Meeting the Challenge

Protecting Civilians through the Convention on Cluster Munitions

Table of Acronyms

ANZCMC |

Aotearoa New Zealand Cluster Munition Coalition |

ATACMS |

Army Tactical Missile System |

CCW |

Convention on Conventional Weapons |

CDDH |

Diplomatic Conference on the Reaffirmation and Development of International Humanitarian Law Applicable in Armed Conflicts |

CEP |

Circular error probable |

CIS |

Commonwealth of Independent States |

CMC |

Cluster Munition Coalition |

DAFA |

Demining Agency for Afghanistan |

DoD |

US Department of Defense |

DPICM |

Dual-Purpose Improved Conventional Munition |

ERW |

Explosive remnants of war |

FY |

Fiscal Year |

GGE |

Group of Governmental Experts |

GMLRS |

Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System |

GWAPS |

Gulf War Air Power Survey |

ICBL |

International Campaign to Ban Landmines |

ICRC |

International Committee of the Red Cross |

IDF |

Israel Defense Forces |

IMI |

Israel Military Industries |

JSOW-A |

Joint Standoff Weapon-A |

MACC SL |

UN Mine Action Coordination Center–South Lebanon |

MLRS |

Multiple Launch Rocket System |

NGO |

Nongovernmental organization |

OMAR |

Organization for Mine Awareness and Afghan Rehabilitation |

RSK |

Republic of Serbian Krajina |

SADARM |

Sense and Destroy Armor Munition |

TLAM-D |

Tomahawk Land Attack Missile-D |

UN MACC |

UN Mine Action Coordination Center |

UNDP |

UN Development Program |

UNIFIL |

UN Interim Force in Lebanon |

UNMIK |

United Nations Mission in Kosovo |

UXO |

Unexploded ordnance |

WCMD |

Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser |

WILPF |

Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom |

WRSA |

War Reserve Stocks for Allies |

Introduction

For half a century, cluster munitions have inflicted suffering on civilians. Bystanders to armed conflicts have lost limbs, livelihoods, and even their lives. Cluster munitions are deadly both at the time of attack and afterwards. During strikes, they blanket areas the size of football fields with submunitions that spray high-velocity fragments in all directions. Many of these submunitions fail to explode on impact and linger for months or even years, able to be accidentally detonated by the unsuspecting farmer or child. The impact of these weapons has been felt around the globe.

While the threat persists, the international community has taken a strong stand against cluster munitions. After traditional disarmament approaches fell short, a group of like-minded states, in collaboration with civil society, moved discussions to an independent forum. The Oslo Process, a series of diplomatic conferences to develop and negotiate a treaty on cluster munitions, produced a comprehensive ban in just 15 months.

Ninety-four states signed the Convention on Cluster Munitions in Oslo on December 3, 2008, and 14 more would later add their signatures. In opening remarks at the signing conference, the minister of foreign affairs from Laos, one of the countries most affected by cluster munitions, referred to the event as a “historic moment of our humankind,” and his counterpart from Lebanon, a nation recently victimized by cluster munitions, described it as “a remarkable and exceptional moment for the world.” The convention has established a powerful and essential legal framework for eliminating the scourge of cluster munitions.

The convention became binding law on states parties when it entered into force on August 1, 2010, but much work must be done to fulfill its promise. A minister from Ireland cautioned at the signing conference, “We must not rest on our laurels.” States and civil society should continue their efforts to bring more countries on board, thereby extending the convention’s reach and increasing stigmatization of the weapons. They should demand comprehensive implementation measures at both national and international levels to meet the convention’s aims and take early action on stockpile destruction, clearance, and victim assistance to make an immediate difference on the ground. They should also push for strong interpretations of the convention’s provisions consistent with its overarching purpose.

This book seeks to build on the momentum of entry into force of the convention and advance ongoing efforts to achieve a world free of cluster munitions. It describes the dangers of cluster munitions and explains why those threats will continue as long as the weapons exist. It charts the development of the treaty process, examining which approaches fell short and which produced positive change. Finally, the book analyzes the elements of the new international convention and provides guidance on the remaining actions needed to implement it fully.

Cluster Munitions and their Human Toll

Cluster munitions are large munitions that contain dozens and often hundreds of smaller submunitions. Either air dropped or surface launched, cluster munitions are area effect weapons that spread their submunitions over a large field, or footprint. They are designed to be effective against targets that move or do not have precise locations, such as enemy troops or vehicles, and to destroy targets that cover broad areas, such as airfields and surface-to-air missile sites. Early submunitions were primarily antipersonnel, but many of today’s models have multiple effects. Scored shells are intended to maim or kill people by breaking into fragments, while anti-armor devices serve to damage vehicles and materiel. Militaries value cluster munitions because of their wide footprint and versatile submunitions.

The military benefits of cluster munitions, however, do not justify the harm they cause to civilians. The weapons present two grave humanitarian problems. First, civilians all too often fall victim to cluster munitions during strikes. The large number of submunitions is widely dispersed, which creates a footprint deadly to all inside. Within that space, no submunition has the capability to distinguish between soldiers and civilians. In addition, the cluster munition canisters that carry the submunitions are usually unguided, so they can miss their mark and hit non-military objects. The inherent risks to civilian life and property are nearly unavoidable when cluster munitions are used in or near populated areas, a common occurrence in modern armed conflict. If cluster munitions are used in an area where combatants and civilians commingle, civilian casualties are almost assured. In every conflict involving cluster munition use that Human Rights Watch has investigated, the weapons have been used in areas where both combatants and civilians are present, resulting in loss of civilian life.

Second, cluster munitions leave unexploded submunitions, or duds, that continue to kill or injure people after a conflict ends. The quantity of submunitions in each cluster munition, combined with design characteristics and environmental factors, means that some will always fail and become de facto landmines that can be set off later by unwitting civilians. Children are particularly common victims. The shape and sometimes color of submunitions attracts them because they are curious and believe the weapons are toys. Some models resemble balls while others have a ribbon, which makes a convenient handle for carrying or twirling. Unexploded submunitions also frequently cause casualties among farmers, who do not see them hidden in their fields and hit them with their plows. The duds have socioeconomic costs because they contaminate agricultural land, making it unfit for planting or harvesting.

The Convention on Cluster Munitions

The Convention on Cluster Munitions aims to protect civilians by eliminating the weapons and the harm they cause. Its preamble states that its purpose is “to put an end for all time to the suffering and casualties caused by cluster munitions at the time of their use, when they fail to function as intended or when they are abandoned.” To accomplish this goal, the convention prohibits states parties “under any circumstances” from using, producing, transferring, or stockpiling cluster munitions. It also prohibits states parties from assisting anyone with any of those activities.

In addition to laying out what states must not do, the convention imposes a set of positive obligations. To achieve its disarmament goal, it requires states parties to destroy stockpiles within eight years. To ensure establishment of remedial humanitarian measures, it obliges affected countries to clear cluster munition remnants within 10 years and provide a range of types of assistance to victims. The convention also includes provisions that will help advance effective implementation by all parties. States parties must provide cooperation and assistance to help other states parties meet their obligations, fulfill detailed reporting requirements which facilitate both implementation and monitoring, take legal and other measures to implement the convention at the national level, and promote the norms of the convention.

Overview of the Book

This book has three main parts. Part I: Recognizing the Problems traces the humanitarian costs of cluster munitions from their origins to the present and details the threats they will continue to pose if left unchecked in the future. When the United States blanketed Southeast Asia with cluster munitions during the Vietnam War, it represented the first widespread use of a munition that would become a staple of arsenals around the world and left millions of unexploded submunitions that still kill and maim civilians. More recent use of cluster munitions in five conflicts over the past decade has shown that improvements in technology and targeting do not eliminate the civilian casualties that occur during strikes and afterwards. Production, transfer, and stockpiling of cluster munitions, which are prerequisites to use, are both widespread and ongoing. Minimizing human suffering post-conflict presents additional challenges. It requires effective clearance, a time-consuming, expensive, and sometimes deadly endeavor; it also demands extensive risk education and a variety of forms of victim assistance. This examination of the range of problems demonstrates why a separate treaty that bans the weapon is the only solution.

Part II: Developing a Process explores the evolution of efforts to address the problems of cluster munitions and examines why they culminated in success. It also identifies key elements that can serve as models for similar campaigns in the future. For many years, international attempts to deal with cluster munitions fell short, demonstrating that traditional diplomacy could not deal with the growing crisis. During that time, many states began to take national measures that both demonstrated opposition to cluster munitions and increased restrictions on the weapons. A majority of the initiatives were partial regulations, however, and the ad hocnature even of domestic bans highlighted that a global problem needed a global solution. Drawing on the example of the Mine Ban Treaty negotiations, the Oslo Process adopted a bold, forward-looking approach that was broadly representative, independent, and expedient. This type of humanitarian disarmament process was essential to achieving an absolute and comprehensive ban.

