Abandoned by the State

Violence, Neglect, and Isolation for Children with Disabilities in Russian Orphanages

Summary

The staff used to hit me and drag me by the hair. They gave me pills to calm me down.

– Nastia Y., a 19-year-old woman with a developmental disability, describing the treatment of staff in an orphanage for children with developmental disabilities in Pskov region, where she lived from 1998 to 2011

Every child with a disability in Russia has a significant chance of ending up in a state-run orphanage. Nearly 30 percent of all Russian children with disabilities live separately from their families and communities in closed institutions. These children have a range of impairments, including physical disabilities such as limited mobility, blindness, and deafness; developmental disabilities such as Down’s syndrome; and psychosocial disabilities such as depression, among others. Children with disabilities in state orphanages may be subject to serious abuses and neglect that severely impede their physical, emotional, and intellectual growth.

Children with disabilities may be overrepresented in institutional care. An international children’s rights nongovernmental organization (NGO) estimates that approximately 45 percent of children living in state institutions have some form of disability, despite the fact that children with disabilities account for only 2 to 5 percent of Russia’s total child population. The Russian government’s failure to ensure meaningful alternatives for these children means that many children with disabilities spend their childhoods within the walls of institutions, never enjoying a family home, attending school, or playing outside like other children.

This report is based on visits by Human Rights Watch researchers to 10 orphanages in 6 regions of Russia, as well as on more than 200 interviews with parents, children, and young people currently and formerly living in institutions in these regions in addition to 2 other regions of Russia. Children described how orphanage staff beat them, used physical restraints to tie them to furniture, or gave them powerful sedatives in efforts to control behavior that staff deemed undesirable. Staff also forcibly isolated children, denied them contact with their relatives, and sometimes forced them to undergo psychiatric hospitalization as punishment.

Many children also experienced poor nutrition and lack of medical care and rehabilitation, resulting in some cases in severely stunted growth and lack of normal physical development. Human Rights Watch determined that the combination of these practices can constitute inhuman and degrading treatment. Children with disabilities living in orphanages also had little or no access to education, recreation, and play.

Children with certain types of disabilities, typically those who cannot walk or talk, are confined to so-called “lying-down” rooms in separate wards, where staff force them to remain in cribs for almost their entire lives. Human Rights Watch documented particularly severe forms of neglect in “lying-down” rooms in the institutions it researched. The practice of keeping children with certain types of disabilities in such conditions is discriminatory, inhumane and degrading, and it should be abolished.

Research by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and others has demonstrated that institutionalization has serious consequences for children’s physical, cognitive, and emotional development, and that the violence children may experience in institutions can lead to severe developmental delays, various disabilities, irreversible psychological harm, and increased rates of suicide and criminal activity. UNICEF has urged governments throughout Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia to stop sending children under the age of 3, including children with disabilities, to institutions.

While Russia lacks comprehensive and clear statistics on children in state institutions or foster care, experts estimate that the overwhelming majority of these children have at least one living parent. Russia’s high rate of institutionalization of children with disabilities results from a lack of government and state-supported services, such as inclusive education, accessible rehabilitation, and other support that would make it feasible for children’s families to raise them. In addition, many parents face pressure from healthcare workers to relinquish children with disabilities to state care, including at birth. Human Rights Watch documented a number of cases in which medical staff claimed, falsely, that children with certain types of disabilities had no potential to develop intellectually or emotionally and would pose a burden with which parents will be unable to cope. In all of these cases, the children raised in their families had far exceeded any expectations.

Children with disabilities who enter institutions at a young age are unlikely to return to their birth families as a result of the practice of local-level state commissions to recommend continued institutionalization of children. The Russian government has failed to adequately support and facilitate adoption and fostering of children with disabilities, although these types of programs formally exist. As a result, when children with disabilities turn 18 and age out of orphanages, they are overwhelmingly placed in state institutions for adults with disabilities. Staff in many orphanages also fail to provide training and practical knowledge that would give children the skills they need to live independently once they become adults.

While in orphanages, children with disabilities may be subject to serious violence, neglect, and threats. For example, Human Rights Watch documented the use of sedatives to restrain children deemed to be too “active” in 8 out of the 10 institutions it visited in the course of researching this report. Twenty-five year-old Andrei M., a young man with a developmental disability who lived in an orphanage in Pskov region until 2008, told Human Rights Watch, “They constantly gave us injections, and then they sent us to the bedroom so that we would sleep.”

Human Rights Watch spoke with many orphanage staff who expressed a desire to support children’s maximal development and who worked hard to do so with the information and resources at their disposal. Some of these staff were also those who used practices such as physical and chemical restraints, for example. The findings below are presented with the understanding that well-intentioned staff often engage in unacceptable childrearing methods because they lack information, such as training in nonviolent disciplinary methods, as well as resources, such as additional personnel to help them care for large numbers of children.

Children with disabilities living in state institutions may also face various forms of neglect, including lack of access to adequate nutrition, health care and rehabilitation, play and recreation, attention from caregivers, and education. For example, Olga V., a pediatrician at a Sverdlovsk region orphanage for children with developmental disabilities, stated that not all children in the orphanage go to school, including 150 children in “lying-down” rooms who she claimed were “uneducable” (neobuchaemy) – an outdated diagnosis that state doctors and institution staff continue to assign to some children. In the same orphanage, another pediatrician stated that rather than select food appropriate for children’s ages and health needs, staff “grind up whatever we have and use tubes to feed the ones who can’t feed themselves.”

As a result of violence and neglect, children with disabilities in state institutions can be severely physically and cognitively underdeveloped for their ages. Nina B., an independent, Moscow-based pediatrician specializing in the health of children with disabilities, told Human Rights Watch that children from orphanages often become atrophied due to lack of stimulation, movement, and access to rehabilitation services.

Children with disabilities living in state institutions also face numerous obstacles to adoption and fostering, including lack of government mechanisms to actively locate foster and adoptive parents for children with disabilities; lack of support for adoptive and foster families of children with disabilities; and some state officials’ negative attitudes towards children with disabilities and their active attempts to dissuade parents from adopting or fostering these children on the basis that they will be unable to care for them.

The Russian federal government has in recent years developed several policies that include important measures to end institutionalization and provide better alternatives for children with disabilities and their families. For example, the government formulated the National Action Strategy in the Interests of Children for 2012-2017, which aims to create government support services that would enable children with disabilities to remain in their birth families, return children with disabilities who live in institutions to their birth families, and increase the number of Russian regions that do not use any form of institutional care for orphans. The government also established a foundation to finance projects by regional governments and NGOs in certain priority areas, including prevention of child abandonment and social inclusion of children with disabilities.

However, these well-intentioned policies lack clear federal plans for implementation and monitoring. As such, they fail to adequately address the widespread practice of institutionalization of children with disabilities and to create sufficient meaningful alternatives for children with disabilities and their families.

In May 2014 the Russian government also passed a resolution that establishes orphanages as temporary institutions whose primary purpose is to place children in families and mandates that orphanages protect children’s rights to health care, nutrition, and information about their rights, among other fundamental rights guaranteed under the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). While the resolution contains important protections for all children living in state institutions, Human Rights Watch is concerned that several of its articles may segregate children with disabilities living in state institutions from their peers without disabilities and that the resolution does not give sufficient attention to the needs of children with disabilities with regard to adoption, fostering, and access to information on their rights.

Russia has a robust civil society, including many groups that advocate on behalf of children with disabilities and provide services to both children in institutions and children with disabilities and their families outside of institutions. For example, several groups in Moscow and other Russian cities raise awareness about the human rights and dignity of people with disabilities, provide parents of newborns with disabilities with information on services available to these children in the community, and provide services such as support groups to parents of children with disabilities.

With regard to disability rights, the Russian government has taken steps to create more accessible infrastructure and community-based services for all persons with disabilities. For example, in May 2014 the Russian State Duma accepted in their first reading a set of amendments that include a prohibition against disability-based discrimination and an expanded list of changes to be made so that public facilities and services are accessible.

While these initiatives are important, Russia has a long way to go to enable children with disabilities to grow up in their communities and participate in community life. Most importantly, Human Rights Watch has found that children with disabilities and their families have felt the effects of the government measures to a very limited extent. Parents continue to give up their children to state care with little or no information about their children’s rights and developmental potential or about community-based services that are available to help them raise their children.

In order to ensure protection of the rights of children with disabilities in Russia and to comply with its international human rights obligations, the government should immediately adopt a zero tolerance policy for violence, ill-treatment, isolation, and neglect of children with disabilities living in state institutions and guarantee children’s rights to food, education, and play. In addition, the government should accelerate and expand initiatives to prevent healthcare workers from pressuring parents of children with disabilities to relinquish care to institutions. In cases where children are orphaned or living without parental care, the government should ensure that institutionalization is used only in the short term, in emergency situations, to prevent the separation of siblings, and when necessary and constructive for the child and in his or her best interest.

