On June 30, 2020, the Chinese government imposed the draconian National Security Law (NSL) on Hong Kong with devastating consequences for human rights. Basic civil and political rights long protected in Hong Kong—including freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly—are being erased. It is evident that the NSL is an integral part of Beijing's larger efforts to reshape Hong Kong’s institutions and society, transforming a mostly free city into one dominated by Chinese Communist Party oppression.

Once Asia’s “protest capital,” Hong Kong authorities now prohibit peaceful protests, albeit in the name of controlling the Covid-19 pandemic. Over 100 people have been arrested for violating the NSL, while over 10,000 have been arrested for their involvement in the 2019 protests, often many months after the events in question. The justifications for those arrests are frequently dubious and many violate rights guaranteed under international human rights law. Hong Kong’s police, once considered “Asia’s Finest” for their adherence to professionalism and respect for rights, are increasingly implicated in abuses with impunity.

The Chinese government has also taken rapid-fire steps to reshape multiple sectors and institutions in Hong Kong, from the arts to the local parliament—the Legislative Council, or LegCo—to the civil service. Often Beijing describes these moves as “reforms” to “plug loopholes,” euphemisms to attack hard-won freedoms. The “electoral reforms” imposed on Hong Kong, for example, effectively gutted the city’s competitive elections and replaced them with sham races in which only those loyal to Beijing can run for the LegCo.

The case of Tam Tak-chi, also known as Fast Beat, exemplifies the dizzying speed at which Hong Kong’s freedoms are being eroded. Tam, vice-chairman of the pro-democracy political party People Power, stood at street stalls and shouted protest slogans—peaceful protest activity that has long been a feature of Hong Kong life. For this, the authorities have charged him with 14 crimes including “uttering seditious words” and “holding an unauthorized assembly.” Tam has been held in solitary confinement since September 2020 while awaiting trial.

Beijing has sought to decapitate Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. In January 2021, the authorities arrested 53 pro-democracy politicians for “subversion” because of their involvement in a public opinion poll to coordinate candidates for upcoming LegCo elections. Authorities prosecuted prominent pro-democracy lawyers, such as Martin Lee and Margaret Ng, and younger activists like Joshua Wong, who received a 10-month sentence for lighting candles and sitting in the park, on top of other convictions. Prison terms handed down by the courts against pro-democracy leaders are lengthening as the Hong Kong authorities increasingly bring charges against them.

The authorities are simultaneously pressing Hong Kong people to publicly express loyalty to the Chinese government. Teachers face pressure to self-censor and promote patriotism. Civil servants and even government contract workers are required to pledge allegiance to the “Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China,” which emphasizes Beijing’s authority over Hong Kong, or be fired.

Hong Kong’s judiciary and police have increasingly shown themselves to be tools of Chinese state control rather than enforcers of the rule of law. New and proposed legislation, including the National Anthem Law and a “fake news” bill, will make public displays of loyalty to Beijing a requirement while also raising the cost for peaceful criticism and independent journalism. Beijing has signaled that it intends to impose “judicial reforms” that could dismantle the city's long independent and professional judiciary. The NSL carves out a separate track through which political cases will be heard, one in which cases are handled by special police officers, handpicked prosecutors and judges, and even a special unit in the correctional services. Suspects are deprived of important procedural protections normally available under Hong Kong’s legal system.

The Chinese government is also reshaping human rights in Hong Kong through the mobilization of pro-Beijing politicians and individuals, often using state-owned news media Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po. In the past year, Beijing has used these two outlets to smear and attack pro-democracy advocates—in many cases making false accusations that they are directed by the US government—or to pressure public institutions or private companies. Such attacks, which are then joined by a chorus of pro-Beijing politicians and groups, create an atmosphere of intimidation. Some of those named by Beijing relent to pressure because they fear arrest, imprisonment, or other retaliatory actions, such as the loss of government funding.

Some pro-democracy figures, such as former LegCo members Nathan Law and Ted Hui, fled the city this past year, along with thousands of other Hong Kong people. But the NSL is having an intimidating effect beyond Hong Kong and China. Under the law, anyone who criticizes the Hong Kong or Chinese governments anywhere in the world can potentially be charged with violating the security law. Hong Kong authorities have vowed to “pursue fugitive offenders as long as they live.” A number of governments have suspended extradition treaties with Hong Kong, while the United Kingdom has offered refuge to some Hong Kong people.

The NSL undermines rule of law in Hong Kong and human rights guarantees enshrined in Hong Kong’s de facto constitution, the Basic Law. It contravenes the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which is incorporated into Hong Kong’s legal framework via the Basic Law and is expressed in the Bill of Rights Ordinance. The ICCPR guarantees the rights to freedom of expression, information, association, and peaceful assembly, among other basic liberties. It protects the rights to participate in public affairs, vote at genuine periodic elections, and be a candidate for public office. It also ensures the rights of criminal suspects to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial court.

This short report is by no means a comprehensive record of the events that have taken place in Hong Kong since June 30, 2020, but highlights Beijing’s efforts to dramatically remake Hong Kong.

Restricting the Right to Free Expression

In a city where people have long enjoyed free speech and access to information, authorities are banning political slogans, censoring art, and harassing pro-democracy businesses. The Hong Kong police have even set up a “National Security Hotline” to encourage people to inform on each other for violations of the National Security Law.