Part III: Fulfilling the Promise analyzes the content of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and provides direction for how to realize its potential. This groundbreaking convention, which categorically bans cluster munitions and establishes rigorous disarmament and humanitarian duties, addresses all of the problems of cluster munitions while pushing international law in new directions. Some major military powers have shown resistance to the convention by advocating for alternatives that merely regulate the weapons. The international community must counter such efforts to undermine the convention and complete the process begun in Oslo by bringing on additional parties, implementing all of its obligations, and agreeing to strong interpretations of the convention’s provisions. Only when these goals are reached will the world succeed in eliminating the lingering threat posed by these inhumane weapons.

Part I: Recognizing the Problems

I. The Technological Evolution and Early Proliferation and Use of Cluster Munitions

A half-century ago, cluster munitions were a little known instrument of warfare. They have since become common—if controversial—weapons for most modern militaries. Cluster munitions gained preferential status through a combination of technological innovations, changing combat needs, industrial interests, permissive laws, and lack of public awareness or debate. These factors produced an area effect munition that exacts a lethal and predictable, even if unintentional, toll on civilians.

From their first major use, the civilian harm inflicted by cluster munitions has outweighed their military benefits. During the Vietnam War, the United States blanketed Southeast Asia with the weapons, causing civilian casualties at the time of attack and leaving millions of unexploded submunitions that continue to kill and maim decades later. Since then, cluster munitions have proliferated widely and been used in almost every region of the world. While the design of cluster munitions has evolved in ways that theoretically could reduce humanitarian harm, technological fixes have failed to eliminate the weapons’ negative effects. The history of development, use, and proliferation illuminates the major problems of cluster munitions and foreshadows the impact they still have today.

Early Development and Use

The technology that produced the earliest cluster munitions also gave rise to their devastating effects. Through experiments conducted in the early twentieth century, scientists determined that small, high-velocity projectiles were the most effective means of maximizing injury.[1] Equipped with this insight, weapons designers worked to develop the controlled fragmentation of explosive devices by using certain metals and pre-fragmented materials.[2] While increased and more predictable fragmentation ensured the lethality of individual submunitions, new fuze technology made their wide dispersal possible. In particular, mechanical time fuzes installed on the large container that carried submunitions released submunitions after the passage of a certain period of time, allowing them to spread over a wide footprint and hit a large number of targets.[3] While the design of cluster munitions would continue to evolve, developments in fragmentation and fuze technology created a deadly weapon with a broad area effect.

Modern cluster munitions date back to the First World War, when Britain had the idea of dropping a group of munitions for incendiary bombing.[4] Cluster-type weapons were also used during World War II, but at the time, military officials did not consider cluster munitions very effective because they were unable to control dispersal patterns.[5] Although cluster munitions were not used during the Korean War, it sparked technological innovations that would make submunitions less expensive and more effective, and therefore more widespread. The United States sought weapons with maximum antipersonnel impact to offset the disadvantage of being outnumbered by enemy troops. Controlled fragmentation munitions, with their ability to incapacitate through debilitating wounds, offered a solution.[6]

Southeast Asia

The Vietnam War made cluster munitions a staple of military operations, and a weapons expert described it as “a proving ground” for the weapons.[7] Faced with Cold War insurgencies in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the US government pursued the development of conventional weapons that could combat guerilla enemies, who were often difficult for US soldiers to locate.[8] The United States also wanted weapons that could attack anti-aircraft artillery and surface-to-air missions when their locations could not be pinpointed.[9] Officials, therefore, pushed forward arms research on fragmentation, dispersal, and detonation. For example, new dispensers were designed to hold more submunitions and disperse these submunitions more widely.[10] A mechanical device that would trigger submunition detonation based on the submunition’s spin rate was invented to prevent submunitions from exploding until they had penetrated the forest canopy (thus slowing the spin rate).[11] By the time US troops began their major buildup in Southeast Asia, these branches of research had converged to enable the production of area effect cluster munitions that were affordable and ready for use in battle.

The United States made widespread use of a variety of cluster munitions during the Vietnam War. According to an analysis of bombing data by Handicap International, over the course of the conflict, US forces dropped approximately 80,000 cluster munitions (containing 26 million submunitions) on Cambodia, more than 296,000 cluster munitions (containing nearly 97 million submunitions) on Vietnam, and more than 414,000 cluster munitions (containing at least 260 million submunitions) on Laos.[12] While the most common models were antipersonnel, some could also attack vehicles, a multi-effects trend which continues today.[13] The area over which Vietnam War-era cluster munitions could spread submunitions ranged from 10,000 to 200,000 square meters.[14]

US cluster munition attacks wrought tremendous harm against civilians in Indochina, and continue to do so. Michael Krepon, later founder of the Henry L. Stimson Center in Washington, DC, called cluster munitions “the most indiscriminate antipersonnel weapon used in the Vietnam War.”[15] Much of the harm resulted from munitions that failed to explode when originally released but were later triggered by civilian passersby. Assuming a conservative dud rate of 5 percent and relying on Handicap International’s estimated number of total submunitions used, cluster munitions would have left more than 19 million unexploded submunitions. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), unexploded submunitions have killed or injured some 11,000 people in Laos, more than 30 percent of whom have been children.[16] Civilians continue to this day to be killed and injured by unexploded submunitions in all three countries.[17] There is no credible estimate of the amount of land still contaminated, but it will likely take decades to clear.

The use of cluster munitions provoked increasing public opposition to the Vietnam War in the United States and elsewhere. Though napalm was the weapon antiwar protesters targeted most, cluster munitions had a mobilizing effect as well. Opponents criticized the manufacturers of cluster munition components,[18] and peace activists and antiwar journalists visiting North Vietnam discovered and reported on the humanitarian impact of the weapons.[19] Serious doubts also existed as to whether the weapon on balance helped US military efforts.[20] The uncoordinated and unsustained opposition to cluster munitions, along with a deliberate government policy of secrecy and lack of debate,[21] precluded successful international initiatives to regulate or ban cluster munitions at this stage.

Early Proliferation of Cluster Munitions: 1970s and 1980s

The conflict in Southeast Asia significantly raised the profile of cluster munitions and transformed them from a military experiment into a mainstream weapon. By 1973, for example, cluster munitions comprised 29 percent of the US Air Force’s entire ordnance procurement budget.[22] The weapons also quickly proliferated.

Use in the 1970s and 1980s extended to Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and South Asia. In Africa, unknown forces left cluster munition remnants in Zambia (1970s), Morocco used cluster munitions against a non-state armed group in Western Sahara and Mauritania (1975-1991), the United States attacked Libyan ships (1986), and France and Libya launched attacks in Chad (1986-1987). In the Americas, the United Kingdom dropped 107 cluster munitions on the Falkland Islands/Malvinas (1982), and the United States dropped 21 in Grenada (1983).[23] In the Middle East, Israel used cluster munitions in Syria in 1973 and in Lebanon in 1978 and 1982.[24] The United States used cluster munitions against Syrian units in Lebanon in 1983 and Iranian ships in 1988, and Iraq used cluster munitions in its war with Iran beginning in 1984. Finally, the Soviet Union, which would become another major user, used cluster munitions during its invasion of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989, primarily to attack mujahiddeen strongholds and exposed fighters.[25]

