WHAT KABILA IS HIDING

Civilian Killings and Impunity in Congo

I. SUMMARY

The Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) and the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (ADFL) carried out massive killings of civilian refugees and other violations of basic principles of international humanitarian law during attacks on refugee camps in the former Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) that began in late 1996, and in the ensuing seven months as war spread across the country. The war pitted the ADFL, used here to mean all forces under the nominal command of Laurent-Desiré Kabila,[1] with important backing from Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, Angola and other neighboring states, against a coalition of then President Mobutu Sese Seko's Zairian Armed Forces (FAZ), former Rwandan Armed Forces (ex-FAR), Rwandan Interahamwe militia, and mercenaries. In addition to overthrowing former Zairian President Mobutu, the RPA and ADFL sought to disperse the refugee camps in Eastern Zaire, home to hundreds of thousands of civilian refugees as well as the ex-FAR and Interahamwe. Since the beginning of the war in the former Zaire gross violations of international humanitarian law have been committed by all parties to the conflict.

The nature and scale of abuses by different armed parties during the war varied significantly. The FAZ, ill-equipped and poorly motivated to combat the ADFL, were responsible along with their mercenary allies for countless acts of looting, destruction, and rape, in addition to indiscriminate bombings of Congolese populations resulting in numerous civilian casualties. Prior to the war, the FAZ, Interahamwe and local militia had carried out attacks on civilian populations in the east, as part of a national intimidation campaign against ethnic Tutsi Congolese.[2] The ex-FAR and Interahamwe militia supported their combat with and flight from the ADFL and its allies by widespread theft from Congolese communities and using civilian refugees as a shield. Ex-FAR and armed militia who had fled Rwanda in the wake of the genocide were responsible for sporadic killings of Congolese and reportedly some civilian refugees. Members of the ADFL military, in particular its Kinyarwanda and Kiswahili-speaking elements, regular troops of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), and their allies were responsible for large-scale killings of civilian refugees from Rwanda throughout their military advance across the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo). One Rwandan officer who had been in charge of troops at several massacre sights in Congo commented, "It's so easy to kill someone; you just go-[pointing his finger like a pistol]-and it's finished."

These killings represent the latest in a cycle of massive violations of international humanitarian and human rights law in the Great Lakes Region in which impunity for the perpetrators has been the rule. Human Rights Watch/International Federation of Human Rights Leagues (FIDH) will soon publish a major account of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, including precursor events and the entirely inadequate response of the international community.

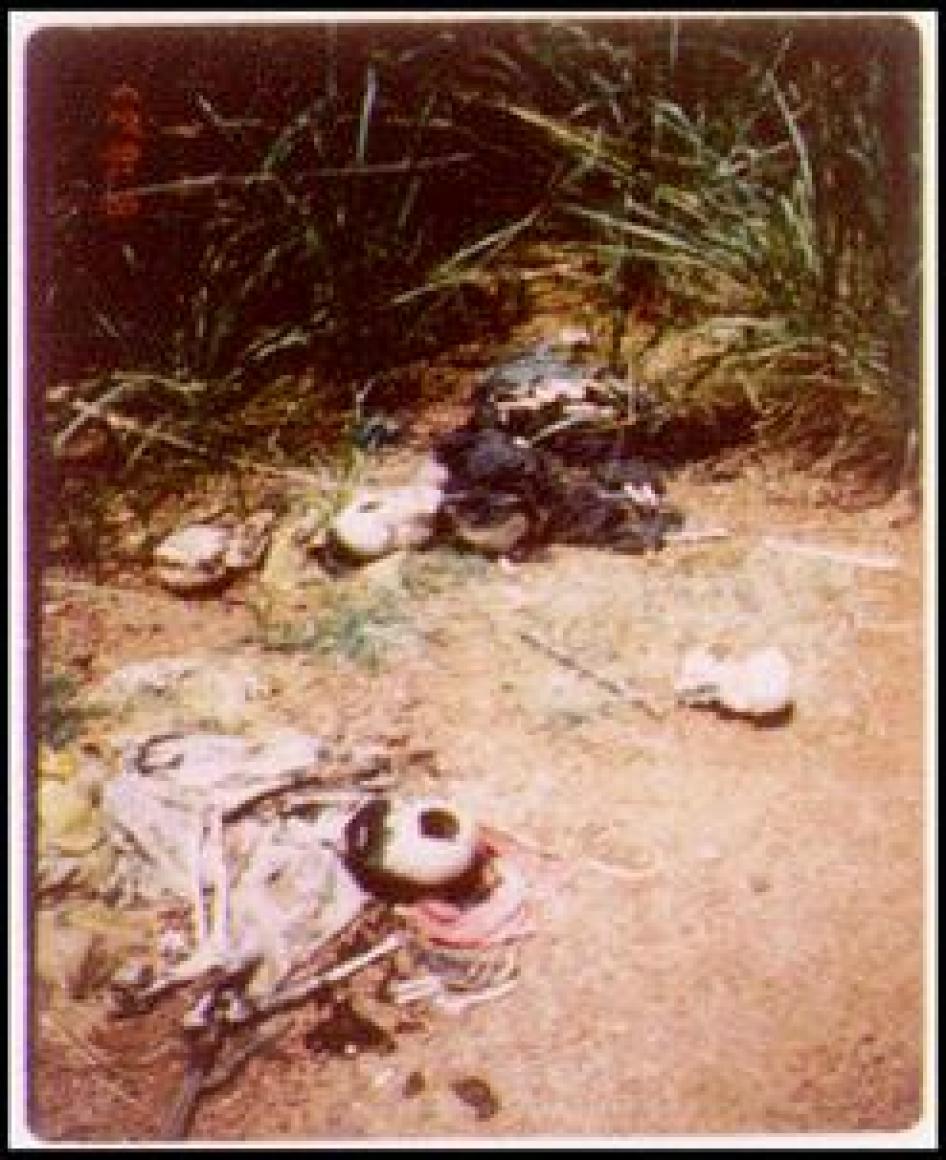

Human Rights Watch/FIDH interviewed Congolese, refugees, international humanitarian workers, and long-time foreign residents in several provinces of Congo and the subregion during a six-week mission. Human Rights Watch/FIDH visited an eighty-kilometer stretch of road in one region of Congo, far from areas where combat took place, along which civilian refugees were slaughtered by members of the ADFL and RPA. In this area, Human Rights Watch/FIDH photographed mass grave sites of refugees and areas of road still littered with their decomposed bodies, among which the remains of women and children were clearly identifiable. Many of the skulls seen and photographed contained holes or were fractured, suggesting blows with a heavy object. The testimony of eyewitnesses describing how certain refugees were killed corroborated with physical evidence on the site, such as smashed skulls or other physical trauma. The refugees in this particular area were killed largely with machetes and knives by Kinyarwanda and Kiswahili-speaking members of the ADFL and members of the RPA. Prior to the arrival of the ADFL and RPA to this area, the ex-FAR and armed Rwandan exiles operating with them were responsible for widespread theft, destruction and reportedly some killings of Congolese civilians.

The killings and violations of international humanitarian law in this area represent a cross-section of events that occurred throughout Congo. Thousands of refugees, often young men, the sick, and those too weak to flee were killed by soldiers of the ADFL and RPA as they advanced across Congo. Thousands of other civilian refugees were deliberately cut off from humanitarian assistance, resulting in thousands of deaths due to starvation, dehydration, and disease. Many of the remains of refugees that were killed by the ADFL or the RPA have been exhumed, burned, or otherwise disposed of out of sight of potential witnesses. Congolese have been intimidated to keep them from providing information about the killings through arrests, beatings, and killings of those who have dared to speak out. Killings of civilians from several ethnic groups continue in Congo, most notably in the east where the unresolved issues of land rights, citizenship, and customary power have aggravated violence between remnants of the ex-FAR, Mobutu's former Army (ex-FAZ), and other ethnic-based Congolese militia, all aligned against the troops of the Rwandan Patriotic Army still garrisoning the region.

