Abuse of Antipsychotics

in Nursing Homes

The Human Tragedy

Lenora Cline, 88, in her bed at a nursing home in Whittier, California. Her daughter, Laurel Cline, standing by the window, visits Lenora twice a day. Whittier, California, August 1, 2017. All photographs: © 2017 Ed Kashi for Human Rights Watch

Imagine your mom is in a nursing home and is suddenly drowsy all the time. At first you think her dementia has gotten worse. But then you realize that nursing home staff have put her on a powerful new medication—an antipsychotic drug—without discussing it with you or her. You find out that the Food and Drug Administration has warned that these medications almost double the risk of death in people like your mom. When you confront the nursing home staff, they tell you that your mother exhibited “difficult behavior” and that, if you want her taken off the medication, they may not be able to meet her needs—and may have to discharge her. Although using medications as chemical restraints is illegal, this happens to older people in nursing homes across America every day.

Every week, more than 179,000 people in nursing homes in the United States are given antipsychotic drugs even though they have not been diagnosed with any condition for which their use is approved. Often, facilities administer the drugs without making any effort to seek informed consent. Many nursing homes use these drugs not to treat a specific medical condition—such as psychosis or a neurological disorder—but because of their sedative effect. Antipsychotic drugs make nursing home residents easier to control by pacifying and sedating them.

A large proportion of people in nursing homes in the US have dementia, a brain disease that profoundly affects memory, communication, and other cognitive functions. In nursing homes without adequate staff numbers or without nursing staff adequately trained in dementia care, the facility may turn to antipsychotic drugs to sedate people who have difficulty communicating their needs and who act in a “disruptive” way from the facility’s perspective. The underlying cause of a person’s distress is often never addressed.

How Prevalent is Antipsychotic Drug Use in Nursing Homes in Your County?

In , of nursing home residents on average are on antipsychotic drugs.

staffing hours on average are spent per nursing home resident per day.

deficiency citations related to APD’s per 1,000 residents were reported between January 1, 2014 - June 30, 2017

The county has nursing homes, and nursing home residents.

Such use of antipsychotics and other psychoactive drugs—either for medically unnecessary purposes or as a “chemical restraint”—violates human rights norms and federal regulations. Not only is it unethical to give people drugs that they don’t need or don’t want, but also these medicines put people’s lives at risk: The US Food and Drug Administration requires manufacturers to place the strongest possible warning against the drugs’ use in older people with dementia because they significantly increase the risk of death.

The excessive administration of antipsychotic drugs also has profound social consequences. On our visits to more than 100 nursing facilities across six states, residents and their families told us about sedation, cognitive decline, fear, and frustration at not being able to communicate. Nursing home residents told us that the medicines made them profoundly disoriented and unable to function normally. Family members expressed shock at the apparent sudden cognitive decline of a loved one—only to discover later that it was the result of medications whose use they had never been informed of.

Here are the stories of three of them.

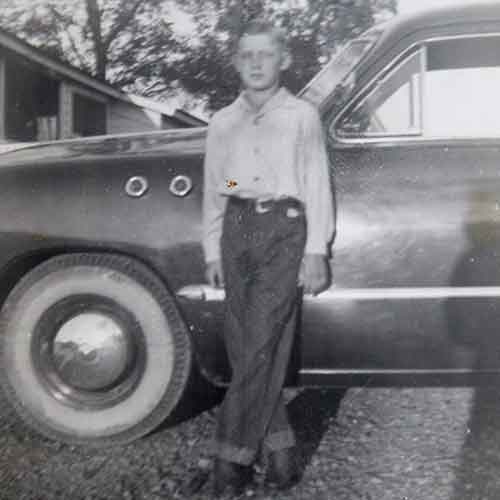

ALLEN WAGNER

Overland Park, KS

Allen Wagner, 79, having his hair cut by his wife, Charlene, in his room at a nursing home in Overland Park, Kansas, July 27, 2017.

