Summary

There are specific types of violence that target queer women, even when we’re closeted. Machorra, that’s the Spanish version of dyke. We do things men do not like. I love to drive my truck. Friends hop in and out. Men don’t like it. Because it means that I move on my own; I do not need them. I’m not sure if it’s a queer women specific trait, but when we work with men in activist spaces, we do not seek their approval. If we don't aim to please them, they call us violent. We make men angry.[1]

– Sofía Blanco, indigenous land defender, Mexico

“I think one queer woman’s story can change those that come after it. That is why I agreed to talk to you, to tell you what happened.[2]

– Amani, lesbian activist and writer, Tunisia

In June 2021, Amani’s girlfriend ended their relationship. Amani told Human Rights Watch that for months prior to the breakup, her girlfriend’s parents had been “refusing to let her leave the house” and “pushing her to marry a man.”[3] They ultimately succeeded, and the woman left Amani. Amani said it was “not the first” time in her life that a woman left her due to “the simple, disturbing fact that because I am not a man, I am not a good enough partner for the woman I love.”

While speaking to Human Rights Watch, Amani only mentioned Tunisia’s well-documented,[4] violent[5] treatment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people once.[6] Most of the conversation was about her writing and her love life.

Amani knows that as a lesbian, she is at risk of physical violence, sexual harassment, and arbitrary arrest by police in Tunisia. In fact, she has experienced all three of these abuses. However, despite having received significantly less attention from the media and NGOs around the world, coercive marriage practices also harm queer women’s rights, freedoms, and opportunities for joy, in direct violation of international human rights laws that protect the right to free and full consent to marriage.[7] According to Amani, the queer women she knows have “either been coerced into marrying a man or been broken up with by a girlfriend who was coerced into marry a man. It’s everywhere. It’s the backdrop to our lives.”

Her words echoed stories told to Human Rights Watch by other lesbian, bisexual, and queer (LBQ+) people[8] around the world affected by marriages to men they did not want to enter or cannot leave, including in Indonesia, Malawi, and Kyrgyzstan. Liliya, the founder of an LBQ+ organization in Kyrgyzstan, was forced to marry a man by her parents at age 19. Asante, a lesbian in Malawi, has been physically assaulted twice by the husband of her bisexual partner, a woman who wants, but does not have the money to get, a divorce. Dali, a bisexual youth activist in Indonesia, says her community has lost “dozens of queer women mentors who are pressured into marrying men.”[9]

Documentation of forced heterosexual marriages of LBQ+ women is scarce. In 2019, queer feminist group Mawjoudin[10] released a three-minute creative film Until When?[11] in which a Tunisian woman is waxed and groomed ahead of her (presumably arranged) marriage to a man. She storms out of the house mid-video and announces to the camera, “I love someone. ... And she is not a man.”

The film is a rarity. In Tunisia and elsewhere, forced marriage research[12] and policy is largely situated within women’s rights[13] and children’s rights[14] discourses, and rarely if ever explicitly acknowledges the existence of queer people.[15] NGOs, donors, governments, and policy makers working to end forced marriage seldom address issues related to sexuality, or forced marriages specifically of LBQ+ women. The presumption of heterosexuality in forced marriage studies, policies, and funding precludes an analysis of how a coerced heterosexual marriage makes it impossible or dangerous for an LBQ+ person to live a queer life.

According to interviews Human Rights Watch conducted with 66 lesbian, bisexual, and queer (LBQ+) activists, researchers, lawyers, and movement leaders in 26 countries between March and September 2022, forced marriage is one of ten key areas of human rights abuses most affecting LBQ+ women’s lives. Human Rights Watch identified the following areas of LBQ+ rights as those in need of immediate investigation, advocacy, and policy reform. This report explores how the denial of LBQ+ people’s rights in these ten areas impacts their lives and harms their ability to exercise and enjoy the advancement of more traditionally recognized LGBT rights and women’s rights:

- the right to free and full consent to marriage;

- land, housing, and property rights;

- freedom from violence based on gender expression;

- freedom from violence and discrimination at work;

- freedom of movement and the right to appear in public without fear of violence;

- parental rights and the right to create a family;

- the right to asylum;

- the right to health, including services for sexual, reproductive, and mental health;

- protection and recognition as human rights defenders; and

- access to justice.

This investigation sought to analyze how and in what circumstances the rights of LBQ+ people are violated, centering LBQ+ identity as the primary modality for inclusion in the report. Gender-nonconforming, non-binary, and transgender people who identify as LBQ+ were naturally included. At the same time, a key finding of the report is that the fixed categories “cisgender” and “transgender” are ill-suited for documenting LBQ+ rights violations, movements, and struggles for justice. As will be seen in this report, people assigned female at birth bear the weight of highly gendered expectations which include marrying and having children with cisgender men, and are punished in a wide range of ways for failing or refusing to meet these expectations. Many LBQ+ people intentionally decenter cisgender men from their personal, romantic, sexual, and economic lives. In this way, the identity LBQ+ itself is a transgression of gendered norms. Whether or not an LBQ+ person identifies as transgender as it is popularly conceptualized, the rigidly binary (and often violently enforced) gender boundaries outside of which LBQ+ people already live, regardless of their gender identity, may help to explain why the allegedly clear division between “cisgender” and “transgender” categories simply does not work for many LBQ+ communities. This report aims to explore and uplift, rather than deny, that reality.

Beyond Women and LGBT

The desk review and interviews conducted for this report finds that when LBQ+ experiences of violence are discussed and documented, it is most often as a sub-violation of broader LGBT rights abuses or, less frequently, a sub-violation of women’s rights abuses. This conceptualization presents LBQ+ women as merely a variation on a theme that was not built for them. It perpetuates their marginalization for two main reasons:

- Policies and research focused on “women’s rights” often address the ten issues above, but rarely explicitly name LBQ+ women as rights-holders or analyze how their unique experiences of violence warrant more specific laws, policies, and protocols to protect them. Specifically, women’s rights research and policies related to forced marriage and property rights implicitly assume heterosexuality and a binary construction of gender, and rarely address abuses experienced by queer women.

- LGBT rights research and policies are significantly more likely than women’s rights research to explicitly name LBQ+ women as rights-holders and victims. However, they are significantly less likely to address the broader societal and legal restrictions on people assigned female at birth which prevent their enjoyment of “LGBT rights” advancements.

In 2017, the World Economic Forum published an article entitled “What you need to know about LGBT rights in 11 maps.”[16] The color-coded quick guide to various legal statuses, protections, and prohibitions of LGBT rights included maps showing the criminalization of homosexuality, marriage equality, legal gender change, legal adoption, protection from discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity, prohibition of housing discrimination, bans on military service and blood donations, “age of consent for homosexual sex” equality.[17]

Advancing these rights issues is necessary but not sufficient for the full recognition of rights for LBQ+ individuals and communities. The decriminalization of same-sex practices, for example, may have a decidedly small impact on the life of a queer woman in a country where sexist laws and policies prohibit her from inheriting her parent’s property, renting an apartment without a male guardian’s permission, or seeking a divorce from a marriage she was coerced into.

Normative conceptualizations of LGBT rights have not effectively incorporated fundamental areas of women’s rights investigation and policy work, such as forced marriage of women and girls, women’s property rights, and their freedom of movement. In other words, basic restrictions on women’s freedom, autonomy, and economic empowerment, which are often key barriers to LBQ+ rights, are not considered relevant to the progression of LGBT rights. There is an immense opportunity for future investigations into the nine rights areas covered in this report, with the aim of improving LBQ+ rights and lives.