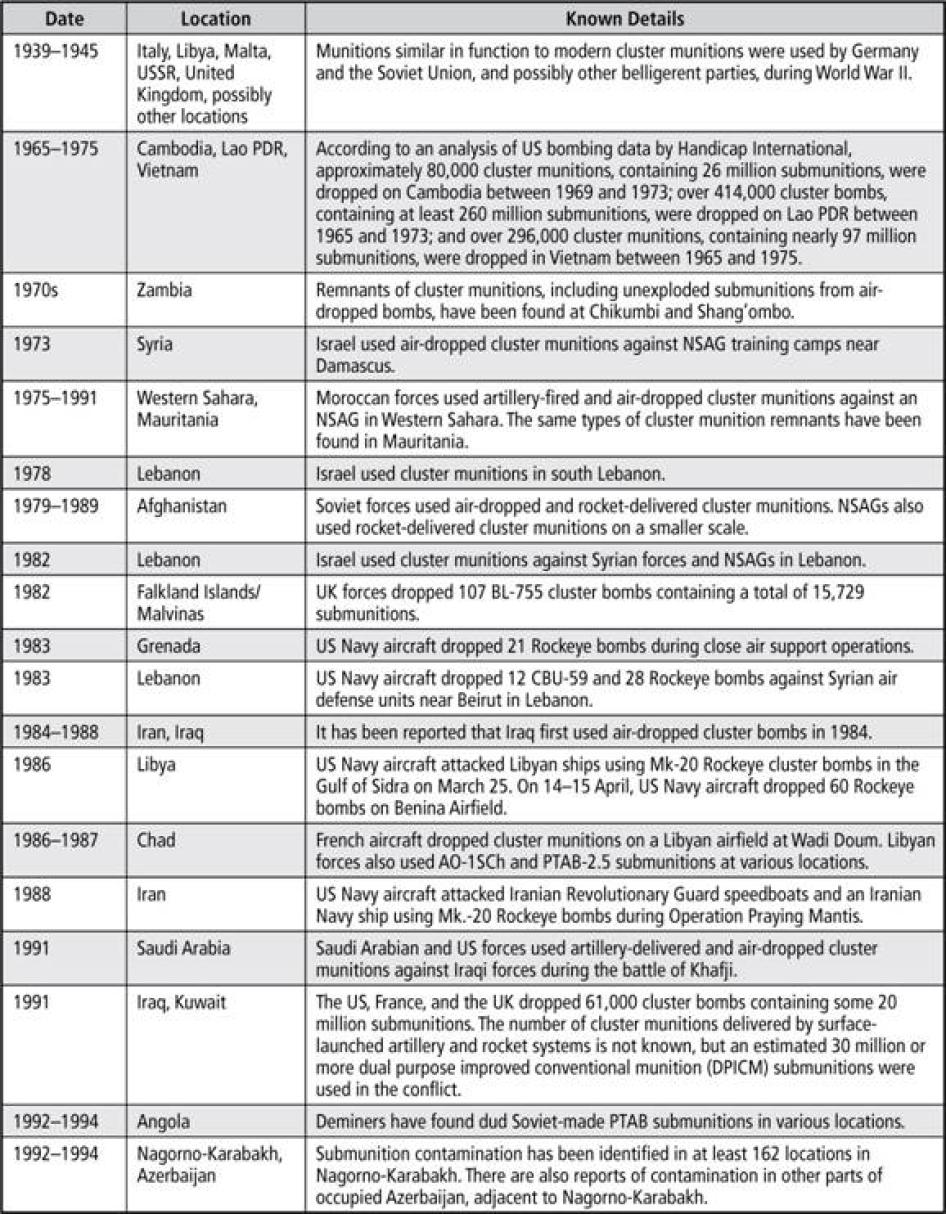

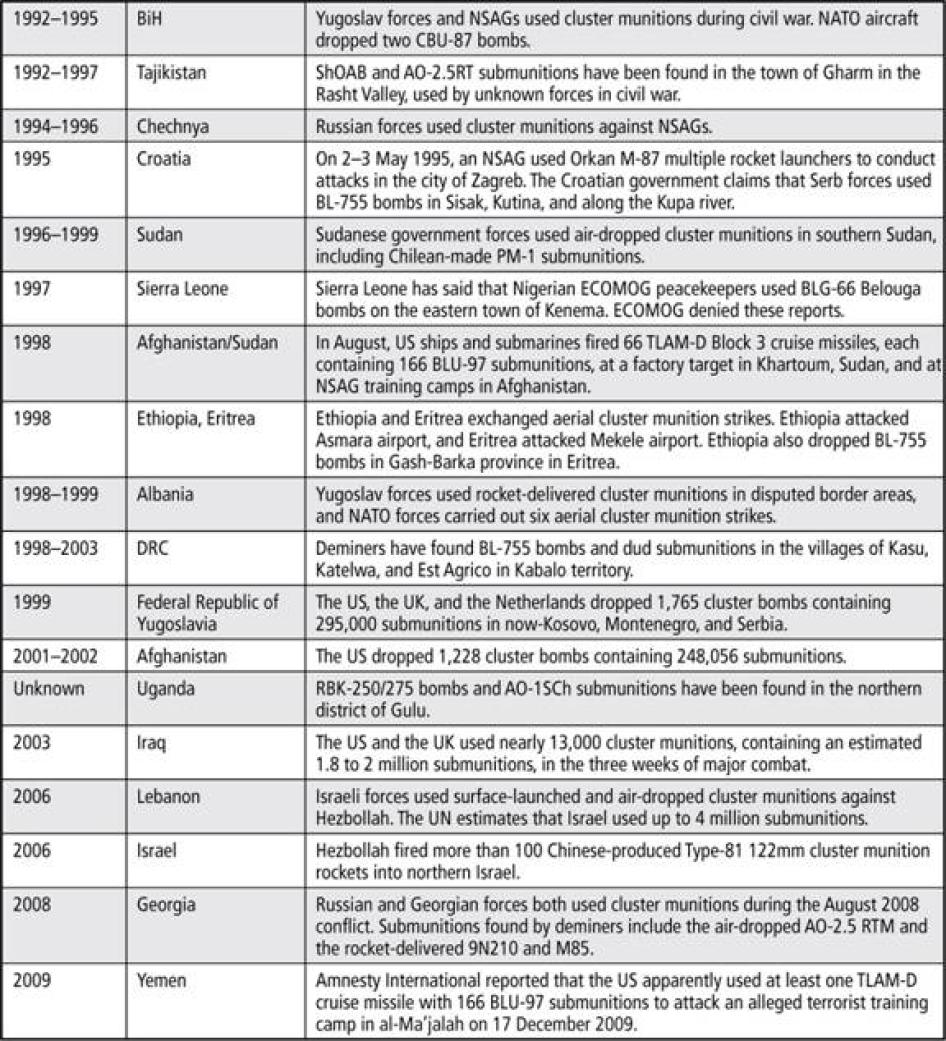

Timeline of Cluster Munition Use[26]

A Spike in Use: 1990s

The Gulf War of 1991

The United States and its allied coalition opened the 1990s with the most extensive use of cluster munitions since the Vietnam War. Cluster munitions accounted for about one-quarter of the bombs dropped on Iraq and Kuwait during the Gulf War of 1991.[27] Between January 17 and February 28, 1991, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and to a limited extent Saudi Arabia dropped about 61,000 cluster bombs, releasing twenty million submunitions, only about 15 percent of which were new models.[28] They used an additional estimated 30 million surface-launched submunitions.[29] Coalition armed forces notably targeted mobile SCUD missiles and Iraqi tank and vehicle columns retreating from Kuwait.[30] As a result, unexploded submunitions littered roads, culverts, and bridges. Coalition forces also used cluster munitions in urban areas, leading to attacks on infrastructure and dual use targets frequented by civilians during and after the war.[31] Exacerbating the humanitarian threat, use of low-altitude cluster munitions at medium to high altitudes decreased the accuracy of strikes and increased the dispersal pattern of the submunitions.[32]

While the lack of precision exacerbated the risk to civilians during strikes, duds caused most of the civilian cluster munition casualties in the Gulf War. As of February 1993, unexploded submunitions had killed 1,600 civilians and injured 2,500 more.[33] Post-war research revealed an “excessively high dud rate” due to the high altitude from which they were dropped and the sand and water on which they landed.[34] The large quantity of cluster munitions added to the problem; even a 5 percent dud rate would have left more than 2 million unexploded submunitions. The plethora of duds on major roads put both refugees and foreign relief groups at risk.[35] The duds particularly endangered children; 60 percent of the victims were under the age of fifteen.[36]

Unexploded submunitions caused other significant side effects. First, they slowed economic recovery because duds needed to be cleared before people could restore industrial plants, communication facilities, and neighborhoods[37] and extinguish the oil fires in Kuwait.[38] Second, during and after the war, unexploded ordnance (UXO), including submunitions, represented the “greatest threat” to US troops.[39] Submunitions killed or injured more than 100 US soldiers and killed an additional 100 clearance workers.[40]

Other Conflicts in the 1990s

Over the course of the rest of the decade, militaries used cluster munitions in armed conflicts in Africa, Central Asia, and Europe. In Africa, both Eritrea and Ethiopia used the weapons in their 1998 territorial dispute over the Badme border area, causing hundreds of civilian casualties.[41] Other cluster munition attacks in Africa affected Angola, Sudan, Sierra Leone, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo during this time period.[42]

The use of cluster munitions also accompanied the breakup of the Soviet Union. Cluster munition remnants were found from conflicts in Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan (1992-1994) and Tajikistan (1992-1997).[43] The Russian government used cluster munitions extensively in Chechnya between 1994 and 1996 and again in 1999. The attacks culminated in at least 636 casualties, including 301 deaths.[44] Russia directed many, if not most, of its cluster munition attacks, including the 1999 attack on the Grozny market, at civilian areas.[45] According to one estimate, the Grozny attack killed 137 people.[46]

Conflict in the Balkans led to use of cluster munitions in Europe, which became the decade’s most affected region. Internal and NATO forces used cluster munitions in Bosnia and Herzegovina between 1992 and 1995, reportedly causing at least 92 casualties, of which 13 individuals were killed and 79 injured.[47] Armed forces of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) used cluster munitions in Croatia in 1995, causing 221 known casualties (7 individuals killed and 214 injured) at the time of attack alone. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia ultimately found RSK President Milan Martic guilty of crimes against humanity for cluster munition attacks that landed on Zagreb’s commercial center in May of that year.[48] During the 1999 conflict in Yugoslavia, which will be discussed in detail in the next chapter, NATO forces launched an extensive air campaign that used cluster munitions, and both NATO and Yugoslav armed forces used cluster munitions in Albania, which was not party to the fighting.[49] Overall, cluster munitions were likely used more extensively during the 1990s than in the previous two decades combined.

