Crossing the Line

Georgia's Violent Dispersal of Protestors and Raid on Imedi Television

Summary

Georgia under President Mikheil Saakashvili has been hailed by Western governments as an example of a successful transition to democracy in the former Soviet Union. However, the fragility of Georgia's commitment to human rights and the rule of law was revealed on November 7, 2007, when government forces used violent and excessive force to disperse a series of largely peaceful demonstrations in the capital, Tbilisi. In the course of breaking up the demonstrations law enforcement officers hastily resorted to the use of teargas and rubber bullets. Police and other law enforcement personnel, many of them masked, pursued fleeing demonstrators of all ages, kicking and punching them and striking them with truncheons, wooden poles, and other objects. Heavily armed special troops raided the private television station Imedi, threatening and ejecting the staff and damaging or destroying much of the station's equipment. Outside the studios, Imedi staff and their supporters found themselves set upon by riot police again using teargas and rubber bullets and pursuing those who fled. Extensive photographic and video evidence captured that day by journalists and others illustrates these incidents.

The violence capped several days of peaceful demonstrations by Georgia's opposition parties and supporters, who were calling for parliamentary elections to be held in early 2008 and for the release of individuals whom they consider political prisoners, among other demands. It contrasted sharply with the reputation the Georgian government-brought to power by the 2003 Rose Revolution-had cultivated for being committed to human rights and the rule of law.

The Georgian government denies the widespread use of violence against demonstrators. It maintains that law enforcement officers used legitimate means to disperse protestors who were holding illegal demonstrations, and accuses demonstrators of initiating violence against police. The government also claims that opposition leaders intended to use protestors to storm Parliament as part of an alleged Russian-backed coup attempt, in which Imedi television was playing an instrumental role.

The situation on November 7 was extremely tense, and the Georgian government faced an enormous challenge in retaining law and order.Many demonstrators refused to follow initial police orders to disperse, and there were instances of protestors attacking individual police officers, particularly later in the day.It is the right and duty of any government to stop such attacks. However in doing so, governments are obligated to respect basic human rights standards governing the use of force in police operations. These universal standards are embodied in the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials,[1] which state, [w]henever the lawful use of force is unavoidable, law enforcement officials shall exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offense.[2]In accordance with its obligations as a party to the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the government of Georgia is responsible for the injuries caused by law enforcement officials to demonstrators and bystanders and has the burden to demonstrate with convincing arguments that the use of force was not excessive.

The circumstances described in this report do not justify the level of violence used against demonstrators documented here, particularly given that many of those beaten were peaceful protestors, protestors attempting to disperse, or individuals merely observing the events or coming to the aid of victims of police violence.

The physical assaults on these individuals by Georgian law enforcement officers were not a legitimate method of crowd dispersal and resulted in a large number of serious human rights violations, all of which must be thoroughly investigated. Georgian law enforcement officers resorted too quickly to the use of force, including simultaneous use of canisters of teargas and rubber bullets, without fully exhausting non-violent methods of crowd dispersal. There was no apparent measured or proportionate escalation of the use of force either to disperse demonstrators or to respond to sporadic violence.

The raid on and closure of Imedi television was a violation of Georgia's commitments to guaranteeing freedom of expression. The legal basis for the decision to raid and close Imedi has been seriously called into question, and there is evidence to suggest that the legal basis was established after-the-fact and backdated. The government's allegation that a single broadcast by Imedi posed an urgent threat to public security is also questionable and deserves further scrutiny. In any case, the raid on Imedi using hundreds of heavily-armed law enforcement officers, which was initiated without warning against hundreds of journalists and other staff, was clearly disproportionate to the threat posed by unarmed Imedi personnel and an act of intimidation unjustified by the actions of Imedi television or any of its staff, leadership, or ownership.

Sequence of Events

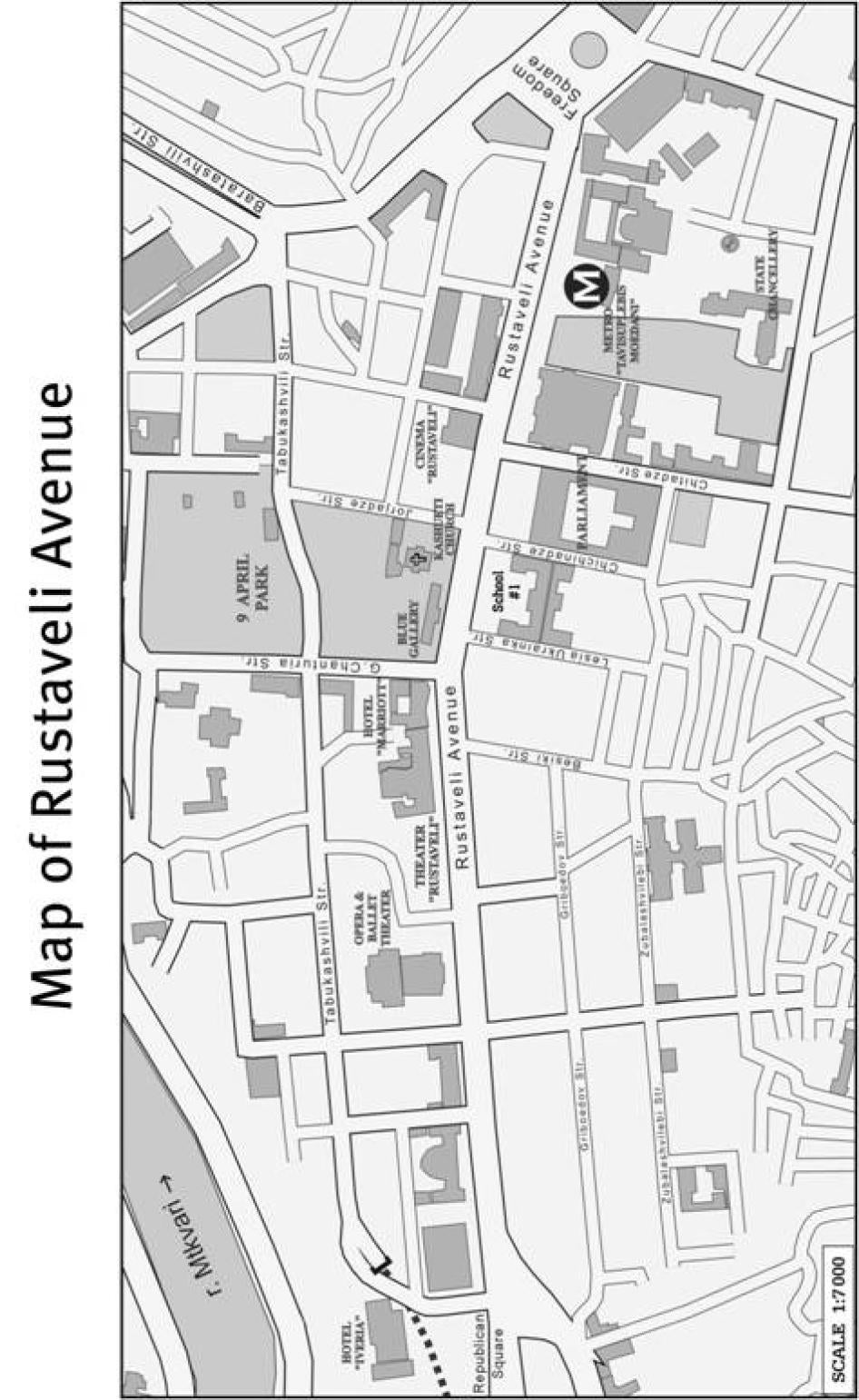

On November 2, a coalition of Georgian opposition parties led a demonstration on the steps of Parliament and on Rustaveli Avenue in the center of Tbilisi. Many were opposition supporters but many also came out to protest what they perceived to be government corruption and failures to deliver on promised political and economic reforms. Approximately 50,000 people participated on the first day. On subsequent days, the opposition continued to hold a demonstration in front of Parliament, with the number of supporters steadily decreasing. Several people had announced a hunger strike on November 4 and they, together with a few other supporters, spent each subsequent night on the steps of Parliament.

Human Rights Watch documented excessive use of police force at four demonstrations on November 7. Early that morning, police without warning charged the approximately 70 people who had spent the night on the steps of Parliament, pulling them off the steps and beating several of them. Also beaten were a few other demonstrators and supporters who tried to resist police attempts to remove the hunger strikers. Policemen also confiscated the cameras and equipment of several journalists and arrested Giorgi Khaindrava, an opposition leader and the former minister of conflict resolution.

