Over the weekend, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger of California vetoed legislation that would have made California the first state in the nation to collect comprehensive data on the physical evidence collected from rape victims that is sitting in police storage facilities. The bill, AB1017, which sailed through both houses of the state legislature, had been hailed by advocates as model legislation and an important first step in reckoning with the huge backlog in the United States. But Governor Schwarzenegger, citing the time and money it would take law enforcement agencies to collect the data, decided to oppose a law that would help bring justice to rape victims.

Every year in the United States, more than 200,000 people report to the police that they have been raped. Many are asked to submit to this collection of DNA evidence from their bodies, which is stored in a small package called a rape kit. It is an invasive and sometimes traumatic process that takes four to six hours. But the potential benefits are enormous: testing the DNA evidence can identify an unknown rapist, confirm the identity of a known assailant, corroborate the victim's account, and exonerate innocent suspects.

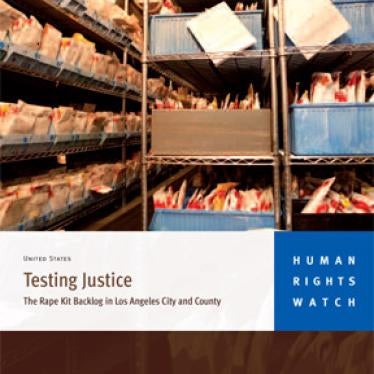

When a victim undergoes the examination to collect a rape kit, both she and the public reasonably assume that the kit will be tested. But all too often, that is not the case.Why does reporting rape kit data matter so much to rape victims and their advocates? When Human Rights Watch began researching the rape kit backlog in Los Angeles, we heard powerful stories from rape victims whose kits had not been tested. Without hard numbers, however, it was difficult to generate the political will to fix the problem. Obtaining these numbers proved our most difficult-and vital-task.

A March 2009 report by Human Rights Watch found that in the Los Angeles area alone, there were more than 12,500 untested rape kits. Our research strongly suggests that backlogs are not unique to Los Angeles. Every major jurisdiction we have examined that does not have a clear policy of testing every kit booked into police evidence has such a backlog. We are not aware of any jurisdiction in California that has a mandatory testing policy outside of the recently revised policies of the Los Angeles Police and Sheriff's Departments.

Under the California Public Records Act, law enforcement agencies can be required to report the number of rape kits they have inventoried and counted. But if they don't count them, it becomes a Catch 22 situation: technically there is no information to report, as if the kits in storage did not exist. It took nearly nine months of advocacy and public education to get the Police and Sheriff's Departments in Los Angeles to count their untested rape kits. And it was not until the numbers were publicized that law enforcement was compelled to change its policies.

Now that the extent of Los Angeles' backlog is known, immense progress has been made toward its elimination. The Los Angeles Police and Sheriff Departments have made commitments to count and test every rape kit collected from a victim and booked into evidence.

California needs to replicate this level of commitment to rape victims throughout the state. Los Angeles should not be the only city in California where rape victims can be assured that the evidence from their crimes will be inventoried and tested. Only through annual reporting to the Department of Justice will California law enforcement provide accountability to those victims who entrust them with the future of their cases.

Expecting law enforcement to keep track of evidence from serious violent crimes doesn't seem like too much to ask. The lawmakers who passed this bill understood that. But by vetoing this bill, Governor Schwarzenegger missed an opportunity to signal to rape victims that their cases matter enough to require even this minimal effort.