- Arrests of Protesters

- Targeting of Protest Leaders

- Abuse of the Indian Penal Code

Key Individuals Named in this Report

I. Summary and Recommendations

II. Background: New Delhi and Bombay

III. Background to the Protests: Ratnagiri District

IV. Legal Restrictions Used to Suppress Opposition to the Dabhol Power Project

V. Ratnagiri: Violations of Human Rights 1997VII. Complicity: The Dabhol Power Corporation

VIII. Responsibility: Financing Institutions and the Government of the United States

Appendix A: Correspondence Between Human Rights Watch and the Export-Import Bank of the United States

Appendix B: Report of the Cabinet Sub-Committee to Review the Dabhol Power Project

Appendix D: Correspondence Between the Government of India and the World Bank

According to three Indian human rights organizations—the Center for Holistic Studies, the All India Peoples’ Resistance Forum (AIPRF), and the Committee to Protect Democratic Rights (CPDR)—120 protesters were arrested between January 13 and January 18, 1997. The protesters came from the villages of Anjanvel, Ranavi, and Veldur and had demonstrated at the DPC site in groups of twenty-five. They were released on personal bonds.

Three simultaneous demonstrations occurred on January 30, 1997: one in front of the Guhagar police station, a second in front of the home of a local Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA), and a third on the Guhagar-Chiplun road. Two of these demonstrations became disruptive; at one, stones were thrown by some protesters, and at the other, protesters inadvertently damaged police barricade while surging toward it.

· The protest at the Guhagar police station, involving more than 1,800 people, was dispersed by police after a barricade was broken. Police arrested approximately 450 of the participants and charged them with violating prohibitory orders and unlawful assembly under Section 37 of the Bombay Police Act.115

· In front of the MLA’s home, police did not arrest the demonstrators. Surendra Thatte, a recognized community leader and a candidate for the lower house of Parliament, participated in this rally. According to Thatte, police concentrated their attention on the third demonstration:

We were not arrested even though we staged a road roko [road block] with 400 people. But the people, almost 2,000 at the company gates, were arrested. They were singled out for teargassing and a lathicharge.116

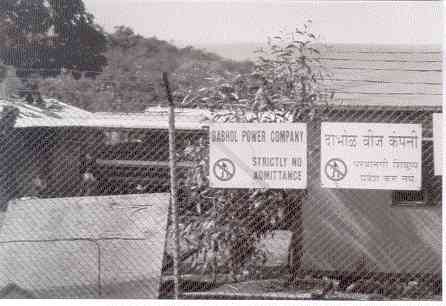

· About 1,500-2,000 protesters had marched from Guhagar village to the site of the Dabhol Power project. The protests largely consisted of shouting slogans and chants in front of the company gates. The police response was out of all proportion: protesters were beaten during a lathicharge, teargassed, and then arrested. Ms. Snehal Vaidya, head of the village council at Anjanvel, described the protest to an AIPRF fact-finding team led by retired Bombay High Court Justice S.M. Daud:

At 9:30 in the morning as we started out in a morcha [protest march], shouting slogans against Enron, MNC’s [multinational corporations], and the Alliance Government, the police tried to surround us and obstruct our progress. However, due to our massive numbers they were unsuccessful and we reached the site of the main demonstrations. Here, however, there was a huge police force deployed and even as we were peacefully shouting slogans, they began pushing and obstructing us... Suddenly, without warning, began a brutal lathicharge. Many of the constables were armed with freshly cut branches of trees, others with lathis, with which they indiscriminately beat up all those who had gathered.117

Ataman More, a local leader of protests from the fishing village of Veldur, described the actions of police when we interviewed him on February 14, 1998:

We were stopped at the [DPC] site. We told the police that we were peaceful demonstrators and we would go to a predetermined,preannounced site to hold our rally. If anything happens, the leaders will take responsibility for them. Despite our request, the police fired teargas shells and lathi-charged us at around 11:00 a.m. They were shooting teargas right into the crowd. Then the men and women police started beating people with lathis. I was hit with a lathi on my left thigh. People scattered and were running in all directions with the police chasing them. The ones caught by the police were dragged into police vans.118

Snehal Vaidya also noted that protesters were beaten and then held within the gates of the Dabhol Power Corporation by police. She told the AIPRF fact-finding team:

