Map

Summary

We know … that we are clandestine migrants, illegal migrants. We know we don’t have [some] rights. But we know we have human rights. Human beings need to be respected. We can’t be mistreated. – André P., 27, Guinea

André P. is one of hundreds of sub-Saharan African migrants who live at any given moment in makeshift camps in the forests of Morocco. Like many of his fellow migrants, André, who traveled by foot and car over hundreds of miles from his home in Guinea, considers Morocco simply a way station on his journey to Europe. Sub-Saharan African migrants leave their countries for a variety of reasons: poverty, family and social problems, political upheaval and civil conflict, and fear of persecution—but they uniformly describe their goal as reaching Europe to create a better life.

Many migrants stay in campsites around cities near Morocco’s borders with Algeria and Spain’s north African enclave of Melilla. The migrants lack basic necessities living outdoors where they sleep in homemade tents and are exposed to cold and rain. Migrants with disabilities face even greater hurdles in accessing food, water, and toilets. Many migrants, having saved up their meager resources to escape poverty, persecution, or hopelessness, find themselves vulnerable to abuse rather than finding safety upon arriving in Morocco.

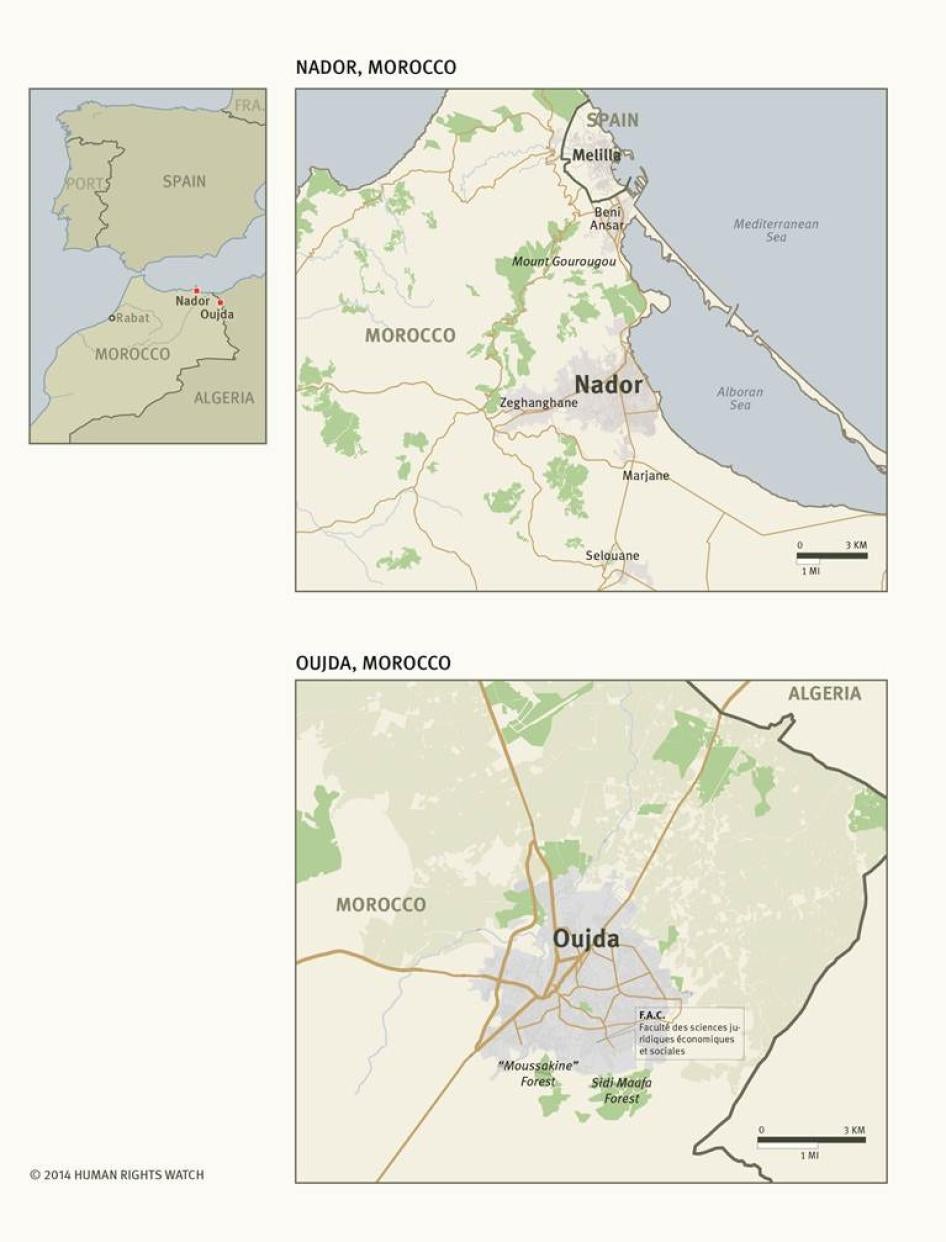

Human Rights Watch has documented cases where Moroccan police beat these migrants, deprived them of their few possessions, burned their shelters, and expelled them from the country without due process. Morocco’s government insists that the police were enforcing national immigration policy and denied that the police perpetrated violence against migrants. However, statements from the migrants, corroborated by other sources, suggested many cases of abuse of sub-Saharan Africans in Morocco. This report focuses on the treatment of sub-Saharan African migrants currently in Morocco’s northeastern region, between the Algerian border and the Spanish enclave of Melilla. Human Rights Watch interviewed 67 sub-Saharan African migrants living in unofficial campsites in this region around the cities of Oujda and Nador in December 2012, and another two sub-Saharan African migrants in Melilla.

Forty-two of the 67 migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch in December 2012 described what they said were frequent police raids. Some of them said that during the raids the police arrested male migrants without charge, destroyed migrant shelters and personal property, and sometimes stole migrants’ valuables.

Thirty-seven of the 67 migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that Moroccan security officials also forcibly expelled them at the Moroccan-Algerian border without taking the appropriate legal measures, which require the police to assess whether the migrants had proper documentation, such as visas that would enable them to be in Morocco for three months; were seeking asylum to escape persecution; or were refugees with permission to remain in Morocco. Security forces also denied the migrants basic procedural rights under international law, including the right to consult a lawyer, the right to be notified of their impending expulsion, the right to appeal such an order, and the right to be assisted by an interpreter, if necessary. The security forces committed these abuses against regular migrants, as well as members of groups entitled to special protection under national and international law, such as children, pregnant women, asylum seekers, and recognized refugees.

In the 1990s, Morocco became increasingly popular as a transit country for sub-Saharan Africans. The Moroccan government has coordinated security measures and border management with European Union (EU) member states, especially Spain, since the 1990s, and the country has become an important partner in EU efforts to curb the number of migrants reaching European shores as part of what has been described as the “externalization” of EU migration policy. EU states have a particular interest in protecting entry into the Spanish enclaves, Melilla and Ceuta, as parts of the EU that are on the southern side of the Mediterranean Sea. Some argue that the introduction of Morocco’s 2003 law on immigration (Law 02-03) was a response to EU pressures for stronger migration controls in Morocco.

Morocco and Spain’s coordinated efforts have at times resulted in violence against migrants and expulsions from the Spanish enclaves to Morocco. Reports from nonprofit organizations and the media indicate that since December 2011, the Moroccan authorities have tightened pressure on sub-Saharan migrants, raiding areas where they are known to live, arresting migrants suspected of being undocumented, and conducting collective expulsions of migrants at the border with Algeria.

Most migrants enter Morocco either via Mauritania or by transiting through Niger and then Algeria. They largely choose to settle in Morocco, at least temporarily, because of its proximity to Europe. Via the Algerian town of Maghnia, many migrants who enter Morocco first reach the city of Oujda on the other side of the border. They then often try to make their way to Nador, a coastal city that is located 15 kilometers from the Spanish enclave of Melilla. Moroccan and Spanish border patrols monitor the perimeters of Melilla and Spain’s other enclave on the southern Mediterranean coast, Ceuta, to prevent the migration of undocumented migrants.

