Map of China

© 2013 Human Rights Watch

Summary

The school near us wouldn’t enroll him … why wouldn’t they let us go to school? Everyone is entitled to nine years of compulsory education, right?

—Mother of Chen Yufei, Henan Province, January 2013.

The mother of Chen Yufei tried hard to find a school for her son, a nine-year-old boy with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and an intellectual disability. When Chen was 7 she brought him to a nearby school, but the principal would not let him enroll because he would “affect other children.” Reluctant, Chen’s mother turned to special education schools, but she could not find one: the district in which they live did not have one. Eventually she got Chen accepted in a special education school in another district — after two years and a hefty bribe. She still bitterly resents this experience, as she believes her son would make much better progress if he were in a mainstream school.

Across China, children and young people with disabilities confront discrimination in schools. This report documents how mainstream schools deny many such children admission, ask them to leave, or fail to provide appropriate classroom accommodations to help them overcome barriers related to their disabilities. While children with mild disabilities are in mainstream schools where they continue to face challenges, children with more serious disabilities are excluded from the mainstream education system, and a significant number of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch receive no education at all.

Internationally, there is a growing recognition that “inclusion” — making mainstream education accessible for children with disabilities — is a key element in realizing the right to education. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the most recent international human rights treaty, mandates that state parties “ensure an inclusive education system at all levels.”

By ratifying the CRPD in 2008, the Chinese government made a commitment to “the goal of full inclusion.” Yet it has no clear and consistent strategy to achieve that goal. It continues to devote too few resources to the education of students with disabilities in mainstream schools while at the same time actively developing a parallel system of segregated special education schools. Inclusive education is not just a legal obligation, and it benefits not only students with disabilities — a system that meets the diverse needs of all students benefits all learners and is a means to achieve high-quality education and more inclusive society. While an inclusive education system cannot be achieved overnight, the Chinese government’s current policies and practices raise questions about the extent of its commitment to do so.

The Chinese government has taken important steps to promote the rights of people with disabilities. Internationally, it was supportive of the development and adoption of the CRPD. Domestically, it passed the Law on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities (LPDP), which outlines the rights of people with disabilities as well as a number of regulations on disability. It has pledged greater funding for the education of people with disabilities and has taken steps such as waiving miscellaneous school fees to facilitate their access to education.[1]

However, a closer look at education for people with disabilities reveals a grimmer picture. According to official statistics, over 40 percent of people with disabilities are illiterate and 15 million live on less than one dollar a day in the countryside. The Chinese government has an impressive record in providing primary education for children without disabilities, achieving near-universal compulsory education for such children. But according to official statistics, the rate for children with disabilities is much lower: about 28 percent of such children should be receiving compulsory basic education but are not.

The Chinese government has often been considered a model in reaching the Millennium Development Goal regarding the provision of primary education to all children — but the picture dramatically changes if the data are disaggregated to focus on enrollment rates for children with disabilities. Bars to enrollment, expulsion from schools, and lack of adequate support in mainstream schools, as well as lack of information about and trouble reaching special education schools, are the main reasons for the enrollment gap.

Discrimination against children and young people with disabilities permeates all levels of education in the mainstream system. Schools sometimes deny enrollment outright, but they are often more subtle, convincing the parents to take their children out of the schools with a variety of arguments. Schools sometimes place conditions on parents, such as requiring that they accompany their children to and in school every day, before they allow their children to study in the schools. While Chinese laws and regulations contain provisions prohibiting discrimination on the basis of disability, the provisions are often vague, fail to precisely define discrimination, and do not outline effective redress mechanisms.

The Chinese government also does not have a clear policy on “reasonable accommodation” in mainstream schools — defined in the CRPD as “necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate or undue burden.” In interviews with Human Rights Watch, parents told of carrying their children up and down stairs to classrooms or bathrooms located upstairs several times a day. Students with hearing impairments said they could not follow along because the teachers walk around while teaching and do not to provide written notes, and there is no sign language instruction in most schools. They told us that students who are blind or who have limited vision are not provided with magnified printed materials or tests. Some mainstream schools exclude students with disabilities from the examination system; they do not get graded and their progress is not otherwise evaluated. In some rural areas, the government’s policy of consolidating mainstream schools in recent years has had a negative effect on students with disabilities, as schools to which they are assigned are further away and provide no transportation.

While some teachers and principals in mainstream schools make Herculean efforts to provide reasonable accommodation to students with disabilities — out of the “goodness of their hearts,” as one interviewee put it — such support is not institutionalized. In both policy and practice, the mainstream education system is set up in such a way that the teacher’s focus is on students without disabilities; it is the child with a disability who is expected to adapt to the system.

Teachers find that the burden of supporting students with disabilities rests entirely on their shoulders, as they are provided with little support to ensure reasonable accommodations in the classrooms. There is no staff support to assist the teachers, who often have to teach large classes of 30 to 60 students. Training for teachers and administrators in mainstream schools is limited and little funding goes to ensure that such schools are adequately resourced to educate these students. There is also little incentive for teachers to provide support to students with disabilities because doing so does not impact their performance ratings or prospects for promotion.

As a result, many students with disabilities literally find themselves sitting in classrooms without being able to follow the curriculum. This leads to failing performance and declining confidence, which only reinforces the effects of existing discrimination. China calls its scheme for students in the mainstream education system “study along with the class”; because of the obstacles such children face, it has come to be jokingly referred to as “sit along with the class” or “muddle along with the class.” A large percentage of students with disabilities eventually drop out of school or move to special education schools. Once in the special education system, there is little hope of their being able to cross back to the mainstream school system. Families with children with disabilities should have a choice in selecting the most appropriate educational settings for their children, but currently do not have a meaningful choice.

In China, special education schools have fulfilled an important function in providing access to education for children with disabilities, and they are generally well-resourced with both teachers and equipment. However, special education schools separate children with disabilities from those without, which in many cases is not what the children or their parents want. Special education schools are fewer in number and typically farther away than mainstream schools and parents often know little about them, deterring parents from sending their children to them. And they often require the removal of children from their families and communities and placement in a residential institution from a young age. Moreover, many students with severe disabilities are excluded even from special education schools.

Children with disabilities rarely stay in school beyond junior middle school, and for those who aspire to do so, choices are limited. The Chinese government maintains a system of physical examinations for secondary school students who wish to enter mainstream institutions of higher education. During this process, people with disabilities are required to declare their disabilities, and the results of the medical exams are sent directly to the universities. The government also has guidelines advising higher education institutions to bar or restrict access to students with what they refer to as certain physical and mental “defects.” In addition, students who are blind have very limited access to mainstream universities, as the government fails to readily provide Braille or electronic versions of the gaokao, the university entrance exam.

While there are vocational schools for people with disabilities as well as higher education institutions in the special education system, they tend to focus on training for skills and professions that are traditionally reserved for people with disabilities. For example, the blind are trained in massage therapy and the hearing impaired are trained in visual arts. Students with disabilities who aspire to other professions face daunting challenges. This includes the education profession itself: bureaus of education typically prohibit the hiring of teachers with certain disabilities.

