“You Will Be Punished”

Attacks on Civilians in Eastern Congo

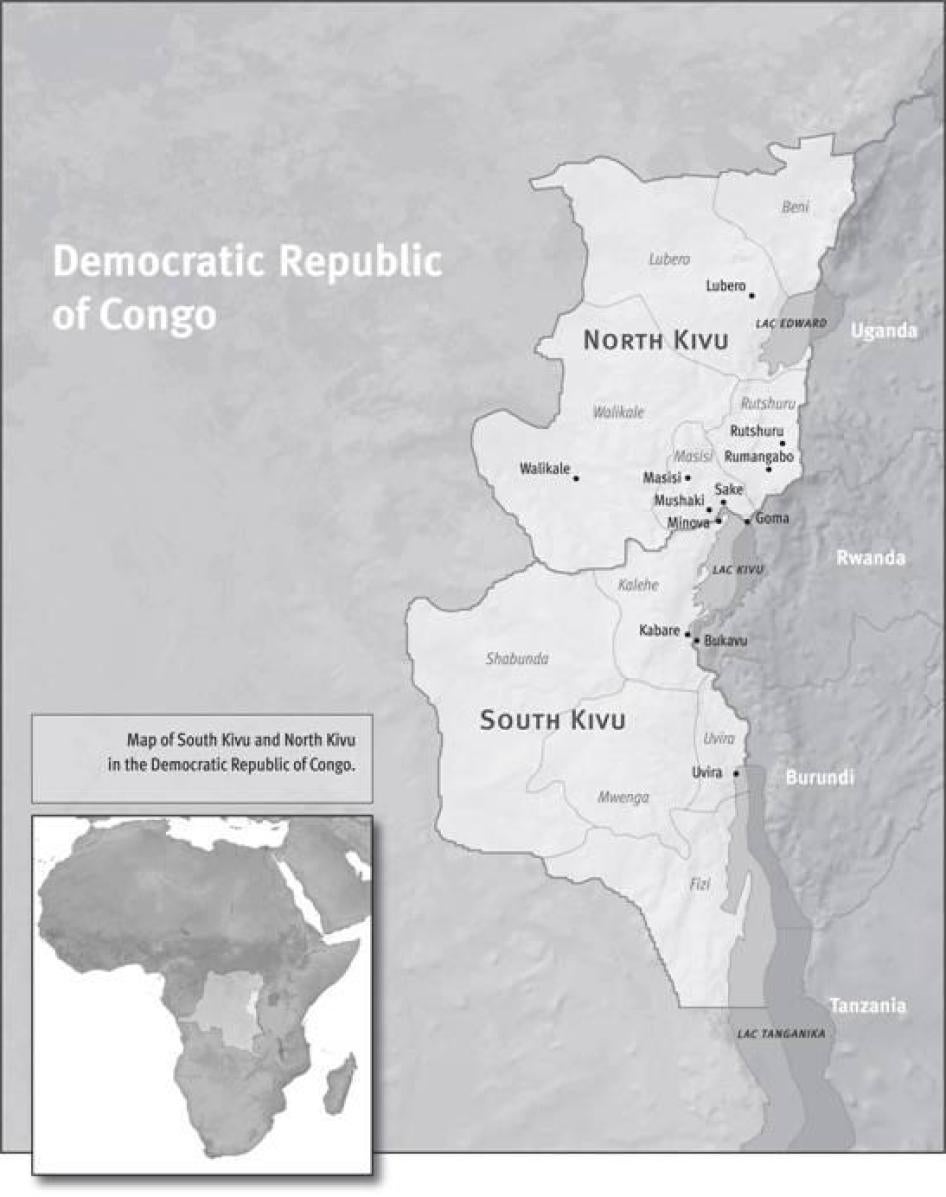

Maps

North and South Kivu

© 2009 Human Rights Watch

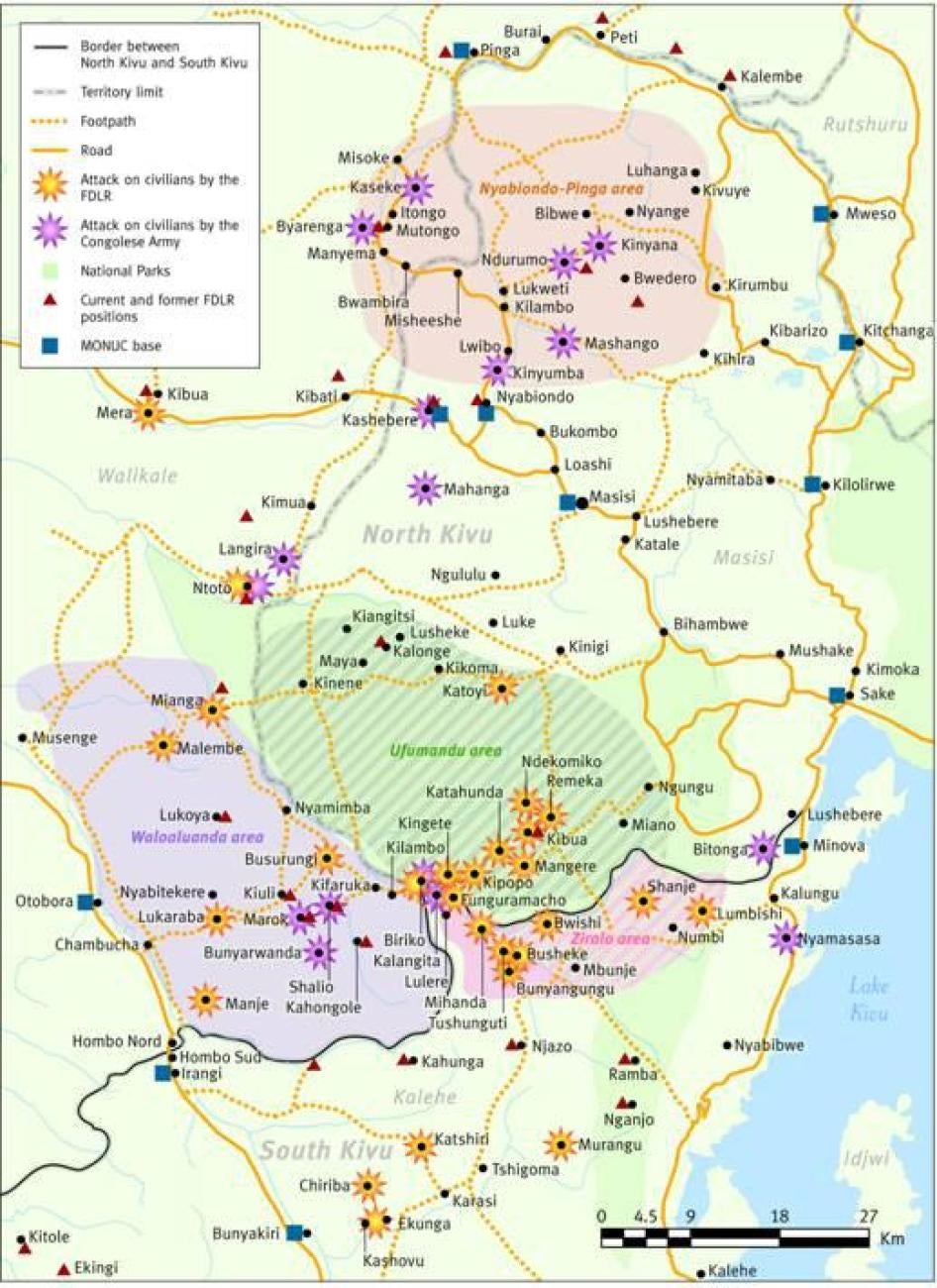

Attacks on Civilians in North and South Kivu*As documented by Human Rights Watch in this report

*This map marks attacks where at least 5 civilians were killed, 10 women were raped, or 50 homes burned in a single incident between January and September 2009. © 2009 John Emerson/Human Rights Watch |

