To: Aurora Torrejón Riva de Chincha

From: Women's Rights Division of Human Rights Watch

Re: Law of Protection from Family Violence

Domestic violence is a widespread problem in Peru, and women, overwhelmingly, are its victims. In 1998, the National Police received nearly 28,000 reports of domestic abuse.(1) Yet with many victims reluctant to report domestic violence, the real number of women who live in violent interpersonal relationships almost certainly is much higher. For example, a 1999 survey undertaken by the National Institute of Statistics in metropolitan Lima found that no less than 82 percent of the 2,460 women who were interviewed said that they knew someone who had suffered some kind of domestic abuse within the previous twelve months.(2)

The state authorities in Peru have taken a number of steps to address this problem in recent years, and notably, Peru was among the first countries in Latin America to adopt special legislation on domestic violence. The Law for Protection from Family Violence (hereinafter "Family Violence Law"), first adopted in 1993 and subsequently strengthened in 1997, established a distinct and expedited procedure for dealing with cases of domestic violence and sought to define more clearly the respective roles and responsibilities of those within the justice system who are involved with such cases.(3)

In addition, since the late 1980s, twelve women's police stations have been established specifically to respond to violence within the home and twenty specialized sections have been created within regular police stations for the same purpose. Further, a system of Municipal Defender's Offices (Demunas) put in place since the early 1990s has taken on an increasing role in responding to the needs of victims of domestic violence. The most recent innovation has been a system of one-stop centers for victims of domestic violence, where women can find under one roof women police officers, medical examiners, and state prosecutors. The Ministry for the Promotion of Women and Human Development (PROMUDEH) has inaugurated nine such centers since March 1999. In addition, the vibrant non-governmental women's rights community in Peru has played a crucial role in both providing services to victims of domestic violence and pressing the government to improve its overall response to violence against women.

Despite this determined attention to domestic violence, however, as the investigations carried out by Human Rights Watch show, serious problems remain both in law and in practice. The Family Violence Law, despite its amendment in 1997, remains deeply flawed. Its definition of family violence is incomplete, effectively excluding entire categories of women as well as particular forms of domestic violence. Furthermore, the law privileges conciliation over prosecution, sending a troubling message that assaults within interpersonal relationships should be resolved through negotiation rather than sanctions.

Adding to the impact of these deficiencies, implementation in practice of the Family Violence Law is also seriously inadequate. From the very moment that they do so, those women who attempt to lodge a domestic violence complaint face a justice system which appears fraught with bias and incapable of affording them effective remedy or redress. Police are unresponsive and ineffectual; medical examinations by forensic doctors are frequently cursory and inadequate, tending to minimize injuries women have sustained through domestic violence; and state prosecutors and judges often appear to consider domestic violence insufficiently serious to warrant prosecuting and punishing the perpetrators. As a result, in practice women are afforded inadequate protection against domestic violence by the state, and this, in turn, serves only to deter women from making complaints and to mask the full extent of the problem.

Peru's international human rights obligations require that the state authorities take effective steps to ensure that women are able fully to exercise their human rights, including protecting them from threat or use of violence generally and within the family. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the American Convention on Human Rights, both ratified by Peru in 1978, require the state to ensure that all individuals enjoy the rights to life, security, and equal protection under the law, without distinction of any kind, including sex. Further, since 1982 Peru has been a state party to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which requires state authorities to exercise due diligence in investigating, prosecuting, and punishing violence against women as a form of discrimination.(4) Peru's obligations to act effectively to eliminate violence against women are also set out in the Inter-American Convention for the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women (hereinafter "Convention of Belém do Pará"), which Peru ratified in 1996.

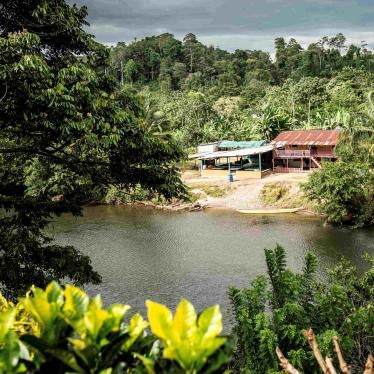

Human Rights Watch has been monitoring the state's response to violence against women in Peru for more than three years, and in this connection conducted two fact-finding missions to the country in November 1996 and December 1999. During both visits, Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed women's rights advocates, community activists, domestic violence shelter personnel, social workers, and private attorneys. We also interviewed officials of the Peruvian National Police, the Institute for Legal Medicine, the Public Ministry, the People's Defender's Office, and the judiciary. In addition, Human Rights Watch received testimonies from twenty-five women victims of domestic abuse. Most interviews were conducted in Lima, but domestic violence cases were also investigated in Tarapoto, San Martín Department, in order to assess the particular challenges that women victims in rural areas face when seeking redress. Despite the positive changes made to the Family Violence Law in 1997, Human Rights Watch found during its most recent visit to Peru that legal and structural problems continue to deny women access to genuine protection, remedy and redress.

Since November 1999, when the Commission on Women and Human Development in the Peruvian Congress established a multi-sectorial working group to review the Family Violence Law, a new and important opportunity exists to address the continuing problem of domestic violence in Peru. The working group, composed of representatives from both government ministries and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), has authority to recommend further amendment of the Family Violence Law. Upon deliberation of the working group recommendations, the Commission will present its final proposal to Congress at the end of April 2000. The Commission, it is hoped, will seize the opportunity to thoroughly examine and recommend improvements in relation to not only the provisions of the Family Violence Law but also the significant structural obstacles that prevent women victims of domestic violence from securing effective protection, remedy, and redress. This is essential if the Commission is to assist the state in carrying out its responsibility to exercise due diligence in the investigation, prosecution, and punishment of violence against women, and to ensure equal protection under the law to all Peruvian citizens, without distinction on account of their sex or other grounds.