Some members of the international community, including the United States, were aware of Rwanda's intention to attack refugee camps in Eastern Zaire well in advance and either supported the idea, were unable to propose alternative solutions to the challenges posed by the camps, or did nothing to prevent it. After months of denial, Rwandan Vice-President Paul Kagame in early July 1997, claimed responsibility for planning and leading the invasion of the former Zaire and explained that his objective of dispersing refugees and destroying the ex-FAR and Interahamwe had been made known to officials of the United Nations and the United States among other members of the international community. The United States provided key political support to the Rwandan authorities throughout the military campaign in Congo and up to the present; knowledgeable witnesses have claimed that U.S. military provided training and assistance to the RPA on Congolese territory.

In April 1997, upon the recommendation of the United Nations special rapporteur on Zaire, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights requested that an investigation be conducted into mass killings and other gross violations of human rights in Congo. Since then, the Congolese government has demanded changes in the mandate of the U.N. investigation and repeatedly stalled the investigation. International support for the investigation has fluctuated: negotiations between Kabila and U.S. Ambassador Bill Richardson and U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan led to a change in the head of the U.N. mission and its mandate; as of this writing, however, the United Nations, European Union and United States have taken a firmer stand on the investigation taking place, insisting that international aid be conditioned on cooperation with the U.N. mission. Key members of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) have been firm in their support of Kabila as he defies the U.N. investigation.

The Congolese and Rwandan governments, along with the international community, should take all measures necessary to put an end to impunity in the region. This includes public recognition by all governments concerned that massacres of civilians took place during the armed conflict in Congo, as well as insisting that war criminals are investigated and held accountable for their acts. In parallel, efforts should be reinforced to bring the perpetrators of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda to justice. The international community should encourage the growth of Congolese organizations of civil society and provide aid in key areas such as health and education through nongovernmental organizations, but condition its other non-humanitarian aid on full compliance and cooperation with the United Nations Secretary-General's Investigative Mission and respect for international human rights norms. International support for national institutions of justice should be an urgent priority once the Congolese government has fully cooperated with the U.N. Investigative Mission.

II. RECOMMENDATIONS

To the Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo

- Suspend and investigate members of the ADFL suspected of involvement in civilian massacres and other violations of humanitarian law, and hold individuals accountable for such abuses; members of the ADFL who obstructed humanitarian assistance to civilian populations should be subject to investigation, and prosecution where appropriate. ADFL officers and troops under investigation should be suspended from positions of authority for the duration of the investigation.

- Publicly denounce deliberate killings of civilians in Congo by all parties, including foreign military from Rwanda and other neighboring states, during the seven-month war that brought the ADFL to power, as well as ongoing killings. Insist that those responsible are immediately withdrawn from the field and subject to investigation, and prosecution where appropriate, either in Congo or their home country.

- Protect refugees, internally displaced, and other civilian populations from abuses committed by members of the former Rwandan Army (the ex-FAR, Forces Armées Rwandaises), Interahamwe and other armed militia, and FAZ; in doing so, respect international humanitarian law and take all possible measures to limit civilian and refugee casualties during military operations.

- Cooperate fully with the International Criminal Tribunal in Arusha in bringing those responsible for the 1994 Rwanda genocide to justice.

- Allow the United Nations Secretary-General's Investigative Mission unhampered access to all regions of Congo and ensure its security and independence in accordance with its mandate. Instruct members of the ADFL and other military forces present in Congo to cease the destruction of evidence of civilian massacres and other abuses. Encourage the Congolese population and ADFL military to cooperate with the U.N. mission and ensure the protection of those who provide information.

- Cease its intimidation campaign against potential witnesses of civilian massacres. Investigate human rights abuses committed by ADFL or other military forces on Congolese territory against individuals suspected of collaboration with the U.N. Investigative Mission.

- Guarantee the protection and assistance of refugees on Congolese territory in accordance with international standards, including the right to non-refoulement. Create the conditions necessary for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to provide assistance and protection to refugees remaining in Congo.

- Support the work of Congolese organizations of civil society, especially those involved in the protection and promotion of human rights.

- Establish national institutions to promote the rule of law and respect for human rights, in particular an independent judiciary and a permanent human rights commission.

- Initiate training programs in basic principles of human rights and international humanitarian law for members of the police, army, and judiciary.

To the Government of Rwanda

- Withdraw, suspend from active duty, and investigate Rwandan military suspected of being involved in civilian massacres in Congo, and hold individuals accountable for such abuses; members of the RPA who obstructed humanitarian assistance to civilian populations should be subject to investigation, and prosecution where appropriate.

- Assist the U.N. Investigative Mission in Congo in fulfilling its mission by publicly disclosing the names of officers and Rwandan units deployed in Congo from September 1996 up to the present, as well as all other information relevant to their mandate.

- Denounce deliberate killings of civilian refugees and Congolese civilians during the war that brought the ADFL to power and up to the present.

- Protect and assist refugees upon repatriation to Rwanda. Cooperate fully with the UNHCR in its efforts to protect and assist refugees, in particular by providing access to recent returnees.

To all Members of the International Community, including the United Nations, the European Union and its member states, the United States, and the Organization of African Unity

- Insist that accountability for human rights abuses in Congo and Rwanda not be sacrificed for economic or diplomatic reasons. Members of the ex-FAR and Interahamwe militia, as well as individuals from the ADFL, RPA, and other militaries or mercenaries responsible for massive civilian killings in Rwanda or in Congo should not be granted impunity

- Consider extending the mandate of the International Criminal Tribunal in Arusha to include jurisdiction over war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the war in Congo.

- Make assistance for the Congolese judiciary an urgent priority once the government of Congo fully complies and cooperates with the U.N. Investigative Mission. Insist on the development of the judiciary as an independent institution. Assist the Congolese government in the establishment of other national institutions that will help to promote the rule of law, such as a permanent human rights commission, once full cooperation with the U.N. team takes place.

- Provide immediate aid to the Congolese population via nongovernmental channels for humanitarian relief. Condition the convening of any donor meetings and the granting of non-humanitarian aid, particularly balance of payments support, on full compliance and cooperation with the U.N. Secretary-General's Investigative Mission and respect for human rights. The European Union should lift the suspension of development aid to Congo, as outlined in the Lomé Convention, only upon full compliance and cooperation with the U.N. Secretary-General's Investigative Mission.

- Support Congolese organizations of civil society in their efforts to promote and protect human rights. Encourage the Congolese government to foster the growth of and consult with such organizations.

- Make sufficient human and financial resources available to the UNHCR to enable a process of individual determination of refugee status for Rwandans, Burundians, and other refugees in the subregion. Protection, assistance, and the right to asylum should be provided to those who qualify by the states of the Great Lakes region as well as the international community.

- Assure that ex-FAR, Interahamwe militia, and others implicated in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, as well as these forces and Mobutu's FAZ who have committed war crimes and other humanitarian law violations under the Mobutu government or since the ADFL took power, are pursued wherever they may be and brought to justice.

- The United Nations should continue its human rights investigation in Congo regardless of whether the Kabila government cooperates with the investigation. If access to Congolese territory is impossible, the U.N. should continue the investigation based on sources available outside the country. The U.N. team should also investigate the various levels of responsibility for the crisis, including the failure of the international community to remove armed elements from the camps in eastern Zaire and in permitting them to prepare new combat against Rwanda.

Specific recommendations to the U.S. government

- Publicly acknowledge and denounce deliberate killings of civilians in Congo by the members ADFL, troops of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) and members of other foreign militaries allied with the ADFL, and release all information available regarding these atrocities.

- U.S. Department of Defense and other government agencies should fully disclose the nature of all present and past involvement in training, tactical support, field assistance, or arms shipments to Rwanda or Congo for use by the ADFL or Rwandan, Ugandan or other forces operating in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

- Conduct investigations to determine whether any of the military involved in civilian massacres or other gross violations of international humanitarian law have received training from the U.S. armed forces or other U.S. agencies, either in the region or in the U.S. Make public the identities of any such military and insist on their prosecution where appropriate.

- Immediately suspend any tactical support, field assistance, or arms shipments to Rwanda. The U.S. should conduct a thorough evaluation of the efficacy of U.S. military training to Rwanda in the areas of international humanitarian law, military justice, and other areas pertaining to the respect of human rights. The U.S. should make public its findings of this investigation.

