-government groups such as FESCI. Those missions involved interviews with a wide circle of sources including victims of FESCI abuses, diplomats, United Nations officials, members of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and Ivorian government officials from all sides. Some of this research has been used in the present report.

Care was taken with victims to ensure that recounting their experience did not further traumatize them or put them at physical risk. The interviews were conducted in French. The names of all witnesses to incidents have been withheld in order to protect their identity, privacy, and security. At their request, the names of police, judges, and several other government officials have been withheld due to security concerns. Human Rights Watch identified victims and eyewitnesses through the help of several local organizations, all of whom requested that their identities remain confidential.

General Background on the Military-Political Crisis in Côte d'Ivoire

For 30 years following independence in 1960, Côte d'Ivoire enjoyed relative stability and economic prosperity under the leadership of President Felix Houphouët-Boigny, an ethnic Baoulé and Roman Catholic from the geographic center of the country. The pillars of Houphouët-Boigny's post-independence political and economic policy included a focus on export-driven agriculture as a development strategy, an open-door immigration policy, and extremely close ties with the former colonial ruler, France, which assured the government's security. During these years, Côte d'Ivoire become a key economic power in West Africa, a global leader in cocoa and coffee production, and a magnet for migrant workers who would eventually come to make up an estimated 26 percent of its population.[2]

While Côte d'Ivoire may have been the economic motor of the sub-region, it was not a model for governance and accountability. Houphouët-Boigny's Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire (Parti Démocratique de la Côte d'Ivoire, PDCI) monopolized political activity in an autocratic, single-party state. While his PDCI governments nominally reflected the ethnic and religious make-up of the country, maintenance of power was based on an "ethnic coalition" strategy involving groups from Côte d'Ivoire's north and center.[3]Many southern and western groups felt excluded and politically frustrated under Houphouët-Boigny's reign.[4]

In the late 1980s, the "Ivorian miracle" began to flounder on the rocks of plummeting cocoa prices and rising foreign debt, leading to a serious economic recession. The foundations of Houphouetism began to crumble. Combined with the impact of structural adjustment measures imposed by international financial institutions and donors, the recession affected not only the cocoa and coffee sector, but also general employment opportunities. As a result, an increasing number of educated urban youth could not find work.[5] As joblessness and frustration rose, so too did pressure from opposition parties and civil society (including trade unions and student groups) to reform and democratize Côte d'Ivoire's one-party state.

Battle for Succession

The death of Houphouët-Boigny in 1993 marked the formal beginning of an overt battle for political succession that would bring Côte d'Ivoire to the brink of disaster. As candidates representing the principal ethnic and geographic blocs began vying for the presidency in the run-up to the 1995 elections, questions of ethnicity and nationality came to the fore.[6] In order to exclude rivals, politicians began to employ the rhetoric of "Ivoirité" (or "Ivorianness")-an ultranationalist and exclusionary political discourse focusing on Ivorian identity and the role of immigrants in Ivorian society that marginalized perceived outsiders.[7]

The opposition party, Rally of Republicans (Rassemblement des Républicains, RDR), which since its formation has been dominated by Ivorians from the largely Muslim north, boycotted the 1995 election after the candidacy of former prime minister Alassane Dramane Ouattara was effectively barred.[8] Voicing concerns about transparency, the Popular Ivorian Front opposition party (Front Populaire Ivoirien, FPI) led by current president Laurent Gbagbo also boycotted the election, and Henri Konan Bédié of the PDCI won with 96 percent of the vote.

During Bédié's six-year rule, allegations of corruption and mismanagement multiplied, and he increasingly relied on ethnic favoritism to garner support in an unfavorable economic climate. Political opposition groups, including the RDR and FPI, formed an alliance to combat this "misrule" called the Republican Front. This coalition later disintegrated due to internal friction.

The 1999 Coup and 2000 Elections

In December 1999, General Robert Gueï, a Yacouba from the west and former army chief of staff, took power in a coup following a mutiny by non-commissioned officers.[9] Nicknamed "Santa Claus in camouflage," Gueï was initially applauded by most opposition groups as a welcome change from the longstanding PDCI rule and Bédié's corrupt regime. However, Gueï's pledges to eliminate corruption and introduce an inclusive Ivorian government were soon overshadowed by his personal political ambitions, the repressive measures he used against both real and suspected opposition, and near-total impunity for human rights abuses by military personnel.[10]

Throughout 2000, Ivorian politics became increasingly divided along ethnic and religious lines. Elections in this inauspicious climate would prove to be, in the words of President Gbagbo, the winner of those elections, "calamitous."[11]

Several weeks before the October presidential election, the government deemed the majority of candidates ineligible, including both Alassane Ouattara of the RDR and former president Bédié of the PDCI, resulting in an electoral contest between Laurent Gbagbo's FPI party and General Gueï.When it became clear that Gbagbo had the upper hand on election day, Gueï attempted to disregard entirely the election results and seize power, leading to massive popular protests and the loss of military support. General Gueï fled the country on October 25, 2000 and Laurent Gbagbo was installed as president a day later.

Soon after Gueï's flight, RDR supporters-calling for new elections "with no exclusion"-clashed with FPI supporters and were targeted by government security forces, resulting in many deaths. The killings, the most violent episode of political violence in Côte d'Ivoire's post-independence history, shocked Ivorians and members of the international community alike, grimly highlighting the danger of manipulating ethnic loyalties and latent prejudice for political gain.[12]

Efforts by President Gbagbo to include members of opposition parties in his government were seen as largely symbolic, and throughout 2001-2002 political tensions remained high.

The 2002 War

On September 19, 2002, rebels from the Patriotic Movement of Côte d'Ivoire (Mouvement Patriotique de Côte d'Ivoire, MPCI), whose members are drawn largely from the predominantly Muslim north of the country, attacked Abidjan, the commercial and de facto capital of Côte d'Ivoire, and the northern towns of Bouaké and Korhogo.[13] The rebels' stated aims were the redress of recent military reforms, new elections, an end to political exclusion and discrimination against northern Ivorians, and the removal of President Gbagbo, whose presidency they perceived as illegitimate due to flaws in the 2000 elections. Although they did not succeed in taking Abidjan, the rebels encountered minimal resistance and quickly managed to occupy and control half of the country. Rapidly joined by two other western rebel factions, they formed a political-military alliance called the New Forces (Forces Nouvelles, FN).[14]

The armed conflict between the government and the New Forces ended in May 2003 with the signature of a total ceasefire agreement.[15] Since 2003, the country has effectively been split in two with the New Forces based in Bouaké, controlling the land-locked north, and the government holding the south, where the majority of the country's estimated 20 million inhabitants live.

