How to Fight, How to Kill:

Child Soldiers in Liberia

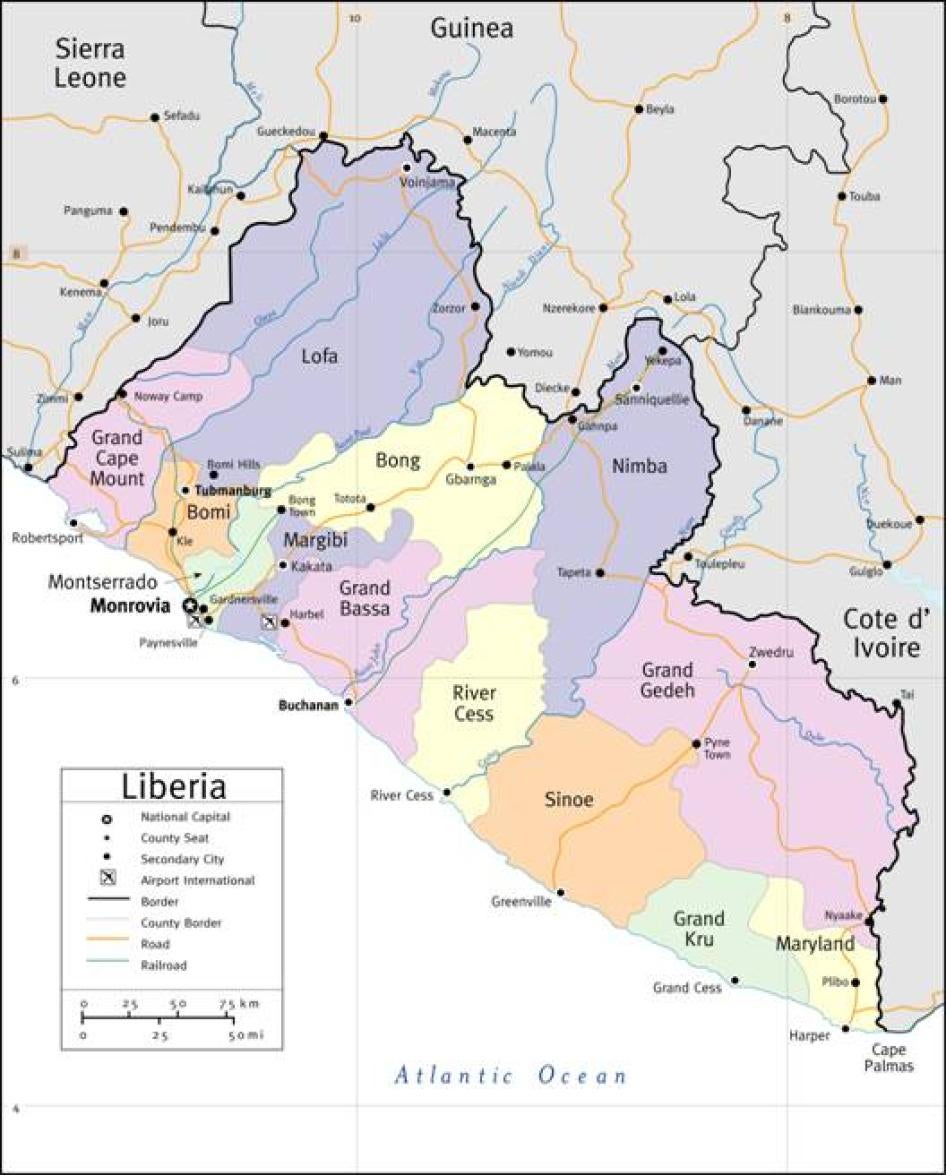

MAP OF LIBERIA

Summary

They [the LURD] caught us near the camp and we have been with them for two months.Training was very hard.They show you how to fight, how to kill. . .During the war, we went as far as the Stockton bridge but had to retreat.I saw plenty people killed, even young children.It was terrible.

-George H., sixteen years old, October 25, 2003.

Many of them were forcibly recruited, drugged, beaten, and made to commit horrible acts.These children killed, raped and abused members of their own communities.Because of these acts, they are both victims and perpetrators.

-Child protection worker, Monrovia, October 29, 2003.

Over the last fourteen years, Liberians have known little but warfare.Conflict and civil war have devastated the country and taken an enormous toll on the lives of its citizens, especially children.Thousands of children have been victims of killings, rape and sexual assault, abduction, torture, forced labor and displacement at the hands of the warring factions.Children who fought with the warring parties are among the most affected by the war.Not only did they witness numerous human rights violations, they were additionally forced to commit abuses themselves.

Both of the opposition groups, the Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) and the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL), as well as government forces which include militias and paramilitary groups widely used children when civil war resumed in 2000.In some cases, the majority of military units were made up primarily of boys and girls under the age of eighteen.Their use and abuse was a deliberate policy on the part of the highest levels of leadership in all three groups.No precise figures exist as to how many children were used in the last four years of warfare; however, United Nations (U.N.) agencies estimate that approximately 15,000 children were involved in the fighting.[1]

Although international law prohibits the use of children in armed conflict, thousands of children, some as young as nine and ten years old, were used by the fighting forces in Liberia.The use of child[2] soldiers poses a serious threat to the rights of children, including their rights to life, to health, to protection and to education.Many child soldiers have suffered egregious abuses:forced conscription into the armed groups; beatings and other forms of torture; and psychological damage resulting from being forced to kill others.Girl soldiers have suffered the additional humiliation of rape and sexual servitude, sometimes over periods of several years.

Children interviewed for this report spoke of the general hardships of war and of the particular difficulties of their lives as fighters.Many of the children were forcibly recruited into the fighting forces during round-ups conducted by government forces or during raids on refugee and internally displaced persons (IDP) camps by LURD and later by MODEL fighters.Other children volunteered to fight.Reasons some cited for this decision included a desire to avenge abuses against themselves or their families, a need to gain some form of protection, or a perception that this was the only way to survive.

Boy and girl fighters typically received limited training in operating automatic weapons, mortars and rocket propelled grenades.Taught to maneuver in combat, to march, and to take cover, children were often the first sent out to the front lines where they faced heavy combat.Children were also charged with other tasks such as manning roadblocks, acting as bodyguards to commanders, looting from civilians and abducting other children.Although younger children were generally used as porters, cooks, cleaners and as spies, children as young as nine and ten were sometimes armed and active in combat.

In addition to their military duties, girls with the armed groups were raped and sexually enslaved by the fighters.One girl who spoke with Human Rights Watch, fourteen at the time of her abduction, was raped by many fighters and later assigned to a commander as a wife.Girl fighters were collectively known as 'wives', whether attached to a particular soldier or not.Some older girls were able to avoid sexual abuse, sometimes by capturing other girls for sexual servitude.

Children described beatings, torture and other punishments inflicted on them by commanders for alleged infractions of rules.Children were tied and beaten for stealing, for failing to follow orders, and for abusing the civilian population.Nevertheless, child soldiers were complicit in abuses against civilians-including murder, rape and widespread looting-often committed with the involvement of their adult superiors.Boy soldiers were often drugged prior to facing combat by commanders handing out pills.Boys described these drugs as making them feel fearless during fighting.

An enforced ceasefire brought an end to much of the fighting in Liberia in August 2003 and the presence of peacekeepers from the U.N. Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) has brought some security to the capital Monrovia and its immediate environs.Many of the children involved with the warring parties have since left their units.However, in areas outside of UNMIL control, children remain actively engaged with the fighters.