Banning Slogans

Hours after the enactment of the NSL, Hong Kong police, on July 1, 2020, arrested 10 people at a protest for violating the NSL because they had banners, fliers, or stickers with the words “Hong Kong independence” or “Liberate Hong Kong.” The next day, the Hong Kong government banned the 2019 protest slogan, “Liberate Hong Kong, the Revolution of Our Times,” because it “connotates Hong Kong independence” and thus “subverts state power.” Protesters then displayed blank paper to protest against censorship, or got around the new censorship by displaying geometric shapes, English letters, or numerals that rhyme with the banned slogan, or other creative designs.

As the June 4 anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre approached, the Chinese and Hong Kong governments signaled that the slogan Hong Kong people chant during the annual Victoria Park commemorative vigil, “End One-Party Dictatorship,” could violate the NSL. Responding to media enquiries about the slogan, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam said that people “should respect” the Chinese Communist Party. Pro-Beijing politician Elsie Leung openly called on the organizers to remove the slogan from their platform.

During the 2019 protests, Hong Kong people wrote political messages everywhere—at protest sites, on walls, lampposts, roads, and sidewalks—and “Lennon Walls” sprung up across the city, where people put up pro-democracy messages on post-it notes and posters. These Lennon Walls became sites of contention, as the Hong Kong government and pro-Beijing groups removed them in “clean-ups” while pro-democracy activists tried to protect or recreate them, sometimes facing violence from Beijing supporters. After the NSL was adopted, the remaining Lennon Walls were removed. Hong Kong University administrators cleared students’ Lennon Wall and then put up two-meter water barriers to prevent student access. Some pro-democracy shops removed their Lennon Walls, while others put up blank post-it notes in protest.

Harassing Businesses

During the 2019 protests, small businesses formed “the Yellow Economy Circle” (yellow being the color of Hong Kong’s democracy movement), in which pro-democracy consumers and businesses banded together to support each other. Following the enactment of the NSL, some of the most prominent pro-democracy businesses have been harassed.

Chickeeduck, a children’s clothing chain, was first pressured by shopping mall management to remove a two-meter tall “Lady Liberty” statue, made by artists during the 2019 protests, in June 2020. The mall then informed Chickeeduck that it would not renew its lease and forced the shop to relocate. Human Rights Watch reached out to the mall management concerning the accounts above, but, at time of writing, we received no response. When Chickeeduck opened a new store in May 2021—with the Lady Liberty statue—National Security Police officers arrived three days later, filming the shop, and taking Hong Kong ID numbers of its patrons. Police later said that Chickeeduck’s shopfront—which had graffitied a scrambled 2019 protest slogan—may violate the NSL. In protest, long lines of people shopped at Chickeeduck afterwards.

Another “yellow business” harassed was pro-democracy grocery chain Abouthai. On April 12, 2021, custom officials went to Abouthai’s 25 stores and warehouse, confiscated HK$400,000 (US$51,500) worth of products, and arrested a company executive. Custom officials claimed that the grocery chain had failed to put bilingual safety labels on imported products, a common practice among the city’s retailers that is rarely punished, according to Hong Kong media reports.

Censorship

From museums to movie theaters, Hong Kong’s arts community is experiencing censorship for the first time. One of the most prominent examples involves M+, a new flagship museum set to open at the end of 2021. M+ pulled a work by Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei from its opening after pro-Beijing news outlets and politicians criticized it for showing a picture of Ai holding up his middle finger in Tiananmen Square, claiming that it “spreads hatred against China.”

Similar censorship affected “Inside the Red Brick Wall,” an award-winning documentary about the police siege of Hong Kong Polytechnic University during the 2019 protests. Hours before the film’s scheduled showing, the theater pulled the film because it had “received too much attention.” Chinese government media and pro-Beijing politicians had been denouncing the film as inciting hatred against the Hong Kong government. Later, articles in Wen Wei Po and Ta Kung Pao attacked the film distributor’s funder, Hong Kong Arts Development Council (HKADC), a statutory body. The articles named a number of HKADC grantees, performing arts groups that they say are pro-democracy and thus in breach of the NSL. HKADC quickly succumbed to the pressure and publicly announced that any group “that promotes Hong Kong independence under the current laws” may now have their funding cut off. Then, on June 11, the Hong Kong government revised rules to bar films that “endanger national security,” introducing film censorship for the first time in the city.

Suppressing Independent Media

Beijing is assaulting Hong Kong’s independent media. While Hong Kong’s journalists have for years reported increasing self-censorship because of heightened pressure by Chinese authorities, they are now subjected to overt censorship from the authorities and the police.

The Hong Kong government has targeted Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) in an apparent attempt to transform the independent public broadcaster into a pro-Beijing propaganda outlet. The crackdown on RTHK began around February 2020, after the police complained about a satirical episode of the popular show “Headliner,” claiming it “misled” the audience about the police. Then in May 2020, the Communications Authority ruled that the satirical episode had “insulted the police.” The next month, RTHK suspended the program, which had been running since 1989.