In the long term, Russia should take concrete steps to end the institutionalization of children, especially infants separated from their parents, with extremely limited exceptions, as described above.

Until the government acts, it will needlessly continue to consign these children to lifetimes within four walls, isolated from their families and communities, and robbed of the opportunities available to other children.

Key Recommendations

To the Russian Government, including the Ministries of Labor and Social Protection, Health, and Education

Immediately

- Establish a zero tolerance policy for state children’s institution staff who beat, humiliate, or insult children.

- End the use of physical restraints, sedatives, forced isolation, and forced psychiatric treatment as means of managing or disciplining children in care.

- Abolish the practice of confining children with certain types of disabilities to “lying-down” rooms.

- Ensure that parents and children are able to contact and visit with one another at will, with no adverse consequences to children’s well-being.

- Guarantee children with disabilities living in state institutions access to inclusive education, adequate nutrition and water, health care, rehabilitation, and play.

- Establish robust monitoring mechanisms and systems of redress accessible to children with disabilities.

- Ensure institutionalization is used only in the short term, in emergency situations, to prevent the separation of siblings, when necessary and constructive for the child, and in his or her best interest, including by:

- Providing information to expectant parents and healthcare workers who serve new parents on the rights and dignity of children with disabilities;

- Providing parents of children with disabilities telephone numbers and addresses of community-based support services such as early education programs for children with disabilities.

Medium to Long-Term

- Establish a time-bound plan to end the institutionalization of children, especially infants separated from their parents, with extremely limited exceptions. This plan should:

- Ensure that state financing for formal care of children with disabilities privileges family-based care options;

- Include measures to return children with disabilities to their birth families and ensure that families have adequate support to care for these children;

- Include measures to actively encourage adoption and fostering of children with disabilities.

- Fully realize efforts to make Russian communities accessible and inclusive to all persons with disabilities, including children with disabilities.

To Russia’s International Partners, Including the European Union and its Member States, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Bank and Other International Financial Institutions, and All Donors – Governmental and Nongovernmental – Engaged in Assistance Programs with Russia in the Context of Multilateral and Bilateral Funding

- Earmark financial and other forms of support and assistance toward support services for families of young children with disabilities and prevention of child abandonment, as well as toward family reunification and other forms of family-based care for children with disabilities separated from their biological families.

Methodology

The field research for this report was conducted between November 2012 and December 2013 across eight regions of Russia (city of Moscow, Moscow region, city of St. Petersburg, Leningrad region, Sverdlovsk region, Buryatia, Karelia, and Pskov region).

These regions were selected because of their diversity. In St. Petersburg and Leningrad region, we were interested in measures city and regional governments had taken to increase access to education for children with disabilities in institutions. We chose Sverdlovsk region, Buryatia, Karelia, the city of Moscow, Moscow region, and Pskov region because of various innovative measures that nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in several cities in these regions are taking to support accessibility for people – including children with disabilities – to education and health care and to support foster care and adoption of children with disabilities. To protect the security of several institution staff, volunteers, children, and activists, this report refers to some interviews as having taken place in northwest Russia.

This report is based on 213 interviews, both in Russia and by phone before and after field research, including with 48 children and young people with disabilities who currently live in or have lived in state institutions within the past 10 years. Human Rights Watch also interviewed 48 parents and family members of children with disabilities, including foster and adoptive parents.

Twenty-five interviewees were children ages 5 to 17, and 23 were young adults ages 18 to 28. The term “children and young people with disabilities” includes those with developmental disabilities such as Down’s syndrome; psychosocial disabilities such as depression; sensory disabilities (including blindness, low vision, deafness, and hardness of hearing); and limited mobility. Some children and young people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed had multiple disabilities.

Human Rights Watch visited 10 state institutions where children with disabilities live, housing up to 400 children. These institutions included 3 specialized infant care institutions (“baby houses”) for children with disabilities from newborn to age 4 and 7 children’s homes for children between ages 4 to 17. Six of the children’s homes were specialized homes for children with disabilities and one children’s home included children with and without disabilities. In addition, we visited two institutions for adults with disabilities (in Russian, psychoneurological internats or PNIs) in Moscow region and in northwest Russia.

During our institutional visits and in other settings, we interviewed 39 current or former staff members (directors and vice-directors and medical and other staff) of state children’s institutions, including 3 former directors of children’s homes. Additionally, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with three Russian doctors who specialize in the health of children with disabilities, including children residing in institutions. We also spoke with two regional government officials: Yuri Kuznitsov, advisor to the chairmanof the St. Petersburg Committeeon Social Policy, and Tatiana Merzliakova, Sverdlovsk region human rights ombudsperson.

Human Rights Watch spoke also with 39 activists with local and international children’s and disability rights NGOs with offices in Russia. Human Rights Watch researchers also consulted international disability rights experts at various stages of the research.

Whenever possible, Human Rights Watch spoke directly with children and young people with disabilities. In all regions but Pskov and northwest Russia as a whole, researchers faced difficulties speaking with children living in institutions in conditions that would not place them at risk of possible retaliation by orphanage staff. For this reason, the majority of direct testimony from children and young people with disabilities comes from these regions.

We interviewed children and young people with disabilities on a variety of topics, including their treatment by staff in institutions; their access to education, adequate nutrition, and health care and rehabilitation in institutions; their access to recreation; and their contact with family members, among other issues. We also interviewed children and young people with disabilities about their experiences accessing education, health care, and rehabilitation in their communities.

This report notes children’s ages at the time when events they reported occurred whenever possible. However, many children and young people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed who had spent years living in institutions were unable to recall their ages or the years and months in which events occurred. These children and young people did not attend school regularly, spent most of their time indoors with little or no access to the Internet or print media, did not celebrate their birthdays, and had few other ways to recall dates or their ages when events in their lives occurred. Sometimes they referenced events by the day of the week they occurred because many children ate the same meal on a given day of the week for years. It was therefore not uncommon for a child to make a statement that a violent event “happened on a Sunday, because we had potatoes,” for example.

With activists, parents, doctors, journalists, and institution staff, we discussed these topics as well as pressure that parents have experienced to relinquish care of their children to institutions. We also discussed mechanisms for the placement of children in foster or adoptive families and mechanisms for the return of children to their birth families. Nearly all interviews were facilitated by local NGOs, disabled persons organizations (DPOs), or children’s and disability rights advocates.

All interviews were conducted in Russian or English. For each person interviewed, we explained our work in age-appropriate terms. Before each interview, we informed potential participants of the purpose of the research and asked whether they wanted to participate. We informed participants that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific questions without consequence.

Human Rights Watch took great care to interview people in a sensitive manner and ensured that the interviews took place in a location where the interviewees’ privacy was protected. Most persons over age 18 in the report are identified by pseudonyms in order to protect their privacy and confidentiality, unless they requested to be identified by their real names. Human Rights Watch has used pseudonyms for all children interviewed for this report as well as their parents, except where indicated.

