For a Better Life

Migrant Worker Abuse in Bahrain and the Government Reform Agenda

Summary

After the first time she hurt me it came to my mind that I want to go back to the Philippines. But then I thought if I go back to the Philippines, what will happen to my family? I cannot support them if I’m back there. But it was too late. Every day madam beat me.

–Maria C., migrant domestic worker, Manama, January 2010.

I received only one [full] salary, and for the other months I got BD27 [$72], but signed for the full amount. The foreman said, “You’ll get the rest in two days, it’s not a problem, so just sign it.” When he said that, I signed it.

After working for five months, I asked for my money but they didn’t give me my money. [The site engineer] told me, “Do your work; I’m not going to give you money. We’re only going to give you money for food, BD15 [$40] for 30 days.”

I told him, don’t give me money for food, send me home—I paid 80,000 rupees [$1705] on my house and I have to give it back. He said, “There is no money, go to the Labor Ministry, go to the embassy, you won’t get your money.”

–Sabir Illhai, migrant construction worker, Manama, February 2010.

For over three decades, millions of workers—mostly from south and southeast Asian countries such as India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines—have flocked to the Persian Gulf in the hope of earning better wages and improving the lives of their families back home.

Most of these workers come from impoverished, poorly-educated backgrounds and work as construction laborers, domestic workers, masons, waitresses, care givers, and drivers. Providing construction and service industries with much-needed cheap labor, they have helped fuel steady economic growth in countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain.

Despite their indispensable contribution to the life of their Gulf hosts, many workers have experienced human rights and labor rights abuses, including unpaid and low wages, passport confiscation, restrictions on their mobility, substandard housing, food deprivation, excessive and forced work, as well as physical, psychological, and sexual abuse.

The small island nation of Bahrain, with approximately 1.3 million residents, has earned a reputation among labor-receiving countries in the Gulf as the most committed to improving migrant labor practices. Its efforts include new safety regulations, measures to combat human trafficking, workers’ rights education campaigns, and reforms aimed at allowing migrants to freely leave their jobs. However, questions remain about the implementation and adequacy of these reforms.

This report explores the experience of Bahrain’s more than 458,000 migrant workers who make up around 77 percent of the country’s workforce—most working in unskilled or low-skilled jobs, in industries such as construction, retail and wholesale and domestic work. The report traces the many forms of abuse and exploitation to which migrant workers in Bahrain are subjected by employers and the obstacles and failures that prevent them from seeking effective redress for such treatment. It outlines the rights and international legal standards that apply to workers, and calls on the governments of Bahrain and of labor-sending countries to adopt additional protections for migrant workers in Bahrain.

Employer and Recruitment Abuses against Migrant Workers

The plight of many migrant workers in Bahrain begins in their home countries, where poverty and financial obligations entice them to seek higher paying jobs abroad. Often, they pay local recruitment agencies fees equivalent to approximately 10 to 20 months wages in Bahrain, even though Bahraini law forbids anyone from charging such fees to workers. It is common for construction and other low-skilled male workers to pay such fees, although uncommon for domestic workers, who tend to come to Bahrain through formal recruitment agencies. The debt that many workers incur to pay recruitment agencies and airfare means they feel compelled to stay in jobs despite unpaid wages or unsafe housing and worksite conditions for months and even years.

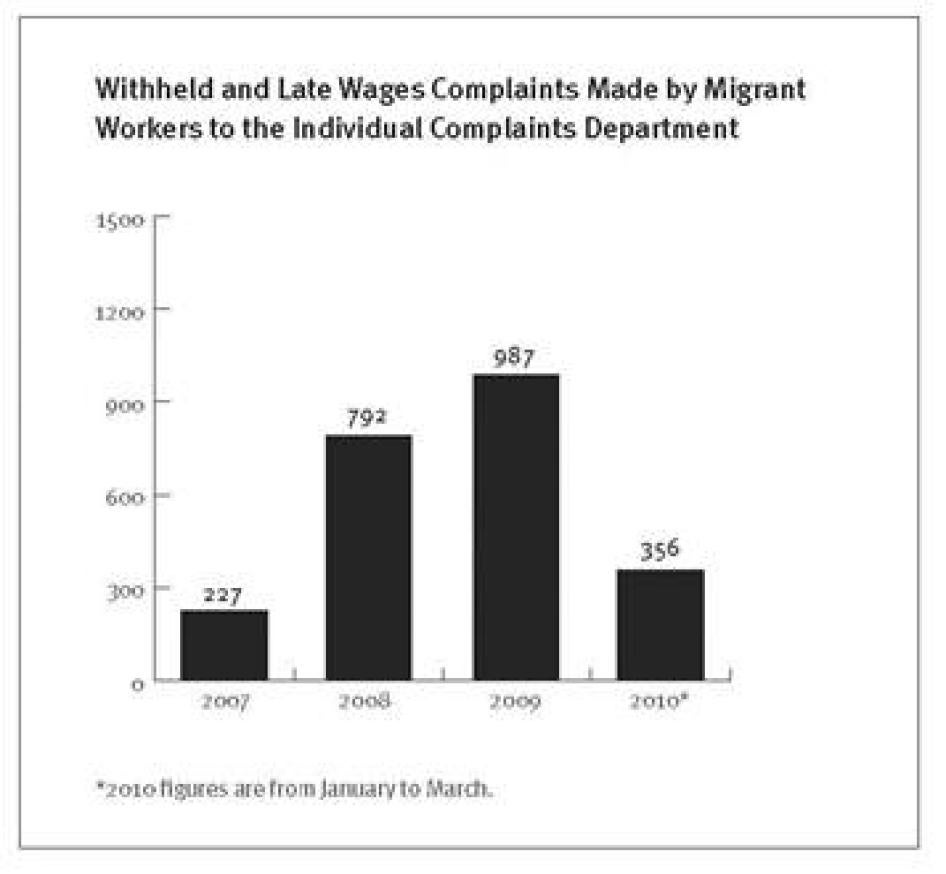

Once in Bahrain, migrants depend on regular payment of their salaries to meet their own immediate financial needs and those of their families at home, or to meet monthly loan repayments. Workers indicated that the problem of unpaid wages tops the list of their grievances. Although nonpayment of wages is a criminal as well as civil offence in Bahrain, some employers withhold wages from migrant workers for many months. Without an income source, migrant workers take on more debt to cover basic needs. In 2008 and 2009 the Individual Complaints Department at the Ministry of Labor received nearly 1,800 complaints of withheld and late wages. Out of 62 migrant workers whom Human Rights Watch interviewed, 32 reported that their employers withheld their wages for between three to ten months: one domestic worker did not receive wages from her employer for five years. The government did not reply to Human Rights Watch’s 2012 request for 2010 and 2011 numbers.

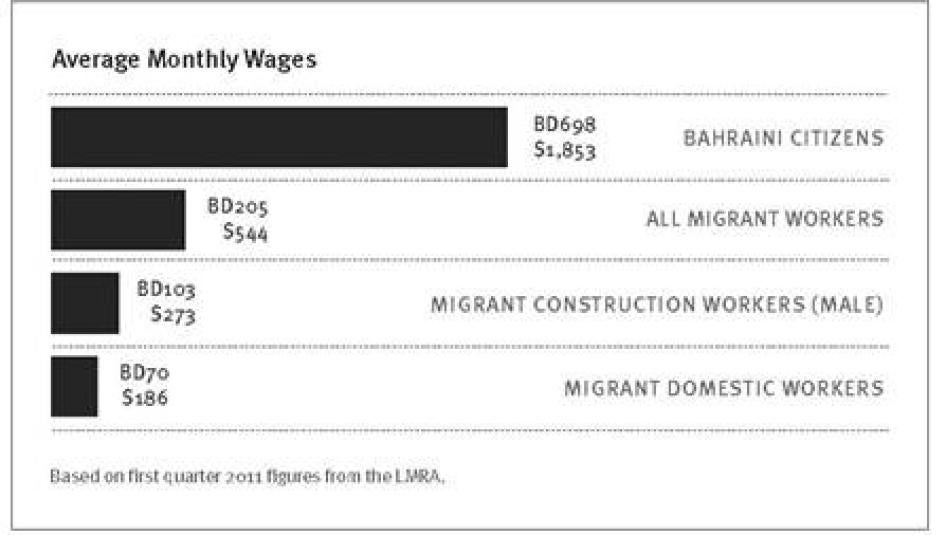

On average, migrant workers in Bahrain earn BD205 or $544 a month, compared to BD698 ($1,853) earned by Bahrainis, and comprise 98 percent of “low pay” workers (the government defines “low pay” as less than BD200, or $530, monthly). Most migrant workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch earned between BD40 and 100 ($106-$265) monthly, while a few earned up to BD120 ($318) with overtime. The Indian government requires a monthly salary of at least BD100 ($265) for its nationals in Bahrain, while the Philippines requires at least BD150 ($398). Employers rarely meet these rates. The Bahraini government has resisted adopting minimum wage legislation.

