Dying for Change

Brutality and Repression by Guinean Security Forces

in Response to a Nationwide Strike

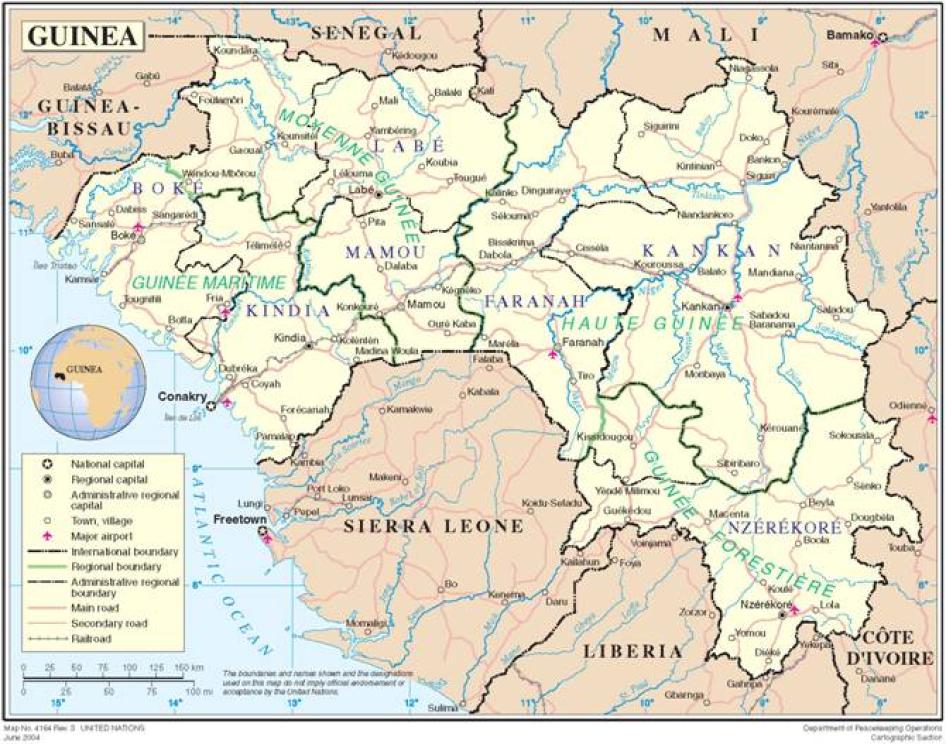

Map of Guinea

Summary

In January and February 2007, Guinean citizens weathered one of the most violent storms in their post-independence history when government security forces brutally repressed a nationwide strike organized by Guinea's most prominent trade unions to protest corruption, bad governance, and deteriorating economic conditions. According to the government's own figures, the brutal crackdown resulted in at least 129 dead and over 1700 wounded, hundreds of them by gunshot. Although the strike ended with the appointment of a new consensus prime minister in late February, ending the immediate crisis, Guinea's political stability is tenuous and the possibility of renewed unrest and repression remains very real. To stabilize the situation and to prevent further bouts of violent repression, it is critical that those responsible for the human rights abuses perpetrated during the strike be brought to account.

The third nationwide strike in less than a year, the trade unions' call to strike in mid-January resulted in immediate nationwide paralysis as economic activity in Conakry and all major towns and sectors, including the mining operations that provide a large portion of state revenue, ground to a halt. For the first time since Guinea's independence in 1958, tens of thousands of people-men and women, old and young, including members of all of Guinea's major ethnic groups-took to the streets to demand better government, clogging roads as they rallied, marched, and, at times, clashed with security forces. The protestors' most frequently chanted slogan was a single word: changement, or change.

Change, in the form of a new consensus prime minister with the power to name his own government, would come, but at a heavy cost. Throughout the strike, security forces in Guinea engaged in widespread violations of some of the most basic civil and political rights of their fellow citizens, including the right to life, security and liberty of person as well as the freedoms of expression, association, and assembly.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 115 victims of and witnesses to the violence that took place during the six-week crisis period, and collected detailed accounts alleging involvement by members of the army, the police, and the gendarmerie in murder, rape, assault, and theft. Eyewitnesses to dozens of killings told Human Rights Watch that security forces fired directly into crowds of unarmed demonstrators, frequently before they had exhausted non-lethal means of crowd control, and gunned down demonstrators trying to flee to safety. Scores of Guineans, many of them mere bystanders to the demonstrations, were severely beaten and robbed at gunpoint by security forces, often in their own homes.

In what appeared to be well-organized operations, union and other civil society leaders, as well as journalists, were threatened with death, attacked, robbed, arbitrarily arrested, and sometimes beaten by Guinean security forces. Security forces ransacked the workplaces of one of the trade unions organizing the strike, along with one of Guinea's private radio stations. Attempts to silence the trade unions appear to have come from the highest levels of government, including President Conté and his son Ousmane Conté.

The crackdown of January-February 2007, the largest in recent years, was the latest in a series of incidents in which Guinean security forces have used excessive and at times lethal force on demonstrators protesting worsening economic conditions.[1] The Guinean government has failed to hold the perpetrators of these earlier abuses to account. In many instances, the government appears to turn a blind eye to ongoing abuses by security forces.

Putting an end to the brutality and repression must include addressing the impunity that too often allows abuses to continue undeterred. Although the former Guinean Minister of Justice announced the creation of a national commission of inquiry to investigate strike-related human rights abuses, many of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch, from diplomats, to civil society leaders, to victims of human rights violations in Conakry's suburbs, note that such commissions have a poor track record in Guinea. They note that a previous commission established by the Ministry of Justice to investigate abuses following a previous violent crackdown in June 2006 has not resulted in the publication of a report with findings, much less prosecutions of any perpetrators.[2]

To allow for an investigation in which Guineans may have confidence, and which will act fairly, independently, expeditiously, and transparently, Human Rights Watch believes that it is critical that an independent body charged with investigating the crimes committed by state security forces during the January-February nationwide strike, as well as previous strikes such as June 2006 in which similar abuses were committed, be created.[3] Such a body should draw upon the experience and expertise of the international community through the involvement of members of the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

For its part, the international community has a key role to play in ensuring accountability for strike-related abuses. International donors such as the United States and the European Union, as well as international bodies such as the African Union (AU) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), must press the Guinean government for a prompt and independent investigation that draws upon the experience and expertise of the international community. Such an investigation must be followed by the application of appropriate criminal sanctions against the individuals responsible.

This report is based on Human Rights Watch interviews in Guinea in January, February, and March 2007 with officials from the Guinean Ministry of Justice; the Guinean Ministry of Security; the Guinean military; diplomats; journalists; representatives from the United Nations (UN), international nongovernmental organizations, trade unions, and local civil society organizations; as well as victims of and eyewitnesses to human rights violations in Guinea. The names of victims and other witnesses have been omitted to protect their identity and to ensure their privacy.

Recommendations

To the Government of Guinea

- Publicly acknowledge and condemn excessive use of force on the part of state security forces, including the police, the gendarmerie, and the military, during recent demonstrations, including the June 2006 nationwide strike.

- Create an independent body with full authority to investigate and prosecute abuses that occurred during the January-February strike, as well as similar abuses that occurred during the June 2006 strike. The mandate should include the assessment of all state conduct in accordance with the rights set out in the Constitution and in the international human rights treaties to which Guinea is a party. Such a body should have subpoena power as well as the power to protect witnesses. In particular, the independent structure created should draw upon the expertise of the international community through the involvement of members of the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- Immediately investigate via the independent body put in place, and then prosecute in accordance with international standards, crimes committed by state security forces during the both the January-February 2007 and June 2006 nationwide strikes, including murder, rape, assault, and theft. Civilians involved in committing serious abuses-such as the lynching of security forces-should be similarly investigated and punished.