In addition to increasing the number of LBQ+ women interviewed or consulted for future LGBT or women’s research projects, research topics should intentionally center the issues that LBQ+ women say most affect their lives (Sections III-X). This will allow for a deeper, more complex analysis of how and in what circumstances LBQ+ rights are violated and reveal the multiple ways in which states are failing LBQ+ women.

Policy and Recommendations

Concurrent to these research gaps, Human Rights Watch found a clear lack of laws and policies that explicitly name LBQ+ women as rights-holders in the ten areas covered in the report. This lack of legal protection and the alleged “invisibility” of LBQ+ women in national and international law are barriers to their ability to access justice.[18]

This report finds that the LBQ+ research gap matters because it drives—and is driven by—a system of mutually reinforcing gaps: the lack of research into violations and abuses of LBQ+ people’s rights; the lack of laws and policies that explicitly protect the rights of LBQ+ people; barriers to accessing justice for LBQ+ victims of human rights abuses; and the lack of funding for LBQ+-led movements.[19]

The gaps implicate governments and donors as stakeholders who should take specific steps to address these problems in order to protect LBQ+ people from a lifetime of intersectional violence and discrimination. Key recommendations are:

- Governments should develop laws, policies, and protocols that explicitly protect the rights of LBQ+ people. Authorities should also reform patriarchal systems of control, including male guardianship laws, policies, and practices; discriminatory property and inheritance laws; and other restrictions on women’s autonomy, movement, and freedom, which limit LBQ+ access to other more traditionally conceptualized “LGBT rights.”

- Donors should fund LBQ+-led movements, rather than seeking to fund only LBQ+ groups working on “LGBT rights” as they are normatively conceptualized. This funding should manifest in two ways: 1) Fund LBQ+-led groups working on land, environmental, and indigenous rights, humanitarian response, disability rights, and forced marriage, and LBQ+ women living in poverty. This will support LBQ+ activists in documenting and advocating against the multiplicity of violations their communities endure and in building allies to surmount the structural barriers they face to accessing justice. 2) Fund LBQ+-led movements working specifically for LBQ+ rights, and ensure that grantees are not pressured to expand their work to accommodate broader, normative conceptualizations of “LGBT rights.”

- Researchers should conduct targeted investigations into how restrictions on women’s freedom and autonomy impede the advancement of LGBT rights. This research should be done in partnership with LBQ+ organizations to produce knowledge about specific violence they experience. This will inform what specific law and policy changes will best support safety, justice, and rights for LBQ+ women in particular contexts, beyond those identified in this report.

Forced Marriage (Section III)

Compulsory heterosexuality, the pressure to marry men, and coercive marriage practices were the most frequently reported abuses experienced by LBQ+ interviewees, including in Canada, Indonesia, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Malawi, Mexico, Poland, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Tunisia, and Ukraine. There is an immediate need to develop laws, policies, and protocols that explicitly protect LBQ+ people from forced marriage or coercive marriage practices. Interviewees reported abuses including forced marriage as a conversion practice; punishment from family for failure to conform to heteronormative markers of adulthood; psychological abuse and humiliation as coercive tactics; the infantilization of unmarried or divorced LBQ+ women; and violence against the partners of LBQ+ women married to men.

States should produce national action plans to end forced and coerced marriage practices that explicitly include an intersectional approach to the elimination of all forms of conversion practices, and collaborate with local and national LBQ+ organizations and unregistered collectives at each stage of conceptualization, drafting, and implementation. Governments should ensure that violent intimidation and retribution against people for refusal to marry are punishable under law and that survivors have access to adequate, gender- and SOGIE-sensitive legal, medical, and psycho-social services. Finally, states should end discriminatory divorce laws, which make it significantly easier for men to divorce their wives than for women to divorce their husbands and thus harm LBQ+ women who wish to leave their husbands without fear of retribution, violence, or losing custody of their children.

Property Rights (Section IV)

According to recent World Bank Group studies, two-fifths of countries worldwide limit women’s property rights,[20] and in 44 countries, male and female surviving spouses do not have equal rights to inherit assets.[21] There exists a chronic lack of research into how LBQ+ women’s rights are impacted by patriarchal laws, policies, and customs like these, which limit women’s rights to own and administer property.

In a preliminary scoping, this report finds that violations of women’s property rights are a queer issue because they harm LBQ+ women’s ability to live queer lives free from violence and discrimination. This includes by forcing them to hide their sexualities, partners, and queer lives from their biological families to avoid further discrimination in inheritance regimes that already privilege sons; requiring LBQ+ women to marry men in order to have access to land and property (reinforcing the coercive marriage practices above); preventing LBQ+ couples from pursuing a life together; and violating their rights to freedom of association and assembly, which compounds existing barriers to queer organizing and community building.

In many countries, discriminatory laws restricting women’s access to property are relics of, or were heavily influenced by, colonial property laws.[22] These often intersect with and compound harmful traditional practices and customary laws. While analyzes of the effects of colonialism on LGBT rights typically focused on the criminalization of same-sex conduct and the imposition of binary constructions of sexual orientation, gender identity and expression (SOGIE) as forms of social control,[23] [24] colonial property laws have impacted LBQ+ women’s lives as much as, if not more than, colonial anti-homosexuality laws.

States should revoke discriminatory property laws, restrictions on women’s labor, and sexist family codes, including those that persist in formerly colonized countries. States should also amend family law to articulate the concept of marital property and allow for its division on an equal basis between spouses, recognizing financial and non-financial contributions made by women.

Violence Against Masculine-Presenting LBQ+ People (Section V)

Gender expression is a critical component of how, why, and in what circumstances LBQ+ people are attacked and have their rights violated. LBQ+ people interviewed for this report repeatedly named gendered discrimination against masculine-presenting people assigned female at birth in particular as the catalyst for a lifetime of economic, social, workplace, psychological, physical, and sexual violence.

LBQ+ advocates in Argentina, El Salvador, Indonesia, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Malawi, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, and the US reported that from a young age, styles of dress read as masculine, gender-nonconforming, or androgynous resulted in threats from parents to remove such girls from school, compounding the already precarious access to education that girls face globally. According to Rosa, a sex worker rights defender and lesbian woman in El Salvador, police are “far more brutal” to masculine-presenting queer women during arrests and street harassment, which, Rosa said, is particularly dangerous because employment discrimination based on their masculine-presentation is a large part of what originally forced many LBQ+ people into sex work.

Violence against masculine-presenting people assigned female at birth weaves throughout the report, continuing to indicate the need for greater focus on gender expression, in particular, in analysis of abuse, violence, and crimes committed based on SOGIE.

States should pass comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation that prohibits discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression, and explicitly add gender expression to legislation that already prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Interviews indicate that states should also introduce legal protections for gender non-conforming primary and secondary students, the absence of which can impact a lifelong trajectory of violence and discrimination for masculine-presenting LBQ+ people, and immediately investigate and end violent policing and arrest tactics that discriminatorily impact their lives.

Violence and Harassment at Work (Section VI)

Rosa’s account of violence against masculine-presenting sex workers echoed reports from LBQ+ activists in Ghana, Kenya, and a regional network in Central Asia who spoke of the multiple forms of economic marginalization that, they say, force LBQ+ women, non-binary people, and trans men into sex work, where many are denied basic protection of their rights.[25] During interviews in other countries, LBQ+ activists told Human Rights Watch about other forms of violence at work against LBQ+ women and their lack of access to redress, including in Kenya, Argentina, and Kyrgyzstan.

Research is needed into violence and harassment of LBQ+ women, non-binary people, and trans men at work, including abuse perpetrated by male coworkers, employers, supervisors, and third parties. Interviews indicate that groups at particular risk include masculine-presenting people assigned female at birth, unmarried women, feminine queer women who are out at work, and LBQ+ people who are openly in a queer relationship. Working with LBQ+ movements, future research should investigate labor rights violations in fields of work that LBQ+ people say are important, popular, or common among their community members. This will allow for labor rights reform in fields critical to the economic survival of LBQ+ people, couples, and communities, without necessitating the sort of radical “outing” that often makes including LBQ+ people in workplace research dangerous.