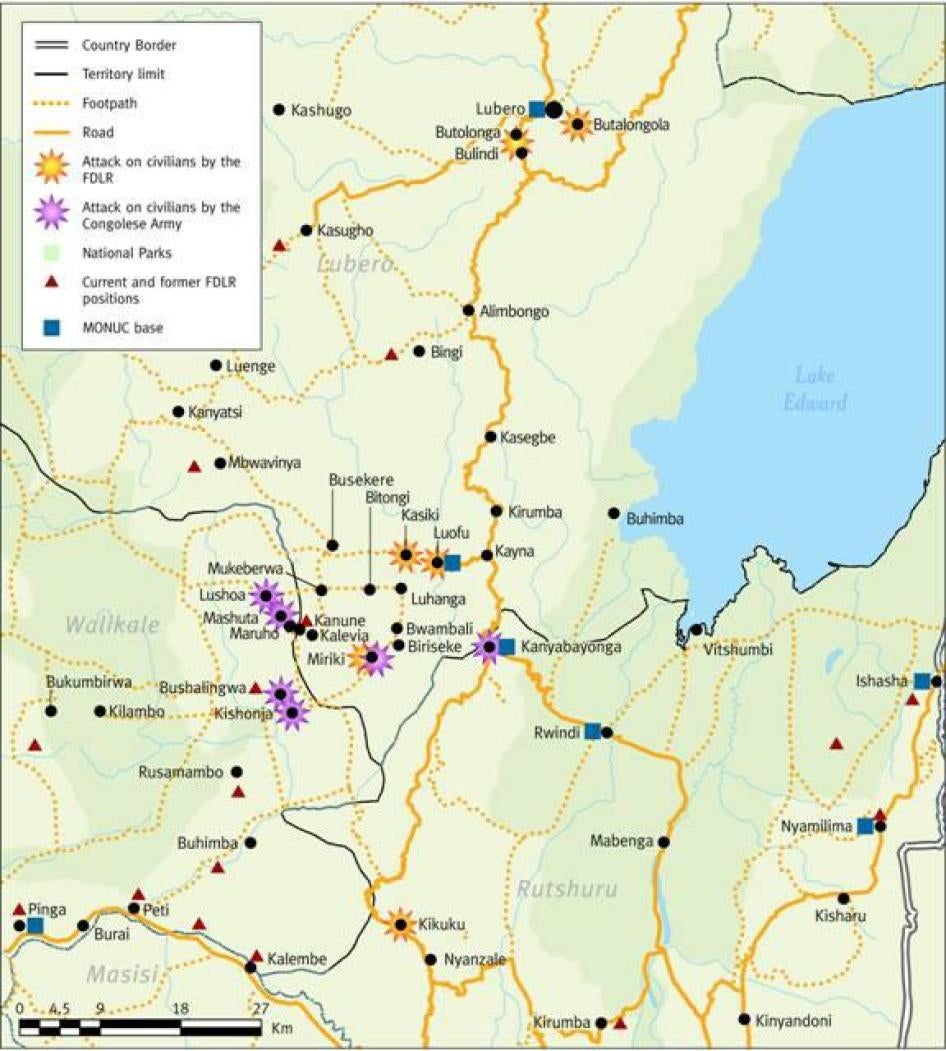

Attacks in the Lubero Area, North Kivu*As documented by Human Rights Watch in this report

*This map marks attacks where at least 5 civilians were killed, 10 women were raped, or 50 homes burned in a single incident between January and September 2009. © 2009 John Emerson/Human Rights Watch |

Summary

In January 2009, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda, following a dramatic shift in political alliances, launched joint military operations in eastern Congo against an abusive Rwandan Hutu militia, some of whose leaders had participated in the Rwandan genocide in 1994. The operations were intended to neutralize the group, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Les Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda, FDLR), which over the previous 15 years had preyed on Congolese civilians in the mountainous provinces of North and South Kivu.

Government representatives said the operations would bring peace and security to the region. They have not. Two successive Congolese military operations—one conducted with Rwandan military forces, known as operation Umoja Wetu, and the second conducted with the direct support of United Nations peacekeeping troops, known as operation Kimia II—have been accompanied by horrendous abuses by both government and rebel forces against a civilian population in eastern Congo that has long suffered so much.

The attacks against civilians have been vicious and widespread. Local populations have been accused of being “collaborators” by one side or the other and deliberately targeted, their attackers saying they are being “punished.” Human Rights Watch has documented the deliberate killing of more than 1,400 civilians between January and September 2009, the majority women, children, and the elderly. The attacks have been accompanied by rape. In a region already known as the “worst place in the world to be a woman or child,” the situation has deteriorated even further. Over the first nine months of 2009, over 7,500 cases of sexual violence against women and girls were registered at health centers across North and South Kivu, nearly double that of 2008, and likely only representing a fraction of the total.

In addition to killings and rapes, thousands of civilians have been abducted and pressed into forced labor to carry weapons, ammunition, or other baggage across the treacherous terrain by government forces and FDLR militia as they deploy from place to place. Some civilians have been killed when they refused. Others have died because the loads they have been forced to carry were too heavy. Between January and September, the attacks forced more than 900,000 people to flee for their lives, seeking safety in the remote forests, with host families, or in displacement camps. During the attacks or as they fled, FDLR combatants or Congolese army soldiers pillaged their belongings and then burned their homes and villages. Over 9,000 houses, schools, churches and other structures have been burned to the ground in North and South Kivu. Many civilians, already poor, have been left with nothing.

Civilians have been targeted by all sides: the FDLR, the Congolese army and, in some instances, the Rwandan army. Civilians look to the UN peacekeeping mission in Congo, MONUC, for desperately needed protection. MONUC has a strong mandate from the UN Security Council to protect civilians and to use force to do so, but it has become a partner of the Congolese army in the military operations, and it failed to put in place adequate measures for civilian protection before operations were launched. Peacekeepers have made notable efforts to protect civilians which undoubtedly have helped to save lives, but in many instances they have arrived too late or not at all, leaving local people exposed to attacks with nowhere else to turn.

The first military operation, Umoja Wetu (“0ur unity” in Swahili), began on January 20, 2009, following a secret agreement between Congolese President Joseph Kabila and his Rwandan counterpart, President Paul Kagame. It resulted in the removal of Congolese rebel leader Laurent Nkunda, whose armed group, the National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, or CNDP), had received substantial support from Rwanda and had defeated the Congolese army in successive battles in 2007 and 2008. Rwandan authorities detained Nkunda and promoted Bosco Ntaganda, the CNDP’s military chief of staff, to take his place. Ntaganda promptly agreed to integrate his troops into the Congolese army and to give up the CNDP’s rebellion.

In exchange for Rwanda’s assistance in removing the CNDP threat, President Kabila permitted Rwandan troops to return to eastern Congo and to conduct joint operations against the FDLR. Ntaganda, who has a track record of human rights abuses and is wanted on an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, was made a general in the Congolese army. An estimated 4,000 Rwandan troops, and possibly many more, then crossed the border into eastern Congo, where they stayed for 35 days.

Following the departure of Rwandan troops on February 25 at the end of operation Umoja Wetu, Rwandan and Congolese officials emphasized that the military operations were not complete. They pressed MONUC to join forces with the Congolese army to finish the FDLR. MONUC had been authorized by the UN Security Council to support and participate in military operations against the FDLR in December 2008, as long as such operations were conducted in accordance with the laws of war. But MONUC had been deliberately excluded from operation Umoja Wetu and many UN officials were deeply troubled at the turn of events that had returned Rwandan forces to Congolese soil. According to MONUC insiders, the MONUC leadership was worried about the consequences of being excluded from future military operations, concerned about a return of Rwandan troops if they did not step in, and confident civilians would be better protected were the peacekeepers to be part of military operations—so MONUC agreed to support the Congolese army.

In the rushed preparations that followed, MONUC officials did not set out clear conditions for their support, did not insist on the removal of known human rights abusers from the ranks of the Congolese army, and did not adequately prepare for the protection of the civilian population. On March 2, the Congolese army, with the direct support of MONUC peacekeepers, launched operation Kimia II (“quiet” in Swahili), an operation that continued at this writing.

Abuses by the FDLR

The FDLR responded to the offensive of the Congolese government, which had previously supported the group, by committing attacks against Congolese civilians. FDLR forces deliberately attacked civilians in whose communities they had lived, accusing their neighbors of “betrayal” and telling them that they would be “punished” for their government’s policy. The evidence of their brutal strategy was clear in letters from FDLR commanders, public meetings, oral threats to individuals, and written messages left on footpaths, many of which Human Rights Watch has collected. These messages and subsequent interviews with FDLR combatants who fled the group, demonstrate a deliberate tactic of retaliatory killings coming from a central FDLR command.

Human Rights Watch has documented previous attacks on civilians by FDLR combatants, but this time the killings and other abuses were significantly more numerous and widespread, and showed clear signs of being systematic. Between late January and September 2009, the FDLR deliberately killed at least 701 civilians in North and South Kivu. Many people were chopped to death by machete or hoe. Some were shot. Others were burned to death in their homes. The FDLR targeted and killed village chiefs and other influential community leaders, a tactic that spread fear throughout entire communities. In the worst single incident, the FDLR massacred at least 96 civilians in the village of Busurungi, in the Waloaluanda area, on May 9-10, 2009. Some of the victims were first tied up before the FDLR “slit their throats like chickens.” Others were deliberately locked in their homes that were then burned to the ground. Some of the victims knew their attackers by name.

The killing of civilians was invariably accompanied by rape. Most of the victims were gang-raped, some so viciously that they later bled to death from their injuries. Others were abducted to be sexual slaves. In over 30 cases documented by Human Rights Watch, victims told us that their FDLR attackers said that they were being raped to “punish” them.

Human Rights Watch’s field investigations found the FDLR forces to be responsible for numerous serious human rights abuses and violations of the laws of war. On November 17, 2009, the FDLR’s president, Ignace Murwanashyaka, and his deputy, Straton Musoni, were arrested in Germany by German judicial authorities for alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed between January 2008 and July 2009 by FDLR combatants under their command. They were also charged with belonging to a terrorist group. Other members of the FDLR’s political and military leadership, including the group’s military commander in eastern Congo, Gen. Sylvester Mudacumura, and the group’s executive secretary, Callixte Mbarushimana, based in Paris, France, should also be investigated for ordering alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity, or as a matter of command responsibility.