- Thoroughly review-and as necessary revise-the training curriculum for police and other security forces to ensure comprehensive training on human rights issues including legal and appropriate interrogation techniques, crowd control, and appropriate use of force. Provide comprehensive training for police officers on the conduct of investigations. All training must be consistent with international human rights standards, such as the United Nations Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials.

- Compensate victims of strike-related abuses adequately and speedily.

- Provide training to security forces and members of the National Communication Council regarding freedom of the press; Convene a seminar for dialogue between officers of the police, military, and gendarmerie and local journalists.

- In the event of a declared curfew, take all steps necessary to ensure that the population is aware of the hours of the curfew and that those found in breach of the curfew are treated in accordance with the law.

To the United States, France, the European Union and other International Donors

- Call publicly and privately on the Guinean government to create an independent structure charged with investigating the abuses described in this report. In particular, the structure created should draw upon the expertise of the international community through the involvement of members of the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- Maintain pressure on the Guinean government to investigate, and where applicable punish in accordance with international standards, those responsible for crimes during the January-February 2007 and June 2006 nationwide strikes, including, murder, rape, assault, and theft.

- Provide financial and other support to local nongovernmental organizations to improve the monitoring and documenting of abuses committed by security forces and to undertake advocacy at a national level.

To the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights

- Continue to provide technical and financial assistance to Guinean civil society organizations currently trying to document strike-related abuses.

- Provide staff, technical assistance, or other resources to ensure the proper functioning of an independent commission or special court put in place by the Government of Guinea to investigate and prosecute strike-related abuses.

Background

Guinea gained its independence from France in 1958, after being the first and only colony to opt for complete independence with no integration into a community of French overseas territories. The campaign for independence was led in part by a charismatic former union leader, Sékou Touré, who first came to prominence in the 1940s and 1950s after leading a post-war strike against the French colonial administration. He would go on to rule Guinea from independence in 1958 until his death in 1984. Embracing a mixture of pan-Africanism and Marxist ideology, Touré transformed Guinea into a one-party dictatorship in which free expression and political opposition were ruthlessly suppressed. As with political parties, union membership under Sékou Touré was restricted to a single, state-sanctioned entity.[4]

Under Sékou Touré and the state terror and informant apparatus he put in place, thousands of intellectuals, government critics, and perceived political rivals were detained in the notorious Camp Boiro, Guinea's Gulag, where they were systematically tortured and killed. Their fate was determined not by an independent judiciary, but by the Revolutionary Committee (Comité révolutionnaire), a body consisting of senior political officials and relatives of the president. Due to the atmosphere of paranoia and repression that prevailed in the Sékou Touré era, thousands of Guinean intellectuals fled the country, only to return (if at all) after Sékou Touré's death in 1984. Some have estimated that as many as one million Guineans fled to neighboring countries such as Côte d'Ivoire, Sierra Leone and Liberia.[5] Although it ended nearly a quarter century ago, Sékou Touré's twenty-six-year reign left an indelible mark on Guinea, and a legacy of fear and mutual distrust for those attempting to call their government to account.

When Touré died in 1984, the army swiftly seized power and Colonel Lansana Conté, Guinea's current president, emerged to assume control. Within days, the constitution was suspended, Sekou Touré's PDG party (Partie Democratique de Guinee) and the National Assembly were disbanded, and military rule was instituted under the name of the Military Committee for National Redress (Comité militaire de redressement national, CMRN). The new military government declared the protection of human rights to be one of its primary objectives, released political prisoners from Camp Boiro, and encouraged the Guinean diaspora that had fled under Sékou Touré's rule to return. Effectively continuing Touré's one-party rule, all activities by political parties were banned. Although there was a decrease in the scale of rights abuses compared to the Sékou Touré era, extrajudicial executions, disappearances, torture, arbitrary arrests of students and government critics, and the killing of peaceful demonstrators continued during the period of military rule that ended in the early 1990s.[6]

Following a referendum at the end of 1990, Guinea endorsed a new constitution guaranteeing a broad range of human rights, and the military government was officially dissolved. However, the process of Guinea's transition to a multiparty system would not be completed until the first legislative elections in 1995. Lansana Conté won elections in 1993 and 1998 that were regarded by international observers as flawed due to allegations of vote rigging, disruption of opposition party meetings, and arrest and detention of opposition figures.[7] Conté was re-elected for a third term in 2003 after an amendment to the constitution was passed allowing the president to run for an unlimited number of terms.[8] Most opposition parties boycotted the 2003 election, and Conté won against a single, relatively unknown candidate.

The human rights record of the Conté regime after the transition to a multiparty system in the mid 1990s has continued to be marked by abuses and repression, including excessive use of force against unarmed demonstrators, torture of criminal suspects, including children, in police custody in order to extract confessions, prolonged pre-trial detention, the arrest and detention of opposition leaders and supporters, and harassment and arrest of journalists.[9] The Conté government has largely failed to tackle the impunity that often accompanies these serious human rights abuses, particularly abuses committed by security forces.

In recent years, Conté's health has deteriorated. Suffering from acute diabetes, he flew to Switzerland on at least two occasions in 2006 for emergency medical treatment, creating increasing speculation both within and outside of Guinea as to whether his condition allows him to govern effectively.[10]

There has been a parallel deterioration in the state of the Guinean economy. Despite vast reserves of iron, bauxite and precious stones, Guineans are among the poorest people in the world, currently ranked 160 out of 177 on the United Nations development index.[11] Guinea's economy is plagued by corruption and inflation. In 2006, corruption watchdog Transparency International ranked Guinea as Africa's most corrupt country.[12] Inflation, which hovered around 4 percent in the late 1990s has skyrocketed, and currently hovers around 30 percent, dramatically eroding the purchasing power of most Guineans.[13] Economic growth, which averaged about 4.5 percent in the 1990s, has slowed since 2000 to an average rate of about 2.5 percent a year.[14] In 2002, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the African Development Bank suspended economic assistance to Guinea due to poor economic and political governance.[15] In 2003, the European Union (EU) invoked Article 96 of the Cotonou Agreement to suspend all but humanitarian assistance to Guinea due to human rights concerns.[16]

Guinea's economic meltdown has brought with it political chaos, resulting in sacked prime ministers (the latest is the sixth in 10 years) and chronic cabinet reshuffling (as of April 2007, 172 different individuals have served as minister in Conté's cabinet).[17] Many observers attribute the disorder in part to rival clans vying for succession after Conté's time in office is finished.[18] Guinea's military is rumored to be deeply divided along both generational and ethnic lines, and a military takeover is feared in the likely event that President Conté does not finish out his term, set to expire in 2010.

A Series of Strikes and the Growth of the Trade Unions

As Guinea has slid deeper and deeper into economic and political chaos, there have been an increasing number of demonstrations by trade unions and other civil society organizations to protest economic deterioration and poor governance. In 2006 Guinea's two largest trade unions emerged as significant players in Guinea's political future by organizing two nationwide strikes-in February and June 2006-that effectively paralyzed the country for several weeks, shutting down schools and businesses.[19] Although the unions formally represent only a small portion of Guinean workers and the Guinean population, the strikes were widely observed by the general population across the country, both in the formal and informal sectors.[20] Most Guineans observed the 2006 strikes not by participating in organized rallies or marches in the street, but by staying home, and refusing to work. During the strikes, nearly all economic activity shut down, and transportation was nearly impossible for ordinary Guineans as most taxi drivers observed the strike.

The union's demands during the 2006 strikes were essentially economic in nature: lower prices for basic commodities such as rice and gas, and higher salaries for workers. In each instance, the strikes were "suspended" by the unions pending the government's fulfillment of promises for various economic reforms, promises which, according to union and other civil society leaders interviewed by Human Rights Watch, were never fulfilled.[21]

Though the protests of 2006 were largely peaceful, if at times unruly, security forces responded to these strikes, particularly the June 2006 strike, with excessive and inappropriate use of force. In the course of a June 2006 crackdown, police and other security forces were involved in murder, rape, assault, and theft of both unarmed protestors and bystanders alike.[22] According to research by Human Rights Watch, at least 13 protestors were killed by security forces.[23] There have been no prosecutions of members of Guinean security forces for abuses committed during the June 2006 strike.