States should enact labor rights laws that explicitly protect LBQ+ workers from violence, harassment, and discrimination at work, including laws which protect workers from discrimination because of sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression.

Freedom of Movement (Section VII)

LBQ+ interviewees in El Salvador, Lebanon, Kyrgyzstan, Malawi, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Turkey, Tunisia, and the US reported extreme, gendered constraints on LBQ+ women’s freedom of movement. As in other areas, there is an urgent need for more intersectional research that addresses, for example, what it means for LBQ+ women that “legal provisions limiting women’s freedom to decide where to go, travel and live still exist in 30% of the 187 economies examined”.[26]

As women’s advocates have documented and argued, states should end patriarchal legal systems, such as male guardianship laws that restrict women’s rights to marry, study, work, rent or own property, reproductive health, and travel, and refrain from issuing laws, policies, decrees, and emergency measures that discriminatorily restrict women’s freedom of movement. Researchers and advocates are encouraged to view these issues not only as women’s rights reforms, but as central to the advancement of LGBT rights.

Additionally, interviewees said restrictions on their freedom of movement stemmed not only from the application of sexist, patriarchal legal regimes, which impact LBQ+ women’s ability to travel and move freely, but also from violence against LBQ+ individuals and couples in public, which cause them to limit when and how often they leave the house, and if they do so with their partner. Human Rights Watch compiled accounts of nine LBQ+ couples murdered or brutally attacked in just five countries (Italy, Mexico, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the US) since 2015. Interviewees say that such attacks cause them to “self-police” their movements, due to fear of leaving the house together with their partner.

States should conduct thorough, transparent investigations into reports of violence against LBQ+ individuals and couples and establish human rights desks at police stations to provide a safe environment for LGBT persons to report police abuses and for complaints to be processed and investigated without delay.

Parental Rights (Section VIII)

Parental rights and reproductive rights were raised as key concerns among LBQ+ organizers and lawyers in Argentina, El Salvador, Kenya, Malawi, Mexico, Poland, Ukraine, and the US. Critically, LBQ+ people want to create and protect their families, regardless of the criminalization of same-sex conduct or legalization of same-sex marriage. LBQ+ interviewees in several countries where same-sex conduct is criminalized, such as Kenya and Malawi, told Human Rights Watch that creating families was a top priority, but that they lack information on how to safely do so.

The report calls on states to revoke laws that prevent single women and unmarried couples from adopting, and to pass LGBT-inclusive parental recognition bills that explicitly recognize the legal parenthood of non-gestational LBQ+ parents and protect them from discriminatory demands that they adopt their own children. States should also reform discriminatory adoption laws and policies that make adoption unfairly difficult for racialized and economically marginalized LBQ+ parents, and introduce anti-discrimination legislation prohibiting insurance policies that discriminate against LBQ+ couples and individuals from accessing reproductive treatments, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), egg freezing, and sperm donation.

Asylum (Section IX)

Interviews conducted for this report indicate that LBQ+ parents and couples fleeing situations of conflict or seeking asylum for a range of other reasons face unique and potentially life-threatening barriers. Additionally, LBQ+ families also face unique barriers to being resettled abroad as a family unit. When interviewees discussed migration and asylum issues, they most often spoke about threats to family unity during resettlement.

Many asylum regimes require refugee couples to be married, in civil partnerships, or able to provide proof of living together in a relationship akin to marriage for a certain period of time prior to applying for reunification. This makes family unity incredibly precarious for all LGBT families. Compounding this, what little targeted research exists on the barriers faced by individual LBQ+ asylum seekers offers insight into unique struggles families face when both parents are LBQ+ people.

States should develop clear asylum and refugee resettlement family reunification guidance for LGBT family unity that allows LBQ+ asylee and refugee parents and families to reunite with separated children and other family members. Additionally, states should train asylum decision makers to recognize the intersection of membership in the LBQ+ social group with the risk of persecution in the context of a range of discriminatory economic, legal, and social issues faced by LBQ+ asylum applicants as individuals, parents, and families.

Health (Section X)

LBQ+ advocates reported a severe lack of consistent, safe access to a wide range of health services, including mental health support,[27] reproductive health care,[28] fertility treatment,[29] maternal health,[30] routine testing for cancer,[31] and access to services for people living with HIV.[32] In interviews, Human Rights Watch found that LBQ+ organizations are particularly focused on addressing the lack of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) services available to LBQ+ women, including sexual and reproductive health care, testing, and treatment for LBQ+ survivors. Tamara, an intersex lesbian activist in Malawi and founder of a queer foundation, dedicated her life to ending SGBV against LBQ+ women after surviving what she called “corrective rape” at the age of 19.[33] She told Human Rights Watch that LBQ+ women in her community are dying of untreated sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and other complications related to sexual assault due to their inability to safely seek care at public hospitals due to lesbophobia on the part of medical professionals, while private hospitals remain financially out of reach for many LBQ+ women.

Activists in Canada, Kenya, Indonesia, and Malawi reported a lack of LBQ+-informed therapy and addiction recovery services. States should enact policies and protocols supporting LBQ+ survivors of sexual assault and introduce nondiscrimination protections for LBQ+ women in access to health care. Governments should also work with LBQ+ organizations to establish a complaints procedure through which LBQ+ women who experience human rights violations or abuses in a health care setting, including discrimination, denial of services, or conversion practices aimed at changing their SOGIE, can file complaints and seek support and redress. Donors are encouraged to work with LBQ+ groups to support the establishment of community-based mental health programs and queer-informed recovery services for substance abuse, taking into account the particular privacy needs of LBQ+ women who are married to men.

Human Rights Defenders (Section XI)

LBQ+ activists interviewed for this report are leaders in a wide range of social, political, land, environmental, economic, gender, and racial justice movements, beyond the bounds of what is typically conceptualized of as “LGBT rights” work.[34] The report identified three key challenges to the protection of LBQ+ human rights defenders: risks related to their intersectional work and identities (including the criminalization of LGBT people in many countries); their lack of international visibility and perceived legitimacy; and a lack of funding.

Despite the global trend toward increasing visibility and protection for human rights defenders,[35] LBQ+ activists are often not recognized as defenders and therefore are denied access to protection frameworks. States should adopt human rights defender protection and recognition laws that explicitly affirm the rights of LBQ+ human rights defenders and establish human rights defender protection mechanisms with staff trained on the specific risks and needs of LBQ+ human rights defenders. Staff at these mechanisms should conduct outreach to LBQ+ organizations and unregistered collectives, and have dedicated supports in place for the physical, sexual, digital, and verbal threats received by LBQ+ defenders. Police and security forces need to ensure that LBQ+ human rights defenders who report attacks and threats to police are not sexually, physically, or verbally harassed or assaulted by officers, and that defenders are able to file incident reports without fear of retaliation.

Donors should reform restrictive funding requirements that force LBQ+ organizations to demonstrate exclusive work on LGBT issues and allow LBQ+-led organizations and collectives to apply and receive funding for intersectional work in a range of human rights areas including women’s rights; land, environmental, and indigenous rights; disability rights; migrant rights; housing and homelessness; right to health and health care access; and humanitarian aid. Additionally, donors should ensure that funding for LBQ+ organizations include budget lines for human rights defender security, and cover the costs of physical meeting spaces and transportation for training, community-building, and wellness. Finally, donors are encouraged to support programs and services for LBQ+ well-being and psychosocial care, and explicitly ask local organizations what their mental health needs are.