In May 2020, the Commerce and Economic Development Bureau, responsible for supervising RTHK, initiated a “review” of RTHK’s management. The Hong Kong government then replaced the head of RTHK with a career bureaucrat, Li Pak Chuen, who had no prior media experience. During his first month, Li pulled several episodes off the air, stating that the programs “lack[ed] objectivity,” though he did not provide details. The programs removed appear to be current affairs programs with producers or guests who hold pro-democracy views. He also told staff that he would vet all episodes of three current affairs programs before they could air. In April 2021, RTHK management reportedly told producers they may be held financially responsible for cancelled episodes. Li also ordered staff to withdraw from consideration for press awards in 2021, because the bodies issuing the awards were going to honor RTHK’s coverage of current affairs, including the 2019 protests.

After Beijing retaliated against the BBC for reporting on rights abuses in the Xinjiang region by banning its world news channel from China, RTHK also dropped its BBC programs. In May 2021, RTHK acknowledged that it was deleting programs—those more than a year old—from its YouTube and Facebook pages.

RTHK journalists who gained prominence for their reporting have been punished. Yvonne Tong, known for grilling a World Health Organization official about Taiwan, quit after Beijing-owned newspapers targeted her about her personal life. RTHK fired hard-hitting journalist Nabela Qoser in April 2021. Paul Lee, producer of the highly regarded program “Hong Kong Connection,” quit after RTHK management reportedly told him that the program will shift from focusing on current affairs to “human interest and livelihood issues.”

RTHK also started playing China’s national anthem daily from November 2020 and introduced in April 2021 a program hosted by Chief Executive Lam four times a day.

The Hong Kong government forced one of Hong Kong’s most popular newspapers, Apple Daily, to close because it promotes democracy and reports on government abuses. In August 2020, more than 200 Hong Kong police officers raided Apple Daily’s offices and arrested its owner, Jimmy Lai, his two sons, and four top executives of the Next Media group, the Apple Daily’s parent company.

Lai was one of the first high-profile people to be arrested on NSL crimes. Evidence against him apparently consisted of his media interviews and statements on Twitter, none of which espoused violence or other behavior that would constitute a cognizable crime under international law. Lai was separately convicted of organizing and participating in an “unauthorized assembly” for attending two protests in 2019 and sentenced to a total of 14 months in April 2021. He faces an additional six charges in four other cases, including “conspiracy to defraud,” attending and inciting “unauthorized assembly,” and “colluding with foreign elements.”

In April 2021, the two state-owned newspapers called on the Hong Kong government to ban Apple Daily. In May, using new powers under the NSL, the Hong Kong Security Bureau froze Lai’s HK$500 million (US$64 million) worth of assets and shares. In June, hundreds of police raided their offices again, arresting five executives and a political commentator for “colluding with foreign countries” and seizing journalistic materials including journalists’ phones and laptops. Apple Daily closed on June 24 due to financial distress caused by official harassment. Lai, 72, has lost his liberty, his business, and likely his life’s earnings for alleged crimes in violation of his basic rights.

The Hong Kong government has repeatedly said it would impose a new “fake news” law to fight “misinformation” including “hate speech and lies,” a characterization it increasingly applies to critical or unflattering views of the government and the police.

The government is also amending the Privacy Ordinance to criminalize the practice of “doxing”— the disclosure of personal data—with a proposed penalty of up to five years in prison. There are reasons to be concerned about doxing—over the course of the protests, numerous police officers, protesters, and journalists complained about unauthorized release of their personal information—but the proposed new law is troubling because of the possibility it will be used disproportionately against pro-democracy activists, as has been the case with existing laws used in such cases.

Restricting Access to Information

The Hong Kong government has also begun to restrict people’s access to information by removing certain books from libraries, blocking websites, and restricting access to public databases.

