As humanitarian agencies set up camp operations in 2012 and 2013, Myanmar national and state authorities repeatedly denied their requests for adequate land and resources to build sites in line with international standards. Instead, the government enforced strict technical guidelines that made overcrowding, flooding, and fires inevitable. “UNHCR [the UN refugee agency] would say, this plot can fit 800 houses, and they’d make us put in 1,200,” a UN official involved in the construction said.

Restrictions on aid groups have only grown over the past decade. The temporary shelters, originally designed to last just two years, have deteriorated with each passing monsoon season, prompting unending cycles of repair. The resulting living conditions are, by design, squalid.

“The camp is not a livable place for us,” Anwar Islam said.

“It is impossible to convey the degradation of life in these camps,” said Michael McGrath, then-Myanmar director for Save the Children, in 2019. “I have visited them many times, and they are among the worst places to live and to bring up children that I have seen during a long career in humanitarian work around the world. Families are crammed into a single room in a five-family ‘longhouse,’ bordered by endless lines of latrines in a sea of mud.”

Most of the sites sit on former paddy fields and low-lying coastal areas. During annual floods, the latrine pits overflow, contaminating hand pumps and wells and spreading disease.

In April 2022, with the monsoon season looming, the UN reported new restrictions imposed by the junta on infrastructure projects in the camps, leaving 28,000 Rohingya in unfit longhouses requiring urgent repair, many that “pose life-threatening risks to the inhabitants and other residents.”

Humanitarian agencies report Rohingya children drowning in poorly secured latrine pits, wells, and stagnant ponds. After multiple fatal incidents in 2014, aid groups asked the government irrigation department for support to improve safety measures, without success. A 2019 humanitarian document notes—after another child died in a latrine—that almost all open water sources still lacked fencing.

Overcrowding among the camp longhouses and makeshift shelters is pervasive. “Things haven’t improved,” Aung Zaw Min said. “We are still in the long shelters, in the same situation. One shelter is only one room for all family members, and one long shelter has eight rooms for eight families from different places. In my family, we are 13 people. It’s difficult to fit in one room. We have no privacy.”

The uninhabitable conditions have led to a growing tally of preventable deaths. The UN-backed Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar concluded that security forces had “deliberately inflicted conditions of life calculated to bring about the physical destruction of Rohingya”—or “measures of slow death”—a genocidal act.

Rohingya living in the camps face higher rates of malnutrition, waterborne illness, and child and maternal death than their Rakhine neighbors. Health indicators have only worsened over the past 10 years. Children continue to die from recurrent outbreaks of acute diarrhea, as recently as February 2022.

Access to health facilities is mostly limited to basic in-camp clinics operated by nongovernmental organizations. Visiting Sittwe General Hospital, the only site for complex care that accepts Rohingya, requires excessive fees and an onerous referral process, even for life-threatening cases. Muslim patients are treated in a segregated ward under guard; blood donations are earmarked for ethnic Rakhine only.

“It’s difficult to prevent problems during delivery,” Myo Myint Oo said of the life-threatening risks to pregnant women and newborns. The women in his camp give birth with untrained attendants, he said. “Sometimes the mother and child die.”

Fears of Sittwe hospital are commonplace, fueled by rumors of callous doctors and unexplained deaths, fostering a reluctance to seek care until too late—a deadly cycle.

“Sometimes we didn’t take our children to the doctor because we believed that when our people go to the doctor, they don’t come back alive,” Hamida Begum said. “Sometimes our children died in our laps. We didn’t want them to die by Buddhist doctors. When our children died from lack of medical treatment, we had to bury them without any funeral.”

For most of the 72,000 children in the camps, access to education is limited to under-resourced temporary learning centers led by volunteer teachers.

Humanitarian groups say families are less and less motivated to seek out the minimal informal schooling that exists. They see no opportunities for their children, an aid worker said. “They think, ‘What’s the point of sending my kid to school? What can they do?’”

“My two sons used to go to the temporary learning centers since there were no school facilities,” Hamida Begum said. “There is no future there.”

More than 40,000 children have been born in the camps, knowing no life outside of confinement.

Depriving Rohingya of education serves to permanently marginalize the community, cutting off younger generations from imagined futures of self-reliance and dignity. Forcing children to grow up without learning Rakhine or Burmese languages, only speaking Rohingya, is hardening the barricade of segregation.

Kamal never returned to school after the violence broke out in 2012. Instead, he found occasional work with an aid group that paid 30,000 kyat (US$20) a month.

Most Rohingya were forced to abandon their pre-2012 trades. Former teachers and shopkeepers were left seeking ad hoc work as day laborers for an average of 3,000 kyat ($2) a day, largely dependent on foreign aid.

“Before 2012, I used to go to the main Sittwe port with my boat,” said Nur Kamal, who had worked as a fisherman before he was sent to the camps. “I lost my boat forever. Life became very hard. There was no freedom of movement, no work opportunities. Nothing was there after losing my boat.”

The lack of work has pushed large numbers of Rohingya to attempt high-risk escapes. Since 2012, about 170,000 Rohingya asylum seekers have embarked on smugglers’ boats in the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea, most hoping to reach Malaysia where a sizable Rohingya community holds the promise of work.

The voyages entail weeks or months on unseaworthy boats, often accompanied by abuse from unscrupulous traffickers. Sultan Ahmad has seen many flee from his camp. “Sometimes the people on the boats get arrested,” he said. “Sometimes they have to change direction because of the weather conditions; sometimes the boats sink and they die in the sea. But people still take the risk, because they say they can’t stay at home detained in the camp, and they don’t think they will ever be free.”