Abuses by the Congolese army and other forces

Congolese civilians received little or no protection from their government’s armed forces against the FDLR attacks. The Congolese army, initially in joint operations with the Rwandan army in operation Umoja Wetu, and later with the support of MONUC peacekeepers in operation Kimia II, also targeted civilians, especially those they claimed collaborated with the FDLR. Congolese forces violated their obligation under the laws of war to minimize harm to civilians. They failed to distinguish civilians from combatants and targeted the former, did not give effective advance warning of attack when circumstances permitted, and made no efforts to permit civilians caught up in the fighting to flee to safety. Most egregiously, they summarily executed hundreds of civilians under their effective control. Between January and September 2009, Human Rights Watch documented the deliberate killing of at least 732 civilians, including 143 Rwandan Hutu refugees, by Congolese army soldiers and their coalition partner (during Umoja Wetu, the Rwandan Defence Force (RDF)).

Human Rights Watch has documented the killing of 201 civilians during the Umoja Wetu phase of military operations, many in the area between Nyabiondo and Pinga, bordering Masisi and Walikale territories in North Kivu. In two of the worst attacks during this phase of operations, 90 civilians were massacred in late February in the remote village of Ndorumo and a further 40 civilians were killed in the village of Byarenga. The attacks were perpetrated by Rwandan and Congolese coalition forces, although witnesses found it difficult to distinguish between Rwandan army soldiers and former CNDP combatants newly integrated into the Congolese army, who wore similar uniforms and spoke the same language. In Ndorumo village, the coalition forces began killing civilians after they had been called to a gathering at the local school. One witness said the soldiers told the population they were “being punished for being complicit with the FDLR.”

The killings continued during operation Kimia II, often by newly integrated CNDP combatants. Human Rights Watch has documentedthe deliberate killing of a further 531 civilians between March and September 2009. The real figure is likely to be much higher—Human Rights Watch also received credible reports of an additional 476 civilians killed by Congolese army forces and their allies in the area between Nyabiondo and Pinga. However, due to the remoteness of the area, we have not been able to confirm whether they were caught in the crossfire or were deliberately killed, so these numbers have not been included in our calculations.

Congolese forces also targeted Rwandan Hutu refugees living in eastern Congo, whom they often accuse of being FDLR combatants or “wives.” From April 27 to 30, 2009, in the worst incident documented by Human Rights Watch, Congolese army soldiers deliberately killed at least 129 Rwandan Hutu refugees, mostly women and children, when they attacked the neighboring hills of Shalio, Marok, and Bunyarwanda in Walikale territory (North Kivu).While there were FDLR combatants deployed in these hills, all witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that the FDLR combatants had fled in advance of the attacks and were not present in any of the makeshift refugee camps targeted by the Congolese army.

At Shalio Hill, Congolese army soldiers killed at least 50 refugees as they tried to flee. After the attack, one group of soldiers took 50 refugees from Shalio to Biriko, where the soldiers beat them to death with wooden clubs and shot three refugees who tried to escape. Only one person survived. A second group of soldiers took 40 refugees, all women and girls, from Shalio to a nearby Congolese army position where they were kept as sexual slaves, gang-raped and mutilated by the soldiers. Ten of the women managed to escape, but the fate of the others is unknown. One who was later interviewed by Human Rights Watch bore the marks of her mutilation: her attackers had cut off chunks from her breast and stomach.

As with the FDLR, the killing by Congolese army soldiers was often accompanied by the rape of women and girls. In North Kivu, 268 out of 410 sexual violence cases documented by Human Rights Watch were perpetrated by government soldiers. In at least 15 cases, the women and girls were summarily executed after being raped, some by being shot in the vagina. Husbands, children and parents who desperately tried to stop the rape of their loved ones were also attacked. In cases documented by Human Rights Watch, at least 20 family members were killed when they cried out or otherwise protested against the rape.

The protection of civilians in Congo is primarily the responsibility of the Congolese government and its security forces. Yet Congolese government officials have failed to take adequate or effective steps to protect civilians in eastern Congo. Human Rights Watch found that Congolese army forces repeatedly violated international human rights and humanitarian law. Responsible commanders should be investigated for ordering alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity, or as a matter of command responsibility.

Congolese military planners, given the past practice of both the FDLR and the government’s own forces, should have foreseen the grave risks to the civilian population. Previous military operations in North Kivu in 2007 and 2008 had resulted in frequent FDLR retaliatory attacks against civilians and Congolese army abuses. But Congolese decision-makers gave little or no attention in planning the military operations to providing for the protection of the civilian population. The authorities integrated highly abusive militias into government forces, and failed to seriously address the deeply entrenched problem of impunity.

On July 5, 2009, following exposure of some abuses by its soldiers, the Congolese government announced a policy of “zero tolerance” for human rights violations and put commanders on notice that they would be held to account for the behavior of their troops. Four officers were later arrested for their involvement in sexual violence, but Gen. Bosco Ntaganda and other commanders implicated in serious human rights violations remain in operational command.

Results of the operations

The Congolese government’s goal in both operation Umoja Wetu and Kimia II was to neutralize the FDLR. The military operations have had some impact on disrupting the FDLR. During nine months of military operations, 1,087 FDLR combatants were repatriated to Rwanda by the UN’s Disarmament, Demobilization, Repatriation, Reintegration, and Resettlement (DDRRR) program, representing a significant increase compared to 2008.[1] The FDLR have also been cut off, at least temporarily, from access to some markets and other traditional economic supply routes. But the FDLR is also reportedly recruiting new combatants and continues to raise funds and obtain weapons and ammunition through its international networks. A UN Group of Experts in November 2009 reported that military operations against the FDLR had failed to dismantle the group’s political and military structures on the ground in eastern Congo. The FDLR’s ability to conduct attacks on civilians remains intact.

A comparison of the impact of military operations on the FDLR and the harm to civilians starkly conveys the suffering endured by the population. For every FDLR combatant that was repatriated to Rwanda during the first nine months of operations, at least one civilian was deliberately killed, seven women and girls raped, eight homes destroyed, and over 900 people forced to flee for their lives. These are incomplete figures covering the period January to September—and the military operations still continue.

Operation Kimia II has also not given sufficient attention to the protection of the Rwandan Hutu refugees, who have been isolated and preyed upon for years by all sides, nor to facilitating their return to Rwanda. The establishment of safe humanitarian corridors, protected by MONUC peacekeepers, could help to facilitate the repatriation of the refugees and reduce abuses against them, including by the FDLR, who rely on this community for filling its ranks and providing support.

The military operations are also likely to have a significant future impact on local political and economic dynamics in eastern Congo that might undermine sustainable peace and efforts to bring the rule of law to this troublesome region. Former CNDP commanders newly integrated into the Congolese army appear to be using the operations as cover to gain control over mineral-rich areas and to clear the land for the return of Congolese Tutsi refugees and for cattle being brought in from Rwanda. The perceived dominance and preferential treatment given to former CNDP commanders has already led a number of local militia groups, often called Mai Mai, to abandon army integration. Some have joined forces with the FDLR.

MONUC and civilian protection

MONUC has provided substantial support to operation Kimia II including logistical and operations support, and an estimated US$1 million worth of service support such as daily rations during each month of operations. MONUC disregarded crucial elements of formal legal advice given by the UN Office of Legal Affairs on January 13 and did not establish conditions for respecting international humanitarian law, as required by its mandate, before it began to support the operations. On November 1, after eight months of support to operation Kimia II, Alain Le Roy, the head of the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations announced during a visit to Congo that MONUC would suspend its support to the Congolese army’s 213th Brigade. MONUC’s own investigations had revealed army soldiers had killed at least 62 civilians in the Lukweti area, just north of Nyabiondo. At the time of writing, MONUC support was not suspended to any other army units despite credible information that gross human rights violations were occurring elsewhere and none of the commanders implicated in past serious human rights violations had been removed from involvement in Kimia II operations.

The MONUC leadership ignored the important role played by Bosco Ntaganda in operation Kimia II, where he was the de facto deputy commander. MONUC could not legally support an operation in which Ntaganda, wanted on an ICC arrest warrant for war crimes, played a part, as the UN’s legal office pointed out to the MONUC leadership in a legal note on April 1, 2009. But the MONUC leadership disregarded the mounting evidence of Ntaganda’s role, including copies of orders he had signed, minutes of Congolese army internal meetings, his presence at the Kimia II command center, and his frequent visits to the troops in the field. Instead MONUC hid behind false assurances from the Congolese government that Ntaganda was not a part of operation Kimia II. Other commanders who had a track record of serious human rights violations and were commanders in operation Kimia II were also not removed, despite concerns raised by MONUC staff about the presence of these commanders and the risk they posed for civilians.

