“No Answers, No Apology”

Police Abuses and Accountability in Malaysia

Glossary

|

AG AGC |

Attorney General |

|

ASP |

Assistant Superintendent of Police |

|

CID |

Criminal Investigation Division |

|

CPC DAP |

Criminal Procedure Code Democratic Action Party |

|

DDA |

Dangerous Drugs (Special Measures) Act 1985 |

|

DBKL |

Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur, Kuala Lumpur City Hall |

|

EAIC |

Enforcement Agency Integrity Commission |

|

EO |

Emergency (Public Order and Prevention of Crime) Ordinance 1969 |

|

FRU |

Federal Reserve Unit |

|

IGP |

Inspector General of Police |

|

IGSO |

Inspector General Standing Order |

|

IPCMC |

Independent Police Complaints and Misconduct Commission |

|

ISA |

Internal Security Act |

|

LRT |

Light Rail Transit |

|

MACC |

Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission |

|

MMC |

Malaysian Medical Council |

|

MOU |

Memorandum of Understanding |

|

NFA PCA |

No Further Action Prevention of Crime Act 1959 |

|

PAS PDRM |

Parti Islam Se-Malaysia, Pan-Malaysia Islamic Party Polis Diraja Malaysia, Royal Malaysia Police |

|

PRS |

Police Reporting System |

|

RELA |

Ikatan Relawan Rakyat Malaysia, Malaysian People’s Volunteer Corps |

|

RM |

Malaysian Ringgit (RM 1 equals US$0.30) |

|

RMP |

Royal Malaysia Police |

|

SDR |

Sudden Death Report |

|

SOP |

Standard Operating Procedure |

|

SOSMA |

Security Offenses (Special Measures) Act |

|

Suhakam |

Suruhanjaya Hak Asasi Malaysia, Malaysian Human Rights Commission |

|

UMNO |

United Malay National Organization |

Map of Malaysia

Summary

I ask Allah how my son felt when he saw a gun at his forehead, knowing he was about to die. Was he crying, screaming, “Don’t kill me?”

—Norhafizah, mother of Mohd Shamil Hafiz Shapiei, 15, killed by police in 2010, Kuala Lumpur, April 2012

There is stiff resistance from police when anyone questions them. When we inquire about a case, the police tell us that it’s under investigation and everything is done according to procedures, but we are not given their SOPs [standard operating procedures] or ever told what their investigation found. “Trust us,” they say, “We are taking care of it.” But people want tangible proof of what action they take which is nowhere to be seen. There are no checks and balances.

—Investigator at the Malaysian Human Rights Commission (SUHAKAM), Kuala Lumpur, May 2012

Police abuse remains a serious human rights problem in Malaysia. Unjustified shootings, mistreatment and deaths in custody, and excessive use of force in dispersing public assemblies persist because of an absence of meaningful accountability for Malaysia’s police force, the Royal Malaysia Police (RMP). Investigations into police abuse are conducted primarily by the police themselves and lack transparency. Police officers responsible for abuses are almost never prosecuted. And despite recent reforms, there is still no effective independent oversight mechanism to turn to when police investigations falter. The result is heightened public mistrust of a police force that has engaged in numerous abuses and blocked demands for accountability.

This report examines more than 15 cases of alleged police abuse in Malaysia since 2009, drawing on first-hand interviews, complaints by victims or their families, and news reports. In only a handful of cases has the Malaysian government conducted serious investigations and held accountable those responsible. Government statistics provided to Human Rights Watch show that the majority of prosecutions of the police are for corruption and drug-related offenses and not deaths in custody, ill-treatment, or excessive use of force.

The Royal Commission to Enhance the Operation and Management of the Royal Malaysia Police (the “Royal Commission”), established in 2004 by the Malaysian king (Yang di-Pertuan Agong), raised serious concerns about police abuses. The Royal Commission received over 900 complaints of abuse including deaths in custody, physical and psychological abuse of detainees, misuse of administrative detention laws, abuse of power, and systematic lack of accountability and transparency. In 2005, the Royal Commission issued its report with 125 recommendations, including that the government amend relevant laws to make them comply with international human rights standards, and take steps to eradicate corruption, enhance investigative policing, and improve police support and maintenance through measures such as better housing and salaries for the police. In order to systematically address the lack of accountability for abuses, the Royal Commission recommended the establishment of an Independent Police Complaints and Misconduct Commission (IPCMC) to investigate police malfeasance and take disciplinary measures.

The government implemented many of the Royal Commission’s recommendations. But it rejected the recommendation that it create an external accountability mechanism, partly because the government came under intense police pressure not to create an oversight agency solely focusing on the police. Instead the government established the Enforcement Agency Integrity Commission (EAIC), which oversees 19 government agencies including the police. The EAIC has been operating since April 2011, and received a total of 469 complaints through May 31, 2013, of which 353 were against the police. The commission is thinly staffed—the number of staff investigators dipped to only one in mid-2013—and it has insufficient resources to investigate and respond to complaints. In the words of an EAIC investigator, the commission is “being set up to fail.” Speaking to a national conference in May 2013 organized by the EAIC, former Chief Justice Tun Abdul Hamid Mohamad took the EAIC to task, saying, “The bottom line is, since its establishment until the end of 2012, only one disciplinary action and two warnings have been handed down. For a budget of RM14 million [US$4.2 million] for the two years, they were very costly indeed.”

The absence of accountability facilitates rights-abusing and at times deadly police practices. The lack of a robust and independent oversight system also harms relations between police and the general public. Effective law enforcement depends on cooperation with and information from the community. Rights abuse diminishes public confidence and trust in the police and leads to less effective law enforcement.

Police officers have the responsibility to take steps to prevent crime and apprehend criminal suspects, and mistakes can happen when they make split-second decisions regarding the use of force. Even the best training, equipment, and leadership will not result in flawless behavior by the police. But Human Rights Watch research found problems much more significant than mistakes or a few ineffectual officers. The serious rights abuses documented in this report point instead to structural problems that need to be addressed. Without rigorous investigation of alleged police abuse cases, those problems cannot be properly identified or tracked. Despite increasing public backlash, neither police leaders nor the civilian authorities who oversee their actions have made a genuine commitment to bringing about needed reform in police policy and practice.

Vague policies, substandard training, lack of transparency, and failure of leadership to investigate and prevent illegal practices all create opportunities for abuse. Unfortunately the Malaysian government and the Inspector General of Police (IGP) have abdicated their responsibility by not making the necessary policy changes to ensure effective oversight and accountability in cases of alleged wrongful deaths, mistreatment in custody and excessive use of force. By failing to ensure that the police cooperate with oversight bodies such as the Malaysian Human Rights Commission (Suruhanjaya Hak Asasi Malaysia, SUHAKAM) and the Enforcement Agency Integrity Commission (EAIC), or to establish a specialized independent police investigatory body as recommended by the Royal Commission, the government has allowed the Royal Malaysian Police to remain effectively unaccountable for serious abuses.

* * * *

International legal standards restrict the intentional lethal use of firearms by law enforcement officers to those situations when it is strictly unavoidable to prevent loss of life or serious injury to themselves or others. However, the wide-ranging use of official secrecy laws in Malaysia makes it impossible to determine whether and to what extent the Royal Malaysian Police recognize these parameters on use of force. The IGP standing order on use of force and firearms, for example, is considered a state secret and therefore not publicly available. Human Rights Watch’s request to review the order was denied.

Deputy Inspector General of Police Khalid bin Abu Bakar (who became the inspector general on May 17, 2013) told Human Rights Watch in May 2012 that lethal force is used for “self-protection . . . if police are threatened with death [and] there is no time to use a less lethal weapon.” Yet cases examined by Human Rights Watch show that police shot at suspects when police use of force was not warranted and strongly suggest that the police are not adequately trained to use less-than-lethal force when facing threats to themselves or to public safety.

A parang (machete). © 2013 Lawyers for Liberty

While police shootings may sometimes be lawful, reported incidents of police shootings show a pattern in which police justify shootings by asserting the suspect had a parang (a machete commonly used as an agriculture tool) or failed to stop at a roadblock or after a car chase. In some cases, the police also attempt to justify their use of lethal force by alleging that the suspect was a criminal associated with ongoing police investigations. Wholly absent from police narratives is any attempt to demonstrate that lethal use of force was the only available option to save lives at imminent risk. The apparent quick resort to lethal force raises serious concerns about the police’s standard operating procedures and training in the use of lethal force. In many cases investigated by Human Rights Watch, the police version of events was completely at odds with the accounts of witnesses and victims who said the victim was unarmed or did not threaten police.