Pulling Library Books

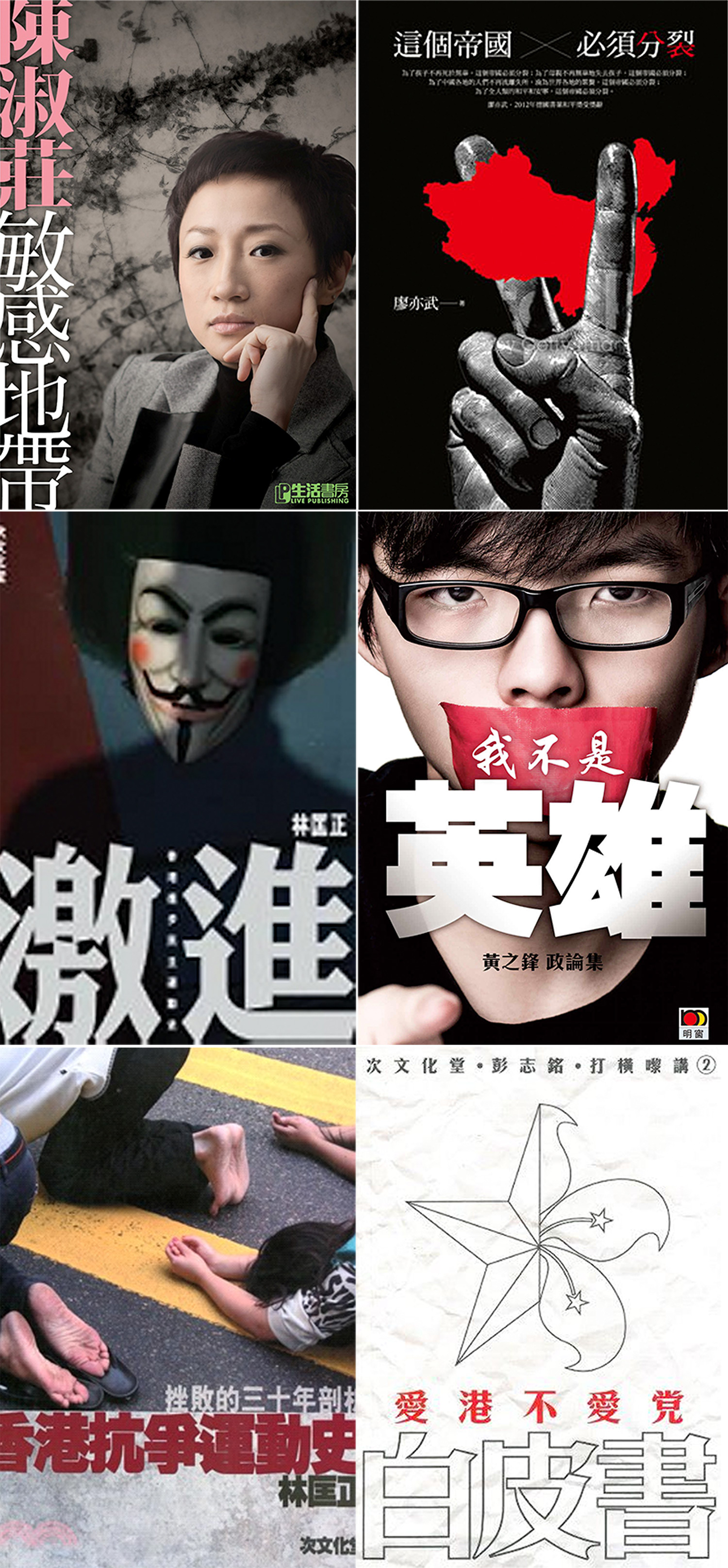

The Hong Kong Leisure and Cultural Services Department has removed at least 34 books from all branches of public libraries since the enactment of the National Security Law. The department said they are “reviewing” these books, which includes those written by pro-democracy leader Joshua Wong, Chinese exiled writer Liao Yiwu, and others critical of the Chinese government, for potential breach of the NSL.

Blocking Websites

In January 2021, the Hong Kong police, using powers under the NSL that do not require judicial warrants, ordered internet service providers to block access to HKChronicles.com, a website that documents police officers who have committed acts of violence and abuse, but has also revealed personal information about them, such as phone numbers, and about people with pro-government views. In June 2021, an Israeli hosting company took down the website of Charter 2021, a Hong Kong exile initiative asserting their vision, at the request of the Hong Kong police, though it reinstated it following a widespread outcry.

Restricting Access to Public Databases

In an unprecedented case, award-winning investigative journalist and producer Bao Choy was arrested and convicted of “making a false statement” in April 2021, for searching a public vehicle registration database to investigate a violent gang attack on pro-democracy protesters during the 2019 protests. Eight journalist associations condemned the decision, accusing the Hong Kong government of “using the excuse of protecting privacy…to help the powerful to hide facts.”

In March 2021, the Hong Kong government announced that the Company Registry, long important for those researching Chinese companies and official corruption, will no longer make public the Hong Kong ID numbers and residential addresses of company directors and secretaries to “protect privacy.” Previously, in 2019, the government limited the information that members of the public—including the media—could access from marriage and birth registries, information that also previously had been used to uncover official misconduct.

Restricting Academic Freedom

Hong Kong’s eight universities have been under growing pressure to rein in pro-democracy students and faculty.

