<<previous | index | next>>

II. Cuba’s Restrictions on Travel

Background

Past Travel Restrictions

More than one million people of Cuban “origin or descent” live in the United States. Over 700,000 of them were born in Cuba; many still have close relatives on the island.1

Over the past four decades, Cuban migration to the United States has come in waves, propelled by economic and political developments on the island and curtailed by the migration policies of Cuba (as well as the US policies discussed in the next section of this report). The first wave, which included some 200,000 Cuban emigrants, began shortly after the 1959 revolution and continued until the Castro government halted regular travel to the United States in 1962.2

The second wave began in 1965 when the Cuban government allowed some 5,000 people to leave in a boatlift from the port of Camarioca, and then continued for eight years in the form of an airlift, known as the “freedom flights,” which entailed twice-daily flights to Miami that brought another 200,000 Cubans to the United States. The Cuban government terminated the airlifts in 1973 and a virtual suspension on migration ensued for the rest of the decade.3

The next major exodus occurred in 1980 when the Cuban government, responding to growing pressure for emigration (and the occupation of the Peruvian embassy by some 10,000 people seeking to leave the country), allowed over 125,000 people to leave the island, including some convicted criminals and others deemed “unwanted” in Cuba, in what became known as the “Mariel Boatlift.” Then, in 1981, Cuba began granting permission for its citizens to visit the United States, but migration levels remained low, until pressure for massive emigration rose once again in the early 1990s. Another major exodus began in 1994 when the Cuban government announced that it would not detain anyone trying to leave the island. Some 30,000 people attempted to cross the Florida Straits, many of them on make-shift rafts. The resulting “rafter crisis” prompted the United States and Cuba to negotiate an agreement whereby the United States agreed to admit at least 20,000 Cubans a year and Cuba agreed to accept the return of unauthorized emigrants intercepted by the U.S. Coast Guard at sea.4

In addition to controlling emigration, the Cuban government has placed strict limitations on visits to the island by Cuban émigrés. For twenty years after the revolution, Cuba forbid them from returning (and confiscated their property on the island when they left). In 1978, the Cuban government began to allow return visits. But it imposed limits on who could visit throughout the 1980s. In 1994, the government further eased restrictions on visits by émigrés, allowing them to travel to Cuba without visas.5 But then in 1999, it began imposing a five-year ban on the return of any Cuban who left the country without permission.6

Current Travel Restrictions

The Cuban government currently forbids its citizens from leaving or returning to Cuba without first obtaining permission from the government.7 Unauthorized travel can result in criminal prosecution.8 Under Cuba’s criminal code, individuals who, “without completing legal formalities, leave or take actions in preparation for leaving the national territory” can face prison sentences of one to three years in prison.9 Similarly, an individual who “organizes, promotes, or incites” an illegal exit can be punished with two to five years of imprisonment, while someone who “provides material assistance, offers information, or in any way facilitates” an illegal exit, risks two to five years behind bars.10 (The Cuban Commission of Human Rights and National Reconciliation, a Havana-based nongovernmental organization, has documented nineteen cases of individuals who have been sentenced to serve time in prison for attempting to leave Cuba illegally in the past five years.11) Individuals who enter Cuba “without completing legal formalities or immigration requirements” risk one to three years of imprisonment.12

Cuba routinely denies exit visas to several categories of applicants, including health care professionals and young men who haven’t completed their mandatory military service. Cuba also frequently refuses to allow citizens engaged in authorized travel to bring their children with them overseas. In some cases, it denies visas to the relatives of people who have left the country without permission or refused to return at the end of an authorized trip. It further punishes these “deserters” by denying them permission to return to Cuba.

Human Rights Watch was unable to obtain information from the Cuban government regarding the denial of visa applications. (Cuban authorities failed to respond to repeated requests for interviews.) Consequently, it is difficult to establish precisely the full scope of this practice. But there is broad consensus among Cuban human rights advocates and doctors that it is in fact widespread.

This consensus is corroborated by the large number of Cubans who have informed the U.S. Interests Section in Havana that they have been denied permission to leave Cuba after obtaining visas to enter the United States.13 The Interests Section received reports of 1,762 individuals being denied exit permits between October 2003 and March 2005.14 U.S. officials believe that these reported cases represent only a fraction of the total number of individuals denied exit permits. 15

Illustrative Cases

Hilda Molina

Dr. Hilda Molina was once a leading figure in the development of Cuba’s state-run health care system. Hailed in the official press as a “great scientist,” photographed repeatedly with Fidel Castro, and elected to the national Congress, Dr. Molina, a neurologist, founded the International Center for Neurological Restoration (Centro Internacional de Restauración Neurológico, CIREN) in 1988 to coordinate Cuba’s neuroscientific work.16

Dr. Hilda Molina with her mother in Cuba.

She was told she could not travel because her brain was “property of the government.”

© 2005 Private

But when she sought permission to visit her son and grandchildren in Argentina, she was told she could not leave the island because her own brain was “the property of the government of Cuba.”17

Dr. Molina’s son, Roberto Quiñones, also a doctor, left Cuba with his Argentine wife to attend a medical training in Japan in May 1994. When the training ended in June, Dr. Quiñones decided to move to Argentina with his wife, where he has lived ever since.

Shortly after her son’s departure, Dr. Molina had a falling out with the Health Ministry and Communist Party, prompting her to resign from both CIREN and the national Congress. The break was caused, she says, by her unwillingness to succumb to pressures by the Health Ministry to accommodate more foreign patients at the expense of Cubans at CIREN. “They prostituted my work,” Dr. Molina told Human Rights Watch. “They turned my work into a center for earning foreign exchange.”18 It was also prompted by criticism she received within the Health Ministry for her decision, made with the agreement of all of CIREN’s directors, to use a $10,000 donation from a grateful Argentine patient to buy gifts of food and clothing for the institution’s four hundred workers. Officials at other health institutes reportedly complained to Fidel Castro that she was using capitalist incentives and corrupting the workers of CIREN.

Since her fall from grace, Dr. Molina and her son have been trying to obtain permission for her to visit him in Argentina. Their efforts intensified when her son’s first child was born in 1995, and again after the birth of a second child in 2000.

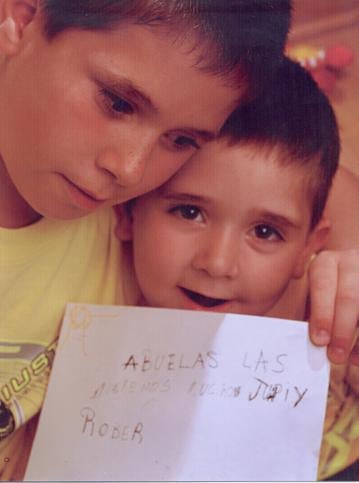

Dr. Molina’s grandchildren with a note to the grandmother they have never met.