The number of irregular migrants currently in Morocco is not known with certainty, but estimates range from 4,500 to 40,000. On November 11, 2013, the Ministries of Interior and Migration Affairs jointly announced a one-time program to regularize six categories of migrants during 2014, at which time they estimated the population of irregular migrants to be between 25,000 and 40,000. Previously, the Moroccan Ministry of the Interior had estimated the number of undocumented migrants to be between 10,000 and 15,000 as of 2012. Others have considerably lower estimates; Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) determined in a 2010 survey that there were approximately 4,500 undocumented migrants in Morocco. According to 2013 MSF figures, there are between 500 and 1,000 migrants in Oujda and between 500 and 1,000 migrants in Nador.

To cross from Nador to Melilla, migrants who lack legal authorization to enter the Schengen Area (an area comprising 26 European countries with no internal border controls) must overcome three tall razor-wire fences separating Morocco and Spain or they might take an inflatable raft or boat from Moroccan waters to Melilla or across the Mediterranean. (Although Melilla and Ceuta are part of the Schengen Area, as they are Spanish territories, additional border checks still take place for any further sea or air travel to mainland Spain or other European destinations.) However, this does not deter migrants from attempting to reach the enclaves because they hope they might be transferred to mainland Spain once inside the enclaves.

Human Rights Watch interviews suggest that both Moroccan Auxiliary Forces and the Spanish Guardia Civil have used excessive force against migrants trying to enter Melilla. The Guardia Civil summarily removed migrants who entered Melilla and handed them over to Moroccan border patrols at the Melilla-Morocco border, at which point the Moroccan authorities beat the border crossers, including children. Migrants who were expelled from Morocco to Algeria reported similar abuse at the hands of Moroccan and Algerian authorities, who, the migrants said, used force—or the threat of force—at the border.

For example, Frank D., who was 17 years old at the time of the interview, left Cameroon after his parents died to find a way to sustain himself. After a six-month journey traveling through Niger and Algeria, he reached Morocco. He tried to climb the fence around Melilla but cut himself on the razor-wire and fell back onto the Moroccan side. Moroccan border guards arrested him. Frank said that the guards beat and injured him with wooden batons, even though the fall had stunned him and he was not resisting or trying to escape. The police took him to the hospital, where he remained for two days under medical care. He was then released on crutches, put on a bus, and taken to Oujda to be expelled across the Morocco-Algeria border. Frank said he was not allowed to see a lawyer, use the services of an interpreter, gain information regarding the deportation decision against him, or appeal the decision. The authorities also disregarded the special rights and protections that attach to unaccompanied migrant children: they conducted neither an age determination nor family tracing for Frank nor assigned a guardian to represent his interests. Frank, in other words, was expelled in contravention of his right to due process, along with other violations of his basic rights.

While Morocco has the right to police its borders and enforce a legal regime for the processing of migrants, it must not engage in cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of migrants, beating them, robbing them of their possessions, and summarily destroying their makeshift shelters. Morocco also does not have the right to expel migrants without due process. In addition, Morocco owes a special duty of care to unaccompanied migrant children, ensuring that these children are protected from abuse and exploitation. Human Rights Watch finds the violence endured by some migrants at their informal settlements, and as they attempt to travel to Spain, amounts to excessive use of force that at times rose to the level of inhuman or degrading treatment, in violation of human rights law.

In September 2013, the Moroccan government announced it would implement a new migration and asylum policy, based on a set of recommendations formulated by the National Human Rights Council (CNDH) in September 2013 and endorsed by King Mohammed VI. The CNDH report highlighted human rights abuses against migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees in Morocco. While noting that the authorities have the right to control the entrance and the stay of foreigners; to protect the security of the national territory; and to fight against smuggling of migrants, trafficking in persons, and organized crime; the CNDH also called on the government to respect Morocco’s constitution and international commitments regarding the rights of refugees and asylum seekers, migrants, and victims of human trafficking. Despite Moroccan authorities’ political commitments to a new migration and asylum policy, it was too early to assess how fully the government has implemented the CNDH’s recommendations at the time of the publication of this report.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Moroccan government to remedy the violations delineated in this report as part of its new migration policy. The government should end the use of excessive force against migrants, stop the forced returns and expulsions of migrants without due process, and respect the rights of refugees and asylum seekers who wish to lodge a refugee claim. Morocco should, as party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, respond appropriately to unaccompanied children who enter Morocco by ensuring that the best interest of the child is considered and that procedural safeguards are in place to guarantee that age determination procedures and family tracing occurs, as well as providing guardians, legal assistance, and social assistance to unaccompanied migrant children.

Human Rights Watch also calls upon the Algerian government to stop its border security forces from violently and summarily pushing back migrants expelled by Morocco at the border.

Human Rights Watch urges the Spanish government to ensure that migrants are not arbitrarily removed, including at the border. In addition, Human Rights Watch asks the European Commission to investigate and monitor Morocco’s treatment of migrants who are attempting to cross Morocco into EU territory and ensure that any cooperation between the EU and its member states, and Morocco is in accordance with EU and international human rights standards. Human Rights Watch further calls on the EU and its member states to provide support to develop Morocco’s ability to fairly consider asylum claims and to implement the integration strategy planned for refugees and migrants who will benefit from the announced regularization procedure to the extent that it is respectful of their human rights.

Recommendations

To the Kingdom of Morocco

To the Ministry of the Interior and to the Ministry of Justice

Instruct security forces to:

- Refrain from using excessive force against migrants at the border with Melilla in line with the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials. Minimal and proportionate force should only be used as necessary when no alternatives exist.

- Refrain from using force against migrants after they have been detained except when strictly necessary for the maintenance of security and order within the detention facility, or when personal safety is threatened, and only to the extent necessary to achieve a legitimate purpose and when other means are not effective.

- Hold accountable any officers who fail to uphold the law and violate migrants’ rights to physical integrity.

- When carrying out evictions, including the destruction of makeshift migrant camps, follow appropriate judicial procedures, provide adequate notice, and allow for a timely appeals process.

- Prosecute or otherwise discipline police and security officials who steal or destroy migrants’ possessions during raids of makeshift migrant camps.

- Carry out all confiscations of migrants’ property according to the law and provide migrants with receipts for every confiscated article so they can be returned accordingly.

- End arbitrary and summary expulsions.

- Ensure that deportations of undocumented migrants who are not in need of international protection are conducted in dignity in accordance with international norms.

- Ensure that summary forced returns of refugees and asylum seekers do not take place by issuing orders that officers respect UNHCR-issued documents to refugees and persons of concern.

- Refrain from expelling unaccompanied migrant children, pregnant women, and members of other vulnerable groups that are protected by international and national law and hold to account any officers who expel such persons.

- Respect the right to family life of all persons, and refrain from separating children from their parents.

- Ensure that detained migrants, especially pregnant women, receive adequate and appropriate health care while in custody, including postnatal care for new mothers.

- Protect survivors of sexual violence and provide them with medical and psychological support.

- Sensitize all security personnel likely to come into contact with migrants to the rights of migrants, specifically to the rights of refugees, asylum seekers, pregnant women, children (including unaccompanied children), and persons with disabilities.

To the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation

- Establish and implement a fair and effective national asylum system.

- Develop a system for the fair and legal processing of irregular migrants.

- Continue to facilitate the timely voluntary repatriation of migrants who wish to return to their country of origin.

To the Ministry of the Interior

- Establish reception centers for asylum seekers to ensure their basic needs—including shelter, nourishment, and hygiene—are met while their claims (or, for children, best interest determinations) are being processed.

To the Ministry for Social Development, Family and Solidarity

- Ensure that unaccompanied migrant children are provided guardians, legal assistance, and assistance with their basic needs, including shelter, nourishment, and hygiene, while their best interest determinations are being processed.

- Identify, in cooperation with UNHCR and relevant partners, persons with disabilities and their protection and assistance needs.

To the Algerian Government

- Ensure that border security enforcement officers only use minimum and proportionate force as necessary when no alternatives exist if they wish to prevent migrants from entering Algerian territory at the border with Morocco in compliance with the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials.

- Instruct border security officials to refrain from using force against children and to screen for unaccompanied children when engaging in border enforcement activities.

