"Every Morning They Beat Me"

Police Abuses in Burundi

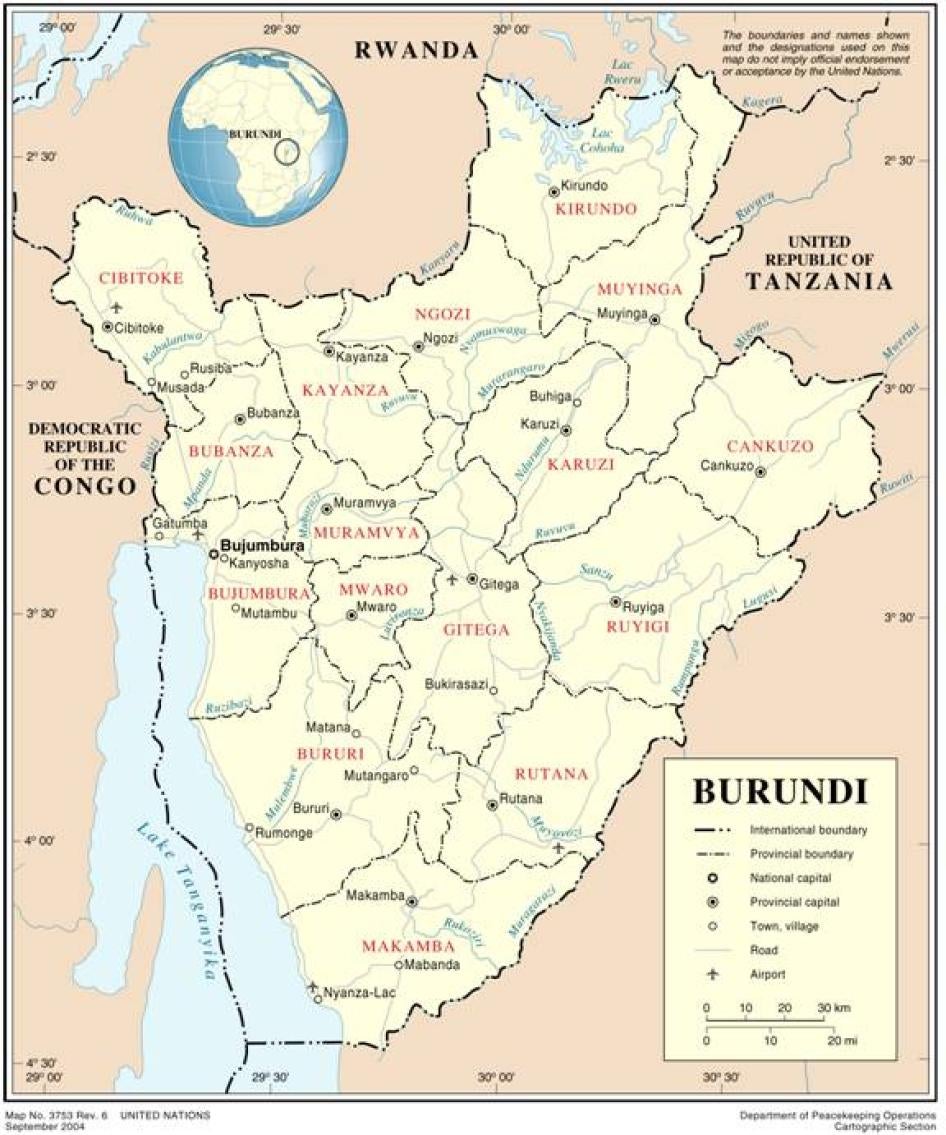

Map of Burundi

I. Summary

In October 2007 officers of the Burundian national police (Police Nationale du Burundi, PNB) illegally detained at least 22 persons in Muramvya province, most for periods of a few days but some for up to three weeks. Security police beat detainees with clubs and batons at a temporary police post established at a health center. At least two men were subjected to mock executions.

Additionally, members of the same police unit subjected residents to public beatings. In four cases reported to Human Rights Watch, this was in response to residents' questioning police conduct. In another case, that of a police officer, it came after he spoke out about torture.

After Burundian human rights monitors reported the abuses, local officials intervened to limit police excesses, freeing some detainees immediately and transferring others to an official jail from where they were subsequently released. Not a single detainee was charged with a criminal offence. Shortly afterwards the police unit responsible was transferred back to the capital, Bujumbura.

Subsequent action to identify and investigate the perpetrators of human rights violations has been slow and inadequate. A police inquiry into the police misconduct was initiated only several weeks after the events and was subsequently abandoned, with no disciplinary action taken against any officer. The officer in command of the unit has since been promoted. Three victims submitted criminal complaints to the Muramvya Prosecutor in late October, but for over a month, no action was taken to investigate the complaints. Judicial investigations against three police officers were initiated only after an international NGO offered legal support by preparing collective complaints on behalf of 13 victims. Despite the gravity of the charges against them, those officers have remained in service and in direct contact with the population while the investigations are carried out. The authorities' reluctance to take action against the perpetrators is consistent with a wider failure of the authorities to hold the perpetrators of human rights abuses accountable, and points to the continuing challenge of impunity in Burundi.

The Burundian government must take immediate steps to end the climate of impunity that allows police officers to act outside the law. Human Rights Watch is calling on the authorities to bring police officers alleged to be responsible for human rights abuses in Muramvya promptly to justice. In addition, the authorities should ensure that effective procedures are put in place to combat ill-discipline and that all officers are given adequate training, including in human rights standards.

Formally established in 2004, the Burundian police force is made up of officers from the former government police, former government soldiers, and combatants from the several armed groups that waged war against the government for more than a decade. The integration of demobilized combatants has caused the number of police to swell from 2,300 in 2000 to somewhere between 15,000 and 20,000 officers in 2007. Many officers have received little or no training and some fail to abide by, far less enforce, the law. Police misconduct is an issue of significant concern to civil society.

The current government was democratically elected in 2005, after the majority of rebel groups agreed to a peace deal that included the integration of their members into the government, the army, and the police. In July 2007, the Forces Liberation Nationale (FNL), the last remaining armed group in opposition, withdrew fromtalks with the government and started a new round of recruiting, while also mounting sporadic attacks on government troops. Their withdrawal coincided with an increase in violent crime, some of it attributed to FNL members. The widespread possession of firearms by civilians is apparently contributing to both the number and the violence of crimes.

The government has relied on the police, including three Rapid Mobile Intervention Groups (Groupements mobiles d'intervention rapide, GMIR), to combat crime, to search for unregistered firearms, and to limit attempts by the FNL to recruit new members and to collect funds and other kinds of support from sympathizers.

While the national police is conducting training programs intended to improve the conduct of police officers and to increase their effectiveness in enforcing the law, progress towards building a well-trained, professional force has been slow. Police training is necessary, but must be complemented by simultaneous measures holding officers accountable for abuses.

Methodology

This report is based on over 65 interviews, including 5 group interviews involving between two and five people, conducted by a Human Rights Watch researcher in Bujumbura and MuramvyaProvince between October 2007 and March 2008. Most of the information on abuses was provided by victims themselves, some of them referred to Human Rights Watch by other non-governmental organizations, some of them identified by other victims, and some located by the researcher in jails in Muramvya. Most of these interviews were conducted in Kirundi with the help of an interpreter and most were done in small groups.

The researcher also interviewed police officers, other government officials, representatives of local and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), United Nations (UN) officials, representatives of international donors and Burundian jurists.[1] A number of interviews in Muramvya province were conducted jointly with representatives of either the Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detaineed Persons (Association pour la Protection des Droits Humains et des Personnes Detenus, APRODH), a Burundian non-governmental organization, or with representatives of the Human Rights and Justice Division of the United Nations Integrated Office in Burundi (BINUB).

For reasons of security, the names of some persons interviewed are omitted from the citations.

II. Recommendations

To the Government of Burundi

- Take disciplinary action against officers who breach their obligations and prosecute those alleged to have committed criminal offences, including such human rights violations as torture, ill-treatment, and unlawful detention.

- Ensure that prosecutions of police officers who have been charged with crimes in Muramvya are carried out promptly, fairly, and in accordance with international trial standards.