© 2005 Private

“I began sending ceaseless letters to the Ministry of Public Health, the Attorney General’s Office, the Council of State, the Immigration Department, and finally, three years later, in 1997, they responded,” Dr. Molina told Human Rights Watch. “A military officer from the Immigration Department told me that I could not go because my brain was the property of this country.” Three years later, after Dr. Molina sent further letters to the government, the same officer again told her verbally that she could not leave “because it was an order that must be obeyed,” she said. Dr. Molina never received a response in writing.19

In December 2004, Argentine President Néstor Kirchner and Foreign Minister Rafael Bielsa pressed Havana to allow Dr. Molina to travel. President Kirchner sent Castro a personal letter asking that the Cuban leader grant Dr. Molina’s grandchildren, by that time three and nine years old, the opportunity to meet her.20 Castro replied by offering to allow Dr. Molina’s son, Dr. Roberto Quiñones, and his family to visit Havana instead. But Dr. Quiñones declined this offer, fearing what might happen upon their arrival. He himself had had difficulties leaving the country in 1994 and did not want to risk being subject to any form of retaliation.21

Since she resigned from CIREN, Dr. Molina has had no source of income other than the remittances sent by her son in Argentina. She suffers from a wrist injury which was not properly set in 2002, causing significant muscle atrophy and pain. In addition, she cares for her own eighty-six-year-old mother, who is ill and nearly blind. She and her son have continued to request that she be allowed to leave and return to Cuba without restriction.22

Teresa Márquez and Roberto Salazar

“Teresa Márquez” and “Roberto Salazar” were separated from their two sons for three years and five years, respectively, after they abandoned Cuba without permission and the government refused to let the children join them.23

Salazar, a musician, left Cuba in 1998 with a contract to perform in México. Once there, he decided to stay. Two years later, in 2000, Márquez obtained permission to travel as a tourist to visit him. She too stayed.

The couple immediately set about trying to obtain exit visas for their two sons, ages eight and nine, who remained in the custody of her parents in Cuba. In 2000, Salazar traveled to Cuba and, together with his mother-in-law, visited the migration offices in her hometown. The officials he met with called him a “deserter,” placed a mark in his passport showing that he had stayed outside the country without permission, and refused to grant permission for him to take his children out of the country.

Two years later, in September 2002, Márquez traveled to Cuba to see if she could do better. But she, too, was rebuffed and was obliged to return to Mexico without their children. Six months later, in March 2003, migration authorities told Márquez’s mother that the children could leave. Márquez returned to Cuba that month to retrieve the kids, but was again denied permission to bring them home with her. Finally, on April 26, the children were allowed to fly alone to Mexico to rejoin their parents.

Being separated from her children for three years was a “horrible” experience for the couple. “It changed my life completely,” Márquez told Human Rights Watch. “They tore out a piece of my life.”24

María Elena Morejón

It took nuclear scientist María Elena Morejón nearly two years to get her son out of Cuba after her husband, Israel Perú Castro, defected in Austria in 2000.25 Her case, in which she and her child were separated in retaliation for the actions of her husband, illustrates the collective nature of Cuba’s punitive travel restrictions.

Morejón traveled with her husband and infant son in the late 1990s to Austria, where the couple represented Cuba at the International Agency for Atomic Energy. When her husband decided to defect at the end of their period of authorized travel, Morejón left him and moved back to Cuba with the child. Once back in Cuba, she married a German and, in 2001, obtained German visas for her son and herself so that they could join her new husband in Germany. However, the Cuban government would not grant an exit visa to her son, then four years old, because of his father’s “desertion.”

In October 2001, Morejón sent a written request to the migration office of the October 10th municipality of Havana for permission for her son to leave. Receiving no reply, she visited the office in person and presented to an official there medical documents showing that her son’s health was delicate, and that he should be able to leave with his mother. The official assured her that her case would be treated as “exceptional,” and his papers would be processed in less than three months.26

In December, Morejón traveled to Germany without her son, after being advised by an acquaintance who worked in the Interior Ministry that she would be more likely to get her son out quickly if she left the country. Yet by April 2002, she still had received no word regarding her son’s travel permit. So she sent a relative to speak to the migration official, who reported that permission would soon be granted. The relative also visited the national migration office and received the same assurances.27

Convinced that her son would soon receive an exit visa, Morejón returned to Cuba to escort him to his new home. It was at this time that she learned that she and her son would be punished for her ex-husband’s defection. On April 25 she met with the migration official at the national office, who informed her that government policy held that relatives of “deserters” must wait five years before leaving the country. “‘The revolution has to defend itself,’” Morejón recalls the official saying, “‘and that’s why the family members of deserters will be retained in Cuba for no less than five years.’”28 At the same time, however, he assured her that the case would be reexamined and that he expected a positive result within two months. However, she would need to submit another letter with additional information, which she did on April 30.29

In June, Morejón returned to Cuba to press for a reply to her new request, but was told that the case had been transferred to the Interior Ministry. In a meeting on June 21, an officer at the Interior Ministry told her to return to Germany, and expect a positive answer by no later than August. After that, Morejón continued making phone calls to different government offices from Germany inquiring about the case. On November 23, the October 10th migration office summoned Morejón’s parents for a meeting, during which they were assured that the only thing missing from the file was a letter of invitation. With the letter in hand, Morejón’s relatives began making weekly visits to the migration office, where they were repeatedly told that the request just needed to be approved “at a higher level.”30

Maria Elena Morejón felt her son was being sentenced to “live like an orphan with live parents.”

© 2003 Private

Yet months passed without approval. On February 18, 2003, Morejón spoke on the phone with the national migration officer who had previously explained the government’s policy of denying exit permits to the relatives of “deserters.” His reaction was even more severe than before, she recalls. He said that her “only choice” was to return to Cuba and wait with her son until the government determined that its internal regulations, aimed at protecting the revolution, had been complied with. “‘We will try to make it less than five years,’” she recalls him saying, “‘but don’t call me any more because I have no more time to talk to you.’”31

On March 1, 2003, Morejón wrote the Cuban Ambassador to Germany, warning that she would publicize her case if her son was not allowed to leave soon. Not receiving any response, Morejón began a whirlwind of activities to draw international attention to her family’s plight. She contacted the Miami Herald, which published a story about their case. She contacted several foreign embassies in Germany and traveled to the Vatican to plead her case. She also traveled to Geneva to publicize her case among human rights advocates and officials attending the annual meeting of the U.N. Commission on Human Rights.

On June 26, 2003, her parents called her to tell her the exit visa had finally been approved and on July 16, mother and son were reunited in Germany.

