“Even Dead Bodies Must Work”

Health, Hard Labor, and Abuse in Ugandan Prisons

Map: Prisons Visited by Human Rights Watch in Uganda

Definitions and Acronyms

ART or ARVs: Antiretroviral therapy for the treatment of HIV, which works to suppress the HIV virus and stop the progression of the HIV disease

CD4 count: The number of CD4 cells (T-helper lymphocytes with CD4 cell surface marker) used to assess immune status, susceptibility to opportunistic infections, and a patient’s need for antiretroviral therapy

Committals or committed prisoners: Prisoners facing serious criminal charges, such as murder or aggravated robbery, whose cases have been sent to the High Court but who have not yet completed their trials

Farm prison: Prison where prisoners work on government-owned fields to produce mainly maize meal and beans consumed by prisoners countrywide, in addition to other labor

Garden: Field where prisoners work, also referred to as a shamba

JLOS: Justice Law and Order Sector, a group of Ugandan government bodies and international donors working collaboratively to improve access to justice

Katikkiro: Prisoner with disciplinary authority, sometimes called RP (short for “Resource Protection”) or ward leader; Luganda word literally meaning “administrative head”

LAP: Local administration prison; until 2006, local governments in Uganda administered over 170 prisons independent of the Uganda Prisons Service; former LAPs are smaller and historically less resourced than the larger prisons which have been continuously under central government administration

MDR-TB: Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis, a form of tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistant in vitro to the effects of isoniazid and rifampicin, the two most powerful anti-TB drugs, with or without resistance to any other drugs

Murchison Bay Prison Hospital: The only prison referral hospital in Uganda administering care to prisoners, based at the Luzira/Murchison Bay Prison complex in Kampala

OC: “Officer in charge,” in this case, of a prison; he or she is the highest ranking officer present at the facility and has near-total discretion in decisions concerning his or her prison

Panadol: Paracetamol, a basic pain reliever also marketed as Tylenol

PMTCT: Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV; PMTCT health interventions aim to reduce the spread of HIV from a mother to her baby during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding

Reception center: Prison intended to hold remanded, newly convicted, short-term, or maximum security prisoners who have not been sent to farm prisons

Remands or remanded prisoners: Prisoners awaiting trial or currently on trial

Septrin: Cotrimoxazole, a medication recommended for all individuals testing positive for HIV in order to treat opportunistic infections

Shamba: Swahili word literally meaning “field”

UPS: Uganda Prisons Service

Summary

If you say you’re sick, the warden just kicks you and says, “Even dead bodies must work.”

—Musa, Muduuma Prison, November 12, 2010

The prisoners at Muinaina Farm Prison have been forgotten by the Ugandan criminal justice system. Almost two thirds of the inmates on this rural hilltop have never been convicted of a crime. Some have not set foot in a courtroom in five years. Prisoners plead guilty just to know their date of release. Yet the backlog in the courts allows the prison authorities to profit from these forgotten prisoners because every day the prisoners at Muinaina go to work, farming the lands of the Uganda Prisons Service (UPS), producing the maize meal that feeds inmates at other prisons. Or they dig on the wardens’ personal farms, growing produce that the wardens sell for personal profit. Or they work for private farmers in the area, who pay the prison authorities. On the farms, they are brutally beaten for lagging behind.

They sleep on a cement floor, crowded together in hot cells. There is hardly any medical care available: HIV-positive prisoners are sent to work and are only sometimes excused when they are too weak to keep up; then they may be transferred to Kampala for treatment. Some prisoners cough, violently, night after night, their lungs possibly full of drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB), which is being spread to those around them. “Help us, we’ll die,” pleaded 10 of the prisoners in a note transmitted to Human Rights Watch.

In Uganda, prison conditions at a few, larger, regional prisons have improved in recent years because of the enactment of the new Prisons Act in 2006, partnerships with a few international donors on health, and the work of the Uganda Prisons Service. At these prisons, prisoners can usually access HIV testing and treatment and general healthcare. Overcrowding is less severe and clean water is usually available. But at many of the others, including Muinaina, the conditions and treatment rise to the level of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and even torture.

Between November 2010 and March 2011, Human Rights Watch interviewed 164 prisoners and 30 prison officers at 16 prisons across Uganda, as part of a series of reports on health in prisons in Africa. Human Rights Watch found that poor conditions, forced and corrupt labor practices, routine violence at the hands of prison wardens, infectious disease, and inadequate medical care threaten the lives and health of the 50,000 inmates who pass through Uganda’s 223 prisons each year.

The conditions at some Ugandan prisons are improving but—particularly in rural, former locally administered prisons—are still far below international standards. Overcrowding is endemic, with prisons nationwide at 224 percent of capacity. Of the 16 prisons visited by Human Rights Watch, all but one was significantly over its official capacity, in one case rising to a staggering 3,200 percent of capacity. Prisoners often sleep on one shoulder, packed together so that they can only shift if an entire row agrees to roll at once.

Prison food is nutritionally deficient, leaving inmates vulnerable to infections and in some cases blind; sex is sometimes traded by the most vulnerable for additional food. Water is often unclean or unavailable. At some prisons, boiled water has become a commodity sold by inmates with kitchen privileges. Proper hygiene is difficult with limited government-provided soap, and lice and scabies are rampant. Mosquitoes and malaria are a constant threat, but the prison administration has only sprayed with insecticide at three prisons, and bed nets are forbidden for male inmates because of security fears.

A brutal compulsory labor system operates in rural prisons countrywide. Thousands of prisoners, convicts and remands, are forced to engage in hard labor—cultivating crops, clearing fields—day after day. Compulsory labor is often combined with extreme forms of punishment, such as beatings to punish slowness, and handcuffing, stoning, or burning prisoners who refuse to work. Few prisoners receive proper medical care for their injuries, and prisoners are regularly refused access to medical care because officers will not allow them to miss work. Prisoner productivity translates directly into profit for prison authorities, but prison authorities often do not account for the funds raised through prison labor.

In addition to abuses in the fields, prisoners are beaten and abused within the prison, allegedly as punishment. Inmates are also sometimes confined in isolation cells, often naked, handcuffed, and sometimes denied food; the cells are sometimes flooded with water up to ankle height. Some have had their hands or legs broken, or have become temporarily paralyzed as a result of beatings, and seldom receive medical care. Prisoners with mental disabilities are in some cases targeted for beatings, and even pregnant women are not spared.

The prevention and treatment of disease pose major problems in Uganda’s prisons. TB spreads quickly in the prisons’ dank, overcrowded, and poorly ventilated wards. TB prevalence in the prisons is believed to be at least twice that in the general population, which already is one of the world’s highest. While the prisons service has recently rolled out TB entry screening at 21 prisons, more than 200 still offer none. Prisoners routinely reported having coughed for long periods without having been tested for TB. TB treatment is only available in the prison medical system at Murchison Bay Hospital in Kampala, but even those inmates transferred for treatment may not stay long enough to be cured. TB patients are sometimes sent back to prisons where continued treatment is not possible in order to perform hard labor or ease prison congestion. The result may be drug resistance or death.

HIV prevalence in Ugandan prisons is estimated to be approximately 11 percent, almost twice national estimates. And although sexual activity among male inmates is acknowledged by prison authorities, condoms are universally prohibited because consensual sexual conduct between people of the same sex is a criminal offence. While just over half (55 percent) of the prisoners Human Rights Watch interviewed had been tested for HIV while in prison, rates were much lower at smaller, rural prisons. However, for those who are positive, treatment may be unavailable. Of Uganda’s 223 prisons, prison-based antiretroviral therapy (ART) is only available at Murchison Bay, and even there, ART is sometimes unavailable to those in need of it according to national protocols.

Under Ugandan law, people with mental disabilities should not be detained in prison. But a backlog of prisoners awaiting mental competency determinations, and still more who develop mental health problems once incarcerated, create a significant need for mental health services within the prison system. At upcountry facilities, mental healthcare is nonexistent; even at Murchison Bay, treatment consists only of medication prescribed by a visiting psychiatrist and dispensed by other inmates, with no attempt at psychotherapy or other forms of alternative mental healthcare. Inmates with mental disabilities at some prisons are simply isolated in punishment cells with no treatment.

