- Arrests of Protesters

- Targeting of Protest Leaders

- Abuse of the Indian Penal Code

Key Individuals Named in this Report

I. Summary and Recommendations

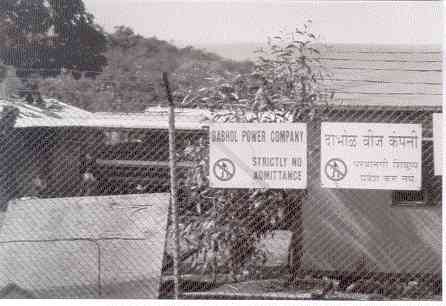

II. Background: New Delhi and Bombay

III. Background to the Protests: Ratnagiri District

IV. Legal Restrictions Used to Suppress Opposition to the Dabhol Power Project

V. Ratnagiri: Violations of Human Rights 1997VII. Complicity: The Dabhol Power Corporation

VIII. Responsibility: Financing Institutions and the Government of the United States

Appendix A: Correspondence Between Human Rights Watch and the Export-Import Bank of the United States

Appendix B: Report of the Cabinet Sub-Committee to Review the Dabhol Power Project

Appendix D: Correspondence Between the Government of India and the World Bank

During the 1997 protests against the Dabhol Power project, individuals identified as “leaders” of the opposition were detained through the use of preventative detention laws and targeted externment orders that have restricted their movement and prohibited their entry into areas where opposition to the project was most active. The logic of these measures has been to weaken resistance by forcing villagers to participate without leadership and to demoralize those most vocal in their opposition to the project.

Sadanand Pawar, an economics professor who is from Pawarsakari village in Ratnagiri district, and a recognized leader of the protests against the DPC project, told Human Rights Watch:

In a democracy, you have a right for a civilized demonstration, [but] this does not exist at all. Meaningful agitation cannot be organized or sustained because the police, backed by the government, victimize the people... Section 144 [of the Code of Criminal Procedure] is always there: if you hold meetings, they can frame you. Now the police are bold, they will charge you with all sorts of things... It works like this. First you will get a notice that you are an agitator, spreading false information to the people, and inspiring people to riot and destroy things. And if anything happens, you will be held responsible.135

Medha Patkar and B.G. Kolse-Patil: March 1997

An excerpt from an order issued under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure on March 1, 1997, by T. Chandrasekhar, the district magistrate of Ratnagiri, the highest-ranking law enforcement officer at the district level, illustrates the intent of these orders. In this case, the prohibitory order was issued against environmentalist Medha Patkar and retired Bombay High Court Judge B.G. Kolse-Patil, two recognized leaders of demonstrations. The order states:

ORDER

Sub: Prohibitory orders issued u/s 144 of Cr.P.C.

Whereas it has been brought to my notice that in Guhagar Taluka, Shri B.G. Kolse Patil and Smt. Medha Patkar, leaders of the Anti-Enron Agitation Group have been conducting meetings of the villagers in the Enron Power Project affected villages as well as in the surrounding villages of the Enron Project in Guhagar Taluka. It has also been brought to my notice by the Superintendent of Police, Ratnagiri, that these persons are instigating the villagers against the Dabhol Power Company (Enron Power Project) and proposed Land Acquisition by the M.I.D.C. and indulging in Rasta Roko, Morchas by violating prohibitory orders in violation of the provisions of section 37(1)(3) of the Bombay Police Act, 1951 and creating a law and order problem in Guhagar Taluka. It is apprehended that the activities of Shri B.G. Kolse Patil and Smt. Medha Patkar may cause a breach of peace and law and order problem during the ensuing Zilla Parishad Panchayat Samities Elections which are to be held on 2nd March 97. It is therefore necessary to prevent Shri Kolse Patil and Smt. Medha Patkar from entering into Ratnagiri District.136

The intent of the order was clear: to prohibit leading opponents of the Dabhol Power project from exercising their right to freely express their views in order to prevent opposition to the project from becoming an election issue.

Another incident involved Patkar and some of her colleagues from the National Alliance of Peoples’ Movements (NAPM), and took place in the town of Mahad, near the Dabhol Power project. Under the pretense of preventing damage to property and loss of life, police served Patkar with prohibitory orders under Section 144 on May 29, 1997 and then surveilled, arrested, beat, and detained the activists—on the eve of her departing for Raigad and Ratnagiri districts with plans to lead a series of protests against the DPC project and other industrial projects. The incident merits detailed treatment. Due to its being subsequently investigated by the Indian government’s National Human Rights Commission, it is unusually well documented and provides a close look at the process driving the issuance of prohibitory and externment orders.