- Ensure that all police officers comply with human rights standards relating to police functions (including those set out in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the African Charter on Peoples and Human Rights, and the Convention against Torture), and abide by Burundian laws that reflect these standards (including Article 146 of the Burundian Criminal Code, and the 2004 law on the creation, organization, missions, composition, and operation of the National Police).

- Ensure that all police officers receive appropriate and sufficient training to understand their responsibilities to respect human rights as defined by the international conventions to which Burundi is a party and to prevent violations of these rights.

- Establish an official system to record and respond to complaints of abusive conduct and to track disciplinary or criminal action taken against police officers.

- Ensure prompt passage of a new criminal code prohibiting and punishing torture and inhuman and degrading treatment.

- Ensure prompt passage of a new criminal procedure code reforming the system of pre-trial detention so that Burundian law complies with international human rights standards.

To Donor Partners

- Press the Burundian government to fully investigate and sanction all abuses committed by police officers.

- In all assistance programs directed at the Burundian police, include training on human rights with a particular focus on enforcement of the prohibitions of torture and the excessive use of force. Follow through in the establishment of a proposed police working group as part of the Partners' Coordination Group (Groupe de Coordination des Partenaires, GCP) to ensure that aid to the police is directed toward initiatives that promote human rights.

- Provide support for the Inspectorate of National Police in its efforts to gather data and track complaints against police officers.

To the UN Peacebuilding Fund

- Closely monitor the use of funds disbursed to the police by the United Nations Peace Building Fund in order to ensure that they are used in a manner consistent with the protection and promotion of human rights.

III. Events in Rutegama Commune

On October 3, 2007, the Commissioner General of the Internal Security Police (Police de la Sécurité Interior, PSI) sent approximately 100 officers from the 3rd Rapid Mobile Intervention Group (Groupements mobiles d'intervention rapide, GMIR to Muramvya province in central Burundi. Ordinarily based in the capital Bujumbura, the GMIR is a specialized reserve that is supposed to provide rapid response to emergencies across the country. At the time of the human rights abuses described in this report, GMIR groups operated under the authority of the PSI.[2]According to police, the deployment was a response to an alarmingly high incidence of crime, including the theft of livestock and crops, as well as to recruitment and propaganda by the opposition National Liberation Forces (Forces de liberation nationale, FNL), which in July 2007 withdrew from talks with the government on the implementation of a ceasefire agreed in September 2006.[3]

The GMIR were deployed in several communes, including Rutegama, where they set up a post in the Kaniga health center several kilometers from the town center. Throughout October, with the cooperation of a local PSI police chief, they engaged in a heavy-handed policing operation that involved numerous breaches of Burundian law and the violation of international human rights standards. According to residents interviewed by a Human Rights Watch researcher, the police behavior was brutal and inspired fear. According to one victim, "Everyone in Rutegama is afraid. When people see the truck from Kaniga coming, they flee."[4]An officer of the GMIR police told the Human Rights Watch researcher that the policing strategy was deliberately intended to intimidate local people.[5]

A Campaign of Raids and Arrests

Starting on October 8, GMIR officers under Commander Désiré Uwamahoro began carrying out searches and making arrests in Rutegama and neighboring communes. Although officers had appropriate warrants from the Muramvya prosecutor for most of these searches, they carried out many of them at night and without the presence of a judicial police officer, in violation of the Burundian code of criminal procedure.[6] In addition, officers beat and otherwise ill-treated arrested persons, including businessmen, teachers, farmers, a demobilized combatant and a chef de colline, a local official responsible for governing a small administrative unit. Many of the victims told the Human Rights Watch researcher that police officers accused them of FNL membership, which is not a crime in Burundi,[7]while others said they were accused of illegally possessing arms.[8]

One of the first men arrested by the GMIR described how his family was awakened at about 2 a.m., when everyone was sleeping:

I heard someone knocking on the door, saying, "Open the door." I was very scared. My family was asking, "Is it bandits?" I got up and said, "Who is it?" They said, "We're the police." My wife asked why they were there. They kept knocking and saying, "Open up." They broke down the door, came in, and said, "Put your hands up." I did so. There were about 50 of them, with guns and grenade launchers.

When they approached me, they told me to get all the guns that I had in the house. I said I didn't have any weapons. They started to slap me. They searched through the house, but didn't find anything. They approached my wife, who was naked in bed. They slapped her and told her to find the weapons. She said she had never seen weapons in the house. They handcuffed me and made me leave the house, saying I had to show where I had hidden the weapons and that I would show them after I was given a good beating. [9]

A police officer stationed at the Kaniga health center, along with several victims, told a Human Rights Watch researcher that detainees were designated for arrest "arbitrarily" by the local security police chief, Nestor Niyokuri, and by the Rutegama communal administrator, Josias Ndikumagenge.[10] The GMIR unit took the detainees back to their post at the health center, a building consisting of one large room and several small rooms of about two by three meters each. As many as ten detainees were held in each of these small rooms.[11]Human Rights Watch identified 22 detainees, but according to one GMIR officer who was present, as many as 50 persons may have been detained at the health center throughout the course of the month.[12]

By detaining persons for periods of time ranging from several days to more than three weeks, GMIR officers violated Burundian law which requires officers from all branches of the Internal Security Police to deliver detainees immediately after their arrest to the Judicial Police (Police Judiciaire, PJ).[13]GMIR officers also held the detainees at the health center, not at an official place of detention.[14]There was a jail at Rutegama center, to which any suspects should have been transferred immediately after their arrest.

GMIR officers interrogated the detainees, a further violation of Burundian law.[15] Investigating crimes is a function of the Judicial Police, who question suspects and provide evidence to the prosecutor (Ministère Public).[16] Many victims assumed a person taking notes during their interrogation was a judicial police officer (Officier de la Police Judiciaire, OPJ), but an officer present at Kaniga, as well as the commissioner general of the PSI who ordered the deployment, told the Human Rights Watch researcher that no judicial police officers were present.[17]

Interrogation, Torture and Ill-Treatment

During interrogations GMIR officers tortured, beat, and intimidated detainees to coerce them into giving information. All 11 former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that they had been beaten by police officers. Four said they were also subject to mock executions or death threats. When asked about the treatment of other detainees, one victim said, "Everyone at Kaniga was beaten… every time the police walked passed a detainee, they would hit them."[18]

According to one man, an officer whom he presumed to be a judicial police officer arrested him on October 8 and took him to the health center, where he was held overnight.

He asked me if I was a member of the FNL. I said that I used to be, but that I haven't been a member for a long time. The OPJ wrote a statement and made me sign it, saying I used to be a member of the FNL but that I no longer was involved.

The OPJ then beat me with a wood baton and a club. I was beaten on my hands, face, buttocks, backs of my legs, and my back. I still have problems walking and I have scars on my legs. When I was freed, they told me to quit the FNL and not to help the FNL when they ask for help.[19]

Another person arrested on October 13 recounted:

They put rocks in our mouths while beating us… They have a system. Five or six police take you and lift you 50 centimeters off the ground. They hold you by the arms, legs, and head, and others beat you. They did this to me. Everyone had trouble sitting because we were all beaten on the buttocks. I received more than 50 baton blows in the buttocks… I eventually lost count.[20]

Two other victims showed a Human Rights Watch researcher scars on their backs and stomachs that they said had resulted from the beatings two weeks previously. Another man said that he had urinated blood for days after being beaten.[21]

One of the first men arrested on October 8, another who assumed that judicial police officers were involved, also described torture and ill-treatment, including being subjected to death threats:

When we arrived at Kaniga, they made me lay down on my belly in a puddle in the corridor. A judicial police officer … came and called over two other police. The three of them beat me seriously, with batons, all over my body. I had serious injuries afterwards, and could not sit down for two weeks. They turned me over and beat me on the stomach, saying I should admit I had weapons.