III. BACKGROUND

The Origin of the Refugees

In April 1994, Hutu extremists used the military, administrative and political structures of Rwanda to carry out a genocide against the minority Tutsi and to kill moderate Hutu who were seen as Tutsi collaborators. Soldiers of the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) and members of militia groups known as the Interahamwetook the lead in slaughtering more than 500,000 people.[3]

In July 1994, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a predominantly Tutsi movement, overthrew the genocidal government, against which it had waged war since 1991. Some two million Rwandans then fled to surrounding countries, some because they feared retribution from the RPF, some because they were ordered to follow government leaders into exile. The estimated 1.1 million who ended up in Zaire included both refugees as well as others who were implicated in crimes against humanity in their home country and remained armed, planning to continue the genocide-and their war against the RPF-from adjacent countries. This mixed population settled in camps, the great majority in Zaire and the next largest number in Tanzania, where they were nourished at the expense of the international community. Human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch and the International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH), humanitarian agencies, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and the Rwandan government repeatedly demanded international intervention to separate the refugees, many of them women and children, from the armed elements, former soldiers (ex-FAR) and militia members. Although the U.N. prepared plans for such action, the Security Council rejected them as too expensive and perhaps unworkable.

Administrative officials and military and political leaders responsible for the genocide controlled the camps and with the ex-FAR and militia intimidated many refugees into staying in the camps instead of returning home. Within Rwanda, human rights abuses, particularly killings by soldiers, massive arrests without regard to due process, and the paralysis of the judicial system also discouraged refugees from returning.

Beginning almost immediately after settling in the enormous border-area camps, the ex-FAR and militia reorganized, trained new recruits and bought new arms from abroad. [4] As their incursions into Rwanda increased in number and impact, the government of Rwanda signaled that it would act on its own to end the threat from the camps in Zaire if the international community failed to intervene. In the face of stepped-up infiltration in 1996, a rash of killings of civilians in border areas, and apparently aware of preparations for an invasion, Rwandan leader General Paul Kagame again alerted leaders of the U.S. and perhaps other countries that Rwanda would act if conditions did not change.

Banyarwanda and Banyamulenge

Before the massive influx of Rwandans in 1994, about half of the 3 million people of North-Kivu, in the former Zaire's extreme northeast, were speakers of Kinyarwanda, the language of Rwanda. Known collectively as Banyarwanda, they included about four times as many Hutu as Tutsi.[5] Some had been present before the drawing of colonial boundaries, while others had migrated from Rwanda for economic reasons or as political refugees during the twentieth century, many with official encouragement from the Belgian authorities in the 1930s. In some areas, such as Masisi, the Banyarwanda comprised a large majority of the population.[6]

Of the Banyarwanda in South-Kivu, a group of pastorals on the Itombwe plateau, principally near Mulenge, became known, at least to themselves, as the Banyamulenge (the people of Mulenge hill or forest) during the rebellions against Mobutu in 1964. Most of the Banyamulenge are descendants of Rwandans who fled political repression and population pressure in Rwanda during the 18th and 19th centuries;[7] other Banyarwanda immigrated to the area in more recent times, some fleeing oppression in Rwanda in 1959. Many Banyamulenge came under threat from the rebel forces led by Kabila and others in the 1964 uprisings and sought protection from the Mobutu regime in Kinshasa, while others sided with the rebellion. The term Banyamulenge came to be used widely in Congo to refer to ethnic Tutsi Congolese in general from mid-1996.

The Citizenship Question

The right to Zairian citizenship, recognized for Banyamulenge and Banyarwanda by earlier laws and constitutions, was limited in 1981 to those people who could prove that their ancestors lived in Zaire before 1885. But the 1981 law was not actively enforced and identity cards of Kinyarwanda-speakers were not revoked. Politicians who feared the number of votes represented by Kinyarwanda-speakers in proposed elections stirred up feelings against them among people of neighboring ethnic groups. At the time of the National Conference in 1991,[8] Celestin Anzuluni, a Bembe from South-Kivu, led a move to exclude the Banyamulenge, claiming they were not Zairians but Rwandan immigrants.[9] Banyarwanda from North-Kivu were similarly to be excluded. After this, leaders of other ethnic groups increasingly challenged the rights of Banyamulenge and Banyarwanda generally to Zairian citizenship.

Violence Against Speakers of Kinyarwanda

In 1993, Hunde, Nande, and Nyanga civilian militia known as Mai-Mai and Bangilima, encouraged by government officials and sometimes supported by the Zairian military, attacked Hutu and Tutsi communities in North-Kivu, killing thousands and displacing some 300,000.[10] The arrival in Eastern Zaire of the enormous number of Rwandans in flight in 1994 exacerbated tensions between previously resident Kinyarwanda-speakers and other ethnic groups. The Interahamwe militia and many of the former military and civilian authorities of Rwanda encouraged hatred of Tutsi among adjacent populations. Local ethnic groups which had once viewed Hutu and Tutsi as a common enemy sided increasingly with Hutu, both refugees and local residents, in attacking Tutsi, who were sometimes branded as loyal to the new government of Rwanda. In South-Kivu, Bembe and Rega, encouraged by comments by regional politicians, began to organize militia, following the model of the Interahamwe of Rwanda and the Mai-Mai and Bangilima of North-Kivu.[11]

Feeling increasingly threatened by harassment and arrests and talk of expulsion,[12] numbers of Banyamulenge young men went to Rwanda where they joined or were trained by the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), which also supplied them with weapons. In South-Kivu, others organized their own militia and bought arms during 1995. According to one witness, "The Banyamulenge [even] bought rifles from the Interahamwe [in the refugee camps]. . . . With the crisis in Zaire, the Interahamwe sold their guns."[13]

In early 1996 Interahamwe, Mai-Mai, and Bangilima killed hundreds of Tutsi and drove more than 18,000 from North-Kivu into exile in Rwanda and Uganda.[14]

The Banyamulenge Revolt

In August 1996, Zairian authorities banned MILIMA, a development and human rights nongovernmental (NGO) working among the Banyamulenge, and arrested several prominent Banyamulenge. In early September Zairian authorities said Banyamulenge should leave the country, an order formalized on October 7 by the deputy governor of South-Kivu, Lwasi Ngabo Lwabanji, who ordered all Banyamulenge to leave Zaire within a week.[15]

In early September, Bembe militia, supported by FAZ soldiers, began attacking Banyamulenge villages, killing and raping, and forcing survivors to flee. The Banyamulenge, joined by other groups, rose up against the Zairian government. They later formed a coalition, the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (ADFL), and chose Laurent-Desiré Kabila as spokesman, a post he later transformed into president of the movement. Rwandan, Ugandan and later Angolan troops supported the ADFL and quickly overran the demoralized and poorly disciplined Zairian Armed Forces (FAZ).[16] After a rapid advance from east to west, during which he was generally hailed as a liberator, Kabila proclaimed himself head of the newly declared Democratic Republic of Congo on May 18, 1997.

Attacks on the Camps

As the ADFL forces and their allies began combat against the FAZ they simultaneously attacked the camps sheltering the Rwandans, breaking the control of the former administrative and military authorities. In some camps, the ex-FAR and militia retreated quickly, sometimes after briefly resisting the ADFL advance. The majority of people in the camps, perhaps 600,000 of the 1.1 million estimated to have been in residence in October 1996, returned to Rwanda in November. Of those who returned, many went voluntarily, while others were forced back by the ADFL, fearful of the conditions in Rwanda. A number estimated in the thousands died in the first weeks of the attacks on the camps, caught in crossfire between the ADFL and elements of the ex-FAR, militia and FAZ; killed by the former camp authorities in an effort to prevent their return to Rwanda or to force them to accompany the ex-FAR and militia on their retreat westward; or killed by ADFL and RPA troops. Hundreds of thousands of Rwandans fled westward, some in relatively organized caravans, others in scattered small groups. Tens of thousands of these were armed elements, but the rest were unarmed civilians, many of them women and children.

Many of the civilians who fled to the west were attacked again, some of them repeatedly as they sought safety. In a few cases, ex-FAR and militia used the refugees as human shields or even injured and killed them. But in the vast majority of instances, it was clearly ADFL soldiers and their foreign allies who slaughtered the refugees. In addition, untold thousands died of hunger or disease because ADFL and Zairian authorities denied humanitarian agencies permission to enter their zones to deliver assistance or because the security conditions prevented them from doing their work. Some humanitarian workers testified that ADFL soldiers accompanied them, supposedly to facilitate their work but really to find out where refugees were hidden in order to return later to eliminate them.

