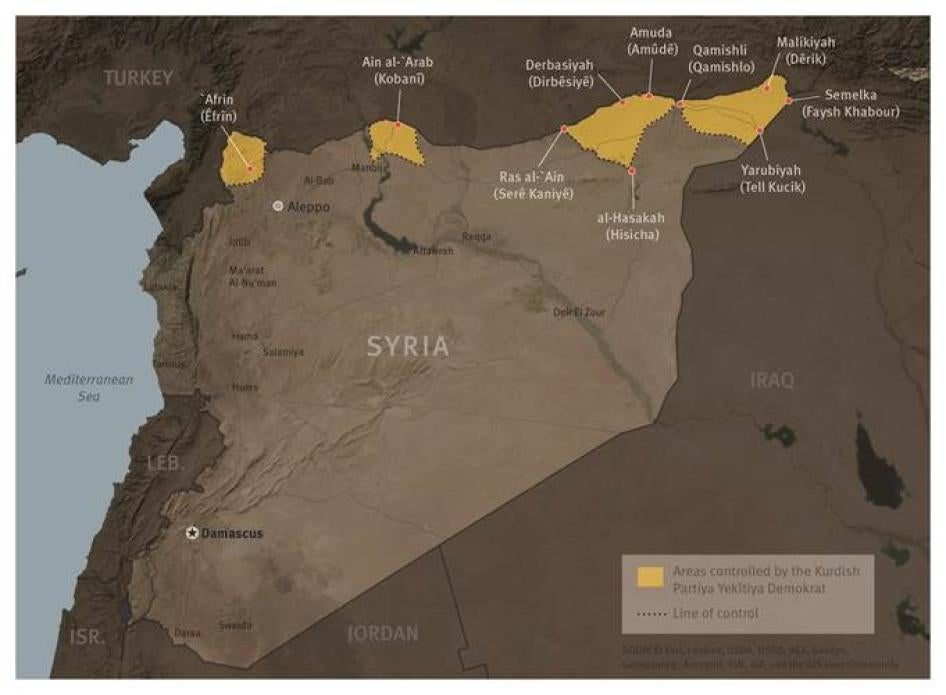

Map of Syria

© 2014 Human Rights Watch

Summary

Over the past two years, the Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat (Democratic Union Party, PYD) – a Syrian Kurdish political party that stems from the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan (Kurdistan Workers’ Party, PKK) in Turkey – has exercised de facto authority over three predominantly Kurdish areas in Syria’s north and northeast: `Afrin (Êfrîn in Kurdish), Ain al-`Arab (Kobani) and Jazira (Cezire). In January 2014, the PYD and allied parties established an interim administration in these areas. They have formed councils akin to ministries, courts and a police force, and introduced a new constitutional law.

The PYD’s armed wing, the People’s Protection Units (Yekîneyên Parastina Gel, YPG), maintains external security in these three areas, and is involved in an armed conflict with Islamist non-state armed groups, primarily Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Sham (ISIS).

This report documents a range of human rights abuses in these PYD-controlled areas with emphasis on Jazira, which Human Rights Watch visited in February 2014. The report focuses on arbitrary arrests, abuse in detention, due process violations, unsolved disappearances and killings, and the use of children in PYD security forces. It does not examine alleged restrictions by PYD-led authorities on free speech and association, or alleged violations against the local, non-Kurdish communities. The background chapter summarizes abuses in the areas by Islamist non-state armed groups.

Since 2011, Human Rights Watch has documented serious abuses perpetrated by the Syrian government and non-state actors in Syria, some of which amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity. While the human rights abuses committed by the PYD and its security forces are far less egregious and widespread, they are nonetheless serious. As the de facto authority, the PYD is obliged under international human rights law to grant the people in the areas it controls – Kurds, Arabs, Syriacs, and others – their fundamental rights.

Of particular concern are the harassment and arbitrary arrests of the PYD’s Kurdish political rivals. This report documents several cases, in which PYD security forces appear to have arbitrarily detained individuals affiliated to Kurdish opposition political parties, such as the Kurdish Democratic Party of Syria (KDPS), the Yekiti Party and the Azadi Party, due to their peaceful political activity against the PYD. Human Rights Watch heard credible allegations of dozens of similar arbitrary arrests. The PYD denies holding any political prisoners and said the men whose cases we documented were arrested for criminal acts, such as drug trafficking and bomb attacks.

In April 2014, a PYD-run court in `Afrin convicted 13 people, including five KDPS members, for various bomb attacks in a trial that seemingly failed to meet international standards. The judges apparently convicted the defendants only on the basis of their confessions, and disregarded complaints that investigators had extracted confessions with torture.

The struggle for power among the Kurds aside, the PYD-run justice system is marred by problems that undermine due process and fair trial rights. In addition to the politically colored cases above, Human Rights Watch documented violations against individuals who were detained for common crimes. The police, known as Asayish, regularly failed to present a warrant when making an arrest, according to those arrested or their relatives. Detained individuals either did not know they had the right to a lawyer or they lacked the money to pay for one. This contradicted local officials, who said detainees were promptly granted access to a lawyer. Current and former detainees also complained about the length of time in detention before seeing an investigative judge, in two cases more than a month.

An effort by the PYD-led authorities to reform Syrian laws is complicating the justice system. Although some Syrian laws discriminate against Kurds or violate other human rights standards, the changes are happening in a haphazard and non-transparent manner, leaving lawyers and detainees confused. The authorities should only amend Syrian laws to bring them into compliance with international human rights standards. Changes to existing laws, rules and regulations should be promptly published and distributed.

The constitutional law introduced in January 2014, called the Social Contract (see Appendix I), upholds some important human rights standards but neglects to stipulate a number of core principles, such as the prohibition on arbitrary detention, the right to prompt judicial review, and the right to a lawyer in criminal proceedings. In a positive development, the contract bans the use of the death penalty.

Article 25 of the Social Contract prohibits the physical or mental abuse of detained persons. Nevertheless, some detainees told Human Rights Watch that Asayish or YPG members had beaten them in custody and were never held to account. Human Rights Watch was unable to determine the full extent of detainee abuse in PYD-controlled areas, but evidence gathered shows that such abuse does take place, in two recent cases leading to death.

In May 2014, a 36-year-old man died in Asayish detention in `Afrin. The Asayish said the man killed himself by striking his head against a wall, but a person who saw the body said the wounds – including deep bruises around the eyes and a laceration on the back of the neck – were inconsistent with self-inflicted blows to the head. In February 2014, the Asayish in Ras al-`Ain (Serê Kaniyê) admitted that a member of its force had killed a 24-year-old detainee. The Asayish and the victim’s family told Human Rights Watch that the responsible officer was tried and sentenced to “life imprisonment with hard labor” for murder.

In Jazira, Human Rights Watch visited the two known prisons in operation – in Qamishli (Qamishlo) and Malikiyah (Dêrik). The Qamishli facility was holding 17 people for different common crimes, all of them men. Malikiyah prison had 15 people for a similar range of crimes, two of them women.

Detainees in both facilities reported adequate conditions: prisoners got food three times a day, exercise at least once per day, and were able to see a doctor. The two women in Malikiyah prison were held in a separate cell, but the men in Qamishli and Malikiyah prisons were held together, regardless if they were accused of a minor or serious crime.

According to Asayish figures provided to Human Rights Watch, as of May 4, 2014, the Asayish was holding 130 people in its `Afrin prison and 83 people in its Ain al-`Arab prison. Opposition activists and some lawyers in `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira said the authorities also ran secret detention facilities but Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm that claim. The Asayish denied holding detainees in any other places.

The past two and half years have also seen at least nine unsolved killings and disappearances of the PYD’s political opponents in areas controlled or partially controlled by the PYD. The PYD has denied responsibility for them all, but the lack of credible investigations stands in contrast to the policing response after other security incidents, such as the rapid mass arrests after most bomb attacks.

Human Rights Watch also found that, despite promises in 2013 from the Asayish and YPG to stop their use of children under age 18 for military purposes, the problem persists in both forces. In February 2014, Human Rights Watch saw two armed Asayish members in Jazira who said they were under 18, and two others who looked under 18 but were told by their commanders not to give their ages. Human Rights Watch also interviewed a 16-year-old boy who said he had joined the YPG the previous year. Two other people said that children in their families had recently joined the YPG.