Access to Justice (Section XII)

LBQ+ women face multiple systematic barriers to accessing justice, including those that women and non-binary people face more generally—such as discrimination based on gender in state and non-state institutions, limitations on their time and resources due to care responsibilities, and violations of their rights to education and freedom of movement—and those that LGBT people face more generally, such as a lack of lawyers trained and willing to work with queer communities, courts that discriminate against LGBT people and families, and a wide range of laws criminalizing LGBT people that make reporting to police a dangerous act.

In addition to facing both these sets of barriers, the report interrogates five additional barriers to accessing justice that stem from a lack of: laws and policies protecting LBQ+ rights, documentation of anti-LBQ+ violence, understanding of what constitutes anti-LBQ+ violence, sustainable funding, and research into specific structural barriers.

Glossary

Bisexual: Sexual orientation of a person who is sexually and romantically attracted to people of more than one gender. Historically understood to mean attraction to both men and women, the term is now used in a manner more inclusive of transgender and gender non-conforming people.

Butch: Term typically used by masculine-presenting LBQ+ people to describe their gender expression. Sometimes, it is used to describe sexual orientation or gender identity.

Cisgender: Term that denotes or relates to a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with the sex assigned to them at birth.

Femme: Term typically used by feminine-presenting LBQ+ people to describe their gender expression. Sometimes, it is used to describe sexual orientation or gender identity. The term is also common among transgender women.

Feminine-presenting: Describes a person who adopts a visual aesthetic that is culturally coded or aligned with women or femininity, which could include types of clothing, mannerisms, haircuts, and patterns of speech.

Gay: Synonym in many parts of the world for homosexual. It is used by LGBT people to refer to varied sexual orientations and gender identities.

Gender: Social and cultural codes (as opposed to biological sex) used to distinguish between what a society considers “masculine,” “feminine,” or “other” conduct.

Gender-Based Violence: Violence directed against a person because of their gender or sex. Gender-based violence can include sexual violence, sexual exploitation, sexual harassment, domestic violence, psychological abuse, harmful traditional practices, economic abuse, and gender-based discriminatory practices. The term originally described violence against women, but it is now widely understood to include violence against individuals of all genders based on how they experience and express their gender and sexuality.

Gender Expression: External characteristics and behaviors that societies define as “masculine,” “feminine,” “androgynous,” or “other,” including dress, appearance, mannerisms, speech patterns, and social behavior and interactions. Gender expression is distinct from, and not necessarily reflective or indicative of, a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

Gender Identity: A person’s internal, deeply felt sense of being a man, woman, non-binary person, or other gender. It does not necessarily correspond to their sex assigned at birth.

Gender Non-Conforming: Behaving or appearing in ways that do not fully conform to social expectations based on one’s assigned sex at birth.

Heteronormativity: A system that normalizes behaviors and societal expectations that are tied to the presumption of heterosexuality and an adherence to a strict gender binary.

Heterosexual: Sexual orientation of a person whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward people of a different sex.

Homophobia: Fear of, contempt of, or discrimination against LGBT people or queerness.

LBQ+: Acronym for lesbian, bisexual, and queer. The term includes cisgender people, transgender people, non-binary people, and people of other genders who identify as lesbian, bisexual, or queer.

LGBT: Acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. Used here as an inclusive term for groups and identities sometimes associated together as “sexual and gender minorities.”

Lesbian: Commonly understood to mean a woman whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward other women. Used here to include people of other genders, such as gender non-binary people, who identify as lesbians.

Lesbophobia: Fear of, contempt of, or discrimination against LBQ+ people.

Masculine-presenting: Describes a person who adopts a visual aesthetic that is culturally coded or aligned with men or masculinity, which could include types of clothing, mannerisms, haircuts, and patterns of speech.

“Outing”: The act of disclosing an LGBT person’s sexual orientation or gender identity without their consent.

Queer: An inclusive term covering multiple identities, sometimes used interchangeably with “LGBT.” It is also used to describe divergence from heterosexual and cisgender norms.

Sex: Classification of bodies and people (often at birth) as female, male, or other, based on biological factors such as external sex organs, internal sexual and reproductive organs, hormones, and chromosomes.

Sex Worker: An adult who regularly or occasionally receives money or goods in exchange for consensual sexual services.

Sexual Orientation: A person’s sexual and emotional attraction to people of the same gender, a different gender, or any gender.

Sexual Violence: Any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting.

SOGIE: An acronym for sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression.

Transgender (also “trans”): Denotes or relates to people whose assigned sex at birth differs from their gender identity.

Transgender woman: Person assigned male at birth who identifies as a woman. Transgender women may also identify as lesbian, bisexual, or queer (LBQ+).

Transgender man: Person assigned female at birth who identifies as a man. Transgender men may also identify as lesbian, bisexual, or queer (LBQ+).

Transmasculine: A broad term used by people assigned female at birth who identify with masculinity, regardless of their gender identity. The term may be used by non-binary people, gender non-conforming people, transgender men, masculine-presenting LBQ+ people, and others.

Transphobia: Fear of, contempt of, or discrimination against transgender people.

Terminology

LBQ+ people include cisgender, transgender, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming people who identify as LBQ+. This report uses both “LBQ+ women” and “LBQ+ people,” to allow for the political reality that some people who identify as LBQ+ do not identify as women, but, at the same time, much of the discrimination and violence that LBQ+ people face is tied to their identities as women. So, too, is their access to women’s rights services, justice, and mechanisms. This section explains why and how Human Rights Watch chose certain terminology to express different ideas throughout the report.

Transgender LBQ+ People

While Human Rights Watch explicitly sought interviews with gender-nonconforming, non-binary, and transgender people who identify as LBQ+, this report does not provide an in-depth examination of LBQ+ trans people’s experiences from a gender identity perspective. Several recent Human Rights Watch reports have explicitly addressed transgender rights with a focus on gender identity.[36]

This investigation sought to analyze how and in what circumstances the rights of LBQ+ people are violated, centering LBQ+ identity as the primary modality for inclusion in the report. Gender-nonconforming, non-binary, and transgender people who identify as LBQ+ were naturally included.

Dozens of LBQ+ people, including cisgender women, interviewed by Human Rights Watch affirmed that trans people are central to the LBQ+ rights and justice struggle. Several interviewees used the acronyms LBT (lesbian, bisexual, and trans), LBQT (lesbian, bisexual, queer, and trans), or LBTQ (lesbian, bisexual, trans, and queer) to describe their activist movements and organizations in order to explicitly denote the inclusion of trans people. Others use one of these acronyms in recognition of the social, romantic, and political ties between cisgender LBQ+ women, trans men, and transmasculine people. Happy, a lesbian human rights defender from Tanzania, said:

We use LBTQ women to include trans women explicitly. Our leadership committee is two trans women, one gay man, and four lesbian women. Many who join our events use ‘butch’ first, because it’s what they find on the internet. They use ‘stud’ [a term more common among Black lesbians] once they find the actual community in real life in Tanzania. Sometimes in the process of doing self-awareness and -acceptance training, we find that people who used to identify as lesbians discover they are trans men. People need information to know who they are. In Tanzania, people do not have information about SOGIE. Our trainings help people understand who they really are.

In Tanzania, people will say “I feel like a man, but I don’t have a plan or finances to transition, so I consider myself a stud lesbian.” We explain that transition is not what matters, what matters is how you feel, and we refer them to other organizations which focus on trans men’s issues. When they find out they are trans, many stop saying they are studs. They don’t want to be stud because it is so associated with being a woman.[37]

Like Happy’s experience working with butches, studs, and trans men in Tanzania, across regions and languages, interviewees reported that the deep ties between LBQ+ women, trans men, and transmasculine people mean their spaces inherently blur the alleged divisions between cisgender and transgender identities.