On June 2, 2009, the UN Policy Committee, which includes the heads of all UN agencies, decided that MONUC should not participate in any form of joint operations with Congolese army units if there were a real risk of human rights violations. MONUC staff in Congo’s capital, Kinshasa, struggled, belatedly, to put in place a policy of conditionality for the mission’s support to operation Kimia II.

MONUC’s support of the Congolese armed forces, particularly after receiving credible reports of gross violations of human rights, raises serious concern that MONUC itself is implicated in these grave abuses. In conflict with its mandate, MONUC ’s continued backing of operation Kimia II has undermined its primary objective to protect civilians. Until there are clear, measurable, and actionable conditions in place to ensure operations with Congolese forces do not violate international humanitarian law, MONUC should immediately cease all support for operation Kimia II.

Proper investigations are needed into the serious abuses documented in this report, many of which amount to war crimes and could be crimes against humanity. In line with the UN Security Council’s commitment, as expressed in Resolution 1894 to advance and ensure protection of civilians, the council should urgently deploy a Civilian Protection Expert Group to eastern Congo to investigate the situation, including the measures taken by MONUC to implement its mandate to protect civilians, and to recommend concrete measures to improve civilian protection and end impunity for the serious crimes.

Methodology

This report is the result of extensive field research carried out from January through November 2009 in eastern Congo. It is based on information collected during 23 fact-finding missions to 30 different locations in North and South Kivu provinces where military operations have taken place, or where displaced people have fled to escape the violence. Four Human Rights Watch researchers were involved. Human Rights Watch conducted 689 interviews with witnesses, victims, their family members, and those who buried the dead, as well as an additional 300 interviews with local and provincial authorities, church officials, civil society representatives, health workers, former and current FDLR and Mai Mai combatants, their commanders, Congolese army officers and soldiers, MONUC military and civilian officials, representatives of other United Nations agencies, diplomats, and international nongovernmental (NGO) representatives in North and South Kivu. We have also conducted interviews with UN officials and foreign diplomats in Kinshasa, New York, Washington, DC, London, Paris, Brussels and Pretoria.

Human Rights Watch also met with and discussed many of the issues raised in this report with Congolese government authorities including President Joseph Kabila; the Vice Minister of Defense, Oscar Masamba Matebo; the Minister of Justice, Luzolo Bambi Lessa; and with Maj. Gen. Dieudonné Amuli Bahigwa, the military commander responsible for operation Kimia II and a number of his subordinates. In August 2009, Human Rights Watch also met with the FDLR head, Dr. Ignace Murwanashyaka, in Mannheim, Germany.

The research for this report greatly benefited from reporting by United Nations sources including internal UN documents and legal memos, reporting from the UN Group of Experts, the UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial executions, the UN’s DDRRR program and reporting by diplomats, other national and international human rights and humanitarian organizations, legal papers from judicial officials and other government documents.

This report documents killings and other abuses where witnesses were able to clearly identify the group or armed forces to which the assailants belonged. Cases where the perpetrator was not clear have not been included in this report. Our statistics on the numbers killed are based on eyewitness accounts, information from family members, and testimony from those who helped to bury the dead. We have made every effort to corroborate our findings and dismiss accounts that we did not find credible.

Many of those we interviewed were deeply traumatized by their experiences yet were desperate to tell their stories about what had happened to them. This report is, in part, a testimony to their immense courage and will for the truth to be known.

Recommendations

To the Congolese Government and Army

- Cease immediately all attacks on civilians. Urgently put into place measures and mechanisms to deter, prevent and punish violations of international humanitarian and human rights law by Congolese army soldiers.

- Develop with United Nations assistance a clear strategy for civilian protection, with specific attention to protecting women and girls.

- Develop with the UN and other international partners a comprehensive multi-pronged disarmament strategy for armed groups, including the FDLR (see below).

- Immediately establish safe humanitarian corridors, protected with MONUC peacekeepers where possible, to permit Rwandan refugees and FDLR dependents who wish to return to Rwanda to do so in safety and dignity.

- Take the following measures in response to the serious human rights violations committed by Congolese army soldiers and to implement the declared policy of “zero tolerance” of abuses:

- Conduct impartial and credible investigations into the serious violations of human rights and war crimes committed during operations Umoja Wetu and Kimia II. Discipline or prosecute as appropriate those responsible, regardless of rank or position.

- Suspend from operational command officers implicated in serious human rights or laws of war violations pending investigation, including Lt. Col. Innocent Zimurinda.

- Instruct judicial authorities to immediately arrest Gen. Bosco Ntaganda and to transfer him to the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court.

- Instruct judicial authorities to immediately re-arrest Col. Jean-Pierre Biyoyo, who was sentenced to five years in prison in March 2006 for child soldier recruitment but escaped from prison later that year.

- Introduce a vetting mechanism for the Congolese army to remove military officers implicated in serious human rights abuse, including those newly integrated from the CNDP and other armed groups.

- Strengthen the capacity of the military justice system by devoting greater resources for investigations.

- Establish a special chamber with Congolese and international judges and prosecutors within the Congolese justice system. The chamber’s mandate should be to prosecute serious violations of international humanitarian law, including sexual violence, and should include the capacity to investigate and prosecute senior military and civilian officials responsible for crimes, including as a matter of command responsibility.

- Increase cooperation with the UN’s DDRRR efforts to encourage FDLR and other foreign combatants to disarm voluntarily and return to Rwanda. Take all necessary measures to end immediately attacks, threats and intimidation by Congolese forces against DDRRR staff and their bases and to cooperate fully with their efforts.

- To discourage looting and other abuses, ensure all soldiers receive a regular and adequate salary. Create military barracks that provide a base for soldiers and their families.

To the FDLR Leadership

- Cease immediately all attacks on civilians. Take all necessary measures, including making public statements, to ensure that FDLR forces do not commit human rights abuses and violations of the laws of war.

- Carry out investigations into war crimes committed by FDLR forces and take appropriate disciplinary measures against any member of the FDLR, regardless of rank, found responsible.

- Stop blocking the return of Rwandan refugees to Rwanda. Support the establishment of safe humanitarian corridors to allow refugees to return home.

To the Rwandan Government

- Cooperate with Congolese and other judicial investigations into alleged violations of international human rights and humanitarian law committed by Rwandan armed forces during operation Umoja Wetu. Ensure that any commanders or soldiers found responsible are disciplined or prosecuted as appropriate, including as a matter of command responsibility.

- Publish an updated list of current FDLR combatants who are wanted on charges of genocide.

To the UN Mission in Congo (MONUC)

- Immediately cease all support to operation Kimia II until there are clear, measurable and actionable conditions in place to ensure the operation does not violate international humanitarian law and until all known commanders with a record of human rights abuses have been removed from any operational responsibilities. Make the conditions public.

- In cooperation with Congolese justice officials, arrest Bosco Ntaganda. Make his arrest a condition for future support to the Congolese army.

- Establish “protection support bases” in areas where civilians are most at risk. Deploy civilian and military teams to such bases, including protection specialists for a minimum of two months to build confidence with the local population and authorities. Use such bases to help state authorities reestablish security for the civilian population.

- Urgently develop a civilian protection plan with specific responsibilities for both civilian and military staff. Include critical elements of the protection plan in the memoranda of understanding between MONUC and troop contributing countries, in the rules of engagement, and in directives from the Force Commander. Regularly assess its effectiveness. Such a plan should include, but not be limited to:

- Ensuring that MONUC troops are deployed to areas that are designated as “must protect” within fourteen days, but that patrols are sent immediately.

- Ensuring that MONUC field base commanders are in regular communication with local authorities, traditional chiefs, and civil society and displaced person representatives in their area of responsibility, with special attention given to women’s groups and to identifying the risks to civilians and mitigating such risks.

- Ensuring that all MONUC field bases have sufficient interpreters available around the clock and seven days a week.

- Ensuring that MONUC peacekeepers carry out regular foot and vehicle patrols to the areas most at risk in their area of responsibility, as well as escorts to civilians, and women and girls in particular, who are traveling along potentially dangerous roads or paths to their fields, to the market or to collect firewood or water, and to displaced people either fleeing violence or returning to their village of origin along roads or paths where they may be at risk of attack.

- Ensuring the removal of all illegal roadblocks in their area of responsibility.

- Give priority to implementation of the comprehensive strategy to combat sexual violence, launched by MONUC in April 2009, and ensure it is integrated into MONUC’s protection strategy.

- Ensure that the DDRRR program has adequate human and other resources and the support needed from other components of MONUC to carry out its tasks, including sufficient radio transmitters, vehicles, access to MONUC helicopters, interpreters, and more resources devoted to information collection and intelligence gathering on FDLR movements, leadership structure, chain of command, financial support, and recruitment efforts.