Domestic workers earn notably less than migrants in other sectors, as little as BD35 ($92) per month, averaging BD70 ($186), according to the government. Many work up to 19-hour days, with minimal breaks and no days off. Many domestics reported that they were prevented from leaving their employer’s homes, and some said they received little food. Workers in other sectors such as construction and service industries generally work 8-hour days and receive Fridays off, although about a dozen construction workers reported regularly working 11 to 13-hour days without overtime pay.

Employers typically house construction workers and other male laborers in dormitory-style accommodation in labor camps that can be cramped and dilapidated with insufficient sanitation, running water, or other basic amenities. Three of the four camps that Human Rights Watch visited had kitchens with kerosene burners, which are fire hazards and violate Bahraini code. While Bahrain’s Ministry of Labor has worked to improve camps and make them safer, it has too few inspectors and substandard camps continue to operate.

Some migrant workers experience physical abuse in the form of beatings as well as psychological and verbal abuse. There are no reliable numbers on cases of physical abuse, but 11 of the 62 workers Human Rights Watch interviewed reported abuse. Over half of these were domestic workers, some of whom were also subject to sexual abuse and harassment by employers and recruitment agents, such as unwanted advances, groping, fondling, and rape. Human Rights Watch interviewed four domestic workers who reported sexual harassment, assault, or rape by their recruitment agents, employers, or employers’ sons.

Exploited or abused migrant workers often want to change jobs or return home. Employers almost universally continue to confiscate migrant employees’ passports upon arrival, even though the practice is prohibited. Bahraini authorities largely fail to enforce prohibitions on confiscating passports or compel employers to return the documents. The Ministry of Labor, immigration officials, and police all say they formally and informally ask employers to return passports, but they lack the authority to compel employers who refuse to do so. Workers can appeal to courts, but it can be difficult to enforce court orders to return passports when employers refuse to comply. Furthermore, employers must cancel work visas before migrant workers can leave the country. Senior immigration officials can waive this requirement, but only do so after repeatedly trying to persuade the employer to cooperate—a process that can take weeks or even months. Employers also frequently try to extract payments from employees in exchange for returning their passports and signing a visa release.

Attacks against Migrant Workers

Migrant workers in Bahrain not only experience abuses within the context of the employee-employer relationship but also face discrimination and other abuses from Bahraini society in general. Since 2008, Human Rights Watch has received reports of assaults on South Asian migrant workers by Arab men who were not the workers’ employers. For a very brief time in mid-March 2011, as the confrontation between security forces and anti-government protesters intensified, these attacks escalated dramatically. The attacks took place amid growing frustration by many Shia Bahrainis who believe migrant workers are taking jobs, especially positions with the police and security forces, away from citizens. Pakistanis, some of whom have been naturalized, comprise a significant percentage of Bahrain’s riot police.

Human Rights Watch documented several violent attacks against South Asian migrant workers in and around Manama on March 13-14, 2011, immediately before security forces launched a violent crackdown on the anti-government protests. Human Rights Watch spoke with 12 migrant workers who witnessed or were victims of the attacks, all of them nationals of Pakistan and Bangladesh. Seven of them said that Arab men armed with sticks, knives, and other weapons harassed and attacked them at their places of residence. Some alleged that their attackers were anti-government protesters, though they could not provide information to support that allegation. All of the men interviewed said they could not positively identify their attackers because they had covered their faces with their shirts or masks.

The Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry, which investigated human rights violations in connection with the government response to anti-government protests, noted that according to Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior four migrant workers were killed as a result of incidents related to the unrest and a further 88 expatriates were injured, including 11 Indians, 18 Bangladeshi, 58 Pakistanis, and one Filipino.

Following a criminal investigation by Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior, authorities prosecuted 15 defendants for their alleged involvement in the murder of Abdul Malik, one of two migrant workers murdered in front of a residential building in the Manama neighborhood of Naim. On October 3, 2011, a special military court convicted and sentenced 14 of them to life imprisonment. The fifteenth defendant was acquitted of the charges and released. As of mid-September 2012 their convictions were under review by an appellate civilian court.

Bahrain’s Reform Efforts

Even before it embarked on recent legal and policy reforms affecting migrant workers, Bahrain provided legal protections to many migrant workers that are absent in several neighboring Gulf states. Bahrain’s labor laws and regulations have long applied to both nationals and to migrant workers (with the key exception of domestic workers) and include the right of workers to join trade unions. For example, Bahrain’s 1976 Labor Law for the Private Sector standardized labor practices, including work hours, time off, and payment of wages— but failed to protect domestic workers.

Bahrain’s penal code has also provided criminal sanctions that can protect migrant workers against unpaid wages, and physical and sexual abuses.

In 2006 Bahrain established the Labor Market Regulatory Authority (LMRA) with a mandate to regulate, among other things, recruitment agencies, work visas, and employment transfers. The LMRA’s duties include issuing work visas, licensing recruiters, and educating workers and employers about their rights and legal obligations. Its main policy goals include creating transparency about the labor market and regulations, increasing employment of Bahraini nationals in the private sector in place of migrant workers, and reducing the number of migrants working illegally in the country. The agency has developed an online and mobile phone interface that allows workers to monitor their work visa status, and produces an informational call-in radio program that airs on an Indian-language station in Hindi and Malayalam, where workers can ask questions about their visas and LMRA policies. An eight-language LMRA information pamphlet distributed to migrant workers upon entry at the airport tells them how to apply for and change a work visa, informs them of their right to keep their passports, and provides a Ministry of Labor contact number to report labor violations.

On April 23, 2012, the National Assembly passed a new private sector labor law, Law 36/2012, which King Hamad signed into law on July 26, 2012. The new law extends sick days and annual leave, authorizes compensation equivalent to a year’s salary for unfairly dismissed workers, and increases fines employers must pay for violations of the labor law. Under the new law, according to the media, employers who violate health and safety standards can face jail sentences of up to three months and fines of BD500 to BD1,000 ($1,326 to $2,652), with punishments doubling for repeat offenders.

The new law introduces a case management system designed to streamline adjudication of labor disputes and keep proceedings to around two months. Lengthy proceedings have until now made it impossible for many migrant workers to pursue litigation to a final ruling since they were unable to remain in Bahrain for a lengthy period without a job or income.

According to Bahraini media, Minister of Labor Jameel Humaidan has said that under the new law domestic workers “will be entitled [to] a proper labor contract which will specify the working hours, leave and other benefits.” The government told Human Rights Watch that the new labor law includes numerous provisions pertaining to domestic workers.

Most of the law’s protections still do not cover domestic workers, although some provisions extended to them under the new law do formalize existing but previously un-codified protections for domestic workers, such as access to Ministry of Labor mediation, requirement that a domestic worker have a contract, and exemption from court fees. The law does introduce new protections as well, including annual vacation and severance pay. However, the new law does not set maximum daily and weekly work hours for domestic workers or mandate that employers give them weekly days off or overtime pay. In this regard, the law fails to address the most common abusive practice of excessive work hours that domestic workers face.

In June 2012 an official with the LMRA told Human Rights Watch that the agency had begun drafting a unified contract for domestic workers that would standardize some protections, but did not provide specifics of the contract. Ausamah Abdullah Al-Absi, head of the LMRA, told Bahraini media that the LMRA’s aim was to guarantee decent work and living conditions for domestic workers and the “unified contract will contain basic rights of workers according to international treaties."

Bahraini authorities also moved in recent years to reform the employment-based immigration system, commonly called the kafala (sponsorship) system, under which a migrant worker’s employment and residency in Bahrain is tied to his or her employer, or “sponsor.” In the past, the sponsor dictated whether a worker could change jobs or leave the country before the period of the employment contract ended. This gave employers enormous control over migrant employees, including the ability to force them to work under abusive conditions. In August 2009, the LMRA reformed the system to allow migrant workers to change employment without their employer’s consent after a notice period set in the worker’s employment contract, which could not exceed three months. Workers then had 30 days to remain in the country legally while seeking new employment. In June 2011, however, the government watered down this reform by requiring migrant workers to stay with their employer for one full year before they can change jobs without employer consent.