The decision to use or discard identity labels, such as “butch” and “stud,” is personal. LBQ+ activists in different countries reported unique trends in whether trans men continued to use LBQ+ identity markers once they identify as trans men. In Tanzania, trans men stopped identifying as studs due to the dysphoric effect the term carries for transgender men (because it is “associated with being a woman”).[38] In Indonesia, the opposite is true, according to Tama, a human rights defender and co-founder of Transmen Indonesia. A 2022 survey that his organization conducted among 30 transmasculine people across the country found “education is still low related to the identity of trans men, which [results in a] still mixed identity of butch with transmen.”[39] The study noted that “many individuals” in the community “can't even tell the difference between masculine gender expression, lesbian sexual orientation, and gender identity as trans men.” [40] A review of dating app profiles further demonstrated a mix of lesbians and trans men who use both terms.[41] Indeed, at least two interviewees for this report identify as “lesbian trans men.”

Many use butch in English and trans laklaki for trans man. Jalalai can mean tomboy or trans man. We [trans men] have received some criticism from lesbians who said we were trying to claim their identity….

Talking specifically about queer women is okay. It is not inherently transphobic to specify when you mean LBQ+ women and not trans men. At the same time, we can admit and recognize that queer women and transmasculine people have the same base of oppression. In Indonesian bigger cities, we have three groups specifically for trans men. But Indonesia is big and spread out. For most of the country, trans men are always part of LBQT groups.

While Tama’s group in Indonesia and Happy’s group in Tanzania reported different identification trends, they share the assessment that lack of access to SOGIE education impacts how and when LBQ+ people choose to identify both their sexual orientation and gender. In all countries in which Human Rights Watch conducted research, it was clear that “LBQ+” and “trans men” are not mutually exclusive categories. This report uses the terms, phrases, and identities reported by interviewees to refer to each of them. Apparent inconsistencies are an intentional reflection of how and when people of many genders identify as LBQ+.

As noted in the Summary and will be seen in this report, the rigidly binary (and often violently enforced) gender boundaries outside of which LBQ+ people already live, regardless of their gender identity, may help to explain why the allegedly clear division between “cisgender” and “transgender” categories simply does not work for LBQ+ populations.

Masculine-Presenting LBQ+ People

During this research, Human Rights Watch found gender expression (as compared to either sexual orientation or gender identity) to be a frequent topic of discussion among interviewees, and one less explored in its relation to human rights violations. As such, sexual orientation (the original objective in a report on LBQ+ people) and gender expression (the identity interviewees frequently discussed) are centered in this report.

Several LBQ+ interviewees experienced human rights violations and abuses as a direct result of being masculine-presenting. For these interviewees, the difference between identifying as a trans man, butch lesbian, or non-binary queer woman was less central to their experience of violence and self than their experience as a masculine-presenting person.

In their own assessment, and in Human Rights Watch’s analysis, gender expression is critical to understanding violence against LBQ+ people and is prioritized in this report above categorizations related to gender identity. Many masculine-presenting people interviewed for this report reported a fluid gender identity that traverses the normative boundaries of “man,” “woman” or “trans”, and centered instead their experience of gender expression. This report, in keeping with an LBQ+-centered methodological approach to documentation, mirrors that focus on gender expression, and intentionally focuses on “masculine-presenting” LBQ+ people as rights-holders in some sections, in particular Section V. “Butches Get Punched”: Violence Against Masculine-Presenting LBQ+ People.

“Women and girls” and “Female”

Gender is distinct from sex assigned at birth. Many sources relevant to our desk research, however, used the terms interchangeably. Some international organizations and state bodies tracking “gender” parity or women’s rights using various equality indexes use the terms “women and girls” and “female” as synonymous with “sex assigned at birth.”

While a key aim of this report is to critique the presumed heterosexuality of all women and girls, in order to do this, we must draw upon existing work which, at times, has not recognized or acknowledged the existence and experience of queer and transgender women and girls.

To demonstrate the “LBQ+ research gap,” several chapters of this report cite existing women’s rights research that does not explicitly name LBQ+ women and girls. In reference to literacy rates, economic marginalization, discriminatory inheritance laws, and other systemic forms of discrimination that are experienced by people assigned female at birth, this report uses the categorizations and terms used by the organizations that collected the data.[42] Similarly, where relevant, this report uses “women and girls” in some specific cases to discuss specific barriers to accessing justice and resources, including education and literacy, that many LBQ+ people face as a result of being raised as “girls.”

Human Rights Watch recognizes that the use of “gender” as synonymous with “sex” has contributed to the major data gap vis-à-vis transgender people. There is a chronic lack of data available, for example, about the literacy rates of transgender youth, as well as other statistics indicating their access to rights and resources.

Methodology

This report maps human rights violations and abuses faced by LBQ+ communities to determine research and documentation gaps regarding LBQ+ rights. It aims to identify opportunities to render visible LBQ+ experiences in existing areas of human rights where they have been overlooked, and to carve out space for new formulations of LBQ+ rights on their own terms, regardless of whether they fit into preexisting categories of human rights research. As part of this, the report identifies critical areas in need of future investigation and key policy reforms in several fields, which have the potential to immediately and substantially improve LBQ+ access to a wide range of rights.

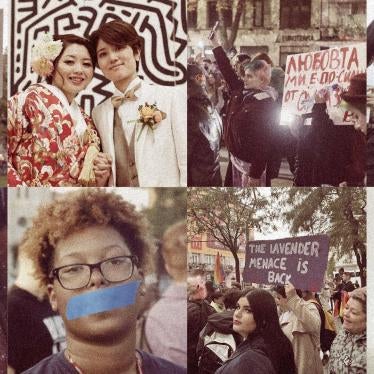

Human Rights Watch conducted remote interviews with 60 LBQ+ people in 20 countries: Argentina, Canada, Egypt, El Salvador, Hungary, Indonesia, Japan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Malawi, Mexico, Poland, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Tanzania, Tunisia, Uganda, Ukraine, and the United States. Six additional interviews were conducted in person with LBQ+ activists from Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Spain at the EuroCentralAsian Lesbian* Conference, held in Budapest from September 29 to October 1, 2022.

Interviewees ranged from 21- to 75-years-old. The majority of those interviewed were movement leaders, activists, and human rights defenders working at the local or national level. Most interviewees are experts in their field, and provided invaluable insight based on years of experience working on issues affecting LBQ+ people. Sixty-six interviews are not a representative sample of LBQ+ experience. Interviewees were selected primarily for their knowledge and expertise of LBQ+ issues in their communities, and for their ability to speak to the priorities, threats, and organizing goals of various LBQ+ movements around the world, to help direct future investigations and advocacy projects.

This includes both people who work explicitly on LGBT or LBQ+ rights, and LBQ+ people who work in other human rights areas, such as land, environmental, and indigenous rights; migrant rights and border justice; economic and racial justice; and humanitarian response. Other interviewees included LBQ+ individuals working in international human rights organizations, academics who have produced research specifically on the rights of LBQ+ people, international justice researchers, lawyers, and journalists. Human Rights Watch also spoke with the authors of Vibrant Yet Under-Resourced: The State of Lesbian, Bisexual & Queer Movements, the first study to analyze the extreme funding gaps facing LBQ+ movements.

The interviews were supplemented with desk research, including a review of research conducted by five organizations on the rights of LBQ+ people and trans men in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesian, French, and Spanish. The literature review was conducted online and primarily in English, an approach which inevitably privileges knowledge production that is written, published online, and in English. It inherently excludes and perpetuates the invisibility of other modalities, such as oral traditions and intergenerational storytelling, which are especially critical because formal, written documentation of LBQ+ rights violations and abuses represent only a fraction of the knowledge that LBQ+ communities hold about these experiences. To address this gap, subsequent sections of this report draw heavily on and prioritize the analysis of the 66 LBQ+ people and rights experts interviewed for this report.