- Conduct deportations of undocumented migrants not in need of international protection in accordance with international norms, respecting their right to due process, and allowing access to counsel, interpreters, and an opportunity to appeal decisions.

To the Spanish Government

- Stop the forcible return of undocumented third country nationals and stateless persons to Morocco until such time as Morocco demonstrates it is capable of systematically protecting asylum seekers and refugees and providing humane treatment for migrants, including by refraining from abusing them and halting forced collective returns to Algeria.

- Ensure that the Guardia Civil engaged in border enforcement activities only use minimum and proportionate force as necessary when no alternatives exist in compliance with the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials.

- Instruct the Guardia Civil to refrain from using unlawful force against children and to screen for unaccompanied children when engaging in border enforcement activities.

- Implement the 2010-2014 European Union Action Plan on Unaccompanied Minors to ensure their protection and taking into account their best interest.

To the European Union and Member States

- EU member states should refrain from returning third country nationals to Morocco under existing bilateral readmission agreements, or otherwise until Morocco meets international standards with respect to the human rights of returned migrants, and demonstrates the will and the capacity to provide effective protection to asylum seekers and refugees.

- EU member states and the EU should refrain from signing any new readmission agreements with Morocco until it demonstrates that migrants will not be subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment, denied the right to seek asylum, or subject to refoulement if they are readmitted into Morocco.

- The European Commission should cooperate with other EU bodies, including the European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs, to monitor and evaluate existing readmission agreements between Morocco and EU member states and their compliance to human rights standards.

- The European Commission should monitor implementation of existing bilateral readmission agreements, including assessing whether the right to seek asylum and the nonrefoulement obligation is respected in Morocco and ensuring that all returned persons are treated humanely. This assessment should form an integral part of any decision to enter into an EU readmission agreement with Morocco.

- The European Parliament should scrutinize carefully the content and implementation of any planned EU-Morocco readmission agreement in light of the human rights abuses documented in this report.

- EU member states and the EU should combine financial and programmatic support to Morocco for legitimate border enforcement and migration management with capacity building for relevant sections of Morocco’s government to better protect refugees and asylum seekers and to promote respect for the human rights of all migrants.

- The European Commission should pressure the Spanish Government to implement the 2010-2014 European Union Action Plan on Unaccompanied Minors.

To the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants

- Request an invitation to visit Morocco and the Spanish enclaves of Melilla and Ceuta to examine the treatment of migrants and asylum seekers, including at borders.

To the UN High Commissioner for Refugees

- Establish a more regular and effective presence in northeastern Morocco in the areas at and between the Algerian border and the Spanish enclave of Melilla to ensure that asylum seekers have access to UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

- Offer technical assistance to the Moroccan Government where possible to ensure the protection of unaccompanied child migrants.

Methodology

This report is based on research in Morocco and Spain from late November 2012 to mid-December 2012. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 66 migrants in the cities of Nador and Oujda in Morocco and 4 migrants in the Spanish enclave of Melilla. Two of the migrants in Melilla were Moroccan unaccompanied migrant children and one migrant was from Bangladesh. They were not included in the total of 67 migrants from sub-Saharan Africa referenced throughout the report.

Out of the 67 sub-Saharan migrants interviewed in Morocco and Spain, 37, including 4 women, had been expelled by Moroccan authorities at the border with Algeria and had returned to Morocco. Thirteen, including 5 children, had been expelled from Melilla.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 10 unaccompanied children, the youngest of whom was 12 years old. The oldest person interviewed was 52 years old. Two migrants were identified as having physical disabilities. Human Rights Watch interviewed 25 migrants who identified themselves as coming from Cameroon, 14 from Ghana, 7 from Nigeria, 7 from Guinea, 5 from Mali, 4 from the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2 each from Côte d’Ivoire and Morocco, and 1 each from Bangladesh, Benin, Senegal and Burkina Faso. Human Rights Watch interviewed 21 women and 49 men.

The names of all migrants and asylum seekers interviewed for this report have been changed in the interest of their security.

All interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview and that their interviews might be used publicly. No incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed. All interviews were conducted individually or, when conditions allowed no alternative, in a small group. Most interviews were conducted in private locations. The interviews were conducted in French, Arabic, or English.

Local activists and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that regularly work in the sites we visited helped Human Rights Watch to identify interviewees. We asked the governor of Melilla and the facility director for permission to visit Los Centros de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes (CETI – Centers for the Temporary Stay of Immigrants) in Melilla, but received no response to our request.

Human Rights Watch interviewed, either in person or by telephone, officials of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the Delegation of the European Union in Morocco, and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Rabat, Morocco. We also interviewed staff members of NGOs in Morocco and Spain, including Médecins Sans Frontières Spain (MSF-Spain), the Groupe antiraciste d’accompagnement et de défense des étrangers et migrants (Gadem), the Organisation Marocaine des droits de l’homme (Moroccan Organization for Human Rights, OMDH, Rabat and Oujda sections), the Association marocaine des droits humains (the Moroccan Association for Human Rights, AMDH, Rabat and Oujda sections, l'association Rif des droits de l'Homme (the Rif Association for Human Rights), and the Association Beni Znassen pour la Culture, le Développement et la Solidarité (Beni Znassen Association for Culture, Development and Solidarity, ABCDS). Human Rights Watch interviewed representatives of Morocco’s Interministerial Delegation of Human Rights and the Conseil national des droits de l’Homme (National Human Rights Council, CNDH).

Terminology

When describing law enforcement officials in Morocco, migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch did not distinguish clearly among Moroccan military, police, and gendarmes, but their roles are indeed distinct. Police officers operate in urban areas, while gendarmes operate in rural ones.

The Auxiliary Force is a paramilitary force that, among other responsibilities, is tasked with assisting other security forces when necessary and guarding Morocco’s borders in the north of the country. In this report, when migrants encounter security forces at the border with Algeria or Spain, they are usually encountering agents of the Auxiliary Forces. Often, when migrants encounter Moroccan security and law enforcement officials in urban areas or in informal migrant camps outside cities, they are describing police and gendarmes. Interviews with migrants indicate that Moroccan Auxiliary Forces provided additional support to the police and gendarmes when conducting raids on makeshift migrant camps outside of Nador and Oujda. According to migrant accounts, these three forces coordinate their efforts at various stages.

Both Auxiliary Forces and gendarmes usually take migrants to police stations in the larger city centers (Nador and Oujda) before expelling them. When migrants are expelled at the border with Algeria, they are usually handed over by the police or gendarmes to the Auxiliary Forces near the border.

Although international law defines “migrant workers,” it does not define “migrants.” In this report, “migrant” is a broad term to describe third-country nationals in Morocco. We use the term inclusively rather than exclusively; the use of the term “migrant” does not exclude the possibility that a person may be an asylum seeker or refugee.

An “asylum seeker” is a person who is trying to be recognized as a refugee or to establish a claim for protection on other grounds. Where we are confident that a person is seeking protection, whether in Morocco or Europe, we refer to that person as an asylum seeker. A “refugee,” as defined in the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, is a person with a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” who is outside his country of nationality and is unable or unwilling, because of that fear, to return. The 1969 Organization of African Unity Refugee Convention further defines refugees as persons who are compelled to flee “events seriously disturbing public order.” Recognition of refugee status by a government or UNHCR is declaratory, which means that people are, in fact, refugees before they have been officially recognized as such.

In line with article 1 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the term “child” refers to a person under 18. [1] This report discusses children traveling with their families as well as unaccompanied children. When referring both to children traveling with their families and to unaccompanied children, the report uses the term “migrant children.” This term includes children seeking asylum or those granted UNHCR refugee certificates. The definition of “unaccompanied migrant child” comes from the term “unaccompanied child” used by the Committee on the Rights of the Child. According to the committee’s General Comment No. 6, “‘Unaccompanied children’ are children, as defined in article 1 of the Convention, who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.” [2]

I. Background

I am fearful of the police. I can’t rent a home, I can’t work. I have to beg. We stay in the bush, people living like animals.... [3]

–Omar S., 26, Nigeria

Most migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Morocco come from western and central African countries, which they have left because of poverty, family and social problems, political upheaval, civil strife, and, in some cases, fear of persecution. Interviews Human Rights Watch conducted indicate that there are two main land routes of migration into Morocco: one follows the West African coast via Mauritania; the other one, more heavily used in recent years, is inland through Niger and Algeria with an entry point to Morocco near the Algerian town of Maghnia. [4] Smuggling networks appear to play an important role in organizing transit through Niger and Algeria into Morocco. Most migrants who enter Morocco through Maghnia head toward Oujda, the closest city on the Moroccan side, [5] before heading to the areas surrounding Nador, if their aim is to attempt to enter the Spanish enclave of Melilla or to attempt a journey across the Mediterranean by boat.