The health needs of pregnant women are also largely unmet. Pregnant inmates receive little or no prenatal care. Pregnant and nursing women usually receive the same nutritionally deficient food as all other prisoners. And pregnant women are forced to perform hard labor and beaten just like other prisoners, leading to reported miscarriage or injury. Protections for women detainees under regional human rights standards are simply ignored.

The dangerously unhealthy conditions in many of Uganda’s prisons are in part a result of failures of the criminal justice system; prison officers’ inappropriate denials or delays in permitting access to medical treatment; and an under-resourced and inadequate healthcare system that has received limited support from the government and international donors.

Prison overcrowding is a direct result of extended pretrial detention and underuse of the non-custodial alternatives that are available, such as bail and community service. Fifty-six percent of the Ugandan prison population has never been convicted of any crime and is by law presumed innocent. However, remand prisoners often wait for years for their cases to be resolved and are forced into harsh labor conditions alongside convicts. While efforts have been made in recent years to address the case backlog, an insufficient number of judges, judges’ failure to grant bail in accordance with Ugandan law, and inadequate legal representation still conspire to create significant remand times, particularly for prisoners awaiting trial before the High Court. Corruption is reportedly rampant in the criminal justice system, from arrest through trial, so in some cases those remaining in prison are simply those unable to pay the necessary bribe. Children are also sometimes held in adult prisons instead of in juvenile detention facilities, contrary to Ugandan and international law.

Uganda has repeatedly committed itself to upholding the human rights of prisoners through its assumption of international and regional obligations. Under international human rights law, prisoners retain their human rights and fundamental freedoms, except for restrictions on rights necessitated by the fact of incarceration itself. Uganda has an obligation to ensure that its criminal justice and penitentiary standards comply with international and regional human rights standards, to ensure that detainees are treated with appropriate dignity and full respect of their human rights, and to prevent all forms of cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. Uganda is also required to ensure adequate healthcare for prisoners, at a standard at least equivalent to that available to the general population, a commitment acknowledged by the Uganda Prisons Service. Yet medically unqualified prison officers routinely assess the health needs of prisoners and then deny their right to access care.

In Uganda, ill-health, hunger, and poor access to healthcare are not unique to prisoners. However, Uganda has an obligation to ensure basic minimum conditions and healthcare for detainees, to protect prisoners’ rights and public health. The Ugandan government has a binding and non-negotiable obligation not to expose people to torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, which it currently violates when sending them to prison.

Reform is critical: of prison oversight and management and of laws and practices that lead to extended pretrial detention. The Ugandan government and international donors need to prioritize prison funding, while ensuring that corrupt labor practices end. By building on the advice of its own medical staff and that of outside human rights monitors, the Uganda Prisons Service has the opportunity to continue to improve its protection of the rights and health of prisoners, by eliminating the abusive practices that lead to poor health.

Key Recommendations

For Immediate Implementation

The Uganda Prisons Service and Ministry of Internal Affairs should:

- Issue direct orders to stop the use of forced prison labor for private landowners or prison staff;

- Declare a zero tolerance policy for the beating of prisoners and warn that staff and inmates will be disciplined and punished for abuses;

- Carry out regular monitoring visits led by headquarters and medical staff to ensure the health and well-being of prisoners throughout the country and a halt to corrupt labor practices;

- Provide condoms to all prisoners and prison staff, in conjunction with HIV/AIDS education on harm reduction;

- Provide TB screening and offer HIV voluntary counseling and testing to all inmates, and ensure prompt initiation and continuation of treatment for those with confirmed disease;

- Establish guidelines for immediate referral of all prisoners with confirmed TB or HIV to facilities where they will receive treatment, and halt the practice of transferring inmates on treatment away from prisons with treatment capacity;

- Issue direct orders to all officers in charge to allow inmates reporting illness or disability to seek healthcare, and to take responsibility for inmate health.

The judiciary should conduct all bail hearings in open court and the Rules Committee should issue a Practice Direction setting conditions for bail and guidelines on appropriate amounts in line with income levels in Uganda.

For Longer-Term Implementation

The Ugandan Parliament and Ministry of Finance should secure, and international donors should assist with securing, enough funding for the prison budget to ensure conditions consistent with international standards, without reliance on income from forced inmate labor for private landowners.

The Uganda Prisons Service and Ministry of Internal Affairs should establish guidelines on prison-based health services and scale up those services to:

- Establish at each prison nationwide at minimum one trained health worker, with a supply of essential medications;

- Conduct health screenings of all prisoners on entry and at regular intervals;

- Ensure access to prenatal, postnatal, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) services and address the nutritional needs of pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers;

- Ensure access to mental health services;

- Provide prompt referrals and transfer to higher level facilities in the community or prison system for appropriate treatment.

The Ministry of Justice should devise a functional legal aid system to ensure that defendants have access to a lawyer from the time of arrest.

Methodology

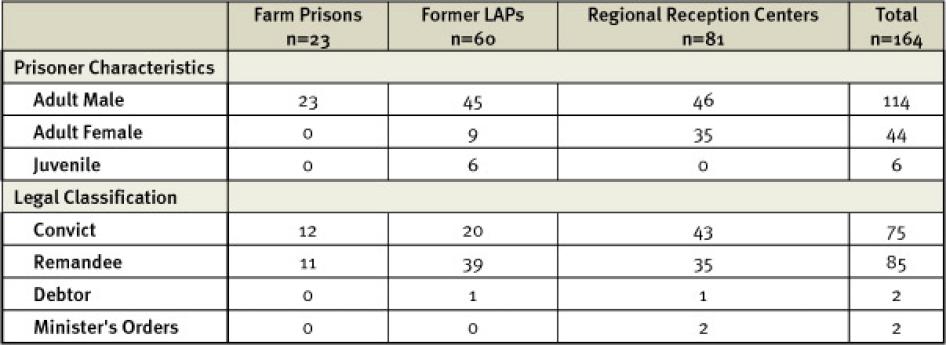

This report is based on 231 interviews, including interviews conducted with 164 prisoners (114 men, 44 women, and 6 children) and 30 prison officers at 16 prisons between November 2010 and March 2011. Prisons were selected to represent a diverse range of facilities based on type, status (formerly locally or centrally administered), size, and level of congestion. Access was granted by the commissioner general of prisons as a part of Human Rights Watch’s routine human rights monitoring in prisons, regularly carried out in Uganda for several years.

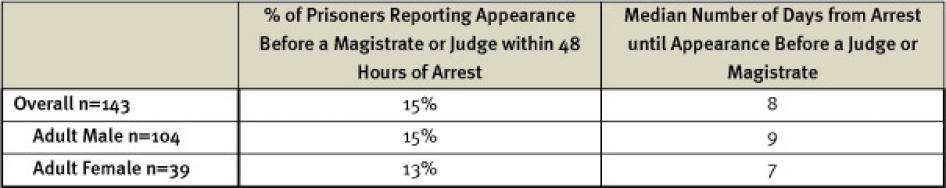

Table 1: Prisoner Interviewee Characteristics[1]

In prisons visited, researchers identified prisoners to approach for interviews in two ways: 1) according to a randomized method involving choosing prisoners from the available prisoner registers, and 2) targeted selection of prisoners to ensure representation of certain categories, including those who had been transferred from one prison to another to receive medical care, individuals identified to Human Rights Watch as having undergone specific types of punishment, and women (particularly women who had been pregnant or who had cared for a small child while in prison).

Interviews were conducted in English or in Lubwisi, Luganda, Lukonzo, Luo, Lusoga, Lwamba, Runyoro-Rutoro, Runyankole-Rukiga, Samia, or Swahili, with translation into English. One interview was conducted in French. The purpose of the research was explained to each prisoner, who was asked whether he or she was willing to participate, and offered anonymity. Prisoners were told that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions without negative consequence. All interviews were conducted privately, with one prisoner at a time. Each prisoner interviewed and quoted in this report has been given a pseudonym to protect the prisoner’s identity and for the prisoner’s security; surnames have been omitted to conceal prisoners’ ethnicities.

Prisoners who were interviewed averaged an age of 31 years. Overall, the most common charges of the prisoners interviewed were theft, murder, and defilement. The time the prisoners interviewed had spent detained ranged considerably between the different types of prisons visited, averaging 22 months, but highest among prisoners at farm prisons (on average 48 months). Prisoners often reported having been moved between prisons, and the time prisoners had spent in the facility in which they were interviewed also varied considerably, but averaged nine months.

Human Rights Watch researchers also conducted facility tours and interviewed 30 prison staff members at the 16 prisons visited, in addition to the Uganda Prisons Service medical authority. In some cases, official titles of individuals are not given for security reasons or at the request of the individual. At the conclusion of field research, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to the Uganda Prisons Service commissioner general of prisons on April 8, 2011, (see Appendix) requesting a response by April 29, 2011 to numerous issues raised in the report; Human Rights Watch did not receive an official response to this letter within the timeframe. Human Rights Watch again requested a response on May 13, 2011, and provided an additional summary of the issues presented in the report on May 16, 2011, at the request of prison authorities. An email response from prison authorities to some of the questions Human Rights Watch had posed was received by email on May 19, 2011, and by letter on June 29, 2011, as this report went to press. That information is reflected throughout the report.

Researchers also interviewed 15 members of the communities surrounding Sentema, Kasangati, and Ntenjeru Prisons (all Central Region), and three prison officers at those prisons, specifically about the practice of hiring out prisoner labor to private landowners.

Finally, researchers interviewed 18 representatives from local and international organizations working on prison, HIV/AIDS, and health issues; health workers within the Ugandan government; and donor governments and agencies.

Caution should be taken in generalizing the results of this research to all prisoners in Uganda. Because Human Rights Watch oversampled prisoners in Kampala-area prisons, which have greater resources than rural prisons, the percentage of prisoners receiving medical testing and care in this report may be greater than the national average. Also, the selection of prisoners within each prison was not perfectly representative. Researchers tried to systematically and randomly select prisoners; however, this was not always possible. Because of the diverse conditions among prisons and because specific groups of prisoners (noted above) were intentionally oversampled, Human Rights Watch has, to the greatest extent feasible, presented disaggregated data according to prison and prisoner type.

This report is part of a series of reports on health in prisons in Africa by Human Rights Watch. The objective of the series of reports is to examine health and human rights issues in prisons in Africa in the context of diverse health and justice policy, reform efforts, and resource availability.

I. Background

The Ugandan Prison System

Uganda has 223 prisons countrywide. Designed to house 13,670, in March 2010 Ugandan prisons were at 224 percent of capacity, with 29,136 male and 1,278 female prisoners in custody.[2] The Uganda Prisons Service employs 6,700 staff, including 6 physicians.[3]

In addition to prisons run by the central government, prior to 2006, local governments administered independent prisons, at which conditions were reportedly grossly inadequate.[4] The Prisons Act of 2006 transferred the functions and administration of these locally administered prisons to UPS,[5] to create one nationwide system. Significant problems remain at the over 170[6] former Local Administration Prisons (LAPs).[7] Although approximately one third of Uganda’s prisoners were housed in former LAPs in March 2010,[8] prisoners in former LAPs constitute the majority of those not served by prison-based health facilities.[9]

Currently, UPS operates two official categories of prisons: reception centers and farm prisons. Although practice varies, in general, remandees and prisoners convicted of petty offences (with sentences less than one year) are kept at reception centers; male prisoners convicted to serve sentences over a few months but less than 10 years, or those with a short period of time remaining on their sentences, are sent to farm prisons. Remand or convicted prisoners facing or serving sentences over 10 years are sent to maximum security reception center prisons.Individual officers in charge (OCs) of prisons are empowered to decide which prisoners, including those undergoing medical treatment, to move to farm prisons; they do so without consultation with medical officials and their decisions are not subject to review.[10]

There is a separate juvenile justice system, with five facilities for children accused or convicted of criminal offences nationwide.[11] Though official statistics indicated no children held in prisons during 2009-2010,[12] in practice children are detained with adults in some.[13]

By law, UPS “shall be provided with adequate resources and facilities.”[14] UPS funding derives from the government of Uganda, donor funding, and “internally generated” revenue.[15] OCs set their budget priorities, which are reviewed and decided upon by prison headquarters in Kampala, with supplies coming almost exclusively in the form of the items requested. The receipt of these items is erratic and undersupply a general problem.[16]

Management of health in prisons is overseen by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the line ministry for the UPS. UPS has calculated that it spends 17,073 Uganda shillings (US$6.96) per prisoner annually on health when dividing its health budget by the prisoners, staff, and staff dependents who use its services; that figure drops to 4,830 Uganda shillings ($1.98) annually per prisoner when factoring into the calculation the members of the neighboring communities who access prison-supplied health services.[17]

Officially, the total UPS health budget was increased by 55 percent between fiscal year (FY) 2009/10 and FY 2010/11.[18] Yet the overall proportion of the prison budget allocated for health services remained a flat two percent.[19] By comparison, the government provides roughly 9 to 10 percent of its national budget to healthcare.[20] In 2009, the commissioner general of prisons admitted to the media that lack of funding had led to deteriorating infrastructure and health in Ugandan prisons.[21]

Health services for the prisons are headed by a national directorate in Kampala. As of March 2011, 63 of Uganda’s 223 prison units had some level of healthcare worker. At the rest, prisoners were expected to rely on the health facilities in the neighboring communities.[22]

The national referral hospital for prisoners is at Murchison Bay Prison in Kampala. Murchison Bay Hospital treats prisoners temporarily referred from other prisons to receive inpatient or outpatient medical treatment,[23] and is the only medical facility in the prison system accredited to provide TB treatment and antiretroviral therapy for HIV treatment.[24] The UPS has established 10 regional health units intended to oversee delivery of healthcare services.[25] Forty-nine additional health “units” across the UPS have healthcare workers. But, in practice, the capacity of many of the facilities is limited: according to the prison medical authority, “we have no doctors at all in the upcountry units, we have zero.”[26]

The Ugandan Healthcare System

While the UPS often relies on community-based health services for prisoner care, healthcare for Uganda’s general population suffers from numerous problems. Uganda’s healthcare system ranks 186th out of 191 countries according to the World Health Organization (WHO).[27] Life expectancy is among the lowest in the world at 52 years; 1 in every 35 women dies as a result of giving birth.[28]

In national healthcare facilities, only half of all posts are filled.[29] Access to healthcare in poor rural areas is especially difficult. Around half of the population does not have any contact with modern healthcare facilities.[30] Some 70 percent of Ugandan doctors and 40 percent of nurses and midwives are based in urban areas, serving only 12 percent of the population.[31]

Healthcare centers,[32] often in dilapidated condition, frequently house patients together in wards, with no privacy regardless of gender or condition.[33] Medical equipment is lacking and where available, often there is no staff, electricity, or water.[34] The government does not supply sufficient drugs and equipment countrywide, leading to frequent drug stock outs and lack of basic supplies such as gloves or disinfectant.[35]

II. Findings

The engagement of a prisoner in doing work as a principle would be ok, but it has to be closely supervised so that it is not abused.... There seems to be an insensitivity when it comes to the mobilization of labor. If a prisoner is on TB treatment, ARVs—you send him to where there are no services? … If they are on TB treatment, and you take them to a farm, you create drug resistance.

—Prison medical authority, Uganda Prisons Service, November 18, 2010

Prison Conditions

Overcrowding

Overcrowding in Ugandan prisons is endemic and by 2019, the UPS projects the prison population will more than double.[36] Contrary to international and Ugandan law requirements that accused people and convicted prisoners be held separately,[37] at every prison visited, all categories of prisoners (convict, remand, and debtor[38]) were mixed.[39]

Although international standards establish basic requirements with respect to prisoners’ accommodations, including with regard to ventilation, floor space, bedding, and room temperature,[40] 15 of the 16 prisons visited by Human Rights Watch were significantly over their official capacity. Fort Portal Women’s Prison was slightly undercapacity; Muduuma Prison, by contrast, was filled to a staggering 3,200 percent of capacity.[41] Prisoners reported wards routinely sleeping twice or three times their design capacity, and prison officers confirmed that congestion is a major problem.[42] At Luzira Upper, in one ward 124 prisoners packed into a space eight meters square.[43]

Prisoners complained about suffering each night in this limited sleeping space and described being “squeezed like iron sheets,”[44] “like chickens,”[45] or arranged nightly by a designated inmate “like logs,” “firewood,”[46] or “sacks of beans.”[47] Most often, prisoners told Human Rights Watch they were forced to sleep in lines, on one side, so packed together that if one turned to his other side, his entire row was forced to do so.[48] Occasionally, also, prisoners reported being forced to sleep in turns,[49] or seated or standing.[50]

Many prisoners said that they slept without any mattress; prisoners frequently reported being given one blanket to lie on and cover themselves. Sometimes two inmates shared a single blanket or mat. Occasionally, prisoners said they were not allowed to have a mattress, lest the ward become so crowded that its inhabitants would not fit in the room.[51]

Such tightly packed wards allow for little ventilation in contravention of international standards.[52] Inmates repeatedly complained of the heat in the congested cells: “We sweat from the bones.”[53] William said, “When your neighbor sweats, all the sweat will be on you.”[54]

At a few prisons, prisoners are forced to stay in their crowded cells day and night. Ugandan law provides that each prisoner have at least one hour of exercise in the open daily.[55] But at Masaka Ssaza and Butuntumura Prisons, the majority of prisoners spent all day and night locked in the overpacked cells because of security concerns about the prison’s perimeter[56] and were permitted outside for only 20 minutes a day.[57]

Food and Nutrition

Deprivation of food in prison constitutes an inhuman condition of detention in violation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[58] International standards require that prisoners be supplied with “food of nutritional value adequate for health and strength, of wholesome quality and well prepared and served.”[59] Under Ugandan law, prisoners are entitled to nutritious food “adequate for health and strength.”[60]

At every prison visited, prisoners reported being given posho (maize meal) and beans once or twice daily, sometimes accompanied by a small portion of porridge for breakfast. Despite a recommended dietary scale including nuts, meat, vegetables, and sugar,[61] prisoners receive only maize meal, beans, and salt.[62] Greens grown by prisoners supplement the rations seasonally at some prisons. However, at others, prisoners reported that the officers confiscated all or a portion of the vegetables grown by prisoners.[63] Mark, at Muinaina Farm Prison, concluded: “We eat greens, but like a goat tied on a rope, the eating is controlled.”[64]

Most prisoners said that the government-provided food was not enough. Prisoners doing hard labor in particular considered food portions insufficient.[65] Julius, at Kitalya Farm Prison, said, “We are eating crumbs. However much energy we use, it is not enough.”[66] Medical personnel and a nutritional assessment conducted by the UPS agreed: “it is not enough for doing hard work.”[67]

Indeed, death records provided by UPS prison authorities to Human Rights Watch indicated that at least one prisoner died in 2010 from malnutrition.[68] The adequacy of the diet in terms of micro-nutrients was also a concern. The prison medical authority noted that:

There is a deficiency in terms of micronutrients, including A and C. Vitamin A is important in the immune system and eyes; vitamin C is important in cellular regeneration when recovering from diseases. These are important because we’re having a population of prisoners vulnerable to infections, and their capacity to recover from and fight off infections is grossly compromised. We see the cases of malnutrition….Especially the long-termers—they develop blindness, and infections like TB.[69]

The lack of adequate nutrition is particularly problematic for pregnant women prisoners and women with small children in prison. Under Ugandan law, “[a] female prisoner, pregnant prisoner or nursing mother may be provided special facilities needed for their conditions.”[70] Some women occasionally reported receiving supplemental milk or eggs during their pregnancy. [71] However, pregnant women typically do not receive extra food rations; they eat exactly the same diet as other prisoners.[72] At Jinja Women’s Prison, those pregnant women who had been exempted from hard labor ate an even less nutritious diet than their non-pregnant colleagues because they did not grow greens which they could eat.[73] Harriet, a new mother at Masaka Main, concluded: “The food we eat doesn’t generate breast milk.... I’m breastfeeding but it’s not enough.”[74] If prisoners choose not to breastfeed, or are unable to breastfeed, they do not consistently have access to formula or safe water with which to prepare it.[75] Despite international standards calling for special provisions for children incarcerated with their parents,[76] and Ugandan law requiring children imprisoned with their mothers to be supplied with “necessities of life,”[77] food is not generally provided for these young children.

Uganda’s own auditor general concluded that the UPS, given its budget and the food grown on farm prisons, would have the capacity to feed prisoners a sufficient diet, but that due to under-declaration and lax oversight of farm production by prison OCs, prisoners’ diets remain inadequate.[78] “[D]ishonest business practices like delivering less quantities of food items,” lack of prioritization (and reallocation of budgeted resources) for food, and the practice of taking prisoners to work on private instead of prison farms led to inadequate food for prisoners.[79]

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene

There is no permanent water here. The kind of water we use is from the ponds we dig.… When you’re in the gardens, some people who are thirsty, if they come across stagnant water, kneel down and drink it. They drink it without the permission of the warden. But if you’re found drinking like a cow, they beat you.

—Martin, Bubukwanga Prison, November 16, 2010

Prisoners frequently told Human Rights Watch that water was insufficient in quantity and that they were constantly thirsty: “Sometimes we get water, sometimes we don’t. There are times we spend a day without drinking.”[80] At Kitalya Farm Prison, prisoners reported that each received approximately one liter of drinking water a day,[81] but it was not enough after a day of hard labor in the sun.[82] Officers in charge confirmed difficulties in supplying their prisons with sufficient quantity of water.[83]

At Bubukwanga Prison, inmates told Human Rights Watch that water did not consistently run from the tap, and they were forced to drink “stagnant water in the roads,”[84] full of small insects,[85] and green or brown in color.[86] At Muinaina, researchers observed the drinking water to be a cloudy olive green color. The OC at Muinaina described the water as “dirty white” and admitted, “It’s not clean.”[87] Indeed, at some prisons, boiled water has become a commodity sold in the cells by inmates with kitchen privileges, in exchange for soap, sugar, or money to those who can afford it.[88]

Under international standards, prisoners must be provided with adequate bathing installations for general hygiene,[89] yet bathing facilities at many Ugandan prisons fall far short of this standard. At Masafu, five prisoners share one basin of water to bathe each day.[90] At Muduuma, prisoners reported that no bathing water at all was provided.[91]

International standards specify that sanitary facilities shall “enable every prisoner to comply with the needs of nature when necessary and in a clean and decent manner.”[92] Despite efforts to overhaul sewage systems at a few prisons in recent years, prisoners at some prisons reported inadequate toilet facilities including the use of buckets.[93] “The most inhuman thing here is the bucket system” that inmates use at night, the OC at Masafu said.[94] At Muduuma, prisoners complained that they were sometimes refused permission to use the existing toilet facilities because they were located outside of the prison’s perimeter, and received beatings for making the request.[95]

International standards also require that prisoners shall be provided with toilet articles necessary for health and cleanliness[96] and separate and sufficient bedding that is “clean when issued, kept in good order and changed often enough to ensure its cleanliness.”[97] Ugandan law makes provision for prisoners to receive toiletries.[98] Yet, across prisons visited, prisoners and prison officers frequently reported an inadequate supply of such basic necessities. Prison officers admitted that, to give prisoners soap on a regular basis, part of the funding had to come from the proceeds of prisoner labor on private farms.[99]

Physical Abuse

Hard Labor

Thousands of prisoners are forced to engage in hard labor. They cultivate crops, clear fields, or fetch firewood and water. Prisoners, convicted or on remand, work often in oppressive conditions, in heat or rain, sometimes intentionally denied food, water, or bathroom breaks.[100] They are beaten as punishment for being slow or to instill fear upon arrival at prison, handcuffed, stoned, or burned if they refuse to work. Vulnerable prisoners, including children, the sick, elderly, and pregnant women are also beaten and forced to work.[101]

International legal standards place important constraints on how prison labor may be used. Under the United Nations (UN) Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, adopted by the United Nations as guidance, prison labor must not be of an afflictive but rather of a vocational nature, and prisoners should be allowed to choose the type of work they wish to perform.[102] The work must not be driven by financial profit motives.[103] No prisoner, whether remand or convict, should be forced to work for private entities, such as private landowners.[104] When working for the government, only convicts and not remands may work, and they must be medically assessed to see if they are fit and healthy for work,[105] they must be treated and remunerated fairly on terms close to what free workers receive, they should be male and between the ages of 18 and 45, and may not work more than 60 days a year.[106] Currently, Ugandan prisons do not comply with any of these international standards.

The practice of compulsory labor is longstanding in Ugandan prisons. In 2003 the government of Uganda wrote in its report to the UN Human Rights Committee that the “illegal and exploitative” practice of hiring prisoner labor to private individuals is a “common feature.” Enforced hard labor of non-convicts was at the time “rampant and therefore tantamount to painful punishment without conviction.”[107] In April 2011 according to the government-owned New Vision newspaper, the Uganda Prisons Service announced a new policy to the parliamentary public accounts committee that all prisoners would be paid 100 to 500 Uganda shillings ($0.04 to $0.21) per day for labor.[108] At time of writing, it was unclear to what extent this new policy had been put into practice.

While according to international standards, the safety and health protections in place for non-prison labor are supposed to be in place for prisoners,[109] prisoners in Uganda face greater risk of injury compared to free laborers because of abusive practices, including being made to work closely together or being beaten so that they will walk quickly through rough terrain without shoes, “like a herd of cattle.”[110] Prisoners spend long hours each day doing forced labor,[111] resulting for many in chest pain, ulcers, and fatigue.[112]

Many prisoners said they had to work while actively ill or injured, particularly if they suffered from illnesses that were not immediately visible. Prisoners often said that “there was no time to go to the hospital” because they were forced to work in the fields and were denied permission to miss work in order to receive care.[113] One prisoner, echoing an expression heard many times by researchers, said that prison authorities “were telling us we didn’t come to a hospital, we came to a prison and should work.”[114]The health consequences of prisoners’ hard labor may be severe: One prisoner died in Mubuku Prison while working in the field in November 2010. The exact cause of his death is unclear, but witnesses who saw the incident recounted that he was beaten and his numerous expressions of thirst and requests for water went ignored by prison authorities.[115]

Abuse in the Fields by Wardens and Other Inmates

They [the wardens] took the sick to work. They would take me to dig. They used to start the digging at 6am, and dig at high speed—but when the sun would rise up and the heat raise, I started feeling dizzy and in most cases I would fall down. I was beaten by the katikkiros [prisoners with disciplinary authority], claiming I was faking illness, until one time when this happened to me, the katikkiros beat me, but the wardens stopped them because I couldn’t move, and they ordered I should be taken back to the prison. I lost consciousness, only to wake up to see I was in the ward.

—Henry, a remand prisoner from Muinaina Farm Prison, interviewed at Murchison Bay Prison, November 20, 2010

At the 11 prisons visited by Human Rights Watch where prisoners were engaged in compulsory labor, prisoners reported routine, brutal beatings in the fields.

Prisoners said they were beaten by both prison officials and other prisoners with disciplinary authority, most commonly with sticks or canes. Beatings occurred for a range of reasons: if prisoners lagged behind others in their work, if they said they were sick, if they made errors in their work, if they straightened up to stretch their backs.[116] At Kitalya Farm Prison, Human Rights Watch researchers observed a prisoner with disciplinary authority hitting prisoners with a stick as they unloaded maize from a truck.[117]

Prisoners at Muduuma and Kitalya Prisons said new arrivals were beaten in order to preemptively instill fear, as work in open fields heightened the opportunity to escape.[118] Some were beaten together in groups as large as 25, each with legs and hands tied behind his back with rope.[119] Wardens and other prisoners then beat them with sticks, batons, or slashers, metal rods with a blade used typically for cutting grass.[120]

At some prisons, prisoners reported unique and especially brutal punishments. Four prisoners from Muinaina Farm Prison independently confirmed that prisoners who worked slowly had dried grass or banana leaves placed on top of them and set afire.[121] One was himself a victim while the remaining three said they observed this practice in at least two incidents in 2009. One from Muinaina Prison said he was forced to sit on an anthill to suffer ant bites.[122] Remand prisoners at Muinaina once refused to go to work in the fields after a new OC initiated a policy of making all prisoners, whether remand or convict, work. They were handcuffed to a tree all day, every day, until they succumbed.[123] Female prisoners from Jinja Women’s Prison recounted working in waist-deep water to cultivate rice for the wardens, as leeches attached to them.[124] The wardens, themselves unwilling to get wet, threw stones at prisoners to punish them.[125]

Despite the prohibition in Ugandan law that “[a] prison officer shall not employ a prisoner in the punishment of a fellow prisoner,”[126] and prohibitions in international standards on prisoners being employed in any disciplinary capacity,[127] some prisoners are given authority to punish other prisoners. One prisoner who was promoted through the ranks said that the prison authorities told him, “Don’t go back to the hoe. Now you have a stick.” He described an intricate hierarchical system in which he oversaw other prisoners, who themselves oversaw squads of 20 prisoners, called a “bicycle.” He said, “I can even beat commanders and say, ‘Your bicycle is not moving.’” If he beat a commander, the commander was then required to beat all 20 prisoners in his bicycle.[128]

The Economic Incentives behind Prison Labor

The money they are receiving for us, where do they put it?

—Ali, a former inmate at a farm prison, interviewed at Murchison Bay Prison, November 20, 2010

Testimony of forced hard labor and abuses was most frequent at farm prisons, or former LAP prisons in rural agricultural communities. Prisoners at those prisons said that they were hired out to work on land for private farmers and on land owned or rented by prison authorities. Because their productivity translated directly into profit for prison authorities, who sold the food harvested from their land or were paid per job by private landowners, they forced prisoners to work for long hours, with little rest, even despite illness or injury.

Prison OCs told Human Rights Watch that they needed the income produced by prison labor to meet the operating costs of the prisons.[129] Four OCs said that they received only 150,000 Uganda shillings (approximately $63) or less per month in addition to in-kind supplies from the prison administration in Kampala, leading to a shortfall which they met by contracting out prison labor.[130] As one OC said, “From the working arrangement, we use the money [the prison receives for private work], if it wasn’t there, then we wouldn’t be surviving, we wouldn’t be running the institution. Because of that, we buy milk for the kids, we buy fuel and repair the vehicle, we put a latrine in the female section.”[131] Another OC explained that, “Labor is not part of their sentence. Labor is just an activity that we subject them to for us to be able to keep them and rehabilitate them somehow.”[132]

OCs said that the prison administration knew of and indeed encouraged the practice of contracting out prison labor, as it was a display of initiative by OCs to ensure that their prisons were well run. One OC reported:

There is a language of initiative in the prisons. But they need to define the limits. The regional command had already told the commissioner, no prison in the region will be using a bucket toilet. He said to us, we should put water-borne toilets in the ward at your cost, don’t ask for any money. By December, all prisons in the Eastern region will be using water-borne toilets. But it is an uphill task….I talked to an engineer, and that will take 12 million shillings [approximately US$5,100].[133]

Prison authorities are not required to account fully to the prison administration in Kampala for the earnings from contracting out prisoner labor, potentially fueling corruption. One OC said that a senior colleague, also in the UPS, had told him when he was promoted, “Eat on the job, but don’t eat the job,” which he took to mean that it would be acceptable to personally gain from prison labor as long as he ensured that the prison could operate.[134] An OC of a farm prison informed Human Rights Watch that he intentionally underreported the amount of food his prisoners produced.[135] Uganda’s auditor general has criticized the “laxity in supervision and accountability for the food grown on the prison farms.”[136]

Generally, three models of prison labor exist. In the first, prisoners work on official farm prisons, farming government-owned land.[137] The produce from this activity is intended to go to Kampala for distribution to prisons nationwide. However, sometimes prison officers keep behind a portion of it to meet prison operating expenses. One OC said:

We declare estimates to Kampala [UPS headquarters]. If we expected 100 bags [of produce], we declare 80. You can’t complain to the boss all the time, or else he will call you a failure. You have to take your initiative. The resources we get from the central government are small, minute. Maybe the government should inject in more funds. The 20 bags sold off don’t make it into the books. The auditors don’t understand.[138]

Second, prisoners are contracted out to private farms at rates ranging from 2,500 to 3,500 Uganda shillings (roughly $1.00 to $1.50) per head per day, significantly lower than what free workers would earn, approximately 7,000 to 10,000 Uganda shillings ($3.00 to $4.25) a day.[139] Private farmers hire prisoners to work on their own land and pay the prison OC directly for the labor. Prison staff takes bookings for prison labor by phone or in person, and payment must be made in advance.[140] Injuries sustained by prisoners while working on private land are the responsibility of the prison and not the private farmer.[141] Private farmers must pay for transportation of the prisoners and may rent additional equipment such as hoes from the prison. They are responsible for providing some food for the prisoners and may also pay the accompanying wardens tips ranging from 5,000 to 15,000 Uganda shillings ($2.00 to $6.25) per day per warden to ensure that prisoners’ productivity is high.[142]

According to prison authorities, hiring labor out to private landowners can be done by the OC “for improvement of administration of his Prison.” It “can only be done as a form of employment in which the inmates will have to earn a statutory fee.”[143] Only prisoners who have been convicted of petty offences are permitted to work on private land.[144] Currently, Ugandan prisons violate their own policy.[145]

Media reports have speculated that wide-ranging police sweeps of people in slum areas of Kampala have been driven by the prison authorities’ desires to have free manpower to contract out to private landowners.[146] Prisoners at Muduuma Prison told Human Rights Watch that police engaged in large-scale street sweeps, accusing them of being “rogue and vagabond,” a vaguely defined crime akin to loitering, releasing those who could pay and taking the remainder for hard labor.[147]

In the third model, prisoners cultivate directly for prison OCs and wardens, who sell the produce at a profit. Officially, prison officers can have prisoners work on officers’ own “small gardens…usually once a week on Saturdays.”[148] One OC stated that he personally earned approximately 1,000,000 Uganda shillings ($425) per season and estimated his wardens each made 500,000 to 600,000 Uganda shillings ($200 to $250) per season, the equivalent of two to three months’ wages, by selling the produce that prisoners cultivated on their land.[149] Prisoners with prior experience in agricultural trade placed estimates of the OC’s stock to be several times the amount he reported to Human Rights Watch.[150] Inmates at the same prison, where remand times were on average five years, believed that their prolonged pretrial detention was in part due to the desire of prison wardens to profit from their labor for a considerable period of time. Human Rights Watch observed storage at the prison of the OC’s private maize and rice stock, which he said he planned to sell.[151] Inmates not only cultivated but also processed the maize from the OC’s private stock, and some prisoners observed private sellers paying the OC within prison grounds.[152] When the prisoners raised the issue of their hard labor with the regional prisons commander, they received no assurances that any of these practices would stop.[153]

Wardens and OCs also benefited personally from prisoners in smaller ways by forcing them to clean their houses or do their laundry, allegedly stealing church-donated goods or food given as payment for labor, and in one instance, having them build the OC a new house.[154]

Prison authorities wrote to Human Rights Watch, saying, “Where prisoners are forced to work without pay, that’s abuse. In my tours, I am yet to meet this. The Officer in Charge of the Prison must keep an inventory of these activities that will have to be checked by the Prisons Inspectorate and the Regional Prisons Commanders.”[155] However, at Kitalya Farm Prison, where Human Rights Watch had to go to the fields to retrieve prisoners from their work for interviews, each of the prisoners interviewed reported that only prisoners with disciplinary authority are ever paid for their work; all others receive nothing.[156] Indeed, the vast majority of prisoners Human Rights Watch interviewed who did hard labor reported being forced to work without pay. At some prisons, prisoners were paid nominal amounts of money, around 200 to 500 Uganda shillings per day ($0.09 to $0.21), or received small amounts of food, soap, or cigarettes as payment, but in most instances, prisoners received nothing.[157]

Punishment

Ugandan law lays out disciplinary procedures for prisons.[158] And some of the punishments currently inflicted are in line with Ugandan and international law: Prisoners may lose the possibility of early release,[159] be given additional cleaning or field work,[160] or denied visitors.[161] For serious unlawful offences committed in prison, a prisoner can be criminally charged, prosecuted, and convicted with an additional sentence.[162] Yet, at almost every prison Human Rights Watch visited, prisoners overwhelmingly reported beatings and the use of isolation cells flooded with water while the prisoner was forced to be naked, beaten, and given limited food as the primary punishments.[163]

Beatings

They hit me so hard, I was crying blood.

—Edmund, Muinaina Farm Prison, March 4, 2011, describing a beating by prison wardens and other inmates

Severe beatings—in the fields as described above but also in the prisons themselves—conducted as punishment either by the wardens or by inmates with disciplinary authority, were reported by prisoners at nearly all prisons visited by Human Rights Watch. Overall, 41 percent of the prisoners interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had been beaten; 87 percent of prisoners at farm prisons had experienced a beating.

Corporal punishment is forbidden in Ugandan prisons[164] and international law forbids cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and torture.[165] Prison officers told Human Rights Watch that they knew corporal punishment was banned and frequently contended that it had been abolished in practice.[166] Yet prison medical staff acknowledged that they had observed injuries inflicted by prison wardens: A health worker at Murchison Bay Hospital reported that most of the injury cases he sees are inflicted either by police or prison staff,[167] and the prison medical authority admitted that he had heard of “instances” where “this has cropped up.”[168] Additional human rights monitors have noted the frequent, continuing, use of beatings, despite its official abolition.[169]

An assistant commissioner of prisons is charged exclusively “to monitor human rights abuses in prisons.” According to prison authorities, four OCs have been removed from their positions due to infractions, and an additional two OCs and two junior officers are currently facing criminal charges for assault of inmates.[170]

At every prison visited but one,[171] prisoners reported that caning still takes place; at most, it is the primary form of punishment. At Bubukwanga Prison, researchers touring the prison were confronted with a prostrate inmate, writhing on the floor and moaning in pain. He said: “I’ve been beaten by the OC, he hit me. He left me very badly off. He said I had stolen, and he beat me with a big cane. He beat me this morning.”[172] He showed researchers the marks the beating had left on his body. Other prisoners confirmed that they had seen the OC beat him that morning, for allegedly stealing some sugar from another inmate.[173]

At some prisons—in particular Luzira Upper, Fort Portal Men’s, and Muinaina Farm—prisoners reported marked decrease in frequency and severity of caning in recent years.However, inmates across facilities still consistently reported routine beatings by wardens: At one prison, several prisoners described being held by each arm and leg as they were beaten on the buttocks and back of the head with a stick.[174] According to one inmate, the OC said, “This is the stubborn part,” as he beat prisoners’ heads.[175] Prisoners reported receiving beatings of varying severity, from five strokes to “so many times I could not count.”[176] The instruments include batons, canes, sticks, whips, electric cable, and wire.

Despite prohibitions in Ugandan law and international standards on prisoners being employed in any disciplinary capacity, prisoners with disciplinary authority also mete out punishments within the prison.[177] At some prisons, prisoners reported having been beaten by prisoners with disciplinary authority in the wards on the orders of wardens or as they watched and tacitly approved.[178]

Several prisoners with mental health problems reported being targeted for beatings by inmates with disciplinary authority because of their mental disabilities.[179] As Ali, one inmate in the “mental health” cell at Murchison Bay, observed, “The cleaner [an inmate with disciplinary authority] will say, ‘Stay in the wards,’ and if you go out—you are beaten. But these people [with mental disabilities] don’t see things in the normal sense. They are punishing people for being mentally sick.”[180]

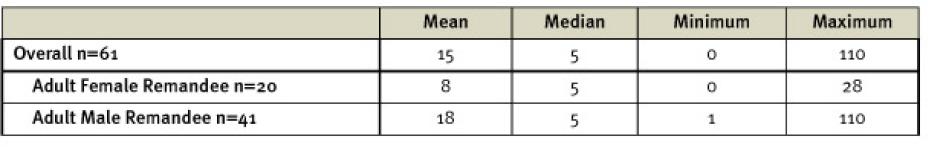

Table 2: Prisoners Reporting Beatings, Health Problems as a Result of Beatings, and Medical Care for Their Injuries

The health effects of beatings may be severe. Prisoners described how beatings in some instances caused loss of consciousness, or partial loss of hearing,[181] while others sustained broken legs as a consequence.[182] One prisoner described how he had been beaten so badly by a warden that he was unable to walk for a month.[183] Another prisoner recalled an incident he had witnessed at a farm prison:

They caned him, and he fell sick. The whole buttocks was rotten. In the ward where I was sleeping, you feel like dying; he lay on the floor crying. This boy received no treatment. But the smell was too much. After some time, we went to the OC’s office, and said, “We are not going anywhere. We need our colleague to get treatment.” The OC reached the door [of the ward], and smelled the stench, and saw the flies. He said the man should get treatment. But even after treatment, he still could not sit. He was totally rotten.[184]

Injuries from beatings at Kitalya Farm Prison were so common that one inmate said, “there was a time from May to October last year when the nurses here were no longer treating us for malaria, they were just treating us for wounds on our buttocks from beating.”[185] But treatment for these injuries is for many an unattainable luxury: only 15 percent of prisoners who told Human Rights Watch they had suffered a health problem as a result of a beating had received treatment, and none of those at former LAPs had received treatment. Matthew, a prisoner at Masafu, experienced a beating so severe that his hand was broken, but the prison warden who beat him would not allow him to go to the hospital.[186]

Isolation Cells

Under Ugandan law, an OC may order a prisoner confined to a separate cell for a period not exceeding 14 days on disciplinary grounds.[187] The law explicitly states that “[s]tripping a prisoner naked, pouring water in a cell of a prisoner, depriving him or her of food and administering corporal punishment and torture is prohibited.”[188]

Yet, at 9 of the 16 prisons visited,[189] Human Rights Watch researchers found that isolation cells were used for punishment, sometimes in conjunction with each of the aggravating factors specifically prohibited by law. Prison officers confirmed the use of isolation cells, but denied the additional deprivations.[190] At four prisons, Human Rights Watch researchers were able to tour the cells used for prisoners’ isolation and found them to be bare cement structures, with a bucket for a toilet, with sizes ranging from one meter by one meter to four meters by five meters. At Luzira Upper Prison, “never forget me” and “broken hands” had been etched into the wall of one of the cells. Prisoners said that isolation can range from a few hours to two weeks, as specified by law, but also noted that it could last in some cases from months to a year[191] depending on the prison and offence.

Despite the explicit legal prohibition, at many prisons a prisoner held in an isolation cell would likely also face a combination of handcuffing, reduced food, water poured on the ground to ankle depth,being stripped naked, and beatings. No toilets are typically available in the cell, so prisoners use a bucket or even a paper bag for their excrement. Esther described the conditions:

They completely undress you, and pour water in there….It’s very cold in there because of the water. I have been there. In the cell, there is something that retains the water and there are so many mosquitoes breeding. The water is very cold, and your body reacts badly. One woman was taken there on her period—she was undressed, and she spent time in blood mixed with water.[192]

Being confined in an isolation cell, compounded with the abuses described above, has a serious effect on inmates’ physical and mental health. Inmates were described as “sick,”[193] “not well,”[194] “swollen,”[195] “yellow and with a rash on their body,”[196] with “burns,”[197] “moving in a zigzag,”[198] or “weak and can’t walk,” [199] after they had been put in isolation and subjected to other abuses including beatings. One prisoner at Luzira Upper said that he had seen three people die there since 2005 as a result of beatings or mistreatment prior to or during incarceration in the isolation cells,[200] but the deaths could not be independently verified. Another prisoner reported one inmate who had been confined to an isolation cell for two months began cutting himself with a razor blade.[201] “When they will take you to the cells, that’s when people change,” concluded Abdul.[202]

The most fundamental protection for prisoners in international and Ugandan[203] law is the absolute prohibition on torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. There is little doubt that the use of these cells to inflict punishment constitutes prohibited inhuman and degrading treatment. Extended use of these cells when combined with other punishments, such as handcuffing, being stripped naked, food restrictions, and being made to stand ankle-deep in water, constitutes a form of torture.[204]

Prisoners may also be confined in isolation cells (typically without being stripped or forced to stand in water) not strictly as punishment, but as a result of officers’ inability to appropriately handle and offer treatment for their mental health problems. At Jinja Main Prison, researchers found one prisoner with what a warden described as “mental problems” occupying an isolation cell, who informed researchers that he had “not been receiving medicine” and that he had not been seen by a medical professional or offered any treatment.[205] “We have an isolation cell for psychiatric cases or for those who have failed to be disciplined,” admitted the deputy OC at Jinja Main. But, he contended, “We base it on the medical staff to give us the right information.”[206] Tumwesigye described a fellow prisoner at Jinja Main, “not a very stable man,” confined in an isolation cell for a full year.[207]

Prevention and Treatment of Disease

All people have a right to the highest attainable standard of health,[208] and under international law, states have an obligation to ensure medical care for prisoners at least equivalent to that available to the general population.[209] States also have an obligation to meet a certain minimum adequate standard of prison health conditions and care to individuals in detention, regardless of a state’s level of development.[210] The Human Rights Committee, the monitoring body of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, has determined that danger to a detainee’s health and life as a result of the spread of contagious disease and inadequate care constitutes a violation of that treaty.[211]

Under Ugandan law, prisoners are also entitled to “have access to the health services available in the country without discrimination.”[212] The UPS acknowledges its legal responsibility to ensure healthcare services equivalent to those available in the general population.[213] Yet, the prison medical authority admitted that equivalence does not currently exist.[214] HIV and TB, which occur at high rates in the prisons, pose particular challenges. Incomplete and delayed reporting of health conditions from prisons hinders the development of appropriately tailored interventions for these and other health conditions.[215]

Tuberculosis

For TB, the rate is almost two, three, five times the rate in the general community, depending on which region you look at…. The prisoners enter, it makes them worse, it makes those who haven’t come in with diseases acquire them. If we inappropriately handle them—causing drug resistance, as for TB—we act as a petri dish, then they just give it back to the community.

—Prison medical authority, Uganda Prisons Service, November 18, 2010

Transmission

The conditions in Ugandan prisons—combining overcrowding, frequent housing together of the sick and healthy, poor ventilation, and lack of natural light—facilitate the transmission of tuberculosis.[216] “If one prisoner has Tuberculosis (TB) in a room filled with 50 inmates, at the end of a day, everyone will be infected,” the commissioner general of prisons has said, according to media reports.[217]

TB prevalence, already high in Uganda’s general population, is significantly higher in the prison population. Uganda is ranked 16th of the World Health Organization’s 22 high-burden countries for TB worldwide[218] and in 2010 had a prevalence rate of 330 cases per 100,000 members of the population.[219] In 2008, the UPS and UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimated that Ugandan prison TB prevalence was 654 cases per 100,000, almost double national population prevalence.[220]

The Prisons Service acknowledges that TB education programs thus far have been limited.[221] However, the risk of contracting TB through the coughing of their fellow inmates was not lost on many of the prisoners. As Johnson, a prisoner at Bubukwanga who had coughed for the entire five months since he had been detained, said, “I am sure I could be infecting other people. You see, here we sleep in one room—sometimes 70 people, or 80. If you are sick, definitely you will infect others. If they are also sick, they will infect you.”[222]

Testing

We worry a lot when people are coughing that we might catch the disease. No one has ever checked us for TB here. Normally when the nurse comes and people complain about the cough, he says, “I don’t have the gadgets to test you.” He gives you some tablets and says, “Let’s see what will happen next.”

— Owen, Kitalya Farm Prison, February 28, 2011

Regular TB screening is a well-established cornerstone of prison health. Since 1993 the WHO has explicitly recognized the need for “vigorous efforts” to detect TB cases through entry and regular screenings in prisons.[223] On Human Rights Watch’s visits to Ugandan prisons, screening for TB was taking place only at a few of the reception centers located near larger towns.[224] The prison medical authority reported that entry screening had recently been scaled up to 21 prisons from three original pilot sites,[225] and he has plans to scale up entry screening for TB further.[226] But he admitted: “We are wondering why we stayed too long to do that. The findings are shocking.”[227] Outside the major reception centers, TB screening for prisoners upon entry is not taking place.

Twenty-eight percent of male prisoners and seven percent of female prisoners interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had been tested for TB during the period of their incarceration. Twenty-two percent overall, the percentage of prisoners tested for TB varied between categories of prison and fell to only 11 percent at former LAPs.

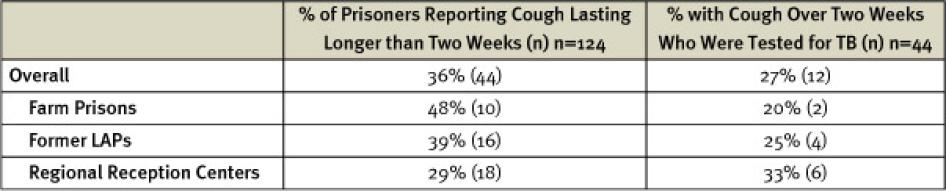

Just over one-third (36 percent) of prisoners interviewed said that they had coughed for longer than two weeks since incarceration, but nearly three quarters of these prisoners had not been tested for TB (28 percent had been tested). Some of those prisoners who had been tested had never received the result.[228]

Table 3: Prisoners Interviewed Reporting Cough Longer than Two Weeks Tested for TB

Case detection rates for TB in the UPS are unknown,[229] but it is widely acknowledged that infectious TB patients are not being identified. The director of the national TB program speculated: “TB missed? It must be big. Transmission in prisons may be 10 times higher than in the general population. When you miss one, it is catastrophic.”[230]

Preliminary results from a recent national drug resistance survey suggest that between one and two percent of TB cases are multi-drug resistant (MDR-TB).[231] In the prisons, testing for drug resistance exists only at Murchison Bay Hospital; the prison medical authority acknowledged that drug-resistant cases undoubtedly exist but are not detected.[232]

Treatment

Uganda has been making progress in treating TB in the general population, though significant gaps exist.[233] Among the prison medical facilities, only Murchison Bay Hospital is accredited to manage TB.[234] Elsewhere, the prison medical authority envisions that TB suspects will be transferred to regional prison health units, which will establish contact with nearby public health facilities or, where there is no regional unit, will be referred to the public health system. But as the prison medical authority admitted, “It could be possible there are those not on treatment.”[235]

Inconsistent or incomplete adherence to the eight-month treatment course risks creating drug resistance. Saul was told by medical personnel at the public hospital to stop taking his TB medication after two and a half months but was still coughing at the time of his interview.[236] Prison authorities reported that at least three prisoners died of TB in 2010.[237] Prisoners and prison officers at some prisons reported that there were no medications for TB available at the prisons or at nearby health centers for prisoners with TB.[238] As Gilbert at Kitalya Farm Prison noted, “The nurses tell us there is no medicine, but there are quite a number of them [prisoners] who do cough. I worry about it because those who are suffering from TB, they are here. They are not isolated, and they receive no treatment.”[239]

The development of drug resistance because of transfer to a farm prison, or upon release, is a major concern of prison health officials.[240] The prison medical authority has noted that inappropriate referrals to upcountry prison centers for hard labor of patients on TB treatment risk creating drug-resistant TB.[241] While Ugandan law provides for prisoners under medical treatment to be linked to medical or social services upon discharge,[242] and prison medical officers reported trying to make efforts to link discharged TB patients to appropriate services, they noted that those released from court and others were still released before finishing their course of treatment without being linked to services near their homes.[243]

HIV/AIDS

When I told the prison officer I was HIV-positive, he said, “Fight on, complete the sentence, go home, and get treatment.” It meant he can’t do anything for me. There were wardens I informed. They said prison has nothing to offer me.

—Robert, Masafu Prison, March 8, 2011

In 2009 Uganda had an adult HIV prevalence rate of 6.5 percent.[244] Prevalence in Uganda’s prisons is even higher: a 2008 study found a general prevalence of HIV among prisoners of 11 percent.[245] Yet human rights monitors have continuously found that prisoners have limited access to HIV testing and treatment.[246]

Transmission

Sexual activity occurs in Ugandan prisons. Male prisoners at Murchison Bay, Luzira Upper, Masaka Main, Muinaina Farm, and Kitalya Farm Prison, all larger prisons with longer-term inmates, repeatedly told researchers that they had heard of, witnessed, or participated in sexual relations and same-sex relationships between inmates, particularly involving prisoners in authority positions. Prison wardens and officials confirmed that sexual activity takes place.[247]

Most frequently, prisoners reported that lack of food and other basic necessities led inmates to trade sex for those items.[248] Gilbert concluded: “The cause is the conditions. Some people will receive visitors and be able to have something. They use the power of their resources to entice others with doughnuts or sugar.”[249] As Mukasa, at Luzira Upper, described, “These are the things that happen in a closed environment. There is some homosexuality…. As a young man, they give you tea, and you can end up giving in. They say, ‘You are now a woman,’ once they get you.”[250]

Prisoners also said that rarely they had heard of instances in which individuals were forced into sexual activity.[251] Given the heavy stigma attached to same-sex sexual relations in Uganda, according to Joshua, “Most of them negotiate. It’s very difficult for someone to force. They will catch you and punish you.”[252] Yet sexual coercion does occur. As one prisoner described, “Sometimes, when you are sleeping together in the night, you will feel someone touching you. Sometimes people are forced in the corridors during the day, but at night, if someone touches you, you shout.”[253]

In addition to being subjected to caning or confinement in isolation cells as punishment, prisoners found to be engaging in sexual conduct with others, whether discrete consensual acts or longer-term relationships, are subjected to sexual humiliation in some prisons. According to Jacob:

Sometimes when people are caught having sexual intercourse, they are put out in the field and made to walk around naked. The chiefs in the wards help to identify them. If you are caught red-handed, you are taken to the prison wardens. To try to control the activities, they have undressed those who are caught, and have made them walk around the [area surrounding the prison], to make them ashamed.[254]

International organizations—including WHO, UNODC, and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)—all recommend that condoms be provided to prisoners.[255] Homosexual sex is illegal in Uganda.[256] Its criminalization, itself a human rights violation, has the added result of creating stigma and fueling transmission of HIV, particularly as it leads prison authorities to deny condoms to inmates. UPS concludes that “notwithstanding the existence of incontrovertible evidence of MSM [men who have sex with men], the distribution of condoms to prisoners in custody is not possible….Exploring the possibility of introducing condoms within the existing legal regime will continue to be our priority.”[257] According to the prison medical authority, “I know our interventions are not as effective as we wish them to be—we are legally bound.”[258]

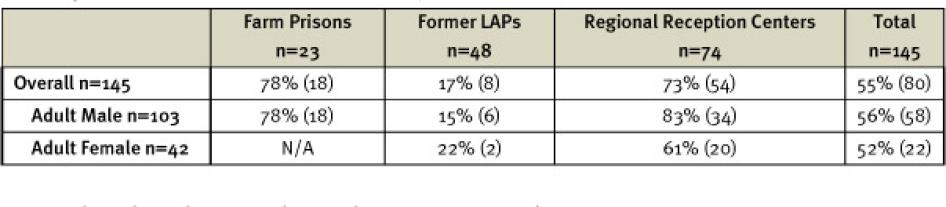

Testing

HIV testing has increased in some prisons in recent years, and overall, 55 percent of prisoners interviewed who did not already know they were HIV-positive when they entered prison reported having been tested for HIV during their incarceration. A prisoner entrusted with medical authority at Luzira Upper claimed that all new entrants are now offered HIV counseling and testing.[259] HIV testing at other prisons is offered in partnership with nongovernmental organizations.[260] Some prisoners also reported receiving diagnostic HIV testing at health centers when allowed to go out to receive healthcare.[261] More rural prisons, however, still lack completely both HIV screening upon entry and diagnostic testing for those who fall ill. At former LAP prisons, only 17 percent of the prisoners interviewed by Human Rights Watch had been tested for HIV during their incarceration. The prisons service acknowledges limited capacity for HIV testing because of inadequate staff, lab infrastructure, and lack of motivation among counselors.[262]

Table 4: Prisoners Interviewed Tested for HIV While Incarcerated, % (n)

Researchers heard reports that at those prisons conducting HIV testing, some prisoners were subject to mandatory testing, as opposed to the voluntary testing required by international best practice.[263] Enid, at Luzira Women’s, said, “Whether, you want it or not, you’re tested here.”[264]

Treatment

I’m positive. All the wardens are aware. Even the OC is aware. I’m not getting medicine. I used to get medicine. I left my medicine out there [outside of prison]. The warden beat me so much, I even fear asking to go to the hospital. Since my arrest up to now, I’ve not been taking my medicine.

- Matthew, Masafu Prison, March 8, 2011

Uganda has in recent years scaled up treatment, though significant challenges remain.[265] Estimates as to the number of prisoners receiving HIV treatment vary significantly.[266]

In 2011 prison-based ART services were only provided at Murchison Bay Hospital to residents of the Luzira/Murchison Bay Prison complex in Kampala. HIV-positive prisoners at other prisons were intended to access services at outside community clinics[267] or to be referred to a regional health facility (where they would access services at public facilities) or to Murchison Bay. The prison medical authority highlighted the HIV treatment gaps: “Upcountry, we don’t have any prison health unit accredited for ARVs. If you are positive and on antiretroviral drugs [when you come into prison], you would be in trouble. There is no mechanism for you to get these supplies….We have those who are positive. But no counselors, no access to public health facilities. What do we do?”[268]