Finally, to aid in the development of LBQ+ research methodologies, the researcher reviewed Human Rights Watch documentation manuals, interview guides, and thematic toolkits for researchers, as well as documentation manuals produced by feminist groups including the Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID), the Mesoamerican Initiative of Women Human Rights Defenders (IM-Defensores), JASS Just Power, Nazra for Feminist Studies, the Regional Coalition for Women Human Rights Defenders in the Middle East and North Africa (WHRD-MENA), and the Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition (WHRD-IC).

I. Background

This section maps existing research on the rights of LBQ+ people by human rights organizations, select academics, and donors. In addition to country specific reports, the literature review found research on LBQ+ experiences of poverty and economic marginalization, attacks on LBQ+ people who are human rights defenders, and the lack of funding for LBQ+ movements.

This section also introduces overarching concepts for researchers and other stakeholders to consider in order to close the research, advocacy, and policy gap. Specifically, it analyzes how LBQ+ exclusion from research is perpetuated by persisting misconceptions of LBQ+ “invisibility;” normative, gendered conceptualizations of “outness;” and incorrect assumptions that LBQ+ people primarily suffer violence in the so called “private sphere” and at rates lower than queer men and boys.

Human Rights Research Gap

LBQ+ people’s experiences are underrepresented in human rights investigations, reports, and advocacy campaigns. The scoping and consultations with experts in multiple human rights areas found few documents that explicitly position LBQ+ people as rights-holders subjected to violations under international human rights law.

At the national level, few human rights reports have documented and analyzed violations of LBQ+ people’s rights. These include reports on Burundi,[43] Iran,[44] Iraq,[45] Kenya,[46] and lesbian asylum claims in the United States.[47]

At the regional level, civil society organization have published reports on:

- violence against lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (LBT) people in Japan, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka;[48] another presented accounts of queer women from Algeria, Egypt, and Sudan;[49]

- violations and abuses against lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender (LBQT+) women in the North Caucuses;[50]

- lesbophobic violence in Europe and Central Asia;[51]

- and LBQ+ rights in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico, mapped in a series of reports issued by a Latin American collective.[52]

At the global level, a 2016 report analyzed for the first time how anti-homosexuality laws specifically target and impact lesbian and bisexual women and girls.[53]

While several of these reports discuss the criminalization of same-sex relations as one of the key drivers of violence against LBQ+ people, many additionally center other restrictions on women’s freedom, including freedom of movement, bodily autonomy, access to education, labor rights, and financial independence as critical components of LBQ+ lives. A report on LBT experiences of violence in Asia, for example, found that the advancement of LBQ+ rights depended on the removal of “obstacles from both the public and private spheres that prevent all women (female bodied, gender variant, lesbian, bisexual) and female-to-male transgender men from enjoying violence-free lives.”[54] Research that is conducted specifically into the lives of LBQ+ people–rather than LGBT rights more broadly–invariably presents a more complex picture of rights and freedoms, demonstrating the need for future research in this area.

LGBT rights researchers have long noted that testimonies from LBQ+ and transmasculine people are more difficult to source than those from cisgender gay men and transgender women.[55] [56] [57] This gap also results from women’s rights research that presumes women research subjects are heterosexual, which often precludes any potential investigation of the unique experiences of LBQ+ people in broader issues affecting women and girls, such as domestic violence, forced marriage, gendered poverty, maternal mortality, and reproductive rights.[58] LGBT and women’s rights researchers alike frequently choose to examine issues that are not those most affecting queer women’s lives.

Maps and databases covering LGBT rights and laws around the world typically illustrate which countries criminalize homosexuality, allow for same-sex marriage, have nondiscrimination policies that explicitly name sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (SOGIE) as protected categories, and, in recent years, increasingly include information on which countries allow for legal gender recognition.[59] [60] [61] While important, these topics do not address the fundamental lack of power, autonomy, and control in many women’s lives that limits their expression of sexuality. For example, LGBT rights mappings rarely if ever include laws related to women’s property rights, inheritance rights, and rental rights even though they are critical to LBQ+ people’s ability to have physical spaces to meet romantic partners, raise families, and organize in collectives.[62]

There is also a stark absence of documentation of LBQ+ experiences of poverty, labor rights, environmental crimes, climate change, reproductive justice, indigenous LBQ+ peoples’ rights, police violence, and conflict. Representation is better in disability rights studies and migration—in no small part due to the vocal activism of LBQ+ activists in these spaces—but there remains room for further investigation in those fields.[63] [64]

Consultations with researchers in these various human rights areas have indicated that the gap in knowledge production vis-à-vis LBQ+ rights within their specific area of focus is not an intentional silencing of the LBQ+ experience. Rather, it reflects the persistent belief that sexuality is not relevant to many investigations, and the presumption of heterosexuality in human rights subjects. In addition to this methodological gap, queer and feminist thinkers have identified a range of other factors contributing to the underrepresentation of LBQ+ people in human rights investigations, including:

- the siloing of human rights areas that limits analyses of LGBTI+ peoples’ rights to reports specifically focused on this issue;[65] [66] [67] [68]

- patriarchal systems, the devaluation of female sexuality, and the lack of legitimacy afforded to the romantic and sexual relationships of LBQ+ women;[69]

- risks and barriers to women and non-binary people’s engagement in the public sphere, including male guardianship laws, stigma, family pressure, sexism and gender bias in urban planning, and cultural conceptualizations of women’s reputations as closely tied to family honor;[70]

- the historic focus on HIV/AIDS programming that led to more funding and visibility for gay men’s groups and to the persistently male-dominated leadership of international, regional, and local LGBTI rights organizations;[71] [72]

- the focus on the decriminalization of same-sex relations and the removal of colonial era anti-homosexuality laws as the central issue of LGBT struggles;[73]

- homophobia, transphobia, biphobia, and lesbophobia within women’s rights and feminist movements;[74]

- compulsory heteronormativity, which positions LBQ+ people outside society’s conception of womanhood and personhood by virtue of not being socially, financially, legally, religiously, and/or culturally recognizable via heterosexual partnerships;[75] [76]

- assumptions about sexuality, including those made on the basis of partnership or marriage, and the lack of acknowledgement that women and non-binary people of all sexualities can be compelled or forced to enter heterosexual partnerships and marriages;[77]

- domestic violence, coupled with the popular notion that much of the violence perpetrated against women happens in the private sphere and the corresponding notion that all familial violence is private;[78]

- economic marginalization and a corresponding lack of access to financial, legal, and other resources for LBQ+ people to document and visibilize their issues.[79]

Academic Research

Recent academic research into the health, social welfare, and economic marginalization of LBQ+ people has provided strong thematic guidance for areas to address in future human rights investigations and can help close the LBQ+ research gap in the human rights field. This is especially true for studies that explicitly name and address the underrepresentation of LBQ+ issues in their field. For example, Intersectionality and the Subjective Processes of LBQ Migrant Women: Between Discrimination and Self-determination (2021) explored the lack of analysis afforded to the sexualities of migrant women relative to migrant men in Italy:

On the one hand, studies have increasingly focused on migrants’ sexuality, particularly on the condition of gay and bisexual males: Carnassale (2013), Ferrara (2019), Masullo (2015a; 2015b). On the other hand, however, sociological literature paid much less attention to the sexuality of migrant women, with a relative absence of studies – both qualitative and quantitative – on non-normative sexualities. Rather than showing a lack of interest on the issue, this absence refers to the general difficulty of studying women with non-normative sexual orientation. Considering only Italian studies, for example, those on lesbians (net of ethnic differences) are significantly less numerous than those on gays and lesbians appear to be markedly more invisible than the male population (Masullo, Coppola, 2020).

