<<previous | index | next>>

III. U.S. Travel Restrictions

Background

Past Travel Restrictions

Since shortly after Fidel Castro came to power in 1959, the United States has used a combination of covert and overt measures aimed at ousting him, including numerous assassination attempts. The most enduring of these measures has been the U.S. trade embargo, which has remained in place for more than forty years.97

Travel restrictions to Cuba, a central component of the embargo, date from a January 16, 1961, notice issued by the State Department that proclaimed travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens to be “contrary to the foreign policy of the United States and ... otherwise inimical to the national interest.” Since that day, travel restrictions have been alternately tightened and eased at different moments by successive administrations.

Under the 1961 State Department notice, anyone traveling to Cuba was required to receive a specific endorsement in his or her passport from the State Department. A 1967 U.S. Supreme Court ruling held that travel without a specifically endorsed passport did not constitute a crime under the relevant statute.98 However, Treasury Department regulations barring financial transactions related to travel to Cuba, promulgated in 1963 under the Trading With the Enemy Act of 1917, are criminally enforceable. Consequently, those who travel to Cuba without a Treasury Department license can be prosecuted for their use of U.S. currency in Cuba—a technicality which enables the U.S. to restrict travel to Cuba under the guise of limiting financial transactions. These measures have endured as the principal means of restricting U.S. travel to Cuba. The Treasury Department grants some licenses to travel, but the categories of these exceptions have been narrowed or broadened at different points over the past four decades.99

Family-related travel is one of the exceptions that has existed on and off since the 1970s. As part of a broader initiative in U.S.-Cuban relations, President Carter let the entire travel ban lapse in 1977, but restrictions were re-imposed in 1982 by President Ronald Reagan. While the Reagan administration banned most travel to Cuba, its new regulations did permit family-related travel to continue. In response to the rafter crisis of 1994, President Clinton suspended the general license for family travel, but then restored it in late 1995, as part of an effort to broaden people-to-people contacts between Cuba and the United States. In 1999, along with other measures to ease the travel ban, expand charter flights, and increase people to people contact, the Clinton administration dropped a requirement that family visits, whether on general or specific licenses, must respond to “extreme” humanitarian need. Cuban-American family visits to Cuba increased significantly in the second half of the 1990s.100

President George W. Bush initially continued the trend of easing the requirements for family-related travel, introducing, in March 2003, new regulations that established a general license, which allowed individuals to travel to Cuba to visit family once a year, without requiring them to seek special permission. The 2003 regulations also allowed individuals to apply for specific licenses to make additional visits each year, and allowed visits to relatives “no more than three generations removed from that person or from a common ancestor.”101

New Restrictions on Family-Related Travel

In 2004, President Bush’s Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba released a report that found, among other things, that a chief beneficiary of Cuban travel to and from the island is Fidel Castro himself. “[T]he regime,” it concluded, “has effectively been provided an institutionalized safety valve for Cuban discontent with an accompanying revenue generator.”102 By attaching high fees to the various transactions involved in travel, and by requiring Cubans to buy in government-owned stores in Cuba, Castro has turned this travel “into a significant cash windfall to the regime.”103 The commission estimated that, in 2003, roughly 125,000 people traveled to Cuba to visit relatives (with some 31,000 making multiple trips) and the Cuban government was able to generate $96.3 million in hard currency from these visits.104 As a result, the commission asserted, “it is the Cubans who recently migrated who have become one of the largest sources of funds and goods to the island.”105 Strengthening the embargo, the commission recommended, required reining in this travel.

So in June 2004, the administration established new regulations for family-related travel. Under these regulations, individuals can only visit Cuba under specific licenses, which can only be granted once every three years. Specifically, individuals are prohibited from traveling to Cuba to visit family members if, within the previous three years, they have emigrated from Cuba, or returned from travel to Cuba under the general license program, or received a specific license to visit family. The visit cannot last more than fourteen days.106

The regulations also limit the definition of “immediate family” to mean “any spouse, child, grandchild, parent, grandparent, or sibling of that person or that person’s spouse, as well as any spouse, widow, or widower of any of the foregoing.”107 Excluded are aunts, uncles, nephews, nieces, cousins, and other such relatives, no matter what role such persons might have played in an individual’s life before the separation. The new regulations also prohibit individuals from sending money or care packages to anyone other than a parent, grandparent, child, grandchild, sibling or spouse. They also limit the quantity and frequency of such gifts per receiving household, where before they had been limited per individual (allowing people to send multiple gifts to single households, as well as to non-relatives).108

Unlike past travel restrictions, the new regulations allow for no exceptions. Individuals who violate the restrictions on visits to relatives may be subject to penalties of $4000 if they have received prior notification from the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), and $1000 if they have received no such prior notice.109

In early 2005, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with twenty-five Cubans living in the United States who have been unable to obtain permission to visit their families in Cuba since the new restrictions went into effect. These cases illustrate the profound hardships that enforced separation can cause families. Knowledgeable sources in the Cuban American community in Miami estimate that hundreds of other families have suffered similar problems due to the new travel restrictions. The director of a Miami-based travel agency that specializes in travel to Cuba told Human Rights Watch: “Not a day goes by without someone coming in anxious, crying, desperate to visit their family.”110