Later that morning, when demonstrators gathered in front of Parliament, some tried unsuccessfully to push through a police cordon on Rustaveli Avenue. Eventually protestors became too numerous to fit on the steps and sidewalk in front of Parliament, and they forced their way through the police cordon and onto Rustaveli Avenue. There were some altercations between police and protestors and incidents of police force against protestors. Police arrested some demonstrators.

Riot police and other law enforcement officers assembled on Rustaveli Avenue, ordered the crowd to disperse, and warned that legal means of crowd dispersal would be used. When most demonstrators did not heed the request, riot police briefly sprayed the front lines of protestors with water cannons. Most demonstrators still did not disperse. Without subsequent warnings, law enforcement officers then launched a volley of teargas canisters into the crowd and opened fire with rubber bullets, causing demonstrators to flee immediately in the few directions available and into nearby buildings. Riot police and other law enforcement officials, many in black masks and all without any identification, pursued the dispersing protestors and attacked them with fists, kicks, truncheons, wooden poles, and other objects.

As demonstrators dispersed through the side streets leading away from Rustaveli Avenue, some of them joined a large number of additional demonstrators to gather at the other end of Rustaveli Avenue, from the direction of Republican Square. When this crowd did not disperse, law enforcement officials again used large volumes of teargas and rubber bullets against the crowd. A few demonstrators damaged a police car and others threw stones and active teargas canisters at riot police. Police beat individual fleeing demonstrators.

Seeing that the majority of demonstrators were unwilling to disperse, opposition leaders called on people to go to Rike, a large open area several kilometers from the city center with no through streets. Riot police and other law enforcement personnel essentially surrounded the protestors at Rike, fired teargas and rubber bullets at them, and again pursued and attacked individual demonstrators, many of whom were attempting to flee. At Rike there were several incidents of attacks by demonstrators on police, some of them quite violent.

At approximately 8:45 p.m., after all demonstrators at Rike had been dispersed, hundreds of special forces troops armed with machine guns and other weapons entered the Imedi television studios, and forced journalists and other staff members to lie on the floor with their hands behind their heads, deliberately intimidating them by pointing guns to their heads and with aggressive language. The government troops forced Imedi off the air, after anchors managed to describe the raid to viewers in the final minutes of broadcasting. Journalists and other staff were forced to leave the studios and troops damaged or destroyed much of the station's equipment. Imedi was founded by Badri Patarkatsishvili, an exiled Georgian businessman, and is partly owned by Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation.

After seeing Imedi forced off the air on live television, dozens of relatives and friends of Imedi staff members and Imedi supporters gathered outside of the Imedi studios. As Imedi staff, forced by police to leave the property, also gathered outside the studios' main gate, riot police and other law enforcement agents fired teargas and rubber bullets into the small crowd and pursued people as they fled, attacking them with truncheons and fists and firing rubber bullets. During the operations on Rustaveli Avenue and Rike, law enforcement agents had also targeted journalists, including both Imedi journalists and others.

Accountability for the Excessive Use of Force

The Georgian government has said it was facing the threat of a coup d'etat organized by opposition leaders with support from the Russian counter-intelligence service. The government claims to possess recordings of phone conversations and video recordings of opposition leaders meeting with members of Russian intelligence. The authorities also claim that Badri Patarkatsishvili, who openly provided financial support to opposition parties in Georgia, had called for the overthrow of the government.[3] The coup d'etat figures prominently in contemporary Georgian history, and Russia and Georgia have a tense political relationship. Most significantly, Georgia accuses Russia of seeking to undermine its territorial integrity through its open support of Georgia's two breakaway territories, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. While Human Rights Watch cannot assess the validity of the above claims, they have no bearing on the government's obligation to respect basic human rights and to ensure that law enforcement officials respond to protests in a lawful and proportionate manner. Similarly, the government's response to any perceived threat posed by Imedi television was clearly excessive and a violation of freedom of expression guaranteed under Georgian and international law.

Georgia's international partners, including, most prominently, the United States and the European Union, have provided unwavering support for President Mikheil Saakashvili and his government since the Rose Revolution brought it to power. Georgia has been seen as a small but crucial bulwark to counter Russian dominance in the region and as an important ally for the United States. It has also been held up as an example of a successful transition to democracy in the former Soviet Union region.As a result, the US and EU have refrained from criticizing Saakashvili in public and from engaging in robust discussion of the country's human rights problems. They have relied on the Georgian government's repeatedly-stated good intentions and promises of reform, ignoring warning signs that the government was not only failing to live up to the principles of the rule of law and human rights it espoused during the Rose Revolution, but taking many serious steps to undermine these principles. Among them has been the dangerous mix of a quick resort to use of force by law enforcement agents, the willingness at the highest levels of government to condone these actions, often publicly, and a failure to ensure accountability for abuses committed by law enforcement agents.

Human Rights Watch is calling on the Georgian government to conduct a thorough and independent investigation, in line with human rights standards, into the dispersal of protestors on November 7, 2007, including into all allegations of assault and the excessive use of force by law enforcement personnel. Human Rights Watch calls on the Ministry of Interior to make public the exact composition of forces engaged in the dispersal of protestors to ensure full transparency and accountability for the actions of law enforcement. The General Prosecutor's Office should conduct a thorough investigation into the allegations of intimidation and ill-treatment of Imedi journalists during the raid on Imedi and into the allegations of destruction and theft of Imedi equipment and property. Georgia's international partners should offer, where appropriate, expertise and assistance to the Georgian government in fulfilling these recommendations. They should also include as a principle benchmark for further assistance to and deepening engagement with Georgia the government's commitment to ensuring accountability for human rights abuses, including the abuses documented in this report.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews with 35 witnesses and victims of the events of November 7, 2007, in Tbilisi, Georgia, including the police dispersal of demonstrators on Rustaveli Avenue, the police dispersal of demonstrators at Rike, the raid on Imedi television, and the dispersal of people outside of the Imedi television studios. The interviews were conducted by a Human Rights Watch researcher and a consultant from November 12 to 16, 2007, in Tbilisi.

Human Rights Watch identified victims and witnesses of the events of November 7, 2007, with the assistance of the Office of the Ombudsman of Georgia and Georgian nongovernmental organizations. In addition, the Human Rights Watch consultant identified several victims and witnesses through his professional and personal contacts.

Most interviews were conducted in Russian, and some in English, by the researcher and consultant who are fluent in both Russian and English. A few interviews were conducted in Georgian, during which the Human Rights Watch consultant, a native speaker of Georgian, translated into English for the researcher. In a few instances the full names of interviewees have been disguised with first names and initials (which do not reflect real names) at their request and out of concerns for their security.

Human Rights Watch also met with representatives of the Ministry of the Interior and received written responses to questions submitted to the Office of the Prosecutor General of Georgia.

Background

In November 2003 a popular uprising following fraudulent parliamentary elections, which became known as the Rose Revolution, ended in the bloodless ouster of the government of President Eduard Shevardnadze. Mikheil Saakashvili, leader of the Rose Revolution, was elected president in January 2004 with 96 percent of the vote. He was enormously popular at home and in the West, but faced significant challenges. Conflict in the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia remained frozen, leaving some 220,000-247,000 people internally displaced in Georgia,[4] organized crime had laid waste to the economy, widespread corruption paralyzed state institutions, and unemployment and poor economic conditions drove a large portion of the population to seek employment abroad.

President Saakashvili launched a series of institutional reforms-most notably to overhaul the famously corrupt police and judiciary-and prioritized fighting organized crime. He successfully reasserted control over Adjara, a region of Georgia that had refused to cooperate with the central government.

Parliamentary elections in March 2004 gave Saakahsvili's ruling National Movement party an overwhelming majority in Parliament, and its decisive victory in October 2006 local elections further strengthened the president's mandate.