In and around Oujda, migrants live in several sites, including the “Fac” site on the university campus in the city,[6] and, outside the city, the “Café Gala” area, the “Moussakine” forest, and the Sidi Maafa forest. Interviews with migrants and with local NGOs indicated that most migrants who enter Morocco from Algeria go to the Oujda Fac site to join other migrants and find smugglers who can help them on the next step of their journey.[7] Some settle in more secluded sites, such as in the forested hills and mountains outside of Oujda. While waiting to make the passage to Melilla, migrants stay in several sites around Nador: Mount Gourougou, the mountain on the Moroccan side of the border with Melilla; forest areas near Selouane, a neighboring town; and forest areas near the Marjane supermarket outside of Nador.

In all of these sites that Human Rights Watch visited, migrants live in tents improvised from sticks, branches, and plastic tarps. The makeshift shelters are often cramped, housing several families or large groups of unrelated individuals.

An unofficial migrant camp outside of the town of Nador. © 2012 Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch interviews depicted conditions where migrants subsist without running water or electricity, or do not have sufficient protection from cold, rain, and wind. Far from city centers and lacking transportation, the migrants have little access to medical services when necessary, and they shy away from schools for fear of being noticed and apprehended by the police.

Migrants have limited options for earning money in Morocco. Many are undocumented, thus unable to work legally. While some find work in larger cities, there are fewer opportunities in rural areas. Most migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch survive on the begging that some of them carry out. Because law enforcement officials are more likely to arrest male sub-Saharan migrants than females, according to those we interviewed, women more often go to the medina (the old city)—with children in tow—to beg for money and food, usually near mosques after Friday prayers.

II. Police Abuse of Migrants in Informal Settlements

It’s a very terrible life in the forest. I used to sleep but now I wake up at 3 a.m. to go to the school [to hide] because [the police] come and arrest us every day. They run after [us]. They burned our house. We had run away and when we came back, all the houses, the food, were burned down. There were many police that day. – Anthony F., 17, Ghana

Police conduct frequent raids on the makeshift migrant camps in the areas surrounding Nador and Oujda to apprehend undocumented migrants, including unaccompanied children, and subsequently expel them at the Algerian border. According to interviews with migrants, the frequency of the raids varies from daily to weekly. Migrants, anxious that the police will raid their camps, sleep very little from 4 a.m. to 6 a.m., when the police usually carry out their raids. “We don’t sleep,” said Luc F., a 27-year-old from Cameroon. “The police can come at any time. I run barefoot on the hill, we’re tracked like monkeys. They come at 5:45 [a.m.], screaming. They try to rob, take everything.” [8]

Of the 67 migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed in sites around Nador and Oujda, 42 migrants described frequent raids. Interviews with migrants at these various sites indicated a pattern of abuse by law enforcement officials during their raids: robbing migrants’ money and objects of value, such as phones; burning their personal property and makeshift shelters; and using excessive force against migrants when apprehending them. In some cases, officials destroyed or confiscated passports and other documents without returning them.

Pierre C. is a 28-year-old migrant from Ghana who said he had arrived alone in Morocco eight months before being interviewed by Human Rights Watch in December 2012. At that time, he was staying in the Moussakine forest outside of Oujda with other Ghanaian men. He described living in constant fear of being arrested and forced to return to the Algerian border:

There is no rest here. Every morning, the gendarmes come. Yesterday [December 2, 2012], I was trying to prepare food and they came. I asked them if they could wait until I ate a bit, knowing that I wouldn’t have food, only a long walk after deportation [from the border back to Oujda], but they refused. It was 6:30 a.m. and I walked with them and obeyed because if you refuse, they will beat you up.[9]

After Pierre was arrested, the gendarmes took him to the Oujda police station, where he was fingerprinted and held in a cell with other migrants until 8 p.m. He said they were then taken by bus to another police post near the border with Algeria and handed over to Auxiliary Forces who walked him and other migrants close to the border and forced them to leave Morocco. After he walked away from the Moroccan authorities, he waited until he was out of their sight and started the six-hour walk back to his campsite. [10]

Mahdi S., who lives in the Sidi Maafa forest just on the outskirts of Oujda, described a similar situation: “There is no work; it’s very hard to eat. I beg for money outside the mosque. The police come every day so I sleep for a few hours then go back. They burn our tents – like they are going to war.”[11]

In Nador, the situation mirrors the one in Oujda. Antonin S. told Human Rights Watch about the daily morning raids he had encountered: “I have been in Nador since August 2012. I am choking with fear. My head is tormented because of the police. They don’t give us peace. They don’t pay attention to our legal status [in Morocco]. They don’t respect women or children. We are not animals, even if we live here [in the forest].”[12]

In every one of the 42 accounts of Moroccan security raids, migrants described law enforcement officials arresting male migrants without conducting any type of identification or assessments of migrants’ status in Morocco prior to arresting them, and, in the case of unaccompanied children, without conducting any form of age determination. They said that police officers routinely arrest male migrants indiscriminately, even if they have a visa or other documentation showing they have permission to stay. Also arrested are migrants from countries for which Morocco does not require entry visas—including Senegal, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire—whose nationals are allowed to stay for up to 90 days without a visa. [13] In contrast to migrants who told Human Rights Watch that police officers arrested them in Morocco’s larger cities after stopping them in the street and asking to see their passport or visa, migrants who were arrested in raids or witnessed such arrests in the northeastern border region did not receive identity checks.

Robbery

The majority of migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed in Nador and Oujda reported that officers from the police, auxiliary force, and gendarmes often robbed them during raids of the informal camps and when transporting the men captured at the camps to the Algerian border.

Ismael M., who lives in one of the forests outside of Oujda, told Human Rights Watch how the gendarmes had been coming frequently since December 2011. Robbery is a routine part of the daily raids, he said: “The gendarmes look for men, they enter the tents and take phones. We migrants lose our phones every day.” [14]

Ismael’s experience is only one example of police theft of the valuables of migrants. Throughout the report, in chapters dealing with other forms of abuses, migrant interviews make reference to similar thefts by security forces, of which they claim they were victims.

Destruction of Shelters, Property, and Documents

In every migrant site that Human Rights Watch visited, in both Nador and Oujda, migrants said that Moroccan security forces summarily burned or destroyed their makeshift shelters and personal property without following any due process procedures for conducting evictions. Migrants told Human Rights Watch that in the months prior to the interviews, these raids occurred frequently, most often weekly, and sometimes several times a week. Human Rights Watch observed the remains of several makeshift shelters and piles of belongings that had been destroyed by fire. Migrants told Human Rights Watch that the police had burned the shelters and belongings.