The ordeal had taken an enormous toll on her and her family. Their efforts to get her son out of Cuba had cost an enormous amount of time and money. And they had endured two years of anguish fearing—as Morejón put it—that the Cuban government was “trying to sentence my son to live like an orphan with live parents.”32

Juan López Linares

Cuban physicist Juan López Linares traveled with his wife to Italy in 1997 to participate in a training course at the International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste. When the course ended, he sought and was denied permission from the Cuban consulate in Milan to continue studies outside of Cuba. The Cuban consular official warned him that, if he did not return to Cuba, he would be formally classified as a “deserter” and would be prohibited from entering Cuba for five years.33

Despite the warning, López Linares decided to continue his studies abroad, pursuing a doctoral degree in Brazil. His wife returned to Cuba in February 1999 and gave birth to their son two months later. The couple subsequently split up and she chose to remain in Cuba. López Linares began requesting permission to return to Cuba to meet his son in July 2000. His requests have been repeatedly denied.

The clearest explanation of the government’s refusal to allow López Linares to return to his homeland came in a letter that Cuba’s ambassador to Brazil, Jorge Lezcano Pérez, sent in August 2002 to a Brazilian senator who had intervened in the case. López Linares could not return to Cuba, the ambassador wrote, because he had “abandoned an official mission that he was carrying out in representation of a Cuban government agency in a third country.” Such restrictions were justified, according Lezcano, “to protect national security and dissuade the harmful phenomena of illegal emigration and the theft of brains.”34

The letter went on to accuse López Linares of involvement in “a politically motivated and slanderous campaign” against Cuba, as well as involvement with “extremist organizations…with an extensive history of aggression against the Republic of Cuba, including terrorist actions.” Lezcano offered no details to support these allegations, which López Linares categorically denies. López Linares subsequently wrote the ambassador, challenging him to prove the allegations and requesting copies of the rule or regulation that applied to his case.35 As of this writing, he has not received a response from Ambassador Lezcano.36

López Linares’s son turned six in April 2005. The two have never met.37

José Cohen

José Cohen, a former intelligence officer with the Interior Ministry, fled Cuba on a raft in August 1994. He has been trying to get his wife and three children out ever since. But the Cuban government has refused to grant them permission to leave the island.38

José Cohen has not seen his children in eleven years.

© 1998 Private

Before leaving Cuba, Cohen’s intelligence work required him to spend time with foreign investors and scientists, possibly giving rise to government suspicions that he had access to sensitive information. In a measure of the government’s anger over Cohen’s defection, his wife and parents were reportedly invited in April 1996 to view an in absentia trial in which Cohen was sentenced to death for desertion.39

Cohen reports that in addition to suffering an eleven-year separation from their father, his children have faced harassment and humiliation in school at the hands of teachers, who are generally Communist Party militants. According to Cohen, one teacher instructed his son in middle school to write a paragraph under the title “Fidel is my father.” When his son refused, the teacher reportedly said, “That’s because Bush is your father.” Other teachers have told his children that their father did not love them since he left them behind. Although his daughters have received excellent grades in high school, they have not been allowed to attend any university, apparently because of their father’s “desertion.”40

Denial of Exit Visas

Health Care Professionals

A large portion of the Cubans denied exit visas are doctors and other health care professionals. Of the cases reported to the U.S. Interests Section, roughly half fell into this category.41

The reason so many health care professionals are denied exit visas is the Public Health Ministry’s “Resolution 54”—or at least that is what many of them are told when their petitions are rejected. However no one we interviewed had ever seen the regulation—not even those who requested copies when it was cited to deny them exit visas. “It’s like a phantom law,” one doctor told Human Rights Watch. “No one has seen it in writing.”42

By most accounts, “Resolution 54” requires health care professionals applying for exit visas to wait three to five years before their application will be considered. Some doctors report that the rule specifies they spend these waiting years working in rural communities.

If the actual text of the regulation has been kept from the public, the rationale behind it has not. The restriction is part of a broader effort to prevent a “brain drain” of skilled professionals from Cuba.43 President Castro has accused the United States of actively luring large numbers of skilled professionals from Cuba, “thus depriving our country of medical doctors, engineers, architects and other university graduates who have been educated here, absolutely free of charge.”44 And he has vowed that Cuba would not tolerate an exodus of professionals, declaring that the country would not be exploited as “an incubator of brains,” and that “those [brains] it does incubate are primarily to serve our people and our brother countries in the world that suffer from plundering and poverty, not to fatten the pockets of the plunderers of the world.”45

Yet, as the case of Dr. Hilda Molina above illustrates, this restriction is applied to doctors who have already made significant contributions to Cuba’s health care system. And as Dr. Molina’s case also demonstrates, one result of the policy is the forced separation of families.

Dr. Edelma Almaguer Pomares, for example,was denied an exit visa in 2004 on professional grounds after winning a U.S. visa through the immigration lottery in June 2003. Earlier in 2004, her husband, who had a U.S. visa that was expiring, had traveled to the United States expecting that Dr. Almaguer and their daughter would soon be able to join him. Under the current regulation, Dr. Almaguer will not be allowed to leave Cuba for another three years.46

Similarly, Arturo Morejón won a visa to the United States in the lottery and left Cuba in October 2002. His wife, Dr. Rita María Aguilar, has been told that because she is a doctor, she could not leave for another five years.47 Dr. “Jorge Ramos” fled a medical mission in Venezuela in 2003. His wife and son have been unable to leave Cuba because she, too, is a doctor.48

“Roberto Gómez” felt compelled to leave Cuba in August 2001 because, he said, a relative’s activities as a political dissident had closed off professional opportunities for everyone in his family. His wife was unable to obtain an exit visa because she is a doctor, so he traveled alone. The couple had planned to have children, but chose to put it off, knowing they faced a separation of at least several years. Unwilling to wait longer, in early 2005 they paid someone to bring her out of the country illegally.49

Relatives of “Deserters”

As shown by three of the illustrative cases above (Teresa Márquez and Roberto Salazar, Juan López Linares, and José Cohen), Cuba regularly denies visas to the relatives of “deserters” who have left the country without permission or refused to return at the end of an authorized trip.

Lazaro Betancourt discovered this when he defected from Cuba in 1999 after having served in the government’s security service for twenty years. The United States immediately granted him asylum and, within six months, extended it to his wife and nine-year-old son in Cuba. The Cuban government, however, would not allow them to leave the island. From his time working for the government, Betancourt believes that any former member of the military must wait five years before getting his or her family out. Nonetheless, more than five years have passed since he left, and there is still no sign that his wife and son will be able to leave. Although Betancourt has written repeatedly to the Cuban Foreign Ministry about his family, he has never received a reply.50

Betancourt’s wife and son weren’t the only family members affected, he says. In 2001, Betancourt’s sister, Maydelín Betancourt Morín, won a visa to the United States through the immigration lottery. Her husband and two children automatically received visas as well. However, the Cuban government granted exit visas to her husband and their children, but not to Maydelín herself. Betancourt told Human Rights Watch that officials at Cuba’s Foreign Ministry had told his sister that she would not be granted permission to travel because her brother was a “traitor.”51

Joel Brito’s wife and daughter were separated from him for six years.