The internal regulations of both the Asayish and YPG forbid the use of children under age 18 (see Appendices II and III). International law sets 18 as the minimum age for participation in direct hostilities, which includes using children as scouts, couriers and at checkpoints.

In a positive development, on June 5 the YPG admitted that the problem continued and pledged to demobilize all fighters under age 18 within one month.

Human Rights Watch also investigated the violent incidents in Amuda (Amûdê) on June 27, 2013, when YPG forces used excessive force against anti-PYD demonstrators, shooting and killing three men. PYD security forces killed two more men that night in unclear circumstances, and a third the next day. On the night of June 27, YPG forces arbitrarily detained around 50 members or supporters of the Yekiti Party in Amuda, and beat them at a YPG base. The YPG and local authorities should conduct a truly independent investigation into the incident and hold accountable those who arbitrarily held, beat, or used excessive force against detainees and protestors.

Senior PYD officials have repeatedly stressed the party’s and local administration’s commitment to human rights. The constitutional Social Contract says that international human rights covenants and conventions form “an essential part” of the contract. The PYD also granted Human Rights Watch access to the Jazira area, including visits to two prisons, and responded in person and writing to questions.

Despite these commitments, human rights violations in PYD-controlled areas persist. As the legal chapter of this report makes clear, the PYD as de facto authority in `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira is obliged to respect human rights.

To address the shortcomings, Human Rights Watch recommends the authorities take a number of steps. These include forming an independent commission to review the cases of those allegedly detained on political grounds, and releasing those deemed to have been detained arbitrarily. A clear mechanism should be established for detainees to report abuse during arrest, interrogation or detention, followed by legal action against those responsible in regularly constituted courts. These courts should apply Syrian law, amended where needed to comply with international human rights standards. All changes to Syrian laws should be promptly published and distributed. And the Asayish and YPG should cease their use of children under age 18 for military functions, including at checkpoints and bases.

Recommendations

To the PYD-led Interim Transitional Administration

Arbitrary Arrests

- Form a non-partisan, independent commission to review the detention of individuals on potentially political grounds. Release detainees deemed to have been arrested arbitrarily, including those who are being held solely for their non-violent political activity.

Due Process

- Make arrests only with a warrant from the public prosecutor;

- Promptly inform all detainees of the reason for their arrest;

- Grant detainees prompt access to a lawyer;

- Ensure that all detainees are promptly brought before a judge in a regularly constituted court and charged or released;

- Grant accused persons a fair trial before an independent, regularly constituted court;

- Allow local and international human rights organizations to monitor trials.

Abuse in Detention

- Investigate credible allegations of abuse in detention and punish those responsible;

- Establish a clear mechanism for detainees to file complaints of maltreatment and abuse during arrest, interrogation or detention;

- Ensure that judges seriously consider complaints from defendants about ill-treatment in custody and refer cases to the prosecutor’s office for prompt, thorough, and independent inquiry;

- Allow local and international human rights organizations to inspect detention facilities, including prisons and Asayish stations.

Legal Reform

- Ensure that changes to existing laws, rules, and regulations comply with international human rights standards, and are promptly published and distributed;

- Publish a statement to clarify that the applicable law is Syrian law, amended to comply with international human rights standards.

Prison Conditions

- Keep those charged or convicted for minor crimes separate from those charged or convicted for serious, and especially violent, crimes;

- Establish a mechanism for regular monitoring of detention facilities – prisons and Asayish stations – by independent monitors.

Unsolved Disappearances and Killings

- Promptly and independently investigate all disappearances and killings without regard for the victim’s political affiliation;

- Publicly explain what has been done to investigate the unsolved disappearances and killings of political activists and party members.

Child Soldiers

- Cease the use of children under age 18 for military functions in the Asayish and YPG. This includes at checkpoints and bases;

- Cease all military training for children;

- Provide public updates on how many children have been decommissioned from the Asayish and YPG, and what is happening with those children;

- Discipline Asayish and YPG officers who allow children to serve under them;

- Prohibit recruitment of child soldiers at youth or cultural centers, and discipline recruiters;

- Cooperate with international agencies to rehabilitate former child members of the Asayish and YPG, and provide support for their social reintegration.

Amuda Protest

- Conduct a credible, independent investigation into the excessive use of force at the Amuda protest on June 27, 2013 and the subsequent beating of detainees by the YPG.

- Hold accountable members of the YPG who used excessive force or abused detainees.

International Cooperation

-

Fully

cooperate with the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria

and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch based its report findings primarily on two research missions: one to the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) controlled area of northern Iraq and one to the Jazira area, in Syria’s Hasakah governorate.

The mission to northern Iraq took place in late November 2013. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than two dozen Syrian Kurds who had fled to northern Iraq, including former detainees, the relatives of people detained at the time in `Afrin, and the leaders of two opposition parties. The mission to the Jazira area of Syria took place in mid-February 2014 and involved visits to Malikiyah, Rmeilan ( Rmêlan) , Qamishli, Amuda and Derbasiyah (Dirbêsiyê). Human Rights Watch spoke with a wide range of officials from the PYD-led authorities, the YPG spokesman, opposition political party leaders, lawyers, human rights activists, and journalists, as well as 14 detainees at the prisons in Malikiyah and Qamishli. Follow-up research was conducted by telephone, e-mail and Skype with people in `Afrin and Jazira.

For security reasons, armed members of the local police, the Asayish, escorted Human Rights Watch in Qamishli and occasionally between towns in Jazira. The Asayish and local authorities otherwise allowed Human Rights Watch to move freely and to speak without interference with the people of our choosing.

Interviews in Syria and northern Iraq were conducted in Kurdish or Arabic. An interpreter was used for the interviews in Kurdish and for some of the interviews in Arabic. Interviewees gave their consent to use the information they provided in this report, though some requested that Human Rights Watch not reveal their names or other identifying details for security reasons. In Qamishli and Malikiyah prisons, Human Rights Watch selected the detainees to interview, and spoke with them in a private setting. Human Rights Watch offered no compensation to interviewees. In Amuda, Human Rights Watch inspected the scene of the June 27, 2013, demonstration and reviewed videos of the demonstration provided by protesters, the Asayish and YPG.

Human Rights Watch also met with senior PYD officials in northern Iraq, Lebanon, and Belgium, and submitted questions in writing to the Asayish and YPG. Both groups responded in writing (see Appendices IV and V).

I. Background

Kurds in Syria

Kurds are the largest non-Arab ethnic minority in Syria, comprising roughly 10 percent of Syria’s population – in total just under two million people. Most Syrian Kurds are Sunni and speak the Kurmanji dialect of Kurdish.

Syrian Kurds live mostly along the borders with Iraq and Turkey in three areas: the highlands in the northwest around `Afrin, the Ain al-`Arab region in the north, and Jazira in the northeast. Sizeable Kurdish populations also live in Aleppo and Damascus. The three Kurdish-majority areas in Syria’s north and northeast are not contiguous and are also populated by other ethnic communities, including Arabs, Syriacs, Armenians, and Turkmen.

Since the 1950s, successive governments in Syria, including those of Bashar al-Assad and his father, Hafez, have persecuted and discriminated against Kurds.[1] Syrian authorities restricted use of the Kurdish language, banned Kurdish-language publications, and prohibited celebrations of Kurdish festivities. In 1962, the government arbitrarily revoked the citizenship of roughly 120,000 Kurds.[2] Policies under the Syrian Ba`ath party in the early 1970s encouraged Arabs to resettle in the areas where Kurds lived.

In contrast to its repression of Kurds in Syria, the Syrian government in the 1970s and 1980s supported Kurdish groups in Iraq and Turkey. In the 1970s, Syria provided a haven for Iraqi Kurds, particularly members of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. During the 1980s and early 1990s, the Syrian government backed the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) against Turkey by providing arms and training to its fighters based in Syrian-controlled Lebanon. Under heavy Turkish pressure, in 1998 Syria ended its support for the PKK, expelled PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan from his home in Damascus and closed PKK camps in Syrian-controlled Lebanon. [3]

In March 2004, Syria’s Kurds held large-scale demonstrations, some violent, in towns and villages across northern Syria to protest their treatment by the Syrian authorities—the first time they held large-scale demonstrations in the country. The protests began after security forces opened fire on Kurdish soccer fans who were fighting with Arab supporters of a rival team, but they were driven by long-simmering Kurdish grievances about discrimination and repression of their political and cultural rights.