In December 2006 the Georgian Parliament amended the constitution to extend the term of the current Parliament and allow for simultaneous presidential and parliamentary elections at the end of 2008. Parliamentary elections were initially scheduled for April 2008, and a presidential election for early 2009.[5] In doing so, the government sought to de-link Georgia's election cycle from two external events that it said risked destabilizing the political environment: the March 2008 presidential election in Russia and the impending determination of a final status for Kosovo.[6] Opposition parties opposed the amendments, claiming that the schedule gave an unfair advantage to the National Movement party.[7]

Georgia's political opposition has been weak and fragmented. Some analysts have observed that Saakashvili alienated the opposition and others by constantly rebutting criticism and using his supporters' majority in Parliament to dominate politics and reject constructive dialogue and social consensus on reforms.[8]While it is beyond the scope of this report to enumerate all of the opposition's criticisms of Saakahsvili's government, it is worth noting that the resignation and then arrest of former Defense Minister Irakli Okruashvili, who had been one of Saakashvili's closest associates, served to galvanize it.[9] Okruashvili was arrested on September 27, 2007, two days after making public statements accusing Saakashvili of corruption and claiming that the latter had instructed him to kill Badri Patarkatsishvili, founder and part-owner of Imedi television.[10]

The Opposition Demonstrations

Shortly after Irakli Okruashvili's arrest, 10 opposition parties and movements established the United National Council to coordinate their activities. The council initially issued four main demands to the government, the most important of which was to restore parliamentary elections to their original scheduled date of April 2008. Other demands included the creation of new local election commissions with representatives from political parties; changing the current majoritarian electoral system; and the release of "political prisoners."[11] The opposition also accused Saakashvili of corruption and the use of the police and the judiciary for political purposes.[12]

The coalition organized a series of protest rallies in Georgia's regions, including in Kutaisi (October 19), Batumi (October 23), and Zugdidi (October 28). These protests drew between a few hundred and a few thousand peaceful demonstrators. The protest rally in Zugdidi, in western Georgia, turned violent after a group of unidentified men, believed to be security officials, attacked the protestors and severely injured two members of Parliament as they were leaving the demonstration site.[13]

The United National Council also planned for a large rally to be held in front of the Parliament building in the capital, Tbilisi, on November 2. This demonstration attracted over 50,000 protestors,[14] making it the largest public demonstration since the Rose Revolution. The demonstrations continued after November 2, although the number of participants rapidly decreased to only 3,000 to 4,000 during the day on November 6.[15]

While many demonstrators in Tbilisi and other cities joined the protests to express support for the political opposition's platform, many also participated to express frustrations about continued economic hardship. Despite strong economic growth in recent years and significant progress in structural reforms, the effects of an improved economic climate have been far less significant for ordinary people. Poverty remains widespread in Georgia, particularly outside of Tbilisi.[16] According to the International Monetary Fund, unemployment continues to increase and poverty remains at approximately 30 percent.[17] Furthermore, the public has increasingly low confidence in the judiciary.[18]

Until November 3, opposition leaders focused on their original four demands. However, feeling that the government had largely failed to respond to their concerns, opposition leaders' demands became increasingly strident, ultimately calling for President Saakashvili's resignation.[19]

Georgian Media and Imedi Television

Georgia has a vibrant media. There are four main national television stations, including the state-funded National Public Broadcaster, three private stations (Rustavi 2, Mze, and Imedi), as well as a few smaller regional television channels. The Georgian print press is very diverse, but very limited in circulation. The majority of Georgians receives news through the broadcast media.

The popular Imedi television station was founded in 2002 by wealthy businessman Badri Patarkatsishvili, a former close associate of exiled Russian tycoon Boris Berezovsky. Imedi became increasingly critical of the authorities after Patarkatsishvili fell out with Saakashvili's government in 2006, allegedly amidst business disputes. The station aired investigative pieces into controversial subjects, including on the murder of Sandro Girgvliani, head of United Georgian Bank's international relations department, by Ministry of Interior employees in January 2006.[20] Government officials criticized Imedi, calling it an opposition mouthpiece, and refused all invitations to participate in debates or talk shows on Imedi.[21]

In August 2006 News Corporation, run by media mogul Rupert Murdoch, acquired a 49 percent stake in Imedi. Patarkatsishvili retained 51 percent of the shares.[22] Lewis Robertson, a News Corp executive, was named CEO of Imedi.[23] On October 31, 2007, Patarkatsishvili announced that he would sell an additional 2 percent of Imedi shares to News Corp to give it a controlling stake and transfer the management rights of his shares in Imedi to News Corp for one year. The transfer came three days after Patarkatsishvili announced his decision to finance the campaign of Georgia's united opposition.[24] The Georgian government has claimed that despite the October deal, Patarkatsishvili retained effective control over the television company, and dictated its editorial policy to advance his personal political goals.[25] Patarkatsishvili and News Corp deny these allegations.[26]

The Coup d'Etat in Recent Georgian History

Coups, attempted coups, and government allegations of coups have featured prominently in Georgia since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Georgia's first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, faced several coup attempts[27] and was ousted on January 6, 1992, after two weeks of bloody fighting in Tbilisi.[28] Following Gamsakhurdia's ouster, Georgia was plunged into civil war and political chaos for almost two years. In this period several coup attempts were made by Gamsakhurdia and his supporters, including on June 25, 1992, when Gamsakhurdia supporters seized the television and radio center in Tbilisi and urged people to gather and demand the return of the deposed president.[29]

During his 11 years as Georgia's leader, Eduard Shevardnadze survived repeated assassination attempts, and his government also alleged at various times the existence of plots to overthrow it.

In November 2003, following parliamentary elections that were largely considered fraudulent, thousands of demonstrators gathered on the streets of Tbilisi to protest the election results. On November 22, opposition leaders, including Mikheil Saakashvili, stormed the Parliament building and forced President Shevardnadze to resign the next day.

Since 2003 the Georgian government has alleged a number of coup attempts. On July 22, 2006, Emzar Kvitsiani, the leader of an illegal militia in the Upper Kodori Gorge region of Abkhazia (the only part of Abkhazia still under Tbilisi's control), announced that he refused to disband his militia as requested by the government and no longer recognized the government's rule in the area. Georgian troops entered the area and Kvitsiani fled Georgia. On July 29, police arrested Irakli Batiashvili, former security minister and leader of the small opposition Forward Georgia movement, on charges of failing to report a crime and assisting a coup attempt by providing "intellectual support" to Kvitsiani. The allegations were in part based on a secret recording of a phone conversation between Kvitsiani and Batiashvili on July 26, in which Batiashvili allegedly conveyed his view of public support for Kvitsiani. Irakli Batiashvili was sentenced to seven years' imprisonment in May 2007.

On September 6, 2006, Georgian police detained 29 supporters and allies of former security minister Igor Giorgadze, now a fugitive living in Russia, and charged 14 of them with treason and plotting to overthrow the government. Georgian authorities accused the Russian government of financing the coup attempt.[30] Thirteen of those charged were sentenced in August 2007 to prison terms of up to eight years and six months for plotting a coup, following a closed trial.[31]

Relations between Russia and Georgia

Political tensions between Russia and Georgia have persisted since South Ossetia and Abkhazia attempted to secede from Georgia prior to and following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Although both South Ossetia and Abkhazia remain de facto independent since early 1990s, neither Georgia nor the international community recognizes the regions' claims to independence. For many years, Georgian authorities have accused Russia of secretly supporting the separatist movements in both regions.[32]

After coming to power in 2004, President Saakashvili took an openly pro-Western stance, seeking political, economic, and military cooperation with the European Union (EU) and the United States (US), including membership in NATO.[33]Russia openly opposes Georgia's NATO aspirations.[34]

In 2006, Russia, a major market for Georgian exports, initiated a series of import restrictions on Georgian goods, including wine, mineral water, vegetables, and fruits.[35] On September 27, 2006, Georgian police arrested four Russian military intelligence officers, whom it accused of espionage. In response, Russia effectively introduced economic sanctions against Georgia, beginning with a halt to all air, land, and sea traffic, as well as postal communication.[36]Russia recalled its ambassador to Georgia and stopped issuing visas to Georgians.[37]Russian police undertook widespread inspections and closures of Georgian businesses in Russia and stopped, detained, and expelled thousands of ethnic Georgians from Russia.[38]

In November 2006 Russia's state-controlled natural gas company, Gazprom, threatened to more than double the price of gas supplies to Georgia for 2007, and Georgia accepted the price increase after Gazprom threatened to cut off supplies.[39]

In March 2007 Georgia claimed that Russian combat helicopters fired on villages in the Upper Kodori Gorge region of Abkhazia. A September report by the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia said that it was not clear who had fired at the Georgian territory.[40] In August 2007 Georgia alleged that a Russian attack aircraft violated Georgian airspace and dropped a guided missile, which did not explode, near two villages approximately 80 kilometers south of the Russian border. Russia denied the allegation.[41] Tensions remained high in September and October 2007 after a series of incidents involving Russian peacekeeping troops in Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

November 7, 2007

Widespread Use of Police Violence to Disperse Demonstrators

Dispersal of protestors and hunger strikers on the steps of Parliament

After the demonstrations began on November 2, 2007, each subsequent night a small group of demonstrators stayed on the steps of the Parliament building, including some individuals who had announced a hunger strike on November 4. On the night of November 6-7, they numbered approximately 70, including 41 hunger strikers.[42] A few policemen as well as three or four television journalists and a few cameramen also remained in front of Parliament through the night.[43] A section of Rustaveli Avenue in front of Parliament remained closed by police, who had barred traffic from entering the area since the protests started on November 2.

