- Arrests of Protesters

- Targeting of Protest Leaders

- Abuse of the Indian Penal Code

Key Individuals Named in this Report

I. Summary and Recommendations

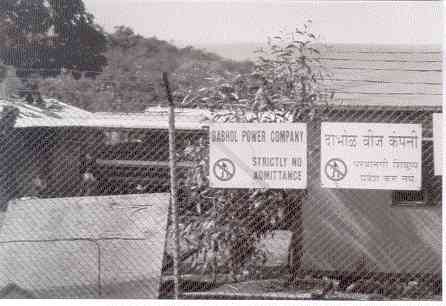

II. Background: New Delhi and Bombay

III. Background to the Protests: Ratnagiri District

IV. Legal Restrictions Used to Suppress Opposition to the Dabhol Power Project

V. Ratnagiri: Violations of Human Rights 1997VII. Complicity: The Dabhol Power Corporation

VIII. Responsibility: Financing Institutions and the Government of the United States

Appendix A: Correspondence Between Human Rights Watch and the Export-Import Bank of the United States

Appendix B: Report of the Cabinet Sub-Committee to Review the Dabhol Power Project

Appendix D: Correspondence Between the Government of India and the World Bank

As noted above, police have abused the Indian Penal Code to falsely charge villagers opposed to the Dabhol Power project with offences ranging from unlawful assembly to attempted murder in the cases of the April 1 attack in Katalwadi village. Cases investigated by Human Rights Watch and Indian human rights organizations reveal a consistent pattern of bias by police which is exhibited when DPC contractors’ property is damaged or when disputes arise between DPC contractors (who support the power project) and opponents of the Dabhol Power project. When damage occurs to the property of DPC contractors police vigorously pursue opponents of the project as primary suspects, irrespective of the facts. When a confrontation between contractors and villagers occurs, police retaliateagainst the villagers. When contractors threaten or attack individuals or their property, police refuse to investigate complaints or else file charges against the plaintiffs. Retaliation has included arbitrary arrests, beatings, and illegal detention of juveniles.

Regarding property damage

On December 17, 1996, at approximately 7:00 p.m., police arrested Mahadev Pandurang Solkar, Pradeep Satley, Laxman Satley, and Shankar Vane relative to the destruction of two vehicles owned by DPC contractors the day before. The police took them to Guhagar police station, approximately five kilometers away. Later, police charged the men with destruction of the vehicles and rioting.178

Initially, the police did not tell the men or other villagers that they were being arrested, rather that they were being taken for questioning. At the station, their names, addresses, occupations, and work addresses were recorded by the police, then they were asked whether they knew anything about the incident or who did it—which they did not. Police then informed them that they had been arrested because of the truck burnings and put them in jail.

While they were in custody, around twenty-five men and women from their hamlet came to the station and told the police that the jailed people were innocent and that no one in the hamlet knew about the incident. But the police would not listen to them. Then villagers started asking the police how they could hold a man who has just had an operation (Laxman Satley) and told them that if anything happened to him, the police would be held responsible. According to Mahadev Solkar, women in the group started telling the police that “if you are not prepared to release those men, than you should arrest us too, because we are just as innocent as they are.” In response, the police told villagers that the men would be produced before the court and whatever the court decided would stand. Nevertheless, the police released Laxman Satley that night.

After Satley was released, the crowd dispersed and returned to the village. The other men spent the night in jail. According to Mahadev Solkar, they were kept in a very dark, small cell and no beds, blankets, or food were provided to them until around 9:00-10:00 the next morning.

On February 19, the men were taken to the judicial magistrate in Chiplun and later released on 1,000 rupees bail each. The Guhagar police told the men that they would have to report to the police station every other day for a month. Police told Solkar that he would be arrested if he did not report to the police station. Forthe next month, Solkar went to the police station and signed a register as proof of his appearance.

After eight days, the police charged the men with rioting, rioting with a deadly weapon, unlawful assembly, causing hurt, causing hurt with a deadly weapon, reckless endangerment, wrongful restraint, and arson under the Indian Penal Code.179 They were going to be rearrested, so their lawyer came to the police station and then went to the tehisildar (the senior government official at the taluka level) and arranged for the defendants to produce their house ownership papers to the tehisildar, which in effect, made their houses a bail bond.

Solkar told us his opinion of the incident:

The police arrest people in local communities to harass and demoralize them from agitating against Enron. The police keep tabs on villages and hamlets against the project. Whenever something happens that warrants arrest, these villages are targeted.

Mentally, this whole event has put me completely off balance. It has affected my job, because every time there is a court date, I have to go to Chiplun, which is six hours away and costs 300 to 400 rupees per trip. Earlier the lawyers would take care of it, but now I have to go in person. My finances are affected: I lost work for a month when I had to report to the police station and have lost work for subsequent trips. I am maintaining my innocence, but one never knows. Before this I had never even been to a police station or the courts. Personally, it has cost us 10,000 rupees a person so far, and my monthly salary is only about 3,500 to 4,000 rupees.180

The charges filed against the men carry a maximum sentence of up to seven years’ imprisonment. The case came up for hearing on January 5, 1998 and was adjourned until March 1998. As of October 1998, the case was still pending.