The National Human Rights Commission determined that the order against Patkar under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure was “unjustified.”137 The behavior of the government led the commission to comment:

The case of Ms. Medha Patkar deserves anxious attention...as some basic human rights issues are involved. In a free and democratic setup, the Fundamental Rights of individuals cannot be allowed to be infringed upon with impunity...State machinery should not be misused for ulterior aim and gains of the party in power, out to strangulate the voices of dissent.138

The commission determined, moreover, that the human rights violations committed by the police were due, in part, to an order given by Maharashtra Chief Minister Manohar Joshi “to deal with the situation...firmly or else the wrong signal would be conveyed to the business world.”139 At the time, Chief Minister Joshi was on a five-nation tour of Asia seeking to attract foreign investment and extoll the virtues of the business climate in Maharashtra.140 Consequently, Joshi called More, and More, in turn, ordered the district magistrate, R.S. Rathod, to prevent Patkarfrom entering the district and to stop Patkar and the other activists. The commission reported:

Apprehending trouble, the CM [chief minister] telephonically spoke to Shri Prabhakar Raoji More, Minister of State for Home and State Minister of Industries (known as Guardian Minister for Raigad district), to handle the situation. Shri More in turn asked Shri R.S. Rathod, DM [District Magistrate], to immediately intervene and see the withdrawal of the hunger strike and frustrate the entry of Ms. Patkar to the district. The DM sprung into action and in consultation with the SP [Superintendent of Police], worked out a strategy to prevent Medha Patkar from entering the district.141

According to Lata P.M., deputy director of the NAPM and former director of NAPM’s field office in Ratnagiri district, the prohibitory order and the police brutality occurred just after NAPM had begun a “development tour” of the region on May 28.142 The purpose of the tour was to educate local communities about the environmental and social impacts of the Dabhol Power project and other large industrial projects in the area and to hold peaceful demonstrations against these projects.143 Lata detailed the basis of opposition to the Dabhol Power project:

Enron is symbolic of the impact of multinationals, globalization, and the right to information. How much displacement will there be? Will there be suitable rehabilitation? Fishworkers, farmers, mill owners, and local entrepreneurs would be impacted by the project. Already, local water is being taken by Enron. A jetty is being built and forests are being cut down. What is the environmental impact? What is the real price of power? What was the criteria of the arrangement? We worry about the impact of this and other “mega-projects.” 144

The tour began in the village of Chandva, Raigad district, where Patkar and other NAPM activists met with villagers and prepared for upcoming meetings andspeeches. Local villagers also decided to create an organization to oppose industrial development in the region.

That evening, the superintendent of police at Raigad, V. Lokhande, received a report that a communist youth front was organizing a hunger strike at the gate of Indian Petrochemicals Limited (IPCL), another industrial project in the area, and had asked Patkar to speak there as a show of support. In addition, Lokhande received a written complaint from IPCL personnel alleging that unknown individuals might “endanger the security of the plant” and asking police to address the issue.145

Over the telephone, the district magistrate, R.S. Rathod, persuaded the youth front to call off its hunger strike and then apprised Minister More of the situation. Although the demonstration was canceled, Minister More, who had just spoken to Chief Minister Joshi, ordered Lokhande to restrict Patkar’s entry into the district anyway and to control any “law and order” problems. Lokhande informed Rathod who, in turn, issued prohibitory orders against Patkar under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. The prohibitory order states, in part:

[A]nd whereas I have satisfied myself that it is necessary to take speedy steps for immediate prevention of damages to prevent human life, disturbance of public peace and tranquility, riot or affray and to maintain the law and order situation and industrial peace and the grounds brought on the record lead me to treat this as a case of emergency and accordingly to pass ex-parte order.