An extensive demobilization program, scheduled to recommence in January 2004, includes specific provisions for child soldiers.Their rehabilitation, however, remains an enormous challenge: whole communities have been destroyed; populations have been displaced; and many children have lost one or more family members.Children who spoke with us expressed fear, confusion and concern about their future, underlining the need for psychological and practical support to help them readjust to civilian life.In addition, the widespread rape and sexual assault of girls necessitates urgent medical attention and for some girls, assistance in child support and care for their children.Human Rights Watch calls on the international community to fully fund the demobilization programs for child soldiers and to provide additional assistance to girls and women who are victims of sexual violence and abuse.

The vast majority of child soldiers told us of their desire to return to school, to receive an education and to make something of their lives.Some of the boy soldiers interviewed became fighters after having dropped out of school because they were no longer able to afford the costs.Many are now unsure of their ability to pay for schooling, as school fees and other related expenses make education unaffordable for many Liberians.The national transitional government has recently announced an ambitious program of universal primary education for all Liberians, but its implementation will require a significant investment.To make primary education available to all, the government must first pay teachers salary arrears, train new teachers, purchase school materials and rebuild and construct new schools and classrooms.

Human Rights Watch encourages the government to fulfill its international obligations to guarantee the right of primary education to all Liberians as a means of long-term rehabilitation.We call on the international community to assist the government in its endeavor, with appropriate financial and technical support so that all children affected by the conflict may receive an education.As one child right's worker in Monrovia suggested, a literate population with educational opportunities for all children could help prevent future conflict and children from taking up arms again.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in Liberia from August through November 2003.We conducted interviews with former and current child soldiers in the capital and surrounding displaced persons camps in Montserrado, and in Bomi and Grand Bassa counties.Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with over forty-five children and young adults who were members of the LURD, MODEL and militias and paramilitary groups of the government forces.Children ranged in age from ten to seventeen years old; some had been with the fighting forces for a few months, while others had been involved for several years.

We also conducted numerous interviews with members of the national transitional government of Liberia, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, church and civic leaders, members of the diplomatic community and representatives of the warring factions.The names of all children interviewed for this report have been changed to protect their privacy.

Recommendations

To the National Transitional Government of Liberia (including representatives from the former Armed Forces of Liberia, government paramilitary and militia forces, LURD, and MODEL):

- Immediately end the use and recruitment of all children under the age of eighteen in the fighting forces.Present any children currently affiliated with the forces to cantonment centers for demobilization and support and encourage these children, especially girls, to enter the demobilization programs.

- With coordination through the National Demobilization Commission, encourage all children who fought in the conflict to present themselves at cantonment areas for assistance.

- Make certain that rehabilitation programs for child soldiers are tailored to meet the special requirements of girl soldiers including the creation of special childcare centers for girl mothers and health and counseling programs for survivors of rape and/or sexual assault.

- Enact national legislation that would make eighteen the minimum age for recruitment to the newly formed national army.Ensure that such legislation contains punitive measures for those found in violation of the law.

- Sign and ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict.

- As a matter of priority, ensure the rights of children to free primary education by progressively eliminating as rapidly as possible all school fees and related costs for elementary education.Focus rehabilitation efforts on rebuilding the education system.Ensure that no child is denied enrollment to primary school and create accelerated schooling or other appropriate programs where necessary for war-affected children who have missed educational opportunities.

To All Donor Countries to Liberia:

- At the donors' conference on Liberia to be held in New York on February 5 and 6, 2004, ensure that necessary funding is given to fully finance the demobilization program.Specific financing should be pledged for rehabilitation and reintegration programs for child soldiers.

- Insist that rehabilitation programs for child soldiers include special provisions for girl soldiers.At a minimum, these should include health care and psychosocial counseling for girls who are survivors of rape and sexual assault and childcare centers for girl mothers.

- Recognize that the long-term well being of former child soldiers depends on both a successful demobilization program as well as longer-term rehabilitation projects which include child soldiers and all children affected by the conflict.Provide financial assistance to social services with emphasis on rebuilding the education system in Liberia with an aim to securing the rights to education for all children in the country.

- Support the U.N. peacekeeping force (UNMIL) so that it has the necessary financing and manpower to deploy throughout Liberia for the proposed two year period to protect children and all Liberians.

To the Government of the United States:

- Ensure that of the $200 million earmarked for Liberia, sufficient funding is provided to the demobilization program for children, with emphasis on rehabilitation and reintegration.

- Provide technical assistance to Liberia in all aspects of education, through teacher training, materials, school building and financial support to the Ministry of Education to help rebuild the system of education in Liberia.As security improves, consider sending professionals and volunteers to Liberia who have expertise in the fields of education and pedagogy.

To the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL):

- Engage and deploy as soon as possible the two proposed child protection advisors to assist the Secretary General's office in Liberia with related child protection activities for UNMIL personnel.

- Ensure that the human rights section of UNMIL works in coordination with the United Nations Mission in Cte d'Ivoire (MINUCI) to detect and report on the movement of child combatants from Liberia into neighboring Cote d'Ivoire.

- Have the human rights section of UNMIL properly document the use of children in combat during the last fourteen years of conflict so it may be used in future accountability mechanisms including the mandated Truth and Reconciliation Commission and possible tribunals with jurisdiction to try war crimes and other serious human rights violations.

To the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF):

- Continue to work closely with the Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation and Reintegration (DDRR) process, evaluating the programs for their appropriateness for former child soldiers to ensure that their needs are being met.Strengthen national awareness campaigns to ensure that the maximum numbers of children are involved in the DDRR process.Work closely with members of the Joint Implementation Unit (national coordination unit) so that the interim care centers are fully operational and contain the necessary elements to assist children.Ensure that adequate protection measures for girls are prioritized in the interim care centers.In addition, health and psychosocial care for those girls who were abducted and sexually abused should be provided in the centers.

- As security permits, establish regional offices in the countryside to facilitate successful reintegration and rehabilitation of child soldiers to their families and communities.Make certain that counselors and child protection officers continue to visit child soldiers in their homes for extended periods after their home placement.

To the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR):

- Enhance protection measures at refugee camps in Ivory Coast, Guinea and Sierra Leone so that Liberian and other children from the region are protected from recruitment into regional conflicts.

Background

The conflict in Liberia, which began in late 1989, when then rebel leader Charles Taylor launched an incursion from neighboring Cte d'Ivoire, has been characterized by brutal ethnic killings and massive abuses against the civilian population.Although the conflict is rooted in historical grievances, the brutal tactics employed from 1989 to 1997, including targeting of particular ethnic groups by Taylor's National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) and later the United Liberian Movement for Democracy in Liberia (ULIMO) were previously unknown in Liberian history.

In the almost eight years of fighting before a binding ceasefire was negotiated in 1997, numerous efforts to bring about peace were unsuccessful.In the interim, civilians suffered at the hands of the fighting groups; thousands of Liberians were killed in the fighting and subject to torture, beatings, rape, and sexual assault, resulting in massive displacement inside and outside the country.Following the ceasefire of 1997, Charles Taylor, former head of the NPFL, was elected as president of the country.

The Taylor government was marred by widespread corruption and abuse, further widening the divisions and deepening popular resentments caused by the civil war.State power was regularly used for the personal enrichment of government officials with little or no accountability to the Liberian citizenry.The LURD incursion from Guinea, which began in 2000, was the fifth serious outbreak of violence in Liberia since Taylor's election and launched Liberia back into four more years of civil warfare.[3]In 2003, a negotiated ceasefire, the departure of Charles Taylor from office and the country, and the deployment of regional and later international peacekeepers have brought an end to major conflict, although fighting and human rights abuses persist in areas outside the U.N.'s control.