This memorandum identifies both key deficiencies of the Family Violence Law and major problems affecting its implementation. Based on our research, Human Rights Watch has identified six priority areas for reform in law and practice. First, the Family Violence Law must prohibit all forms of domestic violence. This means the law must adopt an inclusive definition of family and intimate relationships, marital rape should be acknowledged as a kind of domestic violence, and specific forms of psychological violence, in addition to grave threats and coercion, should be explicitly included. At a minimum, this expanded, but not exhaustive, list should include stalking and repeated harassment. Second, the use of conciliation in domestic violence cases should be an option offered to victims with the benefit of free legal counsel rather than a mandatory step in the process. Third, the police must adopt report-taking procedures that respect the integrity of the victim and expedite the process. Fourth, the critical role of forensic doctors in determining whether an assault is classified as a misdemeanor or a felony means the medicolegal system deserves particular oversight to ensure that bias does not translate into the minimization of injuries. Fifth, every effort must be made to ensure that public prosecution functions properly so that women are not obliged to hire their own legal counsel to pursue their cases in court. Sixth, prosecutors and judges must act aggressively in carrying out their paramount duty to protect victims of domestic violence from further abuse. All of these steps are necessary to fulfill Peru's international obligations to combat violence against women.

Reforming the Law

Four years after it was first adopted, the Peruvian Congress recognized the need to strengthen the Family Violence Law. The law was thus amended in 1997, among other things, to expand the definition of family violence, improve victims' access to forensic medical examinations, and further clarify police and other procedures. The modified law defines family violence as "any act or omission that causes physical or psychological harm, mistreatment without injury, including grave threats or coercion, that occur between: a) spouses; b) co-inhabitants;...f) those who live in the same domicile, as long as there does not exist any contractual or labor relationship,"(5) and it delineates the roles that the police, the Public Ministry, and the judiciary should assume in the prevention and prosecution of family violence. The law is also applicable to ascendants, descendants, and relatives to the fourth degree of consanguinity and second degree of affiliation. This memorandum is concerned only with violence in intimate relationships between adult men and women.

As a whole, the 1997 amendments improved the original law significantly. However, these amendments did not address all of the shortcomings in the law and left intact particularly troubling aspects. Significant oversights have meant that groups of people are excluded from the law and certain injuries escape proscription. First, intimate partners not living together when the violence occurs are not covered under the law, denying many women the protections it established. Second, the law does not recognize sexual violence as a type of domestic violence. Third, while the law acknowledges psychological violence as domestic abuse, it fails to provide an expanded list of acts that would constitute such violence. Fourth, the law makes conciliation mandatory for anyone who reports domestic violence.

Cohabitation Requirement

The Family Violence Law only extends protection to women from their abusive intimate partners in cases where the abuser resides with the victim.(6) This excludes from protection all women not actually living with their abuser at the time of assault. This assumption, that domestic violence can only occur between men and women living under one roof, ignores reality and effectively endangers women's lives. Women are often stalked, harassed, battered, or raped by men with whom they share or have shared an intimate relationship, whether or not they have ever lived together. Similarly, violence can continue long after cohabitation has ceased. Jacinta Suárez, for example, one of the victims of domestic violence interviewed by Human Rights Watch, had moved from her abuser's home to that of her sister, but her abuser kept following her, forcing her to have sex with him, and, at least once, raped her at knifepoint.(7) The Convention of Belém do Pará recognizes the range of relationships in which women may encounter violence. It defines violence against women as, inter alia, that which "occurs within the family or domestic unit or within any other interpersonal relationship, whether or not the perpetrator shares or has shared the same residence...(emphasis added)."(8)

Marital Rape as Domestic Violence

In addition to excluding groups of women, the Family Violence Law also excludes a significant form of domestic violence: marital rape. Rape is a felony offense against sexual liberty in Peru, and the exemption for marriage was removed in the 1991 Criminal Code of Peru.(9) Nearly half of the women we spoke with in 1996 and 1999 had suffered rape or other kinds of sexual violence in their relationships. Under the current system, women who have been raped by their intimate partners cannot report the assault as physical domestic violence. They have two options: either file a psychological abuse complaint under the Family Violence Law, or file a standard criminal rape complaint. If they pursue this latter option, women filing a rape complaint do not have access to the streamlined process envisioned in the Family Violence Law. In theory, women reporting domestic violence can secure an immediate protection order, while this is not available in rape cases. Another disadvantage is that women who file a rape complaint must themselves pay for their sexual violence forensic examination, while the examinations for domestic violence complainants are carried out free of charge.(10)

Psychological Violence

Unlike sexual violence, psychological violence is explicitly prohibited in the Family Violence Law. Psychological violence is a significant problem in Peru: nearly one quarter of the 27,935 domestic violence complaints lodged in 1998 was for psychological violence.(11) Yet there is considerable confusion throughout the judicial system over what constitutes psychological violence and how to make it an actionable offense. This is due, in part, to the fact that the Family Violence Law fails to specify any acts that amount to psychological abuse beyond mentioning "grave threats and coercion." A study commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank proposes a long, if not exhaustive, list of the forms psychological violence can take. These include, but are not limited to, destructive criticism, threats of abandonment or abuse, constant or frequent persecution (e.g. stalking), and surveillance.(12)

Conciliation

Under the Family Violence Law, women who report domestic violence are obligated to undergo a conciliation session with their abusers before prosecution can proceed. The law requires that family prosecutors summon the victim and perpetrator of domestic violence for a conciliation hearing.(13) Although we understand that this reflects a general trend in Peru toward extrajudicial conflict resolution, we are concerned that the requirement that women accept the use of conciliation in domestic violence cases may be singularly inappropriate in a large number of cases. The fact that prosecutors assume a central role in conciliation communicates to the abuser, the victim, and the community at large that domestic violence constitutes a lesser offense.