Despite the reform of the sponsorship system, the LMRA continued to reject most applications by migrant workers seeking to change jobs without employer consent. Employers also continued to have undue influence over a worker’s freedom of movement because they had to cancel work visas before migrants could leave the country (unless this requirement was waived by a senior immigration official). Moreover, the reform fails to cover the country’s 87,400 domestic workers.

Bahrain took a number of other steps to address the abuse of migrant workers including:

- In November 2006, the Ministry of Social Development established the 60-bed Dar Al Aman women’s shelter, with a floor dedicated to migrant women. The facility took in 162 migrant women in 2008 and 2009—most of whom were referred by police, embassies of workers’ home countries, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The Ministry of Social Development did not provide 2010 and 2011 numbers in its May 2012 response to Human Rights Watch’s request for updates.

- In July 2007, the government implemented a ban on outdoor construction and other work between noon and 4 p.m. in July and August—the hottest months of the year. Employers appear to have largely observed the ban, primarily due to a campaign of sustained inspections by the Ministry of Labor that demonstrated the government’s ability to enforce labor standards when it committed resources to doing so.

- Law No.1 of 2008 with Respect to Trafficking in Persons allows the Public Prosecution Office to seek convictions against individuals and corporations that—through duress, deceit, threat, or abuse of their authority—transport, recruit, or use workers for purposes of exploitation, including forced work and servitude. The Bahraini government understands this law to criminalize many common labor abuses, including withholding wages and confiscating passports. However, Human Rights Watch found no evidence that officials have yet used the law to prosecute labor-related abuses or labor-related human trafficking in Bahrain.

- In May 2009, a ban went into effect prohibiting employers from transporting workers in uncovered open-air trucks, which aimed to reduce traffic-related deaths and injuries of construction workers and other laborers. In January 2010, Human Rights Watch observed widespread use of open-air trucks to transport workers, although in June 2010 we observed noticeably fewer open-air trucks transporting workers from the same pick-up location we visited in January. In early 2012 worker advocates acknowledged that the use of these trucks for transporting workers had become rare.

On December 10, 2010, the Bahraini government released a report drafted in cooperation with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) on the status of migrant workers. The report included government pledges to better protect migrant workers from abuse. These pledges came, in part, out of dialogue between the government and Human Rights Watch in which Human Rights Watch presented government officials with the findings and recommendations contained in this report.

Human Rights Watch had recommended that the government significantly increase the number of inspectors responsible for overseeing private sector labor, health, and safety practices and, in response, the government pledged to increase the number of Ministry of Labor inspectors by 50 percent. The ministry in fact increased the number of health and safety inspectors fivefold, from six in 2010 to 30 in 2011.

Implementation of many of the other pledges, however, has so far been weak or absent:

- The government had pledged to launch an inspections campaign aimed at “exposing employers who withhold wages and confiscate passports and to penalize violators.” However, in February 2012 representatives of the Migrant Workers Protection Society told Human Rights Watch that the government had not initiated such a campaign and added that the onus remained on the workers to report complaints to the Ministry of Labor regarding unpaid wages and to the police regarding confiscated passports.

- The government had pledged to initiate a campaign to inform workers that withholding wages and confiscating passports are crimes under the anti-trafficking law, to penalize employers that partake in these practices, and to act on complaints by workers who alleged such abuse. In 2011, however, authorities had not prosecuted cases of these and other common labor-related crimes, other than physical and sexual abuse and sex-trafficking. Migrant rights activists reported that as of February 2012 they were unaware of any workers rights public education campaigns.

- The government had pledged to “consider the adoption of the … ILO Convention on the treatment of domestic workers.” In June 2011, Bahrain, along with other GCC countries, voted in favor of establishing the convention, reversing its earlier opposition. As of this writing, however, Bahrain has yet to ratify the convention, the necessary step to make it binding.

Government Mechanisms Addressing Abuses

Labor and criminal courts, and the Ministry of Labor’s inspections and complaints departments, are designed in part to address worker grievances and curtail abuses. Human Rights Watch found that abusive and uncooperative employers often exploit the redress process, delay mediation and court proceedings, force workers into unfavorable settlements, and avoid punishment.

The Ministry of Labor had only 33 inspectors in 2010 to monitor compliance with labor laws and health and safety regulations of over 50,000 companies that employ around 457,500 workers. As noted, the ministry added at least 24 more inspectors in 2011. The head of the department of inspections told Human Rights Watch in 2010 that about 100 inspectors would be needed to conduct just one visit per year to every company. Migrant worker advocates told Human Rights Watch in February 2012 that the ministry’s total number of inspectors remains woefully low. Workers in two of the labor camps that Human Rights Watch visited said that ministry inspectors had cited their employers for serious housing code violations and ordered one of the camps to close, but the employer never made the required repairs and, as of January 2012, the camp that had been ordered to close in fact remained open, according to local migrant worker advocates. The ministry lacked authority to penalize companies directly for violations and instead had to forward cases to the courts, which can impose fines.

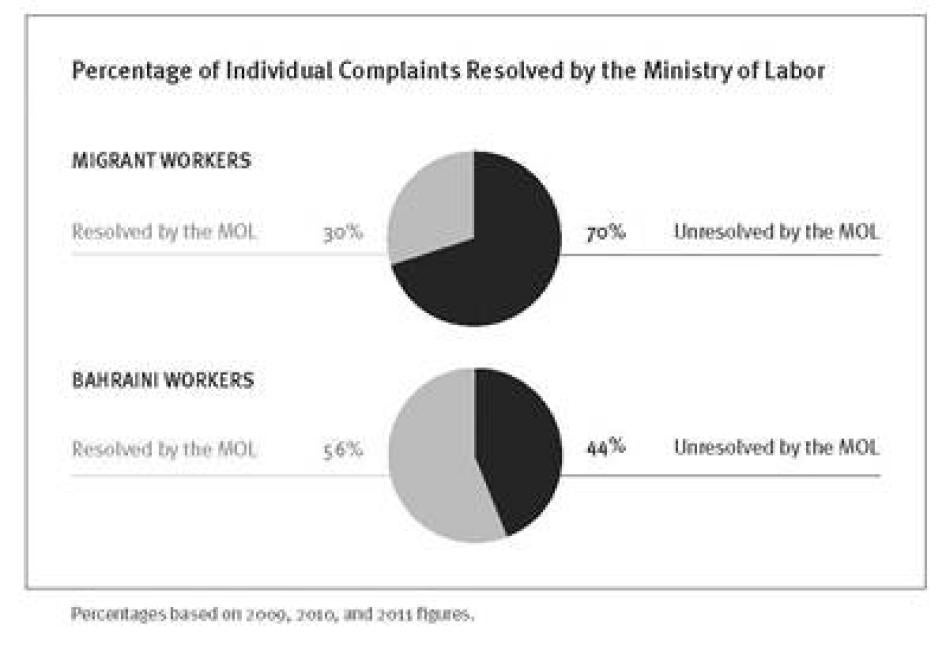

Migrant workers may register complaints of labor law or contractual violations with the Ministry of Labor’s complaints department, which then calls on the employer to participate in mediation. The ministry has no authority to compel a settlement, or for that matter employer participation. Abusive employers often refuse to settle and ignore the ministry’s request for a meeting. Although the ministry says it resolves about half of all labor complaints filed by Bahraini and migrant workers, mediation results in settlements for migrants significantly less often than it does for nationals. In 2009, 2010, and 2011 Ministry of Labor mediators resolved only 30 percent of complaints filed by foreign workers, forwarding the rest to labor courts. These complaints mostly concerned violations of labor law and individual employment contracts and exclude criminal acts such as assault, sexual assault, or human trafficking. In all, the Ministry of Labor forwarded 2,321 of these cases to Bahrain’s labor courts in 2009, 2010, and 2011, involving a total of 3,869 workers.