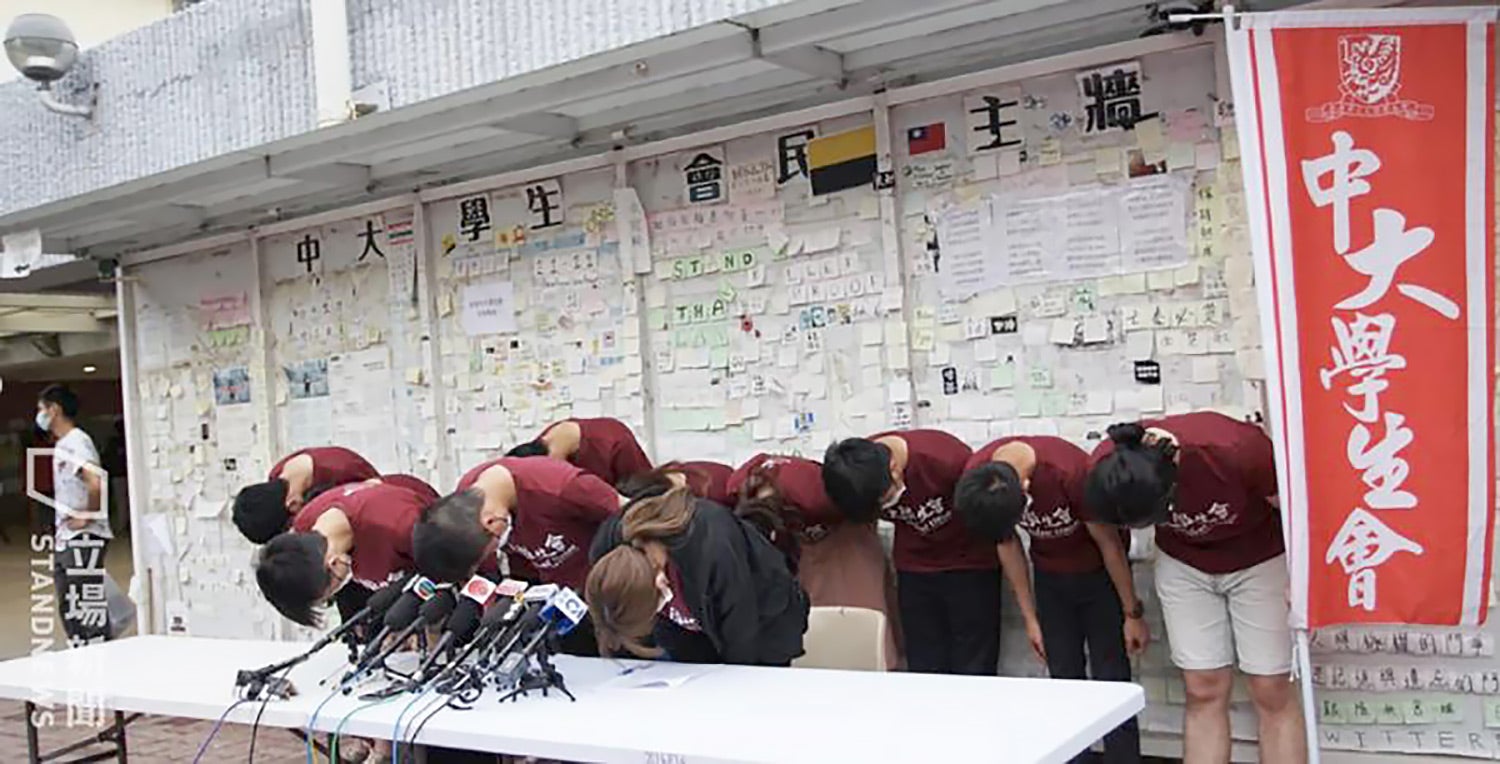

Universities have shut down, censored, or even reported to the police the peaceful activities of students on campus. In one case, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) called the police on students and graduates who marched peacefully in protest against the National Security Law in November 2020. Police later arrested eight people, including CUHK graduates, for “unlawful assembly” and “inciting separatism” because they had shouted the 2019 protest slogan, “Liberate Hong Kong, the Revolution of Our Times.”

Universities have also been increasingly hostile towards their student unions: three universities announced that they would refuse to collect dues on behalf of the student unions while two have refused to provide venues for their activities. Universities have made no discernible efforts to protect students facing intimidation from Chinese government-owned media and pro-Beijing individuals for running for unions, which, in the case of the CUHK student union, involved death threats to the leaders of the union and their families. By 2021, only one of the eight universities had a functioning student union.

Universities have also fired pro-democracy academics. In July 2020, Hong Kong University sacked scholar-activist Professor Benny Tai. In August 2020, Baptist University terminated a contract with pro-democracy social worker and former legislator Shiu Ka-chun. In both cases the available evidence suggests that the individuals lost their jobs because of their pro-democracy activities.

Academics have also faced intimidation by Chinese government-owned papers and pro-Beijing politicians. For example, both accused University of Science and Technology Professor Lee Ching-kwan of “advocating independence” after she gave a speech at an online forum saying, “Hong Kong belongs to the world”; they called on the police and university to investigate her. Academics also contend they are being surveilled, both electronically and by students in class.

Dismantling Free Elections

The Chinese and Hong Kong governments have taken multiple actions to reduce Hong Kong’s semi-democratic Legislative Council to a rubber-stamp body.

In July 2020, the Hong Kong government postponed by a year the LegCo elections, originally slated for September during the city’s highest peak of Covid-19 infections. Pro-democracy candidates were expected to make considerable gains.

The Chinese government then issued a decision in November 2020 to disqualify Hong Kong legislators who “publicize or support independence,” “seek foreign interference,” or pursue “other activities that endanger national security.” Following this decision, the Hong Kong government immediately disqualified four pro-democracy legislators. Fifteen other pro-democracy legislators resigned, leaving LegCo without any effective pro-democracy opposition.

On January 6, 2021, Hong Kong police arrested 53 pro-democracy politicians for “subversion” because they had organized or participated in a public opinion poll in July 2020 to coordinate pro-democracy candidates for upcoming LegCo elections. Despite the government’s threats at the time of the poll, including raiding the office of the poll organizers, over 600,000 Hong Kong people participated.

In March 2021, Beijing imposed further “electoral reforms,” changing the rules so that only those loyal to the Chinese Communist Party could win a seat in Hong Kong’s elections. For example, a pro-Beijing committee now vets all legislative candidates. In April 2021, following citizens’ calls to cast blank ballots to protest the changes, the Hong Kong government has also submitted revisions to the electoral laws to prohibit “incitement of others to cast blank ballots,” with sentences of up to three years in prison.