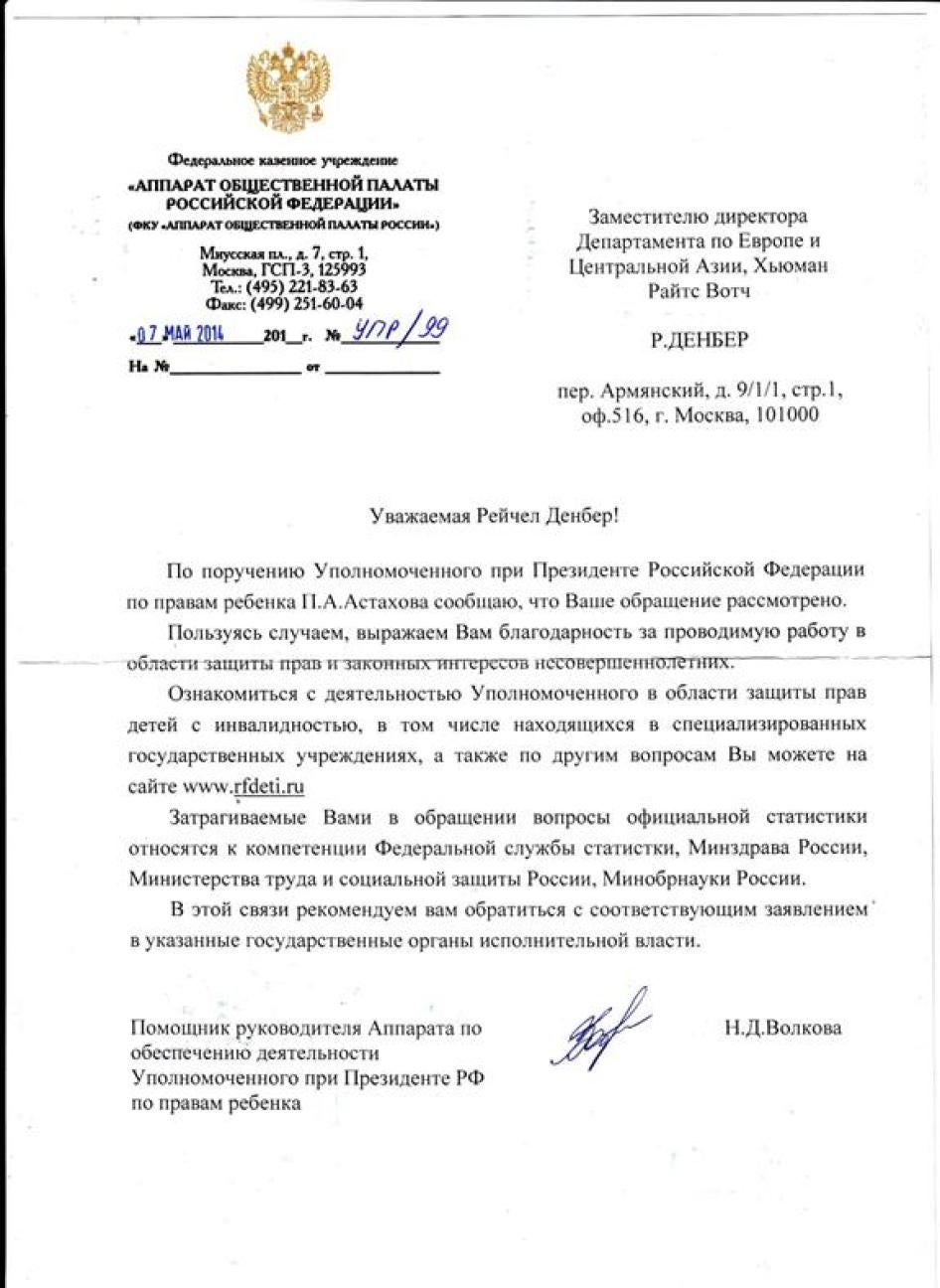

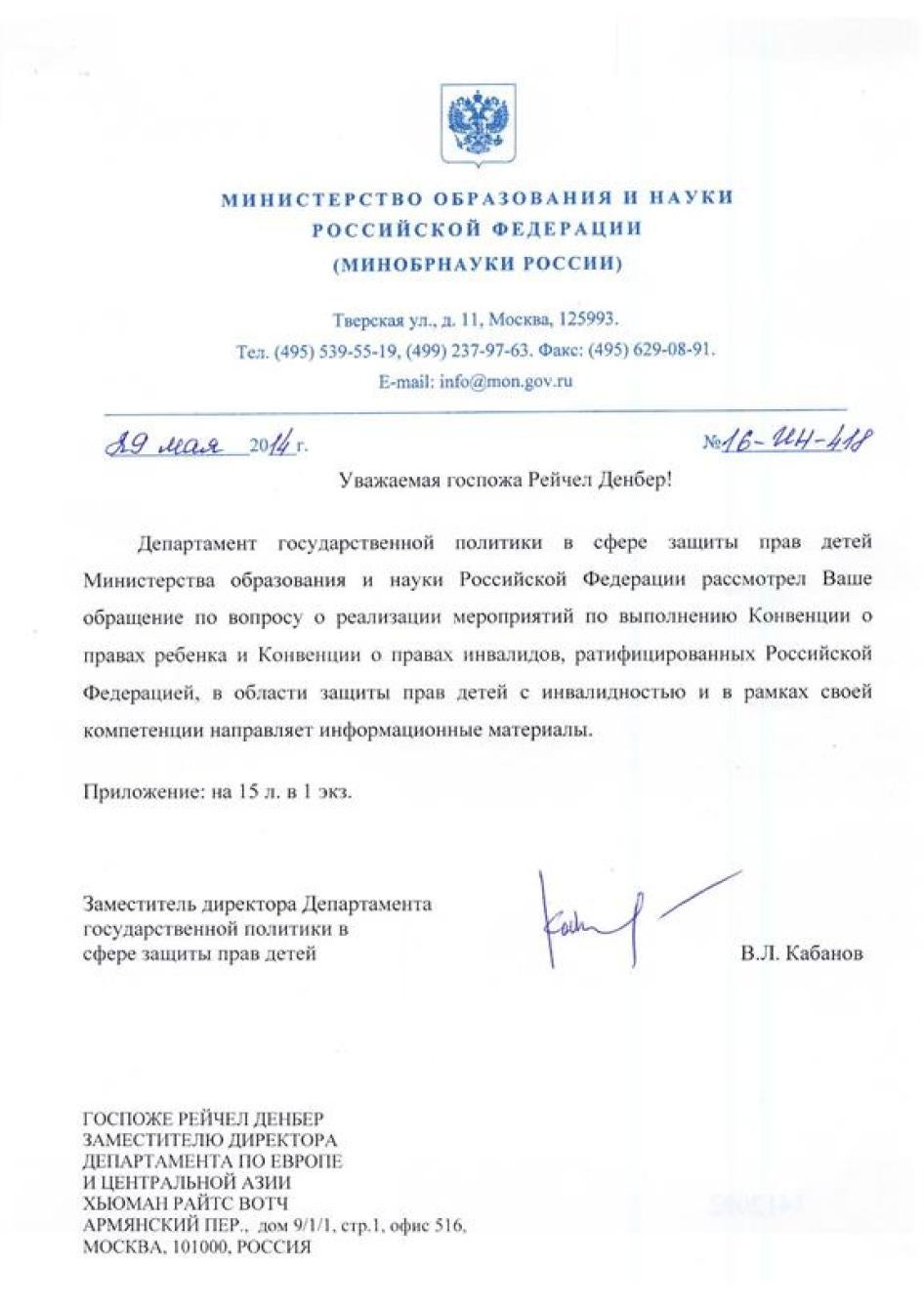

Human Rights Watch sent letters to the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection, the Ministry of Education, and to Pavel Alekseevich Astakhov, children’s rights commissioner of the Russian Federation, with questions regarding the findings of this report; seeking recent statistics on the number of children with disabilities in Russian state institutions; and requesting information on the government’s handling of complaints by or on behalf of children with disabilities regarding abuses in state institutions. We received a response from each of the abovementioned ministries and offices.[10]

As part of this research, we also reviewed a number of Russian government policies and laws and relevant reports from United Nations agencies and NGOs.

Key Terms

Baby houses (doma rebyonka): State residential institutions for orphans and children without parental care, age 4 and under.

Cerebral palsy : An impairment of muscular function and weakness of the limbs. Often accompanied by poor motor skills, it sometimes involves speech and learning difficulties. [1]

Children’s homes (detskie doma): State residential institutions for orphans and children without parental care, ages 4 to 18.

Child without parental care : A child under the age of 18 living without the care of a parent. [2]

Developmental disability : An umbrella term that refers to any disability starting before the age of 22 and continuing indefinitely (i.e., that will likely be life-long). [3] It limits one or more major life activities such as self-care, language, learning, mobility, self-direction, independent living, or economic self-sufficiency. [4] While this includes intellectual disabilities such as Down’s syndrome, it also includes conditions that do not necessarily have a cognitive impairment component, such as cerebral palsy, autism, and epilepsy and other seizure disorders. Some developmental disabilities are purely physical, such as sensory impairments or congenital physical disabilities. A developmental disability may also be the result of multiple disabilities. While autism is often conflated with learning disabilities, it is actually a developmental disability.

Disabled persons organizations (DPOs ): These are formal groups of people who are living with disabilities and who work to promote self-representation, participation, equality, and integration of all people with disabilities.

Down’s syndrome : A condition in which a person is born with an extra copy of

chromosome 21. People with Down’s syndrome can have hearing problems and problems with the intestines, eyes, thyroid, and skeleton, as well as intellectual disabilities. [5]

Guardianship and custody agencies (organy opeki i popechitelstva): Local-level committees of teachers, psychologists, lawyers, social workers, and civil servants responsible for monitoring conditions in all state children’s institutions on a regular basis, as well as for selecting and training people wishing to become guardians of children, among other responsibilities.

Institutional caretakers :A range of staff employed by Russian state institutions for children with disabilities, including pediatricians, nurses, psychologists, and speech therapists, as well as caregivers called vospitatels and sanitarkas. [6] For clarity, this report refers to all sanitarkas and vospitatels as institution staff.

Learning disability : A condition affecting the brain’s ability to receive, process, retain, respond to, and communicate information. [7]

Orphan : A child under the age of 18 whose parents are no longer alive. [8]

Psychologo-Medical-Pedagogical Commission (PMPC) (pskhikologo-mediko-pedagogicheskaia komissia): A city-level commission consisting of state psychologists, physicians, and education specialists that evaluates children and formulates a plan for a child’s upbringing. The commission evaluates every child living in an infant care institution at age 3 or 4 and recommends the child’s continued residence in a state institution.

Psychoneurological internats for adults (PNI) (pskhikonevrologicheskie internaty): State residential institutions for adults with various disabilities age 18 and above and for elderly people considered by the government to be unable to care for themselves.