Two tents destroyed by Moroccan security forces at an unofficial migrant camp outside of Selouane, near Nador. © 2012 Human Rights Watch

Local organizations have previously reported on this type of destruction. In September 2012, the Council of sub-Saharan migrants in Morocco (CMSM - Conseil des migrants subsahariens au Maroc) and a group that fights for migrant rights and against racism, the Gadem, reported that police burned down an abandoned house where migrants had been squatting just outside of Nador. [15]

Human Rights Watch conducted several interviews of migrants who had been living in the abandoned house that the authorities burned down. Antoine K. from Benin had been living there during the summer of 2012. He told Human Rights Watch how police, gendarmes, and Auxiliary Forces raided the house on a regular basis over the summer, sometimes daily, until the migrants who were living there moved deeper into the forest because they felt unable to remain in the house due to the raids. He said in August 2012:

The police started coming again every day. Some [migrants] would go up to sleep in the forest. One week later they came and expelled us. The police said they were going to burn the house down …. On August 27 [2012] they tried to expel us from the white house. We left. We were staying outside for a week to ten days. We kept getting pushed back further and further, first to the olive groves, and then to here in the forest. On October 6, 2012, the police showed us [where to go], they told us to go into the forest. We thought we would not have any more problems but after one week, they started coming again. They kept coming until they burned everything.[16]

While many migrants enter Morocco without the necessary documentation and visas, others do carry passports showing that they are lawfully present in Morocco, particularly those from other West African countries who do not need visas to enter Morocco. When the authorities burn or otherwise destroy their documents, however, they lose the proof that they are in the country legally. Antoine K. said that this happened when the authorities burned down the abandoned house outside Nador. “There were no negotiations; they burned our bags in the fire after searching them. They burned many passports.” [17]

In another site, outside of the town of Selouane, Human Rights Watch interviewed 11 women who described a raid in November 2012 during which Moroccan law enforcement officials destroyed their tent, leaving them without shelter. Four of these women were pregnant when the shelter was destroyed. In reference to this raid, Sofia K., a woman from Cameroon, four months pregnant, explained: “I have been in Selouane four months. We don’t live well here. The police shake us up. I was traumatized when one day, a month ago, the police came in the morning and destroyed my tent.”[18]

Another pregnant woman, Elizabeth S., also from Cameroon, lives in the same site. She described a similar situation, “The police come nearly every Sunday or Monday and the men run away. Women don’t run away. They shove us around. Once they almost took me away but [then] took the others [to be expelled]. They burned all our tents. I stay here, I can’t walk [she is eight months pregnant].”[19] The inhabitants of the camp were effectively rendered homeless.

Interviews conducted with the 42 migrants who experienced or witnessed a police raid of their campsite strongly suggest that Moroccan officials follow no formal procedure before dismantling unofficial migrant camps. One exception was a migrant who indicated that the police presented him with an eviction notice before removing him from a house where he were squatting in one of the Nador sites that Human Rights Watch visited. [20] Every other migrant interviewed by Human Rights Watch described raids that lacked any of the procedural steps required by international law, such as written notification and the right to appeal a decision.

By destroying the makeshift tents of migrants during raids, Moroccan enforcement officials may be rendering migrants homeless. Destruction without due process of shelters may constitute forced evictions, and may therefore constitute a violation of the right to housing, which is guaranteed by international human rights treaties to which Morocco is a party.

Violence during Raids

Of the 42 migrants who described to Human Rights Watch daily to weekly police raids, 12 said that Moroccan authorities used violence against them during raids; seven other migrants said they witnessed such violence.

One migrant with a physical disability who used crutches, Hassan N., described the excessive force he said police used during a raid outside Nador in the summer of 2012:

My second refoulement was on June 20, 2012. We had changed our sleeping grounds and the police came with sticks. I was hit with sticks and asked why we were here. I was handcuffed and then they grabbed me and hit me 10 or 12 times on my back with a stick. I was bleeding.[21]

A female migrant, who said she was five months pregnant, told Human Rights Watch about similar violence she experienced during an early morning raid in one of the sites in early December 2012:

The police came here last Tuesday at 5 or 6 in the morning. It was the gendarmerie and police together…. They came when we were sleeping and abused us. They asked me, “where is your husband” and they beat me. They kicked me in the stomach even though I told them I was pregnant. They said we are not welcome here. I yelled and eventually they left. They arrested 8 or 9 of the men.[22]

III. Collective Expulsions from Morocco to Algeria

Human Rights Watch interviewed 67 sub-Saharan migrants in the Oriental region of Morocco, 37 of whom had been expelled at the border with Algeria at least once. All 37 nonetheless returned to the informal settlements in Morocco. In nearly all the 37 cases, the migrants said that Oujda police transferred them east of Oujda to the Moroccan Auxiliary Forces stationed at the border with Algeria. [23]

Morocco does not have dedicated reception centers for migrants or unaccompanied migrant children comparable to the CETI ( Los Centros de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes – Centers for the Temporary Stay of Immigrants) in the Spanish territories of Melilla and Ceuta or the Purisima centers in Melilla. Instead, the Moroccan authorities use cells in police stations to hold undocumented migrants. [24]

Some interviewees were apprehended during or after their attempt to enter one of the Spanish enclaves: 11 were summarily removed by Spanish authorities in Melilla and handed over to Moroccan authorities. Most were then taken to a police station; some were taken directly to the Morocco-Algeria border.

The Auxiliary Forces posted along the Algerian border east of Oujda escorted the arrested migrants toward Algeria and instructed them to walk straight ahead (nishan in Moroccan Arabic). One-third of the expelled migrants we interviewed described being forced to cross the border or threatened with violence if they did not leave Morocco.

Sometimes migrants were directly taken to the border late at night. The timing of these expulsions, usually carried out between 9 p.m. and 2 a.m., and the fact that the migrants were not handed over directly to Algerian authorities, suggest that expulsions take place unofficially.

None of the 37 migrants who had been expelled were provided access to a lawyer or an interpreter, they told Human Rights Watch. Generally, the police did not provide them with a statement or document charging them with any violation, or bring them before a judge, or provide any opportunity to challenge their impending expulsion. When the police did provide a statement to them, the migrants told Human Rights Watch that the police pressured them to sign it even though it was in Arabic, which they did not understand.

Gadem, a Moroccan anti-racist organization that works with migrants, evaluated the removal and expulsions of migrants from Moroccan territory between 2004 and 2008. Its report, “The Human Rights of Sub-Saharan Migrants in Morocco,” found fundamental gaps in the protection of vulnerable groups from expulsions and violations of due process during the removals.[25] Human Rights Watch’s research shows that these gaps remain.

This chapter examines how Moroccan authorities continue to expel migrants from Morocco at the Algerian border without following due process. Migrants’ rights are violated at various stages, from the time they are arrested to their expulsion at the Algerian border.

Moroccan Police and Auxiliary Forces Use and Threaten Violence

Six of the 37 migrants who were expelled from Morocco at the Algerian border told Human Rights Watch that Moroccan Auxiliary Forces directly subjected them to violence; two migrants said they witnessed such violence, which included seeing Auxiliary Forces hitting other migrants with wooden sticks approximately 100 centimeters long.

One unaccompanied 14-year-old migrant boy from Burkina Faso who was arrested in Nador after attempting to enter Spain said:

I was arrested once in Selouane. I went to the shop and someone in civilian clothing arrested me, handcuffed me, and took me to the commissariat of Nador. I was fed there. There were many people there. I told them [the officials] I was 14…. At 8 p.m., a bus took me to Oujda, straight to the border…. In Oujda, they had dogs, they shoot [their guns] at night. We got off the bus and we were told to go. We left so that they wouldn’t hurt us. [26]

Amin K. said he did not get a lawyer and was held in a cell with unrelated adults.

Another migrant, Nicolas E., 39, from Cameroon, said, “The Moroccan military pushed us toward Algeria yelling “Yallah! [Let’s go!].” They treated me really badly, they kicked me so much that I am peeing blood as a result.” [27]

Lack of Due Process for Adult and Child Migrants

I was never offered a lawyer. […] They only asked if I have a passport. [28] –Nicolas E., 37, Cameroon

I was arrested at the bus station, handcuffed, and taken to the gendarmerie. Then they took me to the central police station in Oujda and put me in a cell. [The police] asked my age and I told them I was 17… I was then put in a cell with 52 … men …. I did not have a lawyer and I was not told that I was going to be expelled….

