Text by Andrea Carvalho and Cesar Muñoz Acebes; Geospatial Analysis by Léo Martine; Design Direction by Grace Choi; Graphics by Ivana Vasic; Development by Christina Rutherford; Video Production by Laura Prieto Uribe

A fire started along a dirt road that traverses Terra Nossa, an Amazon settlement intended to strike a balance between small-scale agriculture and forest preservation. It was August 11, 2022, the middle of the dry season. A small-scale farmer saw about 10 men with one-liter gasoline bottles, methodically starting the flames along a four-kilometer stretch of the road. Soon the blaze reached the settlers’ plots, consuming banana trees, dragon fruit, and manioc gardens. “I simply just cried,” the farmer told us.

Everybody in Terra Nossa knew the men. They call them fazendeiros, large landowners, although any claims the men might make to legal ownership of the land they control are extremely dubious. Along with them were their hired guns.

Satellite images collected by Human Rights Watch show the fire beginning on August 11 at the location described by the farmer.

The blazes raged inside Terra Nossa for a month, destroying not just the residents’ plots but parts of the forest reserve, which had already been stripped of valuable timber. Videos recorded by residents—whose location we confirmed—reveal the devastation.

In October, the fazendeiros’ men brought grass seeds to the burned areas within the Terra Nossa reserve to turn them into pasture and illegally take them over, residents told us.

The Terra Nossa case shows how land seizure and environmental destruction in the Amazon is causing a loss of livelihoods and subsequent poverty. “They’re taking away our income, killing us little by little,” a resident told us.

Those who speak up against such destruction risk their lives. Community members believe that criminal groups operating inside Terra Nossa have killed at least four people since 2018. Another person is missing and believed dead.

The plight of Terra Nossa repeats itself, with small variations, across the Amazon. Indigenous people and other local communities that live off small-scale farming and fishing, and the sustainable use of the forest, are trying to hold on to their land and protect the environment and their livelihoods before the onslaught of criminal networks involved in illegal logging, landgrabs, mining, and poaching.

Terra Nossa settlement, where illegal logging takes place, September 30, 2019.

Trucks carrying illegally harvested logs exit the Terra Nossa settlement, September 30, 2019.

A field sown with soy within the Terra Nossa settlement, October 3, 2021.

For years, we have travelled to some of those communities and documented how environmental destruction goes hand in hand with violence. More than 300 people have died in conflicts over the use of land and resources in Brazil’s Amazonian states in the last decade, the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) reports. We examined scores of investigations into those cases and found glaring failures by officials that made it very difficult to hold killers accountable, including cases in which the police did not visit the crime scene or arrange for an autopsy.

The situation worsened after Jair Bolsonaro took office as president on January 1, 2019. His administration sabotaged environmental law enforcement. It virtually paralyzed the administrative system that processed environmental fines and removed career officers from leadership positions after their successful operations against illegal mining. It refused to title Indigenous territories at the same time that it issued regulations that facilitated encroachment by outsiders. It defended people involved in illegal mining and logging, and said that environmental protections “harm” development in the Amazon. The results were devastating.

The total area deforested in the Amazon in 2022 was 53 percent larger than the area deforested in 2018, the year before Bolsonaro took office. In 2022, the number of hot spots, the indicator of fire activity used by analysts of satellite imagery, was the highest since 2010.

It is critically important for President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who took office on January 1, 2023, to take urgent measures to protect both the Amazon and its people by reestablishing the rule of law in those areas.

Terra Nossa’s Plight

Terra Nossa’s history is plagued by government neglect, environmental destruction, and violence.

The National Institute of Colonization and Land Reform (INCRA), a federal agency, created Terra Nossa in 2006 as an “Environmentally Sustainable Project.” Poor farmers received plots for small-scale agriculture and have access to a forest reserve within the project’s boundaries, where they can forage for valuable Brazil and babassu nuts and other forest products for sale – their main source of cash. Farmers cannot sell their plots without INCRA’s authorization—to prevent large landowners from gobbling up the land.

Yet protection has been just on paper. Landowners and speculators have carried out “systematic and persistent attacks” on the land and its natural resources, federal prosecutor Gabriel Dalla Favera de Oliveira told us.

In addition, a gold mine is operating inside Terra Nossa without adequate permits, the Pará Federal Prosecutor’s Office asserts. After prosecutors warned of its possible impact on Terra Nossa residents and the nearby Baú Indigenous Territory, a federal court suspended its license in August 2022. Yet, the mine continues to operate, a resident and a federal prosecutor told us.