The UNHCR states that it helped an additional 234,000 Rwandans return to Rwanda between December 1996 and June 1997 and that it had located an additional 52,600 Rwandans, about half of them in Congo and the other half dispersed in the Central African Republic, Congo (Brazzaville) and Angola by July 1997. According to the refugee agency's figures, an estimated 213,000 Rwandans remain unaccounted for, either dead in the period of violence or hidden in the forests or among the people of Congo.[17]

Controversy continues about the exact number of refugees who perished during the conflict due to massacres, malnutrition, or disease. Kabila's government has effectively denied the U.N. Secretary-General's Investigative Team and other diplomatic missions or human rights organizations access to reported massacre sites and thus has made assessment of the casualties impossible.

The Laws Violated

All parties to the war in Congo, whether rebel or governmental, are bound by international humanitarian law to respect basic norms concerning victims of armed conflict. In particular, regardless of whether a government or an insurgent group, all sides are obliged to apply common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949:

In case of an armed conflict not of an international character occurring in the territory of one of the High Contracting Parties, each Party to the conflict shall be bound to apply, as a minimum, the following provisions:

1.Persons taking no active part in the hostilities, including members of the armed forces who had laid down their arms and those placed hors de combat by sickness, wounds, detention, or any other cause, shall be in all circumstances treated humanely, without any adverse distinction founded on race, colour, religion or faith, sex, birth or wealth, or any other similar criteria.

To this end the following acts are and shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever with respect to the above-mentioned persons:

a)violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture;

b)taking of hostages;

c)outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment;

d)the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

Furthermore, all parties to the conflict in Congo should respect the principles of U.N. General Assembly Resolution 2444, which recognizes the customary law principle obliging all factions of an armed conflict at all times to treat civilians distinctly from combatants. It states that,

the following principles for observance by all government and other authorities responsible for action in armed conflicts:

a)That the right of the parties to a conflict to adopt means of injuring the enemy is not unlimited;

b)That it is prohibited to launch attacks against the civilian populations as such;

c)That distinction must be made at all times between persons taking part in the hostilities and members of the civilian population to the effect that the latter be spared as much as possible.

While the above principles apply to all parties to the war in Congo, additional bodies of international humanitarian and human rights law place further obligations on certain parties to the conflict, notably the government of the former Zaire, the ADFL authorities who succeeded to the international obligations of the former government, the government of Rwanda and other governmental allies of the ADFL.[18]

IV. OVERVIEW OF CIVILIAN KILLINGS FROM OCTOBER 1996 TO AUGUST 1997

The seven-month war between the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (ADFL) and the Zairian Armed Forces (FAZ) was accompanied by gross violations of human rights and international humanitarian law. Killings of both Congolese civilians and refugees continued at the time of this writing. This overview summarizes the general trends of killings in Congo from the outbreak of the war in October 1996 through August 1997.

Most of the killings and other abuses from October 1996 between August 1997 were committed by individuals belonging to three distinct groups: former President Mobutu's FAZ and mercenaries; the former Rwandan Armed Forces (ex-FAR) and militia from the camps; and the ADFL, consisting of both Kabila's troops and military from several neighboring states, including Rwandan, Uganda, Angola, and Burundi. Other armed militia have also reportedly attacked civilians, particularly in recent months in eastern Congo.

The nature and scale of the killings and other violations committed by each of these groups differed significantly.

Human Rights Abuses by the FAZ

Throughout the war that led to the ousting of Mobutu, the Congolese population, refugees, and foreign nationals in Congo were witness to numerous violations of international humanitarian law and other abuses committed by the notoriously ill-trained and poorly supported FAZ. Mobutu's forces perpetrated abuses to sustain their fighting with and retreat from the ADFL, to enrich themselves, and to settle old scores with opponents of the Mobutu regime. These acts included widespread theft, rape, various acts of revenge, destruction of infrastructure, destruction of private and public property, and killings of civilians.

In September 1996 the FAZ, indigenous militia from South-Kivu, and armed elements from the refugee camps carried out attacks against Banyamulenge and other ethnic Tutsi in South-Kivu, resulting in numerous civilian deaths and incidents of rape.[19] This followed a period of several months of intensifying intimidation of Tutsi by military and civilian authorities throughout the country, as authorities claimed that Rwanda and Burundi were arming the Banyamulenge.

Throughout the war, the FAZ exercised a blatant disregard for international humanitarian law. Before fleeing the city of Kindu in February of 1997, the FAZ looted the Kindu General Hospital, depriving patients of medical care and stealing basic medical supplies and equipment including medicine and mattresses in use by patients.[20] In mid-February 1997, the FAZ, in collaboration with Serb and other mercenaries, bombarded several cities in eastern Zaire, including Bukavu, Shabunda, and Walikale, resulting in dozens of civilian deaths and injuries.[21] In early May of 1997, indiscriminate bombardment by the FAZ of the city of Kenge, 180 kilometers east of Kinshasa, resulted in the deaths of approximately 200 civilians, according to the Congolese Red Cross.

With insufficient logistical support from Kinshasa for their military campaign against the ADFL, the FAZ resorted to widespread theft and appropriation. Individual soldiers also looted for their own personal gain and then abandoned their units with no intention of returning to military service. In November 1996 United Nations officials in North-Kivu reported several hundred vehicles lost to looters, predominantly members of the FAZ who had fled the cities of Uvira, Bukavu and Goma.[22] The FAZ developed a pattern of looting just prior to their retreat from cities throughout the country, earning them the title of pillards-fouillards (fleeing looters).

Some abuses committed by the FAZ from September 1996 to May 1997 were acts of revenge against long-standing opponents of the Mobutu regime. While elements of the FAZ frequently participated in indiscriminate rape, beatings, and other cruel, degrading, and inhumane treatment during their retreat, church leaders, members of the political opposition, and leaders of civil society were often singled out for abuse. Churches that lay in the path, or within striking range, of the retreating FAZ were frequently looted by the FAZ; several were intentionally burned.[23] Refugees consistently accused the FAZ of acts of raping and killing refugees, as well as forcing them to assist the FAZ as laborers.[24]

Looting of public and private property, and the destruction of local infrastructure continue to affect the Congolese population today. Many state institutions under the Mobutu regime were in a state of advanced decay, leaving churches and nongovernmental organizations often as sole providers in key sectors such as health and education. This destruction of property and services belonging to churches and nongovernmental organizations deprived the Congolese population to many basic rights including access to health care and education.

Human Rights Abuses by the ex-FAR and Interahamwe Militia

Abuses committed by the ex-FAR and Interahamwemilitia after their flight from the camps of the border area were largely related to strengthening their forces for combat with the ADFL, their retreat, or simply their survival. Throughout their flight across Congo, ex-FAR and Interahamwe intimidated civilian refugees to discourage them from returning to Rwanda, as they had done since the establishment of the refugee camps in 1994. Ex-FAR and militia participated in sporadic killings of Congolese civilians and some refugees.

The ex-FAR, Interahamwe, and civilian refugees participated in widespread theft to sustain themselves. In addition to theft by these former military or armed militia, the presence of tens of thousands of fleeing civilian refugees had a profound impact on Congolese civilian communities. Schools, public buildings, and homes were used for shelter, health centers were emptied of their medical supplies, and crops were looted and destroyed as refugees passed through Congolese cities and villages. The massive loss of property and destruction of infrastructure contributed to the decline of economic activity as well as numerous deficiencies in public services-problems that persist today.

According to corroborated testimony, ex-FAR and armed militia were responsible for at least one large-scale killing of Congolese civilians during their trek across Congo.[25] On or about November 6, 1996, ex-FAR and Interahamwe attacked a convoy of trucks near Burungu, North-Kivu, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of civilians, according to survivors. Congolese from villages in Equateur, Haut-Congo, and North-Kivu told Human Rights Watch/FIDH of sporadic killings of their neighbors by armed Rwandans when food or supplies were withheld or were insufficient.