Parents play a pivotal role in determining whether a child with disabilities is brought to school and whether the child can overcome the barriers in the system. However, many parents interviewed by Human Rights Watch lacked essential information about their children’s educational rights and options. While almost all of the children we interviewed had disability cards issued by the China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF), a quasi-governmental disability body, the CDPF has not effectively reached out to parents about their children’s education, let alone helped them identify and remove barriers in mainstream schools. The CDPF and the Ministry of Education, which oversees education, also fail to proactively address discrimination and ensure that reasonable accommodation is provided in mainstream schools.

Key Recommendations

Human Rights Watch calls on the Chinese government to make an explicit commitment towards a truly inclusive education system by revising existing laws and regulations and by drawing up a clear strategic plan towards such a goal. The government should formulate a policy of reasonable accommodation consistent with international law, set up a mechanism to monitor and provide effective redress in cases of discrimination, and develop outreach programs to support parents so that they are informed of their children’s rights and education options. Failure to ensure access to inclusive and quality education is not only a violation of human rights, but also increases burden on families and incurs economic, social, and welfare costs.

More specifically, the Chinese government should:

- Revise the Regulations on the Education of People with Disabilities to bring them in line with the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities. Specifically, the new regulations should state clearly that the Chinese government’s overarching goal in the education of people with disabilities is full inclusion at all levels of education and set forth specific actions authorities should take to ensure reasonable accommodation of students with disabilities in mainstream schools.

- Develop a time-bound, strategic plan to move towards an inclusive education system that delivers quality education, with specific indicators to measure access to education for children with disabilities.

- Immediately repeal the Guidelines for the Physical Examination of Students in Recruitment for Ordinary Higher Level Educational Institutions because they allow disability-based discrimination in higher education.

- Develop guidelines for the effective evaluation of students with disabilities studying in mainstream schools and ensure that their educational progress is reflected in the performance assessment of their teachers and schools.

- Provide financial and other resources, including adequately trained staff, to mainstream schools so that they can ensure the provision of reasonable accommodation to pupils and students with disabilities.

- Establish an independent body made up of independent disability experts and representatives of children with disabilities and their parents to monitor the school system’s compliance with relevant laws and regulations and to receive complaints about discrimination and lack of reasonable accommodation at mainstream schools. The body should be charged with making recommendations for reform.

Detailed recommendations can be found at the end of this report.

Methodology

This report is based on 62 interviews conducted in 12 provinces in China between December 2012 and May 2013. Forty-seven of those interviews were with children[2] and young people with disabilities or their parents. Of the 47, 38 were under age 18 (“children,” as defined in international law) and 9 were over age 18; 12 were out of school (6 had never been to school while six had dropped out) while 35 were in school (18 in mainstream schools and 17 in special education schools). We interviewed 30 of the 47 in the presence of their parents or grandparents. The rest of our 62 interviews were advocates for people with disabilities, educators, government officials, and academics.

All of the children and young people we interviewed were or should have been in school after the Chinese government’s 2008 ratification of the CRPD.

Human Rights Watch interviewed children and young people with a range of disabilities, including physical, sensory (hearing and visual), speech, intellectual, and mental disabilities. Some of the interviewees had multiple disabilities. Almost all of them had disability cards issued by China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF). These cards, which use the classifications prescribed in Chinese law, identify the holders as having the following disabilities: visual, hearing, speech, physical, intellectual, mental, multiple disabilities, and “other.” [3] Parents used these categories when describing their children’s disabilities, but some pointed out that the categories were inaccurate or did not capture the full range of their children’s disabilities. Since Human Rights Watch was not in a position to identify the interviewees’ disabilities, we have used the CDPF classifications in this report.

In each interview, Human Rights Watch explained the purpose of the interview, how the interview materials would be used and distributed, and sought the participant’s permission before the discussions started. Interviewees were told that they could terminate the interviews any time they wished, or refuse to answer any questions. All the interviews were conducted in Chinese but some required interpretation from the regional dialect or sign language into Mandarin. Human Rights Watch ensured that when interviewing these children and young people, the way we asked the questions was appropriate for their age and sensitive to their disabilities. No interviewee received financial or other compensation in return for interviewing with us.

We were also careful to protect all interviewees’ identities and have replaced their real names with pseudonyms in the report.

Because the Chinese government does not allow independent nongovernmental organizations to conduct human rights research in China, it was difficult for Human Rights Watch to obtain interviews with people in their official capacity. We were only able to interview a handful of government officials, academics, and educators and administrators in public schools. Despite these restrictions, we believe the findings of this report are nationally representative as our interviewees were drawn from 12 Chinese provinces and our analysis is based on national laws and regulations.

For the report, Human Rights Watch also consulted a number of international disability experts. We also reviewed relevant English- and Chinese-language domestic and international press reports, official documents, UN documents, NGO reports, and academic articles. Our findings are generally consistent with those set forth in these other sources.

Background

Disability in China

According to official Chinese sources, an estimated 83 million people in China — 6.3 percent of the population — have disabilities.[4] This is far below the global disability prevalence rate estimated by the World Bank in 2011, which is 15 percent, and is likely an underestimate.[5] If the World Bank prevalence rate is used, the number is 200 million.

As is often the case in other countries, people with disabilities in China are the country’s “largest minority.”[6] In China, over 40 percent of people with disabilities are illiterate and 15 million live under one dollar a day in the countryside, according to official figures.[7] The largest group is people with physical disabilities, with a population of 25 million, followed by those with hearing, multiple, visual, mental, intellectual, and speech disabilities.[8] There is currently no data on those with autism.[9] The government reports that 75 percent of people with disabilities live in rural areas.[10]

The Chinese government has presented itself as a champion of people with disabilities both domestically and internationally. It passed the LPDP in 1990 and issued administrative regulations including the Regulations on the Education of People with Disabilities (REPD)[11] in 1994; these protect the rights to education, employment, and accessible environments for people with disabilities.[12] Internationally, the Chinese government has supported major events concerning people with disabilities, notably including the first international NGO summit on disability held in Beijing in 2000.[13]

In 1988 the Chinese government established the China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF) under the leadership of Deng Pufang, who has paraplegia and is the son of the late Deng Xiaoping, China’s political leader in the 1980s.[14] According to its constitution, the CDPF aims to “represent, serve and manage”[15] people with disabilities. Although the government often refers to the CDPF as a nongovernmental organization, it acts under the direct supervision of China’s chief administrative authority, the State Council. It has a nationwide network “reaching every part of China” and 80,000 full-time workers, with its headquarters in Beijing.[16] It is responsible for a wide range of matters relating to people with disabilities including education, employment, rehabilitation, culture, sports, advocacy, publications, and residential care.