© 2002 Private

Joel Brito had a similar experience after defecting in 1997. Brito, who was a senior functionary in the official trade union, the Workers Central of Cuba (Central de Trabajadores de Cuba, CTC), had left the country legally to attend a labor conference in Bolivia, but chose not to return, and found his way instead to the United States.

His wife and ten-year-old daughter obtained visas to enter the United States, but were denied permission to leave by the Cuban government. According to Brito, the only explanation his wife received from the government that hers was “a special case.”52

Brito launched a campaign to get his family out, which entailed repeated letters to Fidel and Raul Castro, as well as appeals for help from international labor and human rights organizations. His wife also appealed directly to her husband’s former colleagues at the CTC. Finally, in 2003, after six years of campaigning, the government relented and granted the two exit visas—though it never provided an explanation for the permission being granted then and not earlier.53

The denial of exit visas to the relatives of “deserters” is hardly a new policy in Cuba. One well-known case dates back to 1980, when Cuban jazz artist Paquito D’Rivera defected during a tour of his jazz ensemble in Madrid in 1980. D’Rivera sought permission for his wife and son to join him, but the Cuban government denied them exit visas. For nine years, D’Rivera persisted in seeking permission, but was repeatedly rebuffed, without any explanation. He was only able to get them out in 1989 by bribing some officials.54

Another musician who suffered a lengthy separation from his family is composer Jorge Rodríguez, who obtained a six-month visa to travel to Mexico in 1992 and chose to stay there. Twice during his time in Mexico, Rodríguez appealed to Cuban officials to allow his wife and eleven-year-old daughter permission to join him. Although the Mexican government gave the family visas, Cuban authorities would only allow Rodríguez’s wife to leave. Unwilling to abandon their daughter, his wife remained in Cuba until, after a three-year separation, they were finally able to escape illegally in 1995.55

In 2000, Dr. Leonel Cordova fled a medical mission in Zimbabwe and traveled to the United States, where he was granted asylum. He petitioned for permission for his wife and two children, four and eleven years old, to leave Cuba and join him. Only after his wife was killed in a car accident the following year, and members of the U.S. Congress intervened, were his children granted exit visas.56

Joel Moreno Molina, a computer science professor in Havana, went to Peru as part of a government agreement in March 1999 to teach at the Peruvian University of Sciences (Universidad Peruana de Ciencias). When his stay was supposed to end in January 2001, Moreno decided to remain in Peru and, after marrying a Peruvian, he obtained Peruvian residency in July 2001. Expecting their first child in November 2002, Moreno and his wife made plans for Moreno’s mother to come from Cuba to help them at the time of the birth. His mother began the paperwork to obtain an exit permit several months before the anticipated birth. Her employer, the Public Health Ministry, gave her permission to travel, and the Peruvian government gave her a Peruvian resident’s card in July 2002 because she was Moreno’s mother. Nonetheless, according to Moreno, Cuban migration authorities refused to allow her to leave on the grounds that she was the mother of a “deserter.” They told her she must wait three years. They finally allowed her to travel in March 2003, almost four months after the birth.57

Children of People Abroad

The Cuban government also denies exit visas to the children of people whose travel abroad has been officially authorized. The policy appears to be aimed at discouraging those travelers from defecting. “Elena Vargas,” for example, was required to leave her ten-year-old daughter behind in Cuba when she went to work in Mexico and then Peru in the 1990s as part of governmental agreements with universities in those countries. While in Peru, she remarried and decided to stay. But she was unable to get permission for her daughter to join her. Although she was able to visit the daughter in Cuba, she was unable to bring the child to live with her. The child died in an accident on December 30, 2000.58

Zaida Jova and Vicente Becerra are Cuban engineers who traveled to Brazil in 1997 for postgraduate work. Like Elena Vargas, the couple was obliged to leave their seven-year-old daughter, Sandra, in Cuba, they say, as a condition of their travel.59 After the birth of their second child, the couple decided to remain in Brazil permanently. The government of Brazil automatically extended residence status to all members of the family, including Sandra, as part of a policy of keeping families together. Havana, however, refused to allow Sandra to leave. After the intervention of the Brazilian government, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and others, Sandra was finally allowed to reunite with her parents in June 2001, after a four-year separation.60

Denial of Entrance Visas

As the illustrative case of Juan López Linares above shows, in addition to denying exit visas, the Cuban government denies entrance visas to some people after they have left. Dr. Ramón Martínez Martínez, for example, reported that the Cuban government had refused to allow him to return to Cuba to visit his young children whom he has not seen since he left in 1998. Dr. Martínez, a plastic surgeon, traveled to Argentina on December 13, 1998, to visit friends, and then decided to stay. His second wife and child soon joined him. Dr. Martínez’s first wife had died, and Dr. Martínez left their two children—eleven and seven—with their maternal grandparents, in keeping with their mother’s wishes. For the past seven years, Dr. Martínez has been unable to gain permission to return to Cuba to visit his children.61 Officials at Cuba’s consulate in Buenos Aires reportedly told Dr. Martínez that his return to Cuba would be barred “indefinitely.”62 Had he known that he would not be able to see his children for so long, Dr. Martínez said he would never have left.63

Similarly, Joel Moreno Molina, mentioned above, has been repeatedly denied entrance visas to Cuba to visit his family after he overstayed his authorized travel period in Peru. Cuban authorities in Peru told him he would have to wait five years because he was now classified as a “deserter.” In October 2004, Moreno again sought an entrance visa, hoping to celebrate the birthday of his second child with his parents. But the embassy once again informed him that he could not return until five years had passed. 64

The Impact of Cuba’s Travel Restrictions

The Toll of Forced Separation on Families

The forced separation that results from Cuba’s travel policies can cause profound hardship for children separated from their parents. Lazaro Betancourt, for example, reported that his fifteen-year-old son has seen a psychiatrist for help with emotional problems prompted by the absence of his father.65 So, too, has the son of María Elena Morejón, upon reaching Germany after a nearly two-year separation from his parents.

The separation can also have a powerful impact on adults. During her separation from her son, Morejón described her feelings in a letter to U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan:

I struggle between my desperation to see my son and my indignation at having our rights violated: the right of a mother and son to be together, so see the laughter on his innocent face, to dry his tears and comfort him when he cries, to educate him close to me and do what it takes to turn him into a good man as I always dreamed. But worse still, I feel the immense pain of seeing my child’s right to grow up, educate himself, and be nourished by his mother ignored.66

Cuban dissident Rafael León Rodríguez, who can’t visit his children and grandchildren in the United States, told Human Rights Watch: “It is very painful. It’s as if they have cut off your roots,” he said, adding that the most difficult aspect is never having been able to meet his grandchildren.67

Ortelio Vichot, a veterinarian who left Cuba in 1981, told Human Rights Watch that he had been trying to get his son out of the country since 1996. He obtained a U.S. visa for him but, despite repeated efforts on his own part, he has been unable to get the Cuban government to grant his son permission to leave. Although neither he nor his son have received written responses from Cuban authorities, they understand that the reason his son has been denied permission to leave is because he is a doctor by training, even though he no longer practices medicine. “Imagine the anxiety,” Vichot told Human Rights Watch, “For so many years trying to reunite with my son and all the false hopes! I have lived through tremendous frustration.”68