Because it had been raining for several days, a blue plastic tarp, approximately 20 meters long and three meters wide, had been propped up on poles taken from protestors' flags and on metal police barricades to shelter those spending the night on the steps of Parliament.[44] There was also a wooden platform and sound equipment used during the day by opposition leaders. There were no tents or other structures on the steps of Parliament or on the sidewalk in front of Parliament.

Several witnesses interviewed separately by Human Rights Watch consistently described the same sequence of events on the steps of Parliament on the morning of November 7. Sometime shortly after approximately 10-15 city garbage trucks and street cleaning vehicles arrived on Rustaveli Avenue and on the sidewalks in front of the Parliament building. Men in sanitation worker uniforms quickly collected garbage from the sidewalk.[45]

As the men cleaned the sidewalk, two buses drove down Rustaveli Avenue and appeared prepared to enter the section of Rustaveli Avenue in front of Parliament that had been closed to cars since the demonstrations began on November 2. Soon thereafter, at approximately , a large number of police officers in long yellow raincoats began to approach the front of Parliament from the direction of Freedom Square. The police began to file into rows on Rustaveli Avenue facing Parliament.[46] Some police coming from this direction placed metal crowd control barriers along Rustaveli Avenue and the sidewalk in front of Parliament, apparently in order to prevent people from going into Rustaveli Avenue.[47]

At the same time, a large number of police came along Rustaveli Avenue from the direction of the Marriott Hotel Tbilisi and Republican Square, and amassed on the sidewalk in front of Parliament. This group wore jeans, black coats, and masks.[48] Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch could not determine the exact number of police gathered on Rustaveli Avenue, but they appeared to number in the hundreds.[49] The garbage and street cleaning trucks that had arrived earlier appeared to be parked in such a way as to create a corridor for the police to approach the front of Parliament.[50]

After amassing, the police officers divided into three groups and quickly began to approach the hunger strikers, demonstrators, and journalists on the steps of Parliament. According to multiple witnesses, the police made no audible demand for anyone to disperse nor gave any indication that force would be used to disperse people who did not do so willingly.[51]

The first group of police rushed at the hunger strikers and other demonstrators, and without any warning began to pull them off of their makeshift beds and punch and kick them. This group of policemen made no attempt to arrest anyone.[52] Bidzina Gegidze, a former professional rugby player and opposition supporter who had spent the night on the steps of Parliament, described the actions of the police:

Without any warning, without any announcement from a megaphone or anything else, they came rushing towards us. I could only think of one thing, that the other hunger strikers were still sleeping and did not know what was happening. I yelled out, "Don't do it! Don't touch them!" Two or three of us tried to stop some of the police. We put our arms around them, but they burst past us and made a circle around the sleeping hunger strikers. I again ran toward the police and shouted, "I am also a hunger striker, don't touch them!" The police started to pull people off of their blankets and pads [for sleeping] and to punch them and throw them down the steps.[53]

Other witnesses similarly described the police attack on the hunger strikers. According to one journalist, who declined to be named out of concerns for his safety,

The hunger strikers were asleep and they were just waking up. The police just attacked and started to disperse people.Several policemen ran at us [journalists] and at the hunger strikers. The police were hitting people. They demolished the covering over the hunger strikers and turned it upside down. They were punching and kicking people. People shouted and screamed, "Leave us alone! What are you doing?" I was also at a loss for what to do. It happened so fast. People were scared and screaming and shouting.[54]

Witnesses described seeing the police beat Levan Gachechiladze, a member of Parliament from the New Right Party and one of four opposition leaders participating in the hunger strike. According to Tinatin Khidasheli, a Republican Party leader, who arrived at Rustaveli Avenue just as police began to approach the protestors, "The police grabbed Levan Gachechiladze and beat him even as he lay on the ground."[55] Bidzina Gegidze also described the police attack on Gachechiladze: "They were beating a lot of people, but they especially went after Levan. They hit him hard and he fell. He couldn't stand up. Five or six guys descended on him, kicking him. [A few of us] went to try to protect him. I wasn't resisting anymore. I was just trying to protect him. Some of our supporters dragged Levan away in order to protect him."[56] Witnesses described other instances in which demonstrators or those who had just arrived on the scene attempted to protect hunger strikers or other demonstrators, interfering with the actions of police.[57]

The second group of police approaching the steps of Parliament immediately went towards the eight to ten journalists and cameramen who were already filming the attack on the demonstrators. Some of this footage was later broadcast on television. One journalist told Human Rights Watch,

[The police] didn't say anything they came at us and grabbed the camera [from our station's cameraman], our microphone, and the tripod for my microphone. One of them hit me. He had grabbed my microphone and as I pulled back on it, his fist came forward and hit me in the lip. I shouted, "Leave us alone! We are doing our job!"[58]

The same witness reported that a journalist and cameraman from Russia Today fled the steps as the groups of police approached and were pursued by policemen for several hundred meters but managed to escape. Police confiscated the cameras and other equipment from all of the other journalists and cameramen present.[59]

Without their equipment, journalists were prevented from documenting the police attack on the demonstrators, which continued for approximately another 10 minutes. One journalist told Human Rights Watch, "The very reason I went into journalism was this idea to be where I was needed. What happened [on November 7] was really awful for me. They took away our right to do our job."[60]Police returned the journalists' equipment an hour after confiscating it.

At the same time as groups of police launched attacks on demonstrators and journalists, a third group of police moved directly towards opposition leader and former Minister of Conflict Resolution Giorgi Khaindrava. Khaindrava told Human Rights Watch that he did not resist the six men who surrounded him in order to detain him. "I put my hands behind me. They grabbed me and picked me up from behind by the belt of my pants and pushed my head down. They forced me forward and into a car. I was immediately taken to court," he said.[61] According to his lawyer, Khaindrava was initially charged with hooliganism, resisting arrest, and use of narcotics. The first two charges were dropped when the judge learned that the police officers filing the report and testifying at the court hearing were not present during Khaindrava's arrest.[62] Khaindrava was fined 400 lari (US$235) for refusing to submit to a drug test and then released.[63]

Government officials gave conflicting accounts of police actions on that morning. One Ministry of Interior official told Human Rights Watch that in the early morning of November 7, police had come to set up barriers to prevent protestors from entering Rustaveli Avenue from the sidewalk in front of Parliament. According to this official, because some of the demonstrators resisted police efforts to block access to the street and open the street to traffic, there were "minor clashes" between police and protestors, and Giorgi Khaindrava was arrested for resisting police.[64] Witnesses acknowledged scuffles with police, as described above, but none said they tried to stop police from blocking access to Rustaveli Avenue. Bidzina Gegidze said, however, that demonstrators verbally protested when they saw the approaching buses.[65]

Another Ministry of Interior official denied that police took any action with respect to demonstrators, but only that patrol and neighborhood police cleaned up garbage from the area in front of Parliament and on Rustaveli Avenue and opened the road to traffic.[66]

On the day of the events, Tbilisi Mayor Gigi Ugulava stated that the authorities had acted in the early morning of November 7 in response to opposition plans to set up tents, which he viewed as an indication of their intention to continue demonstrations until their demands would be met. He also stated that the small number of demonstrators remaining justified the government's desire to reopen Rustaveli Avenue to traffic.[67]

Violent dispersal of protestors on Rustaveli Avenue in front of Parliament

After the early morning police actions on the steps of Parliament, opposition party leaders and others went to the nearby office of the Republican Party where they publicly called for a demonstration at in front of Parliament. Many people did not wait until to gather, instead arriving in front of Parliament almost immediately. Some had seen on television some footage of the police dispersal of protestors earlier that morning.[68]

At about leaders of the opposition parties returned to the front of Parliament. Several hundred police in long yellow raincoats remained on Rustaveli Avenue. According to the Ministry of Interior, these police officers were unarmed, except for a few who had truncheons.[69] By approximately there were three lines of police surrounding the demonstrators and containing them on the sidewalk in front of Parliament, which holds at most a few thousand people, and preventing them from entering Rustaveli Avenue. The demonstrators were unarmed.