Dattaram Jangli, who has also been subjected to externment orders for his participation in protests against the Dabhol Power project, and other villagers were arrested relative to damage to the vehicles of DPC contractors on June 14, 1996,while they attended a village meeting to discuss cleaning a community pond so that it could be used for drinking and other purposes.

While the meeting was going on, Assistant Sub-Inspector P.G. Satoshe arrived, accompanied by seventeen police officers who surrounded the community hall. According to Jangli:

Satoshe asked people who the village leaders were. He said that senior police officials from Ratnagiri have come to discuss something. When we asked them what this was in regard to, Satoshe said, “You will know when you meet the officials.”181

Because the police did not specify their reasons for summoning these people, the villagers refused to go meet with them. The police then arrested fifteen villagers and transported them to the Guhagar police station, where their names, addresses, addictions/vices, fingerprints, and any identifiable body marks were recorded.

A few hours later, around 11:00 a.m., the detained villagers were taken to Chiplun and presented to the judicial magistrate, who released them on personal bonds. The cases, however, are pending and villagers are still unclear about the charges leveled against them. Later, they learned that they were charged with vandalizing the vehicle of an Enron contractor. Jangli told us:

The police are only out to harass us in some way or another, so that we stop our opposition to Enron. But we have lost everything. Everything other than our houses has been taken away. We already face a shortage of fuelwood and green material to fertilize our fields.182

Regarding disputes with DPC contractors and police

The biased use of the Indian Penal Code further exacerbates existing tensions between villagers opposed to the Dabhol Power project and those who support it. The tensions, however, began with the types of activities the company engaged in to foster support for the project—such as awarding labor contracts and giving development funding to individuals to create their own nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

In the December 11, 1997 issue of the Far Eastern Economic Review, an article described Enron’s management of local opposition to the project. The article, quoting the chief executive officer of the Enron Power Development Corporation, Rebecca Mark, stated:

Enron worked to defuse accusations that the company deprived locals of land, and headed off the formation of a powerful lobby against it. It did so in part by involving locals in community activities meant to help people adversely affected by the project, even giving jobs to some. Mark denies the company bought off local people for the sake of peace. “There are always ways to include people, to make them productive when they could be counterproductive. That’s not corruption, that’s economic interest.”183

According to the Center for Holistic Studies, this process began in late 1994 when Sanjeev Khandekar, the Dabhol Power Corporation’s vice president for community relations, began to offer opponents of the project labor contracts and development funding. A letter to Enron, written by the Center for Holistic Studies, detailed the situation:

Before the arrival of DPC in the region, there was only one organization engaged in some social work in the area, and that was Shramik Sahayog. It has always been opposed to the project. Others were formed with the efforts of DPC Vice President for Community Relations, Sanjeev Khandekar. According to the villagers, the NGOs are fronts for the Company’s handful of supporters in every village.184

Sadanand Pawar told Human Rights Watch that from March through May 1997, he was repeatedly offered contracts by Sanjeev Khandekar, individual contractors, and even a local member of the Legislative Assembly (who had a contract of his own with DPC, a clear conflict of interest) as an inducement to stop demonstrating against the project. Pawar said:

[Sanjeev] Khandekar offered us contracts. I would get messages sent through contractors. They repeatedly offered me contracts throughout 1996-1997. They would call me and say, “Take a contract, give work orders, and give up the agitation...” Throughout the agitation, they constantly offered me contracts. One person, Vaishali Patil, was asked by Circle Inspector Desmukh to stop protesting and to take a contract. He [said he] would go with her to Khandekar’s and get a contract. This is how people defected... In December 1997, one man, a local Congress MLA [Member of the Legislative Assembly], approached me and said that if I go to Sanjeev Khandekar and take contracts, I will get whatever I want and he will give me contracts. DPC told people that “whoever brings those people in [leaders of the DPC protests] will get contracts.”185

Pawar also cited Vinay Natu, a BJP MLA as one who took DPC contracts following alleged prompting by the BJP to stop protesting once the project was renegotiated.

According to Pawar and others, the flip-side of contract offers was strong-arm tactics. Pawar told Human Rights Watch:

When we refused [to accept contracts], the police started their crackdown. Starting in March 1997, whenever there was a police crackdown, four people, including a local MLA would say “Give up the agitation, take a contract, whatever you want we’ll give you. If you don’t listen, you will face the consequences.”

Any person who honestly opposed the project was destined for jail... They [the police] never harassed contractors, only local workers...Whenever the agitation was in full swing, one leader would defect. For example, Vinay Natu, a BJP MLA, Sushil Velhal, and others would defect and take DPC contracts. Because the BJP controlled them, they could be manipulated. These people were never harassed by the police.186

Sushil Velhal, a member of the BJP and a former participant in demonstrations against the project, was one person many individuals cited as anexample of the relationship between the company and its contractors. Velhal received contracts as well as development funds from DPC. According to Mangesh Chavan:

They [DPC] have “fronted” what are local NGOs/contractors who have dubious records as their public examples of community development and working with NGOs... Velhal was boycotted by the local community, he was a known bootlegger and smuggler. Following the Bombay blasts, he was arrested under TADA.187 He was alleged to have smuggled the RDX [explosives] used in the blasts into the country. All his associates are in jail, and he was heavily surveilled by Customs because of his smuggling activities. In 1995, he started the Guhagar Parishad Vikas Manch, an NGO that he used as a front for his contracting (and possibly illicit activities). Enron associated with him to show they were working with NGOs and had community support; they gave him an ambulance to show they were involved in “community development.” Enron gave him other civil contracts as well.188

Reputational issues notwithstanding, publications issued by the Dabhol Power Corporation and newspaper reports confirm what many people reported—that Velhal associated with senior officials of the Dabhol Power Corporation and was portrayed as an NGO working with the company. In one case he was photographed with Sanjiv Khandekar, a vice president of DPC, as they inaugurated the Guhagar-Khandwadi bus service.189 The company also reported that it supported medical check-ups for women on April 27, 1997, which were co-sponsored by the Guhagar Parisar Vikas Manch, Velhal’s NGO.190

This sort of partnership carries risks, however. On December 9, 1997, Velhal and others stopped Khandekar’s car as he was on his way to attend a concert and attacked him. Khandekar told The Indian Express that the attack was prompted byhis refusal to award a contract to Velhal.191 In a letter to the Enron Corporation, the Center for Holistic Studies detailed the incident and Velhal’s alleged background:

The DPC Vice-President [Sanjeev Khandekar], his secretary, and the Project Development Officer were badly beaten and their faces blackened by one such “social worker,” Sushil Velhal, who heads a DPC-promoted NGO, Guhagar Parisar Vikas Manch... The NGO was formed in late 1994 after Velhal officially announced that he was quitting the anti-Enron agitation and joining hands with DPC. This was after the land acquisition was completed and DPC was desperate to cultivate elements who would support the project in Guhagar taluka, attract people from far away villages to join as laborers and make DPC look more respectable.192

Velhal’s assault on Khandekar is unique for two reasons: it is the only known case of a contractor attacking a DPC representative, and it is the only case in which a contractor has, to our knowledge, been prosecuted for a criminal assault.

Criminal activity, however, was not unique to Velhal. In fact, in a series of incidents going back to 1996, contractors have threatened or assaulted villagers opposed to the project, or damaged their property. The police, in turn, refused to entertain complaints by the victims. Similarly, following disputes between contractors and villagers, police arrested, beat, and detained villagers in retaliation.

For example, on November 22, 1996, police at the Guhagar police station refused to accept the complaint of Sushant Sudhakar Bhatkar. Bhatkar was allegedly assaulted by Sandesh Pundalik Kalgutkar, a local contractor for the Dabhol Power Corporation. According to Bhatkar, on November 22 Kalgutkar left the DPC site, took a sword from his van, and attacked Bhatkar, Sakharam Misal, and Anil Narayan. Bhatkar was injured and, when he lodged a complaint, police told him that the sub-inspector was unavailable to accept the complaint. Thus, they never filed it.193

On February 27, 1997, police refused to accept the complaint of Adinath Kaljunkar, a participant in protests from the village of Aareygon who had been arrested the previous month under Section 151 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. Kaljunkar telephoned the Guhagar police station on the evening of February 27 and alleged that Deepak Kangutkar, a contractor for DPC, and four other men had threatened to murder him. Kangutkar and the others were DPC contractors and, according to Kaljunkar, believed they would suffer financial losses if the protests continued. The officer refused to send anyone to investigate the complaint. The next morning, February 28, Kaljunkar went to the police station to complain in person. The officer on duty determined that the matter did not warrant further investigation.194

Sadanand Pawar received anonymous death threats over the telephone throughout 1997 and early 1998. The caller or callers ordered him to cease his opposition to the Dabhol Power project or face the consequences. Pawar told Human Rights Watch:

I got threats. Even in December 1997, I got a phone call and an unknown person said “Give up the anti-Enron agitation or you will be killed.” This happened around 11:00 p.m. It came from Bombay or outside because the long distance ring is different than the local ring. Before, on three separate occasions, in October [1997], when I was not around, my wife received similar calls.195

Pawar told us that he continued to receive anonymous death threats over the phone in the first two months of 1998.196

Katalwadi Village: April 1997

A particularly serious attack occurred in the village of Katalwadi, where supporters of the company assaulted villagers who were opposed to the project on April 1, 1997. Following the attack, the police arrested and charged the anti-Enron villagers with criminal offenses, including attempted murder, under the Indian Penal Code. The perpetrators of the attack, however, were detained only briefly the following day and were not charged with assault. The details of the case are provided below, as they offer a portrait of tensions at the village level.

The village of Katalwadi is at the forefront of protests against the Dabhol Power project and, according to Anand Arjun Bhuvad, a shop owner and recognized village leader, “Ninety-nine percent of the village is against the project.”197 S.D. Khare, who has been closely involved in the issue and has helped villagers with their legal proceedings due to arrests, told Human Rights Watch, “Kathalwadi has about 225 houses, and only seven houses out of 225 are pro-Enron. Their leader is Mr. Dilip Bane. He is appointed as a labor contractor to Enron.”198 Villagers and other observers told us that the company had “cultivated” these families in order to show that the project had support in surrounding villages.199

In response to the activities of Bane and other pro-Enron villagers, and as a sign of community solidarity, the anti-Enron villagers ostracized them by initiating a “social boycott.” That is, the pro-Enron villagers were excluded from the major decision-making of the village, prohibited from participating in village-level festivals and ceremonies, and generally excluded from community activities.