For example, on August 21, 2012, two people saw plainclothes police shoot an unarmed man, Dinesh Darmasena, 26, at night in a Kuala Lumpur suburb. Darmasena died two days later. The police alleged that Darmasena was a gang member and that he and his friends attacked the police with parangs. Yet witnesses filed police complaints, at personal risk to their own safety, saying that Darmasena was unarmed and otherwise contradicting the police version.

In November 2010, police shot and killed Mohd Shamil Hafiz Shapiei, 15, Mohd Hairul Nizam Tuah, 20, and Mohd Hanafi Omar, 22, at approximately 4 a.m. in Selangor. The police alleged that the three were robbing a petrol station and that they then charged at the police with parangs, forcing the police to shoot them. All three sustained gunshot wounds to the forehead and chest. The post-mortem report on Shapiei found gunpowder residue on his clothes and concluded that the bullets entered his body at a trajectory angle of 45 degrees, suggesting he had been shot at very close range and not at a distance, as would have been the case had he been charging the police with a parang.

Mohd Afham bin Arin, 20, was fatally shot by the police following a motorcycle chase on the night of October 19, 2010, in Johor Baru. The police claimed that Afham waved a parang at them and that the passenger, Firdaus, riding behind him also threatened police with a sword. Firdaus filed an official statement with the police rebutting the allegations. The police never charged the Firdaus with any offense related to the incident and conducted no further investigation into the shooting.

The discrepancies between police and witness accounts raise concerns that the police in some instances may be falsely asserting that the victim wielded a parang in attempts to justify police use of lethal force. Even dubious police accounts get cemented into the public record, however, because police have greater access to the media and because it is almost always police themselves—often from the same police station as the allegedly abusive officers—who investigate the allegations of abuse. This is all the more reason why an effective independent oversight mechanism is essential.

According to the Ministry of Home Affairs, which oversees the 112,000-member police force, 147 people died in police custody between January 2000 and February 2010. Just three years later, information received in the Parliament on June 26, 2013, from the government in response to MP’s questions revealed a total of 231 deaths in custody between the year 2000 and May 2013.

Inquests into wrongful deaths are mandatory under the Malaysian Criminal Procedure Code, but our examination of cases since 2009 shows that a sustained public outcry about a custodial death is often needed before officials will order an inquest. The Royal Commission in 2005 raised similar concerns about police failure to conduct inquests when required by law.

Government officials typically rely on post-mortem examinations by government pathologists that establish the proximate cause of death, but typically do not address serious questions such as whether the death was a result of police mistreatment or could have been prevented with timely medical care.

For example, in January 2010 Mohammad Ramdan bin Yusuf died in police custody of what the post-mortem examiner found to be cardiac arrest, with evidence of “blunt force trauma to the limbs” five days after he was arrested. The police reported that he died of cardiac arrest, but a relative who identified Ramdan’s body in the hospital saw bruise marks on his body and indications of bleeding. Despite this claim and family demands for an inquest, no inquest was held to determine the manner of death.

Victims’ families have begun questioning the reliability of government pathologists’ post-mortems and in recent years have begun requesting a second post-mortem. In the case of 23-year-old Kugan Ananthan— who died shortly after being severely beaten at the Taipan police station, in Subang Jaya, Selangor state, on January 20, 2009—the first autopsy concluded that Kugan had died of “pulmonary edema” (fluid in the lung). This conclusion was disputed by a second post-mortem, which found that Kugan’s death was caused by acute renal (kidney) failure due to blunt trauma to skeletal muscles.

The Royal Commission and local human rights organizations have also questioned the independence of police investigations in death-in-custody cases. In July 2012, the High Court of Kuala Lumpur raised serious concerns regarding the impartiality of an investigation conducted by police officers affiliated with the lockup where the death of a detainee occurred. The court recommended such investigations be conducted by police officers from a different station.

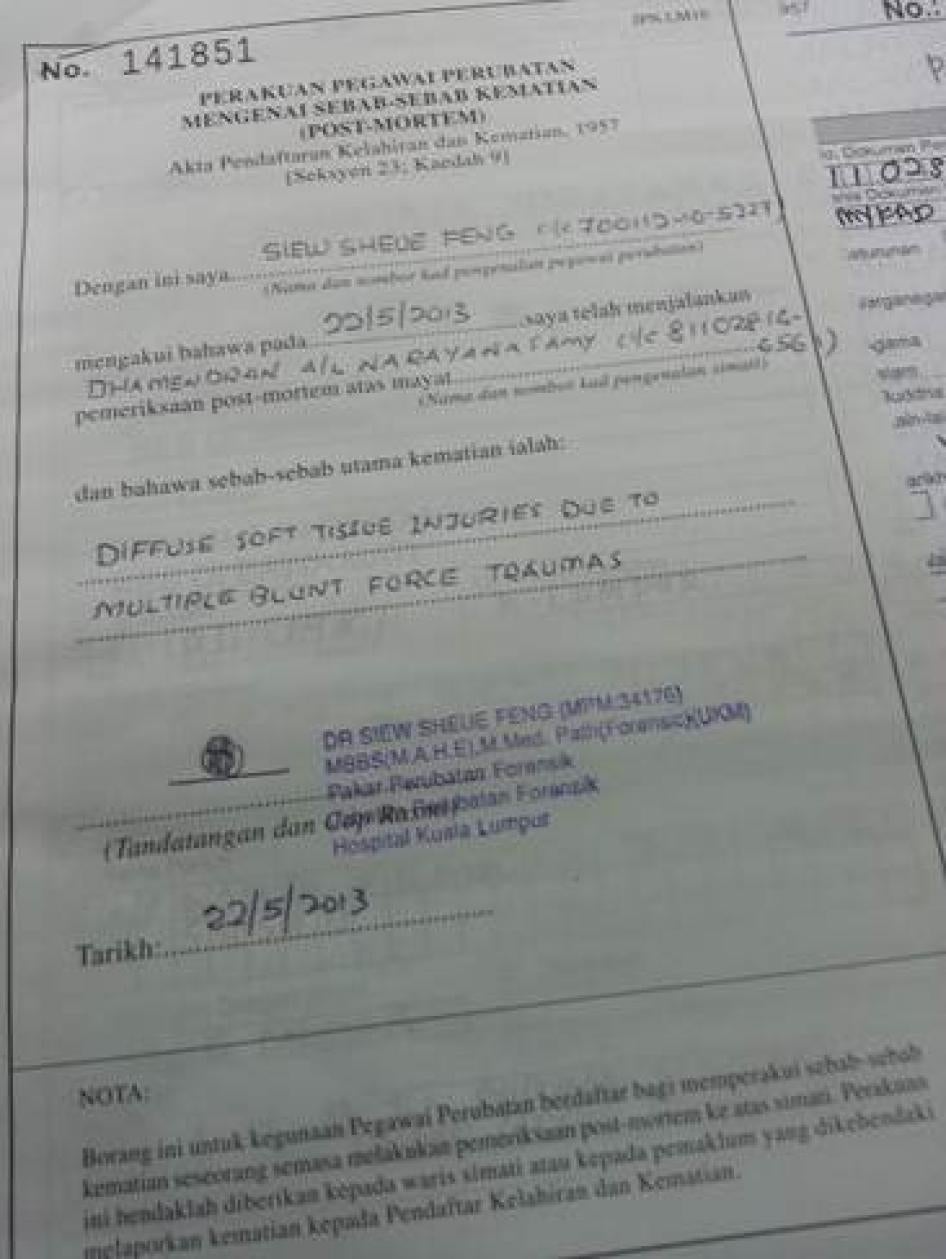

However, in the case of truck driver Dhamendran Narayanasamy who died in police custody in May 2013, significant public outcry and a clear post-mortem finding of death caused by “multiple blunt force traumas”, led prosecutors to charge four policemen with murder.