Modern Technological Developments

After the Vietnam War, as use of cluster munitions spread, the technology of cluster munitions continued to evolve. A trio of developments has attempted to improve cluster munitions’ accuracy and reliability, primarily for military reasons but also to decrease humanitarian harm. None, however, has succeeded in eliminating the inherent problems of the weapons.

Perhaps the most important technological change was the addition of devices designed to reduce dud rates, including self-destruct, self-neutralization, and self-deactivating mechanisms. In theory such devices would minimize the number of civilian casualties, but as exemplified by the use of M85 submunitions with self-destruct devices, they failed to do so. British ground forces used M85s for the first time in combat during major hostilities in Iraq in 2003.[50] One British officer told Human Rights Watch that his troops were more careless about using the M85 in populated areas because they assumed the self-destruct mechanism had eliminated the humanitarian impact and they neglected to consider the danger of cluster munitions during strikes.[51] The true test of M85s came when Israel, which produces the submunitions, used them extensively in south Lebanon in 2006. Many military experts at that time consider it to be the most reliable submunition model produced because it had a 1.3 to 2.3 percent dud rate in tests.[52] Clearance groups in Lebanon found numerous unexploded M85 submunitions with self-destruct mechanisms, however, indicating that the M85’s self-destruct component did not always work as designed.[53] In an in-depth study of strike locations where these submunitions landed, C. King Associates, the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, and Norwegian People’s Aid concluded that the failure rate of such submunitions in Lebanon was in fact around 10 percent.[54] The UN Mine Action Coordination Center–South Lebanon (MACC SL) echoed this finding.[55] In both Iraq and Lebanon, a touted “technological fix” had failed to eliminate the humanitarian problems of cluster munitions.

Modern cluster munition technology has also sought to increase the accuracy of the container itself. More precision would improve the chances of hitting the intended target, which would have military and humanitarian benefits. During its bombing of Afghanistan in 2001, the United States used for the first time in combat the CBU-103, regarded as a technical improvement over the CBU-87 used in the Gulf War.[56] It was outfitted with a Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser (WCMD) designed to improve accuracy by compensating for wind encountered during its fall and narrowing the pattern of submunition dispersal.[57] Despite pronouncements by the US Air Force that the CBU-103 was “highly successful,”[58] Human Rights Watch did not find evidence during field missions in Afghanistan and Iraq to conclude that the modification provided a technological fix to the humanitarian problems caused by cluster munitions. In particular this model still released 202 submunitions, many of which did not explode on impact as designed, and was vulnerable to poor targeting. Other more precise munitions, such as the Joint Standoff Weapon-A (JSOW-A) and BGM-109D Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM-D), have been equipped with submunitions but used much more rarely.[59]

Cluster munitions that have guided submunitions with fail-safe mechanisms, often called sensor fuzed weapons after a US model, are the most cutting-edge types in existence. The United States introduced its air-delivered Sensor Fuzed Weapon, or CBU-105, when it dropped 88 of them in Iraq in 2003.[60] Equipped with a WCMD to direct the canister, it contains 10 BLU-108 submunitions that each include four hockey puck-sized “skeet” warheads. Infrared and laser sensor guidance systems on the skeets are designed to direct them to targets with high heat sources, such as armored tanks, parked airplanes, and vehicles.[61] If they fail to find such a target, one of a trio of fail-safe mechanisms is supposed to activate.[62] The manufacturer, Textron Defense Systems, claims that these redundant mechanisms “are key elements that distinguish [Sensor Fuzed Weapons] from traditional munitions, preventing hazardous unexploded ordnance and ensuring a clean battlefield for follow-on troop movement and civilian habitation of the area.”[63] Not enough evidence is available, however, to determine what kind of humanitarian impact sensor fuzed weapons would have in the field, or whether they would function as designed under battle conditions.

Despite these multiple technological developments, states have also continued to use Vietnam War-era cluster munitions. The United States used updated versions of the Rockeye, containing 247 dart-shaped dual-purpose Mk-118 submunitions that are known to leave behind a high number of unexploded duds, in Yugoslavia in 1999, Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002, and Iraq in 2003.[64] In Yugoslavia and Iraq, the United Kingdom used variants of the air-dropped BL-755, modeled after another Vietnam War-era cluster munition containing 147 submunitions.[65] In Lebanon in 2006, Israel used US-manufactured and -supplied air-dropped CBU-58B cluster munitions containing 650 BLU-63 antipersonnel submunitions each.[66] Deminers after that conflict discovered CBU-58B canisters marked with a September 1973 load-date that suffered catastrophic failures, meaning that they failed even to dispense their submunitions.[67]

Conclusion

Over the past five decades, militaries increasingly have come to choose cluster munitions as an important element of their arsenals. At least 86 countries acquired stockpiles of the weapons and their use spread to Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East. Newer, more technologically advanced submunitions have been developed but have failed to solve humanitarian problems. At the same time, models from the 1970s continue to be used. While the Vietnam War may have been the most egregious case of civilian harm from cluster munitions, it was only the beginning.

II. A Decade of Cluster Munition Use: Recent Case Studies Documented by Human Rights Watch

The suffering caused by cluster munitions is not merely a historical problem. In the past 11 years, cluster munition use has resulted in disproportionate civilian harm in five major conflicts: Yugoslavia (1999), Afghanistan (2001-2002), Iraq (2003), Lebanon and Israel (2006), and Georgia (2008). In each, cluster munitions have had devastating effects on individuals and communities. They have killed and maimed civilians during strikes with explosions that sent shards of steel in every direction. Unexploded submunitions have lingered on the battlefield, endangering civilians, clearance professionals, and even friendly soldiers fighting through the areas where they were used. By contaminating fields and farms, cluster munitions have also interfered with livelihoods.

The five recent conflicts documented by Human Rights Watch illustrate varied types of cluster munition use and the dangers associated with them. The NATO air campaign in the former Yugoslavia showed the risks of using air-dropped models in urban areas, while the US bombing of Afghanistan demonstrated that use even in small villages or near populated areas can cause civilian casualties. The US-led Coalition’s invasion of Iraq exemplified the humanitarian problems of ground-launched cluster munitions and the failure to learn from past mistakes. Israel’s blanketing of south Lebanon proved that new technology can neither prevent the long-term danger of submunitions nor eliminate the risk of excessive use; Hezbollah’s attacks on Israel in the same conflict revealed that non-state armed groups have access to these weapons. Finally, use by Russia and Georgia in the conflict over South Ossetia highlighted that different kinds of players—from major users, producers, and stockpilers to first-time users who import their cluster munitions—turn to the weapons, and that cluster munitions often do not work as intended.

Over the course of these conflicts, some of the armed forces have tried strategies to decrease the harm to civilians of cluster munition attacks, including new technology, changes in targeting, and vetting processes. None have resolved the weapons’ problems. The results of Human Rights Watch field investigations, summarized below, illustrate that regardless of the specifics of an attack or the nature of the safeguards taken, cluster munitions always have predictable and unavoidable humanitarian consequences. The evidence calls for an absolute ban on the weapons.[68]

Methodology

Human Rights Watch field research on cluster munitions has developed over the years, but the essential components have remained consistent. As soon as the security situation allows, Human Rights Watch researchers conduct on-the-ground investigations to understand how and why civilians were killed or injured. Increasingly Human Rights Watch researchers are on the ground during the armed conflict or immediately after ceasefire, as was the case in Lebanon in 2006 and Georgia in 2008.

Research teams investigate the villages, towns, and general area surrounding cluster munition strikes. At each site Human Rights Watch researchers interview civilians directly affected by the attacks, visit hospitals to interview doctors and collect casualty statistics, meet with demining and aid organizations and military personnel, examine physical evidence of the strikes such as weapons debris and structural damage, and take documentary photographs. Human Rights Watch also employs GPS receivers and mapping programs in order to locate strikes and map data.

After an initial mission, Human Rights Watch continues to conduct follow-up interviews with civilians, deminers, medical experts, and military officials and often sends inquiries to the parties responsible for cluster munition use before compiling and analyzing all of the information gathered. In some cases, it returns to the site of the conflict to assess the long-term effects on civilians. The results of its findings are then made public in a full-length report with recommendations.