Peace Agreements

Since the end of hostilities in 2003, France, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the African Union, and the United Nations have all spearheaded initiatives to end the political-military stalemate in Côte d'Ivoire. These efforts resulted in a string of unfulfilled peace agreements, a peak of over 11,000 foreign peacekeeping troops on the ground to prevent all-out war and to protect civilians, and the imposition of a UN arms embargo in addition to travel and economic sanctions.[16]

In March 2007 President Gbagbo and rebel leader Guillaume Soro signed a peace accord negotiated with the help of Burkina Faso President Blaise Compaoré ("The Ouagadougou Agreement"), and later endorsed by the African Union and the United Nations Security Council.[17] The Ouagadougou Agreement is the first to have been directly negotiated by the country's main belligerents on their own initiative and resulted in the appointment of Guillaume Soro as prime minister in a unity government. Implementation efforts following signature have resulted in important milestones in the peace process, even if accomplishment of major prerequisites to elections, including voter registration and disarmament, has thus far been lacking.[18] Presidential elections are currently scheduled in late November, some three years beyond the expiry of President Gbagbo's constitutional mandate.[19]

The Human Rights Fallout from the Crisis

The human rights fallout from the crisis for civilians living on both sides of the political-military divide has been and continues to be devastating.[20] Political unrest and the impasse following the 2002-2003 armed conflict between the government and northern-based rebels have been punctuated by atrocities and serious human rights abuses attributable to both sides including extrajudicial killings, massacres, sexual violence, enforced disappearances, and numerous incidents of torture. These abuses have been continued in large measure due to a prevailing culture of impunity.

Rebels in Côte d'Ivoire carried out widespread abuses against civilians in some areas under their control. These included extrajudicial executions, massacres, torture, cannibalism, mutilation, the recruitment and use of child soldiers and sexual violence including rape, gang rape, egregious sexual assault, forced incest, and sexual slavery. Liberian combatants fighting alongside Ivorian rebel groups were responsible for some of the worst crimes. However, even after their departure, various forms of violence have continued.

In response to the rebellion, government forces and government-recruited Liberian mercenaries frequently attacked, detained, and executed perceived supporters of the rebel forces based on ethnic, national, religious, and political affiliation. Even after the end of active hostilities, state security forces assisted by pro-government groups such as the Jeunes Patriotes ("Young Patriots" or JP) regularly harassed and intimidated the populace, particularly those believed to be sympathetic to the New Forces rebels or the political opposition. Security forces in government-controlled areas regularly extorted and physically abused Muslims, northerners, and West African immigrants, often under the guise of routine security checks at roadblocks.

On both sides of the political and military divide, the most horrific human rights abuses peaked from roughly 2002 to 2004, and have declined in recent years. However, more chronic human rights abuses persist and go unaddressed; most notably, government security forces and New Forces rebels who continue to engage in widespread extortion at checkpoints and, on a more limited scale, sexual violence against girls and women.

A nation divided, Côte d'Ivoire is only beginning to emerge from the most serious political and military crisis in its post-independence history. Widespread criminality in the university context involving student groups has taken place and continues to occur against this backdrop of instability, violence, and impunity.

Student Activism in the 1990s; from Clandestinity to Political Schism

A Tumultuous Birth

By the end of the 1980s, Ivorian civil society and the political opposition were at a boiling point. Frustration with years of one-party rule, together with a declining economy and decreasing job prospects for youth, led to increasingly widespread protests to pressure the government for multiparty elections. In the vanguard of the early-1990s protest movement were Laurent Gbagbo's socialist FPI party and the closely associated student group, FESCI.

FESCI was created in April 1990, and, together with trade unions and leftist political parties, was instrumental in mobilizing demonstrations throughout 1990 and 1991 against PDCI rule.[21] FESCI was supported financially and otherwise by a number of nascent leftist opposition parties, including the FPI.[22] From its inception, Houphouët-Boigny and his PDCI party viewed FESCI as an instrument of the political opposition and therefore subversive.

After months of intense pressure, Houphouët-Boigny agreed to the legalization of political parties in May 1990. Later that year, for the first time in Côte d'Ivoire's history, Ivorians witnessed presidential elections with Houphouët-Boigny facing another candidate, FPI's Gbagbo. Houphouët-Boigny won the elections with 82 percent of the vote and opposition parties criticized electoral irregularities. Dissatisfied with the reforms offered, the student demonstrations and pressure from opposition parties continued.[23]

FESCI is Driven Underground

In the early 1990s, violent clashes between FESCI members and government security forces led to an official ban on FESCI as an organization, forcing its members underground.

In May 1991, three days of tension and violent student-police clashes on the university campus took place after students claimed that they were attacked by pro-government thugs while planning a news conference on cramped conditions in the university. Security forces violently dispersed angry students who hurled stones and burned cars.[24] Later that same week, the army, led by its chief of staff Robert Gueï, conducted a brutal night raid on a student dormitory in the Abidjan neighborhood of Yopougon. Gueï was promoted to general soon after.

In June 1991, students allegedly belonging to FESCI bludgeoned to death a suspected PDCI government informant on campus, Thierry Zebié. Eight students were arrested, and Prime Minister Alassane Ouattara, in a nationally broadcast speech, announced that FESCI was being dissolved immediately. FPI leader Gbagbo, a university professor, reportedly said that FESCI had committed no crime and that Ouattara's speech was "a great mistake."[25] Pursued by the authorities, most FESCI leaders went underground.