The conflict came to a violent climax on April 1, 1997, during the last two days of the Holi festival. The annual festival is celebrated over fifteen to twenty days and, according to village custom, a statue representing the village goddess, Uttararaaj Kaleshwari, is paraded around the village followed by a procession of residents. Devotees lift the goddess and dance with her. In 1997, villagers who were Enron supporters had been banned from participation in the festival as part of the social boycott.

At approximately 6:00 p.m., six of the Enron supporters led by Dilip Bane and his brother Ashok Bane intercepted the procession.200 They were armed with swords, sharpened hoes (colloquially known as “choppers”), wooden sticks, acid-bulbs, and soda bottles. Acid-bulbs are light bulbs or glass bottles filled with acid which are thrown at people in order to inflict burns and cuts from the broken glass; soda-bottles serve the same function when they are shaken and thrown: the force caused by the carbonated liquid creates an explosion of glass when the bottle strikes an object.

The armed men insisted they be allowed to dance with the deity. Villagers refused because of the social boycott. Ashok Padyal told us:

They knew fully well that situation was not possible because of the social boycott imposed on them by the entire village because they support Enron. People... said that if they still wanted to participate, they should ask the whole village and let it be a collective decision on whether they could participate.201

Following the exchange, the Banes and their associates attacked two of the villagers, Ashok Padyal and his uncle Harishchandra Devale, with their weapons. Padyal told us:

They knew the village would not allow them to comply, so they started attacking people. When the talking stopped, Ashok, Dilip, and Chandrakant Bane came forward and signaled the others to approach.202

The men began by beating Ashok Padyal’s uncle, Harishchandra Devale, with bamboo sticks and knocking him to the ground. Then Ashok Bane took a swing at Devale with a sword, missing him. At this point, Ashok Padyal intervened. The missed sword blow at Devale hit Padyal on the neck and elbow. Padyal fell downand was then beaten with bamboo sticks. The assailants went to Devale’s house and returned with more acid-bulbs and soda bottles which they threw at villagers in the procession.203 According to Padyal:

The distance from where I was beaten to Bane’s house is about fifty meters. People started chasing them [the assailants] and then they started throwing soda bottles and acid-bulbs at those in pursuit. The ground is hard, so the impact of soda bottles and acid-bulbs is explosive. This kept people from chasing them. It caused injuries to women, primarily their legs and burned saris. Because they were wearing saris, it was harder for them to avoid the explosions. Lata Pate, Kunda Bane, Rukmini Bagwe, and another woman were injured. I was writhing in pain at the time.204

After the attack, as another villager, Anand Arjun Bhuvad, described it:

The villagers gathered, and the Enron supporters ran into the forest. While they fled, they threw soda-water bottles at people. They also threw acid-bulbs. There were a few injuries for those chasing them. They escaped, though, through the forest to Enron’s fuel jetty complex and Konvel.205

In anticipation of another attack, some of the residents moved their families into the center of the village. Later, people apprehended another pro-Enron villager, Shankar Bhuvad, an elderly resident whose family was subject to the social boycott. Although his entire family was at home and he did not participate in the attack, villagers yelled and pushed him. Bhuvad told us that he protested to the hostile villagers that the perpetrators knew he would not have approved of the attack, so they had not informed him in advance.206

At the same time, twenty to twenty-five villagers gathered to help Ashok Padyal and his uncle. Padyal was taken home, while his uncle was taken to his residence—about a five-minute walk away. Between 7:30 and 8:00 p.m. their wounds were treated and dressed, and they were given water and tea atRamachandra Bhuvad’s home. They stayed for ten to fifteen minutes and went home. At Ramachandra Bhuvad’s home, senior members of the village discussed how they should respond and decided that they should go to Guhagar government hospital the next morning and tell the police. Padyal told us that, “There was hatred in my mind about those people. I already felt the motive behind the attack was because we are anti-Enron.”207

The next day, Devale and Padyal, along with Padyal’s father, uncle, and cousin, took the 8:00 a.m. bus to Guhagar. The men went to S.D. Khare’s house and drafted a complaint between 8:30 and 11:00 a.m. and took it to the hospital. Padyal required stitches on the elbow and a dressing on the neck.