Therefore, I do hereby u/s 144 of Cr.P.C. order and direct that you should not enter into the boundaries of Raigad District from the date of this order, i.e. 28th May, 1997 to 30th June, 1997 (both days inclusive).146

On the evening of May 28, the superintendent of police, V. Lokhande, ordered Special Deputy Police Officer Vijay Singh Jadhav to serve Patkar with the order and to ensure that she did not enter the district or participate in any demonstrations or other events.147 On May 29, at approximately 7:30 a.m., Jadhav took two female police officers, one sub-inspector, and ten male officers to theTolphata Highway Trijunction near the town of Mahad and waited for Patkar to approach. In addition, two police officers were sent to Chandva village “to cover the movement of Ms. Patkar and her activities covertly.”148

Approximately fifteen minutes later, two jeeps carrying Lata and some five other activists were spotted by Sub-Inspector (SI) Magdoom, who contacted Jadhav by police radio and told him that Patkar was not in the jeeps. As the activists approached Jadhav at the trijunction, police stopped them. According to Lata:

The police stopped the jeeps at Tolphata, a quiet place near the Mahad-Bombay highway which heads towards the Konkan highway. There were about thirteen male and two female police that attacked us, and about twenty or twenty-five more police were in accompanying police jeeps and vans.149

Jadhav told them that they were prohibited from holding a public meeting under Section 37 of the Bombay Police Act. When the activists protested, Jadhav informed them that they were under arrest.150 The National Human Rights Commission determined that the arrest was illegal, since Section 37 was not operative in Mahad.151 Lata told Human Rights Watch:

The special deputy police officer, Mr. Jadhav, led the police. He asked people to get out of the jeeps to be checked. He told us that we had been arrested and to get into the police vans. I asked him to show us a warrant for their arrest. He refused to produce any warrant. I asked him, “Why are you arresting us since we are going to a meeting?” He said that I should not ask any questions and that he had the authority to arrest us under the Bombay Police Act.

People refused to go into the van, people were standing around. One woman was sixty years old, one woman had her child with her, and three college-aged girls were there. Some were standing, some were sitting in the jeep. We told the police that we wanted to wait for Medha, because we thought she had already been arrested.152

Lata tried to flag down a truck in order to ask the driver to inform Patkar or their associates in Bombay of their arrest. The police intervened and told the driver of the vehicle to leave, then the police started motioning vehicles to drive on. Lata and the other activists then staged a sit-down and asked the police to provide the grounds for their arrest. In response, the two female police officers grabbed Lata by her hair and throat, smashed her head against the police van, and beat her with their lathis and fists on her head and legs.153

Two of the women pleaded with police to stop beating Lata, while trying to grab her away from the police. According to Lata, Sub-Inspector Vijay Kadam tried to tear the womens’ clothes off and slapped Lata. While the scuffle continued, a message came over police radio that Patkar had arrived at the Mahad bus stand. The police took Lata and the others to intercept Patkar.154

At the bus stand, police served Patkar with the prohibitory order. At approximately 1:00 p.m., a bus destined for Bombay arrived at the bus stand. Patkar and thirty-one other activists boarded the bus with the intention of returning to Bombay. The bus driver protested their entry, citing a lack of capacity and mechanical difficulties. About an hour later, the police allowed the bus to continue towards Bombay, under a police escort.155

Two hours later, at approximately 4:00 p.m., the police diverted the bus to the Mangaon police station. There, police ordered passengers not affiliated with Patkar to vacate the bus “fast or they would be beaten up.”156 Once those passengers disembarked, police boarded the bus and beat the protesters. Lata, who was on the bus, told Human Rights Watch:

When we were on the bus, two goondas [thugs] and police entered the bus and told us to get off the bus. Sub-Inspector Vijay Kadam and four female officers came. They first caught the men, then the women. One of the police officers started slapping and beating Prita, a nineteen- or twenty-year-old college student. Vijay Kadam was using the scarf of her salwaar kameez [a dress with a tight pant and loose top and scarf] to strangle her and was trying to tear her clothes off. Prita’s sister started crying when she saw this, and then the female officers started to beat her as well. They threw Medha from the bus. I tried to save Medha, but the police grabbed me and started banging my head againstthe steel handrail in the bus. They started beating me on the head, which made me dizzy and disoriented. They were beating everyone on the head, and one girl was being beaten with a lathi. During this time, we kept on asking the police to produce court orders proving they had grounds for the arrest.157

After beating the activists, police arrested them; they were detained in the lockup at the Mangaon police station. Seven women were placed in one cell and twenty-five men in another. The police offered them food, but the activists refused. Lata told Human Rights Watch:

We were taken to jail around 3:00 [p.m.]. Even the sixty-year-old woman, Vijaya Sangvai, was literally thrown into the cell. We were kept in the cell for hours. The women were in serious pain, they were dizzy and vomiting from the beating. We were detained in a filthy ten-by-ten-foot cell. When men wanted to use the latrine, they were handcuffed like common criminals and led to the toilet.158