One of the police put a pistol to my head, and another started digging a hole in the field right outside. They were trying to intimidate me, to terrorize me. I said, "Do what you want, I have nothing to say to you other than what I've already said." Then they accused me of being a member of the FNL, and I denied it. They continued beating me to try to get me to admit it. When they got tired of beating me, I fell asleep there in the corridor. Every morning for the next few days, they beat me.[22]

Two men told the Human Rights Watch researcher that in addition to being beaten, they were also subjected to mock execution. One man said:

After beating me, the police took a pistol and said they were going to kill me. I was lying on the ground. A police officer shot at the ground next to my ear.[23]

Another recounted:

They said I should confess to having a weapon and being a member of the FNL… They beat me with a club and a baton. They threatened to shoot me. I was sitting in a chair and they shot so that the bullet went right past my head and into the ground.[24]

Burundi is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,[25] the African Charter on Human and People's Rights[26] and the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), all of which prohibit torture. Under CAT, torture is defined as "any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person" with the consent or acquiescence of a public official in order to elicit a confession or information, or for purposes of punishment or intimidation.[27] Systematic beatings, sometimes on a daily basis for several days and mock executions fall within the scope of that definition.

Paying for freedom

Some persons who had been detained for periods ranging from hours to days were released if they were willing and able to pay bribes to police officers. As one recounted:

One day they asked me if I wanted to go home. They suggested my wife send someone with a "message"–a code word for money–so that I could leave. I agreed, and sent someone to my family, to ask them to sell a goat or a cow in order to have money. They targeted me because they knew I had resources. My wife came and brought 120,000 Burundian francs (Fbu),[28] and I was freed. I gave the money to (a police officer named) Apollinaire.[29]

One former detainee reported that a police officer asked him for 20,000 Fbu.[30] When he could provide only 14,000 Fbu, he was not released. The police officer told him he would be freed if he produced another 6,000 Fbu.Unable to do so, the victim was transferred to a Muramvya jail and detained there another three weeks in violation of Burundian law, which requires detainees to be charged and presented to a prosecutor within one week of having been arrested.[31] At least three other detainees were also transferred to jails in Muramvya; one said that even though he had paid the bribe requested by GMIR officers, he was still transferred to a Muramvya jail and was freed only after paying a second bribe to a judicial police officer there.[32]

None of those arrested in October was charged with any criminal offence. All were released after periods of detention–some after a few hours, most after a week or so, but a few after nearly a month.

Police Brutality and Intimidation of Local Residents

Meanwhile, residents, including a police officer, who complained about police conduct were themselves abused by the police. On October 25, for example, a judicial police officer spoke about the abuses at Kaniga during a workshop on police conduct that was organized by the Burundian human rights organization Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detained Persons (Association pour la Protection des Droits Humains et des Personnes Detenus, APRODH.) Upon returning to Rutegama that evening, he was confronted by GMIR officers who beat him and detained him overnight at the health center.[33] A woman who witnessed his arrest and challenged the police about their conduct, told the Human Rights Watch researcher that in response to her question she was beaten in Rutegama town center by the Rutegama chief of security police, Nestor Niyokuri. She later filed charges against him.[34]

Three other persons also told the Human Rights Watch researcher that GMIR officers and Nestor Niyokuri beat them in the town center on or about October 26, after they questioned police conduct or, in one case, approached police officers while they were beating another person.[35] One victim recounted:

I went to a bar [in Rutegama]… A police officer from Kaniga came and was talking to [a woman]. I saw that the police officer was harassing [the woman] and I intervened and said he shouldn't do that. He said it was none of my business… I left, but the police officer followed me. Outside the bistro, the police officer hit me on the cheek, and I fell on the ground.

Just then, a vehicle arrived with the police from Kaniga and the Chef de Poste. They all started beating me. There were about 8 or 9 people who beat me. They kicked me on the neck, and used their hands and feet. They were beating me just because I had stood up for [the woman].[36]

During the period when the GMIR officers were active in Rutegama, other locally-based security police officers also tried to intimidate residents. According to one resident, Provincial Internal Security Police Commissioner Viateur Muco "came to my house and asked me why I was an FNL sympathizer… Later, a neighbor told me that my name was on a list of people who were to be arrested. I wasn't arrested, but I am still afraid."[37] Another resident said the same official warned him to stop doing things that the police did not like and "asked me if I had information on the FNL. I said I didn't know anything abut them. He said 'If you try to join them, we'll arrest you immediately.'"[38] As mentioned above, according to the ceasefire agreement signed between the Government of Burundi and the FNL in September 2006, being a member of the FNL is not a crime.[39]

IV. Background

These events took place in the context of intensified political tension in Burundi, the proliferation of illegal small arms in civilian hands and a growing problem of armed robbery.

On September 7, 2006 the government of President Pierre Nkurunziza and the armed opposition FNL, led by Agathon Rwasa, signed a ceasefire, to be implemented over a period of six months under the supervision of a Joint Verification and Monitoring Mechanism.[40] Pierre Nkurunziza, and his party, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (Conseil national pour la défense de la démocratie-Forces pour la défense de la démocratie, CNDD-FDD), itself a former armed opposition movement, had come to power in 2005, in Burundi's first elections under a new constitution accepted by a popular referendum earlier in the year. The FNL had remained in armed opposition.

The 5,600 United Nations peacekeepers participating since May 2004 in the United Nations Operation in Burundi (Operation des Nations Unies au Burundi, ONUB) left the country in December 2006. They were replaced by the civilian United Nations Integrated Office in Burundi (BINUB), whose primary mission is to support consolidation of the peace and to coordinate UN agencies working in Burundi, and by 1,100 South African peacekeeping troops working under the aegis of the African Union.[41]

Talks on implementing the 2006 ceasefire started belatedly in February 2007. The FNL quit the discussions on July 21, 2007, alleging that the South African facilitator was partial to the government.[42] In the meantime, in contravention of the ceasefire agreement, the FNL continued to recruit new combatants, and by the time of its withdrawal from the talks, Burundian authorities and BINUB estimated the FNL to be as much as twice as strong as it had been at the time of the ceasefire.[43] Although the FNL has not formally withdrawn from the ceasefire deal, in late 2007 and early 2008 FNL soldiers carried out several attacks on both government troops and so-called "FNL dissidents"-combatants who had quit the movement and moved into cantonment sites (camps where FNL combatants wishing to demobilize are protected by government and African Union soldiers while questions concerning their disarmament and reintegration are resolved).

The FNL's departure from the implementation talks coincided with an increase in crime throughout the country, most notably robbery. The number of armed or aggravated robberies committed by civilians and recorded by the Burundian police in 2007 was 4,004, up from 2,530 in 2006.[44] The increase in robberies reflects both an opportunistic resumption of predatory attacks as well as the growing desperation of many Burundians in the face of continuing poverty and the failure of long-promised economic improvements to materialize.[45] Much of the crime has been perpetrated by current and former FNL combatants as well as by other assailants who have often posed as FNL combatants.[46]

The proliferation of illegal firearms in the hands of civilians (and the conduct of ill-disciplined police officers and soldiers) is often said to contribute to both the number and seriousness of crimes committed.[47]During the years of conflict, previous governments occasionally provided arms to civilians to form militias for local defense. In addition many Burundians obtained arms to protect themselves, their families, and their property. Gun possession is in most cases illegal, though a small number of civilians receive gun permits by applying to the Ministry of Defense.[48]

The current government launched a campaign in mid-2006 to collect illegal firearms, estimated as between 100,000 and 300,000, and established a Technical Commission for Civilian Disarmament and the Fight Against the Proliferation of Small Arms (Commission Technique de désarmament de la population civile et lutte contre la prolifération des armes légères et de petit calibre, CTDC).[49] The commission started with few resources and has not yet made any significant impact on the number of firearms present throughout the country.[50] Recent data released by BINUB suggests that civilian disarmament efforts may not greatly reduce property crime: only about 1% of recorded thefts perpetrated by civilians in 2007 involved firearms.[51] Police sources suggested the majority of armed robberies in 2007 were committed by members of the FNL, a group that is not currently targeted by the forced disarmament campaign.[52]

The Burundian National Police

One of the significant challenges faced by the current government has been the building of a competent, properly-trained, professional police force. Security sector reform has been an integral feature of each agreement aimed at ending civil war between the Burundian government and rebel groups, beginning with the Arusha Accord of 2000. A new national army and a national police force have been established, each including members of former government forces and former rebel combatants.

Formally established on December 31, 2004, the Burundian national police is a civilian force operating under the newly created Ministry of Public Security, formerly an arm of the Ministry of the Interior.[53] It consists of four commissariats: the Internal Security Police (PSI), the Judicial Police (PJ), the Penitentiary Police, and the Police for Air, Borders and Foreigners (PAFE). The Rapid Mobile Intervention Groups (GMIR), a specialized reserve founded in 2006, was part of the PSI until December 2007, when under a police restructuring program it became a stand-alone force directly accountable to the director of the national police.