Other reports describe ex-FAR or armed militia intimidating and at times shooting at civilian refugee populations in attempts to direct their movements throughout their flight from the ADFL. One U.N. official described testimony from civilian refugees with machete wounds near Mbandaka who claimed that the ex-FAR had attacked them, complaining that the civilian refugees had become a burden.[26] UNHCR officials in refugee camps as far west as Congo-Brazzaville stated that intimidation of refugees wishing to return to Rwanda continued in some areas at least until July 1997.[27]

The presence of ex-FAR and Interahamwemilitia in several provinces of Congo remained a security threat as of this writing in September 1997. In the east, ex-FAR and militia have carried out attacks on civilian populations, primarily Tutsi, and continue to use North-Kivu as a rear base for incursions into Rwanda. In the central and western provinces of Congo, some internally displaced villagers still refuse to return to their homes, fearful of theft and violence by ex-FAR, or concerned that attempts by the ADFL to track down and eliminate both refugees and the armed exiles will create security problems for themselves.

Human Rights Abuses Committed by the ADFL

The human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law committed by the ADFL and its allies are remarkably different in their scale, nature and motivation from abuses perpetrated in Congo by the FAZ and ex-FAR. From the beginning of the war up to the present, ADFL troops or their allies, in particular those of Rwandan or of ethnic Tutsi origin, have carried out large-scale killings of civilians, predominantly refugees as well as some Congolese. In addition, the intentional blocking of humanitarian assistance to civilian refugees by ADFL troops is likely to have resulted in thousands of additional deaths.

These killings and the intentional blocking of aid were apparently both in revenge for the 1994 genocide in which Tutsi and moderate Hutu were systematically massacred by ex-FAR and Interahamwe as well as an attempt to weaken their military organization in Congo and their support base of civilian refugees. From mid-1994 up to their dispersal, armed elements in the camps in eastern Congo benefited from aid destined for the civilian refugee population and used the camps as a rear base for incursions into Rwanda.

The presence of Rwandan troops on Congolese territory was confirmed by Rwandan Vice-President Paul Kagame during an early July interview with the Washington Post[28] and again on September 9, 1997 when Kabila publicly thanked Rwanda for its help during the war on an official visit to Kigali.[29] Civilian refugees were often caught in areas of combat between these Rwandan forces and others backing the ADFL as they fought their FAZ and ex-FAR opponents. In addition to deaths due to crossfire, however, refugees describe numerous examples of indiscriminate attacks on refugee camps, including the use of mortars and heavy machine guns in the attacks on the Kibumba refugee camp in North-Kivu.[30],[31] These attacks on camps in eastern Congo marked the beginning of a series of attacks on refugees and temporary camps set up as refugees fled westward into the interior of Congo.

Other killings were more selective: numerous refugees reported being overtaken throughout their trek by military that they recognized as RPA.[32] They described systematic triage of refugees carried out by these troops that resulted in young men, former military or militia, former members of government, and intellectuals being selected for execution. Women and children were often encouraged to return to Rwanda but were occasionally allowed to flee further into the forest. Refugees returning from eastern Congo to Rwanda during the first months of the war were largely women, children, and elderly, who confirmed that male refugees among them had been taken away by the ADFL. As the refugees moved westward and into more remote areas, killings became more indiscriminate and women and children were more often included in massacres.

Testimonies taken in several provinces of Congo as well as in neighboring states concur that the perpetrators of most killings were from an ethnic Tutsi sub-group of ADFL troops, often described by Congolese as "Rwandan", "Ugandan", "Burundian", or "Banyamulenge." Numerous refugees described how, when overtaken by the ADFL or their allies during their flight, they had recognized and had conversations with members of the RPA who were from their home communes in Rwanda. Congolese villagers described numerous incidents in which refugees and members of the RPA recognized and spoke with one another in areas where massacres took place. Many commanding officers in areas where massacres took place, as well as troops under their command, were members of the RPA. Some stated that they had grown up in Rwanda, having left for studies or other reasons.[33]

Languages spoken by perpetrators similarly indicates their origin as primarily Rwandan, eastern Congolese, or Ugandan.[34] Congolese, foreigners in Congo, and refugees consistently described the perpetrators of massacres in several regions or those blocking humanitarian access to refugees as Kinyarwanda speakers. Many witnesses noted the divisions among the ADFL, claiming that the troops of the ADFL who killed were often from Rwanda, some speaking only Kinyarwanda.[35]

Others witnesses stated that the perpetrators spoke Kiswahili as well as Kinyarwanda, sometimes mixed with French or English. This indicates that some of the troops involved in killings were likely to have come from southern Uganda, as well as eastern Congo and Burundi. Many commanding officers and troops in areas where massacres took place were fluent English, Kinyarwanda, and Kiswahili speakers, characteristic of members of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) who invaded Rwanda from southern Uganda in 1990.

Certain military among the ADFL and especially the RPA appeared to be particularly motivated to kill refugees. Kinyarwanda and Kiswahili-speaking ADFL or Rwandan troops repeatedly demonstrated throughout the war a specific intent to hunt down and kill civilian refugees as well as armed exiles from Rwanda. Numerous residents of Mbandaka report that, upon the arrival of the ADFL on May 13, 1997, Kinyarwanda-speaking troops immediately asked "where are the refugees?" and proceeded to seek them out and begin killing.[36] Human Rights Watch/FIDH received similar reports from towns between Kisangani and Mbandaka, where the first order of business for the ADFL upon arrival in a village was to eliminate refugees.[37]

Congolese development workers described an incident during the arrival of the ADFL in Mbandaka during which ADFL troops demanded that a resident shout in Lingala, the local language, to tell people in a crowd to quickly get down on the ground. Refugees in the crowd, who did not understand Lingala, remained standing and were subsequently singled out and fired upon by ADFL troops.[38]

At a barrier south of Kisangani in April of 1997, soldiers blocked a high-level diplomatic delegation from proceeding into an area where massacres had recently occurred. An aid worker described their attitude:[39]

The governor spoke with the soldiers, trying to convince them to let us pass. The soldiers told the governor in Kiswahili, 'we haven't finished our work yet. Tell them to go. We are not afraid to kill them. If they go past us, we will shoot to kill. We know that if we kill one of them, they will go away and leave us alone.'

The delegation could clearly hear the sound of heavy road machinery working nearby where refugees had been massacred in previous days.

The Wall Street Journal reported that the ADFL soldiers in Mbandaka had said that more important than fighting Mobutu's soldiers was the elimination of refugees.[40] To the contrary, non-Tutsi ADFL troops told Congolese in areas where massacres had taken place that the killing of refugees was not their business;[41] one Katangese general stated in a private conversation that he had nothing to do with refugee affairs.[42]

Other humanitarian organizations operating in eastern and central Congo expressed their frustration from having been manipulated by the ADFL in what they described as "bait and kill" operations. While attempting to locate and set up assistance stations for refugees dispersed in the forest, agencies claimed that they were required to be accompanied by an ADFL "facilitator." According to their reports, after refugees had been located and put in groups to facilitate humanitarian assistance, access would be cut off to the refugees by ADFL military. Typically, after several days of no assistance, humanitarian groups would find the refugees had disappeared or been dispersed. Humanitarian agencies claimed that the "facilitators" would inform ADFL military of concentrations of refugees to expedite their killings.[43]

At least one agency ceased providing services to refugees in certain areas in protest of this practice by the ADFL, estimating that fewer refugees would die from a lack of humanitarian assistance than would die if their work continued to serve as an orientation tool for ADFL military seeking out refugees.[44]

V. WHAT KABILA HAS TO HIDE: A CASE STUDY

Human Rights Watch/FIDH visited three villages along an eighty-kilometer length of road, one of the principal routes followed by Rwandan and Burundian refugees who fled the camps in eastern Congo in October and November of 1996. This same stretch of road was traveled by the FAZ, ex-FAR, and refugees, and finally by the ADFL.

Human Rights Watch/FIDH spent several days along this road, interviewing villagers and community leaders who had witnessed killings or other human rights violations or participated in burials. Civilian refugees who had survived the trek through this area were interviewed in Congo-Brazzaville and gave accounts that corroborated with those of the Congolese witnesses.