Psychosocial disability : The preferred term to describe persons with mental health problems such as depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Psychosocial disability relates to the interaction between psychological differences and social/cultural limits for behavior, as well as the stigma that society attaches to persons with mental impairments. [9]

Specialized state children’s institutions : State residential institutions housing up to 400 children of various ages (see “baby houses” and “children’s homes” above) whom the government designates as having disabilities or health conditions that require specialized medical and rehabilitation services. These include specialized baby houses and children’s homes. Placement of a child in such an institution with the purpose of his or her indefinite residence there is referred to as “institutionalization.”

I. Background

High Rates of Institutionalization

The Russian government lacks age- and disability- disaggregated statistics on children with disabilities in Russia and whether they live in family-based or institutional care. An international children’s rights nongovernmental organization (NGO), whose work includes advocating for community-based support for children with disabilities, estimates that approximately 45 percent of children living in state institutions have some form of disability. They base this figure on United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and Russian government data and their own observations and consultations with NGO colleagues.[11] The NGO also estimates that approximately 30 percent of all Russian children with disabilities live in state institutions, despite the fact that children with disabilities account for approximately 2 to 5 percent of Russia’s total child population.[12]

According to a 2010 UNICEF report surveying 21 countries in Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, Russia accounted for half of all children under the age of 3 living in institutions in the region and has the fourth highest rate of children under the age of 3 in the region.[13] A 2012 report by an international children’s advocacy organization states that of 10 countries surveyed around the world, Russia has the highest rate of children living in institutional care, although it also has the lowest poverty rate of the countries surveyed.[14]

Russia’s System of Segregation

The Russian system of state children’s institutions includes mainstream institutions for children without disabilities (hereafter referred to as “mainstream institutions”) as well as institutions for children with disabilities.

Infant Care Institutions

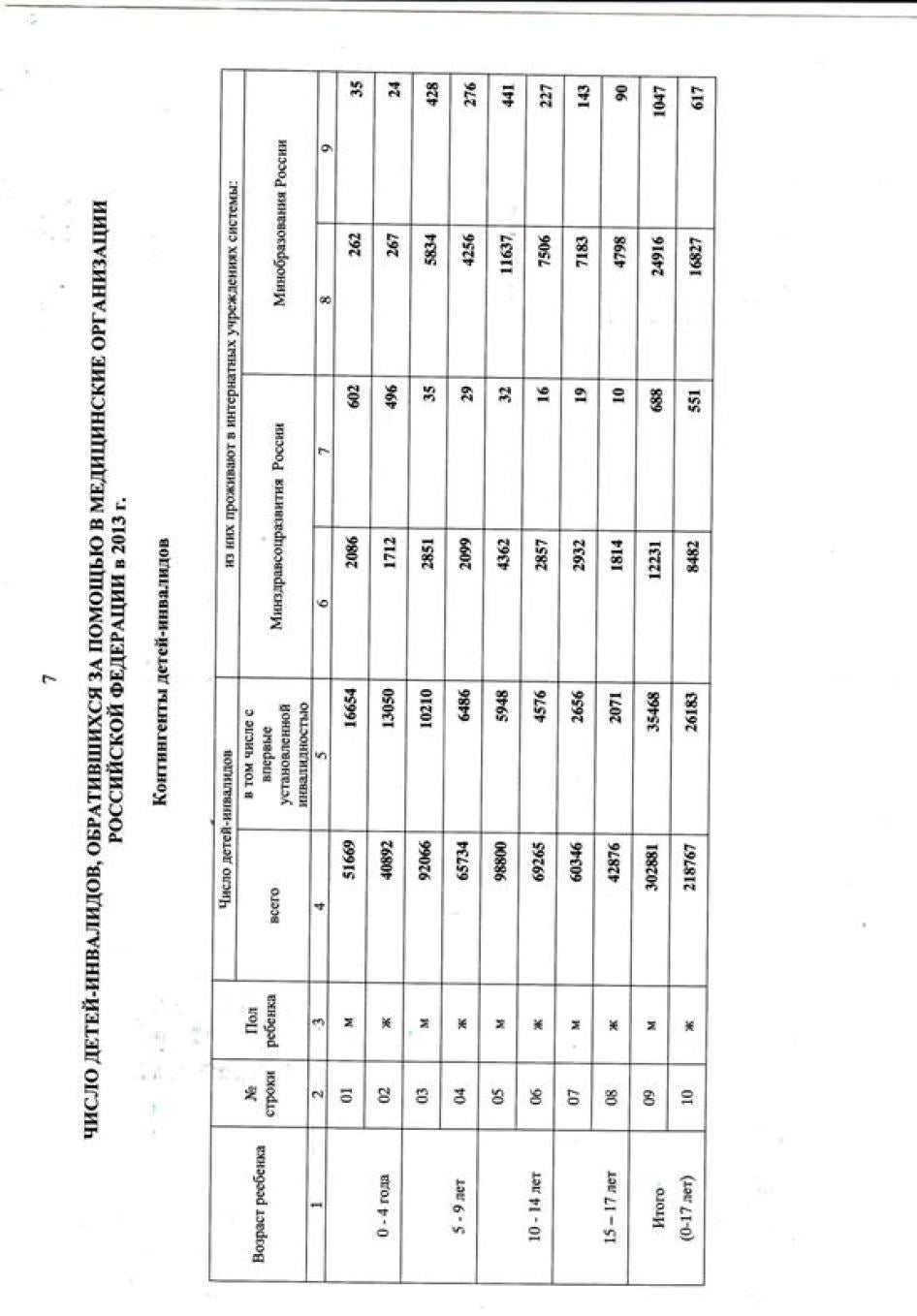

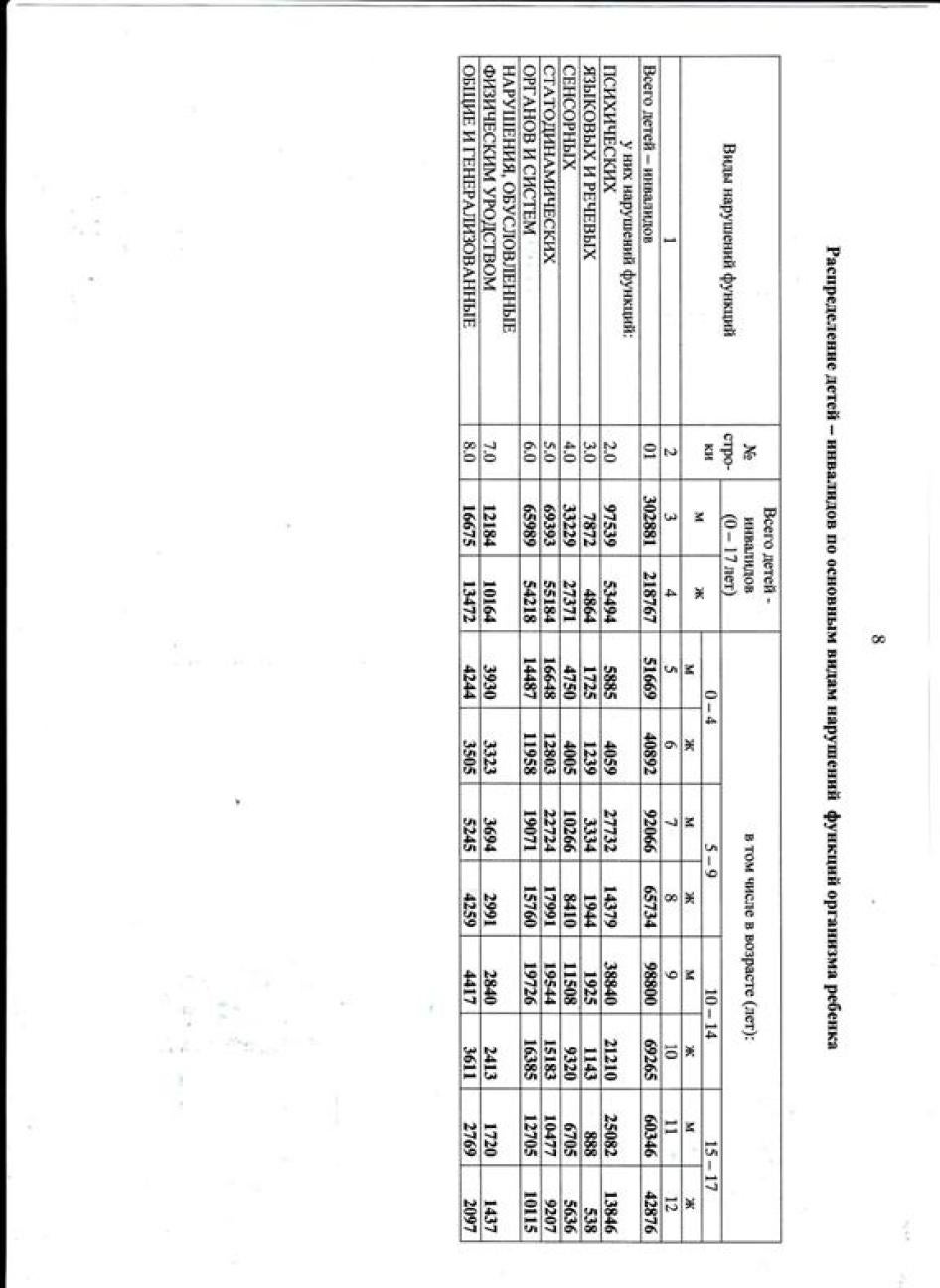

Many children enter the state institution system directly after birth, when health workers transport them from birthing hospitals to infant care institutions, or “baby houses.” Russia has 194 infant care institutions in which 13,977 children live. Approximately 26 percent of Russia’s “baby house” residents are children with disabilities. [15] The government designates some “baby houses” as “specialized” or “correctional baby houses” (hereafter referred to as “specialized infant care institutions”). Specialized infant care institutions may include children with various disabilities or children with particular kinds of disabilities.