In the US, the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law issued two extensive reports concerning LBQ+ lives in 2021 and 2022 that, similarly, intentionally addressed the LBQ+ research gap. The first, System Involvement Among LBQ Girls and Women, found that LBQ+ women and girls of color are overrepresented in both carceral and foster care systems: “Of the more than 10 percent of girls in foster care who identify as lesbian, bisexual, queer and questioning, nearly 90 percent of them are girls of color and more than 30 percent of them are Black.”[80]

When discussing the risks associated with high rates of incarceration, due to a lack of current research on violence against LBQ+ people in prison, this report refers to evidence from past studies on violence against transgender people in prison.

The second UCLA study, Health and Socioeconomic Well-Being of LBQ Women in the US, is the largest, most comprehensive known research on the rights of LBQ+ people. Though focused exclusively on the US, the findings and suggestions for future research resonate internationally. This is in part because the report takes an intentionally “expansive” view of what constitutes well-being, in line with the methodological reforms suggested by more than a dozen LBQ+ advocates around the world who were interviewed for this report. The study relied on a wide range of datasets and national population surveys to analyze LBQ+ women’s experiences of discrimination, health, housing, homelessness, sexual violence, mental health, reproductive health, system involvement, and resilience. It found that LBQ+ women (cis and trans) make up 55 percent of the US LGBT population, with 7 million women and 3 million girls identifying as LBQ+ and LBQ+ or questioning, respectively. Among its key findings, nearly one-fifth of LBQ+ women reported wanting children but were not able to have them; LBQ+ women were more likely (90 percent) to never visit LGBT centers for health care compared to gay, bisexual and queer men (77 percent); and nearly one-third of LBQ+ women identified their health as “poor” compared to one-fifth of heterosexual women. The study also found that twice as many LBQ+ women (46 percent) have been diagnosed with depression as straight women (23 percent), and a staggering 44 percent of LBQ+ or questioning girls reported having considered suicide in the last year, compared to 18 percent of straight girls, 13 percent of straight boys, and 32 percent of gay, bisexual, queer, and questioning boys.

This data supports calls from LBQ+ advocates in Canada, Indonesia, Lebanon, Malawi, Tanzania, and Tunisia to produce more and better research into the mental health of their communities. Black and brown diaspora LBQ+ leaders have specifically called for analyses of the linkages between compulsory outness in white-led Pride organizations and rates of depression and anxiety among queer Black and brown women in those spaces.

Suicide rates in our community are extremely high, but we don’t have any research or concrete proof of this. Most queer South Asian women I know have attempted it at least once. We are trying to do advocacy with bigger Pride orgs about how they can be more inclusive and less dangerous for us, but research into the immense mental stress we’re under would help us prove it and be taken more seriously.[81]

Poverty and Economic Marginalization

[A lesbian sex worker couple in our community] lives about 20 mins outside of Centro. In the area they’re in now, there are a lot of raids. Police come to very impoverished areas. They have to rent from gangs in this area because it’s the only place they can afford a house big enough for the older and younger members of their families that they, as women, are expected to care for. Gangs occupy the houses without warning and stay however long they want. The two women make very little money, and being poor basically means expecting a police raid.[82]

– Rosa, lesbian and sex worker rights defender from El Salvador

Poverty among LBQ+ women, though not always named explicitly as a human rights violation, is a consistent backdrop to the majority of existing research on violence against LBQ+ people. LBQ+ people—who may be women, queer, in relationships with women, in relationships with queer people, members of racially and ethnically marginalized groups, and indigenous—exist amid multiple layers of economic marginalization, as members of many groups subjected to structural forms of discrimination that intersect and multiply.[83] However, economic data that disaggregates by sexual orientation is rare; studies and reports that explicitly name the precarious position of LBQ+ women have tended to focus on the US, on the UK, and at the “international” level, such as UN reports that cover LBQ+ poverty in general terms. A significant gap in published research into LBQ+ poverty exists at both the country and regional levels in most parts of the world.[84]

A 2009 study found that lesbian couples in the US faced poverty at a higher rate than heterosexual married couples or gay-male couples.[85] In 2013, an updated version of the same study found that children in same-sex couple households were almost twice as likely to be poor as children in married different-sex couple households. It also determined that the rate of poverty among same-sex female couples is double that of male same-sex couples.[86] According to a 2019 UN report addressing economic marginalization and the inclusion of LGBT communities:

Combined with gender-based discrimination against women, where women face a pay gap and hold the burden of unpaid care work, lesbian women facing discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity are often even worse off. Pay gaps translate to smaller contributions to pension schemes and therefore to increased poverty in retirement.[87]

Paying an Unfair Price: The Financial Penalty for LGBT Women in America (2015) found that discrimination against LBQ+ women in jobs, families, and health negatively impacted their economic security. Unsafe work environments and discrimination in hiring led to lower pay and less advancement, and discrimination in insurance and unequal access to reproductive health care led to long-term, costly health complications that made finding work even more difficult.[88] Meanwhile, Disaggregating the Data for Bisexual People (2018) found bisexual women were in a particularly precarious economic position, with bisexual women ages 18-64 less likely than lesbian women to have a job.[89]

Though not specifically focused on LBQ+ women, a 2021 study into LGBT experiences in the construction industry in the UK has provided some of the most illustrative findings on how LBQ+ people and cisgender gay men have experienced homophobia differently and how homophobia has directly impacted the economic security of LBQ+ women in unique ways:

For women [compared with cisgender gay men], gender is a bigger obstacle than sexuality for career. Cis-female participants (i.e. those female at birth) identifying as lesbian stated that they felt their gender had more of an impact as to how they were treated at work, in comparison to their sexuality. One participant said, “‘I can hide I’m gay, but I can’t hide that I'm a woman.” The pervasiveness of gender discrimination was also underlined during the stakeholder workshop discussions. The domination of the construction by white heterosexual males, particularly at the very top of companies was posited as a more substantial barrier to their career progression than their LGBT identity. The term ‘old boys club’ came up repeatedly in the interviews to describe gender-related issues within the industry.

These findings illustrate one aspect of the multiple forms of economic marginalization that LBQ+ women face. Another factor–workplace violence against LBQ+ people–was repeatedly confirmed in the consultations conducted for this report, including by activists in Argentina, Indonesia, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Tunisia, and the US (see Section VI. Violence and Discrimination at Work).

Multiple forms of economic marginalization have contributed to the strong presence of LBQ+ people in sex work in several countries, including Ghana, El Salvador, and Tanzania, according to both the literature review and interviews.[90] For a 2018 report on abuses against LGBT people in Ghana, one 28-year-old lesbian woman, told Human Rights Watch:

The problem in Accra is that LGBT people can’t get work. Nobody wants to give them jobs. Also, when the family finds out, they don’t pay your school fees, so you are uneducated. There is also no support to learn a trade. When both lesbian partners don’t work, the femme partner is expected to date and sleep with men to get money—sometimes they both must do sex work to survive.[91]

By contrast, two interviewees said that in El Salvador, sex work is one of the few forms of work available to masculine-presenting LBQ+ people, who experience rampant hiring discrimination because of their gender expression.[92] The connection between economic marginalization, sex work, and masculine gender expressions is explored in Section V. “Violence Against Masculine-Presenting LBQ+ People.” While little research exists on the experiences of LBQ+ sex workers, both the background scoping and interviews suggest that an investigation into their unique experiences of violence is urgently needed.