The CDPF is mandated to assist the Ministry of Education in “the development and implementation of education programs,” carrying out vocational training, and promoting and researching the use of Braille and sign language. [17] At the local level, it conducts home visits, provides financial aid to students, subsidizes assistive devices, collects data on people with disabilities, and operates rehabilitation centers for children with disabilities. [18] Despite its laudable mandate, however, a number of independent Chinese disability activists have accused the CDPF of corruption, misallocation of funds, hindering their work and threatening them, and failing to represent and fight for the rights of people with disabilities. [19]

In addition to the CDPF, a number of international and domestic organizations provide services to people with disabilities in China, and a handful of them focus on advocating for the rights of people with disabilities. Most prominent among the latter are the Beijing Yirenping Center and the Enable Disability Studies Institute. [20] The Chinese government tightly controls freedom of association in China and it is difficult for such organizations to legally register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs. Even if they are allowed to operate, they are closely monitored, sometimes harassed, and at risk of co-optation by the government. [21]

Education of People with Disabilities in China

There are four levels of education in China: pre-school, primary education (ages 6 to 12), secondary education (ages 13 to 18, which includes junior middle school, senior middle school, and vocational school), and higher education (ages 19 to 23). The Chinese government’s policy is to guarantee nine years of free compulsory education, including six years of primary and three years of secondary education. A child starts primary school when they are six years old, though in some areas children can begin school when they are seven.[22]

The Ministry of Education oversees education at all levels in China from pre-school to universities, as well as vocational training schools and special education schools. It is also responsible for drafting legislation on education, developing curriculum and teaching materials, and training and certifying teachers. The allocation of education funding is uneven in China, particularly at the compulsory education level where local governments are responsible for providing adequate resources. This leads to wide gaps between rural and urban areas and between rich coastal and poor inland regions.[23]

The Chinese government currently operates two main systems of education which people with disabilities may attend: mainstream schools and special education schools.[24] In the special education system, students are divided according to type of disability — there are schools for the blind, for the deaf, and for those with intellectual disabilities; some special education schools can accommodate children with multiple types of disabilities.

Special education schools started in China in the 1950s soon after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, providing important access to education for people with disabilities when educational opportunities were otherwise very limited. Schemes for the education of students with disabilities in mainstream schools are called “study along with the class” or “learning in regular class” (LRC). According to Ministry of Education statistics, there were 1,767 special education schools enrolling 398,700 children with disabilities in 2011; that same year mainstream schools provided education to another 225,200 children with disabilities (including via special education classes in mainstream schools).[25] There are also some privately run special education schools or “rehabilitation institutions” that provide education to children with disabilities.

As noted above, CDPF statistics show that about 28 percent of children with disabilities in the compulsory education years do not go to school, but this figure is not entirely reliable because official statistics regarding disability and education from different government agencies are conflicting and inconsistent.[26] Considering that nearly all Chinese children in the general population go to school at this stage, a 28 percent non-attendance rate is an astonishing gap. Among those children with disabilities who are out of school, 80 per cent are in rural areas.[27] In its policies and plans for education the Chinese government has outlined various targets to raise the enrollment rate for children with disabilities.[28] The vision is to raise the rate to match that of children without disabilities, and to raise the rate in rural areas to at least 90 percent enrollment by 2015. While official statistics show steady progress in raising the enrollment rate of children with disabilities since 2007, the government is unlikely to meet these targets unless it addresses the problems documented in this report.

The education of people with disabilities has consequences far beyond childhood — it affects employment opportunities, quality of life, and the extent to which people with disabilities will be able to support themselves and lead independent lives. [29] The failure to include people with disabilities in education and later in employment has important implications not only for these individuals and their immediate families but also the wider society and the economy. According to a 2006 study by the International Labor Organization, China loses as much as US$ 111.7 billion, or about 3 per cent of its GDP, as a result of lost productivity stemming from excluding persons with disabilities from the workforce. [30]

Chinese Government Obligations

The Chinese government is party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the International Convention on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the CRPD. The ICESCR and CRC guarantee everyone the right to education by making primary education compulsory and free, secondary education available and accessible, and higher education accessible on the basis of capacity.[31] The ICESCR also obliges governments to ensure that the material conditions of teaching staff will be continuously improved.[32] States are also obliged to take measures to encourage regular attendance by children at schools and the reduction of child drop-out rates.[33] With respect to children, states are required to undertake such measures to the maximum extent of their available resources.[34]

Specifically, children with disabilities should receive and have effective access to education.[35] The CRPD articulates in greater detail the right to education for people with disabilities: they enjoy this right “without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity,” they have a right to “an inclusive education system at all levels,” and they have a right to learn skills so that they can participate within their community fully and equally.[36]

China’s Compulsory Education Law (CEL) stipulates that “all children” who have reached the age of six must go to school.[37] The LPDP explicitly guarantees the right to education for people with disabilities.[38] The LPDP stipulates that the government’s priorities are to ensure that students with disabilities have access to compulsory education and to develop vocational training, noting that “efforts shall be made” to implement education at pre-school as well as higher education levels.[39] The Regulations on the Education of Persons with Disabilities (REPD) spell out in greater detail how the education of people with disabilities is to be provided at all levels as well as how teachers of people with disabilities are to be certified, trained, and remunerated. In addition to these laws and regulations, the Ministry of Education also issues rules and normative documents on the education of people with disabilities.[40] Finally, the State Council has issued long-term plans that give broad outlines of the education of people with disabilities from pre-school to vocational training and higher education levels and makes commitments to teacher training and subsidizing students with disabilities.[41]

Non-discrimination and Equal Access

International law prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability, which is defined under the CRPD as any “distinction, exclusion or restriction…which has the purpose or effect of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal basis with others, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.”[42] In terms of education, the CRPD requires that “people with disabilities are not excluded from the general education system on the basis of disability, and that children with disabilities are not excluded from free and compulsory primary education, or from secondary education, on the basis of disability.”[43] This obligation of non-discrimination applies both to public as well as private actors, and at all levels of education, including higher education and vocational training.[44]

The Chinese Constitution proclaims that all Chinese citizens are “equal before the law.”[45] The LPDP also prohibits “discrimination on the basis of disability.”[46] These are statements of principle, however, and neither the Constitution nor the LPDP define discrimination, outline consequences for discrimination, or provide guidance on how to prove discrimination in court.[47]

The proposed amendments to the REPD, released by the Ministry of Education in February 2013 for public comment, offer a small improvement in article 48, which spells out a number of consequences for discrimination, including “sanctions” by educational authorities and “apologies and compensation” to the offended party. Such consequences apply only in cases of “obvious discrimination,” but there is no definition of discrimination or details about the kind of discrimination that should be considered “obvious” in the proposed amendments.

Inclusive Education

The CRPD requires states to make education inclusive at all levels.[48] The CRC also stipulates that education of people with disabilities should be conducive to the child’s social inclusion.[49] The Committee on the Rights of the Child, a body of independent experts that monitors treaty implementation and issues general recommendations, has stated that “legislation which compulsorily segregates disabled children in segregated institutions for care, treatment or education”[50] is incompatible with the treaty.