The cases we investigated also indicate that ill-treatment of persons in police custody in Malaysia remains a serious concern, and there is little recourse for those who suffer the abuse. For example, Mohammad Rahselan, 18, was forced by the police to squat for an hour, do spot jumping, and “walk like a duck” with arms crossed and hands behind his ears at a police station in Kelantan. Car mechanic S. Mogan alleged that he was kicked, beaten on his feet with a hosepipe, and threatened with a gun by a police officer at a police station in Selangor who was trying to induce him to confess to theft of a truck. Mogan filed a complaint, which the police disputed. When the wife of truck driver Dhamendran Narayanasamy visited him in police custody on May 19, 2013, he told her that he had been beaten in custody but “not serious” – two days later, he was dead from what the initial post-mortem found were “diffuse soft issue injuries due to multiple blunt force traumas” that occurred while in police custody.

Police handling of public assemblies has also been a problem. Police have frequently employed unnecessary or excessive force. Human Rights Watch observed police using teargas and water cannons against peaceful participants on April 28, 2012, at a mass rally in Kuala Lumpur organized by Bersih, the Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections. While a small group of demonstrators had attempted to breach a police barricade shortly before police moved in, the police also targeted the larger group which did not breach the barricade, severely beating and injuring demonstrators as well as several journalists who were covering the rally while special riot police fired teargas and water cannons at the retreating protesters. One protester suffered significant loss of vision after being struck in the face by a teargas canister. SUHAKAM, Malaysia’s national human rights commission, in its 2013 public inquiry concluded that “there was use of disproportionate force and misconduct by the police towards the participants.”

Victims of police abuse in Malaysia who do report abusive treatment or question the conduct of the police have little chance of seeing the police investigated, punished, or prosecuted. The police’s excessive secrecy usually means that complainants learn nothing about whether their complaint is investigated or whether any disciplinary action has been taken. “I filed a complaint about my son’s death, but I don’t know what happens next. We never hear what action the police are taking,” said Sapiah binti Mohd Ellah, mother of Mohd Afham bin Arin, shot by the police in Johor Baru in 2010. “No answers, no apology.”

Police investigative bodies in Malaysia have proven ineffectual. The IGP’s Disciplinary Authority investigates police misconduct in the areas of corruption, drugs, violations of Sharia (Islamic law), and truancy. The Criminal Investigation Division (CID) investigates police involvement in crimes as well as civilian complaints of police abuse. But in reality, the investigations are often conducted by officers from the same police station as the officers implicated in the abuse. The lack of impartiality of police investigators, as well as an institutional culture that does not take abuse complaints seriously, undermines police inquiries in such cases. Yet neither the IGP nor the civilian leadership of the Ministry of Home Affairs has taken steps to remedy this situation.

According to RMP statistics provided to Human Rights Watch, 4,334 police misconduct cases were logged with the CID from January 2005 to May 2012. A total of 32 percent of these cases were referred to the Attorney General’s Office for prosecution, and of those referred only one-quarter were actually prosecuted in court. Another 23 percent of the cases referred to the Attorney General’s Office were deemed to require “no further action” because of “lack of evidence.” The remaining 68 percent of the 4,334 cases were still pending investigation by the police, including some that were opened as far back as 2005.

The types of cases referred by the RMP for prosecution often involve drug-related offenses, corruption, extortion, or robbery. But even these numbers do not provide much clarity, including because they do not distinguish between cases in which civilians complain of police abuse, and cases of police corruption and other crimes.

As with inquests, it appears that significant public attention and outrage are critical in determining whether a case of alleged police abuse will be seriously investigated. Even when they are, prosecutions are the exception and tend to focus on low-level officers. And, as indicated by the two recent cases summarized immediately below, the convicted police officers sometimes effectively avoid punishment for their crimes.

In April 2010, police fatally shot 15-year-old Aminulrasyid bin Amzah while he was driving his car in Shah Alam, Selangor. Public outrage at the death of a student prompted a government inquiry into the IGP standing order on use of force and firearms. The government inquiry resulted in an amendment to the standing order, but the inquiry findings were never made public. Corporal Jenain Subi was charged, convicted, and sentenced in 2010 to five years in prison for culpable homicide. However, the IGP Disciplinary Authority did not investigate him because, according to the authority’s head, “[Subi’s] actions were not inconsistent with [the standing order]. He was prosecuted because of public sentiment.” In December 2012, the court of appeals acquitted Subi and released him.

Similarly, while twelve police officers were suspended for beating to death Kugan Ananthan in police custody in January 2009, only one officer, police constable Navindran Vivekandan, was tried and convicted. He received a three-year-sentence which has been stayed pending an appeal that was still ongoing as this report was published. Kugan’s family also filed a civil court case seeking damages, which they won on June 26, 2013, when a judge awarded them damages of RM 851,700 (US$266,156) and cited that actions by senior police officers in the case made them liable to charges of malfeasance. The government immediately appealed the civil court verdict.

Victims of police abuse and their families can also file civil lawsuits. According to the Attorney General’s Office, between January 2009 and June 2012, Malaysian courts awarded approximately RM3 million (US$965,000) in damages in 30 cases to victims of negligent shooting, assault and battery, and unlawful arrest and detention. But the ability to seek redress through civil suits has been weakened by a 2009 Federal Court decision in Kerajaan Malaysia v. Lay Kee Tee, which has been interpreted to require plaintiffs to name the specific government officials allegedly responsible for the abuse. This is often impossible because, as many victims told Human Rights Watch, police often do not wear identification nametags while on duty. In July 2012, the civil suit of Shahril Azlan, who survived gunshots by plainclothes police at a roadblock in 2009, was dismissed by the Kuala Lumpur High Court because Azlan could not name the individual police officers involved. While the court of appeals reinstated the case on January 15, 2013, at this writing a year later Shahril was still waiting for justice at a new trial at the High Court.

As noted above, a fundamental problem is that Malaysia lacks an independent oversight mechanism focused solely on the police, despite the recommendation of the Royal Commission that such a body be set up. The Enforcement Agency Integrity Commission (EAIC) was established by law to investigate misconduct at 19 government agencies, a nearly impossible task. The EAIC, moreover, is woefully understaffed and police have been reluctant to cooperate with the commission, such as by providing investigators with basic information, including the text of relevant IGP standing orders. In June 2013, the EAIC announced it was forming a task force to investigate the deaths in custody of Dhamendran Narayanasamy and R. Jamesh Ramesh, but at the time of publication of this report, it had not made any findings public.

SUHAKAM has also received complaints of police misconduct such as excessive use of force, abuse of power, and deaths in custody, and it has faced similar obstacles in trying to deal with the police. Police have withheld relevant IGP standing orders and have been unwilling to provide police investigation files on cases that SUHAKAM is investigating. These delay-and-deny tactics by the police in response to document requests hobble the commission’s work. The police also continue to dismiss SUHAKAM’s findings and recommendations in cases of police abuse that it investigates. By any measure, the current oversight system is failing.

Malaysia is obligated to prevent the commission of human rights violations such as extrajudicial killings and torture by state officials and agents, and to hold those responsible to account. As a member of the United Nations, Malaysia has agreed to uphold the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which is considered reflective of customary international law. The Universal Declaration protects the right to life and security of the person, including from torture, and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment. It provides that everyone has the right to an effective remedy for violations of fundamental rights.

Malaysia also has an obligation under international law to conduct prompt, thorough, and impartial investigations into allegations of serious human rights violations, and to ensure the appropriate prosecution of those responsible. Victims and their families have the right to appropriate redress. When existing law enforcement mechanisms fail to meet these obligations in the face of alleged abuses by the police or other state agencies, it is incumbent upon the government to ensure there are effective and independent oversight mechanisms to address and rectify these problems.

Malaysia has persistently failed to investigate and prosecute alleged police abuse, provide redress for victims, and ensure that existing oversight mechanisms are able to intervene to meet these obligations.

The Royal Malaysia Police should ensure that officers are punished when they violate administrative rules, and the Attorney General’s Office should ensure that all serious allegations of police abuse cases are investigated and, as appropriate, prosecuted.