Attacks on Human Rights Defenders

Between 2017 and 2022, there has been more documentation and analysis of the risks, threats, and attacks on LBQ+ activists as a subset of feminist organizing and women human rights defenders (WHRDs). At the regional and local levels, reports and statements on LBQ+ human rights activism[93] have been published in Kenya (2018),[94] Sub-Saharan Africa with case studies in Cameroon and Togo (2013),[95] South Africa (2019) following the Global Feminist LBQ Conference,[96] and on the “state of lesbian organizing” in the EU and accession countries (2020).[97] At the global level, several reports documenting attacks on feminist organizing more broadly have centered the experiences of LBQ+ leaders. Such reports include: Rights Eroded: A Briefing on the Effects of Closing Space on Women Human Rights Defenders (2017);[98] The State of Intersex Organizing (2nd edition) and The State of Trans Organizing (2nd edition) (2017);[99] and Standing Firm: Women and Trans-Led Organisations Respond to Closing Space for Civil Society (2017).[100]

LBQ+ leaders are present in a wide range of social movements, and it follows that organizations focused on the promotion and protection of WHRDs have analyzed[101] the linkages between lesbophobia, attacks on feminist movements, and fear mongering around “gender ideology.” [102] However, while these reports discuss anti-LBQ+ animosity and violence as a threat to feminist movement-building, the documentation or analysis of anti-LBQ+ violence itself is not their main objective. For example, one report found the demonization of queer people to be detrimental to feminist movements;[103] another found that attacks on lesbians have a detrimental effect on women’s organizing and identified lesbophobia "and its influence in the reduction of civic space” as a critical area for future research.[104] This means that organizations and funders combatting the “shrinking civic space for civil society” phenomenon must also concern themselves with addressing homophobia and attacks framed in terms of “gender ideology”.

Many of the activists interviewed … experience closing civil society space as being driven, at least in part, by an increase in state-sponsored rhetoric that prescribes and enforces narrow patriarchal and heteronormative gendered behaviour and sexual identity.[105]

Funding Challenges

LBQ+ movements are radically underfunded, receiving only a small portion of LGBT funding globally and an even smaller fraction of women’s rights funding globally.[106] According to one LBQ+ activist, “We sit firmly in the LGBT portfolio of almost all our donors. Women’s rights foundations do not contact us. They see us, queer women, as fundamentally a gay issue.”[107]

Vibrant Yet Under-Resourced (2020), by feminist organizations Astraea and Mama Cash, is the groundbreaking result of a global analysis of funding for LBQ+ communities. The authors collected data from 378 activists in 97 countries and 67 donors and analyzed LBQ+ activists’ priorities, the critical lack of targeted funding for their work, and mapped where donor efforts aligned with LBQ+ communities’ strategies for creating new feminist futures. The report found that LBQ+ groups did not have the budgets, savings, or access to the external support needed to implement their creative, diverse movement strategies:

The median budget for LBQ groups in 2017 was $11,713 USD. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of LBQ groups operated on annual budgets of less than $50,000 per year; in fact, approaching half (40%) reported an annual budget of less than $5,000.

One-third (34%) of groups received no external funding, and for nearly half (48%) of all groups, external funding did not exceed $5,000.

The majority of LBQ groups have few, if any, paid staff and are heavily reliant on volunteers. One-quarter of all groups have no full-time staff (28 percent), and another 25 percent have just one or two staff full-time members.[108]

Other key findings include that LBQ+ groups faced significant barriers to accessing funding, which impacted their access to rights, including their access to justice, and that two strategies central to LBQ+ organizing—knowledge production and well-being—are critically underfunded.

In 2017, 89% of donors funded [LBQ+] community, movement, and network building, 77% funded advocacy, and 73% funded capacity building — all key activist strategies. However, other strategies central to LBQ organizing were funded to a much lesser extent. Less than half (43%) of donors in our sample funded research and knowledge production, while direct services, including mental health and well-being, were funded by the fewest donors (32%).[109]

Consultations for this report confirmed the importance of immediately increasing the amount of funding available for LBQ+ groups to collaboratively produce knowledge (reports, videos, investigations, visualizations), as well as to train and deploy mental health and well-being services in their communities.

Concepts That Perpetuate LBQ+ Exclusion

Several misconceptions about LBQ+ people and their experiences of discrimination and violence fuel their exclusion from research: (1) the assumption that lesbians are “invisible,” by nature or by choice; (2) “outness” is the only path to queer liberation, and all queer people should want to be “out,” (3) LBQ+ people primarily experience violence in the “private sphere” and not in public; and (4) LBQ+ people are safer and freer from violence than queer men and boys.

“Lesbian Invisibility”

The phrase “lesbian invisibility” refers to the devaluation of the identities, experiences, and contributions of LBQ+ people in the arts, politics, social movements, and a wide range of other documented histories as discussed above.[110] In the human rights field, addressing the radical gap in documentation of LBQ+ experiences is critical to protecting the rights of LBQ+ people. However, speaking of lesbian invisibility begs the question: Invisible to whom?

When the phrase is deployed uncritically and without explicit commitment to rectifying that gap, lesbian invisibility assumes LBQ+ issues are, in fact, hidden, harder to document, and more complicated to access.[111] It elides the intentional devaluation of women’s issues, including in queer spaces, and normalizes the primacy placed on cisgender men as the “natural” subject of rights, research, and investigation. Colloquial references to lesbian invisibility treat it as a naturally occurring phenomenon and erode the responsibility of researchers, advocates, and funders to recognize and seek to address the systemic nature of discrimination and violence against LBQ+ people. Accordingly, the phrase functions as an excuse not to advocate for LBQ+ victims of human rights violations and abuses.

Several interviewees questioned an assumption often made by researchers and NGOs that queerness is “too dangerous” or “too complicated” of an issue to discuss publicly or to even ask about in interviews during fact-finding research trips. While it is true that LBQ+ human rights defenders who are visible advocates for their communities face immense, sometimes life-threatening risks for doing so (see Chapter X. LBQ+ Human Rights Defenders), LBQ+ activists reported being stripped by researchers, reporters, NGOs, and others of their agency and decision-making power to decide to tell their stories. LBQ+ activists in Indonesia, Tanzania, and Tunisia spoke of experiences with supposedly allied state institutions who told them it was “too dangerous” to issue statements supporting lesbian groups being threatened with sexual violence, even though the community themselves had asked for public solidarity. Non-LBQ+ researchers spoke of instances when they chose to discard accounts from LBQ+ victims for fear that “outing” them would increase their risks. These accounts have indicated how human rights researchers, advocates, and allied advocacy targets all play a role in imposing the infantilizing notion that being “out” is too dangerous for LBQ+ partners, victims, and interviewees, thus perpetuating the alleged invisibility of LBQ+ communities and their issues.

As detailed later in this report, governments also contribute to “lesbian invisibility” and the human rights violations that result in several ways, including by failing to explicitly name LBQ+ people in services, programs, social support, laws, and policies aimed at the promotion and protection of women’s rights. This omission has created barriers to accessing justice, health care, and support for LBQ+ victims of violence and discrimination, because they are not clearly named as rights-holders in, for example, anti-discrimination labor policies,[112] SGBV programs, or health care guidelines.[113] (For more on how the lack of explicit LBQ+ inclusion in women’s rights laws and policies negatively impacts LBQ+ people, see Section IV. “Property Rights,” Section X. “Health,” and Section XII. “Justice”).

“Outness”

We aren’t trying to force people to come out of the closet. Before colonialism, queerness was very “out.” It’s recolonizing to be asked to “come out” by white people with no awareness of how dangerous that is for us at home, for the ways in which colonists forced our queer ancestors into this closet they now want us to bust out of. For queer South Asian women, we want to come out to people we feel safe with. But the idea is pushed on us that we need to come out to everyone.[114]

– Sonali Patel, founder of the Queer South Asian Women’s Network