Summary

On the evening of August 29, 2012, five men gathered in a grove of date palms behind the local mosque in Khashamir, a village in southeast Yemen. Moments later, US remotely piloted aircraft, commonly known as drones, launched three Hellfire missiles at the group.

The strike killed four of the men instantly, hurling their body parts across the grounds. The blast of a fourth missile hit the fifth man as he crawled away, pinning him lifeless to a wall.

Yemen’s Defense Ministry described three of the men as members of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the Yemen-based armed group that has been fighting the Yemeni government, and which the United States calls the most active affiliate of Al-Qaeda. The men were killed, it said, while “meeting their fellows.”

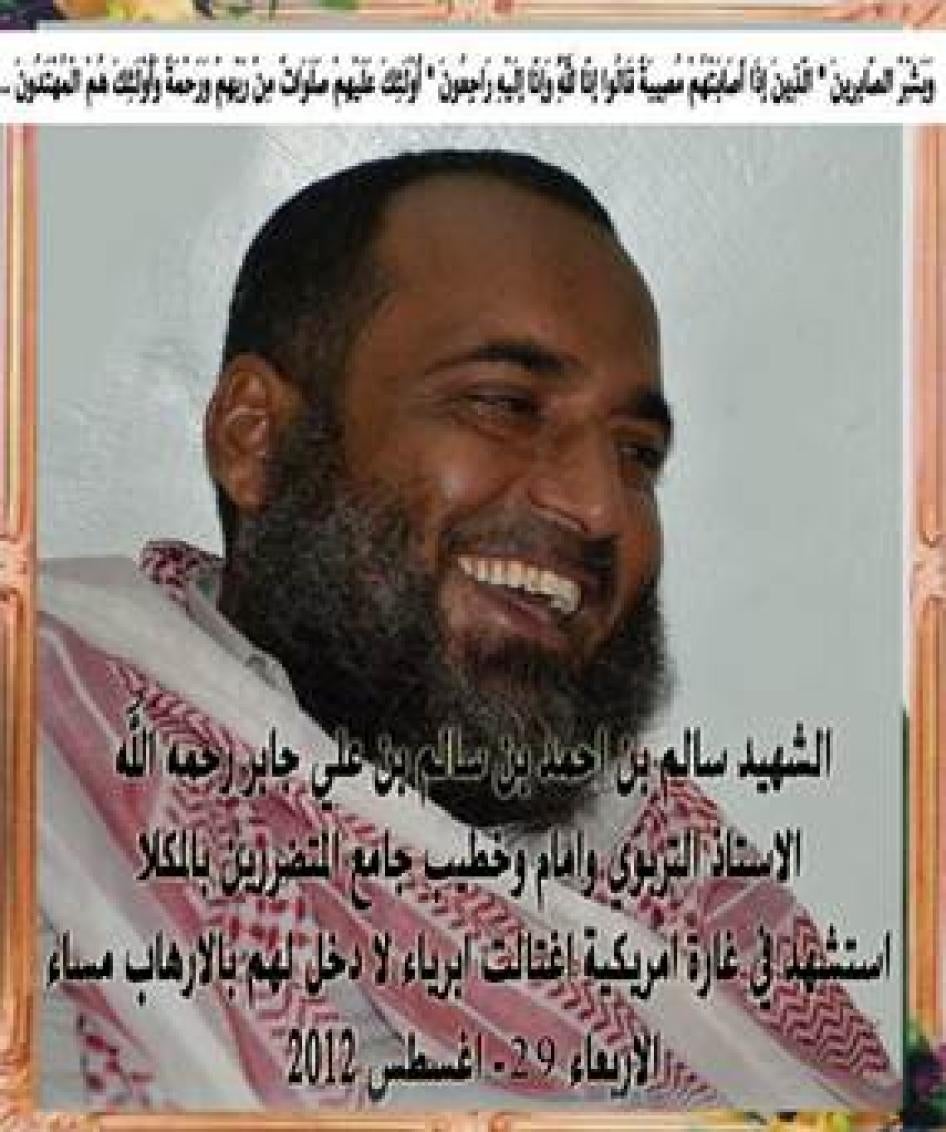

But the two “fellows” they were meeting had no known links to AQAP. Rather, they were respected members of their community. Salim bin Ali Jaber, a cleric and father of seven, had long preached against AQAP’s violent methods. The other was the cleric’s cousin Walid bin Ali Jaber, one of the village’s few police officers. Relatives said the three alleged AQAP members demanded a meeting with the cleric because the previous Friday he had made a particularly strong denunciation of AQAP at the local mosque. Walid Jaber had joined the meeting as a security measure.

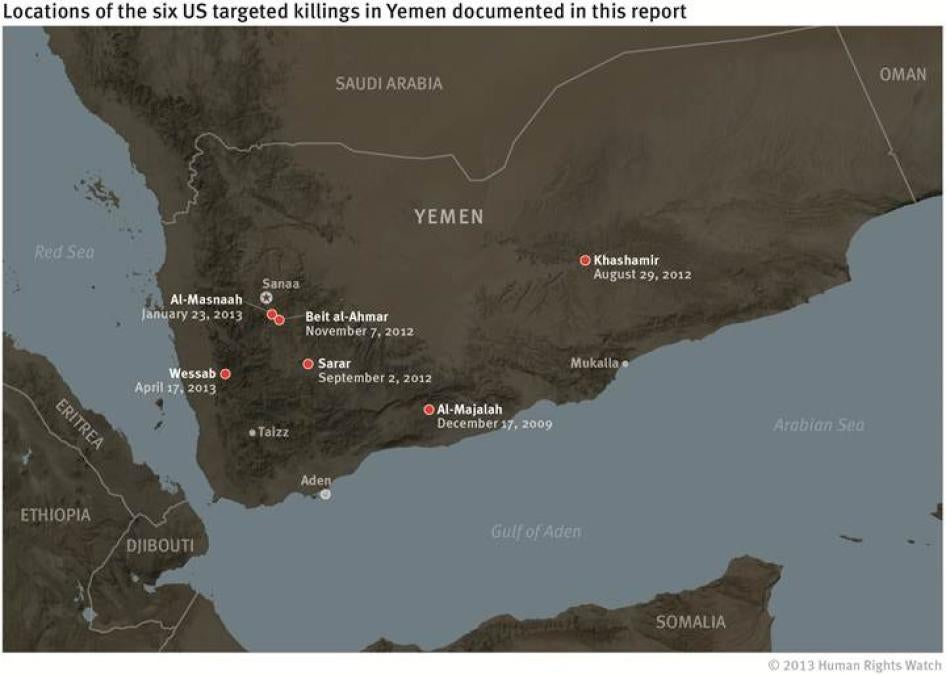

The strike in Khashamir is one of six unacknowledged US military attacks against alleged AQAP members in Yemen that this report examines. Each of the airstrikes bears the hallmarks of a so-called targeted killing, the deliberate killing by a government of a known individual under color of law.

Two of these attacks were in clear violation of international humanitarian law—the laws of war—because they struck only civilians or used indiscriminate weapons. The other four cases may have violated the laws of war because the individual attacked was not a lawful military target or the attack caused disproportionate civilian harm, determinations that require further investigation. In several of these cases the US also did not take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians, as the laws of war require.

Some of those targeted by US forces as terrorist suspects may not in fact have been valid military targets. Where the laws of war apply, combatants may lawfully be attacked. Persons who accompany or support an organized armed group, but whose activities are not directly related to military operations, such as engaging in recruiting or propaganda, are not lawful military targets.

Where the United States acts as a party to the armed conflict between the Yemeni government and AQAP, US military actions fall within the laws of war. Should the fighting between the US and AQAP not meet the threshold for an armed conflict, any attacks carried out independently of the Yemen-AQAP conflict, including some or all of the attacks detailed here, would fall under international human rights law. Human rights law only permits the use of lethal force where there is an imminent threat to human life.

Beyond international legal considerations, the evidence strongly suggests that the strikes did not adhere to policies for targeted killings that US President Barack Obama disclosed in a speech in May 2013.

These policies, which more closely reflect a law-enforcement model than a war model, provide that the United States will conduct strikes only against individuals who pose an “imminent threat to the American people”; when there is a “near-certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured” and when the target is present. President Obama also said the United States “does not take strikes when we have the ability to capture individual terrorists; our preference is always to detain, interrogate, and prosecute.” While the attacks detailed in this report predate Obama’s speech, the White House said on the day he disclosed the policies that they were “either already in place or will be transitioned into place over time.”

The Yemeni government has conceded that two of the six attacks described in this report resulted in deaths and injuries to civilians. It has made payments to families of some of the civilians killed but has failed to adequately compensate many others. The US government has not publicly acknowledged involvement in any of the six attacks, and while US officials say they work with local authorities to provide “condolence payments” to civilian victims, we are not aware of any evidence that it has done so in Yemen. Regardless of the lawfulness of specific attacks, the deaths of numerous civilians and the lack of compensation to most families has fueled public anger and frustration in Yemen against the United States, doubtless to the benefit of AQAP.

“We Yemenis are the ones who pay the price of the ‘war on terror,’” said Faisal bin Ali Jaber, a relative of the cleric and policeman killed in Khashamir. “We are caught between a drone on one side and Al-Qaeda on the other.”

Targeted Killings

The US Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), which is a semi-covert arm of the military, and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) are estimated by research groups to have carried out 81 targeted killing operations in Yemen: one in 2002 and the rest since 2009. The strikes by drones, warplanes or cruise missiles by various counts have killed at least 473 combatants and civilians. The United States has also carried out hundreds of targeted killing operations, primarily by drones, in Pakistan and a small number of such strikes in Somalia.

After many years of neither confirming nor denying such strikes, President Obama and other top US officials began publicly acknowledging the targeted killings program in 2010. However, citing national security concerns, the administration has provided only the barest information about individual strikes. For example, US authorities have not revealed the number of strikes, the number of civilians and alleged combatants killed or wounded, or, with a few exceptions, the target of the strikes. Moreover, the administration’s legal rationale for such killings, outlined in various speeches and “fact sheets” by the government in the past two years, has been inadequate.

Yemeni President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi has publicly praised the US drone campaign in Yemen, but his government has been almost as silent as the United States on details.

Case Studies

Human Rights Watch investigated the six strikes during two trips to Yemen in 2012 and 2013. These attacks, one from 2009 and the rest from 2012-13, killed 82 people, at least 57 of them civilians. At least four of the strikes were carried out by drones, a fifth strike by either drones or warplanes, and a sixth one by cruise missiles releasing cluster munitions, indiscriminate weapons that pose unacceptable dangers to civilians.

This report assesses whether these attacks comply with the laws of war. It also considers them with respect to the guidelines that President Obama disclosed in May 2013 for targeted killings. Those guidelines seem reflective of international human rights law, which prohibits the use of lethal force in law enforcement situations except when absolutely necessary to protect human life.

In addition to the attack in Khashamir, this report details the following strikes:

- Wessab, April 17, 2013: Two drones launched at least three Hellfire missiles at a car in Wessab, a township in Dhamar province in central Yemen. The missiles killed a suspected local AQAP leader, Hamid al-Radmi, as well as his driver and two bodyguards. The strike appears not to have complied with the Obama administration guidelines because it appears that al-Radmi could have been captured rather than killed. Al-Radmi was one of the most visible figures in Wessab, traveling openly to mediate disputes among residents, and meeting regularly with security and political officials. While linked to AQAP, it is not evident that he played a role in military operations that would have made him a valid military target.

- Al-Masnaah, January 23, 2013: One or more Hellfire missiles launched from a drone killed all four people in a truck in the village of al-Masnaah as they traveled to nearby Sanhan, a town about 20 kilometers southeast of Sanaa, the capital. Two passengers were suspected AQAP members. The two others, the driver and his cousin, were civilians hired by the AQAP suspects to drive them to Sanhan. Depending on the military importance of the two targeted AQAP members, under the laws of war the strike may have caused disproportionate harm to civilians. Yemen’s Minister of Interior exonerated the two cousins of any ties to the targets in a letter to the families, but relatives said neither the Yemeni nor the US government provided the families any compensation.

- Beit al-Ahmar, November 7, 2012: A drone strike killed Lt. Col. Adnan al-Qadhi, an officer in an elite Yemeni army unit who was a suspected local AQAP leader, in Beit al-Ahmar, a military town 15 kilometers from Sanaa. The strike also killed one of his bodyguards. Inconsistent with the Obama administration guidelines, the evidence suggests that Al-Qadhi could have been captured rather than killed. Nor is it clear that he played a military operational role for AQAP. In April 2013, AQAP issued a video in which an 8-year-old boy, held with his father, a soldier, “confessed” that military officers instructed him to plant a tracking device on al-Qadhi.

- Sarar, September 2, 2012: As two drones flew overhead, two warplanes or drones attacked a vehicle heading north from the city of Radaa in central Yemen. The strike in the hamet of Sarar killed 12 passengers, including 3 children and a pregnant woman, in violation of the laws-of-war prohibition against attacks that do not discriminate between civilians and combatants. The driver and a 13th passenger survived. The strike’s apparent target, tribal leader Abd al-Raouf al-Dahab, was not in the vehicle, and it is not clear that he was even a member of AQAP. The Yemeni government admitted the attack was a mistake but for months provided the victims’ families only limited compensation: 100 Kalashnikov assault rifles and cash for burial costs. Only in June 2013, after Human Rights Watch and other groups raised the case with the United States, did the Yemeni authorities compensate the families for the deaths.

- Al-Majalah, December 17, 2009: As many as five US Navy Tomahawk cruise missiles armed with cluster munitions struck the hamlet of al-Majalah in southern Abyan province. Yemeni government officials described the attack as a Yemeni airstrike that killed 34 “terrorists” at a training camp. According to a Yemeni government inquiry, the strike actually killed 14 suspected AQAP fighters, including the apparent primary target, Muhammad al-Kazami, but also at least 41 local civilians living in a Bedouin camp, including 9 women and 21 children. Subsequently, cluster munition remnants killed at least 4 additional civilians and wounded 13 others. This attack may more properly be viewed as a violation of international human rights law. However, even within a laws-of-war analysis, the attack used indiscriminate cluster munitions, and caused indiscriminate and possibly disproportionate civilian casualties. The families have not received any compensation for the deaths or injuries.

US and Yemeni officials did not respond to written questions from Human Rights Watch on the six cases and on targeted killings policies. A Yemeni government official with knowledge of the strikes, who spoke to Human Rights Watch on condition of anonymity, acknowledged that in some cases, the targets’ status with AQAP fall into a gray area:

It is not clear in some cases whether they are actually military commanders or operators of attacks. But they recruit openly, openly. . . Striking is not the most ethical position [in some of these cases]. But if you don’t strike them, will they recruit more? That is the debate.

The official said that the Yemeni government has virtually no control over much of Yemen, and therefore is “too weak” to capture many suspects: “Our security apparatus is in shambles. . . . So what do you do? The easiest option is, you take them out.”

International Law and US Policy

The legality of a “targeted killing” under international law may depend on whether the attack was conducted during an armed conflict or during law enforcement operations. International humanitarian law, the laws of war, apply during armed conflicts between states or between a state and a non-state armed group. International human rights law applies at all times, except where superseded by specific laws of war.

The laws of war permit attacks only on enemy combatants and other military objectives. Combatants include members of armed groups taking a direct part in hostilities, but not those who play a purely non-military role. Civilians and civilian objects are protected from attack. Not all attacks that cause civilian deaths or injuries violate the laws of war—only those that target civilians, do not discriminate between civilians and combatants, or cause civilian loss that is excessive compared to the anticipated military gain. Parties to a conflict must take all feasible steps to minimize civilian harm, including by not deploying in densely populated areas. States have an obligation to investigate serious violations of the laws of war and prosecute those found responsible.

During situations of law enforcement, in which international human rights law applies, lethal force may only be used as a last resort where there is an imminent risk to human life. The standards set out by the Obama administration for targeted attacks appear to reflect this law enforcement approach, requiring that the target pose an imminent risk to the United States, cannot reasonably be captured, and can be attacked without putting civilians at risk. However, the administration has not said that it was adopting an approach consistent with human rights law.

The use of drones does not directly affect the legal analysis of a particular attack. These remotely piloted vehicles and the missiles and laser-guided bombs they carry are not illegal. When used appropriately, drones’ enhanced surveillance capabilities can help minimize civilian casualties in combat operations. But as with other aerial attacks, drone operations may be hampered by poor intelligence or a failure to minimize the risk of civilian harm.

Even if some of the attacks described in this report do not violate the laws of war, they appear to fall short of the thresholds set by the Obama administration for carrying out targeted killings. Attacks that do not meet the US policy guidelines would contravene law enforcement standards under international human rights law.

The applicability of a war model to US operations against Al-Qaeda has increasingly been called into question. Hostilities between a state and a non-state armed group are considered to be an armed conflict when violence reaches a significant threshold and the armed group has the capacity and organization to abide by the laws of war. Hostilities between AQAP and the Yemeni government have risen to the level of an armed conflict in recent years. That is less clear with respect to hostilities between AQAP and the US government. This distinction is legally important because the United States asserts it is

carrying out operations against Al-Qaeda and “associated forces” to protect US interests and not because it is a party to the Yemen-AQAP conflict.

Under that rationale, the US government should be applying a war model to its counterterrorism operations in Yemen only if there is a genuine armed conflict between the US and AQAP. Otherwise the United States needs to be acting in accordance with the higher threshold for the use of force under applicable law enforcement standards found in international human rights law.

Al-Qaeda and other non-state armed groups that the United States considers to be “associated” forces, such as AQAP, continue to threaten US interests, but President Obama has long disavowed the paradigm of a “global war on terror.” The sporadic nature and smaller scale of any successful operations against US targets by these groups in the 12 years since the attacks of September 11, 2001, further diminishes the relevance of this model.

Should the United States continue targeted killings in Yemen without addressing the consequences of killing civilians and taking responsibility for unlawful deaths, it risks further angering many Yemenis and handing another recruiting card to AQAP. In response to these killings, AQAP has issued statements accusing the United States of fighting a war not just against Al-Qaeda but against all Muslims. Residents have set up roadblocks and held demonstrations in which they chant anti-US slogans. Yemen’s National Dialogue Conference, tasked with drafting the country’s new political and constitutional roadmap, has called for criminal penalties under domestic law for any targeted killings that violate international law.

In Khashamir, every man, woman, and child has seen the photos of Salim and Walid Jaber, the cleric and policeman, after they were struck by drone-launched missiles. The images show the men’s bodies charred and in pieces—relatives said they identified Salim Jaber by his cheekbone, and Walid Jaber by the remains of his handgun and his ornate belt.

“Now when villagers see these images,” said a relative, Faisal Jaber, “they think of America.”

Map of Strikes

Key Recommendations

The governments of the United States and Yemen should immediately take measures to reduce civilian casualties from targeted killings in Yemen and to ensure these strikes comply with international law.

To the Obama Administration

- Explain the full legal basis on which the US carries out targeted killings, including the attacks detailed in this report. Publicly clarify all policy guidelines for targeted killings and disclose when each standard went into effect.

To the Governments of the United States and Yemen

- Ensure that all targeted killings conducted during armed conflict situations accord with the laws of war, including by taking all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians. Outside of armed conflict situations, use lethal force only when absolutely necessary to protect human life in accordance with international human rights law.

- Implement a system of prompt and meaningful compensation for civilian loss of life, injury, and property damage from unlawful attacks. To address the backlash from civilian deaths, institute a system of condolence payments for losses in which there is no assumption of liability.

- Conduct prompt, thorough, and impartial investigations into the cases in this report and other cases where targeted strikes may have resulted in unlawful killings. Make public the findings and seek disciplinary measures or criminal prosecutions as appropriate.

Methodology

This report is based on six weeks of field research carried out by Human Rights Watch in Yemen between September 2012 and June 2013. The report details six US airstrikes in Yemen that killed 82 people, at least 57 of them civilians. One strike was in 2009 and the rest were in 2012-13.

A Human Rights Watch researcher and two consultants interviewed more than 90 people for this report, most in the Yemeni cities of Sanaa, Aden, and Radaa, and the town of Wessab, as well as in person in the United States, electronically, and by phone. Interviewees included witnesses to airstrikes, relatives of those killed, lawyers, human rights defenders, journalists, political and security analysts, diplomats, and Yemeni government and security officials.

Human Rights Watch contacted Yemenis through local and international nongovernmental organizations, and lawyers for victims or suspects. We carried out interviews in English or in Arabic, often using interpreters. Most people were interviewed individually. We informed the interviewees of the purpose of our research and did not pay them or offer them other incentives to speak with us. In some cases, we have withheld the name, location, date of interview, or other identifying information to protect the interviewee from possible retaliation.

We reviewed dozens of videos and photos taken in the immediate aftermath of the strikes in question, many of which showed remnants that helped identify the types of weapons used. In some cases we also examined remnants taken from the scene. We also read scores of international and Yemeni media reports and, in the few instances available, Yemeni government documents on the killings.

Human Rights Watch was not able to visit most of the strike areas for security reasons. Yemeni consultants visited two attack sites, Sarar and Wessab.

Human Rights Watch sent written requests for comment on these strikes to the US Central Intelligence Agency, the White House, and the Department of Defense, as well as to Yemen’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The only agency to formally respond was the CIA, which declined comment. Future responses will be posted on the Counterterrorism page of the Human Rights Watch website: www.hrw.org.

I. Background

Yemen and Al-Qaeda

Yemen is a country of 25 million people on the southwest tip of the Arabian Peninsula. It was fertile ground for Islamist fighters well before the formation of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in 2009. Much of Yemen’s rugged terrain is largely outside the central government’s control.[1] One of the poorest countries in the Middle East, it has a soaring population of unemployed young people. It is running out of oil—the government’s main revenue source—and water.[2]

AQAP and its antecedents gained strength during the 33-year presidency of Ali Abdullah Saleh, whose government devoted more attention to fighting rebels known as Huthis in the north, quashing a secessionist movement in the south, and juggling tribal interests than to countering armed Islamist militants.[3]

During the security vacuum created during the 2011 uprising in Yemen, AQAP created a domestic offshoot, Ansar al-Sharia (“Partisans of Islamic Law”), that occupied several towns in the south. Saleh ceded the presidency in February 2012 to his longtime vice president, Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi, who pledged to lead the country to general elections in 2014.

Origins of Yemen’s Islamist Armed Groups

In the 1980s many Yemeni youth considered it a rite of passage to fight in Afghanistan with US-backed mujahideen against occupying Soviet forces. Yemenis continued to train in Afghanistan under Taliban rule through the 1990s, with the acquiescence of both the Yemeni government and influential tribes and clerics.[4]

Osama bin Laden, whose father was Yemeni, saw the country as an ideal operating base. Fighters who had trained with bin Laden in Afghanistan formed an armed militant group called Islamic Jihad in Yemen in 1990, which was succeeded by the Islamic Army of Aden- Abyan in 1994 and Al-Qaeda in Yemen (AQY) in 1998.[5]

President Saleh incorporated many of the returning Afghan war veterans into his security forces, using them to fight Huthi rebels in the north as well as separatists in the south.[6]

This marriage of convenience began to fray in October 2000, when AQY attacked the Navy destroyer USS Cole off the coast of Aden, Yemen’s southern port city, killing 17 US sailors. Under pressure from the United States and its allies, Saleh pledged to rein in the group. In response, a new generation of Yemeni armed militants began viewing the Yemeni authorities as an additional target. Many of these militants had honed their fighting abilities in Iraq, where they had joined the fight against the US-led invasion in 2003 with little interference from the Yemen government.[7]

That next generation coalesced after a breakout of 23 Al-Qaeda-linked suspects in 2006 from a Political Security Organization prison in the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, apparently with inside help.[8] In 2007, AQY killed eight Spaniards and two Yemenis at a tourist site in eastern Shabwa province. In 2008, the group shot dead two Belgian tourists and their drivers in Hadramawt, in the southeast. That same year suicide bombers struck the US Embassy in Sanaa, killing 17 Yemenis and one Yemeni-American. AQY also in 2008 launched its own magazine, Sada al-Malahim (The Echo of Battles). The following year, an AQY suicide bomber killed four South Korean tourists and their Yemeni driver in Hadramawt.[9]

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

In January 2009, Al-Qaeda’s Yemeni and Saudi organizations merged into Yemen-based Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). The Yemen-based group quickly set its sights on international and regional as well as domestic targets. That December the United States designated AQAP as Al-Qaeda’s most active branch.[10]

Estimates of AQAP’s size range from several hundred to a few thousand members, many of whom participate in military operations. The group’s inner circle is believed to have anywhere from 50 to 100 members, of whom 10 to 24 are considered key figures.[11] The top tier includes the group’s commander, Nasir al-Wuhayshi. In August 2013 Ayman al-Zawahiri, the head of Al-Qaeda central, reportedly named al-Wuhayshi his “Ma’sul al-Amm,” an Arabic phrase that translates to “general manager.”[12]

Many AQAP fighters have deployed exclusively for an insurgency against the Yemeni government, including those fighting with Ansar al-Sharia, the domestic offshoot that the group created in 2011.[13] AQAP has described Ansar Al-Sharia as a vehicle to spread the group’s strict interpretation of Sharia (Islamic law) in areas under its control.[14]

In Saudi Arabia in August 2009, an AQAP suicide bomber attempted to kill Muhammad bin Nayef, who headed the kingdom’s counterterrorism efforts. AQAP also claimed responsibility for the attempted bombing of a US airliner en route to Detroit on Christmas Day 2009 by a Nigerian man who unsuccessfully tried to detonate explosives in his underwear. That year, AQAP claimed responsibility for another failed plot in which it placed explosive-laden ink cartridges aboard two US-bound cargo planes.[15]

In July 2010, AQAP launched an English-language magazine, Inspire, aimed both at recruiting English-speaking members and justifying the group’s actions among the general non-Arab Muslim population. Inspire’s contributors included the American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, who was killed in a US drone strike in Yemen in 2011. Its first issue drew attention worldwide for its pressure-cooker recipe, “Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of Your Mom.”[16]

In 2012, the CIA thwarted a plot by AQAP to blow up a US passenger jet with an “upgrade” of the “underwear bomb” that had failed to properly detonate in 2009.[17] At his confirmation hearing as CIA director in February 2013, John Brennan, then President Obama’s chief counterterrorism advisor, confirmed he had told news analysts that the plot was never a serious threat because the United States had “inside control” over it.[18]

Inside Yemen, AQAP’s primary targets are Yemeni government security and foreigners. The group’s attacks have killed hundreds of government military and intelligence personnel. Generally AQAP has not targeted Yemeni civilians, but the group has killed several Yemenis it labeled “apostates,” “homosexuals,” or “spies” for the Yemeni and US governments.[19] In October 2013 AQAP killed a German bodyguard to Germany’s ambassador to Yemen.[20] At the time of writing AQAP was holding several foreigners for ransom, including a Saudi diplomat.[21]

In 2011, AQAP’s offshoot Ansar Al-Sharia seized two main towns and nearby villages in southern Abyan province during the political vacuum created by Yemen’s 2011 uprising Yemeni government forces fled their posts as Ansar fighters descended on Abyan.[22]

Ansar al-Sharia declared the areas it controlled to be a caliphate and imposed its interpretation of Islamic law on local populations. At the same time, the group won over some residents by providing water and basic services.[23] AQAP recruited hundreds if not thousands of fighters from the ranks of Yemen’s unemployed youth, many of whom defected to pro-government forces after Ansar al-Sharia’s retreat from Abyan.[24]

A combination of Yemeni troops, pro-government militias, and US and allegedly Saudi airstrikes routed Ansar al-Sharia from Abyan in June 2012 after months of fighting in which both Yemeni and Ansar forces appeared to violate the laws of war.[25] Ansar fighters dispersed into more remote parts of Abyan as well as other provinces largely outside the government’s reach.

In December 2012, AQAP offered a bounty for killing the US ambassador to Yemen or any US soldier in the country.[26] At the time of writing AQAP continued to clash regularly with Yemeni government forces and kill ranking intelligence and security officials in bombings and drive-by shootings including in Sanaa and the southern port city of Aden.[27] In August 2013, al-Wuhayshi, the commander of AQAP, was reportedly intercepted while electronically plotting attacks on US targets with al-Zawahiri, the head of Al-Qaeda central, prompting the Obama administration to temporarily shutter 22 US diplomatic missions worldwide.[28]

Targeted Killings and US Counterterrorism Activities in Yemen

The use of force must be seen as part of a larger discussion we need to have about a comprehensive counterterrorism strategy, because for all the focus on the use of force, force alone cannot make us safe. [29]

– US President Barack Obama in May 2013 speech on counterterrorism policy

The US government is the largest western donor to Yemen, since 2007 providing more than US$1 billion to the country, most of it for counterterrorism programs. Since 2009, targeted killings, the deliberate killing by a government of a known individual under color of law, have played an increasingly prominent role in US counterterrorism efforts in the country. Yemen also receives security and development support from the Friends of Yemen, a group of 39 countries and international organizations.[30]

Training Yemeni Counterterrorism Units

More than half of the $1 billion in US assistance was earmarked for training and equipping two counterterrorism units headed until 2013 by former president Saleh’s close relatives, according to a US General Accounting Office report. The report found that “decision makers lack the information necessary to adequately assess” the results of that assistance.[31]

The two Yemeni units—the military Special Operations Forces and the paramilitary Counter-Terrorism Unit—rarely engaged in counterterrorism operations outside the capital, and during the 2011 uprising were deployed to guard then-president Saleh.[32] The Special Operations Forces were commanded by Saleh’s son, Ahmed Ali Saleh, who also headed the Republican Guard. The Counter-Terrorism Unit was run by Saleh’s nephew, Yayha Saleh, as part of the Central Security Forces. Both the Republican Guard and Central Security Forces committed serious human rights violations during Yemen’s 2011 uprising.[33] All of these forces were being reorganized in 2013 as part of a broader Yemeni security-sector restructuring overseen by the United States and the European Union.

First Targeted Killing in 2002, Resumption in 2009

In 2002, Yemen became the site of the first known US targeted killing by a remotely piloted aircraft, or drone. A US Predator launched an attack that killed Abu Ali al-Harithi, the head of AQY. The strike also killed five other alleged AQY members including Abu Ahmad al-Hijazi, a US citizen.[34]

For seven years the United States conducted no further known targeted killings in Yemen, while the number of such strikes skyrocketed in Pakistan. The United States resumed targeted killings in Yemen in 2009 within days of designating AQAP a terrorist organization. Since then, research groups estimate that the United States has carried out an estimated 81 targeted strikes in Yemen with manned aircraft, drones, or sea-launched cruise missiles. The number of people killed in these strikes has not been reported by the United States or Yemen. Research groups report that at least 473 people have been killed in these strikes, the majority of them combatants but many of them civilians.[35]

The United States had viewed Saleh as a fickle counterterrorism partner.[36] But President Obama has praised his successor, President Hadi, as a staunch ally in US efforts to counter AQAP.[37] Under Hadi, the number of targeted killings quadrupled in 2012 from the previous year. Although the pace slowed in 2013, at this writing US forces reportedly carried out 22 drone strikes in Yemen during the first nine months of the year, for the first time exceeding the number of strikes in Pakistan.[38]

US airstrikes have killed at least nine alleged “high-value” targets, a Yemeni government official with knowledge of the strikes told Human Rights Watch.[39] These include four suspected AQAP leaders, most notably American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, whom the Obama administration called the head of the group’s foreign operations, and Said al-Shihri, its deputy commander, who had survived at least two previous US strikes.[40] Several other AQAP leaders are believed to remain at large including at least three of the group’s four founders: AQAP commander al-Wuhayshi; military commander Qasim al-Raymi; and bomb-maker Ibrahim al-Asiri.[41]

Secrecy of Targeted Killings

President Obama and other top US officials have officially acknowledged the targeted killings program in general terms since 2010 and the use of armed drones in the program since 2012.[42] But the United States with few exceptions refuses to officially confirm or deny its role in specific strikes, whether in Yemen or elsewhere. Nor will it disclose other basic details such as casualty figures for combatants or civilians, who or how many individuals are on its kill list, or the extent or findings of any post-strike investigations. It also will not release its videos of drone strikes.[43]

Most targeted killings in Yemen are carried out by the US Defense Department’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) in coordination with the CIA. The CIA reportedly has authority over virtually all targeted killings in Pakistan and maintains an information blackout on its strikes, despite mounting pressure to reveal basic details.[44] JSOC is almost as secretive. Media reports in the first half of 2013 predicted President Obama would announce a transfer of strike authority from the CIA to the US military but at the time of writing he had not done so.[45]

Yemeni government officials at times have falsely stated that US airstrikes in Yemen were the work of the Yemeni Air Force.[46]

Lack of access to the attack areas, most of which are too dangerous for international media and investigators to visit, makes it extremely difficult to verify casualty figures, conclusively determine how many of those killed were civilians, and learn the full circumstances of a strike.[47]

In a major speech on counterterrorism on May 23, 2013, President Obama said there is a “wide gap” between the casualty assessments of his government and nongovernmental organizations but did not elaborate.[48] Brennan in February 2013 told the US Senate Intelligence Committee that civilian casualties during targeted killings are “exceedingly rare.”[49] Human Rights Watch is skeptical of these claims in light of the numerous credible reports of civilian casualties in Yemen and Pakistan.

Brennan also said the administration should “make public the overall numbers of civilian deaths resulting from US strikes targeting Al-Qaeda.”[50] When the United States kills civilians during targeted killing operations, he said, “the United States government should acknowledge it.’’[51]

Yet the United States has publicly confirmed only two targeted killing operations in Yemen since 2009—those that killed three US citizens.[52] Only one is known to have been the intended target: the cleric al-Awlaki, whom the US alleges was an AQAP leader, although it has refused to disclose all but one source for the evidence against him. The other two US citizens included Awlaki’s teenage son, Abd al-Rahman Anwar al-Awlaki, and Samir Khan, the editor of Inspire.[53]

The United States did not publicly acknowledge a direct military role in Yemen until mid-2012, when it assisted Yemeni forces in carrying out air strikes against AQAP and Ansar al-Sharia in Abyan province. President Obama said at the time that the United States was not killing persons who did not pose a direct terrorist threat to the United States and its interests.[54] However, the United States continued to withhold all details of its strikes.

Around the same time, the Obama administration reportedly authorized the CIA and JSOC to carry out so-called “signature strikes,” which target individuals based on a pattern of behavior rather than specific information about their activities, in Yemen.[55]

“Pain Now, or Pain Later”

As discussed below, President Obama in May 2013 disclosed a higher threshold for targeted killings, saying members of Al-Qaeda and undefined “associated forces” would be targeted only if they were part of a “continuous and imminent threat” to the United States, and that they would be killed only if capture was not feasible.[56]

Two months later, following reports in July 2013 of a plot against the United States by AQAP commander al-Wuhaysi and Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Obama administration temporarily shuttered 22 diplomatic missions worldwide,[57]and launched nine drone strikes in Yemen over a two-week period, killing about three dozen alleged AQAP members.[58]

President Obama denied any backtracking on his targeted killing policy.[59] But a senior US official was quoted that month in the New York Times as saying that the United States had “expanded the scope of people we could go after” in Yemen in response to the alleged plot.

“Before, we couldn’t necessarily go after a driver for the organization; it’d have to be an operations director,” said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Now that driver becomes fair game because he’s providing direct support to the plot.”[60]

Two of those killed were on Yemen’s list of “most-wanted terrorists,” a Yemeni government official told Human Rights Watch.[61] But NBC News reported that most of those killed in the strikes in July and August of 2013 were not high-ranking AQAP members and none of the three alleged AQAP members identified in one strike had “operational significance,” raising further questions about administration’s application of its stated policy:

The military’s roster was delivered to the White House, said [one US] official, along with a message that eliminating the targets—most of whom were lower level militants—was a question of “pain now, or pain later.” The White House could choose between criticism for alleged excessive use of drones or deal with the consequences of sparing the militants.[62]

Target Approvals

President Obama reportedly reserves the final say over every targeted killing.[63] In Yemen, President Hadi has said he personally approves each strike as well.[64]

President Hadi said counterterrorism missions are monitored from a joint operations center in Yemen staffed by military and intelligence personnel from the United States, Saudi Arabia and Oman.

A career military officer, President Hadi has publicly praised drone strikes, describing the remotely piloted vehicles as “more advanced than the human brain.” He acknowledged errant strikes early in the targeted killings campaign, but said that both Yemen and the United States have taken “multiple measures to avoid mistakes of the past.”[65]

“As a military guy, Hadi is terribly impressed with the technology,” one foreign diplomat told Human Rights Watch. But, he added, even if the Yemeni president reviews every strike, “he gives the United States carte blanche” on the final decision.[66]

AQAP Surge and Backlash

Popular discontent with the US airstrikes—evidenced by demonstrations, roadblocks, and confirmed in interviews with scores of Yemeni citizens as well as security analysts, diplomats, and journalists—has generated hostility toward the United States and undermined public confidence in the Yemeni government. Security analysts believe this significantly bolsters the ranks of AQAP.[67]

Gregory Johnsen, a Yemen scholar and AQAP expert, estimates that the number of rank-and-file may have tripled since the United States resumed targeted killings in 2009, from 300 to more than 1,000.[68]

AQAP analysts say the growth may stem from several factors that include a security vacuum in Yemen during the 2011 uprising. And US officials contend that the numbers would be higher if the United States was not actively carrying out attacks. But the backlash against US killings beyond AQAP’s inner circle is most frequently cited as the primary cause of opposition to the strikes.

The New York Times reported in 2012 that the United States was focused on killing or capturing about “two dozen” AQAP operative leaders in Yemen, not an entire domestic insurgency.[69] Johnsen said that the number of primary US targets may now be down to 10 or 15. On August 5, 2013, the Yemeni authorities released a list of its “most wanted terrorists” that contained 25 names.[70]A Yemen official said that of those, three had since been detained and two had been killed in drone strikes, reducing the number to 20. According to Johnsen:

A lot of people are dying in those strikes. Yet the head of AQAP is still alive, his military commander is still alive, and its top bomb-maker is still alive. The fallout from all of these deaths is something the US doesn’t seem to quite take into account.[71]

Some if not many of those killed by the United States outside AQAP’s core membership may have been fighters in the domestic insurgency against the Yemeni government.[72] But as a policy matter, such killings risk doing the United States more harm than good by alienating large segments of the Yemeni population.[73]

Any backlash in Yemen is compounded because even when strikes hit AQAP fighters who may be lawfully targeted in an armed conflict situation, they are usually killing members of tightly knit families and tribes, not fighters from outside their communities. “The United States can target and kill someone as a terrorist, only to have Yemenis take up arms to defend him as a tribesman,” Johnsen said.[74]

Despite President Hadi’s embrace of the strikes, many Yemenis consider them a violation of national sovereignty and note that the Yemeni parliament has never authorized US armed intervention in Yemen.[75]

In July 2013 Yemen’s National Dialogue Conference, tasked with drafting the country’s new political and constitutional roadmap, called for “criminalizing” under Yemeni law any drone strikes and other killings during counterterrorism operations that violate international law.[76]That language is multiple steps from being translated into action and would in any case duplicate legal standards already in effect on the international level. Nevertheless, its approval by the conference, which represents a broad spectrum of Yemeni society, suggests the extent of domestic opposition to targeted killings.

AQAP has also been quick to capitalize on that anger. In a 2013 issue of Inspire magazine the group wrote that the “real” target of US drones is not terrorism but Islam:

In Yemen, they roam over Muslim houses, terrorizing children, women and the weak. Moreover they bombard “suspected” targets in villages, towns and cities … without the need to identify the real identity of the target, whether Al-Qaeda or not. … Obama is declaring a crusade! These missiles have no eyes and their launchers are more blind [sic]. They kill civilians more than mujahideen.[77]

Another factor contributing to backlash is that many Yemenis seem to fear the US airstrikes and Yemeni military and police forces more than they fear AQAP.[78] During the country’s 2011 uprising, Yemen’s military and police forces killed numerous protesters or otherwise used excessive lethal force against largely peaceful protests. This does not discount the many serious abuses committed against civilians by AQAP and Ansar al-Sharia. But the available evidence suggests that the vast majority of the hundreds of people killed by AQAP since its inception are members of the Yemeni security forces.[79]

US Long-term Counterterrorism Strategy for Yemen

If the United States considers Yemeni popular support to be important in its operations against AQAP, reducing civilian casualties should be a top priority, regardless of whether the civilian deaths were the result of violations of international law.[80] The United States learned this lesson after US and NATO airstrikes against Taliban forces killed hundreds of civilians in Afghanistan. As the senior US military commander in that country acknowledged in 2010: “If we kill civilians or damage their property in the course of our operations, we will create more enemies than our operations eliminate.”[81]

In his May 2013 speech on counterterrorism policy, President Obama said the next phase of countering violent militancy “involves addressing the underlying grievances and conflicts that feed extremism.”[82]

Several Yemeni and Western political analysts and civil society activists who spoke to Human Rights Watch concur, arguing that any counterterrorism strategy in Yemen also requires a sustained commitment to addressing the factors that make the country fertile ground for violent militancy. That means fostering democracy and a more accountable government, and increasing access to basics such as water, health, education, and jobs.[83]

“The United States doesn’t need drones to fight AQAP,” said Nashwan al-Othmani, an Aden-based journalist and political activist. “Just bread and cheese.”[84]

But social and economic issues are only part of the equation if they ignore the political grievances and government repression that also fuel support for militancy. The United States and other concerned governments should press the Yemeni government to adopt measures to end human rights violations by all government and allied forces and hold perpetrators to account.

In 2012, the US government for the first time provided more development assistance than overt security assistance to Yemen—$198 million US for economic and humanitarian aid compared to $158 million for counterterrorism and other security assistance.[85] At the same time, the United States continued to support a blanket amnesty for former president Saleh and all his aides for any political crimes they may have committed during Saleh’s 33-year presidency—part of a deal to usher Saleh out of power, while continuing targeted killings in Yemen. In mid-2013, the United States also predicted that the war on terrorism would continue for years.[86]

II. Case Studies

1. Wessab: Strike on Alleged Local AQAP Leader

On April 17, 2013, two US drones flying over Wessab, a remote district perched on some of Yemen’s highest mountains, fired at least three Hellfire missiles at a car carrying an alleged local AQAP leader, Hamid al-Radmi, also known as Hamid al-Manea or Hamid Meftah.[87] The attack killed al-Radmi, his driver and two bodyguards.[88]

Zainab Yahya Nasser al-Salf holds a photo of her son Hamid al-Radmi, an AQAP suspect and former military officer who was killed in a drone strike in Wessab on April 17, 2013. © 2013 Farea al-Muslimi for Human Rights Watch

Government officials described al-Radmi as a local AQAP leader and recruiter. He spent a decade in prison—four years starting in 1995 for killing his cousin, and six years starting in 2004 on a terrorism-related conviction.[89] One friend said al-Radmi was among the many Yemenis who traveled to Iraq to support domestic insurgents following the US-led invasion of that country in 2003.[90]

At the same time, he was one of Wessab’s most influential figures, moving openly throughout the area. Al-Radmi met regularly with security officials at government offices just a few minutes’ walk from his house and was returning with a local official from a meeting an hour’s drive from his home when he was killed.[91]

The nature of al-Radmi’s alleged involvement with AQAP, possibly not involving any operational military role, raises questions about the lawfulness of the attack under the laws of war. Participating in recruiting would not in itself make an individual subject to attack.

Killed Near Government Building

Al-Radmi was killed as his vehicle approached the outskirts of his village, Mathab, after mediating local disputes in the community of Bani Hafs. Around 8:30 p.m., at least two missiles struck al-Radmi’s four-wheel drive vehicle, instantly killing al-Radmi, 35; his driver Akram Ahmed Hamoud Daer, 20; and a bodyguard, Ismail al-Magdishi, 28. A second bodyguard, Ghazi al-Emad, 28, died later that night from his injuries.[92]

Residents said they saw two drones overhead at the time of the strike and that a third drone flew in immediately after the attack.[93] Human Rights Watch found the damage to al-Radmi’s four-by-four consistent with a drone strike and identified the remnants of the weapons launched as Hellfire missiles.[94]

The website of Yemen’s newspaper 26 September, a mouthpiece for the Ministry of Defense, confirmed an “airstrike” against al-Radmi but did not say what weapons or forces were involved.[95] An official with Yemen’s Minister of Interior, whose name was not published, told China’s Xinhua news agency that the strike involved two missiles launched from an “unmanned warplane” and that it was “a joint military operation” involving “Yemeni, US and Saudi intelligence services.”[96]

Drones had been sporadically hovering over Wessab since al-Radmi’s return to his village in 2011. Still, some residents initially thought they were hearing an explosion related to construction of the area’s first paved road. Running outside after the first blast, villagers saw at least one more missile fly toward the area of the strike.[97]

At that point, scores of villagers began rushing down a winding dirt road toward the flaming vehicle. As they approached, they saw al-Radmi’s charred body half ejected from the vehicle, two other charred corpses inside, and a fourth man outside the car.

Ahmad Hamoud Qaed Daer, the father of al-Radmi’s driver, was among those first at the scene. He told Human Rights Watch:

The fire was high; no one dared get close and the planes [drones] were hovering above. I also heard someone saying, “I'm Ghazi al-Emad, please help me.” I couldn’t do anything.… It was dark and there was a lot of smoke. There was no moon and I didn't even have a flashlight. I saw my son, charred, in the front seat. … I didn’t even know that he was driving for Hamid that day.[98]

A third drone appeared, residents said, increasing the panic. Some villagers tried to brave the fire to rescue Emad, including Shafiq Muhammad al-Magdishi, the brother of the other bodyguard killed in the strike:

His [Emad’s] legs were cut off from the knee down and there was a lot of blood coming from his mouth. We saw later that his stomach was bleeding as well and his eyes were burned. He couldn’t open them and was blinded. He was screaming and then his voice slowly dropped. It became lower, lower, and lower until he couldn't talk.[99]

Qaed al-Farimi, a prominent resident of Wessab and friend of al-Radmi’s, said the blast “terrorized the people,” stoking anger:

People were going to their roofs and screaming … and cursing, "Who is this bombing at night? [Expletive] his father!” They [the blasts] terrified even children and women. Some ran out of their houses and some ran to the basements to hide where their cows live because of the fear.[100]

Even the second day, the planes [drones] were there until we buried them. I swear by Allah if we had had weapons, not a single plane would leave. We would take them down because they terrified the village.[101]

“I Could Have Arrested Him”

Al-Radmi reportedly commanded the loyalty of many armed men and lived in a fortress-like house atop a steep cliff. Even so, residents and security officials said he could have been arrested at any time after he returned to Wessab in 2011 upon his release from prison.[102]

“He was in my office all the time and I could even have gone to his house to arrest him,” said one ranking security officer in Wessab who knew al-Radmi. The official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said he had never received any order for al-Radmi’s arrest. A second local security official echoed those comments.[103]

Al-Radmi traveled only with a driver when he went to local government offices, less than one kilometer from his house, and even went to the local courthouse to intercede on behalf of residents, a friend said.[104] Al-Radmi’s mother also that local government offices were “next to us and he used to go there all the time.”[105]

So open were al-Radmi’s movements that on the day he was attacked he had attended a qat chew with Mojahed al-Mosanif, the secretary-general of the Wessab government council, at a village an hour’s drive away where he was helping solve local disputes, residents said.[106] Al-Radmi and al-Mosanif also performed the Maghrib prayer together immediately after sunset, they said. When al-Radmi’s four-by-four was struck, al-Mosanif’s car was directly behind him. In addition, al-Radmi had been scheduled to meet three days after his death with the governor of Dhamar, the province that includes Wessab, to discuss local grievances.[107]

A Yemeni government official with knowledge of the strike, speaking on condition of anonymity, denied that al-Radmi could readily have been captured. Speaking of both al-Radmi and Adnan al-Qadhi, another alleged AQAP chief who was killed in a drone strike, the official said that in cases where the government has moved in armed forces to rout AQAP, they often are defeated:

They [al-Radmi and al-Qadhi] had strong tribal ties and the government is in no position to capture them or physically hold them for a while. The state is too weak right now. So what do you do? The easiest option is, you take them out. Because they are actively recruiting.[108]

Some residents suggested al-Radmi may have been killed because of his prominence or because he challenged local authorities. A week before the deadly strike, al-Radmi called on local officials to spend more revenues on public works and services, according to one friend, and “argued with them.”[109]

Relatives said that had authorities sought their help, they would have turned al-Radmi over to them. Relatives play an important role in administering justice in Yemen’s tightly knit family and tribal system.[110]

One cousin, an elderly farmer named Muhammad Ali Saleh, said the killing turned al-Radmi into a martyr:

They should have taken him to court, brother. Charge him and keep him in prison and even hang him there up and down every day but not kill him like that if he committed a crime. Now people are crying about him everywhere. What does that accomplish?[111]

Al-Radmi and AQAP

There are conflicting accounts of al-Radmi’s relationship with AQAP. Yemeni government officials called him a local AQAP “leader” who started a cell for the group upon returning to his home village of Mathlab, in Wessab district, with his wife and young son in 2011.[112] “He was building an AQAP mini-militia on the mountain,” the Yemeni government official with knowledge of the strike told Human Rights Watch.[113] Nasser Arrabyee, a Yemeni journalist from Wessab, reported that while in prison al-Radmi met Qasim al-Raymi, who went on to become the military commander of AQAP.[114] Security officials said al-Radmi helped hide wounded AQAP fighters in Wessab’s rugged mountains when they fled southern Abyan in mid-2012.[115]

A recent photo of Hamid al-Radmi. © 2013 Mareb Press

In 2012, local authorities searched al-Radmi’s home after he was rumored to around his house,” said al-Farimi, the prominent resident who was al-Radmi’s friend. Al-Radmi was “cooperative,” according to the ranking security officer. The authorities found no weapons apart from four Kalashnikov assault rifles, said the security officer and al-Farimi, who was part of the search committee.[116] Possessing four assault rifles “is a normal thing here,” the security official said.[117] Indeed, a household arsenal of that kind is not unusual in Yemen, the world’s second-most armed country after the United States.[118]

Several AQAP experts told Human Rights Watch they were not aware of al-Radmi being a military commander or otherwise playing a role in military operations for AQAP.[119] One acquaintance said al-Radmi received 60,000 Yemeni rials (US$280) per month from the group—a modest wage even in impoverished Yemen.[120] Being solely an AQAP recruiter without a direct military role would not make him subject to attack.

The Yemeni government official told Human Rights Watch that “it is not clear in some cases,” including those of al-Radmi and al-Qadhi, whether the targets of US strikes “are actually military commanders or operators of attacks. But they recruit openly, openly.”[121]

“Striking is not the most ethical position” in some of these cases, the official said. “But if you don’t strike them, will they recruit more? That is the debate.”

Whatever his role, al-Radmi did not advertise it, in contrast to top AQAP leadership who regularly pen articles or appear in videos. The majority of residents whom Human Rights Watch interviewed in Wessab said they had no idea that al-Radmi was a suspected AQAP member until he was killed.

Before he was imprisoned, al-Radmi had been an officer in Yemen’s Republican Guard, the now-disbanded military unit that had been commanded by former president Saleh’s son Ahmed Ali Saleh.[122] He was reputed to be friendly with ranking members of the General People’s Congress, the party founded and still headed by the former president.[123]

Most residents of Upper Wessab, the area of the township where al-Radmi lived, are subsistence wheat farmers and shepherds whose remote mountain villages have no electricity and few services. Residents describe the area as “forgotten” by central authorities: as noted above, Wessab’s road to the rest of the province was being paved for the first time at the time of al-Radmi’s death, and the last high-level visit was a campaign stop by a provincial official in 2003.[124]

Al-Radmi quickly filled the governance vacuum, gaining prominence as a mediator of disputes over issues such as property boundaries and water use.[125] Residents gathered “day and night” at al-Radmi’s house to seek his counsel and several were awaiting him there at the time he was killed, one friend said.[126]

AQAP’s offshoot Ansar al-Sharia also sought to provide assistance to inhabitants of areas it controlled in Abyan in 2011-12, but al-Radmi did not reject government authority; instead he intervened openly and directly with local and provincial officials on residents’ behalf.

No Compensation

If al-Radmi were not a valid military target, the guards traveling with him would not have been valid military targets either: there is no evidence that they themselves were AQAP fighters.

Al-Magdishi said his brother, a father of three, had been accompanying al-Radmi for some quick cash while awaiting answers on jobs he’d applied for elsewhere in the Gulf.[127]

Daer said his son, whose wife had just given birth to their first child, was driving for al-Radmi temporarily in the hope that in return al-Radmi would help him get into a military academy in Sanaa.[128]

The relatives said they had not received any compensation from the US or Yemeni authorities after their deaths.[129]

2. Al-Masnaah: Attack on Low-Level Militants

Hussain Jamil al-Qawli (left) holds a photo of his son Salim al-Qawli, 20; and Muhammad al-Qawli holds a photo of his brother Ali al-Qawli, 34. Salim and Ali al-Qawli were killed in a drone strike in al-Masnaah on January 23, 2013. © 2013 Letta Tayler/Human Rights Watch

On January 23, 2013, one or more missiles launched from a drone killed four people traveling in a sports utility vehicle (SUV) on a back road toward the town of Sanhan, about 20 kilometers southeast of Sanaa. Two of the passengers were alleged AQAP members. Neither was believed to be of high rank.[130] The other two men in the vehicle were cousins who by all accounts were civilians.

Depending on the military importance of the two targeted AQAP members, under the laws of war the strike on the vehicle may have caused disproportionate harm to civilians.

The missiles struck a Toyota Hilux SUV in the village of Masnaah, about five kilometers outside of Sanhan, at approximately 8:10 p.m., destroying the vehicle. The driver and all three passengers were killed. Multiple media reports identified two of the men as alleged AQAP members Rabee Hamoud Lahib and Naji Ali Saad. The other two men in the vehicle were Ali al-Qawli, 34, an elementary-school teacher and father of three, and his cousin Salim al-Qawli, 20, a college student who drove the borrowed Toyota as a car service to earn money for his family.[131]

A Human Rights Watch examination of photos of remnants of the ordnance and wreckage found the damage consistent with Hellfire missiles launched from a drone. Relatives of the killed civilians said they heard the whirr of drones—“like a big generator”— around the time of the attack.[132] Yemeni officials, speaking anonymously to local and international media at the time, also identified the attack as a drone strike.[133]

The al-Qawli cousins had traveled that afternoon with five friends and relatives from their hometown of Khawlan to Jihana, a nearby town that is a provincial transit hub, to chew qat. Around 7 p.m., they headed towards the parking lot of the central souk (market), which is also an area where drivers offer public transport. As they sat in the Toyota, the two cousins were approached by two strangers who offered them 10,000 rials (US$47) to take them to Sanhan, another town about 10 kilometers and a 45-minute drive from Jihana, according to two other relatives s who were with the cousins at the time.[134]

Salim al-Qawli had been driving the Toyota, which belonged to an uncle, to earn money for his parents, seven siblings, and a grandfather who required costly medical care for a heart attack and dementia, said his uncle Muhammad al-Qawli.[135]

The two relatives who overheard the conversation with the strangers said Salim al-Qawli jumped at the offer of a generous fare. The two strangers were wearing civilian clothes. Each carried a Kalashnikov, “but that is normal for people in this area,” said Abdullah Jamil al-Qawli, one of the relatives. The two strangers did not want anyone else to join them in the car, saying they were picking up other passengers en route. Around 8:10 p.m., as the al-Qawlis’ friends and relatives waited in Jihana for the cousins to return to bring them home, they heard an explosion that sounded like an airstrike.

Muhammad al-Qawli, the father of Ali al-Qawli, learned that his nephew and son were killed in the strike after a relative called him from the site and told him the vehicle’s tags were from 1982:

He [the relative] said, “The bodies are so charred I can’t recognize them.” I called the relative who owned the vehicle and asked, “What year is your car?” He said, “It’s a 1982.” He told me, “Ali and Salim took a fare to Sanhan and I am waiting for them to return.” That’s when I went into shock.[136]

Muhammad al-Qawli and other relatives drove to the site of the strike. There, he said, they found a horrific scene:

Many villagers were surrounding the car. The car was still burning. Body parts were spread across the area. Security forces came, the police and the Central Security Forces [which at the time operated a US-funded and trained Counter-Terrorism Unit]. All they did was remove the license plate of the car and take some photos and then they left. They did not even set up a roadblock. The bodies were burned like animals and none of them even attempted to help. I screamed, “Guys, be human!” and started throwing sand at the fire.[137]

Muhammad al-Qawli and Hussain Jamil al-Qawli began crying as they told Human Rights Watch how relatives only recognized Ali al-Qawli by his teeth and Salim al-Qawli by a patch on his pants, which were still on one leg that was severed from his body.[138]

The sports utility vehicle that was hit in a drone strike in al-Masnaah on January 24, 2013, killing two alleged AQAP members and two civilians. © 2013 al-Qawli family

Government Response

When the al-Qawlis’ relatives returned the next day to try to retrieve the bodies, they found them gone—the authorities had taken them to Sanaa. Enraged, about 200 residents from the cousins’ hometown and surrounding areas blocked roads for two days, refusing passage to all government vehicles.

The response of Abd al-Ghani Jamil, the governor of Sanaa province—which includes the site of the strike in al-Masnaah—was an offer and a threat, according to Muhammad al-Qawli:

Abd al-Ghani Jamil said, “Either you accept $20,000 [US] for each body or we will call them al-Qaeda.” We got the bodies back in return for lifting the roadblock. We buried them and after that no one [from the government] asked us about them anymore. If they gave out the money it must have gone to tribal leaders as we did not receive a penny.[139]

The brother and father showed Human Rights Watch a letter, dated February 9, 2013 from Yemen’s Interior Ministry, saying the two al-Qawli cousins were innocent. Salim and Ali al-Qawli “did not have any knowledge of or contact with the individuals who asked for a ride, but they happened to die alongside [them],” the letter said.[140] The relatives said that was all they ever received from the government.

The relatives said they later heard from well-placed sources that the two AQAP suspects were coming from Mareb, a province to the east, where they had attended a funeral for alleged AQAP members killed in a separate targeted killing.

Lahib reportedly had survived a drone strike the previous November that killed an AQAP suspect and his bodyguard in Beit al-Ahmar, a village about 10 kilometers from al-Masnaah. He was reportedly involved in detaining an 8-year-old boy and his father for AQAP, which subsequently released a video in which the two allegedly “confessed” to setting up the Beit-al-Ahmar strike.[141] A Swedish journalist who investigated the attack wrote that Lahib lived in a village an hour’s drive from the capital and traveled every other day to Sanaa, passing military checkpoints en route. It is not clear why Yemeni forces did not capture him at a checkpoint on his frequent trips into Sanaa.[142]

Asked if their views of the United States had changed as a result of the attack, Muhammad al-Qawli replied: “We respect the US people but we hate the US government very much. We want a US or international trial into what happened to Ali and Salim.”[143]

3. Beit al-Ahmar: Strike on Local Leader, Child Detained

“Would the Americans accept it if a Yemeni warplane came and killed Americans without any judicial process?”

– Himyar al-Qadhi, brother of Adnan al-Qadhi, who was killed in a drone strike in November 2012

On November 7, 2012, a drone strike killed Adnan al-Qadhi, a 40-year-old tribal leader and a lieutenant colonel in an elite Yemeni military unit, as he was standing in front of his car in his hometown of Beit al-Ahmar. The strike also killed one of al-Qadhi’s bodyguards.

The attack raises concerns under the laws of war about whether al-Qadhi was a valid military target and whether Yemeni military officials unlawfully used a child to facilitate the attack.

Adnan al-Qadhi, a lieutenant colonel in Yemen’s First Armored Division and alleged AQAP member, was killed in a drone strike in Beit al-Ahmar on November 7, 2012. © Private

There was little doubt of al-Qadhi’s sympathies: one side of his house in Beit al-Ahmar bore a giant black AQAP flag. Moreover, AQAP released a video in April 2013 depicting al-Qadhi as a “martyr.” At times al-Qadhi negotiated with AQAP on behalf of local tribes and the Yemeni government.

AQAP responded to the killing by capturing and detaining a Yemeni soldier and his 8-year-old son who AQAP claims were involved in the airstrike. The group issued a video in April 2013 in which the father and son “confessed” that three government military officers recruited the boy to plant an electronic tracking device on al-Qadhi. At the time of writing, neither father nor son had been released and there were grave concerns for their safety.

His Last Word was “Marhaba!” (“Hello!”)

A missile killed al-Qadhi at approximately 6:45 p.m. as he was standing outside his car on a hilltop, talking to his wife on his cellphone after eating dinner at a nearby farmhouse.

“His wife heard his last word, ‘Marhaba!’ [Hello!],” his brother Himyar al-Qadhi told Human Rights Watch. “He always said ‘Marhaba’ when he was surprised.[144]

Witnesses said one drone was circling overhead and a second drone arrived shortly before the attack. Photos of the remnants examined by Human Rights Watch were those of Hellfire missiles, consistent with a drone strike. Yemeni and international security media also described the attack as a drone strike.[145] The attack could not have been carried out by Yemeni forces because, as President Hadi confirmed in 2012, Yemeni air force jets cannot fly at night.[146]

Al-Qadhi died instantly. His friend and bodyguard Radwan al-Hashidi, a local sheikh who was sitting in the front seat, was pronounced dead on arrival at a nearby hospital.[147] Rabee Hamoud Lahib, a suspected AQAP member, had been traveling in the car earlier but missed the attack.

Arafat Ali Maqsa, a resident of Beit al-Ahmar, was driving home from a wedding when he heard the explosion:

The force of the blast was so powerful that my car trunk shook even though I was still about 400 meters away. I saw smoke. I thought it was a gas explosion. What I saw next was unimaginable. Adnan was dead. His friend was hit by metal fragments in his mouth. He was still speaking when we arrived. As we took him out of the car he breathed his last.[148]

Himyar al-Qadhi holds remnants of a Hellfire missile that killed his brother, Adnan al-Qadhi, in Beit al-Ahmar. © 2013 Farooq al-Sharani

Lieutenant Colonel and AQAP Sympathizer

By all accounts, al-Qadhi moved freely within elite political and military circles even as he retained ties with AQAP.

Al-Qadhi served more than two decades in the First Armored Division, one of the country’s elite military units until its disbandment in 2013. He held the rank of lieutenant colonel and was receiving 125,000 Yemeni rials (US$583) a month in military pay at the time of his death, Himyar al-Qadhi said. The son of a prominent family, he knew former president Saleh, whose palace is in his Beit al-Ahmar neighbored, and, like the president, was a member of the powerful Sanhan tribe. His cousin, Muhammad al-Qadhi, is a member of parliament. Before joining the First Armored Division, al-Qadhi was among hundreds of Yemenis who fought in Afghanistan during the 1980s alongside the CIA-backed mujahideen.[149]

Even as he moved in high-level government circles, al-Qadhi was widely viewed as an AQAP sympathizer and possible recruiter. Abd-al-Razzaq Ahmad al-Jamal, a Yemeni journalist who is an expert on AQAP, interviewed al-Qadhi 20 days before his death:

Adnan invited many members of Ansar al-Sharia [an offshoot of AQAP] as guests to his house. When I asked him if he was a member of AQAP he said, “This is an honor I do not have.” But I think he just wanted to be humble. AQAP in their video [about his death] recognized him as a member.[150]

Al-Jamal said that he did not believe al-Qadhi played an operational military role with AQAP. Not only is there no evidence of al-Qadhi fighting on behalf of AQAP, in January 2012 he played a key role in negotiating AQAP’s retreat from the central Yemeni city of Radaa, which AQAP fighters had seized days earlier. Al-Qadhi led a 20-member tribal delegation to persuade AQAP’s Radaa leader, Tariq al-Dahab, to withdraw. Himyar al-Qadhi told Human Rights Watch:

Adnan told Tariq al-Dahab, “Listen, we know that the government is not being fair, we know that people here are being oppressed. But you have to get out of Radaa because if you don’t the Americans will take control of our weak government.”[151]

As noted above, a Yemeni government official with knowledge of the attacks on both al-Qadhi and Hamid al-Radmi (whose case is discussed above) said that it was not certain that either were actual AQAP military commanders but that both had recruited for AQAP.

In 2008, the Yemeni authorities detained al-Qadhi for six months in connection with a suicide bombing at the US Embassy in Sanaa earlier that year, linking him to license plates on one of the attackers’ cars. That attack killed 17 Yemenis and one Yemeni-American.[152] Al-Qadhi was released without charge; the reason for his release is not clear.

Yemenis who knew al-Qadhi or had followed his targeted killing case offered an array of theories about why he was killed; none involved his participation in military operations.

One Yemeni with close connections to Beit al-Ahmar and the surrounding township of Sanhan said that al-Qadhi and Lahib, the suspected AQAP member who escaped the strike, were part of a group who had tried to create a roadblock the previous Ramadan (July 20-August 18, 2012) to stop former president Saleh’s son Ahmed Ali from stashing weapons in Beit al-Ahmar. At the time, Ahmed Ali was the commander of the elite Republican Guard but was being stripped of his powers by President Hadi; opposition media accused him and other Saleh relatives of looting weapons during the latter half of 2012.[153] A Yemeni analyst took the opposite view, saying al-Qadhi was killed “for working not in favor of extremist groups but against the current regime.”[154]

Other Yemenis considered the strike a warning to the former president and his loyalists, who have been accused by the UN Security Council of trying to thwart Yemen’s transition, that Beit al-Ahmar was no longer a safe-haven for the Saleh family.[155]

Opportunity to Capture

Under the Obama administration’s policy on targeted killings, strikes are only to be carried out if capture is not feasible.

Beit al-Ahmar, located 15 kilometers southeast of Sanaa, is home to one of the highest concentrations of political and military authority in Yemen. It is the hometown of three of Yemen’s most powerful figures: former president Saleh, Saleh’s son Gen. Ahmed Ali Saleh, and Gen. Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar. At the time of al-Qadhi’s death General al-Ahmar commanded the First Armored Division, the unit to which al-Qadhi belonged.

“The concentration of police and military personnel in Sanhan [the town that includes Beit al-Ahmar] is one of the highest in the country,” said Abdulghani al-Iryani, a Yemeni political analyst. “To say that the government could not reach that place and make a capture there is absurd.”[156]

Al-Qadhi moved freely in Beit al-Ahmar and surrounding areas. He was in Sanaa as recently as four or five days before he was killed and had to pass several checkpoints to get from the capital to Beit Al-Ahmar, relatives said.[157] The fact that al-Qadhi was on the military payroll gave the authorities any number of potential ruses to lure him in.

Yemeni officials said President Hadi approved the strike against al-Qadhi after determining that an attempt to arrest him in his village could have led to more deaths, according to the Los Angeles Times.[158] Certainly, Beit al-Ahmar is a potential political powder keg, packed with armaments and animosity: one of its native sons, General al-Ahmar, defected to the opposition with his First Armored Division during Yemen’s 2011 uprising and is a bitter rival of the former president and his son Gen. Ahmed Ali Saleh, the then-commander of the Republican Guard.[159]

While capture may have been complicated, it should under the US policy have been seriously considered.[160] Beit al-Ahmar had weathered other political storms without bloodshed. As Yemen-based journalist Adam Barron wrote in 2012: “Even after many of the area’s most powerful sons broke ranks in the revolt against Saleh last year—a time marked by bloody clashes in the capital—the village had remained calm until the American drone strike.”[161]

Even if US and Yemeni authorities had ruled out capture because of potential revenge attacks, a negotiated surrender was still possible, many security and political observers said.[162] Moreover there was precedent: relatives had previously surrendered al-Qadhi when he was sought in connection with the US Embassy bombing.

“When the security forces called me and said, ‘Adnan is a suspect,’ I handed him over with my own hands,” Himyar al-Qadhi said. “I swear to God if they had asked us to bring him in again we would never have said no.”

On February 5, 2013, Himyar al-Qadhi filed a complaint with the Yemen’s General Prosecution Office accusing President Hadi, President Obama, and other top Yemeni and US officials of murder for the strike on his brother. The following month, he said, his house was raided by Yemen’s Counter-Terrorism Unit, a force trained and funded by the United States. Now, he said, he fears for his own life.[163]

Backlash and Detention of 8-Year-Old “Spy”

Al-Qadhi’s killing created widespread anger within the Sanhan tribe, one of the most influential in Yemen. AQAP expert and journalist al-Jamal said:

Relatives and members of his tribe are angry. In their songs and poems, the tribes have threatened to join al-Qaeda in revenge. Here when America is our enemy you are a hero. It makes al-Qaeda look good and gains the sympathy of the people.[164]

Himyar al-Qadhi said, “The US is planting the seeds of terrorism with such killings. If you believe you got rid of Adnan, well now you’ll have 1,000 Adnans. This is not hard to understand.”

AQAP released a video in April 2013 that depicted al-Qadhi as a “martyr,” indicating that they considered him a member of their group.