Police should also be accountable to the public and should demonstrate that their policies and practices conform to international human rights standards. External pressure and oversight are important in improving accountability, and police leadership and effective supervision are critical to preventing abuse and misconduct. Police officers take an oath to “obey, uphold and maintain the laws of Malaysia.” The motto of the Royal Malaysia Police is “Tegas, Adil and Berhemah” (Firm, Just and Well-Mannered). Both the oath and motto should be fully complied with by every police officer in Malaysia—as this report shows that is not the case today. The RMP leadership needs to ensure constant vigilance, clear and consistent enforcement of departmental policies, and a genuine commitment to end police abuse.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Malaysia

- Create an independent, external commission tasked solely to receive and investigate complaints about RMP misconduct and abuse, and endow the commission with all necessary powers to investigate, compel cooperation from witnesses and government agencies, subpoena documents, and submit cases for prosecution.

- Until an external commission is established

with a sole focus on RMP misconduct and abuse, reform the Enforcement Agency

Integrity Commission (EAIC) to improve its performance by:

- Establishing an appointment procedure and process that guarantees the independence and impartiality of the commissioners.

- Establishing criteria that commissioners and senior staff have relevant experience in monitoring and investigating human rights abuses.

- Ensuring transparency and timely public disclosure of information about the complaints received and investigations conducted by the EAIC, and

- Ensuring that the EAIC has adequate investigators, resources and personnel to fulfill its mission.

To the Inspector General of Police

- Create an RMP Ombudsman’s office that is empowered to receive and follow up on complaints of police abuse, with authority to take disciplinary action against RMP officers who obstruct or otherwise fail to cooperate with investigations.

- Provide all IGP standing orders on use of force and firearms, procedures for arrest, procedures for investigations, procedures for deaths in lock-ups, to external oversight bodies, including SUHAKAM and the EAIC, and engage with those bodies to bring these standing orders into compliance with international human rights standards.

- Issue an IGP standing order that instructs police stations across Malaysia to fully cooperate with external oversight agencies investigating police conduct by providing access to police files, police witnesses, and other requests for evidence.

The full set of Human Rights Watch’s recommendations can be found at the end of the report.

Methodology

Research for this report was conducted in Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, Johor, Kelantan, and Perak in Malaysia in April and May 2012 and May 2013, supplemented by telephone, email, and desk research through January 2014. Human Rights Watch interviewed 75 people for this report including victims of police abuses and their family members, lawyers, police officials, public prosecutors, and staff members of the Enforcement Agency Integrity Commission, SUHAKAM, the Malaysian Bar Council, and other nongovernmental organizations. Human Rights Watch received verbal consent from all interview subjects and participants did not receive any material compensation for their participation.

In cases where the victim had died, we interviewed their relatives, and reviewed available documents such as police reports filed by complainants, death certificates, autopsy reports, and court papers. Most interviewees gave permission to use their names. However, in cases where the interviewee feared reprisal, Human Rights Watch has used pseudonyms and has so indicated in the text and relevant citations.

We obtained data on deaths in police custody, police shootings, and disciplinary actions, criminal prosecutions, and civil suits filed against police from both official sources including the Attorney General’s Office and the Inspector General of Police Office, as well as from media reports. Analyzing police data is challenging as the RMP does not maintain detailed statistics on the types of public complaints it receives. As discussed in the report, the RMP apparently does not distinguish investigations of police involvement in crimes from civilian complaints of police abuse or misconduct. Outside entities including SUHAKAM, local human rights organizations, and Human Rights Watch have also been denied copies of relevant standing orders from the Inspector General of Police, impeding external assessment of the policies and procedures of the Royal Malaysia Police.

All documents cited in the report are publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch.

I. The Royal Malaysia Police

A key challenge for the Royal Malaysian Police is to regain the good image it enjoyed during the period of the 1960s to 1980s, an image that has been seriously undermined in the last decade due to mounting public perceptions of corruption and abuse of power in PDRM [Polis Diraja Malaysia or Royal Malaysia Police].

—Report of the Royal Commission to Enhance the Operation and Management of the Royal Malaysia Police, 2005

The Royal Malaysia Police (RMP) dates back to 1807 when the force was created under British colonial rule. Following Malaysian independence in 1957, the police force expanded. The police played a major role in the counter-insurgency campaign against a communist insurgency during the Malayan Emergency of 1948-1960 and was responsible for internal security and public order.[1]

Under the Police Act of 1967, the functions of the Royal Malaysia Police are the “maintenance of law and order, the preservation of the peace and security of the Federation, the prevention, and detection of crime, the apprehension and prosecution of offenders, and the collection of security intelligence.”[2] To carry out its function, the police are empowered to arrest, search, seize, and investigate as set out in the Criminal Procedure Code. The Inspector General of Police (IGP) is empowered to issue standing orders (day-to-day operational procedures) related to specific police functions.

The current RMP is a 112,145-member police force responsible for everything from traffic control to intelligence gathering and is composed of eight specialized law enforcement departments.[3] It is a federal institution and its headquarters in Kuala Lumpur is Bukit Aman from where the IGP directs operations in 14 regions and 148 police districts across the country. The IGP reports to the Minister of Home Affairs.

The evolution of the RMP has been shaped largely by its role in maintaining Malaysia’s national security, in addition to its law enforcement and crime prevention functions. Malaysian police have for years relied on their power to use administrative detention to detain suspects without having to present evidence of wrongdoing before a court.

Until recently, those laws included the Internal Security Act (ISA)[4] and the Emergency (Public Order and Prevention of Crime) Ordinance (EO).[5] These laws allowed the police to hold individuals in detention for 60 days. Upon expiration of the 60-day period, the Minister of Home Affairs could authorize administrative detention, solely based on police recommendations, for two years for persons deemed to be a threat to national security, suspected of crime, or involved in trafficking. The two-year detention periods could be renewed indefinitely and the grounds for detention could not be challenged in court. The Dangerous Drugs (Special Measures) Act (DDA), which authorizes administrative detention, is still in effect.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Malaysian government used the ISA to suppress political activity, such as the Labor Party of Malaysia and the Party Sosialis Rakyat Malaysia (PSM). Approximately 3,000 persons were administratively detained between passage of the ISA in 1960 and the assumption of power by then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed in 1981. Mahathir used the ISA extensively to imprison political opponents and human rights activists, with the most prominent example being Operation Lalang in October and November 1987, through which the government detained 106 human rights advocates and political activists fromthe major political parties, including the United Malay National Organization (UNMO), the Pan-Malaysia Islamic Party (Parti Islam Se-Malaysia, PAS), and the Democratic Action Party (DAP). Mahathir also oversaw at this time the amendment of the ISA to include provision 8(b) that eliminated the possibility of judicial review of ISA decisions. Other high profile political uses of the ISA included Mahathir’s 1999 use of the law to detain his former deputy (and now leader of the political opposition) Anwar Ibrahim and the 2001 use of the law against senior political activists in KeADILan who were publicly demanding Anwar’s release.[6]

Malaysian and international human rights organizations, SUHAKAM, and the Royal Commission have long documented abuses stemming from administrative detention in Malaysia.[7] The lack of judicial scrutiny of the detentions, complaints of police abuse, and lack of transparency and accountability have engendered greater distrust of the police among civil society groups.

After many years of domestic and international criticism, the ISA and the EO were repealed by the Parliament in April 2012. In their place, parliament passed a new law, the Security Offenses (Special Measures) Act (SOSMA). SOSMA limits police detention to 28 days after which the attorney general must either prosecute or release the defendant. Should the government take a person to trial under SOSMA and the defendant be acquitted, the law empowers the government to continue to detain the defendant during the appeals process.[8]

On October 2, 2013, the government enacted amendments to the Prevention of Crime Act 1959 (PCA) that provide for administrative detention of persons suspected of involvement in “serious crimes.” Specifically, the amendments allow for renewable detention for up to two years without trial if the authorities determine that it is in the interests of “public order,” “public security,” or “prevention of crime”—terms not defined—and a three-person “Prevention of Crime Board” finds that the person has committed two or more serious offenses “whether or not he is convicted thereof.”[9]

Years of being able to detain people without charge or trial under the administrative detention laws appears to have had a devastating impact on the investigative abilities of the police. Not having to present evidence to support an allegation in an independent court where it could be challenged by defendants and their lawyers has inhibited the police from investing in and emphasizing modern investigative policing. Razi M. (pseudonym), a former official of the Criminal Investigation Division, who was based at police headquarters in Bukit Aman, told Human Rights Watch: “The EO and ISA have made the police lazy as they don’t have to gather evidence that needs to be submitted in a court.”[10] The Royal Commission also noted the need for police to improve intelligence-led and evidence-based systems and not rely on “preventive laws” for detention of suspected criminals.[11]