Allen Wagner, 79, was diagnosed with dementia in 2009, and has been in and out of nursing homes and geriatric psychiatry hospitals ever since. Charlene, Allen’s wife, visits every day both to spend time with him and to make sure he’s getting the care that he deserves. Having witnessed serious neglect and abuse in several of the facilities he’s lived in, she knows she must be his greatest advocate. “In one nursing home, [Allen] was totally drugged until you couldn’t even talk to him,” Charlene told Human Rights Watch. He has been prescribed antipsychotics at every nursing home, sometimes without his or Charlene’s consent. “At one time, they had him on two different antipsychotic drugs where he was totally incapacitated,” Charlene remembers.

Before retiring in 1999, Allen was a hard worker. He grew up working the fields on his family’s farm and went on to work for the Santa Fe Railroad, where he remained for 31 years, eventually becoming a conductor for a train line from Kansas City to Arkansas City, Kansas. In the early days of their relationship, Charlene and Allen would go on walks along the train tracks, looking for old railroad spikes. Once they were married, they took trips out to the lake to camp and spend the weekend fishing.

“Allen was always … very loving, very fun,” Charlene says, “All of the women were crazy about him because he had these blue eyes that took your breath away.” It’s been hard for Charlene to watch her husband “deteriorate in front of [her] eyes” due to the effects of dementia. Harder still is not knowing how much of his cognitive decline is due to the disease rather than the antipsychotics he’s on.

Charlene wishes that she could bring Allen home, but she can’t afford to hire the help that would be needed to safely care for him. Allen is still on antipsychotics, but Charlene tries to make sure that his dosage isn’t increased. “Every time summer comes around, I miss going to the lake with Allen, spending time together out there,” Charlene told Human Rights Watch, “That was a lot of fun, enjoyment, and now it’s all memories.”

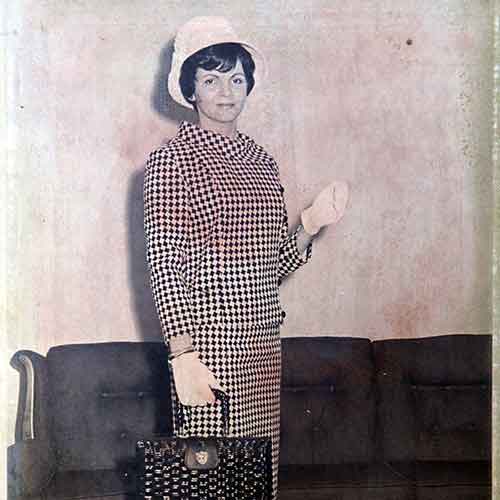

LENORA CLINE

Whittier, CA

Lenora Cline, 88, in her bed at a nursing home in Whittier, California. Her daughter, Laurel Cline, visits Lenora twice a day. Whittier, California, August 1, 2017.

Lenora Cline, an 88-year-old woman, has been living in a nursing home in Whittier, California for three years. After her dementia diagnosis 10 years ago, she initially lived with her daughter Laurel. But when she fell and broke her hip, Laurel felt she couldn’t safely take care of her mother anymore and got her into a nursing home.

Lenora was born in 1929 just outside of Montreal, Canada, and was one of seven children. Being one of the older children, she felt a duty to provide for her family, so she dropped out of high school to work. Over the years, she worked as an international oversees telephone operator, was a realtor, worked at a bank, and worked with people living with AIDS when the disease first emerged. She had a kind heart and a sharp sense of humor, recalls her daughter. “She would make so many people laugh… that’s what I remember most is her good humor.”

Laurel is the only family member involved in Lenora’s life and, like Charlene, has learned that she must be a fierce advocate for her. As soon as her mother entered the nursing facility she started worrying about the quality of care that she was receiving. She would visit her mother, leave for a few hours, and then return to find her in the exact same position, not having been turned at all. “One time I went in, and she was sopping wet, all the way through the mattress and everything was soaked,” Laurel said.

Lenora would often scream to get the attention of the staff. Laurel explained: “I told them that she’s in pain, she’s hurting, she’s hungry, there’s something wrong with her, that’s why she screams.” But Laurel says that instead of investigating what was making Lenora uncomfortable, she was put on Risperdal and Seroquel, antipsychotic medications, and later, on Ativan, an antianxiety medication that, like antipsychotics, can have a sedative effect. The medications made Lenora lethargic and less expressive at times, and more uncomfortable and vocal at others. Her health declined and the underlying problems—such as urinary tract infections, a pulmonary embolism, and other illnesses that hospitals identified, according to Laurel—were not resolved by hiding them with medications. After advocating for her mother, the facility agreed to take Lenora off the medications.