In practice, conciliation sessions impose inappropriate obligations on the victims of violence, divert cases from prosecution, and delay victims' access to concrete remedies. The agreements reached in these sessions are rarely enforced, and non-compliance carries only a minimal penalty. In this context, many cases of domestic violence are not treated as they should be, as crimes that should be prosecuted and punished, but rather are mediated between the parties as if they were civil disputes between equal parties with legitimate competing claims.

Human Rights Watch has learned of agreements that included commitments by the victim of abuse to "take responsibility for all domestic tasks" or "agree to leave work and go directly to the house."(14) These obligations imply that the problem is not the violence, but rather the victim's behavior. This is entirely wrong. Women's rights activists and attorneys repeatedly complained that prosecutors prioritize family unity over the woman's safety and integrity. In every domestic violence case documented by Human Rights Watch in which prosecutors conducted a mandatory conciliation hearing, the women reported that they had been pressured by the prosecutor to preserve the relationship; in some cases, prosecutors explicitly condoned the abuse and urged the women to modify their behavior. For example, summoned by the prosecutor to a conciliation hearing, Irma Quispe's partner admitted to beating her but said this was because she was stubborn and had refused to obey him. The prosecutor then reprimanded Quispe, stating, "So you're stubborn? You have to obey your husband. You have to do right by your children and improve."(15)

The mandatory conciliation requirement puts women at risk of long drawn out proceedings during which they receive little or no protection from further abuse. Further, the Family Violence Law allows prosecutors to reinitiate conciliation proceedings after they have been suspended because the victim had felt pressured or insecure or had expressed a desire to desist.(16) Thus, prosecutors can and do allow conciliation proceedings to drag on without providing protection measures for the victim in the meantime. These delays can result in dire consequences as in the case of Raquel García. The prosecutor summoned García's husband four times before he appeared for their first conciliation hearing. Then, despite García's appeal for a protection order to remove him from her house, the prosecutor instead made her husband sign an agreement not to hurt her anymore. Less than a month later, he assaulted her again, only for the prosecutor to summon both of them for another hearing more than a month later. The violence escalated following this summons: García's husband beat her severely, drenched both her and her bed in beer and water, and forced her to remain in such conditions throughout a cold night. The prosecutor set yet another hearing, García's husband failed to appear until the fourth summons, and once again the prosecutor drafted another conciliation agreement. When Human Rights Watch met García, she was living in a shelter, ever fearful of her husband's threats.(17)

Moreover, there is no meaningful punishment for failure to honor conciliation agreements. Breaches of such agreements generally go unpunished. After María Dominguez reported her husband for domestic abuse, for example, the family judge in Cono Norte facilitated a conciliation agreement in January 1998 under which her husband agreed to leave the house within two months. Yet when Human Rights Watch interviewed her nearly two years later, he was still living there and refusing to comply with the agreement.(18) Even when enforced, the law provides only minimal punishment for non-compliance with conciliation agreements. Prosecutors and judges can only cite defendants for contempt, which usually takes the form of a reprimand, rarely a fine, and never imprisonment.(19)

Human Rights Watch urges the Commission to do the following:

- Ensure that all victims of domestic violence are protected under the Family Violence Law. The requirement that the man and woman involved be living in the same residence when the violence occurred should be eliminated.

- Include explicitly marital rape as a form of domestic violence.

- Specify explicitly, but not exhaustively, acts that constitute psychological violence apart from grave threats. This list should include, at a minimum, stalking and repeated harassment.

- Abolish the mandatory nature of conciliation procedures in domestic violence cases. If the procedure is to be preserved, it should be offered to victims as an option. Victims should have the benefit of free legal aid in making the decision to engage in conciliation over their other options.

- Eliminate the role of the prosecutor in conciliation.

- Ensure that those who remain authorized to conduct optional conciliation hearings in family-related matters (such as judges and Demunas personnel) receive thorough, rigorous, and continuous training in conflict resolution techniques. This training should also seek to eliminate gender bias among these practitioners.

- Establish effective mechanisms in the criminal law system for sanctioning non-compliance.

Addressing Problems with Implementation

Bias throughout the justice system against taking domestic violence seriously thwarts meaningful implementation of the Family Violence Law and compromises women's access to effective remedies and redress. There are four critical ways in which this bias is expressed. First, the police are often unresponsive or even hostile to women who report domestic violence. Second, forensic doctors in the Institute for Legal Medicine (IML, its Spanish acronym) frequently minimize injuries sustained in domestic violence incidents. Third, state prosecutors fail to duly investigate and prosecute domestic violence cases, preferring to hold mediation hearings even when the victim's life may be at risk. Because she cannot count on prosecutors to perform their duties, a victim must hire her own legal counsel to usher her case through the system if she wishes to see her batterer held accountable. Fourth, neither prosecutors nor judges make sufficient use of protection measures to shield women from future violence.