Strike Three; The Tipping Point

On December 16, 2006, Guinea's President Lansana Conté traveled to Conakry's central prison with his motorcade and personally secured the release of two close allies charged with embezzlement from Guinea's Central Bank, reportedly telling his entourage, "I am justice."[24] The first, Mamadou Sylla, is alleged to be Guinea's richest businessmen and had been arrested at his home earlier that month in connection with his allegedly unlawful removal of millions of dollars from the Central Bank.[25] The second, Fodé Soumah, former Central Bank deputy governor, was also arrested for alleged complicity in the affair.

For the unions, who had "suspended" the 2006 strikes pending government economic reforms, the incident was the final straw.[26] Several weeks later a new strike notice was issued. Citing executive interference in the affairs of the judiciary and the dire economic situation in the country, the unions called for an unlimited general strike as of January 10, 2007 until such time when there was a "return to the rule of law."[27]

Unlike the strikes of 2006, which focused almost exclusively on economic reforms, union demands in January 2007 were more overtly political, and included the nomination of a consensus prime minister with power to form a consensus government; review and renegotiation of certain mining, fishing and forestry agreements; and putting an end to corruption by prosecuting individuals charged with embezzlement of public funds. Union and other civil society leaders explained that they could no longer ignore the fact that the problems behind Guinea's economic woes were essentially political in nature.[28]

After the strike began on January 10, 2007, activities in Conakry and major towns across Guinea ground to a halt. The first few days of the strike were relatively peaceful. As schools, shops, and markets were shut, additional police patrols deployed around the streets of the capital Conakry and there were sporadic clashes with rock-throwing "youths."[29] As the strike wore on, however, and the standoff between the unions-who were increasingly clear that their primary and non-negotiable demanded was that President Conté cede many of his powers to a new consensus prime minister-and the government intensified, security forces engaged in a brutal crackdown on unarmed demonstrators.

During the first four weeks of the strike government security forces, including the police, the gendarmerie,[30] and the presidential guard, also known as the "Red Berets," would be responsible for the deaths of approximately 100 demonstrators; the wounding of hundreds more by gunshot; the beating, robbing, and arrest of scores of demonstrators and bystanders; and the harassment, arrest, and abuse of union and other civil society members. Human Rights Watch conducted detailed interviews with 79 victims and witness to the brutality that took place during the first four weeks of the strike, a selection of which are provided below.

Lethal Use of Force

During the first week of the strike most protestors were peaceful. There were no large-scale organized rallies or marches, and most demonstrators chose to observe the strike by staying at home and refusing to work. However in some locations, demonstrators burned tires and cars, and threw rocks, both at security forces as well as taxis and other commercial vehicles attempting to break the strike.[31] Reports as to the manner of the police and gendarmes' intervention indicate that the response was generally appropriate, and their efforts to disperse demonstrators consisted largely of non-lethal means such as tear gas and shots fired into the air. There were no reports of deployment of the presidential guard.[32] As the strike continued past its first week, however, the intensity of confrontations between protestors and security forces increased, as described by an 18-year-old shoe shiner from one of Conakry's outer suburbs,[33] who reports being shot by police on January 18, 2007:

The day I was shot, I was going out to try to find some rice to eat. It was around noon. Once I made it to the main road, I saw a group of youths protesting on the street. Some of them were throwing rocks at a large group of nearby policemen, who immediately started shooting at us. I felt a sharp pain and looked down and saw blood flowing from my leg and I fell down. I couldn't walk. A group of youths picked me up and started to carry me to the hospital. But a group of police started firing straight at them and they panicked, dropped me on the ground, and ran off. The police came up and I heard one of them say they should kill me. Then one of them kicked me in the face and I felt the blood start to run. The police left me there and a little while later another group of youths took me to the hospital.[34]

During the same period, one resident of Conakry's Hamdallaye neighborhood interviewed by Human Rights Watch described being shot by the police in front of his house as he stepped outside to make a telephone call.[35] The victim reported that a policeman sitting on top of a passing truck fired directly at him, hitting him three times in the hip and thigh.[36] Another witness in the same neighborhood described seeing a rock-throwing protestor shot in the foot as a group of gendarmes fired at the ground in an attempt to disperse protestors.[37]

"The Human Tide"

While as many as a dozen deaths were reported in the first 10 days of the strike,[38] the death toll would rapidly escalate on Monday, January 22, when union leaders, civil society coalitions, and other community groups mobilized tens of thousands of demonstrators for a march from Conakry's suburbs into central Conakry in which many dozens of protestors were killed by security forces and many more wounded by gunshot.[39] Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch referred to the stream of protestors as a "human tide," some of them claiming it was the single largest crowd they had ever witnessed in Guinea.[40] Protestors interviewed reported that when leaving their houses that morning, they felt that the day would be decisive, one way or another. As one protestor put it, "When we came out on Monday, we were determined to change the system in place. It's been 48 years since independence, and we have nothing."[41]

The goal of most demonstrators was to reach the headquarters of the National Assembly, known as the People's Palace (Palais du Peuple), a dozen kilometers from Conakry's suburbs.[42] Though there were sporadic instances of rock throwing in the outer suburbs during the early morning hours, as the marchers coalesced into streams flowing down the main arteries towards central Conakry, those interviewed by Human Rights Watch-both protesters and international observers-reported that protestors were unarmed and marching peacefully.[43] Marchers reported that they carried signs and banners bearing slogans such as "Down with Conté," "We want change," and "Down with the PUP."[44] Many protestors told Human Rights Watch that order among the marchers was kept by informal overseers, one of whom explained his role as follows:

During the march on January 22, I was one of the stewards. Our role was to keep marchers from throwing rocks and engaging in acts of vandalism. We wanted to improve upon the marches of January 17, where some youths had thrown rocks and wanted to insult the police. And even that morning, near Bambeto,[45] there had been a group throwing rocks, so it was important to calm things down. Those playing this role were just organized informally, and were older guys from the neighborhood who the youth respected. We didn't get orders from on high.[46]

As the protestors made their way into central Conakry, there were a number of encounters with large groups of police and gendarmes stationed at various strategic crossroads. Though police and gendarmes did in many instances attempt to disperse the advancing protestors using tear gas and shots fired in the air, eyewitnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch report that in several instances security forces fired directly into the advancing crowd when non-lethal means failed to stop the advance, resulting in deaths in the neighborhoods of Hamdallaye and Dixinne.[47]

Many protestors interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that, rather than fleeing the gunfire, crowds of demonstrators picked up the bodies of the dead, and continued their march towards security forces while carrying the bodies above their heads.[48] The following account is typical:

When we arrived in Hamdallaye, there were lots of police and gendarmes and there was lots of firing in the air and lots of tear gas. But it wasn't frightening people, so they fired straight into the crowd. There was no stone throwing at Hamdallaye. Nothing. Two died there that I saw. One was hit in the forehead, and the other in the chest. I don't know if it was a policeman or gendarme who fired those particular shots. We took the bodies and put them on a piece of corrugated tin and carried them on our heads. The security agents backed off as we approached with the bodies and we passed forward towards Bellevue.[49]

Another witness interviewed by Human Rights Watch, a 38-year-old teacher in a Koranic school, described an encounter in Dar-Es-Salam, one of Conakry's outlying neighborhoods, between police and demonstrators:

That morning, I went down to the main road to see what was happening. When I arrived, there were people on the street chanting, "Down with Conté," "Down with the regime," and "Down with dictatorship." There were no rocks being thrown. I saw a police mini-bus come up the street. It was loaded with officers, I don't know how many. There was one sitting in the back. I saw him point his gun at the crowd and fire a single shot. It hit a protestor, a young man in the face and killed him. They did not fire any gas that I saw. At that point, the crowd got really angry and started to move toward the bus, and the policemen in the back fired in the air to scare people, and then they drove off. I saw some of the demonstrators take blood from the dead body and smear it on their faces.[50]