Several mass graves and execution sites were visited. Most of the killings occurred during a three-day period during which front-line ADFL troops advanced through this area, overtaking and killing civilian refugees with knives, machetes, and bayonets. The three-day period is described below.

Humanitarian law violations committed by the FAZ and the ex-FAR along this same length of road are also described below.

The three villages visited by Human Rights Watch/FIDH in August are like many others in the region. The exact locations and names of these villages may not be disclosed, and the names of witnesses have been changed due to their clearly stated fear of reprisal by Rwandan or Kinyarwanda-speaking elements of the ADFL (see Intimidation of Witnesses section below). The real names of the villages and the sources used by Human Rights Watch/FIDH have been submitted to the U.N. Secretary-General's Investigative Team for further investigation.

In addition to those mentioned below, many others killings by the ADFL are likely to have occurred over the same eighty-kilometer length of road over the same three-day period. As noted below, villagers were reluctant to give information regarding the killings by the ADFL due to fear of reprisals. Over the several days that Human Rights Watch/FIDH visited the area, villagers came forward with progressively more information, sometimes revealing execution sites of mass graves that had been "forgotten" the previous day. Villagers spoke openly and apparently without fear of reprisal about the violations committed by the FAZ or ex-FAR.

Human Rights Abuses Committed by the FAZ

The FAZ arrived in the first village in small groups over a period of approximately three weeks. The first group of about seventy-five arrived in approximately eight vehicles, reportedly stolen en route, and consisted of many officers, including at least one colonel. The FAZ continued to arrive and depart progressively up until just prior to the arrival of the ADFL. No combat occurred in the area.[45]

In the area near the villages, measures taken by state authorities and traditional chiefs appear to have resulted in far fewer human rights abuses committed by the FAZ, as compared to other villages and cities in their path of retreat (see above). Local authorities in the first village, warned of the imminent arrival of the FAZ, instructed the local population to make cash and in-kind donations for the fleeing soldiers. Upon arrival, local chiefs and administrators presented the FAZ with abundant food and supplies, preventing widespread looting, according to those in the first village. Numerous residents of the village praised the measures taken by the local authorities and claimed that the FAZ created few problems:

The FAZ arrived first in about ten vehicles with ten people per vehicle. Hearing of their arrival, most of the population had fled into the forest. They were welcomed by the population that remained in the village. The military were treated well, given food, materials, gas, and money. The military behaved.[46]

It should be noted that the particular experience of villages in this area was an exception to the general pattern of human rights abuses committed by the FAZ during their retreat across Congo. Consistent testimonies from other regions depict acts of rape, killing, destruction, and looting perpetrated by the FAZ, as described above.

Human Rights Abuses Committed by the Ex-FAR andInterahamwe Militia

Community leaders and villagers in the villages stated that local authorities attempted also to prepare for the arrival of the ex-FAR, Interahamwemilitia, and refugees, as had been done with the FAZ. Villagers described the arrival of the ex-FAR and the refugees as initially calm:

The first group was of about 3,000. They came in four single columns, two on the outside with guns, some in uniform, two columns of refugees on the inside. The military elements among them were strong and healthy; the civilian population was weak, emaciated, and sick. The chief had prepared their welcome. He had given instruction to give them free medicine in hopes of getting reimbursed afterwards. They stayed one night.[47]

With the arrival of more refugees the next day, the situation soon deteriorated. Employees of a major plantation in the area created a counting station near the first village where they recorded the passing of more than 9,000 refugees over the first three days. After that, they claimed they were too numerous to count. The flow continued over an eighteen-day period, ending with the arrival of the ADFL. UNHCR estimates that between 22,000 and 30,000 refugees traveled on this particular road between the villages, while thousands of others fled along different routes in the same area.

Abuses committed in the area by the ex-FAR and other armed exiles, presumed to be members of the Interahamwemilitia, were largely related to foraging and pillaging to sustain themselves. These consisted primarily of theft, destruction, and violations of physical integrity, as well as some killings.

Many residents of the area claimed that refugees looted extensively along the main road between the villages as well as in peripheral villages. Villagers stated that ex-FAR in uniform or armed exiles would beat or kill people for food if they offered any resistance. Such allegations of killings or beatings were frequent but vague. Michel, a local humanitarian worker, described the impact of the refugees and ex-FAR in the first village:

Refugees looted extensively for food and materials. The local population fled into the forest. Refugees killed Congolese. I heard of one person killed twenty-two kilometers from here. I heard that two others were killed also.[48]

Accounts of looting and threats by ex-FAR or other armed exiles were more detailed. At a local plantation, one employee described how ex-FAR in uniform looted his home and threatened to kill his wife.[49] Human Rights Watch/FIDH visited storehouses at the plantation that had been emptied by the ex-FAR and vehicles, now recovered, that had been stolen and extensively damaged by the ex-FAR.

The civilian refugee population, in a deplorable health and nutritional state, also had enormous impact on the population of the first village, numbering less than 4,000.[50] Civilian refugees stripped fields of their crops, used schools and houses abandoned by villagers for shelter, and overwhelmed local health centers. Residents of the first village claimed that the loss of material goods and damage to property was still having a profound impact on the local economy. Jean, an employee of the plantation explained the effects of the refugees:

The chief had done an impressive job of preparing food and assistance for their arrival, attempting to avoid looting. When the food supply became insufficient, the refugees looted. They threatened the local population for food, and they threatened a local doctor to give them all his medicine. If the food was insufficient, they killed.[51]

In August 1997, UNHCR reported estimates of several hundred civilian refugees in the surrounding area mixed with small numbers of ex-FAR.[52] At this time, villagers were concerned about the presence of civilian refugees, ex-FAR and militia in the area due to both the immediate security threat presented by armed elements and the fear that the ADFL forces would return to hunt them down. Months after the passing of the bulk of the refugees, many local villagers still had not returned to their homes out of fear of further abuses by either of these groups.

Human Rights Abuses Committed by the ADFL

The violations committed by the ADFL in the area near the villages consisted primarily of widespread killings of civilian refugees. Refugee men, women, and children who were too weak or sick to flee were killed by the first units of the ADFL coming into contact with them. The killings in the villages and on the road between the villages were carried out over a three-day period as the ADFL troops advanced and overtook refugees. No combat took place in the area as the last of the ex-FAR, Interahamwe, and FAZ had left several days before the arrival of the ADFL.

In the Gondi area, killings were carried out almost exclusively with knives, machetes, or bayonets. Villagers hypothesized that this deliberate strategy of not using bullets was to avoid scaring off other refugees ahead on the road, to conserve ammunition, or to leave fewer traces of their killings.

The first three days of the ADFL presence in the villages are described below.

Day one: The ADFL troops arrived in the first village around 4:00 p.m.. Almost all the refugees had left at this point, except for a few too weak to continue. The first few hundred ADFL arrived on foot, eventually followed by commanders in vehicles. Villagers described most of the troops as "Rwandan" or "Kinyarwanda-speaking" and very well-armed. Two of their commanders spoke Kinyarwanda, English, and Kiswahili, while one was of Katangese origin.[53]

A nurse in the first village watched the arrival of the ADFL:

The first ADFL arrived on foot in a group of around one hundred. Their vehicles came later. Upon arrival, they killed thirteen refugees, ten in the yard by the Catholic church and school, three over there by the crossroads. The refugees were killed with knives and machetes; they were the weak ones who were sick or malnourished. The soldiers who killed them spoke Kinyarwanda and French and told us the refugees were bad and should not be helped.[54]

A community leader described the killings and going to the burial:

The ADFL came and found the last group of refugees. I didn't see the killings as everyone was fleeing. I went to the burial: they were fifteen in all. Nine were killed in front of the Catholic church, next to the school; four more at the crossroads, and two over by the public works office.[55]

Jean helped to bury the bodies near the Catholic church and school:

They were a mix of men and women. There was one child about three years old. We buried twelve of them here in this grave and put one in with the other grave with two people who died from sickness. There are two more people in that third grave over there.[56]

Seventeen people in all were reportedly buried, fifteen killed by the ADFL, two from disease. The graves were visited and photographed by a Human Rights Watch/FIDH researcher accompanied by villagers who had participated in the burials. The three graves measured 3.5 by 3.5 meters, 1 by 3.5 meters, and 1 by 3 meters. Each grave was marked by a depression of 15 to 20 centimeters of freshly turned earth.