Institutions for School-Age Children

When children in infant care institutions reach the age of 3 or 4, they appear before a regional commission called the Psychologo-Medical-Pedagogical Commission (PMPC), consisting of a variety of health and educational professionals. The commission’s official role is to medically and psychologically examine children, identify developmental delays, and formulate a structured plan for a child’s further education and upbringing.[16] If the PMPC believes that the child is unable to live in a family, the commission designates the type of institutions in which a child can be placed. In the vast majority of cases, the commissions send children with disabilities to specialized “children’s homes,” sometimes referred to as “internats,” overseen by the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection.[17] Activists familiar with different types of institutions report that conditions in mainstream children’s homes, which are supervised by the Ministry of Education, are generally better than those in the specialized state institutions and that children have more opportunities for education in mainstream children’s homes.[18]

The Ministry of Education also oversees boarding schools for children with disabilities (shkoly-internaty), which are usually specialized by type of disability. Many children live in these schools because their communities lack inclusive education or specialized schools with more specific accommodations for children with disabilities that children and their parents may seek.[19]

Alternatively, children at different ages, both with and without disabilities, may be placed in temporary institutions either because their parents are unable to care for them for a period of time or because local-level state agencies that organize the placement of children without parental care have yet to establish more permanent alternative care for children.[20]

Consequences of Institutionalization and Better Alternatives

UNICEF and others have documented how high rates of institutionalization hold serious consequences for children’s physical, cognitive, and emotional development. Institutional care for children is often characterized by large groups homogeneous in age and disability; overcrowding; unstable caregiver relationships; lack of specialist training in social interactional factors; lack of caregiver responsiveness; sleep, eating, and hygiene routines not tailored to children’s needs; and sometimes, insufficient material resources.[21] UNICEF has urged governments throughout Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia to stop sending children under the age of 3, including children with disabilities, to institutions.[22]

Psychologists and other child development specialists widely agree that life in institutions contributes to physical underdevelopment, deteriorated brain growth, below average IQs and intellectual development, and reduced social abilities, such as difficulties forming stable relationships with others, including later in life.[23]

Institutional care for children is also often characterized by physical, psychological, and sexual violence by staff and other children.[24] Violence that children may experience in institutions is often long-term and can lead to severe developmental delays, various disabilities, irreversible psychological harm, and increased rates of suicide and criminal activity.[25]

Children who enter institutional care under the age of 3 face particularly severe consequences. Birth to age 3 is the most important developmental phase in life with lasting and sometimes irreversible impacts on children’s physical, cognitive, and emotional development. UNICEF research on young children adopted from institutions in Eastern Europe has documented deficiencies in physical and brain growth, cognitive problems, speech delays, inattention, difficulties forming attachments, and hyperactivity.[26] The deprivation of stable caregiver relationships for young institutionalized children can cause severe damage and has been equated with violence.[27]

Children who are moved from institutional care into adoptive or foster families before the age of 6 months can still reach optimal physical and psychological development, which is characterized by the ability to express oneself and to form close relationships later in life, among other markers of development.[28] Children of all ages transferred from institutions to foster care experience marked gains in cognitive functioning, with younger children experiencing better outcomes.[29]

II. Physical and Psychological Violence in

Russian Institutions

Human Rights Watch documented conditions in 10 state institutions devoted to the care of disabled children in Russia. Through interviews with children and young people with disabilities, institution staff, and activists, as well as visits to the institutions, researchers found a range of abuses against children in 8 of these institutions. Most of the cases of abuse appeared to involve staff using abusive measures to control children’s behaviors or punish children, including for behaviors which were directly related to their disabilities. These abuses include: physical violence in the form of beatings or pouring cold water over children’s heads; the use of physical restraints, including binding children to cribs or wheelchairs; the frequent use of sedatives to control or punish children; and forced psychiatric hospitalization as punishment. Human Rights Watch also documented psychological violence in the form of forced isolation; denial of contact with family members; threats of death, beatings, or psychiatric hospitalization; insults; humiliation; and lack of attention from caregivers. Each of the 23 children living in institutions at the time Human Rights Watch interviewed them described at least one, and usually many more, incidents of abuse against them by institution staff or by other children while institution staff did not intervene.

None of the children or young people interviewed by Human Rights Watch had recourse to systems through which they could safely report violence without fear of retaliation.

Human Rights Watch has determined that the ill-treatment of some children in institutions as documented in this report may rise to the level of torture, particularly given the combination of different types of physical and psychological violence used against children, use of physical and chemical restraints, and psychiatric hospitalization. Other forms of violence against children that may contribute to treatment rising to the level of torture include forced isolation from parents and families, as well as malnutrition and neglect.

Human Rights Watch spoke with many orphanage staff who expressed a desire to support children’s maximal development and who worked hard to do so with the information and resources at their disposal. Some of these staff were also those who used practices such as physical and chemical restraints, for example. The findings below are presented with the understanding that well-intentioned staff often engage in unacceptable childrearing methods because they lack information, such as training in nonviolent disciplinary methods, as well as resources, such as additional personnel to help them care for large numbers of children. Human Rights Watch therefore urges the Russian government to ensure that staff receive all appropriate support to care for children in a way that respects their rights and dignity, as indicated in the recommendations below.

Russia has obligations under national and international law to protect children with disabilities living in Russian state institutions from all forms of violence. Russian national law prohibits torture and inhuman and degrading treatment and guarantees all citizens in state care the right to humane treatment. [30]

As a party to the Convention against Torture, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Russia is obligated to protect children with disabilities from all forms of violence and from torture or inhuman or degrading treatment. [31] The CRC states that children should be protected from “all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, [and] maltreatment or exploitation….” [32] The European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly held governments responsible for failure to protect children from violence and neglect, whether in a domestic situation or in state care. [33]

Under these treaties, Russia must also ensure effective monitoring and mechanisms for reporting abuse. However, the Russian government lacks federally enforced monitoring mechanisms to ensure children’s enjoyment of their basic human rights while living in institutions.

Physical Violence

Children and young adults with disabilities whom Human Rights Watch interviewed reported suffering various forms of violence while living in specialized state institutions or witnessing violence inflicted on other children with disabilities by staff or peers. Interviewees reported beatings by staff and older children with disabilities and other attempts to inflict pain or discomfort, such as pouring cold water on children with disabilities.

Several activists and institution volunteers from St. Petersburg, Leningrad region, Karelia, and Nizhny Novgorod region whom Human Rights Watch interviewed stated that physical abuse in state institutions that they had visited is common. They based these assessments on frequent visits in which they either witnessed beatings firsthand or observed physical and psychological signs of violence in their interactions with children.[34] For example, a children’s rights activist who runs a volunteer program in a specialized infant care institution in Nizhny Novgorod region reported multiple cases between 2010 and 2013 in which children demonstrated beatings by institution staff using dolls. When the activist asked the institution director to investigate, the latter stated that she would not investigate the violence on the basis that the staff member in question had herself been raised in a state institution and was therefore expected to treat others harshly.[35] In 2013 Margarita M., a volunteer at a state children’s institution in northwest Russia, reported witnessing an institution staff member kick in the head a 10-year-old girl who had been crying. Margarita M. reported the incident to the head nurse who she alleges replied, “We need to wait for the next event to occur [before taking further action].” Margarita M. told Human Rights Watch, “I don’t know where to take complaints about how these children are treated.”[36]

Nineteen-year-old Nastia Y., a young woman with a developmental disability, lived in a Pskov region specialized state institution from 1998 to 2011. Nastia Y. told Human Rights Watch that she experienced beatings by institution staff on several occasions, including by institution staff who were drunk:

The staff used to hit me and drag me by the hair. They gave me pills to calm me down. They hit me when they came to work and found me roughhousing with the other kids…. When they got drunk, they would hit the other children and me often. I remember one incident, when a staff member was drunk. She asked me where the key to her office was. When I told her I did not know, she dragged me into a room and beat me up.[37]