A number of aged men and women were not spared, including Arkatte, Mastan, Bangi (in their seventies) and eighty-three year old Chiplunkar. Totally seventeen women and five men were severely beaten. Ms. Parvati Saitavadekar, Bangi and the severely paralyzed Gurav, who were injured were pushed into the company compound and left without medical treatment for hours... [W]e were forcibly pushed into the police van, and minutes later, the police began firing tear-gas shells.119

According to the AIPRF fact-finding team, approximately forty canisters of teargas were fired and several rounds of ammunition were shot in the air. The police reportedly threw stones at fleeing protesters. In total, police arrested 679 people and charged them under Section 37 and Section 135 of the Bombay Police Act. The protesters were presented before the magistrate at Chiplun on January 30 and 31 and were released on personal bonds. Many of the cases, however, were still pending in October 1998.

On February 7, 1997, the DPC diverted water from the Aareygaon dam at the Modkagar reservoir. Villagers who received their water from the reservoir were forced to live with significantly diminished water supplies. In protest, approximately one hundred villagers, led by retired Bombay High Court Justice B.G. Kolse-Patil, staged a sit-in that blocked the pumps transporting water to theDabhol Power project. During the demonstration, a water pipe was broken by protesters.120

Twelve days later, on February 19, a pump operator at the dam restored the water supply to Enron, but villagers learned about the diversion of water and tried to stop him by blocking access to the pump. The operator filed a complaint with the police. Seven villagers were arrested on February 27 and one was arrested on March 15 for violating prohibitory orders under Section 37 and unlawful assembly under the Indian Penal Code.121 They were released on 1,000 rupees bail the day of their arrest.

In the village of Pawarsakhari, approximately 250 protesters held a road roko (road block protest) on February 21 to prevent two state cabinet ministers, Narayan Rane and Ravindra Rane, from going through the village because they supported the project. In response, a battalion of the State Reserve Police lathi-charged the protesters and arrested ninety-six people. They were charged with violating prohibitory orders under Section 37 and unlawful assembly under the Indian Penal Code.122

On April 28, 1997, approximately 150 members of the Samajwadi Jan Parishad (Socialist Peoples’ Conference) from four states—Bihar, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal—were arrested for protesting in front of the Dabhol Power project gates. They were charged with violating prohibitory orders under Section 37 and sentenced to nine days’ imprisonment.123

Two days later, fifty people were arrested for protesting in front of the site and for violating prohibitory orders under Section 37. They were sentenced to thirteen days’ imprisonment by the judicial magistrate at Chiplun.124

On May 4 and May 6, 1997, two peaceful demonstrations took place at the gates of the Dabhol Power project. Eleven people were arrested on May 4 and fifty individuals on May 6. All were arrested for violating prohibitory orders under Section 37 and were sentenced to fifteen days’ imprisonment.125

On May 15, 1997, Medha Patkar and approximately 178 other villagers were arrested for violating prohibitory orders by participating in a sit-in near the gates of the Dabhol Power project.126 Some of the demonstrators were beaten by police near the company’s gates. Following a judicial hearing, all were released the next day.127

Mahadev Satley, who is employed as an office assistant in Bombay but grew up in the village of Nagewadi in Ratnagiri district, participated in the May 15 demonstration. He told Human Rights Watch that once the protesters reached the plant gate, approximately 400 protesters put up banners, shouted slogans and stopped vehicles from entering the project site. The protest was completely peaceful from 8:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. Initially there were approximately ten police officers and two police vans, but when they saw the size of the crowd, police asked for reinforcements and three more vans. A larger contingent of approximately fifty police officers, made up of Maharashtra Police and the State Reserve Police Force (SRP), arrived at the gate.

According to Satley, Circle Inspector Desmukh, the police officer responsible for supervising police in several districts, was present at the demonstration and told the activists that they would be arrested. Satley said that the police started “manhandling people” and that at least fifteen people were beaten with lathis. About fifty people were placed in the vans.128

Medha Patkar, a nationally and internationally known environmental activist who participated in this demonstration, told Human Rights Watch:

After an hour, the police told us to go. We knew we were going to be arrested, so we held hands. They pulled me by the hair. The police molested many women, so they started yelling at the police which made the police more angry.129

Around 11:30 a.m., the protesters were taken in the vans to Guhagar police station. The police finished their paperwork by 2:00 p.m. The protesters were transported to Chiplun at around 5:30 pm and produced before the magistrate. Because the courts were closed for the day, they were held in custody overnight. The police wanted them to stay in the open, but they refused. Finally arrangementswere made to keep them at the community hall. There were no sanitary facilities, and they received food only at 1:30 a.m.