Police Procedures

Whether women can even begin to seek protection from their abusers depends crucially on the responsiveness and competence of the police. Most women report domestic violence to their local police station or a specialized women's police station.(20) The Family Violence Law stipulates that the police have the duty to investigate all reported cases of domestic violence, regardless of whether the victim pursues the charges and, at the request of the victim, can provide guarantees (protection) to safeguard her integrity.(21) The police are also empowered to search the home of the accused, in cases of delicto flagrante or when there is "a very grave danger" of the commission of a crime. When the police apprehend perpetrators in the act of committing domestic abuse, they can detain them for up to twenty-four hours.(22)

Because filing a complaint with the police is the principle and first avenue for gaining access to the justice system, barriers at this stage can, and often do, deny women's access to redress. Human Rights Watch documented troubling deficiencies in the performance of the police. These include mistreatment of women filing complaints, inadequate investigations, unnecessary delays, and practices that jeopardize women's safety and physical and psychological integrity.

Virtually every case we investigated involved initial police rejection of the complaint. The women we interviewed said they encountered incredulity and abusive treatment when they attempted to report violence in their interpersonal relationships. This is particularly true for women reporting intimate partner rape. The ranking officer at the Lima Women's Police Station expressed his bias against such claims, saying "When a woman reports this...the question remains, to what extent can we say it's rape between a couple...to what extent does a couple find [sexual] satisfaction through violence? It confuses us."(23)

Victims of psychological abuse and women's rights activists told Human Rights Watch that there is widespread reluctance to recognize and accept psychological violence as a real harm to be investigated. When police officers, often the first to hear reports of domestic violence, refuse to take psychological violence seriously, as in Altagracia Huamán's case, victims are effectively denied redress and protection. When Huamán tried to file a complaint for psychological abuse because her husband continued to stalk and threaten her after she moved out, the attending officer at the Chorrillos police station reportedly asked her, "Why, are you crazy?" and refused to register her complaint.(24)

Many women we spoke with described more than one thwarted attempt to report domestic abuse, of all types, and to seek protection.(25) When the police do accept complaints, Human Rights Watch found that their investigations are usually limited to sending the victim to the forensic doctor, picking up the results, and summoning the assailant for an interview.

Police often require women to undergo a forensic examination before they can file an official complaint for domestic violence. Indeed, the ranking officer at the Lima Women's Police Station stated to Human Rights Watch that this is standard operating procedure: "it is better to take the statement after the forensic exam [because] a lot of people come here in the heat of the moment."(26) This requirement has no grounding in law and imposes an undue delay in the process. The police are not required to accompany victims to the nearest forensic doctor or state health facility and rarely do so. In central Lima, the IML offices are just across the street from the women's police station. In many areas, however, women must travel significant distances to get their exam at the only IML office in the department or at a state-run health facility. Until a recent reform in early 2000, the police were required to pick up the medical certificates, which could take anywhere from five days to one month.(27) Now, the IML has adopted a welcome new policy of giving the certificates directly to victims.(28) While this will expedite the process, it does not resolve the problem of police refusal to take full statements before the examination. For example, if for whatever reason the victim fails to return to the police station with her certificate, there is no official record of her statement, and police do not pursue any investigation.

In those cases in which women do make formal statements, the police must summon the alleged aggressor to take his statement. We found that in some cases, the police gave the summonses directly to the victims to deliver to their abusers. This reflects a grossly negligent disregard for the victim's safety. Several of the women we interviewed said that their abusers responded to receiving the summons by inflicting another violent attack.(29)

Human Rights Watch makes the following recommendations to the Commission:

- Clarify the duty of the National Police to take and register a victim's complete, official statement immediately. No other step, such as the forensic examination, should be required before the statement is recorded.

- Require police officers to serve police, prosecutorial, and judicial summonses directly and promptly to perpetrators of domestic violence.

- Ensure that the National Police institute disciplinary measures or, if relevant, criminal proceedings against those police officers who refuse complaints, fail to act promptly, or mistreat victims.

- Clarify that the National Police must include, without delay, a required course on domestic violence in the Police Academy curriculum. This course should train police to conduct prompt, thorough, and respectful intakes of complaints.

Role of Forensic Doctors

The paramount importance of the forensic medical certificate in determining victims' ability to seek protection and redress merits special attention. Under Peruvian law physical domestic violence can be classified as either a misdemeanor or a felony offense.(30) It is unclear, due to the ambiguities in the law as to what constitutes psychological violence, what the parameters are for determining when psychological abuse constitutes a misdemeanor and when it rises to the level of a felony. The vast majority of domestic violence cases are classified as misdemeanors. The critical actors in this process are the medical examiners charged with conducting forensic examinations and quantifying injuries to legal effect. The medical certificate is often the only evidence to corroborate victims' testimonies. Human Rights Watch documented serious problems with the medicolegal system, including inadequate and incomplete examinations, which result in the minimization of injuries sustained in domestic violence situations. The lack of clarity on psychological violence has contributed to a situation in which forensic doctors cannot fulfill their designated role in assessing injury to legal effect in these cases.