At around 2:00 p.m., police took Ashok Padyal and his father to the station. His uncle and cousin stayed at the hospital because, according to Padyal, “They thought they may be arrested since the police did not like the anti-Enron members of the village.”208

Meanwhile, in Kathalwadi village, the police came to inquire about the incidents of April 1. But they were not acting on Padyal’s complaint. To the contrary, the police came to investigate a complaint filed by the pro-Enron attackers, who claimed that they had been attacked by anti-Enron villagers. Their complaint listed eighteen people who were known as village leaders and participants in the anti-Dabhol Power project protests. When the police came, they called out the names of eighteen men. Four women who had been injured (by the acid-bulbs) the previous day complained to the police about attack and their subsequent injuries. According to one villager:

[Circle Inspector] Desmukh agreed to take them to the government hospital for an examination. [But] instead of a medical check-up, the women were charged with criminal offences, including attempted murder. They used the incident against Shankar Bhuvad as the reason to charge people with attempted murder. We were taken around noon on April 2 to the Guhagar police station. The four women were put in the lockup as well.209

Once he left the hospital, Padyal went to the Guhagar police station to submit the complaint he had drafted earlier in the day. There he learned that villagers had been arrested and that police were skeptical of his complaint. He told us:

I gave my written complaint to the police, but the police refused to accept it. Instead, they asked me to narrate the whole incident and how it took place, with every minute detail. After the police took the complaint, I was supposed to sign it. When I read it, I saw that the police had taken a “rough sketch” of the incident and most of the crucial details were missing. There was no mention of the soda bottles and acid- bulbs, no mention of injuries to women, and no mention of swords or other weapons.210

Although Padyal was in a great deal of pain because of his injuries, he chose to wait for Circle Inspector Desmukh to amend the complaint.211 While he waited, police lectured Padyal about the project and their opinion of villagers’ opposition, encouraging him to stop protesting. Padyal told us:

They said, “Why are you opposing the project—it won’t be of any benefit to you or any use. It’s no use going against the government, they will complete the project by force. You should accept compensation for your land and take whatever benefits the company and government give you. You could get jobs in the project... Just take the jobs.”

I asked them how many jobs were there. They said about 200 to 250. I told them that the number of people who will lose land is much more than 200 to 250. I said, “What is the use of all that? If we have land, we can grow crops, graze, implement horticulture. Without land, we can do nothing.” They told me, “What’s the use? The government will forcibly help Enron complete the project...”

Where was the need of policemen to lecture us about Enron? They must have come to know that the fight in the village was related to Enron. The police were government servants, why did they not lecture the pro-Enron people for attacking us? It is not their job. From what I can tell, there is clear connivance between the police and Enron, and the police are paid to take sides.212

Padyal waited until 4:30 p.m. for Desmukh, but he never arrived. Because he was in pain and had missed the bus to his village, Padyal signed the incomplete complaint and managed to obtain a private vehicle to return home.

Twenty villagers who had been attacked were charged with many offences, including rioting, rioting with deadly weapons, unlawful assembly, attempted murder, causing hurt, causing hurt with a deadly weapon or corrosive substance, reckless endangerment, criminal mischief, trespassing, and criminal intimidation.213 All but two were kept in custody until April 19, and the others were released on April 21. The charges carry very severe penalties: attempted murder, for example, can be punished with life imprisonment. As of October 1998, the cases were still pending.

The Banes and their associates, however, were charged under Section 37 of the Bombay Police Act and released on bail the same day. Following the incident, fifteen to twenty State Reserve Police were stationed in Kathalwadi for a month and remained there until May 1997.

As we have described above, police have assaulted and arbitrarily detained individuals known to oppose the Dabhol Power project. In many cases, these abuses have been directed at groups of demonstrators or, as in the case of Medha Patkar and other NAPM members, have followed from externment orders. But police have also singled out specific individuals for physical reprisal following disputes between anti-Enron villagers and pro-Enron contractors or laborers. Two cases are described below. Following both incidents, the villagers—the victims of the attack—were charged with offences under the Indian Penal Code.

Sanjay Pawar: February 1997

Sanjay Pawar was beaten by State Reserve Police officers following a quarrel with local contractors on February 17, 1997. Subsequently, he was arrested on February 28, 1997 and charged with wrongful restraint, assaulting a public servant, and provoking the police officer to “break the peace” because of the incident on February 17.214 The charges carry a maximum sentence of up to two years’ imprisonment. The case had not been resolved as of October 1998. To our knowledge, no police officer has been investigated or charged for assaulting Pawar.

According to Pawar, he participated in the January 30, 1997 protest, and whenever people from the village participated in demonstrations against the project, he would join. Pawar told Human Rights Watch:

I don’t want Enron because of the pollution and the cost escalations of essential commodities, like electricity. There is also the way they take land. Our village could face displacement because of Phase II.215

According to Pawar, the incident began over a dispute not overtly linked to opposition against the power project. At approximately 10:00 a.m. on February 17, 1997, while Pawar was working for a road construction firm that is building roads from Guhagar village to the Dabhol Power project site, three or four tankers carrying water, followed by a truck containing officers from the State Reserve Police (SRP), drove past the workers. Pawar flagged down the tankers and asked them to slow down and to leave some water on the road. Since Pawar and others were digging up hard dirt, the water would have softened the ground and made their work easier. The drivers disagreed, told Pawar that he was obstructing them and slowing them down on purpose, and said they could drive as they pleased.