The use of children as soldiers dates to the start of the conflict in 1989.Taylor's NPFL became infamous for the abduction and use of boys in war; a tactic later adopted by other Liberian fighting factions as well as other fighting groups in West Africa.[4]Between 6,000 and 15,000 children are estimated to have taken up arms from 1989 to 1997.[5]A demobilization program conducted in 1997 was only partially successful in rehabilitating children, in part due to limited funding and insecurity in the countryside.Many of the same children who had fought previously became easily re-recruited when fighting resumed in 2000.[6]

Recruitment of Children

The latest round of warfare to engulf Liberia began in July 2000 with the LURD incursion from Guinea into northern Lofa County.Fighting between LURD and government forces, characterized by territory changing hands from one group to the other and then back again, intensified in 2002 with a LURD offensive against the capital, Monrovia.LURD forces forcibly recruited adults and children to join their ranks drawing from Liberians living in refugee camps in Guinea as well as from areas of newly captured territory.Government forces also conducted conscription raids within neighborhoods in Monrovia, remilitarized former combatants and armed adults and children to fight against LURD.[7]In early 2003, MODEL split from LURD and began an offensive from its bases in Cte d'Ivoire capturing towns in eastern Liberia.

As LURD and MODEL each pushed towards Monrovia and Buchanan in the first half of 2003, these two groups together with government forces stepped up their recruitment of adults and children.While some children volunteered to join the forces, many others were forcibly recruited during recruitment drives or following the capturing of new territory as front lines switched hands.Some children joined particular forces to avenge violations committed against their family members.Conversely, some children joined those same forces that committed abuses in their communities to offer protection to themselves and their families.With the attacks on Monrovia from June through August 2003, more children became involved with the fighting forces both as combatants and helpers some driven by the need to help find scarce food and water for their families.

LURD Advance

As the LURD forces advanced on Monrovia in early 2003, they attacked displaced persons camps in Montserrado County, exchanging fire with government soldiers positioned nearby.The attacks prompted many civilians to flee closer to Monrovia while hundreds of others from those camps were forced to retreat with LURD back to bases in the interior.Among the groups of men and women were children targeted in the raids and subsequently trained to fight for LURD.Children now living in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps told us of the forced retreat with LURD, the recruitment and how they came to be involved with the forces.

According to one youth leader, who was present the day of the attack on Rick's Institute (a school outside of Monrovia) IDP camp:

LURD fighters came here and attacked; this was on March 25, 2003.They overran the camp and people tried to hide and flee the advance.There was fighting between the government troops and LURD and some people were killed by stray bullets.Following the exchange, LURD rounded up hundreds of residents and forced them to return to Bomi County.Many of the children involved in our programs were taken, boys and girls, only some have returned.I later heard that some of the girls, they died because of how they were treated, victims of torture and sexual assault.[8]

Seventeen at the time, Johnny S., was rounded up on the day of the attack at Rick's IDP camp:

I was captured by LURD together with plenty of others.My thirteen-year-old sister was among them.I haven't seen her since the war ended.They took us back to Bomi to be trained to fight. I was assigned for training but escaped a few days later when sent out for water.Born in Bomi County, I knew the area well and could escape. Others, like my sister, were not so lucky.[9]

Another of the unlucky ones, sixteen-year-old Isaac T., spent the next six months fighting for LURD:

We were all taken from here (Rick's IDP camp), at least fifty boys on that day.The youngest boy fighter was probably fifteen, younger ones were taken but only used for labor.We were taken to Bomi and trained in how to fire, how to take positions during the fighting.How to take cover and to dodge bullets.There were probably one hundred boys who did the training, the others came from neighboring camps.The training lasted about two weeks and right afterwards, I was on the front lines.[10]

From March through June, LURD forces came closer to Monrovia, attacking and retreating from IDP camps nearer the capital.At Jahtondo displaced persons camp, LURD attacked several weeks after the assault on Rick's camp, causing civilians, some of whom had fled earlier assaults at outlying camps including Ricks, to flee once again.At Wilson Corner IDP camp, in early May, LURD fighters clashed with government troops, causing panic and flight among the civilian population.According to two child soldiers, both the government forces and the LURD forcibly recruited children from the two camps at that time.[11]

Children also taken from Plumkor camp in May explained how they were abducted:"I was caught on the road, just outside of camp, when fleeing the LURD attack.I was taken to Bomi with a group of others and taught to fire, take cover and to kill."[12]Ellen S., who later became a female commander, was taken that same day."When LURD came, they caught a lot of young girls and carried us to Bong County.They can force you, you say no, but they carry you or they can beat you to death.They carried me to train-to learn to fight, how to fire, to dodge bullets and how to kill somebody.The training lasted two weeks."[13]

Not all children were forcibly recruited; others joined LURD because of the abuse they suffered at the hands of government soldiers.Children in the camps and greater Monrovia area described the abusive practice of government soldiers-rape and sexual harassment, beatings, stealing, and their obligation to perform labor.Youth leader Roland B., explained that in the months leading up to the LURD attacks, government soldiers were complaining that they were not getting paid. They additionally accusedresidents of being LURD sympathizers and took their frustrations out on the camp populations-not only stealing, but raping young girls in the camp and beating boys for refusing to perform labor.

Christopher J., a thirteen-year-old, third grade student, described the abuse by government forces:

Last year before the war came here, government fighters forced me to work for them.I was made to carry things from the surrounding areas to the paved road, where they would be collected.I had to carry pieces of zinc (corrugated iron sheeting) that were very heavy, we were not allowed to rest.The soldiers didn't ask you to do this, they would force you, there was no pay.Sometimes if you tried to run away, they would catch you and this is when they would beat you.I was beaten on the back and shoulders with the end of their rifles.When LURD came to this area, I decided it was better to join them and escape the abuse.[14]

Seventeen-year-old, Eric G. stated that he joined the LURD:

After government militias beat and slapped me and held me in dirty water.On July 6, seven militia men came to my house, they tied my elbows behind my back and beat me.They raped my mother and two sisters in front of me.My youngest sister is sixteen years old.The seven of them took turns with them and I was forced to watch.So, I had to go and fight them to revenge my mother and sisters.[15]

Jimmy D. joined the LURD following abuse at the Duala market on Bushrod Island, on the outskirts of Monrovia:

The reason I joined LURD is because of police abuse.I was selling bread at the market, trying to make some money to have something to eat and survive.A policeman came up to me, threw all my bread in the water and said I should go away.I was later beaten for that.When the fighters came to our area, I joined with them.[16]

In one case, the abuses by government forces had the opposite effect.James. T. explained:

Why did I join the government forces?To end the abuse against me and my family.Government militia members would beat my uncle and force him to carry cooking oil long distances.Myself, I was made to tote large bags of cassava to distant military positions.Finally, I decided I couldn't take the abuse and forced labor anymore.Better to join them, so they would not continue to disturb my people.I joined in March 2003.I was fifteen years old.[17]

In June and July 2003, LURD attacked Monrovia three times before a previously negotiated ceasefire was finally enforced by regional troops sent by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).In the three assaults, locally described as World Wars I, II and III, over 2,000 civilians in Monrovia were killed by indiscriminate shelling and gunfire.[18]During these offensives, children from Bushrod Island joined LURD both as fighters and helpers, often to secure needed food for their families.