Demonstrators attempt to push through the police line on Rustaveli Avenue on November 7, 2007. 2007 Justyna Mielnikiewicz for The New York Times/Redux

Demonstrators break through the police line

As the number of demonstrators grew, to approximately 3,000-5,000 people,[70] it became increasingly difficult for police to contain them on the sidewalk. According to one witness, "There was a huge flood of people coming very quickly. There were so many people that they could no longer fit on the territory in front of Parliament."[71] Some individuals, including some opposition leaders, were talking to police and demanding that they allow the demonstrators to move into the street. Individual demonstrators also pushed policemen, who pushed back as necessary to maintain the police line. There were some scuffles between police and protestors.[72] Police made some arrests. At the same time, demonstrators continued to approach Parliament along Rustaveli Avenue and some of them amassed behind the police line.[73]

At approximately the Ministry of Interior ordered the police to retreat from the cordon they were maintaining in front of the Parliament.[74] Individual police officers moved away and the police lines broke apart and the crowd flowed into Rustaveli Avenue. As this happened, there were individual clashes between police and demonstrators.[75] One witness told Human Rights Watch, "I saw two policemen in yellow coats holding a young man by his arms and dragging him, while a third policeman punched him on the head. The boy was not resisting. I shouted, 'Don't beat him!' They saw that I was filming them with my mobile phone and they let him go."[76] A senior Ministry of Interior official told Human Rights Watch that four police officers were beaten by demonstrators and a police car was damaged. When asked to elaborate, the official stated that one policeman was struck in the back by a demonstrator using a flag pole, but did not provide detailed information about the other three.[77]

Nugzar N., a 19-year-old opposition supporter who had moved with the crowd onto Rustaveli Avenue, said that around 20 men dressed in black coats with hoods, whom he believed to be law enforcement agents, but who could not be identified, came and started fights with some of the protestors. Together with a friend, Nugzar N. started to move across the street and the men in black pursued him, grabbed him, and started kicking him. He told Human Rights Watch that he did not resist, as he was outnumbered and "it was nonsense to fight [back]."[78]

As the crowds continued to move through the police line, two policemen grabbed an employee of the Office of the Ombudsman who was in the midst of the crowd moving onto Rustaveli Avenue. When she told them that she was a representative of the Ombudsman," the policemen responded, "We don't care who you are!" and started to push her back toward the Parliament building.[79] A journalist approached and shouted to the policemen, "She is from the Ombudsman's Office. You don't have any right to touch her!"[80] In response, the police let her go.[81]

As they moved into Rustaveli Avenue, protestors pulled the metal barriers that the police had set up in front of Parliament to help control the crowd and formed a barricade line approximately from the corner of Chichinadze Street near School No. 1 across Rustaveli Avenue to the front of the Kashueti church.[82] Several thousand protestors amassed behind this line along Rustaveli Avenue towards Parliament facing in the direction of the Marriott Hotel Tbilisi.[83]

Deployment of riot police and other law enforcement personnel

When the patrol police were ordered to retreat from their line, riot police and other law enforcement personnel, who had been mobilizing at Republican Square and elsewhere, were called in.[84] They moved towards Parliament from the direction of Republican Square and established their own line across Rustaveli Avenue stretching approximately from the corner of Lesia Ukrainka Street and the edge of School No. 1 to the front of the Blue Gallery. Police also brought in two large blue trucks labeled "Police," at least one equipped with a water cannon apparently designed for crowd dispersal. There were also ambulances and fire trucks behind the police line on Rustaveli Avenue.

The first line of law enforcement personnel consisted of riot police in plastic helmets and holding plastic shields and truncheons. Behind them were other personnel in various types of dress. Many were in camouflage uniforms; some of those wearing camouflage had helmets, some had black cloth ski masks, and some were also wearing black plastic body armor. Others were dressed in all black and wearing black ski masks, typical of Georgian special forces troops. Yet another set of forces wore jeans, black jackets, and black ski masks; some of the black jackets had "Criminal Police" written across the back. The police in yellow raincoats also gathered near or behind the police line. No witnesses whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said they saw any of the law enforcement personnel wearing any visible form of identification such as a name or number badge.

Security forces prepare to confront anti-government protesters on Rustaveli Avenue in downtown Tbilisi on November 7, 2007. 2007 AP Photo/George Abdaladze

According to Shota Utiashvili, head of the Ministry of Interior's Analytical Department, only two types of law enforcement personnel were deployed on Rustaveli Avenue that day: riot police in full crowd control gear, who made up the front lines, and regular patrol police, including many from outside of Tbilisi. When asked about the lack of uniforms on some law enforcement personnel and the various forms of dress, Utiashvili replied that the black uniforms were used for patrol police and criminal police brought in from the regions as reinforcements for whom uniforms were not available.[85] Another Ministry of Interior official stated that there were only riot police engaged in the operations on November 7, after patrol police were pulled aside.[86]Both officials also claimed that black face masks were typical for police engaged in riot control in all countries.[87]

It was not possible for Human Rights Watch to determine the exact composition of law enforcement personnel operating on Rustaveli Avenue. However, a doctor interviewed by Human Rights Watch told us that one law enforcement officer admitted to City Hospital No. 1 stated that he was a member of the special forces of the penitentiary department, which are under the authority of the Ministry of Justice.[88] Many witnesses referred to the law enforcement officers as "special forces" and some witnesses speculated that some of those participating werenot officially part of any force structure.

Warnings to disperse

At approximately 12:30 p.m., using a loudspeaker, police began to demand that the crowd clear the street and to warn that if people did not disperse, police would be required to use all legal means to disperse the crowd. According to witnesses, the announcement was repeated several times.[89] The Ministry of Interior maintains that the announcement was made for 10 minutes.[90] Some witnesses told Human Rights Watch that the announcement was difficult to hear, as there was a great deal of noise from the crowd itself.[91] Human Rights Watch could not determine whether some protestors began to disperse in response to the announcement, but video evidence and witness testimony confirm that at least the front lines of demonstrators did not make any attempts to disperse.[92]

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that some protestors remained standing in place with their hands up.[93] Video and photographic images confirm this.[94] According to one witness, some people also said, "Let's get on our knees so that they won't take any action against us."[95] Opposition party activist Nuzgar N., who stood at the front of the crowd of protestors, told Human Rights Watch, "My friends and I stood behind the metal barriers [facing the riot police] and put our hands up. We shouted, 'We are all Georgians, don't use force against us.'"[96] A senior Ministry of Interior official described the "crowd of 5,000 people" as "very violent," although he was not himself present.[97]

Immediately following the warnings for the crowd to disperse, law enforcement personnel began firing bursts of water from the water cannon at the front line of protestors. A few demonstrators were knocked down by the force of the water. Some demonstrators began to move away from the water.[98] However, most protestors remained in place, defying the police orders to disperse. Some waved their fists and shouted at the police.[99] The Ministry of Interior claimed that "the water cannon was not effective in dispersing people,"[100] although witnesses testimony and video evidence reveal that law enforcement officials used the water cannon for a very short time and only at the very front line of protestors.[101]

Use of teargas and rubber bullets

The evidence available to Human Rights Watch strongly suggests that law enforcement officials did not fully exhaust the use of warnings and water cannons to disperse demonstrators before resorting to more severe methods of crowd dispersal, including use of more extreme force. When many protestors refused to clear the street after verbal warnings and a limited use of water cannons, riot police began to use force, initially firing teargas into the crowd and firing rubber (or plastic) bullets at demonstrators.[102] They gave no warning that these methods would be used.

In using teargas and rubber bullets simultaneously against protestors, the government failed to implement a measured escalation in its response to the demonstrators. That law enforcement officials were authorized or chose to use rubber bullets at all, when at most there was sporadic violence from few demonstrators, and most demonstrators fled quickly as a result of the overwhelming effects of the teargas, raises serious concerns. Because rubber bullets may in certain circumstances have lethal force, they must be treated for practical purposes as firearms. They should be used strictly in accordance with the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officers, which state that "law enforcement officials must not use firearms against persons except in self-defence or defence of others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury."[103]

Human Rights Watch was not able to fully document injuries resulting from the use of rubber bullets. A detailed forensic examination into the number and type of injuries documented as a result of the use of rubber bullets should be a key aspect of the Georgian government's investigation into the use of force on November 7, as should accountability for those using and ordering the use of rubber bullets in a manner inconsistent with the UN guidelines.[104]

One witness who stood at the front of the demonstrators and had refused to move even after the official requests told Human Rights Watch that immediately after the water cannons were used, "I saw [law enforcement officers] put on gas masks and I realized that they would use teargas. Without any announcement they began to shoot the gas canisters over my head [into the middle of the crowd]."[105] Paata Zakareishvili, a Republican Party activist and prominent political analyst, went to the demonstration with his wife and two children. He confirmed there were no warnings before teargas or rubber bullets were fired into the crowd. Another participant called the use of the teargas "completely unexpected."[106]

People fled immediately in response to the teargas and rubber bullets. Many people panicked, and the atmosphere became chaotic as people ran in all directions,[107]suffering burning eyes and throats and other effects of the teargas. Most people ran onto the side streets leading away from Rustaveli Avenue. Others sought shelter in the Parliament building, in the KashuetiChurch, and in School No. 1.