One local health worker initially claimed that there had not been any killings by the ADFL. When we asked him about the fifteen in the mass graves that Human Rights Watch/FIDH had visited, he confirmed that he too had assisted in the burial and that the refugees had been killed with sharp objects. He later told Human Rights Watch/FIDH in private that everyone in the village was frightened to speak about the killings because of the assassination of a local administrator by the ADFL.

Day two. The wife of a community leader explained how most of the ADFL troops left the first village the next morning and headed toward the second village, approximately thirty-eight kilometers away:

The first Alliance troops left the first village around 5:00 a.m. The two colonels stayed and had breakfast, leaving around 10:00 a.m. The killings had been done with knives, axes and machetes.[57]

The ADFL troops arrived on day two in the second village where they came upon several groups of refugees who were camped for the night. The refugees were unarmed and a mix of men, women and children. One Congolese eyewitness, who was in the second village and described the ADFL as Kinyarwanda speakers, stated:

The ADFL killed them in front of me with knives and machetes. I saw around fifteen cadavers, but I was trying not to look. The villagers were already burying refugees in groups of four or six in common graves. There were many, many killed; more than fifty.[58]

Another witness from the first village, who had accompanied the ADFL as a driver, said he saw between forty and fifty dead refugees in the second village upon his arrival. Residents of the second village reportedly witnessed the killings by the ADFL and later disposed of fourteen of the bodies in a defunct well, ten adults and four children, all unarmed civilians.[59] Human Rights Watch/FIDH photographed the well in which some of the remains of fourteen refugees were still visible.

At a bridge just past the second village, the remains of several campfires were still visible, with bones and skulls scattered in the brush nearby. As many as an additional fifty refugees had been killed at this site; bodies had been thrown into the river.[60]

In addition to those refugees killed by the ADFL, humanitarian agents from the first village stated that they had buried at least fifteen other refugees who had died due to disease, dehydration, or exhaustion between the first and second villages.

Day three: The front-line ADFL troops advanced twenty-two kilometers from the second village to the third village on their third day in the area.[61] Human Rights Watch/FIDH saw and photographed the remains of at least thirty refugees along this segment of the road. Eyewitnesses to killings or villagers who had assisted in disinfecting sites accompanied Human Rights Watch/FIDH and explained the circumstances of some of the killings or described the nature of the wounds of the dead. The cause of death was at times not known; most often, however, the testimony of eyewitnesses describing how certain refugees were killed was corroborated with physical evidence on the site, such as smashed skulls or other physical trauma.

Witnesses from the area estimate that hundreds of refugees had been killed between the second and third villages alone, but that some cleanup had already taken place. A medical doctor with extensive experience in the area estimated that up to 1,700 people may have been killed between the second and third villages. Residents of the area were particularly reluctant to accompany Human Rights Watch/FIDH along this segment of road due to a fear of reprisal by the ADFL.

All bodies or bones photographed were in the road or within a few meters of the road, some in groups of up to eight, often near or in the remains of campfires. Many of the skulls contained holes or were fractured, suggesting blows with a heavy object. All bodies were in approximately the same state of very advanced decomposition or were skeletons. Many of the remains were clearly identifiable as women or children.[62]

Human Rights Watch/FIDH was guided by individuals who had accompanied the ADFL troops or participated in clean-up activities. Jean-Pierre, who disinfected bodies in the area, described one site seven kilometers from the second village:

We disinfected bodies in this area for about a week. Right here, there were eight in all, where the refugees had been camped. Some of them are gone now; I think animals may have taken away some of the bones. The bodies all had knife wounds.

Another witness, who had carried gasoline for the ADFL, accompanied Human Rights Watch/FIDH to a site approximately one kilometer from this area where a refugee boy preparing food by the roadside was killed:

He was preparing food when the ADFL arrived and killed him with a knife and a machete. They cut his neck first, and then smashed his skull here on the left side.[63]

A photo taken by Human Rights Watch/FIDH of the site verifies a fracture to the left temple area of the skull. The skeleton of the boy lies in the remains of a campfire.

Seven kilometers further toward the third village lies a second bridge where Human Rights Watch/FIDH photographed the remains of six refugees. The skulls were partially smashed or contained holes and were in the vicinity of many campfires. One villager said he had accompanied a soldier whom he described as a Kinyarwanda-speaking colonel of the ADFL to the bridge shortly after the killings. He claimed that he had seen at least twenty-one bodies near the bridge but that many more had been thrown into the water:

We left [the first village] with a DAF truck and a motorcycle. We were in the second group with Colonel Cyiago. There were many cadavers near the second bridge. At night, the ADFL would do calisthenics and would go out into the forest. They held many meetings during the day. I remember a group of eight, a group of twelve, and one alone, but there were many more that had been swept away in the water.

Five kilometers from the second bridge is the third village, where UNHCR estimates that between 22,000 and 30,000 refugees had passed through a temporary camp. Numerous testimonies from Congolese, international humanitarian workers, and refugees in Congo-Brazzaville spoke of mass killings by the ADFL of refugees at the third village. A witness who had accompanied the ADFL to the third village stated that he saw several hundred cadavers in and around the camp upon his arrival:

On the road approaching [the third village], there were many, many cadavers. There were many more at the camp, several hundred. They were killed with knives and machetes, but right in the camp they had been shot, too.[64]

Civilian refugee survivors, interviewed in Congo-Brazzaville, stated that the ex-FAR had moved on long before the arrival of the ADFL and that no combat had occurred at the third village.[65] Congolese in the area similarly denied that combat had taken place anywhere near the third village.

Human Rights Watch visited the former refugee camp site at the third village which spread over some 800 meters of road and into the forest. The camp was littered with clothing, shoes, equipment and many bullet shells. No evidence of bodies or mass graves was present. According to villagers and relief workers, the site had been cleaned by the ADFL and the bodies of refugees, numbering in the hundreds, were dumped in a nearby river.

According to witnesses, the majority of these killings were carried out by Kinyarwanda speaking members of the ADFL, ethnic Tutsi from Rwanda, Uganda, and eastern Congo. Villagers consistently described elements of the ADFL who participated in killings as being "Rwandans." When asked to explain how they knew they were Rwandan, witnesses claimed that often the only languages spoken by refugees were Kinyarwanda or Kiswahili, and their morphology was different from Congolese: many were tall, very dark, and had facial features characteristic of some Tutsi.

VI. CLEANING UP: SITE PREPARATION AND THE INTIMIDATION AND KILLING OF WITNESSES

Authorities in Congo have made concerted efforts to conceal the evidence of civilian killings. The ADFL and its allies, especially Kiswahili and Kinyarwanda-speaking elements, have engaged in a campaign to cover up civilian killings throughout Congo, largely through the physical cleansing of massacre sites and by the intimidation of witnesses. These efforts have been ongoing since the beginning of the war in October 1997 and up to the present throughout eastern, central, and western Congo. It is likely that efforts in both of these areas-cleanups and intimidation-have intensified since April 1997, paralleling an increase in allegations of massacres and the arrival in the region on four separate occasions of United Nations investigative teams.[66] Pressure from the international community on the Congolese government to cooperate with the U.N. missions may also have contributed to intensified cleanup and intimidation efforts by the ADFL and its allies.