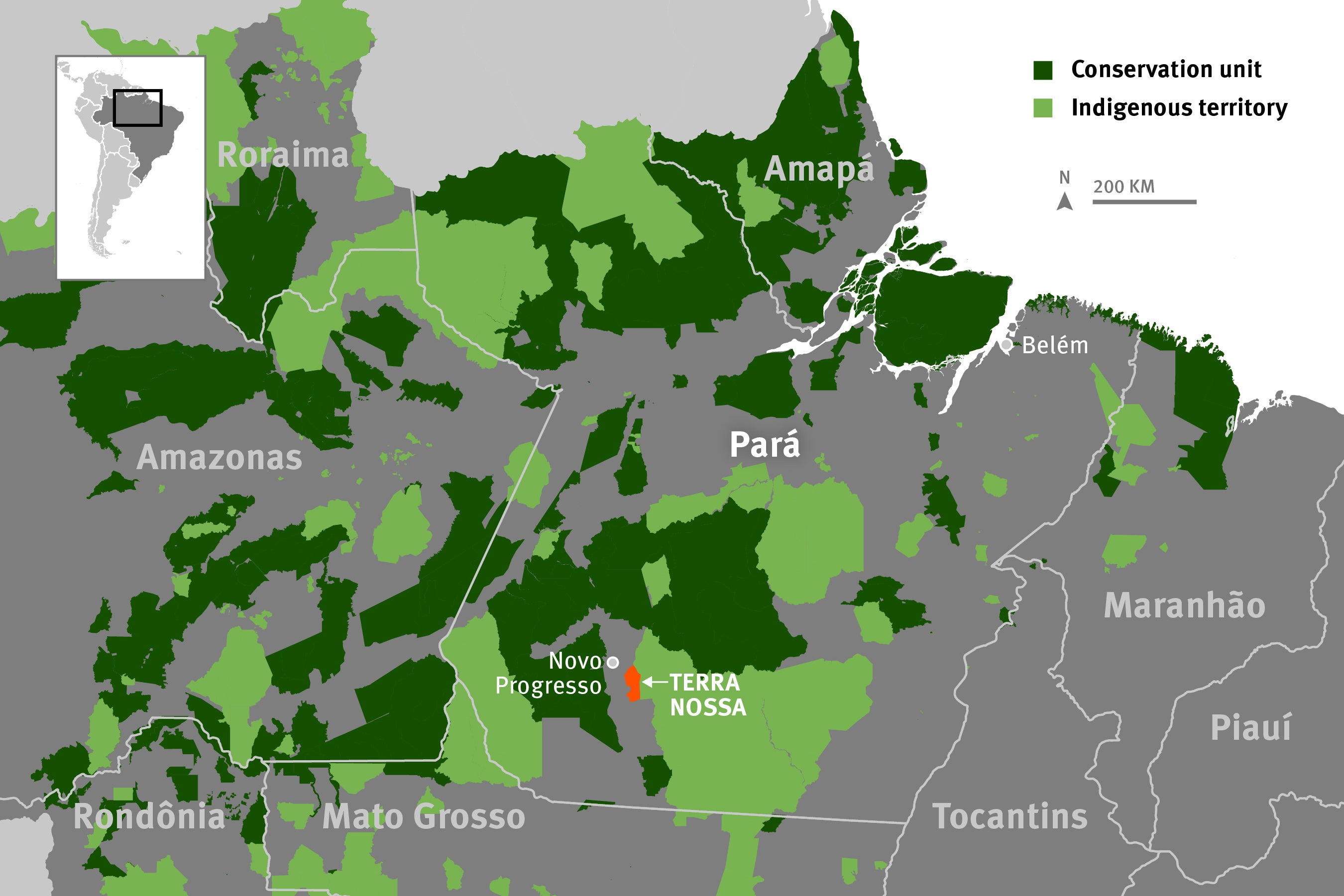

Located in vast Pará state, Terra Nossa stretches over Altamira and Novo Progresso, which are consistently among the municipalities with highest rates of deforestation and fires. The settlement is near BR-163, a main road cutting through the Amazon that facilitates access to forests. Networks of small dirt roads spreading from it look like arteries of destruction on satellite images.

In 2015, powerful fazendeiros persuaded INCRA to reduce the size of the settlement from 149,000 hectares (525 square miles) to about an eighth of that. The federal prosecutor’s office had the reduction overturned within three months, and in 2020, a federal court in Pará convicted three INCRA employees for illegally reducing the size of the settlement.

But encroachment onto the settlement continued.

Terra Nossa was designed to settle a thousand families, but INCRA inspectors who visited in 2016 found that only 291 plots were in the hands of rural workers. Another 130 were either held by people who had illegally occupied the federal land before the settlement was established or had illegally taken over plots afterward. The inspectors found illegal logging and mining within the settlement.

Their report called on INCRA to take action for “immediate reclamation” of areas controlled by people involved in illegal land-grabbing. In June 2022, INCRA told us that it had not yet managed to officially notify the illegal occupants, a step necessary for eventual recovery of the land, a delay that the federal prosecutor Oliveira calls “unjustifiable.”

The agency’s complacency has allowed more and more encroachment and violence, residents told us.

In 2017, a local farmers’ association started reporting to federal and state prosecutors, as well as environmental agencies, that fazendeiros were using the settlement’s dirt roads to transport their illegally harvested timber and employing armed men to protect their activities. Filing these reports put farmers at great risk.

In 2018, one resident and a trade unionist were killed and another resident disappeared after they told residents they intended to talk to police about the fazendeiros’ activities. A brother of one of the victims, who lived in the nearby town of Novo Progresso and distrusted the police, started to investigate the case and was killed soon after.