When asked how the police will handle criminal cases in absence of the EO, then Deputy Inspector General of Police Khalid bin Abu Bakar responded, “Because we no longer have preventive laws, we need to be innovative. We have no choice but to bring suspects to court. We now need to gather evidence. We need new laws to make our job easier to solve crimes.”[12] Prime Minister Najib Razak in July 2012 echoed similar concerns and conceded that, “Now police must train themselves to look for evidence.”[13] Dennison Jayashooria, a former member of the Royal Commission, told Human Rights Watch, “Good criminal investigation is essential to ensure there is no miscarriage of justice. This should be a top priority in police reform. . . The Royal Commission report sets out details on improving investigation, but the police resist outside critiques.”[14]

Royal Commission on Police Reform

In 2004, the Royal Commission to Enhance the Operation and Management of the Royal Malaysia Police (the “Royal Commission”) was established by the Malaysian king in response to “widespread concerns regarding the high incidence of crime, perception of corruption in the Royal Malaysia Police,… general dissatisfaction with the conduct and performance of police personnel, and a desire to see improvements in the service provided by the police.”[15] The government also asked the Royal Commission to assess RMP capacities and facilities.[16]

Over a 15-month period, the Royal Commission received 926 complaints from the public, which included deaths in custody; physical, sexual, and psychological abuse of detainees; abuse of power; inefficiency and lack of accountability; failure to follow-up on complaints; abuse of remand provisions under the Criminal Procedure Code; overuse and misuse of administrative detention laws; and police unwillingness to issue public assembly permits.[17]

The Royal Commission’s comprehensive report was made public by the government in June 2005. The report contained 125 recommendations and concluded that there are “extensive and consistent abuse of human rights in the implementation of the [Federal Constitution] and [Inspector General] standing orders by PDRM [police] personnel.”[18] The Royal Commission recommended that, “upholding human rights needs to become a central pillar of policing . . . that PDRM has to dramatically review compliance with human rights and human rights provisions inherent in the country’s law.”[19] The report recommended the need to “review some of the laws, rules, and regulations affecting policy to strengthen the safeguards prescribed by international human rights instruments and the Federal Constitution.”[20] The report unequivocally recommended that “the culture of impunity” needs to be discarded and effective internal and external mechanisms for accountability should be established to provide a check on abuses, and build a culture of accountability.[21]

The Royal Commission’s recommendations included improving housing and salaries of the police, technological improvements, eradicating corruption, repealing and amending Malaysian laws to make them consistent with international human rights law, improving facilities for women and children, enhancing investigative policing, and establishing an Independent Police Complaints and Misconduct Commission (IPCMC).[22]

To the credit of the Malaysian government, many of those recommendations have been implemented.[23] For instance, the government allocated funds to the RMP to overhaul its technological equipment, increase community policing, set up new and rehabilitate old police stations, increase salaries, and improve police housing facilities.[24] In 2010, the government announced further increases to police salaries.[25] Improving housing and salaries of the police is a factor in reducing incentives for bribes. But according to former commissioner Dennison Jayashooria, key recommendations have not been implemented, including improving the investigative capabilities of the police and creating effective external accountability mechanisms.[26]

The Royal Commission’s recommendation to create an independent police commission was widely supported by over 300 civil society organizations, including Suaram and the Malaysian Bar Council, and by the national human rights commission, SUHAKAM.[27] Then-Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi also expressed initial support for such a commission, claiming that 25 percent of the recommendations had been implemented and the rest would be implemented in the “short and long term.”[28] But the police fiercely opposed the creation of an independent police commission and in an internal bulletin attacked the proposed IPCMC as “unconstitutional, prejudicial to national security and public order, [capable of causing] a state of anarchy and undermin[ing] the ruling coalition's power.”[29]

Facing concerted opposition from the police, the government announced that setting up a commission solely to examine police misconduct would unfairly single out one enforcement agency. Instead, in September 2009 the government created the Enforcement Agency Integrity Commission (EAIC) to receive and investigate complaints about 19 enforcement agencies.[30] The EAIC became operational in April 1, 2011. As detailed in chapter III below, the EAIC is seriously understaffed and has inadequate resources to handle its mandate.

II. Human Rights Violations by Police

Police in Malaysia have committed wrongful killings, torture, and other ill-treatment of persons in custody, and used unnecessary or excessive force during public assemblies causing injuries and deaths. Human Rights Watch investigated cases that raise serious concerns about the still-secret IGP standing order on use of force and firearms, the lack of transparency and impartiality in police investigations, and the continued absence of meaningful accountability for police abuses.

Malaysian and International Legal Standards on Use of Force

The Inspector General of Police standing order on the use of force and firearms is not public. Authorities have repeatedly rejected requests to view the standing order by domestic and international human rights organizations, lawyers, and the Bar Council, and even the government’s national human rights commission, SUHAKAM. In October 2013, Minister of Home Affairs Ahmad Zahid Hamidi stated in a written reply to parliament that in general "the standing orders are the procedures and trade-craft of conducting PDRM's duties. It is only for the use of members of PDRM.” Zahid added that the “PDRM will only reveal certain standing orders that have a direct relation to the public.”[31]

In response to Human Rights Watch’s request to review the standing orders on use of firearms, investigations of deaths in custody, and the police Disciplinary Authority, the IGP office stated:

Your requests have been brought to the attention of the Royal Malaysia Police leadership and it was decided that all request for information by Human Rights Watch should be channel[ed] to the Malaysia Human Rights Commission (SUHAKAM). In so doing, SUHAKAM as the statutory body governing human rights matters for Malaysia would be kept in the know of all matters pertaining to human rights. It is also encourage[d] that you state the reason and purpose of your request for those [sic] info.[32]

But SUHAKAM itself has not received access to the relevant standing orders. In July 2012, SUHAKAM was provided part of the Federal Reserve Unit guidelines on use of force in relation to a SUHAKAM public inquiry into the crackdown on an electoral reform rally led by Bersih in Kuala Lumpur on April 28, 2012.

Some information on the IGP standing order on use of force and firearms can be gleaned from open sources. In 2010, the New Straits Times, citing unnamed police officials, enumerated the following IGP principles governing use of firearms:

- The suspect is believed to have committed an offense that is punishable with life imprisonment or death, e.g. murder, armed robbery, drug trafficking;

- Policemen believe that their lives are in imminent danger of serious injuries or death when apprehending or confronting a suspect; and

- Other people’s lives are in imminent danger of serious injuries or death.[33]

According to open sources, in 2010 the IGP standing order was partially amended in response to the killing of 15-year-old student Aminulrasyid Amzah by the police, which drew nationwide attention to RMP use of lethal force. The amended standing order is not public and SUHAKAM told Human Rights Watch that they have not been provided a copy of the order.

Then-Deputy Inspector General of Police Khalid bin Abu Bakar told Human Rights Watch that the standing order on the use of force and firearms is premised on “self-protection . . . if police are threatened with death there is no time to use a less lethal weapon.”[34] He further explained that when a police officer shoots and kills or injures someone, the officer must file a report describing the reasons for use of his weapon, and the gun must be sent for ballistic analysis.[35] “The police officer remains on duty and is not temporarily assigned to desk duty pending investigation,” said Khalid. When asked what other less-lethal means are used by the police, he responded, “The police use batons and is considering using pepper spray and tasers.”[36] SUHAKAM has been urging the Royal Malaysia Police to train officers in negotiation tactics, use of less-than-lethal means of force, and methods to incapacitate suspects rather than use deadly force.[37]

Police constables told Human Rights Watch that their use of firearms is in self-defense. “If a suspect has a piece of wood, no we cannot use guns. But if he has a parang or any sharp object that can lead to death we are allowed to use a gun,” said Ghani M. (pseudonym).[38] When asked which part of the body the police can shoot at to stop a person, constable Ahmed R. (pseudonym) replied without hesitation: “anywhere.”[39]

Government security forces are empowered to use force, but only in accordance with basic international standards that govern the use of force. These standards are embodied in the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials and the UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials. Together these documents provide authoritative international standards governing the use of force in law enforcement. [40]

The UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials applies international human rights standards to law enforcement. Article 3 provides that “law enforcement officials may use force only when strictly necessary and to the extent required for the performance of their duty.” The official commentary to article 3 states that national law should recognize proportionality in the use of firearms and sets out that firearms should “not be used except when a suspected offender offers armed resistance or otherwise jeopardizes the lives of others and less extreme measures are not sufficient to restrain or apprehend the suspected offender.” [41]

The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials provides that whenever the lawful use of force is unavoidable, then law enforcement officials should “exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence and the legitimate objective to be achieved.” Officials should also “minimize damage and injury, and respect and preserve human life.”[42] Governments should ensure that arbitrary or abusive use of force and firearms by law enforcement officials is punished as a criminal offense under national law.[43] The training of law enforcement officials should include “police ethics and human rights, especially in the investigative process, to alternatives to the use of force and firearms, including the peaceful settlement of conflicts, the understanding of crowd behavior, and the methods of persuasion, negotiation and mediation . . . with a view to limiting the use of force and firearms.” Law enforcement agencies should “review their training programs and operational procedures in light of particular incidents.”[44]

Excessive Use of Force: Shooting of Suspects

What is the situation of robbery victims, murder victims during shootings? Most of them are our Malays. Most of them are our race. I think that the best way is we no longer compromise with [criminals]. There is no need to give them any warning. If we get the evidence, we shoot first.

—Minister of Home Affairs Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, “With Criminals, We Shoot First, Admits Home Minister,” Malaysiakini, October 7, 2013

Malaysia lacks comprehensive and independent nationwide data on fatal and near-fatal police shootings. According to official police statistics, between 2000[45] and August 2012, the Malaysian police shot and killed 394 persons. Of those, 96 were killed between 2000 and 2006. From 2007[46] to August 2012, 298 people were killed. Fifty percent of those killed were of Indonesian origin and 44 percent were Malaysians.[47] SUHAKAM annual reports consistently note that they regularly receive complaints about excessive use of force and shootings. Malaysian human rights groups and media reports also regularly publicize police shootings.

Police shootings may sometimes be lawful. However, reported incidents of police shootings show a pattern in which police justify shootings by asserting the suspect had a parang or failed to stop at a roadblock or after a car chase. In some cases, the police also attempt to justify their use of lethal force by alleging that the suspect was a criminal associated with ongoing police investigations. Wholly absent from police narratives is any attempt to demonstrate that lethal use of force was the only available option to save lives at imminent risk. The apparent quick resort to lethal force raises serious concerns about the police’s standard operating procedures and training in the use of lethal force.

The cases investigated by Human Rights Watch also demonstrate lack of transparency and impartiality in police investigations into the shootings. Frequently, there are conflicting versions of the events among victims, witnesses, and the police and no mechanism to independently determine what occurred.

SUHAKAM does receive complaints of police shootings, but this can be weeks or months after the incident. Moreover, the Malaysian police do not provide SUHAKAM with copies of police investigation files. SUHAKAM is thus hampered in its ability to comprehensively assess specific incidents in which rights abuses are alleged. The absence of transparent and impartial investigations into questionable police actions undermines public confidence in the RMP’s ability to police itself and fosters public perception that the police are unaccountable.

The cases below illustrate the often vast differences between police and witness accounts. We are not able to fully assess the competing claims and take no position on the merits of any given claim, but present the cases here because they cry out for rigorous, independent investigation.

Killing of Mohd Afham bin Arin in Johor Baru

The police made me wait for hours [at the station]. I saw his motorcycle outside the station. It was covered with blood. I asked [the police] “Is Afham alive or dead?” They said he was okay. They lied.

— Saphiah binti Mohd Elah, mother of Mohd Afham bin Afrin, 20, Johor, May 2012

Mohd Afham bin Arin, 20, was shot and killed by the police on the night of October 19, 2009, in Johor Baru. Mohd Firdaus bin Marsani was seated as a passenger behind Afham who was driving his motorcycle. Firdaus told Human Rights Watch that he and Afham had finished dinner together and were heading towards Afham’s home to collect some clothes.[48] He said that they saw three men on motorbikes who tried to stop them: “We did not know they were police. They were in plainclothes. You don’t stop at night for someone saying they are police. We thought they were going to rob us.” Firdaus claimed that the men on motorbikes then chased them, “We managed to escape the three bikes, but then another bike appeared at a junction and chased us. I then heard a shot so I lifted my hands to surrender, and then I heard two consecutive shots and then we fell off the bike.”[49]

Firdaus said that he saw Afham “lying over the motorbike handles motionless.” He pulled his leg out from underneath the motorcycle and “saw a man two meters away pointing a gun at me. I raised my hands and stepped behind the road divider. A car sped towards me and stopped, and that’s when I escaped into the woods.” Firdaus said police did not pursue him, and that he was in the woods for three hours before finally managing to find his way home. He learned about Afham’s death later that morning.[50]

The police corporal, Mohd Izaddin bin Rahim, who fired the shot killing Afham has a different version of the events. According to his report, Rahim and three other corporals were “on crime prevention duty and observation” following reports of a “snatch theft” when they received a report that a Yamaha motorcycle was moving suspiciously.[51] Rahim wrote that he and his colleagues approached the motorcycle and identified themselves as policemen, but the “two Malay men sped off.” Rahim reported:

[We] chased the motorcycle that was driving recklessly and dangerously to escape [us]. … A passenger took out a parang and waved it towards me. I managed to dodge it and almost fell. Because the passenger waved his parang, my life was in danger. I was forced to shoot towards the two men. …I saw the motorcyclist with his right hand still holding onto the handle bar and there was a sword 20 cm long. I approached the motorcyclist and found that he did not move and believed he was dead.[52]

Afham’s death certificate, dated October 22, 2009, states the cause of death as “gunshot wound to the aorta.”[53]

When Firdaus heard that the police accused him and Afham of the snatch theft and of possessing a parang and a sword, he went to the police station and filed a complaint explaining his version of the events.[54] The police have not yet questioned Firdaus for the alleged snatch theft or alleged possession of a parang or sword.[55] Firdaus also told Human Rights Watch that neither he nor Afham had been armed.[56]

On October 22, Afham’s mother went to the police station and was informed by the officer in charge that her son was a wanted person for snatch theft and robbery. She recalled what the officer said: “‘The story is like this Aunty,’ he called me in a mocking tone. ‘Your son and his friend robbed the Johor Jaya Bank with parang and sword.’ But the whole time he lied. Where was the proof?”[57]

A few days after Afham’s death, in October 2009, his mother filed a complaint at the local police station demanding an investigation into the killing of her son. A month later, a woman police officer visited her home and took her statement. “I never heard from her again,” Afham’s mother said. “She did not explain what she would do with the information. No answers, no apology.”[58] In October 2012, Afham’s family filed a civil suit in the Johor Baru High Court, seeking damages. Those judicial proceedings were continuing as this report went to press.

Killing of Dinesh Darmasena, in Ampang, Kuala Lumpur

Dinesh Darmasena, a 26-year-old businessman, was shot by a plainclothes policeman on August 21, 2012, in the Kuala Lumpur suburb of Ampang. He died of gunshot wounds in Ampang hospital on August 23. A post-mortem conducted at the Kuala Lumpur General Hospital revealed that Darmasena was shot in his right arm and in the back of his head.[59]

The police alleged that Darmasena’s car backed into a patrol car. Then, according to the Ampang Jaya deputy police chief, Mohd Nazri Zawawi, “four men carrying parangs got out of the car and smashed the patrol car.”[60] Ampang district police chief Amirudin Jamaluddin said that Dinesh and others “came charging towards the policemen and my men were forced to open fire.”[61]The police also asserted that Dinesh’s car was part of a 14-car convoy on its way to resume a gang fight at the Pandan Perdana flats when police intercepted it. Harian Metro quoted Nazri as saying that Dinesh was a member of the Viva Nanda gang suspected to be involved in loan-shark syndicates.[62]

Two witnesses said they saw men in civilian clothes shooting at Dinesh, contrary to police claims that uniformed police fired the shots. Nelawarasan Yoakanatha, a friend of the deceased, reported that he saw Dinesh emerge from his car, which had been blocked by an unmarked car near a traffic light. In the complaint he filed with police on August 27, 2012, Nelawarasan stated:

We didn’t know that he was a police officer as the car was not marked “police” and he was not in uniform. Dinesh got out of his car and headed towards the police. When the police started shooting he ran back to his car. He [the man in civilian dress] then started shooting at our car. My friend Moses and I heard about 10 to 15 shots fired during the incident. At all times, Dinesh didn’t hold any weapons.[63]

Nelawarasan publicly repeated this account at a press conference convened by Dinesh’s family and lawyers, saying that “when Dinesh got out of his car to enquire, the police opened fire indiscriminately, I saw Dinesh trying to run back into his car before he got shot. Everyone panicked and I just sped off from the scene. I can assure you that we were not carrying any weapons.”[64]

A second witness, K. Moses, stopped at the traffic light two cars behind Dinesh’s car. He said that Dinesh, a friend, was “running” to his car when he was shot. “I saw beside my car that a guy was shooting,” Moses said. “I didn’t know who he was. He shot everyone. I sped off, but one bullet hit my car.”[65] The two witnesses said they were going to meet Dinesh at a restaurant and were separately driving to the destination when they saw Dinesh’s car and began following it and saw the shooting.