Illustrative Cases

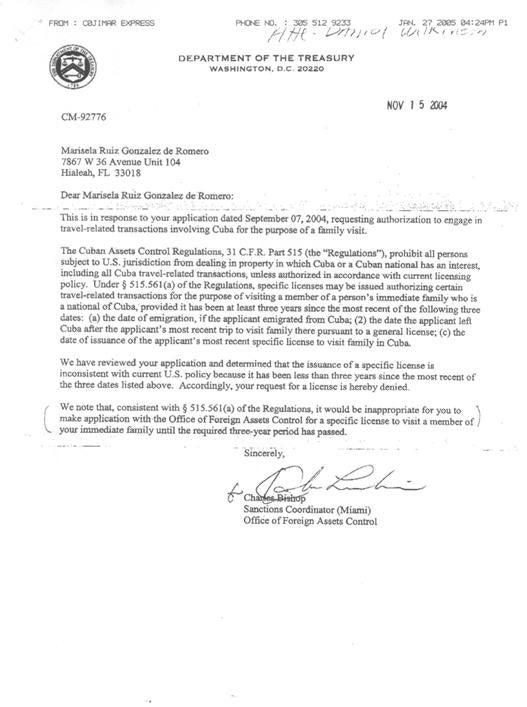

Marisela Romero

Before the new travel restrictions went into effect, Marisela Romero, fifty-three, had been visiting Cuba several times a year to help her eighty-seven-year-old father, who was in the advanced stages of Alzheimer’s disease and incapable of taking care of himself. He needed help eating and regularly urinated on himself, requiring others to change his sheets, his clothes, and the diapers he was forced to wear.111

Marisela

Romero’s last visit with her father.

“Whenever she came he became very

contented,” her nephew’s

wife recalled. “

Because even though he had Alzheimer, he knew who she

was.”

© 2004 Private

Romero had left Cuba in 1992, and after her mother and sister both died in 2002, the only remaining relatives who could take care of her ailing father were her nephew and his wife. Romero hired two people to help them and began making frequent trips to Cuba so that she could pay these helpers, bring money and supplies, and, perhaps most importantly, provide her father with filial affection. “Whenever she came he became very contented,” Marisol Claraco, her nephew’s wife, told Human Rights Watch. “Because even though he had Alzheimer, he knew who she was. … She would lie next to him and talk to him, and he would feel her love and get better.”112

“We were desperate,” the wife of Romero’s nephew recalled.

“We saw him deteriorate day by day, and she wasn’t able to come, and we couldn’t do anything.

We were suffering on this side and she was suffering on that side.”

© 2003 Private

The new restrictions put a halt to her visits. Since her last trip had been in May 2004, she would not be eligible to visit her father again until 2007. The regulations also effectively prevented her from sending money for his medical care and other expenses. While she was still allowed to send remittances to members of her “immediate family,” the only relative in Cuba who fit that definition was her father, and he was incapable of cashing checks or even signing them over to someone else. (Under the regulations, her nephew did not qualify as a member of her “family.”) It also became much more difficult and expensive to send supplies as it became harder to find other people traveling to Cuba and willing to carry goods for her.113

Ms. Romero’s absence was felt by her nephew and his wife. “After the restrictions,” Claraco told Human Rights Watch, “I was alone with the old man and my husband was in charge of going and finding what medicines he could. We were waiting for Mari to come. But she couldn’t come and she couldn’t send the pampers and the medicines. So we had to endure rough times.” After several months, they began to run out of diapers and basic medical supplies, such as iodine and hydrogen peroxide, which they needed to clean his bed sores.114

Romero was

notified by OFAC that “it would be inappropriate” for to seek permission to visit

her family

in Cuba “until the required three-year period has passed.”

Her absence also seems to have had an impact on her father’s health. “When she wasn’t able to come, he started to get quieter and quieter, he started to get worse, as if he was debilitating little by little,” Claraco said. “We were desperate. We saw him deteriorate day by day, and she wasn’t able to come, and we couldn’t do anything. We were suffering on this side and she was suffering on that side.”115

In September, Romero learned from her father’s doctor in Cuba that he had become deeply depressed, most likely because of her extended absence, and stopped eating. She was torn about what to do. “I would have gone every month,” she said. “I would have stayed with him. I would have made sure he was taken care of. But I was afraid of breaking the law.”116

She decided to submit a request to the Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) for permission to travel, hoping that an exception might be made given her situation. She still had not received a response in October, when her nephew alerted her that her father had been hospitalized and was in very serious condition. She called OFAC twice, leaving a message on voicemail but received no reply. Meanwhile, her father’s condition deteriorated. And finally, on October 20, he died.

The following month, Romero received a letter from OFAC responding to her September request for permission to visit her father. The request was denied. She was not authorized to travel until 2007.

Four months after her father’s death, Ms. Romero told Human Rights Watch that she still had not recovered from the trauma. “I’m in very bad shape. I can’t live normally. It’s torture, night after night, minute after minute.” The main source of her anguish is the knowledge that she was unable to be with her father when she believes he needed her most. “He died alone. There was no one to summon a priest for him. We never had a chance to say goodbye.”117

Romero’s anguish is compounded by her anger at having her freedom to travel restricted by the U.S. government:

I came to this country in search of freedom, not for economic reasons. I remember when I saw myself in the Miami Airport, the first thing that came to my mind was, “Oh my God, I am free!” And now I feel like someone is taking away this freedom that I came here for. … They have taken away from me the right to go to see my family when I want to. … How can such a beautiful country have a law like this?”118

Andrés Andrade

Andrés Andrade, age fifty, who migrated in 1980 “looking for new opportunities,” had been returning regularly to Cuba in recent years to help his sister, Arelis Andrade López, take care of their parents, including a mother who was battling cancer.119

“He was a great support for me,” Arelis Andrade told Human Rights Watch. “I am alone here, my sons are young and they have to work.” But with the restrictions in place, she could no longer count on his help. “It was horrible because I couldn’t have him next to me … I was not able to have my brother’s emotional support … I missed my brother a lot.”120

In November 2004, their mother developed a severe pulmonary problem and had to be hospitalized. In the past, Andrés Andrade would have been able to travel to Cuba to help his sister care for her mother. But this time she was alone. “I spent four straight days without any sleep, sitting on a chair next to her,” Arelis Andrade recalled.121

Andrés Andrade’s absence was even harder on their dying mother. “She was holding on to life because she hoped that he would come,” Arelis Andrade recalled.