According to Nastia Y., she was beaten repeatedly while at the institution. The last time she was beaten there was in 2011 shortly before she left when she refused to sign a contract agreeing to be transferred to an adult institution.[38] Anton K., a 21-year-old man with a physical disability who lived in a specialized state children’s institution in northwest Russia from 2000 until 2011, described a violent incident he witnessed in the institution in 2006, when a staff member punished a boy with a physical disability in Anton K.’s group of children:

One day, I saw a doctor beat a boy badly. Then they tied his hands together with a belt and held his head under water in the bathtub. Since then, whenever I saw doctors, I was quiet. I tried not to be noticed.[39]

Nastia Y., whose case is described above, reported that other girls in the orphanage where she lived used to hit and kick her in the presence of institution staff members, who did not intervene.[40]

Aside from beatings, children reported experiencing or witnessing other forms of physical violence. For example, Anton K., mentioned above, told Human Rights Watch that he repeatedly witnessed institution staff punishing children by pouring cold water on them when they cried.[41]

Each of the children and young people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed reported that they knew of no procedure for reporting violence.[42] In several cases, institution staff also explicitly threatened them to prevent them from telling anyone about the violence.[43] Institution staff or volunteers may be reluctant to report abuse due to lack of knowledge on how to do so, fear of retaliation, or fear of being implicated in the abuse.[44]

Use of Restraints

Human Rights Watch documented how staff in many institutions frequently used physical restraints on children, including tying children’s arms, heads, or torsos, often with rags or scraps of cloth, to cribs or wheelchairs, as well as confining children to cribs. Human Rights Watch researchers witnessed the use of each of these forms of restraints in 8 of the 10 institutions that they visited.[45] Activists, orphanage volunteers, and some institution staff reported that the use of these forms of restraints is a common practice in specialized “children’s homes.”[46] Institution staff stated that they tied children to prevent certain types of behavior, such as clawing at their eyes, knocking their heads against cribs or walls, jumping out of their cribs and injuring themselves, or attempting to escape their rooms or the institutions where they lived. Staff did not use alternative approaches to help children with these behaviors refrain from hurting themselves and others or from disrupting institution routines.

The United Nations special rapporteur on torture’s 2013 report on abuses in healthcare settings states that any restraint on people with mental disabilities, including seclusion, even for a short period of time, may constitute torture and ill-treatment.[47]

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has stated that all persons working with children in care institutions should be trained in nonviolent disciplinary and childrearing methods.[48]

Binding

Human Rights Watch observed children who had their heads, arms, or torsos bound by rags or clothing to cribs or other furniture such as wheelchairs in eight of the 10 institutions that researchers visited. In northwest Russia, children’s rights activist Yana D., mentioned above, described her observations while working in three specialized children’s institutions in northwest Russia between 2006 and 2009. Yana D. reported having witnessed children tied to cribs in all three institutions. In cases when institution staff did not bind children to cribs, according to Yana D., they gave children sedatives to prevent them from knocking their heads against the crib railings.[49]

In April 2013 a 7-year-old boy with a developmental disability died after a health worker in a Nizhny Novgorod region specialized state children’s institution used cloth diapers to tie him to his bed. A preliminary account stated that the boy may have choked on his own vomit and that being tied down stopped him from rolling over to breathe.[50] Children’s Rights Commissioner Pavel Astakhov urged the government to investigate the death and called for Russia to ban the practice of tying children up, noting that other children have died in similar circumstances.[51] Astakhov did not comment on the widespread nature of the use of restraints in Russian state children’s institutions and the ways in which the practice denies children even the most basic conditions to grow and develop.

A pediatrician at a specialized state children’s institution in Sverdlovsk region for children with developmental disabilities told Human Rights Watch that personnel tie some children to their beds as a “pedagogical technique” to prevent “self-aggression” or banging one’s head against the wall or crib railings.[52] When Human Rights Watch toured the Sverdlovsk region children’s home described above, a researcher observed eight children bound to the railings of their cribs, to wheelchairs, or with their hands bound to their torsos using rags.

Confinement to Cribs

Human Rights Watch research found that in 8t of the 10 institutions that researchers visited, all of them specialized state children’s institutions, staff confined many children of all ages to cribs all day, seven days per week, in so-called “lying-down” rooms. Rooms typically had 4 to 15 cribs. Staff provided these children with minimal time outdoors and did not give children opportunities to get up and walk or move around in wheelchairs. Staff working in the institutions that Human Rights Watch visited reported a variety of diagnoses for children confined to cribs, including cerebral palsy, schizophrenia, Down’s syndrome, and the Russian diagnoses of “debility” (debilnost), “imbecility” (imbesilnost), and “idiocy” (idiotia).[53] Staff justified keeping children confined to cribs stating that children were contagious (including in cases when children had non-communicable diseases such as schizophrenia); that children did not understand anything and therefore could not benefit from going outside or to classes, when the latter opportunities were available; or that the children’s health was too fragile to remove them from their beds.[54]

For example, in a Pskov region specialized state institution for children with various disabilities, Human Rights Watch visited several “lying-down” rooms. Some of the cribs were fortified with wooden planks bound to their sides, which reached taller than the crib railings. The director of the institution explained that the walls were put up “to keep children from jumping out of their beds.” However, the director also claimed that the children were confined to the beds because their health was too fragile to participate in the routines of the institution and that they needed to rest.[55]

Case Studies: Developmental Consequences of Physical Restraints

In Moscow and northwest Russia, Human Rights Watch documented three cases in which children who had learned to walk, or who may have been able to walk given their ages and lack of physical disabilities, were prevented from doing so because staff used restraints such as rags to bind them to crib railings or wheelchairs or confined them to cribs indefinitely.

In a Moscow specialized infant care institution, one staff member told Human Rights Watch that she had bound a 4-year-old blind girl to a wheelchair using rags tied around the girl’s head and torso, despite the fact that the girl could walk. The staff member justified the binding, stating, “She’s blind and she was hitting her head on the edges of furniture.”[56]

Similarly, in a specialized state children’s institution in northwest Russia, a Human Rights Watch researcher saw a 14-year-old girl named Lyuda who staff stated had cerebral palsy tied by the arms and torso to a wheelchair. A volunteer stated, “Lyuda used to be able to walk, but we tied her to a wheelchair to prevent her from running away. We didn’t want her to get beaten up by the staff [as punishment]. But now she has forgotten how to walk.”[57]

Human Rights Watch interviewed Valentina P., the former vice-director of a specialized state institution in Moscow region who had worked at the home from 2006 to 2008. Valentina P. reported that when she began working there staff bound many children indefinitely to cribs and furniture, including even 10- to 15- year-olds whose diagnoses with developmental disabilities would not have prevented them from learning how to walk. These children were not able to walk when Valentina P. first assumed her post. Other children had been perpetually confined to their beds and were unable to walk. According to Valentina P., about a year after she hired new and more staff and established a plan to engage the children daily, most of these children learned to walk.[58]

Chemical Restraints (Sedatives)

The vast majority of current or former specialized children’s institution residents whom Human Rights Watch interviewed reported that they had been given sedatives or that they had witnessed other children being given sedatives. Some institution staff also reported regularly and frequently administering sedatives to children, typically to control or punish them, and several activists confirmed that this is the case. Human Rights Watch is concerned that the regular and frequent use of sedatives on children, often apparently in order to control certain behaviors, may suggest that sedatives are being overused and may not always be used for their specified therapeutic purposes.

Human Rights Watch spoke with eight current institution staff in five institutions who confirmed the regular and frequent use of sedatives in the institutions where they worked.[59] Personnel typically stated that they gave sedatives to prevent children from banging their heads against crib railings or walls or to prevent children from disrupting institution routines.[60] Olga V., the head doctor in a Sverdlovsk region specialized state institution for children with developmental disabilities, reported, “At least 100 children here receive strong sedatives: five types, three times per day. If the children are not manageable, then we use medication.”[61]

Valia T., a 15-year-old girl with a physical disability residing in a northwest Russia specialized state institution, told Human Rights Watch, “Some children get pills every day, and it hurts me to see this, because the medications make them just want to sleep.” Valia T. told Human Rights Watch that she believed staff found these other children to be too “active” because they were the ones who sometimes tried to leave the room in which they were confined all day.[62]

Staff most commonly gave children whom Human Rights Watch interviewed or who lived in institutions Human Rights Watch visited a drug called Aminazin, though children did not always know what types of drugs they or other children were given. Aminazin, a brand name of chlorpromazine, is an antipsychotic drug used to treat schizophrenia, sleep disorders, and strong pain.[63] In the cases that Human Rights Watch documented, Aminazin was either injected or delivered orally.[64] The known side effects of Aminazin are significant and include: drowsiness, fatigue, depression, helplessness, indifference, lack of motor control, and incessant tremors. There is also a risk of liver damage.[65] Use of Aminazin for anything other than diagnostic and treatment purposes in accordance with the nature of a disorder is a violation of Russian federal law.[66]

Both children and institution staff reported the effects of Aminazin on children whom they observed being injected with it or on themselves: drowsiness, extreme fatigue (including resulting in sleep for more than 24 hours), and loss of appetite. For example, 25-year-old Andrei M., a man with a developmental disability, lived in a Pskov region specialized state institution from age 10 to 20 where staff regularly injected him and other children with Aminazin. He told Human Rights Watch,

They constantly gave us injections, and then they sent us to the bedroom so that we would sleep. There were no evening caretakers. So they gave us Aminazin to get us to sleep. Children became drowsy, and the next day they did not eat.[67]

Human Rights Watch spoke with children’s and disability rights activists with experience working in specialized orphanages in four regions who did not know whether children received sedatives according to their diagnoses, ages, and weights, or and whether orphanage staff monitored children who received sedatives. [68] Human Rights Watch therefore believes that the burden lies on the Ministry of Health, in conjunction with the other ministries responsible for running orphanages where children with disabilities live, to lead a comprehensive audit of all such institutions in order to ensure that sedatives are used only when they have a therapeutic effect on children.