Depriving Accused Activists of Fair Trial Rights

The National Security Law establishes a separate track for processing those accused of political crimes. People accused of NSL offenses are investigated by a special department of the Hong Kong police, handled by prosecutors selected by the secretary for justice, and tried by judges handpicked by the chief executive. Their cases are overseen by mainland security authorities with a track record of severe human rights abuses.

The NSL denies bail to national security suspects unless the judge is convinced that they will no longer commit national security offenses. Over half of the people charged with NSL crimes are now held in custody, depriving them of liberty even though their trial may be months away. The NSL also allows suspects to be deprived of a public trial if state secrets would be disclosed, and of a jury trial if directed by the secretary for justice.

Some NSL suspects held in custody have been mistreated. Hong Kong’s Correctional Services has detained some NSL suspects in solitary confinement, in some cases for over two weeks and, in one case, for over 200 days. Correctional Services also refused to grant Democratic Party leader Wu Chi-wai temporary leave to attend his father’s funeral, though such leave is often granted to prisoners. Wu then applied to the court for leave, which was granted. Correctional Services have held activist Andy Li in a psychiatric hospital despite his not having a history of psychosocial issues. Li was caught together with 11 others fleeing from Hong Kong in a fishing boat to Taiwan and detained in China for months; he is facing three crimes in Hong Kong including “collusion with foreign forces.” The Correctional Services said it has a special unit—an elite force trained in handling prisoner riots—that has been increasingly deployed in transporting NSL suspects.

Undermining Judicial Independence

The Chinese government has stepped up pressure on Hong Kong’s independent judiciary, expressing anger at judges’ performance, especially in handling cases related to the 2019 protests. Wen Wei Po and Ta Kung Pao have run articles and opinion pieces that repeatedly named and attacked “yellow” judges, criticizing them when they question police or prosecution evidence, or when they hand down sentences Beijing considers too lenient. These media outlets have called for such judges to be punished for “encouraging chaos on the streets.”

In November 2020, the Hong Kong Bar Association wrote a letter to Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng, calling on her to “defend the judiciary and individual judges against these pernicious accusations,” which it says, “hover on the margins of a contempt of court.” Although Cheng made vague reassertions of the importance of judicial independence, she is not known to have taken any action.

Beijing’s newspapers and pro-Beijing politicians have also attacked the bar association’s new chairperson, Paul Harris, who had called on the government to revise the National Security Law so that it is consistent with the Basic Law. The papers accused Harris of having a “long history” of representing “foreign forces,” that he is “an anti-China politician,” and baselessly linked the organization he co-founded, Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor, with US intelligence agencies. Their calls for Harris to resign have intensified. Beijing’s representative office directly called for Harris’ resignation in April after he criticized the court’s jailing of pro-democracy leaders for commemorating the Tiananmen Massacre. They have also threatened to take away the bar association’s statutory powers, including those to certify barristers, which would have serious consequences for lawyers’ independence.

Beijing appears to be using these attacks to build up a case that Hong Kong needs “judicial reforms.” In marked departure from previous government records that asserted a separation of powers, Chief Executive Lam, in September 2020, instead said she hoped the executive, judicial, and legislative branches would cooperate with each other. Zhang Xiaoming, deputy director of the central government’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, asserted that, “Now is the time for judicial reforms.” Although the government has not yet formally announced concrete measures, pro-Beijing politicians have put forward a number of proposals, ranging from firing “unpatriotic judges” to introducing “political education” of judges.

Shutting Down Protests and Limiting Freedom of Association

Hong Kong’s Public Order Ordinance requires people to apply in advance to the police to demonstrate, a requirement that the UN Human Rights Committee has criticized as being contrary to the right to peaceful assembly. Since early 2020, Hong Kong police have repeatedly denied protest applications. The police cited the Covid-19 pandemic for these prohibitions, even though the organizers had said they would take appropriate social distancing and other preventive measures. On several occasions since March 2020, people who peacefully protest have been fined for breaking Covid-19 rules; those who shout the slogan “Liberate Hong Kong” have been arrested for violating the National Security Law.

The Hong Kong authorities have arrested over 10,000 people for the 2019 protests: 2,500 have been prosecuted, and, according to the police, 960 of them will “face legal consequences,” including jail time. Among them, some have been charged with “unlawful assembly,” a crime under the Public Order Ordinance. Prominent activists convicted of “unauthorized assembly” include pro-democracy lawyers Martin Lee and Margaret Ng.

In another case, Joshua Wong and three young activists were convicted of “unauthorized assembly” for marking the anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre in Victoria Park in 2020. For lighting candles and sitting down in the park, Wong was given a 10-month sentence. This adds to his existing sentence of 13½ months for taking part in another unauthorized protest in 2019, when protesters surrounded police headquarters. Wong’s case is typical among prominent activists, whose prison terms are lengthening as the government brings an increasing number of charges against them.

The Hong Kong government has also effectively banned the Victoria Park vigil—the only place under Chinese sovereignty where the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre was publicly commemorated every year. The Hong Kong police banned the gatherings in 2020 and in 2021, citing public health grounds. In 2021, the government stepped up its efforts by arresting the lead organizer ahead of the vigil, Chow Hang-tung, cordoned off the park, and stationed thousands of officers throughout the city to prevent protests. Pro-Beijing figures have also publicly attacked the vigil organizing group, baselessly claiming it is a subversive organization that has “colluded with foreign forces” and calling for it to be banned.