In an inclusive education system, all students learn in the same schools in their communities regardless of whether they are “disabled and non-disabled, girls and boys, children from majority and minority ethnic groups, refugees, children with health problems, working children, etc.” [51] It requires that the system make modifications to the content and methods of education and provide support to meet the diverse needs of all learners. [52] Inclusive education therefore is not only relevant for the education of students with disabilities, but should benefit all children and be “central to the achievement of high-quality education for all learners and the development of more inclusive societies.” [53] Studies have shown that students with disabilities achieve better academic results in an inclusive environment when given adequate support than they do in special education settings. [54]

Inclusive education should be distinguished from two other approaches to educating people with disabilities. One is segregation, where children with disabilities are placed in educational institutions that are separate from the mainstream education system. Another is integration, where children are placed in mainstream schools as long as they can fit in these schools and meet their demands. Unlike inclusive education, integration tends to regard the disabled child rather than the school as the one who needs to change.[55] Inclusion focuses on identifying and removing the barriers to learning and changing practices in schools to accommodate the diverse learning needs of individual students. In China, there is often confusion over the concepts of “integration” (ronghe) and “inclusion” (quanna) by academics and policy makers and the two terms are often used interchangeably.[56]

The affirmation of the right to inclusive education is part of an international shift from a “medical model” of viewing disability to a “social model.” A couple of decades ago, disability was considered a defect that needed to be fixed. Disability today is viewed as an interaction between individuals and their environment, and the emphasis is on identifying and removing discriminatory attitudes and barriers in the environment.[57]

While the CRPD advocates “the goal of full inclusion,” it also states that the primary consideration should be the “best interests of the child.” [58] In some circumstances, such as when an inclusive education system is not yet functional or necessary accommodations cannot be reasonably provided, it may be more effective for the child to be educated in special education settings for part or all of the time. The CRPD emphasizes the voice and choice of children with disabilities. [59] It is important that the government make efforts to ensure mainstream education is inclusive and accessible for children with disabilities, and make special education available so that children with disabilities have meaningful choices.

As mentioned above, the Chinese government is currently operating two main parallel systems of education for people with disabilities: special education and mainstream schools.[60] The two streams exist in parallel and rarely interact. For example, the training of teachers in these two systems is separate: teachers are either trained for the special education system or for the mainstream system. The goals for the two education systems are different — while the mainstream system aims to propel students through the educational ladder and into universities, with a strong focus on succeeding in national academic exams, the special education system mostly focuses on getting students through compulsory education and providing vocational training.

Although the two systems do overlap in some areas, the facts remain that they are separate and parallel and that there are systematic barriers preventing students with disabilities from entering and staying in the mainstream system. Children with disabilities are entitled to attend mainstream schools only if they are “able to adapt themselves to study in ordinary classes”[61] and can “study along with the class.” This is in essence a form of integrated education — it is the students with disabilities who have to adapt to the education system, not the reverse.

In its review of the Chinese government’s compliance with the CRPD in September 2012, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities expressed concern about the “high number of special schools and the State party’s policy of actively developing these schools” and recommended that the government “reallocate[s] resources from the special education system to promote … inclusive education in mainstream schools.”[62] So far, the Chinese government has not taken concrete steps to meet this recommendation. The government’s 10-year education plan, issued in July 2010, includes specific targets and clear timelines for building more special education institutions but no comparable targets and timelines for the education of students with disabilities in mainstream schools. And while funding for special education schools has nearly quadrupled in the past decade, funding dedicated to mainstream schools specifically for the education of students with disabilities has seen little growth; most local governments have not dedicated funding to help mainstream schools implement “learning in regular class” (LRC) schemes.[63]

The government’s proposed amendments to the REPD continue to call for the building of new special education schools, including segregated institutions of higher education. [64] Under the amendments, a new panel of experts will be established to place people with disabilities in either segregated schools or mainstream schools “according to the types of disabilities and their learning abilities” [65] and their “ability to receive an ordinary education.” [66] In other words, the proposed mechanism continues to segregate a category of persons with disabilities from the mainstream school system, and this decision is made by a group of experts without any participation by families with children with disabilities in the process.

Reasonable Accommodation

To realize the right to inclusive education, the CRPD requires states to ensure “reasonable accommodation.” As defined by the CRPD, reasonable accommodation means “necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate or undue burden…to ensure to people with disabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with others of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.”[67] In education, it more specifically means steps that “allow students to get an equal education by limiting as much as possible the effects of their disabilities on their performance,”[68] with the caveat that the steps not impose “significant difficulty or expense” on the government.[69] State parties also have an obligation to ensure that the education of people with disabilities, especially those who are deaf and blind, is provided “in the most appropriate languages and modes and means of communication for the individual.”[70] The CRPD also requires that state parties promote the availability and use of assistive devices.”[71]

Examples of reasonable accommodation include holding classes on the ground floor; providing note-takers; allowing for additional time for note-taking or during exams; priority seating for students to minimize distractions and enable them to see and hear the teachers; providing assistive devices such as magnifying equipment or tape recorders; providing sign-language instructors; reading aloud written materials for students with visual impairments; and structural modifications to schools, such as ramps.[72]

An important part of ensuring reasonable accommodation is training teachers, school administrators, and education officials in methods to support persons with disabilities. According to the CRPD, such training should include “disability awareness and the use of appropriate augmentative and alternative modes, means and formats of communication, educational techniques and materials to support persons with disabilities.”[73] It is crucial that teachers are given adequate support so that they can provide accommodations to students with disabilities.

Relevant Chinese regulations stipulate the establishment of “resource rooms” within mainstream schools and “resource centers” in a given area to provide guidance, equipment, and support to facilitate education for children with disabilities in the mainstream education system.[74] They also stipulate that teacher training institutions include classes on special education and that educational authorities include training in special education at all levels of teachers’ training programs.[75]

While the provision for resource rooms and resource centers is certainly a step in the right direction, any positive effect they might have is hampered by the fact that Chinese laws and regulations do not clearly require that schools provide students with disabilities “reasonable accommodation” as defined in international law. The closest equivalent is in the LPDP requirement that the government provide “special assistance” to people with disabilities so as to “alleviate or eliminate the impact of their disabilities and external barriers and ensuring the realization of their rights.”[76] However, the choice of the phrase “special assistance” suggests that such assistance is out of the ordinary rather than a necessity and a right.

Similarly, the REPD states that mainstream schools should provide “help to [meet] special learning and rehabilitation needs”; and the Education Law and the CEL stipulate that schools should provide “assistance” and “convenience” — the vagueness of the terms again raises questions about whether the accommodations are rights to which students are entitled or favors bestowed by the schools.[77] Another set of government regulations, Regulations on Construction of a Barrier-free Environment, was enacted to “ensure equal participation of persons with disabilities and other members of the community in social life,”[78] but the regulations only refer to general accessibility measures. The proposed amendments to the REPD mention “reasonable accommodations” twice, but provide no definition of the term or examples of the kind of support schools are obligated to provide to students with disabilities.[79] None of the laws, regulations, or the proposed REPD amendments outline any consequences if the government or the schools do not offer such support. They also do not recognize denial of reasonable accommodation as a form of discrimination, as required under the CRPD.[80]

More problematically, the limited “assistance” and “help” that schools must provide is conditioned on whether children are “able to adapt themselves to study in ordinary classes,” as stipulated in the CEL and the REPD.[81] On the one hand, schools are supposed to provide assistance and flexibility to students with disabilities; on the other, students are supposed to show themselves able to adapt to study in mainstream classes. In practice, the burden of proof is on the students themselves — during enrollment, throughout the academic year, and as they advance in school — to show that they can adapt to existing school requirements.

