III. Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers

The Maoists’ policy of recruiting children for fighting or supporting combat is one of the most disturbing aspects of Nepal’s decade-long civil war. The concept of "recruitment" covers any means (formal or de facto) by which a person becomes a member of the armed forces or of an armed group, so it includes conscription (compulsory/obligatory military service), forced recruitment, and voluntary enlistment.19

The Maoists have used a variety of techniques for recruiting children: kidnapping of individual children; abduction of large groups of children, often from schools or at mass rallies that they are forced to attend; and use of propaganda campaigns to attract children as “volunteers.”

At the height of the civil war, in areas firmly under their control—particularly in the insurgency’s heartland in Nepal’s west and far west—the Maoists operated a “one family, one child” program whereby each family had to provide a recruit or face severe punishment. This campaign operated at a particularly high capacity in 2004 and 2005, as the civil war was escalating. Media reports, citing high-level Maoist leaders, suggested that it was called the “Special People’s Military Campaign” and involved training secondary and higher secondary students from many villages in “secret camps.” Citing the same source, the paper suggested that “15,000 recruits have completed their basic training there.” According to the account, the “model districts” for the campaign were far-western Jumla and Jajarkot.20 Over half of the children interviewed by HRW were from these districts. Our research strongly suggested that systematic abduction of children, or forced recruitment, also occurred in other areas where the Maoists could operate unfettered.

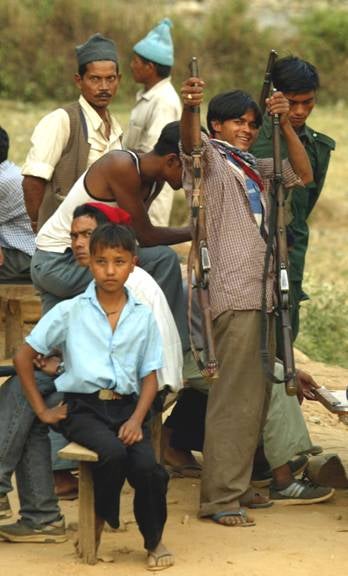

The Maoists conducted a systematic campaign of recruiting child soldiers. This campaign operated at a particularly high capacity in 2004 and 2005 in Nepal’s west and far west, the insurgency’s heartland. © 2004 AP Images

Human Rights Watch’s interviews supported investigations by credible Nepali groups such as Children as Zones of Peace and Advocacy Forum that indicated that most of the affected children are initially recruited by and for local Maoist militias, not the People’s Liberation Army (PLA, the armed wing of the CPN (M)). Militia units are expected to, and do, provide crucial military and logistical support to the PLA during combat operations, for instance by carrying supplies, providing frontline medical care, transporting the dead and injured away from battle, and, most directly, engaging in offensive or defensive military maneuvers. While local militias are not as well trained and well armed as the PLA, nonetheless both empirical evidence and statements by the Maoist leadership indicates that the CPN (M) closely monitors and controls the activity of local militias and exercises an effective chain of command when required.

We also interviewed some children who told us that they served with the PLA,

Most children were recruited by and for local Maoist militias. Militia units provided crucial military and logistical support to the Maoists’ armed wing, the People’s Liberation Army. © 2004 AP Images

confirming accounts by Nepali NGOs and international monitors about the PLA’s use of children. While the PLA and local militias may differ in their degree of professionalism and military training, both groups have taken part in major military operations, and both have been subject to attacks by Nepali security forces. Maoist military strategy has relied on overwhelming government forces by superior numbers.

The Maoists’ denials

Despite the evidence gathered from hundreds of children in Maoist ranks, the CPN (M) has consistently denied that it recruits or uses children for military activity. The party’s publicly stated policy for the past five years has been that it does not allow anyone younger than age 18 to join either the People’s Liberation Army or the “people’s militias.”

On November 18, 2006—just three days before the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed—Maoist leader Prachanda told Human Rights Watch, “We have never taken the policy to recruit children into our army. But in our military, they feed some children whose parents were martyred. We had some cases where we found that some cadres were children. We have returned them to their parents and helped them to go get an education.” When pressed about reports of ongoing recruitment, Prachanda said, “There has been a tremendous exaggeration on this issue by the palace and vested interests.” 21

The most detailed articulation of the Maoists’ official position came in February 2006, when it seemed as if the civil war was about to expand significantly. Prachanda was asked during an interview with the BBC about the Maoists’ practice of recruiting children.