The IML physicians conduct most forensic exams. The IML was created to ensure the Public Ministry could rely on a cadre of specialized, impartial forensic doctors. IML physicians, psychiatrists, and psychologists should, in theory, be the best trained and most competent to diagnose injuries to legal effect. In areas where there are no IML facilities, physicians in state-run health centers, clinics, and hospitals conduct the forensic examinations. Private institutions may also issue medical certificates to legal effect but only if they have entered into a special agreement with the Public Ministry.(31) The Family Violence Law stipulates that all state-run facilities must issue the medical certificates free of charge to victims of domestic violence.(32)

Typically, the course a domestic violence complaint follows rests largely on the forensic doctor's diagnosis of the injuries.(33) Victims of domestic violence and women's rights attorneys and activists strongly alleged that physicians in the IML frequently minimized victims' injuries. As one attorney explained, "There's enormous room for subjectivity, and they [forensic doctors] minimize them [the injuries]. I've seen it many times: they give more days for the same kind of injury when it's a 'normal' injury, not between family members. It's enough that it's a domestic violence injury for them to minimize it."(34) We spoke with women who had suffered serious violence at the hands of their intimate partners but whose access to redress was thwarted by questionable classification of their injuries. For example, Verónica Alvarez, a thirty-six-year-old mother of four, was hit in the face with a metal typewriter by her partner, leaving her permanently scarred, yet her case was classified as a misdemeanor because the forensic doctor in Arequipa classified her injuries as needing fewer than ten days of treatment and recuperation.(35) One prosecutor even told Human Rights Watch that, based on her experience with the IML, in domestic violence cases, "none is a felony unless there is a broken bone."(36)

Diagnoses that are inconsistent with the injuries are the result, in part, of inadequate and incomplete examinations. Women reported that exams were often quick, cursory, and did not include basic tests and measurement of bruises and lacerations nor were photographs taken of their injuries. For example, Laura Alomar was beaten by her husband, thrown against the floor, repeatedly kicked, thrown against the wall, and hit in the breast with a hard object. She said that the forensic doctor who examined her did not ask her anything about her injuries and only looked over those that were plainly visible.(37) Moreover, supplementary exams, such as x-rays, that would significantly improve the quality of the medical evidence, can be difficult to obtain. The IML headquarters in central Lima, for example, did not have an x-ray machine or other basic diagnostic instruments and had to send victims to the Auxiliary Laboratory of the Central Morgue or a local hospital for additional, but in some cases essential, tests. There is some confusion as to whether these supplemental exams carry a fee. While the head of the IML, Doctor María del Carmen Contreras Marcovich, told Human Rights Watch that these are free for victims of domestic violence, as are the basic exams, a forensic doctor in the employ of the IML asserted that they did in fact carry a charge.(38) The result may be that fees are assessed for these supplemental exams, and women are either required to pay or simply do not get the tests because they cannot afford to do so. In 1996, when the basic physical exam carried a charge, our research indicated that many women never went to a forensic doctor because they had no money to do so.

Psychological evaluations, which could complement physical evidence and help provide a more complete diagnosis of the harm caused, are not routinely provided for women who lodge complaints of domestic violence. The IML may only conduct such evaluations when they are explicitly requested in a referral from a competent authority.(39) In fact, many women are not informed that they may receive both physical and psychological examinations. Hence, unless the referring authority requests a psychological examination, a victim of domestic abuse who is sent for a physical examination will not undergo any kind of psychological evaluation, effectively precluding the collection of additional evidence that could support her case.

Women seeking solely a psychological evaluation encounter another obstacle: the difficulty of translating psychological trauma into a quantifiable injury. Whereas physical injuries, at least theoretically, can be objectively assessed and classified according to the standard scale used in the Peruvian criminal justice system, the extent of psychological trauma is assessed using qualitative criteria. Human Rights Watch was told that many prosecutors in the Public Ministry are unwilling to accept psychological diagnoses as proof that domestic violence has occurred,(40) and an IML psychologist commented that judges "want a calculation of the harm, [but] we cannot quantify the harm, because we use qualitative criteria."(41)

The end result is that most cases of domestic violence are officially classified as misdemeanors, and this has profound implications for the victim's ability to secure effective protection and redress. Under Peru's Criminal Procedural Code, misdemeanors fall within the jurisdiction of justices of the peace.(42) The Family Violence Law provides that all domestic violence claims should be screened initially by a prosecutor and then referred to the appropriate judicial authority, depending on whether the prosecutor deems the offense to constitute a misdemeanor or a felony.(43) In practice, however, police frequently bypass the prosecutor and refer cases directly to justices of the peace if they consider them to constitute misdemeanors. This is not an adequate or satisfactory system. The justices of the peace are often the only judicial authority in rural areas, yet they have very limited powers to provide protection or to punish perpetrators, whether in rural or urban areas. Justices of the peace cannot issue protection orders in misdemeanor cases, for example, and have limited powers to enforce any sentences that are imposed. While a justice of the peace may order an abuser to stay away from the victim, non-compliance can only be sanctioned as contempt of the court, punishable with a small fine or community service.

Even when abusers are prosecuted, misdemeanor offenses in domestic violence cases carry a maximum penalty of no more than twenty to thirty days' community service.(44) In fact, according to women's right activists, Public Ministry officials, and judges interviewed by Human Rights Watch, neither fines nor community service are generally leveled against perpetrators of domestic violence. Indeed, none of the battered women we interviewed reported that their abusers had been either fined or compelled to undertake community service.

Human Rights Watch urges the Commission to undertake the following:

- Include in the Family Violence Law a clear delineation of responsibilities of forensic doctors in documenting domestic violence injuries. This should require the IML to improve on the current forms it uses and develop a standardized, comprehensive protocol, including information about domestic violence and clear guidelines for the collection of medical evidence and calculation of harm. The protocol should also include a detailed section on psychological violence.