“Javier Sánchez” traveled to South Africa in February 1997 as part of Cuba’s program of medical cooperation with that government. After overstaying his travel authorization, he was declared a “deserter,” preventing him from returning to Cuba and cutting him off from his ten-year-old daughter. In October 2002, the girl’s mother died in a car accident, and Sánchez submitted a request for his daughter to join him permanently in South Africa. Although South Africa promptly granted his daughter a visa, the Cuban authorities would not allow her to leave for another three years.69

Sánchez described the difficulties of becoming an unintentional “deserter”:

It really is not easy to become an exile. You miss the place where you were born, your family, and your friends. You live permanently as a stranger. You are forcibly separated from your family. … It was particularly difficult in our case because a minor had lost the most important person in her life and could not get together with the other most important person. Everything could have been resolved so easily, but it was not possible.70

Even when families are eventually reunited, the forced separation can leave lasting scars. Several people we interviewed reported that their marriages were destroyed by their separation. Others described the lost intimacy with children who have grown up without knowing one or both of their parents.

Paquito D’Rivera, for example, described the impact his forced separation from his family had on his marriage in his autobiography:

It was the year of 1981 and I was walking the streets of New York with my soul broken for my absent son, desperate over the imminent rupture of my marriage as a result of the distance, the threats from Cuban authorities to my wife that they would not let her leave the country. …71

The forced separation would eventually lead to divorce and distance him from his son. “I lost my marriage and the childhood of my son,” D’Rivera told Human Rights Watch. “That’s why my son is almost like a stranger to me. We have a good relationship, but it’s like friends, only not very close friends.”72

Blanca Reyes intended to leave Cuba with her husband and nine-year-old son in 1980, but instead stayed behind with the child when the government denied him permission to travel. Their plan was for her husband to get out and then seek permission to bring his wife and child to join him. But the government would not allow her son to leave the country until 1993. By then, the separation had destroyed their marriage, according to Reyes, who blames the Cuban government for their eventual divorce. “Fidel Castro divorced us. … We had no alternative, we separated because Fidel obliged us to separate. … The distance between Miami and Havana is immense.”73

Reyes also believes the separation did great emotional harm to her son. “What hurt me most,” Reyes told Human Rights Watch, “was the pain my son had to go through. The boy was left without a father. … The boy was barely four years old and before the separation from his father he was a very happy boy. After all these things happened he became a serious boy.”74

Reyes’ son, Miguel Ángel Sánchez Reyes, described the lasting impact this forced separation had on his relation with his father:

I’m a guy who was raised without his father. And when you don’t know how your papá is, you idealize him and when you see him it’s possible he’s like you thought and it’s possible he isn’t. … I stopped seeing [my father] when I was nine years old and I saw him again when I was twenty-one. And at that age it’s difficult to reconnect with your father and it’s very difficult to create that father-son link. Even though we have a good relationship, it’s difficult.75

The High Costs of Reunification Attempts

In addition to the emotional hardship of separation, efforts to circumvent the restrictions can prove very costly. In several of the cases we documented, Cubans felt obliged to pay bribes to get out.76 And, as the case of Paquito D’Rivera illustrates, the bribes often were not enough. The night before his wife and son were scheduled to fly to Miami, police barged into their home and took away their passports. D’Rivera responded by making “a very big scandal around the world.” He bought a fax machine and began sending letters to newspapers “all over the planet” until, after several weeks of intense publicity, the government returned their passports. D’Rivera finally was able to meet them in Miami in January 1989.77

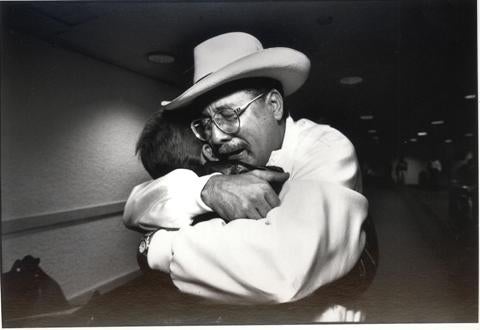

Paquito D’Rivera is reunited with his son after a nine-year separation.

© 1989 Acey Harper/PEOPLE

In addition to the emotional hardship of separation, efforts to circumvent the restrictions can prove very costly. In several of the cases we documented, Cubans felt obliged to pay bribes to get out.76 And, as the case of Paquito D’Rivera illustrates, the bribes often were not enough. The night before his wife and son were scheduled to fly to Miami, police barged into their home and took away their passports. D’Rivera responded by making “a very big scandal around the world.” He bought a fax machine and began sending letters to newspapers “all over the planet” until, after several weeks of intense publicity, the government returned their passports. D’Rivera finally was able to meet them in Miami in January 1989.77

Others have taken even more desperate measures to get their family members out of Cuba. One of the most dramatic cases involved Orestes Lorenzo Pérez, a pilot with the Cuban Air Force who defected in 1991 by flying a MIG-20 jet to Key West, Florida, while on a training flight. 78 Shortly after arriving in Florida, Lorenzo launched a campaign to bring his wife and sons, ten and six, to the U.S. Although he obtained visas for the three to come to the U.S., the Cuban government refused to grant them exit visas. Lorenzo then launched an international campaign to pressure the Cuban government to release his family, presenting his case to President George H.W. Bush and conducting a hunger strike in Spain.79

Despite all his efforts, government officials told his wife that the family would never be allowed to leave the country. So Lorenzo decided to take a drastic action. He borrowed a small plane and sent word to his family through a messenger to wait for him on a well known bridge along the coastal road east of Havana in Northern Matanzas province. At an agreed time, he landed is plane on the road, picked up his family, and returned to the U.S. “It was a chance in a million,” he told NotiSur, “to be able to sneak into Cuba is possible, but to land on a busy roadway … between cars, was indeed a miracle. … The possibility of being captured or gunned down was a high risk, but the liberty of my children was worth it.”80

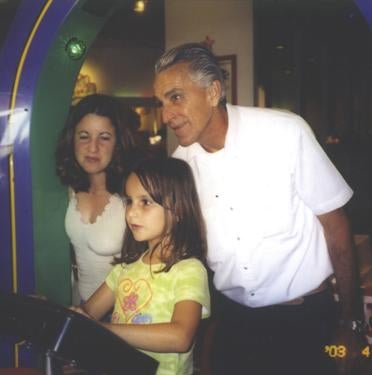

José Contreras

is reunited with his wife and two daughters after a two-year separation.