To the UN Security Council, the UN Secretary-General, the European Union, the United States, and Other International Donors

- In line with UN Security Council Resolution 1894 to advance and ensure protection of civilians, urgently deploy a Civilian Protection Expert Group to eastern Congo to inquire into, and rapidly report on, civilian protection needs and challenges, including: (a) attacks against civilians, gender specific violence, and abuses against children by all parties in violation of international humanitarian law; (b) measures taken by MONUC to implement its mission-wide strategy on protection of civilians; and (c) the extent to which protection of civilians is sufficiently integrated into the Concept of Operations (CONOPS). The Civilian Protection Expert Group should recommend concrete measures to advance the protection of civilians, ensure unhindered humanitarian access and assistance, and end impunity for serious crimes in violation of international law.

- Ensure MONUC has the means to carry out its mandate, including the urgent deployment of additional peacekeepers authorized in November 2008, and the rapid response capabilities, helicopters, and intelligence gathering support the mission has requested to provide civilian protection.

- Develop a new and comprehensive approach for disarming armed groups, including the FDLR, that emphasizes protection of civilians, apprehending those wanted for crimes in violation of international law, a reformed disarmament and demobilization program, and options for temporary resettlement of combatants and their dependents within or outside of Congo, among other measures.

- Conduct in-country investigations on the participation of the FDLR leadership in Europe and elsewhere on the alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity documented in this report, with particular attention on Ignace Murwanashyaka, based in Germany and currently under arrest for his role in alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in eastern Congo, and Callixte Mbarushimana, based in France.

- Open up contact with the FDLR to explore options for temporary resettlement of FDLR combatants and their families within Congo or to a third country as agreed between the Rwandan and Congolese government in the Nairobi communiqué of November 2007.

- Implement changes to the memoranda of understanding (MOU) with troop contributing countries to permit greater flexibility and fewer limitations on the physical location of troop deployment, the number of field bases, and the structural requirements necessary before a temporary base is established.

- Ensure that MONUC peacekeepers receive appropriate training on civilian protection before being deployed.

- Ensure that there is a significant human rights component in current security sector reform programs, including the creation of a vetting mechanism.

- Support measures to strengthen the military justice system and to create a special chamber to prosecute serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in Congo, as described above.

- Separate the UN human rights section from MONUC’s peacekeeping mission, with a direct reporting line to OHCHR to ensure it has the ability to investigate and report independently, credibly, and effectively on human rights violations by all sides.

To UN High Commissioner for Refugees

- Encourage and provide assistance to the establishment of safe humanitarian corridors to facilitate the return of Rwandan refugees.

- Increase the number of re-groupment sites and sensitization efforts for the repatriation of Rwandan Hutu refugees living in more remote areas such as the region between Nyabiondo and Pinga.

To the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court

- As part of ongoing investigations in North and South Kivu, investigate the serious crimes committed by perpetrators from all sides since January 2009 including those documented in this report. Reopen investigations on alleged war crimes committed by Bosco Ntaganda to include serious crimes committed in both the Ituri District and the Kivu region such as those in the Shalio Hill area in April 2009, the massacre at Kiwanja in November 2008, and ethnic massacres in Ituri including those at Mongbwalu in November 2002, among others.

Key PlayersThe Congolese Armed Forces (Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo, FARDC): The Congolese national army, FARDC, created in 2003 has an estimated strength of 120,000 soldiers, many from former rebel groups who were incorporated following various peace deals. About half of the Congolese army is deployed in eastern Congo. Since 2006, the government has twice attempted to integrate the 6,000 strong rebel CNDP, but failed each time. In early 2009 a third attempt was made to incorporate the CNDP as well as other remaining rebel groups, a process known as “fast track accelerated integration.” Many who agreed to integrate, however, remained loyal to their former rebel commanders, raising serious doubts about the sustainability of the process. National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du people, CNDP): The CNDP is a Rwandan-backed rebel group launched in July 2006 by the renegade Tutsi general, Laurent Nkunda, to defend, protect, and ensure political representation for the several hundred thousand Congolese Tutsi living in eastern Congo, and some 44,000 Congolese refugees, most of them Tutsi, living in Rwanda. It is estimated to have some 6,000 combatants, including a significant number recruited in Rwanda; many of its officers are Tutsi. On January 5, 2009, Nkunda was ousted as leader by his military chief of staff, Bosco Ntaganda, and subsequently detained in Rwanda. Ntaganda, wanted on an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court, abandoned the three-year insurgency and integrated the CNDP’s troops into the government army. On April 26, 2009, the CNDP established itself as a political party. Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Les Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda, FDLR): The FDLR is a Hutu militia group based in eastern Congo, some of whose leaders participated in the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. It seeks to overthrow the government of Rwanda and promote greater political representation of Hutu. In late 2008, the FDLR was estimated to have at least 6,000 combatants, controlling large areas of North and South Kivu, including many key mining areas. The FDLR’s president and supreme commander is Ignace Murwanashyaka, based in Germany. He was arrested on November 17, 2009, on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The group’s military commander in eastern Congo is Gen. Sylvester Mudacumura. The Congolese government has often supported and shown general tolerance for the FDLR, until early 2009 when its policy changed and the government launched military operations against the group. Rally for Unity and Democracy (RUD)-Urunana: RUD-Urunana is a splinter group of the FDLR estimated at some 400 combatants based in North Kivu, made up largely of dissident FDLR combatants. It was created in 2004 by the United States-based former FDLR 1st vice-president, Jean-Marie Vianney Higiro. Other political leaders are in Europe and North America. Since the start of military operations against RUD and the FDLR in January 2009, the two groups have reunited militarily. Mai Mai militia: The Mai Mai militia groups are local defense groups often organized on an ethnic basis who have traditionally fought alongside the government army against “foreign invaders,” including the CNDP and other Rwandan-backed rebel groups. In 2009 there were over 22 Mai Mai groups, ranging greatly in size and effectiveness, in both North and South Kivu. Some joined the Congolese army as part of the rapid integration process, while others refused, angry at the perceived preferential treatment given to the CNDP and unwilling to join the army unless they were able to stay in their communities. The various Mai Mai groups are estimated to have some 8,000 to 12,000 combatants. Coalition of Congolese Patriotic Resistance (Coalition des patriotes résistants congolais, PARECO): PARECO is the largest of the Mai Mai groups, created in March 2007 by joining various other ethnic-based Mai Mai militias including from the Congolese Hutu, Hunde, and Nande ethnic groups. Throughout 2007 and 2008, PARECO collaborated closely with the FDLR and received substantial support from the Congolese army, especially in their battles against the CNDP. In 2009, many PARECO combatants, particularly the Hutu, joined the Congolese army and its military commander, Mugabu Baguma, was made a colonel. The Hunde and Nande commanders were not offered equivalent command positions and remained outside the integration process, along with the majority of the Hunde and Nande combatants Patriotic Alliance for a Free and Sovereign Congo (Alliance des patriotes pour un Congo libre et souverain, APCLS): The APCLS is a breakaway faction of PARECO. Created in April 2008, it is largely made up of ethnic Hunde and is led by General Janvier Buingo Karairi. It is based in the area to the north of Nyabiondo, in western Masisi, with its headquarters in Lukweti village and has an estimated 500 to 800combatants. The APCLS is allied with the FDLR and refuses to integrate into the Congolese army without guarantees that they will be deployed in their home region and that the newly integrated CNDP soldiers will leave. |

I. Background

Conflict in Eastern Congo

When the Democratic Republic of Congo held its first multiparty elections in over 40 years in June 2006, there was widespread optimism that the country would emerge out of years of brutal war. Congolese citizens in the densely populated provinces of North and South Kivu in eastern Congo on the border with Rwanda, an area deeply affected by two consecutive wars from 1996 to 1997 and again from 1998 to 2003, were desperate for peace. They voted overwhelmingly for presidential candidate Joseph Kabila, who promised to end conflict in this troublesome region. Yet in the three years following the elections, eastern Congo has remained locked in brutal conflict. In 2009 alone, botched peace attempts combined with badly organized and abusive military operations have led to nearly a million people fleeing their homes, hundreds massacred, and thousands more women and girls raped. As one resident of eastern Congo told Human Rights Watch, “We voted for peace, but all we got was more war. When are they going to stop killing us?”[2]

The ongoing conflict in eastern Congo has been marked by a constant shift in alliances between a confusing array of belligerents. One-time enemies turn into allies and back into enemies again in swift succession, confusing Congolese citizens and political analysts alike. In the three years since the elections, the Congolese government has failed to address the underlying causes of the conflict and to effectively extend state control to areas once occupied by the Rwandan army and its proxy forces. Instead the government has sought secret deals with various rebel groups and, when unsuccessful, used military force. To date, neither course of action has brought peace or security to the area.

Two armed rebel groups have dominated recent events in eastern Congo: a Rwandan Hutu militia called the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Les Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda, FDLR), and the Congolese Tutsi-led National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP). At different times, both groups have been either allies or enemies of the Congolese government depending on its relationship with Rwanda. The difficulty in finding lasting solutions to the crisis is exacerbated by the struggle for control of one of the richest regions in Congo.