A young woman flees after riot police attempt to disperse protestors with teargas and rubber bullets on Rustaveli Avenue on November 7, 2007. 2007 Dato Rostomashvili

A Human Rights Watch representative who monitored the events saw that the large volumes of teargas left several hundred meters of Rustaveli Avenue almost completely covered in gas.[108] Witnesses reported that the teargas caused the eyes, nose, and throat to burn severely and left many people nauseated and short of breath, often making it difficult for them to disperse.[109] The Human Rights Watch representative and others witnessed many people vomiting, including many policemen who, unlike the riot police and other law enforcement officials, had not been given gas masks or any other gear to protect them from the teargas.[110]

The large number of demonstrators and limited exits for dispersal made it difficult for people to flee quickly, causing them to be further exposed to the large amounts of teargas. According to one witness, "I ran to the small street in between Parliament and School No. 1. A large number of people also wanted to go up the same street, and it was packed. As a result, I could not run fast and had to breathe more of the gas.I fell down as I could not run."[111]

FormerState Minister of Georgia Avtandil Jorbenadze, who is 56 years old, went to Rustaveli Avenue after seeing television footage of the events earlier that morning. He described to Human Rights Watch his experience:

[After they shot the teargas] the results were strong and immediate. My eyes burned, I felt as if I was suffocating. I tried to help two young women who were sick, but then I felt very sick myself [and could no longer help them]. The crowd divided and one wave of people swept me and others towards Parliament. People were screaming and shouting. People were climbing the Parliament gates trying to escape the gas.[112]

The guards eventually opened the gates of Parliament to allow people inside, as the gas was accumulating in the doorway and causing people to become increasingly sick.[113]

Many people sought medical help after inhaling the gas, although most or all were treated and released after a few hours, including several children.[114] Typically, the effects of nausea, vomiting, eye irritation, and difficulty breathing would last for one to two days.[115] The Ministry of Interior did not name or identify the composition of the gas in any public statement, nor would it do so to Human Rights Watch.[116] A statement posted on the Ministry of Interior website on November 7 stated only that the gas is widely used in crowd control in many countries and is not lethal.[117]

One official claimed that the Ministry of Interior had informed the Ministry of Health about the use of teargas, but claimed that no hospital requested information about the chemical composition of the teargas.[118] A medical doctor interviewed by Human Rights Watch stated that it was "a big mistake" for the authorities not to make available information on the type or composition of the teargas that they planned to use. He said that ambulances on the scene and hospitals were unprepared to treat those suffering from the effects of the gas. [119]

Many people already suffering from the effects of the teargas entered School No. 1 in search of breathable air. Law enforcement officials pursued demonstrators fleeing into the school. One witness told Human Rights Watch that the door of the school was too small to accommodate the large group of people trying to enter and in desperation some young men broke windows in order to enter the building.[120] One witness reported that there was a large amount of gas in the school.[121]

During the operation on Rustaveli Avenue, law enforcement officials used long-range acoustic devices (LRAD), large round dishes that emit a strong, shrill noise that is apparently intended to disorient anyone within range of hearing it. Two police pickup trucks drove along Rustaveli Avenue equipped with these devices. The Human Rights Watch representative observing the events on Rustaveli Avenue described the noise as "unbearable," and one witness stated that the unbearable noise very much contributed to the initial panic among protestors.[122]

Attacks on fleeing demonstrators

Immediately following the initial use of teargas and rubber bullets, the police line advanced along Rustaveli Avenue toward the dispersing protestors who were fleeing in all directions. The Ministry of Interior maintains that "in only a few instances did police or riot police use violence against protestors," and that many small groups of demonstrators attacked policemen.[123] Human Rights Watch could not confirm the attacks on policemen during this particular period of the events on Rustaveli Avenue; witnesses did not elaborate on this and none of the video and photographic evidence viewed by Human Rights Watch provides corroboration for the allegations.

We did confirm, however, that dozens of individual law enforcement officials scattered to pursue protestors. In doing so, they also attacked and beat dozens of individuals, using truncheons, fists, and kicks. Some also shot rubber bullets at fleeing protestors at close range. Law enforcement officers attacked those demonstrators who continued to linger on Rustaveli Avenue, as well as those who were not able to flee or had already moved away from Rustaveli Avenue towards School No. 1, Parliament, the Kashueti church, or onto side streets. Witness testimony and video and photographic evidence confirm these attacks by police officers, riot police, and other law enforcement personnel on demonstrators and journalists.

Nugzar N. told Human Rights Watch that immediately after riot police launched teargas into the crowd, he ran from Rustaveli Avenue and entered School No. 1, but quickly came out again because the gas inside was so thick that he could not breathe. As soon as he emerged from the school, "Six policemen in yellow raincoats grabbed me and said, 'We saw you [supporting the opposition].' One of them hit me on the head with a truncheon. I was trying to run away. They dragged me across Rustaveli and said they wanted to take me to the police station," he told Human Rights Watch.[124]

Only when another policeman intervened on his behalf was Nugzar N. released. Nugzar N. found an ambulance nearby and was taken to hospital. He received several stitches in the top of his head, but did not suffer a concussion or any other physical injuries. Nugzar N., a law student, told Human Rights Watch that he will not file a complaint against the police who attacked him. "I think that making a complaint would be in vain. I do not trust the judiciary in Georgia," he told Human Rights Watch.[125]

Vakho Komakhidze told Human Rights Watch that he, too, sought shelter in School No. 1 and immediately ran up the stairs to the second floor, where he stayed for several minutes. Looking out the window, he witnessed how five or six riot police in gas masks dragged a young man, about 25 years old, from the front of the school building and began to beat him: "They threw him to the ground and kicked him. The man managed to stand up and appeared to beg that they stop beating him. Another policeman intervened [and the beating stopped]. But as soon as this policeman left, the others started beating the protestor again."[126] Komakhidze left the school at that time and did not see what happened to the young man.[127]

Avtandil Jorbenadze had fled toward Parliament but as the gas cleared he returned to Rustaveli Avenue, where he was attacked by masked law enforcement officers. He told Human Rights Watch,

I saw that Rustaveli Avenue was mostly clear, and I saw a Public Television reporter with a camera and I thought I should make a call for the authorities not to continue the attack [on demonstrators] because there could be very negative consequences. I made my way across Rustaveli to the cameraman. I was halfway across Rustaveli Avenue when I was attacked.[128]