Labor lawyers and migrant worker advocates often advise migrant workers to reach a settlement outside labor courts. Lawyers told Human Rights Watch that courts often render worker-friendly judgments, but that cases take between six to 12 months to resolve. Labor court trials comprise on average six separate hearings that take place about every six weeks. Most migrant workers have no income source during this time, and often feel they have little choice but to accept an unfavorable out-of-court settlement. Many settle for a plane ticket home and return of their passports, foregoing a sizable portion, if not all, of their back wages. Some workers said they had even paid their former employers simply to return their passports and cancel their visas.

Bahrain’s Public Prosecution Office, which investigates and prosecutes crimes, has primarily pursued migrant labor cases that involve physical and sexual abuse. Since passing anti-human trafficking legislation, Law No.1 of 2008 with Respect to Trafficking in Persons, the government declared its enforcement a national priority, but thus far the Public Prosecution Office has only prosecuted trafficking cases that involve prostitution.

Worker advocates and lawyers complained that authorities can be unresponsive, and investigations and prosecutions are extremely slow in criminal and trafficking cases. Advocates shared cases with Human Rights Watch in which their clients—domestic workers—had suffered severe physical abuse, and even rape. In one case, the Public Prosecution had not charged the alleged abuser or completed the investigation more than a year after the worker filed a police complaint. Authorities soon ended the investigation altogether. In another case, authorities had not set a trial date more than six months after the worker filed her complaint and eventually dropped the investigation.

In a high profile human trafficking case in which 38 construction workers alleged that they were forced to work without compensation, the first hearing was not called for about three months, by which time the accused employer managed to persuade most of the complaining workers to leave Bahrain with promises of small amounts of money and plane tickets home.

Prosecutions appear to be nonexistent when it comes to unpaid wages, the most common worker complaint, despite article 302 of the penal code that criminalizes “unjust withholding of wages.” Interior and Labor ministry officials appeared to be unaware of this provision when Human Rights Watch met with them in February 2010. In March 2010, after that meeting, Attorney General Ali Fadhul Al Buainain issued a decree mandating criminal investigations and prosecutions in such cases.

Officials in the Ministry of Labor and the Public Prosecution Office told Human Rights Watch they cannot address abuses unless the workers themselves come forward to complain. Workers said they faced obstacles to filing complaints and seeking redress, including a lack of translators at government agencies, lack of awareness about rights, and lack of familiarity with the Bahraini labor, immigration, and criminal justice systems. For example, none of the workers Human Rights Watch spoke with were aware that they had the right to hold onto their passports. Only one worker knew that he could transfer employment without his sponsor’s permission. Many workers did not know where to file complaints. Domestic workers are kept in employers’ homes and find it particularly difficult to raise complaints. Bahraini law does not require employers to give domestic workers any time off.

When workers do file grievances, employers often retaliate with counterclaims alleging the worker committed theft or a similar crime, or “absconded,” subjecting workers to potential detention in deportation centers, deportation, and bans on re-entry. Several workers said they did not lodge an official complaint because they feared an employer’s retaliation.

In mid-2010, the most recent period for which LMRA figures are available, some 40,000 migrant workers in Bahrain were working without proper documentation because their work visas had expired, their sponsoring employer terminated them, or they left their job (“absconded”) without permission from a sponsoring employer. Other workers have active work visas, but work for companies other than the company to which the LMRA issued their visa, usually a shell company set up to obtain and sell visas. These so-called “free visa” workers often do not register complaints with the Ministry of Labor for common abuses like unpaid wages because they fear deportation, imprisonment, fines, or other penalties.

Bahrain’s International Obligations

Bahrain is a member of the International Labour Organization (ILO) and has ratified four core ILO conventions, including both conventions relating to elimination of forced and compulsory labor, and those on the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation. Bahrain also ratified Convention No. 14 (mandating a weekly day of rest for workers in industries, such as construction), Convention No. 81 (on worksite inspection) and Convention No. 155 (on occupational health and safety).

Bahrain is a state party to relevant international treaties, including the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, and the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air.

These treaties obligate Bahrain to protect migrant workers against most labor-related abuses. Article 7 of the ICESCR recognizes “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of just and favorable conditions of work,” including decent wages, safe and healthy working conditions and rest, leisure, and reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay. The ICCPR establishes an individual’s right to freedom of movement, including one’s right to leave any country and enter his own country. The ICCPR provides for security of person and, along with the CAT, the right to be free from cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, requiring Bahrain to investigate and punish acts of cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment even when committed by private actors. In the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, the United Nations General Assembly called on governments to “prevent, investigate, and in accordance with national legislation, punish acts of violence against women, whether these acts are perpetrated by states or by private persons.” A state’s consistent failure to do so when it does take some attempts to address other forms of violence, amounts to unequal and discriminatory treatment, and violates the obligation under CEDAW to guarantee women equal protection under the law.

In its General Comment No. 32, the UN Human Rights Committee, the body of experts that reviews state compliance with the ICCPR, declared that under the ICCPR’s article 14 “delays in civil proceedings that cannot be justified by the complexity of the case or the behavior of the parties detract from the principle of a fair hearing.” Furthermore, according to the HRC, article 14 “encompasses the right of access to the courts,” and that “[t]he right of access to courts and tribunals and equality before them is not limited to citizens of States parties, but must also be available to all individuals, regardless of nationality or statelessness, or whatever their status, [including] migrant workers….”

During the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review of Bahrain’s human rights record in 2008 and again in May 2012, the UN Human Rights Council raised concerns about abuses of migrant workers; in 2007, the committee of experts reviewing Bahrain’s compliance with the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) concluded that Bahrain should extend national labor protections to domestic workers; and the Convention for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) committee in 2005 recommended that Bahrain take all necessary measures to remove obstacles that “prevent the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights by [migrant] workers.”

Although the government of Bahrain has the primary responsibility to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights under international law, private companies also have responsibilities regarding human rights, including workers’ rights. Consistent with their responsibilities to respect human rights, all businesses should have adequate policies and procedures in place to prevent and respond to abuses.

The basic principle that businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights has achieved wide international recognition. The UN Human Rights Council resolutions on business and human rights, UN Global Compact, various multi-stakeholder initiatives in different sectors and many companies’ own codes of behavior draw from principles of international human rights law and core labor standards, in offering guidance to businesses on how to uphold their human rights responsibilities. For example, the “Protect, Respect and Remedy” framework and the “Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights” for their implementation, which were endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2008 and 2011, respectively, reflect the expectation that businesses should respect human rights, avoid complicity in abuses, and adequately remedy them if they occur.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Bahrain

- Ensure speedy and full investigation and prosecution of employers and recruiters who violate provisions of Bahrain’s criminal laws, including withholding of wages and confiscation of passports, and impose meaningful penalties on violators.

- Ensure that Ministry of Labor mediation and judicial procedures address labor disputes involving migrant workers in an effective and timely manner. Ensure that employers who violate the law and regulations receive meaningful administrative and civil penalties.

- Improve the ability of inspectors to address violations of the labor law and health and safety regulations, including by substantially increasing the number of inspectors responsible for overseeing private sector practices.

- Extend all legal and regulatory worker protections to domestic workers, including provisions related to periods of daily and weekly rest, overtime pay, and employment mobility.

- Ratify International Labour Organization Convention No. 189 on decent work for domestic workers.

- Mandate payment of all wages into electronic banking accounts accessible in Bahrain and common sending countries.

- Enforce prohibitions against confiscation of workers’ passports.

- Address limitations on freedom of movement for migrant workers by eliminating the requirement that a sponsor cancel a work permit before a worker can leave Bahrain freely, and, in cases of abuse and exploitation, eliminate the requirement that a worker wait one year before they can change jobs without their employer’s permission.

- Take stronger measures to identify, investigate, and punish recruitment agencies and informal labor brokers who charge workers illegal fees.

- Expand public information campaigns and training programs to educate migrant workers, including domestic workers, and employers about Bahraini labor policies, with an emphasis on workers’ rights and remedies.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in Bahrain in January, February, and June 2010 with the assistance of Coordination of Action Research on AIDS and Mobility-Asia (CARAM-Asia), a regional network of migrant advocate organizations.

Researchers interviewed 62 migrant workers in the greater Manama area—Bahrain’s capital. These workers were employed in various sectors including construction, service industries, and domestic work. Of the 18 who were domestic workers, 15 were living in shelters and three in a recruitment agency office.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed labor lawyers, journalists, social workers, worker advocates, union leaders, representatives of recruitment agencies, and foreign diplomats knowledgeable about the situation of migrant workers. Four researchers visited two recruitment agency offices, three construction sites, the government-run women’s shelter, three shelters run by sending-country embassies, one NGO-run shelter, a judicial hearing, and four labor camps where migrant workers are housed. They also met with officials from Bahrain’s Ministries of Labor, Foreign Affairs, Social Development, Interior, and Justice, as well as representatives of the Public Prosecution Office and the Labor Market Regulatory Authority (LMRA).