Following that exchange, the SRP officer-in-charge got out of the truck and asked Pawar why he had stopped the tankers. When Pawar explained the situation, the officer started yelling at him, then struck him repeatedly with a lathi. The force of the beating was so severe that the lathi broke over Pawar’s head. Pawar told Human Rights Watch:

I collapsed, and the SRP continued to beat me with their fists and boots. They put me in the SRP van, and the SRP in charge kicked me. About twenty-five to thirty of my coworkers tried to intervene to keep them from putting me in the van, but the police told them to leave or they would deal with them.216

The police took Pawar to the infirmary at the DPC project site. His head wound, which required stitches, was treated by the company doctor. Within an hour of the assault, news of Pawar’s beating had spread around the community; approximately 200 villagers blocked the road near the project and demanded his release. Concerned about his being on company premises in police hands, villagers wanted him treated at a government hospital and not at the company’s infirmary.

When the local police heard about the roadblock, Assistant Sub-Inspector Satoshe and Circle Inspector Desmukh came to the site. The villagers told them what had happened and said that they would not let traffic pass until Pawar wasreleased. A few hours later, around 2:00 p.m., Mangesh Pawar and Sadanand Pawar (no relation) were allowed to take Sanjay Pawar from the site.

Later that afternoon, villagers had a procession, led by former High Court Justice B.G. Kolse-Patil, demanding that police officers leave the Dabhol Power project site and that local businesses cancel their contracts with DPC in protest. The procession ended a few hours later, and villagers dispersed.

On the morning of February 28, Mangesh Pawar and Sadanand Pawar were served with prohibitory orders and arrested and Sanjay Pawar was arrested for assaulting an SRP officer.217 Sanjay Pawar told Human Rights Watch:

I was on leave from February 17 to 20 because of my injuries. On the 28th, I was back at work when Circle Inspector Desmukh arrested me around 8:30. He didn’t tell me anything, just took me to the lockup at Guhagar. I had no idea why I was grabbed. I was in the lockup for over an hour; Judge Kolse-Patil was there as well. We were taken to [the court at] Chiplun. Kolse-Patil was charged for violating prohibitory orders and causing obstruction.218

Commenting on his experience, Pawar said, “Security is given only to the company—never to the people.”219

In the meantime, a broader crackdown was occurring. Later on February 28, while protesting police excesses, several hundred protesters from surrounding villages participated in a hunger strike at the Guhagar police station. They were arrested for violating Section 37 of the Bombay Police Act, and some of the participants were beaten by police. One protester, Surendra Thatte, told Human Rights Watch:

I was arrested on February 28, 1997. This was during a fast with Medha Patkar to protest at the police station with about 500 other people. Around 11:30 a.m., the police arrested about 225 people. We were shouting slogans, singing songs, and giving speeches when they arrested us. We were going to leave around 4:00 p.m., but they arrested us instead. They beat people with lathis and threw people in police vans, very brutal. Then they took them to Chiplun and presented them beforethe magistrate. In protest, people refused to post a personal bond and were jailed.220

The cases against protesters were still pending as of October 1998.

Veldur raid: June 1997

A further incident, prompted by a heated argument and unarmed scuffle between DPC laborers, villagers opposed to the project, and the police occurred on June 2 and 3, 1997, less than a week after Medha Patkar and other activists were arrested, beaten, and detained by police. Following the incident on June 2, the police launched a raid on the village of Veldur. The police beat villagers, then arrested twenty-six women and thirteen men.

On June 2, 1997, as DPC laborers went through Veldur village on their way to the Enron site, they confronted villagers who were opposed to the project. Local residents did not want them to pass through the village because they worked for DPC. A shouting match and some minor scuffles ensued between the two parties. Villagers reported that the workers were verbally abusive and threatening them.221 Although the villagers were unarmed, the laborers left and returned with a police escort, comprising eleven male and two female officers. More arguments and scuffles took place. During the argument, one of the female police officers, R.P. Nachankar, slapped sixteen-year-old Sugandha Vasudev Bhalekar, which caused an altercation between some of the villagers and the police women.222 Officer Nachankar’s sari was partially stripped. Then, Police Sub-Inspector Waman Janu ordered the police to fire one round in the air, after which the crowd dispersed.223 The laborers passed through the village and went to the site of the project.

Early in the morning on June 3, the Maharashtra Police and the Special Reserve Police Force launched a raid on the village of Veldur. At approximately 6:00 a.m., eight vans of the State Reserve Police Force and three jeeps of Guhagar police entered Veldur village, carrying approximately 135 police officers.224 According to the Committee for Peoples’ Democratic Rights (CPDR), a respected Indian human rights organization, the police divided into groups of ten and beganto raid households in the village while arbitrarily beating and arresting villagers. Because of the early hour, most of the adult men had left to go fishing, so the majority of people in the village were women, children, and the elderly. Gangaji Jambhalkar, an elderly fisherman in Veldur who was standing in a small community center adjacent to the jetty on the morning of June 3, told Human Rights Watch:

On June 2, there was a skirmish over the Enron issue. The next day, I was standing near a shop. The sudden action police took against us was surprising. I was beaten by a lathi on my wrist and fell to the ground. They came down and just started beating people. I have a small two-cylinder boat and use it as a fisherman. I am sixty-five years old and watched them beat people.225

One villager, Vithal Padyal, watched the police enter his home, beat his family, and arrest two of his children. Ironically, the young people who were arrested worked for DPC. His account underscores the arbitrariness and brutality of the police. He told Human Rights Watch:

On the other side of the village, there was a skirmish [on June 2]. The next day, at six in the morning, the police came in vans. They started going around to houses. They came in and first hit my daughter, Madhuri Madhukar Batokar, who was nine months pregnant at the time. She was hit on the back with a lathi. The police tried to hit me, but I said, “Look at my hair” because it is gray and I am old, and they didn’t hit me. Then they caught hold of my son Laloo and his brother Ankhosh. They are twenty-one and twins. Both of them worked at the DPC site, so they showed the police their ID cards. In spite of showing them the ID cards, the police beat them with lathis.226

The twins were taken into custody by the State Reserve Police. According to their father, Circle Inspector Desmukh kept them in custody for six days without producing them for the court. Desmukh asked the young men to give the names of people involved in the skirmish and protests. They were unable to provide this information to police, since they had not been involved in the protests. After sixdays, they were transferred to the jail at Chiplun and then transferred again to Yerewada jail, where they were imprisoned for another six days.227

The police also arrested and detained juveniles during the raid in violation of India’s Juvenile Justice Act, which prohibits the detention of males under the age of sixteen and females under the age of eighteen.228 Ranjana Padyal, a resident of Veldur, described how the police entered her home and began beating her family members and arrested her fourteen-year-old son, Balakrishna Ramesh Padyal:

They just entered my house, hit my husband with lathis. He works in Bombay and had come home to attend a marriage. They woke up my fourteen-year-old son and told him that he had to come with them... They kept him in custody for thirteen days. They never said what law they had arrested him under, and he was never associated in the protests against the project.229

The Peoples’ Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), a respected Indian human rights organization, investigated the incidents at Veldur and reported that several other juveniles had been arrested and detained: among them, sixteen-year-old Sugandha Vasudev Balekar (who had been assaulted by a female police officer the previous day), two sisters, fourteen-year-old Vanita and fifteen-year-old Sanita Patekar, and fifteen-year-old Rakha Kishore Padyal. Police falsely recorded the ages of these minors so that they would be considered adults, and neither the court nor the police attempted to verify their status as juveniles.230

Both the PUCL and the CPDR determined that several women of the village were subjected to exceptionally brutal treatment, in part because their male relatives were recognized leaders of the anti-Enron protests. For example, twenty-four-year-old Sadhana Bhalekar is the wife of Vithal “Baba” Bhalekar, a local fisherman and a recognized protest leader who had been arrested as early as 1994 for demonstrating against the project. On June 3, police armed with batons broke into her home, beat sleeping members of her family, then smashed the window and door of her bathroom while she was taking a bath. Bhalekar, who was three months pregnant at the time, was dragged out of the bathroom, naked, and beatenwith batons in her house and on the street. Bhalekar told the CPDR fact-finding team that Assistant Sub-Inspector P.G. Satoshe was present and told police, “This is Baba Bhalekar’s wife, bang her head on the road.”231 Bhalekar provided the details of the incident in an affidavit filed with the Chiplun judicial magistrate on June 9, 1997.232

Police also beat her polio-stricken and mentally retarded brother-in-law Pradeep Dattatreya Bhalekar and her nephew Anil. In addition, two of her sisters-in-law, Indira Pandurang Madekar and Supriya Chandrakant Padyal, who were staying at the house for a vacation, were dragged outside and beaten.233 Bhalekar’s affidavit to a judicial magistrate states:

While I was being taken forcibly out of the house to the police van, my one and a half year old daughter held on to me but the police kicked her away. My sisters-in-law, Mrs. Indira Pandurang Medhekar and Mrs. Supriya Chandrakant Padyal had come to their maternal home. Of these, Supriya Chandrakant Padyal was thrown off the loft on to the ground and was beaten with batons and forced into the van. Indira Pandurang Medhekar too was beaten and forced into the van.234

Other villagers were similarly beaten. Ambaji Dabholkar told the CPDR fact-finding team that two daughters of Viju Bhalokar were beaten so severely that they began to urinate.235

Eight of the villagers formally complained of ill-treatment by police, including Anil Medekar, Supriya Padyal, Sugandha Bhalekar, Anita Beradkar, Sunanda Bhalekar, Sahdana Bhalekar, Sangeeta Bhalekar, and Indira Madekar. The PUCL determined that they had injuries consistent with beating by police batons.236

Thirty-nine people—twenty-six of them women—were arrested in the Veldur raid. They were charged under the Indian Penal Code for rioting, rioting with deadly weapons, causing hurt to deter a public servant from his duty, endangeringhuman life, and attempted murder. These charges carry a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.237 As of October 1998, the charges were pending.

178 They were charged under Sections 147, 148, 149, 323, 324, 336, 341, and 435 of the Indian Penal Code.

179 They were charged under Sections 147, 148, 149, 323, 324, 336, 341, and 435 of the Indian Penal Code.

180 Human Rights Watch interview with Mahadev Pandurang Solkar, Bombay, February 6, 1998.

181 Human Rights Watch interview with Dattaram Jangli, Borbatlewadi village, February 15, 1998.

183 Shiraz Sidhwa, “Alive and Well: Against the Odds, Enron Makes a Go of It in India,” Far Eastern Economic Review, December 11, 1997.

184 Letter from the Center for Holistic Studies to the Enron Corporation in response to Enron’s letter to Amnesty International, November 20, 1997.