In September 2012, Dinesh’s family filed a complaint with police headquarters in Bukit Aman demanding that the police officer involved in the shooting be suspended and the investigation be classified as murder under the penal code.[66] An inquiry into the incident is ongoing.

Killing of Mohd Shamil Hafiz Shapiei, Mohd Hairul Nizam Tuah, and Mohd Hanafi Omar in Selangor

Mohd Shamil Hafiz Shapiei, 15, Mohd Hairul Nizam Tuah, 20, and Mohd Hanafi Omar, 22, were shot and killed at approximately 4 a.m. in Glenmarie, Shah Alam, Selangor, on November 13, 2010. The police alleged that the three had robbed a petrol station and were fleeing the station when they encountered the police. The police told the media that a car chased ensued and when the men’s car skidded and stalled two kilometers away from petrol station, the three alighted from the car and charged at the police with parangs, forcing the police to shoot them.[67] All three sustained gunshot wounds to the forehead and chest. On January 8, 2011, the families of the three, along with their lawyers, gathered in front of the Bukit Aman police headquarters to submit a complaint to the IGP, demanding an investigation into the killings. Bukit Aman public relations department chief inspector Saipul Anuar Razali received their petition and promised answers would be forthcoming.[68]

In August 2011, eight months after the incident, the three men’s families received post-mortem reports from the government hospital. The post-mortem report on Hafiz concluded that the bullet entered his head at a 45-degree angle and that gunpowder residue was found on his clothes.[69] The other two had bullet wounds on the side of their heads and in their chests. The report on Nizam concluded that he was shot twice. One bullet entered the left side of the head and exited at the right side of the ear, and the other bullet entered the front part of the left side of chest and exited at the right side of the chest.[70]

The lawyer representing the families, N. Surendran, cited the post-mortem report on Hafiz—the angle of the shot and the gunpowder residue in particular—to challenge the police’s version of the incident: “This [report] suggests that the victims were kneeling when they were shot. This contradicts the police version that the three attacked the police with a parang before they were shot dead.”[71]

Omar bin Abu Bakar expressed surprise at the manner in which his son Hanafi was shot. He told Human Rights Watch:

I am retired from the army. In my experience if the boys were charging with parangs towards police then how can the bullet be at a close range angle and not straight if the police shot at them when they [the deceased] were running at them. The police statements about the shooting are highly questionable.[72]

He later told the media that, “I am not satisfied. My son was shot in the right ear and if the police said he was attacking them, why wasn’t he shot from the front? I want the police to speed up their investigations and take action against the people who killed my son.”[73]

Selangor’s acting police chief, A. Thaiveegan, alleged that the three were involved in at least three armed robberies over five days that month in Selangor.[74] But the families questioned the allegations and noted that none of the deceased had a prior criminal record. The families also told Human Rights Watch that they were unaware that their sons were wanted criminals. After the incident, the police did not show the families any evidence to prove their sons were involved in any alleged robberies. The families said that the police did not conduct any follow-up investigation of the alleged robberies, did not visit the families’ homes to search for stolen money, and did not question them or their neighbors about their sons’ activities. Norhafizah, mother of Hafiz said, “If my son was suspected of a crime why haven’t their searched my house or asked questions about him. They justified his killing by called him a criminal after they shot him.”[75]

Hamidah Kadar, Nizam’s mother, expressed disbelief at the conduct of the police:

Police should investigate first, not shoot. If they investigated and found my son guilty then I can accept it but they just shot him. This I cannot accept. My son never had any problem with the police. The doctor who did the autopsy told me that he is clean: there were no drugs in the urine or the blood.[76]

On October 6, 2011, after examining the post-mortem reports, the three families submitted a formal complaint to the Inspector General of Police demanding an investigation into the killings.[77]

On October 20, 2011, in response to a question from a member of parliament, the Minster of Home Affairs, Hishammuddin Hussein, announced that the police “acted according to the law” and “investigated the case as attempted murder under the penal code and referred it to the attorney general’s chambers.”[78] Norhafizah told Human Rights Watch, “I want this case to go to court. No one has been charged as yet. There is no closure. The public prosecutor has not filed a complaint against the officers yet. I want justice.”[79]

Killing of Kathir Oli in Ipoh, Perak

On the night of September 15, 2011, a plainclothes police officer, Cheah Yew Teik, shot Kathir Oli, 31, outside the Angel Fun Pub and Karaoke bar in Ipoh, Perak. According to witness statements, the pub management had barred Oli and his friends, Shashitheran Kandasamy and Sangar Rahman, from entering the pub because they were ethnic Indian. An argument ensued between pub owners and Oli and his friends, who then decided to leave. Oli’s friends said that as they were driving away, a “Chinese man” pointed a gun at them and told them to stop.[80] In his police statement, Kandasamy said:

The three of us [Sangar Rahman, Kathir Oli, and Kandasamy himself] then got out of the car. I saw him [the Chinese man] holding the gun in his pocket. He pushed Kathir and Kathir responded by pushing him back. Then, he punched Kathir’s face and in response Kathir punched his face. I was terrified because I realized that [the man] had a gun, so I tried to separate [them]. I pleaded to both parties to stop fighting. But suddenly I heard a loud gun shot and saw the gun in the hands of [the Chinese man]… Kathir Oli was shot in his chest.[81]

Kandasamy stated in his police complaint that a police patrol car came “suddenly” and he and his friend were arrested and taken to a police station and [that] they did not know that the armed man was a policeman. “I was puzzled because all this while…I thought he was a pub customer, or a bouncer. I only knew he was a police officer when he handcuffed us.”[82]

The police have a different account of the events. Perak police chief Mohd Shukri Dahlan told the media that the three men were robbers who tried to rob the pub carrying parangs and that a detective who was walking by the pub stopped to help and Oli attacked him with a parang. The chief said the detective shot Oli in self-defense.[83]

According to the complaint, police at Pekan Baru police station placed Oli’s two friends in custody for 11 days on suspicion of “attempted murder,” blindfolded and beat them, and repeatedly asked whether they carried any machetes or guns.[84]The two men refused police pressure that they confess to a crime and ultimately were released without charge. To date, the police have yet to produce the parangs that they claimed Oli and his friends used to rob the pub.[85]

In September 2012, Deputy Public Prosecutor Masri Mohd Daud informed Kathir Oli’s family and the Parti Sosialis Malaysia, which became involved at the behest of the family, that no inquest would be held because prosecutors had determined that the two friends of Kathir Oli would be charged with causing mischief and causing hurt to a public servant to prevent him from conducting his duties.[86] Daud stated that under a provision of the Malaysian Criminal Procedure Code that makes inquiries unnecessary where criminal proceedings have been brought, there was no need for him to call an inquest.[87] However, to date, neither of Oli’s friends has been formally charged with either of these two crimes.[88]

Kathri Oli’s wife, Janaki Kathir Oli, has sought justice for the killing of her husband. She told Human Rights Watch, “My husband was not a robber. He never carried a knife. Why did the police kill him? We are defenseless against police’s injustice and their abuse of power.”[89] She filed a petition with SUHAKAM in 2011 demanding investigation into the incident, prompting SUHAKAM in turn to send letters about the case to the Royal Malaysia Police and the Attorney-General’s Chambers.