Human Rights Watch followed up these interviews by submitting detailed questions to the Ministry of Labor, the LMRA, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in March, April, and May 2010, December 2011, and May 2012. Those letters and the government’s responses are reproduced as appendices to the Web version of this report.

Human Rights Watch provided the government with our findings and recommendations and then held a two-day meeting in September 2010 with representatives of the Ministries of Labor, Foreign Affairs, Interior, Justice, and the LMRA. This dialogue resulted in the government adopting a set of pledges, released in December 2010.

Most of the workers interviewed for this report had already left their employment due to alleged abuses and filed official complaints, and felt relatively free to tell their stories. Other workers who were still employed and feared employer retaliation, or were victims of sexual abuse, or feared deportation because they were working without a valid visa, asked to be identified by pseudonyms, indicated by use of a first name and initial. Some experts, including government officials, also asked not to be identified by name.

In March 2011, while documenting human rights violations in connection with the government suppression of pro-democracy street protests, Human Rights Watch interviewed 12 migrant workers in Manama about attacks on migrants as clashes between anti-government protesters and security forces intensified. These 12 migrants were not questioned about other issues, such as conditions of work. When this report refers to “workers who spoke with Human Rights Watch” or “workers interviewed for this report”—outside the specific section concerning these attacks—it is referring to the 62 migrant workers interviewed about labor issues.

In December 2011 and again in May 2012 Human Rights Watch wrote to Bahraini authorities requesting updated information pertinent to this report. The government’s response, received on May 28, 2012, is reflected in the report.

In July 2012 Human Rights Watch wrote to the five construction companies mentioned by name in the report informing them of the contents of the report and requesting their response. Two of the companies responded; their replies have been incorporated into the report and are reproduced in the appendices to the Web version of the report.

A Note on Terminology

The government of Bahrain does not consider foreigners working in Bahrain to be “migrant workers,” due to their term-limited employment contracts and temporary residence in the country. The government instead uses the terms “contractual workers,” “expat workers,” or “foreign workers.” Under international law, the term “migrant worker” refers to a person who is engaged “in a remunerative activity in a State of which he or she is not a national.” Accordingly, Human Rights Watch considers foreign nationals who live and work in Bahrain under term-limited contracts to be migrant workers.

The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families explicitly regards “seasonal workers,” “project-tied workers,” and “specified-employment workers,” who earn remuneration as a result of their activity in a State where they are not a national, as migrant workers.[1] Although Bahrain is not a party to the convention, this authoritative legal definition of “migrant worker” applies to the workers whose situation this report addresses.

I. Background

Bahrain is a small island nation 25 kilometers off the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia. About half the country’s resident population of approximately 1.3 million people are citizens.[2] The rest are mostly migrant workers. The government puts the number of migrant workers in Bahrain as of early 2012 at just over 458,000, accounting for about 77 percent of the total workforce.[3]

In 1932 Bahrain became the site of the first commercial oil discovery in the Persian Gulf. Over the past decade the economy has diversified.[4] While crude oil production accounts for about 11 to 14 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 75 percent of government revenue, the country has emerged as a trading and investment hub, competing with Dubai and its other Gulf neighbors.[5]

For several decades, Bahrain’s economic development has largely depended on migrant workers, who can be found in every industry.[6] Some of these expatriates work in skilled jobs, professions, or middle management in fields such as finance, education, and import-export companies, while others run companies and themselves employ and sponsor migrant workers. Roughly 85 percent of the approximately 458,000 migrants who are employed in Bahrain work in low-wage and low-skilled jobs.[7] Female migrant workers in Bahrain—about 80,300 in total—tend to be concentrated in domestic work, with approximately 54,600 women working for families as cooks, caretakers, and housemaids.[8]Out of the 377,700 male migrant workers in Bahrain, 115,200, or roughly 31 percent, are in the construction industry; another 23 percent are in retail and wholesale trade; 16 percent are in manufacturing; 9 percent in domestic work; and 7 percent in the hotel-restaurant industry.[9]Additionally, some 8,200 migrants (male and female) almost two percent of the foreign workforce, work in the public sector, including in the lower ranks of the security forces. Another 1 percent work in finance; less than 1 percent work in education.[10]

By comparison, the country’s workforce contains about 140,100 Bahraini nationals, approximately 34 percent of whom work in the public sector.[11] The wholesale and retail trades, manufacturing, construction, and finance combined employ another 38 percent of all nationals in the workforce.[12]

Bahraini companies and individuals “sponsor” migrant workers using renewable employment contracts and work visas, mostly for two years at a time.[13] Once a work permit expires and is not renewed, the worker (and any accompanying family members) must leave the country within one month, regardless of how many years he or she has resided in Bahrain. By law, employers must bear the cost of the repatriation.[14]

The workers interviewed for this report were recruited from both rural and urban areas in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Both male and female, their ages ranged between 20 and 48 years old. Most non-domestic workers paid fees ranging from US$750 to US$2,000 to recruitment agencies in their home countries to obtain employment contracts, Bahraini work visas, and airline tickets.

Once in Bahrain, these migrant workers earned monthly wages ranging from about 40 to 120 Bahraini dinars (BD), equivalent to US$106-US$318. Construction workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch earned between BD60 and BD100 ($159-$265) a month, while a few earned up to BD120 ($318) with overtime. The average monthly construction industry income for male migrants is BD103 ($273) (which factors in management and skilled workers as well as low and unskilled workers).[15] The industry average for domestic workers is BD70 ($186) a month.[16] Domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch earned between BD40 and BD80 ($106-US$212) a month. Worker advocates reported monthly wages to be as low as BD35 ($93).[17]

Many aspects of migrant workers’ lives in Bahrain are closely controlled by their employers. Employers typically house their workers.[18]Construction workers stay in dormitory-style dwellings or labor camps, where employers provide transportation to work and sometimes meals. Workers in manufacturing, retail, and other non-domestic sectors might live in labor camps or group apartments that their employer supplies, and for which they pay rent.

Domestic workers, about 87,400 in total, live in their employer’s home and rely on their sponsor for food and other daily needs. They perform tasks such as cleaning, cooking and serving meals, washing and ironing clothes, shopping, and caring for children and elderly family members.[19] Employers exercise enormous power over domestic workers’ lives due to the fact that domestic workers live and work in their homes. Under the sponsorship system, employers dictate whether domestic workers may leave their employment for another employer in Bahrain, or must return to their country of origin. Legally, domestic workers are excluded from many of Bahrain’s labor protections and inspection mechanisms. Many Bahraini employers view themselves as the guardians of their domestic workers.[20]

Bahrain’s system of employment-based immigration, commonly called the kafala (sponsorship) system, exacerbates abuses faced by migrants and impedes their freedom of movement. Under the kafala system, a migrant worker’s employment and residency in Bahrain is tied to their employer, or “sponsor.” In a meeting with Human Rights Watch, Dr. Majeed Al Alawi, then minister of labor, stated that “the kafala system is near slavery.”[21]

Employers unduly influence a worker’s freedom of movement because they must cancel work visas before migrants can quit their job and leave the country (unless this requirement is waived by a senior immigration official). Until August 2009, employers also dictated if a worker could change jobs within Bahrain before the employment contract ended. The system gave employers enormous control over migrant employees and allowed employers to force migrant workers to continue working in abusive conditions. Now workers can change jobs without their employer’s consent so long as they have been with that employer for at least a year.[22]

In recent years, the plight of migrant workers in Bahrain, as elsewhere in the region, has received increasing attention. Bahraini and regional media, particularly English-language publications, have provided coverage of migrant worker grievances. Hardly a day passes without a media outlet recounting a tale of abuse and exploitation of migrant workers.[23]

Numerous worker strikes and demonstrations—mainly in the construction industry and sometimes involving thousands of workers—have raised public awareness regarding the scale of grievances in Bahrain.[24] “Most of the strikes happen when workers are not happy about the living conditions, non-payment of salaries or low wages,” said Salman Al Mahfoodh, secretary-general of the General Federation of Bahrain Trade Unions (GFBTU), the country’s sole trade union federation.[25] Bahrain is one of the few Gulf States that allow migrant workers to join unions, although membership remains rather low.[26] The GFBTU has nonetheless helped migrant workers stage strikes, and migrants have also organized independently—including a strike involving some 5,000 workers against the al-Hamad construction company, in which the workers recovered several months of back wages.[27]

Bahraini civil society organizations, unregistered migrant worker associations, human rights organizations, expatriate cultural organizations, and the GFBTU have also served as sources of advocacy and information, particularly the Migrant Workers Protection Society, Bahrain’s leading migrant rights NGO. Some foreign embassies have also stepped up advocacy on behalf of their nationals by meeting with the Ministry of Labor, providing lawyers and other resources for aggrieved workers, and opening shelters for domestic workers.