She wanted him to come, but at the same time she would say, “Tell him not to come, because I don’t want him to get in trouble.” Sometimes she did not want to eat, and I would tell her “Look Mima, you have to eat, because my brother is going to come to see you and he has to see that you have been eating.” I would have to tell her such “merciful lies,” as they say. But she died. She died longing to see my brother. … That day before she died, the screaming was horrible. She wept and cried out his name.122

After she died, Arelis Andrade sent her brother the news via email. “He called me crying, saying that he had not been able to see my mom, that he would have been able to see her before she died, if it hadn’t been for the restrictions.”123

Andres Andrade with his mother. “She died longing to see my brother,” his

sister said.

“That day before she died, the screaming was horrible.

She wept and cried out his name.”

© 2002 Private

Their mother’s death also had a devastating impact on their eighty-two-year-old father, a diabetic with high blood pressure who has survived three heart attacks. According to Arelis Andrade, losing his wife after a sixty-year marriage provoked a deep depression that has further undermined his already precarious health.124

In the past, Andrés Andrade had regularly sent his father medicines and, at times when his situation grew more critical, traveled to Cuba himself with enough medical supplies to last months. Under the new restrictions he is only able to send $100 a month, which he insists is not enough to cover his father’s needs. Moreover, he will not be able to visit again until 2007 and he fears that his father will have died by then. The travel restrictions, he says, “have affected me a great deal emotionally.” His inability to visit his family and provide them great support has caused him a feeling of “helplessness.”125

As in the final stage of their mother’s illness, Arelis Andrade must assume the full burden of her father’s care.

Currently, I take care of my dad, but I am alone … He is a very difficult person to take care of. He is very stubborn and he always wants to get his way … When my mom died, I would tell him “Pipo, don’t worry,” but he would cry. … He still can’t believe that she died and he starts crying.126

Like their mother before she died, she says, he is extremely distressed that he cannot see her brother.

Everyday he tells me that he is waiting for Andrés to come, because he has a gift for him that my mom gave him, and that it is something he can only tell him. And I ask him “Pipo, what is it that you have to give him, to tell Andrés?” But he only tells me that it is something that he must tell Andrés himself … He can hardly see and he is practically deaf. He is very thin. He says that he wants to go join my mom, that he wants to die, but that before he goes he wants to see Andrés to give him the gift that my mom left him. I pray to God everyday that my dad makes it until 2007 … But he is eighty-two years old already and he is very sick. … Sometimes, when I despair, I sit out on the patio alone and cry.127

Leandro Seoane

Leandro Seoane’s ties to his family were first tested when, at age fifteen, he told his parents he was gay. Refusing to accept this news, his father took him to a psychologist and then a psychiatrist in Havana. “When the psychiatrist told my father that I wasn’t going to change—that the one who’d have to change was him—he was heartbroken,” Seoane recalls.128

Leandro Seoane at age six with his mother in Havana.

© 1970 Private

A year later, Seoane was walking home with some friends one evening when he was picked up by the police, thrown in a jail with dozens of other openly gay men, abused verbally, held overnight, and, before being released the next morning, told he had a choice: he must leave Cuba or go to prison.

The year was 1980, the Mariel boatlift was getting underway, and the Cuban government had decided to use the exodus to send gays—as well as prostitutes, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and convicted criminals—out of the country. By the time Seoane had his interview for an exit visa several weeks later, many people eager to leave the island had began claiming, falsely, that they too belonged to one of these stigmatized categories, prompting the authorities to scrutinize each claim closely.

Although his parents had still not fully reconciled themselves to his sexual orientation, they were determined to help their son escape persecution because of it—which meant helping him convince the authorities that he was in fact gay. So they accompanied him to his interview and, beforehand, his mother applied makeup to his face and lent him her jewelry.

After a humiliating interview, Seoane obtained the authorization and soon traveled along with thousands of other Cubans to Miami. Shortly after he had settled in, he received a letter from his father who suggested that he should take the opportunity of starting afresh in a new country to change his lifestyle. “I wrote back to him right away,” Seoane recalls. “And I told him that if he ever said anything like that again, he would never hear from me again. He would no longer be my father.”129

Seoane’s father wrote back, apologized, and never repeated the suggestion, thus avoiding a family rupture. But they remained separated nonetheless by the distance between them and the fact that, throughout the 1980s, the Cuban government refused to let the “Marielitos” (Cubans who had left on the Mariel boatlift) return to Cuba.

It wasn’t until 1989 that Seoane had a chance to see his parents again, when they visited the United States and got to see him living with a long-term male partner. Two years later, in 1991, Seoane was finally able to return to Cuba. One day while he was there, his family sat down together on the floor of their Havana home and talked about what they had been through. “My father told me that he had been wrong, that he had come to see that his son was a true man,” Seoane recalls. “He even said he had come to see that I was braver than most men.”130

Seoane visiting his parents in Havana. “Oh, my lord, when will I see Leandro?”

Seoane’s father said when he learned of the new restrictions.

“From now to when Leandro comes, I don’t know what could happen.”

Within six months he had died of cancer.

© 2003 Private

After that reunion, Seoane returned to Cuba seven or eight times to visit his family, until his last visit in March 2004. His parents looked forward to these visits and were greatly distressed when the new travel restrictions went into effect. Seoane’s mother recalled her husband’s reaction: “When he found out that his son would not be allowed to travel for three years, he said ‘Oh, my lord, when will I see Leandro? From now to when Leandro comes, I don’t know what could happen.’ You see, he foresaw that he wouldn’t ever see him again.”131

In August 2004, Seaone’s father, eighty-three, was diagnosed with throat cancer. In the following weeks his health deteriorated rapidly. “If I could have traveled then, I would have,” Seoane said. “I would have spent time with him. I knew he would have done better.”132 But unable to travel, he called Cuba repeatedly, running up monthly telephone bills as high as $600.