Judicial police officers and security police officers share responsibility for the prevention and punishment of ordinary crime and are most regularly and directly in contact with the population. The judicial police investigate crimes, question suspects, and provide evidence to the prosecutor (Ministère Public).[54] The security police guard public places, apprehend perpetrators, and execute search and arrest warrants issued by the prosecutor.[55]Security police, including GMIR agents, are not authorized to conduct interrogations or to detain suspects.

The integration of demobilized combatants has caused the number of national police to swell from 2,300 in 2000 to somewhere between 15,000 and 20,000 officers in 2007.[56] The actual current number of police officers appears to be unknown even to those heading the force, because not all have been registered and some do not have administrative files.[57] It is widely recognized, however, that the size of the police force far exceeds national needs. In accord with conditions set by the International Monetary Fund for future aid, the police force plans to select and demobilize officers in order to reach a target number of 15,000, but as of late 2007 this had barely begun, in part because of delays in the implementation of a program to identify and register officers, which is to be carried out with the assistance of the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), an international NGO.

The force established in 2004 incorporates elements from the former Public Security Police (PSP) and Judicial Police, the former government army and gendarmerie, and former armed opposition movements. The latter make up over a third of the new police force. Merging these diverse components into a single, impartial force to serve citizens of all ethnic and political affiliations, and ensuring that all officers are trained to the necessary standard, have proven to be major challenges. Officers from the former police force had been trained to do police work, but soldiers transferred from the army had military but no police training. In addition, according to one high-ranking police officer, some of the soldiers transferred from the army had performed poorly in military service and were sent to the police because the army did not wish to retain them.[58] More than a third of the new police officers were former rebel combatants with no formal police or military training. Some of these new officers are illiterate.[59]

With the need for training obvious, several international governmental and nongovernmental actors have been providing assistance, detailed below. But despite their efforts, at the end of 2007 a substantial number of officers-certainly more than half-were operating with little or no training.[60] This is a problem of particular concern given that many officers had served with armed forces or factions known to have engaged in human rights violations.[61]Despite a provision in the 2000 Arusha Accord requiring the exclusion from the police force of former combatants found guilty of "genocide, the coup d'etat of October 21, 1993, human rights violations or war crimes," Burundi has not established any mechanism to screen police officers for crimes related to the armed conflict, nor have the majority of such crimes been prosecuted. Thus no violators have been excluded from the security forces.[62]

Despite efforts to create a unified, impartial force, it is widely accepted in Burundi that under the surface some officers have retained strong political loyalties, particularly those who were once part of the FDD, the military branch of the CNDD-FDD.[63] Under the terms of the 2003 Pretoria Protocol signed between the interim government and the CNDD-FDD when it was still a rebel movement, FDD combatants were to make up 35 per cent of the police force.[64] At the time of the events described in this report, the Minister of the Interior and Public Security, the director general of the police, the Commissioner General of the PSI, and the chief commander of the GMIR were all former CNDD-FDD officers, creating a chain of command heavily weighted towards one political party. However, Desiré Uwamahoro, commander of the unit responsible for events described in this report, was apparently from an armed faction that split off from the CNDD-FDD in 2001.[65]

Police officers are prohibited from belonging to political parties so none is openly a CNDD-FDD member, but some police officers as well as other observers claim that former FDD combatants sometimes follow orders from CNDD-FDD members who are high-ranking officials but not their hierarchical superiors or even police officers.[66] One high-ranking police official told a Human Rights Watch researcher that "The police are politicized. At times we are obliged to work in the shadows."[67] This sentiment was echoed by a GMIR officer present at Rutegama, who told Human Rights Watch, "The party uses the national police to get people in line." In his estimation, the unit was sent to Muramvya "because the government thinks that people are abandoning the party in power, and that people won't vote for them in 2010… They sent us there to intimidate the population, to win back the population by force."[68]

V. The Official Response to Reports of Human Rights Violations

On receiving reports of illegal detentions and beatings at Kaniga, a number of local officials stepped in to try and restore due process and put an end to abuses. These interventions reduced the scale of the violations, but did not stop police abuses completely. A judicial police officer working in Rutegama contacted the Muramvya authorities about the abuses. On October 16, eight days into the arrests, a Muramvya deputy prosecutor and the Muramvya commissioner of the judicial police accompanied that officer to Kaniga to investigate his complaints. They found more than a dozen detainees, many bearing scars from torture.[69]The deputy prosecutor informed the GMIR police officers that Kaniga was an illegal detention site and that torture was prohibited. He insisted that they free the detainees, but the police refused, saying he would have to speak with Commander Uwamahoro, who was not present.[70]

The same day, Provincial Internal Security Police Commissioner Viateur Muco arrived independently at the Kaniga health center, after GMIR officers had told him that a woman was detained there (they were apparently concerned that a woman was detained with men). Commissioner Muco transferred the woman and two other detainees to jails in Muramvya town and freed one detainee. However, for reasons that remain unclear, the commissioner left others in the illegal detention center.[71] A victim told a Human Rights Watch that Muco was well aware of the presence of others.[72] Another victim said that when detainees were transferred or freed on October 16, the GMIR officer taking notes during interrogations, whom victims assumed to be a judicial police officer, told him he should stay because his file was not yet finished.[73]

Two days later, on October 18, the governor of Muramvya and another deputy prosecutor attempted to visit the center, but were refused access by Commander Uwamahoro.[74]On October 19, the Muramvya Prosecutor arrived at the health center with the provincial judicial police commissioner. By this time, all remaining detainees had been freed apart from the several who had been transferred to Muramvya.[75]

One detainee said that upon his release he was threatened by Commander Uwamahoro, "If you talk about what happened, you will be abducted."[76] Despite receiving a similar injunction, another victim contacted APRODH after his release, spurring investigations by APRODH, BINUB and Human Rights Watch, beginning the following week.[77] Detentions reduced in number but did not entirely end at this time. For example, the judicial police officer who spoke up against torture cited above was held overnight at Kaniga on October 25.

Following the intervention of human rights organizations and BINUB human rights officers, who contacted the police spokesperson and other police authorities in late October to protest the abuses, Burundian police officials recalled the GMIR unit under Commander Uwamahoro to Bujumbura in early November and re-posted it to several city neighborhoods.[78] According to residents, a new GMIR unit sent to Rutegama in November continued the practice of illegal nighttime searches. Its officers are reported to have illegally detained at least one person in the health center rather than transferring him to the judicial police.[79] Additionally, local security police chief Nestor Niyokuri, who was also implicated in human rights violations, remained on duty in Rutegama until February 2008.[80] According to one victim, the police chief threatened her after the initial abuse and arrested another person who had spoken with human rights organizations.[81]

Beyond the immediate interventions to halt abuses by the GMIR unit based at Kaniga in October 2007, the police and judicial authorities have been slow to address human rights violations, with the result that as of this writing not a single officer involved in these events has been disciplined or brought to justice. Indeed, Commander Uwamahoro has been promoted from head of a single GMIR unit to commander of the 3rd GMIR group.[82]

Three victims filed complaints with the Muramvya prosecutor's office in late October, but the prosecutor initially took no steps toward interviewing witnesses or calling in suspects for questioning. He told a Human Rights Watch researcher that he had not received one of the complaints filed, although a BINUB human rights observer later found this complaint on his desk.[83]Two of the victims who initially filed complaints were among those who had visible scars, but the prosecutor never ordered medical examinations of their healed wounds.[84]

Other victims initially expressed reluctance to press charges, fearing retaliation. In late November, however, a number of them agreed to provide testimony as part of a collective complaint of 13 victims submitted by Avocats Sans Frontières, an international nongovernmental organization, to the Muramvya prosecutor on November 30, 2007. In mid-December the Muramvya prosecutor finally issued summonses for GMIR Commander Uwamahoro, GMIR Brigadier Apollinaire Sindihokubwayo, and Rutegama security police chief Nestor Niyokuri. The three were interrogated by magistrates in Muramvya on December 20. All three denied that prolonged detention and beatings had occurred at Kaniga. However, a deputy prosecutor told the Human Rights Watch researcher that charges against them would be brought before the Muramvya courts.[85]