© 2004 David

Adame/AP

Many thousands of others have opted for a risky escape on the high seas. A well-known recent example is that of José Contreras, now a pitcher in Major League Baseball, who defected from Cuba in October 2002, but was unable to get his wife and young children permission to leave. Officials of the Cuban government reportedly told Contreras’s wife that she and their daughters, eleven and three, would have to wait five years for an exit visa.81 On June 20, 2004, however, the three secretly boarded a thirty-one foot boat with eighteen other Cubans and fled to the United States. They reached South Florida the next morning, allowing Contreras to reunite with his family after a two-year separation.82 Scores of Cubans have drowned attempting such escapes.

Travel Restrictions as Political Coercion

The right to leave a country is an essential ingredient of liberty. It allows individuals to escape repressive political systems. For many Cuban exiles, leaving the island appeared to be the only way to obtain basic political freedoms that they lacked in Cuba. Orestes Lorenzo Pérez, for example, told Human Rights Watch that what drove him to attempt his daring escape was his sense that, in Cuba, “your fate is in the hands of an all-powerful person,” Fidel Castro. “You are not the protagonist in your own life. … You are not the owner of your destiny.”83

Dr. Hilda Molina described the impact that the fear of informers has on daily life. “In Cuba, there is a generalized mask, because you either are with the regime or you pretend to be.”84

For health care professionals, the restrictions on travel create a particularly acute sense that they are being deprived their basic freedoms. As one doctor who left Cuba put it: “You wonder what good your studies have done you. Why study? Instead of benefiting, your studies harm you. … You feel like a prisoner, as if you had committed a crime.”85

Moreover those health care professionals who do apply for permission to leave Cuba must then endure the stigma of being a “deserter” during the three to five (or even more) years they await their visa. “The professional exposes himself to being called ‘traitor,’ ‘gusano,’” one exiled doctor explained. “Because obviously from the moment you say you want to leave there comes all the propaganda against you.”86

The restrictions can also serve as a way of coercing collaboration with the government. Carmen Delia Llano Ochoa suffered house arrest several times in Cuba as a dissident. In 2001, Llano paid a “coyote” who bribed migration officials to purge her files of information about her political activities. This enabled her to leave the island on December 22, 2001, and seek political asylum in Canada. Although Canada granted residency status to Llano, her husband, and her eight-year-old son, Cuba initially refused to allow the latter two to leave the island. Instead, Llano reports, officials at the Cuban Consulate in Montreal tried to compel her to identify government opponents as a condition for getting her family out. Enraged, Llano staged a protest at the Cuban consulate from October 20 until December 10, 2004. On December 12, Havana relented and allowed her son and husband to leave.87

In addition to serving as a way of coercing compliance, the travel restrictions can serve as a form of punishment for political opponents. Rafael León Rodríguez, for example, a fifty-nine-year-old political activist, has been unable to leave despite the granting of a U.S. visa in 2000. He has made repeated requests for an exit visa so that he could visit his three children and four grandchildren who live in Miami. The children left Cuba with his former wife in 1980. He has never met the grandchildren. His requests for exit visas have been ignored or rejected. He reports that the authorities have indicated to him that these rejections are due to his political activity with the opposition group, the Cuban Democratic Project (Proyecto Democrático Cubano).88

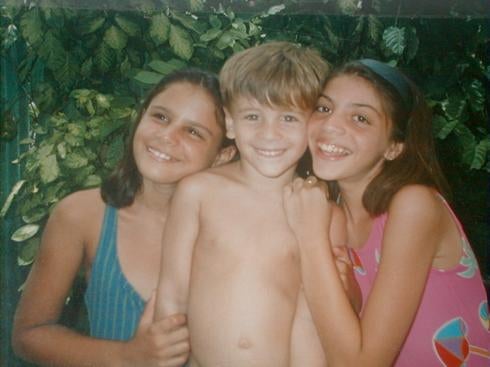

“These wounds never heal,”Edgardo Llompart said of his ten-year separation from his daughter

(seen here with her daughter).

© 2003 Private

Similarly, dissident Edgardo Llompart faced separation from his nineteen-year-old daughter as punishment for his opposition activities and refusal to cooperate with the government. Llompert was among several dissidents freed from prison in 1991 after being convicted of rebellion for organizing an independent political movement in the 1980s. When he was freed, Llompart was offered a choice: cooperate with the government or go into exile. The authorities allowed him to take his son and wife to the United States, but refused permission for his daughter, Ibet Llompart, to leave for another ten years. “My emotional and physical life were very much affected” by the separation, Llompart told Human Rights Watch. “Every time we served a plate of food, knowing that our daughter was far away and not at our side was very hard. … These wounds never heal.”89

The threat of separation is compounded by the harassment of family members left behind, who face a wide range of forms of persecution, from layoffs to social repudiation. Joel Brito’s wife, for example, was fired from her job as budget director for the city of Havana after Brito stayed outside of Cuba following a conference in Bolivia. According to Brito, his wife faced frequent insulting phone calls urging her to publicly denounce her husband, something she steadfastly refused to do. State security agents interviewed her for several hours about her husband, pressuring her to call him a traitor, and telling her, falsely, that Brito had found a new wife and was starting a new family in the U.S.90

Composer Jorge Rodríguez told Human Rights Watch that his wife and daughter suffered persistent harassment after he left them in Cuba. They were forced to leave their apartment because of the hostility of their neighbors. His daughter’s classmates at school taunted her, saying that her father was a traitor. Security officials detained his wife on multiple occasions and told her that she would never see Rodríguez again. His wife’s salary was lowered, leading her eventually to quit her job.91

Miguel Ángel Sánchez Reyes told Human Rights Watch about the stigma he felt as the son of a “deserter”:

At first I thought my father was a traitor. You have to deal with … the fear that those people around you will find out that your father has deserted Cuba. You don’t tell people. If they ask where your father is, you say that he’s not here, or that your father separated from your mother but you never say that he left Cuba because you have a gigantic fear of rejection … by other students and by society. The people who know you reject you because you are the son of a deserter. They won’t get together with you. I was always afraid I’d run into people in the street and they’d stop me and say something so that soon more people would find out who my father was. It’s the fear of rejection. And at the same time, it is difficult to dissemble and pretend you’re happy.92

In the course of researching this report, Human Rights Watch encountered numerous people who were afraid to speak to us about their cases, even when assured anonymity. One of the principal fears that these and other Cubans had was that they or their relatives would be denied permission to leave or enter Cuba. “I ask you not to use my name,” one woman in Miami said at the end of one interview, “because my mamá is still in Cuba and I’m going to visit her next year. … I don’t want them to prevent me from going and they’ll say to me, ‘You were saying things, you were talking.’”93

Similarly, “Elena Vargas” told Human Rights Watch that she did not want her name to be made public in this report because she feared that her family would be subject to harassment. “In Cuba there is a lot of fear,” she said. “Fear of knowing, fear of showing solidarity, fear of what people may find out. When you are in Cuba you don’t want to know what happened or you don’t want them to think you are an accomplice because you don’t want them to leave you without soap, without cooking oil.”94

Dr. Hilda Molina provided Human Rights Watch with details of three additional cases—and said she knew of many more—involving acquaintances who were denied exit visas but told her they were unwilling to be interviewed out of fear of the possible negative consequences. “It’s a form of psychological blackmail,” she said. “They think that if they shut up and please the government maybe someday the government will give them permission [to travel].”95

Forced separation is, in other words, one of the most effective tools for preventing people from talking about the travel restrictions, or criticizing other policies of the Cuban government. As rights advocate Rafael León Rodríguez put it, “The threat of denying permission to travel is a weapon of deterrence used to intimidate, repress, and control various types of activities.”96

[1] Guillermo J. Grenier and Lisandro Pérez, The Legacy of Exile: Cubans in the United States (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2003), p. 26.