The next morning, they were produced before the court. People tried to tell the judge about the lack of facilities in custody, the bad food, the travel which created further hardship because of the costs of transportation, and the beatings at the time of arrest, but the judge would not listen. In protest, the demonstrators refused to pay bail or fines and were prepared to stay in jail. Four days were spent in jail at Chiplun, after which the group of about fifty was transferred to Yerewada jail, 400 kilometers away in the city of Pune. On May 20 they were released. Satley told Human Rights Watch:

There is a popular feeling that the Guhagar police act as employees of Enron and not guardians of law and order on behalf of the state. Not only the local police, but the local courts were colluding with Enron. Whatever the treatment we got from the time we were arrested was to please or appease Enron. The state, police, and courts were extremely harsh to show Enron that they were serious.130

A well-known politician with the Janata Dal, a major political party, Mrs. Mrinal Gore, led a road roko in Guhagar, along with thirty other protesters, on May 16, 1997. They were arrested by police and charged under Section 37 and Section 135 of the Bombay Police Act and wrongful restraint under the Indian Penal Code.131 They were remanded to magisterial custody (kept in custody in jails near the court) and released on May 31. Two of the female protesters were minors and were illegally kept in the Kalyan jail.132

On May 17, more than 300 demonstrators were protesting the Dabhol Power Corporation’s fencing of land around their farms. Police arrested and charged them under sections 37 and 135. Surendra Thatte, a participant in this demonstration, told Human Rights Watch:

I was involved in the May 17 demonstration. Our crime was taking part in an assembly of more than four persons. This happened around 11:00. We were arrested around two or three in the afternoon. At about five in the evening, we arrived at Chiplun and were taken before the magistrate. The magistrate said that we violated prohibitory orders and remandedus to fourteen days’ custody. Fifty women were sent to Kholapur. Sixteen men and fifty-four women were taken to Sangli, which is about four hours by bus. We were treated well in custody and kept away from undertrials and goondas [colloquial term for habitual criminals]. After fourteen days, we were brought to the magistrate and released.133

The same day, May 17, approximately 3,000 people from villages in the district gathered to demand that work be stopped at the Dabhol Power project site. Police did not arrest anyone at the gates. On June 3, however, the police filed a First Information Report charging 1,200 of those demonstrators under Section 37 of the Bombay Police Act. Their cases were still pending in October 1998.134

115 The protesters were charged under sections 37(1), 37(3), and 135 of the Bombay Police Act.

116 Human Rights Watch interview with Surendra Thatte, Guhagar, February 14, 1998. “Lathicharge” refers to a group of police forcibly dispersing a crowd by storming the crowd while beating them with police batons.

117 S.M. Daud, A. Gajbhiye, V. Karkhelikar, and Stephen Rego, “In the Service of a Multinational: How the Indian State Deals with Popular Resistance to Enron,” a fact-finding mission for the All India Peoples’ Resistance Forum (AIPRF), April 1997, Bombay, p. 13.

118 Human Rights Watch interview with Ataman More, Veldur village, February 14, 1998.

119 “In the Service of a Multinational...”, p. 13.

120 “Anti-Enron Agitations...,” pp. 2-3.

121 The protesters were charged under sections 37(1), 37(3), and 135 of the Bombay Police Act and Section 143 of the Indian Penal Code.

122 The protesters were charged under sections 37(1), 37(3), and 135 of the Bombay Police Act and Section 143 of the Indian Penal Code.

123 “Anti-Enron Agitations...,” pp. 3-4.

126 Ibid. National Alliance of Peoples’ Movements press release, May 16, 1997.

127 “Anti-Enron Agitations...,” pp. 3-4.

129 Human Rights Watch interview with Medha Patkar, Bombay, February 20, 1998.

130 Human Rights Watch interview with Mahadev Satley.

131 Section 341 of the Indian Penal Code.

132 “Anti-Enron Agitations...,” p. 7.

133 Human Rights Watch interview with Surendra Thatte.

134 Human Rights Watch interview with Mangesh Chavan, Bombay, February 4, 1998.