Credit Border Forensics

On the day we analyzed the drone’s flight path, we can see the first clear deviation from its usual pattern at 05:20 GMT when the drone takes a sharp turn to fly west and then moves in a loop over the same location. Our analysis indicates this was likely because the drone spotted a small wooden fishing boat carrying approximately 20 men. The Libyan Coast Guard later intercepted the boat in an operation Sea-Watch witnessed.

At the time of this first probable sighting, the SW3 was busy with a rescue operation 30 nautical miles south of the location where the drone made its loop, after receiving an alert from Alarm Phone. After taking on board the 40 passengers, some of whom had severe fuel burns and symptoms of fuel exposure according to Sea-Watch, the SW3 made its way north.

At 07:05 GMT, the drone deviated again to take a sharp north-east turn back toward where it probably first sighted the small wooden boat, performing another loop at 08:00 GMT at a location consistent with where that boat would have been if it was continuing its northerly direction, as is probable.

Unaware of the presence of the small wooden fishing boat, the SW3 continued heading north to disembark its rescued passengers in Sicily. At 12:28 GMT, in international waters, it came in sight of Libyan Coast Guard patrol boat 648—the Ras Jadir, one of four patrol boats Italy returned to Libya in 2017 after refurbishing them—intercepting a boat with about 20 people on board, the SW3 crew said.

Footage shot from the Seabird plane shows the Ras Jadir chasing the small wooden boat as it motors away.

Ultimately, the Libyan Coast Guard launched a RHIB, a lightweight and fast inflatable boat, to capture the boat.

No one was given a lifejacket, and everyone was taken on board the Ras Jadir.

David Lohmüller and Adrian Pourviseh/Sea-Watch

An official EU document indicates that the Ras Jadir returned to the Tripoli Naval Base at 23:34 GMT with 85 people, having intercepted four boats carrying migrants. But none of the locations reported in the document appear to match where the wooden boat was intercepted.

Crucially, none of the nongovernmental rescue boats operating in the area that day received any alerts from Frontex or coastal authorities about the wooden boat. The tracks of oil tankers Superba and Inviken and the supply ship Belize show they were in the vicinity but none of them appear to have changed course, indicating they had not received any instructions to respond to a distress situation, which they would have been obliged to do under the law of the sea.

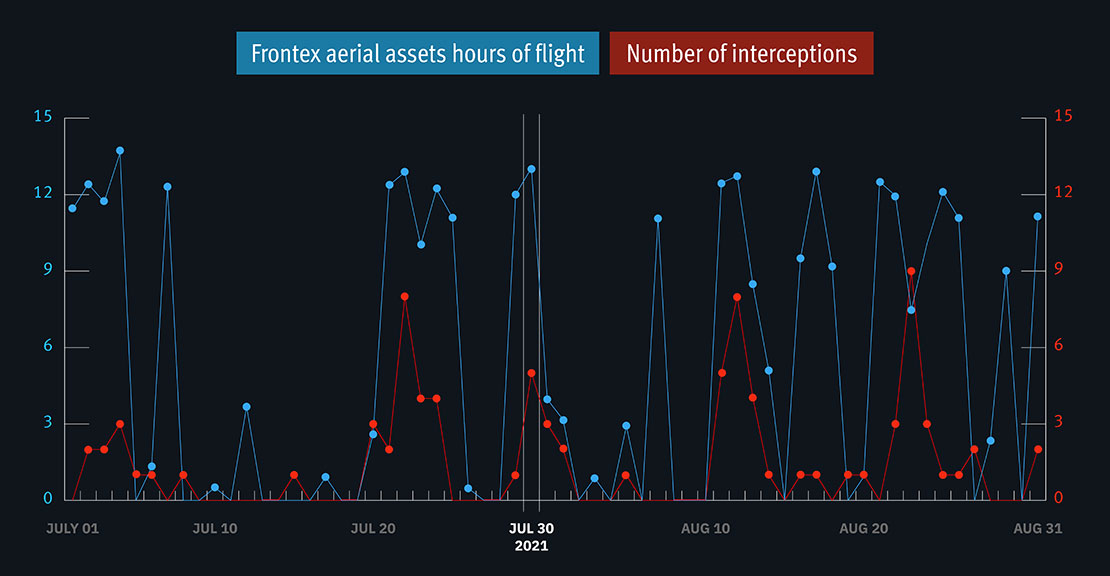

Frontex did not send out any mayday alerts that day or communicate in any way with nongovernmental rescue ships, in keeping with its stated policy. The agency says it “immediately alerts” national rescue centers in Italy, Malta, Libya, and Tunisia when they spot a “boat in distress” but only issues a mayday alert if there is an “emergency, where lives are at stake.” Between January 2020 and April 2022, Frontex says it issued 21 mayday alerts in the central Mediterranean, a tiny fraction of the boats sighted by its aerial surveillance. In 2021 alone, Frontex says there were 433 detections by aerial surveillance in the central Mediterranean involving 22,696 people.

Limiting communication about boats in distress to national rescue center is a deliberately narrow interpretation of when a mayday alert is warranted. It serves as a justification to alert Libyan authorities, even though the EU knows they are systematically returning people to abuse, and as an excuse not to alert nearby vessels, including nongovernmental ships, which would seek to take passengers to safe European ports.