The ongoing conflict in eastern Congo is also linked to the after-effects of the Rwandan genocide in 1994 and can only be understood by looking at political dynamics in both Congo and Rwanda. In Rwanda, growing restrictions on political space have promoted views among some Hutu, including those in the FDLR, that they have little or no say in Rwandan political life and that the Hutu population are being collectively punished for the genocide. Political parties that oppose President Paul Kagame are blocked from operating freely and the media faces severe restrictions on political reporting.

The Rwandan government often accuses its critics of “divisionism” or “genocide ideology,” vaguely defined offenses to punish the spreading of ideas that encourage ethnic animosity between the country's Tutsi and Hutu populations and the expression of any ideas that could lead to genocide.[3] Largely aimed at the Hutu population, such offenses permit, among other measures, the government to send away children of any age to rehabilitation centers for up to one year—including for the teasing of classmates—and for parents and teachers to face sentences of 15 to 25 years for the child’s conduct. The government has repeatedly accused the Voice of America, the British Broadcasting Corporation and other media outlets, as well as Human Rights Watch, of promoting genocide ideology; accusations these organizations deny.[4]

The tight control over political space, civil society and the media has forced a number of moderate Hutu and some Tutsi to leave Rwanda. Critics of the Rwandan government, including many Congolese civil society groups and the Congolese government, repeatedly call for an inter-Rwandan dialogue to ease the tension between Hutu and Tutsi in Rwanda. Congolese civil society groups claim that the failure to open political space in Rwanda is one of the underlying reasons for the continued suffering in eastern Congo. A European diplomat who agreed with this analysis said to Human Rights Watch, “The FDLR problem will not be solved if there is no political space for Hutu in Rwanda.”[5]

Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR)

The FDLR are a predominately Rwandan Hutu armed group that uses military force to seek political change and greater representation for Hutu in Rwanda.[6] Some of the FDLR leaders are believed to have participated in the genocide in Rwanda in 1994 and the group has important ideological links to the former Hutu Power movement.[7] In the years since the genocide, the Rwandan Hutu militia reorganized politically and militarily, going through various name and leadership changes.[8] In 2000 the current configuration, the FDLR, was created. As of January 2009, the group was estimated to have some 6,000 combatants in eastern Congo.[9] The vast majority of these combatants did not participate in the genocide since they were too young at the time to have played a role.[10]

The Congolese government has repeatedly turned to the FDLR (and its predecessor movements) for support in its fight against Congolese rebel groups backed by Rwanda and against the Rwandan army. In the 1998-2003 war, the well-trained Rwandan Hutu militias soon became some of the most important frontline troops for the then Congolese national government of Laurent Désiré Kabila, fighting alongside the Congolese army and its other allies throughout the war.[11]

Following the signing of a peace agreement ending the war, a transitional government was launched in Kinshasa in June 2003, led by Laurent Kabila’s son, Joseph. As part of the agreement, the Congolese government was nominally committed to disbanding the FDLR and facilitating its members’ return to Rwanda. Some minimal attempts were made to do so, but the effort was half-hearted and unsuccessful. With no outright war to fight and support from Kinshasa less frequent than before, the FDLR sought other sources of revenue. It turned to the illegal trade in mineral resources and control over other economic activities. In December 2008, the UN Group of Experts investigating arms trafficking estimated the FDLR’s economic activities brought them millions of dollars a year, including from the trade in minerals.[12]

In 2006, the Kinshasa government again turned to the FDLR for military support when a new Tutsi-led rebel group, the CNDP, emerged in North Kivu (see below). From late 2007 through 2008, the Congolese government continued to support, arm, and collaborate extensively with the FDLR.[13] In December 2008, the UN Group of Experts provided detailed evidence of this collaboration and support, including specific examples in which the FDLR cohabited with the Congolese army and supported the Congolese army in operations against the CNDP.[14]

National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP)

To deal with the continued threat of Rwandan Hutu militias across its border and to exercise influence in the fertile and mineral-rich North and South Kivu provinces, the Rwandan government has repeatedly backed Congolese rebel groups willing to fight the Hutu militias. Since 1996, Rwanda has backed three different Congolese rebel groups (and sometimes other splinter factions) who agreed to fight the Rwandan Hutu militias, but who also all sought to overthrow the government in Kinshasa.[15] The most recent Rwandan-backed rebel group is the CNDP, which until January 2009 was led by a former Congolese Tutsi general, Laurent Nkunda.

While the degree of military and political support for each of these groups has varied, Rwanda’s policy of continued support and influence over Congolese proxy groups willing to fight the Rwandan Hutu militias and enhance its influence in eastern Congo has been unmistakable.

Nkunda’s CNDP emerged during Congo’s historic national elections in 2006, when it became clear that Tutsi political clout was about to rapidly diminish. In the aftermath of the dramatic electoral defeat of RCD-Goma, the former Rwandan-backed rebel group that had become a political party, Nkunda presented himself as spokesman for and protector of Congolese Tutsi. His program, he said, was to eliminate the FDLR, prevent the exclusion of Tutsi from national political life, assure the security of Tutsi soldiers in the national army, and bring about the return of some 45,000 Congolese Tutsi refugees living in camps in Rwanda.[16] Some Tutsi leaders, fearful of losing economic gains made during the war years and an ethnic backlash against them, insisted that Nkunda’s troops constituted their last bulwark of protection.[17]

From 2006 through 2008, Nkunda’s CNDP cemented and expanded their area of control in Masisi and Rutshuru territories (North Kivu), where they created what one of Nkunda’s officers called “our little state” with their own local administrators and an extensive taxation system that brought in hundreds of thousands of dollars.[18] Nkunda’s CNDP also collected significant sums of money through voluntary donations from the Congolese Tutsi diaspora and businessmen in Goma, sent to bank accounts controlled by CNDP agents in Rwanda.[19]

Support and recruitment in Rwanda

Nkunda was joined by hundreds of former RCD-Goma troops and new recruits, including Hutu, Tutsi, and other ethnic groups, although the vast majority of the senior military officers were Tutsi. Nkunda also actively recruited combatants in Rwanda. Between 2006 and 2008, hundreds joined the CNDP’s ranks, including from the refugee camps in Rwanda, former demobilized Rwandan soldiers, and active Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) soldiers, some of whom were on “temporary” leave from their army.[20] Many joined voluntarily, but others were forcibly recruited or joined after false promises of jobs; some were children. By late 2008, the CNDP were estimated to have between 4,000 and 7,000 troops.[21]

The number of Rwandan citizens recruited into the CNDP remains unknown, but an indication of the scale can be deduced from the UN’s Disarmament, Demobilization, Repatriation, Reintegration, and Resettlement (DDRRR) program, which is tasked with facilitating the return of foreign combatants. Between January and October 2009, DDRRR staff had repatriated 448 former CNDP combatants to Rwanda, including 83 children (see below).[22]

The full extent of Rwanda’s support for Nkunda’s CNDP was evident in the December 2008 report of the UN Group of Experts monitoring arms trafficking in Congo. The report provided detailed evidence of Rwanda’s ongoing support for the CNDP, including evidence that Rwandan authorities “had been complicit in the recruitment of soldiers, including children, facilitated the supply of military equipment, and sent officers and units from the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in support of the CNDP.”[23] The report also provided specific evidence of Rwandan army support to a CNDP offensive against the Congolese army on October 26-30,[24] and showed how Rwanda has served as a rear base for the CNDP’s financial and communications networks.[25]

Clashes and the Failure of Mixage

Nkunda’s CNDP posed a significant problem for Kabila’s new government. Kabila’s election success had largely come from eastern Congo, where the population voted overwhelmingly for him on the basis that he promised to bring peace. In August and November 2006, Nkunda’s forces fought against the Congolese national army, producing substantial losses for both sides but no clear victor. In an effort to avoid further military operations, President Kabila in December 2006 dispatched Gen. John Numbi, the then head of the air force, to secretly negotiate a deal with Nkunda. The two sides met in Rwanda in January 2007 in talks facilitated by the chief of staff of the Rwandan army, Gen. James Kabarebe, where an agreement was reached. Nkunda accepted a limited form of integration of his CNDP troops into the ranks of the Congolese army, called mixage. In return the government agreed to deploy these troops in the Kivu provinces to conduct military operations against the FDLR. Nkunda gave a vague commitment to leave Congo temporarily for South Africa, a point that was later much disputed by both sides.

The deal failed. The integration did not work, and instead of bringing much needed security to North Kivu, the deployment of the mixed brigades led to a further deterioration of the security and human rights situation. Nkunda-affiliated units killed, raped, and otherwise attacked Congolese civilians to punish them for supposedly collaborating with the FDLR. For their part, the Congolese army units of the mixedbrigades loyal to Kinshasa showed little willingness to fight the FDLR. By August 2007 the two sides were once again on opposite sides of the frontline and fighting resumed.

In October and November 2007, diplomatic efforts led by the United States and the European Union to broker a ceasefire between the government and Nkunda’s CNDP rebels failed, with both sides blaming the other for the failure of mixage. In December 2007, the Congolese army launched a major offensive against the CNDP in Masisi, with logistical support from MONUC peacekeepers. The offensive failed. Government forces were defeated and soldiers deserted the battlefield in the thousands. Holding a strong military position, Nkunda again called for peace talks.