- Ensure that the protocol is made available to the public and widely disseminated to all health care personnel.

- Include in Article 3 of the Family Violence Law specific actions the state should take to ensure that all employees in the IML and state health facilities are properly trained in the content of domestic violence legislation and procedures for collecting medical evidence.

- Ensure that all IML and state-employed physicians are aware of and abide by the cost exemption for all medical examinations related to cases of domestic violence, including psychological assessments.

- Call for mandatory periodic training of all justices of the peace on Peru's domestic violence legislation to ensure they understand their duty to sanction. This training should promote understanding of the dynamics of domestic violence and underscore that it cannot be excused, tolerated, or condoned under any circumstances.

Role of State Prosecutors

The strong tendency within the criminal justice system to perceive domestic violence as simply a minor offense is further reflected in the performance of state prosecutors. The Peruvian state has a clear legal obligation to investigate and prosecute in cases of domestic violence. Under the Family Violence Law, the National Police must register complaints of domestic violence and conduct preliminary investigations, and the Public Ministry must process the complaints and prosecute perpetrators. Yet Human Rights Watch found that victims of domestic violence cannot rely on the Public Ministry to pursue their cases. Women's rights activists, domestic violence attorneys, judges, government officials, and even prosecutors we spoke with all indicated that cases proceed through the legal system only when the victim has her own lawyer. The governmental Women's Human Rights Defender, Rocío Villanueva Flores, stated, "In practice, if you don't have your own lawyer, your case won't get anywhere."(45)

The manner in which domestic violence complaints are processed effectively denies victims access to the state's prosecutorial machinery. First, domestic violence cases that are classified as misdemeanors are remanded directly to justices of the peace, bypassing the Public Ministry entirely. In these cases, women victims do not have the benefit of any legal counsel and must represent themselves in hearings. Second, when cases are directed to prosecutors, the emphasis on conciliation effectively denies women the right to effective judicial redress. As discussed above, prosecutors seek to resolve cases through mediated settlements rather than by prosecuting perpetrators of domestic violence. Finally, there are simply too few family prosecutors to deal with the high volume of domestic violence cases, while in some cases, there are "mixed" prosecutors who must handle criminal, civil and family-related cases. The magnitude of the problem of domestic violence in Peru suggests the need to better equip the system to handle the increasing volume of cases.

Human Rights Watch makes the following recommendations to the Commission:

- Further clarify in the Family Violence Law the obligations of state prosecutors, both family and criminal, to actively pursue the prosecution and punishment of perpetrators of domestic violence.

- Recommend that the Public Ministry adopt and distribute national directives on how prosecutors should handle domestic violence complaints and conduct specific and periodic in-house training workshops.

Failure to Protect

The Peruvian justice system has the obligation not only to duly investigate, prosecute, and punish perpetrators, but also to protect victims of domestic violence. Indeed, the availability of immediate and effective protection measures is an essential element of state response to violence against women. Many women who report domestic violence are under constant threat or in imminent danger.(46) The Convention of Belém do Pará enshrines the right of victims of violence to rapid redress and stipulates that states should establish just and efficient legal procedures that include protection measures.(47) The inefficiency of these mechanisms in Peru has a direct impact on reporting, as women justifiably fear retaliation from their intimate partners, and effectively contributes to placing women's lives at risk. The Family Violence Law defines a role for both prosecutors and judges in providing this protection, which can include restraining orders and forced removal of the aggressor from the victim's home.(48) Human Rights Watch found, however, that implementation has so far been woefully inadequate.

All of the women's rights advocates and lawyers we spoke with concurred that neither prosecutors nor the competent members of the judiciary make adequate use of protection measures. In fact, Movimiento Manuela Ramos (MMR), a non-governmental organization that provides legal counsel to victims of domestic violence, found that prosecutors issued protective measures in only one out of forty-five domestic violence cases filed in Lima in 1996 and 1997.(49) While victims, technically, can petition judges directly for these orders--that is, if they are well versed in legal procedures, which the great majority are not--judges respond more favorably to cases initiated by state prosecutors. As one domestic violence attorney explained, "Very few women can get a protective measure on their own directly from a judge."(50) In general, Human Rights Watch found that family judges are reluctant to order precautionary measures. One civil prosecutor reported that judges had often ruled out of order requests for immediate remedies that she had made, commenting, "Some judges would limit themselves to declaring that violence had happened, but did not offer protection. Their attitude is 'better they [the victims] go to therapy.'"(51) Part of the problem here may stem from the lack of training provided to family judges in addition to the fact that they do not have the power normally to provide remedies in cases involving violent assaults.

Our research confirmed the obstacles women face in securing protection from their violent intimate partners. In her own words, Raquel García "begged" the prosecutor handling her case to make her husband leave the house, but the prosecutor simply required her husband to sign an agreement not to hurt her anymore rather than taking action to afford her effective protection.(52) In another case, protection measures were granted only with delay and then not enforced. A full two months after María Pérez sought protection against her husband because he physically abused her and habitually locked her in the house, a family judge ordered her husband to leave the house. Shortly thereafter, however, he returned and the abuse was renewed. Concerned neighbors finally reported the situation to the police; at the time of her interview with Human Rights Watch, Pérez had been living in a shelter for nearly six months to escape the abuse to which she had been subjected at her home.(53)

Human Rights Watch recommends that the Commission undertake the following:

- Streamline the process for the issuance of protection orders and precautionary measures.