Seoane’s father died on November 14. His mother described the sadness that had afflicted him during his final weeks. “He was really hoping that Leandro would come to see him. I don’t think he would have died so quickly if Leandro could have come.” And she recalled Seoane’s reaction to the news: “My son was desperate because he could not come,” she said. “He didn’t know what to do. … He called me every day, asking how I was and, poor guy, he spent a lot of money calling me.”133

Seoane is still bitter about not being able to be with his family during his father’s illness and then for his funeral. “Here in this country they talk so much about family values,” he said. “But what could be more valuable than reuniting a family?”134

Carlos Lazo

After seven months serving as a combat medic in Iraq, there was nothing U.S. Army Sergeant Carlos Lazo wanted more during his two-week furlough than to see his two teenage sons in Havana. He would soon be back on the frontlines and, having already seen the carnage there firsthand, he realized there was a chance he might never see them again.135

But when he arrived in Miami in June 2004, he was stunned to learn that, because of the new restrictions, he could not travel to Cuba. As he saw it, “the administration that trusted me in battle in Iraq does not trust me to visit my children in Cuba.”136

Sgt. Carlos Lazo

in Iraq with photos of the teenage sons he was unable to visit during his furlough.

“[T]he administration that trusted me in battle in Iraq does not trust me to visit my

children in Cuba,” he complained.

© 2004 Private

Lazo had left Cuba on a raft in 1992 “for the same reasons immigrants have always come to these shores: to taste freedom, to take advantage of the economic opportunities and to build a better life for the people I cared about.”137

He returned to school for a counseling certificate, moved to Seattle where he got a job working with people with developmental disabilities, and, at the age of 35 joined the Washington National Guard.

Although he had become a U.S. citizen, he maintained close ties with his family in Cuba, sending money every month to his sons and other relatives, and visiting once a year—and even more often when his father fell ill. His last visit was in April 2003.

Forced to return to Iraq without seeing his family in Cuba, Sergeant Lazo would soon witness some of the heaviest fighting of the war while providing backup to the Marines during the battle of Falluja in November 2004.

Safely back in the United States at the end of his tour, he no longer fears he will die without seeing his family in Cuba again. Yet the travel restrictions are still taking a heavy toll on him. “I can’t help out my sons,” he told Human Rights Watch. “I can’t give them human warmth. I can’t fulfill my obligation as a father. I can’t send money to my uncles because they are no longer part of my family.”138

The separation has also taken a toll on his sons. “Three years is too long,” his eighteen-year-old son told an NBC News reporter. “I miss him when I’m alone. When I don’t have anyone to talk to. When I’m with my friends. When my friends are talking about their fathers. There’s a hole because he’s not with me.”139

By keeping him from his sons, the travel restrictions have produced an acute dilemma for Sergeant Lazo. He is very proud of his service in the U.S. army and worried that, if he were to violate the travel ban, he might jeopardize his military career. “I always believe in doing my duty,” he said at a public gathering in Washington, D.C. “I did my duty in Iraq, even when it meant I could lose my life. But I think I also need to do my duty as a father.”140

Milay Torres

Milay Torres, age seventeen, migrated to the United States in 2000 to live with her father, leaving behind her mother, siblings, cousins, grandparents, and uncles in Cuba. It was three years before her father was able to save enough money for her to return to the island for a very emotional visit in 2003. And she told Human Rights Watch that she was “very excited” about returning again during her summer vacation in 2004.141

News of the new travel restrictions came as a major blow to her. When she found out she would not be able to travel, she says, she became “very depressed and turned rebellious and stopped going to school.”142

The impact on her mother appears to have been even more severe. Mirladi Arias, forty, who suffers from diabetes and a nervous condition, told Human Rights Watch that her inability to see her daughter has had a profound impact on her psychologically.

After she left Cuba, I began suffering more anxiety attacks. After I found out [about the travel restrictions] my anxiety worsened. I am seeing psychologists and psychiatrists, and when I get these attacks, I go to the hospital and they inject me with some sedatives and send me home. … What happens to me with these nervous crises is that I get really sad and I start screaming and crying and I break the things that I am holding in my hands … When I see the things that are happening there, with the traveling restrictions … my condition worsens, because I am waiting for her to come, but she doesn’t come. … Sometimes I tell people that I would give up my life to be able to see my daughter for just five minutes.143

Amparo Alvarez

“Amparo Alvarez,” age sixty-nine, migrated to the United States in 1993 seeking medical treatment that was unavailable to her in Cuba. She eventually became a citizen, retired, and currently receives disability payments from the government. She is distressed that she will no longer be able to visit her daughter and grandchildren, as she had been doing once a year before the new restrictions went into effect.144

One reason she wants to travel now is to help her forty-one-year-old daughter, who has been told she needs a hysterectomy as soon as possible, but has no one to take care of her two children while she is hospitalized and recovering.

A second reason is that she herself is in very poor health, suffering from high blood pressure, degenerative osteoarthritis, and serious kidney problems that may require surgery. She believes that visiting her family can help give her the emotional strength to face her illnesses. “It’s like a very sick person who gets a blood transfusion and, as a result, comes back to life. That is what it’s like for me, seeing her, it’s as if they injected me with life.”145

But she is afraid that she may not live to see her family again. Since her last visit was in May 2004, she will have to wait until 2007 to obtain permission to travel again. “I am seventy years old already,” she told Human Rights Watch. “I am already ‘due’ like they say. My priority now is to see my daughter. … I don’t have much time left, so I have to do everything possible to see her.”146

Despite her desire to travel, she says she is unwilling to circumvent the travel restrictions. “I don’t like doing anything illegal. I have always respected the laws of this country.” But she conceded that she felt torn between her obligation to her family and her obligation as a law-abiding citizen of the United States:

I am very grateful to this country. This country gave me refuge, I worked and I was able to retire and have the disability and that is something one is grateful for. But I feel extremely affected, because what I want the most is to be able to see my daughter and my two grandsons. 147

Nohelia Guerrero

“Nohelia Guerrero,” age forty-six, a businesswoman, left Cuba in 1992, and had returned three times before the restrictions were imposed, the last visit in June 2004. Her sixty-five-year-old mother has advanced Alzheimer’s disease and needs around-the-clock care. Guerrero pays a nurse to take care of her. When her mother was hospitalized in February 2005, she decided to visit her, circumventing the travel restrictions by traveling via a third country.148

Under the new restrictions on remittances, Guerrero reported, she cannot send enough cash to cover the cost of her mother’s most basic needs: food, diapers, and the nurse’s wages. In the past it was easy to send cash with friends and acquaintances that were traveling, but now fewer are traveling. A collateral effect of the restrictions has been to force courier companies to raise their rates (by 50 percent in the company she regularly used) as the companies themselves have more difficulty finding people they can pay to carry packages.