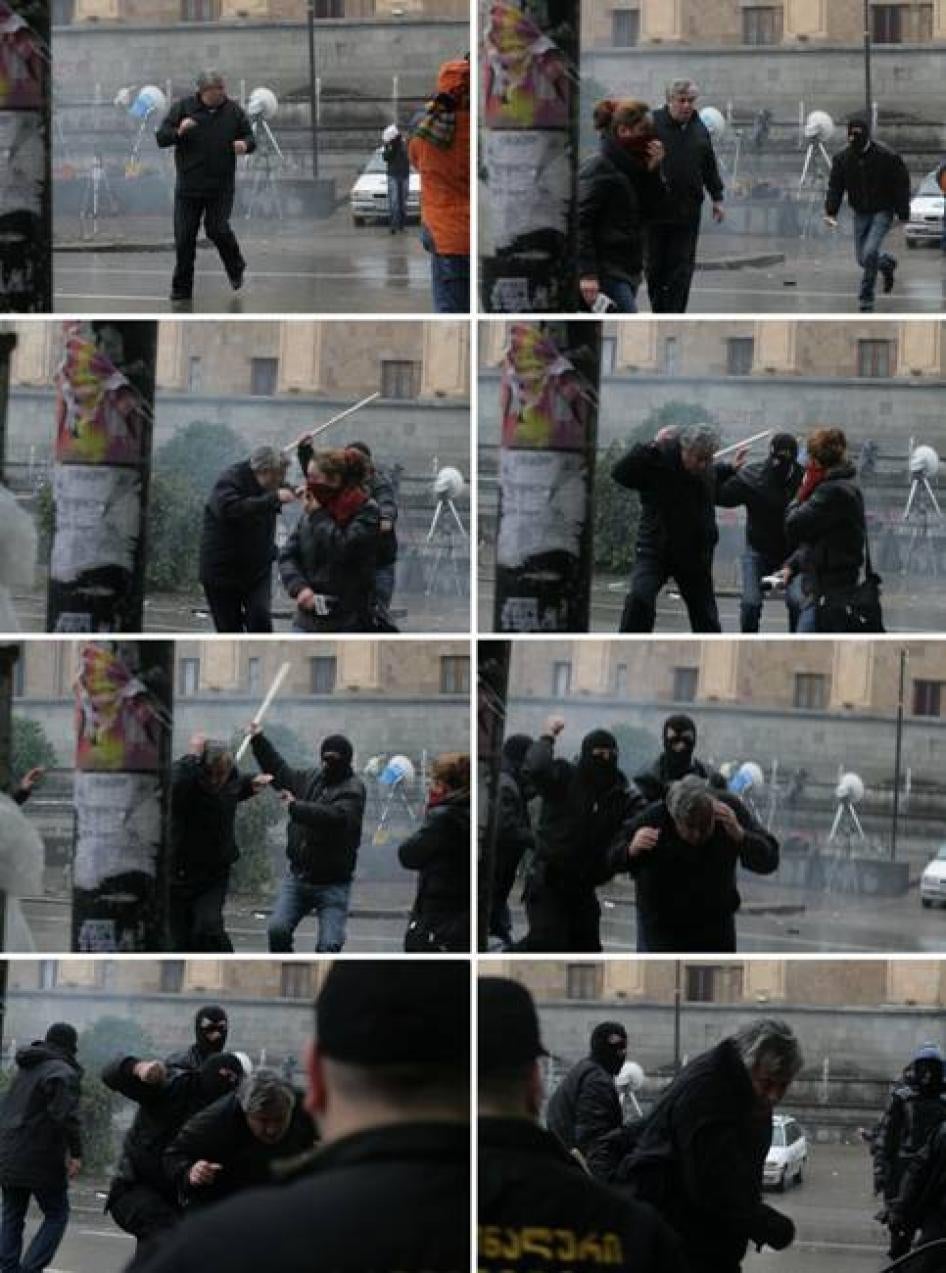

Masked law enforcement officers attack former State Minister Avtandil Jorbenadze as he tries to cross Rustaveli Avenue after riot police dispersed thousands of demonstrators with teargas and rubber bullets.

Photo evidence shows a law enforcement officer in a black mask and blue jeans approaching Jorbenadze from behind and striking him several times with a wooden stick, approximately one meter long, as Jorbenadze made his way across the street. Jorbenadze described to Human Rights Watch what happened as he moved away from this attacker and made it to the other side of the street. He was in the yard in front of the KashuetiChurch when

six or eight people attacked me. Unfortunately I fell down. They beat me very severely with sticks, fists, and kicks and continued to beat me even while I was down [on the ground]. Some people who came to assist me were also beaten. I think that when they saw that I was lying still, they stopped beating me.[129]

A law enforcement officer prevents additional attacks on former State Minister Avtandil Jorbenadze, who lies on the ground after masked law enforcement agents struck him with a wooden stick and then punched and kicked him.

Photos show a crowd gathered around Jorbenadze as he lies on his side on the ground trying to protect his head and face with his hands and arms as law enforcement officers in black masks kicked him. Law enforcement officers said nothing to Jorbenadze during the attack and made no attempt to arrest him. As a result of the attack, Jorbenadze suffered a concussion, a broken finger on his right hand, and multiple contusions all over his body, including on the back of his head, on his neck, shoulders, sides, arms, and hands. His eyesight was affected for several days as a result of exposure to large amounts of teargas. He told Human Rights Watch that he did not file a complaint regarding his attack.[130]

Nino Soselia, a 60-year-old pensioner who is not affiliated with any political party, was attacked by law enforcement officials immediately following the initial use of teargas. Soselia had seen the protestors gathering while watching television. She told Human Rights Watch, "I decided to go [to Rustaveli Avenue] because I wanted to be with my people."[131] When she arrived, Soselia joined the crowd, standing near the corner of Rustaveli Avenue and Chichinadze Street, in front of School No. 1. She considered leaving the demonstration when she saw riot police arriving on Rustaveli Avenue, but other demonstrators persuaded her to stay:

People were calling out, "Don't disperse. Don't be scared. Let's stay together." We raised our hands and continued to stand. [After the teargas was launched], a wave of people moved up Chichinadze Street and pushed me towards School No. 1. It was a completely chaotic environment. People fell down. When the [law enforcement officers] started to attack people, they did so mercilessly. They did not distinguish between man, woman, big, small, child. I tried to protect a boy who was shouting "Georgia! Georgia!" He was about 14 years old. He wasn't swearing or anything. Riot police were coming to attack him.

A riot policeman in a white gas mask started hitting me on the head with a rubber truncheon. I shouted, "Tell me! What do you want?" He didn't answer my cries for him to stop. I hit the policeman back. I resisted. After he hit me, he grabbed me and threw me into the wall of School No. 1. I hit my right shoulder and my back and even now I still have pain in my shoulder when I try to move it. After I hit the wall, I felt very bad. Some demonstrators helped me across Rustaveli and towards the opera and I went home.[132]

Soselia did not immediately seek medical attention, but she had headaches and felt very ill, so on November 8 she went to hospital. She was diagnosed with head trauma and severe bruising. At the time of her interview with Human Rights Watch Soselia continued to complain of headaches, was bedridden, and had difficulty moving or sitting up in bed.[133]

Soselia witnessed policemen in yellow raincoats beating the teenage boy whom she had tried to protect. She told Human Rights Watch that a large number of policemen dragged the boy and other boys away. As she was being assisted and led away by other demonstrators, she also witnessed policemen beating others. "Police even beat those who had fallen down and were helpless, including the elderly who had fallen down after being pushed by the waves of running people," she said.[134]

Nikoloz N., age 36, also described to Human Rights Watch the severe beating he received by several police officers near the April 9 Park:

I was running as fast as I could.Several police [and law enforcement officers] came after me. One dressed all in black grabbed me and after a few more steps I fell down. They jumped on me. They beat and kicked me. I tried to protect my head. There were probably 15 people kicking me. There were so many of them who wanted to kick me, they were saying to each other, "Move over, I also want to [kick him]. Give me a shot!" Only after two priests and a woman appeared and started screaming did these guys move away from me.

I could hardly breathe. I thought I had broken a rib. [Someone] put me in a taxi and I went to the hospital. I had damage to the pleura [the membrane surrounding the lung].[135]

Nikoloz N. received surgery on his lung. He also had severe bruising over much of his body and pain in his liver, kidney, and sides.[136]

One journalist who was covering the events on Rustaveli Avenue described an attack on an elderly woman on the steps of Parliament. This witness stated,

By that time the square was mostly empty of [demonstrators]. I saw an elderly woman collapse near the fountain [in front of Parliament]. She [appeared to be] sick from the teargas. Some special forces in black plastic body armor hit her with a truncheon on the back several times. An ambulance drove up and took her away.[137]

A Human Rights Watch representative also witnessed police beatings of demonstrators well after the area in front of Parliament had been cleared. He saw several groups of five or six policemen each beating demonstrators near the Kashueti church. At least two of the victims were lying on the ground while police kicked them.

At least two witnesses described law enforcement officers' use of rubber bullets against fleeing protestors. One of them, Giorgi Gotsiridze, an employee of the Ombudsman's Office, told Human Rights Watch, "[After running from Rustaveli Avenue], I went behind Parliament to Chitadze Street. I saw about 100 protestors running, and they were being chased by riot police, shooting rubber bullets at their backs at close range. There were about 30 riot policemen. Several of them were shooting rubber bullets, directly aiming at the backs of fleeing people."[138]

Human Rights Watch received reports of several attacks on journalists covering the demonstrations and the police response on November 7.[139] A Ministry of Interior official was quoted as saying that "every officer had clear instructions not to touch journalists."[140] After the first dispersal of protestors, law enforcement officers in black masks attacked Imedi journalist Levan Tabidze near School No. 1. He and his cameraman had sought shelter from the teargas by going into School No. 1 for about 15 minutes. When they left the school, Rustaveli Avenue had been mostly cleared of people, but Tabidze and his cameraman started filming riot police chasing fleeing protestors up Chichinadze Street between the school and Parliament. Tabidze told Human Right Watch,

It was one of the worst things I saw that day. A man was walking up the street between Parliament and School No. 1. Riot police were coming down the street. Without any apparent reason they attacked him one by one. As each [policeman] passed him, they would hit him. I remember his face very well. I was at a loss. I could not believe that this was happening to him. We were filming this all.

I started to walk up the side streets. We weren't filming at that point. People were gathering in groups. All of a sudden some [law enforcement officials] came at me and were yelling, "Badri [Patarkatsishvili], Fuck your mother!" They saw that I had an Imedi microphone and they came at me, swearing at me, yelling, "Badri's puppies-this is what you get!" I was yelling, "I am just working!" Then they started to beat me.

I put both of my hands up and continued to hold the microphone in one hand. I repeatedly said, "I am just doing my job!" Another Imedi journalist was there shouting and swearing, saying "Leave him alone!" One of the policemen hit me with a truncheon from behind on my left leg. They continued to swear at me. I also remember very clearly that one of the policemen said to me, "This is nothing. We will come to you [Imedi] this evening and fuck you all."