Patkar told the National Human Rights Commission that the lockups were “filthy” and that the toilets could not be used. She said that even women who required sanitary napkins were denied these requests by police. They were not allowed to see a doctor or a lawyer.159 In fact, the National Human Rights Commission determined that although the activists’ lawyer, Ms. Surekha Dalvi, made twelve phone calls to the station, police repeatedly refused to allow her to speak to her clients and then kept the phone engaged so that no one could call the station.160

Around 10:30 p.m., a judicial magistrate arrived at the police station, accompanied by a doctor. Patkar complained of the ill-treatment and the lack of medical and legal counsel. Of the magistrate’s attitude, Lata recalled:

A doctor and magistrate were brought to the jail. When we told him how we were treated, the magistrate told us that “I don’t have time tolisten to this.” He refused to hear Medha’s whole story and would not accept any oral or written statements by the arrested.161

The doctor concluded that “these injuries could not be possible due to assault.” (Later, another doctor examined the ex-detainees in Bombay and determined that they had all “suffered from trauma, and found injury marks probably due to lathi assault, fists, etc.”162) The magistrate ordered the protesters remanded to custody for fourteen days.

The next morning, May 30, at approximately 4:00 a.m., they were trying to sleep in the cell when Lata and some other women asked to go to the toilet. Special Deputy Police Officer Dadar told them not to go to the toilet but that they would be taken to Yerwada jail. They were led to a police bus and transported to Yerwada jail, approximately 200-250 kilometers away in Pune. Police did not allow them to use the toilet before the trip; instead they stopped on the highway at a creek and forced the people to go to the restroom there. During this brief outing, one of the arrested managed to give a note to a motorcyclist to tell NAPM in Bombay that they were in police custody.163

They reached Yerwada around midday. Many anti-Dabhol Power project protesters had been detained there following the protests that Patkar had been scheduled to address. They were treated well at Yerwada, and Patkar started bringing up prisoners’ rights issues. Later, on May 30, lawyers and journalists came to see them. Patkar and her colleagues were released on May 31.

Patkar and others asked the chief minister to initiate a judicial inquiry into the incident, but Joshi refused and only agreed to a police enquiry. The National Human Rights Commission intervened and, among its findings, concluded that:

Ms. Medha Patkar is a known environmentalist and has been touring the Konkan region, to create awareness amongst the people about environmental and pollution problems created by various industries/plants. She feels that multinationals entered this area with the aim to grab government land and other concessions and make quick money. This further compounded the situation. These plants have seriously endangered the ecological balance and led to ruthless exploitation of the locals who are being inhumanely evicted without proper resettlement and rehabilitation. During the course of hermeetings, she had also exposed various acts of corruption alleged to have been committed by the Ministers of the party in power, out to personally benefit from the deals. Her meeting evoked widespread response from the local people, especially the womenfolks.

The police, in utter disregard to the Fundamental Rights guaranteed by the Constitution, roughed up and humiliated peaceful and unarmed social workers, fighting for a benevolent cause. Even the women (young and some elderly) were not spared.164

The commission also found the actions of District Magistrate Rathod—who had issued the prohibitory order against Patkar—to be “prejudiced, biased, and not based on judicious discharge of his duties, as a public servant.”165 The commission was especially critical of Special Deputy Police Officer Jadhav, reporting, “His conduct was reprehensible, he took sadistic delight in committing atrocities on the unarmed and peaceful activists with the help of his subordinate police staff...” and it recommended legal action against Jadhav.166 The commission did not, however, recommend an investigation into the role of Chief Minister Joshi or Minister More for their role in the events. As of October 1998, none of the commission’s recommendations had been adopted by the state government. The commission has no power to impose punishment, and their findings remain non-binding.167

Externment orders: 1996-97

Local villagers have been subjected to externment under Section 144 and Section 151 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, as well. For example, Dattaram Jangli, a shop owner and community leader in the village of Borbatlewadi who was active in demonstrations against the Dabhol Power project, was served externment orders along with six other village leaders throughout 1996-1997. The following individuals were externed from Borbatlewadi: Dhondu Dasbud in December 1996; Bhikail Bane in December 1996; Janpath Bane on February 26, 1997; Raman Pardale and Rajesh Jangli on August 26, 1997. All of the orders state that the sub-divisional magistrate at Chiplun, under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, seeks to extern them from Ratnagiri, Sindadur, and Raigur.