The restrictions have hurt her on several levels, she told Human Rights Watch. One is emotional: “Not being able to visit a mother who is dying affects me daily because you feel helpless.”149

The restrictions have also hurt her financially. “I’m losing lots of money,” she said. When she traveled to visit her hospitalized mother, the airfare was much more expensive than it would have been flying directly to Cuba, she said, “and this means less money for my family.”150 Moreover, she added, “you always have that terrible fear that if they catch you you’ll have to pay” a fine.151

A third way the travel restrictions affected her, she says, is by putting her in a situation where she felt compelled to break the law. “I have never had problems with the law. And I have great respect for the American laws. But I have had to break the law because of a humanitarian problem—my mother.”152

Finally, the restrictions have provoked in her a sense of betrayal by the adopted country whose values she had embraced. “I came to this country for the freedom,” she said, “and now they are taking it away from me.”153

The Impact of U.S. Travel Restrictions

Family Separation

In defending the new travel restrictions, the Bush administration has disregarded the importance that many Cubans attach to their visits to their families in Cuba. Deputy Assistant Secretary of Western Hemisphere Affairs Dan Fisk has stated, for example, that prior to the new restrictions, “Cubans had, in effect, established a commuter relationship with the island—living and working part-time here and living and vacationing part-time there—all the while serving as conduits of hard currency to the regime.”154

The right to return to one’s home country is not contingent upon the purpose of the travel, so the fact that many Cubans may indeed be merely “vacationing” in Cuba is largely irrelevant. But as the seven cases above illustrate, that right serves to protect much more than travel for pleasure. It can also be crucial for allowing migrants to maintain their connection with some of the people they most value in their lives—their families.

It is undoubtedly true that many Cubans, including some of the ones we interviewed, traveled regularly to Cuba for holidays and special occasions. “Saray Gómez,” for instance, a sixty-two-year-old school teacher who left Cuba in 1970, traveled to Cuba three times a year—for her father’s birthday in March, her mother’s birthday in August, and at Christmastime. Yet she and several of the Cubans we interviewed bristled at the suggestion that they traveled to Cuba simply for pleasure. “My family is the most important thing to me,” she said.155

“I don’t go to Cuba to vacation,” insisted “Isabella González,” age seventy-six, who used to visit Cuba once a year until the new regulations went into effect. “I go because I have to see my sisters. The family is the most important thing you have.” In the end, she said, “it is the only thing you have.”156

While many of the people interviewed stressed their opposition to the Cuban government, they also insisted that their political views had no bearing on their family ties. “Gregorio Torres,” who left behind his parents, siblings, and two children when he migrated in 2000 with his wife and stepdaughter, told Human Rights Watch: “You can oppose the regime, the policies. But you’re never going to oppose your family.”157

Family Illness

Family-related travel becomes particularly important when there are family members in Cuba whose health is failing. The previous regulations recognized this fact by allowing Cubans to obtain special licenses to visit family in Cuba for “humanitarian” reasons. The current regulations eliminate this exception.

The Bush administration has insisted that Cubans will still be able to visit their ailing relatives, only less frequently. “An individual can decide when they want to travel once every three years and the decision is up to them,” Fisk has said. “So if they have a dying relative, they have to figure out when they want to travel.”158

But this option is entirely inadequate for people with relatives in poor health, and even worse for those with multiple family members who are ailing. Saray Gómez, for example, visited her family before her father died in January 2004, and as a result is now restricted from visiting her mother who is also seriously ill.159

Nor is it an option for many of the people we interviewed who have traveled last year and therefore must wait until 2007. “Nelson Espinoza,” for example, said, “I can’t wait three years to see my sister, who is in a very delicate condition, because I don’t know what’s going to happen.”160 Similarly, “Lorena Vasquez,” who visited Cuba in 2004, is anxious about her sister who has cancer. “It’s likely I won’t see her again,” Lorena Vasquez said. “She won’t last three years.”161

Moreover, the issue for many is not so much saying goodbye to a family member as helping that person to live. One central purpose of the family visits, as we saw in the case of Marisela Romero, is to bring money and medical supplies. While individuals can still send remittances and supplies through couriers, a collateral effect of the travel restrictions, according to several people, is that it is now more difficult to do so. “Sandra Sanchez,” has been sending medicine to her father, who has cancer, every month, but she finds that it takes longer to arrive because the number of people traveling has decreased.162

Similarly, Ivonne Acanda, who has been sending medicine to relatives for several years, reports that the courier company she used in the past was compelled to shut down because of the travel restrictions. “I don’t know now anybody that goes to Cuba, and one can’t risk sending these medicines that are so important with someone one doesn’t know very well.” In October 2004 she did in fact send medicines with a woman who was making the trip.

I took the risk with that lady, and thank god she behaved really well and brought the medicines directly to my nephew’s door. But in other occasions, you can find people who won’t do you the favor and it is difficult to ask someone that you don’t know to bring the medicines to Cuba.163

Maria Lemos with her ailing mother.

“Each time I go there is like giving her an injection of happiness,” she said.