Ultimately, security forces stationed at many strategic crossroads chose to retreat in the face of the peacefully advancing demonstrators, whose numbers were increasing by the hour.[51]

The November 8 Bridge

Conakry is situated on a long, narrow peninsula, at points barely wider than 500 meters across. To reach the National Assembly from Conakry's suburbs, nearly all major road arteries pass near a narrow choke point, known as the "November 8 Bridge." On January 22, 2007, dozens of security forces, including the police, gendarmes, and members of the presidential guard, were stationed in a line across the bridge, creating a barrier to any advance beyond the bridge to the National Assembly building or anywhere else in the city center.[52]

As groups of protestors reached the November 8 Bridge, security forces attempted to disperse them with tear gas and with shots fired in the air.[53] When that failed, witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces, in particular the Red Berets, fired directly into the crowd.[54] Journalists and officials from humanitarian organizations interviewed by Human Rights Watch estimate that between 10 and 20 individuals were killed at the bridge, though many more likely subsequently died due to injuries suffered.[55] One foreign diplomat who was able to view the scene at the bridge, provided the following account:

From what I saw of the march of the 22, security forces were firing on an absolutely peaceful march. The protestors had no stones or arms of any kind. At first, security forces did use tear gas to try to push people back. But then the first wave of protestors that was advancing toward the bridge got closer and closer. One protestor was carrying a Guinean flag. A group of protestors got down on their knees in a non-threatening position in front of the soldiers. But the soldiers fired at the one in the first row holding the Guinean flag, as he stood there on his knees. They literally fired directly into the crowd. The Red Berets were firing, but so were the police and gendarmes. Several were wounded at the bridge, hit in the stomach, so they couldn't have been firing in the air. I saw police kick those who were already lying prostrate wounded on the ground, so the security forces were clearly over-excited. Groups of protestors would disperse in all directions only to come back again. I don't know why the demonstrators kept advancing. Maybe they thought because they weren't armed, they wouldn't be hurt.[56]

As security forces fired into the crowds approaching the November 8 Bridge, many demonstrators attempted to flee. Eyewitnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch report that security forces stationed at the bridge went so far as to target fleeing unarmed demonstrators who could in no way pose a threat to their safety. One demonstrator described the situation as follows:

As we neared the bridge, we were chanting, "We don't want Conté anymore." We also had a Guinean flag. We had no stones, no arms of any kind. Our only weapons were little tree branches that we were waving above our heads. Around 2 p.m., we arrived at the bridge. There were police, gendarmes, and Red Berets there. The police were there in strong numbers. There were fewer Red Berets, but I tried to stay closer to the police because the Red Berets were firing more. I saw the Red Berets firing straight into the crowds and several people fall on the ground. We panicked and tried to flee. As my friend was trying to climb a wall into a nearby cemetery to get away, someone fired and hit him in the shoulder. He fell town and tried to climb again, and they shot him again in the lower back side. I knew if I tried to climb the wall they'd shoot me too, so I ran towards the police because they weren't firing as much and they captured me. They struck me with their rifle butts on the back and arrested me.[57]

Other demonstrators who managed to flee beyond the range of security forces firing from the bridge found themselves trapped as their advance away from the bridge was met by groups of police and gendarmes coming from the other direction. Pinned down between two sets of security forces, many fleeing demonstrators attempted to hide in neighboring houses, Conakry's central mosque, and even Camp Boiro.[58] One witness described being caught by security forces while trying to hide:

After I fled from the bridge, they had barred most of the roads, so lots of people were trapped. Everywhere I looked, the police and gendarmes were beating and arresting people. I ran as far as the great mosque, and then I fled into a house with a small group of protestors to take refuge. The father of the house where we were staying told us to stay there, but later he came back with about fifteen green berets.[59] They started beating the protestors in the house with rifle butts and clubs. They were saying, "Do you want a change or not?" We understood that if we said, "We want change" they would keep beating us, so we said, "No, we don't want change," and they let us go.[60]

"The Day of Hell"; Treating the Wounded in Conakry's Hospitals

As the body count increased over the course of the strike, scores of dead and wounded flooded into local hospitals. Medical personnel on duty on January 22, 2007, the single heaviest day of deaths and injuries during the entire six-week crisis period, described the difficulties of treating the unexpected influx of wounded:

Monday the 22 was the day of hell. We simply weren't prepared for it. Early that day we saw smoke near Hamdallaye[61] and we knew it would be bad. Between 9:30 and 10 o'clock, we saw the first crowds approaching. There were already two bodies being carried by the protestors. We asked where they had been killed, and they said "at Kerfalla's house."[62] Ten minutes later all hell broke loose. Injured were flowing in at three to four per minute. There was a crazy terror throughout the hospital. We were seeing lots of head wounds. Not just simple bullet wounds, but entire heads exploded. The wounds we saw were more serious than I ever saw during the rebel attacks in the forest.[63] The Red Cross and the youths were sending bodies, especially from the bridge using plastic mats, mostly of wounded young. I saw doctors crying, saying, "Why are they firing on their own people?" We were working on patients laid out on the ground in the hospital. There was literally nowhere else to put people. And there was nothing at the hospital in terms of supplies. Many died before we could even treat them.[64]

In what was a blatant instance of excessive use of force against injured persons, several witnesses, including medical personnel trying to attend to the wounded, described seeing the security forces in green uniforms firing a tear gas cartridge directly in front of the emergency room as patients were being treated:

At one point, they launched a tear gas cartridge into the hospital courtyard, right in front of near the emergency room where we were treating people. A group of doctors went out to confront them and said, "Go ahead, kill us too. Kill all of us." We told them, "You are Guinean like us. Come in and we'll show you what you have been doing since this morning." I wanted them to come in to see the wounded but they lowered their weapons and they refused. There were no protestors in the courtyard when they fired the gas, and it wasn't a stray gas cartridge. Everyone knows that area is the emergency room where protestors were being treated, so I think it was fired on purpose. Later on, a Red Beret did come into the hospital because his brother, a protestor, had been killed. First he was furious, saying that he was going to avenge his brother's death. But then he started to cry, saying, "We told them not to fire. We told them not to fire."[65]

Beating, Arrest, and Robbery of Protestors and Bystanders

Throughout the first four weeks of the strike, as protestors dispersed from major roads into surrounding neighborhoods, police and gendarmes pursued them, at times for up to over a kilometer from the main road where the demonstrations were taking place. Human Rights Watch interviewed dozens of eyewitnesses who allege that, as security forces entered the neighborhoods, they rampaged through the homes and businesses of local residents, beating and robbing not only the protesters, but many others including women, children, and elderly men who had not participated in the protests. One man of 47 told Human Rights Watch that the police broke into his house and robbed him, just as he was planning to leave for eye surgery in Dakar, Senegal:

On Friday, January 26, around 10:30 a.m., I was lying down in my one-room house with no lights on. Around five police broke the door down. One of them said, "Kill him." I replied, "You're going to kill a sick person?" They pulled an iron bar off the door and hit me with it on my back. Then they searched the house. They stole eight million CFA [West African CFA francs, about US $16,000] that I had in a bag to go get eye surgery in Dakar. Then they grabbed me and tried to take the phone from my pocket. I said, "Please leave me this, you took everything else." Then they hit me on the left temple with a rifle butt. Before this happened, I had been trying to get to the airport to go to Dakar for treatment, but it wasn't possible to get there due to all the gunfire. Now I don't know how I'll ever get treated.[66]

