Glossary of Slang

“Cats” [chhma]: detainees tasked to watch over “mice” (other detainees)

“Deputy room captains” [anuk kang]: detainees with authority over other detainees of a particular room inside a center, under a “room captain”

“Eat ice cream” [si karem]: perform oral sex

“Eating betel nut” [si sla]: punishment of running against a wall until the detainee’s mouth bleeds

“Eat fully” [si chh 'eth]: have sex

“Frog leaps” [lauth kangkep]: punishment of leaping forward from a squatting position for a certain distance

“Ice” [teuk kak]: methamphetamine in crystal form

“Leader of a work group” / “Deputy leader of a work group” [mei krom / anuk krom]: detainees with authority over a work group (of 10 or so other detainees) under a “room captain” and “deputy room captain”

“Ox’s penis” [k'dor ko]: a police baton

“Room captain” [mei kang or mei bantup]: detainee with authority over a dormitory inside a center

“Rolling like a barrel” [romeal thung sang]:punishment of rolling on the ground for a certain distance

“Roll like a monkey” [sva damdoung]: punishment of rolling forward head-over-heels for a certain distance

“Twisted electrical wire” [kh'sei oy]:cords of electrical wire twisted together to form a whip

“Welcome” [sva khoum]: slapping of the face of a new detainee by others in his or her dormitory

“Ya ma”: methamphetamine

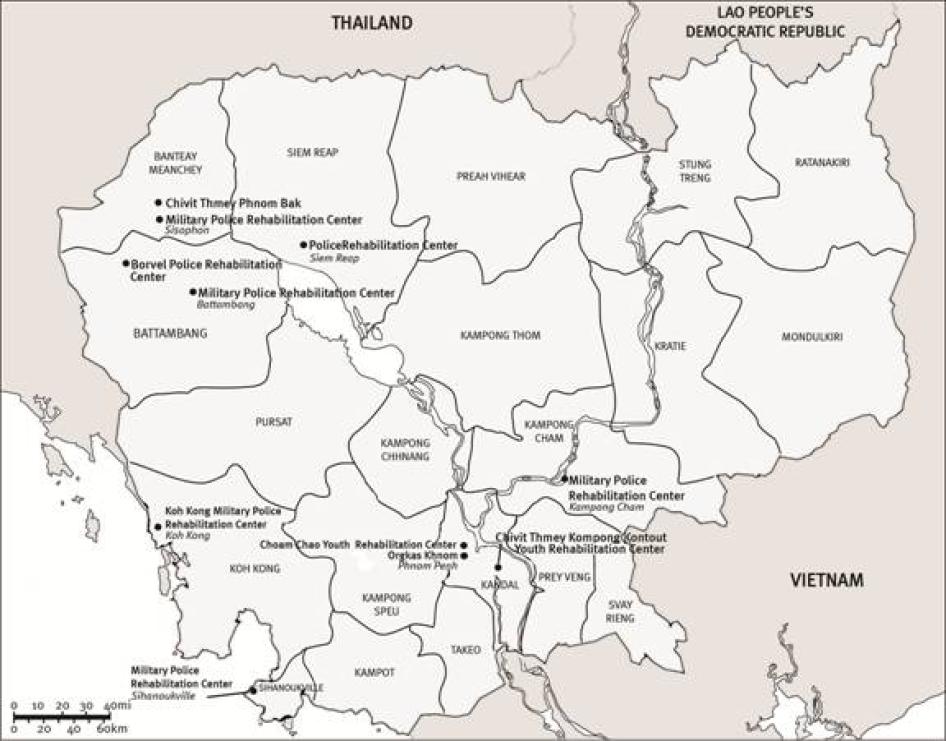

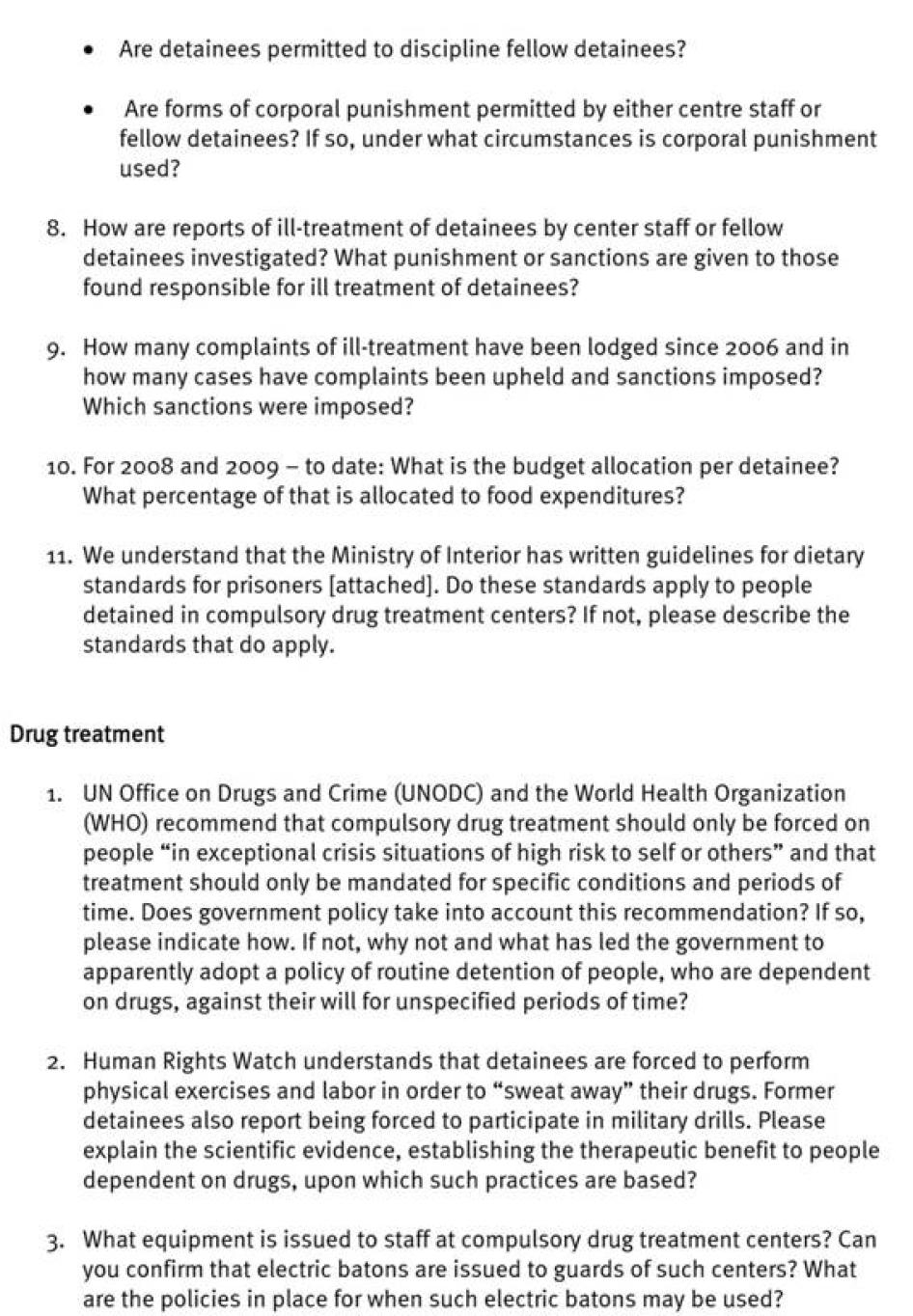

Map of Cambodian Detention Centers

Cambodia’s Government Drug Detention Centers. © 2009 Human Rights Watch

I. Executive Summary

[A staff member] would use the cable to beat people... On each whip the person’s skin would come off and stick on the cable...

—M’noh, age 16, describing whippings he witnessed in the Social Affairs “Youth Rehabilitation Center” in Choam Chao[1]

Cambodians who use drugs confound the notion that drug dependence is a self-inflicted condition that results from a character disorder or moral failing. When Human Rights Watch talked with these people, they were invariably softly spoken and polite. They talked openly and honestly about difficult childhoods (in many cases still underway) living on the streets, or growing up in refugee camps in Thailand. Often young and poorly educated, they spoke of using drugs for extended periods of time. Despite many hardships in their lives, their voices rarely became bitter except when describing their arrest and detention in government drug detention centers. They did not mince words when describing these places. One former detainee, Kakada, was particularly succinct: “I think this is not a rehab center but a torturing center.”[2]

Kakada’s appraisal was borne out by Human Rights Watch’s own research. Many detainees are subjected to sadistic violence, including being shocked with electric batons and whipped with twisted electrical wire. Arduous physical exercises and labor are the mainstays of supposed drug “treatment”. Some detainees are forced to donate their blood. Many suffer symptoms of diseases consistent with nutritional deficiencies. Those detained in such centers include a large number of children under 15, as well as people with mental illnesses. People in such centers are detained in violation of international and Cambodian legal standards.

In Cambodia, “undesirable” people such as the homeless, beggars, people who use drugs, street children and sex workers are often arrested and detained in government centers. This report is an investigation into the treatment of one such “undesirable” group—people who use drugs—by law enforcement officials and staff working at government drug detention centers. While people who use drugs are also sent to general “catch-all” centers, Human Rights Watch believes there are currently 11 centers specifically designated for people who use drugs in Cambodia. The centers are operated by a haphazard collection of government authorities: the military police, civilian police, the Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation (Social Affairs) and Phnom Penh municipal authorities. In 2008, over 2,000 individuals were detained in such centers throughout the country.