Barriers to Education for People with Disabilities

Discrimination and Exclusion from Mainstream Schools

Although the Chinese government is obligated by international law to ensure that all children have access to the general education system regardless of disabilities, families told Human Rights Watch that children and young people with disabilities are denied admission by mainstream schools in their areas, pressured to leave the schools, or effectively expelled because of their disabilities. They also reported that schools do not provide reasonable accommodation. Teachers are not given the necessary support or training to work effectively with students with disabilities; classrooms are physically inaccessible and lack appropriate materials; and student evaluation methods lack flexibility.

Some children and young people with disabilities do overcome all these barriers to education. Parents play a crucial role in this process, but generally lack awareness of their children’s educational rights and options. Many parents told Human Rights Watch, for example, that they were unaware of the concept of “reasonable accommodations” or that the government and schools are legally required to take measures that allow children with disabilities to study at mainstream schools. Instead, as noted above, several told us that it is their children who are “defective” and need to adapt to the classrooms. A few parents with financial means told Human Rights Watch that they quit their jobs to accompany their children in school, moved to a different neighborhood with more accepting schools, or started new private schools for their children and others whom mainstream schools would not accept — just to improve the odds of their children getting the education guaranteed to them by law.

Most children whose parents are unable or unwilling to provide support are denied the opportunity to be educated altogether. Among the 47 families interviewed by Human Rights Watch, six children and young people with disabilities never attended school and six dropped out from mainstream schools along the way. Most of those who do not attend schools live in rural areas.

Bars to Admission

Nine of the 36 families we interviewed who had tried to enroll their child in mainstream schools were denied admission by one or more schools. One mother, Zhao Yibin, told Human Rights Watch that after kindergarten no mainstream primary school would take her son, who has albinism and limited vision:

We went to many schools, it was so hard. Nobody would take him. We felt terrible as parents…. At the time, the class teacher agreed to take us, but the one in charge of student discipline wouldn’t. I think he was afraid of the responsibilities.[82]

The mother of Chen Yufei said the mainstream school in her village refused to enroll her nine-year-old boy because of his disabilities.

The primary school near us wouldn’t enroll us. I went several times but they wouldn’t let him in … I have been especially angry because of this…. This is because my child is different. Other children in the village who are at a worse [academic] level are all enrolled.[83]

In explaining their reasons for not enrolling children with disabilities, schools cite a lack of resources to care for them and fear of taking on extra tasks and responsibilities, or simply say that the children “can’t learn,” [84] are “different from normal children,” [85] or “might affect other children.” [86] Song Jianjun, the mother of a child with autism, told Human Rights Watch:

[The school said] the conditions at the school aren’t adequate, that they do not have enough staff members to take care of these kinds of children, that he can’t control his behavior.... I went to about three schools, every one of them refused to take us, they all said the conditions in the schools don’t meet the standards.[87]

Mother of seven-year-old Chen Yusheng, who has a physical disability, told Human Rights Watch:

The people at the kindergarten didn’t want him, we brought him to the kindergartens in Guangzhou City, they all wouldn’t enroll him, they said they affect the other kids [in the school].[88]

The reluctance of mainstream schools to admit children with disabilities is also related to the highly competitive education system that focuses on test scores. In many parts of China, there is a “key school” system that rewards better-performing mainstream schools with more resources and funding, and children with disabilities are often seen as a burden to these schools. A staff member at China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF) told Human Rights Watch:

If you have intellectual disabilities, [mainstream schools] ask you not to study here…. The schools want their ranking and are afraid that intellectually disabled students would encumber them so they often find opportunities to demand that these kids to go to special education schools. [89]

Some mainstream schools require that parents to take care of their children at school as a pre-condition of admitting the children. A disability rights activist told us she met a couple of students who have severe mobility disabilities and were initially refused admission, but the parents pleaded to the school. According to her:

[T]he school said that unless a parent accompanied the child, [they could not enroll the child] because the teacher has to prepare for class. The teacher cannot accompany the child to the bathroom, or do much else … so the parents agreed and let the grandmother accompany the child, taking him to drink water and to the bathroom. If you can do this much, then the schools may take you.[90]

A few parents told Human Rights Watch that before children with disabilities are admitted, they have to sign agreements with the school releasing the school of responsibility should their children fall ill or be hurt.

We have an agreement with the teacher, which we sign every year because our child is different from normal children. [We have to promise that] if the child’s sick and so on, it has nothing to do with the school. It’s a liability waiver.[91]

In two out of the nine cases we investigated in which children were denied enrollment in mainstream schools, the children are currently out of school. One is Yu Yuechun, a 13-year-old with an intellectual disability, whose grandmother told Human Rights Watch that schools would not enroll him because “he can’t learn.” Prior to that, he was expelled from school after half a year.

When he was seven he went to primary school for half a year, but after he had fights with the other children, the school wouldn’t let him continue. Then we went looking for other schools, but they said he can’t learn and wouldn’t take him.[92]

Pressures to Leave and Dismissals

The struggle to enroll children with disabilities in mainstream schools does not end when the child begins to attend classes. Several parents told Human Rights Watch that school administrators or teachers pressured them to remove their children from school. A parent-advocate who runs a rehabilitation center for autistic children and is the mother of an autistic boy told Human Rights Watch that many parents who come to her center have had bad experiences at mainstream schools:

[A]t most you can stay there for one or two years before you are very tactfully asked to leave. In my experience, it is difficult to find a school and get admitted, but if you belong to the school district then they can’t refuse [to enroll] you…. They admit your child but find opportunities to tell you that they want you to transfer your child to another school.[93]

Although Zheng’s son has managed to stay in the mainstream school, the teacher keeps suggesting that he “take a leave of absence” from school. In another case, the mother of Wang Le, a child with a severe hearing impairment, told Human Rights Watch that after studying in a mainstream school for half a year, the school tried to get her to transfer him to a special education school:

[A]fter the teacher learned more about him, the teacher told us once: “Mother of Wang Le, why don’t you find another school? He is very smart, but he can’t hear anything. I’m afraid his talents would be wasted.” That’s what the teacher said, it was put very nicely, but … where else could he go? [94]

Li Shengrong, a 15-year-old girl with an intellectual disability, told Human Rights Watch that her school complained about her ability to learn and expelled her after alleging that she cheated on an exam. A number of children with intellectual disabilities reported to Human Rights Watch that schools used similar excuses regarding behavioral problems when expelling them or asking them to leave:

There was a school near us but they dismissed me…. Because I didn’t learn well…. I didn’t know what to write during exams. I was really bored so I looked at other [students]. The teacher saw me and told me to leave…. But I didn’t look at others’ [papers].[95]

These students also told Human Rights Watch that they were dismissed from mainstream schools after they were neglected and bullied by teachers and fellow students. In the words of 16-year-old Chen Ping, who now studies in a private special education school for children with intellectual disabilities:

A math teacher gave me a scolding [after] he gave me zeros for every exam, and then he said some very nasty things. I couldn’t stand it … and when he told me to go home, I went home…. The principal told me himself that because my math is no good, I should contact this [special education] school.[96]

Lack of Reasonable Accommodation

You’ve brought him to a normal environment, thus it is he who must adapt.