Internationally, United Nations human rights bodies have highlighted the treatment of migrant workers in Bahrain. UN Human Rights Council member states raised the issue of migrant worker rights during Bahrain’s 2008 and 2012 Universal Periodic Review (UPR).[28] In 2007, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women expressed concern with “the poor working conditions of female migrant domestic workers.”[29] The committee called upon Bahrain “to take all appropriate measures to expedite the adoption of the draft labor [law], and to ensure that it covers all migrant domestic workers,” and “to strengthen its efforts to ensure that migrant domestic workers have adequate legal protection, are aware of their rights and have access to legal aid.”[30] The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in 2005 recommended that Bahrain take all necessary measures to extend full protection from racial discrimination to all migrant workers and “remove obstacles that prevent the enjoyment of economic, social, and cultural rights by [migrant] workers.”[31]

II. Abuse and Exploitation of Migrant Workers

Recruitment Process

Recruitment of migrant workers to Bahrain takes two forms. The first involves recruitment companies in sending countries working on behalf of, or in coordination with, Bahrain-based recruitment agencies that local employers pay to find workers.[32] This arrangement is the norm for domestic worker recruitment, but is also used in other sectors.

The second practice, common in the construction sector and other non-domestic low-income sectors, involves a migrant worker finding employment through an informal middleman— often a friend, family member, or acquaintance already in Bahrain. Sometimes Bahraini employers approach these middlemen and ask if they know anyone who wants a job. Sometimes would-be migrant workers ask their contacts in Bahrain to find them a job. One Manama-based document clearance agent, responsible for submitting work visa applications for Bahraini companies, explained:

The normal way is that the worker there back home tells his friends to find a job for him. Maybe more than 80 percent is like this. Then the friends living outside start speaking to the people, “Find a job for my nephew, for my cousin, for my brother.” It’s depending on the person, how active he is, and how connected he is.[33]

Bahrain’s Law No. 19 (2006), entitled Regulating the Labor Market, permits only persons licensed by the Labor Market Regulatory Authority (LMRA) to “carry out the business of a recruitment agency or employment office.”[34] This applies to employers who directly recruit migrant workers, as well as to those companies that act as intermediaries in the recruitment process.[35] Prior to 2006, recruiters required a license from the Ministry of Labor.[36]

Under the law, employers must pay certain fees to the government for each foreign worker they recruit into the country. These charges include a fee for work visas and residence permits totaling over BD220 (US$584).[37] In addition, employers pay recruiters, fixers, and document clearance agents service fees, and provide workers with airline tickets to travel from their home countries to Bahrain.[38] The LMRA also used to charge employers BD10 ($27) per month per migrant worker. This fee was designed to raise the cost of hiring foreign workers, making Bahraini labor more competitive in the market.[39] Starting in April 2011, the LMRA suspended the fee, following intense lobbying by employers and in the context of a far-reaching campaign of repression against pro-democracy protests that some cited as crippling the economy.[40] Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa ordered a freeze on the 10 BD fee until June 31, 2012 and on July 6, 2012 the government announced the freeze would be extended until the end of the year.[41]

Bahraini law explicitly forbids Bahraini recruiters from collecting any of these fees and travel costs from prospective migrant workers.[42] Officials with licensed and regulated recruitment agencies that place the domestic workers told Human Rights Watch that they generally complied with this law. However, when it comes to construction and other sectors, some recruitment agents and employers appear to openly flout the prohibition by requiring that prospective workers reimburse them for these fees.

For workers in construction, manufacturing, and other non-domestic sectors, Bahraini sponsors or informal recruiters commonly solicit agencies located in sending countries to handle the visa applications of would-be migrant workers. These local agents compel workers to bear travel and other costs. A Manama-based document-clearance agent told Human Rights Watch that recruitment agencies or employers often have an office liaison in sending countries. The agent added:

As per the rule, all tickets have to be paid by the sponsor, [but] usually [the workers] pay for the visa and for the ticket. But this is all under the table— officially nobody pays any money and nobody takes any money [but] normally the agency has a placement fee, and it’s two months’ salary, and then they charge the sponsor also here, which they call recruitment fees. No way is this done officially, and if the sponsor takes money then the [worker] can go to court and say this person has taken the money.[43]

All but one of the 44 male workers Human Rights Watch interviewed had the same experience of being required to pay up-front sums ranging from $750 to $2,000 to their recruiting agents in exchange for work visas and airline tickets. These fees are equivalent to approximately 10 to 20 months of most migrant workers’ wages in Bahrain.

Muhammad Rizvi Muhammad Siddeek, a 38-year-old Sri Lankan driver, told Human Rights Watch he had come to Bahrain to earn enough money to pay for surgery for his father and young son:

I paid money to an agent named Ali Zamir Employment Agency in Katunayake area near my house in Sri Lanka. I told him I needed a job as a driver. He said, I will get you a Bahraini visa and send you. I paid 83,000 [Sri Lankan] rupees [US$729]. I sold my wife’s gold for the money.[44]

Sabir Illahi is a 33-year-old mason from Rajasthan, India, who had never left his home country before coming to Bahrain in early 2009. He said:

I knew a man from Rajasthan [already in Bahrain]. He got my visa. I paid 80,000 rupees [$1,725] for the visa. [To get the money] I gave the papers to my land to a man [in India].

In Rajasthan, I got my visa from a relative. The engineer of the company here [in Bahrain] sent the visa to him, that man gave the visa to me. I gave him 80,000 rupees, and I got a ticket to come here, and a visa.[45]

Purveen G., one of 13 men from India working as a laborer for a major construction firm, summarized their experience:

We all came through an agent, paying 50,000-60,000 rupees [$1,300-$1,355] in India. This cost covered all expenses. We came directly to the company once in Bahrain. Some of us mortgaged our properties, lands and homes, with interest.[46]

Domestic workers whom Human Rights Watch spoke with seldom had to pay the fees that other low-income migrant workers did. Instead, industry practice is for the sponsoring family to cover expenses associated with recruitment, including visa costs, air travel, and an additional payment to a Bahraini recruitment agency.[47] Nonetheless, in some cases recruiters in sending countries do force domestic workers to pay fees. Fareed al-Mahmeed, chairman of the Bahrain Recruiters Society, told Human Rights Watch that it was not uncommon for recruiters to charge domestic workers fees in their home country.[48] Maria C., a migrant domestic worker from the Philippines, told Human Rights Watch:

There was a recruiter who came to my house and offered me and my family [a chance for me] to come to Bahrain. She said I would earn a lot of money if I came here—money that I could use to support my family. She asked me to pay her for my visa fee, my employment fee, [and] other fees before I leave the Philippines. We paid 35,000 [Philippine pesos, or $756] in the Philippines. [To raise the money] we sold our motorcycle. Then I came to Bahrain. My sponsor picked me up from the airport and I signed a contract at my sponsor’s house.[49]

While it is illegal under Bahraini law to force workers to pay recruitment fees or to cover the cost of visas and travel, a study conducted by the LMRA found that 70 percent of migrant workers secured jobs in Bahrain by borrowing money or selling property in their home countries.[50] Fee payments and debt contribute to an exploitative employer-employee relationship. Workers who arrive with sizable debts—like Suresh Podar, a laborer from Nepal—are less likely to feel they can complain or leave exploitative work conditions for fear of losing their jobs and the right to remain legally in Bahrain. Suresh, who came to Bahrain on his cousin’s recommendation, said:

My relative was already in Bahrain working on my sponsor’s boat and got me a job. My relative knew an agent in Nepal who arranged everything. We gave him 30,000 Nepalese rupees [$425] and gave [BD] 200 [$531] to my sponsor when we got here. I wasn’t told I’d also have to pay my sponsor. I was told I’d work in a garage as a helper but when he got here we were told to work on a fishing boat. I can’t swim and didn’t want to work on a boat. But since I already paid so much money to get here I decided to stick with it.[51]

Making matters worse, some workers raise money at home for the visa fees and travel by borrowing at exorbitant interest rates, sometimes using family valuables or property as collateral. Suresh recalled:

I had borrowed the money from my brother. My brother had to borrow the 30,000 [rupees, $425] from someone else and my brother has to pay interest. I pay my brother. [After about two years] I have paid back 20,000 [$283] out of 30,000, but I still need to pay back another 40,000 [$567], so 60,000 [$850] total.[52]

Sant Kumar, Suresh’s cousin, said he had to pay interest and offer collateral.