“It makes her want to keep living.”

© 2002 Private

Even where it is possible to send cash and medical supplies, several people stressed that caring for a sick relative involves more than covering the costs of care. María Lemos, for example, has been helping care for her eighty-four-year-old mother in Cuba who is in very poor health and chronic pain, confined to a wheelchair, with an ulcer and severe arthritis. Before the restrictions, she used to visit her once or twice a year, but since her last visit was in May 2004, she is prohibited from traveling again until 2007. She is still able to send money and medicine to Cuba. But she is convinced that her mother needs more than that to endure her ailments.

They say it doesn’t really matter [if you can’t travel] because you can still send medicine and money. But it’s not just about money and medicine, it’s also being able to touch her, and see her. In other words, [it’s] the human warmth. Each time I go there is like giving her an injection of happiness. It makes her want to keep living.164

Similarly, Saray Gómez reports being told by a psychiatrist who is treating her mother for a nervous condition that she should visit as often as possible, as her mother’s condition worsens when she is not around.165

According to Arlene García, her frequent trips to Cuba prior to the restrictions were critically important for her sister and brother-in-law, who are alone caring for a father who is battling cancer and an aunt who was left partially paralyzed by a stroke: “When I go it is the only time they have vacation,” García said, adding that her trips were even more critical for her ailing relatives. “It is the best medicine that they get. It’s amazing how the presence of a person can sometimes reduce the problems that they have even if it is just for a little bit.”166

While Cubans in the United States can still communicate directly with relatives in Cuba by telephone, calls to Cuba are exceedingly expensive (because of the embargo), and do not compensate for the lack of direct human touch. Sometimes communication by telephone is not even an option. “Johana Suarez,” age sixty-four, had been traveling to the island every year at Christmastime to see her mother, who is eighty-eight, sick, and alone. Unable to travel because of the restrictions, she tried calling her mother on Christmas in 2004. But her mother’s ability to speak had by then deteriorated to such a degree that when she got her on the phone and said “It’s me, your daughter,” there was complete silence on the other line.167

The visits can also provide a critical respite for relatives in Cuba who are taking care of an illness, as in the case of Marisela Romero and Andrés Andrade above. Santiago Hernández, for example, is anxious to provide a break for his sixty-six-year-old sister who is caring for their ninety-six-year-old mother in Cuba. The mother has cancer and his sister is exhausted from bearing the full responsibility of taking care of her, he says. There are currently no other relatives in Cuba who can help her.168

“Cecilia Espinoza,” seventy-four, who lives in Cuba and suffers from diabetes, expressed her dismay that her brother in Miami would not be able to visit her until 2007:

My other brother died already. My husband also died. I don’t have any children, or uncles or aunts. I am alone. [The travel restrictions] have affected me because there are no medicines here. I can hardly see anymore. My legs hurt. When he [used to visit]…, he would buy things for the house, he would take me out to eat, he would buy me clothes, shoes, and he would leave me money. But not anymore. Now he is unable to come. I am alone, and who is going to help me? I have no hope.169

Redefining the Family

For those with no relatives who fit the definition of “immediate family,” traveling is not an option. The administration has defended this restriction by trivializing its impact. “[W]hat are we supposed to say to them?” As already noted, Roger Noriega, while serving as assistant secretary of state for western hemisphere affairs, told one reporter. “We’re going to continue to allow this money to be shoveled into the coffers of a regime that’s going to keep them in chains under a dictatorship because we want to preserve the right of people to visit their aunts?”170

But for many people Human Rights Watch spoke with the impact could be quite significant. Saray Gómez, for example, is concerned that, should her ailing mother die, she will then not be able to obtain permission to visit her seventy-five-year-old aunt, who is also in very poor health. “Apparently for [President Bush], aunts and uncles are not family,” she said. “[But] I love her as though she were my mother. She helped raise me. She didn’t have kids. We were her kids.”171

Several other people also reported that their aunts or uncles had played such a central part in their upbringing that they were, in fact, like parents to them. For example, Luisa Rimblás, age fifty-seven, who left Cuba in 1970, had been making yearly trips to Cuba to visit her ailing mother and six aunts, who she says raised her, since her mother worked as a teacher in the countryside and was often away from home. Rimblás worries that should her mother die, she will not be permitted to visit her aunts. “It’s not fair that they tell me that I can’t go to see my aunts, who are like mothers to me … that they tell me that my aunts are not important.”172

“Mario Fuentes,” age sixty-two, who left Cuba in 1971, lost his great-uncle in January 2005, a man who he says was like a father to his own mother, raising her after she was orphaned. “And for me he was like a father or a grandfather, the person I admired more than anyone.”173

The ties with uncles and aunts can become particularly important for people after their own parents die. “Irene Espinoza,” age thirty-two, who lives in Cuba and lost her father to cancer in September 2003 and her mother in 2000, described how important it was for her to see her uncle, who cannot travel to Cuba until 2007. “Imagine, first my mom dies and then after my dad dies. And I have a daughter and I am a single parent. And he is my uncle, which is to say like my dad, the one that looks after my aunt and me. I really need his support.”174

In addition to aunts and uncles, others told us of close relatives who did not qualify as “immediate family” under the new restrictions. Ignacio Menéndez, age fifty-five, came to the United States on the 1980 Mariel boatlift, with his wife, who was forced to leave behind three children from her first marriage because their father prevented them from leaving. Menéndez says he was very close to the three children and that they see him as their “true father.” Since the 1990s, he and his wife have visited them in Cuba once a year, but they will not be able to engage in family-related travel again until 2007. He is especially concerned about his thirty-three-year-old stepdaughter who was diagnosed with lymphoma last year and whose recovery, after four operations, is far from guaranteed.175