- Ensure that all temporary protective orders are fully enforceable by the police.

- Require that all police stations, Demunas, IML offices, state health facilities, PROMUDEH offices, and all other appropriate agencies prominently post a list of victims' rights, including the range of protection measures available to them, written in accessible language.

1 This figure includes all victims who can report under the Family Violence Law, not only women. No disaggregated figures are available.

2 Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI) (National Institute of Statistics and Computer Science). Encuesta de Hogares sobre Vida Familiar en Lima Metropolitana. Primeros Resultados (Household Survey on Family Life in Metropolitan Lima. First Results) (Lima: INEI, July 1999).

3 Law No. 26260 was adopted in December 1993. It was amended by Law No. 26763, adopted in March 1997. The text referred to in this memorandum is the consolidated version (Texto Unico Ordenado) adopted through Supreme Decree No. 006-97-JUS, which went into effect on June 28, 1997.

4 The U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee), established under the treaty, has noted that "[g]ender-based violence is a form of discrimination which seriously inhibits women's ability to enjoy rights and freedoms on a basis of equality with men." Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, "Violence Against Women," General Recommendation No.19 (Eleventh session, 1992), (New York: United Nations), CEDAW/C 1992/L.1/Add.15, para.1.

5 Family Violence Law, Article 2. All translations are by Human Rights Watch.

6 Family Violence Law, Article 2. The implementing legislation of the Family Violence Law clarifies that ex-spouses and former live-in partners are included, but only if temporarily living in the same home when the violence occurred. Supreme Decree No. 002-98-JUS, Article 4. It should be noted that the original 1993 law included the clause "persons who have procreated children in common even if they do not live together..." Article 2, Law No. 26260 of March 1993. This was inexplicably eliminated in the amended law.

7 Human Rights Watch interview, Jacinta Suárez, Lima, November 9, 1996. All names of domestic violence victims have been changed at their request.

8 Convention of Belém do Pará, Chapter I, Article 2(a).

9 Criminal Code of Peru, Title IV, Chapter VI, Article 170. The Criminal Code was modified in May 1999 to make the non-aggravated rape of females over fourteen years of age a public action crime: the state now has an obligation to prosecute. Before, the victim had to pursue private prosecution: she was named a party in the suit against the perpetrator, and had to hire an attorney to direct the prosecutorial investigation of the crime, develop the case, and present evidence against the accused in court. While the state always had the obligation to prosecute the rape of minors (under fourteen years of age) and aggravated rape, as of the modification, it has now assumed these obligations in rape where the victim is an adult woman, regardless of aggravating circumstances. Law No. 27115 of May 15, 1999.

10 As a result of the 1997 amendments, Article 29 of the Family Violence Law stipulates that all state health facilities must issue the forensic medical certificates in domestic violence cases free of charge. Law No. 27016, adopted in December 1998, further modified Article 29 of the Family Violence Law to clearly state that the exam itself is free, and to mention specific health care facilities that are under the obligation to conduct the exams and issue the certificates free of charge and to legal effect in cases of domestic violence. Law No. 27016, Article 1. According to an official with the Institute of Legal Medicine (iml), the cost for a sexual assault examination is 8 Nuevos Soles (U.S.$2.50); however, a sign at the IML headquarters in central Lima read: "Medical Exam (Sexual Honor): 37 Nuevos Soles" (U.S.$11.85). (Reconocimiento Médico (Honor Sexual)). Public Ministry, Lima, December 15, 1999. In theory, indigent women can have the fee waived; we found, however, that most women are not aware of this option.

11 Ministry for the Promotion of Women and Human Development (PROMUDEH). Preliminary Report on the Advances of the Beijing Platform of Action. (Forthcoming, Lima: PROMUDEH, 2000), Paragraph 119.

12 The full list of acts constitutive of psychological violence is as follows: "...destructive criticism; insults; emotional blackmail; mockery or ridicule; threats of abandonment or abuse; prohibition to go out to work or to have contact with other people; confinement to the home; surveillance; constant or frequent persecution; unreasonable restriction of access to and management of joint property; denial of food or rest; threats to take away custody of children or to harm them; destroying objects belonging to the person; or failing to provide for the basic needs of the family when such provision is possible." Efraín Gonzales de Olarte and Pilar Gavilano Llosa, "Does Poverty Cause Domestic Violence? Some Answers from Lima" in Andrew R. Morrison and María Loreto Biehl, eds., Too Close to Home: Domestic Violence in the Americas (Washington DC: Inter-American Development Bank, 1999), p.36.

13 Family Violence Law, Article 13. Family judges can also conduct conciliations (Article 23). The Municipal Defender's Offices (Demunas) are now empowered to conduct extrajudicial conciliation hearings in cases of domestic violence; the agreements they facilitate are legally binding. Law No. 27007, Article 3.

14 Movimiento Manuela Ramos (Manuela Ramos Movement, MMR), La Violencia Contra la Mujer. Aplicación de la Ley de Violencia Familiar desde una perspectiva de género: Estudio de casos (Violence against Women. Application of the Family Violence Law from a Gender Perspective: Case Studies) (Lima: MMR, 1998), p.63.

15 Human Rights Watch interview, Irma Quispe, Tarapoto, November 9, 1996.

16 Family Violence Law, Article 13.

17 Human Rights Watch interview, Raquel García, Lima, October 27, 1996.

18 Human Rights Watch interview, María Dominguez, Lima, December 16, 1999.

19 Human Rights Watch telephone interview, Gina Yáñez, director, Human Rights Program, MMR, Lima, August 11, 1997.

20 It should be noted that the Women's Police Stations, first established in 1988 to provide specialized attention to cases of family violence, are not authorized to investigate felony battery.