In January 1992, a government commission established to investigate General Gueï's May 1991 raid on the Yopougon dormitory concluded that soldiers raped at least three girls and viciously beat students, and that "the sole initiative" for the savage raid lay with General Gueï. The commission recommended that Gueï be sanctioned.[26] When Houphouet-Boigny refused to follow the commission's recommendations, saying he did not wish to divide the army, students staged weeks of violent protests, clashing with police, burning tires, smashing windows and doors in campus buildings, and setting fire to vehicles, leading to hundreds of arrests.[27] Laurent Gbagbo, FESCI founder Martial Ahipeaud, and president of the Ivorian League for Human Rights (Ligue Ivoirienne des Droits de l'Homme, LIDHO) René Dégni Ségui, were arrested and sentenced to between one and three years of prison, but were freed months later.[28]

Continued Clashes in the mid-1990s

Student strikes, boycotts, and demonstrations in the years following the death of Houphouët-Boigny focused, at least at one level, on traditional student issues, including overcrowding on campus and scholarships. At the same time, for many students, such actions were nevertheless felt to be "political" or "anti-PDCI" acts taken against a corrupt and undemocratic government thought disinclined to better their lot.[29] Continuing the government's "tough" stance, in 1995, then-Minister of Security Marcel Dibonan Koné stated at a press conference that anyone claiming to be a member of FESCI would be considered an "outlaw."[30]

FESCI's planning meetings and press conferences during this era were often broken up brutally by police raids. Hundreds of FESCI members and leaders were arrested, held incommunicado, and most often released without charge. Many endured harsh conditions including deprivation of food, beatings, and torture while detained.[31] Nearly all of FESCI's leaders in the 1990s spent time in jail,[32] and a number of its leaders, including its founder, Martial Ahipeaud, Guillaume Soro, and Charles Blé Goudé, were considered by Amnesty International to be "prisoners of conscience."[33]

By late 1997, continuing waves of student strikes, boycotts, and demonstrators resulted in the near-total paralysis of the Abidjan university campus, and made clear that FESCI could not be repressed out of existence. In September of that year, then President Henri Konan Bédié announced that, "The time has come to end a crisis that is seriously harming the whole nation," and pledged that more money would be invested in the overcrowded and dilapidated university system.[34] One week later, the ban on FESCI was lifted.

Internal Schism in the Late 1990s

Once able to function openly, and in tandem with a larger opening of the political landscape in Côte d'Ivoire as a whole, fissures along political lines began to form within FESCI's leadership. In 1998, FESCI held its first public elections, pitting outgoing Secretary General Guillaume Soro's candidate and number two in the organization's hierarchy, Karamoko Yayoro, now president of the youth wing of RDR opposition party, against Charles Blé Goudé, now head of the Young Patriots pro-government group. Some saw in these elections a fight for control of FESCI by two political parties, the RDR and the FPI.[35] Blé Goudé won those elections, and the organization has been widely viewed as being exclusively allied with the FPI party ever since.[36]

The late-1997 truce with the government was short lived. Accusing Bédié of failure to fulfill his promises for increased student aid, FESCI in 1999 led violent protests in favor of increased scholarship aid to students. During these protests, students engaged in widespread vandalism, including smashing cars and looting shops and businesses, leading to hundreds of arrests; the closing of many state-run educational institutions across the nation; the closing of university dormitories; and a "white year" for students in most disciplines (a year without exams, forcing students to repeat the school year). President Bédié and his cabinet denounced a "movement of destabilization, of a quasi-insurrectional nature" stirred up by FESCI and "its local and external manipulators," and threatened to arrest FESCI leaders, most of whom went into hiding.[37]

In response, police in May 1999 stormed the university residences as part of a brutal crackdown, leaving a trail of blood and damage as they pursued students, beating and kicking many. Several students were rushed to a nearby hospital with fractured limbs and head injuries.[38] In August, Blé Goudé was arrested, charged with disturbing public order, and placed in Abidjan's maximum-security prison, only to be rushed to the hospital in late-September with respiratory problems.[39] In October, tensions decreased when Bédié signed a decree granting amnesty to students convicted or detained for acts of violence during the year's protests and freed Blé Goudé. By the time FESCI finally lifted its strike in late November 1999, it had been a violent and tumultuous year, but the year's biggest event had yet to occur.

The Crisis Erupts, the University Shaken, 1999-2002

In December 1999, nearly 40 years of PDCI rule came to an abrupt end when the former head of Côte d'Ivoire's army, General Gueï, assumed leadership of a successful coup to oust President Bédié. The "Republican Front," an alliance of convenience created in April 1995 between opposition parties, dissolved. Mirroring national politics, the divisions that began within FESCI in 1998 soon intensified in the new political climate, and the organization began to fracture along political lines. At the same time, political parties battling for leverage in an electoral year sought to curry favor with FESCI, in part due to the coveted control of the street they could offer as well as the sheer number of youth votes they could mobilize.[40]

In May 2000, what would become known as the "dissident wing" of FESCI, led by Doumbia Major, second in command in FESCI's hierarchy and a supporter of the RDR party, accused Blé Goudé of mismanaging funds and attempted to challenge Blé Goudé's leadership of the organization. In response, Blé Goudé accused Major and his followers of trying to take FESCI over on behalf of the RDR, claimed that Alassane Ouattara was financing the "dissidents," and warned that the RDR would try to use FESCI to help win presidential elections later that year.[41] Members of Gueï's government similarly charged that the dissidents were being manipulated by the RDR.[42]

This marked the beginning of an open and often bloody struggle for control of FESCI (often called the "war of machetes") between a "loyalist" faction led by Charles Blé Goudé (who generally supported the military junta and the FPI) and a "dissident" faction led by Major (many of whom were pro-RDR). In a loose way, the divisions within FESCI during the "war" took on the regional and ethnic character that has come to characterize the Ivorian crisis up through the preset day, with the FPI drawing its supporters from the largely Christian south and the RDR from the largely Muslim north.[43]

During the "war," loyalist and dissident FESCI factions among the student population hunted each other down with machetes and clubs resulting in at least six deaths and dozens of serious injuries, including students thrown out of windows, hacked and nearly beaten to death with machetes.[44]For members of both factions, as well as for non-aligned students, this period is remembered as a "reign of terror" on campus.[45]

