Summary

Increased fighting since late 2010 in southern Somalia between forces allied to the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) and the Islamist armed group al-Shabaab has resulted in more than 4,000 civilian casualties, including over 1,000 deaths, and numerous abuses against the civilian population. Tens of thousands of Somalis have been displaced from their homes, including over 87,000 who have crossed into Kenya in the first seven months of 2011 where they live in camps now officially sheltering almost 390,000 people. This upsurge in fighting, some of the most intense since 2006, took place against the backdrop of one of the worst droughts in recent years, compounding Somalia’s humanitarian crisis. In July the United Nations declared a famine in two districts of southern Somalia. Ongoing fighting, insecurity, and al-Shabaab’s prohibitions on humanitarian aid, including restrictions on aid agencies’ work and threats and attacks on humanitarian workers, have contributed to the present catastrophe.

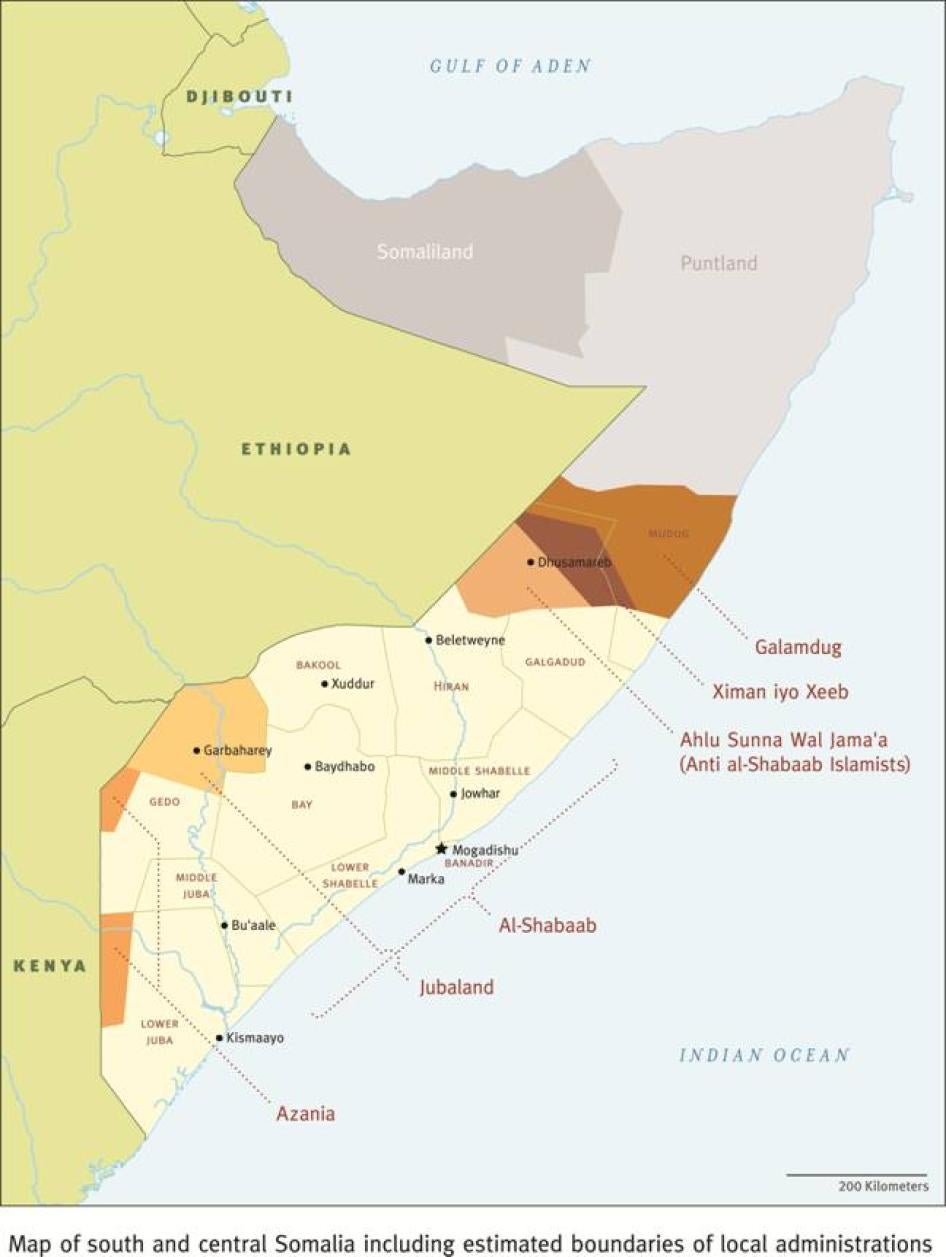

A TFG military offensive launched in February 2011, supported by the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), Kenyan and Ethiopian armed forces, and Somali militias, including those organized in Kenya and Ethiopia, has resulted in the capture of territory previously under al-Shabaab control in Mogadishu and in the south of the country near the borders with Ethiopia and Kenya. In particular, Kenya aims to make a strip of Somali land adjacent to its border, referred to as “Jubaland,” into a buffer zone between Kenya and al-Shabaab controlled areas.

Civilians have borne the brunt of the fighting between the many parties to the Somali conflict: the TFG, al-Shabaab, AMISOM, the Ethiopian-supported pro-TFG militias Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a and Ras Kamboni, and Kenyan-supported militias. There have been serious violations of international humanitarian law (the laws of war) by the parties to the conflict, including indiscriminate shelling of civilian areas and infrastructure, arbitrary arrests and detentions, and summary killings. The conflict has had an unquantifiable impact on the ability of civilians fleeing drought-affected areas to find assistance across the border in Ethiopia and Kenya either by blocking their way out or, in the case of al-Shabaab, the deliberate prevention of people from leaving.

Somalis fleeing from al-Shabaab-controlled areas reported widespread human rights abuses. Al-Shabaab continues to carry out public beheadings and floggings; forcibly recruits both adults and children into its forces; imposes onerous regulations on nearly every aspect of human behavior and social life, and deprives inhabitants under its rule of badly needed humanitarian assistance, including food and water.

The population in areas controlled by the Transitional Federal Government and its allies has also been subjected to violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. These include arbitrary arrest and detention, restrictions on free speech and assembly, and indiscriminate attacks harming civilians.

Somalis seeking safety in Kenya contend with police harassment, arbitrary arrests, and deportation back to Somalia. Somali refugees en route to the sprawling complex of refugee camps at Dadaab, Kenya, take hazardous back roads to avoid the Kenyan police and the official border post that until recently remained closed. They are then at the mercy of well-organized networks of bandits who engage in robbery and rape.

Human rights monitoring and reporting on Somalia by the international community remains inadequate, and yet ensuring systematic documentation of ongoing violations is key to ensuring eventual accountability for these violations. This report therefore highlights the range of ongoing human rights and international humanitarian law violations facing the civilian population in south and central Somalia.

The United Nations and major donors to the Transitional Federal Government, particularly the European Union and the United States, have condemned human rights abuses in Somalia and violations of international humanitarian law that caused civilian casualties. However, their military support for the TFG and AMISOM places greater responsibility on them to play an active role in improving the conduct of the TFG and its allied forces. Where these forces have taken over territory previously under the control of al-Shabaab, the UN and major donors will also need to press for respect for basic human rights and more closely monitor the support they provide. Support and policies that fail to achieve these basic objectives should be reconsidered. To date the TFG has been ineffectual in providing security and human rights protections in the limited areas under its control; broadening those areas is only likely to exacerbate existing problems.

In this report Human Rights Watch urges all parties to the conflict in Somalia to take concrete steps to protect civilians and prevent and punish those responsible for serious abuses. The TFG and AMISOM should adopt measures to reduce the likelihood of harm to civilians during attacks, especially by ending all attacks that do not discriminate between enemy forces and the civilian population. All the warring parties should facilitate rather than thwart humanitarian access and the humanitarian effort currently underway to deal with the drought.

Al-Shabaab should likewise take all feasible steps to avoid deploying in and launching attacks from densely populated areas. It should immediately cease using civilians as “shields,” that is deliberately placing civilians between its forces and those of an attacker. In areas under al-Shabaab control, local officials should respect the basic rights of the population, including the right to freedom of movement by permitting civilians to leave for other areas and countries. Such movement in light of the current drought is vital. Al-Shabaab should also immediately allow humanitarian aid agencies access to all areas under its control in order to provide urgent humanitarian assistance.

The United Nations (UN), United States, African Union (AU), and European Union (EU), which support the TFG financially and militarily, should set out clear benchmarks for improving respect for international human rights and humanitarian law and enhanced accountability. They should call on the TFG to urgently design and implement a strategy for improving security conditions and ensuring respect for human rights in areas under its control. With this in mind, they should encourage the TFG to ensure that the roadmap planned in the Kampala Accords includes clear human rights benchmarks. The TFG and its international supporters should further seek the establishment of a UN commission of inquiry by the UN Security Council to document serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law since the conflict began in 1991.

Kenya clearly faces huge challenges in assisting and protecting almost 700,000 refugees in Kenya. But these challenges do not excuse police abuses—including rape, arbitrary arrests, and unlawful deportation—against asylum seekers. Nor do they excuse the police’s failure to protect asylum seekers from bandits active in the border areas. Officers responsible for abuses should be promptly and thoroughly investigated. More generally, to help ensure that Somali asylum seekers can safely travel from the border to the camps and be registered for assistance as quickly as possible, the Kenyan authorities should reopen a screening center in Liboi on the Kenya-Somalia border and allow the United Nations and private bus companies to transport asylum seekers to the camps.

The drought in Somalia has sent the numbers of refugees crossing into Kenya and Ethiopia skyrocketing. But arrival figures were already very high in early 2011 due to the upsurge in fighting in Somalia, not least because of the Kenyan-supported efforts to push al-Shabaab out of Jubaland. Human Rights Watch is concerned by statements from Kenyan government ministers and officials encouraging the setting up of internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in Somalia, presumably in the buffer zone of Jubaland. Jubaland was until very recently an active conflict zone. It is a narrow strip: al-Shabaab positions are only 80 kilometers from the border of Kenya. Creating an artificial distinction between those fleeing conflict and those fleeing drought, as the Kenyan government has tried to do, is disingenuous. Famine always has complex political as well as environmental causes. Recent statements by Kenyan government officials raise concerns that Kenya may attempt to return some of the recently arrived refugees and possibly earlier arrivals to Somalia if new camps are established inside Somalia.

At present Kenya is the closest safe haven for Somali refugees and the international community’s plan to deal with the refugees should proceed on that basis. Kenya faces a considerable burden and claims that building more camps is unsustainable. However, at present there is little realistic alternative. With nearly 400,000 refugees crammed into space meant for 90,000 and with well over 1,000 refugees arriving in the camps every day as of late July, the authorities should immediately allow refugees to settle in the still empty Ifo II camp and sign an agreement with the UN refugee agency for additional land for new camps to help decongest the old ones.

Key Recommendations

To the UN Security Council

- Establish a commission of inquiry for Somalia to investigate and map serious crimes in violation of international law, and recommend measures to improve accountability for violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.

To the UN Political Office for Somalia (UNPOS) and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

- Increase the number of human rights officers monitoring and publicly reporting on human rights abuses in Somalia.

To the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia (TFG)

- Take all necessary steps to ensure that TFG security forces and allied armed groups comply with international humanitarian and human rights law.

- Ensure that all credible allegations of human rights and humanitarian law violations by TFG forces and allied armed groups are promptly, impartially, and transparently investigated, and that those responsible for serious abuses, regardless of rank, are held to account.

- Ensure that the roadmap to be developed as per the “Kampala Accord” includes clear human rights benchmarks.

- Allow an increase in the number of international agency staff monitoring and reporting on human rights abuses in Somalia, and lift the ban on officials from the OHCHR and on human rights officers within the UNPOS.

- Facilitate access to humanitarian aid in areas under TFG control.

To the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM)

- Ensure that all credible allegations of human rights and humanitarian law violations by AMISOM forces are promptly, impartially, and transparently investigated by AMISOM or force contributors, and that those responsible for serious abuses, regardless of rank, are held to account.

To All Armed Groups, including al-Shabaab

- Immediately take all necessary steps to end violations of international humanitarian law.

- Immediately allow humanitarian agencies, including the United Nations, access to areas under their control for the delivery of humanitarian assistance.

- Respect the rights of the civilian population to freedom of movement, especially the right to seek asylum in neighboring countries.

- Take all feasible precautions to protect civilians from the effects of attacks and otherwise minimize harm to the civilian population, including by avoiding deploying in densely populated areas. Cease the use of civilians as “human shields.”

- End all forced recruitment of adults and any recruitment of children under the age of 18.

To the United States, European Union, African Union, United Nations, and Other Donors

- Ensure that the roadmap for the transition to be developed in collaboration with the international community as stipulated in the “Kampala Accord” includes clear human rights benchmarks.

- Condition future financial and military support to the TFG on clear benchmarks for the respect of international humanitarian and human rights law and accountability for serious abuses.

To the Governments of Kenya and Ethiopia

- Ensure that any Kenyan and Ethiopian forces engaged in military operations within Somalia abide by international humanitarian law; law enforcement officials operating in Somalia should abide by international human rights law.

To the Government of Kenya

- Take all necessary measures to end police abuses in the border areas against Somali asylum seekers and refugees—including rape, extortion and arbitrary arrest and detention—and hold those responsible to account.

- End all refoulement—unlawful forced return—of Somali asylum seekers from Kenya and release those in detention on charges of “unlawful entry.”

- Immediately allow the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to transfer refugees into Ifo II camp.

- Urgently facilitate the granting of more land for 300,000 refugees in order to help decongest the existing camps and to respond to the ongoing influx.

- Publicly confirm that any camps or centers established in Jubaland are not a substitute for Kenya’s responsibility to host Somali refugees, and that Somalis have the right to seek asylum in Kenya both under Kenyan and international law regardless of administrative changes in Somalia.

Methodology

In April 2011 Human Rights Watch interviewed 26 recently arrived refugees and asylum seekers in the three refugee camps—Ifo, Dagahaley, and Hagadera—in Dadaab in northeastern Kenya, approximately 70 kilometers from the Somali border. Human Rights Watch also interviewed Kenyan police and officials of the Department of Refugee Affairs, officials of the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and representatives of Kenyan and international nongovernmental organizations and conducted follow-up interviews with the same during May and June. During the follow-up research, Human Rights Watch also interviewed representatives of the Transitional Federal Government and of Somali civil society organizations by telephone or in Nairobi or Kigali. This research additionally built on approximately 35 interviews conducted during November and December 2010 in Dadaab following the so-called “Ramadan offensive” in Mogadishu.

Refugees and asylum seekers identified as recent arrivals participated in voluntary, open-ended interviews. The primary purpose of the research was to identify violations of international humanitarian law and international human rights law by all parties to the conflict in Somalia. Refugees and asylum seekers were asked to describe the reasons why they had fled Somalia; the human rights situation in their area of provenance; and their experiences of armed conflict. They were also asked to report any difficulties they encountered en route from their areas of origin to Dadaab in order to assess the extent to which groups controlling territory in Somalia, as well as the Kenyan authorities, allowed for freedom of movement. Human Rights Watch was unable to conduct research within Somalia, due to security concerns, and within areas in southern Ethiopia, due to the Ethiopian government’s restrictions on human rights research; therefore, all primary research was conducted within Kenya. This report uses the testimonies of refugees and asylum seekers alongside secondary reporting on the conflict to describe the human rights and humanitarian context in which the current drought and famine is unfolding.

Interviews with refugees and asylum seekers were conducted in Somali with the assistance of interpreters. Most of the interviews were conducted on a one-on-one basis, while others were done in small groups. The names of all refugees and asylum seekers have been changed or omitted for security reasons.

I. Background

Somalia has remained in a civil war and without a functioning government since the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991. A conflict between clan-based militias struggling for political power came to an uneasy truce in 2006 with the rise to power of the militia-backed Islamic Courts Union (ICU).[1] But outside powers such as Ethiopia, the United States, and the European Union feared that the ICU and its radical armed youth wing, al-Shabaab, would create an Islamist bastion in Somalia.[2] The same year, Ethiopia militarily intervened in Somalia at the request of the ousted Transitional Federal Government, routed the ICU militias, and for two years fought al-Shabaab as it emerged as the main armed opposition group in the south and central parts of the country, especially in Mogadishu, the capital.

Ethiopia withdrew in 2009 as the Djibouti peace talks yielded a new administration, a revamped TFG. Almost immediately, the various armed groups, of which the TFG was but one, returned to open conflict. Throughout 2009 and 2010 fighting continued in Mogadishu and in isolated pockets while al-Shabaab consolidated its control over most of the capital and the country’s southern and central area. Al-Shabaab sought to impose its extreme version of Sharia (Islamic law) on areas under its control and committed widespread human rights abuses, including punishments such as beheadings, amputations, stoning and beatings, restrictions on dress and freedom of movement, enforced contributions, and forcible recruitment into the militia.[3] Al-Shabaab and other armed opposition groups regularly threaten journalists, civil society activists, and humanitarian workers. Al-Shabaab admits to the recruitment of children, who are represented among many recent deaths and defections in their forces.

The TFG has struggled to hold Somali territory since its inception, existing as a government in name only and in effective control of only a small portion of Mogadishu. Since 2009 the TFG has been supported by troops from the African Union Mission in Somalia.[4] Besides al-Shabaab, other significant armed groups are Hizbul Islam, Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a, and Ras Kamboni.[5] Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a, which receives military support from Ethiopia, and Ras Kamboni, are allied to the TFG. Hizbul Islam has on several occasions fought alongside al-Shabaab against the TFG and officially merged with al-Shabaab in December 2010. Both al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam have received military, financial, and political support from Eritrea.[6]

The Transitional Federal Government’s own record on human rights has been dismal. Its forces have been repeatedly implicated in indiscriminate attacks on civilians, arbitrary arrests, and repression of civil and political rights.[7] It has recently restricted the ability of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to monitor alleged abuses in areas under its control through the expulsion of two of its staff.[8] The TFG has also restricted the rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly.[9]

The TFG recently extended its mandate and the transitional period, which was to end in August 2011, for another year. The “Kampala Accord” signed on June 9, 2011 under the leadership of Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni—which bought an end to months of political wrangling between Somali President Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed and speaker of Parliament Sharif Hassan Sheikh Aden—postpones elections until August 2012 and grants the TFG an additional year to implement priority transitional tasks. These are the tasks deemed necessary preparations for the establishment of a democratic government. The Kampala Accord stipulates that a roadmap with clear benchmarks, timelines, and a compliance mechanism will be established before August 2011. The UN Security Council welcomed the agreement.

International donors, on whom the TFG is entirely dependent to function, have publicly stated that continued support would depend on completion over the next 12 months of priority transitional tasks as outlined in the Djibouti Peace Accord of 2008 and the Transitional Charter, but have not set clear benchmarks for improvements in human rights.

International donors provide significant political, military, and economic support to the TFG and AMISOM. In October 2010 the African Union appointed Ghanaian statesman Jerry Rawlings as Special Envoy to Somalia. In March the UN Security Council, at a conference chaired by China, concluded that the United Nations presence should be increased and better coordinated. The European Union pledged US$92 million in new funding for AMISOM, bringing the total EU contribution to $291 million; while the United States will reportedly provide an extra $45 million worth of military equipment to AMISOM troops.[10] Germany pledged an additional $4.9 million to AMISOM for equipment. The East African Community (EAC) has petitioned for more contributions from the European Union and United States.[11]

The AMISOM force strength remains at 9,000, far below the AU’s estimate of 20,000 troops needed to protect TFG institutions, an amount authorized by the UN Security Council. Burundi and Uganda have pledged 4,000 additional troops for AMISOM.[12] Uganda’s Defense Ministry is currently petitioning its country’s parliament for 4,000 more troops.[13] About 1,000 Burundian troops recently arrived in Somalia. Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Djibouti have also pledged a total of 4,000 additional troops. Despite the willingness of donor countries to contribute, funding and political will among donors continues to be an obstacle.[14]

The September 2010 and February 2011 Offensives

In September 2010 the TFG began a military offensive aimed at reclaiming more of Mogadishu from al-Shabaab. Both sides committed serious violations of the laws of war against the civilian population and there were no significant military gains.[15] In early 2011 the TFG renewed its offensive, this time with more coordinated support from AMISOM. Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a, and other militias trained by Kenya and Ethiopia and deployed in southern Somalia across the Kenyan and Ethiopian borders, joined the operation, which was aimed at retaking parts of the country back from al-Shabaab control.

Fighting took place across different parts of the country, notably in the Bay, Bakool, Hiran, and Gedo provinces, with serious clashes reported near the towns of Bula Hawo, Bulaweyne, Dolo, Dhobley, and Garbaharey.[16] Most of those areas are near the borders with Kenya and Ethiopia and the fighting was linked to the Kenyan government strategy of creating a strip or buffer zone inside Somalia to keep al-Shabaab at bay (see below).

TFG troops, backed by allied militias, were able to sustain some gains outside Mogadishu, although the frontline in the capital remains the site of ongoing clashes.[17] AMISOM now claims that pro-government forces control eight of sixteen districts in the capital, with 80 percent of the population under their control.[18] However, al-Shabaab recently reinforced its positions with up to 500 fighters from Lower Shabelle, Bay, and Bakool provinces.[19] A recent ongoing offensive to reclaim Mogadishu’s infamous Bakara Market, an al-Shabaab stronghold and source of revenue, could influence the broader situation, although at great cost to the civilian population.

The forces involved in the offensive against al-Shabaab are a mix of regular TFG troops and different allied militias. In the Gedo province, TFG forces together with Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a and other local militias, backed by Ethiopian armed forces, have taken control of large areas (see map) including the provincial capital, Garbaharey, meeting little resistance.[20] In Lower Juba, Kenyan-trained militias and TFG forces backed by Kenyan artillery have confronted al-Shabaab in fierce fighting around Dhobley and Bula Hawo.

The “Jubaland Initiative”

One of the main arenas of the current offensive was the border area of Kenya and Ethiopia, an area called “Jubaland.” Jubaland is the newest of the semi-autonomous regions throughout the country that have been formed due to the lack of central state authority—10 have been formed to date.[21] Also known as Azania, Jubaland is a proposed new semi-autonomous region comprising three regions on the Kenyan border, conceived principally by Kenya as a buffer zone against al-Shabaab and to potentially serve as a temporary home for the large number of people fleeing conflict elsewhere in the country.[22] At present it amounts to one relatively small parcel of land near Dolo on the Ethiopian border and a strip of land along the Kenyan border, approximately 60 to 80 kilometers wide, at the time of writing.

Human Rights Watch reported in 2009 on the recruitment of young ethnic Somalis of Kenyan and Somali citizenship in Dadaab camps and northern Kenya with false promises of high wages and UN backing for the force.[23] Over the intervening two years the militia has been languishing in Archer’s Post military camp near Isiolo in Kenya awaiting deployment. With the offensive from the north Kenya appears to have deployed that militia in support of the Jubaland idea and put the troops under the command of Prof. Mohammed Abdi Mohammed (Gandhi), a former TFG minister of defense.[24] Jubaland notionally comprises the present Somali provinces of Lower Juba, Middle Juba, and Gedo. Even after the recent offensives, however, in May 2011 only a very small part of Gedo and Lower Juba was under the control of Abdi and his Kenyan-trained militia.[25]

Kenya has for 20 years faced an increasingly heavy burden as refugees have fled conflict in Somalia, even as Kenya has itself contributed to that conflict by supporting the anti-al-Shabaab forces in the recent offensive to create “Jubaland.” Nonetheless, creating an area free of al-Shabaab controlled by friendly militias on the Somali side of the border allows Kenyan officials to make the argument that Somali refugees could stay there instead of coming into Kenya. And they have been arguing in recent months that recent arrivals are fleeing drought and not conflict and thus might not be considered asylum seekers under international law and who could then safely return to Jubaland, which the Kenyan government claims is safe.[26]

The Kenyan government accurately contends that the refugee camps at Dadaab are full, and have been for years, with new arrivals housed among the existing community or in temporary structures outside the camps. However, the people fleeing Somalia are a mixed caseload in that they are fleeing a complex humanitarian emergency in which conflict and human rights abuses play an intricate part in creating and complicating the need for and delivery of humanitarian assistance. They maintain their internationally protected right to seek asylum in a third country.

II. International Humanitarian Law Violations

All forces involved in the recent fighting in Mogadishu—al-Shabaab and Transitional Federal Government-aligned forces, including the African Union peacekeeping mission, AMISOM—have been responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law (the laws of war). These abuses include indiscriminate attacks, extrajudicial killings, arbitrary arrests and detention, and unlawful forced recruitment.

International humanitarian law imposes upon parties to an armed conflict the legal obligations to reduce unnecessary suffering and to protect civilians and other non-combatants. It is applicable to all situations of armed conflict, without regard to whether those fighting are regular armies or non-state armed groups, including al-Shabaab, Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a, and other irregular militias. All armed groups involved in a conflict must abide by international humanitarian law, and any individuals who violate humanitarian law with criminal intent can be prosecuted in domestic or international courts for war crimes. The same law applies to international forces such as AMISOM, which, according to its mandate, is not a party to the conflict but which nonetheless carries out military activity within Somalia.

The suffering of civilians as a result of the hostilities has been compounded by one of the worst droughts in recent history in Somalia, especially across southern parts of the country. Unnecessary restrictions on humanitarian access, theft of humanitarian aid, and, in the case of al-Shabaab, a blanket ban on all delivery of assistance, have heightened the suffering and swelled the numbers of people fleeing the area. Al-Shabaab has also prevented people from leaving for other places inside or outside Somalia.

Indiscriminate Attacks on Civilians

News from Mogadishu and information gathered by Human Rights Watch over the last year have reported regular clashes between AMISOM and TFG forces against al-Shabaab that nearly always result in civilian casualties. For example, in May, mortar rounds struck Bakara Market, the site of repeated shelling, reportedly killing 15 people and wounding 80 more.[27] One recent arrival from the capital, H.P., from Wardhiigley area, told Human Rights Watch that during recent fighting in Mogadishu, “There are several places where schools and health centers were destroyed by heavy weapons from both sides. It’s difficult to know if this is intentional. Both sides are using the public for shielding them.”[28]

Reliable figures are hard to come by in Somalia, but as of June 1, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), 3,900 injured civilians had been admitted to hospitals in Mogadishu since the beginning of 2011 as a result of the fighting.[29] In May, the fiercest month of fighting this year between AMISOM and al-Shabaab, almost half of the 1,590 admitted were children under the age of five.[30] With the fighting spreading to other parts of the country as a result of the TFG offensive, the abuses that have become the reality of daily life in Mogadishu are now being experienced by civilians in other regions.

The laws of war prohibit deliberate attacks on civilians as well as attacks that are indiscriminate or could be expected to cause disproportionate civilian loss. Only military objectives are subject to attack. The laws of war also require parties to a conflict to take all feasible precautions to protect civilians under their control against the effects of war. This includes avoiding locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas, and endeavoring to remove civilians from the vicinity of military objectives. When armed forces deliberately use civilians to render military forces immune from attack they are committing “human shielding,” a war crime.[31]

Al-Shabaab

Al-Shabaab has frequently conducted mortar attacks in Mogadishu in violation of the laws of war. As Human Rights Watch has reported previously, al-Shabaab forces deployed in densely populated neighborhoods will fire mortar shells indiscriminately towards TFG/AMISOM positions. No effort is generally made to remove the civilian population from the firing area; instead, after rounds are fired, the al-Shabaab fighters flee the area to avoid counter-battery fire from TFG and AMISOM forces, which often results in high civilian casualties. This tactic unnecessarily places civilians at risk and may amount to shielding. It may also be intended to generate popular resentment towards the TFG.[32]

A recent arrival from Mogadishu via Kismayo, O.L., told Human Rights Watch that al-Shabaab provided civilians no advance notice that they would be firing mortar shells from their neighborhood or permit them to flee to safer areas: “Al-Shabaab doesn’t let people go when an attack is coming, because they want to be with them and use them as a human shield.”[33]

AMISOM

As reported by Human Rights Watch in 2010 and 2011, civilians continue to report indiscriminate shelling by the AU Mission in Somalia.[34] Numerous cases of indiscriminate and, in some cases what appears to be disproportionate, AMISOM shelling were documented by Human Rights Watch from August to September 2010 during what was known as the “Ramadan offensive,” in which al-Shabaab conquered a significant amount of territory in Mogadishu, while the AU peacekeeping mission shelled al-Shabaab-controlled areas in an attempt to push back.[35]

In 2011, such cases appear to have diminished, indicating possible efforts on the part of AMISOM to improve its targeting and reduce indiscriminate fire, notably through the identification of no-fire zones.[36]

However, news reports continue to indicate a number of indiscriminate attacks, most notably on Mogadishu’s Bakara Market, an area of the town which remains heavily populated, and the center of civilian life.[37] In reference to the repeated shelling, a Benadir Administration (Mogadishu district) official morbidly called Bakara Market the “People’s Butcher.”[38] Similarly a March update from the International Crisis Group described AMISOM mortar rounds hitting camps for internally displaced persons, wounding dozens in February.[39]

AMISOM has admitted responsibility for a limited number of unlawful attacks on civilians. On November 23, 2010, troops opened fire on civilians at a busy intersection near Aden Adde airport. AMISOM acknowledged wrongdoing, apprehended six soldiers, and launched an inquiry. This represented the first instance of AMISOM admission of responsibility for civilian deaths.[40] In January AMISOM troops fired on a crowd rushing to aid a boy hit by a bus.[41] To date three AMISOM soldiers have been sentenced to two-year prison terms to be carried out in their home countries, in these cases Uganda. They were found guilty of “anti-civilian activities” in separate incidents.[42]

In a February 5 letter to Human Rights Watch, AMISOM force commander Maj. Gen. Nathan Mugisha acknowledged two incidents in which soldiers had, he said, erroneously fired on civilians, but he did not acknowledge AMISOM’s indiscriminate shelling of Bakara Market and other civilian sites in Mogadishu.[43]

While al-Shabaab’s practice of firing artillery from densely populated neighborhoods poses a difficult problem for AMISOM, such unlawful tactics do not release AMISOM from its obligation under the laws of war to ensure that attacks on military targets are not indiscriminate and do not cause disproportionate civilian casualties and loss of property.[44]

In May AMISOM announced that it had designated Bakara Market a “no-fire zone.”[45] Nonetheless, much damage had already been done, not least to AMISOM’s reputation. As C.E., from Hodan Village in Mogadishu, explained:

Both sides don’t spare the public. A lot of my neighbors were killed. Sometimes it happens that the person you had breakfast with in the morning is killed by mortars in the afternoon. This has happened to me. Sometimes you know who killed people, because the groups are located on different sides, firing mortars. AMISOM are the ones who are killing people a lot. But all of them are the same.

Al-Shabaab is fond of firing weapons from residential areas, knowing very clearly that the other side is going to return fire to the same place. Then al-Shabaab runs away. Al-Shabaab uses this as a propaganda war. They know it’s good for them when people blame the TFG. And the TFG and AMISOM don’t care whether there are civilians or not in the places they fire on.

You don’t know whom to blame—do you blame al-Shabaab for hiding among the public, or the government for hitting back at the same place from where they were fired on? [46]

Transitional Federal Government

Security forces of the Transitional Federal Government have been implicated in indiscriminate attacks causing civilian casualties and other laws of war violations. Other serious abuses, including the unnecessary use of lethal force, have occurred during situations that might more accurately be considered law enforcement operations, in which there is a higher threshold for the use of force.[47]

In late January TFG forces reportedly fired on civilians in Mogadishu killing from 12 to 20 people and wounding at least 30 others.[48] On February 15 in preparation for a renewed offensive, then-Prime Minister Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed (Farmajo) urged troops to avoid civilian killings.

Between February 15 and 21 there were four separate incidents in which TFG forces fired upon civilians. On February 15, TFG troops shot at civilians marching in protest against al-Shabaab, killing up to four and wounding between six and ten people. No reasons for the shootings were reported.[49] On February 17 a TFG soldier shot at a civilian bus that failed to stop when ordered, causing one death and two injuries.[50] On February 18, Shabelle Media Network reported that two civilians were killed and another two wounded after TFG soldiers opened fire on a food distribution line in Mogadishu.[51] On February 21, TFG soldiers fired on a crowd that had gathered at the Villa Somalia, the presidential palace, and was hurling stones to protest the arrest of former Mogadishu mayor Mohammed Omar Habeb; no deaths or injuries were reported.[52] These incidents prompted public statements of concern from AMISOM, TFG officials, and local elders.[53]

The TFG made several arrests in connection with these killings. In March the TFG Military Court tried five TFG soldiers on charges related to civilian killings; each was convicted and received prison terms of two to five years. Following the convictions the Military Court issued a stern warning against the killing of civilians.[54]

TFG forces continued to respond to al-Shabaab artillery fire from densely populated neighborhoods in Mogadishu with often indiscriminate counter-battery fire. Given the usual al-Shabaab practice of firing mortars and quickly vacating the area, the result of the TFG shelling is frequently just civilian casualties.

One woman from Tawfiiq in Mogadishu described the pattern of attack and counter-attack: “Al-Shabaab would hide among us during the fighting, and they were firing weapons from near our house. The government returned fire to the exact position they were attacked from but did not hit al-Shabaab, but they hit people’s houses. A lot of people were injured, others killed.” Her own house was destroyed by mortar shells; she did not know from which side.[55]

Such patterns of attacks appear to have occurred elsewhere as the fighting has moved beyond Mogadishu. T.S., who lost her husband and her eight-year-old son while fleeing from combat in Baardheere, Gedo province, said, “Many homes were destroyed by both sides. Nobody was bothering to try to avoid hitting civilians.”[56]

During heavy fighting in the town of Dhobley in March, TFG forces and al-Shabaab shelled civilian homes and infrastructure. According to D.I., “The two groups were using heavy weapons. The members of the public could not bear it, and fled, taking any route. Most of the houses were destroyed.”[57] A community hospital was severely damaged in the shelling, which appear to have involved Kenyan forces, as discussed below.

Ethiopian and Kenyan Armed Forces

Units of the Ethiopian and Kenyan armed forces have been deployed in support of operations in southern Somalia since the beginning of 2011. Both governments have provided military assistance to pro-government armed groups there, which could make them complicit in abuses committed by these groups.

Informants in Dadaab and others have reported the presence of Ethiopian and Kenyan soldiers, military advisers, and equipment in Somalia during this most recent phase of armed conflict.[58] Shabelle Media Network reported Ethiopian troops and advisers meeting with Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a in Balanbal in January.[59] Ethiopian forces deployed alongside Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a were reportedly shelling the town of Bula Hawo in March.[60] And in March TFG President Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed and Prime Minister Farmajo stated that Ethiopian forces had assisted in retaking Bula Hawo from al-Shabaab.[61] A Somali refugee in Dadaab and a Kenyan journalist also reported the presence of Kenyan troops and military equipment in Bula Hawo.[62]

Few abuses were directly attributed to these national armies in interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch. However, one refugee in Dadaab who fled from Bula Hawo in January 2011 said that Ethiopian forces were firing heavy weapons from near the border town of Dolo during the fighting in Bula Hawo. He told Human Rights Watch: “They were firing weapons from very far and not sparing anyone. Sometimes it lands on soldiers, sometimes it lands on houses, sometimes it lands on animals, sometimes on civilians.”[63] He said that no warning was given to civilians before the fighting started. Running from the artillery attacks coming from both sides, he became separated from his father and 12-year-old brother and has not seen them since. Another resident of Bula Hawo said that Kenyan forces were responsible for the destruction of the town: “What destroyed Bula Hawo were the weapons that the Kenyans were firing, using tanks.”[64]

In the border town of Dhobley a community hospital was seriously damaged by possible deliberate or indiscriminate shelling from Kenyan tanks and artillery. According to witnesses and hospital staff Kenyan tanks were located on the border and firing into Dhobley. In an email to Human Rights Watch, a hospital staff member explained that the shelling of Dhobley from the Kenyan side of the border started on March 6 and continued on March 16, 25, and 31:

A few weeks of continuous clashes between the al-Shabaab and the anti-al-Shabaab forces gradually increased in intensity with a major battle for the town on April 1. Heavy shelling of the town [120mm mortars] was followed by a coordinated offensive of the anti-al-Shabaab forces [Kenyan trained troops and Ras Kamboni group forces]. The Kenyan army was actively involved in the fighting [heavy artillery].[65]

On April 4 the Kenyan army shelled the town for the final time during the day and severely damaged the hospital. According to the same hospital staff member, “The hospital was not being used by the military forces of one side or another for military purposes at the time of the attack and any time before that day.”[66]

Unlawful Killings

Al-Shabaab has carried out extrajudicial killings of suspected informers or enemy sympathizers. In al-Shabaab-controlled areas, executions are imposed as a judicial punishment with little or no legal due process even for minor infractions of al-Shabaab’s strict interpretation of Sharia. TFG-aligned forces have committed extrajudicial killings of alleged al-Shabaab members.

Al-Shabaab

Al-Shabaab continues to carry out executions as punishment for alleged crimes, often with little or no legal process. In many cases, the executions take place in public.

In Afmadow district in early April al-Shabaab executed two mentally ill people whom the group suspected of being spies. According to O.L., an asylum seeker from the area, the two may have come under suspicion because they were among the only people who had not fled the town after al-Shabaab stopped allowing humanitarian agencies to provide food aid. O.L. told Human Rights Watch, “Everyone knows those two are mentally ill… [but] al-Shabaab thinks they are giving reports to people outside, and only pretending to be mad people… They were showered with bullets.”[67]

In Bula Hawo several people suspected by al-Shabaab of working with the TFG were executed.[68] One such case involved a man named Hassan Gase, who was executed in Bula Hawo in January on suspicion of working for the TFG.[69]

The public nature of many of the executions subjects the populace to an extraordinary level of violence. One woman from Jilb told Human Rights Watch, “I’ve witnessed this with my own eyes—people being beheaded, hands chopped off. They’re put on a chair and their heads are chopped off, in public. If they refuse to join jihad they are killed.”[70]

TFG-Aligned Militias

Human Rights Watch received several reports of extrajudicial killings of suspected al-Shabaab supporters by the Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a militia, which is allied to the TFG. According to witnesses after the TFG captured Bula Hawo town from al-Shabaab in March 2011, Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a, which controls the town, apprehended and executed three civilians.[71]

One of those executed was a 17-year-old boy who had been forcibly recruited by al-Shabaab and had left the force after his mother successfully pleaded with al-Shabaab for his release. According to a family friend, the boy was arrested while running home from school. She told Human Rights Watch:

When they arrested him, his father was informed. His father came to these officials and pleaded for his son to be released. He was told “We will also arrest you if you keep asking that question.”

They shot [the boy]. They emptied a whole cartridge into his body. They refused to allow the body to be collected. They kept it for three days and it decomposed before they buried it.[72]

A herder and another resident of Bula Hawo were also executed on suspicion of spying for al-Shabaab, according to one resident.[73]

Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a has defended the detentions and killings as security operations.[74] The militia’s spokesman, Sheikh Mohamed Hussein Al Qadi, told the media that it is the policy of the group to execute anyone accused of spying for al-Shabaab, including its own troops and children.[75]

Mistreatment in Custody

Human Rights Watch received reports of arbitrary arrest and mistreatment of civilians by al-Shabaab and TFG-aligned groups after taking control of areas from other armed groups.

Al-Shabaab

Al-Shabaab routinely mistreats persons in areas under its control.[76] A former al-Shabaab child soldier told Human Rights Watch about the arrests he recently helped carry out:

We worked in shifts, some at day, some at night. Some people were sent into town to arrest those who were drinking, smoking, chewing qat [a commonly used stimulant], and gossiping. I was among those who arrested people. They are blindfolded, their shirts are removed, and they are slashed with canes and kicked. A person is beaten until he becomes unconscious, then he’s taken to a cell.[77]

Torture and other ill-treatment previously documented appear to continue unabated. Al-Shabaab’s strict interpretation of Sharia is the basis for much mistreatment. Women are caned or arbitrarily detained for greeting men, including relatives, in public.[78] Al-Shabaab bans most recreational activities, including watching and playing football, and singing. Those who violate these prohibitions also risk beatings. One woman, who had made her living as a singer in Kismayo said, “It was suicidal to continue.”[79] Both women and men are subjected to conservative dress codes (such as covering of female heads and limbs, wearing black) and are punished if they do not comply; for instance, D.S., a man, was beaten for wearing trousers that were considered too long.[80]

TFG-Aligned Militias

In at least one area captured from al-Shabaab, TFG-aligned forces allegedly arbitrarily detained suspected members of al-Shabaab.

A.D., a woman who had fled from Bula Hawo to Kenya, returned to Bula Hawo after the fighting ended, and then fled once more, complaining of intimidation by TFG forces: “The officials from the TFG talked to us and said ‘Al-Shabaab has been causing lots of problems here. We called you back, but we want you to stay here peacefully. But if anyone tries to cause any problems, if anyone creates any insecurity, you will all be punished.’ Because of that we decided to leave.”[81]

Her husband, T.A., said his mistreatment by Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a drove him and his family from Bula Hawo, even after the town seemingly returned to peace. He explained:

I myself was arrested and robbed by [Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a] officials. I was sitting somewhere in the town center in Bula Hawo, and an explosion took place. A TFG government vehicle was destroyed by a mine. Immediately, the soldiers [from Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a] entered the town and started shooting carelessly. All of us were rounded up and taken to the police station. While I was being taken to the cell, the soldiers robbed my cell phone and 7,000 Kenyan shillings.

Five hundred of us were arrested. We were kept in a compound. Some were in a cell. Women were also arrested and were held separately. Some were carrying small children. The women and children were released the same day, but the men stayed in detention for two days.

After we were released, there was a public rally by the TFG government. They told us to do one of three things: either go to Kenya or Ethiopia, or go join those al-Shabaab people. [A district official] said, “If something happens again here, you will be held responsible and we will kill you.”

The day after the public rally we saw there was going to be no life there. We decided to take off.[82]

A.D. continued:

The TFG was also beating people. There were a lot of women who were put in the cell. They were arresting people and not even letting people take food to them. When I left, a lot of these people were still in the cell. I knew one lady among them... I don’t know if she’s been released. She was accused of being al-Shabaab because her brother was a member of al-Shabaab who was killed in the fighting. They were arresting people ages 15 and up whom they suspected of looking like al-Shabaab or dressing like al-Shabaab.[83]

This account aligns with what Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a spokesman Shariff Abduwahid told IRIN News in March:

We don’t want to kill brainwashed teenagers who were used by people who don’t favor the interest of the country and the Somalis; so those we have here we feel were misled; our intention is to keep them in prison, to orientate and clear their brainwashed minds.[84]

TFG

The Transitional Federal Government maintains a number of detention sites in Mogadishu where alleged al-Shabaab members and others are detained. Conditions in these detention facilities are dire and arbitrary detention is the norm. Access to the National Security Agency (NSA) detention facility is severely restricted; Human Rights Watch was unable to identify a single independent monitor that has recently had access to NSA facilities in order to assess the condition of detainees. Reports point to the presence of children in the NSA detention facility. Independent monitoring by the United Nations and civil society organizations is necessary in order to ensure human rights protections for detainees in TFG custody.

Recruitment of Child Soldiers and Forced Recruitment

During recent military operations, particularly the “Ramadan offensive,” reports of recruitment of children by al-Shabaab increased dramatically. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has condemned increased recruitment, as well as the alleged detention of child combatants by TFG forces, and called for an international body to have access to all detained children alleged to have participated in conflict.[85] Local nongovernmental organizations also alleged that several parties to the conflict have used child soldiers.[86]

International humanitarian law prohibits any recruitment of children under the age of 15 or their participation in hostilities by national armed forces and non-state armed groups. Somalia has signed, but has yet to ratify, the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict. The Optional Protocol prohibits any recruitment by non-state armed groups of children under the age of 18; any forced recruitment or conscription of children under 18 by government forces; and the participation of children under 18 in active hostilities by any party.[87]

Al-Shabaab

Al-Shabaab has been responsible for the widespread recruitment of boys and girls into its forces and the forced recruitment of adults, including older men. Human Rights Watch has previously reported on forced recruitment by al-Shabaab.[88]

O.L. told Human Rights Watch: “Al-Shabaab was forcibly recruiting. If someone has four boys, they are telling them they must donate three. They like to take children from 12 to 16 years, because they don’t know so much. One of my nephews was taken. He was 11-years-old. The last I heard he was in Baydhaba. I don’t know whether he’s dead or alive.”[89]

Forced recruitment of children also took place in Bula Hawo. According to K.F., “Teenagers were forced to either join them or leave the town.”[90] A 15-year-old from Bula Hawo also said children his age were recently being recruited.[91] In Jilb, J.K. told Human Rights Watch, “From the time al-Shabaab came, children stopped learning. Children of nine, ten, eleven years were recruited—some could not even carry a gun. All of the schools were closed.”[92]

All recruitment of underage children is a violation of international humanitarian law whether allegedly voluntary or not.

B.E. was taken to Elesha Biya, south of Mogadishu, and was trained in the use of several kinds of firearms.[93] He participated in combat on one occasion, shooting and killing one TFG fighter. He ran away after four of his friends, also children, were executed and dumped in the sea for attempting to escape. Despite the risk in attempting an escape himself, he said he could no longer bear the brutality of life within al-Shabaab.[94]

Al-Shabaab also forcibly conscripts adults. J.K. explained that “men loitering in the town” were often forcibly conscripted, causing many men to restrict their own movements and spend most of the time in their fields.[95] Older adults have been among those forcibly recruited. One 50-year old man who fled from Afmadow district said, “They tried to recruit me, but I ran away. They threatened me that if I don’t cooperate, I will be jailed for not following orders. They are not sparing even men of 50 years from recruitment.”[96]

TFG and Aligned Militias

Human Rights Watch documented recruitment under false pretenses by Kenya and the TFG during 2009 in its effort to put together the militia for the Jubaland initiative.[97] Some of those recruited under false pretenses may be among the militia deployed in Jubaland. Human Rights Watch has received credible secondary accounts that describe the presence of children among TFG and TFG-aligned militias.[98]

Restrictions on Access to Humanitarian Aid

The humanitarian situation across Somalia remains dire and has been exacerbated both by a spike in fighting from February to May and by extremely severe drought conditions. The effects of conflict and drought have pushed humanitarian and medical services beyond capacity. As of July 29, according to the UN, 2.2 million Somalis were in need of humanitarian assistance in al-Shabaab-controlled areas.[99] The UN also reported continuing prohibitions of people fleeing al-Shabaab controlled areas.[100] Many deaths associated with drought have been reported.[101] One in four children in Somalia is malnourished—one of the highest rates in the world—a situation exacerbated by the current drought.[102]

International humanitarian law requires that all parties to a conflict allow and facilitate the provision of humanitarian assistance to populations in need. Consent for the provision of assistance may not be withheld for arbitrary reasons.[103]

The delivery of humanitarian assistance to south-central Somalia has been partially blocked by insecurity as well as measures imposed by armed groups that specifically target foreign humanitarian agencies. Roadblocks, landmines, and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) inhibit the flow of food and medical supplies in a region with insufficient transportation infrastructure. Food prices have skyrocketed in some regions.

Al-Shabaab has violated international humanitarian law by prohibiting food aid to many areas under its control. It has banned about 20 humanitarian organizations, whom it accuses of pursuing religious or ideological motives.[104]

TFG troops have also been implicated in blocking the distribution of food aid. Ibrahim Nur Habeb, the chairman of the TFG’s Drought Commission, told Shabelle Media Network: “The soldiers stopped us from delivering aid food to about 600 families in Mogadishu.”[105] Theft and blockage of food has exacerbated food insecurity in an already tense, drought-affected, and increasingly resource-scarce environment. As a result some agencies had to cancel or suspend their operations. Organizations that continue to operate are either overwhelmed beyond capacity or hindered by continued violence or intentional disruptions.

Al-Shabaab

On July 6, al-Shabaab announced that it was lifting a longstanding ban on humanitarian food aid that had been imposed in areas under its control since 2009 following the flight of thousands of Somalis from al-Shabaab-controlled areas due to drought.[106] The move was welcomed by humanitarian organizations, but they called for al-Shabaab to provide guarantees for aid workers’ security.[107] Al-Shabaab subsequently backtracked, claiming that the proscribed aid agencies remained banned.[108]

The impact of al-Shabaab’s total prohibitions on food aid in areas under its control has been devastating for affected communities. Nearly all the asylum seekers who spoke to Human Rights Watch coming from al-Shabaab-controlled areas described a blanket prohibition on humanitarian aid.[109] The severe drought that has struck Somalia over the last six months had compounded the severity of this ban.

Refugees who arrived in Dadaab in April 2011 from the al-Shabaab-controlled district of Sakoh appeared to be severely malnourished. One refugee from Sakoh district lamented, “I think they wanted the people to die.”[110] A woman risked fleeing when she was nine-months pregnant, giving birth in the bush along the way, rather than staying in Sakoh.[111] Elders in Luq, Gedo province, reportedly called on al-Shabaab to lift its blockage of assistance, warning that people would die of starvation without food aid.[112] Those warnings have come to pass.

T.F., from Bay province, said he fled to Kenya after a year under al-Shabaab. He told Human Rights Watch: “[Al-Shabaab] has stopped agencies from bringing food and water to people, so it’s causing a lot of hunger, and people are just running away. This has been going on for almost a year. They were telling people to just depend on God and forget about depending on the agencies.” He left Somalia after nearly all of his 40 goats and 20 cattle had died of starvation, leaving him with no options but to depend on the aid that had ceased to arrive.[113]

D.S. of Afmadow district said, “No humanitarian aid is accepted by those guys. They say, ‘These are infidels who are distributing food, and we don’t want anything from them’”[114]

A.P., interviewed by Human Rights Watch on the day he arrived from Sakoh, said, “All our animals died. There are no camels anymore, no goats, no cattle, and even people started dying. There was no food because al-Shabaab would not allow the aid agencies to bring food. They say, ‘We don’t want the food of disbelievers.’”[115]

Al-Shabaab Attempts to Halt Emigration

International law protects the right to freedom of movement, including the right to leave one’s country.[116] Civilians during wartime are similarly protected against arbitrary restraints on their liberty.[117] Any prohibitions on movement imposed by a party to the conflict should be short-term measures for specified reasons to protect civilians from the effects of attack.[118]

Recently arrived asylum seekers in Kenya told Human Rights Watch that al-Shabaab attempted to prevent some Somalis from fleeing the country, including by blocking roads primarily around Dhobley, stopping buses, arresting and detaining some individuals—although generally temporarily.[119] In July the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) was still reporting al-Shabaab prohibitions on people leaving areas under their control.[120]

K.F., 20, told Human Rights Watch that he was in a group that fled from Bula Hawo to Dhobley and then to Kenya in April 2011:

On the way we were arrested several times by al-Shabaab and they were refusing that we cross into Kenya. They told us ‘As teenagers you cannot leave the country. Who is going to defend the country?’ We pretended we were going back to Bula Hawo, and then took panya [back] routes.[121]

According to J.K., “Al-Shabaab was preventing people from leaving, so we came through hiding. Any vehicle that they see carrying people, they’ll arrest.”[122]

Some who attempted to flee did not make it past al-Shabaab forces. U.W. fled Dinsor for Bula Hawo in September 2010 because of drought and al-Shabaab demands for money. He then crossed into Kenya when fighting started in Bula Hawo in January. According to U.W., “I asked my family to come from Dinsor but they were returned to Dinsor by al-Shabaab on the way. They were told ‘We know you’re going to Kenya,’ and were forcibly returned. They were forced to return home by al-Shabaab three times. They have not arrived [in Kenya] up to now.”[123]

Apparently, to frighten those who had fled its areas into returning, al-Shabaab threatened to attack Kenya if asylum seekers who had fled from Bula Hawo to Mandera in Kenya remained abroad. The group posted tracts throughout Mandera advertising this threat. Several asylum seekers returned to Somalia out of fear of an attack on Mandera.[124]

III. Other Rights Abuses

Criminal Offenses by TFG Soldiers

Several interviewees reported that Transitional Federal Government soldiers committed robberies and other common crimes against the population. Such offenses were not necessarily sanctioned by TFG leadership, but the TFG failed to prevent such activity or take adequate measures to discipline its troops in spite of repeated reports about abuses by its soldiers.

A young man who fled Mogadishu in April told Human Rights Watch he knew of TFG troops stealing cellphones from civilians.[125] One woman accused some TFG soldiers of theft: “Last October they looted my house, and took my gold and other things. They came in uniform. About five came, with rifles. We lost everything.”[126]

T.S., from Baardheere, said that her town had changed hands between al-Shabaab and the TFG several times in the last year. She said, “Whoever is in control of the town beats people and loots properties.”[127]

Taxation and Confiscation of Livestock by al-Shabaab

Al-Shabaab has set up predatory “taxing” structures in the areas that it controls. Claiming to act on the basis of the Quran, the group demands zakah—a Muslim religious duty to purify the soul through giving alms—from families. Many asylum seekers told Human Rights Watch that in the name of zakah, al-Shabaab confiscated so much money and livestock that they were no longer able to survive.[128] As D.S., an asylum seeker from Afmadow, put it: “If you have goats, they take your goats. Whenever the corn is ready, they come.”[129]

The economic burden on families is rendered more difficult by al-Shabaab’s prohibition on work by women. The ban, which al-Shabaab claims is based in the Quran, is in some areas little more than another form of extortion. One female market vendor who had recently arrived in Kenya from Jilb in Middle Juba province told Human Rights Watch, “They were preventing us from working as women. If you wanted to work, you had to bribe them.”[130]

In at least one location in Sakoh, men were stopped from working as well. According to two young men from Sakoh, they were forced to spend a large segment of the workday in courses that one of them described as teaching “how to go and fight the holy war.” His friend added, “You are told not even to work, because God provides, yours is to learn, food will come with the grace of God.”[131]

Persecution of Political Opponents by al-Shabaab

Those who expressly support political groups other than al-Shabaab do so at grave risk. One recently arrived asylum seeker from Lower Juba province, O.L., told Human Rights Watch that he had been a local official for Hizbul Islam, a competing Islamist militant group that signed a peace agreement with al-Shabaab in December 2010 and merged with it. In early 2010, prior to the agreement, al-Shabaab burned down all of his properties, and he fled into hiding. Even after the reconciliation al-Shabaab continued seeking O.L. He said his brother was tortured in an attempt to force him to reveal his whereabouts. O.L. subsequently fled to Kenya.[132]

A woman from Mogadishu said that her husband, an active TFG supporter, was abducted by al-Shabaab in Bakara Market in August 2010:

They called me themselves and said, “We are in possession of your husband, who is also an infidel, isn’t he?” I said “My husband is a Muslim.” They said “He is an infidel and we will slaughter him.” Two days after he was arrested they called me again. They told me we were infidels, our children were infidels, and to beware.… Their threats are still ringing in my ears.

She fled to Kenya in March, with no idea whether her husband was dead or alive.[133]

Attacks on Journalists and Human Rights Defenders

Somalia remains one of Africa’s most dangerous countries to be a journalist. Since 2005, 23 journalists have been killed. In November 2010 journalist Hassan Mohamed Abikar narrowly escaped an assassination attempt. Fifty-nine Somali journalists are in exile, the world’s second largest source of exiled journalists. At least 16 journalists fled in 2010 alone.[134] Both TFG and opposition forces have harassed the dwindling number of journalists still struggling to operate in Somalia. Some journalists who fled the country still receive threats.[135] Journalists who remain are subjected to arbitrary arrest and harassment.

In March TFG security forces summoned Abdi Mohamed Ismail, the editor of Shabelle Media Network, one of the few Somali media sources with international reach, and detained him for three days. Ismail was interrogated about the accuracy of his network’s reporting, and a particular news item that the TFG deemed critical of President Ahmed. Concern among local elders, the National Union of Somali Journalists (NUSOJ), and members of the Transitional Federal Parliament hastened his release. The TFG Ministry of Information has used false allegations to prompt the attorney general to interfere with meetings of the NUSOJ, and to attempt the arrest of the organizations’ leaders. In May, unknown gunmen stormed the offices of NUSOJ, stealing computers and documents, and threatening NUSOJ staff.[136]

The majority of human rights defenders fled the country in past years amid increasing threats. The TFG has banned two UN human rights officials: Scott Campbell, director of Africa field operations of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and Sandra Beidas of the UN Political Office for Somalia.[137]

IV. Abuse of Refugees and Displaced Persons

As of January 2011 there were 375,000 internally displaced persons in and around Mogadishu, and 1.4 million nationwide.[138] This population has swelled in recent months. Between mid-May 2011 and mid-July, 100,000 new IDPs, displaced as a result of the drought, arrived in and around Mogadishu, 70,000 of whom arrived in July alone.[139]

As the drought persisted in certain regions of south and central Somalia, 20,000 Somali refugees arrived in Kenya within the space of two weeks in June.[140] On July 20, the UN declared famine conditions in South Bakool and Lower Shabelle provinces.

By mid-July the total number of registered Somali refugees and asylum seekers in the countries bordering Somalia had reached 811,176,[141] though hundreds of thousands more who wish to avoid the appalling living conditions in the Dadaab refugee camps are known to live in Kenya’s major cities such as Nairobi and Mombasa.[142] Over half of registered Somali refugees in the region are in Kenya, which has repeatedly and unlawfully deported dozens, and at times hundreds, of Somalis back to their war-torn country.[143]

Ethiopia has also experienced an influx of Somali refugees. Between January and mid-July almost 78,000 Somalis crossed into Ethiopia, bringing the total number in Ethiopia to over 159,000.[144] A significant proportion of the recent arrivals have sought refuge in the country’s eastern Somali region, with the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees setting up a fourth camp in the Dollo Ado region to respond to the influx.[145]

Continued Arrests, Deportations, and Extortion by Kenyan Police Officers

Human Rights Watch has reported extensively on police and other abuses Somali asylum seekers face as they try to reach Kenya’s refugee camps as well as abuses and other violations they face in the camps and in the town of Garissa.[146] Following meetings between Human Rights Watch and the Kenyan government in 2010, the government set up an independent team to investigate. The team visited the camps in September 2010 but the government has still not published its findings. The abuses described below all took place since the fact-finding team was set up.

Kenyan police continue to arrest, deport and occasionally extort money from Somali asylum seekers, in violation of Kenya’s Refugee Act of 2006.

The flight of thousands of Somalis from Bula Hawo to the northeastern Kenyan town of Mandera in March 2011 is a case in point. The local community in Mandera initially welcomed the Somalis, who were fleeing fighting between al-Shabaab and the Transitional Federal Government. The refugees were initially housed in a sports stadium, and then moved to a temporary refugee camp managed by the Kenya Red Cross. However, after several days, the district commissioner ordered the police to forcibly return them to Somalia.[147]

N.Y. was among those who were forcibly returned to Bula Hawo, and who then re-entered Kenya further south to reach the Dadaab camps. She described her ordeal to Human Rights Watch:

When the fighting started again, in March, we had to flee. In Mandera, I stayed with relatives for some days… [then] I went to the camp in Mandera and I stayed there for five days. Then the Kenyan government officials, with askaris [soldiers], came and told us to leave. These people were armed and in uniform. There were two trucks full of askaris. A lot of refugees were beaten by the Kenyan askaris in the process of leaving the camp.

We were told to go back to our country because it is peaceful now. They were threatening us, telling us “If you don’t move, all of you will be put to the ground. We will flatten you and walk on you.” They were just standing on the vehicle and shouting this—they did not have a megaphone. They were driving around from place to place and informing people. It was daytime, around 10 a.m. By noon, everyone left.[148]

While in November 2010 UNHCR had publicly called on the Kenyan authorities to halt the refoulement of Somali refugees from Mandera.[149] Both the Kenyan government and UNHCR have denied that refoulement took place at Mandera in March 2011, suggesting the return to Bula Hawo was voluntary and that those who wished to do so were permitted to stay in Kenya.[150] According to K.F., “After the TFG captured Bula Hawo, the camps were closed and we were told ‘Your government is now in control of Bula Hawo. Go back to your country.’”[151]

Other refugees, who stayed in Mandera with families or friends rather than moving to the camps also faced police abuse. K.F. told Human Rights Watch:

The Kenyan police would ask us for ID and said that if you don’t have it, you have to pay a bribe or you are put in a cell. I was arrested, but I called people and I was released before I was taken to the main police station. The people brought about 5,000 Kenyan shillings—US$55 [to pay the policeman who arrested me]. This happened to everyone who doesn’t have an ID card—it’s a business that is very common with the Kenyan police.[152]

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly reported on how the January 2007 border and Liboi refugee reception center closure has directly encouraged Kenyan police to intercept, extort money from, arrest, detain, and deport large numbers of Somali asylum seekers trying to reach the Dadaab camps 90 kilometers from the Kenya-Somalia border.[153] According to the Refugee Consortium of Kenya (RCK), a Kenyan refugee rights organization, the police deported over 100 Somalis during a two-week period in April 2011[154] and sometimes carried out deportations at night.[155]

According to Human Rights Watch’s previous research and recent interviews with the RCK, which continues to monitor the courts in the town of Garissa near the camps, when asylum seekers are taken to court on charges of unlawful entry or presence in Kenya, the magistrates only sometimes protect their right to seek asylum and order them to be released and taken to the camps, though they have been detained for days in often overcrowded Kenyan police cells.[156]

The RCK trains both police and courts on asylum seeker and refugee rights under refugee law. But they say they only get mixed results, in part because of pressure on local police officers by Nairobi-based police officials to arrest and detain asylum seekers. One RCK lawyer involved in training the police told Human Rights Watch:

In the evaluation forms at the end of trainings, the police say “We want you people to target our bosses,” because they know refugees have rights but they are getting orders from higher up. They are evaluated on the number of arrests they make—the police told me this. The [administration police] say, “Our work is to arrest; it’s the work of the courts to release people.”[157]

Kenya’s Refugee Act provides that asylum seekers have 30 days from the moment they enter the country to register as refugees with the authorities at the nearest office of the Kenyan Refugee Commissioner.[158] They may not be refused entry into or expelled from Kenya if such refusal or expulsion would return them to a country in which “the person’s life, physical integrity or liberty would be threatened on account of… events seriously disturbing public order in part or the whole of that country.”[159] International and African regional law prohibit the forcible return of refugees and asylum seekers to persecution, torture, and situations of generalized violence that seriously disturb public order.

UNHCR has advised governments not to return Somali civilians to south-central Somalia because of the “risk of serious harm that civilians may face there due to widespread violations of the laws of war and large-scale human rights violations. Although the Kenyan government may lawfully prevent those reasonably regarded as a threat to its national security from entering Kenya, it may not close its borders to asylum seekers and is obligated under the 1951 Refugee Convention to screen them for refugee status before determining whether to return them.[160]

Exposure to Criminality and Rape B etween the Border and the Dadaab Camps

Somali asylum seekers’ fear of arrest and deportation continue to force them to use smugglers to drive them from the border to the refugee camps along small bush roads where they are frequently targeted by police and bandits.[161]

Despite reports that several hundred asylum seekers had been deported from Kenya in recent months, UNHCR told Human Rights Watch that this figure should be assessed in light of the 10,000 other refugees who were allowed into Kenya each month and made their way to the camps.[162]

Of the 26 recently arrived Somali refugees and asylum seekers interviewed by Human Rights Watch at Dadaab in April 2011, 10 had been targeted by criminals between the border and the camps. All of them said that to avoid the Kenyan police, notorious in Somalia for arresting, detaining, or deporting Somalis as they arrive in Kenya, they paid smugglers to help them stay clear of the main road to the camps and instead took the more dangerous “panya [back] routes,” which are known to be targeted by bandits. The robberies took place in daylight as well as at night, raising questions about the ability and willingness of the Kenyan police to patrol the area and prevent such crimes.[163]

The interviewees said that the criminals beat and robbed them of their few belongings. There were many reports of women being raped.

Bandits twice stopped the vehicle in which D.I. travelled from Dhobley to the camps in March 2011. She told Human Rights Watch:

Three days ago I left Dhobley. We were in two matatus [public service minivans]. We were robbed on the way. There were armed people on both sides of the road. They started shooting at us. They told us to lie down on the ground. There were about 40 of us, and there were 10 men who came with their rifles and put them on our necks, and another 10 in the bush.

Men and women were separated and we were told to give them mobile phones, money, whatever we had. Some of the girls were raped—about six of them. For me, they just put a gun to my neck and took my money and mobile phone, but I am an old person so I was not subjected to rape.

They released us and we started driving our vehicle. After a few kilometers we were trapped by criminals again. The vehicle got stuck and we could not move it. We had to come by foot. The second group of criminals also raped people. We were hearing the girls crying. The criminals were carrying knives and saying “If you don’t come, we will kill you.”[164]

After the second attack, D.I. walked for 48 hours to reach Dadaab.

Criminals also stopped K.F., who traveled to Kenya in mid-April. He was robbed and beaten, and, like D.I., was forced to walk to Dadaab on foot, adding, “There were some women with us and they took them to the bush, and the women said later that they were raped by the criminals.”[165]

In another incident in February D.S.’s vehicle was stopped in broad daylight by six or seven men with guns. He said that three women were taken into the bush and raped.[166] He explained, “We took the bush route because if the cars go straight [on the road from Dhobley to Liboi] they are stopped by the police and arrested. The people will have to stay at the police station without enough food and water.”[167]

Victims expressed doubt that the Kenyan police would act if they reported the attacks. A.M. said “I don’t want to report it because I don’t think the Kenyan police will do anything.”[168] This sentiment was echoed by every victim of criminal attacks interviewed by Human Rights Watch.