First, he denied that the party recruited children: “In our party's central policy,” he told interviewer Charles Haviland, “we do not have a policy of recruiting children.”22

Prachanda went on to elaborate that the party was not recruiting children for military duty, but rather was taking care of needy children:

We do not even train children below 16 years old as militia.… But the situation does not match the account that the ruling classes and the feudals have propagated. Children whose parents have been killed in the war—taking care of them is the responsibility of the party. That's why we are compelled to take care of, educate and provide work for hundreds of children, even those who are 12 to 15 years old. This is a compulsion born out of the war. This compulsion has been falsely portrayed by the feudal elements as forced recruitment of children.23

The interviewer persisted by pointing out that the presence of children under age 16 in Maoist ranks was well known. Prachanda backed away from his earlier, blanket denial of the presence of children—particularly children younger than 16—among Maoist troops: “In village militias it might be true but in the People's Liberation Army that's not the situation,” he said.24 He was distinguishing between the professional military of the People’s Liberation Army and the less formal Maoist militias, which he implied might be less careful in applying the CPN (M)’s ban on recruiting children. In short, the Maoists denied that they had a policy of recruiting or using children for military purposes, and explained away the ubiquitous presence of children under age 18 by claiming that in fact such children were orphans being cared for by the CPN (M). At most, Prachanda implied, the presence of children among Maoist troops should be blamed on the lax discipline of village militias, not official party policy.

Prachanda’s November 2006 statement was consistent with the party’s official line since 2002.25 The ceasefire has neither changed the Maoist’s official line nor their justification for deviating from it. Nepali human rights investigators told Human Rights Watch that Maoist leaders, even at the local level, reject any requests or offers for assisting underage troops by simply denying that any children serve with them. And like Prachanda, when faced with the evidence, lower-level Maoist leaders claim that the children are all orphans in the care of the Maoists, or are volunteers. “We cannot stop the children who are impressed with our ideology and interested in our party activities,” a Maoist worker told journalists in September. “They have also their own rights and freedom to make their choices.”26

Other local Maoist leaders justify ongoing recruitment by claiming to be unable to control their forces. For instance, in September 2006 a local Maoist leader from Kohalpur, in Banke district, told the press, “We are very sensitive about human rights and it is against our policy to involve children in any sort of political activity. We will take action against the cadres who have been involved in abductions or forceful participation of children in any of our political programs.”27 In an interview with The Nepali Times, Narendra Batha Magar, a Maoist militia member, explained why his group was still recruiting and forcing children to join the movement. “No one will listen to us if we give up arms right away,” he said, adding, “there may be some violations of the code of conduct but that is because we haven’t had a chance to talk to our cadre.”28

“Voluntary” enlistment

Not all—not even most—of the children in Maoist ranks are forcibly recruited. Before the ceasefire many children joined Maoist cadres due to ideological training (see below), others because the Maoists offered them a way out of unemployment and poverty. Troublingly, after the ceasefire, the Maoists have attracted children into the ranks by promising them immediate financial assistance or jobs once Maoist forces and the Nepali Army are merged, pursuant to the peace agreement. Nepali human rights NGOs have accused the Maoists of enticing children to join by telling them that those who were in the PLA at the time of cantonment would receive pay of 7,000 to 10,000 rupees [US$100-US$141] per month.

Many lower caste Nepalis, particularly Dalits, joined to escape the rigid hierarchy of caste discrimination. As put in a report by the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice at New York University School of Law,

Maoists have recruited heavily among Dalits and women to fill the lower ranks of their army. Dalit men and women, who endure extreme marginalization under the caste system, may experience a feeling of unprecedented authority, control, and empowerment when armed with a weapon.29

Rural Nepali girls are drawn to the CPN (M) because it promises them freedom from a life of servility. “The Maoists have capitalized on the widespread and legitimate discontent among rural women,” a seminal study of the subject noted. “Many rural women have either been abused themselves [by government forces] or have seen their family members, relatives or neighbours victimized by the security forces.”30

For example, 17-year-old Kalawoti told Human Rights Watch that the Maoists initially convinced her to join their campaign by explaining that as a woman she would never be able to achieve anything even if she continues her studies. She said,

The Maoists took me from home for a campaign. I had finished sixth grade by then. They were saying that young girls like me should join them because in Nepal there was no point in studying, since in any case I would not be able to get a job.31

She added that when she came back home after participating in the “campaign,” she found out that two people from her area who had participated in the same campaign had been killed by the security forces , and then she decided she “wanted to stay with the Maoists.”32 We heard similar tales from other girls we interviewed.