Beijing’s newspapers have for months targeted another major protest organizer, the Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF), claiming that the group “has gathered a motley crew of politicians and groups to bring chaos and disasters to the city, supported by foreign anti-China forces.” Hong Kong police have said it will “take actions” against CHRF for being an “unlawful organization.” Under such pressure, some participating groups withdrew from CHRF. CHRF’s convenor, Figo Chan, faces at least fourteen counts of crimes involving his efforts to organize peaceful protests in 2020. Chan has been held in custody since May 2021 for “organizing unlawful assembly.”

Hong Kong’s 2019 protests greatly expanded labor activism, as people formed thousands of new unions to join their more established peers, such as the pro-democracy Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, to strengthen the pro-democracy movement and to organize general strikes. In May 2021, the Hong Kong Labour Department said it will create a new position to “monitor and manage” these unions, including their compliance with the NSL, signaling an impending crackdown.

Beijing has also denied entry to Hong Kong to members of international nongovernmental organizations, including Human Rights Watch Executive Director Kenneth Roth, and has threatened to impose additional unspecified sanctions against them.

Following the imposition of the NSL, some civil society organizations and staff members have left Hong Kong due to growing security concerns.

Growing Police Impunity

The Hong Kong government has never commissioned “an independent, impartial, effective and prompt investigation” into Hong Kong police’s use of force during the 2019 protests, as the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, and others have advocated. The government claims that the existing police complaints mechanism, in part located within the police department and answerable to the police hierarchy, is adequate.

Unsurprisingly, that mechanism’s report into the 2019 protests found few substantiated allegations and no major wrongdoing on the part of the police. In a December 2019 investigation by the Washington Post, policing experts from around the world examined dozens of instances of Hong Kong police use of force during the protests and concluded that officers often violated their own internal guidelines, and that in some cases, the use of force was disproportionate and excessive. Another independent foreign policing expert, Prof. Clifford Stott, who was invited by the Hong Kong government to be part of its investigation but quit after he concluded that the mechanism had no real power, subsequently published his own analysis concluding that the Hong Kong police’s indiscriminate use of force escalated the 2019 protests.

In November 2020, the Hong Kong High Court ruled that the government had violated the city’s Bill of Rights by not providing an independent mechanism for complaints about police. The Hong Kong government has so far not taken any action to remedy the situation, while Chinese government-owned news outlets have attacked the judgment as wrong.

No police officers alleged to have used excessive force during the 2019 protests have been held accountable. The Hong Kong government has also obstructed efforts to hold them accountable by arbitrarily arresting people for uncovering or reporting police abuses. Hong Kong police put out an arrest warrant for a woman after she reported that she had been raped by the police during the 2019 protests. Police, who had not completed their investigation into the case, announced publicly they sought the woman for “giving a false statement.” The police are also investigating another woman for “riot[ing]” after she was blinded in one eye reportedly by police bean bag rounds.

Some top officers implicated in abuses in 2019 have even been awarded with highest government honors for their “service to the community.” The Hong Kong government is also considering a new law to criminalize “insulting public officers,” following calls for it do so by police unions and pro-Beijing politicians, which will further enable police impunity.

In mainland China, public security spending data has been a useful indicator of repression, especially in minority areas. In Hong Kong, the government added a new line item in the 2021-2022 budget: “safeguarding national security,” with a price tag of HK$8 billion (US$1 billion). The government has so far given few details about how it intends to spend this money, stating that it is “secret.” This new security spending comes on top of a HK$25.8 billion (US$3.3 billion) budget for policing, a 25 percent increase compared to the 2020-2021 budget.

Politicizing Education

Beijing also has been more aggressively infusing its ideology into Hong Kong’s education system and purging it of pro-democracy content since the imposition of the National Security Law. While this is perhaps unsurprising given the prominent role of young people in the recent wave of pro-democracy activism in Hong Kong, the consequences may be far-reaching.

Hong Kong teachers with pro-democracy views now have to be especially careful what they say in class and on social media. Pro-Beijing politicians have encouraged students and others to inform on teachers with pro-democracy views. Since June 2020, education authorities have disqualified two teachers for discussing Hong Kong independence in class; six more were fired after having been criminally charged for their involvement in the 2019 protests. Authorities have also given out warnings of “professional misconduct” to dozens of others who participated in the 2019 protests or who have publicly expressed pro-democracy views, dimming teachers’ career prospects. In one case, an art teacher lost his job after education authorities gave him a misconduct warning for his political drawings—which criticized police abuse and other rights violations in Hong Kong—because they were “unreasonable accusations” against the government.

The secretary for education has banned the 2019 protest anthem, “Glory to Hong Kong,” on school grounds. In September 2020, under the guise of providing “professional consultation” to textbook publishers, education authorities imposed a new vetting mechanism for secondary school humanities textbooks. One result has been the removal or reduction of content in textbooks on topics such as civil disobedience, police abuse, and the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre. Education authorities have also required that schools teach children about the National Security Law. In April, they instituted a National Security Education Day in all schools. Such “education” involved having children use toy machine guns in a model of Hong Kong subway train—one of the most infamous scenes during the 2019 protests was of police beating and pepper spraying protesters and commuters, and pointing guns at them in a subway train—and teaching students to accept the Chinese government’s definition of national security.