In April 2014, Myanmar census workers arrived at Kamal’s camp, flanked by police and military officers. For Rohingya, who were excluded from the nationwide census unless they identified as “Bengali,” the surveyors’ questions were brief. “The census team asked me, ‘What is your ethnicity?’” a man from Dar Paing camp said. “When I answered ‘Rohingya,’ they walked away.”

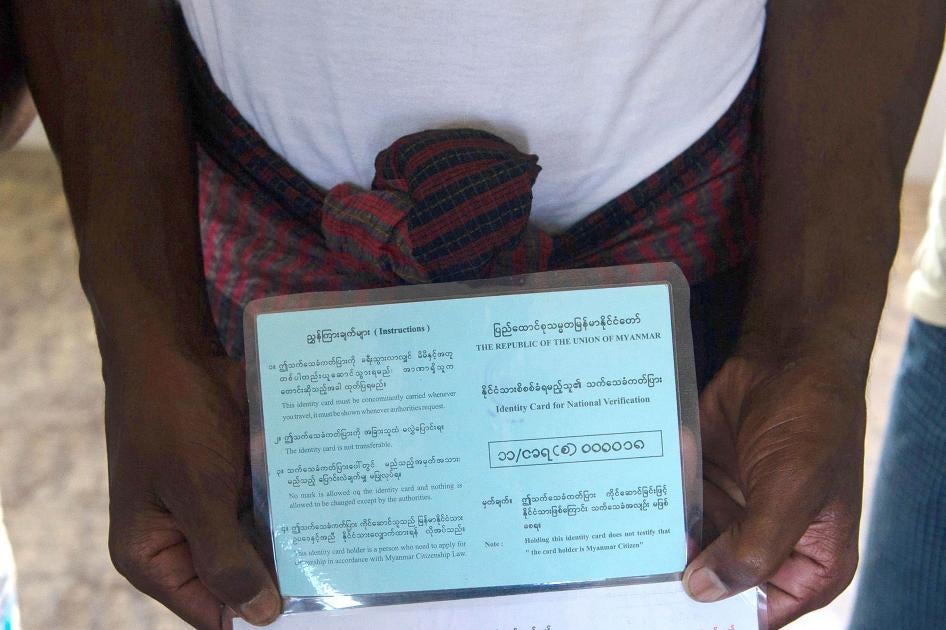

Rohingya’s right to nationality and identity has been steadily eroded over decades. In 1982, the military government adopted a new ethnic-based Citizenship Law that effectively denied the Rohingya citizenship, rendering them the largest stateless population in the world. Authorities collected and voided identity cards, replacing them with a succession of increasingly restrictive and regulated IDs.

The 1982 law leaves Rohingya exposed with no legal protection of their rights. By linking ethnicity to citizenship, and citizenship to freedom of movement and other basic rights, authorities created a multilayered system of oppression.

“They say we are foreign settlers,” a Rohingya man said. “My grandfather had a citizenship card. My mother. My father. My older brother. But they say I am not a citizen.” During the 2012 violence, officials and Rakhine villagers confiscated and burned many Rohingya’s documents. Some have kept past IDs, no longer recognized, a tangible link to their identity, the denial of which winds through everything else they’ve lost.

After the 2012 violence, the influence of Buddhist ultranationalist groups grew, tapping into the nationalist narrative that framed Muslims as an existential threat to the Buddhist state. Dehumanizing rhetoric spread nationwide.

Across Rakhine State, the infrastructure of apartheid eroded communication between the Rohingya and Rakhine, fostering deep mistrust and solidifying the “Rohingya other.”

Despite being disenfranchised in the 2015 national elections, many Rohingya held out hope that Aung San Suu Kyi and her party, the National League for Democracy, having won in a landslide, would end their internment and stem the hateful propaganda that pulsed in streets and, with growing fervor, online.

“After the 2015 elections, they have hope in the camps,” said Myat Noe Khaing, who had fled Rakhine State the year before. “They think things will change. After one year, they realize the Lady [Suu Kyi] will not do anything for us.”

In 2016, Suu Kyi, then leader of the country, instructed the UN and foreign governments not to use the term “Rohingya.”

Myat Noe Khaing wonders about the fate she has faced for simply being Rohingya. “Am I wrong? For being Rohingya, being from Rakhine? I ask myself, what did I do wrong? But there is nothing wrong with me.”

In October 2016, an ethnic Rohingya armed group called Harakah al-Yaqin, which had formed in response to the 2012 violence, attacked three police outposts in northern Rakhine. Security forces responded with so-called clearance operations, killing and raping Rohingya and torching their towns.

In August 2017, after new attacks by the armed group, since renamed the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), the military launched a sweeping, methodical campaign of massacres, rape, and arson. Thousands were killed. More than 730,000 Rohingya fled the genocidal acts for Bangladesh.

Central Rakhine grew increasingly militarized. In the camps, authorities set up new checkpoints and lengthened curfews. Police raids of shelters became more frequent, Rohingya said, “even to see if there is a knife in the kitchen.”

In one incident in October 2016, police rounded up a group of young Rohingya men from the Sittwe camps. “They told us not to create any problems for them and asked us to let them know if there were any ARSA people inside our IDP camps,” one man said. “They kept hitting us.”