With poverty in Nepal seriously exacerbated by years of conflict, many Nepali children faced a bleak future and found the prospect of fighting for the Maoists preferable. The combination of economic incentive and Maoist ideology is particularly effective as a recruiting tool in those areas where Maoists have sufficient control over the territory to engage in repeated recruiting programs.

Ram, a 16-year-old boy from Panchthar district in the far east of Nepal, described the circumstances that led to his joining the Maoists when he was about 11 years old:

I went to school up to class 6. I liked school. I used to stay with my grandfather; I had a stepmother and my father was often away. My grandmother didn’t have enough money to buy material for school, so I stopped going. After I quit school, sometimes I stayed at home; other times I worked at hotels, washing dishes.

After two months, I joined the Maoists. There were lots of Maoist programs in my village. Two or three Maoists came to my house. My father was not there, so they took me to go for a cultural program. Initially, I refused, but they insisted, so I went. They did not threaten me. I felt my parents did not give me enough attention.33

Another 17-year-old boy, Hem, described how he joined the Maoists after he failed to find sufficient employment in India:

My village is Maoist, so I joined on my own. I had already left school. The reason I left school was I went to India in Ashoj 2059 [September 2002]. I went to Gauregang, Delhi, worked in a tea shop. I was 15 years old. After one year I came to Nepal. So many friends were joining [the Maoists] so I joined too.34

Recruitment campaigns

Bikram, a 16-year-old boy from Jumla district, described the cumulative impact of years of Maoist indoctrination in convincing him, and dozens more of his schoolmates, to join the Maoist cause voluntarily and against their parents’ wishes:

I was in class 6 [age 13] when they started [to] come to my class. I was 15 when I decided to join. I was highly influenced by the political ideology. I didn’t tell my parents. I ran away from home. They wouldn’t allow it. They said I have to study and work. All but five students from my class joined. All were influenced by the Maoists ideology and the cultural activities. No one was forced to join.

There was a competition between schools to see how many would join from different districts. My school got first place. [In addition to 45 students from my class], there were 30 from another class; and 10 from another class. Eighty-five altogether. There were no prizes, but the students who headed organizations had their posts upgraded.35

The Maoists have relied on a large-scale, systematic program to recruit children through propaganda programs in schools or at mass gatherings. The Maoists used songs, dance, and theatrical performances designed to appeal to children; often children carry out these performances in order to attract other children. This program has continued even after the ceasefire.

The Maoists recruited many children at involuntary mass gatherings where they were subjected to propaganda programs. © 2005 Ami Vitale

We received reports of recruitment campaigns like this all across Nepal before the ceasefire, casting doubt on the Maoists’ claim that recruitment of children was the result of undisciplined or intransigent local militias. We interviewed children who had been recruited by Maoists at their school when they were as young as 10 years old, though most of the former child soldiers interviewed by Human Rights Watch had been around 14 years old when they had been recruited.

As frequently reported, these campaigns have included compelling children to attend involuntary educational sessions during which children are taught Maoist doctrines and are told about the advantages of joining Maoist cadres. In 2004 and 2005, when the Maoists’ recruitment drive was particularly active, there were numerous reports of Maoists recruiting at schools throughout the area under their control.Frequently, Maoists brandished the threat of violence to compel an entire school’s population to listen to the Maoists’ propaganda. Beginning in 2003, the Maoists expanded their recruitment campaign beyond schools to include mass propaganda rallies. Attendance at these rallies was compulsory, and thousands of Nepalis, and in particular children, were forced to go.