The NATO Air Campaign in the former Yugoslavia[69]

From March to June 1999, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands dropped at least 1,765 cluster munitions containing about 295,000 submunitions as part of Operation Allied Force, the NATO air campaign in the former Yugoslavia.[70] From the beginning, NATO and allied government and military officials stressed their intent to minimize civilian casualties, but despite reported precautions, their cluster munitions killed and injured at least 240 civilians at the time of attack and afterward. NATO could not overcome the threats posed by the inherent nature of cluster munitions.

This lesson emerged even as NATO’s bombing campaign was still in progress. Widespread reports of civilian casualties from cluster munitions and international criticism of these weapons as potentially indiscriminate became so apparent that, in mid-May 1999, President Clinton temporarily suspended US use of cluster bombs in this campaign. The order came just days after the NATO strike on Nis, which was particularly noteworthy for the civilian casualties that it caused.[71] It has been reported that the Netherlands may have also suspended its use of cluster munitions while the bombing campaign was still ongoing, due to humanitarian concerns, but it is unclear exactly when this policy change may have occurred.[72] The UK Royal Air Force, by contrast, continued to use the weapons through June 4, 1999.[73] This divergence of ad hoc policies underlined the need for universal, not national, norms regarding the weapons’ use in order to prevent, rather than merely react to, the civilian harm that these weapons cause.

Cluster Munition Strikes

According to Human Rights Watch’s research, cluster munition strikes killed 90 to 150 civilians and injured many more.[74] These figures represent 18 to 30 percent of the total civilian deaths Human Rights Watch documented in the conflict, even though cluster munitions amounted to a much smaller portion of the total number of bombs dropped.[75]

The most notable case of civilian deaths from cluster munitions occurred in Nis, when submunitions fell on an urban area, killing 14 civilians and wounding 28. On May 7, 1999, a US aircraft dropped CBU-87 cluster munitions, intending to destroy Serbian aircraft located at the Nis airfield. The cluster munitions misfired and fell from 1.5 to 6 kilometers off target in three populated civilian areas. Submunitions landed near the Nis Medical School in southeast Nis, in the town center including the area of the central city market place, and near a car dealership and parking lot. According to media reports, unexploded submunitions on several city streets and throughout the city center endangered civilians after the strike.[76]

NATO officials immediately described the incident as an accident. NATO Maj. Gen. Walter Jertz speculated that the cluster munitions may have gone astray due to “a technical malfunction or they could have been inadvertently released.”[77] According to US Air Force sources, the CBU-87 cluster munition container opened immediately after the plane released it, spreading submunitions over populated sites, instead of opening over the airfield it was intended to target.[78] Nis illustrated the danger of using cluster munitions in or near populated areas. Even when the weapons are intended for military targets, technical failure can occur at the expense of civilian lives.

Aftereffects

According to the ICRC, explosive submunition duds in Kosovo killed at least 50 civilians and injured at least 101 from June 1999 to May 2000.[79] The UN Mine Action Coordination Center (UN MACC) reported that fatal incidents involving cluster munition duds “generally involved groups of younger people, often with very tragic results.”[80] UN MACC estimated a dud rate between 7 and 11 percent, depending on the submunition model, and reported that more than 20,000 unexploded submunitions remained after the war.[81]

One incident occurred in Kosovo in August 1999, three months after the end of the NATO air strikes. Adnan, 6, was swimming with his family when he picked up a small yellow object and showed it to his family. Adnan’s older brother, Gazmend, 17, accidentally dropped the object, a submunition, causing it to explode. Gazmend and the boys’ father were killed, and Adnan suffered injuries to his left arm and leg. After the initial incident, Adnan’s sister, Sanije, 14, returned to the site to retrieve the family’s belongings. While she was there, Sanije stepped on a second submunition and was killed.[82] Events like this show how cluster munition duds can make even ordinary activities dangerous for civilian populations.

In addition to causing deaths and injuries, unexploded cluster munitions also disrupted civilians’ lives, interfered with the return of refugees, and slowed agricultural and economic recovery. The farming village of Bogdanovac, in southeast Serbia, for example, was littered with BL-755 submunitions, impeding the villagers’ ability to collect firewood. One villager explained, “When the weather turns cold, we pray to God, and then enter the woods.”[83] Unexploded submunitions have endangered and killed deminers and military clearance specialists,[84] and submunition clearance in the former Yugoslavia is ongoing, slow, difficult, and deadly.[85] Spurred by the horrific effects of cluster munitions during and after this armed conflict, Human Rights Watch in December 1999 became the first group to call for a global moratorium on the weapons.[86]

Afghanistan[87]

In 232 strikes, the United States dropped at least 1,228 cluster munitions containing 248,056 submunitions in Afghanistan between October 2001 and March 2002.[88] Cluster munitions represented about 5 percent of the US bombs dropped, a slightly smaller percentage than was used in Yugoslavia. In this conflict, the United States heeded some lessons from past use of cluster munitions, but the weapons continued to raise the same issues. Improvements in targeting did not eliminate the civilian harm caused by the use of cluster munitions in or near populated areas, and improvements in technology did not adequately overcome the fundamental, and fatal, flaws of the weapon. Unexploded US submunitions also endangered US troops, in several cases hindering their movements and slowing down operations.

In particular, the bombing of Afghanistan demonstrated the danger cluster munitions pose—during strikes and after—even in a less urban and industrialized setting. Unlike in some previous conflicts, the United States did not target roads or bridges in Afghanistan with either unitary or cluster munitions, but it did drop cluster munitions on and near inhabited villages. While Afghan villages are smaller than Yugoslavian cities, such targets accounted for many, if not most, of the more than 150 civilian casualties documented by Human Rights Watch from cluster munitions during this conflict. The reports of civilian casualties from US cluster munitions drew criticism from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), intergovernmental organizations, and some governments, leading to calls for an immediate moratorium until an international agreement could be reached.[89]

Cluster Munition Strikes

In a limited sampling of the three locations, Human Rights Watch confirmed that at least 25 civilians died and many more were injured during cluster munition strikes in or near populated areas. These casualty figures do not represent the total for the country because some deaths and injuries went unreported and because Human Rights Watch did not attempt to identify every civilian casualty caused by cluster munitions. The incident in the village of Ishaq Suleiman, northwest of Herat, exemplifies the danger of using these weapons in or near populated areas.[90]

Over the course of six days, beginning on October 31, 2001, the United States hit Ishaq Suleiman with five cluster munitions containing 1,010 submunitions. At least eight civilians died during the attacks, and four more died later from duds.[91] According to US officials, the United States did not intentionally target Ishaq Suleiman. US Air Force mission reports, and intelligence documents indicate that the strikes were intended for the nearby Fourth Armored Brigade Headquarters.[92] The five cluster munitions that landed in Ishaq Suleiman over the course of six days were fatal accidents. Instead of using the more technologically advanced CBU-103, the United States chose to use the less accurate CBU-87. US Air Force sources also revealed that the choice to fly toward, rather than away from, Ishaq Suleiman resulted in submunitions falling on the village. The use of CBU-87 cluster munitions so near a civilian population was clearly the wrong choice of weapon, but a strike on such a location with any type of cluster munition is unacceptably dangerous to civilians.

Aftereffects

Using a conservative estimate of a 5 percent dud rate, the cluster munitions dropped by the United States in Afghanistan likely left more than 12,400 explosive duds.[93] According to the ICRC, from October 2001 to November 2002, submunition duds killed or injured at least 127 civilians as well as two deminers.[94] These figures are not complete as they fail to take into account civilians who suffered slight injury or those casualties after November 2002. All but 12 of the victims were male, presumably because women have less freedom of movement in Afghanistan, and 68 percent of victims were children under the age of 18.[95]

Shepherds, farmers, and children were frequent victims of submunitions in Afghanistan.[96] For example, in Ishaq Suleiman, a dud killed Abdul Raziq, 43, and Ghouse-u-din, 37, four days after the bombing while they were grazing sheep near an ancient shrine. One month later deminers were finally able to clear the site of BLU-97 submunitions.[97] Submunitions that sunk into soft soil or hid in furrows presented risks for farmers. On December 21, 2001, Arbrabrahim, 52, died while plowing a field in Jebrael near Herat.[98] Submunitions made gathering wood, an occupation of many children, dangerous. Three children from Nawabad died while collecting wood at the Firqa #17 military base in Herat.[99] Duds also harmed livelihoods, spreading over fields, vineyards, and gardens and hindering the ability of civilians to return to or use their land.

Unexploded submunitions even interfered with the US military’s conduct of the war, endangering its own soldiers and slowing down operations. The United States used cluster bombs extensively in the cave regions, only to discover later that the duds posed a threat to ground troops. “We really have to watch where we’re … walking. We limited our night movement because of the unexploded ordnance up on … this ridge,” a soldier told a CBS reporter during Operation Anaconda.[100] US soldiers usually prefer to fight at night when they have the technological advantage of night vision. The danger of stepping on submunitions forced them to cut back on such operations, reducing their advantage.