More Peace Talks Fail Again

In late 2007 and early 2008 two important agreements were struck, which diplomats hoped would end the conflict in eastern Congo. The first was signed on November 9, 2007, in Nairobi, Kenya, and was known as the “Nairobi Communiqué.” The agreement between the Congolese and Rwandan governments stipulated that the Congolese government would stop all support to the FDLR and would undertake military operations against the group if its members refused to return voluntarily to Rwanda. The Rwandan government agreed to block any support for armed groups in eastern Congo coming from its territory, including to the CNDP.[26]

The second agreement, known in English as the “Goma Agreement” (Acte d’Engagement in French), was signed on January 23, 2008, following three weeks of intense peace discussions in Goma, North Kivu, between the Congolese government and 22 armed groups, the most important of which was the CNDP. It committed all parties to an immediate ceasefire, disengagement of forces from frontline positions and integration of troops into the Congolese army. The agreement also established a separate commission[27] to provide a forum for negotiations of the armed groups’ political demands, particularly those of the CNDP, to be facilitated by foreign diplomats.

Following these talks, the government launched a peace program for eastern Congo, known as the Amani Program, or “Peace Program” in Swahili. It quickly became clear that the Amani Program sought to minimize the role of the new commission established by the Goma Agreement, which Nkunda’s CNDP rebels saw as a crucial forum to negotiate their political demands. Despite efforts by international representatives to move the process forward, by July 2008 the Goma Agreement had collapsed.

Applicable Legal Standards

International humanitarian law (the laws of war) is binding on all parties to an armed conflict, including non-state armed groups such as the FDLR. Applicable international humanitarian law in Congo includes article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, the Second Additional Protocol of 1977 (Protocol II) to the Geneva Conventions, and customary international humanitarian law.

International humanitarian law requires the humane treatment of civilians and captured combatants, prohibits violence to life and person, including murder, torture and other mistreatment, the taking of hostages, collective punishment, and outrages upon personal dignity. It prohibits rape and other forms of sexual violence.

International humanitarian law also regulates the methods and means of armed conflict. A fundamental principle is that all parties to a conflict must distinguish between combatants and civilians, and may not deliberately attack civilians or civilian objects. Acts or threats of violence whose primary purpose is to spread terror among the civilian population is prohibited.

Individuals who willfully commit serious violations of the laws of war, that is deliberately or recklessly, are responsible for war crimes. This includes those who participate in or order war crimes, or are culpable as a matter of command responsibility. States have an obligation to investigate alleged war crimes committed on their territory.

Serious offenses, including murder, torture and rape, deliberately committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against any civilian population are crimes against humanity.

Congo is party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), which may exercise jurisdiction for “the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole,”[28] specifically genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. In March 2004, the Congolese government referred the situation in the country to the ICC,[29] inviting the ICC prosecutor to investigate crimes within the jurisdiction of the Rome Statute on its territory. In June 2004 the ICC prosecutor announced the opening of an investigation in the Congo,[30]initially focused on Ituri, northeastern Congo, and in November 2008 announced the investigations were being expanded to include the Kivu provinces of eastern Congo.[31] The crimes committed by FDLR forces, the Congolese army and its allies, documented in this report, are subject to ICC jurisdiction.

Individual responsibility

Under international law, individuals are criminally liable for the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity. This includes attempting to commit such a crime, as well as assisting in, facilitating, and aiding and abetting an offense. Commanders and other superiors are criminally responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed or attempted pursuant to their orders.Finally, commanders and other superiors may be criminally liable as a matter of command responsibility for crimes committed by their subordinates if they knew, or had reason to know, of such crimes and failed to prevent the crimes or to punish those responsible.

Command responsibility as a basis of liability for crimes in violation of international law is well-established. The doctrine is provided in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court,[32] ad hoc international courts,[33] and customary international law.[34] It applies both to military commanders and to civilians in leadership roles, and during internal as well as international armed conflicts.[35]

Under article 28 of the Rome Statute, a superior shall be criminally responsible for crimes within the jurisdiction of the court, committed by subordinates under the superior’s effective authority and control, as a result of his or her failure to exercise control properly over such subordinates, where:

(i) The superior either knew, or consciously disregarded information which clearly indicated, that the subordinates were committing or about to commit such crimes;

(ii) The crimes concerned activities that were within the effective responsibility and control of the superior; and

(iii) The superior failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures within his or her power to prevent or repress their commission or to submit the matter to the competent authorities for investigation and prosecution.

The concept of crimes against humanity has been incorporated into a number of international treaties and the statutes of international criminal tribunals, including the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.The definition of crimes against humanity has been defined as a range of serious human rights abuses committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack by a government or organization against a civilian population.[36]Murder, rape, and other inhumane acts intentionally causing great suffering all fall within the range of acts that can qualify as crimes against humanity.[37]

Crimes against humanity include only abuses that take place as part of an attack against a civilian population. So long as the targeted population is of a predominantly civilian nature, the presence of some combatants does not alter its classification as a “civilian population” as a matter of law.[38]Rather, it is necessary only that the civilian population be the primary object of the attack.[39]

The attack against a civilian population underlying the commission of crimes against humanity must be widespread or systematic. It need not be both.[40]“Widespread” refers to the scale of the acts or number of victims.[41] A “systematic” attack indicates “a pattern or methodical plan.”[42]International courts have considered to what extent a systematic attack requires a policy or plan. For instance, such a plan need not be adopted formally as a policy of the state.[43]

Lastly, for individuals to be found culpable for crimes against humanity requires their having the relevant knowledge of the crime.[44]That is, perpetrators must be aware that their actions formed part of the widespread or systematic attack against the civilian population.[45]While perpetrators need not be identified with a policy or plan underlying crimes against humanity, they must at least have knowingly taken the risk of participating in the policy or plan.[46] Individuals accused of crimes against humanity cannot avail themselves of the defense of following superior orders nor benefit from statutes of limitation. Because crimes against humanity are considered crimes of universal jurisdiction, all states are responsible for bringing to justice those who commit crimes against humanity. There is an emerging trend in international jurisprudence and standard setting that persons responsible for crimes against humanity, as well as other serious violations of human rights, should not be granted amnesty.

II. Lead-Up to Military Operations

Crisis Point

In August 2008, the Congolese army launched a military offensive against the CNDP. Despite their superior numbers, the government forces quickly lost ground. In September 2008, Nkunda held a conference with CNDP members to review the group’s political position. The CNDP decided to demand direct bilateral talks with the government and to broaden their demands to include the removal of President Kabila from power.[47] On October 8, 2008, the rebels unexpectedly attacked and captured Rumangabo military camp, one of the most important military bases in eastern Congo, and seized a large stock of weapons and ammunition. Then, on October 26, the CNDP launched a major military offensive, rapidly overrunning Congolese army positions in quick succession. Military support from UN peacekeepers to the Congolese army was not enough to halt the advance and on October 29, 2008, Nkunda’s rebels approached Goma, causing widespread panic. The Congolese army disintegrated, its soldiers looting, raping, and killing as they fled.[48] UN peacekeepers remained as the only credible military force to protect Goma and its 500,000 inhabitants.

A diplomatic flurry ensued. US, European and other governments quickly urged Rwandan President Kagame to intervene and use his influence with Nkunda to halt the CNDP advance. Kagame protested that Nkunda’s rebels were acting of their own accord and not on Rwanda’s orders, but he nevertheless intervened. Nkunda called a halt to the advance and demanded face-to-face peace talks with Kabila’s government.

To resolve the crisis, diplomats called an emergency summit. International and regional leaders, including Presidents Kagame and Kabila, and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon met in Nairobi on November 7, 2008. The UN and African Union (AU) agreed to appoint special envoys to help mediate a solution: the UN appointed former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo and the AU appointed former Tanzanian president Benjamin Mkapa. The two former presidents immediately began their shuttle diplomacy and in the weeks that followed met separately with both President Kabila and Laurent Nkunda. In early December both sides agreed to send negotiating teams to Nairobi to begin direct talks. Nkunda’s CNDP brought an extensive list of demands to the table.