[2] Ibid. See also Susan Eckstein and Lorena Barberia, “Cuban-American Cuba Visits: Public Policy, Private Practices,” (Published as part of the Mellon Reports series, January 2001).

[3] Grenier and Pérez, The Legacy of Exile: Cubans in the United States, pp.23-24; Eckstein and Barberia, “Cuban-American Cuba Visits: Public Policy, Private Practices.”

[4] Grenier and Pérez, The Legacy of Exile: Cubans in the United States, pp.24-25; Eckstein and Barberia, “Cuban-American Cuba Visits: Public Policy, Private Practices.”

[5] U.S. Department of State, “Cuba Human Rights Practices, 1995,” March 1996, http://dosfan.lib.uic.edu/ERC/democracy/1995_hrp_report/95hrp_report_ara/Cuba.html (retrieved June 12, 2005).

[6] Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, República de Cuba, “Servicios Consulares,” http://www.cubaminrex.cu/consulares/serv_consintro.htm (retrieved February 21, 2005).

[7] The legal process for leaving Cuba is expensive and, for professionals, complicated. Those who are employed must first ask permission to leave from their employer, who passes the request along to the relevant governmental ministry. Once the ministry has approved the request (a process that can take years), it is passed on to the migration bureau of the Interior Ministry. Nonprofessionals go directly to the migration bureau. The applicant must then purchase a Cuban passport for $50. The exit permit costs an additional $150, which is not returned even if the permit is denied. The final step is a medical examination costing $450. All of these fees are exorbitant for Cubans.

[8] Cuba reached an accord on emigration with the United States in May 1995 in which it pledged not to apply the illegal exit law against repatriated Cubans. Yet its failure to revoke this law seriously calls into question its willingness to legitimize the basic right of its citizens to leave their country.

[9] Cuba’s Criminal Code, Article 216. Translation by Human Rights Watch.

[10] Cuba’s Criminal Code, Article 217. Translation by Human Rights Watch.

[11] Cuban Commission of Human Rights and National Reconciliation, “Lista Parcial de Sancionados o Procesados por Motivos Políticos o Político-Sociales,” July 5, 2005.

[12] Cuba’s Criminal Code, Article 215. Translation by Human Rights Watch.

[13] As noted above, the 1995 migration agreement between Havana and Washington requires the United States to award at least 20,000 resident visas to Cubans each year. Approximately 85 percent of the Cubans immigrating to the U.S. through this mechanism are chosen by lottery, according to the State Department. Many of the others are family members.

[14] Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Jim Bean, deputy director, Office of Cuban Affairs, U.S. State Department, March 29, 2005.

[15] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Jim Bean, deputy director, Office of Cuban Affairs, U.S. State Department, March 30, 2005.

[16] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Roberto Quiñones, Buenos Aires, Argentina, February 2, 2005; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Hilda Molina, Havana, Cuba, April 18, 2005; and letter to José Miguel Vivanco, executive director of the Americas Division of Human Rights Watch, from Dr. Roberto Quiñones, February 23, 2004.

[17] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Hilda Molina, Havana, Cuba, April 18, 2005. The comment, reported to Human Rights Watch by Dr. Molina, is consistent with language employed in a letter by the Cuban ambassador to Brazil, referring to the “theft of brains,” (see footnote 34), as well language employed by President Fidel Castro, referring to Cuba as an “incubator of brains” (see footnote 45).

[18] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Hilda Molina, Havana, Cuba, April 18, 2005.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid; “Una carta de Kirchner apela a la sensibilidad de Fidel Castro,” La Nación, December 5, 2004, http://www.lanacion.com.ar/politica/nota.asp?nota_id=660281 (retrieved February 5, 2005).

[21] According to Dr. Quiñones, a immigration official stopped him from following his wife onto the plane when the couple tried to leave, even though his passport and exit visa were in order. When Dr. Quiñones then requested that his wife and luggage be taken off the plane, the guard refused, saying that his wife, who was Argentine, must leave. When she learned what was happening, his wife objected and tried to run down the stairs off the plane. She was stopped by several soldiers. However, after the other passengers, many of them Mexican tourists, protested in favor of Dr. Quiñones’s wife, Dr. Quiñones was finally allowed to board the plane and leave. Dr. Hilda Molina filed a complaint about the incident, and was informed that her son had been mistaken for someone else. Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Roberto Quiñones, Buenos Aires , Argentina, February 2, 2005.

[22] Ibid; and “Una carta de Kirchner apela a la sensibilidad de Fidel Castro,” La Nación, December 5, 2004; “Una carta de Fidel Castro evitó una seria crisis con Cuba,” La Nación, December 15, 2004, http://www.lanacion.com/ar/politica/nota.asp?nota_id=660286, (retrieved February 5, 2005).

[23] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Teresa Márquez” (not her real name), Mexico, May 2, 2005. Márquez is one of many Cubans or Cuban Americans interviewed who requested that their names be changed to protect members of their family in Cuba.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with María Elena Morejón, Hannover, Germany, April 5, 2005.

[26] María Elena Morejón, “Petición de Reunificación Familiar, presentada para que sea examinada de conformidad con el Protocolo Facultivo del Pacto Internacional de Derechos Civiles y Políticos,” undated.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Letter from María Elena Morejón to Embassy of Cuba, March 1, 2003, http://www.lanuevacuba.com/nuevacuba/peticion-1.htm (retrieved April 7, 2003). Translation by Human Rights Watch.

[33] Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Juan López Linares, December 16, 2002; see also Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, República de Cuba, “Servicios Consulares,” http://www.cubaminrex.cu/consulares/serv_consintro.htm (retrieved February 21, 2005).

[34] Letter from Jorge Lezcano Pérez, Cuban ambassador to Brazil, to Eduardo Matarazzo Suplicy, Brazilian senator, August 15, 2002. Translation by Human Rights Watch.

[35] Letter from Juan López Linares to Jorge Lezcano Pérez, Cuban ambassador in Brazil, September 4, 200. Translation by Human Rights Watch.

[36] Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Juan López Linares, February 15, 2005.

[37] Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Juan López Linares, July 27, 2005.

[38] Human Rights Watch interviews with José Cohen, Miami, Florida, August 17, 2004, April 4, 2005, and May 19, 2005; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Isaac Levy Cohen and Daysi Cohen, Havana, Cuba, April 21, 2005.