On average, for every thousand [Nepalese rupees, $14] I borrowed I have to pay back about 1,300 [$18]. I borrowed 30,000 from one [lender] and 30,000 from another. I put my house up for collateral. It’s my own house so I don’t pay rent but if I don’t pay what I owe they will take my house.[53]

Passport Confiscation and Mobility

Bahraini law prohibits employers from confiscating their employees’ passports. The government has explained that the practice is criminalized under the anti-human trafficking law and article 389 of the penal code, but employers continue to routinely confiscate their employees’ passports, typically retaining them for the duration of employment.[54]

All 62 workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said their employers had confiscated their passports on arrival in Bahrain. In 2008 and 2009, the Ministry of Labor’s Individual Complaints Department received 1,583 complaints from workers seeking their passports.[55] Moham Kumar, India’s ambassador to Bahrain, observed that most cases of passport confiscation take place at what he called “smaller companies.”[56]

By withholding workers’ passports, employers exercise an unreasonable degree of control over their workers and create significant impediments to a worker’s ability to leave his or her abusive employer, or return to his or her home country.

Rules governing how employers “sponsor” workers and work visas exacerbate this problem. A worker who wants to return home not only needs to repossess his or her passport, but also to secure the employer’s agreement to cancel the employment visa. Migrant workers unable to meet these official requirements for leaving the country risk penalties for violating local immigration laws, including detention and deportation.

Eight workers reported that their employers asked them for money in exchange for returning their passports and canceling their work visas—a common practice according to an immigration officer.[57] Bahrain media reported similar stories of workers being asked to pay employers before they received their passports.[58]Two workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch who filed complaints with the minister of labor and labor courts became frustrated by the ineffectiveness of the government’s remedial process and eventually agreed to pay their employer in order to leave Bahrain.[59]Another four workers reported that their employers asked them for money before cancelling their work permits so they could move to new jobs.[60]

After arriving in Bahrain from Bangladesh, Mukhtar Mojibur Rehman learned there was no job waiting for him, even though he had a valid work visa.[61] Mukhtar’s recruiter told him that authorities would deport him if he reported the recruitment fraud. Having paid fees to come to Bahrain, Mukhtar spent several months trying to secure employment and worked odd jobs, including a four-month stint as a vegetable gardener for which he was not paid. Frustrated by his lack of steady employment and income, he decided to return home.

I called up this guy who set up the visa and I told him, okay, fine, I’ll go back. He said the sponsor wanted 500 dinar [$1326], [he] won’t let you go unless you pay him. I told the man that I would pay the 500 dinars. But then he said, “No, your sponsor [now] wants 1000.”

I don’t know if my sponsor or my employer has my passport. So, I know I need an out-pass.[62]

An out-pass is a one-time travel document issued by the relevant embassy or consulate allowing a worker to leave Bahrain and return to his country of origin. Migrant workers frequently must apply for out-passes after failing to retrieve their passports. Mukhtar Mojibur Rehman described his experience to Human Rights Watch:

I’ve been trying to get an out-pass. I went to the Bangladeshi embassy two months ago to get an out-pass and they told me to come back after two days. Two days later they told me there are 1,200 people who’ve applied. [Three days ago] they told me there’s 200 left [waiting ahead of me]. Once their papers are processed, yours will be done.[63]

Like Rehman, dozens of workers told Human Rights Watch how they wanted to leave their employment and return home, often after experiencing abuse or extended periods of nonpayment. None were able to retrieve their passports and return home without help or paying off their employer. Most workers tried to seek government assistance to retrieve their passports, a process that can take between several weeks and several months, with mixed results. Most who eventually left the country did so on an out-pass.

Immigration and Ministry of Labor officials do not have any power to force employers to return passports.[64] Neither do the police, at least not without a court order. Beverley Hamadeh of the Migrant Workers Protection Society described what happens when workers appeal to the courts to get their passports back.

Court orders are sometimes used to enforce the return by the employer of the illegally held passport to the employee. The employer may return [the passport], but fail to cancel the visa, which is critical for the repatriation process. This often also occurs when the [Ministry of Labor] arbitrator agrees with the employer to return the passport.[65]

Attorney Maha Jaber told Human Rights Watch that she had secured orders for the return of her clients’ passports from Bahrain’s Urgent Matters court. “It could take three to four weeks, but as soon as I have a judgment we execute it through [appealing to the] execution court,” she said.[66]

The government told Human Rights Watch that passport confiscation is criminalized under the penal code’s article 389 and the anti-human trafficking law.[67]

Penal code article 389 specifically prohibits acquiring a document by “force or threat.”[68] Nearly every workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had given their employer their passport because the employer told them to, or told them it was standard practice. All these workers said they were unaware that it was illegal for an employer to confiscate their passports. It remains unclear whether these types of cases are prohibited under the penal code’s “force or threat” requirement.

Bahrain’s human trafficking law also provides criminal sanctions for labor-related “exploitation” similar to forced labor.[69] Brig. Tariq Mubarak Bin Daineh, then undersecretary of the Ministry of Interior, explained that it “is not [explicitly] in the human trafficking law that holding the passport is a crime, but there is a trend now between the police and the Public Prosecution to treat this as [the crime of] human trafficking.”[70] However, when asked about the criminality of withholding passports, Attorney General Al Buainian told Human Rights Watch that the Public Prosecution had yet to determine if confiscating a passport and withholding it was a crime or an act of human trafficking—even when coupled with extensive withholding of wages by the employer.[71]

Advocates with the Migrant Workers Protection Society’s Action Committee said they were unaware of any employer being punished for withholding a passport.[72] When pressed by Human Rights Watch, officials in the Ministry of Labor, Ministry of Interior, and Public Prosecution Office could not give any example of punitive measures, criminal or administrative, taken against employers who withheld passports. Nadia Khalil al-Qaheri, head of the Labor Complaints Section at the Ministry of Labor, told Human Rights Watch that all her department could do was either request the employer to return the passport or refer a worker to seek assistance through the Ministry of Interior or the courts.[73] Lt. Col. Ghazi Saleh al-Senan, director of Follow Up and Investigation at the General Directorate of Nationality, Passport and Residence (i.e., Bahrain’s immigration directorate) in the Ministry of Interior, said that when his office gets involved, employers either return the passport or claim not to have it.[74]

One immigration officer who deals directly with these cases told Human Rights Watch that he can only request—rather than compel—employers to return the passport and release the visa.[75] He calls the employers twice and then sends a summons via the police to appear at immigration. If the employer ignores the officer’s requests after three attempts—which the officer indicated sometimes happens—or refuses to agree to release the work visa, the officer submits a written report to a senior immigration officer, who is empowered to waive the visa cancellation. But the waiver process takes weeks, even months, and workers still need to either seek their passport through the courts or apply for an out-pass.

Lt. Col. al-Senan told Human Rights Watch that employers “do not have the right to take passports.” He explained that if the immigration officers receive complaints of confiscation, “We contact [the employer] and ask him to return the passport.” He discounted the problems this practice raises, saying, “The passport with the sponsor is nothing, not an issue. If he wants to leave the country or transfer to another sponsor the passport is not needed.”[76]

Contrary to Lt. Col. al-Senan’s dismissive comment, passports remain vital documents that workers need, not only to leave the country freely, but also to secure valid employment and residency in Bahrain. The only way workers can leave employers and legally stay in Bahrain is by changing employers. Starting in August 1, 2009, migrant workers in Bahrain—except for domestic workers—could freely change jobs through the LMRA without their employers’ consent. Ali Ahmed Radhi, then chief executive officer at the LMRA, told Human Rights Watch that all LMRA services, including employment transfers, could be done without passports using various identification methods, even fingerprints. According to Radhi:

Provided that information regarding the foreign worker is already in the LMRA database, the LMRA does not require the employer who is applying for the new work visa to produce the original passport; a copy of the passport would suffice for the purpose of applying for a new work visa.