The interaction between Ras Jadir and the wooden boat was in international waters, where Libyan authorities have no immigration enforcement authority, and within Malta’s search-and-rescue area. The failure of Frontex and member states to alert all vessels in the area, the way the Libyan Coast Guard patrol boat conducted the operation, and the fact that the wooden boat motored away all point to an interception whose sole purpose was to prevent those on board from reaching EU territory, and not a rescue.

According to data from a Frontex database obtained by the nongovernmental organization Frag den Staat, Frontex aircraft detected five boats on July 30, 2021. Libyan forces intercepted all of them and returned all those on board to Libya. A European Union External Action Service (EEAS) classified document that we reviewed also lists five interceptions that day, and although details do not match neatly, there is significant overlap.

One case appears across all sources—a rubber dinghy with approximately 120 people on board. Around 06:30 GMT, Alarm Phone had sent out an alert to the Italian and Maltese maritime rescue coordination centers, as well as to nongovernmental rescue groups, with the number for the satellite phone on the boat. In subsequent phone calls, it became clear the people on board had shut off the engine to conserve fuel and the boat was drifting near an offshore oil platform, 90 kilometers (55 miles) from the Libyan coast.

At 09:44 GMT, a man on the dinghy begged Alarm Phone for help, saying the Libyan Coast Guard had called them to ask for their position. It is possible the Italian and/or Maltese authorities gave the Libyans the satellite phone number—we can’t be sure because the Italian Coast Guard denied our request for information about their operations and communications that day, and the Armed Forces of Malta did not answer. The people on board put their remaining fuel in the engine and started moving again.

At 12:03 GMT the drone made a loop in a position consistent with where the boat would have been as it navigated north, and at 14:15 GMT, the Seabird, the Sea-Watch plane spotted an empty, deflated rubber boat in the area. Information we reviewed indicates the Libyan patrol boat Zuwara conducted an operation in that area involving a boat with 120 people.

The Libyan Coast Guard posted on Facebook about the operation, and Migrant Rescue Watch, a pro-Libyan Coast Guard Twitter account that reports on interceptions and disembarkations, tweeted photos of 121 people , including 10 women and 9 children, from the Zuwara patrol boat disembarking at Tripoli Naval Base. This matches the international Organization for Migration database record. Migrant Rescue Watch said that everyone was taken to a detention center.

Part of a group of 121 people intercepted by the patrol boat Zuwara on July 30, 2021. Exact location at time of photo unclear. Taken from the @rgowans Twitter account.

We spoke with four men, including Abu Laila, who said that Libyan forces intercepted them that day, but none of them were on the rubber dinghy intercepted by the Zuwara or the other two boats we documented. The details they provided suggest they were on four additional boats that are not captured by any official interception logs. It is possible that these sources do not include operations by the General Administration for Coastal Security (GACS), under the Interior Ministry, and the Stability Support Apparatus under the Libyan Prime Minister’s office. We were unable to locate any survivors whose accounts placed them without a doubt on the wooden boat intercepted by the Ras Jadir or the rubber dinghy intercepted by the Zuwara.

The extreme distress Alarm Phone heard on the other end of the call with someone on the rubber dinghy echoes the panic of people on these journeys when they understand Libyan forces are approaching.

Tesfay, a 21-year-old man from Eritrea, was on a two-deck wooden boat—not Abu Laila’s—that day, with about 90 people on board, mostly Eritreans, Ethiopians, and Sudanese. He was on the lower deck, but others told him they saw a plane circling overhead at one point, after the sun was high in the sky. At some later point, a Libyan boat came. “People started to scream. I managed to get to the upper deck…I saw the Libyan ship approaching. People were desperate, three or four…tried to jump in the sea, but they were stopped,” he told us.

Dawit, 28, also from Eritrea, was on a rubber boat with his wife and their 7-year-old daughter. He said they saw an aircraft when the sun was high in the sky, and then later in the afternoon saw a ship approaching. “We didn’t know it was the Libyans until it close enough and we could see the flag. At that point we started to scream and cry. One tried to jump into the sea and we had to stop him. We fought off as much as we could to not be taken back, but we couldn’t do anything about it.”

In their distress, Tesfay and Dawit could not remember enough details about the boats for us to determine what branch intercepted their boats.

Libyan forces have a reputation for reckless and violent behavior at sea. All four men we spoke with said they or others were beaten once aboard the patrol boats that intercepted them. Robel said he was beaten so badly he lost consciousness: “They were hitting us … treating us like animals … they beat me with the rifle butts and also stomped on me with their shoes. They hit me every time I tried to stand up, they hit me on the side of my head.”

All four accounts present a pattern: the distant vision or sound of an aircraft in the sky, the subsequent arrival of Libyan forces by sea, and their return to detention and unspeakable abuse.

Because it can fly closer to the Libyan coast for a longer time, the drone is likely to have played a prominent role, but we need full transparency from Frontex to be certain about its role in these interceptions. All the interceptions logged in official documents for July 30, 2021, took place within the drone’s operational area and its tracks reveal a geometry of loops, U-turns, perfect circles, and sharp corners, all testifying to potential sightings.

The precise geographical coordinates for the five interceptions reported in the classified EEAS document seem to match at least three of these peculiar patterns. But many more exist, suggesting the drone might have been responsible for even more sightings and interceptions that day. What the evidence strongly suggests is that before landing back in Luqa airport just before 18:20 GMT, more than 14 hours after take-off, it played a key role in facilitating the interception of potentially hundreds of people.