A very small number—perhaps 1 or 2 percent of the total—enter these centers voluntarily. Roughly half enter drug detention centers after being arrested by police or unlawfully rounded up by other authorities for drug use or vagrancy. The other half is arrested at the request of their parents or relatives. In such cases the families invariably have to pay for detention despite the fact that Cambodian law requires drug dependency treatment in government facilities to be free.

The process of arrest and subsequent detention appears to follow two broad patterns. In some locations (such as Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh) poor people who use drugs (as well as other groups of “undesirables”) are regularly rounded up by police, Social Affairs staff and others. If they have enough money, or parents or others are willing to pay, they might bribe their way out of police or Social Affairs detention. If not, they will be sent to a drug detention center. In other locations in Cambodia (such as some provincial capitals), poor people who use drugs will be ignored, or else will be arrested, charged, and sent to prison. In these locations, drug detention centers primarily or exclusively detain people whose family is wealthy enough to pay police and/or center staff for arrest and subsequent detention. Such a distinction is not rigorously observed, as police still regularly clear the streets of provincial capitals, while people are sent to centers in Phnom Penh on the request and payment of their parents or relatives.

Whatever the scenario, Cambodians who use drugs are arrested and detained illegally. Police rarely tell people the reasons for arrest, or misrepresent why they are arresting someone. There is no access to legal counsel in police detention or in subsequent detention in the centers. There is no judicial authorization of detention, nor any oversight or review.

Research has shown that drug dependence is not a failure of will or of strength of character but a chronic, relapsing medical condition with a physiological and genetic basis that could affect any human being. People dependent on drugs have the right to access medically appropriate, effective drug dependence treatment, tailored to their individual needs and the nature of their dependence. However, the “treatment” and “rehabilitation” in the centers is ethically unacceptable, scientifically and medically inappropriate, and of miserable quality.

Sweating while exercising or laboring appears to be the most common means to “cure” drug dependence. Center staff often tell detainees that they must work up a sweat to eliminate drugs from the body. In some centers, this regime of physical exercise and laboring is augmented by military drills, group classes on drug issues and supposed vocational training. In many instances, forced labor and vocational training activities appear motivated only by benefits to the center staff, as opposed to the detainees themselves.

If Cambodian authorities think they are reducing drug dependency through the policy of compulsory detention at these centers, they are wrong. There is no evidence that forced physical exercises, forced labor and forced military drills have any therapeutic benefit whatsoever. After a number of months in the centers, individuals are declared “cured” because drugs are no longer physically present in the body. One former detainee, Puth, identified the obvious flaw in the current approach:

I think that success [cessation of drug use] only happens inside the center but they will use drugs after they are out. The majority [of detainees] return to drugs... some are sent three times, four times, five times to the centers.[3]

The existing system of compulsory drug detention centers is not reducing the number of Cambodians who use drugs. NGO workers and health professionals in Cambodia criticized the centers as “not working” and “[merely] being seen to do something.”[4] Indeed, former detainees said that, rather than “rehabilitate” them, their detention undermined the skills, resources and human relationships many had beforehand, and which help integrate people into their community. According to Chrolong, “After I left [the center] everything had finished. I lost my job, my girlfriend left me, [and] then I started using drugs again. I wasn’t using drugs when they arrested me.”[5]

The real motivations for Cambodia’s drug detention centers appear to be a combination of social control, punishment for the perceived moral failure of drug use, and profit. Indeed, people who do not meet the government’s own criteria for drug dependence are often detained. For example, the National Authority for Combating Drugs [NACD] reports that almost 700 individuals were detained for crystal methamphetamine use in government run centers in 2008, although 25 percent were “not dependent” according to the NACD’s own assessment.

Compounding the therapeutic ineffectiveness of detention is the extreme cruelty experienced at the hands—and boots, truncheons and electric batons—of center staff. Sadistic violence, experienced as spontaneous and capricious, is integral to the way in which these centers operate. Human Rights Watch found the practice of torture and inhuman treatment to be widely practiced throughout Cambodia’s drug detention centers.

The overwhelming majority of those interviewed for this report had either experienced the cruel and inhuman treatment described below or seen it first hand. Former detainees report they were shocked with electric batons, whipped with twisted electrical wire, beaten, forced to perform painful physical exercises such as rolling along the ground, and were chained while standing in the sun. Many of these abuses were for minor infringements of center rules, although sometimes not even that pretext was necessary. In addition, Human Rights Watch received reports of detainees being raped by center staff. Others reported they were coerced into donating their blood to avoid being beaten or to secure their release from the centers.

Center staff routinely appoint certain detainees to carry out the majority of the day-to-day control of other detainees and enforce the rules of the center. Extreme physical cruelty by detainees, sometimes on the direct orders of staff, is commonplace inside the centers.

Former detainees complained to Human Rights Watch about the quality and quantity of the food provided to them. They also reported that they were often hungry. The food provided was often rotten or insect-ridden, and appears to have been grossly deficient both in nutritional and caloric content. Detainees reported symptoms of diseases consistent with nutritional deficiencies.

In 2008 just under one quarter of detainees in government drug detention centers were aged 18 or below. Contrary to international law, they are detained alongside adults. Child detainees told us of being beaten, shocked with electric batons and forced to work. Children also said they were coerced into donating their blood.

In practice, the government drug detention centers also function as a convenient means of removing people with apparent mental illnesses from the general community and public view. Human Rights Watch interviewed former detainees who reported appalling physical violence against people with apparent mental illnesses in the centers. There are no services or resources in the centers for managing mental illnesses.

II. Recommendations

To the National Authority for Combating Drugs, the Ministry of National Defense, the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation, and the Phnom Penh Municipality

- Permanently close Cambodia’s drug detention centers and Social Affairs centers where people have been detained in violation of international and Cambodian law

- Release current detainees in Cambodian drug detention centers, as their continued detention cannot be justified on legal or health grounds.

- Ensure a prompt, independent, thorough investigation and legal action (including criminal prosecution) of perpetrators of torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, arbitrary detention and other human rights abuses and criminal acts in police detention and in drug detention centers and Social Affairs centers.

Stop the arbitrary arrest of people who use drugs and other “undesirables” such as homeless people, beggars, street children, sex workers, and mentally ill people. - Establish an independent body to directly receive and investigate complaints of torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and other abuses committed by law enforcement officers and staff at drug detention centers and Social Affairs centers.

- Permit independent legal and human rights organizations to routinely visit police stations to monitor detention conditions and interview detainees; until they are closed, permit independent legal and human rights organizations to routinely visit all drug detention centers and Social Affairs centers.

To the National Assembly of Cambodia

- Remove the provisions in the current (and draft) drugs law allowing civil courts to force people into drug dependency treatment on the request of that person’s spouse, parents, relatives, or a prosecutor.

- Provide that no one can be subject to

detention and compulsory drug treatment except where strictly necessary subject

to the following conditions:

- On the basis of two clinical opinions by qualified healthcare professionals, where a person lacks the capacity to consent themselves, or is in imminent threat of danger to themselves, due to drug dependency;

- Detention shall be no longer than strictly clinically necessary to return someone to a state of autonomy in which they can take decisions regarding their own welfare; In any event any detention shall be subject to a statutorily defined time limit to review for its continued necessity;

- The person who is detained has the right to the best available health care: this means treatment on an individually prescribed plan (reviewed regularly) and the provision of evidence-based treatment (including, where opioid dependent, opioid substitution treatment); no one in detention and subject to compulsory treatment may be given experimental forms of treatment;

- The detainee or their legal representative has a right to challenge the detention decision before an independent body of addiction experts.

- Reform the legal and policy framework for treatment of drug dependence, including the current Law on Control of Drugs and the draft drugs law currently under development. The process should include consultation with and input from human rights experts to advise on human rights compatible measures and safeguards which should form the basis of such reforms.

- Reform the Law on Control of Drugs so that methadone and buprenorphine are available in Cambodia for the purpose of providing opioid substitution treatment for drug dependency.

To the Ministry of Health

- Expand access to voluntary, community-based drug dependency treatment and ensure that such treatment is medically appropriate and comports with international standards.

- Expand access to voluntary, community-based drug dependency treatment for children, and ensure that such services are age-specific, medically appropriate and include components of education.

- Expand access to voluntary, community-based drug dependency treatment which addresses the special needs of women and girls who use drugs.

- Ensure that no unlawful payments are

demanded for voluntary, community-based drug treatment services provided by the

government, which under Cambodia’s national law on drugs are provided

free of charge.

To United Nations agencies

- Request the permanent closure of Cambodian drug detention centers and Social Affairs centers where people have been detained in violation of international and Cambodian law.

- Clearly communicate to the Royal Government of Cambodia that the system of compulsory drug treatment violates international human rights law and Cambodian law and is not supported by scientific evidence, nor international standards on what constitutes effective drug dependence treatment.

- Review all funding, programming and activities directed to assisting Cambodia’s drug detention centers and Social Affairs centers to ensure no funding is supporting policies or programs which violate international human rights law, such as the prohibitions on arbitrary detention, torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

- Actively encourage the Cambodian government to expand voluntary, community-based drug dependency treatment and ensure that such treatment is medically appropriate and comports with international standards.