He added that:

After the issuance of the work visa, the foreign worker will eventually be required to produce his passport, not to the LMRA, but to [immigration officials] for the issuance of the residence permit.[77]

However, several members of the Migrant Workers Protection Society, as well as other migrant worker advocates, told Human Rights Watch that they have difficulty accessing any LMRA or immigration services for a worker without his or her passport.[78] They also said that attaining a waiver of a visa cancellation can be complex and time-consuming. Advocates complained of a disconnect between the simple process described by top government officials and the bureaucratic obstacles they encounter in reality when seeking assistance for their clients. Marietta Dias observed:

If you go talk to the ministers and look at the law everything is perfect and nothing can’t be handled. But when you go to the little guys [in the ministries], the guys that process everything, they either don’t have the authority to do anything or they haven’t been told the law.[79]

Unpaid Wages

One of the main complaints that migrant workers voiced to Human Rights Watch was that their employer failed to pay their wages in full or on time. Unpaid wages are the most common issue in labor disputes mediated by the Ministry of Labor, and a frequent reason for workers leaving employment.[80] Media reports and migrant labor advocates suggested the international credit crunch starting in 2008 may have exacerbated the problem.[81] In April 2012, Indian Ambassador Moham Kumar told the independent daily Al-Wasat that the largest issue currently facing Indian workers was non-payment of wages for periods of several months, which he attributed to a struggling economy.[82]

The Individual Complaints Department at the Ministry of Labor, which mediates labor disputes between employers and employees, received 227 complaints of withheld and late wages in 2007, 792 complaints in 2008, 987 complaints in 2009, and 356 complaints in the first quarter of 2010, the most recent figures available to Human Rights Watch.[83] The government failed to reply to Human Rights Watch’s requests for 2010 and 2011 numbers. The Ministry of Labor also houses a department of inspections that is charged with monitoring compliance with Bahrain’s labor law and health and safety standards. This department, which mainly gets involved in situations of large-scale non-payment of wages, received nine complaints specifically regarding unpaid or late wages, out of a total of 203 complaints in 2008.[84] In 2009, the number of complaints of unpaid or late wages that the department of inspections received rose significantly to 140 out of a total of 371 complaints.[85]

Just over half of the migrant workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their employer had withheld their wages. This complaint was especially common among construction workers. All of these workers were still owed back wages when they were interviewed. Their employers had not paid them any wages for between three and ten months. One domestic worker had not been paid in five years. In a few cases, workers received a full or partial monthly wage in the midst of extended periods of non-payment. [86]

Withholding wages violates the Bahraini labor law and is also a crime under the penal code.[87] Moreover, the impact on workers whose wages are withheld for even one month is very serious: they immediately fall into arrears on debt they owe in their home countries; they can incur additional interest; and they are unable to send money home to their families, which depend on the income earned in Bahrain. Unpaid workers must often run tabs at local stores or borrow additional money from friends just to buy food and necessities.

Acihi binti Mahid, a domestic worker from Indonesia, worked for her sponsor in a two-story house in the al-Budaiya suburb of Manama. “I cleaned, cooked, and took care of three babies. I expected that the sponsor could pay the salary,” Mahid told Human Rights Watch.[88] Instead, she went unpaid for the entire seven months she worked for the employer.

I was supposed to be paid 70 dinars [$186] as promised by an agent in Indonesia. I expected to receive money from the sponsor every month. I asked the sponsor for my pay so many times. He said, if you want to send the money to Indonesia I’ll to give it to you … I asked so many times but never got it. I need to send money to my family. I send it to my father. My parents take care of my nine-year-old daughter.[89]

Lawrence Sarwan Singh, a 37-year-old tile mason, left his parents, sister, wife, two sons, and a daughter in Mumbai to work for a Bahraini manpower agency that supplies workers for building projects. Singh told Human Rights Watch:

I was one of 46 men working for a supply company. We were told we’d receive 100 dinars [$265] a month and up to 120 dinars [$381] with overtime ... We used to go ask for our salaries three days before the salary was due. They would sometimes give us 50 dinars [$133] 0r 70 dinars [$186]. They’d say it was a new company and whatever is left will be given to you later … We had to sign the [receipt of full payment]. They would threaten us and beat us to make us sign. The Bangladeshi foreman said if we didn’t sign the paper, we would not get our salaries. Eventually I didn’t get paid for a month-and-a-half. I called my employer and asked to return home.[90]

Singh told Human Rights Watch that his employer refused to send him home. “After he didn’t pay for another month-and-a-half, I left,” he said.[91]

Government policies require that employers must show receipts signed by their employee for each periodic wage payment before the migrant worker can leave Bahrain.[92] As Lawrence’s case demonstrates, abusive employers can easily induce migrant workers to sign such documents through fraud or intimidation.

Every month, Acihi binti Mahid’s employers forced her to sign for payments she did not receive.

I signed one piece of paper with seven signatures, once for every month. I signed the paper myself; I understood it was to say I got my salary. But I did so because the sponsor said, “Your money will be kept with me till the end of the contract because no housemaid here keeps her money.” It’s always kept by the sponsor.[93]

Since 2008, migrant workers from various construction and other companies have organized strikes and demonstrations, drawing national media coverage. One group of protestors worked for a large construction firm, Muhammad Ali al-Asfoor al-Badyah Contracting, which was building several major mosques in Ras Ruman and Isa Town, among other projects.[94] On October 24, 2009, about 38 al-Asfoor employees demonstrated outside the Indian embassy in Manama.[95]

According to a Gulf Daily News account, the carpenters, painters, masons, and laborers had not received their salaries (between BD80 and BD90, or $212-$239), for five months.[96] The workers told the paper that they had been physically and verbally abused when they asked for their due. “We … incurred the wrath of al-Asfoor,” said Vishnu Naraya, who had been with the company 12 years.[97] One striker, K. S. Prasad, told a reporter:

We are suffering as the company didn’t pay us for five months … We have families and it is so difficult to convince them that the owner didn’t pay us, as they think that we are working outside India and therefore are earning a lot of money. They don’t know what’s our condition here. We don’t get what we deserve.[98]

These strikers, all Indian citizens (joined by 4 more workers for a total of 42), lodged official complaints with the Ministry of Labor and the police in October 2009. In January 2010, they filed a civil case and criminal human trafficking complaint against their employer with the help of the Indian embassy and an embassy-hired Bahraini lawyer.[99]

Human Rights Watch interviewed three of the al-Asfoor employees on February 1, 2010, all of whom said they had not yet received any back wages, just over three months after they went on strike and first filed a complaint with the Ministry of Labor.[100]

One of the workers, Sabir Illahi, said he came to Bahrain to work as a mason in early 2009 on the promise of earning BD90 ($239) a month plus overtime. After working five months for nearly no pay, he said, he left al-Asfoor Contracting and tried in vain to recover his back wages and get permission to seek new employment or return to India, first by appealing to the employer and then by filing a complaint with the Ministry of Labor. The ministry forwarded the case to the labor court. Illahi says he was left without income for 11 months and lost his family home in Rajasthan.

I received only one [full] salary, and for the other months I got BD27 [$72], but signed for the full amount. The foreman said, “You’ll get the rest in two days, it’s not a problem, so just sign it.” When he said that, I signed it.

After working for five months, I asked for my money but they didn’t give me my money. [The site engineer] told me, “Do your work; I’m not going to give you money. We’re only going to give you money for food, BD15 [$40] for 30 days.”

I told him, don’t give me money for food, send me home—I paid 80,000 rupees ($1705) on my house and I have to give it back. He said, “There is no money, go to the Labor Ministry, go to the embassy, you won’t get your money.”

I came [to Bahrain] and I can’t even read or write much. I had never left my country before.

I asked him to let me go home, leave the salary but I want to travel back home – but he said we won’t send you back. So I left. Then, I told my sponsor, give me a release, so I can work somewhere else, but he said “I will not give you a release, if you want to work, then work in our company.” I know that I could earn money somewhere else if he gave me a release, but he says he will not give me a release.