Publicly, Gueï called on students to "leave politics at home" and even threatened those responsible for student violence with military conscription. The army and other security forces intervened several times in clashes between students, often arresting those involved in the fighting.However, according to former dissidents interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the arrests were often selective, targeting dissidents in particular, and the loyalists who were arrested were often released almost immediately afterwards.[46] A few dissident members who were arrested told Human Rights Watch that while in custody, they were beaten by soldiers and accused of taking money and weapons from Alassane Ouattara.[47]

Violence erupted on a national scale during the October presidential and December parliamentary elections in 2000, leading to the deaths of over 200 people. State security forces gunned down mostly pro-RDR demonstrators in Abidjan's streets; hundreds of opposition members, many of them northerners and RDR supporters targeted on the basis of ethnicity and religion, were arbitrarily arrested, detained, and tortured, and state security forces committed rape and other human rights violations in complicity with pro-FPI youth groups, including FESCI.[48] Two victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch in the wake of the elections described being beaten by members of FESCI working in collaboration with gendarmes, who themselves participated in the beatings.[49]

After the electoral violence of late 2000 subsided, the two student factions organized rival congresses to elect a new secretary general in early 2001. Foreshadowing the formal division of the country less than 18 months later,the loyalists elected Jean-Yves Dibopieu in Abidjan, while the dissidents elected Paul Gueï, in central city of Bouaké, which became the fief of the dissidence.[50]The "war" resumed and the Abidjan and Bouaké campuses were plagued with violence similar to the previous year.[51]

In May 2001, under pressure from government and civil society groups, the representatives from the two FESCI factions met in the Abidjan suburb of Bingerville for talks. Under the "Bingerville Accords" signed by the two factions, the year-long "war of machetes" came to an end, Jean-Yves Dibopieu became secretary general, and dissident leader Paul Gueï his deputy.[52]

By this time, however, many leading dissidents had already either fled Abidjan or been forced into exile in neighboring countries such as Mali in order to escape the violence. Some former dissidents had defected to the loyalist side, while others attempted to fade from political and union life and continue their studies in relative peace and anonymity.

Unable to function in or accept an FPI-led Côte d'Ivoire, a large number of former FESCI dissidents went on to join the New Forces rebellion, which led an attempted coup d'état in September 2002, and currently controls the northern half of Côte d'Ivoire.[53] The rebellion is headed by former FESCI president Guillaume Soro. Today, many members of the New Forces administration are former FESCI dissidents. In the eyes of many FESCI loyalists, the rebellion was but a continuation of the dissident insurgency they thought they had vanquished on the university campus some 18 months prior.[54]

FESCI and the Rise of Pro-Government Youth Groups and Militias

The outbreak of civil war in September 2002 helped spawn a number of pro-government youth groups and armed militias, both urban and rural. The leaders of many of these new organizations cut their political teeth in FESCI, and several of them continue to maintain a loyal following within FESCI's membership today.[55] Together, these groups are often referred to in national discourse as "the patriotic galaxy."[56]

At the center of the "patriotic galaxy" is former FESCI leader Charles Blé Goudé, pictured below, and his Young Patriots pro-government youth group.[57] Blé Goudé played a crucial role in mobilizing the "young patriots" in Abidjan during and after the war, organizing pro-government demonstrations in 2003-2006 that paralyzed Abidjan for days at a time, often under the complacent and perhaps complicit eye of government security forces. As described in more detail below, the lines between pro-government groups like FESCI and those headed by its former leaders, such as Blé Goudé's Young Patriots, are often blurred both because individuals are often members of more than one group, as well as the fact that "patriotic" demonstrations and other activities involving these groups often draw members from a variety of organizations within the "patriotic galaxy."[58]

At the height of the crisis, members of the "patriotic galaxy" often congregated around "agoras" or street parliaments, where hundreds of individuals assembled to listen to orators who rallied the crowd with ultranationalist, anti-colonialist, and pro-FPI rhetoric.[59] Diatribes were directed at the perceived enemies of the FPI-led government, which, over the course of the Ivorian crisis, have alternated between the rebels, political opposition parties such as the RDR, the French, and the United Nations.[60] Many of the "patriotic" speakers who have animated the agoras are or have been members of FESCI.

Former FESCI leader, and current head of the Young Patriots pro-government youth group, Charles Ble Goudé, leads a demonstration wearing a red ribbon reading "Licorne out," March 18, 2005 in Abidjan, demanding the departure of French troops from its former colony. Similar speeches were frequently made in the years following the outbreak of war in public fora known as "agoras" or street parliaments. © 2005 AFP

Though they are not formally part of the state-security apparatus, especially in the years immediately following the war, members of these groups played an active role in matters of national security, including manning checkpoints on main roads in government-controlled areas, checking civilian identification, and generally taking on tasks usually carried out by uniformed government security forces.[61] These groups have also been used by government officials to violently suppress opposition demonstrations, stifle the press and anti-government dissent, foment violent anti-foreigner sentiment, and attack rebel-held villages in the western cocoa- and coffee-producing areas.[62] In almost all cases, crimes perpetrated by these groups benefit from total impunity.

Since signature of the Ouagadougou peace agreement in March 2007, political tensions throughout Côte d'Ivoire have ebbed, leading pro-government groups such as the Young Patriots to tone down their once vitriolic rhetoric and cease public protest. However, should political tensions rise once again, particularly in the lead-up to presidential elections, many political observers fear that these groups will immediately resume the activities for which they became notorious.[63]

In contrast to the armed militia groups operating primarily in western Côte d'Ivoire, pro-government youth groups tend to be less overtly militarized in their equipment and dress. While some members do possess arms, they do not typically carry them openly or patrol with them. Because they are not formally armed, they will not benefit from Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) programs. They have in common with the armed militias, however, a strong devotion to President Gbagbo and his ruling FPI party and a shared sense that they have risen up to defend the institutions of the republic against the rebellion's armed assault.