The 2004 protests and developments in Iraqi Kurdistan apparently encouraged Syrian Kurds to push for greater enjoyment of their rights and increased autonomy in Syria. Nervous about Kurdish autonomy in Iraq, the Syrian government intensified its crackdown on Kurdish political and cultural activity.

Between 2004 and the start of the 2011 uprising in Syria, Syria’s authorities continued repressing Kurdish political and cultural rights, including arbitrary arrests of activists, travel bans, abuse of detainees, unfair trials, restrictions on property ownership, and banning demonstrations for Kurdish rights, cultural celebrations, and commemorative events. [4]

The Kurdish political parties in Syria have long been fractured and at odds, and some of the human rights violations in this report stem from these long-standing disputes. The main division lies between the PYD and a group of other Kurdish parties, led by the Partiya Demokrat a Kurdî li Sûriyê (Kurdish Democratic Party of Syria, KDPS), which is a sister party of the Kurdish Democratic Party of Massoud Barzani, President of the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq. In recent years, Barzani and the KDP have strengthened their relations with the government of Turkey in an attempt to increase their independence from Baghdad.[5] While Turkey views the PYD with suspicion as an extension of the PKK, it is currently engaged in talks with imprisoned PKK leader Öcalan. A peace process is under way, including a ceasefire between the Turkish military and the PKK, to end Turkey’s conflict with the PKK and to extend Kurds in Turkey greater rights.

Kurds and the Syria Conflict

When the uprising against the Syrian government began in 2011, many young Kurds joined the anti-government movement. Most of Syria’s Kurdish political parties, however, took a cautious approach, worried about a government crackdown and distrustful of Syria’s Arab opposition.[6] The Syrian government did crack down on protests by Kurds but also enacted some long-held promises of extending citizenship to registered stateless Kurds – by one estimate 50,000 people.[7] Over several months in 2012, the Syrian government and its security forces withdrew from `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira, with the exception of strategic areas in and around Qamishli, apparently not wanting to open hostilities with the Kurds.[8] The strongest and most organized Kurdish political party in the area, the PYD, with a cadre of trained fighters, filled the void with little to no state resistance, reinforced by members from its base in northern Iraq.

Over the past two years, the PYD has consolidated control in the three northern areas. Its armed wing, the YPG, has fought with Islamist non-state armed groups in the area, primarily Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Sham (ISIS), and has managed mostly to secure the `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira areas.

Tens of thousands of Syrian Kurds have also fled their homes for safety in Turkey or northern Iraq. Some left due to poor economic conditions in Syria, and others due to political pressure from the PYD.[9] As of May 2014, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees had registered nearly 180,000 Kurdish refugees from Syria’s Aleppo and Hasakah governorates in the territory of the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq.[10]

The PYD and Syrian government seem to have reached an accommodation, whereby each side tolerates the activities of the other. The Syrian government ceded control to the PYD of most security and administrative bodies in the region but still pays state salaries.[11] In the main city of Hasakah governorate, Qamishli, Syrian government forces remain at the border crossing with Turkey, at the airport and in the center of town, where security agencies are located. PYD forces control the rest of the city. In February 2014, Human Rights Watch observed Asayish forces and Syrian government soldiers in Qamishli regularly passing each other without incident.

The Syrian government’s tolerance of the PYD has opened the Kurdish party to allegations from the KDPS and other political opponents, as well as independent critics, of PYD collaboration with President Assad. The PYD responds that it has chosen a “third way” that is independent of both the Syrian government and opposition forces. It says its goal is to protect the interests of Kurds and other local communities within Syria.[12]

Efforts to forge a common Kurdish political front in Syria have largely failed. In response to the PYD’s consolidation of power, in 2011 a group of Kurdish parties formed the Kurdish National Council in Syria (KNC), which is led by the KDPS and was formed under sponsorship of KRG President Barzani.[13] In June 2012, the PYD-led political body in Syria, the People’s Council of Western Kurdistan, signed an agreement with the KNC to share power through a Supreme Kurdish Committee, including a joint security committee. The power-sharing agreement never functioned, with both sides blaming the other for disrespecting the deal. The KNC and KDPS have accused the PYD of arbitrarily arresting its members and hindering its work.[14]

Declared Autonomy of the Mostly Kurdish Regions

In November 2013, the PYD and an array of smaller, allied parties and groups established a transitional autonomous government in the three areas that comprise what they call Rojava, or Western Kurdistan.[15] The stated goal was autonomous administration within a federated Syria.

Two months later, in January 2014, PYD-led bodies formally established an Interim Transitional Administration with local administrations in `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira. Authorities in each “canton” established councils akin to ministries and a police force. That month the PYD also introduced the Social Contract as a provisional constitution, with chapters on executive, legislative and judicial functions, as well as “Rights and Freedoms” (see Appendix I).

Since then, twenty-two councils have been established in each of the cantons to deal with internal security, justice, foreign relations, health, humanitarian affairs and other administrative affairs. Future elections in each of the three “cantons” will choose local legislative councils. External security is maintained by the YPG, which continues to fight Islamist non-state armed groups. The police force, called the Asayish, has responsibility for internal security and law enforcement.

The Asayish maintains armed checkpoints across the three territories. According to Asayish general commander Ciwan Ibrahim, the force has 8 stations in `Afrin, 6 in Ain al-`Arab and 13 in Jazira.[16] It can detain suspects at these stations for up to 24 hours and runs prisons for longer-term detainees (see Chapter V, Prison Conditions).

The authorities have also established a system of “People’s Courts” in the three areas with two levels: basic and appeals. Officials said the courts enjoy full independence but lawyers not affiliated with the PYD disputed that claim. They said the system was staffed by PYD-appointed personnel and primarily served the PYD. “They just sit and discuss the case without going back to the law or investigating or relying on evidence,” one lawyer who has refused to appear before the courts said. “The courts are not independent.” [17]

In Jazira, basic courts are located in Malikiyah, Gergelige (Girkê Legê), Kahtanieh ( Tirbespiyê) , Qamishli, Amuda, Derbasiyah, Ras al-`Ain, Hasakah (Hisicha) and Tel Tamin (Tal Tamer). Appeals courts are in Ras al-`Ain, Malikiyah, Qamishli and Hasakah.

Each court is presided over by a committee of five, explained Qehreman Issa, co-head of the People’s Court of Qamishli.[18] Four members of the committee are lawyers or legal experts and the fifth “represents society.” He said that local neighborhoods also have special committees to resolve disputes before they go to court.

The PYD told Human Rights Watch that it has included other parties and ethnic groups in the new judicial and political structures, stressing the pluralistic nature of the local administrations. But opposition Kurdish parties, such as the KDPS and Yekiti Party, as well as independent lawyers and activists, complain that the PYD is only willing to accept other parties and groups that agree to the PYD political program.[19]

Attacks on Kurdish Areas

Although spared much of the fighting in other parts of Syria, civilians in the three predominantly Kurdish areas have been victims of ongoing human rights and humanitarian law violations. First and foremost they have suffered serious abuses at the hands of Islamist non-state armed forces, most prominently ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra, during and after fighting in the north and northeast. These abuses include indiscriminate shelling of Kurdish-inhabited areas, targeted attacks on civilians, and the torture and killing of captured civilians or fighters, sometimes by beheading. [20] In August 2013, for instance, opposition fighters captured and killed civilians after taking the Kurdish villages of Tel Aran and Tel al-Hasel (Tel Hasel) near Aleppo. [21]

As of June 2014, fighting was continuing between the YPG and ISIS in Ain al-`Arab, where reportedly about 80,000 people remain. ISIS has reportedly cut electricity and water to the area, although residents have dug new wells. [22] In late May, ISIS reportedly had killed up to 15 Arab civilians, including seven children, in the village of al-Tleiliye outside Ras al-`Ain. [23]

ISIS and Jabhat Al-Nusra have also launched suicide and car bomb attacks in `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira. The targets are often YPG or Asayish checkpoints, which constitute military targets, but sometimes include local administration officials and in one case an office of the Kurdish Red Crescent. Some of these attacks have killed civilians.