Unlike the area near the three villages visited, located in a remote part of Congo, most massacre sites have been cleaned up by the ADFL or local villagers under their instruction. Major massacre sites have been subject to particularly concerted efforts, such as those in the Goma refugee camps or the area south of Kisangani, using dozens of villagers and heavy equipment.[67]

A large number of cleanups have taken place in North-Kivu where thousands of civilian refugees and Congolese have been killed since October 1996.[68]

Civilian killings increased with the attacks on refugee camps in North and South-Kivu in October 1996. In the city of Goma and the North-Kivu camp area alone, the UNHCR made arrangements for the burial of more than 6,800 people,[69] a mix of men, women and children in and around the camps themselves.[70] Residents of Goma, however, stated that roads leading to the camps were blocked by the ADFL immediately after the attacks. Before the U.N. had access to the camps, a front-end loader from the local public works department was seen heading toward the camps. An international journalist visited one site near the camps during this period where bodies were being dumped in a ravine, with heavy equipment tracks leading away.[71] Local villagers from the area stated that they had been eyewitnesses to the ADFL's use of a front-end loader to dispose of bodies from the camps in the ravine.[72]

Another notable cleanup operation was conducted south of Kisangani in late April and May 1997, following large-scale killings. Subsequent to several attacks in mid to late April on temporary refugee camps south of Kisangani by a mix of villagers and ADFL troops, humanitarian workers were denied access to the area by the ADFL troops. Independent eyewitnesses gave consistent reports to Human Rights Watch/FIDH of heavy machinery and trucks being used by the ADFL or workers engaged by them in the area where the camps had been.[73] While access was cut off, many trucks loaded with firewood were seen heading toward the former campsites. Several sources reported that bodies were being burned and ashes disposed of in rivers or deep in the forest.[74] In mid-September, the New York Times reported that the driver of a tractor used in these cleanup efforts and a Belgian national who owned heavy machinery and land in the massacre area were arrested without charge.[75] This report was later corroborated by French and Belgian authorities who reported on September 26, 1997 that two residents of Kisangani, nationals of France and Belgium, had been arrested without charges and were being held for questioning. Knowledgeable sources stated that the two were in possession of a videotape of evidence pertaining to massacres in the Kisangani area.[76]

Villagers and aid workers reported that smaller cleanups have continued from the beginning of the war up to the present in several different regions. In the Rutshuru area of North-Kivu, several villages where massacres had occurred were visited by development workers in March of 1997. The evidence at sites consisted of the charred remains of houses with bones and skeletons visible inside. When the site was revisited several months later, the remains were gone: villagers told them that Kinyarwanda-speaking ADFL soldiers had come back to the sites and ordered them to clean up the sites and hide the remains in common graves.[77]

Another recent cleanup was witnessed by a resident of Goma who was traveling into the Masisi area in July of 1997. The witness reported that ADFL soldiers stopped the truck he was traveling with and all traffic on the road for a period of thirty-six hours, claiming that the way ahead was unsafe. When the truck was allowed to proceed, the witness claimed that smoke and bones were visible near a small river by the roadside where the ADFL had been working.[78]

Congolese in villages visited by Human Rights Watch/FIDH were reluctant to speak of the killings and stated that they feared reprisals from Kinyarwanda-speaking members of the ADFL.[79] Congolese who have spoken out against the killings, or those who have been suspected of speaking out, have been subject to intimidation, beatings, arrests or killings by ADFL. Residents of Goma told Human Rights Watch/FIDH with apprehension of an incident during which two humanitarian workers in Bunyakiri, South-Kivu, had "disappeared" shortly after showing mass grave sites to foreigners.[80]

Such claims were frequent. In one village in Haut-Congo, residents spoke of a local civil servant, Mr. Kahama, who had been arrested at his home by a Kinyarwanda-speaking ADFL officer. The officer criticized Mr. Kahama for having made a call via high frequency radio to Kisangani, requesting gloves and disinfectant to bury a large number of refugees who had been massacred by ADFL troops in his village. Mr. Kahama was taken to Kisangani to meet with a local ADFL commander for questioning. Guards outside the home of the commander subsequently heard Mr. Kahama crying out for help and then gunshots being fired. Mr. Kahama's body remains missing.[81]

The president and executive secretary of the Regional Council of Non-Governmental Development Organizations (CRONGD) in the Maniema province were arrested by ADFL military under the orders of Commander "Bikwete" and Commander "Leopold" on August 6, 1997 in Kindu. Both commanders were described by residents of Kindu as "Banyamulenge." The two CRONGD officials, Bertin Lukanda and Ramazani Diomba, were suspected of providing information to the U.N. Investigative Team regarding the killings of refugees in Maniema.[82] Both men were beaten severely and detained at Lwama military camp. Mr. Ramazani Diomba, the executive secretary, was hospitalized due to the beating; Mr. Lukanda, also a staff member of a local human rights organization, remained in detention for thirty-one days. Two of Mr. Lukanda's colleagues from his human rights organization have been prohibited by the ADFL from leaving Kindu.[83]

A witness from Haut-Congo, Jean, stated in his first interview with Human Rights Watch/FIDH that there were no problems in his village in Haut-Congo when the ADFL arrived, describing them as the "liberators." When asked specifically about alleged killings in the area, he stated that he was not interested in talking about "politics." Over the next few days, Jean provided progressively more information regarding killings committed by the ADFL and brought additional eyewitnesses to Human Rights Watch/FIDH. Jean explained that he, like many in his village, were frightened after the abduction and killing of a local civil servant as the ADFL "did not joke around" when it came to killings.

Similarly, according to a local organization in Goma, on at least one public radio station there, the Voice of the People, announcements have been made in Kiswahili to discourage the population from cooperating with the U.N. team investigating the massacres.[84] The ADFL led ideological seminars in the east throughout early 1997 informing local populations that all refugees who had wanted to return to Rwanda had done so; seminar leaders told participants that any Rwandans who remained were ex-FAR or Interahamwe and therefore should be exterminated.[85]

VII. WHO IS IN CHARGE: TOWARDS ESTABLISHING RESPONSIBILITY

During a July 1997 interview with the Washington Post, Rwandan Vice-President Paul Kagame claimed that the Rwandan government had planned and led the military campaign that dispersed the refugee camps in Eastern Congo and ousted former President Mobutu.[86] According to the Washington Post, Kagame was unequivocal concerning his objectives:

The impetus for the war, Kagame said, was the Hutu refugee camps. Hutu militiamen used the camps as bases from which they launched raids into Rwanda, and Kagame said the Hutus had been buying weapons and preparing a full-scale invasion of Rwanda.

Kagame said the battle plan as formulated by him and his advisors was simple. The first goal was to 'dismantle the camps.' The second was to 'destroy the structure' of the Hutu army and militia units based in and around the camps either by bringing the Hutu combatants back to Rwanda and 'dealing with them here or scattering them.' [87]

Kagame's third objective was to topple Mobutu. Congolese President Kabila confirmed Rwanda's military assistance in Congo during an official visit to Kigali on September 9, 1997, when he publicly thanked Rwanda for their help during the war.[88]

These statements lend support to the numerous testimonies taken by Human Rights Watch/FIDH from Congolese, refugees, and expatriates in Congo regarding the presence of Rwandan and other foreign troops in Congo during the war. Similarly, Kagame's stated objective of destroying "the structure" of the ex-FAR provides a possible explanation for the active pursuit of refugees, former military, and militia across Congolese territory to areas of minor strategic importance, such as Mbandaka.

Despite the public recognition of military involvement, both Kabila and Kagame have denied that any civilian massacres took place by troops under their command.[89] Both during the war and up to the present, however, the identities of many commanding officers and strategists of the ADFL and its allies were kept secret. Throughout the seven-month military campaign, senior officers in the field were often out of uniform and many used only their first names in public. Similarly, ranks were apparently confused or intentionally simplified to avoid identification of the military hierarchy: many officers of Katangese or Angolan origin were given or assumed the rank of "general", while numerous Ugandan and Rwandan officers were known only as "commander" or "colonel" followed by their first name only. It is possible that many of these first names that were used in public are pseudonyms.

Regional power structures that reflect the pattern in Kinshasa have been put into place in many of the provinces. In several regions, governors from the political opposition or from local ethnic groups have been installed, at times through simple hand-raising elections in stadiums. Despite this apparent democratic method, Congolese community leaders and civil servants, international humanitarian workers, and U.N. officials claimed that civilian authorities have had little power in decision-making, especially regarding refugee issues, and that important questions were handled by military authorities.

In several provinces, Katangese generals have been installed as regional military commanders, seconded by Rwandan or Ugandan officers in charge of operations and questions related to refugees and security. Tension often exists between the various military factions, especially between those of Rwandan or Ugandan origin and those from Angola, Katanga, or non-Kinyarwanda speaking groups.[90] One Katangese general, allegedly responsible for the province of Equateur, stated flatly to a Congolese humanitarian official that he did not handle refugee issues.[91]