Shutting Down Funding for Protesters

The Hong Kong government has shut down several crowdfunding initiatives and arrested their organizers for raising money to help those arrested during the 2019 protests. Spark Alliance, a group that has helped those arrested with bail money and lawyers’ fees, had their funds (HK$70 million) frozen by the Hong Kong police in December 2020. Hong Kong police also arrested four organizers for “money laundering.”

Pro-Beijing newspapers and lawmakers have also recently criticized the 612 Humanitarian Fund, run by well-known pro-democracy leaders in the city, including Margaret Ng and Cardinal Joseph Zen, signaling potential police action. Police said they will investigate whether the fund constitutes money laundering and is a violation of the NSL.

Recommendations

To Concerned Governments

Multilateral Actions

Work with like-minded governments in international forums to promote and defend the human rights of Hong Kong’s people.

- Support the call by 50 United Nations human rights experts to establish a special mandate at the UN Human Rights Council to monitor and report on human rights conditions across China, including Hong Kong;

- Impose coordinated and targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on Chinese and Hong Kong government officials responsible for, engaging in, providing support for, or promoting human rights violations;

- Challenge impunity for Hong Kong police credibly alleged to have used excessive force in the 2019 protests by creating an independent review of those cases by experts outside the territory but with significant input by those knowledgeable about the events; and

- Continue to issue coordinated public statements expressing concern about the erasure of human rights in Hong Kong and calling on the Chinese government to repeal or revise all laws that violate international human rights law, including the National Security Law.

Regarding Civil Society

In consultation with the relevant Hong Kong communities, provide support to Hong Kong people to maintain their independent civil society, language, culture, and identity inside and outside the territory.

- Ensure that people in the Hong Kong diaspora can engage in protests and other forms of peaceful political actions without fear by:

- Investigating and appropriately prosecuting those who intimidate, harass, and otherwise take unlawful action against Hong Kong activists;

- Criminalizing the unauthorized collection by the Chinese government of information on refugees and asylum seekers; and

- Assisting, in particular, the digital capacity and security of Hong Kong and diaspora groups, including by providing funding;

- Allow Hong Kong people to identify themselves as such on government forms, including in population census surveys, so as to better allocate resources to support them; and

- Support Cantonese language study as part of Chinese language offerings at all educational levels. Conduct a review of educational materials to ensure that they are not censored by Chinese government and Hong Kong authorities.

Regarding Free Speech and Access to Information

- Assist Hong Kong people to contribute to the documentation of ongoing human rights abuses, including documenting websites now blocked by Hong Kong authorities;

- Support Hong Kong diaspora communities to launch independent news and information services;

- Make books now banned in Hong Kong publicly available, either as virtual or physical copies in libraries outside Hong Kong;

- Help archive and publicize materials, including slogans, artworks, and political content, that are now banned or deleted in Hong Kong; and

- Engage with domestic universities that have relationships with Hong Kong universities to explore ways to promote and protect the academic freedom of Hong Kong people, including creating opportunities at these universities for pro-democracy academics and students who have been forced out of Hong Kong universities.

Regarding Businesses

- Assess whether domestic companies that do business in Hong Kong have come under scrutiny by Hong Kong authorities in the context of the National Security Law and ensure that these companies carry out human rights due diligence and, where necessary, provide remediation; and

- Adopt legislation requiring financial transparency with Hong Kong government agencies and actors.

Regarding Law Enforcement

- Adopt and enforce vetting for any cooperation with the Hong Kong Police Force to ensure those members of the security forces are not credibly alleged to have engaged in human rights violations; and

- Ensure that no National Security Police from Hong Kong are included in any bilateral exchanges.

Regarding Judicial Independence

- Track and publicly criticize instances of inappropriate political pressure on the Hong Kong judiciary.

Regarding Elections

- Publicly criticize LegCo election processes that would deny citizens of Hong Kong the right to choose their government and that are inconsistent with international standards for free and fair elections;

- Ensure that former LegCo members demonstrably committed to democracy are included in high-profile meetings such as the Summit on Democracies; and

- Provide technical and other support to those interested in establishing democratic governance, including among members of the diaspora.

Regarding Emigration to the United Kingdom

- Allow elderly parents to emigrate with British National (Overseas) passport holders as traditional Hong Kong culture considers them as part of the family unit.

To National Parliaments

- Support former pro-democracy LegCo members through formal invitations to meet and other means; and

- Organize a global day to commemorate the Tiananmen Massacre on June 4, since Hong Kong authorities will no longer allow such commemorations.

To Businesses

- Cease business activities that directly contribute to serious human rights violations; and

- Assess whether goods and services produced contribute to serious human rights violations, and cease providing those that will likely be used for such purposes, in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

![A woman who received an eye injury during a protest on August 11, 2019, reportedly due to police bean bag rounds. Her injury galvanized subsequent protests, with protesters wearing eye patches to protest against police violence. Pro-Beijing press has since cast doubt about her accounts, while police said they were investigating her for “riot[ing].](/sites/default/files/media_2021/06/202105hongkong_national_security_law_police.jpg)