Killing of Aminulrasyid bin Amzah in Selangor

Aminulrasyid bin Amzah, 15, was shot dead in a hail of bullets fired by the police following a car chase after midnight on April 26, 2010, in an affluent neighborhood of Shah Alam, Selangor.[90] According to Mohammad Azzamuddin bin Omar, who was in the car with Aminulrasyid, the two were returning from a restaurant when Aminulrasyid accidentally scraped a motorcycle and then passed a police car, which began chasing them.[91] Azzamuddin stated in his report to the police:

Aminulrasyid was scared, he overtook a police vehicle and that caused the police to chase us. …I heard repeated gunshots hitting our car causing the car to swerve but it was still under control. The last shot hit Amin and he fell on my thigh. I saw a hole in his head and blood. The car went off control and crashed into a wall and stopped. I came out of the car and surrendered myself. One police kicked me from the back and others hit and slapped me. I tried to escape and ran towards my house. I was injured on the right hand, leg, and in the head.[92]

This account differs significantly from the police version, which stated police used lethal force because the driver reversed his car into the police vehicles. The day after the incident, then Selangor Police Chief Khalid bin Abu Bakar (now the inspector general of police) was quoted in the media saying that the police chased Aminulrasyid after they came across him “in suspicious circumstances.”[93] The police maintained that the police shot at the car to stop it. After the car stopped, one of the suspects escaped on foot and the driver of the vehicle suddenly reversed the car and tried to ram into the police vehicles. Khalid said that, “Surprised by the action of the suspect and trying to defend himself, the police officer shot in the direction of the suspect in the car.”[94] The police also claimed that a parang, which was allegedly used in robberies, was found in the car.[95]

Eleven police involved in the case were initially suspended but later cleared of any wrongdoing. Only one policeman, Cpl. Jenain Subi, was charged under penal code 304(a) for culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

The original police explanation by Khalid that additional bullets were fired out of self-defense when the driver reversed his car into the police cars was contradicted by forensic witnesses who testified at the trial of Corporal Subi that there was no such evidence of the car reversing itself.[96] Police rebuffed efforts by Aminulrasyid’s family, including their filing of a police report, to demand a retraction and an apology from Khalid and other senior police for claims that Aminulrasyid was a criminal and had attempted to harm police officers.[97]

Subi was found to have fired 21 bullets from a submachine gun at the car. He testified in court that the situation was not dangerous when he fired at the car. He also said that the relevant standing order on use of firearms did not permit opening fire on traffic offenders but only during the commission of crimes such as robbery, house break-ins, rape, sodomy, and kidnapping, or in self-defense.[98]

Subi was convicted on September 15, 2011, by the Shah Alam Sessions Court of culpable homicide not amounting to murder, which carries a maximum sentence of 30 years.[99] Subi received five years in prison.[100] The sessions court judge, Latifah Mohd Tahar, found that “The accused agreed that 21 gunshots were fired. This shows that there was indeed intention to cause death.” The judge added that Subi “agreed that the car did not pose any danger to the police patrol team or the surroundings of the housing area as there were no passersby or other vehicles.”[101]

Subi appealed his conviction to the Shah Alam High Court. On December 5, 2012, Judge Abdul Rahman Sebli acquitted him, ruling that “The totality of evidence does not support any suggestion that the appellant’s intention was to kill. …In any case, it is not the number of shots that matters. It is the intention behind the shots that the court should be concerned with.”[102] On November 26, 2013, the three-person Court of Appeals in Putrajaya unanimously upheld the acquittal.[103]

In contrast to other police shooting incidents, this shooting of a 15-year-old student prompted attention from senior government officials. The IGP and the home minister promised an investigation into the case and a review of the IGP standing order on use force and firearms.[104] On April 27, then-Home Minister Hishammuddin Hussein convened a special panel headed by the deputy home minster to assess the incident. The panel recommended improving existing procedures on use of firearms, which the IGP stated would be implemented. Deputy Home Minister Wera Abu Seman Yousof announced, “We have adapted the standards from the three countries [referring to Canada, United States and the United Kingdom] and the United Nations in order for us to come up with orders that are more suited for us.”[105] However, the RMP declined to make either the recommendations or the revised procedures public.

SUHAKAM requested information from the panel about their recommendations and findings, but was told by the deputy home minister that the “panel was satisfied with the police investigation which was transparent, expeditious, and covered all aspects” and noted that a “few improvements” to the IGP standing order on use of force were made. However, SUHAKAM was not given a copy of the amended procedures. [106]

A member of the panel that examined the Aminulrasyid killing, who wished to remain anonymous, told Human Rights Watch:

In the Aminulrasyid [incident] it was a traffic violation. You don’t shoot at a car to stop it unless they are shooting at you. . . The SOP was amended to instruct how to stop a car. It’s part of the training defect. . . . What do you expect from someone who has 11th grade education. Six months training [to become a policeman] is not enough. That’s why leadership and supervision is very important. [107]

Aminulrasyid’s mother, Norsiah Mohamad, told Malaysiakini that:

I want my son’s name cleared... If this had happened to them, how would they react? Every time I pass the tree where the car crashed and my son was killed, it is as though my heart is being ripped out off my chest. On that day, before even we claimed my son's body, Khalid released a public statement that my son and his friend, Azamudin Omar, had tried to ram into the police vehicle and that they found a parang in our family car. The statement was made with bad intention and falsely portrays Aminulrasyid as a criminal in order to conceal a crime committed by the police.[108]

Following the acquittal of Subi, in April 2013 Aminulrasyid’s family filed a civil suit at the Shah Alam High Court against Subi, the Shah Alam district police chief, former Selangor police chief Khalid, and the government, alleging negligence, and assault and battery. The lawsuit seeks damages from Abu Bakar for his statements about Aminulrasyid and a court finding that the defendants violated Aminulrasyid’s rights. The case was pending as this report went to press.[109]

Shooting of Shahril Azlan in Selangor

Shahril Azlan, a truck driver, was shot by police at a roadblock in Shah Alam, Selangor, on the night of April 16, 2009. Although Shahril survived, a bullet is permanently lodged in his back. Shahril was driving home with his friend Saiful around 11:30 p.m. when he saw a traffic jam and a roadblock approximately 100 meters away. His vehicle’s road tax sticker had expired so he decided to reverse direction in order to avoid the checkpoint. Shahril told Human Rights Watch:

I was adjusting my seatbelt and looking down when my friend told me that two men were approaching the car and had sticks in their hands. When I saw the men with sticks—they did not have any uniform on—I thought they were robbers so I began reversing. I panicked. Suddenly, there were bullet sounds. We bent down. The car was shot at least two to three times. I felt numb and could not feel anything and my friend told me that I had been shot. When I looked down…I saw blood.[110]

Shahril said that the two men broke the car window with a pistol and “grabbed my friend from the neck and pulled him out through the window and not the door. The other guy came towards me, pointed the pistol, and told me to step outside the truck.”[111]

Shahril asked the men who they were. They replied that they were police but did not show him any identification. “The police accused me of having drugs in the car and checked the bonnet and trunk,” Shahril said. “I asked police to call ambulance because I felt numb and was finding it difficult to breathe…It took an hour before the ambulance came.”[112] No drugs were found in the truck. Shahril’s friend was detained at the Shah Alam police station for four days and his urine was tested for drugs, which was negative. No charges were filed against him and Saiful was released.[113]

Shahril was taken to Tengku Ampuan Rahimah hospital in Klang, but they were unable to operate on him. He was then transferred to Kuala Lumpur General Hospital. According to a medical report, the bullet penetrated his arm and went through Shahril’s ribcage and is lodged in his spine.[114] The doctor advised Shahril that it cannot be removed as the procedure could paralyze him. An assistant superintendent of police visited Shahril in the hospital and took down his statement and showed him a photocopy of a parang and asked if it belonged to him. Shahril told them that it did not.[115]

Shahril said that he has not heard from the police again and does not believe the police seriously investigated the incident. He told Human Rights Watch: “The police told me that they would investigate the matter. My father lodged a complaint asking for an investigation hours after the incident and again in May 2012. But it has been three years now and nothing. I could not bend for eight months and was restricted to only light work for more than a year. I used to earn RM 2000 (US $625) [per month]. But because I could only do light work, I earned only 500 ringgit (US $156), which is not enough.”[116]