[39] Human Rights Watch interview with José Cohen, Miami, Florida, August 17, 2004.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Of the 1762 cases reported from 2004 through March 2005, 886 involved health care professionals.

[42] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. “Julio Alfaro” (not his real name), West Palm Beach, Florida, May 13, 2005.

[43] “Cuba afirma que “controlara” la migración de profesionales a EEUU,” Agence France-Press, August 31, 2000.

[44] Speech by President Fidel Castro at a mass rally in the “José Martí” Anti-imperialist Square, Havana, November 27, 2001, http://www.cubaminrex.cu/Archivo/Presidente2001/FC_271101,htm. Translation by Human Rights Watch.

[45] Speech by President Fidel Castro at the closing of the VI Congress of the Committees in Defense of the Revolution (CDR), in the “Karl Marx” Theater, September 28, 2003, http://www.cuba.cu/gobierno/discursos/2003/esp/f280903e.html (retrieved March 30, 2005). Translation by Human Rights Watch.

[46] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Carlos Marrero, husband of Dr. Almaguer, Jacksonville , Florida, April 4, 2005.

[47] Human Rights Watch interview with Arturo Morejón, Miami, Florida, August 18, 2004.

[48] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. “Jorge Ramos” (not his real name), Miami, Florida, February 21, 2005.

[49] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Roberto Gómez” (not his real name), Florida Keys, Florida, May 10, 2005.

[50] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Lazaro Betancourt, Miami, Florida, August 20, 2004.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Human Rights Watch telephone interview s with Joel Brito, Miami, Florida, August 17, 2004, and April 13, 2005.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Paquito D’Rivera, Weekawken, New Jersey, May 11, 2005.

[55] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Jorge Rodríguez, Hackensack, New Jersey, May 5, 2005.

[56] “Castro holds children hostage,” TNA News with Commentary, June 23-24, 2001, http://www.newaus.com.ua/news254castro.html (retrieved November 19, 2002).

[57] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Joel Moreno Molina, Lima, Peru, March 30, 2005.

[58] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Elena Vargas” (not her real name), Lima, Peru, April 13, 2005.

[59] Agustín Blazquez, “Sandra,” Cuba InfoLinks news & information services, 2001, http://www.cubainfolinks.net/Articles/sandra.htm (retrieved November 7, 2002).

[60] Ibid; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Annual Report 2001, Chapter IV(a) Cuba, para. 14; Vicente Becerra and Zaida Jova, “Sobre la llegada de nuestra hija cubana Sandra a Brasil: declaración de gratitud y esperanza,” http://www.cubdest.org/0106/csanzyv.html (retrieved February 21, 2005).

[61] Letter from Dr. Ramón Martínez Martínez, forwarded to Human Rights Watch from Juan López Linares, August 11, 2004; and “Silencio de Cuba en el caso de un médico,” Clarín, July 22, 2004, http://old.clarin.com/diario/2004/07/19/sociedad/s-03402.htm (retrieved February 21, 2005).

[62] “Desde Cuba, reclaman que un médico pueda visitar la Isla para ver a sus hijos,” July 29, 2004, infobae.com, http://www.infobae.com/notas/nota_imprimir.php?Idx=129324 (retrieved January 31, 2005).

[63] “Silencio de Cuba en el caso de un médico,” Clarín, July 22, 2004.

[64] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Joel Moreno Molina, Lima, Peru, March 30, 2005.

[65] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Lazaro Betancourt, Miami, Florida, August, 2004.

[66] Letter from María Elena Morejón to U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan. Undated.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Human Rights Watch interview with Ortelio Vichot, Miami, Florida, April 20, 2005.

[69] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Javier Sánchez” (not his real name), Cape Town, South Africa, July 6, 2005.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Paquito D’Rivera, My Vida Saxual (Editorial Plaza Mayor: San Juan, 1999), pp. 49-50. Translation by Human Rights Watch.

[72] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Paquito D’Rivera, Weekawken, New Jersey, May 11, 2005.

[73] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Blanca Reyes, Havana, Cuba, May 4, 2005.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Miguel Ángel Sánchez Reyes, Miami, Florida, May 9, 2005.

[76] Human Rights Watch interview with Joe García, then-executive director, Cuban American Foundation, Miami, Florida, August 17, 2005; telephone interview with Isaac Levy Cohen and Daysi Cohen, Havana, Cuba, May 19, 2004; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Roberto Gómez” (not his real name), Florida Keys, Florida, May 10, 2005; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Paquito D’Rivera, Weekawken, New Jersey, May 11, 2005.

[77] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Paquito D’Rivera, Weehawken, New Jersey, May 11, 2005.

[78] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Orestes Lorenzo Pérez, Osceola, Florida, May 2, 2005; Javier González Muruato, “La mirada de Orestes Lorenzo,” El Siglo de Torreón, May 1, 2005.

[79] Mike Wilson, “Daring Act of Love Focuses Public's Eye on Cuba,” The Miami Herald, January 2, 1993, and Deborah Sharp and Sandra Sanchez, “Pilot Swoops family out of Cuba,” USA Today, December 21, 1992.

[80] “Two Groups of Cubans Flee Island by Plane,” NotiSur, January 1, 1993.

[81] “NY Yankees Pitcher José Contreras feels betrayed by Castro,” Havana Journal, February 19, 2004, http://havanajournal.com/culture_coments/P1432_0_3_0/ (retrieved January 30, 2005).

[82] “Contreras’ [sic] wife, two daughters are in Florida,” ESPN News Service, June 22, 2004, http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/print?id=1826440&type=story (retrieved January 30, 2005).

[83] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Orestes Lorenzo, Osceola, Florida, May 2, 2005.

[84] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Hilda Molina, Havana, Cuba, April 18, 2005.

[85] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. “Julio Alfaro,” West Palm Beach, Florida, May 13, 2005.

[86] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Alfredo Melgar, Miami, Florida, April 22, 2005.

[87] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Carmen Delia Llano Ochoa, Montreal, Québec, Canada, January 31, 2005.

[88] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Rafael León Rodríguez, Havana, Cuba, April 28, 2005.

[89] Human Rights Watch interview with Edgardo Llompart, Miami, Florida, April 27, 2005.

[90] Human Rights Watch interview with Joel Brito, Miami, Florida, August 17, 2005.

[91] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Jorge Rodríguez, Hackensack, New Jersey, May 5, 2005.

[92] Human Rights Watch interview with Miguel Ángel Sánchez Reyes, Miami, Florida, May 9, 2005.

[93] Human Rights Watch telephone interview, Miami, Florida, May 6, 2005.

[94] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Elena Vargas” (not her real name), Lima, Peru, April 13, 2005.

[95] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Hilda Molina, Havana, Cuba, June 7, 2005.

[96] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Rafael León Rodríguez, Havana, Cuba, April 28, 2005.

| <<previous | index | next>> | October 2005 |