On March 11, 2014, for example, three suicide bombers detonated explosive belts in the Hadaya Hotel in Qamishli, which was being used as a central administrative office, killing five people and wounding eight.[24] On the morning of February 8, 2014, a car bomb exploded outside the Qamishli home of Abdul Karim Omar, an official in the Jazira foreign relations office, as he went to work. Omar was unhurt but the bomb killed a father of five, Mohamed Youssef, 37, who was driving by at the time.[25]

Border Closures and Humanitarian Access

Civilians in `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira are also impacted by border closures imposed at the Turkish border by Turkey and at the Iraqi border by the KRG. Local humanitarian groups, both PYD-run and independent, told Human Rights Watch that crossings with both places have remained only partially open for humanitarian aid, greatly reducing the amount of food and medical supplies that can enter. “If you’re diabetic or have the simplest chronic disease like asthma you’re in trouble,” one humanitarian worker said.[26]

Turkey allows limited aid to enter via the informal crossing at Derbasiyah only once a month and in some cases every six weeks, a local official working on humanitarian aid said in February 2014.[27] `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira have received thousands of displaced persons from other parts of Syria but the number as of February 2014 was unknown, the official said. In mid-May Jazira authorities announced the establishment of the area’s first camp for internally displaced persons, initially with 300 tents, near Malikiyah.[28]

In early February, the World Food Programme (WFP) airlifted 40 metric tons of food aid into Qamishli, and announced the future delivery of 360 more tons, but the aid landed at the Syrian-government-controlled airport.[29] Local Kurdish authorities and local aid workers told Human Rights Watch that none of the aid went to civilians in areas outside the government’s control. In his March 2014 report to the Security Council, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called the airlifts “a limited and highly cost-ineffective alternative to land access” for the 500,000 people in Hasakah in need of assistance.[30]

On March 20, the Syrian government, for the first time, allowed humanitarian aid to enter Syria from Turkey through the government-held border crossing at Qamishli. Government and government-affiliated organizations distributed the aid. According to a non-PYD affiliated activist in Jazira who works on humanitarian assistance, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent distributed 30% of the aid to a PYD-affiliated organization.[31]

On May 16, WFP announced it was delivering 34 more trucks with food and 10 temporary warehouses for storage across the border at Qamishli.[32]

II. Arbitrary Arrests

Over the past two years, the PYD-dominated Asayish has at times arbitrarily arrested political opponents of the PYD. Human Rights Watch investigated the cases of six Kurdish men affiliated with an opposition political party – the Kurdish Democratic Party of Syria, the Azadi Party or the Yekiti Party – whom the authorities appear to have arrested arbitrarily in `Afrin. Three of the men were released and the other three were sentenced to lengthy prison terms after an apparently unfair trial in April 2014 (see below).

The three released men interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were detained for one week, one month and two months, respectively, but were never formally charged or brought before a judge. During their detentions they said they had no access to a lawyer, and only one of them was granted a family visit. Two of the men thought they had been detained because of their peaceful political activity, and the third did not know the reason.

Two of the three released men said they were not physically abused in detention but they heard others getting beaten at the detention facility where they were held in the basement of a former court house in `Afrin (see Chapter IV, Abuse in Detention). One of the two men said he was held in an isolation cell for 20 days and threatened with death. The third man said he was beaten multiple times with a cable while detained in a village school outside of `Afrin.[33]

Family members of the three people convicted in April 2014 told Human Rights Watch in November 2013 that they had no information about the criminal charges or judicial proceedings, and they thought the arrests were due to peaceful political activity. “You can’t say anything because they’re the power,” the daughter of one of the men told Human Rights Watch, referring to the PYD.[34]

“We have no information,” a sister of one of the other men said. “All we get is rumors about him on Facebook.”[35]

Relatives of two of the detainees said a family member had been able to visit their relative in detention. In two of these three cases, relatives said that PYD forces took cash and property from their homes and stole the family car.

The Asayish general commander Ciwan Ibrahim denied that the Asayish made arrests on political grounds. “We do not detain a single political prisoner,” he wrote to Human Rights Watch in May 2014. “All detainees are charged with criminal or terrorism-related charges.[36] Senior administration officials in Jazira made the same point. All arrests were made on the basis of an individual crime, such as trafficking in drugs or involvement in an armed attack staged by an extremist Islamist group, they said. “We have no people arrested on a political basis,” head of internal security for Jazira Kanan Barakat told Human Rights Watch. Arrested political activists have all been charged because they committed criminal offenses, mostly drug or arms possession, he said.[37]

On December 13, 2013, after negotiations between the PYD and opposition parties, the Asayish announced that it had released 54 detainees pursuant to a court order, most of whom had been accused of aiding extremist groups.[38] On January 7, 2014, the KDPS and Azadi parties called for the release of 11 of their detained activists, among them the three individuals whose relatives Human Rights Watch had interviewed.[39]

On April 29, a court in `Afrin convicted 13 people for various bomb attacks, including five KDPS members who were on the list of 11 people the KDPS and Azadi parties had complained about in January.[40] The convicted persons were:

- Mohiuddin Sheikh Saydi and Mohammed Hussein, sentenced in absentia to 20 years in prison for detonating a bomb at a civil society building in Efrin on August 22, 2013;

- Hanan Ma'mou, Rizan Mohamad and Hamid Bin Jamal, sentenced to 15 years for bombing a car in Efrin on November 27, 2012;

- Bayazid Mamo, Siyamand Barim and Mohammed Saeed Isso, sentenced to 10 years for detonating a bomb at the Free Media Union in Efrin on September 4, 2013;

- Rassoul Ismael, sentenced to 10 years for trying to blow up a car carrying a PYD official;

- Hassan Shandi and Joan Shiekho, sentenced to 20 and 10 years respectively for bombing the women association center in Efrin on July 4, 2013;

- Akid Mostapha and Adham Khalil, sentenced to 10 years for bombing a car in Efrin on November 27, 2012.

The KDPS called the verdicts “politically motivated.”[41] One individual with direct knowledge of the trial proceedings, who wished to remain anonymous due to security risks, said the defendants were convicted solely on the basis of their confessions. The defendants complained to the judge about having been tortured in custody, the person said, but the judge dismissed the complaint.[42]

In response to the verdict, a Kurdish human rights group based in Germany, the Kurdish Centre for Legal Studies and Consultancies (YASA), highlighted a number of procedural violations and criticized the “failure to secure a fair trial.”[43] Based on a review of the court records, YASA said the judges had failed to consider the defendants’ complaints of torture to extract confessions. The local authorities had also refused YASA permission to visit the defendants in February 2014, a member of the group said.[44]

In response to a Human Rights Watch inquiry about the other individuals on the KDPS and Azadi list from January, Asayish general commander Ibrahim said they were not in Asayish custody and “their status is not known to us.”[45]

III. Due Process Violations

Along with a police force, the PYD-led authorities in `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira have established a judicial system over the past two years that includes a prosecutor’s office and two levels of courts, basic and appeals. They have also begun to reform some Syrian laws and the criminal code. The extent that Syrian law still applies remains unclear.

According to the head of internal affairs council in Jazira, Kanan Barakat, the Asayish must obtain a warrant from the public prosecutor before making an arrest. He said detainees are treated humanely, granted access to a lawyer, brought before a judge within three days, and tried before an independent court. Interviews with local lawyers, human rights activists and people currently or formerly in detention, however, strongly suggest that the system fails to meet basic fair trial standards or to protect the right of detainees from arbitrary detention and mistreatment.

Justice officials blamed failures on the lack of qualified prosecutors, judges, and legal experts. “We don’t deny there are problems,” said the senior justice official in Jazira, Sanharib Barjoum, who was appointed in mid-January 2014. “The people in the courts are not always well prepared.”[46]

Independent lawyers and human rights activists agreed that the judicial system lacked qualified prosecutors and judges. But they placed blame more squarely on the PYD-run authorities for politicizing the system and for not allowing independent courts.