We were all taken by bus, including an Algerian woman and her [five-year-old] child. We were taken to a small house [at the border], where there were gendarmes. They asked for our [finger]prints and to line up.… We were asked to stand up [to leave Morocco and walk into Algeria]. They used some force on those who didn’t want to go. They got slapped and punched. And we went towards the forest [where the border is]. [29] –Frank D., 17, Cameroon

None of the migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had been expelled from Morocco described receiving any information about their rights, nor did the authorities give them the opportunity to contact consular representatives of their country of origin. None of the unaccompanied migrant children we interviewed were treated as children, even when they declared their age, for example, by being given guardianship and legal assistance. As one migrant told Human Rights Watch, “The police told us, you have no rights here.” [30]

Before expelling or “returning” migrants to the border, police sometimes issue them a procès verbal, a police report pertaining to their arrest. Only 5 of the 37 expelled migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed reported having received such a statement, and 2 of these 5 said they could not understand or did not get the opportunity to read the statement, but they were coerced to sign. One migrant, Eric P., described his arrest in Selouane, near Nador, and his subsequent expulsion:

The police took us in vans to the Nador police station, where many others were put in cells.… The police asked us our names, nationalities. They got us to sign a statement (procès verbal) with finger prints. We hadn’t read it…. The same day, around 6 p.m., the police took us to Oujda in a bus…. They drove us to the border…. They handed us over to the border guards who showed us the Algerian border and pushed us to cross.[31]

Anthony F., an unaccompanied 17-year-old child migrant from Ghana, made no mention of having received a procès verbal on the two occasions when he was expelled:

I was arrested twice in 2012, in January and March [when he was 16 years old]. The first time I was taken to the police station, my prints were taken…. The police did not ask anything. I was not taken to a cell; [they took us] straight to the … border. I ran back because the Algerian police were there, holding guns and telling us to go back. The second time, I was begging on a Friday and the police took me to the police station. They took my prints and then took me to the [border].[32]

Another migrant, Olivier S., a 28-year-old Cameroonian, described to Human Rights Watch how Moroccan police coerced him and other migrants to sign documents they did not understand:

[The police] took us to the Nador Commissariat…. They took our [finger]prints and photos. I didn’t see a lawyer. We were in the courtyard, with no toilets. The clandestine [migrant] has nothing to say. All the documents were written in Arabic and we were told to sign. If we don’t sign, we get hit.[33]

The Euromed Human Rights Network (EMHRN) has noted that, “The lack of information foreigners have about the appeals procedures makes it very difficult, indeed impossible, for them to exercise their rights. Moreover, they are not made aware of their rights.” [34] Indeed, Morocco’s Law 02-03 does not require the authorities to inform migrants or foreigners of their rights, except in cases when they are detained following a judicial decision of expulsion or a return to the border. [35]

Collective Expulsions

[In July 2012], I was taken to the Nador Gendarmerie [police station]. They didn’t take my prints or my photo. It was a big refoulement, about 45 people. I was put in a refoulement cell after I was grabbed at night. And the next day, around 4 p.m., we were taken by bus [to the Algerian border]. [36] – Bouba L., 35, Mali

Of the 37 migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed who were expelled at the border with Algeria, nearly all had been apprehended as part of a group, taken to the police station in a group, and brought to the Algerian border and expelled as a group. Collective expulsions documented by Human Rights Watch ranged from groups of 3 migrants to groups as large as 52 migrants. In no case did the Moroccan authorities notify any of the individuals of a judicial decision to expel or return them to the border.

Article 22 of the Migrant Workers Convention, to which Morocco is a state party, prohibits the collective expulsion of migrant workers: “Migrant workers and members of their families shall not be subject to measures of collective expulsion. Each case of expulsion shall be examined and decided individually.” [37] Article 22 applies to all migrant workers and their families, irrespective of their status.

Choice of Destination Country

The decision to remove a migrant is distinct from the choice of country to which that migrant should be returned. As per article 30 of Law 02-03, “The decision establishing the country of return is separate from the decision of expulsion itself.” [38] However, none of the 37 migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed who were expelled at the Algerian border were given the opportunity to choose or to discuss the country of their return. Gadem, an NGO that provides support to migrants in Morocco, observed that Morocco neither formally decides on the proper return country nor seeks or obtains Algeria’s agreement to receive deportees prior to their expulsion:

Apart from the fact that the administration has not seemed to have made any decision determining the return countries, it seems very hazardous to consider Algeria as a place where migrants who have been returned in such a manner would be “legally admissible,” considering that said country has apparently not agreed to receive returned individuals.[39]

In fact, not one of the migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed said that the Moroccan authorities had officially handed them over to Algerian authorities when expelling them at the Morocco-Algeria border. On the contrary, after Moroccan officials forced them to cross into Algeria, they said that Algerian border control agents mistreated them. Every single migrant interviewed by Human Rights Watch whom the Moroccan authorities arrested and subsequently expelled at the Algerian border said that Algerian law enforcement officials they encountered forced them back to Morocco.

Moroccan authorities arrested Eric P., a migrant from Ghana, during a raid in Nador a few days before Human Rights Watch interviewed him. He described what happened after Moroccan authorities forced him and other migrants across the Algerian border outside of Oujda:

On the other side, when we crossed, the Algerian border guards arrested us, searched us and took the money and phones they found on some of us. Those who had money were released, while those who didn’t have money were beaten. I didn’t have money so they took my jacket and beat me. We ran away and got back to Morocco the same day. We walked for five hours to reach Oujda by 6:00 a.m. the next day.[40]

Another migrant described what happened after Moroccan authorities arrested him and other migrants near Melilla and then expelled them at the Algerian border:

When we crossed the Algerian border, the [Algerian] guards arrested us, searched us. They found some money and a cell phone on me. They gave them back to me and they pushed us back to the Moroccan border. We crossed and came back to Oujda.[41]

Vulnerable Categories

Moroccan national immigration law prohibits the expulsion of pregnant women, children, refugees, and asylum seekers. The latter three have specific protection under international law as well. According to article 29 of Law 02-03, “No pregnant foreign woman and no foreign minor can be removed. Similarly, no foreigner may be removed to a destination country if he establishes that his life or freedom are threatened or if he will be exposed to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.”[42] However, Human Rights Watch found that Morocco sometimes expels pregnant women, children, asylum seekers, and migrants with a potentially strong claim for asylum.

Pregnant Women

Most migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed indicated that Moroccan authorities generally do not arrest and deport or expel women, particularly not when they are pregnant. [43] However, Human Rights Watch found that there were nonetheless cases when Moroccan security forces arrested and expelled pregnant women in contravention of provisions in the national law on immigration. One woman told Human Rights Watch that security forces expelled her from Morocco after arresting her and her sister in Fez, on December 2, 2012 when she was three to four months pregnant.

In Oujda, Human Rights Watch interviewed the two sisters shortly after they found their way back to the ‘Fac’ campsite on the university campus of Oujda after walking back from the Algerian border the previous night. The sisters, ages 27 and 18 from Cameroon, had been living in the city of Fez until then; one said she was three to four monthspregnant while the other had an infant child. When they went to get milk for the baby, the police arrested them. Despite their telling the police that the six-month-old baby was still at home, the police took the two women to the police station and held them there for four to five hours before putting them on a bus to Oujda. The police took them to another police station in Oujda, where the younger sister told the police she was pregnant. Nevertheless, the police expelled the two sisters in the middle of the night, at the Algerian border with a group of 30 other migrants. Human Rights Watch later heard that both women managed to return to Fez. The baby remained in Fez, where other migrants cared for him during his mother’s expulsion.[44]

Children

Moroccan law enforcement officials expelled eight of the nine sub-Saharan unaccompanied migrant children Human Rights Watch interviewed in Nador and Oujda. These children ranged between 12 and 17 years old at the time of their expulsion, according to what they told Human Rights Watch. The one who was not expelled was a 14-year-old girl, who said that the gendarmes were only arresting men during raids of the informal camp where she lived.

In none of these cases did the Moroccan authorities provide appropriate care or conduct age determinations after the children informed them that they were younger than 18 years of age. On the contrary, these children described being treated like everyone else from the time of apprehension to their expulsion.