—The mother of Zheng Jun, a boy with autism, recalling the words of his teacher at a mainstream school, January 2013.

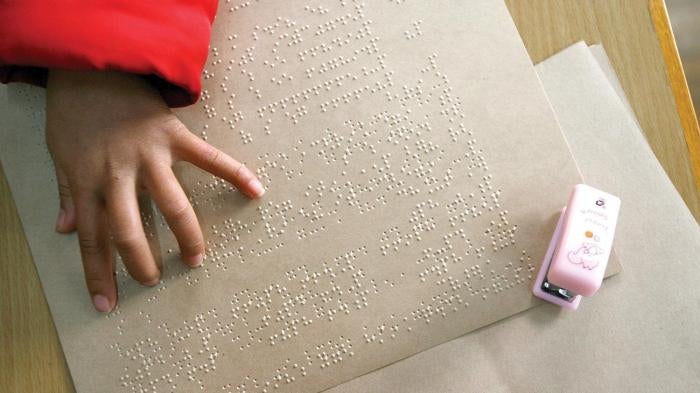

Human Rights Watch research found that little to no accommodation is provided in mainstream schools for students with disabilities at all stages of education. Students with severe mobility impairments said they need to go up and down the stairs to get to their classrooms or use the bathrooms. Those with hearing impairments said they have no written notes provided and there is no sign language instruction available; mainstream schools described to Human Rights Watch do not readily provide visual aids, Braille, electronic materials, or enlarged texts for students with visual impairments. Children with intellectual disabilities are expected to sit through the entire curriculum together with the rest of the class with little modification to the curriculum or teaching methods to meet their learning abilities and needs. None of the schools at which the interviewees study have resource rooms.

Our interviewees also described a lack of flexibility in the evaluation of student performance in the mainstream system, noting that schools fail to modify tests or exams to accommodate students with disabilities. In higher education, blind students are effectively barred from mainstream education because Braille or electronic exam papers are generally unavailable during gaokao, while deaf students are severely disadvantaged as listening exams are a requirement for a national standardized English test required for university graduation.

Students with disabilities and their parents told Human Rights Watch that few teachers take the initiative to provide them with reasonable accommodation and, in some cases, teachers neglected or even humiliated them.[97] While a few said that their teachers have better teaching styles or provide them with better support, such efforts are inconsistent. Lack of support and training to teachers and school administrators, lack of funding to schools for inclusive education, and the fact that evaluation of educators rarely takes into account the performance of students with disabilities all contribute to schools’ failures to ensure reasonable accommodation.

The Role of Teachers

One important way of providing reasonable accommodation is to modify teaching styles and methods. However, most parents and students with disabilities interviewed responded negatively when asked whether teachers adjusted their teaching methods to meet their needs:

Some individual teachers would take the initiative to ask me if I understood, and that I could ask them anytime if I don’t … but that’s very rare. In three years at university, I have experienced [such initiative from teachers only] five times. We have no examples [of accommodation]. The teachers treated me the same as other students.[98]

Students with intellectual disabilities are expected to sit through the entire curriculum together with the rest of the class — as one parent puts it, “even when they can’t understand.”[99] Worse still, a number of students with intellectual disabilities or autism and their parents reported to Human Rights Watch that teachers intentionally ignored them due to their poor academic performance. Mother of Chen Xiaoling, who has intellectual and visual impairments, said Chen was placed in the back of the class.

The teacher didn’t pay any attention to her, she didn’t get any exams or homework, she just sat at school. The teacher didn’t care which parts she didn’t understand…. Her eyesight is very bad…. She certainly couldn’t see anything. She was moved to the back of the class because she couldn’t follow the class.[100]

Similarly, the mother of Zheng Yu, who has an intellectual disability, told Human Rights Watch:

I bring the child to school and the teacher would let him in, but if he leaves [during school], the teacher doesn’t stop him…. It’s like this every day. The school hasn’t given him textbooks but we bought him some notebooks so he could draw.[101]

A few interviewees reported being given some accommodations in mainstream schools, but the efforts are inconsistent and sporadic at best, dependent on the attitudes of individual teachers and schools. [102] Some teachers have teaching styles that make it easier for students with disabilities to follow. Sixteen-year-old Liu Yiyuan said some of her teachers wrote down notes on the blackboard and spoke slowly; others did not write anything down and she “couldn’t keep up.” [103] None of her teachers provided written notes and they walked around the classroom while teaching, sometimes standing at the back of the class.

The accommodations also tend to be less available in higher grades, as teachers face greater time pressure to prepare students for gaokao. The mother of a 15-year old girl with a hearing impairment explained:

[My daughter] mainly reads lips, but now in universities and high schools the teachers speak very quickly, and they can’t [always] talk facing you. In the past, her teachers were all very good, she was very lucky. [104]

Whether or not a child is provided with accommodations in schools depends on the attitudes of teachers and school administrators. In the words of Zheng Jun’s mother, it depends on “your luck if you meet a teacher or a principal who is relatively better.”[105] A scholar focusing on inclusive education told Human Rights Watch that much of the variation in teacher attitudes can be attributed to government failure to institutionalize the guarantee of “reasonable accommodation”:

I have a student who was paid so little attention by the teachers between primary one and three that he felt he was like “a sheep put out to pasture.”… When he was in primary four, one teacher discovered that when he magnified the exam papers, the child performed very well, so he then made large prints of the exam papers for this student…. This kind of support is not ensured by the system but stops at the level of awareness and goodness of the hearts of the teachers.[106]

Parents, students, teachers, and principals told Human Rights Watch that the main reasons for failure to provide reasonable accommodation are inadequate support to teachers and large class sizes. With 30 to 60 students in a mainstream school classroom and no support staff to care for children with disabilities, teachers have little time to devote to individual students, much less to make adjustments to teaching styles, teaching materials, or evaluation mechanisms for the one or two students with disabilities in the class. [107]

Liang Sisi, mother of a child with cerebral palsy, told Human Rights Watch that “with so many children in the class, the teachers is too busy” to care for her daughter. She added that the school principal was reluctant to enroll her child because the school had no extra hands to provide care for these students, and the responsibilities land on the teachers. She explained:

The principal told me that there was a parent who brought his child to school, but did not provide any care. So the teacher had to carry the child on her back everywhere, and the teacher didn’t like it. So the principal said to me, “If we put your child in a class, I still have to obtain the consent of the teacher. If the teacher isn’t willing to accept your child then I can’t do anything for you.”[108]

Such lack of support can also lead teachers to become frustrated with students with disabilities, according to two educators in mainstream schools who spoke with Human Rights Watch. One teacher told us that her student, a 6-year-old boy who has intellectual and mental disabilities, keeps hitting other students and doesn’t respond when she calls him, “as if he has no ears.”[109] The child’s academic performance “is just bad.”[110] The mother of Wang Le, a boy who has a severe hearing impairment, said his teacher would

point a loudspeaker right at him but he still could not understand what the teacher said even though he wears a hearing aid. Sometimes the teacher gets so mad.[111]

Because of the lack of government or school support for educators, as one parent put it, “it is the parent who provides the support.”[112] The same parent noted that when “the teachers are good, then they help you or ask the other students to help you, but most of the time, the burden falls on the parents.”[113] In some cases, schools make the parents agree to provide support as a condition for enrollment, or the parents take the initiative to offer such support in a bid to get their children enrolled.