Forced Psychiatric Hospitalization as Punishment

Several young people with disabilities who lived or previously lived in specialized state children’s institutions reported that staff of specialized state children’s homes forcibly sent them to psychiatric hospitals as a form of punishment for “bad” behavior or for being too “active”: for running indoors, roughhousing with other children, or trying to leave their rooms or go outdoors, for example.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 19-year-old Nastia Y., a young woman with a developmental disability who grew up in a specialized state institution in Pskov region. She described how staff gave her medication or took her to a local psychiatric hospital named Bogdanova, as punishment:

If you misbehave, then they give you pills to put you to sleep or they take you to Bogdanova. Bogdanova is a psychiatric hospital where there are bars on the windows. Staff there tie kids’ hands together and give them pills and injections…. I felt very badly when I was there.[69]

Nastia Y. could not recall the year when she was hospitalized. Several other young people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed in Pskov region also reported having seen other children in the institution being punished in this way. [70]

Pavel R., a young man with a physical disability who spent his childhood in a specialized state institution in northwest Russia, said that he had been sent to a psychiatric hospital as punishment for being too “active.” He told Human Rights Watch that it was painful to describe his treatment there. “It’s something I never want to talk about,” he said. [71]

Pavel R. also described an incident in 2006 when institution staff sent a 15-year-old boy named Nikita to the psychiatric hospital for running around the bedroom that he shared with 12 other boys. Pavel R. said, “He returned drowsy, and he slept for days.” [72]

Valia T., a 15-year-old girl with a disability who was living in specialized state institution in northwest Russia during the time of her interview with Human Rights Watch in 2013, said,

On a Sunday, a boy ran away from the children’s home. They put him in a psychiatric hospital. He’s been there for five months. When children return from the hospital, they are quiet. Their bodies tremble.[73]

Valia T. feared exactly this type of punishment for speaking about what she had witnessed. “Don’t tell anyone that I told you this,” she said. “They’ll put me away in a crazy house. They’ll kill me.”[74]

Use of Isolation When Transferring to New Institutions or as Punishment

Human Rights Watch documented how staff in many institutions routinely put children in isolation when they arrive or reenter an institution, when they are transferred from other institutions, or following visits with relatives.

When children move from one institution to another, medical personnel at the receiving institution typically require children to spend anywhere from several days to a month inside a separate medical wing called an “isolator” (isoliator). Children are assigned to beds where they are expected to spend their days with little stimulation while staff monitor their health. The purpose of an isolator is to ensure that children do not carry contagious illnesses into the institution. While children reside in isolators they do not study, interact with other children, or play, allegedly because they need to be watched for signs of infection.[75]

Some staff also claimed that they place children in isolators so that they do not carry illnesses back into the institution after visits with their families.[76] However, some institution staff stated explicitly that the isolator served as a disciplinary method for children returning from visits with relatives, who are assumed to overindulge children.[77] For example, one specialized state institution doctor told researchers, “Children return from home spoiled by their parents. They’ve grown used to too much attention. They need to calm down.”[78]

Time spent in isolators can be emotionally damaging to children. The vice director of an orphanage for children with developmental disabilities in northwest Russia explained to Human Rights Watch why a 16-year-old girl stared at her desk instead of responding to the vice director’s question of what she was drawing. “She’s just spent a few days in the isolator,” said the vice director. “Children sometimes return from there shut down [zamknuty].”[79] In Pskov region, a 25-year-old man named Andrei M. who has a developmental disability reported that he was forced to spend a month in an isolator at the age of 10 upon his transfer to a specialized state children’s institution. He said, “It was tedious and lonely. I missed my family. I didn’t know what was going on. There was nothing to do.”[80]

Psychological Violence

In 8 of 10 institutions for children with disabilities that Human Rights Watch visited, researchers documented how staff issued threats against children, including death threats and threats of beating or psychiatric hospitalization, as punishment for behavior deemed “bad” or “wild”; called children derogatory names such as “vegetables” and claimed children have no potential to learn or live independently; denied children attention; and either actively denied children’s contact with relatives or failed to take measures to facilitate such contact.

The 2006 UN report, World Report on Violence Against Children, identifies nonphysical forms of violence typically inflicted on children that can be “detrimental to a child’s psychological development and well-being” to include persistent threats, insults, name-calling, ignoring, isolation, rejection, threats, emotional indifference, and belittlement. [81] While little is known about the effects on children living in institutions, in families characterized by nonphysical forms of violence “there is constant fear and anxiety caused by the anticipation of violence; pain, humiliation and fear during its enactment; and in older age groups, the loneliness of parental rejection, distrust, and at times self-disgust.” [82]

Threats

A 22-year-old man with a developmental disability named Kostya K. told Human Rights Watch that staff from a Pskov region specialized state institution where he lived from age 5 to 18 (1997 to 2010) repeatedly threatened him and other children with psychiatric hospitalization when they ran in their bedrooms or in the hallways. Kostya K. said, “Staff said, ‘If you roughhouse, you’re going straight to Bogdanova [a nearby psychiatric hospital].”[83] Nine other children and young people with disabilities who lived or have lived in institutions reported that staff threatened them with psychiatric hospitalization if they roughhoused, ran indoors, or were late for meals.[84]

Insults and Derogatory Language

In four regions, researchers observed many incidents in which staff referred to children as “vegetables” (ovoshchi) in children’s immediate presence to denote their alleged lack of intelligence or social responsiveness. For example, in Sverdlovsk region, Human Rights Watch visited one orphanage for children with developmental disabilities. While a researcher was speaking to a group of small boys, a staff member approached and stated, “They’re vegetables. They don’t understand anything.”[85]

In a “lying-down” room in a northwest Russia specialized state children’s institution a Human Rights Watch researcher attempted to speak with Sveta, a 15-year-old girl with a developmental disability. However, a staff member immediately approached the researcher and said, “She can’t understand anything. She’s uneducable.”[86]

In another case, a researcher was speaking with one institution staff member when a 13-year-old girl approached, sat next to the researcher, and leaned against her. The staff member slapped the girl on the arm and said to the researcher, “She’s a schizophrenic. Let her touch you, and she’ll hang on you like an insect.”[87]

Neglect by Caregivers

Several activists whom Human Rights Watch interviewed stated that lack of individualized attention from orphanage caregivers is a significant problem in orphanages for children with disabilities across Russia.[88] As noted above, lack of stable caregiver relationships for young institutionalized children can cause severe psychological damage and has been equated with violence.[89]

Children’s rights activist Yana D. worked in two specialized state institutions for children with developmental disabilities in northwest Russia from 2006 through 2008 and a third from 2008 through 2009. She reported that two to three “lying-down” rooms in each of these institutions had only one institution staff member per 13 children. Further, the staff in these rooms lacked pedagogical training. As a result, Yana D. said, “Other than having basic needs such as diaper changes taken care of, children had no individualized attention. They also never left the rooms.”[90] Yana D. also underscored the consequences of isolation for children she worked with:

Usually, the media calls attention to cases of harsh treatment, deep medical problems, and poor nutrition in children’s homes. But deep isolation is also very harsh treatment. People don’t understand that. Staff will say, “These children are very difficult, they don’t understand anything. Why give him attention?” In fact, the more severe the disability, the more attention [the child] needs, the more you need to work with him.[91]

Because of understaffing and because the children in “lying-down” rooms are seen as especially weak and in need of attention, many NGOs run volunteer programs to provide these children with additional attention and care, such as more frequent diaper changes. Often, the only social interaction that children get is from these volunteers who visit on a semi-regular basis.[92] Several current and former volunteers in state institutions for children with disabilities reported to Human Rights Watch that staff in the institutions where they have worked have discouraged them from paying attention to particular children by playing with them regularly or taking them on outings into the community on the basis that individualized attention would “spoil” children by giving them attention that they would not always receive.[93]

Discouragement of Family Contact

Human Rights Watch research in Russia found that staff of some children’s institutions actively discourage children from having contact with their parents and other relatives or do not take sufficient measures to facilitate such contact, despite Russia’s obligations under federal law and as party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child to protect the rights of the children separated from one or both parents to maintain regular contact with parents.[94]

Staff at two separate institutions reported to Human Rights Watch that they do not attempt to contact children’s parents and discourage visits claiming that children tend to be “spoiled” by special treatment on the part of their parents and return from family visits prone to misbehavior.[95] In St. Petersburg, children’s rights activist Alexander D. told Human Rights Watch, “Some doctors [at specialized state institutions] tell parents not to visit because their presence upsets children.”[96] Karina M., the mother of a 19-year-old young man with a developmental disability who has spent his life living in institutions in northwest Russia, reported to Human Rights Watch that institution staff sometimes prevented her from spending time with her son outside the territory of the state orphanage where he lived under the rationale that he would bring infections back into the institution.[97]

Several senior specialized children’s home staff whom Human Rights Watch interviewed claimed that there is no system in their institutions to connect children with their parents and relatives.[98] Human Rights Watch spoke with three children and young people currently or formerly living in state institutions who requested information about their parents and relatives and were told by staff that such information was unavailable.[99] Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm whether staff actually did not have such information or did not wish to facilitate such contact.