A 12-year-old unaccompanied migrant boy from Cameroon, Jean-Luc, described the chain of events after his arrest in Nador in November 2012: “I spent one week in a cell with no food, with five, six other people, including adult men. There was no interview.… I never saw a lawyer. I was put on a bus and taken to the border behind the Gala café. We were given to the military in a small house [at the border] and the police threw us across the border. They did not hit us. They stole phones, six phones, and shoes.” [45]

In February 2013, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child urged states to “expeditiously and completely cease the detention of children on the basis of their immigration status,” arguing that such detention is never in the child’s best interest.[46] In 2006, the Committee stated that “unaccompanied or separated children should not, as a general rule, be detained,” and “detention cannot be justified solely on… their migratory or residence status, or lack thereof.” [47] The Convention on the Rights of the Child and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights require states parties to separate adults from unrelated children in detention, in the exceptional circumstances where children are detained,[48] and the Committee reiterates the importance of this in the case of unaccompanied migrant children.[49]

Morocco does not provide unaccompanied migrant children in its territory with guardianship, despite its obligations under international law. The rapidity of the process, the lack of a translator and of legal representation prevents migrant children from having the opportunity to establish their age. In the expulsion of children from Morocco, Human Rights Watch found that no age determination procedure was conducted and that their status as children was ignored, even when they volunteered their age. In the cases Human Rights Watch examined, Morocco did not appear to consider the child’s best interest when determining immigration cases, contrary to what the Committee on the Rights of the Child has prescribed:

A determination of what is in the best interests of the child requires a clear and comprehensive assessment of the child’s identity, including her or his nationality, upbringing, ethnic, cultural and linguistic background, particular vulnerabilities and protection needs.[50]

Expulsions or “Returns to the Border”?

In 2011, the UN Committee Against Torture said that Morocco should investigate allegations that migrants had been subjected to “ill-treatment or excessive use of force” during expulsions and that Morocco “ should take steps to ensure that the legal safeguards governing the practice of escorting undocumented migrants to the border and the expulsion of foreign nationals are effectively enforced…in accordance with Moroccan law.” [51]

In response, the Moroccan authorities emphasized the distinction in its national law between expulsion and “returns to the border.” [52] Moroccan authorities claimed that “the law […] makes a distinction between a return to the border and expulsion. A return to the border is a legal act, accompanied by all the legal and procedural guarantees provided against any person who enters or exits Moroccan territory by exits or places other than border posts, or who remained on Moroccan territory beyond the authorized length of their visa.” [53]

Similarly, in a letter to Human Rights Watch, the Moroccan authorities said that returns to the border were lawful:

In accordance with the well-established rule of international law, returns to the border, taking due account of the need to respect the dignity and rights of migrants, as well as the rights of defense, including the exhaustion of appeals against the decision of removal, are carried out by transporting the migrant, subject to a legal measure of return to the border, to the last point of infiltration onto national territory. In this respect, one must remember that Morocco's land borders with Algeria, 1,601 Km long, are the infiltration point of virtually all foreigners entering the country illegally. [54]

The Moroccan authorities also deny expelling migrants or forcing them to leave Moroccan territory: “Within the framework of the management of migration, the Moroccan authorities, acting in strict legality, never forced migrants to leave the country and enter Algeria.”[55] In this letter, the Moroccan authorities assert that they do not conduct any expulsions and also that any returns to the border are legal when they have followed the procedural requirements ensuring migrants’ rights to due process, including their right to contest the decision of return. The Moroccan government previously emphasized this distinction and the legality of returns to the border in its initial report to the Committee on the Rights of Migrants, as well as in its response to this Committee’s follow-up questions.[56] This distinction between expulsions and “returns to the border” does exist in Law 02-03 regulating immigration: articles 21-24 deal with “returns to the border,” articles 25-27 with expulsions, and articles 28-33 with both, all of which outline procedural responsibilities on the part of Moroccan authorities for conducting either expulsions or “returns to the border.”

However, in practice, the distinction between expulsions and “returns to the border” is far from clear. Migrants said they are either coerced to leave the Moroccan territory with the threat of violence, or pushed toward the Algerian border by Moroccan security forces. This treatment effectively expels migrants from Morocco, as opposed to “legal” “returns to the border” from which migrants allegedly entered the country. Contrary to the Moroccan government’s claims, all the cases Human Rights Watch documented of forced removals of migrants from Morocco to the Algerian border were, in practice, expulsions.

As shown throughout this chapter, victim and witness evidence consistently show that law enforcement authorities who arrest migrants in the northeast region of Morocco transfer migrants to the Oujda police station with no opportunity to appear before a judge. The Oujda police then subject them to summary expulsion from Moroccan territory, often accompanied by violence, theft, and other abuses. The Moroccan authorities routinely violate migrants’ rights to due process in this encounter.

Mistreatment at the Moroccan-Algerian Border

Violence and Theft Carried Out by Algerian Border Police

Of the 37 migrants who told Human Rights Watch that they were expelled from Morocco, 17 migrants, including 5 children, said that they had witnessed or were themselves the victims of violent interactions with Algerian border patrols after they crossed the border. Three additional migrants claimed to have witnessed such violence. These 17 migrants told Human Rights Watch that Algerian border patrols hit them with wooden batons and, in many cases, stole any valuables they found on them. Algerian forces then turned the migrants back toward Morocco, where they then walked 20 or more kilometers to reach Oujda.

Olivier S., from Cameroon, recalled what happened to him after he was expelled from Morocco at the Algerian border in January 2012:

We tried to cross into Algeria but the Algerian military were waiting for us. The Algerians told us to lie down or they would shoot. They took our phones, took all our money, and opened the seams of our pants. They said that if we cooperate, they would not hurt us and then they showed us the way to get back to Morocco.[57]

Another migrant, Anthony F., 17, from Ghana, described his second expulsion from Morocco, in March 2012:

The second time [I was expelled], I was begging on a Friday and I was taken to the police station. They took my [finger]prints and then took me to [the border]. I got away but the Algerian military took my money. There were three Algerians; they hit me. [58]

IV. Excessive Force against Migrants at the Moroccan Border with Melilla, Spain

I took the train to Nador, three days before the attempt to go into Melilla. I ran with 85 others. I got hurt on the first fence, on the barbed wire, and fell back into the Moroccan side. One Alit [a member of the Moroccan Auxiliary Forces][59] stopped me and tried to take out the barbed wire that was attached to me. Others hit me with a baseball-bat-like [stick] on my knee and shins, [saying] “So you won’t be able to walk,” and also the elbows. [My bones] were badly fractured; I was hit for six minutes by more than ten men. [60]

– Frank D., 17, Cameroon.

In the morning I attempted to get into Melilla. Some got in. I climbed the fence and the [Moroccan] military threw rocks at my head. I lost my grip and fell. They hit me, there were eight people, hitting with a baseball bat.… I couldn’t see because of the blood: my head was cut. They hit me lots.[61] – Jean-Luc M., 12, Cameroon

Human Rights Watch’s research found that Moroccan authorities beat children and adults when they attempted to cross into the Spanish enclave of Melilla. These enclaves, located in the northeast region of Morocco, bring Europe’s external borders to the southern side of the Mediterranean Sea. Both Moroccan nationals and third country nationals try to enter the Spanish enclaves by scaling the fences that protect the land borders. They also attempt to reach these enclaves or cross to the Spanish mainland on inflatable motorized boats. Melilla’s borders are protected by three rows of razor-wire fences reaching six meters tall. The fences are monitored with the use of infrared cameras, and motion and noise detectors. [62] The surrounding terrain is rocky, hilly, and forested, with Mount Gourougou rising on the Moroccan side of the fence. The second enclave, Ceuta, has two fences and a similar infrastructure.

A migrant from Chad at El Hassani hospital in Nador who told Human Rights Watch that Moroccan security forces broke his leg by hitting him with a rod. © 2012 Human Rights Watch

Even though Melilla and Ceuta are part of the Schengen Area, any further travel to mainland Spain and Europe by air or sea is subject to additional border identity checks.[63] In spite of this, many migrants believe that if they manage to enter one of the enclaves and gain access to one of the migrant detention centers, they might be transferred to mainland Spain due to capacity concerns in the existing centers.

Most migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that Moroccan Auxiliary Forces who encountered them as they tried to cross into Melilla used excessive force, not only to prevent them from crossing, but also, seemingly, to punish them. In addition to reporting that members of the Moroccan Auxiliary Forces beat them when they were caught trying to scale the fence into Melilla, many migrants, including children, also said that Moroccan security officials beat them after the Spanish Guardia Civil returned them from Melilla. Some said Moroccan border security officials beat them as soon as the Guardia Civil transferred them into their custody. Even if the use of force is sometimes necessary “if other means remain ineffective or without any promise of achieving the intended result,” [64] migrant accounts and other NGO reports indicate that Moroccan authorities use violent measures that go beyond necessary force to prevent migrants from entering Melilla or for apprehending migrants being returned.