In China, the performance of many schools and teachers is evaluated on the basis of the average grades of students. Some schools treat students with disabilities as “audit students” or otherwise exclude their grades from the class average in order to ensure that children with disabilities do not lower the school’s overall score. For example, the mother of Yang Shun, a 12-year-old girl with an intellectual disability, told Human Rights Watch:

[The children with disabilities in this school] are all auditing, their grades are not recorded as part of the school’s overall grades…. They didn’t ask us [for our opinions] about this…. If our children score zeros in tests then it affects the class scores in that year level. Their class teacher is rated, and the substitute teacher as well. Since [children with disabilities] affect their ratings, they definitely wouldn’t [include our children’s scores.][114]

One family described a school principal’s calculation about whether to admit their daughter, basing his decision on her likely academic ability. The experience of Xu Lele, a 15-year-old girl with hearing and speech disabilities, illustrates this point. Her mother told us:

The principal said, “For people like [your daughter], I suggest she go to the school for the deaf because our school does not have students like her.” I told him that my child would like to study [here] and he said, “She might want to study [here], but the question is whether or not she can.”… Then he talked about making guarantees, that if my child can’t keep up in class, then she can’t take the exams or be enrolled. After she was enrolled she did well, so she has been taking the same tests as other students.[115]

One teacher even told the mother of Zheng Jun, a child with autism, that “regardless of how well or poorly he might be doing, it has no bearing on my performance [evaluation].” [116] Mrs. Zheng clearly feels that her son is being discriminated against. She explained:

He takes his exams together with others, but since primary two, the teacher hasn’t given him his grades… He minds such things very much. He knows … Sometimes he said he did better than his classmate in the exams, but his classmate got a score and he didn’t.[117]

Because the performance of students with disabilities does not form part of their or the school’s evaluation, teachers and school administrators often are not inclined to exert themselves on behalf of students with disabilities. Education officials acknowledged that there “isn’t any system of assessment for the quality of ‘study along with the class’ schemes.”[118] As one scholar who studies inclusive education puts it:

The child’s performance is not included in the evaluation [of the teacher], so the teacher doesn’t care. He has so many students in his class. He has no energy, nor the willingness to take the initiative to help such kind of children.[119]

Lack of Training and Funding

Teachers and school administrators lack training in inclusive education, while schools lack funding for providing support to the teachers to make accommodations possible.[120] Although the Law on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities (LPDP) and the Regulations on the Education of Persons with Disabilities (REPD) stipulate that institutions that train mainstream teachers must include courses on teaching students with disabilities, a survey of these institutions show that only 13.9 percent of them do so, and only a minority of those do so regularly.[121] Although on-the-job training is available from bureaus of education, the sessions are short and the number of teachers trained remains low. Most teachers of students with disabilities still have not received such training, and there is no clear timeline to ensure that such standards are met for all mainstream teachers.[122]

The principal of the school attended by Zheng Leyan, a girl with an intellectual disability, told Human Rights Watch that he wished that her class teacher could be trained in special education. According to him, the local bureau of education has never made such arrangements. “I have no idea how they teach [children with disabilities],” he said.[123]

Another principal told us that he has “never heard of” training available for teachers in mainstream schools designed for teaching children with disabilities, even though he has been at the school for more than a decade, while training for other basic teaching skills are available “from time to time.”[124]

Mainstream schools often receive little or no funding to provide accommodations for children with disabilities, even though Chinese regulations on disability and education stipulate that funding be allocated by local education bureaus to mainstream schools for that purpose.[125] In a 2006 survey, only 7.7 percent of mainstream schools that enrolled students with disabilities reported that their local bureaus of education had earmarked sufficient funds for these children, while over half of the respondents said there was either no designated funding or that the funding was very little.[126]

Educators interviewed by Human Rights Watch also said that while they have to report to the local bureau of education that they have children with disabilities in the school, they receive no additional funding from the bureau for the children.[127] Rather than being earmarked to ensure reasonable accommodations, available funding is used to waive miscellaneous fees and provide a small cash subsidy to the students with disabilities (the policy of “liangmian yibu” or “two waivers and one subsidy”), or goes to provide a small subsidy for teachers to “motivate”[128] them to better educate students with disabilities in their classrooms.

Lack of Transport to School

A number of parents told Human Rights Watch that they are their children’s sole means of transport. And for children with disabilities affecting their mobility, when parents fall ill, are injured, or otherwise cannot afford to take the time to accompany their children to school, then the children are forced to stay home. Yang Ranran, mother of a boy with a mobility disability as a result of cerebral palsy, told Human Rights Watch of their plight after she broke her leg:

I fell and cut open my leg, so I couldn’t walk. If I didn’t fall then, I could have carried him on my back…. We have no other way [to send him to school]. We don’t own our home and his father has to go to work…. I spoke with the principal and told him that after the new year I’d bring him to school in a cart … but I’m afraid that I might not be able to pull the cart given my poor health.[129]

There is no general transportation scheme to take students with disabilities to mainstream schools. In replies to an information disclosure request filed by a disability activist in February 2013, all six municipal and provincial education bureaus that directly responded to a question regarding provision of transport to students with disabilities denied that lack of transportation was a problem for students with disabilities, saying that students with disabilities either live in residential facilities or near the mainstream schools they attend. [130] This is very likely untrue for some mobility-impaired students, and for those who live near mainstream schools, a “short” trip to the school can be very long given their impairments. [131]

As noted above, about 75 percent of people with disabilities in China live in rural areas, and government consolidation of mainstream schools in rural areas is estimated to have closed down half of all rural schools in the past decade.[132] This has meant that mainstream schools are now even further away from some rural students.[133] This places an extra burden on parents because they need to organize transport or rent a room near the schools to accompany their child. Some of these schools provide residential facilities, but there is no support staff to take care of children with disabilities.

A number of parents of children with disabilities told Human Rights Watch that the distance to the nearest mainstream school was one of the main reasons their child was no longer attending school. For example, Chen Xiaoling’s mother told us that Chen dropped out of school when she was 13 because:

The [village] school was closed and consolidated in 2010…. If it was still here then I’d let her continue [in the village school].[134]

Similarly, father of Zheng Leyan, who has an intellectual disability, told Human Rights Watch that Zheng will drop out of school once she finished primary four because he and his wife cannot afford to give up working in the fields to accompany her to school, especially when she “can’t learn.”