“The courts are not independent, they are related to one political force,” one lawyer said. “As a result, they can’t protect their independence.”[47]

The founding constitutional document of `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira, the Social Contract, enshrines independence of the judiciary (Article 63) and guarantees the right to a fair trial (Article 72). Detaining a person without evidence constitutes a criminal offense (Article 73).

Article 20 says that international human rights covenants and conventions form “an essential part and complement this contract.” Article 22 calls the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights an “integral part of this charter.”

In the majority of the 20 detention cases investigated by Human Rights Watch, including those detained on apparently political charges and those detained for common crimes, the individuals themselves or their relatives said the Asayish did not present a warrant when making the arrest.[48]

Justice and security officials in Jazira told Human Rights Watch that the court provides a lawyer to those who cannot afford one, but none of the current or former prisoners interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had received this offer. Of the 20 cases examined by Human Rights Watch, only one person said he had a lawyer. The others either did not know they had the right to a lawyer or they did not have the money to pay for one, according to the arrested persons or their relatives.

Barakat and other officials said the Asayish can hold a person for up to 24 hours, extendable for up to two more days by order of the public prosecutor, before seeing a judge. Chapter 6 of the Asayish’s internal regulations prohibit the Asayish from detaining a person for more than 24 hours without an extension order from a “judicial authority,” and a person must be “referred to the judiciary” within seven days (see Appendix III).

Current and former detainees however complained about the period of time in detention before they were brought before a judge. Four people said they saw a judge after one week and one person said it happened after three days. But one person said he did not see a judge until after more than two months in detention. A detainee in Qamishli prison said he had been there for one month at the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit in February 2014 without seeing a judge. A detainee in Malikiyah prison said he had been there for three weeks without seeing a judge.

The question of sentences also caused great confusion among former and current detainees. Two men in Qamishli prison said they were serving sentences without having ever appeared in court. One of the men was caught possessing drugs. He said the Asayish told him that he must stay in prison until he pays a fine. The other man said the Asayish ordered him to stay ten days in prison for a violent altercation with a neighbor who filed a complaint.

Other detainees said they were being held while a mediation or discussion over compensation was underway with the aggrieved party, but they did not understand the process.

The right to a fair trial and other due process guarantees are fundamental rights that apply at all times, even during situations of emergencies such as armed conflict. These basic rights include the right of all detainees to have their detention promptly reviewed by a judge.

International humanitarian law strictly prohibits any party to a conflict from “the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable.” [49]

Shifting Laws

An ongoing effort by the PYD-led authorities to reform Syrian laws is complicating the justice system. Lawyers, judges, and justice officials gave different accounts of the laws in effect.

Article 18 of the Social Contract states: “There is no crime and no punishment without a legal text.” However, the PYD-run areas have no legal gazette to publish new laws, and the authorities have not otherwise published changes to Syrian laws or the criminal code.

Exactly who is responsible for abrogating and amending laws also remains unclear. Future plans exist to form a Constitutional Court that ostensibly could review laws but the body does not yet exist.

At the same time, some of Syria’s laws are so broadly articulated that the courts could potentially punish a range of peaceful activities and stifle free expression. Some provisions explicitly ban political expression, such as those prohibiting membership in political parties without permission.[50] Other laws discriminate against Kurds, such as the ban on using the Kurdish language and restrictions on the sale of property to Kurds.[51]

According to the head of internal security in Jazira, Kanan Barakat, also a lawyer, the project to reform laws and regulations began around September 2012. He said a combination of laws from Syria, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Egypt were currently in effect, as well as the Social Contract and what he called “local customs.” Co-head of the People’s Court of Qamishli, Qehreman Issa, gave a similar account. “We are preparing the laws for Rojava bit by bit,” he said. “Some laws are from Syria, some from France, the UK.” He explained that, unless there is a change, Syrian law remains in effect but “at the same time we get inspiration from other laws.” [52] This differed from the view of Asayish general commander Ciwan Ibrahim, who said the Asayish applies Syrian criminal law and the Social Contract. [53]

Qehreman Issa rejected claims that the unclear legal reform opens the door for abuse. “We in the society are in agreement about what is criminal and what is not,” he said.

Aside from having revoked the discriminatory laws against Kurds, justice officials said they had also removed the death penalty. Indeed, in a positive development, Article 26 of the Social Contract abolishes capital punishment.

The unclear reform process has left prisoners and detainees confused. “[The judge] told me that I am detained until they figure out what to do with me,” one prisoner in Qamishli prison said. “I don’t know what law I will be judged under.”[54]

“I don’t know what’s going on, no one knows the laws,” another prisoner in Qamishli prison complained.[55]

IV. Abuses in Detention

Article 25 of the Social Contract prohibits the physical or mental abuse of arrested persons. Such abuse is taking place nevertheless, in two recent cases leading to death.

One man arrested for a common crime, whose details are not provided to protect his identity, said Asayish members physically beat him in Qamishli in late 2013 to force him to confess.

When they put me in the car they started to punch me. They kept beating me from Amuda to Qamishli. They punched me in the head, face and stomach. They took me to Qanat al-Sweis police station. I didn’t confess right away, and they beat me. The second day they asked me again and I denied. The fifth day they took me, blindfolded me, and put my hands in the cuffs. They put me on the ground. They put my legs in their Kalashnikov. They started to beat me on part of my legs…bottom of my feet…with a thick stick…. My eyes were blindfolded. Two people held my legs. They caused a big shock. They used electricity also. Because my flesh can’t handle the stick, I confessed.[56]

The man said he appeared before a court after one month and the judges asked if he had confessed due to torture. The man replied that he had but also told the judges that he had committed the crime. He said the court acknowledged that he had been beaten but asked no questions and took no further steps. As far as he knows, no Asayish members have been punished.

Another detainee said he was arrested in mid-2013 for a common crime. He tried to escape the Asayish, he said, and when they caught him, they beat him:

They hit me in the head with a Kalashnikov when they caught me. They broke one of my ribs. They took me to Gharbiyeh [an Asayish police station in Qamishli]. The Asayish beat me there. They were five guys. They hit me with their Kalashnikovs and with sticks. I was bleeding. They were swearing at me and beating me. After that they brought us food. Then one of the Asayish stitched up my head.[57]

Another man, a member of KDPS, said he was badly beaten after his arrest in `Afrin in July 2013, ostensibly for involvement in a bomb attack:

One guy came with a heavy cable. He called me. He told me to lie down and he started hitting me. He began with the feet and then my whole body. They said I had killed a PYD guy. They went to bury their guy and then came back. They brought dirt from his grave and asked me to eat it. Then they beat me again. They brought a Kalashnikov and tied it to my feet between the gun and strap. One guy got tired so another beat me.[58]

Two other men who were detained and released from custody in `Afrin said they were not physically abused in detention but they heard others getting beaten at the detention facility where they were held in the basement of a former court house. One of those men said he was held in an isolation cell for 20 days and threatened with death.[59]

Some members of the YPG also beat dozens of detainees, members of the Yekiti Party, in June 2013 after using excessive lethal force against a demonstration in Amuda (see Chapter VIII, Amuda Protest). Two of the beaten detainees told Human Rights Watch that the YPG held them for one and a half days in a damp basement on a YPG base near Himo, where they were denied food and water and beaten. [60]

The head of the internal affairs council in Jazira, Kanan Barakat, accepted that some detainee abuse took place but said abusive forces are held to account. “It’s happened, maybe some beating or excessive force,” Barakat said. When abuse take place, the responsible Asayish member is held accountable “like any other citizen,” he added.

Barakat did not know how many Asayish members had been punished.[61]

Asayish general commander Ciwan Ibrahim gave some details in response to a question from Human Rights Watch. Five Asayish members had been disciplined for having maltreated detainees, he wrote to Human Rights Watch, without indicating when this had happened.[62] The punishments ranged from four to six months of detention, and all of the individuals were dismissed from the force, he wrote.

Death of Hanan Hamdosh

On May 3, 2014, Asayish forces in `Afrin arrested 36-year-old Hanan Hamdosh, according to a media report and a person close to the family. The next day, Asayish told the family that Hanan had died in detention from purposefully striking his head against the wall.