FESCI's Structure and Organizational Culture

FESCI is a rigidly hierarchical organization consisting of a national bureau, below which sit a number of "sections" of equal rank.[64] Sections are formed either by colleges within the university (i.e. criminology, modern letters, law), university residential complexes known as cités, or high schools. The national bureau is headed by a national secretary general, chosen by FESCI's membership during elections, who in turn appoints all of the secretary generals of the various sections.[65] At the base, rank-and-file members who are not part of the bureau of any section are known as "antichambrists" or "ATC."[66] Described by FESCI members interviewed as "foot soldiers," these are the members sent out as part of mass mobilizations for protest in favor of the government, or to do the "dirty work" described below.[67]

Beyond the strict hierarchy, status within FESCI is often influenced by a number of informal factors. Within FESCI, there is a system of patronage whereby nearly everyone acts as protector to someone, and in turn is protected by someone else. Subordinate members who are under the political cover of a superior are referred to as a "bon petit."[68] Being the "bon petit" of a high-ranking leader is often a ticket to a leadership position within the organization, together with the power, prominence, and often wealth, derived from the FESCI-run extortion and protection rackets that go with it. At the same time, leaders seek to maximize the number of members under their protection to extend their influence.

Outside of FESCI's formal structure sit former influential members known as the "doyens" or "observers," some of whom continue to live in the university residences for years after graduation.[69] One doyen in particular, known as "KB," short for Kacou Brou, is referred to by former FESCI members interviewed by Human Rights Watch as FESCI's "military leader" and "the power behind the throne" of FESCI's top leadership. KB is also described by former FESCI members as one of the key liaisons between FESCI's leadership and the FPI party.[70] KB is a graduate of the prestigious NationalSchool for Administration (École Nationale d'Administration, ENA), a state institution intended to produce high-level civil servants.

Divisions within the ruling FPI party are mirrored by divisions and power struggles within FESCI. According to FESCI members interviewed by Human Rights Watch, there are two primary factions within the FPI, the first influenced by Pascal Affi N'Guessan, secretary general of the party, to which "KB" and FESCI's most recent secretaries general have been loyal. A second faction is allegedly loyal to First Lady Simone Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé. Late-2006 internecine violence within FESCI has been attributed to an attempt by those in the Blé Goudé camp to take control of FESCI, though Blé Goudé denied the allegations.[71]

In addition to intra-FPI politics, power struggles within FESCI are often motivated by the economic spoils that often come with office. Due to extortion and protection rackets that FESCI runs (described in more detail below), being secretary general of a section can be highly lucrative and therefore highly prized. As a result, internecine violence, putsches, and putsch attempts are common.[72] Intra-FESCI violence during elections for the national bureau, including machete battles between rival factions, is routine.[73]

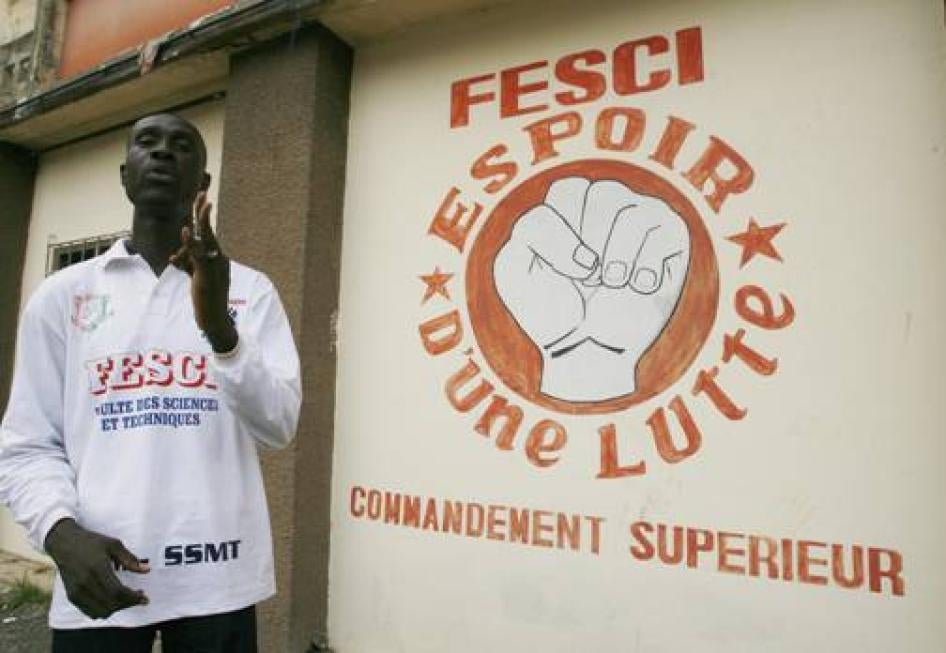

Since the outbreak of the crisis, but likely before, there has been an increasing militarization of FESCI's organizational culture. Secretaries general, both at the level of the national bureau as well as individual sections, are greeted by FESCI members (and even some non-FESCI members living in student dormitories) with a military-style salute, and the statement "Yes, General, I am at attention!"[74] Members are often known only by their noms de guerre, examples of which include "Che," "Foday Sankoh," and "Kabila." At the entrance to FESCI's de facto headquarters, one of the university residences known as the "Cité Rouge," FESCI's emblem, a raised fist, is painted in red above the words "high command."

Augustin Mian, elected as the new secretary general of FESCI in uncontested December 2007 elections, stands outside the Cité Rouge in the Abidjan suburb of Cocody. © 2007 AFP

Why Students Join FESCI Today

Students interviewed by Human Rights Watch cite a range of reasons for membership in FESCI. Most frequently, former members cite economic incentives, including the access to free university housing, free food, and free transportation that membership in FESCI often assures, essential commodities for survival that other students must struggle to obtain.[75] In an already impoverished society ravaged by conflict, and where a university diploma no longer guarantees privileged economic livelihood or a job in the civil service, one professor noted that:

When I studied at this university decades ago, there was work, so you wanted to finish school as soon as possible to get a paying job. But today, there are no jobs so there is no hurry to finish. In fact, students can make more money by staying here. Or they can make money here for a while and then possibly think about a job in the future. If there was economic hope for youth, it would weaken FESCI.[76]

In addition to economic incentives, other former FESCI members cited the respect and power accorded to members: "When I joined in 1998, FESCI was a way to express myself. Coming from a poor family of farmers, this gave me a way to organize, be respected, and try to solve problems."[77] As has been said in the context of another pro-government group, the Young Patriots, for many students FESCI constitutes a sort of "counter-society where students flunking out can be called 'professor,' and unemployed youth, thugs even, become 'deputy' or 'general,' and will be recognized as such by their peers."[78]