According to Advocacy Forum, recruitment initially accelerated immediately after the ceasefire, and then has continued at a slower—though steady—pace even after the peace agreement. Recruitment often occurs under the public cover of “educational campaigns” or “schooling.” NGOs monitoring the recruitment and use of child soldiers have received numerous reports of Maoists continuing their practice of forcibly commandeering schools or school grounds for such sessions across the country.36 The OHCHR reported that “[c]hildren have been taken for short periods of time to attend mass political/student gatherings. In Kathmandu, on several occasions in August [2006], thousands of children were taken from schools to participate in day-long programmes organized by the ANNFSU—Revolutionary [All Nepal National Free Students Union–Revolutionary —the student wing of the CPN (M)].”37

The National Coalition for Children as Zones of Peace reported that in the 100 days after the ceasefire,

[d]uring the monitoring of various places of the Kathmandu Valley such as Koteshwor, Bhaktapur, Banepa, Boudha, Jorpati, Maharajgunj, Balkhu, Kirtipur, Kalanki, Thankot and Chapagaon, the activists of the CPN (Maoist) have been found involving children in their school uniforms in various programmes. Furthermore, the Maoists and other political parties are forcing children to attend different programmes in other districts, too. In the same way, the Maoists' student wing—All Nepal National Free Students Union–Revolutionary (ANNFSU–R)— closed nine schools of Salyan district and took students to Shiva Jana Higher Secondary School, Shitalpati for making them participate in the Student Day Programme, which was organized by them.38

In November 2006 an Advocacy Forum investigative team in midwestern Nepal reported:

Mass recruitment has been going on. Villagers told us that from each VDC [village development committee] a busload of people (new recruits) were taken to Surkhet. From them about 20-30 were children under 18. Another interesting fact that came up, and that was seen as a trend in all the districts were that the new recruits were either dropout children, children who had not gone to schools, or adults who had no work.39

The content of the CPN (M)’s current propaganda campaign after the ceasefire seems to be essentially identical to programs they conducted at the height of the civil war in 2004 and 2005.40 Birendra, a 16-year-old boy who had been 14 when he was recruited in Argakhanchi district, 250 kilometers west of Kathmandu, described the typical program of song and dance that he witnessed in 2004:

The Maoists did programs at my school. In three or four months, they would come two or three times. They would sing, dance, and give speeches. Usually there were six to nine Maoists; some were the same age as me, some were older. In the speeches, they said, ‘You have to fight for the people, for people’s education, and you have to come with us.’ It lasted about one hour. There were 35 students in my class; three (all boys) went. There were five or six from other classes that went also. One girl and the rest were boys.41

The Maoists’ propaganda campaign does not rely on art and ideology alone. In most instances, children face pressure to join the Maoists. Birendra continued by explaining how cultural activities led to the Maoists recruiting him along with several other classmates:

I went to school to the tenth grade. I stopped because the Maoists put pressure on me, I had to leave and join them. They asked me to go for cultural activities, so I went. Five or six [other students] joined first, then three of us.42

Bikram, who was 15 years old when he was recruited, described a similar program that netted the Maoists dozens of recruits after a more intensive propaganda campaign that included daily visits by Maoist cadres:

I went to school to class nine. In school, the Maoists used to have cultural programs, and recruit children as combatants. There were 50 students originally in my class, but all but five were recruited. The Maoists came to my school every day. The cultural programs included singing and dancing, then speeches. They formed organizations among the students to do cultural programs in far places, to collect donations among students, and disseminate information about the Maoists to other youth. In the speeches, they said, “We are fighting for the people of the country; we have to fight against corruption. We are going to form the New People’s government and we need support from all of you.” The Maoists who came were of different ages; some older and some young. The programs were mostly in school; once a month or once a week they were in a public space or open space.43

Bikram went on to describe how the fear of Maoist reprisals, coupled with their propaganda campaign, made him feel compelled to join up:

I was impressed by their speeches and very influenced by what they said about fighting for the people and fighting corruption. But I was also upset that they interrupted our schooling. They would force us to come. If you didn’t come, you will have to work for the Maoists or will be forbidden to go to school. I always went.44

Ramesh, a 15-year-old boy from Terahthum district, in the far east, described the campaign there in similar terms. Ramesh was in the fourth grade when he was recruited—just 10 years old. “I went to school till the fourth grade. I stopped when I joined the Maoists. The Maoists came to my school to do cultural program two or three times a month. There was singing, dancing and speeches. They said, ‘You have to fight for your country, you have to join us.’” 45

OHCHR said in a September 25, 2006 report, “Information clearly suggests that the CPN (M)’s cultural groups and militias have significant numbers of children who may at the same time also be used for military purposes as messengers or informants, and to attract other children into the CPN (M)-affiliated movements.”46 Several of the children we spoke with had recruited other children as part of their duties. For instance, Kalawoti told Human Rights Watch that she and other children “held campaigns, went to schools, and brought new students to join. We were also running programs in schools.”47

While many children join the Maoist forces “voluntarily” after such sessions, Advocacy Forum reported that at least in a few cases (Kaski and Baglung districts), the children were moved to camps in different places so they could not be traced by their parents.48 The sessions also help identify children who might be suitable for recruitment at a later date or through more forceful means (see, for example, the cases of Pradeep and Shyam, below).