Many state institutions are located remotely from cities. All of the institutions that Human Rights Watch visited were located far from city centers and most were not reachable by public transportation. The hours and travel costs can create significant obstacles for many Russian families.

Lack of Effective Complaint Mechanisms

Several children whom Human Rights Watch interviewed stated that they did not know of any way to file a complaint or receive help after facing abuse. Others attempted to complain about abuse to another staff member and were not given help or were afraid to complain out of fear of retaliation or punishment. For example, Nastia Y., whose case is also described above, appealed to the institution psychologist after an institution staff member beat her: “I asked [the psychologist] to help me so that it would not happen again, and she told me there was nothing she could do to help.”[100]

Anton K., a young man with a physical disability who grew up in a specialized orphanage in northwest Russia, reported that institution staff members and doctors often beat him and his peers with belts and mops and poured cold water on them when the children attempted to leave their bedrooms and go into the courtyard without permission. However, he knew no way to report the staff’s behavior. Anton K. said, “I just wanted to see them judged. My heart’s last desire is justice.”[101]

All Russian children have the right to legal protection by their parents, their legal guardians, by guardianship and custody agencies, the prosecutor’s office, or the courts. Children “with full legal capacity” have the right to independently exercise their rights and obligations, including their right to protection.[102] If a child’s rights are violated, the child has the right to independently apply for protection to guardianship and custody agencies, and at age 14, to a court.[103] Officials and other citizens who learn of a threat to a child’s life or health or of a violation of his or her rights and legal interests are obligated to inform guardianship and custody agencies in the city or region where the child lives. Upon receiving such information, the guardianship and custody agencies are obligated to take necessary measures to protect the legitimate rights and interests of the child.[104] According to Inna A., an expert on people with disabilities living in Russian state institutions, these children usually are unaware of their rights and the procedure for appealing to guardianship and custody agencies and lack access to the Internet or other means of filing a complaint independently. “It’s [only] parents or orphanage volunteers who make it possible for children to appeal to authorities,” Inna A. stated.[105]

Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), states parties must guarantee the right of a child capable of forming his or her own views to express those views freely in all matters that affect the child, giving due weight to the child’s age and maturity.[106] The state must also ensure that children enjoy safe and effective means of reporting maltreatment.[107] The CRC also guarantees children the opportunity to be heard in any judicial and administrative proceedings that affect him or her, either directly or through a representative or other “appropriate body.”[108]

As party to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), as part of its efforts to protect persons with disabilities from all forms of violence, states parties should provide persons with disabilities and their families and caregivers with “information and education on how to avoid, recognize and report instances of exploitation, violence and abuse.”[109] Protection services must be age-, gender-, and disability-sensitive.

Lack of Effective Monitoring: “No One Checks on the Child”

Russia lacks federally enforced monitoring mechanisms to ensure that children with disabilities live free from neglect and abuse. Under Russian law, guardianship and custody agencies at the regional and city level are responsible for regularly monitoring conditions in all state residential institutions for children.[110] One activist, Tatiana O., who oversees volunteer programs in several state institutions for people with disabilities and runs an organization advocating for stronger monitoring mechanisms in these institutions, reported that in her experience, inspections by these agencies are not sufficiently thorough. “No one checks on the child,” she said. Having witnessed inspections of a number of occasions in different institutions in northwest Russia, Tatiana O. observed that inspectors did not speak with children or examine children’s physical conditions. The inspectors limited their inspection to whether the institution followed sanitary regulations, whether the appropriate number of medical personnel were working in the facilities, and whether children living in the facilities are of the right age.[111] Two other activists, one working in a specialized children’s home in northwest Russia and the other in specialized children’s homes in Moscow and Tula regions, reported that guardianship and custody agency inspectors do not pay attention to whether specialized orphanages protect children’s rights, focusing instead on formal indicators such as whether children of the right ages and with the correct diagnoses are located in the correct institutions.[112]

In December 2012 Deputy Prime Minister Olga Golodetz issued written instructions authorizing the creation of commissions to inspect all specialized state institutions for people with disabilities, including children’s institutions. The instructions indicate that commissions can include regional officials and NGO representatives but do not specify the content of the inspections.[113]

In line with these instructions, NGO activist Anna A. organized an independent commission of NGO representatives with many years of experience working to protect the rights of children with disabilities living in Russian state institutions. The commission was able to inspect three specialized state children’s homes for children with developmental disabilities in one region in 2013. However, Anna A. told Human Rights Watch that in several cases, institution staff did not grant inspectors access.[114]

Another Moscow-based NGO providing rehabilitation services to children with disabilities and their families visited seven different specialized state children’s homes in 2013 and publicly reported problems such as overcrowding and a high proportion of children with disabilities living in institutions in spite of having at least one living parent.[115]

States parties to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities are obligated to monitor the convention’s implementation, including in all institutions and programs serving persons with disabilities. States parties must determine focal point(s) within the government tasked with implementing the convention and establish a coordination mechanism “to facilitate related action in different sectors and at different levels,” which Russia has done through the formation of a coordinating council to implement its National Action Strategy in the Interests of Children for 2012-2017, as described below. States parties should also create, maintain, and strengthen mechanisms to monitor implementation of the CRPD, involving civil society and DPOs in particular, in the monitoring process.[116] In order to prevent all forms of violence, abuse, and exploitation, states parties must ensure that all facilities and programs created to serve people with disabilities are monitored by independent authorities.[117]

III. Neglect and Lack of Health Care, Education, and Play

In all 10 institutions that Human Rights Watch visited, researchers documented many cases in which children suffered various forms of neglect, namely lack of adequate nutrition, inadequate health care, lack of access to rehabilitation services, lack of access to education, and insufficient access to leisure and play.[118]

Many children with disabilities whom researchers met appeared significantly physically underdeveloped for their ages. Many also had protruding ribs and were unable to walk or crawl, despite the absence of physical or developmental disabilities that may have prevented them from being able to do so. According to several activists, factors affecting children’s lack of physical development include feeding methods that are inappropriate for children based on their disabilities, diets that fail to meet children’s caloric and nutritional requirements, and lack of stimulation and freedom to move.

These abuses and forms of neglect were particularly pronounced among children confined to “lying-down” rooms. These wards, where children spend their days in cribs, house children whom state officials have deemed to have particularly severe disabilities on the basis of an arbitrary exam given to children with disabilities to determine their placement in institutions (see below regarding the PMPC exam).[119] The children whom Human Rights Watch observed in lying down rooms were usually unable to walk and talk.

Children living in other parts of institutions, while also facing various forms of neglect such as lack of sufficient opportunities for education, recreation, and leisure, were usually free to move around the rooms where they spent most of their days and sometimes to play with toys.

Human Rights Watch has determined that the practice of confining children with certain types of disabilities to “lying-down” rooms, where children receive minimal care and are given little or no opportunity or support for physical, emotional, or intellectual growth, amounts to inhuman and degrading treatment and should be abolished. The practice also discriminates against children with particular types of disabilities. The exam administered by local-level Psychologo-Medico-Pedagogical Commissions to children that typically determines their placement in institutions, including in these types of rooms, is also discriminatory, as detailed below.

Lack of Adequate Nutrition

Interviews with activists and children and young adults with disabilities, as well as Human Rights Watch’s firsthand observations, suggest that many children with disabilities living in Russian state institutions lack adequate nutrition and water to facilitate their full development. Human Rights Watch research identified several problems, including lack of sufficient calories and an adequately varied diet, sufficient drinking water, and knowledge on the part of the staff of these homes about appropriate feeding methods for children.

According to one disability and children’s rights activist:

Food is a big problem in specialized children’s homes in Russia. The children do not get enough calories to allow them to develop. The quality and variety of food is also insufficient. Doctors don’t think that the children have any potential to develop and they feed them the same thing every day.[120]