A few students interviewed by Human Rights Watch stated frankly that they joined FESCI because they saw it as a springboard to politics: "I joined FESCI because it suited my political ambitions. They say that unions are the antechamber of politics. And my time in FESCI ripened me politically, but I came to deplore the barbarity and violence that has come to be a part of FESCI."[79]

FESCI Activities and Violence Perpetrated Since 2002

After the eruption of armed rebellion in September 2002, the changes that had begun within FESCI during the "war of machetes" accelerated, to the point where members of FESCI from the early 1990s told Human Rights Watch they scarcely recognize the organization they created.[80] Rather than student strikes for student causes, FESCI is often known today for both politically and criminally motivated violence meted out primarily against fellow students perceived to support opposition political parties or the northern-based rebels, actions taken to stymie the peace process at key junctures on behalf of the ruling FPI party, and the impunity which nearly always attaches to FESCI-perpetrated crimes. In addition, members of FESCI are routinely associated with "mafia" type behavior including extortion and protection rackets. Together, FESCI's actions both on and off campus have a chilling effect on the freedoms of expression and association for fellow students and professors.

Activities and Violence on Campus

Murder, Assault, and Torture of Fellow Students

Since 2002, members of FESCI have on numerous occasions attacked fellow students, especially those of northern origin or who are considered to bear some other proxy for imagined rebel sympathy or support for the political opposition. Many of the most brutal attacks were perpetrated against members of a rival student union. During these attacks, at least one student has been murdered, and others have been severely beaten and tortured in student dormitories.

Many of the incidents investigated by Human Rights Watch have been highly publicized in local media, made the subject of press conferences by local human rights groups, featured in the reports of the United Nations Mission in Côte d'Ivoire (ONUCI), and denounced by international human rights groups.[81] In several instances, victims have filed complaints with the police, but in very few instances has a member of FESCI been arrested for criminal offenses perpetrated against fellow students. Student leaders told Human Rights Watch that in most instances when they have reported violence to the police, they have been told that, "since FESCI is involved, you better settle it amongst yourselves."[82] In a few instances, some of which are described below, police themselves were actual eyewitnesses to FESCI-perpetrated crimes, and yet nevertheless failed to intervene or otherwise respond professionally.

The most severe abuse by far has been experienced by members of a rival student union, the General Student Association of Côte d'Ivoire (Association Générale des Élèves et Étudiants de Côte d'Ivoire, AGEECI), which FESCI has accused of supporting the New Forces rebels.[83] Since its creation in 2004, one of AGEECI's leaders has been assassinated, one of its female members gang raped, and a number of its members badly beaten by students claiming membership in FESCI. While FESCI-perpetrated violence against AGEECI members has diminished in recent years, AGEECI members told Human Rights Watch that the relative calm is primarily due to the fact they have stopped or curtailed nearly all public activities. Today, many AGEECI members fear to set foot on campus.[84]

One of the most notorious FESCI-led attacks involved the killing of one of AGEECI's founding members, Habib Dodo, also a leader in the youth wing of the Communist Party. According to eyewitnesses, on June 23, 2004, Habib Dodo was kidnapped from the home of Ekissi Achy, the secretary general of the Revolutionary Communist Party of Côte d'Ivoire (PCRCI). According to witnesses, around , one student in the house received a phone call warning him that a large group of students was making its way to the house, just minutes before they arrived.[85] One witness present in the house that day described FESCI's arrival:

There were about forty of them that surged into the house. I recognized between a third and a half of them as FESCI members. Some had t-shirts that said "FESCI Criminology," because that's the section they were in. They were armed with sticks shouting, "Where is he? Where is he hiding?" [referring to Habib Dodo] They busted up stuff around the house, including the television, windows, the bathroom sink, everything. They also stole clothing, shoes, and money. When I ran to my room to make sure they hadn't stolen my scholarship money, I saw three of them in there looking through things. They were ATC [Anti-Chambristes], the foot soldiers of FESCI.[86] They are the ones who are gathered up for these sorts of actions. There was screaming and crashing all over the house. I decided to run with a friend to the police station, the 16th precinct. When I got there, I was so panicked that it was hard for me to explain. It took about five minutes to calm down. Finally, I said, "FESCI is attacking our house!" But they told me they didn't have anyone available to send.[87]

Meanwhile, another witness present in the house during the attack, the secretary general of the PCRCI, also attempted to contact the police:

After FESCI left with Habib I called the police, but no one came. Finally, I took a taxi there. It was about one kilometer away. When I arrived, I told them, "We've been calling and calling!" But the officer just asked me to leave. I said, "I'm talking about a kidnapping. They will kill him!" But I realized that he wasn't going to do anything, so I took another taxi to the prefecture de police in Plateau.[88] I saw the second in command who called the director who said he'd look into it. Only then did someone from the 16th precinct come to my house to survey the damages. The next day I was told they had killed Habib on campus by hanging him.

The same day Habib was kidnapped, another communist student, Richard Kouadio, was almost beaten to death in Bassam.[89] He was left near the Bassam road. We rescued him after I received an anonymous call saying that FESCI had taken him. ONUCI went and got him and took him to the main hospital in Treichville.[90]

In a July 2005 interview, FESCI leader Serge Koffi justified the attacks on AGEECI because "AGEECI is not a student organization and we cannot let them meet on campus. It is a rebel organization created in the rebel zone and seeking to spread its tentacles to the university."[91]

The secretary general of the PCRCI described efforts to seek justice in the Habib Dodo case:

I immediately filed a complaint with the police against FESCI and its leaders for kidnapping, torture, murder, and vandalism. We initially hired a lawyer who dropped the case as soon as he understood the sensitive nature of the affair, but MIDH helped us.[92] Since that time, we've tried to bring both political and legal pressure to move the case forward. We went to see the Minister of Security at the time, Martin Bléo, and he had the police guard my house for one year. He supposedly gave instructions to have the case followed. Then we went to see Henriette Diabaté, the Minister of Justice at the time, and we gave her a copy of the complaint. We also saw the Minister of Human Rights at the time, Madame Wodié. We've even given names of the people involved to the judicial police. The police have interviewed Richard Kouadio and members of AGEECI, but we've never heard of any FESCI members being questioned. Over three years later, we have finally been told that the file was sent from the police to a magistrate. In the end, we don't think it will go anywhere because of the politics involved, but we have to keep trying.[93]