Iraq[101]

The United States and the United Kingdom used nearly 13,000 cluster munitions, containing an estimated 1.8 to 2 million submunitions, during the three weeks of major hostilities in Iraq in March and April 2003.[102] Use of cluster munitions in Iraq highlighted the dangers of ground-launched models. Unlike in Yugoslavia and Afghanistan, where the United States and its allies only used air-dropped cluster munitions, Coalition forces used far more ground-launched cluster munitions than air-dropped ones. Ground-launched cluster munitions were less accurate than the newer, air-dropped models used by the US Air Force and caused excessive civilian casualties around the country during and after the conflict. The heavy use of these cluster munitions in populated areas where both soldiers and civilians were present exacerbated the problem and produced the majority of casualties.

The use of cluster munitions in Iraq, like that in Afghanistan, also exemplified states’ attempts to mitigate the widespread humanitarian harm caused by cluster munitions and their inability adequately to prevent it. In Iraq, US and UK forces established procedures to vet ground-launched cluster munition strikes, but such precautions failed to protect civilians. The targeting of residential neighborhoods, which were not classified as no-strike sites, caused hundreds of civilian deaths and injuries. Human Rights Watch estimated that cluster munitions caused more civilian casualties than any Coalition weapons other than small arms. In addition, as in Afghanistan, cluster munition duds endangered the Coalition’s own soldiers and interfered with military operations.

Coalition ground forces launched some 11,600 surface-delivered cluster munitions containing at least 1.6 million submunitions, most of which represented pre-existing technology.[103] The majority of the US ground-launched cluster munitions delivered contained Dual-Purpose Improved Conventional Munitions (DPICMs).[104] These submunitions resemble gray light sockets in size and shape and have a loop of ribbon at the top to stabilize and arm them. Each one consists of a scored, antipersonnel, steel fragmentation case with an armor-piercing shaped charge inside and can be launched by artillery or rocket.[105] According to US government sources, these cluster munitions have dud rates ranging from 3 to 23 percent.[106] The United Kingdom, as noted earlier, used the L20A1 artillery projectile, containing 49 M85 submunitions with self-destruct devices.

Coalition air forces also relied primarily on technology that had fallen short in the past when they dropped at least 1,276 cluster munitions containing more than 245,000 submunitions.[107] The bulk of the Coalition’s air-dropped cluster munitions were CBU-103s with WCMDs, containing the same BLU-97 submunitions used in Yugoslavia and Afghanistan.[108] As discussed in Chapter 1, the United States also used for the first time in combat the CBU-105, a sensor fuzed weapon.

Cluster Munition Strikes in the Iraq Ground War

Coalition ground forces did not learn the lessons of past wars, and their cluster munitions killed or wounded hundreds of civilians in populated areas. The United States did not reveal full details about the ground-launched cluster munitions they used,[109] but based on available information, Coalition cluster munition strikes left many tens of thousands of submunition duds.[110] The United Kingdom reported it used 2,100 ground-launched L20A1 cluster munitions, dropping 102,900 submunitions on Iraq.[111] Human Rights Watch found widespread use of cluster munitions in most of the cities it visited.[112]

Coalition ground forces used cluster munitions primarily as a counter-battery tool designed either to respond to or to prevent incoming fire from Iraqi forces. The targets of such strikes—enemy mortars, artillery, and troops—were legitimate, but the use of cluster munitions was inappropriate because of the weapon’s large footprint combined with the fact that the targets were in or near populated areas.[113] A unitary weapon would have been a preferable response to Iraqi fire from urban areas; however, officers of the Third Infantry Division complained that if they needed long-range rocket artillery, the Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) with submunitions was the only option they had. Therefore, they said, they often had to use cluster munitions for counter-battery fire when a unitary warhead would have sufficed.[114] The standard volley of six rockets from the MLRS would release approximately 4,000 submunitions, with a 5 to 23 percent dud rate, over an area with a radius of one kilometer.[115] The wide footprint and high number of duds resulted in civilian casualties during and after strikes.

The US and UK militaries employed procedures to vet these ground-launched cluster munition strikes. US forces screened ground-launched cluster attacks through computer and human vetting systems. The computer contained a no-strike list of more than 12,700 sites including schools and hospitals. Strikes were supposed to be kept at least 500 meters away from these sites, and visual confirmation of a clear military target was required.[116] The Third Infantry Division also required lawyers in the field to review proposed strikes and weigh military necessity against potential harm to civilians.[117] British ground forces had a no-strike list, and while they did not have a legal review of each strike, they were required to confirm visually that no civilians were present.[118]

These precautions failed to protect civilians, however, because Coalition ground forces still used cluster munitions in residential neighborhoods. As a result, ground-launched cluster munition attacks, even those on legitimate military targets, were one of the major causes of civilian casualties during the war. The accounts detailed below of al-Hilla and Basra exemplify the civilian casualties of ground-launched cluster munition strikes in populated areas.

Al-Hilla

Al-Hilla and its surrounding neighborhoods and villages suffered the most from ground-launched cluster munitions. In Nadir, a poor neighborhood on the south side of the city, for example, every household Human Rights Watch visited had experienced personal injury or property damage from a March 31, 2003 attack by the US Army. That day, the al-Hilla General Teaching Hospital treated 109 injured civilians, including 30 children.[119] According to local elders, the cluster munition strike and its resulting duds had killed 38 civilians and injured 156 more by September 2003.[120] Ambulances could not enter certain areas at night to evacuate civilians wounded during the attack because their drivers feared running over unexploded submunitions in the dark; the next morning additional injured civilians were taken to the hospital.[121]

Basra

Three neighborhoods in the southern section of Basra suffered dozens of civilian casualties as a result of UK ground-launched cluster munitions. A March 23, 2003 strike on Hay al-Muhandissin al-Kabru wounded `Abbas Kadim, 13, while he was throwing out the trash. `Abbas suffered injuries to his bowel and liver, and a piece of shrapnel remained lodged near his heart.[122] Later that same day about 2.5 kilometers northeast, in the neighborhood of al-Mishraq al-Jadid, submunitions from an attack killed Iyad Jassim Ibrahim, 26, while he was sleeping in the front room of his home. Ten relatives sleeping throughout the home also suffered injuries.[123] Two days later, on March 25, the United Kingdom launched a cluster munition strike on the neighborhood of Hay al-Zaitun, east of al-Mishraq al-Jadid. Jamal Kamil Sabin, 25, was crossing a bridge with his family when a submunition exploded, and he lost his leg. Zainab Nasir `Abbas, Jamal’s pregnant wife, and Jabal Kamil, Jamal’s nephew, both sustained shrapnel injuries to their legs.[124]

Cluster Munition Strikes in the Iraq Air War

In three weeks from March 20 to April 9, 2003, US and UK air forces dropped more cluster munitions in Iraq than they did in Afghanistan in six months. The number of air-dropped cluster munitions used during this period represented 4 percent of the total number of air-delivered weapons used by Coalition forces. In targeting and technology, the US Air Force demonstrated that it had learned many of the lessons from Yugoslavia and Afghanistan, but its track record was far from perfect.

The US Air Force dropped fewer cluster munitions in or near populated areas, and Human Rights Watch found only isolated cases of air-dropped cluster munitions in Iraqi cities. As a result, civilian casualties from such weapons were limited. When the US Air Force did not take care to avoid populated areas, however, cluster munitions caused casualties. In April, it dropped a CBU-103 on a girls’ primary school in al-Hilla, killing the school guard, Hussam Hussain, 65, and neighbor Hamid Hamza, 45, and injuring 13 others.[125]

The US Air Force also strove to reduce the threat to civilians from cluster munition strikes through improved technology. The guided CBU-103 with WCMD represented 68 percent of the total number of reported air-dropped cluster munitions used by the United States and probably contributed to the low number of civilian casualties in urban strikes. The Air Force also dropped 88 of the new CBU-105, a sensor fuzed weapon. Despite this progress, the US Air Force continued to deploy outdated cluster munitions, including the Vietnam-era CBU-99 Rockeyes, while the United Kingdom dropped variants of the BL-755s.[126] Furthermore, the CBU-103 is not a precision-guided weapon and has a broad area effect, so, like all cluster munitions, it is not safe for use in or near populated areas.

Aftereffects

Iraq was no exception to the predictable aftereffects of cluster munition use. Months after major fighting ended, submunitions continued to maim and kill civilians. US estimates of dud rates for the various types of submunitions used in the conflict range from 2 percent to as high as 23 percent, depending on the type of submunition and test conditions.[127] Ground-launched submunitions were the overwhelming cause of post-conflict civilian casualties.