In March 2013, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) released a report condemning the “institutional violence” faced by sub-Saharan migrants in Morocco at the hands of Moroccan and Spanish authorities, particularly at the borders with Spain and Algeria. [65] That same month, to protest police abuse of sub-Saharan migrants, MSF announced that it would pull out of Morocco "to demand that those responsible and capable of solving this problem take responsibility for it." [66]

Olivier S., another migrant from Cameroon, told Human Rights Watch that after he and a group of migrants reached Melilla on a motorized inflatable boat in April 2012, the Guardia Civil handed them back to Moroccan gendarmes who beat the men, even though they had full custody over them:

Sixteen of us were given to 12 Moroccan gendarmes. As soon as they got us, they took us to the forest one hour away. We were told to lay on the ground on our stomachs with our hands above our hands, in a row. They started to hit us. Many of them were young, proud to hit us. Not all of them were in uniform. They kicked us with their boots, slapped us, hit us with sticks, baseball bat-like sticks.[67]

Two other migrants, Bouba L. and Pierrot D., described similar violence on the Moroccan side of the border:

They strike you with wood…. They beat you up routinely. I was told to lie on my stomach so they hit me on my back and butt. They searched me, but since I didn’t have much they left me. They kept my clothes and sent me to Oujda.[68]

The Moroccan military [Auxiliary Forces] took me [aside]. There were more than three of them. They hit me with [olive tree wood] sticks, very hard…. There were four [of us] and they hit all four of us for about 30 minutes and then took us to the town of Nador. I couldn’t walk. They hit me everywhere. I was bleeding but I didn’t see a doctor. I was taken to the police station, to the refoulement cell. In there, I was fingerprinted and photographed and then put on a bus at 5 p.m [to Oujda].[69]

Jean-Luc M., the unaccompanied 12-year-old Cameroonian boy, told Human Rights Watch of his treatment after being returned from Melilla:

The Moroccans hit me…. and broke my arm. I was put in a police car and taken to the hospital. I received medical attention, and the next day, the police came to get me. I was barefoot and put on the [police] bus straight away. I was left behind the [Oujda] airport and came back to Oujda barefoot. [70]

Jean-Luc said Moroccan security forces hit him on three separate occasions.

MSF’s March 2013 report, “Violence, Vulnerability and Migration: Trapped at the Gates of Europe,” documents injuries from police violence sustained by sub-Saharan African migrants in Morocco’s Oriental region. It says that MSF provided medical assistance to 500 people in Oujda and 600 people in Nador for violence-related injuries in 2012.[71] According to MSF, 64 percent of migrants claimed that their injuries were caused by direct violence by Moroccan security forces, 21 percent said that thieves assaulted them, and 7 percent said they were beaten by the Spanish Guardia Civil.

Human Rights Watch finds that this excessive use of force by Moroccan security forces at the border with the Spanish enclave of Melilla against migrants, and the violence migrants endured at their informal settlements, has at times reached the level of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, in violation of human rights law. Persistent abuses of this nature against migrants may cause serious psychological harm to them, in addition to the physical harm they may have already suffered.

Spanish Authorities’ Use of Force and Summary Removals in Melilla

Many migrants travel to Morocco with the aim of reaching Europe, usually by attempting to enter one of the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla. Migrants who try to cross into the enclaves hope to go undetected until they reach the CETI migrant detention center ( Los Centros de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes – Centers for the Temporary Stay of Immigrants), which they perceive to be a potential stepping stone for reaching mainland Spain and being able to stay in Europe.

Fourteen of the 15 migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch who succeeded in crossing the Melilla border reported that the Spanish Guardia Civil used force against them. Eight migrants said that the Guardia Civil at the border kicked them with boots and beat them with police batons when they crossed into Melilla.

Jean-Luc M., the 12-year-old migrant boy from Cameroon, told Human Rights Watch about police brutality that he said he suffered on two occasions, just after crossing into Melilla:

In early October [2012 and November 2012], I got across the third fence and entered Melilla. The Guardia Civil hit me; they shocked me with a neutralizer [apparently a Taser]. Both times I was hit with boots and belts…. . They didn’t ask me anything and gave me back to the Moroccans. [72]

Another migrant, Omar B., described similar violence:

My first attempt [to cross from Morocco to Melilla] was in April 2012 around 2 a.m., but the police used teargas and beat us on our joints. I was able to run away and hid in the forest [in Morocco]. My second attempt was in July, during Ramadan. We succeeded in jumping over the fence but the Guardia detained us before arriving to the camp where migrants live. We were 27 people. [The Guardia Civil] beat us with sticks and handcuffed our hands. They made us walk to the border gate and handed us over to the Moroccans. They [the Moroccans] later beat us on our legs with batons. [73]

François F., a 28-year-old migrant from Cameroon, made three attempts to enter Melilla, and was summarily returned each time. He said, “I made it to Melilla, but the Guardia Civil has heat sensors and arrested us. They hit three guys with sticks and told us not to come back.” [74]

MSF also reported that the Guardia Civil used rubber bullets at the end of 2012 to prevent migrants from entering Melilla. As stated in their report, “In late 2012 MSF teams treated patients who stated that the Guardia Civil used rubber bullets to apprehend them and beat them.”[75]

Of the 15 migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch who successfully crossed into Melilla, 11, including 5 children, said the Spanish authorities handed them over directly to the Moroccan authorities without determining whether they were in need of international protection. (The other four migrants reported that they were returned to Morocco, but not directly handed over to the authorities). In doing so, the Guardia Civil contravened Spain’s obligations under the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, which includes a right to seek asylum, and the EU returns directive. This directive, adopted in 2008 by the European Parliament sets out minimum standards for the treatment of undocumented migrants during returns, and requires EU member states to ensure that any returns to countries outside the EU respect the principle of nonrefoulement, and take account of the right to family life and the best interests of the child.[76]

The migrants who spoke with Human Rights Watch said that the Spanish authorities followed none of these procedural requirements before handing them over to Moroccan authorities.

Summary removals put the migrants at risk of further violence by Moroccan security forces and at risk of being expelled into Algeria. Since numerous journalists and NGOs have reported abuses by Moroccan security forces, it is reasonable to expect that the Spanish authorities should be aware that migrants face a risk of ill-treatment at the hands of the Moroccan authorities. [77] For this reason, as well, these summary removals may also constitute a violation of Spain’s obligations under EU and human rights law.

Several migrants told Human Rights Watch, they begged the Guardia Civil not to return them to the Moroccan authorities because of the violence the migrants expected to face in custody. One migrant, Nicolas E., described his encounter with the Guardia Civil:

I was alone and I was running across to the third fence. The Guardia Civil intercepted me and told me that I would be taken to the campo [CETI] after the hospital [because he was injured] but instead they sent me back to Morocco. They told me, “Get the hell out! You know that if you come here, you know you get a caning…. You know you are going to be hit [by the Moroccans].” [78]

Expulsion of Children from Melilla

In addition to subjecting children to violence, Spanish authorities have sometimes expelled unaccompanied migrant children without due process in violation of international human rights law, the EU returns directive, and the EU Action Plan on Unaccompanied Minors (2010 – 2014). [79]

As one unaccompanied 17-year-old migrant from Guinea, Loïc E., described his expulsion to Human Rights Watch:

The Guardia Civil expelled me twice. There was no opportunity to give an interview or my story. They don’t ask your age or anything, they just expel you. The Guardia Civil handed me over to the Moroccan military who hit me with wood everywhere [on my body].[80]

In the three cases examined by Human Rights Watch, Spanish border officials failed to screen adequately for unaccompanied children or to give asylum seekers the opportunity to lodge claims for international protection. By removing migrants so rapidly, Spanish authorities in Melilla violated the children’s rights to see specialized service providers and interpreters and to receive information about applying for asylum.