The person close to the family said that Hamdosh had been arrested before for criminal acts, but was released to attend his wedding on May 2.[63] The day after the wedding, he had an altercation with a person in `Afrin that prompted an Asayish intervention. The Asayish arrested Hamdosh, who cursed PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan, insulted the Asayish officers and struck one of them, the person said.

On May 4, the Asayish informed the family that Hamdosh had killed himself in detention by striking his head against the wall. A statement released by the Asayish reportedly said that Hamdosh was drunk and had acted aggressively. “As he was kept in detention, he started to shout and to hit the wall and metal door of the detention room with his head which caused his death,” the statement said.[64]

The person close to the family, who saw the body after the Asayish had returned it to the family, described heavy bruises around the eyes and on both hands, a broken finger on one hand and an abrasion on the back of the neck – wounds which the person said appeared inconsistent with self-afflicted blows to the head. A photograph of Hamdosh’s face viewed by Human Rights Watch showed what appeared to be contusions and dark bruises around both eyes.

Death of Rashwan Atash

On February 18, 2014, four members of the Atash family were detained after an altercation with the Asayish in Ras al-`Ain. The altercation took place after the Asayish intervened in a dispute over money between the Atash family and another family. One of the four detained members of the Atash family, Rashwan Atash, a 24-year-old electrical engineer, died after being taken into custody.[65]

A statement issued by the Asayish on February 19 said an Asayish member had “attacked the suspects involved in the quarrel, which led to the death of Rashwan Atash from a heart attack.”[66] The Asayish said the responsible Asayish member would be tried before a court.

On February 20, the Asayish delivered Rashwan’s body to the family. His brother told the media that his body bore signs of abuse. Rashwan’s cousins were released but had also been beaten, a person close to the family told Human Rights Watch.[67]

In response to questions from Human Rights Watch, Asayish general commander Ciwan Ibrahim said that the (unnamed) responsible Asayish member had been tried and convicted for murder, and sentenced to “life imprisonment with hard labor.” A member of the Atash family confirmed the Asayish member’s arrest and conviction.[68]

“Rashwan died on February 18, 2014, hours after his arrest, due to a beating by an Asayish administrative member in Ras Al-`Ain, in response to provocation by Rashwan,” Ibrahim wrote. “The cause of Rashwan's death was cardiac arrest, caused by the beating of the Asayesh administrative member (B.).”[69]

According to Ibrahim, the Asayish members who witnessed the beating of Rashwan have been dismissed from the force.

V. Prison Conditions

In Jazira, Human Rights Watch visited the two known prisons currently in operation in the area: the facilities in Qamishli and Malikiyah. A third prison in the Qamishli neighborhood of Qanat al-Sweis was closed after a bomb attack at the front gate on November 23, 2013.[70]

Asayish general commander Ciwan Ibrahim said the areas of `Afrin and Ain al-`Arab each have one prison but Human Rights Watch was unable to visit those areas for security reasons. In a letter to Human Rights Watch, he said that, as of May 4, the Asayish was holding 130 people in `Afrin and 83 in Ain al-`Arab, but these numbers change as a result of arrests and releases.[71]

Jazira authorities were informed ahead of time about the visit to Qamishli prison, but prisoners there said nothing had been changed prior to Human Rights Watch’s arrival. The visit to Malikiyah prison was spontaneous.

Qamishli and Malikiyah prisons are both run by the Asayish. The head of the Jazira Justice Council, Sanharib Burson, said the prisons will be transferred soon under his committee’s jurisdiction but he was unable to give dates for that transfer.[72]

In addition to these two prisons, detainees are also held for short periods in Asayish stations across Jazira, as well as in `Afrin and Ain al-`Arab. According to Asayish general commander Ciwan Ibrahim, the force has 13 stations in Jazira.[73]

Opposition activists and some lawyers in `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira said the authorities also ran secret detention facilities but Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm that claim. Asayish general commander Ibrahim denied having any secret detention facilities and said the prisons are open for visits by nongovernmental organizations.[74]

The YPG also has detention facilities for prisoners of war but they provided no information about the location of these facilities or the number of prisoners. “Those we arrest we treat as prisoners of war, according to the Geneva Conventions,” YPG spokesman Redur Xelil said. In some cases, the YPG had engaged in prisoner swaps with Islamist non-state armed groups. [75]

Conditions at Qamishli and Malikiyah prisons were adequate. The prisoners – incarcerated for crimes ranging from theft to murder – had no major complaints about the physical environment: they got adequate food three times a day, exercise at least once per day, and were able to see a doctor if they were ill.

The main complaint of prisoners was the lengthy time before they saw a judge – in two cases more than one month – and the lack of clarity about their legal process (see Chapter III, Due Process Violations).

The Qamishli prison, formerly a cinder block factory, has been in operation for two and a half years, the prison director Faner Mahmoud said.[76] He said, and prisoners confirmed, that the prison was holding 17 prisoners at the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit, though the prison had capacity to hold 40. Mahmoud said the prisoners were all pre-sentence. Head of the internal affairs in Jazira, Kanan Barakat, said that lawyers visit their clients every three or four days but only one of the seven prisoners Human Rights Watch interviewed in Qamishli prison said he had a lawyer, either because they did not know they had the right to see one or they did not have the money to afford one.[77]

All of the prisoners in Qamishli prison were men, and all of the interviewed prisoners said they were older than 18 years old. The prisoners were held in two group rooms with no separation of prisoners who had committed serious crimes, including at least one man held for murder.

Previously a security branch run by the Syrian government, the PYD-led authorities took control of Malikiyah prison also about two and half years ago, an official at facility said. “We found whips, sticks, batons, but we got rid of these things,” he explained. [78]

Human Rights Watch interviewed seven prisoners, two of them women who had been transferred to Malikiyah prison from Hasakah on that day. The women were held in a separate cell, and 13 men were together in one large cell, with no separation for men who had committed serious crimes. The prison’s capacity is 20.

The prison official said that all of the prisoners had appeared in court, but five of the seven interviewed prisoners said they had not yet been in court.

The Asayish has not established procedures to allow for the regular monitoring of detention facilities, both prisons and Asayish stations, by human rights monitors. One local human rights organization told Human Rights Watch that it had conducted some ad hoc visits, as had some lawyers, and the newly established Human Rights Committee of the local authority said they planned to undertake such visits.[79] But mechanisms and procedures for these visits remained unclear.

In February 2014, a Kurdish human rights group based in Germany, the Kurdish Centre for Legal Studies and Consultancies (YASA), which was in `Afrin to conduct human rights trainings, requested permission to visit a group of detainees. The authorities refused, YASA said. [80]

The monitoring of Asayish detention facilities is critical because most reports of abuse come from the initial period after arrest and during interrogations.

VI. Unsolved Disappearances and Killings

Since the PYD began to establish control in 2012 over `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira, some politically active individuals with non-PYD parties have gone missing or been killed in unclear circumstances. PYD authorities deny involvement in these crimes, and blame the Syrian government or other non-state armed groups. Opposition parties and relatives of some of the victims blame the PYD.

Human Rights Watch conducted only cursory investigations into the four cases below, and does not have conclusive evidence that PYD authorities were involved. However, by all available accounts the authorities have not conducted serious investigations into these deaths and disappearances. On the merits of the cases alone, and especially given the allegations of politically motivated crimes, the PYD-led authorities should conduct full and impartial investigations to determine what took place.

The most prominent case, the October 2011 killing in Qamishli of the Kurdish political activist and politician Meshaal Tammo, is among those that remain unsolved, though it occurred before the PYD had established full control.[81] Tammo’s family and the PYD accused the Syrian government of the killing.[82]

Amir Hamid

On January 11, 2014, a group of armed men reportedly kidnapped 37-year-old Amir Hamid, a member of an anti-Syrian government youth group, from his home in Derbasiyah. Hamid’s family told the media that the men took Amir and three others who were with him at the time. [83] On January 15, Asayish denied having any involvement in Amir’s disappearance. [84]

A relative of Hamid told Human Rights Watch that armed men the family believed to be from the YPG took Amir, along with three other men and a woman, who were meeting to organize getting smuggled to Turkey. Amir feared for his safety, even though he was a peaceful activist in the Kurdish youth movement, the relative said.[85]

According to the relative, two of the men and the woman were released, but Amir and the other man, an Arab, remain missing as of May 20. “The place where my brother was detained is a place that was previously held by the YPG,” the relative said. “I know it and everybody knows it.”