Laurel visits Lenora twice a day to help care for her. While she told Human Rights Watch that she worries about her mother constantly, she is glad she can be at the nursing facility so often to help care for her mother, since she knows the facility is understaffed. While she recognizes the challenging position staff are put in, she also worries about the other residents who don’t have relatives or friends to supplement their care.

LOIS BENKULA

Topeka, KS

Lois Benkula, 75, in her room at the nursing home where she currently lives, with her granddaughter, Sarah Benkula (center), and her daughter, Karla Benkula (right), 55. Karla feels much more relaxed about the care her mother is getting at this current facility. Topeka, Kansas, July 28, 2017.

Lois Benkula, 75, first entered a nursing home in Kansas in 2014 and was diagnosed with dementia later that year. Soon after her mother moved into a nursing facility, Karla, Lois’s daughter, began noticing that her hair was often greasy and that she didn’t look bathed. She worried in between visits and tried to see her mother as much as possible. However, the only nursing home that would accept Lois at the time was several hours driving from Karla’s home. According to Karla, the facility refused to give her proper notice of when staff met to discuss Lois’s care and refused to let Karla call in by phone.

As Karla was working to get Lois into another nursing home, the facility sent her to a geriatric psychiatry unit at a hospital in another town to be “re-evaluated for her medicines.” Karla said she was told that her mother was “acting out.” At the hospital, Karla explained, her mother was diagnosed with bipolar disorder—a condition that is usually diagnosed in late adolescence or early adulthood—and prescribed antipsychotics. Once she was on the antipsychotics, Karla said: “She wouldn’t talk. She wouldn’t laugh. She wouldn’t cry. She wouldn’t do anything. She would just sit and stare like she wasn’t even there.”

This was a dramatic change from the woman who raised her: “I’ve never seen [my mother] quiet. I’ve never seen her not have an opinion or not care.” Lois was a single mom who raised Karla while working as a secretary at an advertising firm during the week and cleaning its offices on the weekends. “It was me and her. Nobody was going to get us down,” Karla remembered.

Karla eventually succeeded in moving Lois into another facility, where she feels much more relaxed about her care. “She’s off the [antipsychotics]. She’s back. She’s healthy. She looks healthy. She laughs. She smiles,” Lois told Human Rights Watch. “I got my mom back as much as I can have her back.”

***

It is easy to pin blame for this practice on staff of nursing homes. But we frequently observed front-line staff doing everything they could for nursing home residents. Staff are too often put in impossible situations. When there are not enough nurse aides on a hallway full of people with urgent and complex needs, when the law does not require a doctor on the premises or a registered nurse outside business hours, the quality of care may be dangerously low through no fault of the aides on the premises. Data analysis from 2017 shows that almost a thousand nursing homes in the US are staffed at less than two thirds the minimum recommended level for adequate care. As Ashley Plummer, a nurse at a facility in Kansas told us, “the system is built to take care of a lot of people with not a lot of people.”

Ashley Plummer has worked in nursing facilities for over a decade. She has frequently seen antipsychotic drugs used to control residents.

Government data suggest that the use of antipsychotic drugs in nursing homes has gone down gradually in recent years, from roughly 1 in 4 to 1 in 6 residents receiving them without a diagnosis for which these medications are approved. But the absolute numbers remain extremely high, and progress in reducing inappropriate use has been uneven across facilities and states. In dozens of counties across the United States, more than 1 in 3 nursing home residents are still given these drugs without an appropriate diagnosis.

With such vast numbers of nursing facility residents still getting antipsychotic drugs that many do not need, do not want, and that put their lives and quality of life at risk, federal and state governments need to do more to ensure that the rights of residents are adequately protected. Institutions entrusted to provide care—and paid billions of public and private dollars to do so— cannot justify compounding the vulnerabilities, challenges, and loss that people often experience with dementia and institutionalization.