Samson T., a former child soldier of Taylor's National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), joined LURD in July after the second attack on Monrovia, in part due to growing hunger.Because of his past fighting experience, he was immediately handed a gun. Through his status as a LURD fighter, he was able to secure food and supplies for himself and his relatives.[19]

After LURD captured the strategic port at Bushrod Island, it looted food and supplies and distributed them to the civilian population.With access to food supplies, LURD's treatment of civilians on Bushrod Island was considerably better than in many other areas of Liberia.Sixteen year old Francis R. described himself as a LURD civilian and was charged with delivering food."I was sympathetic to LURD because they were protecting us, they gave us food and helped us out.So my job during World War III was to carry food that was distributed at the port back to my people here."[20]

Matthew T. fled Bushrod Island during the first assault on Monrovia (World War I), but during the next two attacks, stayed behind and like, Francis R., helped run errands and deliver food but did not fight.As he explained:

I never fought, why kill innocent people?Some boys did join LURD, tempted by material things. Others opted to join for revenge, they had been abused by the militias or the police.LURD would promise them cars, money or mattresses.But in the end, they got nothing at all but death.Really, I saw children as young as ten dying on both sides.Some were fighting just to find some daily bread.[21]

Government Forces

Charles Taylor's NPFL used child soldiers extensively in groups known as Small Boys Units (SBUs) in the 1990s.Following a demobilization program in 1997, many children left the forces, entering official rehabilitation programs or simply abandoning the groups on their own.After his election as president that same year, Taylor relied heavily on militias and paramilitary forces he created to defend his government.When LURD began its uprising in Lofa County in 2000, paramilitary groups like the Anti-Terrorist Unit (ATU) and the Special Security Service (SSS) and militia groups led by Taylor loyalists began actively recruiting men, women and again children to fight.Initially, these groups drew on former fighters of the NPFL including child soldiers but increasingly sought out new and younger recruits.These militia groups also included numerous child combatants from the Sierra Leonean Revolutionary United Front (RUF) which Taylor had supported since its inception in l991.

Many children who fought with the government from 2000 to 2003 were picked up in round-ups on the streets, traveling to and from schools and at their homes.They were trained and transported to Lofa and other counties to fight the initial LURD uprising.A counselor who works with children explained that as the war intensified in 2002, parents in and around Monrovia stopped sending their children to school.While this was in part due to lack of money to pay school fees, parents additionally kept their children at home as children would be picked up on their way to and from school.According to this counselor, by 2003 government forces would come and physically take children from barely functioning schools and place them in the SBUs.In June and July 2003, with the LURD assaults on Monrovia, more children took up arms and became affiliated with the forces to protect themselves and their families and to loot.For some families, children became the only source of income, using their guns to steal food and other household goods.[22]

John J., a former child soldier who fought in the mid-90's, fought again beginning in 2000 with Jungle Lion, a government militia, for three years in Lofa and Bomi counties:

I was living in Monrovia, doing small jobs when I could.One day near the Duala market, I was standing on the side of the road selling goods.Government forces came by in pickup trucks.There was no way you could run away.They picked up six boys and myself there on the road side.We were transported to Bomi and then Lofa County.We were some of the first forces sent to Lofa.[23]

Seventeen-year-old, Charles Q., described his involvement:

Last year, I was still in school and on my way home to Congo town (Monrovia). There were government forces in my neighborhood.They had come in pickup trucks and forced us to go with them to Lofa.That day, I had just left school, put down my books and was outside.They told us, 'we are looking for people to fight', not really asking you, just picking you up.There was no choice.[24]

Taken earlier this year, Morris C. was picked up in a similar raid:

I am from Bomi but my family fled to Bushrod Island a few years ago.I was fifteen when I was caught and made to fight.I was on my way to school around 8:30 in the morning, when I was caught at Point 4 junction. Other children wearing yellow t-shirts with Jungle Fighter written on the back forced us at gunpoint into the trucks.They said I had to join them and fight to protect Monrovia.[25]

Children were also regularly recruited in government raids on the displaced camps near Monrovia in 2002 and 2003.Parents soon learned to keep their children inside when the government forces visited the camp, since they regularly rounded up adults and boys to fight. As one mother told Human Rights Watch, "one of my sons was taken away from the camp by government militias before World War II. He was sixteen years old. At that time they used to run behind the children and carry them away, so if you had children, you'd keep them inside."[26]

Some children fighting with the government militias were tasked with recruiting other children to fight.Often forcibly recruited themselves, they in turn forced other children to join with them.A bodyguard to a commander of the Army Division militia, Allen R. was in an SBU for several years fighting in Lofa and around Monrovia.Forced to fight with the Army division, he received his training at Camp Shefflin along with other boys and young men.During his time in Monrovia "we would go around town in pickup trucks, looking for children to fight.Each militia has their own SBU, which includes boys and girls.SBUs are taught to fight and serve, we carry weapons, go on reconnaissance and do odd jobs. The girls in the SBUs are there to wash clothes, bring water and cook.Older girls are the fighters."[27]

Solomon F., a former child soldier from the 1990's, detailed their recruitment tactics:

How did I get involved in the fighting?I was going to school myself, but after school on my way home, the child soldiers caught me and took me away.I was placed in a SBU and became a deputy commander.SBUs can fight, but their main job is to draw water, clean arms, carry out duties.SBUs are young ones, who don't know about the war, but we catch them and teach them.

I recruited some boys from villages, towns and camps.During raids, I would command the other boys in my unit, 'Catch that one there'.We would pass from house to house until we had over one hundred.We would force them even if they didn't want to come.We would line them up in formation, cut their hair, take off their shirts and slippers (sandals).

We taught them how to stand at attention, salute their commanders, load weapons and clean them.We would take them to the creek, put them underwater, show them how to move through the bush, to lie down, how to fire.The length of training depended on how bad the fighting was at the time, if they were needed right away it could be a week, other times the training could last a month.[28]

Not all children with the government forces were forced to join.Some volunteered to fight, seeing no other alternative to war.Twelve-year-old Patrick F. told Human Rights Watch that when fighting came to Bomi County, he joined because his school was no longer functioning, he had nothing to do and other boys his age bragged about their exploits.Similarly, Frederic J. started with the squad four, marines militia when he was fifteen to make some money for himself.Friends of his, flush from looting, convinced him to take up arms.[29]

In the final months of the war, with LURD attacking Monrovia, more children became affiliated with the fighting forces.Moses P., who had fled with his family three times before arriving in Monrovia saw no other way to survive:

We arrived in the Sinkor area, during World War II; there was no food to eat.The family we stayed with had nothing, we were on our own.I decided to help a general who lived near the Catholic junction.I would draw water and do other jobs to help his staff.I was shown how to use an AK-47 and we would drive around town, stealing goods to bring back to his house.We would also force people into the car, those suspected of supporting LURD, and bring them back to the yard.They were beaten and a few were killed.[30]

Children with MODEL

In early 2003, MODEL split from the LURD and began capturing towns in eastern Liberia, initially operating from bases in western Cte d'Ivoire.MODEL continued the practice initiated by LURD, recruiting children from refugee camps and areas that they had recently captured.As with the LURD and government forces, MODEL forcibly recruited some children, while others volunteered to fight, sometimes in response to previous abuse by government forces.

Fourteen-year-old Thomas N. was a Liberian refugee living in the Cte d'Ivoire.He first fought in that country and later in Liberia in Grand Gedeh and Sinoe counties.After MODEL captured the town of Buchanan in July 2003, he was posted in town as a guard.He told Human Rights Watch that his job was to fire with an AK-47 and to protect his unit.[31]Thomas was only one of dozens of refugee children recruited from the refugee camps and Ivorian border towns by MODEL, which operated with the support of the Ivorian government.

Paul F. left school in 2000 because his family could no longer afford the school fees.Originally from Harper in Maryland County, government fighters forced him to tote loads and cook food for them.He explained that he joined MODEL when they took over the area:

Government troops continually harassed us.They would beat us, they raped my sister, they forced her for loving, and they killed my father-so I joined MODEL to fight back.There were over one hundred boys in the units, some were fighting, but I wasn't chosen for that.I was assigned to a big general, I stayed in his house.I washed his clothes, cleaned, and cooked for him.I was taught to take apart a weapon and put it back together again.[32]

A religious sister active with women's groups in Liberia, interviewed a fifteen year old 'wife' of a MODEL general.According to this sister, the girl became his wife for survival reasons when MODEL took over the territory.Given a full uniform, she is both a fighter in the forces and a wife to the general.As the sister explained, many older girls play such dual roles in the forces, not only in MODEL, but with LURD and the government as well.[33]

On July 26, 2003, MODEL captured the port city of Buchanan from government forces.According to local activists, in the weeks leading up to the attack on Buchanan, children were forcibly recruited from the countryside as MODEL moved into Grand Bassa County.In Buchanan town, civilians fled onto the grounds of a Catholic compound during the fighting for protection.In the following days, MODEL fighters came to the campus on the Catholic compound and forcibly removed boys and young men, pressing them into service.[34]A Human Rights Watch researcher who visited Buchanan in late-August saw several armed children, including girls, guarding a high-level MODEL commander at his base and participating in checkpoint duties on the main road to Monrovia.