Police officials asked about the abuses by Human Rights Watch either denied they had taken place or sought to justify police misconduct and violations of procedure at Rutegama. One official explained, "People were slapped around a bit, but it was necessary to get information."[86] In another discussion, the same official responded to questions about torture by stating that the GMIR unit had confiscated eight Kalashnikovs, 14 grenades, and a pair of night vision goggles from the residents in and around Rutegama, as if to suggest the recovery of these firearms justified whatever methods might have been used.[87] The head of GMIR insisted that no one had been held in an illegal detention site and that all persons arrested by the GMIR had been turned over immediately to the judicial police, while the Commissioner General of the security police said the GMIR had not conducted interrogations.[88]

In early November, authorities from both the Internal Security Police Commissariat and the Judicial Police Commissariat began internal investigations of the events at Kaniga, but they produced no public report. The commissioners of both police branches were replaced in December 2007 in a restructuring of the national police, and their replacements both told a Human Rights Watch researcher in February that they were unaware of the status of these investigations.[89] The commissioner general of the Internal Security Police has the authority to suspend officers suspected of wrongdoing.[90] But when a Human Rights Watch researcher asked the then commissioner general Gabriel Nizigama why this had not been done in spite of testimony provided by multiple victims, he said the evidence did not constitute sufficient grounds to take such steps against Uwamahoro, Sindihokubwayo and Niyokuri.[91]

Commissioner General Gabriel Nizigama did ask GMIR Commander Uwamahoro to submit a report to his superiors about the events that took place at Rutegama. According to David Nikiza, the commander of the three GMIR groups in Bujumbura, the report consisted only of a description of searches carried out and weapons confiscated, and did not include information on any arrests made or the treatment of persons held at the health center. [92]

In at least two cases, authorities including the prosecutor and governor of Muramvya and Commander Uwamahoro attempted to facilitate "amiable resolutions" between victims and the police officers who beat them.[93] While "amiable resolution" facilitated by local authorities is a common practice in Burundi, it is generally used to resolve conflicts between family members or neighbors. Mediation is not an acceptable alternative to accountability in the case of serious human rights violations.

In December 2007, the new director general of the National Police, appointed in November 2007 after the incidents discussed in this report, told a Human Rights Watch researcher that within the next few months he would begin collecting information on police abuse from citizens and local officials, including in Rutegama. He said that police officers responsible for abuses would be demoted or demobilized.[94] A number of police officers were in fact demobilized for disciplinary reasons between November 2007 and March 2008, but none of the officers accused of abuses in Muramvya were among that number.[95]

Professionalism and Impunity

The abuses in Rutegama in October 2007 are indicative of a set of inter-linked problems that bedevil the Burundian police-problems of ill-discipline, lack of professionalism, and failures of accountability. Equipped with little training in policing but much experience of insurgency and counterinsurgency, many police officers do not enforce laws effectively, and some are themselves responsible for crimes and human rights abuses, which are rarely punished.

According to BINUB and the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights in Burundi, between January and October 2007 police officers committed at least 15 killings, 125 cases of assault, and six cases of rape.[96] Avocats Sans Frontières has received 119 complaints of torture by police officers, committed mostly in prisons and jails, in the last two years.[97]

There are good reasons for believing that these reported incidents are only a proportion of the abuses that have actually taken place. Many victims do not press charges against police or even report abuses to human rights organizations because they fear retaliation.[98] Others believe that pressing charges will be futile. The sense of futility is reinforced by the failure of even members of the political elite to get the perpetrators of abuses against them brought to justice. Speaking of the widely-known case of former Vice-President Alphonse Kadege detained in 2006 (who has not managed to have the police officers who allegedly tortured him brought to account), one Burundian political analyst remarked, "If former Presidents and Vice-Presidents can't get justice after being tortured, how can ordinary citizens?"[99]

Since the formation of the National Police, several hundred police officers have been dismissed or jailed after allegations of criminal activity, and one police officer was sentenced to 20 years in prison after being convicted of rape in Bubanza province in mid-2007.[100]But in cases of torture or ill-treatment of detainees, limited official response is more usual. Of six cases of murder and 52 of ill-treatment or torture recorded by the Burundian human rights organization Ligue Iteka between January and October 2007, only one murder and six torture cases led to charges being brought. The majority of these cases were dismissed, while others moved slowly through the judicial system. As of January 2008 not one of these cases had led to the conviction of police.[101] Avocats Sans Frontières assisted victims in filing complaints against police officers in 59 of the 119 torture cases submitted to them from early 2006 to early 2008, but only two police officers had been convicted as of March 2008; one received a two-year prison sentence, while the other paid a fine.[102]

In at least three cases in the last year, popular frustration at police misconduct has spurred violence against police officers, including lynchings of those suspected of having committed crimes.[103] A recent study of popular attitudes towards the police found that 14 percent of Burundians ranked the police as a "group at the origin of violence" in Burundi, following only "armed bandits" and the FNL as primary sources of violence.[104]

Human Rights Watch has made repeated requests to the police spokesperson and other police officials for a list of police officers arrested in 2007, the allegations against them, and the outcome of any investigations and prosecutions. It is indicative of serious weaknesses in capacity to enforce discipline and accountability that no police authority currently collects such information, and as of this writing the data had not been made available. In November 2007 the inspector general of the national police, responsible for monitoring police misconduct, said that a law has been proposed that would make the inspectorate, an agency of the Public Security Ministry, the central repository for all complaints against police officers and would authorize it to follow the progress of such complaints, but discussions of the bill and possible funding mechanisms are still at an early stage.[105]

Burundian human rights monitors note that there is a general culture of mutual protection among police, prosecutors and judges. In addition, former and current political loyalties may keep officers from accusing colleagues from movements with which they were formerly affiliated.[106] According to Burundian human rights monitors, superior officers often respond to allegations of abuse by an officer by simply transferring the alleged perpetrator to another province.[107] Given the absence of administrative files for many officers, repeated violations may go unnoticed, even if some disciplinary sanctions have been imposed.

VI. International and Burundian National Law

The conduct of police officers at Rutegama violates national legislation and international human rights law on several grounds, and should be subject to appropriate investigation and sanctions.

Burundi is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the 1981 African Charter on Human and People's Rights, both of which set out prohibitions on arbitrary detention and use of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment. Burundi is also a party to the United Nations Convention against Torture, which obliges states to prohibit and take appropriate action to prevent and sanction acts of torture, and also acts of inhuman and degrading treatment. Torture under the Convention is defined as "any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person […] when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity."[108]

The Convention against Torture requires that state parties undertake a prompt and impartial investigation wherever there is reasonable ground to believe that an act of torture has been committed.[109] Further, the UN Principles on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (2001) provides that "Even in the absence of an express complaint, an investigation should be undertaken if there are other reasons to believe that torture or ill-treatment might have occurred."[110]

Burundian national law currently fails to prescribe penalties for torture, except if it results in death or is carried out in the course of an abduction.[111] A prohibition on torture, however, is part of a proposed new criminal code, currently before the National Assembly. The current criminal law prohibits "voluntary bodily injury" and prescribes a penalty of up to two years in prison if the injury is premeditated.[112] Also prohibited is the extortion of funds carried out under threat of violence, punishable by five years in prison.[113] The 2004 law on the creation, organization, missions, composition, and operation of the National Police prohibits the police from using force, except when in pursuit of a legitimate objective that cannot be achieved without force.[114]

In addition to violating international and national law on torture, bodily injury, extortion, and the use of force, the conduct of some GMIR officers at Kaniga violated provisions of the Burundian code of criminal procedure, and the 2004 law on the National Police relating to procedure. These laws specify that only judicial police officers may interrogate suspects. GMIR officers are not part of the judicial police.[115] The commissioner general of the Internal Security Police told Human Rights Watch that security police officers have the authority to hold suspects for 24 hours before turning them over to the judicial police, but this assertion was contested by other police officials and an experienced jurist, who said suspects must be turned over to the judicial police "immediately" after their detention.[116]

According to Burundian law flagrant violations of criminal procedure are subject not only to internal disciplinary proceedings but also to criminal sanctions. The conduct of illegal arrests and detentions, for example, is punishable by imprisonment for to up to a year.[117]

VII. Response by International Actors

Well aware of the risks of an ill-trained police force, international donors have provided several training programs for the Burundian police.