A man who seemed to be a commander or leader of these policemen ran down and intervened. He said, "What are you doing? Why him?" He seemed very angry. After this the beating stopped. The pain in my leg was very bad. I couldn't move my leg. I sat down for about 15 minutes before I could get up and leave. I continued to limp the next day.

I couldn't understand this aggression against me because we weren't even filming them anymore. I understood that this was not personally against me but against the television station and me as a journalist of this television station. I think that the logo on the microphone made me a target of the attack, but I also feel that maybe they didn't go as far as they could have because of the microphone and they could see that I was a journalist.[141]

Police did not attack the Imedi cameraman who was with Levan Tabidze at this time.

The Ministry of Interior denied that there were attacks on fleeing demonstrators. When asked about the approved use of a truncheon, a senior Ministry of Interior official told Human Rights Watch that truncheons are used only as a defensive weapon by riot police attempting to maintain a police line.[142] When asked about the wooden stick that was used by a law enforcement officer to attack Avtandil Jorbenadze, a senior Ministry of Interior official denied that such a stick is part of the approved equipment for riot police or others engaged in crowd dispersal. He stated that any object of that description was probably a flag pole taken from the flags being carried by the demonstrators.[143] Other witnesses described seeing law enforcement officers wielding these wooden sticks and using them as weapons.[144]

During the operation many law enforcement officials used highly intimidating and threatening language, mainly directed against Badri Patarkatsishvili, apparently because of his financial support for some opposition parties. When attacking Imedi journalist Levan Tabidze, phrases used by law enforcement officers indicated they were targeting him because he was employed by Imedi, which was founded by Patarkatsishvili. Video footage shows law enforcement agents in all black marching on Rustaveli Avenue chanting, in the military style of a rhyming question and response, "What [do we have] for Badri?" "[We're gonna] fuck Badri's mother!" This kind of language directed against a person with strong links to Georgian opposition parties is deliberately threatening and intimidating to anyone who would wish to support the political opposition or participate in opposition-organized public demonstrations.

The violent dispersal of protestors on Rustaveli Avenue, from the Marriott Hotel to Republican Square

After the dispersal of people on Rustaveli Avenue in front of Parliament, as described above, some riot police, police in yellow raincoats, and other law enforcement personnel walked along Rustaveli Avenue in front of Parliament and others pursued demonstrators and beat many. Further down Rustaveli Avenue in the direction of Republican Square, a line of riot police stretched across the avenue in front of the Marriott Hotel Tbilisi. This cordon had apparently been established to protect from behind the riot police and other law enforcement officials engaged in the dispersal of the demonstrators in front of Parliament.

Very soon after the riot police started dispersing the demonstrators in front of Parliament, crowds began to gather along Rustaveli from the direction of Republican Square and approached this rear guard of riot police, who turned to face them. The crowd most likely consisted of some of the same demonstrators who had been dispersed from the front of Parliament and had circled around using small side streets to reach Rustaveli Avenue again as well as additional demonstrators just arriving from the direction of Republican Square.

As the crowd continued to gather, the front lines of protestors moved directly to the line of riot police, separated by only a few meters. Photographic evidence shows protestors damaging a police car on Rustaveli Avenue, near the Drama and Ballet Theatre. A few protestors threw stones and swore at police, although some witnesses reported that other demonstrators attempted to subdue those who were acting aggressively.[145] Otherwise, most demonstrators were not aggressive.

Around , opposition leaders made their way to Rustaveli Avenue. Tinatin Khidasheli told Human Rights Watch that she and other opposition leaders sensed the crowd might press forward into the police line and so used a megaphone to tell people to stop moving forward.[146] Paata Zakarieshvili confirmed this, saying people were moving toward the riot police and were cursing and yelling. He said he and several opposition leaders stood between demonstrators and the riot police. Zakarieshvili told Human Rights Watch, "This was a very nervous situation. We stood like this for maybe about 10 minutes. We really didn't want people to clash with police."[147] Khidasheli stated that she spoke with the riot police on the front line and explained to them that the crowd would not act against them.[148]

At approximately riot police started to push forward into the demonstrators. They again fired a volley of teargas into the crowd and opened fire against demonstrators using rubber bullets. Multiple witnesses told Human Rights Watch that no warning was given.[149] Tinatin Khidasheli, who was standing at the front of the crowd, told Human Rights Watch that a teargas canister hit a tree branch above her and both the branch and the tear gas canister fell down on her, knocking her unconscious. Others later told her that after she collapsed, law enforcement officials in black masks kicked her. "I don't know what happened," she said, "But I am covered in bruises on my back and legs."[150] Khidasheli also had a severe allergic reaction to the teargas, which engulfed her.

The Human Rights Watch representative witnessed how following the launching of the teargas and rubber bullets, many protestors fled. However, several hundred people continued to linger on Rustaveli Avenue, and, because the wind blew much of the teargas back towards the riot police maintaining the cordon across Rustaveli, the air would clear and demonstrators would again steadily advance toward the riot police line. Ambulances standing along Rustaveli Avenue amidst the protestors had handed out surgical masks to help people cope with the teargas. Several witnesses confirmed that protestors retaliated against the police at this point.[151] According to one witness, "The protestors cursed the police and yelled, 'What are you doing? Why are you beating people?' Some protestors threw the teargas canisters back at the riot police. Others threw whatever was at hand: rocks or pieces of brick from the sidewalk [which was under repair]."[152]

A protestor hurls a teargas canister back at police on Rustaveli Avenue. 2007 Dato Rostomashvili

Meanwhile, other law enforcement officers again pursued the protestors who fled. Some continued to fire teargas canisters at people who fled while others swung truncheons and attacked individual protestors. One witness said that he ran into the courtyard of a building off of Rustaveli Avenue and sought shelter in a small shed located in the yard. He told Human Rights Watch,

After about five minutes I came out of the shed and looked out onto the street. One special forces officer saw me and turned and started to shoot at me with rubber bullets. I ran into the courtyard again and another special forces officer chased me and threw a gas canister at me. The smoke was so strong that I felt I was losing consciousness, and again ran into the shed. After 10-15 minutes, I ran out again, but the [teargas] smoke was still so thick that I went back into the courtyard and stayed another 30-40 minutes before I left.[153]

As had happened previously, law enforcement officials, particularly those in black masks, pursued the fleeing demonstrators and beat them.

Among those beaten was Georgia's ombudsman, Sozar Subari, who had arrived on Rustaveli Avenue at approximately 10 a.m. and was monitoring the demonstration and police response. In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Subari described the attack:

[Law enforcement agents] in blue jeans and black masks were beating one young man. They were kicking him. I bent over to help him and they started to beat me. There were three or four of them. They used truncheons and wooden sticks. I told them, "I am the Ombudsman!" They seemed to beat me even harder after that. I simply stood. They beat me on my arms, back, and legs. One of my employees yelled, and eventually they stopped beating me.[154]

Subari did not seek medical attention, but he complained of bruising on his back, shoulders, sides, arms, and legs.[155] Human Rights Watch representatives documented extensive bruising on Subari's legs.

Another official from the Ombudsman's Office told Human Rights Watch, "I saw three or four police in black masks beating a man. He was 45 to 50 years old. He fell and they continued to beat him with truncheons and started kicking him. I've never seen anything like this in my life."[156] Another witness told Human Rights Watch that he saw men he described as special forces pursuing demonstrators down Rustaveli Avenue. "I was standing [on the edge of the street] and I saw how they attacked several people with truncheons. There were even women. The women started cursing them and saying, 'We are your daughters and your mothers.'"[157] Paata Zakareishvili, who fled from Rustaveli Avenue, told Human Rights Watch that the police pursued him and others and shot rubber bullets and teargas canisters as the demonstrators fled.[158]

The violent dispersal of protestors at Rike

Crowds assemble

Although some people left Rustaveli Avenue following the second attack on protestors, witnesses reported that the majority of the crowd seemed unwilling to completely disperse. Opposition leaders took a decision to encourage everyone to go to Rike (pronounced REE-khay), a large open area several kilometers from the Parliament building and located on the other side of the Mtkvari River, which flows through the center of Tbilisi. Rike is a partly paved and partly grassy area that is regularly used for drivers' education classes and had been used in the past for large concerts. It is approximately 500 meters long (from north to south) and 200 meters wide (from west to east) with a large rock outcrop rising directly on the eastern side. It is accessed by the BaratashviliBridge and the MetekhiBridge from the western (river) side and by three roads rising steeply on the east side on either side of the outcrop.

Map of Rike