In other cases, school age children in and around Buchanan willingly joined MODEL.Some children were former government militia members, others ordinary school kids.Some of the children were ex-fighters and seeing their former comrades in arms again convinced them to join as well.

Buchanan residents explained that MODEL fighters were abusive in the first days of occupation but that subsequent relations with townspeople improved.Particularly feared were the young boy fighters, with orange tinted hair, who would harass civilians, steal, loot, and rape.Many of these young fighters were reported to be Ivorians recruited from across the border and abuses diminished as their numbers later decreased in Buchanan.Local residents also claimed that perhaps as many as 200 girls and young women served with MODEL in Buchanan and that men and boys numbered many more.During a meeting between MODEL commander General Farley and his troops observed by Human Rights Watch researchers in early November, there were several dozen underage boys and girls making up the rank and file.[35]

Roles and Responsibilities of Child Soldiers

The roles and responsibilities of child soldiers within both the opposition and former government ranks were very similar.After completing often arduous training, sometimes for a few days, other times for a month or longer, most children were armed and many served on the front lines.They were often the first to be sent out to fight, occupying dangerous, forward positions.They were also charged with manning road blocks and armed guard duty.Some children interviewed for this report spoke of their fear of death, the killing of other children in fighting, and of those they killed themselves.Others bragged about the killings, proud of their advancement to commander status for their ferocity.Children were also beaten and abused by their superiors and forced to witness abuse and killing.

Robert L. who fought with LURD for one year had two months of training in Bomi County.

There we learned to fire, to take cover and how to kill.We were made to crawl under barbed wire while they were shooting at us, we were forced to advance towards the gun fire.This was to make us brave. . .I was assigned around the Iron Gate area.Sometimes we were made to man checkpoints.Other times we would go out on the front. During the fighting, I was very afraid.I killed many people, I saw friends dying all around me, it was terrible.[36]

Seventeen-year-old Joshua P. from Bomi concurred:

I used to be afraid during the time of the fighting, because of the weapons that they were using to kill people.But on my face, I could never show that I was afraid.There were many people dying, I had to protect myself.[37]

Eric G. from Monrovia described his training with LURD:

There were over one hundred of us doing the training.They gave us a gun, we had to learn to fire.We would crawl over and under barbed wire. We were made to lie down and they would see if you were brave by firing near your body.I was afraid during the training, but I didn't show it on my face.[38]

Twelve-year-old Patrick F. spent one and a half years fighting in a government, SBU.Promoted to commander of the SBU for his bravery, he told Human Rights Watch researchers:

As a commander, I was in charge of nine others, four girls and five boys.We were used mostly for guarding checkpoints but also fighting.I shot my gun many times, I was wounded during World War I, shot in the leg.I was not afraid, when I killed LURD soldiers, I would laugh at them, this is how I got my nickname, 'Laughing and Killing'.[39]

Similarly, Samson T. described his feelings about the war:

I never feared anything.I would laugh at death, even when my friends were killed.Sometimes I would feel bad afterward, about my brothers killed, but by fighting I could bring food to my parents and relatives.[40]

Children described how child soldiers in the SBUs were often the first sent to the front.Charles Q. explained, "There were many boys in the units with government forces, small boys too were fighting with guns.These small ones would be sent to the front first.They were usually around fourteen or fifteen years old but some could be as young as ten."[41]Prince D. also spoke of the widespread use of SBUs."We were many, plenty small boys, from ten, eleven and twelve.You would be sent to the front first.You go and get killed and then the next one takes your place, it never ended."[42]

Punishment for wrongdoings could mean beatings, torture, and death.The children interviewed from LURD and government forces described the internal rules which prohibited abuses against civilians and the punishments that fighters received for harassment.Nevertheless, they themselves were complicit in stealing, looting and abducting civilians.It was unclear whether some acts would be tolerated by some commanders and not others or whether specific ethnic groups could be targeted with impunity.However, widespread abuse against civilians by all warring parties occurred often with the knowledge and encouragement of commanders

In explaining the internal rules for LURD fighters, Robert L. stated:

For punishments, some fighters were killed, some beaten or given other punishment, it depended on what they did wrong and who made the decision.I was caught looting, and had to hold my arms straight (body in upright, push-up position).Whenever I fell from exhaustion, I was beaten and forced to hold my arms straight again.There were strict rules in LURD:for murder or rape, you could be killed; for looting or harassment there were other punishments.[43]

According to one child soldier in the government forces, who served with both the Jungle Fire and Navy command militias, his commander in Jungle Fire would not tolerate stealing and some of his friends were killed for looting.But in Navy command, looting was permitted.He further explained that one commander would routinely beat people, including his men, for no apparent reason and was abusive to the boys working in his unit.[44]

According to sixteen-year-old Luke F.:

If someone made a mistake they would be beaten, the general would order to have the person tied and they were beaten, sometimes by rope, a stick, a piece of rubber or a belt.They would have their arms first tied behind their back and then beaten.Other times you could be dragged through dirty water or whipped.These punishments were for things like, raping, stealing or killing.But any government soldiers we found, they would be killed immediately.[45]

Capture by enemy combatants usually meant gruesome death.In a few cases, children would be taken as prisoners or forced to fight for the other side.Children described the killings of suspected enemy fighters or collaborators or what happened to themselves when they were caught.

Eric G. explained:

I saw government soldiers kill three men, right in front of me.They were made to lie on the ground and shot in the head.They were accused of being rebels, because of the markings on their arms.They were shot on July 9 here in town.[46]

Jimmy D., sixteen years old, said:

We captured this one boy and he fought with us later.He was ambushed in a car together with other government soldiers, near Bopolu.LURD fighters cut the hands and feet off the government fighters and made them get back in the car; the boy was the only one spared.Their car was full of blood.Other boys weren't so lucky.One boy from the government side was caught near the Broadville Bridge; he had been wounded in the leg and unable to retreat.LURD caught him and tied him up attached to a stick.They then cut off his toes, fingers, nose and ears.Then they cut off his private parts and left him to bleed to death.They later threw his body in the river.[47]

Seventeen-year-old Winston W. told us that he was captured by government forces in July together with three other men.He said the three adults were immediately killed; they had their heads cut off with knives, decapitated in front of him.Perhaps because of his younger age, Winston was spared, but "was tied up and severely beaten with rope, with sticks and was punched and kicked.I still have pains from the abuse.I was dragged off and imprisoned and later forced to fight with the government forces."[48]

Prince D. described the killing of enemy combatants: "There is no mercy if the government people catch a LURD person, they cut the head off.The LURD would also kill a government fighter, it was the same on both sides."[49]

Enslavement and Forced Labor of Children

In addition to their responsibilities as fighters, children were subjected to forced labor which included be used as porters, laborers, cooks, cleaners and as spies to perform reconnaissance and infiltrate enemy lines.Some children were assigned to individual commanders as bodyguards and personal assistants.In general, younger children served as helpers while older ones fought, but there were exceptions-some boys and girls as young as nine and ten years old bore arms.The intensity of combat might also determine what role a child played, carrying goods one day and needed for the fighting the next.Finally, children spent some of their time stealing from civilians in part because they were either never paid or paid infrequently.