Dattaram Jangli was served an externment order in May 1997 that prohibited him from entering his village. The order does not state that he is a community leader, shop owner, and participant in protests; instead it is justified on the grounds that Jangli “lives comfortably by terrorizing the people.”168 According to Jangli, “The police know that we are leaders against Enron, so if they issue externment orders, no protests will come from this village.”169

Arrests at Guhagar police station: January 1997

On January 29, 1997, the district collector (in charge of civil and police affairs) of Ratnagiri, P. Chandrashekar, and the deputy superintendent of police (DSP), Rajender Singh, called a meeting to discuss the planned demonstration on January 30. According to one participant in the meeting, the collector asked them, “Why are people agitating, what do you have against the company?”170 Sadanand Pawar, then secretary of an organization leading the demonstration, raised the issue that police were telling people not to participate in the protest and were threatening to fire on protesters the following day. After initially denying this, the collector said that if information was being spread by the police to create a “law and order” situation he would deal with it.

Between 9:30 and 10:00 p.m., local activists from Aareygaon village (about four or five activists and two villagers) came to S.D. Khare’s residence because they had decided to set up the office of the protest organizing committee across the street.171 They said that in Aareygaon, someone was spreading a rumor that a bomb blast would take place at the demonstration on January 30. Consequently, the villagers wished to lodge a complaint against the person spreading the rumor. They were under the impression that the collector and the DSP would accept the complaint because of the collector’s previous assurance that he would act on any “law and order” problems.

About an hour later, eight or nine people went to the police station, but the chief inspector was not there. The police told them that he was at the Sagar Lodge to check if any people from Bombay or other places who planned to participate in the demonstration had booked rooms in the hotel.

At the Sagar Lodge, the villagers told Circle Inspector Desmukh and Assistant Sub-Inspector P.G. Satoshe about the bomb rumor.172 The officers said that they would deal with it the next day. The activists told the police that they were just doing their job by informing the police so that they would not be accused of causing problems. The two inspectors accompanied them to the Guhagar police station to lodge a formal complaint. When they entered the police station, however, Satoshe then told everyone that they were being arrested under Section 151 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

The activists told the police that they wanted to meet with the collector or the DSP because of the previous assurances they had been given concerning “law and order” problems. Circle Inspector Desmukh told them, “Nothing doing, all your rights end here itself.”173

One of the arrested, Adinath Kaljunkar, attempted to submit a written complaint to the police concerning the rumored bomb threat. The police refused to accept it.

Around 12:30 a.m., police transported the activists to the jail at Chiplun, approximately forty kilometers away, without allowing them to notify anyone of their arrest. At Chiplun, they were still not allowed to contact anyone and spent the night in a small, cold cell with only a thin sheet to cover them. Produced before the magistrate the next morning. they told him their story and were released on personal bonds around 6:00 p.m. According to Chavan:

They wanted to arrest us because we were prominent citizens of Guhagar. The police knew that we were respected leaders of the community. In fact, Satoshe’s daughter was being tutored by one of the people he arrested, Gajannan Dixit, a local schoolteacher.174

Sadanand Pawar was arrested under Section 151 of the Code of Criminal Procedure on two occasions. On January 29, 1997, he was among the men arrested by the Guhagar police when they went to notify the authorities about a rumored bomb threat the next day. Before he was arrested, Pawar told us, the district commissioner of police threatened to kill him if he participated in the January 30 demonstration.

In the run-up to the March 1997 Zilla Parishad (local government) elections, Pawar and others opposed to the project believed that the BJP had forwarded candidates who supported the Dabhol Power project in order to minimize opposition to it. Since candidates from other political parties were also supportive of the company, they felt that voting for any candidate would undermine organized opposition. Consequently, they called for a boycott of the elections.

Four days before the election, on February 28, Pawar and another activist, Mangesh Pawar, were arrested as a preventative measure under Section 151 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.175 Police did not notify anyone that he had been arrested or later transferred to Chiplun. Pawar was kept in custody from 10:00 a.m. until about 8:30 p.m. Police took him to the magistrate at Chiplun at about 1:30 in the morning. Because it was so late, Pawar was unable to get an advocate or secure bail. Around 2:00 a.m., he was put in the lockup at Chiplun police station.