Ivonne Acanda no longer has any relatives in Cuba who fit the Bush administration’s definition of “immediate family,” but she does have numerous uncles, cousins, and nephews, as well as relatives of her husband, whom she considers part of her family. One of them is her husband’s nephew, now in his mid-20s, who was run over by a train in 2002, losing one leg and badly damaging the other. Since the accident she has traveled to Cuba three times, bringing him medicine, and she has sent medicine through couriers when she could not travel herself. She is anxious now to travel so that she can bring him a wheelchair and to visit the other relatives who are not part of her “immediate family,” because, she says, “blood is something that pulls you.”176

Divided Loyalties

Faced with these restrictions, many Cubans have felt compelled to break the law, either by providing false information to obtain a special license for travel, or by traveling via a third country and not reporting the trip. One means of circumventing the restrictions reportedly has been by signing up with churches that have special licenses as religious organizations. These licenses are meant for religious delegations doing church-related work in Cuba. However, several people we spoke with said the churches had, for a considerable fee, allowed them to sign up for delegations and then spend their time in Cuba with their families.

Falsely declaring themselves members of a church may have caused these individuals some discomfort, but they felt that the need to see family members justified it. Saray Gómez, for example, a former Catholic youth leader in Cuba, signed up with a Santería delegation after her father had a heart attack in December.177 (Ironically, Gómez abandoned the island in 1970, in part, she says, because the government had not allowed her to practice her religion.)

Many others told Human Rights Watch that they were unwilling to violate the restrictions. Jorge Rodríguez, age forty-six, for example, who is anxious to visit his aging mother and a sister who had been hospitalized with a serious illness, refuses to consider traveling with a fraudulently obtained religious license. “I love this country,” he said. “I have been in this country for twenty-six years. I have two daughters who were born here … And I don’t want any problems with the law in this country.”178

Isabella González expressed a similar mix of respect for U.S. law and fear of the consequences of violating it. Before the new restrictions, she used to visit Cuba once a year and is anxious now to see her sister and step-sister, both of whom are gravely ill, but not if it means doing something illegal.

I am American and I love this country. I respect the laws of this country. And I thank God and this country for everything I have had, for the opportunity to work and receive disability [payments]. I want to see my sisters above all because they are in very poor health. But I don’t want to lose what I have here.179

Others felt similarly torn between their obligation to their families and their obligation as citizens. María Lemos, for example, said she is unwilling to circumvent the restrictions, explaining that she “had never done anything outside the law and didn’t want to do it.” But she says that the fact that she can’t visit her mother until 2007 has had a major impact on her emotionally. “Just thinking about it makes me want to cry,” she said. “I have a mom who is sick and old and I don’t know what could happen in three years … I don’t understand why, because of political problems between governments, I can’t go to see my mom.”180

Ignacio Menéndez summarized his internal conflict this way: “We are citizens of the United States and we need to follow the law. But I have a right to visit Cuba. Cuba is my country. My mother country.”181

Curtailed Freedom

As with the embargo, the Bush administration justifies the travel restrictions as a response to Castro’s human rights record. “To the individuals it may not seem fair,” then-Assistant Secretary Noriega has said. “But the problem of the Cuban situation is not that families are divided. The problem is that half the family lives in a dictatorship.”182

Many of the people interviewed for this report share the administration’s critical view of Castro’s human rights record. Some said that they, themselves, had been victims of political persecution in Cuba. A few even endorsed the embargo. But all opposed the restrictions on family travel. And, in fact, several said it reminded them precisely of the sort of policy that they hoped to escape when they migrated.

“We also hate the Cuban government,” said Alejandro López, a forty-one-year-old artist who had once been threatened with jail time because a work of his was misinterpreted by authorities as being religious. “I’m here because I want to be free. But now the U.S. government wants to treat me the way the Cuban government would.”183

“I would understand that [a policy like] this could happen in Cuba,” said Beatriz Niz Gallardo, who left Cuba in 1983, “but not here in the most democratic country in the world.”184

Lourdes Arteaga, who left Cuba in large part because she “was tired of the repression,” said: “Here they are doing the same thing that Fidel does. Over there you are not allowed to leave, and over here they don’t allow you to go and visit your family.”185

Arlene Garcia

visiting her niece and father, who made a “big sacrifice” sending her out

of Cuba when she was a teenager.

Now he is battling cancer and she is

unable to visit him.

© 2004 Private

For Arlene García, whose father is now battling cancer back in Cuba, the restrictions are a bitter reminder of the sort of policy her parents wanted her to escape when they arranged her emigration as a teenager thirty years ago:

My parents made a big sacrifice sending me, their oldest daughter, out of the country so I could be free. … Now I can’t visit and help the father who made that enormous sacrifice for me. I’m an American citizen now and I think that for our country to have a law like this is shameful.186

After insisting that he would not violate the travel restrictions, Jorge Rodríguez added:

I feel really bad because that was precisely why I came to this country. I left Cuba because I didn’t have any freedom of expression. … I get here and this is a free country, where I have all the freedom to express myself. But I think that they can’t take away one’s right to travel freely, especially when one travels to a country to visit one’s family, and especially when a family member is sick. For a country that proclaims human rights to create restrictions like these is wrong.187

Like Rodríguez, many others questioned what they saw as a double standard on human rights in the administration’s Cuba policy. Saray Gómez, for example, said “I don’t understand how a country that talks about human rights could do something like this.”188

“We came here thinking this was the country of liberty,” said Ignacio Menéndez. “You say you are the country of freedom, the country of human rights, when you are violating the human rights of the Cubans.”189

[97] For a discussion of the embargo’s ineffectiveness and its negative impact on human rights, see “Cuba: Human Rights and U.S. Policy,” Statement by Tom Malinowski, Washington Advocacy Director, Human Rights Watch, before the Senate Committee on Finance, September 4, 2003; “Time to End the U.S. Embargo on Cuba,” Human Rights Watch press release, May 17, 2002, available at: http://hrw.org/english/docs/2002/05/17/cuba3982.htm.

[98] United States v. Laub, 385 U.S. 475 (1967).