Meanwhile, Kabila attempted to shore up his defeated army. He sought military support from his former allies in the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), but no member state was willing to send troops. The UN Security Council on November 20, 2008, authorized 3,000 additional troops for MONUC,[49] but it soon became clear that the new troops would take months to arrive. Fearful that Nkunda’s CNDP rebels would march on Goma should talks fail once again, and aware that the Congolese army was in tatters, Secretary-General Ban on December 4, 2009, requested the EU to urgently deploy a short-term bridging force to Goma to help fill the gap until UN troops could arrive.But the EU declined to help.[50]

Unable to find military support to back up his beleaguered army, faced with a superior CNDP force, and engaged in talks in which the Congolese government was in a weak position, Kabila turned to Rwanda for help. As one diplomat told Human Rights Watch, Kabila’s “back was up against the wall.”[51]

Rwanda-Congo Deal

Rwanda too faced difficulties following the CNDP’s advance on Goma. Rwandan President Paul Kagame had started to feel the political costs associated with his support for Nkunda’s CNDP. The December 12, 2008 publication of the UN Group of Experts report, which had been made available to governments a month earlier, detailed evidence of Rwanda’s support for the CNDP and led Sweden and the Netherlands to withdraw nearly US$20 million in aid to Rwanda in protest.[52] In addition, officials in Rwanda had found it difficult to control the increasingly headstrong Nkunda. The CNDP’s announcement that its goals were national and included the removal of Kabila was not well received in Kigali.[53]

On December 5, 2008, the Congolese minister of foreign affairs, Alexis Thambwe Mwamba, and his Rwandan counterpart, Rosemary Museminali, announced the upcoming joint military operation against the FDLR, named Umoja Wetu.[54] For several weeks, bilateral talks continued in secret. Like previous negotiation attempts, the key players included Rwandan General James Kabarebe and Congolese General John Numbi.

In January 2009 the plan was put into operation. On January 5, Bosco Ntaganda, Nkunda’s military chief of staff, announced he was removing Nkunda as leader of the CNDP for hindering peace in eastern Congo.[55] Ntaganda was being sought on an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court for war crimes committed in Ituri, northeastern Congo, between 2002 and 2004. According to CNDP insiders interviewed by Human Rights Watch, Ntaganda had had many rifts with Nkunda since he joined the CNDP movement in 2006, which may, in part, explain his decision to head the “putsch” against Nkunda.[56] He was also likely urged on by Rwandan officials who knew Ntaganda well (he had served in the Rwandan army) and who sought to exploit the divisions between the two men for their own purposes.

Shortly after announcing Nkunda’s removal, Ntaganda’s spokesperson announced that the CNDP delegation in Nairobi no longer had the authority to negotiate at the peace talks on behalf of the CNDP.[57] Ten senior CNDP officers, under immense pressure from General Kabarebe, joined Ntaganda’s putsch and signed a declaration of the cessation of hostilities on January 16, which stated that the CNDP would integrate into the Congolese army to disarm the FDLR through joint Rwandan and Congolese military operations.[58] The declaration was read aloud by Ntaganda, flanked by Generals Kabarebe and Numbi, and the Congolese minister of the interior, Célestin Mbuyu, at a hastily organized press conference in Goma the same day. Seeing support ebbing away, Nkunda responded to a request from General Kabarebe to come to Gisenyi, Rwanda, for consultations. On his arrival the next day, Rwandan authorities promptly detained Nkunda and placed him under house arrest. Ntaganda was made a general in the Congolese army.

Later on March 23, a new CNDP negotiating delegation signed a political agreement with the Congolese government, which provided its troops with amnesty for acts of war and insurgency (but not for war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide), release of political prisoners, and political participation in Congo’s government.[59]

Joint Military Operations

Umoja Wetu

On January 20, at least 4,000 Rwandan troops, and possibly many more, crossed the border into eastern Congo to fight the FDLR in a joint Rwandan-Congolese offensive named operation Umoja Wetu (“Our Unity” in Swahili).[60] Although a joint offensive in name, many Congolese troops were distracted by the complicated integration of former combatants from the CNDP, and other armed groups into their ranks and were largely absent from the operation. Concerned about negative public opinion from having concluded a deal in which Rwandan troops were invited into Congo, Kabila’s government at first maintained that the Rwandan soldiers present in Congo were only military advisors[61] to the joint operations and would not stay long. Then in a televised statement on January 31, President Kabila extended the invitation declaring that the joint operation would be finished by the end of February 2009, without making any mention of the extent of Rwanda’s military involvement.[62]

Rwandan troops quickly forged ahead, sometimes together with former CNDP troops, attacking one of the main FDLR bases at Kibua, in Masisi territory (North Kivu), and other FDLR positions around Nyamilima, Nyabiondo, Pinga and Ntoto (North Kivu). While there were some military confrontations, mostly notably in the area around Nyabiondo and Pinga, FDLR combatants often retreated into the surrounding hills and forests in advance of the attacks.

After 35 days of military operations in North Kivu, and in what was likely an agreed timeframe between Presidents Kabila and Kagame, the Rwandan army withdrew from Congo on February 25. A goodbye ceremony and military parade in Goma were attended by the Rwandan and Congolese foreign and defense ministers, the head of MONUC, Alan Doss, and diplomats from Kinshasa and Kigali. General Numbi, one of the key architects of the deal, announced that the operation had been a success.[63]

Kimia II

Government representatives from both Rwanda and Congo emphasized that the mission was not complete and pressed MONUC to join forces with the Congolese army to finish off the FDLR problem in North and South Kivu. In meetings following the Rwandan army’s departure, government officials from both countries raised similar expectations in private.[64] MONUC, which had deliberately been kept out of the planning and execution of Umoja Wetu,

was put in a difficult position. While some diplomats and UN officials recognized the serious limitations of the Congolese army’s capacity to conduct these operations effectively and the potentially catastrophic consequences for the civilian population in the Kivus, they believed they had no choice but to go ahead. Some UN officials believed they could do more to protect civilians by being part of the operations, rather than being on the outside.

On March 2, the Congolese army jointly with MONUC peacekeepers launched the second phase of military operations against the FDLR, known as operation Kimia II (“quiet” in Swahili). On April 7, President Kabila appointed Maj. Gen. Dieudonné Amuli Bahigwa as the Congolese army commander of the operation.[65] Former CNDP officers received important command positions. Bosco Ntaganda, a newly made general in the Congolese army, was in effect deputy commander of operation Kimia II. Aware that Ntaganda was wanted on an arrest warrant from the ICC, and that the Congolese government, as a state party to the ICC, had a legal obligation to arrest him, Congolese government officials kept Ntaganda’s name out of the official organizational structure of operation Kimia II. On May 29, the Congolese minister of defense wrote to Alan Doss, the head of MONUC, to say that Ntaganda was not playing a role in Kimia II.[66] The assurances, however, were false. According to at least five Congolese army officers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, and internal Congolese army documents, Ntaganda was the de facto deputy commander of operations for Kimia II and was in charge of integrating CNDP soldiers into the Congolese army. His regular presence in Goma and his repeated visits to troops on the frontlines all demonstrated he played an important role.

Outcome of Military Operations since January 2009

As a result of the Congolese army’s military operations, a significant number of FDLR combatants have given up their weapons and returned to Rwanda. Since the start of military operations in January 2009, more FDLR combatants have voluntarily decided to give up their arms and return to Rwanda than in previous years. Between January and September 2009, the UN’s Disarmament, Demobilization, Repatriation, Reintegration, and Resettlement (DDRRR) program, tasked with facilitating the return of foreign combatants, repatriated 1,087 FDLR combatants to Rwanda. They have been joined by 1,798 family members and 12,387 Rwandan refugees.[67]

The return of such a large number of combatants and civilians to Rwanda is significant. In combination with the destruction of a number of FDLR bases, their exclusion from mining zones and other areas of economic activity, where they previously reaped financial benefits, has, according to some analysts, weakened the FDLR militarily.[68]

However, the FDLR still retains capacity to carry out attacks against villages and towns. Human Rights Watch has received reports that the FDLR is recruiting new combatants and that the movement continues to raise funds and collect weapons and ammunition through numerous international networks, including through Tanzania, Burundi, Zambia, and Uganda.[69] The UN Group of Experts in their November 2009 final report concluded that military operations against the FDLR had failed to dismantle the group’s political and military structures on the ground in eastern Congo. The report added that the FDLR had regrouped in a number of locations in the Kivus, is recruiting new combatants, continues to benefit from support from some senior commanders in the Congolese army, and has formed alliances with other armed groups in both North and South Kivu.[70] While the FDLR have been pushed out of some mining areas and they no longer have access to certain markets they previously depended on, the militia group continues to control many important gold and cassiterite (tin) mining areas in North and South Kivu providing it with crucial financial income.[71]

The military operations may have also fanned the flames of underlying issues in eastern Congo that have often led to conflict in the past, namely land and control over natural resources. Many of the offensive operations of Kimia II have been led by former CNDP commanders, who according to some sources, have also sought to use the operations to gain control over mineral-rich areas and to clear the land for returning Congolese Tutsi refugees and cattle being brought in from Rwanda. The perceived leadership roles and preferential treatment given to former CNDP commanders has also led a number of former Mai Mai combatants, along with other disgruntled Congolese army soldiers, to abandon the Congolese army, or refuse to join the integration process. Some have joined forces with the FDLR, strengthening their ranks.[72]

The human cost of the military operations can only be described as devastating. Human Rights Watch researchers have collected interview testimony indicating that between January and September 2009, over 1,400 civilians were deliberately killed by the FDLR, the Congolese army, and their allies. This figure does not include civilians who may have been killed by crossfire during the fighting and, furthermore, Human Rights Watch has credible reports of 476 civilians killed by the Congolese army and its allies in a remote area that Human Rights Watch has not been able to access in order to establish the circumstances of the deaths.