21 Family Violence Law, Article 6.

22 Ibid., Article 7.

23 Human Rights Watch interview, Major Eduardo Calderón Cueto, Lima Women's Police Station, Lima, December 14, 1999.

24 Human Rights Watch interview, Altagracia Huamán, Lima, November 8, 1996.

25 Human Rights Watch interviews: Raquel García, Lima, October 27, 1996; Amparo Torres, Lima, November 9, 1996; Altagracia Huamán, Lima, November 8, 1996; Verónica Alvarez, Lima, November 14, 1996; María Dominguez, Lima, December 16, 1999; and Gloria Sánchez, Lima, December 16, 1999.

26 Human Rights Watch interview, Major Eduardo Calderón Cueto, Lima Women's Police Station, Lima, December 14, 1999.

27 Human Rights Watch telephone interview, Doctor María del Carmen Contreras Marcovich, Technical Director, IML, Lima, February 25, 2000.

28 Ibid.

29 Human Rights Watch interviews: Raquel García, Lima, October 27, 1996; Cristina Fernández, Lima, November 8, 1996; Alma Martínez, Lima, November 8, 1996; and Jacinta Suárez, Lima, November 9, 1996.

30 The Family Violence Law does not create an autonomous crime of domestic violence nor does it include penalties for this kind of violence. Rather, it defers to the Criminal Code of Peru for the definition of misdemeanor and felony assault, as well as for the respective penalties. The Criminal Code establishes a system whereby assaults are classified according to the number of days resulting injuries require for treatment and disability leave. Intentional injuries requiring ten days or fewer are categorized as misdemeanors (Book III, Title II, Article 441); those requiring more than ten but fewer than thirty days are simple felonies (Book II, Title I, Chapter III, Article 122); and those requiring more than thirty days, causing permanent mutilation, disfigurement, or incapacity or placing the victim's life in imminent danger, are classified as aggravated felonies (Book II, Title I, Chapter III, Article 121). The code was modified in 1997 to stipulate that misdemeanor offenses can rise to the level of felony when the injuries are sustained in domestic violence. The modification leaves this determination to the discretion of the judge (Book III, Title II, Article 441).

31 Family Violence Law, Article 29.

32 Most IML examinations carry a fee. The exceptions are the following: 1) domestic violence cases; 2) minors; and 3) when requested by a prosecutor or judge. The fees vary according to the type of examination.

33 The IML has standardized forms for the different types of examinations it conducts. There is a form for domestic violence.

34 Human Rights Watch interview, Giulia Tamayo, women's rights attorney, Lima, December 14, 1999.

35 Human Rights Watch interview, Verónica Alvarez, Lima, November 14, 1996.

36 Human Rights Watch telephone interview, anonymous civil prosecutor, Lima, September 22 and 25, 1997.

37 Human Rights Watch interview, Laura Alomar, Lima, November 8, 1996.

38 Human Rights Watch telephone interview, Doctor María del Carmen Contreras Marcovich, Technical Director, IML, Lima, February 25, 2000; Human Rights Watch interview, anonymous IML doctor, December 15, 1999.

39 These authorities are the National Police, prosecutors, judges, and the Demunas.

40 Human Rights Watch interview, Silvia Paz, domestic violence attorney, Estudio para la Defensa de los Derechos de la Mujer (DEMUS), Lima, December 14, 1999.

41 Human Rights Watch interview, anonymous IML forensic psychologist, Lima, December 17, 1999.

42 Criminal Procedural Code of Peru, Article 24.

43 Family Violence Law, Article 8. The same article stipulates that police refer felony offenses to the provincial criminal prosecutor's office.

44 Criminal Code of Peru, Book III, Title II, Article 442

45 Human Rights Watch interview, Rocío Villanueva Flores, Women's Human Rights Defender, Lima, December 17, 1999.

46 Article 7 of the Family Violence Law authorizes the police to enter a home in case of flagrante delicto or the "very grave danger" of the commission of a felony assault. Where a perpetrator is apprehended in the act of committing the crime, the police can detain him for up to twenty-four hours. In practice, this is rarely enforced because, by its very nature, incidents of domestic abuse rarely occur when police are present.

47 Convention of Belém do Pará, Article 4(g) and Article 7(f), respectively.

48 Family Violence Law, Articles 10 and 11. Prosecutors can dictate protection orders (medidas de protección), while only judges can issue precautionary measures (medidas cautelares). In concrete terms, the range of measures available to each is the same; the difference is that traditionally, only judges have had the authority to issue these kinds of injunctions and then, usually only once a case has reached the court. The Family Violence Law gives prosecutors the ability to issue these protection orders, but he or she must seek confirmation by the appropriate judge once the order is issued. Because they are in effect the same thing, in this document we use the term "protective order" or "protection order" to refer to both.

49 MMR, La Violencia contra la Mujer (Violence against Women), pp.70-71.

50 Human Rights Watch interview, Grecia Rojas, attorney, Flora Tristán Women's Center, Lima, October 28, 1996.

51 Human Rights Watch telephone interview, anonymous civil prosecutor, Lima, September 22 and 25, 1997.

52 Human Rights Watch interview, Raquel García, Lima, October 27, 1996.

53 Human Rights Watch interview, María Pérez, Lima, December 11, 1999.