[99] Mark P. Sullivan, “Cuba; U.S. Restrictions on Travel and Remittances,” Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, May 10, 2005.

[100] Ibid.

[101] 31 CFR 515.561(d)(2003).

[102] Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba, “Report to the President,” May 2004, p. 38.

[103] Ibid., p. 34.

[104] Ibid., p. 36.

[105] Ibid., p. 38.

[106] 31 CFR 515.561(a).

[107] 31 CFR 515.561(c).

[108] 15 CFR 740.12(a)(2)(v)(A).

[109] 68 CFR 4422 at 4429.

[110] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with director of Miami-based travel agency, Miami, Florida, February 1, 2005.

[111] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Marisela Romero, Miami, Florida, March 9, 2005.

[112] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Marisol Claraco, Havana, Cuba, February 25, 2005.

[113] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Marisela Romero, Miami, Florida, March 9, 2005.

[114] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Marisol Claraco, Havana, Cuba, February 25, 2005.

[115] Ibid.

[116] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Marisela Romero, Miami, Florida, March 9, 2005.

[117] Ibid.

[118] Ibid.

[119] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Andrés Andrade, Union City, New Jersey, February 12, 2005.

[120] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Arelis Andrade, Havana, Cuba, February 29, 2005.

[121] Ibid.

[122] Ibid.

[123] Ibid.

[124] Ibid.

[125] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Andrés Andrade, Union City, New Jersey, February 12, 2005.

[126] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Arelis Andrade, Havana, Cuba, February 29, 2005.

[127] Ibid.

[128] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Leandro Seoane, Miami, March 3, 2005.

[129] Ibid.

[130] Ibid.

[131] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with the mother of Leandro Seoane, Havana, Cuba, March 4, 2005.

[132] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Leandro Seoane, Miami, Florida, March 3, 2005.

[133] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with the mother of Leandro Seoane, Havana, Cuba, March 4, 2005.

[134] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Leandro Seoane, Miami, Florida, March 3, 2005.

[135] Statement by Carlos Lazo, “Cuba Action Day,” Washington, D.C., April 27, 2005; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Carlos Lazo, Seattle, Washington, May 20, 2005.

[136] Carlos Lazo, “Trusted in Iraq, Barred From Cuba,” Los Angeles Times, April 26, 2005.

[137] Ibid.

[138] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Carlos Lazo, Seattle, Washington, May 20, 2005.

[139] Mary Murray, “Cuban teens want to see their U.S. soldier dad,” NBC News, October 25, 2004, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6327065/ (retrieved September 26, 2005).

[140] Statement by Carlos Lazo, “Cuba Action Day,” Washington, D.C., April 27, 2005.

[141] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Milay Torres, Miami, Florida, February 18, 2005.

[142] Ibid.

[143] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Mirladi Arias, Havana, Cuba, March 4, 2005.

[144] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Amparo Alvarez” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 14, 2005.

[145] Ibid.

[146] Ibid.

[147] Ibid.

[148] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Nohelia Guerrero” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 28, 2005.

[149] Ibid.

[150] Ibid.

[151] Ibid.

[152] Ibid.

[153] Ibid.

[154] Michael Braga, “Cuban-American votes aren’t a lock for the GOP this year; It appears some Bush administration policies have backfired,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, October 30, 2004.

[155] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Saray Gómez” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 14, 2005.

[156] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Isabella González” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 4, 2005.

[157] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Gregorio Torres” (not his real name), Miami, Florida, March 2, 2005.

[158] Eliza Barclay, “Analysis: Cuba restrictions delayed,” Washington Times, June 3, 2004.

[159] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Saray Gómez” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 14, 2005

[160] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Nelson Espinoza” (not his real name), Union City, New Jersey, February 23, 2005.

[161] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with”Lorena Vasquez” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 4, 2005.

[162] Human Rights Watch phone interview with “Sandra Sanchez” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 7, 2005

[163] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ivonne Acanda, Union City, New Jersey, February 23, 2005.

[164] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with María Lemos, Miami, Florida, February 18, 2005.

[165] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with ”Saray Gómez” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 14, 2005

[166] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Arlene García, Miami, Florida, May 12, 2005.

[167] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Johana Suarez” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, January 31, 2005.

[168] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Santiago Hernández, Miami, Florida, January 26, 2005.

[169] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Cecilia Espinoza” (not her real name), Havana, Cuba, March 4, 2005.

[170] Dateline NBC, August 1, 2004.

[171] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Saray Gómez” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 14, 2005.

[172] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Luisa Rimblás, Miami, Florida, February 14, 2005.

[173] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Mario Fuentes” (not his real name), Miami, Florida, January 25, 2005.

[174] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Irene Espinoza” (not her real name), Havana, Cuba, March 4, 2005.

[175] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ignacio Menéndez, Miami, Florida, February 4, 2005.

[176] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ivonne Acanda, Union City, New Jersey, February 23, 2005.

[177] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Saray Gómez” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 14, 2005

[178] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Jorge Rodríguez, Hollywood, Florida, February 25, 2005.

[179] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with “Isabella González” (not her real name), Miami, Florida, February 4, 2005.

[180] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with María Lemos, Miami, Florida, February 18, 2005.

[181] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ignacio Menéndez, Miami, Florida, February 4, 2005.

[182] Dateline NBC, August 1, 2004.

[183] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Alejandro López, New York, New York, February 2, 2005

[184] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Beatriz Niz Gallardo, Miami, Florida, March 4, 2005.

[185] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Lourdes Arteaga, February 16, 2005.

[186] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Arlene García, Miami, September 19, 2005.

[187] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Jorge Rodríguez, Hollywood, Florida, February 25, 2005.

[188] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Saray Gómez (not her real name), Miami, February 14, 2005

[189] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ignacio Menéndez, Miami, February 4, 2005.

| <<previous | index | next>> | October 2005 |