Al-Hilla, subjected to intense US cluster munition strikes during major combat operations, exemplified the lasting effect of submunition duds. Dr. Sa`ad al-Falluji of the al-Hilla General Teaching Hospital recorded 221 injuries from duds in April 2003 and another 32 from May through August 2003.[128] Even during major hostilities, civilians were at risk from unexploded submunitions. On March 26 in the village of al-Kifl, south of al-Hilla, 13-year-old Falah Hassan lost his right hand and suffered full-body shrapnel wounds from an unexploded DPICM.[129] Falah’s mother suffered injuries to her abdomen, uterus, and intestines as a result of the explosion.[130] The situation caused by UK submunitions in Basra and the surrounding areas was similar to that in al-Hilla. Duds from a strike landed on civilian roofs in the Kam Sabil district of Basra. One 9-year-old girl picked up a submunition that exploded and killed her and injured her pregnant mother and 18-month-old brother.[131]

Air-dropped cluster munition also contributed to post-conflict civilian deaths and injuries. The US Air Force dropped cluster munitions on a date farm in Hay Tunis, Baghdad, that was used to hide military vehicles, a legitimate military target. Across the street from the farm, however, were densely populated civilian areas. Days after the April attack, Hussam Jasmi, 13, and Muhammad Mun`im Muhammad, 14, cousins who lived near the date farm, stepped on a BLU-97 submunition that ripped off their legs. Both boys ultimately died from their injuries.[132] While the US military cleared the area on May 13, Human Rights Watch still found submunitions later that same week.

As was the case in Afghanistan, submunitions disrupted agricultural activity. Human Rights Watch found contaminated fields in villages around al-Hilla, al-Najaf, al-Falluja, and Agargouf. The civilian casualties and socioeconomic harm caused by cluster munitions in Iraq were a foreseeable result of the known flaws of cluster munitions.

Coalition soldiers found themselves in a dangerous position when they encountered submunitions during military operations. On the first night of the war, a convoy of UK military vehicles unwittingly entered a cluster munition field near the Kuwait border and spent half an hour trying to escape the area safely.[133] Members of that convoy sustained no injuries from the field of duds, but by May 2004 unexploded submunitions had killed at least five Coalition members. Several US military officers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they felt uncomfortable using weapons that produced so many unexploded submunitions. Commanding officer Col. David Perkins commented, “We had concerns about unexploded ordnance…. It’s a constant consideration. What are the second or third effects?”[134] An after action report by the Third Infantry Division asked if the DPICM was a “Cold War relic” and described submunitions as “losers.”[135] Submunitions do not differentiate between civilians and military personnel and, therefore, are a risk to both groups.

Lebanon/Israel

Both Israel and Hezbollah used cluster munitions in their conflict in 2006. Israel’s use dwarfed that of Hezbollah and shocked the world, due to the number of cluster munitions fired, the timing of attacks, and the location of strikes. It also showed that high-tech cluster munitions could not prevent the humanitarian effects inherent to the weapons. Hezbollah’s use of cluster munitions was much more limited, but it highlighted that, even in limited numbers, cluster munitions are deadly to civilians and that the spread of such weapons to non-state armed groups is dangerous.

Israel’s Use in Lebanon[136]

Over the course of its 34-day war with Hezbollah in July and August 2006, Israel fired cluster munitions containing an estimated 4.6 million submunitions into south Lebanon, more submunitions than were used in any conflict after the 1991 Gulf War.[137] The total represented about 13 times what NATO dropped on the former Yugoslavia, more than 15 times what the United States used in Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002, and more than twice the number used by Coalition forces in Iraq in 2003. The level and density of unexploded submunition contamination was also far worse than anything found after those wars, and unexploded submunitions caused more than 200 civilian casualties.[138]

During the 2006 war, Israel seemed to ignore the lessons of previous conflicts and demonstrated that the risk of large-scale, indiscriminate use of cluster munitions remained. Its use of the weapon in south Lebanon was notable not only because of its scale but also because of the timing and location of strikes. Furthermore, advanced technology did not mitigate the threat to victims.

Israel carried out about 90 percent of its cluster munition strikes after the UN Security Council passed a ceasefire resolution on August 11, but before it took effect at 8 a.m. on August 14.[139] A witness said, “it started raining cluster bombs” over the last days of the war,[140] and one Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldier commented that “in the last 72 hours we fired all the munitions we had, all at the same spot, we didn’t even alter the direction of the gun.”[141] These attacks suggest a disregard for civilian life because the military advantage of using so many cluster munitions at such a late date is limited.

Another disturbing feature of the war was the IDF’s widespread use of cluster munitions in populated areas. Israeli forces dropped cluster munitions in the middle of towns and villages, contaminating at least 4.3 million square meters of “urban” areas.[142] In the first week after the conflict, Human Rights Watch visited 30 population centers, each littered with unexploded submunitions. In October 2006, Human Rights Watch returned to Lebanon, revisiting some villages and visiting 12 new ones. Again, each was littered with submunition duds.

The IDF acknowledged the use of cluster munitions in “built-up areas” but said use was only made “against military targets where rocket launches against Israel were identified … after taking steps to warn the civilian populations.”[143] The scope of the cluster munition strikes, however, begs the question of whether there were discrete military objectives for each cluster munition strike. The United Nations has estimated that the total area in Lebanon contaminated with cluster munition remnants was about 49 million square meters.[144] Furthermore, individual Israeli soldiers contradicted the claim that the IDF took care to avoid civilian harm; at least one soldiers reported that they were directed to “flood” areas with cluster munitions.[145] The IDF’s blanket use of cluster munitions in and near population centers again suggests that the IDF did not take sufficient care to avoid the loss of civilian life.

The IDF used five main types of ground-launched and air-dropped submunitions, but the most notable was the widely touted M85 with a self-destruct device.[146] As discussed in Chapter 1, the submunition reportedly had a 1.3 to 2.3 failure rate in testing conditions, which led many military experts to view it as the solution to the problems of cluster munitions. Deminers and independent researchers, however, documented a failure rate around 10 percent, showing that the technical preventative measure had failed.[147]

The scale and nature of Israel’s cluster munition use in Lebanon led to international outcry and multiple investigations. In reports based on two missions to Lebanon, the United Nations criticized Israel’s use as “inconsistent with principles of distinction and proportionality.”[148] The United States halted a transfer of M26 cluster munition rockets to Israel and found Israel may have violated classified agreements in its use of US-manufactured cluster munitions in populated areas.[149]

Israel initially defended its actions stating that the IDF “does not deliberately attack civilians and takes steps to minimize any incidental collateral harm by warning them in advance of an action, even at the expense of losing the element of surprise.”[150] Shortly thereafter, however, an IDF operational inquiry revealed that cluster munitions were not always used in accordance with IDF regulations permitting use only in open and unpopulated areas.[151] In a report released in 2008, Israel’s Commission to Investigate the Lebanon Campaign in 2006, also known as the “Winograd Commission,” determined that “[t]he cluster bomb is inaccurate, it consists of bomblets that are dispersed over a large area, and some of the bomblets do not explode [on impact] and can cause damage for a long period afterward.” The Commission recommended that non-military officials help assess future use of cluster munitions under international law.[152]

Cluster Munition Strikes

Blida was the best documented case of casualties during a cluster strike. On July 19, 2006, at around 3 p.m, the IDF fired artillery-launched cluster munitions on the town in south Lebanon. A strike killed Maryam Ibrahim, 60, inside her home. Submunitions also entered Ibrahim’s basement, which was being used as a shelter by two families, and injured 12 civilians, including seven children.[153]

The total number of civilians killed or injured at the time of attack is not known. Hospitals were too busy during the war to record the causes of casualties. Civilians returning after the war found dead bodies of family members, friends, and neighbors but could not determine the cause of death. Fortunately, many civilians had fled their homes before the barrage of cluster munitions on the final three days of the war, which reduced the number of casualties during strikes.

After the Ceasefire

The fact that so many civilians fled led to a relatively small number of strike casualties, but there was a great number of post-conflict deaths and injuries. Deminers estimated an average failure rate of 25 percent, with up to 70 percent in some locations.[154] These exceptionally high failure rates and the large number of cluster munitions used left south Lebanon saturated with duds. Returning after the ceasefire, civilians found their villages, homes, and fields littered with unexploded submunitions.