FESCI-perpetrated violence against members of AGEECI peaked in 2005, when a number of AGEECI members were severely beaten. One victim described being beaten in July 2005 after trying to distribute pamphlets at a bus station inviting students to an AGEECI press conference:

We were at the north station in Adjamé when a busload of FESCI members came, as many as a hundred of them.[94] They grabbed two of us distributing pamphlets, but three got away. It all happened right in the middle of the bus station with people all around. They stripped us naked right there in front of everyone. There were police I saw at the bus station watching. One policeman told FESCI, "Leave them alone." But a FESCI member replied, "That won't happen. This is FESCI and these are rebels!" After that, the policeman watching-there were either two or three of them-did nothing. Someone in the crowd yelled, "If they are rebels, kill them!" At that point, they put us in a taxi to take us to the Cité Rouge in Cocody.[95] In the taxi, they were sitting on top of us like we were the seats. There were three of them on top of us, and two in the front of the taxi. My companion passed out. In the taxi they were saying, "We're going to kill them." When we arrived at the Cité Rouge, they took us behind the cité and beat us. Then Maréchal KB came with his security personnel. He asked questions like, "Did you take money from the rebels?" and "Who do you work for?" Then he said, "We're going to kill you if you don't admit you took money from the rebels." Meanwhile, our comrades had called ONUCI, LIDHO, MIDH, and someone contacted the Minister of Security, Martin Bléo, who applied pressure and we were freed around [96] A week later, we filed a complaint at the palais de justice in Abidjan, but it hasn't gone anywhere. The authorities have questioned no one and done nothing. But ONUCI photographed us and gave medical treatment, and MIDH did a press conference.[97]

Several instances of FESCI-perpetrated violence against members of AGEECI involved the manifest failure of police to intervene or respond in a responsible way, as illustrated by the following testimony of a FESCI attack in December 2005:

I was working with high school students at their school to create an AGEECI committee. Around that afternoon, a number of cars pulled up outside the school. There were five of us AGEECI members in the classroom at the time. Three went to see what the commotion was, and never came back. The next thing I knew, a group of FESCI members erupted into the classroom. They started to hit the two of us who were left with clubs and the blunt side of machetes. Then they put us in a taxi. Before we drove off, four policemen arrived in a truck. We thought they would intervene to save us, but FESCI told the police that we were rebels and assailants. The police said that if that's the case, they should go ahead and kill us. The police left, and we drove off.

As we were driving near the port, we were stopped at a checkpoint by two policemen. The people in the car identified themselves as FESCI members and then got out to talk with the police. They got back in the car and we drove through the checkpoint. We started driving towards an abandoned area. I was afraid that if that was where they were taking us, it meant death, but then they took us instead to the Cité in Port-Bouet.[98] They first took us to a building and put me in a small room, where a group of them started to beat me with clubs and slingshots. Then I passed out. When I woke up, they started asking whether I worked for the rebellion, for Ouattara, or for Soro. Then they said they were taking us to the beach to kill us by drowning. The beach wasn't far and they marched us there, which started to attract attention. They threw us in the water. A lifeguard came and FESCI started to threaten him. A crowd began to gather and people started asking questions. Eventually the crowd got big enough that the FESCI members left. The lifeguard called an ambulance and they took us to the hospital.

Since then, I've been threatened so many times on my cell phone that I had to change the number. I had to go outside of Abidjan for a while to protect myself. If I try to file a complaint against a FESCI member, it won't go anywhere. They're the ones who brought the president to power. They can do what they want.[99]

While members of AGEECI have suffering the most severe FESCI-perpetrated violence, other students and student groups interviewed by Human Rights Watch report that they have suffered occasional beatings by members of FESCI, particularly where there was a challenge to FESCI's economic activities on campus.[100] A university student told Human Rights Watch:

In November 2006, around eighty of us in a class gave 2,500 francs each [West African CFA francs, about US$5] to the delegate of our class section to make copies of a document we needed for our economics exams. When he didn't deliver the copies as promised, we weren't sure when or if we were going to see them. So we drew up a petition to national bureau FESCI to protest, but before we sent it, six of us went to see the head of all class section delegates, who is a member of FESCI. He told us to meet him at amphitheatre H3 to discuss the matter. When we arrived on their third floor, there were lots of FESCI students on the stairs, and then twenty or so in the room, all waiting there. We knew them as FESCI because we all know each other and they don't try to hide their membership. They put five of us on our knees, but they separated out the deputy delegate of our class section into another room. They had some irons plugged in and said they were going to iron us with them. The also had belts and clubs. Then they started to beat us one at a time. If you would get up, they would hit you again. One of us started to bleed a lot and they told him to clean up the blood. They were saying, "You want to spoil our gumbo?[101] You want to spoil our business?" Meanwhile, the deputy delegate was in a room next door getting beaten even more severely. His eyes were swollen shut and they made him wash his face with hot pepper water. Later, there was a meeting held between the university administration and those who were beaten. They told us they would listen to FESCI and then do a mediation and reconciliation, but they never called us after that. We didn't file a complaint with the police because if you do that you better have a bodyguard. They could even kill you. You'd have to flee the country. Maybe you could file a complaint against another movement, but not them.[102]

Sexual Threats and Violence

Human Rights Watch documented several cases of sexual abuse and exploitation perpetrated by members of FESCI since 2002, and believes the numbers and incidence of sexual abuse by its members may be significantly underreported.[103]

Students interviewed by Human Rights Watch report that FESCI members demand and extort sex from female students on campus, occasionally by threatening to kick a student out of her dorm room unless she agrees to sleep with a FESCI member.[104] A journalist quoted a law student as stating, "As soon as a girl pleases [a member of FESCI] they send their guys to get her. If she refuses to submit to them she is expelled from the residence and prevented from going on campus to attend her classes."[105]