Residents told us they believe that armed men working for the fazendeiros killed all four men. A man was convicted in the murder of the unionist, and a trial is pending in the killing of the Novo Progresso resident, public court records show. We asked state prosecutors in Pará for information on the other two cases but have not received a response.

Starting in 2019, when Bolsonaro took over as president, his statements and policies undermining environmental protection sent shock waves across the Amazon, including Terra Nossa.

In August of that year, there were massive fires in the settlement, part of a coordinated plan by fazendeiros to set ablaze areas along the BR-163 road that they had previously deforested to convert them to pasture and soy monoculture. They started the fires on August 10, which became known as “the Day of the Fire.”

Meanwhile, criminals keep threatening Terra Nossa community leaders. They have sent intimidating messages and phone calls, filed false complaints against the community leaders at police stations, and pointed guns at them, residents and prosecutors told us.

In 2020, federal prosecutors in Pará said in a public statement that illegal land-grabbers had “installed a regime of terror” in Terra Nossa “with constant threats and violence against the legitimate settlers.”

Yet nobody has been held accountable for the threats against Terra Nossa residents, a community leader told us.

Trauma and fear hang over Terra Nossa like a pall. Community leaders are afraid of leaving their houses, either to meet friends or seek health care, and residents avoid entering the forest reserve to forage for nuts and fruits. Many are struggling with the psychological impact of living this way. The government’s “absenteeism,” as Oliveira puts it, has allowed “the strongest to prevail.”

On July 10, 2022, another Terra Nossa resident was shot dead. Before the killing, he told other residents that he had confronted a man who was entering his plot of land to access the forest reserve and illegally log there, residents told us.

A month later, three years after the “Day of Fire” of 2019, Terra Nossa burned again. More than a hundred families lost their crops, a resident told us. Satellite images show the fire spread to a neighboring Indigenous territory. Some national media ran stories about the fires in Terra Nossa, and yet they raged for a month, a testament of the authorities’ failure to respond adequately.

In Terra Nossa, setting fires is part of a strategy to intimidate the residents, destroy their livelihoods, and force them to leave, Oliveira told us. Residents also said fazendeiros continue to cut down the Brazil nut trees that survived the fires, eliminating a very important source of income. “They put pressure until you flee to save your life, and then they take over the land,” a resident said.

Federal and state authorities are fully aware of the toxic combination of environmental and livelihood destruction and violence in Terra Nossa. We included the case in a 2019 report that we presented at a hearing in Brazil’s Congress and that received worldwide media coverage. And just in 2022 we sent seven letters to authorities alerting them of the serious problems in the settlement. In August, more than 50 local organizations called on authorities to protect the small-scale farmers there. Federal prosecutors, too, have urged INCRA to expel illegal land-grabbers from Terra Nossa.

After we and partner organizations told authorities that some local police officers had reportedly threatened Terra Nossa residents, Pará’s security secretary told us that the whole military police battalion covering the area had been replaced.

But much more needs to be done, and all eyes are on President Lula.

The Task Ahead

Lula inherited one of the highest Amazon deforestation rates on record when he became president in 2003. By the end of his first tenure, in 2010, the total area deforested had dropped by 67 percent compared to 2002, the year before he took office.

Under the leadership of environment minister Marina Silva, the Lula administration accomplished this, in part, through effective enforcement of environmental laws, the creation of protected areas, the demarcation of Indigenous territories, and restrictions on access to credit for large landowners who had taken over public land and lacked legal title or had violated environmental laws.

But Lula’s government also promoted dams and other infrastructure projects in the Amazon that resulted in very high adverse environmental and social impact.

President Lula has pledged a radical shift from the disastrous anti-environment Bolsonaro policies. Positive early signs were the reappointment of Marina Silva as his environment minister and the creation of an Indigenous Peoples Ministry, headed by Indigenous leader Sônia Guajajara.

To dramatically reduce deforestation and fires, the Lula administration should follow through on its promise to strengthen the capacity of the agencies protecting the environment and Indigenous rights, and support the committed public servants who have been sidelined and harassed for four years for trying to do their job. It should reject bills being examined in Congress that could accelerate deforestation and institute safeguards and ongoing monitoring of the supply chain of gold, cattle, and agricultural products to ensure they are not linked to deforestation.

Government agencies, including INCRA, federal and state police, prosecutors, and state governors need to work together to fight illegal land-grabbing, dismantle criminal networks in the Amazon, and ensure accountability for both environmental crimes and violence against forest defenders.

During his speech to Congress as the new president on January 1, Lula pledged efforts to reduce deforestation to zero and to combat poverty and inequality. Those two objectives go hand in hand in the Amazon.

The key role that the rainforest plays in maintaining biodiversity and curbing climate change is well known around the world, given its massive capacity to capture or, if destroyed, release carbon dioxide, the main gas that causes global warming.

Less known is that those seeking sustainable use of the forest like the small-scale farmers of Terra Nossa, along with Indigenous peoples across the vastness of the rainforest, are at the forefront of the fight to preserve the planet.

The Brazilian government, the international community, and all of us should stand with them.