In September 2006, the Belgian Technical Cooperation initiated a three-year program for Belgian police to train their Burundian counterparts in community-oriented policing, but actual training began only in September 2007. By the end of 2007 5,144 police officers had received an initial one week of training under this program, as part of a more extensive curriculum which they will follow in alternating groups of 1250 police officers at a time.[118] According to Director General of the National Police Fabien Ndayishimiye, the training included an emphasis on human rights and respect for rule of law.[119] Other international donors and NGOs have also provided training relevant to human rights, but these more limited programs have not reached the majority of officers.[120]

In addition to the Belgian program, which focuses on the rank-and-file, France has provided training to commanding officers. The Netherlands has committed funding to the ICTJ-facilitated census of the police, and a Dutch police advisor is working directly within the Burundian police to develop a strategic reform plan. As an element of this plan the Netherlands is considering financing the office of the inspector general of the police in its efforts to serve as an internal monitor of police conduct. Such a step could be helpful in curbing police abuses.[121]

No formal structure is currently in place to coordinate donor assistance to the police. In 2007 the Burundian government and donor partners launched the Partners' Coordination Group (Groupe de Coordination des Partenaires, GCP) to monitor international aid associated with the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and the Strategic Framework for Peacebuilding.[122]The GCP encompasses several working groups that coordinate aid to different sectors, but no working group on the police or on security sector reform was in place as of March 2008.[123]A police working group could harmonize aid programs and ensure adequate attention to human rights.

UN officials, both in the previous ONUB operation and in the current BINUB, have played a significant role in police reform and training. The UN Peacebuilding Fund (PBF), a fund operated in conjunction with the UN Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) with the aim of strengthening institutions in post-conflict states, granted $6,900,000 to the national police in July 2007, but the training to be financed by a portion of this funding had not yet been initiated as of March 2008.[124]

UN Human Rights officers working under the combined direction of BINUB's Human Rights and Justice Section and the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR) have effectively monitored violations of human rights by the police. They, like Burundian human rights organizations, have been forthright in demanding accountability.

VIII. Annex: Documented Cases of Police Abuse in Rutegama Commune[125]

Victim |

Date of Incident/ Period of Illegal Detention |

Accusations against Victim Made by Police at Time of Arrest |

Type of Mistreatment |

A. Victims Detained at KanigaHealthCenter | |||

1. Businessman |

October 8-13, 2007 |

FNL membership, weapons possession |

Beaten with batons and clubs on hands, legs, buttocks, and back; slapped in the face |

2. Farmer |

October 8-13, 2007 |

Weapons possession, FNL membership |

Beaten with batons on entire body; mock execution; paid 120,000 Fbu for release[126] |

3. Demobilized FDD combatant |

October 8-16, 2007; continued detention in Muramvya through November 7 |

FNL membership, weapons possession |

Beaten with clubs and batons on the buttocks; mock execution |

4. Woman |

October 9-16, 2007; continued detention in Muramvya through November 7 |

FNL membership, theft, weapons possession |

Beaten on the buttocks with a baton while handcuffed on the ground |

5. Demobilized FDD combatant |

October 10-19, 2007 |

Weapons possession, FNL activity |

Picked up by arms and legs, beaten by eight police agents with batons and clubs on buttocks; rocks placed in mouth; threatened with death with an iron bar; forced to watch torture of others ; 22,000 Fbu taken during beating |

6. Laborer |

October 10-16, 2007; continued detention in Muramvya through November 7 |

FNL membership, weapons possession |

Beaten on buttocks, stomach, and hands with a club; mock execution; paid 14,000 Fbu for release, but detained further because he was unable to produce another 6,000 Fbu |

7. Chef de colline (local official) |

October 12-17, 2007 |

Failure to arrest a thief |

40 blows with batons and clubs on the buttocks and stomach; paid 35,000 Fbu for release |

8. Woman |

October 13, detained for a period of hours |

Weapons possession |

Beaten |

9. Teacher |

October 13-16, 2007 |

FNL membership |

Picked up by arms and legs, beaten on buttocks and stomach with batons about 50 times; death threats; cloth placed in mouth during beating |

10. Teacher |

October 13-19, 2007 |

FNL membership, weapons possession |

Picked up by arms and legs, beaten on buttocks and stomach; death threats; paid 40,000 Fbu for release |

11. Farmer |

October 16-19, 2007 |

Selling stolen cattle, weapons possession |

Picked up by arms and legs, beaten on buttocks with clubs; rocks placed in mouth |

12. Man |

October 16-19, 2007 |

Selling stolen cattle, weapons possession |

Picked up by arms and legs, beaten on buttocks with clubs; rocks placed in mouth |

13. Man |

October 16-19, 2007 |

Selling stolen cattle, weapons possession |

Beaten |

14. Man |

October 16-19, 2007 |

Selling stolen cattle, weapons possession |

Beaten; paid unknown sum for release |

15. Police officer |

October 25-26, 2007 |

Insulting GMIR Commander |

Beaten |

16. Man |

October 29, 2007 |

Motorcycle theft |

Beaten at Kaniga |

B. Victims Beaten in RutegamaTown | |||

17. Teacher |

October 25, 2007 |

Challenging arrest of previous victim |

Beaten in town of Rutegama; death threats |

18. Resident of Internally Displaced Persons' Camp |

October 25, 2007 |

In company of previous victim |

Slapped in face, kicked on legs and buttocks in town of Rutegama |

19. Man |

October 26, 2007 |

Observing beating of another victim |

Slapped and threatened in town of Rutegama |

20. Farmer |

October 26, 2007 |

FNL membership |

Beaten with a club on the buttocks in town of Rutegama |

21. Police officer |

October 26, 2007 |

Telling GMIR agent not to harass a woman |

Beaten by 8 or 9 police in town of Rutegama |

[1] A number of the police officers mentioned in this report were transferred to new positions but remained in active service following a reshuffling of police leadership on December 13, 2007. Unless otherwise noted, titles given refer to police officers' positions in October 2007. Decret No. 100/360 du 13 decembre 2007 portant nomination de certains cadres de la Direction Generale de la Police National du Burundi.

[2] The GMIR groups are known respectively as the 1st, 2nd and 3rd GMIR. Each one consists of approximately 300 police officers and is divided into several functional "units."

[3] Human Rights Watch interviews with police spokesperson Pierre Chanel Ntarabaganyi, Bujumbura, November 16, 2007; Commissioner General of the Internal Security Police Gabriel Nizigama, Bujumbura, November 19, 2007; and Commissioner General of the Judicial Police Deo Suzuguye, Bujumbura, November 20, 2007.

[4] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Bujumbura, November 1, 2007.

[5] Human Rights Watch interview with GMIR police officer, Bujumbura, November 21, 2007.

[6] Loi No. 1/015 du 20 juillet 1999 portant réforme du code de procedure penale, art. 52; Loi No. 1/020 du 31 December 2004 portant creation, organization, missions, composition, et fonctionnement de la Police Nationale, art. 30.

[7] Under the terms of the Comprehensive Ceasefire Agreement Between the Government of Burundi and the PALIPEHUTU-FNL, Dar es Salaam, September 7, 2006, membership in the FNL is not a crime.

[8] The spokesperson of the Burundian police claimed that no one was detained for FNL membership but that some persons were detained for prohibited activities linked to membership. Because police maintained no register of the detainees and the charges on which they were held and because all detainees were eventually released without charge, it is difficult to ascertain with certainty the reason for arrest that was provided at the time. Human Rights Watch interviews with victims, Bujumbura, November 1 and November 20, 2007, and Rutegama, November 2, 2007, and police spokesperson Pierre Chanel Ntarabaganyi, Bujumbura, November 16, 2007.

[9] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Bujumbura, November 20, 2007.

[10] Human Rights Watch interviews with victims, Bujumbura, November 20, 2007, and GMIR police officer, Bujumbura, November 21, 2007.

[11] Human Rights Watch visit to Kaniga health center, October 23, 2007, and interview with victim, Bujumbura, November 20, 2007.

[12] Human Rights Watch interview with GMIR police officer, Bujumbura, November 21, 2007.

[13] PSI officers are authorized to arrest suspects in only three instances: when they are caught « red-handed »; when they are pointed out by witnesses immediately following a crime; and on the basis of a warrant. Loi No. 1/020 du 31 December 2004 portant creation, organization, missions, composition, et fonctionnement de la Police Nationale, art. 21.

[14] Burundian law does not explicitly define what constitutes a legal detention site. However, Burundian judicial and police authorities explained that the Kaniga site was unknown to judicial authorities and thus in violation of accepted standards of detention. Human Rights Watch telephone interviews with Muramvya deputy prosecutor, March 22, 2008, and with a judicial police officer, March 24, 2008.

[15] Human Rights Watch interview with police spokesperson Pierre Chanel Ntarabaganyi, Bujumbura, November 16, 2007.

[16] Loi No. 1/020 du 31 December 2004 portant creation, organization, missions, composition, et fonctionnement de la Police Nationale, art. 27.

[17] Human Rights Watch interview with Commissioner General of the Internal Security Police Gabriel Nizigama, Bujumbura, November 19, 2007, and GMIR police officer, Bujumbura, November 21, 2007.

[18] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Bujumbura, November 1, 2007.

[19] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Rutegama, November 2, 2007.

[20] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Bujumbura, November 1, 2007.

[21] Human Rights Watch interviews with victims, Bujumbura, November 1, 2007, and Rutegama, November 2, 2007.

[22] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Bujumbura, November 20, 2007.

[23] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Rutegama, November 2, 2007.

[24] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Muramvya, November 2, 2007.

[25]International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, G.A. res. 2200A (XXI), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, ratified by Burundi on May 9, 1990.

[26]African [Banjul] Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, adopted June 27, 1981, OAU Doc. CAB/LEG/67/3 rev. 5, entered into force October 21, 1986, ratified by Burundi on July 28, 1989.

[27]Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention against Torture), adopted December 10, 1984, G.A. Res. 39/46, annex, 39, U.N. Doc. A/39/51, entered into force June 26, 1987, ratified by Burundi on February 18, 1993, art. 1 and 2.

[28] Approximately $110. 1000 Burundian francs, Fbu, is equivalent to just under one US dollar.

[29] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Bujumbura, November 20, 2007.

[30] Approximately $18.

[31] Human Rights Watch interviews with victim, Muramvya PSI jail, November 2, 2007, and Bujumbura, November 20, 2007; Loi No. 1/015 du 20 juillet 1999 portant réforme du code de procedure penale, art. 60-65.

[32] Human Rights Watch interviews with victim, Rutegama, November 2, 2007.

[33] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with victim, October 29, 2007.

[34] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Bujumbura, November 1, 2007.

[35] Human Rights Watch interviews with victims, Rutegama, November 2, 2007.

[36] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Rutegama, November 7, 2007.

[37] Human Rights Watch telephone interview, October 23, 2007.

[38] Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview, Muramvya, October 23, 2007.

[39] Comprehensive Ceasefire Agreement Between the Government of Burundi and the PALIPEHUTU-FNL, Dar es Salaam, September 7, 2006.

[40]The verification mechanism included seven representatives each from the Government of Burundi and the FNL as well as representatives from the national demobilization commission, the African Union (AU), BINUB, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda. "Joint truce verification mechanism launched," IRIN, October 11, 2006, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/news/2006/10/mil-061011-irin05.htm (accessed December 7, 2007).

[41] United Nations Security Council Resolution 1719 (2006), October 25, 2006

[42] After months of deadlock, government and FNL representatives held talks in Dar es Salaam from January 21 to January 30, 2008 and agreed to resume talks on implementing the ceasefire, but their representatives had not yet returned to Burundi as of March 2008.

[43] Human Rights Watch interview with National Defense Forces (Forces de la Défense Nationale, FDN) spokesperson Adolphe Manirakiza, Bujumbura, November 26, 2007; Bureau Integré des Nations Unis au Burundi/Office du Haut Commissaire aux Droits de l"Homme aux Burundi, "Rapport sur la situation des droits de l'homme au Burundi; Rapport Mensuel, April 2007"and "Rapport sur la situation des droits de l'homme au Burundi; Rapport Mensuel, May 2007", unpublished documents.

[44] BINUB, "Analyse de la Criminalité", March 15, 2008. Unpublished document submitted to Human Rights Watch via email, March 25, 2008.

[45] International Monetary Fund, "Burundi: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper", IMF Country Report No. 07/46, February 2007, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2007/cr0746.pdf (accessed March 24, 2008).

[46] Human Rights Watch interview with Commissioner General of the Internal Security Police Gabriel Nizigama, Bujumbura, November 19, 2007; "Insécurité : l'armée burundaise restreint la circulation routière", PANA, November 17, 2007, reprinted in Arib News, November 18, 2007, www.arib.info/flash-info.html (accessed December 7, 2007).

[47] Stephanie Pézard and Nicolas Florquin, Small Arms in Burundi: Disarming the Civilian Population in Peacetime (Geneva: Small Arms Survey, 2007), p. 3.

[48] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with FDN spokesperson Adolphe Manirakiza, March 24, 2008.

[49] Human Rights Watch interviews with President of the Technical Commission on Civil Disarmament and the Fight against the Proliferation of Small Arms (CTDC) Sylvestre Kibeceri, Bujumbura, October 8, 2007, and a representative of Danish Church Aid, Bujumbura, November 22, 2007; CTDC press release, November 29, 2006, as cited in Centre d'Alerte et de Prevention des Conflits (Bujumbura), "Etude sur la réforme du secteur de sécurité pour la protection de la population civile," undated, p. 38.

[50] The police began a massive campaign of forced disarmament in January 2008 and have successfully collected a number of firearms. In some cases they have failed to respect procedure. For example, they have searched homes without presenting a search warrant, and without the involvement of judicial police officers, who must be present at all searches. Human Rights Watch interview with representative of Ligue Iteka, Bujumbura, March 3, 2008, and representative of the Public Prosecutor's office, Bujumbura, March 3, 2008.

[51] BINUB, «Analyse de la Criminalité», March 15, 2008. Unpublished document submitted to Human Rights Watch via email, March 25, 2008.

[52] Human Rights Watch interview with Assistant Director General of the National Police Gervais Ndirakobuca, Bujumbura, March 26, 2008.

[53] The Ministry of Public Security was established as part of a reorganization of government on November 14, 2007. The Minister of Public Security is Alain Guillaume Bunyoni, former Director General of the national police; he was replaced as police Director General by Fabien Ndayishimiye.

[54] Loi No. 1/020 du 31 December 2004 portant creation, organization, missions, composition, et fonctionnement dela Police Nationale, art. 27.

[55] Loi No. 1/020 du 31 December 2004 portant creation, organization, missions, composition, et fonctionnement dela Police Nationale, art. 19-26.

[56] BINUB estimates that the integrated forced in early 2005 included 2079 former Public Security and Judicial Police officers; 8257 ex-gendarmes; 3000 former soldiers; and 6744 former members of armed political parties and movements. By November 2005, 1,546 of those police who were past retirement age had been demobilized, most of them from the former police and gendarmerie, leaving a total of 18,534 police officers. Human Rights Watch interview with official of BINUB Security Sector Reform and Small Arms Unit, Bujumbura, December 19, 2007.

[57] Director General of the National Police Fabien Ndayishimiye, press conference, Bujumbura, November 29, 2007; Centre d'Alerte et de Prévention des Conflits (Bujumbura), "Etude sur la réforme du secteur de sécurité pour la protection de la population civile," undated, p. 20.

[58] Human Rights Watch interview with police official, Bujumbura, November 30, 2007.

[59] Human Rights Watch interview with official of BINUB Security Sector Reform and Small Arms Unit, Bujumbura, November 20, 2007; Republic of Burundi and Cooperation Belgo Burundaise, "Projet d'Appui à la Formation de la Police Nationale du Burundi," unpublished document distributed at press conference, Bujumbura, November 29, 2007; Centre d'Alerte et de Prévention des Conflits, p. 21.

[60] Human Rights Watch interview with Director General of the National Police Fabien Ndayishimiye, Bujumbura, November 30, 2007.