The next day, March 1, at about 4:00 p.m., some colleagues found him and obtained a lawyer. He was transferred to Ratnagiri jail and released on March 6, 1997, eight days earlier than his sentence required. The early release date, however, was conditioned on prohibiting Pawar from entering districts where there was opposition to the Dabhol Power project. The order for his release illustrates the bias police and the judiciary hold against people opposed to the Enron project. According to the order of V.G. Munshi, the sessions judge at Ratnagiri:

The applicant/accused is protesting against the Enron project and is a leader of the anti-Enron movement. They [the police] alleged that the applicant spread false information to the public which is against Enron... and the applicant met voters and urged them to boycott the Z.P. [Zilla Parishad] elections. Therefore, to keep the peace in Guhagar taluka, he should be remanded for 14 days...

Taking in to consideration all the circumstances, the applicant should be released forthwith on the condition that he should not enter within the limits of Chiplun and Guhagar talukas till 31-3-97 and not to create any problem affecting law and order.176

While Pawar was in custody, Circle Inspector Desmukh let him know that his custody was specifically related to his participation in protests against the Dabhol Power project. Pawar recalled for Human Rights Watch :

Desmukh asked me, “How do you feel, will you continue the agitation?” They wanted to see how strong I was mentally, since I had never been in jail. I told them that I would continue agitating, it is my birthright. I was put in a terrible cell with bad smells and filth. Desmukh said, “This is what it is like in jail and if I wanted to agitate, I must face these things.” I refused food and told them [the police] I was not a criminal and would begin a fast in the cell itself. After two or three hours, he assigned a constable to clean up the cell. He wouldn’t put me in a clean cell because he wanted to intimidate me. He would say, “You are a professor, you earn well, why do you want these headaches?”177

135 Human Rights Watch interview with Sadanand Pawar.

136 Prohibitory order issued against Medha Patkar and B.G. Kolse-Patil by T. Chandrasekhar, District Magistrate of Ratnagiri, March 1, 1997.

137 National Human Rights Commission of India, Enquiry Report-Alleged Human Rights Violation of Ms. Medha Patkar and Other Activists, July 1997, p. 17. This incident, to the knowledge of Human Rights Watch, is the only case related to the DPC project that has been investigated for human rights violations by any government agency.

140 V. Jayanth, “Joshi Finds The Going Tough in Singapore,” The Hindu, May 21, 1997.

141 Enquiry Report-Alleged Human Rights Violation..., p. 3.

142 Following this incident, Lata had to leave the Ratnagiri field office, due to her injuries and other physical ailments.

143 Human Rights Watch interview with Lata P.M., Bombay, January 28, 1998.

144 Enquiry Report-Alleged Human Rights Violation...,p. 3.

146 Prohibitory order issued to Medha Patkar by District Magistrate R.S. Rathod, May 28, 1998.

147 Enquiry Report-Alleged Human Rights Violation ..., pp. 3-4.

149 Human Rights Watch interview with Lata P.M.

150 Enquiry Report-Alleged Human Rights Violation ..., p. 5.

152 Human Rights Watch interview with Lata P.M.

154 Enquiry Report-Alleged Human Rights Violation..., p. 5.

157 Human Rights Watch interview with Lata P.M.

159 Enquiry Report-Alleged Human Rights Violation.., pp. 8-9.

161 Human Rights Watch interview with Lata P.M.

162 Enquiry Report-Alleged Human Rights Violation..., pp. 8-9.

163 Human Rights Watch interview with Lata P.M.

164 Enquiry Report-Alleged Human Rights Violation..., pp. 17-18.

167 For a detailed discussion of the National Human Rights Commission, see: Human Rights Watch, Police Abuse and Killings of Street Children in India, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1996), pp. 67-89.

168 Human Rights Watch interview with Dattaram Jangli, Borbatlewadi village, February 15, 1998.

170 Human Rights Watch interview with Mangesh Chavan. Chavan is a local activist from Ratnagiri who has documented all of the arrests, beatings, and detentions due to protests against the Dabhol Power project.

171 As noted above, Khare is known as a provider of legal assistance to arrested protesters.

172 A Circle Inspector is an inspector whose responsibilities extend to several districts.

173 Human Rights Watch interview with Mangesh Chavan.

175 Section 151 of the Code of Criminal Procedure states: “(1) A police officer knowing of a design to commit any cognizable offence may arrest, without orders from the Magistrate and without a warrant, the person so designing, if it appears to such officer that the commission of the offence cannot be otherwise prevented. (2) No person arrested under sub-section (1) shall be detained in custody for a period exceeding twenty-four hours from the time of his arrest unless further detention is required or authorised under any other provisions of this Code or of any other law for the time being in force.”

176 Judicial order of Sessions Judge V.G. Munshi, Ratnagiri Sessions Court, March 6, 1997.