Civilians in Syria’s war zones are on their own these days, with different sides doing everything they can to stop independent witnesses, like journalists and human rights researchers, from reaching the battlefield. Despite this, in October 2020, Human Rights Watch published a 167-page report on 46 attacks by Syrian and Russian forces that destroyed civilian infrastructure in Idlib governorate, Syria. Without setting foot on Syrian soil, we exposed apparent war crimes and the abusive military strategy that drove more than one million civilians from their homes. We wanted to show you more about the methods and approach.

Airstrikes in Idlib

Belkis Wille, Senior Crisis and Conflict Researcher. Based in Yangon, Myanmar

Belkis Wille, Senior Crisis and Conflict Researcher. Based in Yangon, Myanmar

By March 2020, Idlib was one of the last anti-government holdouts in northwest Syria. Fighting had raged in Syria for almost a decade, creating 5.5 million refugees and 6.2 million internally displaced people, and rebels threatened the autocratic rule of President Bashar al-Assad, until he forged a military alliance with Moscow. Since then, a Syrian-Russian military alliance repeatedly bombed hospitals, schools, and markets. The United Nations, foreign governments and human rights groups condemned these attacks, which violated the laws of war, to no avail.

We were so frustrated about documenting the endless atrocities with limited effect. We wanted to look further, to dig deeper and examine the strategy used by the Syrian and Russian militaries that caused so much harm to civilians. We felt it wasn’t a coincidence they kept bombing hospitals and schools, the lifeline for civilians still left in Idlib. So we examined the pattern of attacks, to test a common allegation: that Syria and Russia were intentionally targeting civilian infrastructure to drive Idlib’s civilians from their homes and help the Syrian army to retake territory. Understanding the military strategy behind the attacks proved critical for us to then craft the right advocacy messages to those in power, to get them to bring a stop to war crimes in Syria.

Syria's President Bashar al-Assad (left), Russia's President Vladimir Putin (right), Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu (second right), and Lieutenant-General Alexander Yuryevich Chaiko (third right) during a meeting. © Alexey DRUZHININ / SPUTNIK / AFP

Screenshots from video show President Putin making remarks at the Damascus command post for Russian forces during a January 7, 2020 trip to Syria.  Russian Federation Ministry of Defense

Russian Federation Ministry of Defense

In early March I flew to Antakya, southern Turkey, just across the border from Idlib, where a ceasefire had just been agreed. The Turkish government, which keeps the border closed, didn’t grant me permission to cross, so I met people who had escaped Idlib, people who were in contact with rescue workers, doctors, teachers, and lawyers still trapped in the besieged region. I wasn’t sure if we could gather enough evidence to make our case without entering Syria.

