Summary and Key Recommendations

Since 2008, the government of Azerbaijan has undertaken a sweeping program of urban renewal in Baku, the capital of this oil-rich country in the South Caucasus. In the course of this program, the authorities have illegally expropriated hundreds of properties, primarily apartments and homes in middle-class neighborhoods, to be demolished to make way for parks, roads, a shopping center, and luxury residential buildings. The government has forcibly evicted homeowners, often without warning or in the middle of the night, and at times in clear disregard for residents’ health and safety, in order to demolish their homes. It has refused to provide homeowners fair compensation based on the market values of properties, many of which are in highly-desirable locations and neighborhoods.

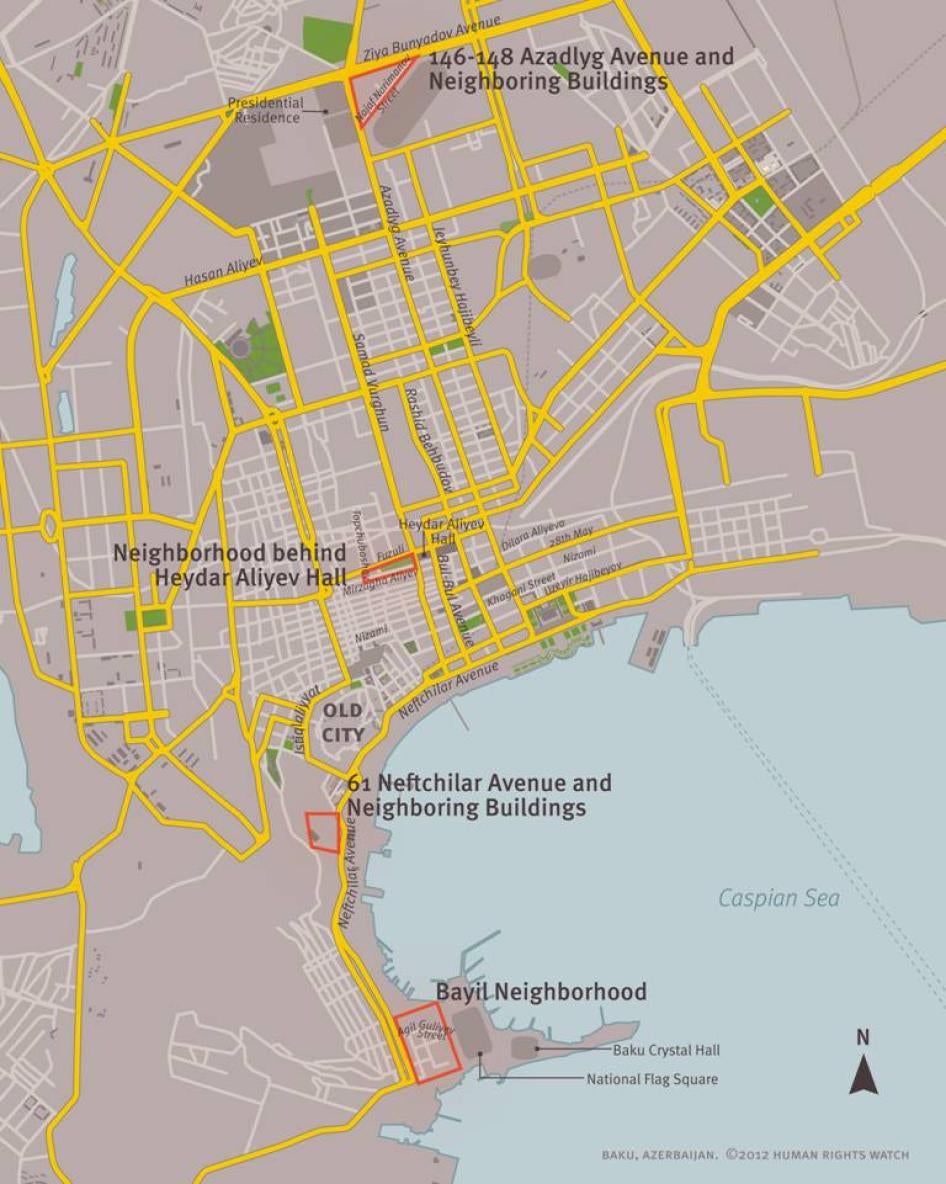

This report, based on interviews with affected homeowners and residents, documents human rights violations committed in the course of the government’s expropriations, forced evictions, and demolitions in four neighborhoods of Baku. These neighborhoods have typically been home to middle class Azerbaijanis: teachers, librarians, medical doctors, military officers, and others, some of whom have inherited their homes from their parents and others who managed to save and buy apartments in desirable locations. The human rights violations documented by Human Rights Watch relate to the process by which homes and properties were slated for expropriation and compensation was assessed, the manner in which expropriations, evictions, and demolitions were implemented, and the lack of any effective legal recourse or remedy available to those whose rights were violated.

One of the four neighborhoods described in this report is Bayil, the seaside location of the National Flag Square and the Baku Crystal Hall, the venue for the May 2012 Eurovision Song Contest. The government’s ambitious plans to develop this area intensified after May 2011, when Azerbaijan won the contest and therefore became host to the 2012 event. The Eurovision Song Contest is an annual televised competition featuring music acts from 56 countries in and around Europe. For the government of Azerbaijan, the visibility of the event provides an opportunity to showcase Baku to thousands of visitors and millions of television viewers.

The main venue for the contest will be the Baku Crystal Hall, a modern, glass-encased arena overlooking the Caspian Sea. The government has also stepped up work on other, previously planned projects in the immediate vicinity, including extending a waterfront promenade that begins in the city center; extending and widening a road parallel to the coast; and creating a park on the opposite side of the National Flag Square from where the Baku Crystal Hall is being built. In order to clear land for construction of the road and the park, the government has forcibly evicted several hundred residents from the Bayil neighborhood.

The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights considers forced evictions to be the “permanent or temporary removal against their will of individuals, families and/or communities from the homes and/or land which they occupy, without the provision of, and access to, appropriate forms of legal or other protection.” Evictions and expropriations may be lawful when they are conducted in exceptional circumstances, and in full accordance with relevant provisions of international human rights and humanitarian law. Forced evictions are prohibited under Azerbaijani and international law.

The Baku City Executive Authority and the Azerbaijan State Committee on Property oversee the expropriations and forced evictions documented in this report. Once the authorities have identified a property for expropriation and demolition, the government typically offers monetary compensation or resettlement to the residents. However, not all homeowners receive compensation or resettlement offers or accept the government’s offers. They therefore remain in their homes. When the authorities arrive to demolish the homes, they forcibly evict the remaining homeowners and their families.

The authorities often carry out evictions and demolitions with willful disregard for the dignity, health, and safety of homeowners and residents. In at least 24 cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the authorities have dismantled from the inside apartment buildings or houses in which families and individuals continue to live, including by removing roofs, doors, windows, and stairwell banisters, and damaging shared walls. This often exposes residents to the elements and to the risk of partial collapse of buildings. In many cases, the authorities have also cut water, sewer, electricity, gas, or telephone lines while homeowners remained in their homes. These actions also render the properties uninhabitable, ultimately compelling the residents and homeowners to move out and accept unfair compensation offers.

When Viktor Karmanov, a retired military officer, and his wife Iveta learned in July 2011 that their building next to the National Flag Square, where they had lived for 20 years, would be demolished, they were not satisfied with the compensation offer and contacted the authorities, hoping to negotiate a better sale price. However, a little over a month later, the authorities had destroyed much of the building, including the roof, and in late September they cut the electricity and phone lines.

“We did not want to sell our apartment,” Iveta explained. “But we have to sell now because it’s impossible to live here anymore. They broke down the roof so when it starts raining outside, it rains in our apartment too. … We begged them to at least leave the roof over our heads until we find someplace else to live, but they refused.”

In some cases, the authorities have forcibly evicted residents with little or no notice immediately prior to demolishing their houses or the apartment buildings. In some cases, large numbers of police and other government officials would surround the buildings and fill the stairwells before forcibly entering apartments and removing residents by force. In at least two cases, officials arrived without warning with a bulldozer and other machinery at night or in pre-dawn hours and began actively demolishing homes after telling homeowners to vacate immediately. In all of these cases, homeowners had a few hours or less to remove their personal belongings and valuables.

For example, without warning the authorities forcibly evicted Arzu Adigezalova, 41, a math teacher and a single mother of two young children, from her apartment next to the National Flag Square in the pre-dawn hours of October 29, 2011. Adigezalova had agreed to the forced sale of her apartment two weeks previously but had not yet found another place to live. She told Human Rights Watch:

I woke up because the building was shaking and I could hear something like thunder. I took the kids and went outside. [I went up to] the official in charge and asked him to give us time to take our belongings out. He looked at me and said, ‘Ok,’ but then in the next moment said to the bulldozer driver, ‘Break it down!!’

Adigezalova frantically tried to collect her belongings and take them out of the building. She lost many of her household goods and much of her furniture.

In three cases documented by Human Rights Watch police escalated the evictions process by detaining homeowners in a police station following their eviction while the authorities demolished the apartment building.

For example, in December 2010 police forcibly evicted and detained 42-year-old Perviz Emirov, a retired soldier who was wounded while serving in the military and receives a disability pension, Emirov’s wife, and their three school-age children from their small one-room apartment in the neighborhood near Baku’s Old City. Emirov described the eviction to Human Rights Watch:

About four or five police officers broke down the door. ... I only had time to grab our identity documents and the little bit of money that I had at home, nothing else. They put me, my wife, and my daughter in the police car and took us to the police station. About 30 minutes later our twin boys came home from school . . . . Then the police brought them to the station as well. They let us go after about five hours. When we got our home, we couldn’t believe our eyes. Everything was destroyed. To this day I don’t know where our belongings are.

As part of the demolition process, workers typically remove furniture, household goods, and other personal property, placing items on the street or in some cases taking them to a warehouse for owners to recover later. Property owners complained that many of their belongings were damaged, destroyed, or lost during the evictions. Some homeowners were unable to recover personal property that remained in the building as it was demolished.

Dozens of homeowners filed complaints with the courts, but the authorities’ repeated failure to appear for hearings has caused these proceedings to be delayed for months at a time. In several cases the authorities have demolished homes in violation of court injunctions prohibiting demolition or while court cases challenging the intended demolitions were pending.

When governments expropriate private property for state needs, they must provide a fair and transparent process for compensation that reflects market value of the property as well as compensation for relocation and other expenses. However, the Azerbaijani authorities have offered some homeowners, typically those with homes smaller than 60 square meters, monetary compensation at a single, government-fixed rate of 1,500 manat (US$1,900) per square meter, without regard to the property’s location, age, condition, use, or any other factors. Homeowners were not aware of any independent appraisals of their homes ordered by the government, and the government has not responded to several inquiries by Human Rights Watch as to whether it conducted independent appraisals of homes.

For owners of homes larger than 60 square meters, the government offers homeowners resettlement to apartments built in high rises, typically outside of the city center. However, it does not give them ownership title to these apartments prior to their relocation, instead promising ownership at a later, unspecified date. In addition, photographic evidence and testimony from those living or expected to live in the new apartments indicate that the quality of at least some the apartments, and the buildings themselves, is low and possibly in violation of building code standards. Problems include standing water in the basement, cracks in walls, including load bearing walls, unfinished windows, and peeling and damaged floors.

Some homeowners described to Human Rights Watch an atmosphere of intimidation and uncertainty when interacting with government officials regarding the expropriation and demolition of their homes. Some government officials have threatened homeowners who challenge the government’s actions or refuse to readily accept the government’s compensation offers.

The government’s campaign of expropriations, evictions, and demolitions of homes and other property in Baku has no basis in national law, which provides that the government may only expropriate property in limited circumstances for state needs, with a court order, and by purchasing the properties at market prices. The government’s actions also violate Azerbaijan’s international human rights obligations, including its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights, to protect private property and private and family life. In some cases of forced eviction, the government’s actions, including serious disregard for the welfare and property of evictees, may rise to a level of severity so as to constitute inhuman and degrading treatment.

The Azerbaijani authorities should halt all further evictions, expropriations, and demolitions until they can be carried out in a fair and transparent manner and are consistent with Azerbaijani national law and international human rights law. The government should also ensure that any future evictions of homeowners who refuse to leave their properties are carried out with full respect for the safety and dignity of those evicted. Compensation for expropriated properties should be fair and based on the market value of each property, determined by an independent appraisal.

Azerbaijan’s international partners, including key governments and multilateral development banks, should insist that the government stop its campaign of expropriation and evictions and ensure that any future actions respect national and international law. Azerbaijan’s international partners also should call on the government to urgently establish a fair and transparent mechanism to resolve the complaints of evicted homeowners and residents and to reassess the compensation offered to those who lost their homes and possessions. The European Union and United States have an additional important role to play in continuing to support nongovernmental organizations and other groups in Azerbaijan that are documenting human rights abuses in the context of the government’s expropriations and evictions.

Other actors also should speak out to press for an end to forced evictions and related abuses until they can be done in a legal and fair manner and for a remedy for those already affected. Irrespective of the fact that the Eurovision Song Contest is a cultural, not a political, event, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), which oversees the contest, should make clear to the government that the serious violations of human rights that are taking place in relation to families, homes, and properties near the contest venue risks casting a shadow over the contest. Citing their mutual interest in holding a successful event not marred by human rights abuses, the European Broadcasting Union should urge the government to quickly and fairly resolve all complaints related to expropriations, evictions, and demolitions near the Baku Crystal Hall.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Azerbaijan, including the Baku City Executive Authority and the State Committee on Property

- Halt all further expropriations, evictions, and demolitions until they can be carried out in a fair and transparent manner and are consistent with Azerbaijani national law and international human rights law.

- Any future evictions of homeowners who refuse to leave their properties should only be conducted in accordance with Azerbaijani and international law. Any evictions should be regulated by a court order and conducted with full respect for the bodily integrity and dignity of those evicted. The authorities should in no circumstances begin to demolish or disassemble buildings in which people continue to live.

- Reassess the compensation offered to those who lost their homes and possessions.

- Ensure protection of all private property when carrying out evictions and demolitions.

- Provide homeowners and property owners who may lose their property for development with clear information about the legal basis for the expropriation, the timing of the expropriation, their compensation and resettlement options, and the means of appealing decisions. This information should be provided in a timely manner.

- Provide all property owners affected by expropriation access to an effective complaint mechanism that addresses grievances in a clear and transparent manner and a remedy.

- Ensure that mechanisms to provide property owners with compensation for expropriated property are fair and transparent, with a clear basis in law.

To the Prosecutor General’s Office of Azerbaijan

- Initiate an independent inquiry into why the expropriations and demolitions in central Baku have been allowed to take place in the manner described in this report given that they clearly violate Azerbaijan's constitution and national laws and international human rights law.

To the European Broadcasting Union

- Call on the government of Azerbaijan to quickly and fairly resolve all complaints related to expropriations, evictions, and demolitions near the Baku Crystal Hall.

- Call on the Azerbaijani authorities to ensure that no further human rights abuses take place with respect to Azerbaijan’s preparation to host the Eurovision Song Contest, including in the vicinity of the Baku Crystal Hall.

To the European Broadcasting Union Members

- Call on the EBU, including the Eurovision Reference Group, to make clear with the Azerbaijani authorities that expropriations, evictions, and demolitions near the Baku Crystal Hall risk casting a shadow over the Eurovision Song Contest and should be halted.

To Azerbaijan’s Bilateral Partners, including the European Union, individual European States, and the United States

- Insist that the Azerbaijani authorities halt all further expropriations, evictions, and demolitions until they can be carried out in a fair and transparent manner and are consistent with Azerbaijani national law and Azerbaijan’s international human rights obligations.

- Make Azerbaijan’s addressing these concerns an explicit requirement in the context of enhanced relations, including through the Association Agreements with the EU and in the context of deepening engagement with and assistance from the US.

Methodology

In June 2011, Human Rights Watch began preliminary research to examine the government’s campaign of expropriations, evictions, and house demolitions in Baku through a number of telephone interviews with victims, a lawyer, and human rights defenders in Baku. Subsequently, Human Rights Watch undertook research trips to Baku in June, September, and December 2011 and in January 2012 to interview property owners and other residents, lawyers, and NGO representatives in Baku.

Human Rights Watch interviewed a total of 67 people for this report. We interviewed 52 people subject to expropriations, forced evictions, and house demolitions, who were living or who had lived in four areas in Baku. Some individuals were interviewed twice or three times in order to document the most recent events related to the expropriation, eviction from, and demolition of their homes.

The locations in which Human Rights Watch documented abuses are:

- in a group of streets located behind the Heydar Aliyev Hall, bounded by Samed Vurghun, Fuzuli, Topchubashov, and Mirzagha Aliyev streets north of the historic Old Town;

- on Azadlyq Avenue near Ziya Bunyadov Street to the north of the city center, across from the presidential residence;

- on Neftchilar Avenue, in the city center, to the southwest of the historic Old Town, across the street from a well-known sports arena;

- and in the Bayil neighborhood, at the base

of a peninsula next to the National Flag Square, south of the city center.

The findings of this report relate to these four areas only. Although expropriations and house demolitions have taken place in other areas in the city and in other parts of Azerbaijan, Human Rights Watch is not in a position to assess the conditions and terms on which those precise expropriations took place.

Telephone and in-person interviews with victims were conducted in Russian by three Human Rights Watch researchers fluent in Russian and a consultant to Human Rights Watch fluent in Russian. Some interviews were conducted in Azeri, during which a translator for Human Rights Watch (a native speaker of Azeri) translated into English or Russian. An intern for Human Rights Watch conducted several telephone interviews with interviewees previously interviewed to get updated information.

In most cases victims and other interviewees were interviewed individually, in private. In a few cases married couples were interviewed together. Interviewees were offered no incentives for speaking with us. Human Rights Watch made no promises of personal service or benefit to those whom we interviewed for this report and told all interviewees that the interviews were completely voluntary and confidential.

Some individuals interviewed for this report said they feared possible retaliation from government officials for speaking with us. At their request, we have changed their names in the report. Pseudonyms appear throughout as a first name and an initial.

We also interviewed seven lawyers representing victims of illegal house expropriations, forced evictions, and demolitions. We met with representatives from the Public Association for Assistance to Free Economy, the Institute for Peace and Democracy, the Legal Education Society, the Association for the Protection of Women’s Rights in Azerbaijan, the Azerbaijan Human Rights Center, the Institute for Reporters’ Freedoms and Safety, the Human Rights Club and other local nongovernmental organizations working on property rights in Azerbaijan.

In June 2011 and September 2011, Human Rights Watch sent letters to Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and the Baku City Executive Authority expressing concern and requesting information about illegal expropriation, forced evictions, and house demolitions. On November 25, 2011, Human Rights Watch received a letter in response from the Baku City Executive Authority. Their response is reflected in the relevant sections of this report.

In December 2011, Human Rights Watch sent an additional letter to the Baku City Executive Authority and letters to the Ministry of Finance and the State Committee on Property. As this report went to publication, Human Rights Watch had not received responses from government agencies or the president’s office, except for the November 2011 letter. We requested meetings with the Baku City Executive Authority in December 2011 and in January 2012 but received no reply to our requests.

In September 2011, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) regarding concerns about selected human rights abuses Azerbaijan, including forced evictions and home demolitions linked to the government’s preparations for hosting the Eurovision Song Contest, as well as violations of freedom of expression and other human rights violations relevant to the EBU’s mandate.

The EBU responded with a letter to Human Rights Watch on November 10, 2011. An EBU representative met with Human Rights Watch in New York in November 2011. Human Rights Watch sent a second letter to the EBU on December 30, 2011. The EBU responded with a letter to Human Rights Watch on January 19, 2012. An EBU representative met with Human Rights Watch on January 25, 2012. The results of these meetings and correspondence are detailed in this report in the relevant sections.

I. Background

Azerbaijan’s Political Landscape

Azerbaijan is an oil-rich country located in the South Caucasus, with a population of 8.3 million.[1]Since gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Azerbaijan has had a poor human rights record and an increasingly entrenched, authoritarian political elite.Many hoped that the October 2003 election of President Ilham Aliyev–who took over after his now-deceased father, Heydar, who had held the office since 1993–would mark a new era of democracy and respect for human rights.[2] However, vote fraud, police violence, and intimidation of opposition supporters and others marred national polls in 2003 and in 2005.[3] Aliyev was re-elected in October 2008, but the opposition boycotted the vote and the elections failed to meet Azerbaijan’s international commitments.[4] In February 2009, a popular referendum initiated by Aliyev amended the country’s constitution to remove the two-term limit on the presidency.[5] In November 2010, international observers again found that the country’s parliamentary elections were marred by media restrictions, the misuse of administrative resources, and an inequitable candidate registration process.[6]

Azerbaijan’s judiciary depends heavily on the executive and fails to provide effective recourse against violations of basic rights.[7] Trial monitoring by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) found that trials regularly violate “the right to effective legal representation, the right to an impartial and independent tribunal, the right to a fair hearing, the right to assistance by an interpreter, and the right to a reasoned judgment.”[8] The ruling Yeni Azerbaijan Party (YAP) dominates the parliament (Milli Mejlis), which does not provide a check on executive power and largely serves to pass legislation proposed by the government.[9]

Corruption is endemic to government institutions and public interactions with government.[10] For example, a 2009 survey by the International Finance Corporation and the World Bank revealed that 52.2 percent of firms operating in Azerbaijan expected to give “gifts” to public officials to “get things done,” more than double the regional average. Seventy-one percent of firms expected to give gifts to get a construction permit, nearly three times the regional average.[11]

The government severely limits the rights to freedom of expression and assembly.[12] Officials regularly deny requests by opposition parties and others to hold demonstrations. Police quickly and often violently disperse unauthorized protests and arbitrarily detain participants. In 2011, when activists inspired by the uprisings in the Middle East launched protests in Azerbaijan, the government responded by arresting hundreds of protesters, activists, and journalists between March and May 2011.[13] Several of those arrested were convicted and imprisoned for up to three years.[14]

Hydrocarbon Wealth and Construction Boom

Azerbaijan’s hydrocarbon windfalls have helped to trigger a construction boom in Baku. In the last decade, Azerbaijan has experienced tremendous economic growth fueled by oil and gas exports. According to the World Bank, Azerbaijan’s Gross Domestic Product increased nearly 10 fold in less than a decade, growing from US$5.7 billion in 2001 to US$51.1 billion in 2010.[15] Azerbaijan is the twenty-second largest oil-producing country in the world and the third-largest oil producer in Eurasia, after Russia and Kazakhstan.[16] Azerbaijan produced just over one million barrels per day in 2010.[17] Azerbaijan is also the twenty-ninth largest producer of natural gas in the world.[18] So critical is the energy sector to Azerbaijan’s economy that, according to a 2010 International Monetary Fund (IMF) report, non-oil and gas exports at that time accounted for only five percent of total exports.[19] In its 2011 assessment, the IMF estimates that Azerbaijan’s hydrocarbon revenues will begin to decline after 2018.[20] The IMF has repeatedly pressed Azerbaijan to develop its non-oil economy and has said improvements in the business climate are crucial to sustained economic health.[21]

Given Azerbaijan’s current high per capita income, the country is no longer eligible for deeply discounted loans from international financial institutions designed for poor countries. Although Azerbaijan’s most recent IMF loan expired by 2005,[22] the IMF has remained engaged with Azerbaijan to offer policy advice. The World Bank’s loans to Azerbaijan, under a program for middle-income countries, were anticipated to reach US$300 million in the 2011-2012 fiscal year, while the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development invested US$79 million in projects in the country in 2010.[23]

Azerbaijan is a member of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), an international effort established in 2002 to improve transparency and governance in oil, gas, and mining. The central requirement of the initiative is that members—governments and the extractive industries in their countries—publish company payments and government revenues.[24] In 2009, Azerbaijan met a variety of criteria regarding revenue disclosure and in so doing was the first country to be declared “EITI compliant.”[25] Although Azerbaijan has filed regular and frequent reports to EITI, domestic civil society representatives that joined the process in 2010 have expressed concern that implementation of EITI has stagnated.[26] Their inability to secure improvements without the consent of the government and companies highlights one set of limits on the EITI as a mechanism for ensuring accountability.

More generally, Azerbaijan’s EITI membership only relates to the transparency of government income. EITI does not address how governments spend the money earned, nor whether they are transparent to their citizens about budgets and expenditures, so it cannot be used to monitor corruption or assess whether the funds from extractive industries are used to benefit the public.

This report does not address whether the extensive redevelopment of Baku is an appropriate government priority or examine whether specific construction projects are in the public interest.[27]

Eurovision Song Contest and Related Construction

The Eurovision Song Contest is an annual televised competition featuring one pop music competitor from each of 56 countries in and around Europe.[28] An estimated 125 million people watch the contest on television each year,[29] making it a major European cultural phenomenon.[30]

According to the contest’s rules, the winning act’s home country becomes the host for the next year’s event.[31] Thus, Azerbaijan became the host of the 2012 contest when its competitor, Ell & Nikki, won the competition in May 2011.[32] President Aliyev called the victory “a great success of the Azerbaijani state and people.”[33] The state-owned broadcaster in charge of producing the event in the host-country is Azerbaijan’s Ictimai TV.[34]

After winning the competition in 2011, senior government officials stated their desire to host the high-profile event in a brand-new venue, contingent only on whether construction could be completed in time. For example, in May 2011 shortly after the win, President Ilham Aliyev’s daughter, Leyla Aliyev, writing an editorial in a local magazine, described the construction in Baku ahead of the Eurovision as including a new complex for the song contest that would be “unlike anything before seen,” with “an amazing seaside panorama.”[35] Later in the year Azerbaijani media quoted Youth and Sport Minister Azad Rahimov as declaring: “The [Baku] Crystal Palace is under construction and I hope it will be ready by the contest and surprise the European community.”[36]

Consistent with this aim, work on the Baku Crystal Hall has proceeded at a quick pace.[37] In September 2011, a construction firm announced that it was building a “sports and concert complex” to accommodate some 25,000 spectators.[38] By early 2012 the roof had been installed on the arena, located near the end of a small peninsula jutting out into the Caspian Sea just east of the imposing National Flag Square, a vast, raised paved square home to a 162 meter flag pole.[39]

During this same period, the government has moved to clear homes and apartment buildings from the residential area at the base of the peninsula on the opposite side of the National Flag Square. The government demolished homes in that area to make way for the extension of a coastal road and also, just across from the National Flag Square, for a park, as suggested by a 2011 government document ordering beautification and greening in the area, as well as the size of the space and that new trees have been planted in the area.[40] Given its location and the timing of its construction, the new road seems likely to provide an important access route the area for large numbers of people attending the Eurovision Song Contest at Baku Crystal Hall; similarly the park will presumably serve as a scenic vista and entry point for visitors approaching National Flag Square and the Baku Crystal Hall for the that event, as well as functioning as a public space in the future.

On January 26, the reference group of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), which governs the Eurovision Song Contest, announced that it had approved the Baku Crystal Hall for the contest. Human Rights Watch has corresponded with and met with representatives of the EBU regarding concerns about government abuses in the Bayil neighborhood and other issues. (See below, the Role of Azerbaijan’s International Partners.)

As the issue gained foreign media attention—and with the EBU itself confirming that it sought explanations from the Azerbaijan government[41]—the authorities responded by attempting to de-link the evictions and demolitions from its preparations for the Eurovision Song Contest.

For example, in January 2012 the Azerbaijani media quoted Ali Hasanov, director of the public and political department at the Azerbaijani Presidential Administration, as saying that the construction in several parts of Baku as well as in the Bayil neighborhood was related to “ infrastructure, roads and other transportation projects, as well as the extension of [the] Baku Boulevard [an extensive promenade running along the seafront]” and “not related to Eurovision.” [42]

The road construction that runs through the neighborhood where evictions took place was planned before Azerbaijan won the Eurovision Song Contest in 2011, and residents in at least one building in the area learned that their building would eventually be demolished as early as February 2010 to make way for a park. However the pace of government actions to clear the land demonstrably quickened after Azerbaijan won the contest as the authorities accelerated efforts to complete the Baku Crystal Hall and related road infrastructure in time for the May 2012 contest. This is evidenced in the timing of one of the Baku City Executive Authority orders regulating evictions in the area (dated May 31, 2011), the rapid pace of evictions from September 2011- early 2012, as the government rushed to clear the area for construction of the extended coastal road, and statements by government officials linking construction in the area to preparations for the Eurovision Song Contest, as noted above.

II. Development, Expropriations, and Human Rights

The desire and policy of the Azerbaijan government to develop its capital and improve infrastructure and public works is a legitimate government mandate. Human rights law recognizes that rights to property, including house and home, may be subject to interference by the state in the interest of the common good, such as for purposes of development. However, such state interference with private property is lawful only if it takes place in accordance with a number of conditions: that the interference is in the public interest, that it is not arbitrary, that it follows due process and is conducted in accordance with appropriate legal provisions, and that it complies with principles of international law such as the provision of fair compensation.[43]

As a party to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Azerbaijan has clear and binding treaty obligations to respect the right to property, the home, and family and ensure access to a remedy in any process of expropriation.[44] The obligation is on the authorities to strike a ‘fair balance' between the demands of the public interest and the protection of the individual's fundamental rights.

Azerbaijan’s national law reflects these obligations. The constitution of Azerbaijan protects property from expropriation except by court decision and provides that property owners must be fairly compensated based on the value of the property. [45] There is also a law on expropriation of land for state needs that allows expropriation only when required by the state for a limited number of purposes. [46] The law also requires a decision of the Cabinet of Ministers,that notice of at least one year be given to tenants prior to expropriation, and that the state provide compensation at market value, among other costs. [47]

The Azerbaijan government therefore has options to lawfully expropriate such property that it can justify on development grounds, although for projects that are intended to be complete by May 2012, the legal process for expropriation would have had to commence significantly earlier than May 2011.

Human Rights Watch has documented human rights violations at every stage of the government’s “development” campaign, including in the process by which the authorities identified homes and properties for expropriation, notified homeowners and residents of impending expropriations and demolitions, and assessed and awarded compensation, as well as in the manner in which expropriations, evictions, and demolitions were executed. Irrespective of any lawful basis for the expropriations, the government’s conduct during the expropriation and evictions processes was abusive, and those whose rights were affected have had no effective legal recourse or access to a remedy.

III. Forced Evictions and Demolitions of Homes in Central Baku

Human Rights Watch interviewed 52 homeowners who faced abuses in the course of the government’s campaign of expropriations, evictions, and demolitions in central Baku.

While the experience of those homeowners in central Baku whom the authorities have forcibly evicted varied, it followed a basic pattern. Some of the homeowners learned that their homes would be expropriated when officials from the municipal housing authorities visited them and explained orally or through a written notice that their property would be demolished and that they should visit the resettlement commission established by the Baku City Executive Authority to discuss compensation. The written notices that Human Rights Watch saw were printed on blank paper with no letterhead, or, with some exceptions, stamps and signatures, and typically delivered to people by hand. Other property owners told Human Rights Watch that they received no official notification of impending expropriation or demolition but learned through rumors from neighbors or after seeing that neighboring or nearby properties were being demolished.

Once they had learned of the impending actions against their properties, homeowners could visit the resettlement commission, which consists of a representative of the Baku City Executive Authority and a representative of the State Committee on Property. The resettlement commission would present the government’s compensation offers. Typically, for apartments smaller than 60 square meters, homeowners were offered monetary compensation, based on a flat rate per square meter determined by the government. The authorities usually offered owners of homes larger than 60 square meters new apartments outside of the city center. But, they did not give homeowners immediate title to the new apartments—instead promising ownership titles at a later date—thereby potentially stripping them of their ownership rights. In some cases, the authorities called or visited residents to discuss compensation offers.

Some property owners accepted the government’s compensation offers, vacated their houses or apartments, and resettled in other homes—either those provided by the government or ones that they bought or, most typically, rented, using the compensation money awarded to them. In several cases documented by Human Rights Watch the government provided one month’s rent for temporary housing while evicted homeowners searched for a new permanent home.[48]Others remained in their homes because they refused the compensation offers or never received official compensation offers.

Some homeowners faced forced eviction immediately prior to the total demolition of their homes, with little or no warning. Their possessions were often forcibly removed, damaged, destroyed, or lost in the process. In other cases government representatives cut off water, electricity, and other services and began to partially demolish buildings in which residents continued to live. In two cases documented by Human Rights Watch, police detained homeowners and their families while government workers removed household goods and personal belongings and then demolished their homes.

Forced Evictions Immediately Prior to Demolitions

Irrespective of the legality of any expropriations, Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases in which the manner of forced evictions and demolitions was highly abusive, could never be justified as a proportionate measure, and violated the rights of the homeowners, families, and occupants.

Bayil Neighborhood

In December 2011, Human Rights Watch interviewed four families who had been forcibly evicted from their homes in the Bayil neighborhood next to the National Flag Square in September, October, and November 2011 in order for their homes and the buildings in which their apartments were located to be demolished. These residences, located at the base of a small peninsula, have been demolished to allow for the extension of a coastal road and creation of a park along one side of the National Flag Square. As noted above, the Azerbaijani authorities are working to complete construction of a large arena, the Baku Crystal Hall, on the opposite side of National Flag Square, in order to use it as the venue for the May 2012 Eurovision Song Contest. The planned new park in the Bayil neighborhood will thus presumably serve as an entry point to the new arena.

Arzu Adigezalova, 41, a math teacher and a single mother of two children, ages 9 and 6, lived in a two-room apartment at 3 Elchin and Vugar Gajibabaeva Street which the authorities demolished in October 2011. She had learned in June 2011 that the building would eventually be demolished and soon thereafter workers began dismantling the building. Adigezalova told Human Rights Watch:

I lived on the second floor. My neighbors above me had moved, and workers had already demolished their apartments. In early September 2011, the workers broke through my ceiling, and the chandelier fell. Then my balcony collapsed. The workers would throw heavy building materials down to the ground. It was dangerous. Once, a large stone almost fell on my child’s head. On September 9, I called the police and they came, and they took a statement from me, but nothing happened. On September 13, I called the Emergencies Ministry, but they did nothing.[49]

Adigezalova told Human Rights Watch that on October 11 she agreed to the government’s compensation offer, but was still looking for a place to live. She described how the authorities forcibly evicted her just over two weeks later:

On [October] 29, I woke up because the building was shaking, and I heard something I thought was thunder. I took the kids and went outside. [I went up to] the official in charge and asked him to give us time to take our belongings out. He looked at me and said, ‘Ok,’ but then in the next moment said to the bulldozer driver, ‘Knock it down!’

I had to leave behind mattresses, linens, tables, the gas stove. We weren’t expecting a bulldozer to come that day at all. That same official had promised us some money so that we could rent an apartment until I could find one to buy, but I got nothing.[50]

Another homeowner, Zarifa Aliyeva, a 47-year-old engineer, lived at 2 Khoshginabi Street with her two adult sons and her daughter-in-law until the authorities forcibly evicted the family on November 1, 2011. At 5:00 a.m. a bulldozer arrived to begin demolishing the building. Aliyeva described that morning to Human Rights Watch:

I was asleep, and a noise like thunder woke me up, so I woke up my kids. We ran outside and asked the officials overseeing the demolition to give us some time to gather up our belongings. The officials said ‘Ok, ok,’ but then immediately told the workers to get started with the demolition. I left half of my belongings there, including all of my dishes, a dining room table, and a cabinet.[51]

Although Aliyeva learned in June 2011 that the building would be destroyed, the authorities gave Aliyeva no warning whatsoever that the demolition would begin that day.

The authorities provided Aliyeva compensation for only 50 square meters of her apartment, rather than the total 103 square meters of actual living space (for more on unfair compensation payments, see below, Failure to Provide Alternative Accommodation or Adequate Compensation). “I am now forced to rent an apartment because I don’t have enough money to buy a new one,” she told Human Rights Watch. “And I can only afford to rent a one-room apartment, but there are four of us living there. My son has to sleep on the floor.”[52]

Neftchilar Avenue

On June 10, 2011, Sevinj Zainalova, her husband, and three children, ages 8, 18, and 20, were evicted from the home in which her husband grew up and which he had inherited from his parents at 61 Neftchilar Avenue. Zainalova, a homemaker, described the home as “a large apartment with a balcony and a garage, in the very city center, only a few minutes' walk from the presidential administration.”[53] A private development company, Klass AZ KO, notified the family nearly a year earlier that their home would be demolished and repeatedly called, offering the family compensation of 1,500 manat (US$1,900) per square meter or a smaller apartment outside the city center.[54] Zainalova and her family refused the compensation offer and remained in their home.[55]

On the day of the eviction, representatives of the police and the State Committee on Property and construction workers participated in forcing residents from their homes. Zainalova described the forced eviction to Human Rights Watch:

Ours was a long building, and they had been slowly destroying parts of it for months. But when they came on Friday [June 10] to evict us, we had no warning. My husband was at work. At least 15 police came, and several workers started to break down the door. They shouted at us to ‘Get out right away or we'll break down the door.' I demanded to see a court order, but of course they didn't have one. I started passing our belongings out of the window as the police broke down our door.

I called my husband, crying. When he arrived they wouldn't let him come into the apartment. His very own apartment! They grabbed him and tore his suit jacket. I didn't want this to go any further, so I gathered my children and we left. They demolished the building. Now we're living with my mother in a two-room apartment. I don't know where we will live.

They had told me, ‘Accept our compensation offer or you'll be in the street.' I really couldn't believe this. I couldn't believe that they could actually forcibly remove me from my own apartment. But that's exactly what they did.[56]

Prior to the forced eviction, Zainalova had learned that the Baku City Executive Authority had authorized Klass AZ KO to develop a shopping center on the land upon which the apartment building at 61 Neftchilar Avenue and other buildings were located.[57] However it is not clear if Baku City Executive Authority had any legal power to transfer use of this land. On the contrary, the Azerbaijani Housing Code provides that apartment owners also enjoy rights to the land on which their apartment is built.[58]

In April 2011, Zainalova’s husband, as the owner of the family’s property, together with other homeowners from this area, filed a lawsuit in the Sabail District Court against Azinko Holding because the Zainalovs believed it was Azinko workers they had seen performing construction work in the area, including the demolition of their home. The lawsuit sought pecuniary and non-pecuniary damages for violation of their property rights. Later, the plaintiffs added the Baku City Executive Authority, the State Committee on Property, and Klass AZ KO as co-defendants.

On December 8, 2011, the court found that Klass AZ KO had violated the property rights of the plaintiffs and found no legal basis for their eviction and the destruction of their property. The court awarded Zainalova’s family just over one-fourth of the damages requested in pecuniary damages and 1,000 manat (US$ 1,270) in non-pecuniary damages. The plaintiffs have appealed the decision, believing that the court award is substantially less than the value of their destroyed home and property and insufficient compensation for the family’s emotional suffering. [59]

The court did not rule that the Baku City Executive Authority had acted illegally under Azerbaijani law when it transferred use of the land to Klass AZ KO, nor that it, the police, or the State Committee on Property had committed an offense when they participated in the illegal eviction of Zainalova’s family and other residents.[60]

Neighborhood

behind Heydar Aliyev Hall

Topchubasov Street

Khajibaba Azimov, a former member of parliament and leader of the small United Azerbaijan National Unity Party, owned an apartment in a building on A. Topchubashov Street. After several verbal warnings that the building would be demolished, in December 2010 police forcibly evicted him and his family and destroyed their home despite a pending court case. Azimov had filed the suit in April 2010 and repeated subsequent appeals to court attempting to stop the demolition, including in the days immediately prior to the demolition. Azimov described the forced eviction:

Many times they came and told us to leave our apartment. There was a lot of pressure on us to leave. The last time was one week before the actual demolition. All of the buildings around us had already been demolished. Ours was the last to be demolished. In the evening the bulldozers came right to the house and even started to knock it down.

The police came, dragged us out of the apartment and made us stand on the street. Workers took out our belongings and threw them out on the street. We watched as the building was demolished. We didn't have the chance to immediately move our belongings to another location, and so some things remained outside on the street and many of our belongings went missing.[61]

Azimov appealed to the prosecutor’s office in January 2011 requesting an investigation into his missing personal property. He received no response.[62]

Shamsi Badalbeili Street

Ali A. is a retired lawyer who owned a home on Shamsi Badalbeili Street.He described to Human Rights Watch how in December 2010, with less than two days’ notice, police and other workers arrived at his home in to forcibly evict him, his wife, and children from their home of 15 years. Ali A. told Human Rights Watch:

I came out of my house in the morning and the police had surrounded it. The workers entered my apartment by force and started to take out my things. I paid them, hoping that they would be careful in taking out my things. They weren’t rude or offensive, but when they removed my belongings, a lot of my things were ruined, including my books, which were my most valuable possession. Tables, chairs, cabinets, a piano, antiques, all of which were very expensive, were all ruined. The workers took away the motors out of two air conditioners. They took things and just dropped them on the street.[63]

Office of the Institute for Peace and Democracy

On August 11, 2011 the municipal authorities, without warning, illegally demolished a building owned by Leyla Yunus, a prominent human rights defender in Azerbaijan, and her husband, Arif. The building, located at 38-1 and 2 Shamsi Badalbeili Street was home to three human rights organizations: the Yunus’ Institute for Peace and Democracy (of which Leyla Yunus is chair), the Azerbaijani Campaign to Ban Landmines, and the only women's crisis center in Baku. Although the building fell within a neighborhood identified in February 2011 by the Baku City Executive Authority for expropriation and demolition, in May 2011 the Yunuses had obtained an injunction from Administrative-Economic Court no. 1 prohibiting expropriation or demolition of the property pending a final court decision.[64]

An employee of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, Azad Isazadeh, told Human Rights Watch that he was in the building at around 8 p.m. when Yusuf Gambarov, an official from the State Committee on Property, and an official from the Baku City Executive Authority arrived. They indicated that heavy machinery would be destroying a neighboring building with which the building shared a wall, and encouraged Isazadeh to leave the premises for his safety. He refused. Several minutes later, without warning, heavy machinery broke part of the office building. Workers used iron bars to break the windows and also broke down the door. Government workers entered the building and began removing office furniture and equipment.

Isazadeh said that he asked the officials at the site to halt the demolition for a short period to allow time for him and local residents who had come to assist him to remove office equipment, documents, and personal belongings. The officials refused and ordered the demolition to go forward immediately. According to Isazadeh, “The police were there and it was all happening in front of their eyes and no one did anything.”[65]

Isazadeh and the others grabbed a few items that they could carry and left the building. By 10 p.m. the building was nearly completely destroyed. The vast majority of the furniture, office equipment, and archives for the three organizations was buried in the debris of the demolished building or removed by government workers. It is not known where the government workers took the property they removed from the building.[66] In a letter to Human Rights Watch, the Baku City Executive Authority claimed that “after repeated warnings” the authorities had moved all of the property in the building “safely and without damage, using specialized transportation,” but did not specify where the property was or how it would be returned to the Yunuses.[67]

Leyla Yunus believes that the timing and manner of the demolition—without warning, at night, without allowing for removal of the contents of the building, and in violation of a court injunction—amounted to retaliation for her human rights work, including her work on illegal expropriations, forced evictions, and house demolitions in Baku. Starting in 2010, Leyla Yunus filed numerous petitions to government agencies regarding other house expropriations and demolitions in Baku. In addition, on the morning of August 11, 2011, an article appeared in the New York Times describing the demolition campaign and extensively quoting Leyla Yunus.[68]

The Yunuses’ Appeals to the Authorities and Courts

Two weeks after the demolition, on August 25, 2011, the Yunuses received a letter from the Baku City Executive Authority indicating that on the basis of the general plan for the development of Baku, construction work had been begun in the city center (including in the area of the Yunuses’ home). The letter stated that the Yunuses had not responded to repeated offers by the authorities to sell their property.[69] The Yunuses maintain that they never received any compensation offers from the government.[70] The letter indicates that the Yunuses are entitled to receive compensation of 1,500 manat (US$1,900) per square meter through the sale of the property, which the Yunuses consider to be less than market value.[71]

On May 18, 2011, the Yunuses filed a claim with Baku Administrative-Economic Court no.1 against the Baku City Executive Authority, the Nasimi District Executive Authority, the Ministry of Finance and the State Committee on Property. Although prior to filing the lawsuit they had not received a formal notice of expropriation, they believed there was a real threat of state action against their property because they saw the expropriation and demolition of houses in their neighborhood and were aware of the Baku City Executive Authority’s order no. 76, which indicated that homes on Shamsi Badalbeili Street would be demolished.[72]

On May 24, 2011 the Baku Administrative-Economic Court no. 1 partially granted the Yunuses’ request for temporary protection and ordered the Baku City Executive Authority and the State Committee on Property to refrain from any demolition or construction that may damage or harm the Yunuses’ property. The Administrative-Economic Court hearing scheduled for June 14 was repeatedly postponed due to the government’s failure to appear or failure to submit documents requested by the court. The trial was ongoing at the time of writing.

On September 7, 2011, the Yunuses filed a complaint with the Prosecutor General’s Office identifying a number of criminal offenses that they believe occurred in connection with the demolition of their property on August 11, and requesting an investigation including into the role of the Baku City Executive Authority and the State Committee on Property in the demolition and the disregard for the court injunction.[73] In a letter dated September 8, the Prosecutor General’s Office stated that it had referred the complaint to the State Committee on Property for review. On September 30 the State Committee on Property informed the Yunuses that the authorities were resettling residents from the neighborhood behind the Heydar Aliyev Hall in order to construct a park. With respect to their complaint concerning the August 11, 2011 demolition, the letter merely recommended that the Yunuses contact the Resettlement Commission of the Baku City Executive Authority, which also has no investigative function, but is responsible solely for compensation to homeowners. [74]

The Prosecutor General’s Office is responsible for conducting a fair and impartial investigation into allegations of violations of the law by state agents. By referring the complaint and allegations of crimes to the State Committee on Property, which has no investigative function, and by taking no further action, the Prosecutor General’s Office is refusing to investigate alleged criminal acts by state agents. The transfer of the complaint to the State Committee on Property is utterly inappropriate. It is precisely this committee that the Yunuses’ allege, in their complaint, had violated the law, and whose representative, Yusuf Gambarov, supervised the demolition of Yunuses’ home on August 11. Leyla Yunus is not aware if the Prosecutor General’s Office has taken any other steps with respect to her complaint.[75]

The authorities’ disregard for the Yunuses’ complaints and refusal to investigate possible crimes is incompatible with the obligation to provide a remedy under international law. Article 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights requires the state to ensure an “effective remedy” for alleged violations of the convention, and in the case of violations that amount to criminal acts this should involve a prompt, impartial, and thorough investigation into the allegations which is capable to leading to the identification and punishment of those responsible.[76] The European Court of Human Rights has also made clear “effective” refers to the impact of the investigation in practice as well as in law, “in particular in the sense that its exercise must not be unjustifiably hindered by the acts or omissions of the authorities of the … State.”[77]

In October 2011, the Yunuses filed a complaint to the European Court of Human Rights.[78]

As a result of the demolition, the three organizations housed in the Yunuses’ property have struggled to continue working. Although the Women’s Crisis Center relocated at least temporarily to another building, Azad Isadzeh, who works as a psychologist for the Women’s Crisis Center, told Human Rights Watch in late September that the number of women seeking services at the center was reduced by 60 to 70 percent. “People just used to walk into the office and seek help, but now victims don’t know how to find us,” said Isadzeh.”[79]

The destruction of the Yunuses’ property also appears to have had a chilling effect on other homeowners in Baku who have sought to challenge the expropriations, unfair compensation, and impending demolitions through legal means. Fuad Agaev, a lawyer representing the Yunuses and dozens of homeowners told Human Rights Watch that following the demolition of the Yunuses’ property, homeowners are increasingly reluctant to pursue cases in the courts and feel that they have no choice but to accept the inadequate compensation offered to them, or risk losing both their home as well as the government’s monetary compensation.[80]

Illegal Detention as a Component of Forced Eviction

Human Rights Watch documented three cases in which police detained homeowners and their families in a police station while government workers demolished the apartment buildings in which they lived. Among those detained were children ranging in ages from 12 to 15. In all cases the detentions took place in the neighborhood behind the Heydar Aliyev Hall.

In all instances police detained homeowners and their families without explanation, did not allow them access to legal counsel, and released them without charge hours later, in one case as long as eight hours. These detentions, in the course of aggressive police action to forcibly remove people from their homes, exacerbated an already harrowing and distressing experience for residents. Furthermore, the government’s use of police to carry out the expropriation and facilitate the demolition implicates the police in the illegal actions of the Baku City Executive Authority and the State Committee on Property.[81]

49 Samed Vergun Street

Bashkhanum Abbasova, a retired university lecturer in applied arts, lived with her two adult sons, daughter-in-law, and grandson, in a large apartment building at 49 Samed Vergun Street. As described below, beginning in August 2011, the authorities had steadily dismantled the building while Abbasova and other residents continued to live in their apartments. On December 9, 2011, Abbasova agreed to the forced sale of her apartment, and on December 17, the authorities paid one month’s rent in an apartment in the neighborhood for Abbasova to use temporarily. Abbasova managed to move her furniture that same day, but continued packing and planned to complete her move in the next few days.

However, at around 9 p.m. on December 18, an excavator began breaking down the walls of the building at 49 Samed Vergun Street. According to Abbasova, the authorities claimed they needed to demolish the building urgently due to errors during previous demolition work, and it was at risk of immediate collapse. The evening quickly turned chaotic, as police confronted residents who were upset about the demolition. Abbasova told Human Rights Watch:

Residents started screaming and demanding that [the authorities] at least put up a sign that there was a demolition going on. … The authorities answered that it was a government matter and that we don’t have the right to interfere. The police started to chase people away and then hit people. … They hit my son and stuffed him in the police car. And they also pushed me into the police car.[82]

Abbasova’s adult son, Teymur, said that police punched and kicked him on his legs and stomach.[83] Police detained Teymur Abbasov and seven men who had come to help the family move. Abbasova said she insisted on going to the station with her son out of concern for his safety. Although Abbasova’s neighbors sent a lawyer to the police station, the police did allow him to enter or communicate with those detained. Police held Abbasova and the others until 4 a.m. the next day, and released them without charge.

Hearing noise from the demolition, one concerned neighbor, Reikhan Guseinova, a 47-year-old businesswoman, had come out on the street from her nearby home, as did her son, 14, and daughter, 26. She described how police also attacked them:

There were a lot of people on the street. I saw my neighbor who was going to be evicted, shouting [at the authorities]. My children and I all crossed the street, and [the police] started shouting, ‘Get out of here!’ Then they started pushing us. And they started to hit us.

When they started to push us, I was in shock. When they hit me, my children tried to protect me. And I tried to protect my children. I fell after being pushed, and my daughter fell on me. When my daughter fell, someone lifted her up, but then the police hit her. The second time they hit her she fell unconscious. People were yelling, ‘Get water! Call an ambulance!’ [84]

Gusseinova’s husband arrived and she and her family went home and sought medical attention. [85]

Later that night, when Abbasova returned to her apartment building after being released by police, she said that she could hardly believe her eyes. She told Human Rights Watch, “My home was no longer there. There was nothing.” Among the property she lost in the demolition were chandeliers, a gas stove, two televisions, two air conditioners, two fur coats, six carpets, one of which was a 200-hundred-year-old family heirloom, and family photo albums. “We lost our past,” Abbasova told Human Rights Watch.[86]

58 Fuzuli Street

On the morning of November 19, 2010, police and other officials surrounded an apartment building located at 58 Fuzuli Street in order to evict the eight families remaining in the building. Demolition on the building had begun in June 2010, and residents on the top (third) floor had already vacated their apartments, since the roof had been removed. Residents on the first and second floors, including Nuria Khalikova, a 46-year-old librarian, continued living in the building. Khalikova received no official, written notification that the building would be demolished and no information about potential dates of demolition.

Khalikova described to Human Rights Watch the forced eviction and illegal detention on November 19, 2010:

I went out in the morning to buy bread. When I came back I saw that police had surrounded the building, I ran back inside to my apartment. We had no warning that they would come that day. About 10 to 12 police broke down my door, and workmen entered the apartment and started moving out my furniture and belongings.

My blood pressure went up, and I started to feel very bad, so I called an ambulance. When the ambulance arrived the police wouldn't let it enter our courtyard. Instead, the police took me out of my apartment. They put me in a police car and took me to the local police station, no. 22. They had already brought my neighbors there. There were eight of us. Some people were still in their pajamas. They held us there all day, until about 7 p.m. They kept saying that they would let us go in half an hour, but they didn't.[87]

Although police did not explain to Khalikova the reasons for her detention, it is clear they detained her and the other residents to prevent them from interfering with the demolition of the building. Police attempted to force the residents to sign a statement saying that they had been detained for participating in an illegal demonstration, which the property owners and other residents refused to do.

Khalikova told Human Rights Watch what she and her neighbors discovered upon returning to their building:

When they finally let us go, we went back to our building, but they had already started to demolish it and we couldn't go in. We saw huge machines hauling away our belongings. I went to the warehouse to collect my belongings; half of the things were broken and many things were missing, including my diamond earrings that I wore every day. Many valuable things were just gone.[88]

24 Fuzuli Street

Perviz Emirov, 42, is a retired soldier who was wounded while serving in the military and receives a disability pension. He lived in a small one-room apartment at 24 Fuzuli Street with his wife and their three children: 12-year-old twin boys and a 15-year-old daughter. Emirov described to Human Rights Watch the police detention and the destruction of his family’s home and belongings in December 2010.[89]

About four or five police officers came at about 2 p.m. on December 22. We had locked ourselves in the apartment, but they broke down the door and began to detain us. I only had time to grab our documents and the little bit of money that I had at home, nothing else. They put me, my wife, and my daughter in the police car and took us to the police station. About 30 minutes later our twin boys came home from school and saw that the building was being demolished. Then the police brought them to the station as well. They let us go after about five hours and we walked home. When we got to our home, we couldn’t believe our eyes. Everything was destroyed. To this day I don’t know where our belongings are.[90]

Forced Eviction through Dismantling of Homes and Cutting of Services to Homes in Which Residents Continue to Live

In numerous cases, the authorities have begun dismantling buildings and have cut water, sewer, electricity, gas, and telephone lines while some homeowners, who have thus far refused to accept the government’s compensation or resettlement offers, remain in their homes. These actions show a serious disregard for residents’ health and safety and also appear to be an effort to forcibly evict the homeowners, by rendering the apartments uninhabitable.

Bayil Neighborhood

Residents of several buildings in the Bayil neighborhood next to the National Flag Square first learned in June 2011 that their homes would be expropriated and demolished. By September 2011, when Human Rights Watch researchers first visited the neighborhood, most of the buildings identified for expropriation and demolitions were already partly or completely destroyed, and by January 2012, all of the buildings except one, at 5 Agil Guliyev Street, had been demolished.[91] As this report went to press on February 20, 2012, the building at 5 Agil Guliyev Street was being dismantled and only a handful of families remained.[92]

In September 2011, Human Rights Watch interviewed five families who, at the time of the interview, were still living in buildings in the Bayil neighborhood next to the National Flag Square that the authorities were actively dismantling and demolishing. In December 2011, Human Rights Watch also interviewed a resident who had been forced to vacate her apartment due to the hazardous conditions.

In July 2011 neighbors told Viktor Karamanov, a retired military officer and his wife, Iveta, who are both in their sixties, about rumors that their building, at 3 Elchin and Vusal Khajibabaev Street, where they have lived for over 20 years, would be demolished. The six other families living on the third floor sold their apartments and left, while the Karmanovs stayed, hoping to negotiate the sale price of their apartment with the authorities. They repeatedly asked officials from the resettlement commission that they be allowed to remain in their apartment for some additional time. However, by late August, just a little over a month after the Karmanovs first learned of the government’s intention to demolish the building, the authorities had destroyed much of the building, including the roof. In late September the authorities cut the electricity and phone lines.[93]

“We did not want to sell our apartment,” Iveta explained. “But we have to sell now because it’s impossible to live here anymore. They broke down the roof so when it starts raining outside, it rains in our apartment too. … We begged them to at least leave the roof over our heads until we find someplace else to live, but they refused.”[94]

Violeta Latunova also lived at 3 Elchin and Vusal Khajibabaev Street with her husband, their 7-year-old daughter, and her mother-in-law. Latunova similarly told Human Rights Watch that she and her family had remained in the building, where they owned an apartment on the first floor, because her husband has not been able to obtain from the authorities one of the documents necessary to conclude the government’s sale agreement and receive compensation. At the time of the interview in September 2011, Latunova, who was pregnant, worried for her family’s safety and told Human Rights Watch that the day before the interview, a roofing slate just missed falling on her.[95]

In September 2011 Human Rights Watch also interviewed Elmira Ismailova who had lived her entire life in an apartment at 9 Agil Guliev Street. At that time Ismailova remained in her apartment despite serious risk to her safety because the government was actively dismantling her building. She told Human Rights Watch:

The authorities came in early June 2011 and told us that they would demolish our homes. Very soon after that, fifteen of my neighbors sold their apartments at the price the government offered. As soon as people sold, workers would come and start taking the apartments apart. They would take doors, windows, flooring, and any furniture remaining. There are only five families remaining now and almost everything except the walls is taken apart, including much of the roof.[96]

Ismailova said that she argued with the workers every day to prevent them from destroying the roof on the part of the building in which she and her husband remained. She described the situation as a “war” and refused to leave the building for fear workers would remove the roof or demolish the building in her absence. She told Human Rights Watch that she wanted to sell her apartment for the market value.[97]

Aysel A. lived with her husband and their two children in a recently-renovated apartment at 9 Agil Guliev Street in the Bayil neighborhood, immediately next to the National Flag Square. Aysel A. described how, beginning in September 2011, workers gradually rendered her apartment uninhabitable by removing the building’s roof, dismantling the flue that vented the heating system, and temporarily cutting off the water supply. “We were afraid to turn on the gas and the oven because the ventilation system had been ruined,” she told Human Rights Watch. “So we stopped using the gas. Then the people on the third floor had to leave because there was no roof. I left on October 18 because we just couldn’t stay any longer. I was afraid for my children’s health and safety. I’m 47 years old and I should be helping my children get on with their lives. But instead I’m starting everything over from scratch because they wrecked everything we’ve built for ourselves.”[98]

Azadlyg Avenue

Dilshad Shirinova is a 52-year-old music teacher who lived in an apartment owed by her sister, Emma, at 146-148 Azadlyg Avenue, in central Baku, across the street from the newly-built residence of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev.[99] In December 2010 Shirinova received notification that the building would be demolished, allegedly because it had been “condemned,” although officials provided no documentation supporting the hazardous condition of the building, which was built in the 1960s.

The Shirinovas were offered an apartment outside of the city center as compensation. However, after visiting the apartment and seeing its dilapidated condition (as described in more detail below), Dilshad refused to accept the compensation offer and remained in the apartment on Azadlyg Avenue.

Beginning in July 2011, while Dilshad Shirinova and a woman in another apartment remained in the building, workers started to take out the windows, doors, and floors of the neighboring vacant apartments and to dismantle the utility infrastructure of the building. Workers cut off electricity and destroyed a water pipe on a floor above the Shirinovas’ apartment, causing flooding in their apartment. Workers also began to demolish stairs and banisters, making the building unsafe, especially at night.

The gradual demolition and worsening of conditions forced Dilshad to relocate to another apartment and pay rent. Dilshad went to the police, who refused to help, and also wrote a letter to the prosecutor that went unanswered. The Shirinovas filed a complaint with the Baku Administrative-Economic Court no. 2, and in June 2011 received an injunction prohibiting further demolition of the apartment. The authorities appealed the decision, but it was upheld by the appeals court on August 26, 2011. In blatant violation of the injunction and on the same day as the appeals court ruling upholding the injunction, the authorities forcibly entered Shirinova’s apartment, removed her household goods and personal belongings, and then completely destroyed her apartment along with the rest of the building.[100]

Neighborhood behind the Heydar Aliyev Hall

Fuzuli Street

Homeowners of three properties on Fuzuli Street described to Human Rights Watch how in early February 2010, officials from the Baku City Executive Authority and local district officials informed them that the authorities were buying the entire block of freestanding houses and fenced off the area. Within about two weeks, without warning they cut the electricity, gas, water, and telephone lines to the homes. Property owners received no written documents regarding the expropriation and evictions.

Ismail and Shovket Bagvanov owned and lived in a single-family home at 44 Fuzuli Street.[101] Shortly after they cut off utility services to the building, the authorities removed the building’s doors. The Bagvanovs called the police, who never arrived. “After they cut the power, water, gas, and telephone we were forced to move out and live with our relatives as our home became uninhabitable,” Shovket Bagvanova explained. “But our furniture and belongings remained in the house.”[102]

In December 2010 the Bagvanovs received a notice that the authorities would grant them compensation at a rate of 1,500 manat (US$1,900) for a portion of their total square meterage (for more on problems related to compensation see below, Arbitrary and Inaccurate Measurement of Homes as the Basis for Compensation). One week later, the authorities demolished the house. “We watched as they demolished our house,” Shovkent Bagvanova told Human Rights Watch. “It was shocking. We had less than two hours to get our things out. Most of our possessions were buried in the house or taken away by the workers. In two days the entire house was leveled to the ground. The police were there and prevented anyone from interfering with the demolition.”[103]

The Bagvanovs filed a complaint with the Nasimi District Court in August 2010 asking that the authorities pay 5,000 manat (US$6,333) per square meter for their 255 square meter home, but lost the case and all of their subsequent appeals, through to the Constitutional Court.[104]

Malik Aliyev, 47, who owned a property at 40 Fuzuli Street that he used for both his home and his small business, a bakery, described a similar experience. In February 2010 officials from the Baku City Executive Authority told him to vacate the property, offering to buy it for 1,500 manat (US$1,900) per square meter. Aliyev refused. Soon thereafter, the authorities cut off all the services to his home and fenced off the entire block. Aliyev was forced to move with his wife and two school-age children to a rented apartment leaving much of their property in their home.