The Asayish told Human Rights Watch that they conducted an investigation but were unable to find Hamid. “We could only establish that a civilian car carrying 4 civilians had abducted Mr. Hamed, leaving the smuggler and the Arab girl,” Asayish general commander Ciwan Ibrahim wrote in a letter to Human Rights Watch.[86]

Ahmed Bonchaq

According to the KDPS party and a person close to the family, 20-year-old Bonchaq was active in the KDPS and had gone to the KRG in 2012 for military training by security forces there. He was briefly detained by PYD security forces upon his return in August 2012, and was then arrested by Asayish forces in Qamishli on February 19, 2013, the person close to the family said.[87] The Asayish allegedly did not acknowledge Bonchaq’s detention but they released him from a facility in Malikiyah on May 8, 2013. Asayish General Commander Ciwan Ibrahim told Human Rights Watch that the Asayish had detained Bonchaq in February because he had “fought with an extremist group.”[88]

Four months later, on September 1, 2013, unknown gunmen shot and killed Bonchaq a few hundred meters from his Qamishli house, in front of the Abd Ahad Younan School. Although the killing occurred at midday, apparently with witnesses, the Asayish has to date made no arrests. Asayish General Commander Ciwan Ibrahim wrote to Human Rights Watch that the Asayish has “leads on the identity of the assassins” but did not provide details.[89]

On May 4, Asayish General Commander Ciwan Ibrahim wrote to Human Rights Watch that the Asayish had no information about the case.[90]

Bahzed Dorsen

The head of the KDPS in Malikiyah, Bahzed Dorsen, went missing on October 24, 2012, while traveling in a car near the Syria-KRG border, with the intent of crossing into KRG, his family and party said. His family and the KDPS believe the abduction was politically motivated and that he was taken by the PYD.[91] Human Rights Watch does not have evidence to assign blame, but the PYD-led authorities have apparently failed to conduct a proper investigation. The authorities deny involvement in the disappearance and say Syrian government security forces were operating in the area at the time.[92]

The Asayish in Malikiyah said that they are not currently investigating the case. “We investigated it but rumor in the street is that he went to Germany, so we’re not sure,” an Asayish official in Malikiyah said. “At the same time, even the regime was controlling this area [of Dorsen’s disappearance].”[93]

A relative of Bahzed Dorsen, who wished to remain anonymous, said Dorsen had received threats from the PYD prior to his disappearance. He rejected the suggestion that Dorsen was in Germany or that he was taken by Syrian government forces. “Only the YPG was active where [he] was kidnapped,” he said.[94]

This relative and one other family member said that no one from the Asayish or local authorities had interviewed them as part of the alleged investigation. If true, this stands in sharp contrast to the mass arrests the Asayish typically make after security incidents, including bomb attacks.

In response to Human Rights Watch questions about the case, Asayish General Commander Jawan Ibrahim said the Asayish searched for twelve days without success after Dorsen’s disappearance.[95]

Nidal, Ahmad and ʿAmar Badro

On January 8, 2012, armed individuals reportedly affiliated with the PYD went to the Qamishli home of Abdullah Badro, a former supporter of the PKK, to resolve a property dispute. A fight ensued that left Abdullah Badro wounded and a known senior PYD member named Mohamed Mahmud (“Khabad”) dead. [96]

Two days later, unidentified gunmen shot and killed three of Abdullah’s sons: Nidal, 45, Ahmad, 41, and ʿAmar, 39. A member of the family told Human Rights Watch that Ahmed was shot in the courtyard of the hospital while visiting his father, while Nidal and ʿAmar were shot in their car while driving home from the hospital. [97] A previously unknown group that called itself “Protectors of the People’s Values” reportedly took responsibility for the murders but the family believes the PYD was taking revenge for the death of one of its senior members. [98] The family member told Human Rights Watch that Abdullah Badro’s house in the Hay-Gharbi neighborhood of Qamishli is now occupied by the Asayish and the street name has been changed from Huriyya Street to Khabad Street after the PYD member who died. To date, no one is known to have been arrested for the murders.

VII. Children in Security Forces

Since assuming power in 2012, the Asayish and YPG have both used boys and girls under age 18 at checkpoints and on bases in `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira. Some children have fought with the YPG. The Asayish serves as a police force, but its members are armed with automatic weapons and its checkpoints have been the target of car bombings and other attacks.

The use of children by the Asayish and YPG directly violates the internal regulations of both forces (see Appendices II and III), which forbid membership of anyone under age 18. International law prohibits the use of children as participants in direct hostilities, which includes using children as scouts, couriers, or at checkpoints.

The Asayish and YPG say they have made efforts over the past year to reduce their use of children for military purposes but the problem persists in both forces. During a visit to Jazira in February 2014, Human Rights Watch saw two armed Asayish members who said they were under 18, and two others who looked under 18, but, after pressure from their commanders, refused to give their ages. Human Rights Watch also interviewed a 16-year-old boy who said he had been in the YPG since the previous year. Two other people said that children in their families had recently joined the YPG – one of them a 13-year-old boy whom the YPG sent home after the family complained.

Human Rights Watch did not visit `Afrin or Ain al-`Arab and could not confirm whether children are still in the security forces there.

In a positive development, on June 5 the YPG publicly admitted that the problem of child fighters continued. It pledged to demobilize all of its fighters under age 18 within one month and to cease its recruitment of children.[99]

In its August 2013 report, the UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria reported on the YPG’s use of children. “In `Afrin (Aleppo) and Al Hasakah, the YPG recruited boys and girls from the age of 12,” the report said. “In late 2012, large numbers were recruited to counter an attempt by Jabhat Al-Nusra to enter Al Hasakah from Turkey.”[100]

Five months later, a UN report on Children and Armed Conflict in Syria said that, as of November 15, 2013, boys and girls aged 14 to 17 had joined “Syrian Kurdish armed groups” in al-Hasakah governorate. “Children have mostly been used to man checkpoints, transfer information and military supplies, but were also trained to participate in combat,” the report said. One 17-year-old boy said he had participated in military operations.[101]

Human Rights Watch interviewed seven Syrian Kurds in northern Iraq in December 2013 who said that they had at least once seen armed boys and girls under age 18 at YPG or Asayish checkpoints in November or December 2013. In two cases, the person recognized the boy and warned the parents. In one case, the person said his 17-year-old son had joined the YPG. This man said he knew of other children who had been sent to the frontlines, some of whom had died.

YPG Response and Ongoing Use of Children

In response to the 2013 UN Commission of Inquiry report, the YPG called the recruitment of children “unacceptable” and “prohibited.” Some children had joined on a “voluntary basis” but did not serve on the battlefield, the YPG said.[102]

Three senior PYD officials, YPG spokesman Redur Xelil, and the Jazira head of internal affairs, Kanan Barakat, all told Human Rights Watch that security forces in `Afrin, Ain al-`Arab and Jazira rejected the use of children in any combat function, including at checkpoints. Some children had volunteered and their participation in military activity represented isolated mistakes, they said in late 2013 and early 2014.

In December 2013, YPG General Command issued an order that prohibited participation in the YPG of children under age 18. Those who violate the order will be held “strictly accountable,” the order said.[103] The order bolstered Article 5.2 of the YPG’s internal regulations, which states that YPG members must be 18 or older (see Appendix II).

In a January 2014 letter, YPG spokesman Xelil wrote to Human Rights Watch that the YPG had implemented the December order by removing from military operations 17 people under age 18, without specifying if they were boys or girls. He wrote that these children were instead assigned tasks in media, education, or political training centers. The YPG was also in negotiations with the Switzerland-based organization Geneva Call to sign a public pledge to stop using child soldiers, Xelil wrote.[104] In October 2013, the PKK in Turkey had signed Geneva Call’s “Deed of Commitment” to prevent children under 18 from taking part in hostilities.[105]

In a February 12, 2014 meeting with Human Rights Watch, Xelil explained that the December order was issued to reaffirm the YPG’s regulations because of violations. “I’m sad to say there were sometimes violations of that order and were even some martyrs among them,” he said. Xelil said that no YPG members had been disciplined for having violated the regulations of the December order.[106]

Regarding ongoing cases, Xelil said the YPG had taken concerted action but he could not rule out the continued involvement of some children. “I can’t be certain 100%, maybe there are a few cases in `Afrin or elsewhere,” he said.