19 See Sylvie-Stoyanka Junod, Article 4, No. 4557, in Claude Pilloud et al., Commentary on the Additional Protocols of 8 June 1977 to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 (Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross, 1987), p. 1380.

20 Jhalak Gaire, “Child soldiers,” The Nepali Times, February 27-March 6, 2004.

21 Human Rights Watch questioned Prachanda during a meeting organized by the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi on November 18, 2006.

22 Charles Haviland, “Prachanda Interview: Full Transcript,” BBC News Online, February 13, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4707482.stm (accessed October 2, 2006).

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 See, for instance, Alex Perry, “‘We Are Trying to Crush Feudal Autocracy’: Interview with the Maoist Leader,” Time Asia, April 15, 2005, http://www.time.com/time/asia/2005/nepal/ext_int_prachandar.html (accessed October 2, 2006). During that interview, Prachanda said, “We strictly do not allow those below the age of 18 to join. But one thing [that confuses] commentators is the thousands of orphans of our martyrs. Our party naturally undertakes the responsibility to feed, educate and train them so as to be good successors to their parents. We never use them in fighting, but we educate and discipline them as a children's organization.”

26 “NEPAL: Children still living in fear of Maoist rebels,” IRINnews, September 11, 2006, URL (accessed October 2, 2006).

27 Ibid.

28 “Rolpa’s Reality,” The Nepali Times, August 25-31, 2006.

29 Center for Human Rights and Global Justice at NYU School of Law, “The Missing Piece of the Puzzle: Caste Discrimination and the Conflict in Nepal,” 2005, http://www.nyuhr.org/nepalreport.htm (accessed October 16, 2005). The report went on to note, “Once drawn in, they are deployed on the frontlines of battle. While it is difficult to assess the number of Dalit deaths from the conflict, a disproportionate number of Dalits may be dying on the frontlines in clashes with security forces as very few assume positions of authority or decision-making in the insurgency.”

30 Mandira Sharma and Dinesh Prasain, “Gender Dimensions of the People’s War,” in Michael Hutt, ed., Himalayan People’s War (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004), p.164. The authors went on to point out that “the Maoists themselves have not as yet publicly produced an agenda setting out how they would seek to address gender issues more meaningfully in the immediate future—before the utopia of a classless society is achieved.”

31 Human Rights Watch interview with Kalawoti (age 17, from far western Nepal), Butwal, March 5, 2006.

32 Ibid.

33 Human Rights Watch interview with Ram (age 16, from Panchthar), Kathmandu, May 1, 2006.

34 Human Rights Watch interview with Hem (age 17, from Dadheldhuva), Butwal, March 5, 2006.

35 Human Rights Watch interview with Bikram (age 16, from Jumla), Kathmandu, May 1, 2006.

36 Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Advocacy Forum, January 19, 2007.

37 Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Nepal, “Human Rights Abuses by the CPN (M): Summary of Abuses,” September 25, 2006. Note that ANNFSU is also sometimes referred to as the All Nepal National Independent Student Union, or ANNISU.

38 National Coalition for Children as Zones of Peace, “Hundred Days of Democracy: Children Are Still Ignored.”

39 Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Advocacy Forum, November 24, 2006.

40 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Mandira Sharma, Kathmandu, August 28, 2006.

41 Human Rights Watch interview with Birendra (age 16, from Arghakanghan), Kathmandu, May 2, 2006.

42 Ibid.

43 Human Rights Watch interview with Bikram (age 16, from Jumla), Kathmandu, May 1, 2006.

44 Ibid.

45 Human Rights Watch interview with Ramesh (age 15, from Tehrathu), Kathmandu, May 2, 2006.

46 Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Nepal, “Human Rights Abuses by the CPN (M): Summary of Abuses,” September 25, 2006.

47 Human Rights Watch interview with Kalawoti (age 17, from far western Nepal), Butwal, March 5, 2006.

48 Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Advocacy Forum, August 30, 2006.