Civilians first became post-conflict casualties of the war while trying to rebuild their lives and homes after the ceasefire. Salimah Barakat, a 65-year-old tobacco farmer in Yohmor, remained in her home during the war to take care of her two disabled children. She reported hearing cluster munitions fall during the night on the last days of the war. On August 14, the day of the ceasefire, while moving a large rock blocking the stairs to her home, Barakat set off a submunition that lodged shrapnel into her chest, lower abdomen, and right arm. In October 2006, after recovering from her wounds, Barakat returned to her tobacco fields and olive grove to harvest the crops, but even her backyard remained littered with submunitions.[155]

As in previous conflicts where cluster munitions were used, children became frequent victims of the small, curious, and deadly submunitions littering Lebanon. On October 22 in the village of Halta, Rami `Ali Hassan Shebli, 12, died from a submunition explosion. Rami’s 14-year-old brother, Khodr, was throwing pinecones at Rami in play. When Rami picked something up to throw back at his brother, a neighbor boy noticed Rami was holding a submunition and yelled at him to put it down. Rami was reaching behind his head to throw the submunition away when it exploded in his hand killing him and wounding Khodr.[156] Human Rights Watch arrived at the scene shortly after the incident, and during the hour it visited the site, it observed the Lebanese Army clear 15 unexploded submunitions from the family’s yard.

Resuming agricultural activities became one of the most dangerous activities in post-conflict Lebanon since fields and groves ready for harvest were littered with duds. By the anniversary of the conflict, submunitions had injured at least 50 civilians and killed at least 5 others engaged in agricultural activities.[157] About 70 percent of household incomes in south Lebanon come from agriculture,[158] and those who decided not to risk farming the contaminated fields protected their lives but lost their livelihoods.

Economic need drove some civilians to put themselves even more directly at risk from cluster munitions. Certain civilians decided they were unable to wait for professional clearance teams and began the dangerous process of clearing submunitions themselves. Many were injured.[159] Gathering scrap metal for sale also led to civilian casualties.[160] The aftereffects of cluster munitions in Lebanon followed the pattern established in previous conflicts: after a war is finished, cluster munitions continue killing children and other civilians carrying out the activities of daily life.

Tebnine Hospital

One of the more startling strikes of the war did not result in any civilian casualties. On August 13, 2006, IDF cluster munitions struck the Tebnine Hospital, a facility protected by international humanitarian law. Taking refuge inside the hospital were approximately 375 civilians and military non-combatants including medical staff and patients. Outside, submunitions covered the streets surrounding the hospital, the roof of the hospital, and the receiving area for ambulances. The threat trapped people inside the hospital until a bulldozer cleared the area.[161]

Hezbollah’s Use in Israel[162]

Israel was not alone in launching cluster munitions during the 2006 conflict. Hezbollah fired at least 118 Chinese-made Type-81 cluster munitions into northern Israel.[163] While Hezbollah’s use of cluster munitions did not compare to Israeli use in scale, it demonstrated that even when used in limited numbers, cluster munitions are too dangerous to civilians to warrant their use. It also highlighted the risks of allowing proliferation to non-state armed groups.

Type-81 122mm cluster munition rockets carry 39 Type-90 (also known as MZD-2) submunitions. Each submunition resembles a DPICM and shoots out hundreds of steel spheres with deadly force. It was the first time use of this type of cluster munition had been documented.[164]

Israeli police officials reported that Hezbollah’s cluster munitions caused one death and 12 injuries in all.[165] Jihad Ghanem, a 43-year-old factory manager, told Human Rights Watch that on July 25, 2006, a cluster munition landed among three homes belonging to his family in the western part of Mghar. The attack injured his son Rami, 8; his brother Ziad, 35; and his sister Suha, 33. Other villagers reported that the rocket that hit the Ghanem’s property was part of a volley of some 10 to 12 rockets that landed in or near Mghar that afternoon.[166]

Georgia[167]

During their August 2008 conflict over the breakaway region of South Ossetia, Russia and Georgia each used cluster munitions. As in past conflicts, cluster munitions were used in or near many populated areas, and they caused at least 70 civilian casualties during and after the war. The international community widely criticized Russia and Georgia. Each state criticized the other’s use of cluster munitions as “inhuman” or “inhumane,” while still defending its own right to use the weapon.[168]

This instance of cluster munition use occurred against the backdrop of an international movement to ban the weapon. Less than three months earlier, 107 states had agreed to adopt the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Neither Russia nor Georgia took part in the process leading to the new treaty, but their use provided a fresh example of the humanitarian harm caused by the weapons and of how such use was becoming increasingly at odds with the strong, emerging international consensus that cluster munitions should be categorically prohibited.

Use of cluster munitions during the conflict over South Ossetia also exemplified how problems with the weapons occur regardless of the parties involved. Russia, a producer, stockpiler, exporter, and past user of cluster munitions, is thought to possess hundreds of millions of submunitions of various types. In this case, it used both air-dropped and ground-launched models delivered from bombs, rockets, and missiles. Georgia, neither a producer of cluster munitions nor a known past user, has what is thought to be a small stockpile. During this conflict, it used a ground-launched model imported from Israel, which it claimed was the only active type of cluster munition it possessed. Despite their contrasting military profiles and different histories with the weapon, Russia and Georgia produced the same results with their use of the weapons: civilian casualties at the time of attack and afterwards. The August 2008 conflict showed that whoever the user, and whatever the type used, cluster munitions pose unacceptable risks to civilians and must be eliminated.

Finally, the effects of the apparent failure of Georgia’s cluster munitions to reach their target served as a reminder of the harm that cluster munitions can cause when they do not work properly.

Russian Use

Russia used cluster munitions in or near nine towns and villages in the Gori-Tskhinvali corridor south of the South Ossetian administrative border.[169] Although Russia repeatedly denied using cluster munitions in this conflict,[170] Human Rights Watch concluded based on physical and testimonial evidence found in the field that the incidents described below were attributable to the actions of Russian forces.[171] Russia caused 58 civilian casualties with three types of cluster munitions: RBK series bombs carrying either 60 or 108 AO-2.5 RTM submunitions, 200mm surface-to-surface Uragan rockets carrying 30 9N210 submunitions, and the surface-to-surface Iskander (or SS-26) missile that carries an unknown model of submunition.[172]

Cluster Munition Strikes

Human Rights Watch found that Russian forces fired many of their cluster munitions into populated areas of Georgia, killing at least 12 civilians and injuring 46 in attacks on Gori, Ruisi, and Variani.[173] Many witnesses said Georgian troops or vehicles, the most likely cluster munition targets, were not in the immediate area at the time of the strikes, and in no case did Human Rights Watch find evidence of enemy units at the site of the attack.

The incident in the city of Gori exemplifies the nature of Russia’s use of cluster munitions and the human suffering it caused. According to an investigation initiated by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Russia attacked Gori with an Iskander missile containing cluster munitions on August 12, 2008.[174] The attack hit the main square of the city as a crowd of locals and journalists was gathering. Among those killed in the strike was Dutch RTL cameraman Stan Storimans. The Dutch government investigation into the circumstances surrounding Storimans’s death determined that Georgian troops had fled Gori by August 12, calling into question whether the attack was targeted at a specific military objective. Human Rights Watch’s research, which focused on this incident from the perspective of Georgian civilians, independently reached the same conclusions as the Dutch investigation. Keti Javakhshvili, 24, was walking to a neighbor’s house for bread when the attack came.[175] Her doctor told Human Rights Watch that she suffered massive injuries to her liver, stomach, and intestines as well as hemorrhagic shock. He said it would require multiple procedures to repair all the damage and months to convalesce.[176] GorMed Hospital, the civilian hospital in Gori, reported that the attack killed six civilians and injured 24.[177]

Aftereffects

Human Rights Watch did not document any casualties from Russian duds after the time of attack, but it found many unexploded submunitions, which indicated that the potential for future injuries remained. At one site Human Rights Watch visited in Ruisi, a Norwegian People’s Aid deminer leading a clearance team estimated the 9N210 submunitions in his 200,000 square meter area of operation had a 35 percent dud rate.[178] In Variani, Norwegian People’s Aid cleared 107 submunitions.[179]

The presence of Russian duds also caused significant socioeconomic harm after the conflict. The economy in the region relies heavily upon agriculture, and unexploded submunitions impeded many Georgians’ ability to tend their farms and livestock and earn a living. Nukri Stepanishvili, a 44-year-old farmer in Variani who found unexploded submunitions in his home and cabbage patch, said, “I haven’t harvested. I won’t until there is some clearance.” He explained that he had already lost some of his crops and feared losing many more.[180] While some of the Russian strikes on fields outside of populated areas may have been aimed at Georgian military targets, the Russian forces’ decision to use cluster munitions with high dud rates led to significant post-conflict challenges for civilians.

Georgian Use

Although Georgia initially denounced Russia’s use of cluster munitions while failing to admit its own,[181] on September 1, 2008, it publicly acknowledged that from August 8 to 11 it used cluster munitions “against Russian military equipment and armament marching from Rocki [sic] tunnel to Dzara road.” It insisted that its cluster munitions “were never used against civilians, civilian targets and civilian populated or nearby areas.”[182] Human Rights Watch, as well as Georgian military deminers and international demining organizations, however, found Georgian submunitions farther south in a number of populated areas. Human Rights Watch researchers gathered evidence of Georgian submunitions in or near a band of nine villages in the north of the Gori district.[183]