During its February 2014 visit to Jazira, Human Rights Watch gathered evidence of the YPG’s continued use of children. On February 12, researchers interviewed a 16-year-old boy who said he had been serving in the YPG since he was 15. He said he joined after going to YPG meetings at local youth centers, where YPG members spoke to him and other children. “They would talk to us about the Kurdish situation and explain the importance of defending the [Kurdish] nation,” he said. “It is our choice to join… My mom and dad were against it and said no but I wanted to.”[107]

The boy said he went to a YPG base to register with his real name and age, and the YPG allowed him to join. He received weapons training and has since worked at checkpoints, and been sent to places where there have been explosions. “In the morning I go to school and then I go to serve,” he said.

On February 13, Human Rights Watch spoke with a woman in Qamishli who said her 13-year-old son had joined the YPG in December 2013 without her knowledge after spending time at a PYD youth center. After locating him and speaking to his YPG commanders, the family agreed to let him finish the training, with the understanding that the YPG would send him home when the training was done, which the YPG did.[108]

On March 21 Human Rights Watch interviewed a Kurdish man from Amuda by phone, who said his 17-year-old brother had joined the YPG in January. The man said his brother had left home without informing the family of his intentions, and the family only learned that he had joined the YPG a few days later from a YPG official.

“He disappeared and for three days my parents searched for him everywhere, including police stations and security branches, but they didn’t find him,” the man said. “On the fourth day a YPG official, not high ranking, came to my parent’s house and told them that he had joined the YPG.”[109]

The man told Human Rights Watch that in March his brother had visited his sister at her school wearing a military uniform and carrying a weapon. He told his sister that he was fighting with the YPG on the frontline. “That was the last time we heard from him,” the man said.

On June 5, the YPG told Geneva Call that it would register all of its fighters under age 18 and demobilize them within one month. The YPG also said it would no longer admit new recruits under age 18 and sign Geneva Call’s “Deed of Commitment” protecting children in armed conflict. [110]

Asayish Response and Ongoing Use of Children

Asayish internal regulations, Article 7.2, forbid individuals under 18 from joining the force (see Appendix III). The newly appointed head of internal security in Jazira, Kanan Barakat, with supervision over the Asayish there, said on February 9, 2014 that the force used to accept children but that changed “four or five months ago.” Today all Asayish members must be over 25 and there are no children in the force, he said.[111]

In a February 2014 Skype interview with Human Rights Watch, Asayish General Commander Ciwan Ibrahim said the change had occurred one month before:

When the Syrian revolution first started we had to recruit children under the age of 18. A month ago we issued an order prohibiting the recruitment of child soldiers not even on a voluntary basis. In the past month we have complied with the order and we no longer have child soldiers.[112]

Despite these commitments, on February 12, 2014, Human Rights Watch saw an armed girl at an Asayish checkpoint in Malikiyah, who said she was 17 years old.

On February 13, Human Rights Watch saw an unarmed girl working as an Asayish guard at a checkpoint near the Semelka (Faysh Khabour) border crossing with KRG, who said she was 17 years old. The girl said she had worked with the Asayish, including at checkpoints, for more than two years.

During the February visit to Jazira, Human Rights Watch saw two other young, armed Asayish members – a male and a female – who looked under 18, but, under pressure from their commanders, refused to give their ages.

Legal Standards

International law sets 18 as the minimum age for participation in direct hostilities. Under the International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute, it is a war crime for armed forces or groups to conscript or enlist children under 15, or to use them “to participate actively in hostilities.” According to definitive interpretations of the statute, active participation in hostilities not only covers children’s direct participation in combat, but includes activities linked to combat such as scouting and the use of children as decoys, couriers, or at military checkpoints.

VIII. Amuda Protest, June 27-28, 2013

On June 17, 2013, Asayish forces in Amuda – a town of about 50,000 people – arrested three non-PYD political activists, Walat al‑‘Umari, Sarbast Najjari, and Dersim `Umar. The reason given wasdrug use and trafficking, but Kurdish opposition groups considered the arrests political. To protest the arrest, opposition groups and supporters staged a protest at a tent in the town’s main square, which developed into a hunger strike.

On June 26, the Asayish released Dersim `Umar. Head of the Asayish in Amuda, Hamza Toheldan, told Human Rights Watch that he offered to release the other two men if the protest stopped.[113]

`Umar promptly joined the protest of about 300 people and used a megaphone to talk about his time in detention, several protesters separately told Human Rights Watch.[114] He complained about poor conditions and physical abuse. (Asayish commander Toheldan told Human Rights Watch that the three men were not abused.)

The protest continued the next day, June 27. The crowd marched down the main street toward the square when unexpectedly, around 7:00 pm, a convoy of YPG vehicles reached the main street from a smaller perpendicular road, the protest participants said. Asayish commander Toheldan and YPG spokesman Xelil said the convoy was coming directly from fighting with Islamist non-state armed forces at the Hasakah dam.[115]

According to protesters Human Rights Watch interviewed, the crowd blocked the YPG convoy and started shouting at the soldiers. A few of the vehicles in the convoy managed to turn right onto the main road, which leads to the square and then to Qamishli. The first vehicle, a sedan, accidently hit and injured a young girl named Gulan, a protester who saw the accident said. [116] The girl has mostly recovered from a broken leg, he told Human Rights Watch.

Two of the protesters Human Rights Watch interviewed said they saw some fellow protesters throw stones at the remaining vehicles on the side street, including one that hit and injured a female YPG member in the head.

At this point, some YPG fighters opened fire in the air with their automatic weapons while the remaining vehicles advanced onto the main road heading towards the square, the witnesses said. By now the crowd had dwindled to about 100 people.

The subsequent sequence of events is disputed. The Asayish and YPG claim that YPG forces came under fire from people in the crowd, killing a YPG soldier named Sabri Gulo, which provoked the YPG to respond with live fire from their positions on the main road. Participants in the protest interviewed by Human Rights Watch say that none of the protesters had weapons and the YPG shot without reason at the crowd. YPG fighter Sabri Gulo might have been killed during the fighting at Hasakah dam, they said. Both the protestors and the Asayish confirmed that in shooting at the crowd, the YPG killed a child, an elderly man, and a third man, and wounded about a dozen others.

One of the protesters explained what he saw:

The PYD forces were there and men threw rocks. The PYD opened fire around 8pm. They were very close to us. I called on the protesters to retreat. I ran and hid between a shop and a column. Bullets were hitting the column and the shop. They had mounted machine guns, automatic weapons, but they only fired Kalashnikovs at the protesters… When it stopped, I saw people on the ground.[117]

Another protester gave a similar account, though he said he did not see any protesters throwing rocks:

At first they [YPG] shot in the air, but this didn’t scare us. After a while they shot at the ground. Then people started to move away. When that began a few people fell down…People were running. There was heavy shooting…. When I ran away I looked back and saw lots of people falling down. [118]

Those killed at the protest were:

- Nadir Khalo, about 15 years old;

- Sa`id Sayda, about 18 years old;

- Shaykhmus `Ali, about 65 years old (did not participate in the protest).

Human Rights Watch also reviewed six videos that captured parts of the protest. Five of the videos were provided by sympathizers of or participants in the protest. The file properties indicate that they were all filmed on June 27, 2013. Two of these videos were also posted on YouTube. The sixth video was recorded by unknown people and provided to Human Rights Watch by the YPG.

One of the videos posted on YouTube shows four people throwing unidentified objects at the convoy after shooting had already started.[119] The other posted video shows a chanting crowd gathered around the convoy and then a YPG fighter shooting in the air, followed by more shooting, apparently from the convoy.[120] One of the videos not posted shows a convoy of at least five vehicles, including three pick-up trucks with mounted automatic weapons, turning onto the main street amidst heavy shooting from unknown sources. In none of the five videos are any of the protesters seen with a weapon.