In the course of their expeditions into the neighborhoods, security forces arrested many individuals having little to do with the protest. Many of those arrested later interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they were taken to police detention facilities, beaten, held for several days, and freed only after family members bribed police officers to secure their release. A man in Conakry's outer suburbs who had not taken part in the strikes described his arrest at his home on January 17, 2007:

The day the police arrested me, I was sitting home with my mother, wife, and baby. Around two o'clock that afternoon, my wife screamed, "Get up, soldiers are coming!" Just then, two tear gas cartridges were fired into the courtyard, and about fifteen policemen burst in. I think they were from the CMIS.[67] They were all dressed in black. As they burst in, my mother passed out and fell down on the ground from the stress. I heard them saying in Sousou,[68] "Let's go, let's go, they have money," and one of them fired four times in the air with his rifle. I stood in the doorway to the house and didn't want to let them through, but they pushed me and we got into a tussle. One of them hit me from behind with a rifle butt. Another slapped my wife, who fell down holding our one-month-old baby. Then one of them beat me on the ground with his pistol. They hauled me down to the main road and threw me in their truck and took me to the police station in Bellevue. The whole way there they were kicking me and slapping me. At the station, they handcuffed my hands under a bench and struck me thirty times or so with their boots and fists. They left me handcuffed like that for two days. My mother called my cousin who is a Red Beret, who came to Bellevue to free me. They paid 400,000 francs [Guinean Francs, about US$67] to free me. I later learned that after my arrest they stole my cell phone, my camera, 100,000 francs [Guinean francs, about US$17], a radio, along with my wife's clothing and some food from our house. I don't know why they chose our house, but it's not the only one in the neighborhood they hit. Since then, I have decided I might as well strike and march with everyone else, because if they are going to kill you, they are going to kill you, even inside your own house.[69]

A 58-year-old teacher whose son was killed on January 22, described his arrest during his attempt to find his son's body:

On Monday the 22, around 10:30 a.m., my son's friend came to tell me my son had been hit by a bullet and was dead. I wanted to get the body, but when I got to the main road I was told that the protestors had taken it away as part of their march, so I decided to follow the march in the hopes of finding my son's body. At Donka, I was told that my son's body had been abandoned near Cameroun.[70] By this time, many protestors were fleeing in the opposite direction, but I pressed forward. Near the CMIS police station, there was a group of policemen.[71] They swept me up with another guy. Then they threw a couple of young kids into the truck like sacks. One policeman they called "Method" came and rapped me on the head and then ripped off my robe. He searched me and stole 200,000 francs [Guinean francs, about US$33] and my cell phone. I arrived at the police station practically naked. It was the CMIS. They took our names, and then put us in a cell. There were twenty-five people in a cell less than six meters squared. It was full of urine and feces. They didn't interrogate us, but just wanted our name and neighborhood. Later we were transferred into a larger common room with around ninety-five people in it, all as naked as earthworms. The least noise and the police would come in and hit people with batons. There were many wounded and swollen protestors there. They were interrogating the union members next door.[72] I recognized the faces of some of them as we were being transferred. Later we were transferred to a third room where we spent the night. I was freed the next day.[73]

Harassment, Arrest, and Abuse of Members of Civil Society

Throughout the strike, leadership at the highest levels of government, including the executive branch, together with Guinean security forces engaged in what appeared to be an organized attempt to intimidate and silence union and other civil society leaders.

On January 13, members of a civil society coalition, the National Council of Guinean Civil Society Organizations (Conseil National des Organisations de la Société Civile Guinéenne, CNOSCG), were at their headquarters preparing for a march that was scheduled to take place on January 15.[74] Youth members assembled there to paint signs and banners for the march with various slogans such as: "We are fed up, we want change," "We are hungry, we want bread," and "We have no water, and no electricity."[75]

CNOSCG members interviewed by Human Rights Watch report how that afternoon, a group of seven or eight policemen burst into the courtyard, arrested seven of those preparing the signs, and took them (along with the signs) to the central police station, where they were interrogated and thrown into a cell with routine criminal suspects before being released late that night after the intervention of civil society leaders.[76] The following day, January 14, the governor of Conakry issued an edict banning all street demonstrations.[77] The march planned for January 15 was canceled, with the head of CNOSCG, Ben Sékou Sylla, stating that he would not "send the population to the slaughterhouse."[78]

On January 17, leaders of the CNTG and USTG trade unions attempted to walk from CNTG headquarters to the National Assembly building to deliver a letter containing their demands to the president of the National Assembly.[79] Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch describe the march as peaceful, with union members marching in the lead, and youths from downtown Conakry behind them.[80] Approximately halfway to the Palais du Peuple, however, police and gendarmes who had been following the marchers fired tear gas and warning shots to break up the march, and arrested union members. One union member described the scene:

Suddenly, police were firing tear gas everywhere, and started hitting people with clubs. Marchers fled in all directions. From what I saw, the young were the biggest targets of the beatings. In total, seven union members and one youth were arrested and taken to the CMIS police station. When those of us who weren't arrested managed to make it to the National Assembly, Somparé received us and asked us what the matter was.[81] We refused to speak until our comrades were released.[82]

Those taken by the police reported that they were released several hours after their arrest and driven to the Palais du Peuple, allowing the letter to the president of the National Assembly, which was being carried by one of the arrestees, to be delivered.[83]

Later that day, union leaders report that they were summoned to Camp Samory, an army base in central Conakry, where President Conté threatened to kill them.[84] In an interview with Human Rights Watch, one union leader described the encounter between the union leadership and President Conté:

We were taken into the president's office. Chantale Cole was there, along with Fodé Bangoura and Kerfalla, but only Chantal Cole was close to the president.[85] She had a list of our demands in her hand. There were Red Berets standing all around the perimeter of the room. Then the president said, "You have taken off my shirt. Only my pants are left. You have humiliated me, but I will kill you. If I kill you, I won't have to answer for it to anyone, and no one will be able to do anything about it. Should I cut your head off, or just make you disappear? I could make you disappear and no one would ever know. If I lift my little finger, my guards will cut you up and eat you in front of me. Sooner or later, I will kill you. I'm just thinking about how I'm going to do it."[86]

According to the same union leader, after this speech, President Conté insulted them, and then allowed them to go home.[87]

On January 22-the day tens of thousands of Guineans attempted to march from the suburbs to the Palais du People, and the day of the highest casualties-the headquarters of one of the two principal trade unions leading the strike, the CNTG, was attacked by a combined group of police and Red Berets. According to union leaders and others present in the building, the Red Berets first arrived that morning, led by Ousmane Conté, the son of President Conté.[88] Union leaders told Human Rights Watch that the security forces then broke down several doors on the upper level of CNTG headquarters and arrested six youths upstairs, who were taken to camp Koudara, where union members reported that they were each given 40 blows with a club before being released.[89] Most union leaders were downstairs at the time of the first invasion, several of them observing Ousmane Conté from a window.[90]

Later that afternoon, union members report that Red Berets and police returned to CNTG headquarters in greater numbers, with the police storming the top floor from the front of the building, and the Red Berets storming the lower floor from the back side of the building.[91] One union member described the arrival of the police on the upper floor of CNTG headquarters:

I was on the top floor with one of the union leaders when the police came. Around 5 p.m., we heard lots of noise and decided to shut the door to the office we were in, and then hide in the bathroom connected to that office. There were around ten of us in there. Soon after, the police broke open both sets of doors and found us in the bathroom. Three policemen came into the toilet area. One of them looked like he was going to throw a tear gas grenade in and shut the door. But another policeman held his arm. We lifted our hands to surrender and they searched us. They took my money, 225,000 francs [Guinean francs, about US$37], and my cell phone. Then they beat us with clubs, saying, "You want to make a mess of things, we're going to mess you up. We're going to kill all of you." They took the secretary general and took his glasses off and started to beat him all over with clubs. Then suddenly the three of them ran out and left us, so we shut the door to the toilet again. But a few minutes later a second group came. Three of them. We raised our hands and they searched us again, and found my second cell phone. Then they beat us again before arresting us and sending us to the truck outside. One of them said, "We're going to kill all of you today."[92]