- Develop a WHO, UNODC, UNICEF and OHCHR position paper establishing principles for the protection and care of people in drug dependence treatment, including the rejection of treatment systems that, as a matter of course, forcibly detain and treat people who use drugs.

- Support and provide capacity-building projects for drug dependence treatment to staff of the Ministry of Health and nongovernmental organizations.

- UNICEF should support the expansion of access

to voluntary, community-based drug dependency treatment for children (under the

Ministry of Health and nongovernmental organizations) and ensure that such

services are age-specific, medically appropriate and include components of

education.

To UN human rights bodies

To the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights Situation in Cambodia

- Clearly communicate to the Royal Government of Cambodia that the system of compulsory drug treatment violates international human rights law and Cambodian law and is not supported by scientific evidence, nor international standards on what constitutes effective drug dependence treatment.

- Recommend the permanent closure of Cambodian drug detention centers and Social Affairs centers where people have been detained in violation of international and Cambodian law.

- Work with the Royal Government of Cambodia to establish an independent body to directly receive and investigate complaints of torture and other abuses in order to combat impunity.

To the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention

- Raise concerns with the Royal Cambodian Government regarding the allegations of arbitrary detention, torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and other abuses committed against people who use drugs (including children) by law enforcement officers and staff of drug detention centers in Cambodia.

- Request an invitation to visit Cambodia to investigate allegations of arbitrary detention, torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and other abuses committed against people who use drugs, by law enforcement officers and staff of drug detention centers in Cambodia.

To the UN Committee and Subcommittee against Torture, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women

- Request further information from the Royal Government of Cambodia in its periodic reports on the detention and treatment of those detained in drug detention centers in Cambodia, including women and children.

- Include in Concluding Observations, follow-up work and/or visits, recommendations on specific measures directed towards ending abuses against people who use drugs by law enforcement officers and staff at drug detention centers and Social Affairs centers, and holding perpetrators accountable.

To bilateral and multilateral donors and NGOs providing assistance to Cambodia on drugs or HIV/AIDS issues in Cambodia

- Publically call for: i) an end to violations that occur in Cambodian drug detention centers, ii) an investigation into the allegations of such violations, and iii) holding to account those responsible for such violations.

- Raise with interlocutors from the Royal Cambodian Government the allegations of violations, including arbitrary detention, torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and the need to investigate them and hold those responsible to account.

- Review any funding, programming and activities which support the operation of Cambodia’s drug detention centers to ensure that no funding is being used to implement policies or programs which violate international human rights law, such as the prohibitions on arbitrary detention, torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

- Support the expansion of voluntary, community-based drug dependency treatment, including appropriate services for women and children.

- Direct support and capacity-building projects for drug dependence treatment to staff at the Ministry of Health and nongovernmental organizations.

III. Methodology

This report is based on information collected during 11 weeks of field research conducted in Cambodia between February and July 2009. Human Rights Watch interviewed 74 key informants. These key informants included 53 people who currently or formerly used drugs and who had been detained in at least one drug detention center; seven people who currently or formerly used drugs but who had not been detained in drug detention centers; and three people who did not identify themselves as drug users, but who had nevertheless been detained in centers because they were homeless people, beggars, or street children.[6] All former detainees had been detained within three years of the date of their interview. Thirteen of the key informants were under the age of 18. Human Rights Watch also interviewed 11 current or former staff members of NGOs and UN agencies who have knowledge and experience regarding the situation of people who use drugs in Cambodia.

Human Rights Watch interviewed former detainees from seven of the 11 current government drug detention centers, including centers run variously by the Municipality of Phnom Penh, the Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation (Social Affairs), the military police, and civilian police. Interviewees include former detainees from six out of the largest seven centers. Interviews were conducted in the provinces of Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, Kampong Cham, Siem Reap, and the capital, Phnom Penh.

Included in the key informants were a small number of former detainees from one Social Affairs center (at Prey Speu near Phnom Penh) not officially listed as a drug treatment center.[7] It appears that people who use drugs (as well as others) have been regularly detained there. Although some people who use drugs reported being detained at a Social Affairs center at Koh Kor (also known as Koh Romdoul) within the period covered by this report, their testimony was not included here as that center is currently inactive. We were unable to identify and meet with former detainees from certain centers in Banteay Meanchey, Koh Kong, Sihanoukville, or Kandal provinces.

All interviewees provided oral informed consent to participate. Interviews were conducted in private and individuals were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions without consequence. Interviews were semi-structured and covered a number of topics related to illicit drug use, arrest and detention. Where the interviewees spoke Khmer, interviews were consecutively interpreted between English and Khmer. The identity of these interviewees has been disguised with randomly-selected pseudonyms and in some cases certain other identifying information has been withheld to protect their privacy and safety.

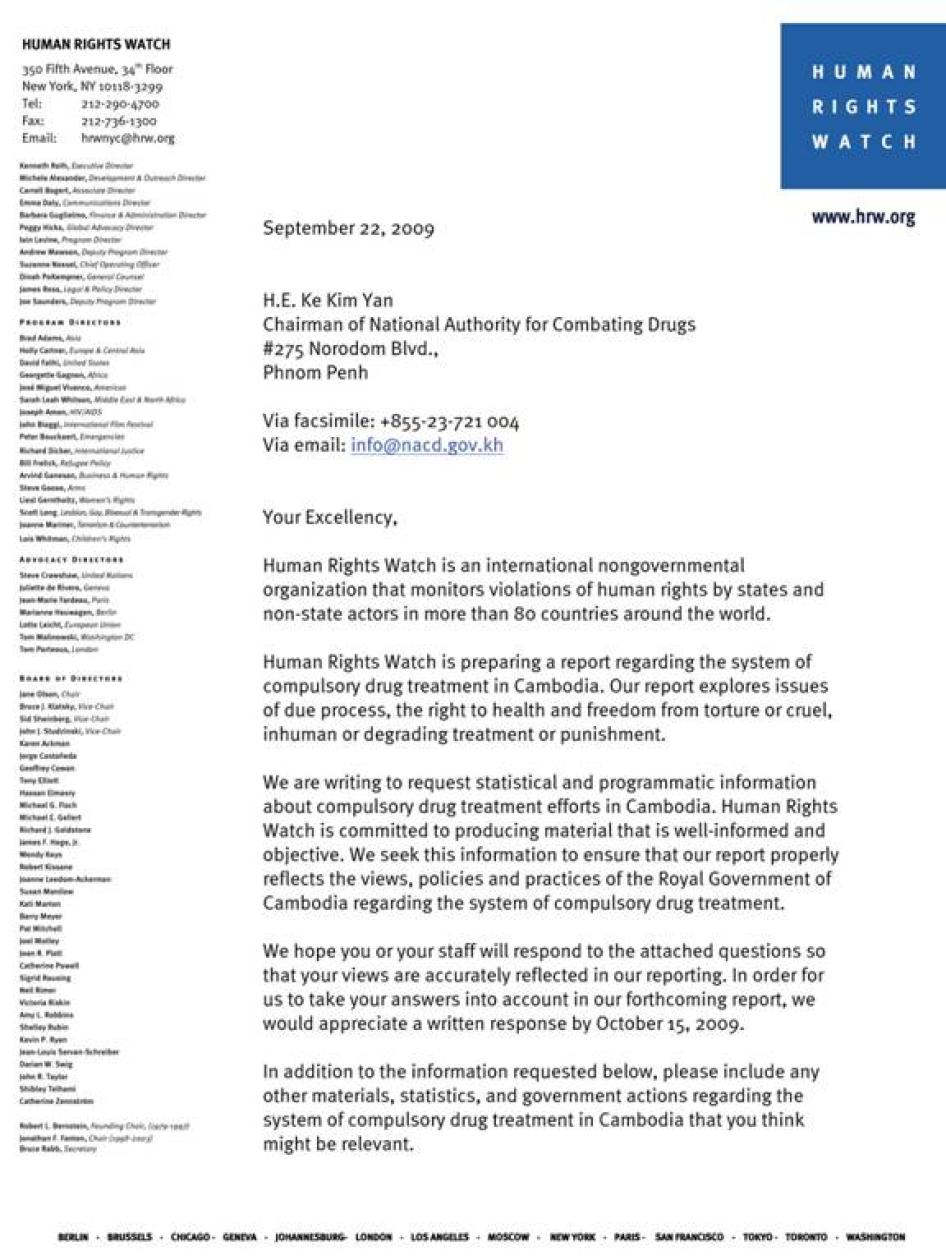

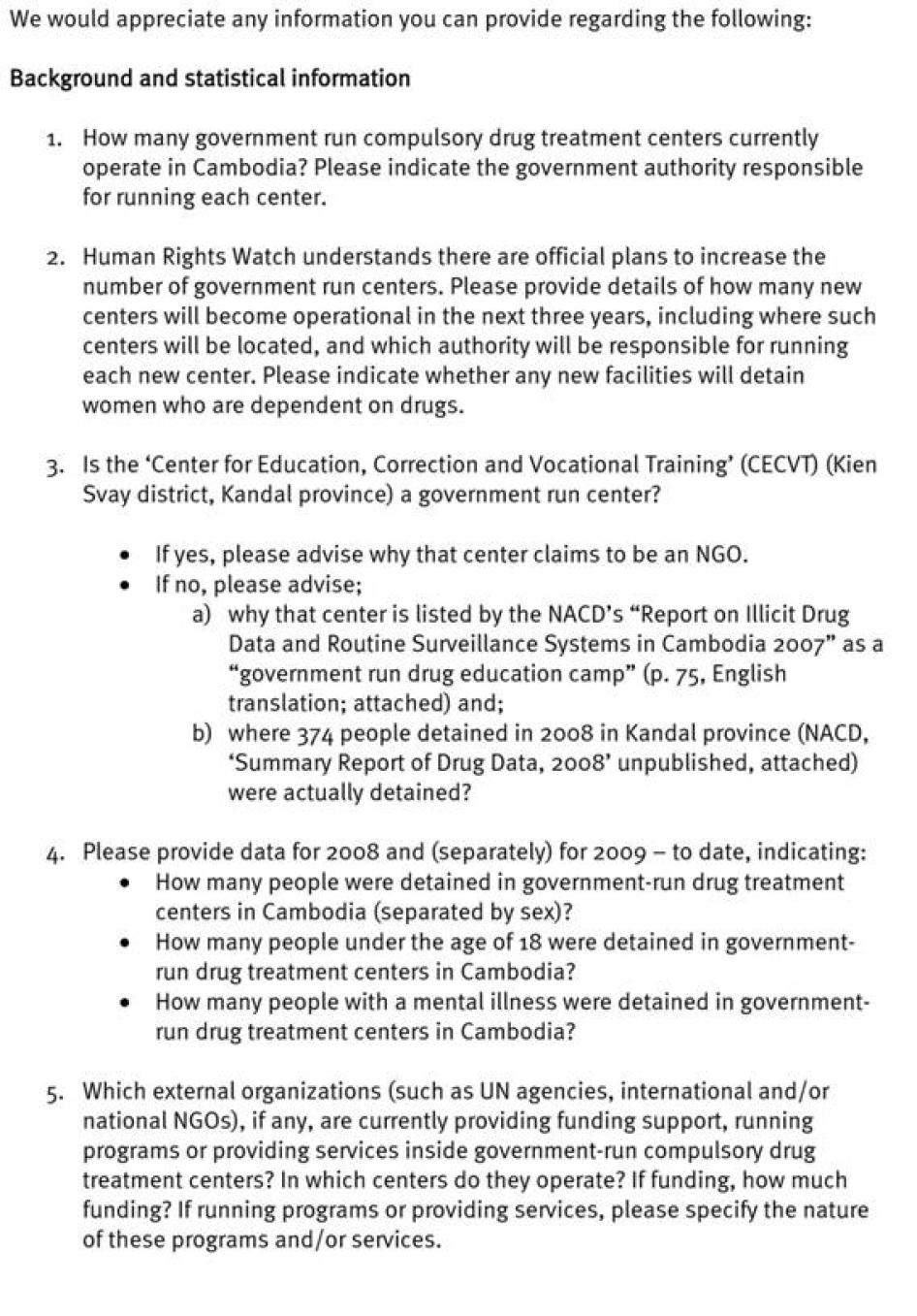

In September 2009, Human Rights Watch wrote to the head of the National Authority for Combating Drugs to request information on Cambodia’s drug detention centers and solicit its response to violations we had documented. This correspondence is attached in Annex 1. As of the beginning on November 2009, Human Rights Watch had received no response to this correspondence.

IV. Background

Drug use in Cambodia

While drugs such as heroin and cannabis were widely used in Cambodia in the 1990’s, the country witnessed a marked increase in ‘ya ma’ (methamphetamine) use in the last decade. Currently, the main illicit substances used in Cambodia appear to be ‘ya ma’ and ‘ice’ (methamphetamine in crystal form). People who inject drugs are most likely to inject heroin. Solvents such as glue are commonly inhaled, especially by street children. Cannabis and, to a much lesser extent, ketamine, are also prevalent. The majority of people who use drugs are between 18 and 25 years old, and few are female. The use of two or more drugs is very common.[8]

Estimates of the absolute number of people who use drugs in Cambodia differ widely. The official government figure for 2008 put the number of people who use drugs at 5,896, a figure very close to the 5,797 for 2007.[9] However, this number is widely considered an underestimation. A 2007 study undertaken by the National HIV/AIDS Program (NCHADS) estimates there to be between 9,100 and 20,100 people who use drugs in Cambodia, of whom approximately 1,100 to 3,000 are people who inject drugs.[10] UNODC has been reported as estimating a population prevalence of drug use of four percent of the entire population, which would signify a figure as high as 500,000 people who use drugs in Cambodia.[11]

Cambodia’s drug detention centers

In 2008, the National Authority for Combating Drugs [NACD] reported that there were 2,382 people detained in government drug detention centers.[12] This figure is a 40 percent increase from the number of people detained in 2007 (1,719).[13] According to the NACD’s data, the majority of individuals (1,483 or 62 percent) were aged between 19 and 25 years. Just 15 individuals (or 0.6 percent) were female. The most commonly reported types of drugs used were methamphetamine (51 percent) and crystal methamphetamine (42 percent).[14] The NACD also reports that just 1 percent of admissions in 2008 were voluntary, with 61 percent via the “family” and 38 percent “judicial”.[15] As discussed below, the category of “judicial” is a misnomer, given that detainees are not detained on the basis of a valid court order or with any judicial oversight. Thus “judicial” means here those who were arrested by the police without the request and/or payment of parents or relatives.

The government data also reveals that in 2008, 563 detainees (or 24 percent) were aged 18 or below. 104 detainees (or 4 percent) were children less than 15 years of age. 116 detainees (or 5 percent) were classified as “street children”.[16]

Cambodia’s government drug detention centers are operated by various government entities: the Military Police of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (under the Ministry of National Defense), the Commissariat-General of the National Police, also known as the civilian or penal police (under the Ministry of the Interior), the Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation (also known as Social Affairs) and the Department of Social Affairs of the Municipality of Phnom Penh.[17]

The NACD‘s “Five year national plan on drug control” (2005-2010), which includes plans to develop Cambodia’s system of drug treatment and rehabilitation, claims that human rights principles have been incorporated in Cambodia’s response to drugs.[18] However, in another document, the NACD offers the following frank description of government drug detention centers in Cambodia:

Military-style camps operated by the government are the primary providers of treatment services for illicit drug users in Cambodia. Most of the facilities provide limited educational and health services and focus almost exclusively on exercise and discipline. Most treatment centers are operated by civilian or military police. A few others are operated by the Ministry of Social Affairs (MoSAVY) or Provincial administrations.[19]

Although some centers have existed for a number of years, the regulatory framework for Cambodia’s detention centers was established in 2006. In October 2006, the Prime Minister issued a Circular on ‘The implementation of education, treatment and rehabilitation measures for drug addicts.’ The Circular authorizes provinces and municipalities in Cambodia, “especially those which have many drug addicts... [to] try to find one location to organize a drug addict treatment and rehabilitation center by cooperating with involved ministries and agencies.”[20] The Circular also calls on the Ministries of Interior, National Defense and Justice (although not the Ministry of Health) to organize facilities “to collect drug addicts in order to provide them treatment and education so that they will become good citizens again in society.”[21]

The government’s own published lists of such centers are inconsistent.[22] By cross-checking various lists, and visiting the physical location of a number of centers, an accurate list of the current government drug detention centers for drug dependence in Cambodia is reproduced below:

Nº |

Name of center |

Province |

Run by |

Capacity |

1 |

Orgkas Khnom [“My Chance”] |

Phnom Penh |

Phnom Penh municipality |

Approx. 200 |

2 |

Choam Chao “Youth Rehabilitation Center” |

Phnom Penh |

Social Affairs |

Approx 100 |

3 |

Military Police Rehabilitation Center |

Battambang |

Military Police |

Approx 100 |

4 |

Borvel Police Rehabilitation Center |

Battambang |

Civilian Police |

Approx 200 |

5 |

Chivit Thmey Phnom Bak |

Banteay Meanchey |

Social Affairs |

Approx 120 |

6 |

Military Police Rehabilitation Center |

Banteay Meanchey |

Military Police |

Approx 200 |

7 |

Police Rehabilitation Center |

Siem Reap |

Civilian Police |

Approx 200 |

8 |

Military Police Rehabilitation Center |

Koh Kong |

Military Police |

Approx 30 |

9 |

Military Police Rehabilitation Center |

Sihanoukville |

Military Police |

Approx 40 |

10 |

Military Police Rehabilitation Center |

Kampong Cham |

Military Police |

Approx 20 |

11 |

Chivit Thmey Kampong Kontout “Youth Rehabilitation Center” |

Kandal |

Social Affairs |

Unknown |

The centers on this list are deemed to be for the purposes of drug treatment and rehabilitation.[23] However, it would be misleading to consider the list above as exhaustive. Drug use is a crime punishable by incarceration and (as discussed below) some people who use drugs are not sent to these centers but instead tried and imprisoned for the crime of drug use. Further, our research suggests that in addition to the centers listed, one Social Affairs center (at Prey Speu near Phnom Penh) regularly detains people who use drugs (as well as other groups of “undesirables” such as homeless people, beggars, street children, sex workers, mentally ill people and so on). At the time of this report, the Social Affairs center at Prey Speu was operational.[24] Cambodia also has a small number of privately run and NGO run drug treatment centers.[25]

There are indications that the number of government drug detention centers in Cambodia will rise in the near future. The 2008 annual report on drug surveillance by the Secretariat General of the NACD requests that:

Any province or city that has yet to establish centers for the treatment of drug users should consider establishing a place to keep [people dependent on drugs] with the aim of enhancing the victims’ well-being and contributing to the maintenance of security, social order and safety in the provinces and cities.[26]

Indeed, a media report in early 2009 noted that “His Excellency Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Interior and [former] Director of National Authority for Combating Drugs Sar Kheng has advised that any province and city that has more than 50 drug users should establish drug user detoxification centers...”[27]During a speech marking the International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking (June 26) in 2009, Prime Minister Hun Sen requested financial contributions to allow the construction a new drug rehabilitation center in Kampong Speu province.[28]

There are indications that international cooperation may play a role in the expansion of Cambodia’s drug detention centers. One likely potential partner is Vietnam. This is despite the fact that Vietnam’s system of compulsory drug treatment has been criticized for having scant regard for medically appropriate drug treatment or the human rights principles that should guide drug dependency treatment.[29] Independent reviews have found that it is not cost effective and that the rate of relapse to drug use for former detainees is around 90 percent.[30]

The 2008 annual report on drug issues by the Secretariat General of the National Authority for Combating Drugs anticipates that the NACD is “prepared to receive Vietnamese delegates to Cambodia in order to discuss the feasibility of [Vietnam] giving Cambodia youth drug detention centers for drug users.”[31] No timeline for this assistance is presented in the report. However, in June 2009, NACD officials visited Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam. According to media reports, the aim of the visit was to discuss how the two countries could “provide each other with regular assistance in drug control, drug detox facilities, and rehabilitation, and in the management of former drug addicts.”[32] When Vietnam’s Deputy Prime Minister visited Cambodia in September 2009, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen reportedly requested assistance in building rehabilitation centers.[33]

Previous reports of abuses in Social Affairs centers

In recent years, there has been considerable criticism of two particular Social Affairs “rehabilitation” centers. Human rights organizations documented and reported serious abuses that took place in the Social Affairs centers at Prey Speu and Koh Kor.[34] Although not officially listed by the government as drug detention centers, actual or former drug users interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported being illegally detained at these centers.

The Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO)’s 2009 submission to the UN Human Rights Council's Universal Periodic Review process provides a succinct overview of the human rights abuses alleged to have been committed in these two centers and the lack of serious government investigation into reports of such abuses:

Conditions at both [Prey Speu and Koh Kor] centers were abysmal – even worse than exist in Cambodian prisons – and included gross overcrowding and lack of adequate food, clean drinking water and medical care. In June 2008, LICADHO gained access to the Koh Kor center, despite efforts to prevent this by staff there, and photographed hungry men, women and children detained in padlocked rooms. They included a four-year-old boy, a nine-month pregnant woman, and a comatose elderly woman who subsequently died inside her locked room.

At Prey Speu center, detainees were routinely subjected to sadistic violence. Guards raped female prisoners and severely beat detainees who tried to escape or complained about conditions, according to former detainees interviewed by LICADHO. At least three detainees, possibly more, were beaten to death by guards at Prey Speu during 2006-2008, and five others reportedly committed suicide, according to LICADHO investigations.

LICADHO complaints to the government in mid-2008 led to the release of detainees at Koh Kor and Prey Speu. However, the Ministry of Social Affairs has rejected calls to permanently close the centers, and LICADHO fears that unlawful detentions may resume at either or both of them at any time. There has been no serious government investigation into abuses at the centers, and no prosecution of perpetrators. Staff at Prey Speu center who have allegedly committed rapes and murders - and whom LICADHO has asked the government to suspend pending a full investigation - continue to work there.[35] [Citations omitted]

Cambodia’s Drugs Law

Cambodia’s Law on the Control of Drugs, adopted in 1996 and amended in 2005, provides that consumption of illegal drugs is a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment from seven days to one month and a possible fine of between 25,000 to 100,000 riel (approximately US$6-$24).[36] The same law allows either a Prosecutor or a court “to acquit such principal of the offense from punishment or to give only a warning to such person” if the person is not addicted to illegal drugs and the offense involved “only a very small quantity.”[37]

The drugs law provides that cost of treatment for drug dependency in a hospital, specialized agency or government clinic “shall be entirely the burden of the State.”[38]

Methadone and buprenorphine are both medicines used in opioid substitution treatment (OST) for people dependent on heroin or other opium derivatives.[39] The current drugs law lists both as controlled substances and neither are currently available in Cambodia (although at the time of writing this report there are plans to commence a pilot methadone program).[40]

The current drugs law provides that a person can be ordered into treatment by a wide variety of mechanisms. The prosecutor may issue an order for a person to attend “any detoxicating establishment” after having summoned a person to attend court when charged with the offense of illegal drug consumption. This provision legally requires the issuance of both an initial summons issued by the court and a treatment order from a prosecutor. If the person complies with this order the court itself will not punish the offender.[41]

When someone has been charged with the offense of illegal drug consumption, a court itself may order the person charged “to undertake an appropriate treatment measure[s] in accordance with his/her health condition.” If the person complies with this treatment order, the court has the authority to issue a warning.[42] Similarly, following sentencing, a person who has been convicted of illegal drug consumption may request “medical treatment in accordance with their respective health conditions” instead of serving a sentence.[43]

A spouse, parents, relatives, or prosecutor may also request a civil court to order someone into drug dependency treatment. In this case, the civil court must be convinced that that person is addicted to illegal drugs and “is known as dangerous for others.”[44]

Even if the law in Cambodia were being used as the basis for the detention of people who use drugs–which it is not, in the vast majority of detentions–Human Rights Watch considers that many of these provisions are overly-broad, with few or no procedural safeguards against abuse of these mechanisms. These mechanisms may also violate human rights standards, as they allow a person to be committed to treatment without his or her consent, disregard whether treatment is in the best interests of the patient, and fail to limit the period of such treatment, provide oversight, or review the treatment order. Many people who use drugs may not actually need treatment, as they are not dependent.

Human Rights Watch is particularly concerned that the provision allowing a spouse, parent, relatives, or prosecutor to request detention of a person who is dependent on drugs is open to abuse by family members or others who are not motivated by the best interests of the drug dependent person, but rather by embarrassment and/or the desire to have their family member out of their lives for some time. The provision is also of concern given that the centers do not provide drug dependence treatment that is informed by scientific evidence nor comports with international standards.

With UN assistance, Cambodia is currently finalizing a new Law on Drug Control. Most existing provisions on measures for treatment are reproduced in a substantially similar form.[45] For example, article 72(1) on “compulsory treatment” replicates current article 95 (allowing civil commitment for treatment of people who use drugs on the request of family members or prosecutor). The draft Law on Drug Control also contains broad powers for a court to compel a person to accept drug treatment, similar to those found in the current drugs law.

Human Rights Watch considers that no one should be subject to detention for compulsory drug treatment except in strictly circumscribed conditions. Key among these conditions are that the detention is not simply for anyone dependent on drugs, but only where qualified healthcare professionals establish that a person lacks the capacity to consent themselves, or is in imminent threat of danger to themselves due to drug dependency. The detention itself should be for no longer than strictly clinically necessary to return the person to a state of autonomy in which they can take decisions regarding their own welfare. In any event any detention should be subject to a statutorily defined time limit to review for its continued necessity. The person subjected to compulsory treatment (or their legal representative) must have a right to challenge the necessity of detention before an independent body of addiction experts. Further, the treatment provided should be a medically appropriate individually prescribed plan, subject to regular review, that comports with international standards. Under no circumstances should anyone subject to detention for compulsory treatment be given experimental forms of treatment.[46]

V. Findings

Human Rights Watch was told of abuses during arrest, such as physical torture by police to force confessions or reveal information. Human Rights Watch was also told that police demand money or sex in return for release from police detention.

Cambodia’s drug detention centers detain people who use drugs, people with a history of drug use (but not currently using drugs) and people who have never used drugs. Detention is not for drug treatment; people who do not meet the NACD’s own criteria for drug dependence are nevertheless detained in drug detention centers.

In detention, former detainees reported they were shocked with electric batons, whipped with twisted electrical wire, beaten, forced to perform painful physical exercises such as rolling along the ground, and were chained while standing in the sun. Former detainees reported rapes by staff in the centers. Staff delegate powers to some detainees to enforce discipline and punish other detainees. As a consequence, extreme physical cruelty by fellow detainees is commonplace inside the centers. Former detainees also reported being coerced into donating their blood.

Former detainees complained to Human Rights Watch about the quality and quantity of the food provided to them. Detainees reported symptoms of diseases consistent with nutritional deficiencies.

Many abuses—including the administration of electrical shocks, beatings, and forced labor—were also reported by children. Children also said they were coerced into donating their blood. Human Rights Watch also interviewed former detainees who reported appalling physical violence against people with mental illnesses in the centers.

Abuses during arrest

The military police arrested me... They beat me, hit me, kicked me while arresting me in a pagoda... After they beat us, they sent us to a detention center in the military police station.

—Tonloap [47]

Reports collected by Human Rights Watch suggest that, from first contact with police to detention in the police station, severe beatings and other forms of violence are common. According to former detainees, police use forms of physical torture, such as the administration of electric shocks or beatings with gun butts, to force people to confess or reveal information.[48]Police regularly extort money from people after arrest. People are frequently arrested without a warrant or reasonable cause, without being informed of the reasons for their arrest, or are lied to about the reasons for their arrest. They have no access to a lawyer during their period in police custody or during the subsequent period of detention in the centers. Police in Cambodia often arrest people who use drugs on the request of parents or other relatives. No protections ensure that family members do not act out of embarrassment and/or a desire to have the family member out of their lives for some time.

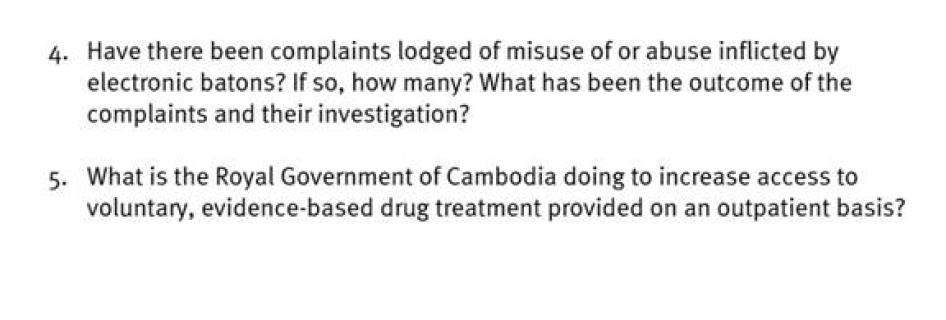

Cambodians who use drugs are arrested because of drug use and vagrancy, but are also frequently arrested in periodic police sweeps of persons considered “undesirable”. Such round-ups have been occurring regularly in Phnom Penh for many years, often in advance of important national holidays or international meetings. The Staff of the Department of Social Affairs of Phnom Penh, often in cooperation with district and municipal police and civilian authorities, conduct these raids. According to media reports, the Deputy Governor of one of Phnom Penh’s districts justified street sweeps in May 2009 by stating that those picked up by the police “make the city dirty. We collected them in order to clean the city.”[49]

|

Social Affairs truck used to round up groups considered “undesirable” to take them to Social Affairs centers around Phnom Penh. © 2008 Licadho |

Treated with contempt, people who use drugs are routinely denied basic rights when arrested. Teap, who is 14, reported being beaten and electrocuted in police custody in order to extract a confession.

I was sleeping inside the pagoda compound in the open air... The police asked me, ‘Did you steal someone’s car mirror?’ I said, ‘No, I didn’t.’ Then they arrested me and beat me. Because they beat me I lied and said I stole the mirror. They shocked me with electrical shocks and beat me with ‘the ox’s penis’ [a police baton]... It was the police who shocked me: a tall colonel with a walkie talkie. At first I told him I didn’t know anything and he said ‘This boy’s so stubborn!’ and grabbed an electric shock baton. Then I told him I had stolen it: actually I hadn’t stolen it, I was just scared... They shocked me once. It left a mark on my arm. I lost consciousness so they poured water on me. I saw him holding a stick with sparkling electricity. It hurt. My body was shaking when I got the shock.[50]

Kronhong, age 18, described being tortured by military police, after smoking ‘ya ma’ with a friend, to extract information about who supplied him with drugs.

They brought us to an interrogation center and started questioning, like ‘Who are the sellers [drug dealers]?’ It was inside the military police station. They questioned me for two hours... I did not tell them who are the buyers then they beat me. They kicked me in the face six times, also on my spine and my ribs. They kicked me till I fell over then they lifted me up and smashed me with an AK47 butt.[51]

Duongchem was not told the reason for his arrest and not provided with access to a lawyer. He describes the beating he received from police and the subsequent confession he was forced to sign.

The police asked if I stole anything. I said, ‘No, I’m just a drug user.’ They said ‘You used drugs, where did you get the money?’... They slapped me with their hands and kicked me in the stomach and my shin with their boots. My skin was bleeding and the skin was torn off. They kicked me in the stomach. They beat me to make me confess that I stole something from the market. Two policemen did this in the police station, in the interrogation room... I did not confess but the police still wrote down [a confession]:... At the police station they asked us to put my thumb print on the report... I just did as I was told to do.[52]

Chrolong reported being arrested without a warrant or reasonable cause by a security guard near Wat Phnom in Phnom Penh.

I was walking at night and I came out from a dancing club. I was sitting with my girlfriend... There was no reason given for our arrest. They said ‘You stroll in the night; strolling at night is not good.’ The security guard [who arrested me] said this... I never saw a lawyer.[53]

Information from former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch suggests that police often misrepresent the purpose of arrest. For example, Russey explained he was taken into police custody on a false pretext and a promise to be released shortly afterwards, although he was subsequently detained in a drug detention center.

At 11 a.m. they come to arrest me, two military police, one skinny and one fat. [One military policeman] said ‘Little kid, you had a fight. Now let me ask you something at my place. Then I’ll let you go.’ However, when he arrested me he sent me [to the center] without releasing me and I had my head shaved... I never saw a lawyer.[54]

Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that some police demand bribes in return for releasing people from police detention. In this way, some people are able to buy their way out of police custody (and subsequent detention in a drug detention center). For example, Toh described how he was released from police custody following his arrest for drug use.

They sent me to the provincial police station. They said we were using drugs: this was true... They called [our] parents. My mother and my friend’s mother shared [the amount]: all together it was $200 for five [people’s release].[55]

Other former detainees told Human Rights Watch how they were unable to buy their freedom. Putrea said that he was sent to the drug detention center because he was unable to pay the extortion money to have him released from police custody. He explained:

[The police] didn’t tell me why I was arrested. I never saw a lawyer... I was not addicted to drugs. The only difficulty I had was I had no place to sleep and no food... My boss didn’t ‘guarantee’ me [pay the extortion amount] so they accused me of stealing.[56]

Tola said that a drug dealer with whom he was arrested was able to pay for her release, while he was unable to pay the extortion money (and was subsequently detained at the Orgkas Khnom center).

A woman was released for $50: the police lent her a mobile phone and she called up a friend... When the person came with the money, the police let her out. I didn’t get released because I had no money.[57]

Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that arrests of people who use drugs often follow payment by parents or relatives to the police to carry out the actual arrest, as well as for the subsequent period of detention. Sokram, 25, explained that his mother paid military police in Sisophon to arrest him.

My parents called the police to arrest me. [My parents] said I am a drug user and I caused trouble to them. The military police arrested me inside the house while I was sleeping, [at] about 10 p.m. at night. I learned beforehand that I would be arrested and sent to the military police center. My mother told me she paid more than US$200 for the arrest. They paid $50 a month for me to be in the center. I never saw a lawyer. [The police] beat me when I struggled and refused to go.[58]

Srolao, age 23, explained that the police arrested him supposedly on suspicion of stealing a motorcycle, but in fact because his parents paid for his arrest. When he arrived at the center, he was told his parents paid 1,500 baht (approximately US$45) for the arrest.[59] Kuhear, 26 years old, reported being arrested by military police when his mother paid them to do so. The police lied to him about the reasons for his arrest and only revealed the real reason once he was in police custody in the drug detention center.

Four military police came to my house. They said they summoned me [to the military police station] to clarify one question of a quarrel in a restaurant, a quarrel I had with my friends... They said if I didn’t agree to follow them, then I would be handcuffed. I just followed them, it was easier. They intimidated me; they said they would beat me and handcuff me if I refused to go. They had no arrest warrant. I never saw a lawyer... They did not tell me anything about drugs at [my] house, only about a dispute. [Later] in the car, they accused me of using drugs. They said, ‘Did you use drugs? Tell me the truth or I will beat you.’ I said I used. Actually, I stopped using drugs three months before I was arrested...[60]

As one NGO staff member with considerable experience working on drug issues in Cambodia explained to Human Rights Watch,

Though I fully understand the concerns of family—because I understand the chaos... drug use ... can [cause] within a family network—this doesn’t mean a person should be sent to a place [of detention] by family members without due process. There needs to be a mechanism that supports family networks that is more in line with the rule of law.[61]

Abuses against women and girls

Currently, there are no detention facilities specifically for women and girls who use drugs in Cambodia. Cambodian government officials have told the media that they plan to build facilities specifically for women.[62] At present, however, women who use drugs are frequently arrested but rarely sent to drug detention centers. As noted, of the 2382 people admitted to government run centers in 2008, just 15 individuals (or 0.6 percent) were female.[63]

Although rarely detained in drug detention centers, women and girls who use drugs are frequently arrested and face detention in centers (such as Social Affairs centers, but not these exclusively) because they are homeless, beggars, sex workers or members of other “undesirable” groups.

Women who use drugs may be forced to secure their release from police custody following arrest via bribery or in exchange for sex. For example, Roka described how she was released following her husband’s bribe of the police.

I went to buy ‘white’ [heroin]. When I bought it and left the house they arrested me... The police said, ‘If you have money, I will let you go. If you don’t have money, I will send you to prison.’ I said, ‘You should talk to my husband at 12 o’clock.’ This happened three days ago. My husband found the money, $10, to pay the police. At five p.m., my husband came back with $10. At seven p.m. they set me free.[64]

Minea, a woman in her mid-20’s who uses drugs, explained how she was raped by two police officers.

[After arrest] the police search my body, they take my money, they also keep my drugs... They know I never have money, they don’t even ask me [for a bribe]... They say, ‘If you don’t have money, why don’t you go for a walk with me? Then I’ll set you free.’ This happened to me once... They [the police] drove me to a guest house.... How can you refuse to give him sex? You must do it. There were two officers, [I had sex with] each one time. After that they let me go home.[65]

Applicable standards

Arbitrary arrest

Cambodia is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which prohibits arbitrary arrest or detention.[66] The prohibition against arbitrary arrest or detention means that deprivation of liberty, even if provided for by law, must be necessary and reasonable, predictable, and proportional to the reasons for arrest.[67]The ICCPR further provides an enforceable right to compensation for victims of unlawful arrest or detention.[68]

In order for an arrest to be reasonable, the evidence at hand would have to satisfy an objective observer that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the suspect has committed a crime.[69] The ICCPR requires an arresting authority to immediately inform detainees of the reasons for their arrest.[70] The ICCPR specifies a defendant's right to be informed of charges, to have legal assistance, and not to incriminate him or herself.[71]

Cambodia’s Criminal Procedure Law provides that a person may be arrested without a warrant during or immediately after the commission of a crime.[72] A person who is remanded in police custody shall be immediately informed of the reasons for such a decision.[73] Unfortunately, the law provides that criminal suspects may meet with a lawyer or another person only after 24 hours have lapsed since arrest–a period of time when mistreatment, rape and extortion often takes place.[74]

Torture, cruel and inhuman treatment and the use of force by law enforcement officials

Police inflict serious abuse on detainees, rising to at least the level of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, and often torture.[75] Police use torture to coerce confessions and testimony from detainees. In evaluating claims of violations of article 7 of the ICCPR, the Human Rights Committee has determined that electric shocks amount to torture where the shocks were used to extract information or confession.[76]Rape in detention also constitutes torture.[77] All ill treatment of detainees violates Cambodia’s obligations under the ICCPR and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.[78]

As a party to the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), Cambodia has binding legal obligations to protect women and girls from sexual and other forms of gender-based violence perpetrated by state agents and private actors alike.[79]

In addition to the binding provisions of international law above, the UN has developed detailed principles and rules regarding the use of force by police, to ensure compliance with the international standards. The UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials expressly limits the use of force by police to situations in which it is “strictly necessary and to the extent required for the performance of their duty.”[80] Similarly, the UN’s Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials states that law enforcement officials, in carrying out their duty, shall, as far as possible, apply nonviolent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms.[81] The Basic Principles establish that, “Governments shall ensure that arbitrary or abusive use of force and firearms by law enforcement officials is punished as a criminal offence under their law.”[82]

Abuses in detention

Arbitrary detention

I was smoking drugs in a park... and I was arrested. [The police] sent me to the Social Affairs Department near Wat Moha Montrey. I spent one day and one night there. They did not tell me anything, they just took me into custody. I didn’t see a lawyer... [The next day] at 4 pm, they took me to Orgkas Khnom. They didn’t even ask me my name. I didn’t dare ask any questions because I was afraid they would beat me.

—Mesa [83]

Cambodia’s drug detention centers often detain people who do not meet the NACD’s own criteria for drug dependence. In addition to people who use drugs, the drug detention centers detain a wide variety of people, such as street children, gamblers, alcoholics and mentally ill people. While the motivation for detaining these people is to keep the streets clear of “undesirables”, in other locations in Cambodia (such as provincial capitals), poorer people who use drugs are more likely to be arrested, charged, and sent to prison, than detained in drug detention centers. In such places, centers hold primarily or exclusively those detainees whose parents or family members buy places in the centers. This is despite the fact that the national drugs law provides that the state shall bear the costs of drug treatment in government facilities. The official length of detention varies from center to center. In practice the length of detention depends on the discretion of center staff, some of who can be bribed to secure release. In sum, the detention of people who use drugs in Cambodia can only be characterized as inherently random and unpredictable.

The manner in which people who use drugs in Cambodia are detained must also be characterized as illegal. Even the flimsy due process requirements under the national drugs law to affect the detention of people who are dependent on drugs are ignored in practice. Whatever the arrangement of their arrest and subsequent detention, detainees bypass the court system. At no stage do detainees have access to legal representation. There are no orders from prosecutors followed by court summons, police charges followed by court-issued treatment orders, or court hearings. No judicial or other independent body authorizes the commencement of detention or reviews the necessity of continuing detention. There is no practical opportunity for detainees to appeal their detention. In this way, people are detained without any due process protections.

Following arrest, people are typically held briefly in police stations, district government offices or the offices of the Provincial Social Affairs department, before being taken to a drug detention center. Where the centers are operated by the military police or the civilian police, the place of subsequent detention may be within the same police compound as the police office where they are taken upon arrest; they are simply registered and then detained in another part of the compound. As one NGO staff member with considerable experience working on drug issues in Cambodia explained:

People can be placed in these centers—they can’t leave. The time they spend there is completely at the discretion of the people running the center. Basically, people are detained with no recourse to the law whatsoever.[84]

Officially, the Social Affairs centers provide rehabilitation services to people who stay there voluntarily. Indeed, under Cambodian law, the Social Affairs “Youth Rehabilitation Center” at Choam Chao is supposed to be an “open” center.[85] M’noh, age 16, was detained there in 2008. He explained the reality of this supposedly “open” center:

If anyone tried to escape, he would be punished... Some people managed to escape, some didn’t. Most who were punished for escaping would be beaten unconscious. Beatings like this happened every day.[86]

A wide variety of people are detained in the centers. For example, Kakada, 28 years old, described his fellow detainees at the “Youth Rehabilitation Center” in Choam Chao:

There are glue sniffers, injecting drug users, gamblers, people who fight each other and have been arrested, alcoholics, ‘ya ma’ smokers, very old people and young kids who are beggars along Monivong [street in Phnom Penh]. Sleeping on the street causes disorder, that’s why they are arrested.[87]

Pok described his fellow detainees in the police-run center in Borvel district, Battambang province:

There were two women and the rest were men. [The women] are karaoke singers but also drug users... There were crazy people who had lost all memory. There were two of them. There were three or four elderly people... They said that these adults will stay there for the rest of their lives. There were also two or three children, about 15 or 16. They were there because they did not listen to their parents and used ‘ya ma’.... Some [detainees] are ‘ya ma’ smokers, [other detainees are] people who use domestic violence in families... People who are alcoholics or domestic violence [perpetrators] get freed one or two months later.[88]

The diverse scope of detainees is not limited to Social Affairs centers. Makara reported that in the Orgkas Khnom center, the main drug detention center in Phnom Penh, “There’s also those who are street kids, injecting drug users, those with mental health problems.”[89] Momeh, a disabled 15-year-old child living on the street but who had never used drugs, was detained at the civilian police center in Siem Reap.[90] Trach, a former detainee of the same center in Siem Reap, explained:

There were ‘ya ma’-, ‘ice’-, ‘k’ [ketamine], glue- [using] people, marijuana people, methamphetamine users... There are people with mental health problems, crazy people, recyclers, homeless people, alcoholics who beat their children when they drink, homeless kids.”[91]

Authorities are aware that actual drug dependence is not a prerequisite for entry into government drug detention centers. Some centers force detainees to undergo an assessment of drug use upon admission to the center; most centers do not. According to a draft report of a joint report of the centers conducted by WHO and the Cambodian government, assessment tools such as the “Severity of Dependence Scale” [SDS] and urine testing “are not used as part of any exclusion criteria.”[92]

It is unlikely that the NACD’s “Severity of Dependence Scale” [SDS] is reliable even when it is used, given that the assessment is administered to new arrivals by staff with little or no health care training, let alone clinical training in drug dependence issues.[93] Regardless, people who do not meet the NACD’s own criteria for drug dependence are detained for supposed “treatment” and “rehabilitation”. The NACD reports that almost 700 individuals were detained for crystal methamphetamine use in government run centers in 2008, although 25 percent of these individuals were “not dependent”.[94]

A number of former detainees, including those who frankly discussed their own drug use, told Human Rights Watch that they were not using drugs during the stage of life when they were arrested. For example, Svay said that he was detained at the Orgkas Khnom center for three months despite the fact that his urine test on admission did not reveal any prior drug use. He explained: “The doctor of the center told me, ‘You are free from any drugs... They arrest both users and non-drug users’.” [95]

In some provincial towns in Cambodia, former detainees believed that whether someone is prosecuted criminally or detained in drug detention centers depends on family wealth. In these parts of Cambodia, people whose families cannot buy a spot in drug detention centers are sent to prison, whereas those with money can bypass prison for drug detention centers. The centers hold primarily or exclusively those detainees whose parents pay the centers to detain them. Detention costs between US$50 and $200 per month, an amount usually paid by family members directly to the center.[96] This practice is contrary to the Cambodian drugs law, which provides that cost of treatment for drug dependency “shall be entirely the burden of the State.”[97]

Toh was imprisoned in 2009 for the crime of illegal drug use, although he had never been detained in the drug detention center of the town in eastern Cambodia in which he lives.

There is a rehab center inside the military police station... I don’t know why they didn’t send me there... They did not tell me about it. They said ‘You are guilty so you must go to jail.’ The police did not ask if I wanted to go to the rehab center. No one from [this poor neighborhood] has been to the military police [rehabilitation] center... There are a lot of people who use drugs in this community: no-one has ever gone to the rehab center, just straight into prison. The military police center is only for the rich families.[98]

Chab, a former drug user from the same community, agreed with this point: “The practice of law has two ways: the [rich] parents complain and the kids are sent to the military police while if the police arrest you [without money], you are sent to jail.”[99]

According to former detainees, authorities running these centers appear to go to some effort to hide the fact that they only detain people where there is a financial incentive to do so. Pok is someone who uses drugs in a provincial town with a drug detention center run by the military police. He regularly sniffs glue, but “stopped using ‘ya ma’ because it was too expensive.” He was clear about why he is not normally detained in the center in the town where he lives and why he was recently detained for a (comparatively) short period:

They arrest only the kids who have parents who can afford [to pay for detention]. I think they only arrested us [glue sniffers] to ‘fill in’ the population in the center when the high-ranking officials visit the center. In the center [before we were arrested], there were ‘ya ma’ smokers but no glue sniffers, that’s why they arrested us... This was for those who come to visit, like [the Prime Minister’s wife] Bun Rany. She came to visit when I was there... She gave donations and supported the center so we had enough food to eat. I was released after 15 days.[100]

The official periods of detention vary from center to center--in some places it is three months, in others it is six months to a year. In practice, the actual length of detention is at the discretion of center staff. Tonloap described how his mother’s payment to the military police center in Sisophon secured his release after a two-week period of detention.

[The military police] said ‘...You know, when your parents come to ‘guarantee’ or ‘sponsor’ you, you will be released.’ [To] me, this meant paying money. An official said this... He said this to everybody. I stayed about two weeks. Actually, they should have released me the same day but my mother did not have the right amount. They asked for 150,000 riel [approximately US$ 36] but she had 100,000 riel [approximately US$ 24] .... She paid this to the military policeman who is a commander...[101]

Ill treatment

They chained [the detainees] at the ankle and attached it to the flagpole in the sunlight in the middle of the day. I saw it two or three times... I saw someone chained in their underwear: this is punishment for running away.

—Trach [102]

Sadistic violence, experienced as spontaneous and capricious, is integral to the way in which drug detention centers operate. The overwhelming majority of those interviewed for this report had either experienced the cruel and inhuman treatment described below or seen it first hand. Cruel and inhuman treatment was reported in all centers covered by this report. Sometimes abuses occurred as apparent punishment for breaking internal regulations of the centers, such as prohibitions on smoking, quarrelling with other detainees and escaping. However, cruel and inhuman treatment is often meted out without explanation or ostensible justification.

Thouren described being shocked with an electric baton by staff on a number of occasions, such as when he was caught smoking inside the Orgkas Khnom center.

On one occasion, I got shocked by a [electric] baton. It made me faint for a minute. It was the staff [who shocked me]. They said ‘You know you aren’t allowed to smoke.’ It’s like a burning sensation, real pain, you are shaking. It made me fall down to the ground.... I’ve been shocked three or four times. You get it for smoking, arguing, fighting. They have a couple of batons they leave on a wall charging.[103]

Tola described electrical shocks being administered to punish his fellow detainees in the Orgkas Khnom center after an unsuccessful escape attempt. After being recaptured,

[The guards] did not shock [the escapees] immediately. The next morning, they asked ‘Who planned this?’ Then they started to find out who was the ringleader. When they found two ringleaders they started to shock them. They brought the ringleaders to the room, questioned them, then shocked them. I did not see this, but when the men came back to the room I asked what happened to them. [One man] showed me a big wound on his abdomen. He said it was from being shocked... He said he fell after he got shocked on the floor and felt exhausted... The skin looked like it was scalded, it was red and blistered.[104]

Kronhong related being given an electric shock in the center run by the civilian police in Siem Reap. He was punished by being electrocuted for having run away from the center on a previous occasion.

They [re-]arrested me and shocked me... They dare not shock me here [in town, when I was re-arrested] because they are afraid the tourists can see... It was a policeman [who shocked me]. He shocked me in front of my room. First they beat me, then they shocked me and I lost consciousness and they poured water on me and they pushed me into my room. They punched me on the head until I had bumps. When they shock [you], you lose energy and you can’t walk. You feel dizzy and you lose energy. ‘This is because you ran away,’ the policeman said.[105]

In addition to administering electric shocks, staff also use whips made out of cords of electrical wire twisted together. Kakada, 28, tells of being whipped with electrical wire in the Social Affairs “Youth Rehabilitation Center” in Choam Chao:

The guard beat me with a whip of eight twists of electrical wire. He asked me to kneel down and cover my genitals.... Then he started to whip me on my back with twisted electrical wire. It was about my wrist’s size. He beat me many times, about 10 times. I was in such pain. Sometimes I cry alone, after the beating, because it was so painful. I did not commit any mistake: why did they beat me like this? After whipping, they slapped me in the face. My mouth was bleeding, my back was bleeding...[106]

Another former detainee M’noh, 16 years old, described witnessing whippings with electrical wire in the Social Affairs center in Choam Chao:

[The staff member] would use the cable to beat people. He had three kinds of cable, made from peeling off the plastic from an electrical wire. One cable was the size of a little finger, one is the size of a thumb and one is the size of a toe. He would ask which you prefer. On each whip the skin would come off and stick on the cable.[107]

Staff also beat detainees with other instruments at hand. Thouren was beaten for smoking a cigarette in the Orgkas Khnom center:

They got the water hose, doubled it in half, and beat me with it. They do it in the back of the center so no one can see. The only thing the kids can hear is your yelling. They beat me about 10 times, on my back. It was like a hose that you water your car with. They made me take my shirt off. It was the guards who did this: three [were] standing and watching, laughing, and one... did the beating.[108]

Kuhear described being beaten by a military police trainer because the staff member was drunk: “He had a stick from a branch of a tree. He entered the room and beat us. He beat me, he beat us all. I recognized he was drunk because of his reddened face.”[109] Vicheaka described a beating he witnessed in the Social Affairs center in Prey Speu:

I saw the guards beat people up. I saw them beat those who had been rearrested after they had escaped. The sticks were about as thick as my arm. I saw them break one man’s leg. I saw the guard lift the leg up--it was broken.[110]

Detainees are also raped in the centers. One former male detainee, Kronhong, age 18, reported being forced to perform oral sex on the commander of the military police center in which he was detained:

Because I was a newcomer I had to do massage for all the others. The first week I arrived I never got a good sleep because I had to give massages. Sometimes I had to give massages to the military police and sometimes the commander... He asked me to press his hands, his feet, to step on him, to pound him a long time, to pull his hair, until he fell asleep. This was... the big director [of the center]. After him, I had to do massage for his subordinates too... You know, the massages were both normal and sexual... Some massages I had to give were sexual... If I did not do this, he would beat me. The commander asked me to ‘eat ice cream’ [perform oral sex]. I refused and he slapped me... Performing oral sex happened many times... how could I refuse?[111]

The Cambodian human rights organization LICADHO has documented serious human rights abuses, including gang rapes by staff, which allegedly took place in the Social Affairs center at Prey Speu.[112] Former detainees from Prey Speu interviewed by Human Rights Watch corroborated these reports. Trabek, a drug user who had been detained at Prey Speu, reported witnessing gang rapes by center staff on numerous occasions:

I saw this with my eyes... They got the girl out from the room. She was a girl who could not speak... They brought her to the classroom: no-one sleeps there. They brought the girl [to the room], unlocked the room, and locked her in. They raped her... I saw three men... it’s very difficult and shameful to describe. The woman screamed out all the time and there was a big struggle inside... They are staff working in the center [who raped her]... ‘Normal’ women also got raped. The guards use a pretext to get the women out of the room, like they made a mistake. Sometimes they raped the same women five days consecutively because there were no new arrivals. Sometimes they were sex workers, sometimes not. They raped a mute woman about five or six times. I saw this with my own eyes. Other times I heard her scream.... I just heard the way [she] tried to make a sound: the voice was stranger than usual. The room was just next door. It was always the same three guards [who raped women], sometimes there were others.[113]

Lolok, a homeless woman who was detained in Prey Speu, reported:

You know, beautiful women and nice women were taken away to be raped... After they were taken away, those girls disappeared. They were about 19, 20 years old. I saw two women taken away from my room... One guard asked [another guard], ‘Hey, what happened to the beautiful girl last night? How did you do that?’ [The second guard replied] ‘Before I released her I ate fully [slang for having sex].’[114]

Detainees are also subjected to painful physical punishments. One common form of physical punishment is the punishment of “rolling like a barrel”, i.e. making detainees roll on the ground over a certain distance. The hardness and sharpness of the stones and rocks causes intense physical pain to the detainees. This suffering is exacerbated by often having to first remove some items of clothing. Sao demonstrated the punishment of “rolling like a barrel” to Human Rights Watch by rolling a water bottle over the interview table, explaining:

After beating, they order those [being] punished to “roll like a barrel” on the small stones. You have to roll about 50 meters and then back again... It is not smooth ground but bumpy with many stones. The ground would cause you pain to even walk on it without shoes. [After this punishment] the body would be cut, grazed. It was the commander and guards that did this [ordered this].[115]

Atith described being punished by having to “roll like a barrel” and perform other physical exercises, and then being beaten and whipped, in the Orgkas Khnom center.