When a group of women interviewed by Human Rights Watch was asked how one could contact the school administration for protection or how to report such behavior, the interviewees all laughed and one said, "You are dreaming! The university will do nothing."[106]

Human Rights Watch research indicates that members of FESCI have been implicated in at least two cases of rape. The most notorious case involved the brutal gang rape of an AGEECI student leader in June 2005 on the Cocody Campus in Abidjan, explicitly because of her student activism with AGEECI. She told Human Rights Watch:

I was kidnapped by the same members of this FESCI which had tortured Habib Dodo to death. After dragging me all over the campus, looking for a "general" who was supposed to tell them what to do, they finally went to the old campus. Shortly afterwards, they made me undergo an interrogation. Their questions were trying to make me confess AGEECI's collaboration with the rebels, and to get information about the leaders. I tried to say I didn't know anything…They told me I was screwed. They also gave me information on my home, my private life, to show me that they know a lot about my case and that I couldn't escape them. When they spoke of my [family members]…I had chills…Then my interrogator asked them to "Be effective" as he locked me up with four of them, and told them to "Do a clean job…" They beat me up. They told me that they were trained to kill and that they'd kill me if I didn't speak. They showed me bloodstains on the ground… and told me it was the blood of my comrades who'd been tortured there not long ago. Then…one of them insisted that they undress me forcibly and make me lay down, which was done. I understood right away that this was to accomplish an evil plan. One of them hit my head against a wall, the others were hitting me and sexually abusing me. I screamed until my voice was hoarse but it was useless…My rapist took his place, squeezing my throat with his two hands. He was strangling me…He covered my face with a piece of coarse cloth and penetrated me. While he was raping me I tried to fight back and scream but the others were holding my feet… My rapist was hurting me. I was disgusted, suffering, and powerless…[After they let me go] they forbade me to return to the campus and told me my studies were finished…on pain of death.[107]

A leading local human rights NGO following this woman's case confirmed that there has been no police investigation of the complaint she registered and that her requests for action from the university and Ministry of Justice have received no response.[108] The same organization documented the gang rape of another student active in the PDCI opposition party by two members of FESCI (one of whom she could identify) near her house in Abidjan shortly after she participated in an anti-government protest march on March 25, 2004. This student gave the organization a written, detailed testimony, reviewed by Human Rights Watch. The NGO confirmed that there was no police or judicial follow-up for her case.[109]

Intimidation and Attacks on Professors and Teachers

Since at least 2002, FESCI has subjected to intimidation, and occasionally physical abused, of several professors and teachers because of their political beliefs or activism for better working conditions. In November 2007, FESCI members reportedly beat with belts and clubs two high school teachers who participated in a teachers strike.[110]

A high school teacher told Human Rights Watch that in November 2006 FESCI students smashed a rock over his head during a fight that started in a restaurant after students had become drunk.[111] According to the teacher, though his fellow teachers went on strike in protest, the students involved were not sanctioned.

Other teachers told Human Rights Watch that they fear giving a bad grade to a member of FESCI due to unpredictable and possibly violent consequences:

At our high school, we have about 4,000 students. All teachers know who the members of FESCI are because if you have a FESCI leader in your class, he can come and go when he wants and speak when he wants. If you don't let the student do what he wants, you'll be eyed suspiciously and you might end up getting attacked in the street. You'll never even know who did it because chances are they will send people you don't know. So the teachers are afraid of them because it's a question of your life. You fear to give them a bad grade.[112]

While many teachers, especially at the high school level, continue to fear FESCI-perpetrated violence, the head of a professors union at the university explained to Human Rights Watch how the presence of former FESCI members among the university professors is beginning to change professor-student relations:

Last year [2006], FESCI disrupted our general assembly held while we were on strike. Some FESCI students came with machetes. We told them that if they so much as touched a professor there would be two "white years."[113] Today relations with FESCI have changed a bit because . . . newer professors used to be FESCI members themselves and they have become more strident in defending our interests. They know how FESCI operates and they won't let us be intimidated.[114]

Effect on Freedoms of Speech and Association

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, professors, teachers, and students described the chilling effect that FESCI's actions have had on freedoms of expression and association at both the high school and university level.

Teachers at the high school level described being reluctant to discuss the performance of the current government, to suggest that the economy is doing poorly, or to address a number of other politically sensitive subjects in the classroom:

We're obliged to limit what we say in class for fear of the consequences. For example, you can't criticize the management of the country and you have to say in spite of your convictions to the contrary that things are getting better. You can't talk about corruption. You can't denounce human rights abuses. And if you give a bad grade, they can intimidate you until you change it. But FESCI is a false problem. It is here simply because it is supported by a political system. It's kept like a sword of Damocles over the heads of anyone thinking of opposing power.[115]

University professors interviewed by Human Rights Watch appeared less fearful to address politically sensitive topics in class, but all noted that criticizing FESCI or the political controversy surrounding its actions is off limits:

Regarding freedom of expression, we professors pay attention to all we say and do as concerns FESCI. They have the benefit of impunity. The politicians, police, and army won't help you if you are threatened by FESCI. FESCI can murder and the investigation will never go anywhere. But the politicians prefer to close their eyes to certain practices because ultimately they need FESCI for their political ends.[116]

The shadow cast by FESCI's history of violence has had a profound effect on the activities of other student organizations, from rival student unions to student religious groups, who told Human Rights Watch that after the abuses perpetrated against AGEECI,[117] they have curtailed or ceased open recruitment, passing out pamphlets, and other activities that could be construed as a challenge to FESCI's dominance on campus.[118] Thus, in many ways, attempts to exclude perceived rivals from political space through violence and intimidation, so prevalent on the national stage since the crisis erupted, have been mirrored at the university level, and have served to greatly undermine freedoms of association and expression on campus.

Beyond refraining from public acts on behalf of a rival organization, opposition supporters living in student dormitories told Human Rights Watch that they must be discreet about their political affiliation, even going so far as to making sure they do not have any books or literature in their rooms that might associate them with the opposition, to avoid being forcibly evicted by FESCI from their room: "In the dorms, if you are not pro-FPI, you can't express yourself. What you think, it has to be kept inside you, not expressed. That's one of the worst things about it. You have to hide who you are for your own security and survival."[119]