Union members told Human Rights Watch that as the combined police and Red Beret forces proceeded to ransack the building, overturning computers and smashing office equipment, a group of them converged in a room downstairs containing senior union leadership. One union leader reported her experience as follows:

Around 4:30 p.m., the Red Berets came back. We heard cries and insults outside the room we were in. Then ten or so burst into the room. There was one Red Beret and the rest were police. One of them said, "Fofana is here, Raby is here."[93] Then another said, "It's here that you are planning your coup d'état. We'll give you change." They turned over all the computers and equipment. Seven of them seized Fofana and beat him, hitting him hard in the eye. They handcuffed him with difficulty because of his girth. One of them said, "Stick him with a bayonet, open up his head," and we all screamed, "Oh God!" Then they emptied money from our pockets. They knocked us with their rifle butts as we were exiting. We were hurrying out of the room to avoid the blows. Then they put us in a pickup outside, but the truck was so loaded with union members, it couldn't go up the small hill to get out of our parking lot. So they threw us all out and divided us into four trucks. We were first taken to the central police station downtown. We thought they were going to shoot us. One policeman pointed to Fofana and said, "Who handcuffed him?" But no one responded. By this point, Fofana could only see from one eye because the other was so swollen and there was blood on his face. Many of us cried from the sight of him. We told the police, "He's sick, he has diabetes." One of them said, "We don't care. You wanted change, we'll bring it to you." They took our names, and then put us back in the truck. There were police sitting on the rack above the pickup bed with their feet hanging down near our heads. If any of us moved, they kicked our head. Then they took us to the CMIS police station."[94]

Later that evening, the heads of the CNTG and USTG unions were taken from the CMIS police station to see President Conté at Camp Samory. A union leader interviewed by Human Rights Watch claimed that during this encounter President Conté appeared to have no prior knowledge of the invasion of CNTG headquarters and subsequent arrest of union members, and ordered their release.[95] In all, union leaders reported that approximately 70 union members were taken to the CMIS police station where they were held until around midnight, before being escorted to their homes. A subsequent agreement between the unions, the government, and the Employers' Association (Conseil National du Patronat) signed on January 27, 2007 officially "deplore[d] the invasion, destruction, and ransacking of the Bourse de Travail [CNTG headquarters]…and the arbitrary arrest of union leaders."

Intimidation of the Media During the First Weeks of the Strike

In late 2006, Guinea became the last country in West Africa to allow private radio broadcasting, ending a 48-year-long state broadcasting monopoly when four private radio stations were granted licenses and began broadcasting.[96] Despite this apparent embrace of freedom of expression guaranteed under both Guinea's constitution as well as international conventions to which it is party,[97] during the first weeks of the strike, a number of actions were taken by agents of the Guinean government to restrict the free transmission of information by private radio stations. For example, journalists interviewed by Human Rights Watch report that FM transmission of Radio France International was disrupted by the government on at least two occasions during the strike.[98] On January 15, 2007, in separate visits to the various radio stations, then-serving minister of information, Boubacar Yacine Diallo, reportedly prohibited all private and community radio stations from broadcasting any material relating to the strike.[99] An employee for one of Guinea's four private radio stations that persisted in broadcasting news about the strike told Human Rights Watch that he received a variety of threatening calls from government and anonymous sources during the first weeks of the strike, including from the minister of information himself.[100]

The Strike Outside of Conakry

While the neighborhoods of Conakry were a hotbed of both demonstration and repression throughout the strike, demonstrations were not limited to those in the capital city, or to a particular region or ethnic group. Between January 17 and 23 there were sizable protests in nearly all major towns and regions of Guinea, including Télimélé, Koundara, Dalaba, Pita, Labé, Mamou, Siguiri, Kankan, Kissidougou and N'Zérékoré, and at least a dozen deaths were reported in Labé, Mamou, Kankan, and N'zérékoré.[101] Although Human Rights Watch was not able to conduct an investigation in each of these towns due to time constraints, it did conduct interviews in the central Guinean towns of Mamou, Dalaba, and Labé.

The Case of Labé

Security forces in Guinea's central Fouta Djallon region exercised considerably more restraint during the first weeks of the strike than their counterparts in Conakry, resulting in a significantly lower death toll. In Labé, the regional capital, witnesses report that city-wide marches occurred nearly every day of the strike, with some eyewitnesses and government officials claiming that protestors marched more frequently in Labé than in any other town in Guinea.[102] The majority of these marches were peaceful rallies, with no stone throwing, vandalism, or brutality on the part of security forces.[103] However, on January 17, 2007, a group of protestors ransacked the official residence of the governor along with the private home of the prefect of Dubréka.[104] Demonstrators also attacked the residence of the prefect, where one protestor was shot and killed.[105]

Despite the frequent marching and destruction of government and private property, Labé only registered a single death and a handful of wounded during the first four weeks of the strike. Protestors and government officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch attribute the relatively low death toll to a number of factors, including organization by the trade unions and youth groups to prevent vandalism, and an apparent determination on the part of the governor of Labé to minimize the loss of human life.[106] The governor of Labé provided the following account of the ransacking of his residence:

When my guards called me to tell me that the protestors were in front of my house, one of them was crying saying, "The protestors are going to kill us." I told them not to fire, and to retreat if they had to. As governor, it is my decision to fire or not to fire. Windows and objects can be replaced, but life can't. The soldiers at my house were armed. If I hadn't given the order not to fire, demonstrators probably would have died when attacking my house. But I told them not even to fire in the air, because those bullets can come back down and kill people. If a house like this had been attacked in Conakry, you would have had a lot of deaths.[107]

Others interviewed by Human Rights Watch attribute the restraint shown by security forces in Labé during the first weeks of the strike, at least in part, to a tract that was circulated by a youth group after a protestor was shot in front of the prefect's residence, containing a threat to kill three members of military families for every subsequent death of a protestor.[108]

Response to the Appointment of a New Prime Minister

On January 27, 2007, in a tripartite agreement signed by the Guinean government, the trade unions that called the strike, and the Guinean Employers' Association (Conseil National du Patronat),[109] President Conté agreed to delegate powers to a new consensus prime minister, who, for the first time in Guinea's history, was to be head of government.[110] In addition, the government agreed to take measures to reduce the price of rice and fuel; to ban the exportation of food, fishing, forestry, and petrol products; to allow judicial proceedings initiated against those "preying on the national economy" to continue without hindrance; and to establish a commission of inquiry to investigate abuses perpetrated during the strike. In return, the unions suspended the strike, and several weeks of uneasy calm followed as business and activities resumed across the country, and Guineans waited to see whom President Conté would appoint as prime minister, head of government.

The fragile truce would be short-lived. As the days passed, union leaders grew tired of waiting for an appointment and threatened to resume the strike on February 12 if no one was named. On February 9, in place of a "consensus" prime minister, President Conté appointed a longtime member of his cabinet, Eugène Camara, then serving as minister of state for presidential affairs. The appointment was widely perceived to be a betrayal of the agreement Conté had made with the trade unions, and provoked an immediate and violent response by protestors. One demonstrator recounted hearing the announcement:

We had all been waiting for this announcement. But when I heard it, I almost could not believe it because it seemed like such a flagrant violation of the agreement between the unions and the government. This guy had been part of all the financial problems of this government, had been at the heart of the Conté regime for the last ten years. I was beside myself with anger. I turned off the radio and couldn't listen to the rest. That night, the streets of Conakry filled with protestors. People were screaming, "We don't want him, he's Conté's man," "The government is a liar," and "Conté doesn't give a damn about us!"[111]

Infuriated by the appointment, violent unrest ignited across the country. Human Rights Watch interviewed 36 victims of and witness to the chaos and brutality that took place in the two weeks that followed; a selection of those accounts is provided below.