One boy who joined the government ATU in June 2003, described his duties."I was assigned to a commander and provided security for him.I never fought.We would go around to the executive mansion (house of former president Taylor), various police stations, and houses, and collect ammunition to deliver to the troops."[50]

Another who served with MODEL was also assigned to a commander."I stayed with this general the whole time.I had to wash his clothes, clean his home and cook for him.I was not paid, but was given food and some clothes.When we advanced, I carried his goods and marched behind the lines."[51]

Mark R. from Bomi County directly served a LURD general:

I never fought, I was a bodyguard for a general.Armed with an AK-47, I protected the general and his house to prevent other soldiers from looting him.I also had to sweep and clean, cut the brush and carry goods.This general had a wife, she was seventeen and also a fighter, she was very strong.[52]

Human Rights Watch researchers collected dozens of testimonies from the internally displaced populations who described the widespread looting of their property by fighters from the LURD, MODEL and government forces.Child soldiers were used to rob civilians who would then be forced to porter the stolen property.

Boys and girls interviewed explained that while some fighters were punished for looting, almost everyone was involved in stealing from civilians.Fighters were generally unpaid or paid irregularly and to survive, lived off the civilian population.Arms became the means to procure goods, food and drugs and child soldiers were complicit in the looting.

Joshua P. who served with the LURD last year said:

I never directly fought, I would work behind the lines.There were many people killed, so I had to do what I could to survive.I would just move with the forces, helping them carry looted items.As we advanced, civilians would flee their homes.We would go into the houses and steal whatever we could, bikes, money, radios, mattresses, and many other things.I would have to tote the goods after a raid.[53]

Morris C., who was fifteen during the fighting, described looting in the capital:

They didn't give us money, they didn't give us anything-no food.Sometimes we harassed people for money.We would open stores and take goods.When people came to buy goods, we would take their money then go to buy food in West Point (Monrovia).[54]

Twelve-year-old Patrick F. complained that sometimes militias would have to buy ammunition from government soldiers in the AFL.To purchase rounds, he would loot houses, sell the goods, and then get the money to buy ammunition to fight.[55]

Luke F., who fought with LURD for three years, stated that trade between fighting groups was not uncommon and that he would take rice they had removed from the port and trade it with government fighters for clothes and beer.According to him, such trade took place throughout July at the new bridge in Monrovia during lulls in the fighting.[56]

Children interviewed for this report reported that child soldiers with LURD and MODEL were never paid and relied solely on stealing to survive.Boys who fought in the government militias told us that they were occasionally paid, albeit sporadically, but that by 2003 pay was no longer issued.As explained by boys in the government SBUs, salary was linked to active combat, so they would receive money only when they fought.This served as incentive for boys to continue to go back to the front and fight.Children in the SBUs however, complained that the pay was insufficient and was not enough to cover their basic needs.

One boy in the Marine's militia told us he received 300 Liberian dollars (approximately U.S. $7) each time he went to the front.Another who served in Force Fire, a government militia, told us he got 200 Liberian dollars (approximately U.S. $5) for fighting and a bit more when sent on mission.He explained that mission duty was spying on the enemy and was extremely dangerous as you risked being caught and killed.For such duty, he would receive additional pay.[57]

Life with the Forces

Almost every child interviewed for this report had a fighting name, whether or not they were actual combatants.These names often signified particular characteristics of the children or their actions in the fighting.One counselor who works with children in Monrovia suggested that such a practice helped keep children in control as they would forget about their old lives and families.He gave the example of 'Mother's Blessing', a name given by one commander to a boy soldier.The commander had told the child that his mother was killed in the fighting and that she blessed him to go fight against the government troops.Later this same boy found out his mother was still alive.[58]

Other names explained to researchers were:'Laughing and Killing' because the boy soldier would laugh as he killed enemy fighters; 'Disgruntled' because the child soldier was not satisfied with the fighting; 'Captain No Mercy' because the officer would kill if someone disobeyed orders; and 'Walking Stick' because this child was made to walk directly behind his commander.

Children also were given names describing their acts of brutality towards other children and adults.Some boys and girls had names which indicated what they would do to captured civilians, including names like 'Castrator', 'Ball Crusher', 'Nut Bag Mechanic', and 'Bush Lover'.Some girls also had names such as 'Iron Panty' describing their genitalia either because they refused to have sex or because they were believed to engage in numerous sexual activities.Finally other names might describe punishment-one child was named 'Dirty Water' because he was made to bathe in a hole full of waste for committing an infraction.[59]

Children were rarely given military uniforms to wear, but were issued T-shirts which named their fighting groups and sometimes their fighting slogan.The exception was MODEL who had some uniforms from the former Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) but not all MODEL fighters were issued fatigues and like LURD and government forces, most child soldiers in MODEL wore T-shirts. In addition, some children were also involved in units like the 'Buck Naked Unit,' where fighters went into combat naked in order to terrorize opponents and civilians. A female commander with LURD also described how her unit would enter combat clad only in undergarments because they believed this appearance would both strengthen their magical protection and intimidate enemies.

Children serving with the government forces were usually issued yellow T-shirts, but other colors used were green, red or black.According to the children, the name of the unit, such as Jungle Lion or Jungle Fire, would be written on the front, and the division on the back.Arms and weapons were often distributed at the same time as T-shirts.Children fought with RPGs, AK-47s, submachine guns and what they described as '60's, automatic weapons where the ammunition belts would be worn wrapped around the torso.[60]

Boys and girls in LURD described similar weaponry as was used by the government forces but some were also responsible for loading and firing mortars.T-shirts given to children were emblazoned with LURD forces and on the back slogans, such as 'no dog, no rest' or 'no monkey'.According to several of the fighters, these were derogatory statements towards Charles Taylor and his government.Samson T. described the significance:

'No monkey' this was the name that we gave to the forces of Taylor, we wanted him out and so this was to say 'go away'.For us, the LURD, they called us 'no baboon.'The reason for this is because some of us wear black like baboons.Also, the baboon is a strong animal and can fight good just like LURD.[61]

Hairstyle also played a role in unit identification.Some groups had particular hairstyles and would prohibit the cutting of hair.For example, in certain units of Jungle Lion militia, part of the government forces, recruits were not allowed to cut their hair and small braids were fashionable.In some squads of MODEL, hair was colored orange and these children were particularly feared for their atrocities committed against civilians.Some children who served with LURD and government forces told us that when they were taken, their heads were shaved and this formed part of their initiation process.

Children were also initiated into their units through scarification and were given charms and amulets for protection.The practice of initiation is rooted in Liberian culture as in many parts of Liberia, boys and girls become accepted adults in society by undergoing secret initiations.Some analysts have noted that fighting forces in Liberia have co-opted traditional rituals for their fighters for express purposes.Such initiation provides them with a sense of prestige as adults but also enhances a sense of loyalty to their fighting groups instead of to their society and community.[62]

Boys who spoke with Human Rights Watch researchers were reticent to speak of the exact practices that made up initiation, but would display the scars on their bodies and the charms they wore, describing the magic involved.One fighter from LURD explained, "These marks on my chest, they were put there to make me safe from bullets.This way, bullets would bounce off me.Once they were put there, I felt fine."[63] Another fighter from government forces described his scars, "For protection, they would put marks, three or four slashes, on your arms and legs.Then they would rub gun powder into the marks or use a special leaf.This was done so that the bullets wouldn't get you, it really worked."[64]

Some children did not display visible scars, but carried rings and charms.Seventeen-year-old Isaac T. explained:"During the fighting, I was given a charm to wear around my neck, this was from a healer.In my dialect it is called a bang, this would protect me from bullets.It really worked, not against the shells but against the bullets."[65]According to the children, charms could not be worn when having sexual relations or in other situations because then the magic would not work and you risked being killed.[66]

Children were additionally supplied with drugs such as opiates and marijuana, as well as tablets that they were not always able to identify.While many voluntarily smoke and drank and actively sought out liquor, the drugs were often supplied by their commanders.

According to Samson T. from the LURD, "They would give you medicine to eat and drink, the medicine was for protection.If a bullet hit you, it would bounce right off.After I took that medicine, it made me feel bad, it changed my heart.I always took that medicine, every time I went to the front.The commanders would pass it out to us."[67]

David V. explained that within the government forces, "They give you 'ten-ten' in a cap.These are tablets.Once you're on the drugs, even if you are wounded, you don't feel anything."[68]

Twelve-year-old Patrick F. explained how they obtained stimulants:

For alcohol, we would go to the stores and take whatever we could find.We would smoke a lot of opium or marijuana, some people would sell the drugs to us, other times the commanders would come and hand it out. As a deputy commander, I was doing a lot of drugs, smoking a lot of marijuana, but now that the war has ended, I decided to stop.[69]

Solomon F. told Human Rights Watch:

We give people protection-zeke (the rope). Sometimes the medicine, it is in the food, to make you brave and strong. The Zo (senior religious figure) is in charge of protection. Sometimes we cut you with a razor blade and put medicine inside and then nothing can happen to you.We smoke grass, cigarettes, dugee (tablets), cokis (mashed tablets in a powder). It all makes you brave to go on the front. The commanders give it out. When you take the tablets you can't sleep, it makes you hot in your body. Anytime you go on the frontline, they give it to you. Just got to do something to be strong because you don't want the feeling of killing someone. You need the drugs to give you the strength to kill.[70]

Girls in the Forces

Girls served with all three groups in the war as both fighters and helpers although in lesser numbers than boys.Liberian nongovernmental organization employees who work with children believe that more girls were used in the last four years of warfare than in years past but that their exact numbers are unknown.Typically older girls and young women were fighters who served in separate units, while younger girls served as cooks, domestics, porters and cleaners.However, there were cases where young girls fought as well.Some girls were attached to units for short periods and escaped or were released, while others fought for years with the groups.

In addition to the many abuses committed against child soldiers, girls were routinely raped and sexually assaulted.Many were raped at the time of recruitment and continued to be sexually abused during their time with the forces.Collectively known as "wives" whether or not they were attached to a soldier, young girls were often assigned to commanders and provided domestic services to them.Older girls and young women were particularly fierce fighters, commanding respect from their male peers.Some of these women were able to eventually protect themselves from sexual assault but would capture other girls to provide sexual services to boys and men.

Ellen S. a commander of the girls, described her time with LURD:

When LURD came here, we were caught, lots of girls, and were carried back to Bomi.After training, I became a commander.There were thirty 'wives' in my group; only two died, we were strong fighters.These 'wives' were big girls, the youngest ones perhaps fifteen years old.The young girls, they don't get guns, they were behind us.They tote loads and are security for us.

We would wear t-shirts that were either yellow or brown and said LURD forces.My gun was a '60' that was an automatic weapon and I wore the ammunition around my chest.We would get no payment for fighting, when we attacked somewhere, we busted people's places and would eat.When we captured an enemy, if my heart was there, I would bring them to the base for training.But if my heart was bad lucky, then I would kill them right there.[71]

Dorothy M., who first fought with the government, later became a LURD fighter told us:

I started fighting with the government troops when I was fifteen.I was a very good fighter. Last year, I was captured by the LURD forces during battle.They asked me to join them so I accepted.I fought in all three world wars in Monrovia and was never wounded.[72]

Boy soldiers who commented on their female colleagues, admired their fighting ability.According to Jimmy D.:

Plenty girls were trained at the same time, over 200 boys and girls.For the girls, there was the black diamond group, for the boys, it was copper wire.These girls who fight, they are big, sixteen and older, and they fight just like men. They are strong. When the fighting is rough, they move right in because they are juju (magic).They are special.They don't move in on the frontline, but they go ahead when there's a problem, we would retreat and the 'wives' would go forward.[73]

Sexual relations between girl and boy soldiers were permissible, but according to some girls, specific rules dictated these relations.Ellen S. explained that, "No woman can love two soldier men and a woman can't love to your friends' boyfriend.If you break these rules, we beat you and discipline you."She further told us that some older girl fighters could not be forced to have sex but that, "if you want some love, you can get it, but me, I was a strong fighter and stayed alone.The fighters couldn't force us.When we attack, we usually captured girls for them.We would get plenty children for them.I captured two girls who are now in Bomi hills."

While some older girls were able to protect themselves, many more were victims of rape and sexual assault.Forced to join the fighting groups and subjected to forced labor, they were sexually enslaved and some are survivors of multiple gang rapes.

Sixteen-year-old Evelyn N. told her story:

In 2001, I was captured in Lofa County by government forces.The forces beat me, they held me and kept me in the bush.I was tied with my arms kept still and was raped there. I was fourteen years old.

I was taken from home, it was during the day.Plenty of armed men came into the house, government forces, and dragged me out in the bushes.After the rape, I was taken to a military base not far from Voinjama in Lofa County.I was used in the fighting to carry medicine.During the fighting, I would carry medicine on my head and was not allowed to talk.I had to stand very still.

I had to do a lot of work for the soldiers, sweeping, washing, cleaning.During this time, I felt really bad.I was afraid.I wanted to go home, but was made to stay with the soldiers.I spent one year and two months with them before I got sick and was sent away.

The soldiers were terrible, they would kill civilians plenty. They accused them of not supporting them and helping the enemy.We would steal clothes, food, money whatever we could find from civilians. Treatment for women was worse than for men.They would tie up women, beat them and rape them.My auntie, nine soldiers raped her right in front of me, she is very sick now.

For girls in our unit, there were many.Only ten of us would go to the front, the others stayed behind and did chores, collected food and fetched water.These nine others were strong fighters and all had 'husbands' among the male fighters, other fighters would take the girls at the base for loving.[74]

Clementine P. was fifteen when abducted by LURD fighters.A survivor of multiple rapes, she was severely injured when forced to abort her unborn child.Emaciated and sick, a portion of her intestine is protruding through her abdomen wall although she has received some medical treatment.

My Ma and Pa are dead, I have no one to help.When the rebels came, I was small, they forced me to go with them.I got pregnant from the fighters.When the time came for birth, the baby died.Four or five of the boys pushed on my stomach to force me to get rid of the baby, my stomach now is broken.[75]

One of the more severe cases, the plight of Clementine is nevertheless shared by the thousands of girls and women who are survivors of brutal rape and sexual assault by the fighting forces.For girls who served with the fighters, medical treatment with screening for sexually transmitted infections and diseases including HIV needs to be included as part of the demobilization process.The programs should also emphasize psychological counseling or other appropriate psychological support for all girls.Continued medical services in their communities will be needed both for themselves, their children where applicable, and for other girls who may not wish to be identified as fighters in the formal demobilization programs.

Current Status of Child Soldiers

Many of the children who fought with the armed forces in and around Monrovia have been released or they themselves have simply abandoned their groups.Some have returned to their families; many more are languishing on the streets in the capital and other towns or in internally displaced camps.Children who spoke with Human Rights Watch investigators are waiting for demobilization programs to begin and eventual relocation to their families and communities.Some have received limited humanitarian assistance in the camps, but the majority are not currently assisted.

Other children are still involved with the fighting forces despite a commitment in the Ghana Peace Agreement to release all abductees.[76]Displaced persons from Bong County described child soldiers with government militias based in Sanyoie continuing to loot and steal from the local population.Underage fighters still make up the rank and file of MODEL in counties under their control and were involved in active combat during an offensive in Nimba County in November 2003.In a visit to Tubmanburg in October, boys with the LURD were visibly manning checkpoints on the road between Monrovia and Bomi.One young guard told researchers he was eleven years old and had been with LURD for two years.[77]

A demobilization program, which includes provisions for child soldiers, began on December 8 but was soon postponed until January 20 due to the overwhelming numbers of fighters who presented themselves for the program, lack of advance information on the benefits included and a general un-preparedness by U.N. officials.The successful demobilization of all forces is contingent on countrywide deployment of U.N. peacekeepers.At the time of writing, their numbers reached just under 7,000 of an intended size of 15,000 peacekeepers and their geographic scope was just beginning to expand beyond the greater Monrovia area.The continued abuse of children in the fighting forces underscores the urgency of U.N. deployment; children will continue to suffer from violations described above until the peacekeepers reach all areas of the country and demobilization can begin.

The continued delay in programs also heightens the risk that some children will be recruited to fight in neighboring countries.A former child soldier living in a displaced persons camp had already been approached by his commander to go to another West African country to continue fighting.Although he refused, he stressed that with limited options available to him, such an offer was tempting.[78]Similarly, in Buchanan, some MODEL fighters may have already been sent back to Cte d'Ivoire to assist in that conflict and there is concern that as the war dies down in Liberia, children will fight in other West African states.[79]

Official Response

Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, officials from the fighting groups continue to deny their recruitment and use of child soldiers.In a June 2003 statement, LURD pledged to end the recruitment of child soldiers and demobilize those in their ranks.The declaration was not followed through with visible action on the ground.

Human Rights Watch researchers met with LURD Chairman Sekou Conneh in October during a visit to Tubmanburg.According to the chairman, "As for child soldiers, we have been at war a long time, some of them took up arms.But there was no training, no recruitment of any child.Some volunteered to help us with the arms, but they were not trained to fight with us, they were not given weapons by us.Some of these children would follow our soldiers, but we sent them away."[80]

In an interview in September, Defense Minister Daniel Chea also denied the government's use of child soldiers."We have no child soldiers except in one or two cases where local commanders have received young volunteers eager to defend their country.We have a strict policy against using child soldiers and we follow it."[81]

From the testimonies of dozens of children interviewed for this report as well as the visible use of children at checkpoints in the country, such denials do not reflect the reality that children were actively and forcibly conscripted in the fighting in Liberia.The children themselves were able to give credible testimonies about the use and recruitment of child soldiers by many of the top commanders in the fighting forces, despite international law prohibiting their use.Some of these same commanders presently hold key positions in the national transitional government of Liberia, complicating future questions of accountability for their violations against children.

Legal Standards

The government of Liberia, LURD and MODEL are all in violation of international standards that prohibit the use of children as soldiers.Further, Liberia is a party to the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, which together with the Convention on the Rights of the Child, obligates states to provide for the protection, care, and recovery of child victims of conflict, including child soldiers.Finally, Liberia has recently ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which stipulates that states shall make primary education compulsory and free to all.

Liberia acceded to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 in 1954 and to Protocol II in 1988 which together make up the body of international humanitarian law.The Conventions accord special protection to children in armed conflict.Protocol II to the Geneva Convention forbids the use of child soldiers under the age of fifteen in internal armed conflict.[82]This Protocol is binding on state parties and armed opposition groups as well.Government forces, LURD and MODEL are all in violation of their obligations under the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol II.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child also forbids the participation of children under fifteen years of age in hostilities.Article 38 of the convention prohibits the recruitment of children under the age of fifteen while Article 39 obliges that state parties take appropriate measures, "to promote physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration of a child victim of. . .armed conflicts."[83]

Since the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989, other international standards have been adopted that strengthen protections for children affected by armed conflict.These standards reflect a growing international awareness that children under the age of eighteen should not participate in armed conflict.Human Rights Watch takes the position that no child under the age of eighteen should be recruited-either voluntarily or forcibly-into any armed forces or groups, or participate in hostilities.

In the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, states pledge to take all necessary measures to ensure that no child takes part in hostilities and to refrain from recruiting children.The charter defines a child as every human being below the age of eighteen years.Liberia signed and ratified the charter in 1990.It further states that "Parties. . .shall take all feasible measures to ensure the care and protection of children who are affected by armed conflicts."[84]

The United Nations General Assembly adopted an Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict in May 2000.Although Liberia has yet to ratify the protocol, like the African Charter, it raises the standards set in the Convention on the Rights of the Child by establishing eighteen as the minimum age for any conscription or forced recruitment.It further calls on armed groups distinct from state forces not to recruit or use in hostilities persons under the age of eighteen and on other state parties to assist with rehabilitation where possible.Human Rights Watch urges the new Liberian Government to sign and ratify this important protocol.

In October 2003, Liberia ratified the Statute for the International Criminal Court.The statue defines the recruitment or use of children under fifteen as a war crime whether carried out by members of the government or non-governmental forces.As late as November 2003, children under the age of fifteen were still active in some fighting units of MODEL, LURD and government forces.

Also in October 2003, Liberia ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.Together with the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child and the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child, Liberia has recognized the right of the child to the highest attainable standard of education.The new government should prioritize education, both for child soldiers and all children affected by the conflict, to ensure its compliance with its recognition to achieve free and compulsory primary education.[85]

The Future for Child Soldiers in Liberia

As previously noted, plans to begin a comprehensive demobilization program were postponed following problems at the initial demobilization site which opened in Monrovia on December 8, 2003.At the time of writing, the demobilization program is scheduled to re-open on January 20, 2004 in Monrovia, with other sites to open in the countryside contingent upon UNMIL troops reaching full strength and deploying throughout Liberia.

Child soldiers are to benefit from demobilization plans; they will be separated from adults within a 72-hour period of arriving at the sites and will receive benefits as former combatants.According to UNICEF staff working with the Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation and Reintegration (DDRR) Program, children will pass through one of three demobilization sites in staggered periods from which they will proceed to established interim care centers.The centers are envisioned to provide space for children to distance themselves from their military past and to prepare for eventual reintegration into their home communities.Family tracing, counseling, medical care, and skills training are planned for the care centers provided by national and international organizations.Further support is to be provided to the children upon placement in their home communities, from six weeks to three months later.[86]

Demobilization programs for children have been tried before in Liberia with limited success, in part due to the resumption of conflict which frustrated efforts at longer term rehabilitation. In a formal DDRR program that was established in 1997, fewer than one third of the estimated 15,000 children who had fought entered the program.Of these, only 78 were girls despite evidence that their numbers were considerably greater.[87]

Agencies working with children in Monrovia are determined to improve on past attempts, drawing on lessons learned earlier in Liberia and from DDRR programs in neighboring Sierra Leone.The large presence of U.N. peacekeepers, currently deployed in the country for a projected two-year mission, is expected to create sufficient stability to complete community rehabilitation and reintegration.Admitting children with or without their commanders (children presented by their commanders has been a pre-requisite in past programs for admittance) and immediately separating children to interim care centers is expected to yield better results in terms of numbers and quality of programming.[88]

Child care specialists and counselors who worked with previous programs remain concerned about two principal areas:the inclusion of girls and the longer term reintegration of children.In past programs, few girls benefited from the DDRR process despite the fact that many had been forced to join the fighting forces and were at the end of the war, separated from their families.They were either unaware of the program's existence or reluctant to identify themselves as fighters.In many cases, this left them with no other alternative than to remain with the commander or combatant who had abducted them in the first place. In a UNICEF report on past DDRR experiences in Liberia, recommendations for future programs include increased efforts to reach out to girls and to inform and include them in the process.[89]While more attention to girls in the DDRR process may increase their numbers in the program, many girls, especially younger ones, may fear negative stigmatization and may not want to be involved.Some specialists believe the only way to reach these girls is outside the formal DDRR program, through projects within their home communities where they can be assisted.In addition, working with all children affected by war in communities helps to diminish the perception that children who took up arms are being privileged or rewarded for their behavior.[90]