No, it’s too far away. The centralized school is about 17-18 kilometers away. It’s not possible, we would have to rent a flat [near the school], how is it possible?[135]

The grandmother of 13-year-old Zhang Xiaoli, who has mobility and intellectual disabilities and dropped out of school after finishing primary school, told Human Rights Watch the following about her granddaughter:

She wants to study, and she’s cried about it. She graduated from primary school, but she cannot continue…. She could go to junior high school, but the school is too far away. She can’t walk there but she also doesn’t know how to ride a bike…. The main reason is still no one to send her to and back from school.[136]

Lack of Accessible Classrooms and Materials

Parents and students we interviewed also said that mainstream schools and local governments fail to ensure that students with disabilities both have easy access to their classrooms and are provided with alternative means of communication and assistive devices.

While students with mild physical disabilities generally have few problems getting around school, those with more severe mobility impairments told Human Rights Watch that getting to school as well as getting around school is difficult. Liang Sisi, mother of a girl with cerebral palsy, told Human Rights Watch that much of her day is spent caring for her daughter at school:

Their school has only one bathroom on the first floor [and her class is on the fourth floor]…. I bring her to school in the morning, and after two classes I go there again to help her to the bathroom, and again in the middle of the afternoon. I go back and forth many times.[137]

Visual aids and large print materials are not readily available for students with visual impairments in mainstream schools.[138] They also typically do not offer Braille and are not equipped with Braille teachers.[139] As a result, most students who are blind or with low vision go to special education schools because they have better facilities than mainstream schools and because mainstream schools are reluctant to accept them.

Braille or electronic exam papers are also not readily available during public university entrance exams including gaokao, which means that blind students are almost entirely excluded from mainstream higher education. In 2012, Wang Qiuyi, a blind student who studied in a special education school, applied for Braille papers for gaokao in Shandong Province but the provincial bureau of education rejected her request. The bureau’s explanation, according to a news report, was as follows:

Even if Wang takes the exams, she would be unable to participate in class like normal students and since ordinary universities cannot provide Braille textbooks, she cannot receive a normal education in ordinary schools.[140]

However, the LPDP stipulates that for “school entrance exams, career qualification exams and placement exams which blind people take part in, Braille or electronic exam papers or assistance from specialized staff shall be available.”[141] The Regulation on the Construction of Barrier-Free Environments also has a similar requirement.[142] In response to an information disclosure request sent to all 31 provinces and municipalities, out of eight bureaus of education which responded directly to the question only the Shanghai bureau said that it had provided Braille exam papers in the past four years.[143]

In another case in 2011, Dong Li’na, a young blind woman, applied to the Beijing Bureau of Education to take qualification exams to become a radio host after she completed a tertiary level self-study course. According to media reports, the bureau struck down her request on grounds that there was “no such precedent” and that “[given her] physical condition [she] should not participate in this professional examination.” [144] Dong later sought help from an anti-discrimination organization, the Beijing Yirenping Center, which publicized her case widely and filed complaints to the bureau. The bureau then promised to provide an accommodation for Dong, and she took the series of exams starting in January 2012. After this case, the Beijing Bureau of Education promised that such accommodations would be available to all people with visual impairments who take professional tertiary-level qualifications exams in Beijing, and a couple of other blind students have since been provided with electronic exam papers for other subjects in Beijing. [145]

Parents and young people with disabilities also told us of arbitrary treatment in the distribution of hearing aids. Instead of ensuring that children and young persons with hearing impairments are equipped with these devices to meet their educational needs, interviewees told Human Rights Watch that the provision of these devices is often based on other criteria. A disability rights activist said the hearing equipment is only given to those who are poor and children are not prioritized; a CDPF staff member said that they only distributed the devices if individuals make an application for them; a couple of parents said that they were only available to young children under a certain age limit.[146] The mother of a 16-year-old with hearing impairment who studies in a mainstream school told Human Rights Watch that her child was only able to afford a good pair of hearing aids with the financial assistance of her uncle. The mother said:

The CDPF told us to go [get hearing aids] but … they didn’t give her any [because they said] she was too old and she wouldn’t be able to hear anything even if she’d be given hearing aids.

Information about where and how to obtain these devices is also not readily available to the parents. Two families we spoke with reported that their children had no hearing aids because they did not know how to apply for them.[147] Whether or not a child with a hearing impairment gets a quality assistive device depends on a variety of factors and their own efforts to search for funding. The government’s Regulations on the Education of People with Disabilities (REPD) do not mention the provision of assistive devices for students with disabilities. A current university student who lost her hearing while she was in secondary school told Human Rights Watch that she had to take a part-time job to afford the hearing aid.

It was during my first year in university that I struggled to earn money to buy myself hearing aids that cost several hundred renminbi, and later I met a sign language teacher who lent me money so I bought a couple of better ones. Now I can hear in the classroom, but not clearly.[148]

Lack of Appropriate Student Evaluation Mechanisms

Students with disabilities are entitled, under a reasonable accommodation framework, to have their academic abilities evaluated by methods other than the fixed standards applied to other students in the educational system. A Ministry of Education document entitled “Methods for Managing the ‘Study Along with the Class’ Scheme for Persons with Disabilities (MMSACS)” stipulates that assessment of these students should be “flexible” and available in a variety of forms, as well as that the assessment of these students should be included in the “overall assessment of mainstream students” to “better integrate students with and without disabilities.”[149]

While the policy looks good on paper, some parents told Human Rights Watch that schools failed to provide any modifications to homework, tests, or exams to accommodate their children. One child with cerebral palsy who writes slowly has never been given extra time to write his exams. Another parent said the class teacher denied her request to reduce the volume of the written homework assigned to her child, who has autism and is poor at responding to questions in written format.[150] Yet another interviewee with hearing impairments reported that she has to take English listening exams at schools.[151]

Students with hearing impairments are exempted from the listening portion of gaokao exams but not from the listening exams for the College English Test, which are national exams administered by the Ministry of Education. University students are often required to pass these exams in order to graduate at both bachelor and graduate levels.[152] As interviewee Li Hongdan put it, she could “only guess” the answers to the listening test as she could barely hear anything.[153] Li tried to speak to her teachers about providing accommodations during the internal school assessment, but she was rebuffed.

Some teachers understand, but they are in the minority; but some teachers told me: “I won’t lower the assessment requirements because of your condition. You have to do whatever other students have to do.”

Study or Just “Muddle along with the Class”?

The shortcomings described above fail not only students with disabilities but their parents and teachers as well. Other than those involving mild physical disabilities, in almost all the cases we examined the parents or children said they were failing academically or had already withdrawn from mainstream school. One aim of mainstreaming is to combat stereotypes and prejudices, but placing these children in mainstream schools without ensuring reasonable accommodations undermines this important goal.

While some of our interviewees reported that they were treated well in school, a number said they were treated badly by fellow students. Tong Ying, a 17-year-old girl with physical disabilities, told Human Rights Watch that she prefers special education school.

Here we are all disabled, we are equal. I went to mainstream primary and junior middle school but I didn’t like them. I was beaten by teachers during primary school and bullied by fellow students. Lots of other students looked down on me.[154]