185 Human Rights Watch interview with Sadanand Pawar.

187 The Bombay serial bomb blasts took place in 1992 when a series of explosions killed several hundred people. The blasts were attributed to underworld figures in Bombay. TADA was the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities law that imposed draconian anti-terrorism legislation throughout the country.

188 Human Rights Watch interview with Mangesh Chavan.

189 Dabhol Samvad: The Monthly Bulletin of the Dabhol Power Company, Vol. 1, No. 2, March 1997, p. 2.

190 Dabhol Samvad..., Vol. 1, No. 3, April 1997, p. 6.

191 “Guhagar Residents Assault Enron Officials,” The Indian Express, December 12, 1997.

192 Letter from the Center for Holistic Studies to the Enron Corporation.

193 This offence is classified as “voluntary hurt” under Section 324 of the Indian Penal Code and carries a sentence of up to three years’ imprisonment. Section 324 of the Indian Penal Code states: “Whoever, except in the case provided for by section 334, voluntarily causes hurt by means of any instrument for shooting, stabbing, or cutting, or any instrumentwhich, used as a weapon of offence, is likely to cause death, or by means of fire or any means of any explosive substance, or by means of any substance which is deleterious to the human body to inhale, to swallow or to receive into the blood, or by means of any animal, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, or with fine, or both.”

194 “In the Service of a Multinational...,” pp. 17-18. A death threat is defined as “criminal intimidation” under Section 503 of the Indian Penal Code and is punishable with up to two years’ imprisonment.

195 Human Rights Watch interview with Sadanand Pawar.

196 An anonymous death threat is considered criminal intimidation under sections 506 and 507 of the Indian Penal Code and is punishable with up to nine years’ imprisonment. Section 507 is prosecuted with Section 506 of the Indian Penal Code, which provides up to seven years’ imprisonment for committing criminal intimidation. Section 507 of the Indian Penal Code states: “Whoever commits the offence of criminal intimidation by an anonymouscommunication, or having taken precaution to conceal the name or abode of the person from whom the threat comes, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years, in addition to the punishment provided for the offence by Section 506.”

197 Human Rights Watch interview with Anand Arjun Bhuvad, Kathalwadi village, February 15, 1998.

198 Human Rights Watch interview with S.D. Khare, Guhagar, February 14 1998.

199 Human Rights Watch interview with Anand Arjun Bhuvad.

200 According to villagers, the other men with Ashok Bane were, his brother, Dilip Bane, an Enron labor contractor; Chandrakant Bane, a relative of theirs; Ashok Bait; Rajendra Durogoli; Sandeep Bagwe; Dinesh Bait, Hari Kansare, Gorakh Bagawe, and Santosh Bhuvad all came out of Devale’s house around the same time. Chandrakant Bane was recognized by DPC as a local Shiv Sena leader and is pictured with Sanjeev Khandekar in the May 1997 issue of Dabhol Samvad: the Monthly Bulletin of the Dabhol Power Company.

201 Human Rights Watch interview with Ashok Padyal, Bombay, February 19, 1998.

205 Human Rights Watch interview with Anand Arjun Bhuvad. Konvel is the village where the fuel complex for the Dabhol Power project is located.

207 Human Rights Watch interview with Ashok Padyal.

209 Human Rights Watch interview with Anand Arjun Bhuvad.

210 Human Rights Watch interview with Ashok Padyal.

213 The villagers were charged under sections 147, 148, 149, 307, 323, 324, 336, 337, 427, 452, 504, 506 of the Indian Penal Code.

214 Pawar was charged under sections 341, 353, and 504 of the Indian Penal Code.

215 Human Rights Watch interview with Sanjay Pawar, Veldur village, February 14, 1998.

217 Police viewed Sadanand Pawar and Mangesh Pawar as leaders of demonstrations against the Dabhol Power project. See above.

218 Human Rights Watch interview with Sanjay Pawar.

220 Human Rights Watch interview with Surendra Thatte.

221 Committee for Peoples’ Democratic Rights, “Say Yes to Enron: Police Coercion and Popular Resistance,” July 1997, Bombay, p. 2.

225 Human Rights Watch interview with Gangaji Jambhalkar, Veldur village, February 14, 1998.

226 Human Rights Watch interview with Vithal Padyal.

228 For a detailed discussion of the Juvenile Justice Act, 1986, see: Police Abuse and Killings of Street Children in India, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1996).

229 Human Rights Watch interview with Ranjana Padyal, Veldur village, February 14, 1998.

230 “Report of the Incidents ...,” pp. 5-6.

231 “Say Yes to Enron...,” p. 4.

232 Affidavit of Sadhana Vithal Bhalekar, June 9, 1997.

233 “Say Yes to Enron...,” pp. 4-5.

234 Affidavit of Sadhana Vithal Bhalekar.

235 “Say Yes to Enron...,” pp. 4-5.

236 “Incidents Occurring from June 2, 1997...,” pp. 3-4.

237 Ibid. Specifically, the police charged villagers under sections 147, 148, 149, 307, 332, 336, 337, 341, 353, and 427 of the Indian Penal Code and Section 135 of the Bombay Police Act.