Almost overnight what had begun as an organized, nationwide strike in mid-January transformed into general insurrection and chaos in which rioters attacked government installations, sacked the private homes of government and military officials (including a house belonging to President Vieira of neighboring Guinea-Bissau), burned tires, and, in at least one neighborhood, exchanged gunfire with security forces.[112] In a few neighborhoods, some individuals took advantage of the chaos to rob their fellow citizens at makeshift checkpoints.[113] Rioters raided and ransacked police and gendarmerie stations as well as the private homes of members of the military, seizing scores of arms in the process.[114] In the course of one of these raids in Conakry, one soldier was beaten to death. One witness described the chaos in the Conakry neighborhood of Hamdallaye:

That weekend, after the announcement of Eugène Camara, it was really the law of the jungle. Right after the announcement, I went from my house to a nearby gas station and saw youths who were stealing money and phones, and beating citizens. Around 6 p.m. the next day, I saw local youths take a guy out of a BMW and chase him away in the same place. On Monday morning, the population ransacked the home of a colonel in the military who lives in the neighborhood, Colonel Cherif. In ten minutes they had emptied the entire house. According to what Colonel Cherif said later, they took sixteen combat rifles and ammunition. There were three soldiers guarding the house at the time who fled. Two of them escaped, but one of them was caught by the population and killed. They left his naked body in the street. The population then set fire to Colonel Cherif's house. On the wall surrounding his house, they wrote "Quitte le Pouvoir''[115] and "Fuck Conté." That day same day, there was an exchange of gunfire between the population and soldiers not far from my house. I don't know if they used the weapons taken from Colonel Cherif's house, or guns people already had. I know of several Red Berets who were hit by bullets in my neighborhood, but I don't know if any of them died. That same day, I also saw a Red Beret squat down, elbow on knee in combat position, fire and hit a boy carrying bread. I think he was twelve or thirteen years old. Most people would flee far off the main road whenever they saw soldiers come, but that kid was unlucky and caught out on the street.[116]

The unrest ignited by the nomination of Eugène Camara was not limited to Conakry. In the weekend that followed Camara's nomination, clashes between civilians and security forces were reported across the country in prefectoral capitals such as Kankan, Kissidougou, Faranah, Labé, N'zérékoré, and Kindia. In Kankan, rioters reportedly attacked the city jail and released prisoners[117] and one soldier was reportedly lynched by a mob after he fired on demonstrators, killing two.[118] In Kindia, according to reports, protestors ransacked the local governor's office and security forces then fired upon the crowd, killing as many as seven people.[119] In all, at least 22 civilians were killed in days immediately following the appointment of Eugène Camara.[120]

In a communiqué, the National Council of Guinean Civil Society Organizations (CNOSCG) condemned the violence and destruction caused by the rioters. In a separate statement, the trade unions called for resumption of the strike starting Monday, February 12. However, it appeared that the unions and civil society were no longer able to control the masses of angry youth. When asked why the rioters did not wait for the trade unions to reactivate the strike and organize a peaceful protest, resorting instead to spontaneous violence and destruction of property, one individual told Human Rights Watch, "The population had gotten ahead of the unions. We weren't following them anymore. Rather, it was for them to follow us. And we didn't need the word of the unions to know that Eugène Camara was not acceptable."[121] On Sunday February 11, an anonymous SMS message was widely circulated from cell phone to cell phone:

The final assault begins tomorrow until the fall of the general. All together. The strategy is to march without vandalism. But wherever the military kills someone, look around there and ransack homes of military families. Send this message to others. Thank you.[122]

On Monday, February 12, youths from Hamdallaye, Bambeto, and other neighborhoods in Conakry's suburbs mobilized with the intention of marching towards the city center. Along the way they threw rocks and clashed with members of the security forces, including police and the military. After nearing the roundabout of Hamdallaye, around which there was a heavy presence of security forces, they were dispersed by security forces who fired tear gas and shot into the air, before turning their guns on the crowd. Victims and witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch described the deaths of several marchers during the course of these events. One witness who participated in the march described the events of that day:

We were thousands on the road that day-people were coming from all over. The youths at the front of the march were armed with rocks, but nothing else. When we got into Hamdallaye, the youths started throwing rocks at the police and soldiers, who started firing tear gas and shooting in the air in return. I saw about fifty armed men; police in black uniform, army in camouflage and about fifteen to twenty Red Berets. They were all working together to stop the youths from advancing. The youths and security forces clashed there for about one hour-the tear gas didn't really bother us because we had cloths soaked and noses packed with gel to absorb the gas. But then, the armed forces started firing into the crowd. When this happened the youths dispersed everywhere to avoid getting shot. I ran into the neighborhood and hid together with about twenty others at the side of a house that was about fifty meters from the main road. We thought we were well hidden and were waiting for things to calm down so we could go back to the road. After about three minutes, we saw a soldier walking into the neighborhood. He was a Red Beret-he was dressed in camouflage and had a red beret. When he saw us he stopped and almost immediately took aim with his gun. As he did this we all bent down. However my friend Thierno was a little slow. I was trying to pull him down. He was right next to me when the Red Beret fired one round hitting him straight in the right side of the head. Thierno's blood flew all over me. I later had to wash it from my shirt. He died right there.[123]

Some protestors were intercepted before reaching the roundabout of Hamdallaye. One witness told Human Rights Watch that his group was forced to flee before reaching Hamdallaye when a group of Red Berets arrived in a truck and fired into the crowd, killing his 26-year-old friend.[124]

Guinea Under Martial Law

In the wake of the violence that exploded after the nomination of Eugène Camara as prime minister, President Conté signed a decree on the evening of February 12, 2007 declaring a "state of siege."[125] In addition to handing significant powers to the military, the decree banned all demonstrations and public gatherings and imposed at 20-hour-per-day curfew.[126] It also authorized the military to detain or put under house arrest anyone deemed to present a danger to public security; to conduct searches of private property for weapons and monitor all means of communication without a warrant; and to exercise draconian restrictions on the media.[127]

House-to-House Searches

Following the declaration of martial law the military used its search powers to go house-to-house though neighborhoods in Conakry such as Hamdallaye and Bambeto.[128] These searches were ostensibly to recuperate the stolen arms that had been illegally seized from police and gendarme stations and the private homes of members of the military during the chaos that erupted after the nomination of Eugène Camara. However, Human Rights Watch interviewed scores of individuals who alleged that in the course of these searches, the military, most notably the Red Berets, engaged in behavior with no possible military or security justification, including theft, assault, murder, and in isolated cases, rape. One woman from Hamdallaye described the search of her house by soldiers on February 14, 2007:

The ones who did this were dressed in camouflage with red berets. When they arrived we all ran into our rooms. I told my children [12, 13 years] to hide under the bed and then I went back to the door, which I'd locked. Soon, they started banging on the door and saying, "Open up you dogs, you bastards, get out, get out!" They were speaking in French, Sousou and a little Pulaar.[129] My door is quite strong and it took them a while to break it down but they finally did. Then five or six of them rushed inside. I can't remember the number; I was so afraid I'd kind of lost my head. When they got inside they were really angry and when they saw me hiding in the bedroom one grabbed me, threw me up against the wall and stuck his rifle into my neck. He was leaning against me pushing my head into the wall so that the others could get to work rifling through our things. They opened all the drawers, lifted up the mattresses and eventually found all the money: 400,000 francs [Guinean francs, about US$67] hidden in a mattress, 25,000 francs [Guinean francs, about US$4] in another place and my watch. As I was standing there with the gun at my neck my cloth wrap fell down, exposing my body, but he didn't touch me. While this was going on I kept saying, "Sorry, please…Allah, Allah." When the others were done, he let me go and then whacked me hard on the arm with his gun.[130]