[61] For background on wartime human rights violations committed by both rebel movements and the former Burundian army, see Human Rights Watch, Everyday Victims: Civilians in the Burundian War, vol. 15, no. 20(A), December 2003, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/burundi1203/burundi1203.pdf.

[62]Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement for Burundi, Protocol III, Chapter II, article 14, no.2 d., 2000.

[63] A report on security sector reform that was well-received enough by the new Police Director to be distributed en masse at a November 2007 press conference on police reform notes, "Since the CNDD-FDD came to power, the PNB has been conspicuous in the repression of opposition political parties and some elements of civil society… there have been cases in which elements of the police have forbidden authorized meetings of political parties, searched opposition party offices without warrants, and put journalists under surveillance without official approval for such activities." Centre d'Alerte et de Prévention des Conflits (Bujumbura), p. 25.

[64] Pretoria Protocol on Political, Defense and Security Power Sharing, October 8, 2003, paragraph 2.2.

[65] Human Rights Watch interview with Assistant Director General of the National Police Gervais Ndirakobuca, Bujumbura, March 26, 2008.

[66] Human Rights Watch interviews with judicial police official, Bujumbura, December 21, 2007, Burundian analyst, Bujumbura, December 19, 2007, and Burundian jurist, March 26, 2008.

[67] Human Rights Watch interview with judicial police official, Bujumbura, December 21, 2007.

[68] Human Rights Watch interview with GMIR police officer, Bujumbura, November 21, 2007.

[69]Human Rights Watch telephone interviews with Muramvya deputy prosecutor, November 28, 2007 and March 22, 2008; Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with judicial police officer, Rutegama, October 23, 2007.

[70] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Muramvya deputy prosecutor, March 22, 2008.

[71] Human Rights Watch interviews with victims, Bujumbura, November 1, 2007 and Muramvya, November 2, 2007, and GMIR police officer, Bujumbura, November 21, 2007.

[72] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with victim, March 19, 2007.

[73] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Rutegama, November 2, 2007.

[74] Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Muramvya deputy prosecutor, Muramvya, October 23, 2007.

[75] Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Muramvya deputy prosecutor, Muramvya, October 23, 2007.

[76] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Bujumbura, November 1, 2007.

[77] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Rutegama, November 2, 2007; «Province Muramvya : la Police de Sécurité Intérieure sème l'insécurité dans les communes Rutegama et Kiganda.», APRODH news release, October 30, 2007, http://www.aprodh.org/article.php3?id_article=102 (accessed March 24, 2008).

[78] Human Rights Watch interview with GMIR police officer, Bujumbura, December 3, 2007.

[79] Human Rights Watch telephone interviews with local authorities, Rutegama residents, and local human rights observer, November 16-18, 2007.

[80] Human Rights Watch interview with new Commissioner General of the Interior Security Police Onesphore Mbazumutima, Bujumbura, March 17, 2008.

[81] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with victim, December 3, 2007.

[82] Human Rights Watch interview with new Commissioner General of the Interior Security Police Onesphore Mbazumutima, Bujumbura, March 17, 2008.

[83] Human Rights Watch interview with BINUB official, Bujumbura, November 12, 2007.

[84] Human Rights Watch interview with BINUB official, Bujumbura, January 28, 2008.

[85] Human Rights Watch telephone interviews with Muramvya deputy prosecutor, December 7 and 20, 2007, and January 3, 2008.

[86] Comment by police spokesperson Pierre Chanel Ntarabaganyi, Bujumbura, November 12, 2007.

[87] Human Rights Watch interview with police spokesperson Pierre Chanel Ntarabaganyi, Bujumbura, November 16, 2007.

[88] Human Rights Watch interviews with Commissioner General of the Internal Security Police Gabriel Nizigama, Bujumbura, November 19, 2007, and GMIR Commander David Nikiza, Bujumbura, November 23, 2007.

[89] Human Rights Watch telephone interviews with new Commissioner General of the Internal Security police Onesphone Mbazumitima and new Commissioner General of the Judicial Police Bernard Sekaganda, Bujumbura, February 18, 2008.

[90] Human Rights Watch interviews with high-ranking police officials, Bujumbura, November 21, 2007 and February 18, 2008.

[91] Human Rights Watch interview with Commissioner General of the Interior Security Police Gabriel Nizigama, December 4, 2007.

[92] Human Rights Watch interview with GMIR Commander David Nikiza, Bujumbura, November 23, 2007.

[93] Human Rights interviews with victims, October 29, 2007 (by telephone), and in Bujumbura, November 21, 2007.

[94] Human Rights Watch interview with Director General of the National Police Fabien Ndayishimiye, Bujumbura, December 18, 2007.

[95] Human Rights Watch interview with Assistant Director General of the National Police Gervais Ndirakobuca, Bujumbura, March 26, 2008.

[96] BINUB/OHCHR, "Rapport sur la situation des droits de l'homme au Burundi; Rapports Mensuels, January-October 2007", unpublished documents. The October 2007 report is available at http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/RWFiles2007.nsf/FilesByRWDocUnidFilename/EGUA-79CST3-rapport_complet.pdf/$File/rapport_complet.pdf.

[97] Avocats Sans Frontières, "Dossiers tortures en phase pré-juridictionelle" and "Dossiers torture phase juridictionelle", unpublished documents transmitted to Human Rights Watch, March 25, 2008.

[98] Human Rights Watch interviews with victims, Rutegama, November 2, 2007, representative of Action Chretien contre le Torture (ACAT), Bujumbura, November 16, 2007, and representative of APRODH, Bujumbura, November 20, 2007.

[99] Human Rights Watch interview with Burundian analyst, Bujumbura, December 19, 2007. For the cases of former President Domitien Ndayizeye and former Vice-President Alphonse Kadege detained in 2006, see Human Rights Watch, We flee when we see them: Abuses with impunity at the National Intelligence Service in Burundi, vol. 18, no. 9(A), October 2006, http://hrw.org/reports/2006/burundi1006/index.htm.

[100] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with representative of APRODH, February 4, 2008.

[101] Email communication from representative of Ligue Iteka to Human Rights Watch, November 23, 2007; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with representative of Ligue Iteka, December 19, 2007.

[102] Avocats Sans Frontières, "Dossiers tortures en phase pré-juridictionelle" and "Dossiers torture phase juridictionelle", unpublished documents transmitted to Human Rights Watch, March 25, 2008.

[103] In one case in mid-2007, two police officers were released from prison in Bururi shortly after being charged with theft. Just after their release, they were again caught stealing by local residents, who proceeded to kill them. In another recent case, a police officer was lynched in NgoziProvince in November 2007 following his alleged participation in an armed robbery and murder. Human Rights Watch interviews with representative of APRODH, Bujumbura, December 18, 2007, and February 4, 2008; email communication from representative of BINUB to Human Rights Watch, November 28, 2007.

[104] Centre d'Alerte et de Prévention des Conflits (Bujumbura), "Etude sur la réforme du secteur de sécurité pour la protection de la population civile," undated, p. 18.

[105] Human Rights Watch interviews with Inspector General Pierre Claver Gahungu, Bujumbura, November 26, 2007 and March 11, 2008 (by telephone).

[106] Human Rights Watch interview with Burundian analyst, Bujumbura, December 19, 2007. Such considerations appear to have played a part in delaying justice for soldiers and intelligence agents implicated in the killings of some 30 civilians in Muyinga province in 2006. See Human Rights Watch, We flee when we see them: Abuses with impunity at the National Intelligence Service in Burundi, vol. 18, no. 9(A), October 2006, http://hrw.org/reports/2006/burundi1006/index.htm; and "Burundi: Bring Muyinga massacre suspects to trial," Human Rights Watch news release, September 27, 2007, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2007/09/26/burund16957.htm.

[107] Human Rights Watch interview with representative of APRODH, Bujumbura, November 20, 2007.

[109] Convention against Torture, art. 12.

[110] Manual on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Punishment («Istanbul Protocol»), August 9, 1999. The United Nations General Assembly in its resolution 55/89 of February 22, 2001, drew the attention of governments to the Principles on the Effective Investigation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment of Punishment (Istanbul Principles) emanating from the Istanbul Protocol.

[111] Décret-loi no. 1/6 du 4 Avril 1981 portant réforme du code penal, art. 145 and 171.