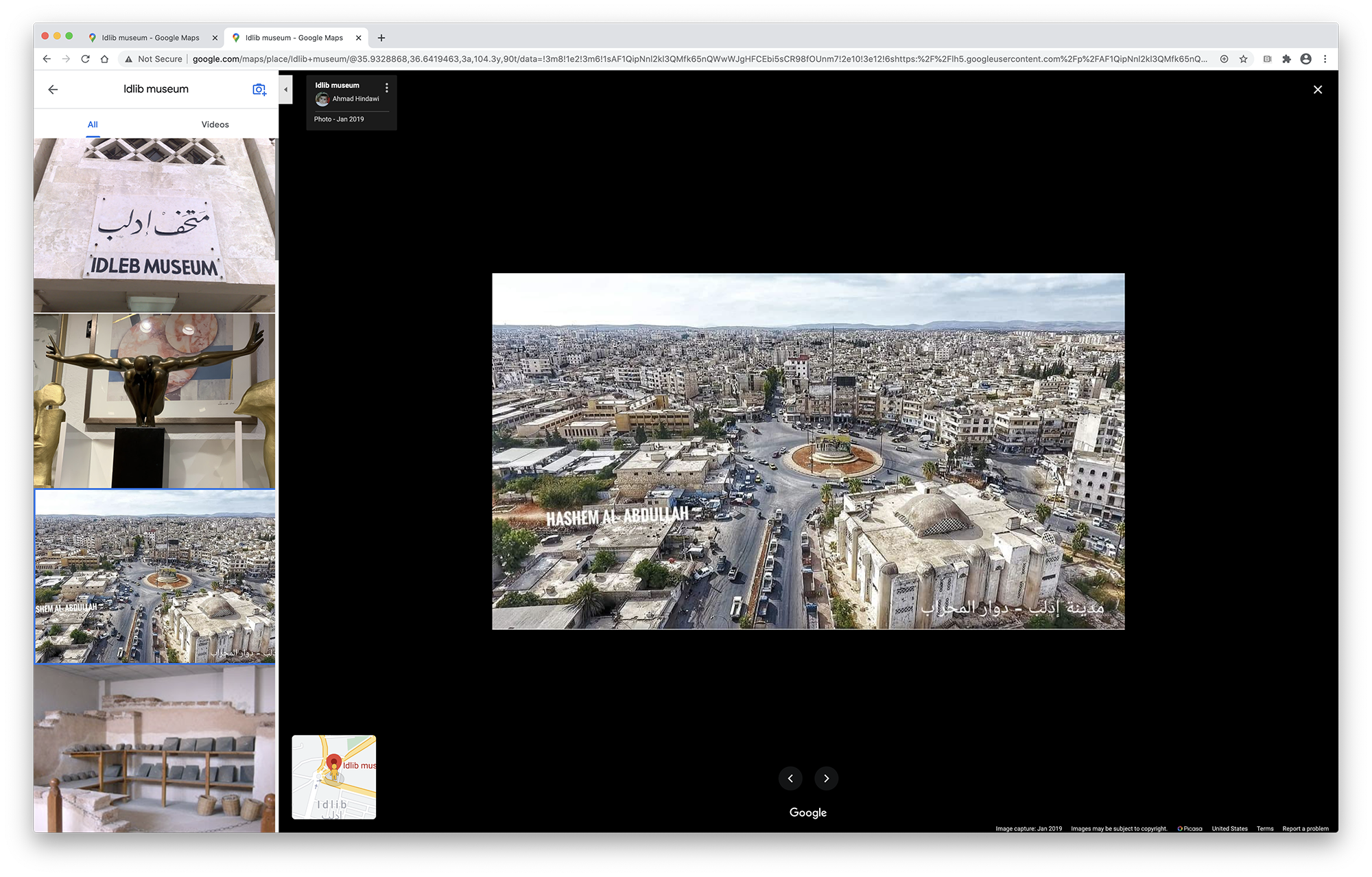

At a café in Antakya one evening, a Syrian lawyer told me about an attack he witnessed in Idlib City on January 15. A strike had hit a grocery stall in the vegetable section of a main market, he said, just after 2 p.m. His friends put us in touch by phone with another witness to the attack, Ayman Assad, who ran a car repair shop nearby.

Ayman said that a few minutes after he heard the explosion in the market, two bombs hit shops just 50 meters from where he was standing. Ayman and the lawyer, as well as rescue workers we interviewed, said the attacks had a devastating impact. From their accounts, we determined that the attacks killed at least 22 civilians, wounded another 65, and destroyed at least 20 shops. The entire market was shut for several days.

I called my colleague Richard Weir to see if his Syrian contacts could help us investigate.

Richard Weir, Crisis and Conflict Researcher. Based in Beirut, Lebanon

Richard Weir, Crisis and Conflict Researcher. Based in Beirut, Lebanon

I knew when Belkis called that we had to find a way to make sense of each incident in this stream of attacks and that we would need a variety of sources to help us understand them. In this case, we had an incident, date, time, location, and a witness, but we needed more.

In Idlib, a network of people monitor aircraft movements in Syria and share encrypted messages on the presence of aircraft, sometimes identifying the type of aircraft they are seeing from below. I opened the Telegram messaging app, scrolled through two months of messages, and found posts from the afternoon of January 15, 2020. The group’s messages said the network had identified a plane flying over Idlib City moments before the two attacks. It seemed likely that this plane could have launched the strikes that Ayman Assad and others said they witnessed that day.