"At the State Department...every week is Human Rights Week."

That's what US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton told an audience at Georgetown University in Washington in December. Clinton's speech, on the heels of President Obama's lofty rhetoric at the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo, sought to clarify the administration's approach to human rights. Clinton laced the speech with tangible accomplishments, ranging from the US's willingness to rejoin the UN Human Rights Council to pushing for international condemnation of rape as a weapon of war.

But when it came to China, the speech spotlighted the Obama administration's flawed approach. Clinton identified a few of the human rights problems the US sees in China-minority rights, religious freedom, and freedom of expression-but quickly moved on to wax nostalgic about the 1995 Beijing Women's Conference.

A year of the Obama administration playing nice to Beijing-while down-playing the deteriorating human rights environment-has left it stunned by Beijing's hostility. Recent flashpoints include US approval of arms sales to Taiwan (with China's response as inevitable as death and taxes), Google's protests over internet account hacking, and the Dalai Lama's visit to Washington this month.

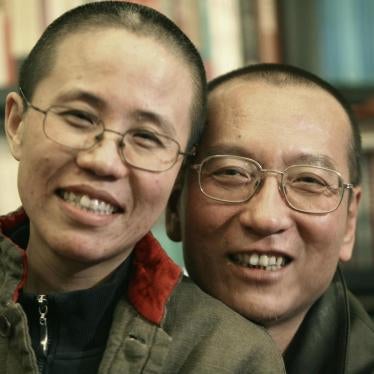

In December alone, China sentenced Liu Xiaobo, a prominent writer and academic, to 11 years in jail on baseless subversion charges, executed a profoundly mentally ill British citizen, and forced Cambodia to return to China 20 Uighurs who will almost certainly face maltreatment or worse.

Instead of addressing in a straightforward way the Chinese government's dismal rights record, Secretary Clinton sketched out what might be called American exceptionalism for China, which involves "engaging in tough negotiations behind closed doors," a highly problematic approach whose necessity she did not bother to explain. She stressed that "The United States seeks positive relationships with China and Russia." This would be unobjectionable if she hadn't then dismissed tough diplomatic measures, including speaking out in public about abuses, as a means for improving human rights in China. These comments add up to a troubling double standard, and one could understand why the heads of abusive governments in small, poor countries may now be clamoring for the "China treatment" from the US.

Clinton's speech followed her now infamous statement last February that human rights "shouldn't interfere" with the bilateral relationship. That was almost immediately followed by an embarrassing public plea to the Chinese leadership to continue to purchase US Treasury bonds, paving the way for a year of diminished US voice as the human rights environment in China continued to degrade. President Obama's first trip to China was also a disappointment for human rights activists, as the extent to which the administration tolerated Chinese government efforts to restrict his public comments and activities only contributed to a sense of weakness.

Secretary Clinton struck the right tone in her recent speech on Internet freedom, demanding among other things that the Chinese government investigate Google's allegations of hacking. But even in this setting Clinton seemed to feel compelled to note that the US and China have "different views" about freedom of expression. That follows on repeated public comments that the US and China will "agree to disagree," suggesting that the Chinese government need not heed the US's concerns, and that the Obama administration isn't going to push them.

Her criticisms appear to have caught Beijing-accustomed to the administration's flaccid approach-off guard, eliciting a furious denial and shrill insistence that the US is trying to "denigrate China." This is a textbook example as to why American administrations need to be unambiguous, public, and above all consistent about human rights in China. Soft-pedaling up front weakens your position, giving the Chinese government an excuse to say that you've changed course.

One can only imagine how disheartening these weak positions are to human rights activists in China, who count on US and other international support to keep going.

The US government's approach also shows a lack of sophistication and confidence about its relationship with China. With widespread social unrest and per capita income less than 10 percent of that of the US, China needs the US as much as the US needs it. While the US is surely worried about the economic repercussions of damaging its relationship with China, it must realize that Beijing too would suffer tremendous damage from any abrupt change.

The Chinese government, which is famous for suppressing information through its massive censorship of the Internet, could only be delighted at Clinton's willingness to rely on private diplomacy. Unless the administration changes course and publicly begins to hold the Chinese government to its human rights commitments, we can expect Beijing to continue to feel empowered to insist that the U.S. treat China differently than it does other countries when it comes to basic human rights requirements.

The US and others need to stick to principles in dealing with China. US officials should listen to the business and legal communities, academics and civil society groups who say that China is backsliding on its rights commitments. "Agreeing to disagree" not only leaves China's domestic human rights community high and dry (defeating at least one of the Secretary's stated objectives), but it also compromises a host of US interests that are predicated on the rule of law, an independent judiciary, and freedom of expression.

The solution is for Secretary Clinton and the Obama administration to be clear, consistent-and, as Clinton herself stressed-to hold everyone, including the Chinese government, to universal standards.

Sophie Richardson is Asia advocacy director at Human Rights Watch.