A businessman in the same neighborhood told Human Rights Watch that on the morning of February 14, a group of soldiers fired their guns at his front gate, broke into his home, and robbed his family at gunpoint, taking cash, jewels, and electronics equipment valued at approximately $20,000.[131] A foreign diplomat told Human Rights Watch that on February 13, his house was forcefully entered and ransacked by a group of eight Red Berets, who stole three cell phones and beat his nephew with a club in front of him and a Red Beret captain.[132]

Another victim interviewed by Human Rights Watch reports that on February 13, she was caught by two Red Beret soldiers while cooking rice for her family and was gang raped:

That morning, we had heard shots fired all over, so nearly everyone was shut inside their homes, but I thought that because I am a woman, I could stay outside just cooking my rice without being bothered by the soldiers. Sometime between noon and 1 p.m., though, two soldiers burst in to the yard. They were wearing red berets and green uniforms, and were armed with guns. They were young, less than thirty years old. They told me to give them money, but I explained that I didn't have any. Then one of them said, "You are the ones opposed to the government. This time, we're going to kill all of you." I could hear other soldiers in the vicinity knocking on neighbors' doors and firing their guns in the air. I offered my rice to them if they would leave me alone, but they said, "We don't care about rice. We already have that." At that point, one of them struck me on the nape of the neck with his rifle butt and bent my arm back to push me into a nearby room. Inside, one of them slapped me and I was knocked to the bed. They told me to undress and one of them fired his gun out the window to scare me. Then one of them ripped off my cloth wrap while the other spread my legs apart. One of them raped me while the other one guarded the door. When the first finished, the second came and the first acted as guard. Before the second finished, I had almost lost consciousness. I was terrified, but at a certain point, I just wanted to die. I was exhausted from fear and I was sure that they would shoot me when they finished. But they didn't. They fired in the air three times before leaving. After they left, I kept screaming until the neighbors came, who immediately went and told the imam nearby what had happened. The imam went out to the main road where a military truck was parked. He told the soldier in charge, "Now they are even raping our daughters!" But the soldier said, "We don't give a damn."[133]

The rape victim told Human Rights Watch that her family reported the incident to a member of the Red Berets, who came to the house to investigate:

The Red Beret who came said they were doing inspections in the neighborhood because there were people wearing military uniforms going around doing bad things, but who were not members of the military. However, I don't believe that explanation because my neighbors saw the soldiers who invaded our neighborhood arrive that day in a military vehicle on the main road not far from my house. They can't claim that criminals stole military uniforms and military vehicles.[134]

At least one other case of rape by security forces appears to have occurred during the state of siege in the same neighborhood.[135]

Curfew

The curfew imposed by the martial law decree of February 12, 2007 originally allowed circulation only between the hours of 4 p.m. and 8 p.m., but was relaxed starting February 14 to allow circulation between noon and 6 p.m.[136] The shifting hours of curfew during the first days under martial law appeared to cause confusion among a number of witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, potentially placing them in a dangerous position vis-à-vis security forces. Although the martial law decree said nothing about the penalty for being found outside during curfew, in practice the consequences for those found outside could be serious. One man suffering from paralysis in one leg told Human Rights Watch that he was beaten by Red Berets after being found outside during curfew, after all of his neighbors were able to escape on foot.[137] Human Rights Watch interviewed two victims, girls of 13 and 18, who report that they were shot by security forces on February 13 at approximately 3:30 p.m.[138]

Other victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch report being shot by security forces even though they were outside during permitted hours of movement. One victim, a boy of 13, described being shot by police on February 15 around four in the afternoon:

There were six of us boys sitting on the rocks outside the house overlooking the main road. Three of them were my age, but the others were our younger brothers. We were telling stories about our recent trips back to the village. We had been going out every day at the same time after curfew ended to get outside after being in the house all day. There weren't many people out, but there were some people pumping water. We had been sitting out there for a long time when we saw a blue Mercedes coming down the road from Bambeto.[139] No other cars were on the road. One of the kids in my group yelled, "The soldiers in that car are aiming at us!" I got up to run, but at that instant two of us were hit, both me and my cousin Mamadou. The bullet hit me on my left arm.[140]

Other witnesses report that the military seemed less interested in whether they were circulating inside or outside of curfew than in robbing them of their valuables. Two witnesses, drivers of a heavy-transport truck making its way to Conakry from N'zérékoré carrying large quantities of palm oil told Human Rights Watch that they were robbed and assaulted by two groups of soldiers, both inside and outside of curfew, on February 13. The military authorized them to leave Coyah, about ninety kilometers from Conakry, at 4 p.m.:

At around 7 p.m. we arrived at the Cosa roundabout in Conakry and I saw a checkpoint of soldiers dressed in camouflage with camouflage helmets who ordered me to stop. Their white pick-up was parked next to them. A few of them told me they were going to seize my truck and take it to a military camp. They told me that I had to give them 500,000 francs [Guinean francs, about US$83]. After a few minutes, I gave them the money, including the 500,000 francs. I knew that if they took me to the camp we'd lose the merchandise and maybe the truck, so I guess it was a small price to pay. After giving them the 500,000 francs they ordered me to give them five jerry cans [25 litters each] of palm oil, which I did. At that moment, a Nissan Pajero four-by-four that was passing by stopped and the soldiers loaded the palm oil into the car. I didn't see if the driver was a soldier, but noticed that the license began with "VA" which is what official state plates begin with.[141] Then, three of the soldiers said they would get in the truck so as to escort me a kilometer or so to the car park. They said they wanted to protect me from any other bad soldiers who might want to steal from me. However, about two or three hundred meters down the road they ordered me to stop, pointed their guns at me and ordered me to give them the rest of my money and more palm oil. I gave them another 200,000 francs [Guinean francs, about US$33] and another three jerry cans of palm oil, at which point one of them shoved a gun at me and ordered me out of the truck. Then the two others searched through the cab of my truck and stole my cell phone and another 100,000 francs [Guinean francs, about US$17]. After this, they fired in the air a few times and told me to go to the garage. By that time, it was past the curfew so my two assistants and I decided to spend the night in the truck. But our troubles weren't over![142]

The driver and his assistant told Human Rights Watch that around midnight yet another group of soldiers approached the truck, ordered the drivers' two assistants to hand them 20 jerry cans of palm oil, and then fired a single shot point-blank, hitting one of the assistants, Ibrahim Bah, in the neck, before driving away. Mr. Bah died several minutes later.[143]

Stray Bullets and Reckless Fire

In the course of the six-week crisis period, security forces shot countless bullets into the air in an attempt to disperse crowds. In many instances, security forces fired bullets into the air even when there were no visible crowds to disperse, presumably in an attempt to frighten demonstrators into remaining in their homes.[144] Situated on a narrow peninsula, land in Conakry comes at a premium, and the city is very densely populated. It was therefore entirely predicable that many of the bullets fired into the air would hit unintended targets when they fell back to earth.

Human Rights Watch interviewed several victims of stray gunfire, including a 34-year-old Koranic school teacher who reports that a bullet pierced the roof of his home and hit him in his left breast while he was sleeping on January 17.[145] Another victim told Human Rights Watch that she was wounded by a stray bullet that entered her back as she bent over to wash clothes on February 13. She was six-months pregnant at the time.[146] One Conakry mother of a 4-year-old child told human rights watch that on February 13 she awoke to find that a bullet had pierced her roof and struck her child in the leg.[147] A man in the Conakry suburb of Matoto described the death of his four-year-old niece by a stray bullet:

On January 23, I was sitting down on the porch. My niece ran across the courtyard to another house. About half way across, we saw her fall down. At first, we understood nothing. We thought she was having a seizure or something. But when we lifted her head we saw blood all over the ground. There was a hole in the top of her head and we realized it was a stray bullet.[148]

Other victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch were injured by what can only be described as undisciplined and reckless fire. One victim, a mother of 41, described how on February 14, she ran inside her house with her children when she saw a group of six to eight Red Berets approaching: